INTRODUCTION

Men’s use of lethal force against intimate female partners, or femicide, is ubiquitous and has been widely reported in various mass media across the globe: e.g. “Delhi Man Kills Wife Over Suspicion of Affair” (NDTV 2021); “Pennsylvania Man Kills Wife Over Cheating” (New York Daily News 2021); “Japan Man Kills Wife, Son with Pickaxe” (Deccan Herald 2018). The issue has also been the focus of extensive research and analyses in books and scholarly journals (Aldridge and Browne Reference Aldridge and Browne2003; Browne, Williams, and Dutton Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999; Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988; Dobash and Dobash Reference Dobash and Dobash2015; Pichon et al. Reference Pichon, Sarah, Erin, Nambusi, Heidi and Ana2020; Websdale 2020). The profusion of literature on the topic has contributed substantially to current understandings of the phenomenon and programmatic efforts designed to curb this form of aggression (Campbell Reference Campbell2012). However, much of this literature has focused on femicide incidents in Western industrialized societies. Concurrently, there is a shortage of studies on the phenomenon in non-Western, non-industrialized cultures. Research on the topic from these geographically and culturally marginalized areas is needed to help expand empirical knowledge because only then can a full understanding of homicide in general and spousal homicide, in particular, be achieved.

BACKGROUND

Existing studies have identified male sexual jealousy as a major motivating factor in men’s lethal victimization of intimate female partners cross-culturally (Campbell Reference Campbell2012; Daly, Wilson, and Weghorst Reference Daly, Margo and Weghorst1982; Dobash and Dobash Reference Dobash and Dobash2012; Johnson Reference Johnson2012; Pichon et al. Reference Pichon, Sarah, Erin, Nambusi, Heidi and Ana2020; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Wilson and Daly Reference Wilson and Martin1998). In sexual jealousy homicides, the perpetrator accused the victim of infidelity (Block and Block Reference Block and Richard2012; Johnson Reference Johnson2012). Male sexual jealousy is such a recurrent social feature that it has been a longstanding focus of psychological, sociological, and criminological investigations (Block and Block Reference Block and Richard2012; Block and Rasche Reference Block and Christine2012; Browne et al. Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999; Campbell Reference Campbell2012; Pichon et al. Reference Pichon, Sarah, Erin, Nambusi, Heidi and Ana2020; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Taylor Reference Taylor2012; Zahn and McCall Reference Zahn, Patricia, Smith and A. Zahn1999). Despite the consistent finding that male sexual jealousy factors into femicide, the issue has not received sufficient attention in the lethal violence literature in many non-Western societies. Therefore, to help shed additional light on the subject and contribute to a fuller understanding of intimate-partner femicide, the current study was designed to provide a descriptive analysis of wife-homicide cases in Fiji stemming from the offender’s accusation that his partner had been sexually unfaithful to him. The veracity or falsity of the infidelity charge was positioned outside the scope of the present analysis. Rather, the focus was on the criminological aspects of the homicide, including: (1) sociodemographic characteristics of offenders and victims; (2) spatial and temporal aspects of the offense; (3) whether or not the offender and victim were co-residing at the time of the lethal incident; (4) method of offense perpetration, including weapon type and amount of force used; (5) post-offense suicidal behavior; and (6) dispositions.

Researching male sexual jealousy homicide in Fiji is important for at least two reasons. First, as noted, our knowledge of partner violence will expand. Second, understanding the determinants of male sexual homicide is important to identify and establish policies for preventing such tragedies. One distressing impact of male sexual jealousy homicides is the destruction of families. With the mother–victim deceased and the assailant–father incarcerated for life or a lengthy period, the surviving children must now contend with the long-term absence of both parents.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sexual jealousy refers to the “emotional response to a real or perceived threat of a partner’s sexual infidelity” (Davis, Vaillancourt, and Arnocky Reference Davis, Tracy and Steven2016). It has been the subject of a vast body of literature in the social and behavioral sciences (Daly et al. Reference Daly, Margo and Weghorst1982; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Tracy and Steven2016). Studies indicate that sexual jealousy is a major contributor to partner homicides by husbands against wives (Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988; Daly et al. Reference Daly, Margo and Weghorst1982; Campbell Reference Campbell2012; Dobash and Dobash Reference Dobash and Dobash2012; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Wilson and Daly Reference Wilson and Martin1996). In the United States and Canada, there have been plenty of criminological and other analyses to help explain how men’s sexual jealousy contributes to male aggression against female intimates (e.g. Aldridge and Browne Reference Aldridge and Browne2003; Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Websdale Reference Websdale2010; Wilson and Daly Reference Wilson, Martin, Radford and Russell1992, Reference Wilson and Martin1996). The concept of proprietary behavior or proprietariness has increasingly been adopted to describe the broader behavioral patterns stemming from males’ exclusivity and sense of entitlement towards their female partners. Proprietary men perceive their female partners as their personal property over whom they have monopolistic ownership rights. Any attempt by the female to assert autonomy in the relationship or unilaterally exit the relationship is met with fierce resistance (Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Wilson and Daly Reference Wilson and Martin1993).

Criminologists distinguish between two categories of criminal motivations – instrumental and expressive. In instrumental crimes, the offender is motivated to obtain material goods such as money, cars, and jewelry. Expressive crimes are motivated by rage, jealousy, revenge or hate (Miethe, Regoeczi, and Drass Reference Miethe, Regoeczi and Drass2004). Jealousy-driven spousal homicides are expressive crimes. Expressive crimes are typically more heinous or aggravated than instrumental ones (Browne et al. Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999; Miethe et al. Reference Miethe, Regoeczi and Drass2004). Several lethal violence studies have found a pattern of overkill to be a common feature of intimate partner homicides (Browne et al. Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999). Overkill refers to the application of aggression deemed much more than is needed to accomplish a crime. Overkill has been operationalized to evince “two or more acts of stabbing, cutting, shooting, or a severe beating” (Browne et al. Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999).

Previous research into men’s homicide perpetration against intimate partners has also found victimization high for women seeking separation or divorce from husbands and other non-marital partners because the men could not accept rejection by or separation from the departing partner. Also, perpetrators could not take the woman being with another man (Alvarez and Bachman Reference Alvarez and Ronet2003; Browne et al. Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999; Menzies Reference Menzies2005; Serran and Firestone Reference Serran and Philip2004; Wilson and Daly Reference Wilson and Martin1993; Wilson, Daly, and Wright Reference Wilson, Martin and Wright1993). As Gauthier and Bankston (Reference Gauthier and William2004) put it, “men often pursue, stalk, and kill spouses that have left them.” In these cases, wife killers are driven by the philosophy “If I can’t have her, then no-one can.” (Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988:197)

Gerontogamy is a marital relationship characterized by substantial age disparity between the couples. The partner violence literature suggests that such marriages tend to be volatile, exhibiting higher levels of partner violence. Some homicide research (Daly and Wilson Reference Daly and Margo1988; Mercy and Saltzman Reference Mercy and Saltzman1989; Shackelford Reference Shackelford2001b) suggests that in those relationships where there is considerable age differential between the couple, the parties are at greater risk of being slain by their intimate partners than are persons in conjugal unions where such age differential is minimal or non-existent. Wilson and Daly (Reference Wilson, Martin, Radford and Russell1992:200) noted from their analysis of Canadian data that “spousal homicide rates increased as the couple’s age disparity increased. This was true for both wives and husbands, regardless of who was the older party.” Similar findings were described by Mercy and Saltzman (Reference Mercy and Saltzman1989:596) in their examination of spousal homicide data in the United States. They asserted that “among couples where the husband was two or more years younger than the wife, the spouse homicide rate was 5.0 per 100,000 compared with 2.6 among couples whose ages were within one year of each other and 3.6 among those couples where the wife was two or more years younger than the husband.”

