“The Republican Party has become … ideologically extreme; contemptuous of the inherited social and economic policy regime; scornful of compromise; unpersuaded by conventional understanding of facts, evidence, and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition.”Footnote 1 This startling description appeared not in a broadside issued by the Democratic National Committee but in a wonkish 2012 book, It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided with the New Politics of Extremism, co-authored by two sober-minded analysts of different personal political persuasions, Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein. Breaking from the pundit consensus that polarization in contemporary U.S. politics must always be even-handedly blamed on “extremists” in both political parties, Mann and Ornstein pointed out that even though the two parties did move symmetrically apart from the 1960s to the 1980s, since then continuing U.S. partisan polarization has mainly been driven by the unremitting rightward movement of the GOP. Tellingly, this far-right lunge has not slowed in the 2000s, not even during the presidency of self-declared “compassionate conservative” George W. Bush nor after Democrats won major electoral victories in 2006, 2008, and 2012. Traditional political science models predict that losing parties will move toward the middle to attract “median voters,” but that has not happened for the present-day Republican Party, whose politicians increasingly embrace unpopular stands and obstruct routine governing functions.Footnote 2

Why has this happened? Standard wisdom blames current GOP extremism on unruly party base voters—on Tea Partiers, or Christian conservatives, or working-class nativists. In safely-conservative legislative districts and presidential primaries dominated by base voters, GOP stances on social issues like abortion or immigration can be attributed to such pressures from below. But this explanation sheds little light on accelerating GOP economic extremism. On one economic issue after another, virtually all Republican politicians—including contenders for the presidency and candidates for the Senate in large, diverse states—have moved toward unpopular far-right positions. Not even conservative populist voters are demanding cutbacks or privatization of Social Security or Medicare, yet virtually all nationally prominent Republicans now push these overwhelmingly unpopular ideas.Footnote 3 Americans in general increasingly favor higher taxes on the rich, but Republican politicians universally call for massive, upward-tilted tax cuts—and such proposals have become more sweeping in each successive presidential contest from 2008 through 2012 to 2016.Footnote 4 Large majorities of Americans, including many Republicans, favor modest increases in the minimum wage and new social supports such as mandated paid family and sick leave, but GOPers in office have become increasingly dug in against all such steps.Footnote 5

The rightward lunge of the GOP is undoing longstanding compromises. For decades, many Republican governors and legislators coexisted with public-sector unions; but recently, in state after state, GOP governments have abruptly taken unpopular steps to destroy unions and eliminate established collective-bargaining rights.Footnote 6 Most voters, along with many prominent business organizations, favor increased government investments in infrastructure, but more and more Republicans seek to unravel longstanding federal or state highway and construction programs.Footnote 7 Finally, most Americans, including majorities of Republicans and GOP-leaning Independents, endorse many environmental protections and want carbon dioxide to be regulated as a dangerous pollutant.Footnote 8 But with increasing unanimity, Republican politicians rail against climate-change reforms and seek to undercut environmental regulations of all kinds. As Vox reporter David Roberts has detailed, popular views are not sufficient to explain why the U.S. Republican Party has become “the world’s only major climate-denialist party,” an outlier even compared to other conservative political parties worldwide.Footnote 9

Clearly, many Republican candidates and officeholders are responding to elite-driven forces, not just to voters. But in the elite realm, too, we must look beyond the usual suspects—lobbying groups and individual big-money political donors. After all, politicians from both parties court big-money contributors. And business associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that have long set GOP economic agendas nowadays find themselves fighting far-right groups over the renewal of longstanding business subsidy programs like the U.S. Export-Import Bank or the farm bill.Footnote 10 Something more must be at work in the recent lunge of the GOP toward the ultra-free-market right. We highlight a heavyweight new player in conservative politics—the recently expanded “Koch network”—that coordinates big-money funders and an integrated set of political organizations operating to the right of the Republican Party. As we will show, the rise of the Koch network may help to explain the increasingly-extreme economic positions espoused by most GOP candidates and officeholders.

An Organizational Approach

For this analysis, we draw data and findings from a new research project on “The Shifting U.S. Political Terrain.”Footnote 11 Focusing on organizations rather than simply on mass publics or aggregates of wealthy donors, this project uses data on the founding dates, goals, budgets, personnel, and inter-group ties of key organizations active on the right and left in U.S. national and cross-state politics. The project examines both party committees and extra-party organizations, ranging from think tanks and donor organizations to advocacy and constituency groups. Where wealthy funders are concerned, we pay especially close attention to “donor consortia”—that is, organizations such as the twice-yearly Koch seminars convened by Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce on the right and the meetings held by the Democracy Alliance on the left. A focus on such coordinated funding groups, rather than just on individual donors or particular PACs, makes sense because concerted and sustained funding efforts are much more likely to have an impact on political parties and governing agendas than one-shot donations to single-issue campaigns or to candidates running in particular elections.

Information about organizational budgets and, in some cases, on leadership and staffing allow us to ask and answer fresh questions: How have balances and relationships shifted between party committees and extra-party groups; between old-line organized players and newly-formed efforts; and between consortia of wealthy political donors and broad-based associations? Can we identify genuinely new kinds of formations that might help to explain extreme GOP stances on economic issues?

Drawing from our larger project, the following sections provide an overview of recent sharp shifts in the universe of GOP and conservative political organizations and then explore the structure and goals of the Koch political network that has recently amassed extraordinary capacities to wage policy and electoral battles in dozens of U.S. states as well as in Washington, DC. As we will show, because of its massive scale, tight integration, ramified organizational reach, and close intertwining with the GOP at all levels, the Koch network exerts a strong gravitational pull on many Republican candidates and officeholders, re-setting the range of economic issues and policy alternatives to which they are responsive. In our final section, we explore ways to pin down the impact of the Koch network on the overall trajectory of U.S. politics and policymaking.

A Revamped Republican-Conservative Universe

Data from our larger project identify shifts during the 2000s in the universe of national U.S. Republican and conservative organizations. From media and scholarly sources we assembled the list in Appendix A of key conservative and GOP organizations operating at (one or both of two junctures) in 2002 and 2014. Budget data were recorded in those nonpresidential election years (or in the nearest non-presidential year if data were not available for 2002 or 2014) so that our measures would tap underlying, rather than temporarily inflated, organizational capacities. Budget numbers are used as an indicator of total annual resources for all types of organizations, with one exception. For the non-party funding groups, “budget” has a distinct meaning, because we do not want to measure just the core staffing of these groups. To get at the total donor resources these groups deploy, we record for the relevant years the sums from wealthy donors the groups reportedly directed. Our list includes five major types of Republican/conservative organizations:

Political party committees—including the Republican National Committee, the Senatorial and Congressional campaign committees, and the committees funding campaigns across state legislative and gubernatorial contests.

Non-party funders—organized consortia that raise money from many rich donors and channel it into multiple campaigns and political efforts—such as Karl Rove’s American Crossroads PAC as well as the Koch seminars. This category does not include political action committees for individual candidates.

Constituency organizations—that claim to speak for and mobilize broad constituencies, including business associations, the National Rifle Association, the Christian Coalition, and Americans for Prosperity.

Issue advocacy organizations—professionally-run groups that lobby on behalf of specific kinds of policies, such as anti-abortion and anti-tax groups.

