Introduction: conversion, multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism

The investigation of early Christian sites in border regions, remote from centres of power, provides the opportunity to frame the archaeological record in the context of wider historical themes, such as conversion, multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism. This article focuses on the excavation of two of the three known early Christian churches in the Aksumite city of Adulis, located in present-day Eritrea. The long stratigraphic sequences documented since 2017 by the Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana allow assessment of not only these two buildings but also of wider developments across the region, in terms of what might be called an ‘archaeology of conversion’. The concept of conversion may appear restrictive, reducing religious change to the passage from bad to good, or from disorder to civilisation. Conversion, however, relates to not only cultural and spiritual change, but also to many other spheres of human life; indeed, “religious change is actually change in worldview” (Shaw Reference Shaw2013: 1). This broad context could be framed as ‘multicultural’, an approach that “extends equitable status or treatment to different cultural or religious groups within the bounds of a unified society” (Meskell Reference Meskell2009: 4); yet this risks a ‘Western-centric’ perspective that neglects the “indigenous perceptions of history” (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal and Meskell2009: 115). Instead, Timothy Insoll (Reference Insoll2021: 452) has recently characterised the early historic Horn of Africa as the cradle of a “cosmopolitan milieu”. This approach values cultural differences, seeking to balance local and non-local elements in the shaping of new cultural and religious realities (Meskell Reference Meskell2009: 4–5).

The present article therefore aims to examine new archaeological data from Adulis in light of this theoretical context and to consider the following questions: can we speak of conversion—that is, the process of immediate and complete change of religious creed—or should we instead view religious change as a process of adhesion, whereby new social and religious models are progressively adapted to (Papaconstantinou Reference Papaconstantinou2015)? How did internal and external factors shape the complex transition from paganism to Christianity and then to Islam? And can we move beyond conversion to develop an archaeology of cosmopolitanism?

Historical and archaeological background

Between the first and eighth centuries AD, the Kingdom of Aksum extended across much of what is today northern Ethiopia and Eritrea (key studies include Munro-Hay Reference Munro-Hay1990, Reference Munro-Hay1991; Phillipson Reference Phillipson1998, Reference Phillipson2012; Fattovich Reference Fattovich2018). Via the Red Sea, the kingdom maintained maritime trade routes with the southern Arabian Peninsula (Tomber Reference Tomber2008; De Romanis & Maiuro Reference De Romanis and Maiuro2015), as well as India, Taprobane (Sri Lanka) and Tzinista (China). Following the canonical chronology, affirmed by excavations at Bieta Giyorgis hill near the capital city of Aksum (Bard et al. Reference Bard, Fattovich, Manzo and Perlingieri2014), the kingdom's floruit was during the Middle Aksumite Period (AD 380–580). This was marked by a distinctive monumental architectural tradition (Eigner Reference Eigner and Uhlig2003; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009; Breton Reference Breton2015; Gaudiello & Yule Reference Gaudiello and Yule2017: 236–44), the scale of economic activity, and an early sixth-century expansion into the Himyarite Kingdom of southern Arabia (Gajda Reference Gajda2009; Robin Reference Robin and Fisher2015).

During the fourth century AD, under King Ezana, the royal court converted to Christianity. At the same time, Fumentius, the first bishop of Aksum, was appointed by Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria, establishing an enduring link between the Ethiopian and Egyptian churches (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1982; Fedalto Reference Fedalto1988: 670; Munro-Hay Reference Munro-Hay1988, Reference Munro-Hay1997; Amidon Reference Amidon2016 [1997]: 394–96). Some scholars argue that this conversion was a top-down process, with the court initially adopting Christianity, and the wider population only following sometime later (e.g. Hable Selassie Reference Hable Selassie1972: 104; Kaplan Reference Kaplan1982; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 30; contra Seland Reference Seland2014). The recent discovery of a fourth-century church at Beta Samati (Ethiopia) (Harrower et al. Reference Harrower2019; Bausi et al. Reference Bausi, Harrower and Dumitru2020), as well as the work reported here from Adulis, however, provide an enlarged dataset with which to revisit interpretations of the adoption of Christianity in the Kingdom of Aksum.

The site of Adulis

Adulis stands on the Gulf of Zula, 50km south of Massaua, in a flat desert area. Although originally a port city, today it lies 6km inland (for a history of research, see Paribeni Reference Paribeni1907; Sundström Reference Sundström1907; Anfray Reference Anfray1974; Munro-Hay Reference Munro-Hay1989; Peacock & Blue Reference Peacock and Blue2007; Zazzaro Reference Zazzaro2013; Anfray & Zazzaro Reference Anfray and Zazzaro2016) (Figure 1). One of the most important centres of the Aksumite Kingdom, the port-city of Adulis is noted in first-century AD sources, such as Pliny the Elder and the Periplus Maris Erythraei, as an important trade centre (Casson Reference Casson1989: IV-5). The site also played an important role in the Christianisation of the Horn of Africa, with its first known bishop, Moses, appointed in the fifth century (Palladius. De Gentibus Indiae et Bragmanibus I-4; Berghoff Reference Berghoff1967; Fedalto Reference Fedalto1988: 683). In the early sixth century, the Egyptian merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes travelled to Adulis, recording the visit in his Topographia Christiana (Kominko Reference Kominko2013) and included a description of the ‘Throne of Adulis’, which was inscribed with a bilingual inscription known as the Monumentum Adulitanum (Cosmas Indicopleustes Topographie chrétienne: II-52/64; Wolska-Conus Reference Wolska-Conus1968–1973; Bowersock Reference Bowersock2013).

Figure 1. The main sites mentioned in the text (figure by G. Castiglia).

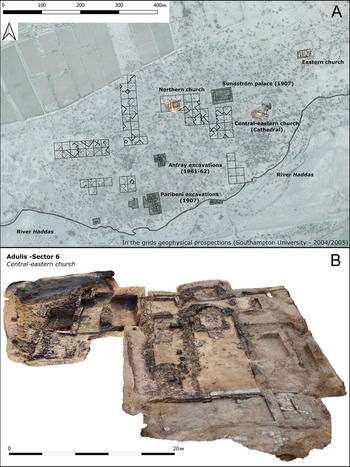

The site of Adulis covers approximately 40ha. Only a small percentage of this area has been excavated, however, and most of the site is poorly known (the Throne, for example, has not yet been located) (Figure 2A). The river Haddas forms the southern boundary of the city, but no defensive walls—as are known from other Aksumite towns—have yet been identified (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2012: 119). The best-documented phases of activity are those dating to the Middle Aksumite Period, and a recent study suggests that the city's decline and abandonment should be dated to the late sixth to early seventh century (Zazzaro et al. Reference Zazzaro, Cocca and Manzo2014), although the results of the latest excavations, presented below, appear to delay this final phase by a few decades.