Homicide scholars have observed that cohabitating couples or persons living in common-law or de facto relationships have an elevated risk for lethal violence victimization by their partners compared with couples living in registered unions. Based on their analysis of aggregated Canadian homicide data spanning the period from 1974 to 1990, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Martin and Wright1993) observed that the rate of spousal homicide victimization for women in common-law marriages was 8.4 times higher than that for women in registered marriages, while the corresponding ratio for men was 15.0. In the United States, Shackelford (Reference Shackelford2001a,b) estimated that cohabiting women were killed at a rate 8.9 times greater than legally married women in 1976–1994, while the equivalent ratio for men was 10.4. For Australia in the 1990s, these ratios were estimated to be 9.6 for women (Shackelford and Mouzos Reference Shackelford and Jenny2005) and 16.2 for men (Mouzos and Shackelford Reference Mouzos and T. K.2004). Although these countries differed considerably in their overall homicide rates, the remarkable divergence between conjugal and cohabiting couples was astonishingly consistent. However, in a later study, James and Daly (Reference James and Martin2012) reported that by 2005, the elevated homicide risk previously reported among cohabiting couples in the United States was no longer evident.

Some research has reported a link between pregnancy and women’s risk for male-perpetrated intimate partner femicide (McFarlane et al. Reference McFarlane, Campbell, Phyllis and Kathy2002; Taylor Reference Taylor2012). In a study focalizing the issue in the United States, McFarlane et al. (Reference McFarlane, Campbell, Phyllis and Kathy2002:27) compared a group of women who were not abused during pregnancy with those who were attempted/completed femicide victims abused during pregnancy. They found that “after adjusting for significant demographic factors, such as age, ethnicity, education, and relationship status, the risk of becoming an attempted/completed femicide victim was three-fold higher for women abused during pregnancy.”

From the sociological perspective, people are strongly influenced by the culture in which they were socialized. Thus, sociological criminologists consistently examine the social and cultural forces underlying sexual jealousy femicides. One of the most persistent characterizations of male-perpetrated femicides is the worst form of gender-based violence integral to patriarchal societies (Hunnicutt Reference Hunnicutt2009; Schmuhl Reference Schmuhl2017; Taylor and Jasinski Reference Taylor and Jasinski.2011). This observation has spawned a great deal of literature that examines patriarchy’s impact on female homicide victimization. It is averred that men in those societies want to exert full control over their mates, including their physical mobility and reproductive decision-making. Marital infidelity by the female partner is seen as an egregious violation of one of the most critical tenets of patriarchy – male sexual exclusivity over the female partner.

FIJI: THE RESEARCH SETTING

Located in the South Pacific, Fiji is an archipelago of 330 islands. Of the population, 75% lives on the island of Viti Levu and 12% on the second-largest island, Vanua Levu. In 2021, the country’s total population was estimated to be 901,437. Fiji’s population is racially, ethnically, linguistically, and religiously heterogeneous. In 2021, 56.8% of the population was indigenous Fijian (or Itaukei), and 37.5% was Indo-Fijian (descendants of indentured laborers who arrived from India between 1879 and 1915). The percentage representation of other groups (European, part-European, Chinese, and other Pacific Islanders) was 4.5%. The Itaukei are predominantly Christian, while the Indo-Fijians are largely Hindu and Muslim. In 2019, 49.3% of Fiji’s population was female and 50.7% male. In 2014, life expectancy for females was estimated at 68.5 years and 65.4 years for males. The official literacy rate for 2017 was 99.08%. In 2019, it was estimated that 57% of the population resided in urban areas. The people of Fiji are predominantly agricultural, with cane farming constituting a major cash crop. Tourism represents a key economic contributor to foreign exchange earnings. Currently, unemployment is a major social issue. The suicide rate per 100,000 population is also high, particularly among the Indo-Fijian population (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2003). Youth abuse of alcohol and marijuana is also high, particularly among Itaukei (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah1995, Reference Adinkrah1996).

The two dominant ethnic groups – Itaukei and Indo-Fijian – are patrilineal, patriarchal, and patrilocal in family structure and dynamics. However, particularly in the urban areas, patrilocality breaks down, and increasingly neolocal residential patterns are observed. The typical family unit in society consists of a male head and a subordinate wife and children. Gender roles are strong and strictly enforced. Although attitudes and behaviors may be transforming, men’s use of aggression against female partners in intimate relationships has been widely reported and denounced. In September 2020, Fiji’s Cabinet Minister for Women and Children made the following observation regarding the scope of domestic violence in the society: “As a society, 72% of all Fijian women have faced some form of violence in their lifetime, and 64% of women who have been in intimate relationships have experienced physical or sexual violence from their partner, including 61% who were physically attacked and 34% who were sexually abused” (Commonwealth Parliamentary Association UK 2020; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2020). The extreme assaults against female intimates have been attributed to patriarchal attitudes and practices that subjugate women to the male partner’s wishes (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah1999a,b, Reference Adinkrah2001). Errant men use verbal threats or physical coercion to keep partners compliant, subservient, or quiescent (Kumar Reference Kumar2020a). Marital and dating relationships plagued by abuse occasionally lead to separations or divorce.

Fiji has stringent firearm laws. Even law enforcement officers on patrol do not routinely carry firearms. Although accessibility to guns is restricted, potentially lethal implements such as machetes and knives are widely available in such an agrarian society. Police data show that 18 to 25 incidents of homicide occur in the country per year. The following homicide rates per 100,000 population are for the country from 2010 to 2016: 2.65 (2012), 2.19 (2013), 2.30 (2014), 2.99 (2015), and 1.71 (2016). Like most countries, males are overwhelmingly the perpetrators of homicide (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah1996, Reference Adinkrah2000). Motives offered by men for the slaying of intimate partners include real or imagined infidelity and the threat of relationship termination. When women kill, it is likely to be infanticide or neonaticide (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah1996, Reference Adinkrah2000).

RESEARCH METHODS AND DATA SOURCES

Currently, there is no national registry of homicide cases in Fiji. Therefore, for this research, media surveillance methodology was utilized to identify male sexual jealousy homicides in the country from 2010 to 2020. Extensive, meticulous searches were conducted of the various electronic media operating in the country using a combination of keywords and phrases such as “wife killer,” “kills wife,” “spouse infidelity/affair,” and “life sentence for murder.” Sources searched were Fijitimes.com, Fijisun.com, Fijivillage.com, Fbcnews.com, and Fijilive.com. To ensure complete and accurate information, identified cases were explored through each of the websites mentioned above. Homicide is a particularly newsworthy crime in Fiji, and incidents are covered extensively in the various print and electronic news outlets. Journalists from different media houses attend court sessions relating to a homicide episode and cover the proceedings in their entirety.

Additionally, crime news reporters vigorously pursue police investigators for information relating to the crime. Remarkably, information on homicides is published promptly, from the time of occurrence, through arrest, arraignment, trial, conviction, and sentencing. It is not uncommon for a judge to summon a news reporter to the courtroom to respond to queries about erroneous reporting (Narayan and Deo Reference Narayan and Dhanjay2018). Such assiduous pursuit of information in a homicide case ostensibly culminates in publishing factual and reliable information.

Once a sexual jealousy homicide was identified, the defendant’s name was used to locate judicial records from the Fiji government’s judiciary website (judiciary.gov.fj). Documents accessed included “Summing Up,” “Judgement,” and “Sentence.” In cases where the defendant filed for appellate review of the case, the decision of the Appeals Court was accessed. In all, some 4,190 pages of print documents were analyzed. Information obtained from the sources was aggregated to provide an accurate profile of the offense, offenders, and victims.

Information obtained from judicial documents and media reports included: (1) names of offenders and victims; (2) spatial aspects of the crime, including the name of the village, town or city and province where the offense occurred; (3) physical location of the crime, such as a bedroom or kitchen; (4) temporal aspects of the crime such as date and time of occurrence; (5) method of offense perpetration and weapon involved; (6) victim–perpetrator relationship; and (7) motivation of the offense. Judicial records routinely provided detailed information about the victims and defendants (e.g. age, occupation, marital status, number of children, length of marriage or period in a de facto relationship) and the spatial and temporal aspects of the crime. Despite the availability of personal names of people and places, I decided to exclude them from the current publication.