Think tanks—such as the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, and the American Enterprise Institute.

Before we proceed, it is important to be clear about what we think our organizational lists do—and do not—signify.Footnote 12 We use annual budgets simply to indicate the relative order of magnitude of organizational clout, and we add up budgets for organizations in each major category to give a rough sense of the resources controlled by various types of party and non-party political organizations in 2002 and 2014. But our organizational lists and budgets cannot capture all partisan resources on the right. Arguably, Republicans and conservatives in the 2000s benefit greatly from openly-partisan commercial media outlets, including the Fox television network and right-wing talk radio, yet those commercial media organizations are not included in our list.Footnote 13 Another consideration to bear in mind is how organizational universes fit into the U.S. economy. In our larger project, we include national labor unions as “constituency mobilizing organizations” on our Democratic/liberal universe list; and the Republican/conservative list used here includes the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Business. But the Republican/conservative list does not include local and regional chambers of commerce or other trade groups, and it also leaves aside individual corporations, some of which operate their own lobbying shops and PACs—and even mobilize their employees into politics.Footnote 14 Also not included are evangelical church networks that figure greatly in conservative political communication and mobilization in rural and suburban communities all over the country. In short, our organizational list does not exhaust all of the resources available on the right—and, of course, secret and untraceable donations are not captured by this approach that relies on public records.

With all necessary cautions, the analysis of our data in figure 1 suggests striking findings about the shifting Republican/conservative organizational universe of the 2000s. We see sharp shifts in the organizational channels through which political resources flow, with the share of resources directly controlled by the GOP committees dropping sharply, while extra-party funding consortia and other political organizations not run by the Republican Party have growing resource clout. In particular, the Republican Party has lost considerable ground compared to extra-party consortia of conservative donors—consortia that are, in turn, beefing up extra-party think tanks, constituency mobilizing organizations, and utilities of the sort that the institutional party has traditionally controlled.

Figure 1 Shifting organizational resources on the right

Notes: Figure shows budget shares for 2001–2002 and 2013–2014 by organizational category; refer to Appendix A for full listing of included organizations and budgets.

Crucially, the resource shifts on the right portrayed in figure 1 have largely occurred through the rise of new far-right organizations instituted after 2002, not through increases in the resources controlled by older groups. If we tracked only the budgets of organizations that existed continuously from 2002 to 2014, we would still see a reallocation (principally from Republican Party committees to constituency mobilizing organizations); but the share claimed by extra-party funders grew only from 6 percent to 10 percent among longstanding groups. Shifts are much more dramatic, however, when organizations launched after 2002 are included, as they are in figure 1. When both longstanding and post-2002 groups are included, the resource share controlled by GOP committees plunged from 53 percent of the Republican/conservative pie in 2002 to just 30 percent by 2014, just as the share of the pie deployed by old and new extra-party funders burgeoned from 6 percent in 2002 to 26 percent by 2014.

Who are the new players driving most of the shift in resource flows away from official Republican Party committees? A variety of recently launched organizations have certainly gotten into the action, including American Crossroads, Heritage Action, and the Senate Conservatives Fund. But the most resourceful new political organizations built on the right in recent years are tied to the wealthy industrialists David and Charles Koch and their close political associates in ways we are about to specify. In Appendix A, the 2002 and 2014 organizational lists for the right universe present the names of organizations we regard as part of the core Koch network in bold blue color. Clearly, many of the new conservative organizations formed between 2002 and 2014 are Koch operations we will soon describe more fully—including Americans for Prosperity, the Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce, the Koch seminars, the Libre Initiative, Themis/i360, Aegis Strategic, and others. When we add up the numbers, three-quarters (76 percent) of all of the budgets of organizations on the right newly created since 2002 turn out to be controlled by the Koch operation. Remarkably, more than four-fifths (82 percent) of the new money attributed to extra-party collective funders flows through the Koch-affiliated consortia launched after 2002.

Deciphering the Koch Network

Dramatic resource shifts on the organized U.S. right cannot be understood without a clear understanding of the Koch network—what it is, how it has evolved, what it aims to accomplish, and how it functions. As we are about to elaborate, the network is about more than individuals, yet it is spearheaded by two ultra-conservative billionaire brothers, David and Charles Koch, who have recently become celebrities—at first reluctantly after they were outed by the media, but more recently because Charles, especially, has embraced public fascination by giving regular interviews and because selected reporters have been invited to attend Koch-organized donor gatherings.Footnote 15 Political scientists have not so far done much research on Koch political activities, apart from including the brothers themselves in studies of wealthy individual electoral donors.Footnote 16 Since 2010, however, advocacy groups and journalists have issued detailed reports that portray the Koch operation as a major new political force in the United States.Footnote 17

But what kind of force? Explicitly or implicitly, the Koch network is usually treated as a corporate dark-money “front group” shoveling funds through dozens of conduits and conservative groups into national elections. A typical portrayal is the “Maze of Money” chart created by Open Secrets to display a spider-like web of some $400 million in 2012 election funding said to be directly or indirectly connected to the Kochs.Footnote 18 In the post-Citizens United era, political donations are often routed through secret channels, so charts like this one necessarily miss a great deal. But, ironically, they also lead observers to see “Kochtopus” tentacles in almost every conservative group or cause, ranging from longstanding mainstays like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Rifle Association, and Christian right groups, to temporary fronts set up to pay for political advertising during one election season.Footnote 19

Taking a different approach, our project hones in on major politically-engaged organizations founded by the Kochs and directly controlled by leaders they install or back. Figuring out which organizations, exactly, fit this definition presents some challenges, because indirect control mechanisms are sometimes used.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, careful students of the Kochs and their political activities agree that the organizations depicted in figure 2 are all key parts of the evolving network (see Appendix A for the budgets of these groups and Appendix B for brief descriptions of them).Footnote 21 Much can be learned simply by arraying these core Koch organizations chronologically and sorting them according to their major purposes and modes of activity. This straightforward step for any historical-institutional analysis offers a coherent picture of the major phases of Koch network-building and enables us to put the post-2000 developments in their full context.

Figure 2 The evolution of Koch core political organizations

Notes: Blue bars indicate idea organizations and think tanks; yellow bars indicate policy advocacy organizations; green bars indicate donor coordination organizations; red bars indicate constituency mobilization organizations; and purple bars indicate political utilities.

As the timeline in figure 2 shows, the roots of Koch-orchestrated political activity go back many decades. Charles and David Koch take ideas seriously and believe that politicians “reflect” rather than create “the prevalent ideology,” so they started out as major backers of the nation’s leading libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute, founded in 1977.Footnote 22 In the 1980s, they became continuous sponsors of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, which does policy studies and runs educational programs, plus the Charles G. Koch Foundation, which disburses grants to college and university-based scholars and supports programs to encourage free-market ideas and policy proposals.Footnote 23 During the 1970s, Charles and David Koch also supported the Libertarian Party; and David even ran for Vice President on the party’s 1980 ticket. But after this foray made little headway, the Kochs turned to backing more conventional organizations that raised corporate contributions to influence policymaking through lobbying, and increasingly, public outreach.