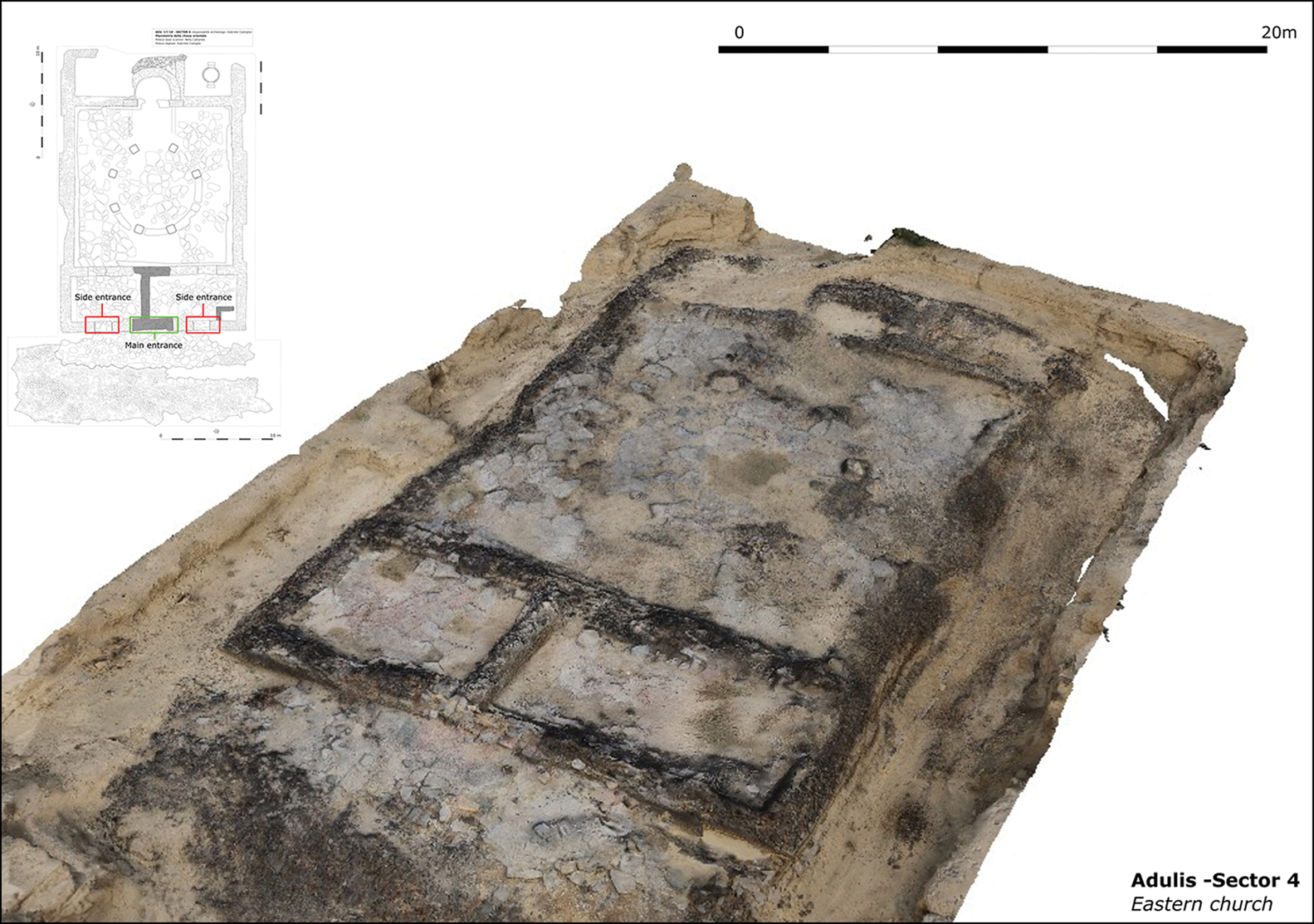

Figure 2. A) The site of Adulis; B) photogrammetry of the central-eastern church (images by S. Bertoldi and G. Castiglia).

The central-eastern church

The recent excavations by the Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana have focused on two early Christian buildings: the central-eastern church and the eastern church. Here, I document the evolving structural forms of these buildings and their associated material culture, before assessing the significance of these results for changes in liturgy and perceptions of space and, in the case of the conversion of one of the churches into a small Islamic cemetery, the transition to a new religious identity and function.

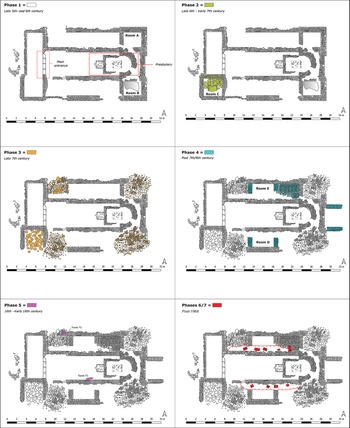

The central-eastern church was located close to the centre of the city. It was first investigated in 1868 by a British expedition (Munro-Hay Reference Munro-Hay1989), which compromised elements of the archaeological deposits. The most recent excavations, however, have been able to identify and fully investigate well-preserved contexts, which form the basis of a five-phase construction sequence (Figures 2B & 3).

Figure 3. Phases of the central-eastern church (figure by G. Castiglia).