RESULTS

The study identified 25 homicide cases and five attempted homicide cases where the dominant motivation was male sexual jealousy. One case was a familicide in which the assailant slew his spouse and two dependent children (Wilson, Daly, and Daniele Reference Wilson, Martin and Antonietta1995). Fifteen (50.0%) cases involved Itaukei Fijians, 14 (46.7%) involved Indo-Fijians, one case (3.3%) involved an expatriate couple residing in Fiji. Given the tendency toward ethnic and racial endogamy in Fiji, victims and perpetrators share the same racial or ethnic identity.

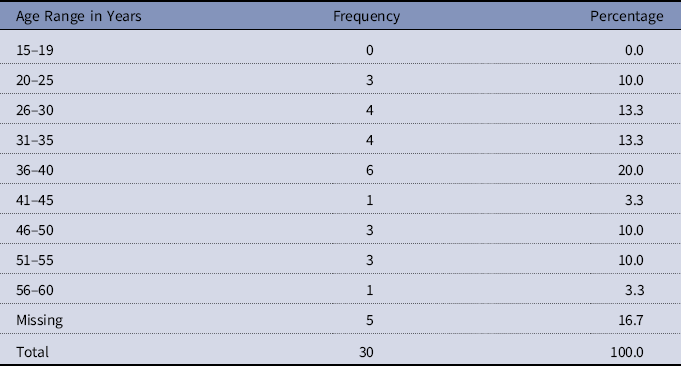

Offenders ranged in age from 21 to 56 years old, with a mean age of 38.1 years, median age of 38 years, and a standard deviation of 10.6 (see Table 1). Victims ranged from 16 to 47 years old, with a mean age of 29.2 years, median age of 27.5 years and a standard deviation of 8 (see Table 2). The male offender was younger than the victim in only two cases, one case by one year and the other by five years.

Table 1. Age of Offenders

Table 2. Age of Victims

The age disparity between offenders and victims ranged from 0 to 32 years. The mean age difference was 7.9 years, the median was 5.0 years, and the standard deviation was 7.4. In Case 3, there was a 32-year age difference; in Case 29, there was a 21-year age difference; in Case 26, there was a 19-year age difference; and in Case 20, there was a 17-year age disparity. The data showed that two (6.7%) of the victims were pregnant at the time of the incident. In Case 3, the victim was three months pregnant; in Case 6, the victim was four months pregnant. The defendant in Case 6 stated in his cautioned statement to police that he knew that the victim was pregnant; he nonetheless stabbed her twice in the stomach with a kitchen knife before proceeding to slash her multiple times with a machete.

Of the victims, 17 (56.7%) were legally married to their attackers; 11 (36.7%) lived in common-law relationships. One couple was recently divorced, and one was unmarried dating partners living with their respective natal families. Eight (26.7%) of the victims were estranged from their assailants at the time of the lethal incident. The study examined offender–victim relationships in deadly and non-deadly encounters. In 24 (95%) of the 25 murder cases, the assailant killed the presumed errant wife who was the primary target of his wrath; in the remaining case, the assailant killed his wife’s paramour who was present during the assault before inflicting grievous non-lethal injuries on his wife and her aunt.

The assailants’ criminal history was consistently reported in judicial records, highlighted during sentencing as mitigating or aggravating factors. Five (16.7%) assailants had prior criminal convictions. The assailant in Case 6 had accumulated 34 previous criminal convictions, although details about the nature of the crimes were not provided. The assailant in Case 18 had six prior convictions, four of which were for aggravated assault. The assailant in Case 3 had two convictions of absconding bail and one record of aggravated assault. For the assailant in Case 9, it was mentioned that his marital difficulties with his wife escalated following his release from prison; it was, however, not noted what crime contributed to his incarceration. The assailant in Case 11 had eight previous convictions, including larceny and aggravated assault.

Information on the occupational status of offenders was not consistently provided in either media or court records. It showed that offenders and victims were from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds. Five (20%) offenders were described as peasant farmers. One offender was a taxi driver; another was a driver for a government agency. Two assailants were described as businessmen; one owned a construction firm that employed 26 people; the other was engaged in a small-scale business. One assailant was a retired military officer owner of a security and logistics firm. Information on victims was particularly sparse. Victims identified by occupation were described as police officers, receptionists, nurses, janitors, nannies, and homemakers.

Offense Characteristics

Regarding the homicide setting, in 16 (53.3%) cases, the victim was attacked in the couple’s shared residence; six (20.0%) occurred in public places (e.g. bus stop, public street); another five (16.7%) victims were attacked in their own homes; two incidents (6.7%) occurred in the offender’s home and one (3.3%) at the offender’s workplace.

The study examined the modus operandi and weapons used in the incidents. In 14 (46.7%) cases, the assailant used a knife, typically a kitchen knife, to stab the victim; in five (16.7%) cases, the assailant used a machete (cane knife) or cleaver knife (chopper) to slash the victims. Other methods of offense perpetration include beating with personal weapons (hands, feet, etc.) (three or 10.0%), manual strangulation (three or 10%), ligature strangulation (with a scarf, computer cord) (two or 6.7%), bludgeoning with a blunt object (one or 3.3%) and burning (one or 3.3%). In some instances, the assailant used a combination of methods. One assailant beat the victim with hands, feet, fists, a small tree branch, and an electrical cord. One offender bludgeoned the victim with an iron rod before strangling her to death with a computer cord. One other assailant beat the victim with his hands, although the victim died from paraquat poisoning. In court, there was a dispute over whether she ingested the substance voluntarily or was coerced by the assailant into consuming it. One assailant smeared a highly flammable chemical on the victim’s clothes before setting her aflame (see Table 3).

Table 3. Method of Offense Perpetration

Judging by the mode of killing, the extent of violence, and the scope of injuries sustained by the victims, all 30 cases demonstrated features of overkill. To illustrate, in Case 1, the assailant used a kitchen knife to “stab the victim once on the top right of the chest and four times on the left part of her back.” In Case 2, the assailant “stabbed the victim twice on the chest, [then] he stabbed her back. When she could not resist, he held her head back and slit her throat with the knife.” Case 4 was a multicide in which the assailant used a cleaver knife to slash the throats of his wife and two minor children. In Case 6, the assailant used a machete and kitchen knife to inflict 20 deep wounds on the victim. In Case 13, the assailant stabbed the victim 16 times with a pig-hunting knife; in Case 17, the assailant stabbed the victim eight to nine times with a kitchen knife; in Case 20, the victim was stabbed eight times with a kitchen knife. Case 14 makes for difficult reading:

The offender sneaked from behind and struck her on the head with the cane knife he had brought from his home. She sustained injuries to her hand and head. [The victim’s] mother rushed to her daughter’s rescue, but the offender pushed her away. Her mother pleaded with the offender to spare her daughter from harm. The offender did not listen. The attack on [the victim] was in the presence of her two-year-old daughter. Despite being seriously injured, [the victim] ran inside for safety. But the offender pursued her inside the house and repeatedly struck her in the neck and head with the cane knife … The victim died at the scene. She sustained multiple slash wounds to her head, neck, left upper limb and posterior trunk. Her skull and facial bones were exposed due to the slash wounds, and her neck was almost severed (Kumar Reference Kumar2020a).

Of the 30 cases, 16 (53.3%) exhibited clear and ubiquitous evidence of premeditation rather than spontaneous, spur-of-the-moment episodes. In Case 3, the offender hunted down and located his estranged partner. He took two knives there, having already plotted to kill her and her new partner. He pleaded for her return; when she declined, he butchered her with both blades. In Case 8, the assailant and victim were separated but shared custody of their three children. On the day he was to exchange physical custody of a child, he carried a bottle of a highly flammable substance and gaslighter. During that brief interaction with the victim, he rubbed the substance on her clothes and then set her ablaze. In Case 5, the assailant prepared beforehand to kill his estranged wife after she told him on the telephone that she was having sex with her new lover. He walked three kilometers to reach her location. Along the journey, he stopped at a house to ask for a machete from an occupant. Upon arrival, he butchered the man before inflicting grievous injuries on his wife. In Case 2, after the assailant confirmed rumors that his wife’s infidelity had not ceased, he meticulously whetted a kitchen knife and waited for her arrival from work. Following dinner, he stabbed her multiple times before slitting her throat. Satisfied that she was deceased, he cleaned the knife and walked to the police station to surrender himself. In Case 9, the assailant pre-planned the victim’s murder. He spent one week sharpening the kitchen knife he employed in the stabbing. In Case 10, after the husband heard a rumor that his wife was having extramarital affairs, he plotted her murder without attempting to authenticate the allegation. He drove to the victim’s workplace under the pretense of calling for her assistance in helping their child, who he claimed was hurt in an accident. He beat her into a comatose state; she died a few weeks later.