In this second phase of Koch network building, Citizens for a Sound Economy (CSE) was started in 1984 to press for tax and regulatory cuts on behalf of corporate clients.Footnote 24 It functioned until 2004 when the organization split apart in a fight between the Kochs and the organization’s erstwhile chairman, Dick Armey.Footnote 25 During the Bush-senior presidential administration of the 1990s, the Kochs also sponsored the 60 Plus Association to press for privatization of Social Security and health programs for senior citizens as well as the elimination of the estate tax. In recent years, this group has campaigned against President Obama’s health reform law.Footnote 26 Additional advocacy operations took to the field during the early Obama administration, including the American Energy Alliance that opposed environmental regulations and cap and trade legislation, as well as the Center to Protect Patient Rights that fought the health reform effort.Footnote 27 Later, the Center also served as a conduit used by many wealthy Koch-connected donors to fund election efforts against the Obama Democrats—so much so that this group for a few years straddled two of our categories by doing donor coordination as well as advocacy.Footnote 28

The longstanding proclivity of the Kochs to recruit and orchestrate other donors is perhaps the clearest reason why it is misleading to regard them simply as individual wealthy industrialists throwing around their inherited and earned money. As the heirs of a privately held, very successful corporate conglomerate, the brothers have always been in a position to think big; and as individuals who take philosophical and normative ideas as well as material interests very seriously, they envision political change in a multifaceted and long-term way. With Charles in the lead, the brothers have accordingly gone far beyond the tactics of other super-wealthy philanthropists. Not content with scattering donations to disparate institutions and causes run by others, they have moved through phases to build their comprehensive political network—and their latest efforts, the third phase, took shape in the 2000s, when organizations specializing in donor coordination and constituency mobilization were added to the earlier mix of think tanks and advocacy groups.

Starting in 2003, the Kochs began to convene twice-yearly donor “seminars” at which invited wealthy people, chiefly business leaders, are exposed to ultra-free market and libertarian ideas as well as to practical political strategies. At first, these Koch seminars were tiny, intellectually ponderous affairs; but after 2006 interest and attendance steadily grew.Footnote 29 By 2010, more than 200 wealthy invited donors attended the seminars, often in husband-wife pairs, and by now attendance reportedly exceeds 500.Footnote 30 In 2012, the Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce took over the organization of these events.Footnote 31 Formal rules were put in place, requiring guests to pledge a minimum of $100,000 per year to Koch endeavors in return for the right to participate in the Koch seminars. Twice each year, donors assemble for several days at posh resorts under tight security to socialize and listen to presentations by conservative intellectuals, media people, and leaders of core Koch political organizations.Footnote 32

Some sessions at the biannual seminars amount to auditions for invited GOP candidates, including Congressional leaders Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell; governors like Scott Walker and Chris Christie; Senate candidates like Cory Gardner, Tom Cotton, and Joni Ernst; and assorted presidential hopefuls.Footnote 33 Koch organizations do not, as such, endorse particular candidates; instead, they deploy what is arguably a much more effective tactic by encouraging politicians to compete to prove that they can be effective spokespersons for, and executors of, the Koch agenda. Because the Koch seminars attract many wealthy supporters, politicians covet invitations and are glad to audition for the guests.

But the seminars are not chiefly about politicians. Primarily, they foster like-mindedness and camaraderie and focus the assembled millionaires and billionaires on supporting the larger Koch network. Carefully-choreographed panels are staffed mainly with speakers from Koch-run political organizations, who can thus present accomplishments and strategies to existing and potential donors. In addition, corralling several hundred wealthy conservatives in one place for several days creates opportunities for the Koch network leaders to schedule small consultations between invited attendees and principals in other Koch organizations. Of course, full information on such encounters is spotty, because seminar programs and lists of attendees are supposed to be kept secret. But documents have leaked from time to time, including full Koch seminar programs for the spring of 2010 and the spring of 2014, plus a sheet from the winter 2014 seminar (found crumpled up in a hotel room) giving a full list of individualized “one-on-one” sessions between Koch organization leaders and potential donors in attendance.Footnote 34

Our research team has analyzed all these seminar documents and finds that the same types of Koch organizational leaders hold most panel speaking slots and participate in the one-on-one donor meetings.Footnote 35 Beyond Charles and David themselves, featured honchos include other top officials from Koch Industries and Freedom Partners. They also include leaders from the Mercatus Center and the Koch Foundation, highlighting the enduring stress the network places on investments in ideas, research, and higher education. Last but not least, leaders who speak and meet with seminar donors come from the newest Koch political organizations launched to mobilize conservative activists and U.S. citizens for issue campaigns and elections.

In the 2000s, such political organizations have become, along with the donor seminars, the centerpiece of the most recent third phase of comprehensive Koch network building. As the following section will elaborate, the most extensive and pivotal effort has been the construction since 2004 of the general-purpose advocacy and constituency mobilization federation, Americans for Prosperity, which deploys a combination of advertising, lobbying and grassroots agitation during and between elections.Footnote 36 More recently, specialized organizations have been added to do outreach to particular constituencies. Concerned Veterans for America was launched in 2012 to address military veterans’ issues—and to push for privatization of the Veterans Administration.Footnote 37 Veterans are seen as a natural conservative constituency, yet the Koch network has also launched organizations to reach into constituencies that liberals presume are on their side. Since 2011, Generation Opportunity (“GenOpp”) has targeted young people.Footnote 38 And the fast-expanding Libre Initiative was instituted the same year to do community outreach as well as political agitation among Latinos, with efforts especially targeted in electoral swing states.Footnote 39 Finally, Koch election efforts have very recently been bolstered by general-utility organizations. Themis/i360 is a combined for-profit and non-profit operation that has worked since 2010 to develop and deploy real-time digitized data on conservative voters and activists—resembling Catalist on the left.Footnote 40 And Aegis Strategic, a consulting organization, was founded in 2013 to identify and support the nomination and election of very conservative candidates (such as Joni Ernst, who was recruited and supported to run, successfully, for the open 2014 Senate seat in Iowa).Footnote 41

The newer as well as older Koch political organizations are deeply intertwined with the family-run industrial giant, Koch Industries. This Wichita-headquartered international corporate empire is, of course, the source of Charles and David’s stupendous wealth. Beyond that, members of the inner cadre of political network leaders, including Rich Fink, Mark Holden, and Marc Short, have all served in Koch Industries management; and other staffers have cycled back and forth between the political groups and the corporation.Footnote 42 Management and organizational strategies developed at Koch Industries have been applied to the political network—including the deployment of subsidiaries and enforcement of accountability through rigorous internal audits and “market-based management,” where each staffer is responsible for showing measurable results.Footnote 43 Koch Industries includes a governmental affairs division that shares priorities, resources, and personnel with network political organizations. The corporation’s lobbyists and staffers often work hand in glove with the political network on legislative campaigns. And Koch Industries funds allied organizations, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council.Footnote 44

A final point about the overall Koch political network is worth emphasizing. Typically, media pundits and Democrats portray the Koch network as a reaction to President Barack Obama, but the unfolding phases of network development we have just reviewed make it clear that the Kochs and their cadre have pushed political change for decades. At least since the 1990s, moreover, they have taken ever more extensive steps to reorient and leverage the Republican Party. Highly critical of increased public spending and other moves under President George W. Bush, the Kochs set out to build clout apart from Karl Rove, the Bushes’ chief political consultant, and pull the Republican Party toward the ultra-free-market right.Footnote 45 Indeed, the post-2002 resource shifts on the U.S. right that we noted earlier are in significant part due to the latest Koch undertakings—especially the Koch seminars, Freedom Partners, and the buildup of Americans for Prosperity, the 800-pound gorilla of the reorganized U.S. conservative universe.