Phase I

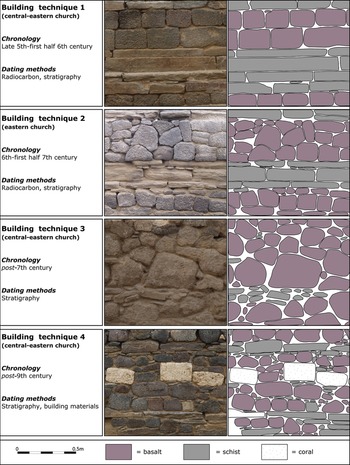

The first phase of the church is a structure, built on a massive platform (typical in the Aksumite tradition; Di Salvo Reference Di Salvo2017), and measuring approximately 30 × 20m. The building fabric comprises regular courses of basalt blocks and schist slabs. In contrast to the unshaped basalt blocks used in the other Adulis churches, in the south-eastern church the basalt blocks are rectangular and all of similar size (150mm high and 250/300mm wide) (Figure 4). The entrance, to the west, is marked by a massive granite threshold. Inside, in the southern part of the narthex, a wall added in Phase II to create a new room (Room C; see below) has erased the earlier stratigraphy; we hypothesise, however, that this later intervention was intended to restore a small chapel of Phase I.

Figure 4. Building techniques in the churches of Adulis (figure by G. Castiglia).

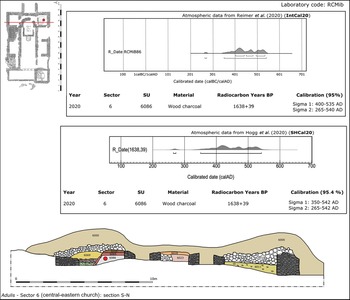

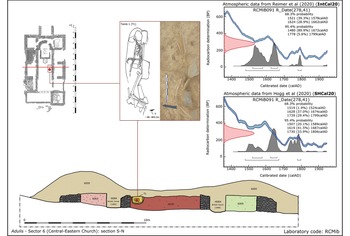

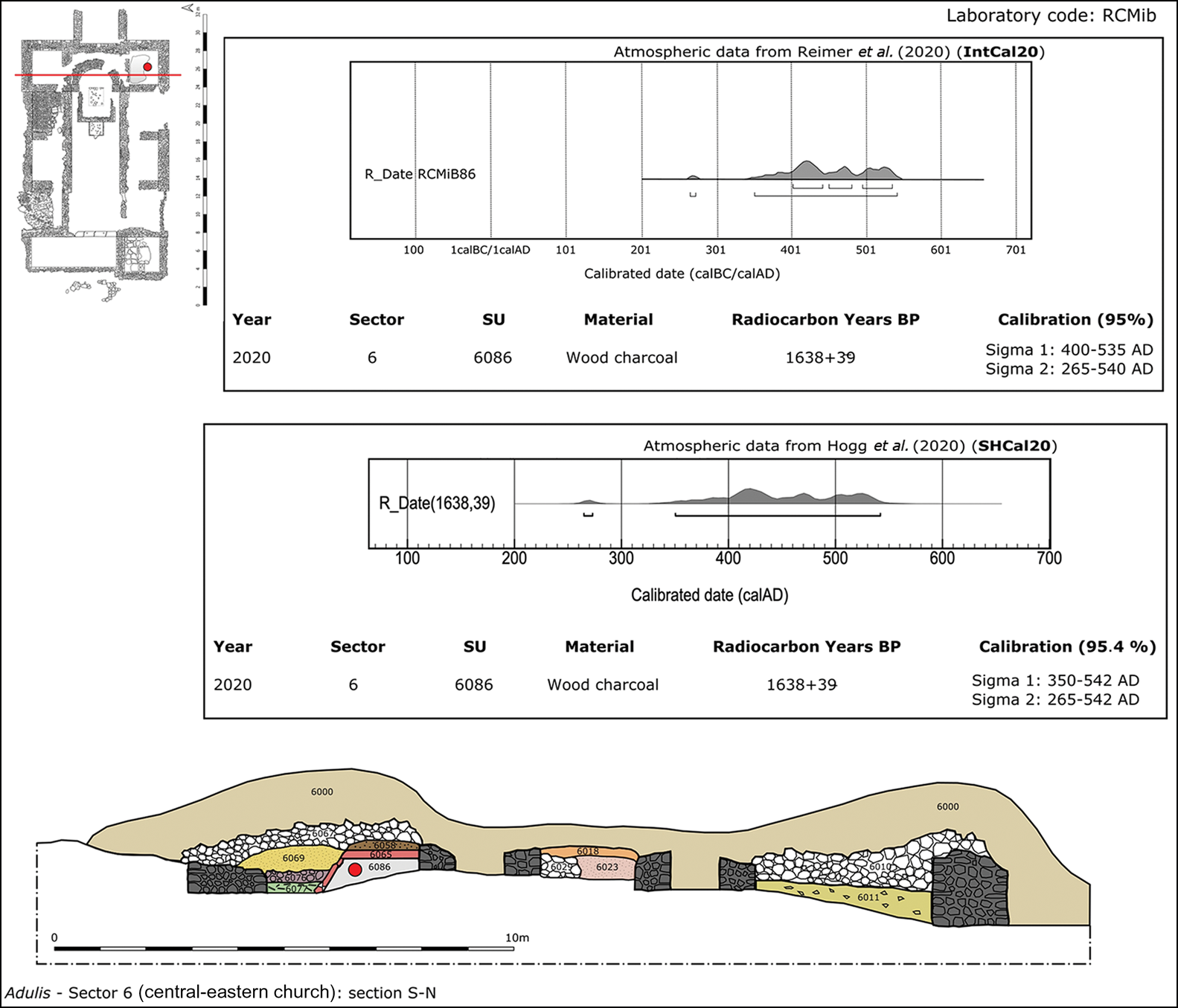

The main hall is divided into three naves, separated by two rows of pillars. At the eastern end of the building is a semi-circular apse, which frames a rectangular structure that formed a base for the main altar. The apse is flanked by two square rooms, of which the southern bears traces of hydraulic mortar (SU 6065), probably indicating the presence of a baptistery. The pavement, although only preserved across approximately half of one of the square rooms, bears traces of a curving edge, which possibly relates to a decentralised fons (baptismal font) that was positioned off-centre within the room and was lost when the floor collapsed. Radiocarbon analyses on wood charcoal from the preparation layer (SU 6086) beneath the baptistery floor give a date for the first phase of construction of cal AD 400–535 (Figure 5; note that calibration with both IntCal20 and SHCal20 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020) is provided, though there is no significant difference; the same is true for the other radiocarbon dates discussed below).

Figure 5. Radiocarbon data from the central-eastern church. The red dot indicates the sampling area. Chronology provided using both IntCal and SHCal (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020) (figure by G. Castiglia).