Lengthy and excessive alcohol consumption featured in six (20%) incidents. In these cases, the homicide occurred after the offender or victim alone or with others had been drinking massive quantities of the beverage. Four (13.3%) assailants attempted suicide following the assault on the victim. In court, three proffered their suicide attempt as evidence of their diminished mental capacity and sought reductions of their charges from murder to manslaughter. All three requests failed.

Of the defendants, 16 (53.3%) cited provocation due to a partner’s infidelity as the reason for committing the offense. In Case 1, the defense team submitted that the defendant had no case to answer “because he was provoked into committing the homicide.” The defendant in Case 4 contended that he was provoked to kill “after learning that his wife whom he loved so much had not once, but twice cheated on him with two different men.” He averred that “this caused him to lose control of his mind in the situation.” The defendant in Case 5 said he killed the victim because “he was heartbroken” by her adultery. He said his wife had three previous extramarital affairs with other men. He claimed he reached boiling point when his wife caused him to listen to her having sex with her lover over a phone speaker. In Case 6, “the assailant told the court that he was a victim of deceit, betrayal and distrust by the deceased” and that he “acted on the spur of the moment.” The “incessant rage with which he hacked the deceased was caused by the compromising position in which he found the victim with an unknown man in his bedroom, under his roof.” The defendant in Case 13 said that “he acted in the provocation of rumors of an affair his wife was having.” In Case 17, the defendant submitted to the court that three aspects of the victim’s behavior were particularly provocative. First, she showed him “love bite marks on her neck,” marks she supposedly acquired during physical intimacy with her new consort; second, the victim showed him items of clothing and jewelry that her new lover had purchased for her and said she was happier with him than the assailant; third, rumors were circulating in the community that his estranged wife was having sex with multiple men in the community. The assailant in Case 18 said he was provoked by rumors circulating unceremoniously and when the victim returned the next day with love bite marks on her neck. In Case 19, the defendant accused the victim of “two-timing” him. Thus, he “wanted to pay her back for what she did to him.” One defendant claimed self-defense, saying he was only preempting the wife’s bid to kill him. Another defendant advanced post-traumatic stress disorder as defense, submitting that he had witnessed and participated in numerous occasions of violence during his military service overseas, which negatively impacted his psyche. On the day of the incident, he perceived his allegedly errant wife as an “enemy.”

In Fiji, the conviction for murder or attempted murder carries a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment. Section 237 of the Fiji Crimes Decree (2009) grants sentencing judges the discretion to set minimum terms to be served before pardon may be considered. In each case analyzed, the assailant was convicted of murder or attempted murder and sentenced accordingly. In exercising judicial discretion to set minimum eligibility terms for executive clemency, assailants were ordered to serve minimum terms ranging from eight to 24 years.

Cases profiled in the present article garnered immense public attention, eliciting a strong negative reaction from the public, many of whom saw the offenders as morally reprehensible and needing to be incapacitated for the good of society. The funerals of victims often became public events. The media occasionally published interviews with secondary victims who typically expressed anguish and hostility when the offense occurred and a modicum of relief following the assailant’s conviction and sentencing (e.g. Naidu and Labasa Reference Naidu and Selita2018; Satakala Reference Satakala2016). In judicial pronouncements made during sentencing, judges routinely fulminated over male violence against women, chastising defendants about the foolishness of using homicide as a means to resolve marital disputes. Men were importuned to accept female partners’ autonomy to make decisions about their sexuality and relationships (e.g. Kumar Reference Kumar2020a,c).

CASE SUMMARIES

Case 1

In this case, a 34-year-old farmer fatally stabbed his 28-year-old wife, with whom he had two children aged 11 and nine years old. At the time of the murder, he served as the headman of his village. In his cautioned statement to police, he accused his wife of carrying on an extramarital relationship with another man for the three years preceding the lethal incident. The assailant testified that he knew the identity of the man. He said he warned her to terminate the extramarital relationship, yet it persisted. He claimed that in the days preceding the lethal assault, he discovered that the victim had been exchanging text messages with the man. He also found a recording of the same lover speaking to the victim on her phone and got angry. On the day of the murder, he struck the victim in the mouth, grabbed a kitchen knife, pulled her into the bedroom, and stabbed her to death. The case had elements of overkill. The victim was stabbed multiple times: once in the right chest and four times in the back. The assailant stated in court that he intended to kill the victim. The pathologist testified that the victim’s chance of survival from the assault was 2%. In court, defense counsel submitted that the offender was guilty of manslaughter, not murder, due to provocation stemming from the victim’s prolonged sexual infidelity. The assailant was found guilty of murder and sentenced to the mandatory life sentence to serve 18 years before qualifying for executive clemency (Prakash Reference Prakash2021; Tadulala Reference Tadulala2021; Criminal Case No. HAC 140 of 2020S).

Case 2

In this case, a 54-year-old man lethally assaulted his 47-year-old wife over allegations of adultery. The couple had five children together, and they were also grandparents. The assailant and the victim were described as a farmer and janitor, respectively. The incident occurred at the couple’s shared residence. According to the facts of the case, the couple and their children previously resided together on one of the smaller islands in Fiji for several years. The victim later moved to Suva, the national capital, to supervise their children’s education on another island. The assailant remained in the village, continuing his work as a farmer. He sent remittances of $300–400 weekly to the wife and children. The assailant heard rumors about the victim’s sexual infidelity while he was visiting the family in Suva. He queried the victim about the affairs; she admitted that they were true and pledged to cease. The assailant visited again nine months later. On the day of the femicide, the victim went to work. While at home, the assailant again heard rumors that his wife’s infidelity had not ceased. When the victim returned home from work, the couple prepared dinner together, ate, and then retired to bed. The victim refused to have coitus with the assailant. Enraged, he went to the kitchen and grabbed the kitchen knife that he had sharpened earlier in the day. He repeatedly stabbed her with it; he slit her throat, causing her to bleed to death. The assailant then walked to the police station and turned himself in. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was to qualify for presidential pardon only after 20 years of serving the sentence (Kumar Reference Kumar2020b; Criminal Case No. HAC 031 of 2020).

Case 3

In this case, a 55-year-old man murdered his 23-year-old partner with whom he shared a de facto relationship. The man was a retired army officer who had participated in eight tours of duty overseas with the country’s military. He had also worked for 17 years as a private security officer for overseas contractors. The victim previously worked as an usher at a movie theater. At the time of the murder, she was working as a nanny. The victim, the niece of the assailant’s legal wife, had started residing with the marital couple at 18 years old. The victim and the assailant soon became involved in a sexual relationship that produced a child. The assailant separated from his legal wife and established a new abode with the victim.

While working at a night job, the victim met and established a sexual relationship with another man. According to the assailant, the victim started coming home late from work. When he asked her about her tardiness, she claimed that she was working extra hours. The assailant said he observed love bite marks on the victim’s neck and breasts. He confronted her over his suspicions. The victim admitted to having a sexual relationship with another man. The victim later told him that she was pregnant with the man’s baby. When the victim moved out of the assailant’s home, he became jealous and angry and went on a mission to find her. When he located her new place of employment, he carried two kitchen knives with him that he intended to use as murder weapons. When he arrived, he pleaded with her to return to him. She refused. In response, he stabbed her 12 times, leaving only after he was convinced that she was deceased. The assailant was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life with a non-parole period of 18 years (Deo and Danford Reference Deo and Iva2018; Lacanivalu Reference Lacanivalu2018; Criminal Case No. HAC 099 of 2017S).