The Growth and Unique Features of Americans for Prosperity

Along with a coordinated nonprofit foundation led by the same board, Americans for Prosperity was set up as a 501c4 organization in 2004, following the break-up of Citizens for a Sound Economy and just as the Kochs were getting their donor seminars under way. By 2005, the Kochs signaled bold ambitions for AFP by recruiting Tim Phillips, a former Christian right organizer, to direct and vastly expand the operation at both national and state levels. As figure 3 shows, AFP’s growth was remarkable even before Barack Obama launched his run for the presidency. As indicated by the deep purple coloring on the map, by the end of 2007 AFP already had paid state directors permanently installed in 15 states encompassing almost half the total U.S. population and their representatives in Congress. Well before Democratic sweeps in the 2008 elections, AFP organizations were ensconced not just in conservative regions but also in the electorally-contested Midwest and Upper South.

Figure 3 The rapid growth of Americans for Prosperity

Notes: Sources include archived AFP webpages (from the Internet Archive) and media reports.

Our project uses a unique, laboriously-assembled data set to track the growth of AFP. In recent years, the AFP national website includes a menu linking to what are called state “chapters.” But not all of those so-called chapters have actually had any continuous staffing. To get at solid organizational foundations, we use the presence of a paid state director to determine whether AFP in a given state amounts to more than just names on a national list or temporary field staffers deployed from neighboring states for a specific election or policy campaign. To determine the names and terms of paid state directors, we have collected information from earlier AFP website postings archived on the Internet “Wayback Machine.” Using contemporaneous lists along with real-time announcements of the arrival and departure of AFP state directors allows us to track where and when interruptions occurred in AFP expansion.

Like most organizational heads, AFP leaders tend to portray their federation as always growing and never experiencing any setbacks; and in prospectuses prepared for donors, they offer bold projections of future growth. But real-time analyses show that AFP has, from time to time, fallen short of projections and has even disbanded staffs in certain states. For instance, the state of Oregon had paid state directors from 2007 to 2013 before AFP closed shop there.Footnote 46 Directors were implanted only temporarily in North Dakota (2006–2007), Maryland (2009–2011), Washington (2010–2011), and Connecticut (2011–2012); and AFP organized New Mexico only very briefly in 2012–2013.Footnote 47 In addition, as of 2015 ten states have never had paid AFP directors—in a mix of large liberal states and small very conservative states. Even with ups and downs spelled out, however, the nationwide reach attained by AFP is truly remarkable. By 2015, it had paid directors in 34 states encompassing four-fifths of the U.S. population. In addition, AFP carries on its master contact lists many conservative activists who reside in the states where it does not have a paid staff presence.Footnote 48 Each year AFP announces plans for further expansion and, according to Politico’s Kenneth Vogel, intends to have staffing up and running in all but eight states by 2016.Footnote 49

For the period from 2004 through 2015, the data table included in figure 3 tracks the overall growth in affiliated volunteer activists, budgets, and total staffing (using lists or media reports that include national staffers as well as state staffs). Every indicator points to a sharp upward growth trajectory—with the caveat that the ranks of volunteer conservative activists in regular contact with AFP have grown only gradually since 2013, from 2.3 to almost 2.5 million, while paid-staffing levels have grown more sharply across the federation as a whole. As AFP has marshaled generous donor resources from the Koch network, its ratio of paid staffers to volunteer activist contacts has grown. AFP is becoming steadily more top-heavy across the board. What is more, the national headquarters now raises and deploys major resource “surges”—infusing money for advertisements and bevies of temporary field operatives to bolster election campaigns and policy battles in pivotal states such as ColoradoFootnote 50 and Florida.Footnote 51

Basic organizational growth aside, how does Americans for Prosperity actually function as a political operation? In highly unusual ways, it combines features that are often found separately: Americans for Prosperity is centrally directed yet federated; it impacts both elections and policymaking; it combines insider lobbying with public campaigns and grassroots activation; and—perhaps most important of all—AFP enforces its own highly disciplined policy agenda but at the same time is thoroughly intertwined with the Republican Party. Each of these combinations of features and functions deserves elaboration because, taken together, they explain how AFP has become a massive cadre-directed operation capable of reorienting the priorities of the Republican Party.

AFP’s unique combination of corporate and federated organization is its most striking feature. Like a privately-held corporation, AFP is a fully national organization, directed from above by centrally-appointed managers operating from their headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. National managers oversee functions such as fundraising, policy, and web communications—and in recent years, AFP has also proliferated regional managers who shepherd groups of states. Along with the AFP board, director Tim Phillips and his top lieutenants obviously have complete authority over personnel and resource allocations. Over-time tracking shows that AFP officials are appointed and removed at will and regularly moved around. Likewise, managers shift between AFP and other core Koch organizations. Top AFP leaders direct special infusions of funds into various functions and states—for example, into big advertising buys during key Senate election battlesFootnote 52 or into hot campaigns to block Medicaid expansion in particular states.Footnote 53

But even though AFP is highly centralized like a corporation, it also has a federated structure with important state-level organizations, just like classic American voluntary associations and the U.S. governmental system as a whole.Footnote 54 Directors and other paid staff members such as “grassroots directors” are installed in most of the states and given considerable room to monitor and influence state and local politics and to weigh in locally with their state’s U.S. Senators and Representatives. State-level AFP officials remain beholden to national leaders, however. Although AFP usually appoints directors who have experience and longstanding ties in their states, these pivotal players are not selected by in-state activists. National AFP president Tim Phillips usually announces the arrival and departure of state directors; and regardless of varied career backgrounds (which we will discuss later) all AFP state directors, along with all other AFP employees, push a locally-adapted version of the standard AFP agenda using well-honed organizational routines.

To get a picture of lineages of state directors over more than a decade, our project has gathered data on 58 AFP state directors (including 45 men and 13 women, all whites) who served between 2004 and 2015 in the first 15 AFP states. The states in this database are Kansas, North Carolina, and Texas, where AFP was organized starting in 2004; Virginia and Wisconsin starting in 2005; Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, and Oklahoma, starting in 2006; and Arizona and Florida, starting in 2007. Of the 43 directors in these states who have completed their terms, the average time in office was 20.9 months (although some stayed in office for many years, while a small number moved on after just a few months, including some who seem not to have liked the work or who performed poorly and were removed by the national AFP managers).

State director is an important and pivotal position in the AFP federation. Once in place, state directors not only coordinate the eclectic mix of AFP activities we are about to describe. They also apparently have considerable authority over appointments of deputies and functional directors in their state. The numbers of additional paid staffers varies greatly from state to state, and may depend in part on local fundraising, not just budget grants from national headquarters. In interviews with experts and from the public record, we have found indications that AFP state directors are, where possible, responsible for raising donations from local activists and wealthy donors.Footnote 55 We also note that AFP recently advertised a job opening for a Senior Regional Development Officer, who is supposed to “cultivate and solicit individuals for contributions to support states in their assigned region as well as national efforts.” Furthermore, in some longstanding, generously-staffed states, in-state conservative donors like Art Pope in North Carolina and the Bradley Foundation in Wisconsin seem to have virtually adopted the local AFP affiliate.