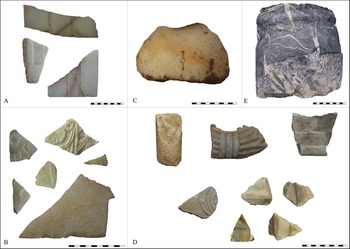

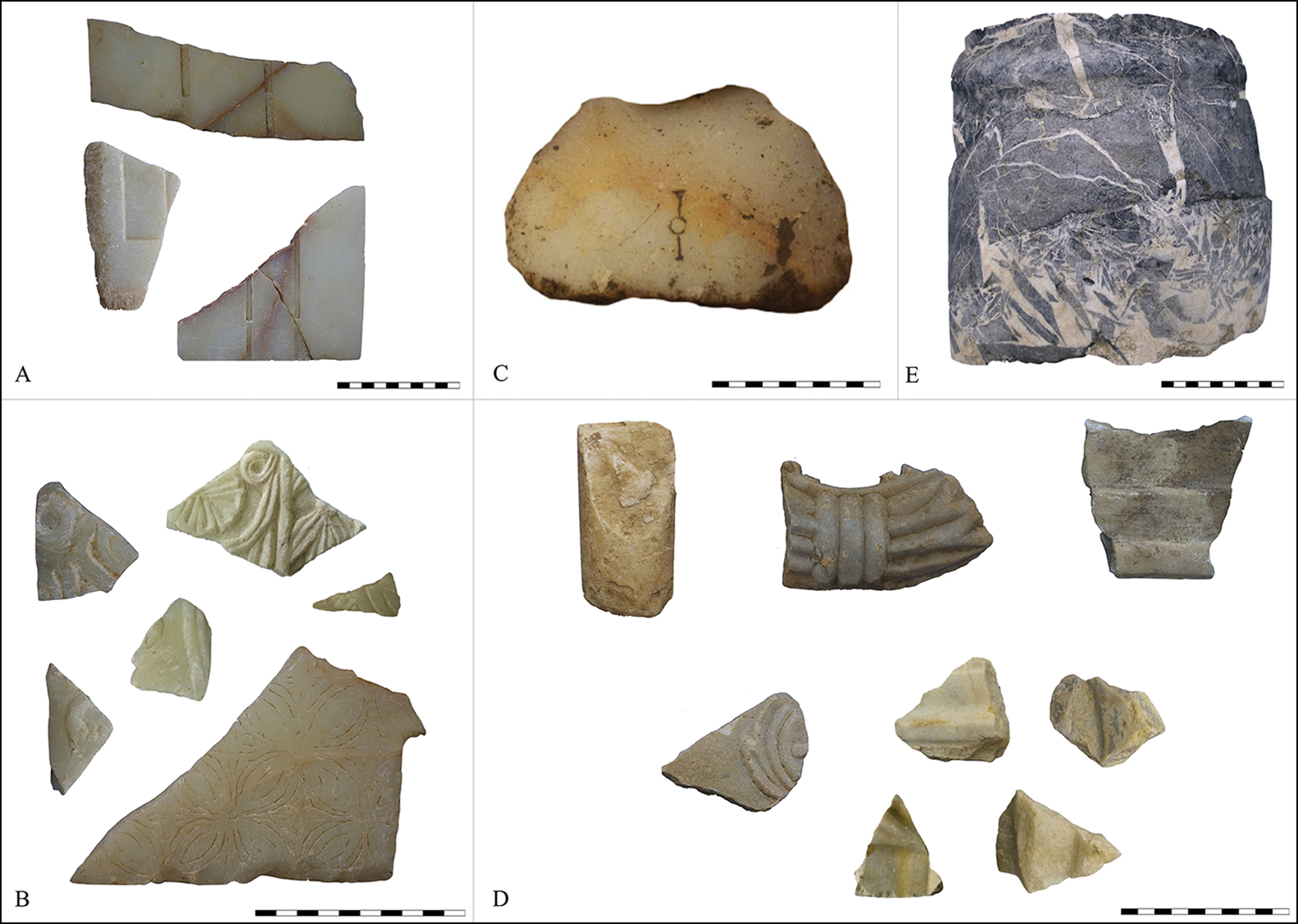

Finds from Phase I include a number of marble and alabaster fragments associated with the liturgical functions and decoration of the church. The style of the decorative stonework is typical of the Syro-Palestinian tradition of the sixth century AD, recalling Byzantine styles characteristic of the Justinianic period, suggesting close contact with nearby Himyar (Pola in Castiglia et al. Reference Castiglia2020, Reference Castiglia2021; see also Yule Reference Yule2013) (Figure 6), while also corroborating the radiocarbon chronology. In this phase, a Y-shaped chancel divided the presbytery from the main hall, and we assume that some of the decorated marble fragments formed part of this chancel, which was also used in later phases. Based on the building's size, the quality of construction, the presence of a baptistery, and its location within the city, it is reasonable to hypothesise that this church fulfilled the role of a cathedral.

Figure 6. Specimens of marble and alabaster from the central-eastern church: A) alabaster slabs with linear line decoration; B) alabaster slabs with phytomorphic decorations; C) fragments of alabaster slab bearing a Q in Late Sabiac, used as a production mark in Himyar; D) fragments of liturgical specimens in Proconnesian marble; and E) fragment of column in Bianco e nero antico marble (scales in cm) (photographs by M. Pola).

Phase II

In Phase II, a significant change was made to the south-western part of the church, with the addition of a square room (Room C). The installation of a central square platform suggests the presence of an altar; if so, this room may have been a chapel where the Christian community left offerings before entering the church, as was common in Byzantine liturgy (Taft Reference Taft and Akentiev1995; Mulholland Reference Mulholland2014). Alternatively, the central platform might have formed the foundation for a stairway leading to a tower in the façade (common in Syriac churches; Tchalenko Reference Tchalenko1990) or to an upper floor (similar to sixth-century Nubian churches, such as Faras; Obłuski Reference Obłuski, Łajtar, Obłuski and Zych2016).

