What drives public attitudes over trade policy? This question has received renewed attention as the political climates in advanced economies become more hostile to globalization; the answer is the subject of a long-standing debate among international political economy (IPE) scholars.Footnote 1 The predominant approach emphasizes material interests, with preferences based on the welfare consequences of trade for individuals as workers.Footnote 2 Drawing on economic models of the wage effects of trade liberalization, political scientists have developed arguments and empirical tests to explain when individuals will support liberalization, and when they will not. For example, there is a clear theory for how factor ownership (e.g., skill level) may affect preferences.Footnote 3 There is also a clear theory for how an individual's industry may bear on their policy preference.Footnote 4 More recent work in this vein emphasizes distributional consequences based on new new trade theory,Footnote 5 while additional lines of inquiry examine consumer interests,Footnote 6 nonmaterial determinants of preferences,Footnote 7 and the roles of information,Footnote 8 risk aversion,Footnote 9 and domestic compensation.Footnote 10

However, despite growing work in economics, political scientists have yet to explain how one of the most important economic identities—individuals' occupations—affect attitudes toward trade policy.Footnote 11 Occupations, which describe the nature of tasks performed by individuals in their job, are important determinants of labor-market outcomes.Footnote 12 They are directly linked to production because every good or service requires the completion of a set of tasks. Workers of different skill levels will have different capacities for performing different tasks. Given variation in factor endowments, some countries will be more efficient in the production of certain types of tasks. Thus the task content of trade directly affects individuals' welfare, based on the types of tasks individuals perform as part of their occupation.

The changing nature of global production provides another reason to focus on occupations. Namely, increasingly fragmented production is likely to make occupations even more relevant to the political economy of trade. Previous expansions of trade increased on the intensive margin (greater amount of existing goods/services), but today, fragmented production continues to increase trade on the extensive margin (new types of goods/services traded).Footnote 13 As a consequence, tasks performed by some occupations are now more easily provided from abroad. A new surge in offshoring—now one of the most visible aspects of international tradeFootnote 14 —has prompted some prominent economistsFootnote 15 to suggest that fragmented production and associated offshoring are akin to a new industrial revolution that transforms the consequences of globalization for workers.Footnote 16 The ability to “unbundle” production within an industry or even a firm means that competition from trade is often directed at specific jobs.Footnote 17 As a result, individuals in different occupations, but employed in the same industry or even in the same firm, may face different pressures from global competition. Thus, in addition to explaining how the task content of goods affects an individual's preferences over trade policy, an occupation-based theory is necessary to link the trade preferences literature to these fundamental shifts in the international economy.Footnote 18

We offer a new theory of trade policy preferences in which the winners and losers of globalization are determined by occupation characteristics. Building on the tasks literature from economics,Footnote 19 we argue that trade preferences are shaped by the task profile of occupations. In this view, tasks are the building blocks of production. Some countries have a comparative advantage in routine tasks (characterized by repetition or rule-following procedures), while other countries will have a comparative advantage in nonroutine tasks. As a result, task routineness is a key determinant of competitive pressures from trade. Thus, for countries with a comparative disadvantage in routine tasks, trade will more negatively affect workers in occupations intensive in routine tasks.

Routineness affects whether or not an individual will gain or lose from trade, but to understand the implications of fragmented production, we must also consider the degree to which individuals' job tasks could feasibly be provided from abroad. Therefore, we must also consider occupation offshorability: whether job tasks are location dependent and require face-to-face interaction.Footnote 20 Our focus here is not with the actual movement of jobs per se, but rather how occupation-based offshorability increases exposure to trade competition. Individuals in noncompetitive, offshorable occupations experience wage penalties as well as reduced job security. Offshorability magnifies the benefits to winners from trade and the costs to losers from trade.Footnote 21

Thus our theory combines the logic of task-based comparative advantage with modern concerns about fragmented production, particularly offshoring. Our theory predicts that in developed countries, individuals in routine occupations will be more protectionist than those in nonroutine occupations and this effect will be greater for individuals in more offshorable occupations. We use survey data for twenty-two developed countries from the 2003 and 2013 modules of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) National Identity survey to test our hypotheses. Our dependent variable is protectionist sentiment, and the occupation characteristics of routineness and offshorability are the primary independent variables. We find evidence to support our theoretical prediction that preferences over trade are a function of task routineness and offshorability, even after controlling for other factors suggested by the existing literature, including skill level and industry trade position. In particular, those in routine-task-intensive occupations are more protectionist than those in less routine occupations, and this effect increases in occupational vulnerability to offshoring. Adding to a vast literature in IPE on the determinants of individual preferences over trade,Footnote 22 our theory offers a new account of the welfare consequences of trade and explains patterns of protectionist sentiment that cannot be accounted for by the existing literature. Our findings therefore have important implications for the study of trade policy outcomes because they suggest a new source of preferences for labor based on occupation characteristics.

A Review of the Literature

Our theory builds on a relatively new area of research in labor economics known as the tasks approach.Footnote 23 Tasks are discrete units of work that are combined to produce goods and services. Thus the production of any good or service requires the completion of a set of tasks. Different factors of production (e.g., workers of different skill levels and capital) are the inputs used to accomplish tasks.Footnote 24 Each task defines a unit of work performed (e.g., lifting, typing, dissecting, editing), which leads to the production of an output (e.g., a burger, microchip, medical operation).Footnote 25 For workers, occupations represent bundles of tasks.Footnote 26

To understand the value of the tasks approach, first consider a closed economy with various factors, including workers of different skill levels, where a worker's skill is the capacity to perform the tasks necessary to produce a good or service.Footnote 27 High-skill workers (often defined by education level) are more productive, and thus have an advantage in producing more complex tasks.Footnote 28 Under the conditions of full employment and a perfectly competitive labor market, each subset of workers (high, middle, and low) earns a distinct wage in equilibrium and the continuum of tasks is divided among workers of low, medium, and high skill.Footnote 29

Next consider the possibility of trade in goods. In the tasks approach,Footnote 30 the production of these goods requires the completion of tasks to transform inputs into outputs: to produce one unit of a good, a continuum of tasks must be completed. Thus, tasks are implicitly bundled into the production of the good. Executing each task requires the input of one or more factors of production (some tasks are best executed by high-skill labor, some by low-skill labor, etc.). When fragmented production is not possible, goods are wholly produced using domestic factors of production in the producing country, but these goods still embody task content.Footnote 31 Countries have a comparative advantage in tasks that rely on the relatively abundant factor, and thus in the production of goods intensive in those tasks.