In another distinctive combination, Americans for Prosperity conducts political activities between as well as during elections, maintaining a continuity of effort that its leaders proudly tout in public statements and private pitches to potential donors.Footnote 56 To be sure, AFP budgets and expenditures balloon during election years, as national and state operatives channel major funding into advertisements, especially for presidential contests and key Senate races such as the 2014 races in Iowa, North Carolina, Colorado, Arkansas, and Louisiana. In addition, AFP deploys extra funds and personnel to do voter contacting and turnout in key states, as it reportedly did in Florida in 2014.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, AFP is not a mere pass through for electioneering monies.

Year to year, AFP mounts policy campaigns and maintains lobbying and grassroots pressure on legislators and public officials, especially in state legislatures. During battles in the states over Medicaid expansion under ObamaCare, for instance, AFP state directors issued press releases, pressured legislators, and mounted “grassroots” protests.Footnote 58 And the same sort of thing happens in other state-level fights over highway funding, taxes, and funding for education and social policies, as well as in battles over right-to-work legislation and curbs on public-sector unions (which we will discuss further later). In all such battles, AFP organizations work closely with the local legislators enrolled in the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and with conservative free-market think tanks operating in the State Policy Network.Footnote 59 In addition, many AFP-organized states put out annual “scorecards” to track votes by members of their own state legislatures, as well as publicizing the scores assigned to their state’s Congressional contingents by the national AFP scorecard of votes in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. AFP has released national Congressional scorecards since at least 2007, showing that GOPers in the House and the Senate have voted with AFP most of the time across all sessions—with compliance rising from 73 percent in 2007 to 88 percent in 2015.

This brings us to the third way that AFP combines typically separated functions—by synchronizing staff-led lobbying and publicity efforts with mobilization of volunteer citizen activists. Most AFP-organized states have grassroots directors of some sort, whose responsibilities include maintaining lists of conservative activists, communicating regularly with them, and putting out calls for public demonstrations from time to time—such as a protest staged at a legislative hearing about a controversial piece of legislation. Overall, AFP claims to enroll close to 2.5 million activists nationwide—including tens to hundreds of thousands of them in each state. Grassroots members are signed up even in states without paid directors. Yet it is important to understand what activists do—and do not do—in the organization. No doubt, AFP managers pay attention to the ideas and passions of conservative voters and activists; and they certainly try to build and update contact lists so rank-and-file conservatives can be contacted for issue campaigns, turned out on Election Day, and urged to donate to AFP (which can then proudly proclaim that it has large numbers of “small donors”). But in no sense is AFP controlled by citizen “members.” Voluntarily-affiliated citizens do not elect AFP leaders; they do not provide the bulk of organizational funding; and they do not determine AFP public messages or issue agendas. Wealthy donors and centrally-orchestrated managers within the Koch political network perform all of those directive functions.

Now we get to the heart of the matter: what AFP aims to accomplish and how it relates to other conservative organizations and the Republican Party. In essence, AFP is autonomous and directed from above, yet at the same time it is sufficiently intertwined with the GOP at all levels that it can pull party agendas steadily rightward. AFP pursues a broad pro-free-market agenda with a highly-disciplined focus on economic and political issues, avoiding controversial social policies like gay marriage, abortion, and immigration as much as possible. Like earlier free-market advocacy groups, it pressures and pulls Republican candidates and officeholders to follow its preferred agenda. But unlike earlier kindred organizations, AFP pursues a broader set of priorities and engages in a more integrated array of political activities across multiple levels of government. It more closely resembles a European-style political party than any sort of specialized traditional U.S. advocacy group or election campaign organization. Yet AFP is not a separate political party. It is, instead, organized to parallel and leverage the Republican Party, because it overlaps with the party but is not subsumed within it or beholden to GOP officials. With a disciplined focus on its own agenda, AFP leverages Republican candidates and officeholders and pulls them to the far right on political-economic issues.

In some ways, AFP’s connection to the GOP is similar to the “anchoring” relationship that the labor movement used to enjoy with Democrats.Footnote 60 Like AFP, the labor movement at its mid-twentieth-century peak was a federated operation that combined rank-and-file members with national leadership (although many unions gave ordinary members more democratic control than AFP has ever done). Like AFP, organized labor sought to pull the whole Democratic Party to the left on economic issues by supporting favored candidates and policies at all levels of government. Indeed, from time to time, AFP leaders openly acknowledge that their organization is self-consciously built to parallel and counter unions, especially public-sector unions. In a revealing interview with the New York Times, AFP’s chief executive recently explained that labor’s influence was “unmatched by anything on the right” a decade ago, but now AFP is “spreading the message through the same means.”Footnote 61 Of course, in recent times most unions have experienced sharp declines in membership, resources, and clout within the Democratic Party orbit, while AFP is growing rapidly and exercising greater influence over the GOP.

On which issues does AFP exert that influence? Our project has not yet assembled a full data set coding issues mentioned in AFP press releases and on AFP websites, over time both nationally and in the various states. But hundreds of hours spent on AFP websites past and current allow us to say, with confidence, that this organization exercises tight control over the policy goals its operatives pursue and discuss in public. The clearest evidence lies in the fact that AFP public communications have always been centered in a single website, whose format and content is quite standardized and obviously managed from above. State organizations have their own dedicated webpages and some include state-specific content—for example, news updates about upcoming public events or legislative battles in that state. But on both the national and state-specific portions of the AFP website, the range of issues covered is highly standardized. Even state and regional media coverage of local AFP efforts follows pretty much the same script. Using almost identical phrasing, AFP directors are quoted parroting their own local versions of the organization’s mantras about limited government, free markets, and individual liberty.

Another important indicator is provided by the national AFP Congressional scorecards issued by the group. Like all scorecards, these record each Senator’s and Representative’s votes on selected issues, indicating whether those votes reflect or fail to reflect AFP preferences. On these widely-disseminated scorecards, AFP does not track all conservative priorities but instead focuses on votes in policy areas of core concern to the Koch network—votes on bills about budgets and spending; energy and the environment; health care and entitlements; taxes; labor, education, and pensions; banking and financial services; property rights; and technology. This evidence about scorecard categories dovetails perfectly with the emphases we see on AFP webpages about state-level issue campaigns and legislative monitoring.

On webpages, in statements to the media, in lobbying efforts, and at public protests, messages from national and state AFP operatives focus relentlessly on promoting tax cuts, blocking and eliminating business regulations, opposing the landmark health-reform law passed in 2010, pushing for reductions in funding of (and, where possible, the privatization of) public education and social-welfare programs, and opposing state-level environmental initiatives and any from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In these respects, the AFP agenda aligns with long-standing anti-tax and ultra-free-market groups like the Club for Growth and Americans for Tax Reform, as well as with the priorities pushed by the conservative activists and corporate interests operating through ALEC to shape state legislation. In addition, like many of these other organizations, AFP works to undercut private and public-sector labor unions and reduce the ranks and rights of public employees. And AFP state organizations often support bills and administrative measures to restrict easy voter registration, cut back on voting days and hours, and generally make it difficult for young and minority people to vote. AFP is a fighting organization that works, relentlessly, to shrink government, reduce economic regulations and redistribution, and disempower liberal and Democratic constituencies.