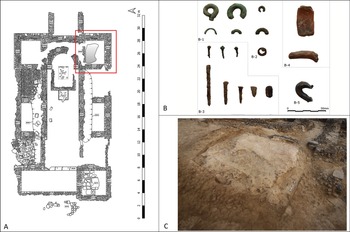

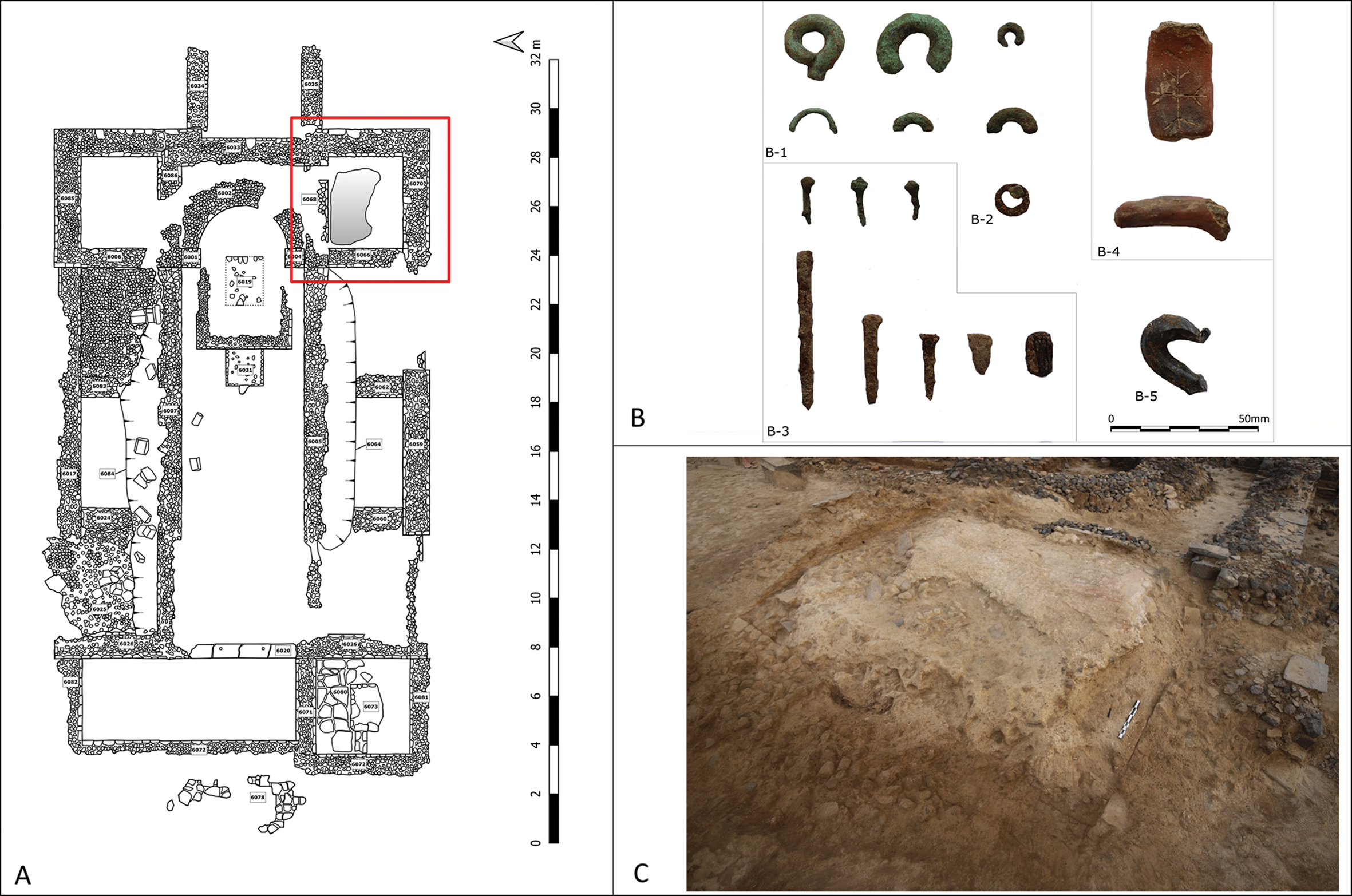

Important Phase II chronological markers from directly above the baptistery floor (in SU 6058) include Late Aksumite pottery (some marked with crosses), sherds of Ayla-Aksum amphorae and various bronze elements (mostly rings of different sizes relating to at least one polychandelon, or lamp with multiple candles); all date to the late sixth and early seventh centuries (Figure 7). The church arguably continued to serve as a cathedral at this time, with only a minor architectural change (Room C), which suggests a possible evolution in liturgy towards the Byzantine tradition (Taft Reference Taft and Akentiev1995).

Figure 7. Central-eastern church: A) overall plan, showing baptistry (red square); B) finds from the layer above the baptistry (SU 6058); and C) the baptistry during excavation (images by G. Castiglia).

Phase III

Phase III presents the first signs of abandonment, such as the massive structural collapses, especially in the northern nave. This may date to the second half of the seventh or early eighth centuries, although most of the collapse deposits and other traces of abandonment were erased by the British expedition of 1868.

Phase IV

In Phase IV, the building likely ceased to function as a church, although the nature of activity remains unclear. Partial repair and reconstruction of the building include significant interventions in the northern and central naves, where some of the earlier collapse is cut through and retaining walls inserted to create two new rooms (Rooms D and E; Figure 3). Two massive trenches from the 1868 expedition, however, severely damaged the stratigraphy within these rooms. In the northern nave, a floor of rough stones was laid at the same time as the construction of Room E. Even though the reconfiguration of the church in this phase remains unclear, it appears that the building was shortened, with the western part almost entirely abandoned. Moreover, two parallel walls were added against the eastern external wall of the church. These walls are mostly composed of spolia, alongside blocks of white coral laid in irregular courses. The adoption of coral as a building material in the Horn of Africa coincides with the arrival of Islam, with the ninth century providing a terminus post quem; it remained a popular building material until the thirteenth century (Horton Reference Horton1991: 114–15; Insoll Reference Insoll2003: 172–73).