Today, however, international trade includes more than final goods; it also includes trade in the work to produce such goods, with production occurring in a number of locations.Footnote 32 The information age is accelerating this expansion, and the unbundling of production is transforming the nature of international trade and production.Footnote 33 The rise in intrafirm and related party trade, as well as the disparity between gross and value-added trade flows, are evidence of this phenomenon.Footnote 34 An American car, for instance, is made up of parts produced all over the world,Footnote 35 while China contributed $6.50 in value added (through parts assembly) toward the overall factory cost of an iPhone of $187 in 2010.Footnote 36 Not only does this fragmentation of production see jobs moved offshore, it also generates attendant flows of trade in goods or services imported back onshore.Footnote 37

To understand the distributional consequences of this process, we must therefore consider a model of trade that also integrates trade in production activity.Footnote 38 In particular, when fragmented production is possible, firms in the home country can offshore segments of the production process of exported and import-competing goods to a foreign country.Footnote 39 Wage gaps between workers in the home and foreign country at all skill levels create incentives for firms to offshore all tasks that can be provided more cheaply by foreign labor.Footnote 40 The content of trade changes as firms import those intermediate inputs now produced by foreign workers. This trade changes the composition of tasks produced in the domestic economy, as the set of tasks performed by each factor shifts in response to these market forces, such that the lowest cost factor performs a given task in equilibrium.Footnote 41 Again, in the presence of full labor-market mobility, the reallocation of skills across tasks will occur so that workers of the same skill level earn the same wage.

A Task-based Theory of the Distributional Consequences of Trade

Our theory provides insights into the welfare consequences of trade in a world with and without offshoring. In contrast to factor-ownership or industry suggested by the Stolper-Samuelson and Ricardo-Viner models, we argue that winners and losers will be determined by occupation characteristics: how competitively tasks are executed, based on comparative advantage, and how easily those tasks can be performed abroad.

First, we relax the assumption of full labor mobility. Instead we suggest that mobility for workers to move across occupations is limited. Limited labor-market mobility may result from a number of labor-market frictions, including lack of qualifications to perform certain tasks or unobserved heterogeneity (e.g., worker productivity).Footnote 42 There are also often hurdles to changing occupations (e.g., licensing and accreditation requirements). Whatever the source of friction,Footnote 43 if workers are stuck in their occupation, then workers' occupations will shape how they are affected by trade liberalization.Footnote 44 Therefore, occupation characteristics determine whether trade benefits or harms individuals. As a result, trade will lead to distributional pressures along occupation lines.

However, the international economics literature is largely silent about precisely how these occupation cleavages will form and what the relevant fault lines are between occupations. That is, theoretical models of trade in tasks provide insight into the distributional consequences of trade, and especially offshoring via fragmented production.Footnote 45 But we must look to labor economics for empirical definitions and measures of relevant task characteristics that shape exposure to trade and competitiveness. Drawing on insights from both fields enables us to define key task characteristics. In particular, we propose that the distributional consequences of trade are shaped by task routineness, which captures competitive pressures (positive or negative), and offshorability, which captures the feasibility of providing a given occupation task from abroad.

Task Routineness

Recent work in economics introduces the routineness of a task as a key determinant of competitiveness in the global economy.Footnote 46 Routine tasks are those that follow a script or set of rule-based procedures.Footnote 47 Routine tasks may include manual activities (e.g., production tasks like the assembly of a manufactured good), as well as cognitive tasks involving sales, and clerical and administrative support (e.g., data transcription or record keeping).Footnote 48 In contrast, nonroutine tasks may also include manual tasks, such as truck driving or food preparation, as well as cognitive tasks associated with professional and technical occupations (e.g., management of staff, practice of medicine).Footnote 49 Routine tasks are more readily taught to foreign workers because they are codifiable.Footnote 50

In the tasks framework, skills must be mapped onto tasks. Thus we cannot simply say that routine tasks are low skill and nonroutine tasks are high skill. The nonroutine category of tasks includes some very high- and some very low-skill jobs: nonroutine manual tasks tend to be low-skill, while nonroutine cognitive tasks tend to be high skill.Footnote 51

If tasks transform inputs into outputs (i.e., products), how does routineness relate to a country's comparative advantage and disadvantage in tasks? Low- to medium-skilled labor tends to be used intensively in the execution of routine tasks, as demonstrated by a large empirical literature in labor economics.Footnote 52 Therefore, countries that are relatively abundant in low- to medium-skilled workers will have a comparative advantage in the supply of routine tasks and thus in goods and services that are intensive in routine tasks in their production.