As we have learned from career histories and news coverage, many AFP leaders (as well as grassroots supporters) are Christian conservatives opposed to abortion and gay marriage, and quite a few activists involved with AFP want to restrict immigration. But these “social issues” are not core AFP concerns. As an organization, AFP does not take stands on most hot-button social issues or give much, if any, public attention to them. Especially in conservative states, AFP definitely cooperates in elections and issue campaigns with gun-rights groups, Christian right groups, and even immigration restriction groups. On an ad hoc basis, AFP joins typical conservative alliances. But AFP itself keeps the focus on the Koch network’s core economic and political priorities.

Should we, then, conclude that AFP is just another ultra-free-market advocacy group? Does AFP simply add capabilities for citizen outreach to such longstanding, elite funded and top-down operations as the Club for Growth and Americans for Tax Reform (ATR)?Footnote 62 In part, the answer is yes—AFP does add important new capabilities, especially via its many state-level organizations. But AFP also appears to have a different relationship to the Republican Party. In classic advocacy-group modes, the Club for Growth and Americans for Tax Reform are run by separate sets of professionals and push on the GOP from the outside, usually at the national level. AFP, in contrast, is organized as a federation that parallels the political parties and, especially in its state organizations, turns out to be thoroughly intertwined with the Republican Party in both elections and governance.

Early in our research, we imagined that AFP’s ability to pressure Republican candidates and officeholders might be due to its separate organization; that AFP, like the Club for Growth and ATR, might work through career staffers to punish and reward Republicans according to their fealty to the Koch agenda. Information we have collected on career trajectories shows that Club and ATR staffers rarely come from Republican positions or move on to such posts. Club and ATR staffers tend to pursue careers within the world of conservative lobbying groups. In contrast, AFP state directors—the paid staffers at the frontline of AFP’s political operation—pursue careers that are thoroughly intertwined with the Republican Party.

As mentioned earlier, one of our data sets tracks careers of AFP state directors. By looking at the original 15 AFP states, we could track the careers of AFP state directors over many years, using organizational biographies, LinkedIn profiles, and media accounts to see what kinds of posts those staffers held before they were first appointed at AFP and what kinds of positions they moved on to hold after their stints as AFP state directors. (In addition, we have gathered information on the prior career posts held by all 34 state directors in office as of the late summer of 2015. For reasons of space, these data are not reported here, but the earlier careers for current AFP directors align closely with the longer-term findings we report for the earliest organized states).

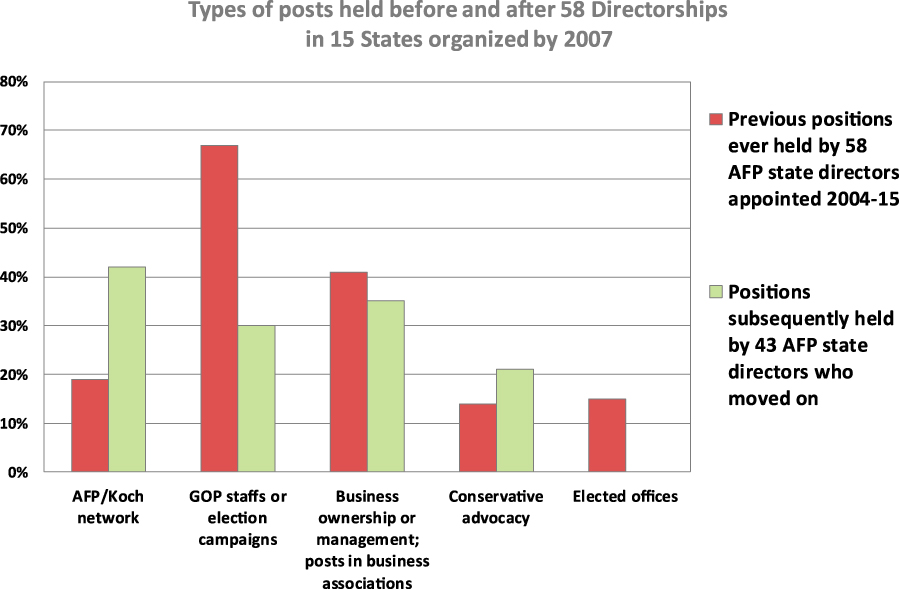

From figure 4 and the background data, several patterns stand out:

Quite a few AFP state directors are promoted from within the federation. Deputy directors often move up to state directorships and, even more frequently, former state directors move up to higher-level AFP posts (to become, for example, regional directors or managers in the national office) or end up in top posts in other Koch organizations. The Koch network has created a substantial internal labor market.

Many AFP state directors come from—and later move on to—other key positions in the conservative world, including top posts in businesses and business associations and in conservative advocacy groups. The business posts are usually not in corporations, however; they are typically ownerships of political consulting or public-relations firms that work especially for GOP clients.

Tellingly, figure 4 reveals that a very high proportion of AFP state directors held earlier positions in GOP election campaigns or on the staffs of Republican legislators and executives; and after their AFP stints many have also moved on in due course to such posts. Two-thirds of AFP directors have had earlier career experiences on Republican staffs. And close to one-third of state directors moved on immediately or later to positions in GOP campaigns or staffs. Often these post-AFP jobs in the Republican Party are very significant positions such as legislative staff directors or heads of presidential or senatorial campaigns. In addition, as previously noted, many prior and post-AFP career stops are in businesses serving Republican clients.

Figure 4 Careers of state directors for Americans for Prosperity

Notes: Data on directors for 15 earliest AFP state organizations: KS, NC, TX from 2004; VA, WI from 2005; CO, MI, MO, NJ, OH, OK, GA, IL from 2006; AZ, FL from 2007.

These data show that the AFP federation has been able to penetrate GOP career ladders and recruit experienced, knowledgeable Republican staffers, usually young men in their thirties or forties, into pivotal positions as state directors in its own parallel organization. This penetration of Republican career lines brings clear-cut advantages to Americans for Prosperity—and to the Koch network as a whole. AFP recruits with GOP experience have valuable knowledge and connections to party circles within each state. They know who counts in Republican politics, legislatures, and governors’ offices, and their savvy makes it easier for AFP to mount well-targeted lobbying efforts and issue campaigns. AFPers who have worked in GOP positions also know the strengths and vulnerabilities of each state’s Republican “establishment,” which of course greatly helps AFP to gain leverage during legislative battles. In addition, when former AFP state directors later move into Republican posts—by directing election campaigns, working as political consultants, or managing governing staffs—chances are that many of them will further AFP agendas and help drag the Republican Party as a whole further to the right on political-economic issues.

Overall, AFP exhibits an ideal combination of autonomy from, and embeddedness within, GOP circles, a unique situation that helps the Koch network serve as an ideological backbone and right-wing force for today’s Republican Party. This happens not only because the Koch network throws a lot of money around, and not even because it threatens politicians with sanctions if they stray from the Koch agenda—tactics that other groups, like the Club for Growth and ATR, perfected long before AFP emerged. Rather, the most pervasive and subtle form of leverage by the Koch network on the Republican Party happens because of the flow of people back and forth between the two operations.