Phase V

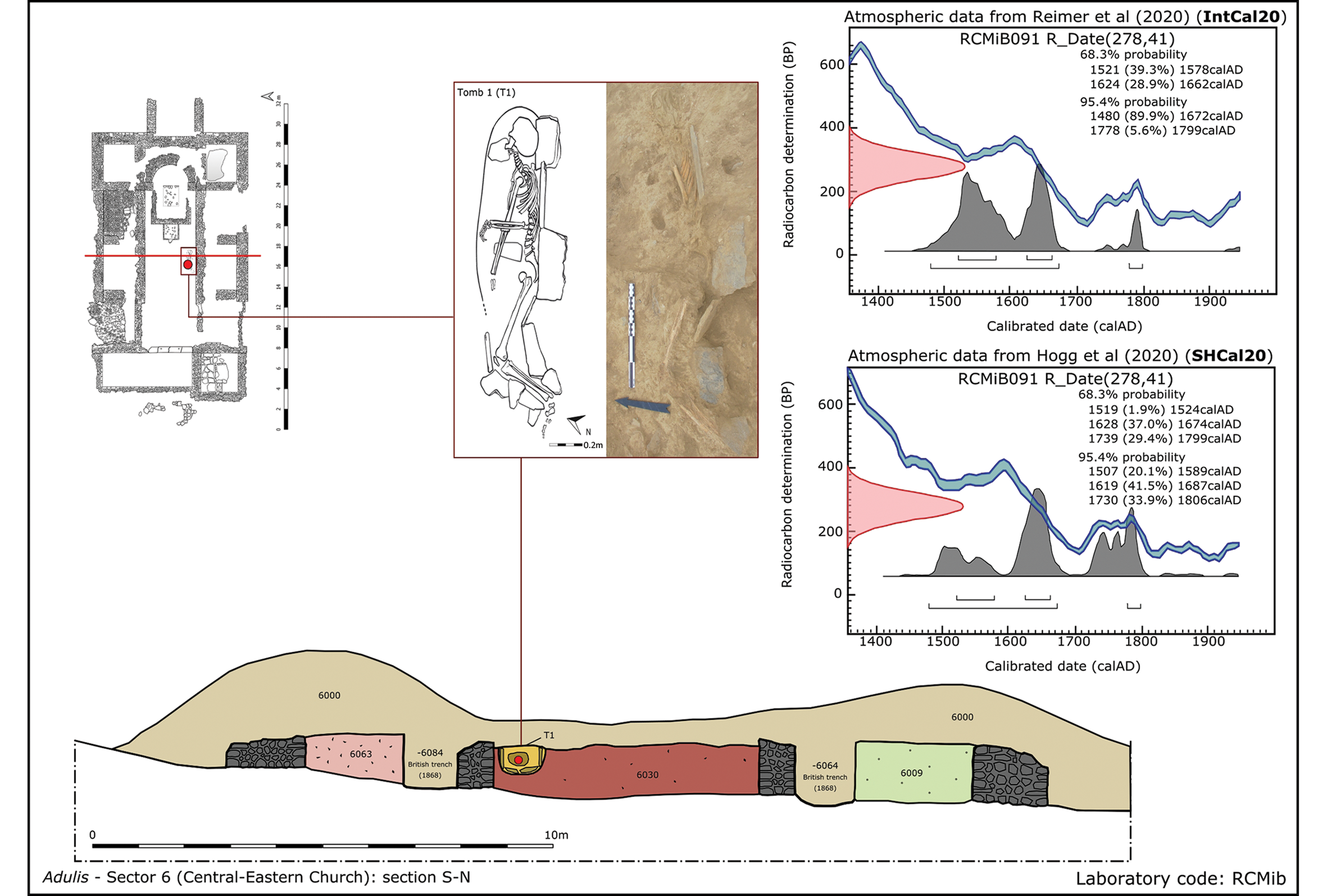

In Phase V, the function of the building continued to change, as exemplified by the insertion of a small funerary area in the central nave, with evidence of two burials. There are strong indications that both individuals were buried in accordance with Islamic tradition, including the positioning of the bodies to face Mecca, the presence of stone pillows to prevent the head from touching the earth and the absence of grave goods (see Insoll Reference Insoll2003: 196; for an anthropological study of the burials and a wider discussion on their interpretation, see Larentis in Castiglia et al. Reference Castiglia2020). Radiocarbon analysis of bone from one of these burials (T1) provides a wide chronology, but the most reliable calibration for the geographic area under study (IntCal20) suggests an early sixteenth century date (Figure 8)—a time when the area would imminently fall under Ottoman rule (Chekroun & Hirsch Reference Chekroun, Hirsch and Kelly2020).

Figure 8. Radiocarbon data from the burial in the main nave of the central-eastern church. The red dot indicates the sampling area. Chronologies provided using both IntCal20 and SHCal20 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020) (figure by G. Castiglia).

Phases VI–VII

Phases VI–VII record the definitive abandonment of the church, followed by the excavations of the British expedition of 1868.

The eastern church

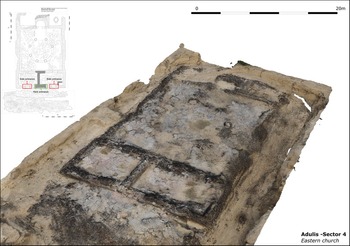

The recent excavations of the eastern church have proven problematic due to the damage caused by a dig in 1907, led by Roberto Paribeni, which completely erased the stratigraphy of the building except for a small but important portion around the western entrance. Nevertheless, architectural analysis and radiocarbon dating allow us to establish an absolute chronology for the construction of this building and to identify two main phases (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Overall plan and photogrammetry of the eastern church (figure by G. Castiglia and S. Bertoldi).

Phase I

The building typifies the Christian and secular architecture of the Aksumite Kingdom, characterised by construction on a massive platform of basalt blocks and schist slabs (Giostra Reference Giostra2017; Castiglia Reference Castiglia2019). The church measures approximately 26 × 18m and has a semi-circular apse, with two external rooms, one either side of the apse. A circular fons, decorated with red plaster, in the room immediately south of the apse indicates the presence of a baptismal font. The western entrance passage into the internal hall of the basilica is bordered by a small presbytery enclosure that leads into the main nave of the basilica, where eight central pillars would have provided support for a dome. To the immediate west of the building, excavation has revealed a large quantity of schist slabs and collapse deposits from a structure—perhaps a staircase that connected the raised church to the level of the surrounding city.