Case 4

In this triple-homicide incident, a 33-year-old man killed his 29-year-old wife and their two daughters, aged five years old and seven years old, hacking the victims to death with a cleaver knife while they slept. Following the homicides, he made an abortive suicide attempt. On the day of the murders, the assailant accused his wife of having an extramarital affair with his landlord’s 14-year-old son. He further claimed in court that the victim had also admitted to having a sexual relationship with the landlord, who had blackmailed her with a threat to expose her affair with the 14-year-old boy. The assailant testified that he suffered from diminished mental capacity stemming from his wife’s provocative behavior. He was convicted of three counts of murder and sentenced to three concurrent life sentences. The court ordered that he serve a minimum 20-year sentence before parole consideration (Hill Post Wire 2013; Narayan Reference Narayan2013; Criminal Case No. HAC 364 of 2011).

Case 5

In this case, a 33-year-old man was sentenced to prison for life following convictions for the following crimes: (1) attempted murder of his 28-year-old wife, (2) murder of his wife’s paramour, and (3) attempted murder of his wife’s aunt. At the time of the incident, the couple had been married for four years without a child. The assailant admitted committing the offenses but contended in his cautioned statement that his cuckoldry had provoked him. The couple had separated for two weeks; the victim temporarily stayed with her aunt a few miles away. On the day of the murder, the assailant called his wife at 11 p.m. to inquire when she intended to return to their home. The victim rebuked him for contacting her late at night and hung up the phone. When the assailant called back, the wife told him she was having sexual intercourse with her new-found lover. She tauntingly put the telephone on a loudspeaker mode so the assailant could hear her “moans and groans” from their intercourse. The assailant called back. This time, a man picked up the phone and asked the husband not to call again as he was having sex with the man’s wife. The assailant said he decided at that moment to go and “teach her a lesson.” It was midnight. Toting a machete, he walked three kilometers by foot in the dark to the location where the wife was lodging. When he arrived, he butchered the wife’s paramour and grievously injured his wife and her aunt. The assailant was convicted of all three crimes and was sentenced to prison for life with a proviso that he serve a minimum of 19 years before qualifying for parole (Stolz Reference Stolz2015; Criminal Case No. HAC 081 of 2014S).

Case 6

In this case, a 40-year-old man slew his 32-year-old cohabiting partner over an allegation that she was having a sexual relationship with another man. He then attempted to commit suicide by hanging himself with an electrical cord. The couple had been in a relationship for barely four months at the slaying, and the victim was pregnant. The assailant claimed in court that he returned home one afternoon to find a partly nude man jumping out of a door in his home. He stated that he committed the offense following a heated altercation with the victim regarding the man’s identity. Using a kitchen knife and a machete, he stabbed the victim 20 times. In court, he proffered a defense of provocation stemming from the sexual infidelity of a spouse. The evidence in court revealed that the victim was a married woman when she met the assailant at a drinking party. She left her husband and moved in with the assailant. She became pregnant shortly after that and stayed. The victim’s legal husband told the court that at the time of the murder, he and the victim had begun reconciliation to re-establish their marital bond and that he had gone to the victim’s place to help her remove her belongings. The assailant was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life. Sentencing records show that he had 34 previous criminal convictions and attempted suicide twice since the femicide. The judge stipulated that he serve a minimum of 16 years before qualifying for executive clemency (Cava Reference Cava2018; Sauvakacolo Reference Sauvakacolo2010; Talei Reference Talei2018b; Criminal Case No. HAC 47 of 2010).

Case 7

In this case, a 56-year-old taxi driver was convicted of murdering his 47-year-old estranged wife. The couple had been married for 27 years and had three adult children. According to the facts of the case, the wife initiated a separation over incessant arguments and conflicts between the couple, obtaining a domestic violence restraining order against the assailant. At the time of the murder, the couple had been separated for three years. The husband alleged that the wife was involved in sexual relations with other men during their separation and was incensed by that. The incident occurred at the assailant’s mother’s home, where the victim had gone to pay her mother-in-law and sister-in-law a visit. While there, the assailant showed up to visit his mother. He took advantage of the victim’s presence to murder her. He took a kitchen knife from the kitchen and stabbed her to death. He was sentenced to prison for life, with an order that he spend a minimum of 18 years to be eligible for presidential pardon (Talei Reference Talei2017a,b; Criminal Case No. HAC 163 of 2014LTK).

Case 8

In this case, a 37-year-old man was convicted of killing his 25-year-old estranged wife over suspicion that she was having an extramarital affair with a police officer. The couple had been married for nine years and had three children aged eight, four, and one-and-a-half years. For the two years preceding the homicidal assault, the couple had separated and lived in different residences. The wife maintained physical custody of their two daughters while he had custody of their son. On the day of the homicide, the husband arrived at the shop where he and the victim had arranged to meet momentarily to exchange custody of one of the children physically. The assailant arrived at the meeting with a gaslighter and a previously purchased paint-thinner, described as highly flammable. During their brief interaction at the shop, he rubbed some chemicals on the wife’s clothes and hair. He then set her aflame with the lighter. The victim sustained burns on 35% of her body and died at a hospital 10 days later. The defendant told the court that his wife’s extramarital affairs had burdened him so much that he had developed hypertension. He attributed his crime to the stresses and strains of his wife’s infidelity. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. The judge ordered that he serve a minimum of 18 years before a parole application could be considered (Talei Reference Talei2018a,c; Lautoka Criminal Case No. HAC 091 of 2015L).

Case 9

In this case, a 44-year-old man was convicted of murder in the homicide of his 33-year-old wife and was sentenced to life imprisonment. The judge ordered that he not be granted parole until he had spent 20 years in prison. The couple had been married for 17 years and had four children together. The couple’s marital problems began when the assailant returned from prison for an undisclosed crime. Upon release, he sought reunification with the victim but was allegedly rebuffed by her. He had also heard rumors that the victim was having extramarital affairs. On the day of the murder, the assailant visited the victim’s home, drank kava, and socialized with some of her relatives. The couple argued throughout the night. The following morning, he asked the victim to accompany him to the bus stop to catch a bus. The assailant pulled out a kitchen knife and stabbed her repeatedly on a river bridge along the way. The pathologist reported that “the victim died of shock, excessive loss of blood and the severing of an artery on the right shoulder close to the neck because of repeated stabbing.” During sentencing, the judge remarked that the crime was calculated and that the assailant was unremorseful (Naleba Reference Naleba2014; Criminal Case No. HAC 052 of 2013S).

Case 10

In this case, a 29-year-old man killed his 27-year-old wife when he acted on a rumor that she was having sexual relations outside their marriage. The assailant was a businessman who owned a construction company employing 26 people. On the day of the incident, he heard that his wife was sexually involved with another man. Without authenticating the allegation, he left for his wife’s workplace. He lied to her that their son, who lived about a three-hour drive away, had been involved in an accident and that they needed to go and see him. The victim left work and accompanied him home. There, the assailant subjected her to a brutal ordeal in which he demanded that she acknowledge and substantiate the allegation of an extramarital affair. He beat her with a tree branch and an electrical cord “several times on her face and mouth until she fell sideways and hit her head on the floor.” He then left her in a comatose state. The victim died a few weeks later “from severe head injuries, which caused a stroke on the left side of her brain.” The judge’s sentencing remarks underlined the brutality of the homicide: “The unprovoked attack on the defenseless victim was gruesome, callous, and heartless. You left her lying in an unconscious state; the assaults were so intense that your immediate neighbor was uncomfortable and afraid when she heard the screams of the deceased” (Kumar Reference Kumar2020c; Vula Reference Vula2020; Criminal Case No. HAC 212 of 2016).