Developed countries, on the other hand, are relatively abundant in high-skill labor and relatively scarce in low- and medium-skilled labor. Therefore, developed countries will have a comparative advantage in tasks that utilize high-skilled labor relatively more intensively, and a comparative disadvantage in routine tasks because they utilize low- and medium-skilled labor more intensively.Footnote 53 In developed countries, individuals in occupations that are routine task-intensive are less competitive internationally and thus more likely to be hurt by international trade because they face greater competition from foreign labor. This is true of both services (routine cognitive) and manufacturing (routine manual).Footnote 54

However, a comparative disadvantage in routine tasks does not imply a comparative advantage in all types of nonroutine tasks. Different subsets of nonroutine tasks are likely to be performed by low-skill workers and another subset is likely to be performed by high-skill workers. The difference largely depends on whether the task is manual or cognitive. The production of nonroutine cognitive tasks tends to be intensive in high-skill labor and therefore workers in such occupations will be in demand. Thus individuals in occupations that are intensive in nonroutine, cognitive tasks are likely to benefit from international trade. The welfare implications for individuals in occupations intensive in nonroutine, manual tasks are less straightforward because it is less likely that these tasks can be provided from abroad. This non-monotonicity between routineness and skill level can help explain well-documented patterns of labor-market polarization in developed countries where the demand for middle-skill workers has fallen relative to high- and low-skill workers.Footnote 55

Occupation Offshorability

Routineness is a task characteristic that helps to determine tasks' competitiveness,Footnote 56 but it does not specify which tasks are vulnerable to offshoring. In particular, firms' ability to split up the production chain means that individuals in different occupations, but employed in the same industry or even in the same firm, may face different pressures from global competition. This leads to the second key determinant of labor-market outcomes: offshorability—the degree to which an individual's occupation is intensive in tasks that can be provided from abroad.

Not all bundles of tasks are easily provided from abroad: some tasks depend on a specific location (farming, park rangers) or require face-to-face interaction (hair stylists, management), and are thus more difficult to relocate.Footnote 57 Occupations intensive in non-offshorable tasks are less exposed to this dimension of trade.Footnote 58 On the other hand, many manufacturing tasks (assembly of clothing) and services tasks (customer service, bookkeeping) can be transported physically or electronically. These tasks are more offshorable, and thus more exposed to trade.Footnote 59

Although offshorability has a negative connotation,Footnote 60 we use it to mean tasks are tradable in the sense that a particular task can be provided from abroad. Much of the existing work conflates whether a task can possibly be provided from a remote location with characteristics of the task that determine whether it is likely to be offshored.Footnote 61 However, this conflation overlooks the difference between the ability to offshore a job, and the benefit to doing so.Footnote 62 For our purposes, offshorability explains only whether a task can be provided from abroad. It therefore captures the possibility of tasks being imported, but also of tasks being exported (offshoring and onshoring, respectively).

Occupational Winners and Losers from Trade

The degree to which individuals' occupations are intensive in both routine and offshorable tasks determines whether, and how much, individuals benefit from or are hurt by trade. Specifically, the expected impact of trade on an individual's welfare is a function of the routine content of tasks, conditional upon the offshorability of tasks. In developed countries, which are less competitive in performing routine tasks, trade is likely to harm individuals in occupations intensive in routine tasks. When tasks can be provided from abroad (i.e., when they are offshorable), workers are more exposed to international trade competition. Therefore, the welfare consequences of trade are magnified for these workers.

For workers in uncompetitive, offshorable jobs, trade liberalization exerts downward pressure on wages. This is true even if jobs are not actually offshored: a large literature in economics finds that individuals in offshorable, noncompetitive occupations experience negative welfare consequences, in terms of wages, job security and employment outcomes. For example, a recent study of US workers between 1948 and 2002 finds no evidence that industry exposure to globalization affects wages, but instead finds large negative wage effects for occupational exposure to globalization, especially for routine production workers.Footnote 63

We use the word offshoring, broadly defined, to represent the transfer of production activity (goods or services) abroad. Offshoring (in the narrow sense of the transfer of existing jobs abroad) does not actually need to occur for workers in offshorable occupations to realize these negative distributional consequences. The possibility of offshoring in and of itself can create these pressures.Footnote 64 Indeed, just looking at the number of jobs offshored (in the narrow sense) likely understates the true impact of the phenomenon because we can never know how many jobs would have been created in the domestic economy if not for offshoring.Footnote 65 Thus it is important to distinguish occupation offshorability, the job characteristic, from narrowly defined offshoring, which is the action of jobs being offshored. Of course, for those individuals whose jobs are moved overseas, the wage effects are even more dramatic and there may be significant adjustment costs associated with finding a new job. In the aggregate, the disruption and transition costs associated with increasing offshoring are likely to be large in magnitude, with the potential for lasting, involuntary unemployment.Footnote 66

In developed countries, individuals in occupations intensive in nonroutine tasks may benefit from trade through the onshoring of tasks and the expanded production of exported goods and services intensive in these tasks.Footnote 67 In other words, those in nonroutine, offshorable occupations may benefit from trade. This includes, for example, tasks in service-based occupations that rely heavily on knowledge or creativity, like research and design. This highlights the developed economies' comparative advantage in certain production activities.Footnote 68

Because offshorability magnifies the welfare consequences of trade, the welfare outcomes for individuals in occupations intensive in non-offshorable tasks are less pronounced. Those in routine task occupations face competition as a result of trade liberalization from the import of goods intensive in routine tasks even if their occupation is non-offshorable. When it comes to nonroutine, non-offshorable occupations, developed countries are scarce in low- and medium-skilled labor, but many low- and medium-skill occupations are less threatened by trade because fragmented production is not possible (e.g., food service). Members of the scarce labor factor, whose occupation is difficult to shift abroad, may be more insulated from the wage effects of trade competition than those of similar or even higher skill, whose occupation is more offshorable. Of course, there is the possibility of negative wage effects for low- and medium-skill workers if the excess supply of workers made redundant by trade begins to compete for the same tasks.Footnote 69 Conversely, some nonroutine, non-offshorable tasks (i.e., cognitive personal) are high skill (e.g., medical profession). Individuals in such occupations will benefit from trade less than their counterparts in offshorable occupations.

We summarize our expectations about the distributional consequences of trade in developed countries according to the occupation characteristics of routineness and offshorability in Table 1. On the first dimension, we have routineness, which determines the competitiveness of an occupation. Unconditionally, those in routine-task-intensive occupations are going to be negatively affected by trade liberalization. On the second dimension we have offshorability, which determines occupation exposure to competition from trade (especially with fragmented production). In contrast to routineness, which has clear implications for welfare, the unconditional effect of offshorability on the welfare consequences of trade is ambiguous. For ease of illustration, we have broken routineness and offshorability into two categories each.