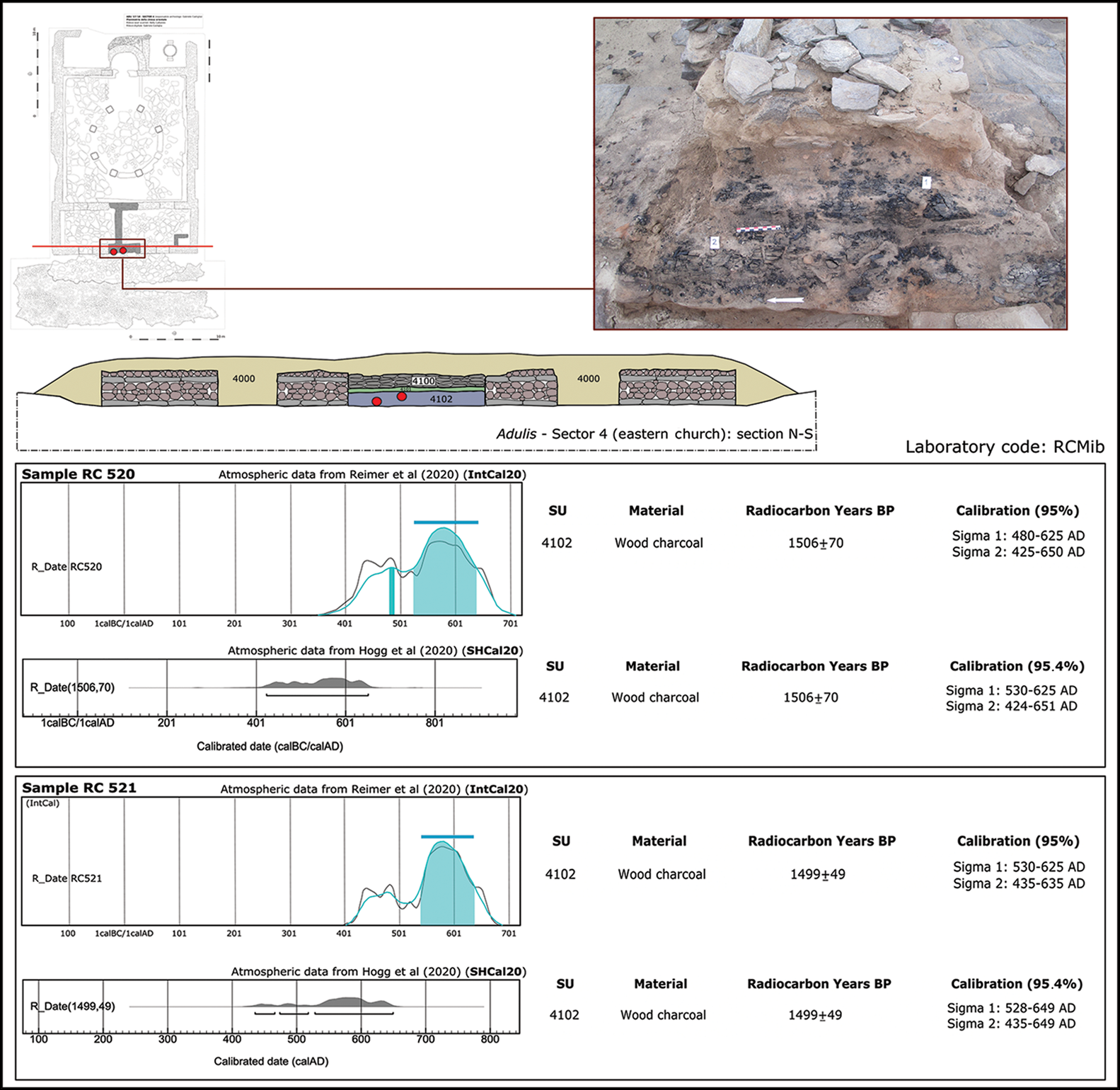

Excavation of the western entrance identified an element crucial for dating the church: a large, carbonised wooden beam, probably carved to define a step or threshold, and which clearly formed part of the primary construction phase (SU 4102). Radiocarbon analysis of two samples from this beam gives a date between the late fifth and the first half of the seventh century, providing an indication of the date of Phase I (Figure 10). Considering its location, it is possible that the eastern church served as a suburban sanctuary, perhaps providing baptismal rites to the Christian community of Adulis, or else part of a wider strategy of stational liturgy, in which bishop and clergy processed through all of the churches within a city to provide liturgical rites.

Figure 10. Radiocarbon data from the eastern church. The red dot indicates the sampling area. Chronologies provided using both IntCal and SHCal (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020) (figure by G. Castiglia).

Phase II

In Phase II, the most important alteration observed concerns the main entrance, where a massive, T-shaped wall split the narthex into two separate rooms, each equipped with two small side entrances. In contrast to the Phase I building technique, the Phase II wall mostly comprises roughly organised spolia. As in the central-eastern church, a small room was added in the south-western corner of the narthex, but its function is difficult to interpret. Based on the radiocarbon analyses of the beam, which was directly beneath the new wall, Phase II dates to the second half of the seventh century or later.

Discussion

The central-eastern church is the largest and most elaborate Christian building currently known at Adulis (Figure 3). The dimensions of the building and the evidence for a baptismal font suggest that it fulfilled the role of the ecclesia episcopalis (cathedral) of Adulis. The eastern church, on the other hand, is currently unique within the Askumite architectural tradition as the only known Christian building with a circular arrangement of pillars—most probably to support a dome. This feature may reflect direct influence of the Byzantine world of the Justinianic period, when central domes became popular for churches throughout the empire. This influence may be linked to contacts between Constantinople and Aksum in the first half of the sixth century in the context of the Persian Wars, when Byzantium sought an alliance with the Kingdoms of Aksum and Himyar to counter the Persian monopoly of the silk trade (Greatrex Reference Greatrex1998; Beaucamp Reference Beaucamp, Beaucamp, Briquel-Chatonnet and Robin2010).

Comparison of the new dates for the south-eastern and, especially, eastern churches with radiocarbon dates from excavations elsewhere around Adulis (e.g. Zazzaro et al. Reference Zazzaro, Cocca and Manzo2014) suggests that the decline of the city occurred a few decades later than previously thought. Variation in the dates of the latest activity at different locations across the city, however, may indicate that, rather than a sudden and unexpected abandonment, Adulis experienced a process of gradual decline, with some areas remaining in use longer than others.