Case 11

In this case, the assailant was the 49-year-old legal husband of the victim. At the time of the incident, he was employed as a driver for the civil service. The conflict which resulted in the wife’s murder started when the husband returned home from work one evening and claimed to have seen a purported love bite mark on the victim’s neck. He concluded that his wife was having an affair with another man. His young daughter inspected the supposed mark and said it was “only a rash.” The husband was still convinced that it was evidence of a sexual affair she was having with another man. This caused a misunderstanding between the couple in the presence of their 12-year-old daughter. The dispute flared up again when the couple retired to bed that night. The assailant strangled the wife to death. He then tied a wire rope around the victim’s neck and attempted to hang her from the ceiling rafters of a room in the house to make it look like a suicide via hanging. He gave up after two attempts. Upon arrest, he confessed to the police that he had killed the victim. He pleaded for a reduced sentence based on provocation due to wifely infidelity (Fiji Times 2005; Criminal Case No. HAC 0038 of 2004).

Case 12

In this case, a 38-year-old ex-pilot killed his 34-year-old cohabiting partner over sexual jealousy. Incidents and events that occurred during their two-month relationship portrayed a man obsessed with the victim and fearful that he would lose her to another man or that she would desert him and return to her estranged husband. The assailant was also jealous because the victim often received telephone calls from someone called “William.” During an altercation with the victim over jealousy, he killed her when he “struck her head with [an] iron rod, kicked her on the left side of her face, pressed her neck with [his] right leg, and then strangled her to death with an electrical cord.” While on pretrial bail, the defendant absconded to India but was deported to Fiji six years later. While in India, he married and fathered a three-year-old daughter with a local woman. During sentencing, the judge expressed disquiet at the overkill and the use of the offensive weapon (iron rod) in the crime. The assailant was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. The judge stated that he should serve a minimum of 18 years before becoming eligible for executive clemency (Krishna Reference Krishna2018; Criminal Case No. HAC 018 of 2017).

Case 13

A 39-year-old farmer was convicted of wife murder and sentenced to prison for life, with the proviso that he serve 16 years in prison before qualifying for parole. The slaying was precipitated by the assailant’s accusation that the victim was having sexual intimacy with another man in their village. The couple had four children, aged 17, 15, 12, and 11 years old. At the time of the murder, the 17-year-old was away in a boarding school. The remaining three children witnessed their father killing their mother. According to judicial records, the assailant continually consumed liquor during the 24 hours preceding the murder. That day, his wife attended a celebration in the village with the children. When she returned home, an altercation broke out between her and the assailant. The victim hid in the bedroom and locked herself behind it. The assailant grabbed his “pig hunting knife,” broke down the door and stabbed her 16 times. Court records revealed “he slashed her face near the eye and stabbed her chest, rupturing her lungs. He stabbed her stomach and heels.” A postmortem examination report indicated that the victim died from “excessive loss of blood caused by multiple stabs and slash wounds.” The assailant confessed to the crime, stating that he “acted in the provocation of rumors of an affair his wife was having.” He was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life (Bolanavanua Reference Bolanavanua2019; Criminal Case No. HAC 046 of 2018).

Case 14

The assailant and the victim were 40 and 34 years old, respectively. At the time of the homicide, they had been married for 18 years and had three young children. In both his cautioned statement to police and allocution speech, the assailant accused the victim of being sexually promiscuous and of using separation from him as a pretense to terminate their relationship so she could establish a new intimate relationship with another man. About two months before the homicide incident, a dispute had arisen between the two and the victim left for her natal home. She took the youngest child, a two-year-old daughter, with her. The assailant made repeated pleas for reconciliation. The victim rejected all efforts. On the day of the murder, the assailant took a bus to the victim’s home while bearing a sack containing a machete. It was dark outside. After locating the house’s main electric switch, he switched off power and called out his estranged wife. He attacked her with the machete when she came out, striking her repeatedly and killing her instantly. The victim’s father told crime journalists that his daughter was “chopped up like meat.” The assailant was sentenced to prison for life with a condition to serve a minimum of 24 years to be eligible for parole (Kumar Reference Kumar2020a; Criminal Case No. HAC 46 of 2019).

Case 15

In this case, a 22-year-old stay-at-home father was convicted for murdering his 22-year-old nursing student wife. The couple had a four-year-old son. A year before the killing incident, the assailant had battered the victim over an undetermined matter, after which the victim moved away and obtained a domestic violence restraining order against the assailant. On the day of the incident, the assailant picked up the victim from a bus stop in a taxi, and the two went to a location to confer. When the victim wanted to leave to attend lectures at her school, the assailant prevented her from leaving and lethally stabbed her in the neck and abdomen with a knife he had brought with him. The victim died shortly upon admission to the local hospital. He pled guilty to the charge of murder and was sentenced to prison for life, to serve a minimum of 18 years before parole eligibility (Susu Reference Susu2019; Criminal Case No. HAC 21 of 2018).

Case 16

This case involved foreign nationals living in Fiji at the time of the incident. The couple had been married for eight years and had three children together. The 39-year-old man accused his 44-year-old wife of having an affair with one of her male colleagues at work and being the source of their marital troubles. He brutally killed her and sent pictures of the badly bruised corpse to her father in their home country. The assailant reportedly attempted suicide following the murder and was sent to the psychiatric hospital by police. It is notable that some weeks before the homicide, the assailant had accused his wife of plotting with her father to kill him (Kumar Reference Kumar2021; Tuilevuka Reference Tuilevuka2021; State v. Kiala Henri Lusaka).

Case 17

The 28-year-old man, in this case, fatally stabbed his 27-year-old wife, with whom he had two children. At the time of the lethal assault, the couple had been separated for six months. The assailant had physical custody of the children, and the victim was living with a new male partner. The assailant stated in his cautioned statement that he plotted to kill the victim the moment she deserted him but later abandoned the idea. “He wanted to kill her as he [did] not want anyone to have her if he could not have her in his life.” The assailant was employed at a botanical garden, and he had planned the murder by digging a grave where he intended to bury the victim; he had even shown the grave to their children. A day preceding the murder, the victim called to inform her husband that she wanted to see her children as she intended to finalize the divorce petition and to relocate overseas to marry another man. The assailant promised to bring the children to work so she could see them. He did not bring the children as promised. Instead, he brought a kitchen knife with which he intended to slay the victim. Upon her arrival, the assailant confronted her with rumors circulating in the community about her alleged sexual affairs with other men. He then asked her to consider the welfare of their children and to return to the marital relationship. She demurred, telling him she was happier with her new partner. She tauntingly showed him love bite marks on her neck and gifts that her new partner had lavished on her. He told the court he felt provoked and reacted by stabbing her eight to nine times, specifically targeting the love bite marks. When the victim fell from the assault, he also stabbed her in the thighs. He took the mobile phone and bank card from the motionless victim’s purse and fled the scene. The assessors convicted the assailant of manslaughter, but the judge overturned the decision and convicted him of murder (Deo Reference Deo2016; Criminal Case No. HAC 5 of 2016).

Case 18

Information, in this case, was based on the testimony of the assailant and other witnesses. The assailant was 34 years old; the victim was 21 years old. At the time of the incident, they had lived together for two years in a de facto relationship. The woman left her home for one night. In his cautioned statement to police following the victim’s demise, the assailant stated that he found love bite marks on the victim’s neck when she returned home and was provoked by the victim’s alleged infidelity. She disputed the claim, saying the mark on her neck was merely a scratch mark. During the altercation, the assailant struck her face and asked her to pack her things and leave the house. She complied and left. She was found to have drunk paraquat (a herbicide) that day and later died at the local hospital. There was court testimony from a nurse who was attending the victim in the hospital. The nurse testified that the victim told her that the assailant gave her an ultimatum to drink the paraquat or face butchery with a knife. Although the assailant was convicted of murder by the assessors (trial jury), the judge overturned their decision and found the assailant guilty of the lesser charge of “assault occasioning actual bodily harm.” The assailant had six previous criminal convictions for assaults occasioning actual bodily harm (Kumar Reference Kumar2019; Prakash Reference Prakash2020; Criminal Case No. HAC 123 of 2018).