Table 1. Welfare consequences of trade by occupation archetypes

Note: These are the posited distributional consequences for developed countries

In the upper-left corner (Group A), we see that individuals in highly offshorable, highly routine occupations are the most likely to be hurt by trade. This group includes manufacturing workers like machine operators, as well as routine cognitive workers, such as software writers, bookkeepers, accountants, or data entry technicians. Members of this group (in developed countries) are likely to face negative welfare outcomes as a result of trade liberalization because of comparative disadvantage in routine tasks, combined with lower wages in developing countries at all skill levels. In the upper right, Group B includes those individuals in highly offshorable, nonroutine occupations including, for instance, computer systems designers or consultants, who are likely to benefit from trade through onshoring. As a comparison between Groups A and B, consider a computer programmer (A) and a computer systems designer (B). The programmer (ISCO-88 code 2132) focuses on the technical aspects of producing software (writing, testing software), with a routine task intensity score of 0.51.Footnote 70 Systems designers (ISCO-88 code 2131), on the other hand, “conduct research, improve or develop computing concepts and operational methods, and advise on or engage in their practical application”Footnote 71 and as such have a routine task intensity score of -0.09 (where higher values indicate more routine task-intensive occupations). Both of these occupations have similar levels of offshorability, yet the job of the programmer (which is more routine) is likely to be offshored and the job of systems designer (which is less routine) is more likely to be onshored.

In the bottom row, we have individuals in low-offshorability occupations; thus they are not directly exposed to trade competition through offshoring because it is difficult or impossible for core job tasks to be provided over a distance. However, trade may affect individuals in non-offshorable occupations in two ways. First, the task content of tradable goods or services can shape the welfare consequences of trade even in the absence of offshoring. In other words, those in non-offshorable jobs still may be affected by the task content of trade even if fragmented production is not possible. Specifically, individuals in highly routine non-offshorable jobs will be negatively affected by trade (Group C), but to a lesser extent than those in Group A. Those in highly nonroutine jobs may be positively or negatively affected by trade (Group D).

Second, trade may indirectly harm (benefit) individuals in non-offshorable occupations if trade reduces (increases) demand for workers with a similar skill level. In Group C, individuals in non-offshorable, routine jobs may also be hurt by trade because of increased competition for those jobs by individuals displaced by trade. Similarly, those individuals in low offshorability, nonroutine jobs (Group D) may benefit from trade as demand for workers capable of performing nonroutine tasks increases.Footnote 72

Occupation-Based Preferences Over Trade

Trade preferences are determined by the welfare consequences of trade for workers, which we generally refer to as wage effects (while acknowledging additional labor-market consequences like increased job insecurity). If someone's wage increases as a result of trade liberalization, we expect that person will be more in favor of policies that further open markets to international trade; if wages decrease, the individual will be opposed to liberalization, while individuals unaffected by trade will be neutral. Our theory of distributional preferences suggests that the interaction between occupation characteristics of routineness and offshorability will shape support for trade protection.

According to the expected welfare outcomes in Table 1, for developed countries, those in highly routine jobs (Groups A and C) are likely to be protectionist. Those in highly routine and offshorable jobs (Group A) are the most likely to be protectionist because they experience the largest negative welfare outcomes from trade. Those who are in nonroutine, highly offshorable jobs (Group B) are most likely to benefit from trade, and are thus likely to support trade liberalization. Building on the earlier example, we would expect a computer programmer to be more protectionist than a computer systems designer. Among those in low offshorability, nonroutine occupations (Group D), individuals may be indifferent to trade protection, or their preferences may align with exposed workers with similar skill levels as trade changes the composition of tasks performed in the domestic economy and thus the demand for workers of different skill levels. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H1

Individuals with higher levels of task routineness are more likely to support trade protection.

H2a

Individuals with higher levels of task routineness will be increasingly likely to support trade protection as occupation offshorability increases.

H2b

Individuals in offshorable occupations will be more likely to support protection as the level of occupation routineness increases.

We now briefly contrast the expectations of the occupation-based model with other accounts of the material interests found in the political science literature. We emphasize that sectors and occupations represent different economic identities than factors do.

Recall that under Heckscher-Ohlin (HO), factors are fully mobile within the domestic economy and thus preferences over trade will be determined by individuals' factors. In the case of labor interests, these cleavages emerge between individuals of different skill levels.Footnote 73 In developed countries, this means that high-skill individuals will support trade openness and low-skill individuals will support protection because of the assumption of perfect factor mobility. Empirical evidence in support of this claim is robust; many studies of individual preferencesFootnote 74 use education level as a proxy for skill-level and find support for the predictions of the HO model.Footnote 75

Under full mobility, the occupation-based model would produce similar factor-based expectations about cleavages and preferences to the HO model because no factor would be “stuck” in a specific occupation. If, as we argue, labor-market friction leads to less-than-perfect labor-market mobility, restricting the reallocation of one's factor from one occupation to another, then factors may be stuck in their occupations. This will lead to wage effects by occupation (and not simply the type of factors one owns).Footnote 76 Thus the occupation-based model predicts cleavages will occur across occupations depending on task routineness and offshorability.

The occupation model also differs from Ricardo-Viner (RV) in which owners of the same factor can have different trade preferences depending on whether they are in an industry of comparative advantage or disadvantage. Under RV, trade preferences occur on the basis of industry, and individuals in exporting industries will support openness, while those in import-competing industries are likely to support protection.Footnote 77 Industries have different (overlapping) combinations of occupations and most occupations do not belong to a unique industry. In other words, some occupations may be limited to one or just a few industries, while other occupations may be found in many or even all industries. Thus, in the RV model, a call-center representative working in the manufacturing sector would simply care about their industry of employment, rather than the offshorability of their occupation. In the occupation-based model, the call-center worker would be more likely to have similar attitudes to other call-center representatives in other sectors, rather than a production worker in the same sector. This would also be true of workers in those non-offshorable occupations found across a number of industries. Thus, the political cleavages over trade policy predicted from these two trade models may be dramatically different, with one predicting demand for protection by sector and the other predicting demand for protection along occupation lines.Footnote 78 The implications of this model also emphasize the difference between services industries and service occupations, given that many service occupations are found throughout the economy.