A concrete example nicely dramatizes how AFP’s parallel and intertwined organization can help the far right prod and pull Republicans and powerfully affect policy agendas and outcomes. In the November 2012 elections in Tennessee, a campaign operative named Andrew Ogles led successful efforts to elect Republicans to super-majority control of the state legislature. In early 2015, Bill Haslam, the very popular GOP governor of the state who had himself won re-election by an overwhelming margin, pushed a proposal to adopt a conservative variant of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. This proposal had strong backing from Tennessee hospitals and health care businesses, as well as from the state’s Chamber of Commerce. But Tennessee’s far right was firmly opposed to the expansion. Backed by resources from national AFP headquarters, an all-out campaign to block legislative approval of Haslam’s proposal was spearheaded by the state AFP organization—led by its recently-appointed state director, none other than Andrew Ogles. In a short span, Ogles went from electing Republicans to full control of the Tennessee legislature to targeting many of those very same legislators with retribution when they showed any openness to expanding Medicaid—not just lobbying them, but also unleashing radio ads and door-to-door canvassers. In a very short time, Governor Haslam’s proposal died in the legislature.Footnote 63 Obviously, AFP-Tennessee Director Ogles knew exactly how to leverage the very Tennessee GOP legislature he had helped to elect; and his expertise and leadership allowed AFP, working with other right-wing groups, to re-set the legislature’s agenda and undercut the Republican governor’s willingness to compromise with the Obama administration.

Assessing the Impact of the Koch Network on Politics and Policy

Figuring out whether political organizations actually have a specific net impact on election outcomes, public agendas, and public policies is one of the most difficult challenges analysts face—and our project is still in the early stages of trying to trace and pin down the precise impact of the Koch network on the Republican Party and on U.S. politics and public policymaking more generally. One important research possibility we have not yet pursued is a systematic study of whether in GOP primary elections, candidates with Koch donor support and backing from Koch political organizations do better, overall, than other candidates. Beyond elections, however, governing agendas and policy changes are another important area to explore.

Arguably, given what we have learned about the emphasis the Koch network places on broad and sustained political change, “Koch effects” on the GOP might be stronger in critical policy battles and the setting of governing agendas than in elections. From the Koch network perspective, using a combination of carrots and sticks, as well as resources and ideas, to inspire already-sitting GOP officials to avoid certain policies and support others is an even more efficient way to shape U.S. politics than battling it out election by election to change GOP officeholders. Furthermore, because of the massive resources the Koch network is able to raise and deploy, a more global and long-term strategy is possible.

In this section, we introduce preliminary empirical evidence suggesting that Koch network operations have contributed to growing gaps across issue-areas between GOP policy stands and majority citizen preferences—and occasionally to rifts between Republican priorities and the policy preferences of mainstream U.S. business groups well established in the GOP coalition.

In our introduction, we pointed to many issue areas where Republican candidates and officeholders increasingly adhere to unpopular policy stands. All of the discordant policy positions to which we pointed—on issues of taxes, social benefits, climate policy, and union rights—in fact align today’s Republicans with Koch network positions rather than with the preferences of most Americans—and sometimes align GOPers and Koch leaders together against the preferences of key business groups and most Republican voters. However, correlation establishes plausibility, not necessarily causation. Even though the GOP and the Koch network may be aligned in opposition to majority preferences in various policy domains, this does not prove that Koch network efforts are the explanation. To get closer to the causal mechanisms that could be at work—and to point toward agendas for further research—we take a look in the concluding section at several national and state policy arenas where Koch forces have recently wielded growing clout that may well help to explain otherwise puzzling Republican priorities.

Congressional Climate Politics

Global warming politics in Washington, DC, is one such area. Ever since its 1990s campaign against the Clinton’s administration’s proposed “BTU tax,” the Koch network has worked to defeat climate-change legislation.Footnote 64 In addition to financing scientific and policy research that questions the reality of human-induced climate change, the network lobbies Congress aggressively, with AFP in the vanguard.Footnote 65 Adapting a tactic from Americans for Tax Reform, AFP has for some years pushed lawmakers to sign a “No Climate Tax” pledge promising to oppose “any legislation relating to climate change that includes a net increase in government revenue.” This squarely targets any possible carbon tax, a tool for reducing dangerous emissions from burning fossil fuels that is supported by many economists, including some conservatives.Footnote 66 As figure 5 shows, Republicans in Congress have increasingly signed on to the AFP pledge. In the House, pledge signatories have increased from close to half of all GOP Representatives during the 111th Congress to three-fifths of them in the 113th Congress. In the Senate, GOP support has increased even more dramatically, growing from just one-quarter of GOP Senators in the 111th Congress to 56 percent of them in the 113th.

Figure 5 Congressional GOP support for the AFP climate pledge

Are Republicans who sign the pledge simply reflecting public or constituent views? Thanks to the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, we know that the answer is “no,” based on reliable measures of public attitudes about global warming in states and Congressional districts.Footnote 67 As it turns out, even in the constituencies of the GOP representatives and senators who have signed the “No Climate Tax” pledge, majorities of Americans believe global warming is happening—and want to take action to address its ill effects. Across the states and districts represented by legislators who signed the AFP pledge in 2015, an average of 59 percent of Americans say that global warming is happening and an average of 58% believe it threatens future generations (refer to figure 6). Even more strikingly, 73 percent of residents in these districts, on average, support action to regulate carbon dioxide. In this policy realm, AFP—and the Koch network more generally—are clearly urging Republicans to take positions against the beliefs of most of their constituents—including majorities of moderate Republicans.Footnote 68 Only the most conservative GOP voters agree with the stands the Koch network is trying to enforce in the Republican Party.

Figure 6 Constituent support for global warming reforms of GOP signatories to the AFP “No Climate Tax” pledge

Legislative Battles in the States

In state-level policy battles, too, Americans for Prosperity and the larger Koch network have helped to drag the GOP not just into signing pledges but into legislating at odds with public preferences. Here Koch network capacities to leverage Republicans across levels of government become especially relevant, because state legislators and governors are the key players in important fights over the rights of public-sector unions to organize and bargain collectively, and also in struggles about whether to expand Medicaid coverage to the near-poor, using funds from the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

Koch leaders have always strongly opposed public-sector unions, in part because they see all unions as distortions of the “free market,” but also because they understand that public-employee unions promote liberal policies and boost Democratic candidates with contributions and get-out-the-vote efforts. By restricting the rights of public-sector workers to organize and bargain with government, the Koch network can eviscerate a key part of the liberal coalition—and AFP in particular brings new clout to this battle.Footnote 69 Among the most active groups in campaigns for rollbacks and restrictions of public-union prerogatives, AFP state organizations hold rallies, coordinate petitions, and orchestrate contacts between grassroots adherents and state lawmakers.Footnote 70 Often spending extra resources sent from AFP headquarters and Koch donors, state organizations run ads in favor of anti-union bills, help to fund litigation challenging public-sector union rights, and conduct “push-polls” asking distorted questions in order to highlight apparent public support for anti-union legislation.