Case 19

The assailant and the victim, in this case, had been married for 10 years. Together, they had two daughters. The couple and their children lived together in a home adjacent to the husband’s parents. In his cautioned statement to the police, the assailant alleged that his wife was having sex with her male employer on multiple occasions. He stated that on the day preceding the homicide incident, his wife’s employer visited him and his family. He claimed that when the employer stayed overnight, he had sexual intercourse with his wife in front of him. The next morning, her employer left and returned in the late afternoon. He said he, his wife and her employer drank beer and played a card game together until 9:30 p.m. when he departed. At 11 p.m. that night, the assailant claimed he confronted his wife over having sex with her employer the previous night. He said his wife retorted that she would have sex with anyone she chose. The assailant said he asked his wife for sex. She refused. He then left the bedroom for the living room. He decided to kill her in revenge. At about 1 a.m., he went back to the bedroom where his wife lay asleep. He tied a scarf around her neck and tightened the noose until she died. He said he felt frightened afterward and contemplated suicide. He then walked to his father’s house and told him about the slaying before proceeding to the police station and surrendering himself (Criminal Case No. HAC 0014 of 2003L).

Case 20

The assailant, in this case, was 50 years old; the victim was 33 years old. At the time of the incident, they had co-resided for five years in a non-marital relationship. They were employed as a diver and receptionist, respectively, for a tourist company. On the day of the incident, the couple drank alcohol in their apartment from morning until midday. Then, they left to go and visit the victim’s relatives in another section of the city. While there, they drank alcohol with their hosts. They returned to their apartment at about 8 p.m. An argument broke out between the two whereby the assailant accused the victim of sexual infidelity. In the midst of the fight, the assailant grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed the victim eight times in the chest and armpit area. When the victim ceased moving, he discarded the knife and went to the local police station to surrender. In his cautioned statement to police, he said he assaulted the victim because “I wanted to pay back what she did to me, and I [knew] I will kill her at the time I was stabbing her.” The pathologist’s report attributed the death to “excessive blood loss due to multiple stab wounds.” The assailant pled guilty to the charge of murder and was sentenced to life imprisonment. The judge set 16 years as the minimum to be served before an executive pardon could be considered (Gounder Reference Gounder2016; Criminal Case No. HAC 179 of 2016S).

Case 21

The 21-year-old assailant and 19-year-old victim lived in a de facto relationship. On the day of the lethal incident, an argument erupted between them over the victim’s Facebook interactions with other men. The assailant grabbed a knife and stabbed her eight times on her back, causing her death. According to the pathologist’s report, “six of those stabbings [went] through her heart, and five of them had gone to the lungs which indicated the force that [he] used to stab the victim.” The assailant was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with a non-parole period of 18 years (Criminal Case No. HAC 249 of 2019).

Case 22

In this case, the 28-year-old man and the 16-year-old victim had lived in a de facto relationship for nine months. The victim abandoned the relationship and subsequently became a sex worker. The assailant raged over the victim’s encounters with other men. When the assailant declined his requests to return to the relationship, he sent her death threats through other sex workers and plotted to kill her. He organized a drinking party and invited the victim, another sex worker, and several male colleagues. At the party, the assailant struck the victim’s head with a stick, rendering her unconscious. He and his male colleagues then took turns sexually assaulting her. The assailant then throttled the victim and threw her body into the ocean nearby. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life with a non-parole period of 20 years (Criminal Case No. HAC 124 of 2008S).

Case 23

In this case, the assailant was convicted of the attempted murder of his de facto partner. On the day of the homicide, the couple went to a tavern to drink. They returned to their home at night with some friends and continued drinking. An argument erupted between them over the victim’s purported infidelity. When the victim wanted to leave the house with her friends, the assailant prevented her. The victim told the assailant to go and find another woman as she had another man. The assailant reacted furiously, grabbing a kitchen knife and stabbing her three times on her chest. Following a trial, he was convicted and sentenced to prison for life, with a non-parole period of eight years (Criminal Case No. HAC 365 of 2013).

Case 24

The assailant, in this case, was convicted of attempted murder. The assailant and the victim had lived in a de facto relationship for four years. The victim admitted in court that she had an affair with another man. She then left the assailant and moved about 13 miles away to be with the new partner. The assailant begged her to return. When she refused, he purchased a kitchen knife and stalked her. When he found her strolling in town, in the company of the other man, he approached and questioned her about the man. The victim said she was no longer interested in the assailant and had a new partner. The assailant pulled out the knife, kicked the victim down, and attacked her, inflicting several life-threatening injuries on her. A timely intervention by a bystander saved the victim from being killed. The assailant was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to prison for life, with the proviso that he serve a minimum of eight years before being eligible for parole (Criminal Appeal No. AAU 078 of 2015; High Court Case No. HAC 113 of 2012).

Case 25

A 28-year-old man was found guilty of the attempt to murder his 27-year-old de facto wife. He was sentenced to prison for life, with a non-parole period of seven years. At the time of the incident, the victim had left the couple’s home due to marital strife. She obtained a domestic violence restraining order and accompanied a police officer to notify the assailant. While the victim was packing her items to leave, the assailant outwitted the police officer, entered the house, and then locked the door from inside. He then grabbed a machete from within the house and repeatedly struck the victim on her head and arms as he yelled, “I will finish you today.” (Criminal Case No. HAC 87 of 2013)

Case 26

This case involved a 51-year-old man and his 32-year-old wife. They had two children, aged nine and eight years. The husband questioned the victim’s whereabouts the previous night, accusing her of drinking alcohol with the youths in the village. What followed was a volley of aggressive acts that nearly killed her. According to court records: “When she did not respond to your questions, you beat her in the legs, back and shoulders with the stick several times. When she went inside the house, you followed her and gave her more beatings until the stick broke. The violence continued. You punched her in the head and then tried to strangle her by pressing her neck with your bare hands. She kicked you hard when she started to choke. You fell backward. For a moment, she thought that the violence had stopped. But you continued with the violence on her after she did not respond to your accusations. You picked up the broken stick and gave her more beatings until she lost consciousness. She sustained multiple bruises and swelling all over her body. She was kept in the hospital for neurological observation for 24 hours before being discharged.” (Criminal Case No. HAC 317 of 2018)

Case 27

The assailant in Case 27 was convicted of the attempted murder of his ex-wife, against whom he harbored deep resentment for their divorce. The couple had been married for seven years and had two children, aged five and seven years old. On the day of the incident, the assailant went to the victim’s house ostensibly to see his children. He requested food and was served such by the victim, who chastised him for coming to her home in an inebriated state. He went to the kitchen sink, grabbed a knife, and stabbed the victim seven times on her upper body, stopping only when the knife blade bent, and the victim fell. The injuries were so grave that the victim was placed on a ventilator for 14 days. She also underwent surgery to repair a stab wound on her neck. In his cautioned statement to police, the assailant stated that “the victim had an extramarital affair while they were married and that was the source of their divorce”; he further said, “he was angry at the victim and wanted to teach her a lesson.” He said he felt sorry for his children but was satisfied that the victim would learn from the assault. He pled guilty to attempted murder and was sentenced to prison for life, with the condition that he serve at least eight years to be eligible for executive clemency (Criminal Case No. HAC 040 of 2015).

Case 28

This was a case of attempted murder. The assailant, in this case, shared residence with his wife and 14-year-old stepdaughter. He said he loved his wife so much so that he had her name tattooed across his chest. A month before the murder, he worked night shifts but returned home four hours early to find his wife engaging in “intimate acts” with another man. Following reconciliation talks, he accepted her back, but she continued the affair with the other man, leaving home nightly and returning at dawn. The assailant claimed he overheard the wife engaged in a telephone conversation with the same man and became enraged. He grabbed a cane knife and attacked the legs of both his wife and his stepdaughter, causing permanent physical disability to both victims. He was convicted of assault occasioning actual bodily harm and sentenced to prison for four years (Criminal Case No. HAC 160 of 2020).