In light of these findings at Adulis and those from the recent excavations at Beta Samati, including the fourth-century church (Harrower et al. Reference Harrower2019; Bausi et al. Reference Bausi, Harrower and Dumitru2020), we now have evidence of multiple chronologies for early Christianity within the Aksumite Kingdom. It is plausible that Beta Samati, located near Aksum, may have been directly influenced by the capital, and that the royal court's conversion to Christianity may have had an immediate effect on such surrounding settlements. On the other hand, Adulis, located further away, may have undergone a later transition, probably under the influence of the Byzantine Empire via the Red Sea. The church at Beta Samati does, however, testify to prolonged use over an extended period, with close parallels to the later chronologies of the churches at Adulis. The discovery of evidence for post-Aksumite activity at Adulis—namely the two Islamic burials—points towards a wider phenomenon. We cannot exclude the possibility that there might be traces of a later and partial re-occupation in other (unexcavated) areas of the city.

Returning to the issues raised in the introduction, we can now address the themes of conversion, multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism. Does the materiality of early Christianity (and, later, of Islam) at Adulis suggest a process of definitive and straightforward conversion? There is no doubt that the material impact of Christianity was an imposing phenomenon, with the churches representing monumental interventions in the urban topography. At the same time, the church chronologies reveal a process of Christianisation that was gradual and evolving. Written sources and epigraphy indicate that this ‘new’ religion took root in the early fourth century (at least among the royal court), but its adoption by the wider population only reached its full extent by the late fifth or early sixth centuries. It is reasonable, however, to hypothesise that these processes were heterogeneous, varying across the kingdom, with forms and chronologies depending on many internal and external factors (including trade, cultural influences, politics and war). In this regard, Aaron Butts has suggested that the conversion of Ezana as the first Christian king of Aksum may not have followed the ‘classic’ linear model—that is, a transition from pagan to monotheist to Christian. Butts (Reference Butts and Walters2021: 380–81) points out that:

this linear narrative of Ezana's conversion is not, however, without problems, and other interpretations of the data are possible and perhaps even preferable: the distinct self-presentations of Ezana may, for instance, have been motivated by different aims and intended audiences.

Can we encompass all this evidence within an interpretation of a singular and definitive conversion? It is improbable. Instead, the evidence points to a gradual and ongoing process of change among different peoples and cultures without leading to either a violent or complete process of conversion. If we look, for example, at the coexistence of “pagan and Christian ritual paraphernalia” in the fourth-century phase at Beta Samati (Harrower et al. Reference Harrower2019: 1550), we see a mix of local and non-local elements, which encapsulate the definition of ‘vernacular cosmopolitanism’ recently applied to the western Ethiopian borderlands (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2021: 530). In such contexts, the transition from pagan to Christian was the result of various influences that never aimed to erase definitively the vernacular peculiarities of an area.

Can we say the same for the transition to Islam? In this case, the evidence from Adulis remains unclear. Nonetheless, the insertion of a small Islamic cemetery within a ruined church during the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century may well represent the appropriation of a sacred place by generating a multi-layered context of religious expression, “overlaying rather than erasing pre-existing cultural strata” (Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau2021: 509). On the other hand, this material process may introduce the concept of hybridisation through a symbolic strategy of memory, where the early Christian past became the vernacular, and Islam the new cosmopolitan element.

All of these issues lead us to the final question: can we go beyond an archaeology of conversion? Across the Horn of Africa, religious change was never a top-down process, nor did it result in a clear-cut break with the past and loss of the vernacular. Instead, different religions acted as both innovative and conservative factors. Churches monumentalised a new religion but, at the same time, perpetuated the architecture and building techniques of the pre-Christian Askumite tradition. Mario Di Salvo has emphasised how the craftsmen who built the churches of the Aksumite Kingdom “became ‘Ethiopian’ through conscious choice and adopted features which articulated the structural elements and decorative motifs closely based on what had been inherited from the past” (Di Salvo Reference Di Salvo2017: 5). Similarly, the use of carved marble and alabaster communicated the Christian message, but also preserved existing artistic expressions, such as the use of incense burners for early Aksumite, Christian and Islamic rituals (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2012: 91–106). Islamic burial practices, meanwhile, transformed Christian rites while simultaneously perpetuating the existence of former sacred buildings as lieux de mémoire.

Conclusions

The new data from Adulis attest to the value of an archaeological approach to the materiality of religious change, and the successive phases of church construction and modification reflect evolving practices and connections. Moreover, our findings reflect how an archaeology of cosmopolitanism, as framed above, allows for a wider perspective on religious transition and heterogeneous inputs that contributed to the framing of new and particular cosmopolitan identities.

Consequently, an archaeology of conversion is too simplistic: as François-Xavier Fauvelle (Reference Fauvelle and Kelly2020: 113) has recently stated, “the history of Christianity and Islam in medieval Ethiopia cannot be narrated as that of Christian and Muslim immigrants arriving en masse in an empty land”. This cuts to the core of the issue: the need to leave aside our Western- and Mediterranean-centred approaches in order to view these pivotal transitions as milieux of local and external elements that frame cosmopolitanism as the force that shapes past—and indeed present—societies. In this way, the ‘archaeology of conversion’ can move forward as an archaeology of cosmopolitanism and complexity (Insoll Reference Insoll2021).

Acknowledgements

I thank my friends and colleagues at the Eritrean-Italian mission in Adulis: Serena Massa and the late Angelo Castiglioni (mission coordinators), Stefano Bertoldi, Marco Ciliberti, Božana Maletić, Matteo Pola, Susanna Bortolotto, Nelly Cattaneo, Matteo Delle Donne, Paolo Fusetti, Gabriella Giovannone, Paolo Lampugnani, Omar Larentis, Chiara Mandelli, Laura Masina, Paolo Visca and Gabriele Zanazzo. I also give special thanks to the Commission for Culture and Sports of the Eritrean Government (in particular, Tsegai Medin) and the Northern Red Sea Regional Museum of Massaua (especially Yohannes Gebreyesus), and their respective teams. A great debt of gratitude is also due to the Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, in particular to Philippe Pergola and Mons. Carlo Dell'Osso. This article is dedicated to the Eritrean people of the villages of Afta, Foro and Zula, in the area surrounding Adulis.

Funding statement

This research was funded by L’Œuvre d'Orient, the ALIPH Foundation and the Congregazione per le Chiese Orientali.