AFP efforts to curb unions proceed regardless of objectively-measured public preferences. More than two-thirds of registered voters in 2011 told pollsters that they believed states should allow public-employee unions to negotiate for salaries and benefits.Footnote 71 And well over half of American adults opposed efforts by Republican governors to curb collective bargaining rights and cut pay for state employees in the wake of GOP takeovers of many state governments.Footnote 72 We have also examined state-level variations in public support for unions. Drawing on four nationally-representative surveys of adult Americans conducted between February and March of 2011, we estimated the share of adults in each state that supported restricting public-sector union rights to bargain collectively (refer to Appendix C for a summary of our approach to this estimation). Support for restrictions ranged from 31 percent of adults in the District of Columbia to 46 percent of adults in New Hampshire, with the average across all states falling at 40 percent. But variations in public views had little relevance, because union curbs were as readily enacted in states such as Michigan and Tennessee, where people expressed high levels of support for public-employee bargaining as they were in states like New Hampshire and Ohio, where people were much less supportive. In contrast, states with paid AFP directors in 2011, a key measure of AFP’s strength, were substantially more likely to enact restrictions than those without AFP directors in place. Only 15 percent of states without a paid AFP director passed laws cutting public-employee bargaining rights, compared to 48 percent of the states with paid AFP heads (this comparison only includes states that had permitted at least some collective bargaining at the start of the year).

In a full multivariate analysis aimed at accounting for the enactment of state-level restrictions on public-sector union rights in 15 states in the 2011 legislative session, we also controlled for additional factors that might plausibly influence enactments or AFP institutional strength—including the partisan balance in state government (as measured by Democratic control of up to three veto points: the governorship and the state house and senate); overall union density in the state labor force (a good indicator of overall state liberalism and the strength of organized opposition to anti-union measures); and the state unemployment rate (an indicator of economic conditions).Footnote 73 As table 1 shows, in this more complex logistic regression model, the presence of a paid AFP state director increases the probability of a state enacting curbs to public-sector bargaining rights by nearly 30 percentage points, nearly the same effect size as partisan control of government (refer to Appendix C for the full regression results).Footnote 74 Public sector bargaining rights thus seem to be another clear-cut domain in which GOP lawmakers have responded to Koch network priorities rather than public preferences.

Table 1 Predicting retrenchment of public sector bargaining rights, 2011

Notes: Table shows the change in the predicted probability of a state retrenching public sector collective bargaining rights in 2011 legislative session associated with changes in various state characteristics. Other variables held at their means.

N = 44; only states with at least some collective bargaining rights in place at start of year were included.

95% confidence intervals are in brackets.

Some would argue that when it comes to retrenching union rights or supporting other economic policies long backed by business associations, Americans for Prosperity and other Koch groups are simply adding heft to longstanding business crusades. This is true up to a point and makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly how much new clout AFP and other Koch organizations bring to long-running redistributive and regulatory battles. However, in certain policy arenas, we see a growing rift between the Koch-backed far right and business groups that have anchored the GOP since the 1970s.Footnote 75 In Congress, the Koch network has joined players like Heritage Action to encourage conservative Republicans to break with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business lobbies by opposing bills to renew agricultural subsidies, to reauthorize the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and to replenish the Highway Trust Fund.Footnote 76 Similarly, in many states, the Koch network works to defeat business-backed appropriations for highway repairs and infrastructure investments.

Perhaps most tellingly, the Koch network has opposed business associations as well as majority popular opinion in ongoing state-level battles over acceptance of new federal funding to expand Medicaid under the 2010 Affordable Care Act. Even in very conservative states like Utah, Tennessee, Alabama, and Wyoming, GOP governors, along with hospital associations and state Chambers of Commerce, support Medicaid expansion as a way to garner subsidized profits and new revenues for their states. But the Koch strategy calls for all-out opposition to any and all expansions of public social spending. In another publication, we have developed new, organizationally-based empirical measures of right-wing network strength in the states to include in multivariate analyses that weigh the relative impact of right-wing networks and Chambers of Commerce in the choices GOP-led states have made about Medicaid expansion.Footnote 77 In addition, we have tracked intra-GOP battles in state case studies. Both approaches show that right-wing organizations, including AFP chapters, have had a significant impact. In most GOP-led states, governors and business associations want to proceed with Medicaid expansion, but fierce opposition from well-organized right groups usually persuades most GOP state legislators to slam the door.

The Bottom Line: The Koch Network and Rightward Polarization

The evidence we have presented here suggests that the Koch network is now sufficiently ramified and powerful to draw Republicans into policy stands at odds not only with popular views but also with certain business preferences. With massive resources and a full array of political capacities, the Koch network of the 2000s has set up shop on the GOP right and become a powerful shaper of the careers of party operatives and the agendas of Republican politics. Arguably, Koch network pressures and inducements have so effectively influenced GOP politicians that many of them end up vulnerable to populist defections from voters who dissent from or don’t care about ultra-free-market orthodoxies on trade or immigration or slashing elderly entitlements. In the 2016 Republican primaries, Donald Trump was able to maneuver successfully in the yawning gap between the priorities of most voters (including many Republicans and Independents) and the Koch economic orthodoxies embraced by the GOP establishment.

However, we want to be precise about what we are (and are not) arguing here. Although the gap between Koch network goals and the preferences of most Americans is enormous, we do not want to overstate tensions between Koch network priorities and the policy goals of corporate America, particularly as expressed in recent times by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the American Legislative Exchange Council in the states. Because Koch and corporate priorities are largely aligned on matters such as curbing labor unions, reducing taxes and social spending, and weakening government regulation, mainstream business lobbies such as the national and state Chambers of Commerce are very unlikely to oppose Koch-backed Republicans in most elections; and Koch groups will continue to ally with corporate organizations in potent campaigns to weaken government as an agent of inclusive economic growth.Footnote 78

In fact, the reinforcing alignment between business associations and far-right ideological groups like the Koch network may help to explain many of the divergences between public policy outcomes and the preferences of most Americans documented recently in the research of Larry Bartels, Martin Gilens, and Benjamin Page.Footnote 79 In important policy realms, these scholars and others have shown the significant divides between what most American voters want and what government does (or does not) do. Put simply, when Koch organizations, the national Chamber of Commerce, and an array of other ideological and corporate groups call in one loud voice for government cutbacks, upward-tilted tax reductions, and anti-union measures, virtually all of today’s Republicans do their bidding despite what most Americans say they prefer.

As we have spelled out empirically, the Koch network possesses greater clout and a much stronger ideological backbone than most of the groups that ruled the GOP-conservative roost as recently as 2000; and the contemporary Koch operation has put in place a parallel federation that can discipline and leverage Republican politicians across multiple levels of government. When it comes to government’s role in the economy, however, the overall U.S. conservative agenda has only evolved, not changed. The Koch network brings new capabilities and ideological extremism to a long-running class war from above. Battling Democrats and liberals across all levels of government between as well as during elections, the Koch network, spearheaded by Americans for Prosperity, aims to complete the job started and furthered by Americans for Tax Reform, the Club for Growth, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. In some policy fights, the Koch network may flex its muscles against business allies. But for the most part, the network just strengthens the ability of right-wing corporate and ideological elites to steer American democracy away from the wants and needs of most citizens.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Budgets of Organizations in the U.S. Republican/Conservative Universe

Appendix B. Core Organizations in the Koch Political Network

Appendix C. Public Opinion, AFP Advocacy, and 2011 Retrenchment of Public Sector Union Bargaining Rights