Finally, the cleavages we present are distinct from those suggested by new new trade theory.Footnote 79 Drawing on new new trade theory, Walter argues that being exposed to trade benefits the high skilled and hurts the low skilled.Footnote 80 Labor-market inequality between these groups should therefore be much bigger than labor-market inequality among individuals sheltered from globalization. Thus Walter anticipates cleavages within skill levels based on exposure to trade (which could lead to cleavages within skill groups based on occupation offshorability). In contrast, the critical point of our argument suggests that the source of competitive pressures is based on the routineness of job tasks. We therefore anticipate cleavages along occupation lines, based on task routineness and offshorability, rather than within skill levels.

The potential explanatory power of the occupation model is best demonstrated by considering the following example of a computer programmer and an information technology (IT) project manager in the IT industry. According to the O*NET database, both computer programmers and IT project managers typically have a four-year degree or greater, suggesting those individuals are endowed with similar skill levels. Under HO, both individuals should prefer trade liberalization because, as owners of the abundant factor, their wages should increase. Under RV, both individuals should have the same preference in favor of trade liberalization because they are in the same industry. Neither HO nor RV can account for the fact that companies are able to offshore computer-programming jobs to other countries, and thus it is the occupation-based model that can explain why a computer programmer should be more protectionist than a project manager as a result of greater offshorability and task routineness. More generally, the occupation-based model provides an explanation for why high-skill individuals, in well-paying “white-collar” jobs, may have an incentive to support trade protection.Footnote 81

Research Design

We use data from the 2003 and 2013 National Identity modules of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) to test our hypotheses that preferences over trade are a function of task routineness and offshorability. The ISSP, which codes occupations using the four-digit International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88), is one of the only surveys to both ask about trade and provide detailed occupational data in the public sample. Disaggregated information about individuals' occupations is necessary to generate meaningful measures of occupation characteristics. We limit the sample to high-income democracies because of our expectations about the relationship between task competitiveness and protectionist sentiment. Thus, the sample includes twenty-two countries in 2003 and twenty countries in 2013. Table 6 in the appendix lists countries in each sample. The 2013 sample includes seventeen countries from the 2003 sample, as well as one newly classified high-income countries (the Czech Republic).Footnote 82 We have 18,772 and 22,560 respondents in the 2003 and 2013 models, respectively. Both samples use the same measures of independent and dependent variables.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable, support for trade protection, measures individuals' protectionist sentiment. Respondents were asked how much they agree or disagree with the statement that their country “should limit the import of foreign products in order to protect its national economy.”Footnote 83 We examine the following responses: disagree strongly, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and agree strongly (excluding those who responded “can't choose”). The answers range from 1 to 5. Higher values indicate greater support for limits on imports, and thus greater protectionist sentiment. The mean level of protectionist sentiment for each country in 2003 appears in Figure 1. (See figure for 2013 in the online appendix.) Denmark has the lowest mean level of support for protection, while Australia and the United States have the highest levels of support for restrictions on imports. In robustness checks, we examine additional measures of protectionist sentiment, including a question on attitudes toward the activity of multinational firms.

Figure 1. Mean level of support for trade protection by country in 2003

Independent Variables

Our main independent variables are the occupation characteristics of routineness and offshorability. Because occupation measures are fairly new in political science, we discuss how information on occupation work activities and work context is used to generate occupation-specific measures of routineness and offshorability.Footnote 84 Occupation tasks are classified using detailed occupation information available from the United States O*Net (occupational information network) database.Footnote 85

Our first independent variable is routine task intensity (RTI), which we measure using the routine task intensity (RTI) index.Footnote 86 As the name suggests, this index measure captures the importance of routine tasks relative to other task types. To construct this measure, we use occupation scales measuring the degree to which job tasks are: routine cognitive, routine manual, nonroutine manual (physical and personal), and nonroutine cognitive (analytical and personal).Footnote 87 RTI is equal to ln(Routineness) − ln(Abstractness) − ln(Manualness), where routineness is the combination of manual and cognitive routineness, abstractness is the combination of nonroutine (cognitive) personal and analytical, and manualness is the combination of nonroutine physical and nonroutine personal.Footnote 88 Higher values indicate that occupations are more intensive in routine tasks. The measure is centered, and ranges from −2.12 to 2.49, with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 0.59.Footnote 89 It is normally distributed. We expect that as individuals' occupation RTI increases, protectionist sentiment will increase as well. We also examine the absolute level of task routineness in robustness checks presented in Table 5.

Our second independent variable is offshorability, which captures the degree to which tasks must be performed face-to-face or on site. Thus this is a measure of vulnerability to competition from offshoring. We use Blinder's measure of offshorability as our key indicator of occupation offshorability.Footnote 90 This is a categorical index that classifies occupations into four groups (highly non-offshorable, non-offshorable, offshorable, highly offshorable), based on the degree to which job tasks can be provided from a distance or are specific to a particular location.Footnote 91 We construct a dummy variable equal to 1 if an occupation is offshorable and 0 otherwise. In robustness checks in Table 5, we present results using an alternative, continuous measure of offshorability.Footnote 92

The existing literature suggests a number of additional factors that may shape trade preferences. First, we include years of schooling as a measure of individuals' skill endowment.Footnote 93 We expect that those who are more skilled will be less protectionist as predicted by factor endowments theory. This is also consistent with the implications of intra-industry tradeFootnote 94 for the welfare of workers. Moreover, education may also influence attitudes toward trade for reasons that are unrelated to its implications for economic well-being.Footnote 95