Case 29

In this case, a 50-year-old man lethally stabbed his 29-year-old de facto wife on an allegation that she was having a sexual relationship with the landlord of their residential apartment. The victim left behind two young children from a previous relationship. On the day of the lethal incident, the couple began drinking alcohol early in the day. Around noon, they left home temporarily to visit the victim’s relatives in another part of the city but returned to resume drinking. An altercation erupted between them while they drank. Alarmed by the commotion, the landlord of their apartment counseled the husband to leave the apartment until tempers had cooled between the couple. According to the facts of the case, they both left the apartment together and joined their friends on a recreational fishing boat in another section of the city, where they continued drinking. Another altercation developed between the couple while they were on the boat. The assailant confronted the victim with an allegation of infidelity with their landlord, having interpreted the landlord’s suggestion that only he leave the apartment during their earlier argument as an indication that he wanted to be alone with her. When she rebuffed the charge, he responded by stabbing her in the chest with a knife. The autopsy report attributed the cause of death to “excessive loss of blood due to a stab wound.” According to the report, the stabbing “cut all three lobes of the victim’s right lung.” Following a court trial, the assailant was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life. The trial judge noted in his sentencing remarks that the assailant did not show remorse for his conduct. The judge ordered that he serve a 20-year prison term before becoming eligible for parole (Naidu Reference Naidu2012; Criminal Case No. HAC 176 of 2012).

Case 30

The 21-year-old male, in this case, accused his 20-year-old partner of behavioral impropriety over interactions she had on Facebook. Following an argument, the victim broke off the relationship. The assailant said he was upset over her unilateral decision to break up with him and vowed to kill her. He left a voicemail on her phone telling her that next Monday would be her last day alive. On the said day, he met the victim at a bus stop. He took a kitchen knife from his bag and stabbed her neck, head, and stomach. In his cautioned statement to police, the assailant stated he struck the victim several times “so that she does not survive.” He further stated that “if the victim is not his, then she cannot be of anyone else.” The victim was rescued by police personnel who perchance were nearby. The assailant pled guilty to the offense and was sentenced to prison for life with a proviso that he serve 15 years to be eligible for executive clemency (Criminal Case No. HAC 086 of 2017).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The current article has presented an analysis of male sexual jealousy homicides and attempted homicides in Fiji. Several of the findings are consistent with results obtained from studies conducted on the topic in Western societies. First, both real and perceived infidelity engendered tremendous rage in offenders, triggering vicious assaults against victims. Second, overkill was a dominant feature of the assaults as offenders bludgeoned, stabbed, slashed, strangled, and burned their victims. Third, a considerable age disparity existed between several offenders and their victims. Fourth, a small but significant percentage of the victims were pregnant at the time of the lethal incident.

A few of the findings deserve additional commentary. First, male sexual jealousy homicide is not new in Fiji. In former times, convicted defendants, like other capital offenders, received the death penalty. The last person to be executed in Fiji in 1964 was a 21-year-old man who massacred his wife, a three-month-old infant, and his 80-year-old grandfather. He suspected that the octogenarian was having a sexual affair with his young wife (Fiji Times 2014). Second, nearly all the cases examined in this study exhibited the ingredients of murder – premeditation, prior planning, and malice aforethought. In case after case, the assailant imagined or learned about the sexual infidelity of his partner. He then mounted a premeditated assault against her. Third, in many cases, the message of the aggrieved male partner appeared to be the common refrain found in the intimate partner femicide literature, “If I can’t have you, no one can.” One depressing effect of male sexual jealousy femicide is that it indirectly stultifies women’s drive toward independence in intimate relationships. Fear of lethal and non-lethal assault makes it difficult, if not impossible, for some women to contemplate leaving an unhappy marriage, thereby infringing on their wellbeing.

One recommendation emanating from this research is encouraging the responsible use of alcohol by citizens. A notable finding of this research was the heavy involvement of alcohol in several homicides. A large volume of scholarly research has documented alcohol’s role in committing violence (Auerhahn and Parker Reference Auerhahn, Parker, Dwayne Smith, Margaret and Thousand Oaks1999). Young people in Fiji are known for binge drinking and heavy liquor consumption (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah1995). It is imaginable that alcohol does not mix well with sexual jealousy. It may heighten emotions of jealousy and anger, fueling violence. Second, to reduce lethal violence, society should seriously tackle the problem of wife battery as every abusive relationship is potentially lethal. It is notable from the perusal of judicial documents that the imposition of sentences has been preceded by judicial comments that fulminate against the canker of men’s lethal and non-lethal abuse of marital and dating partners.

Additionally, the judicial documents contain comments directing married couples to utilize counseling and non-violent options to solve relationship difficulties. These messages have been given widespread coverage in the popular press. Stakeholders must seek to broaden the availability of these resources to make them impactful on people and their relationships. Only then can there be a meaningful reduction in the tragic crime of femicide. Additionally, values, beliefs and norms embedded in the culture that promote gender-based victimization of females and others must be challenged to achieve the societal goal of violence reduction.

One limitation of this study was the non-inclusion of trial transcripts in the study data. While summations (summing up), judgments, and sentences provided the most salient records in the trial, it would have been helpful to have access to the entire trial transcript that would include the interchanges between prosecution, defense teams and the rulings on motions. Future studies should endeavor to explore such data. Regarding the directions for future research, one of the current research findings is that several of the families involved in male sexual jealousy homicide had young dependent children. Future research should study the children of families where intimate partner femicide has occurred. Another study should focus on initial public reaction to a woman who has been killed by an intimate partner and responses to dispositional outcomes in these criminal cases.

Meanwhile, the Fiji police should develop a national digital database on homicide and provide adequate information on each case. This will assist scholars in identifying risk factors associated with each type of homicide, including intimate partner homicide. In conclusion, future research must continue to broaden the geographical and cultural contexts of scholarship into lethal intimate partner violence to enhance understanding of homicide as a form of human behavior.

Acknowledgements

The author is immensely grateful to Dr. Carmen M. White, Professor of Anthropology at Central Michigan University and Johnita Cody, PhD student in Sociology at Ohio State University, for reading previous drafts of the article and providing valuable comments.

Legal Documents

1. State v. Josevata Werelali Koroi. Criminal Case No. HAC 140 of 2020S.

2. State v. Fatai Peni. Criminal Case No. HAC 031 of 2020.

3. State v. Timoci Lolohea. Criminal Case No. HAC 099 of 2017S.

4. State v. Bimlesh Prakash Dayal. Criminal Case No. HAC 364 of 2011.

5. State v. Joeli Masicola. Criminal Case No. HAC 081 of 2014S.

6. State v. Nikasio Tupou. Criminal Case No. HAC 47 of 2010.

7. State v. Mohammed Yasin. Criminal Case No. HAC 163 of 2014LTK.

8. State v. Venktesh Permal Goundar. Lautoka Criminal Case No. HAC 091 of 2015L.

9. State v. Sailasa Mociu. Criminal Case No. HAC 052 of 2013S.

10. State v. Serupi Baba. Criminal Case No. HAC 212 of 2016.

11. State v. Sukhendra Prasad. Criminal Case No. HAC 0038 of 2004.

12. State v. Imshad Izrar Ali. Criminal Case No. HAC 018 of 2017.

13. State v. Josese Bale. Criminal Case No. HAC 046 of 2018.

14. State v. Yogesh Rohit Lal. Criminal Case No. HAC 46 of 2019.

15. State v. Tevita Vuniwai. Criminal Case No. HAC 21 of 2018.

16. State v. Kiala Henri Lusaka.

17. State v. Mohammed Samil Sahib. Criminal Case No. HAC 5 of 2016.

18. State v. Tevita Deve. Criminal Case No. HAC 123 of 2018.

19. State v. Avinesh Anand Singh. Criminal Case No. HAC 0014 of 2003L.

20. State v. Bernard Hicks. Criminal Case No. HAC 179 of 2016S.

21. State v. Suliasi Fuata. Criminal Case No. HAC 249 of 2019.

22. State v. Anesh Ram. Criminal Case No. HAC 124 of 2008S.

23. State v. Josateki Tabua. Criminal Case No. HAC 365 of 2013.