Second, we include measures of exposure to trade as suggested by sectoral theories. Because the ISSP does not ask respondents directly about their industry of employment, we construct a measure of exposure to trade in goods for each occupation i in country j.Footnote 96 We collect data on imports and exports for each industry k in country j for the years 2002 and 2012 from the OECD Structural Analysis (STAN) database. We then generate dummy variables to indicate whether industry k is an industry of comparative advantage or disadvantage for country j.Footnote 97 Occupation i’s exposure to trade in industry k is weighted by the share of occupation i’s employment in industry k relative to the rest of the economy.Footnote 98 These employment weights are based on data from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for 2002 and 2012.Footnote 99 The comparative advantage of each occupation i in country j is thus calculated as

where ca jk is a dummy variable equal to 1 if industry k is a source of comparative advantage for country j, and w ik (constant across countries) is the share of employment of occupation i in industry k. Comparative disadvantage is calculated in a corresponding manner. Comparative advantage and comparative disadvantage range from 0 to 1 and both are logged to account for skewness. For those occupations that are not exposed to trade in goods, both comparative advantage and disadvantage are equal to 0.Footnote 100 In a robustness check in the online appendix, as an alternative proxy for industry exposure to trade, we use a dummy variable equal to 1 for manufacturing occupations.

We control for two additional labor-market variables: unemployment status and union membership. Unemployed and union member are equal to 1 for individuals who are unemployed and union members, respectively. We expect those who are unemployed or union members to be more protectionist compared to the reference categories.

The existing literature suggests important nonlabor-market factors that may also shape attitudes toward trade. First, we control for respondents' sex because women are shown to be more protectionist than men in a number of studies.Footnote 101 Second, we control for age. Third, we include an index of nationalist sentiment to control for the effect of nationalism.Footnote 102 The measure is a scale created by adding responses to the statements “I would rather be a citizen of [Country] than any other country in the world” and “The world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like people from [Country].” Higher values indicate greater nationalist sentiment and we expect those who are more nationalistic will be more protectionist.

Summary statistics for each sample are presented in Table 7 of the appendix. Overall, the samples look very similar in terms of the key independent variables. In Table 2, we present the correlation of key variables for both 2003 and 2013. Correlations for 2013 are reported in the parentheses. Routineness and offshorability are correlated at the level 0.22 (0.18). Of particular importance, there is a moderate negative correlation between routineness and education (ρ = −0.38, −0.37 in 2003 and 2013, respectively). This suggests that although individuals with a greater skill endowment are less likely to be in routine-task-intensive occupations, these two variables capture different sources of variation in the data and differ conceptually as suggested by the theory. Moreover, offshorability is not correlated with schooling, and is only modestly correlated with industry trade exposure, again suggesting that the concept captures a different dimension of labor-related trade exposure.

Table 2. Correlation of key variables in 2003 and 2013

Notes: 2013 values in parentheses. Bolded values significant at 95 percent level.

Results

We estimate ordinary least squares regression using survey weights.Footnote 103 We include country fixed effects to capture important variation in domestic political and labor-market institutions, as well as welfare spending and the level of development. The results appear in Table 3.

Table 3. Analysis of support for trade protection

Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. Country fixed effects included. * p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

In Model 1, we examine the unconditional effects of routineness using the routine task intensity index (RTI) and offshorability on protectionist sentiment for 2003. The coefficient on rti is positive and statistically significant, consistent with Hypothesis 1. This finding suggests that as routineness increases, individuals are likely to be more protectionist because they face greater competition from globalization.Footnote 104 Ex ante, the expected direct effect of offshorability on protectionist sentiment is ambiguous because individuals in highly offshorable occupations include those whose jobs are likely to be offshored, and those whose jobs are likely to be onshored. In our sample, the coefficient on offshorability is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that as vulnerability to offshoring increases, individuals are less likely to hold protectionist attitudes, all else equal.

The coefficients on other measures of labor interests are consistent with expectations put forth by the literature. First, the coefficient on schooling is negative and statistically different from 0 in all models. This is consistent with the factor endowments model, as well as robust findings in the literature.Footnote 105 The coefficient on comparative advantage is negative and statistically significant at the 95 percent level, suggesting that those in occupations typically employed in industries of comparative advantage tend to be less protectionist, all else equal. The coefficient on comparative disadvantage is positive and statistically significant from 0 at the 90 percent level.Footnote 106 In terms of control variables, the coefficient on nationalist sentiment is also positive and statistically significant, suggesting that greater nationalist sentiment leads to more protectionist preferences. Finally, consistent with other studies, women are more likely to be protectionist than men.Footnote 107 These findings are generally robust across the remaining model specifications.

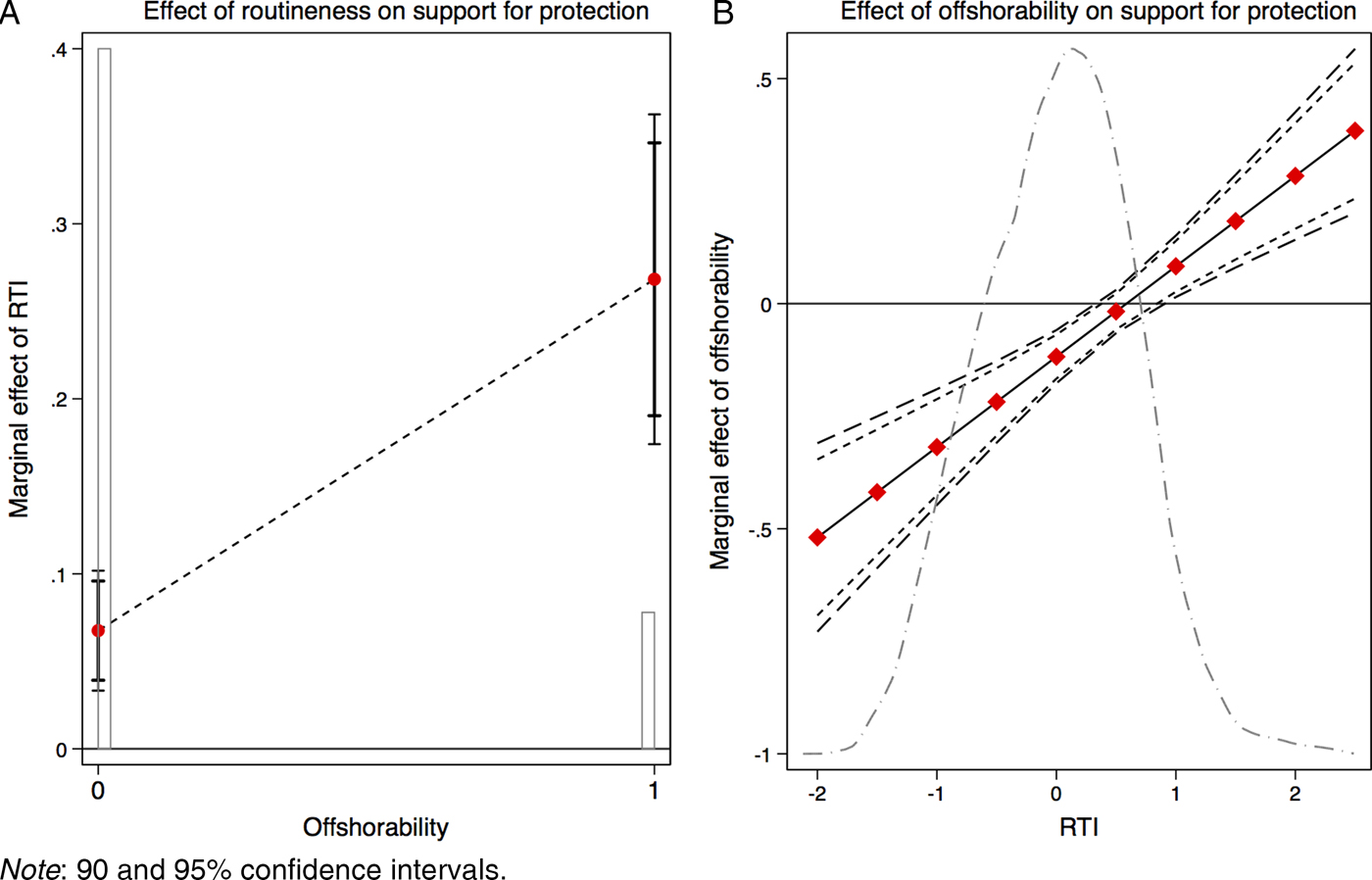

Our theory suggests that the effect of offshorability on trade preferences will depend on routineness and vice versa. In Model 2 we include an interaction between routineness and offshorability as the first test of our conditional hypothesis. The coefficient on the interaction term is positive and statistically significant as hypothesized. To facilitate the substantive interpretation of the interaction, in Figure 2, we present the marginal effects of routineness and offshorability, along with the distribution of each conditioning variable. In Panel A of Figure 2, we present the marginal effect of a one-unit increase in routineness on protectionist sentiment, conditional on observed levels of offshorability. The marginal effect of routineness is increasing in the level of offshorability and leads to an increase in protectionist sentiment. For those in non-offshorable occupations, an increase in routineness leads to a small increase in protectionist sentiment. For those in offshorable occupations, an increase in routineness leads to a larger increase in protectionist sentiment. This finding is consistent with Hypothesis 2A. Moreover the effect is substantively as well as statistically significant. For instance, a one-unit increase in routineness leads to a 0.068-point increase in protectionist sentiment for those in non-offshorable occupations, but a 0.27-point increase for those in offshorable occupations.Footnote 108 This would be a change in routineness similar to that of moving from a Nursing and Midwifery Associate Professional occupation (RTI=−0.43) to a bookkeeping occupation (RTI = 0.43) or telephone switchboard operator (RTI = 0.44). This increase is statistically and substantively significant. For comparison, consider that a four-year increase in schooling reduces support for protection by -0.22 points.Footnote 109

Figure 2. Marginal effects plots for Table 3, model 2

In Panel B, we present the plot of the marginal effect of offshorability on support for protection. Moving from a non-offshorable occupation to an offshorable occupation has a negative and statistically significant effect on the level of protectionist sentiment at low levels of routineness and a positive and statistically significant effect at high levels of task routineness. In other words, among individuals whose occupations are characterized by low levels of task routineness, an increase in offshorability leads to greater support for free trade. The opposite is true for those in occupations of high levels of routineness. This finding, that offshorability can reduce protectionist sentiment, is consistent with Hypothesis 2B because those in nonroutine jobs are likely to benefit from international trade: occupations that are both offshorable and intensive in nonroutine tasks are likely to be onshored. Again, the results are substantively significant. Moving from an offshorable to non-offshorable job at the minimum level of routineness reduces support for protection by -0.54 points, while the same change at the maximum level of routineness increases support for protection by 0.38 points.Footnote 110

In terms of model fit between the interactive (Model 2) and non-interactive (Model 1) model, the significance of the interaction term, in combination with an improvement of the AIC and BIC statistics, suggests that the interactive model is preferable to the non-interactive model, although the direct effects of offshorability and routineness are also important sources of variation in preferences over trade.

The results for 2013 are presented in Models 3 and 4 of Table 3. In the interest of space, we discuss only the results for the interactive model specification reported in Model 4. We again find support for our hypothesis that the effect of routineness is conditional upon offshorability (and vice versa). Figure 3 presents the marginal effects plots for routineness and offshorability. The results in 2013 look similar to those for 2003 just discussed in Figure 2. An increase in task routineness leads to an increase in protectionist sentiment as Panel A shows, and the increase is larger for those in offshorable occupations. As before, the effect of offshorability on protectionist sentiment is increasing in the level routineness as shown in Panel B, and is negative at low levels of routineness and positive at high levels of routineness.

Figure 3. Marginal effects plots for Table 3, model 4

Finally, Models 5 and 6 of Table 3 compare the results of our interactive model for 2003 and 2013 when the samples are limited to the set of countries surveyed in both years. For ease of comparison, we plot the coefficients with 95 percent confidence intervals in Figure 4. The results suggest that there is little fluctuation in the size or significance of the relationship between routineness, offshorability, and protectionist sentiment, even in two samples from the same population separated by ten years. This suggests that occupation and concerns about offshoring/onshoring continue to be an important determinant of trade preferences.Footnote 111 Overall, the effects of offshorability and routineness do not appear to depend on the countries in the sample or on the year of analysis.Footnote 112

Figure 4. Regression coefficients from restricted 2003 and 2013 samples

We also find that the occupation model performs well in terms of explanatory power relative to other model specifications based on the key labor-market variables suggested by the literature (factor and industry variables in particular). As one example of this, Figure 7 in the appendix presents the BIC scores for a number of different models suggested by the literature, where smaller BIC scores indicate better model fit. The results suggest that adding the occupation variables suggested by our theory (routineness, offshorability, and the interaction between them) improves our understanding of trade preferences over models that include only factor or industry interests.Footnote 113 Additionally, we find some evidence that the impact of offshorability may also be conditional on years of education.Footnote 114 See the online appendix for a full discussion of these results. This is not to say that occupation matters to the exclusion of skill or industry, simply that occupation characteristics matter. Future work with sharper measures of industry and skill endowment, as well as labor mobility, should examine the extent to which these different theories are competing or complementary.

Robustness

To explore the robustness of our findings to alternative measures of our key variables, first we examine an alternative measure of preferences toward trade using the prompt: “Large international businesses damage local businesses.” The outcome is scaled such that higher values (more agreement with the statement) indicate more protectionist sentiment. Although the ISSP does not include a question on offshoring per se, multinationals play a large and well-documented role in globally fragmented production.Footnote 115 Thus attitudes toward multinational activity in this item represent an additional measure of preferences toward trade with fragmented production. Factor analysis of this item and the main dependent variable suggest that both tap an underlying protectionist sentiment.Footnote 116

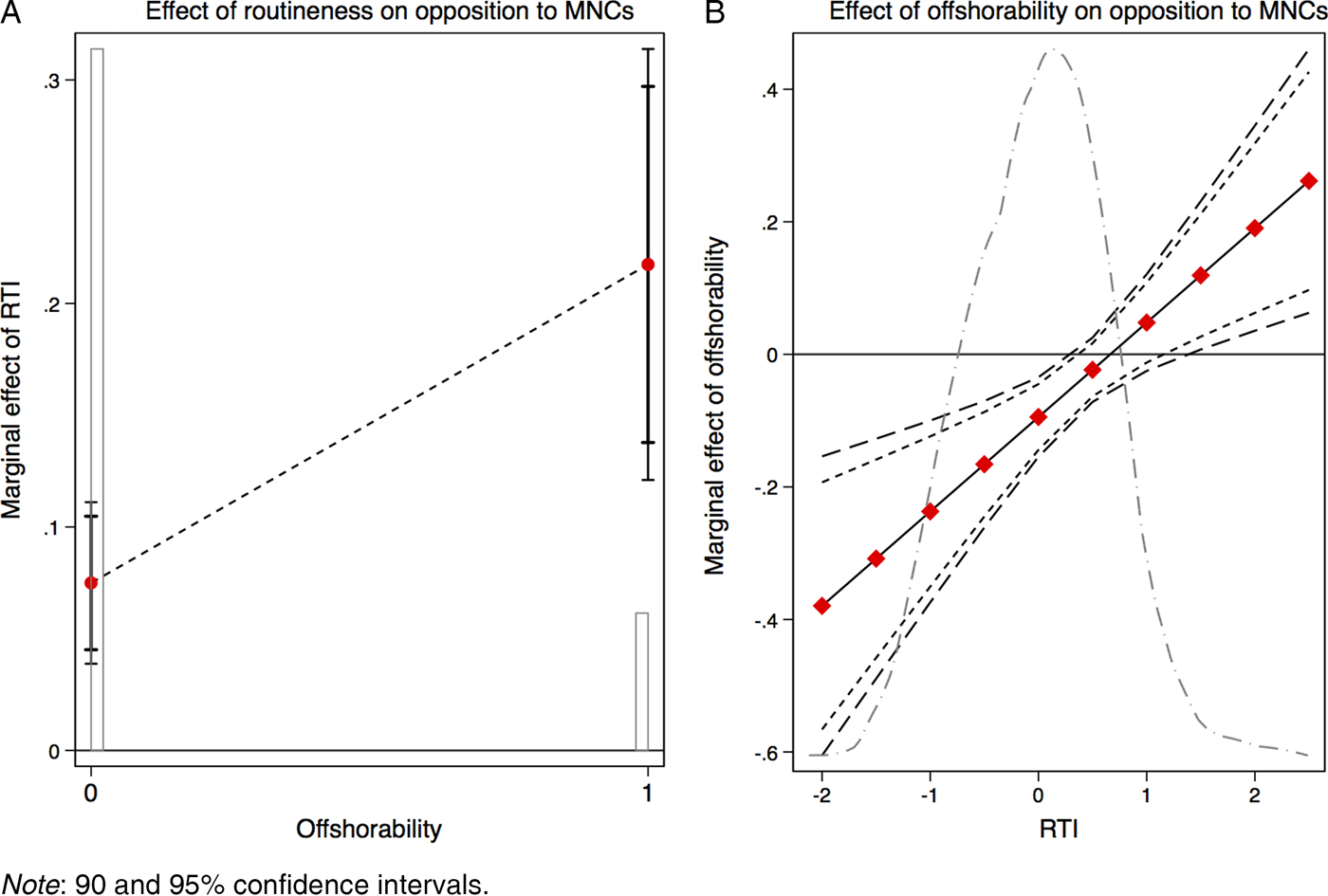

The results are presented in Table 4 and the corresponding marginal effects plots appear in Figures 5 and 6. The results show a similar pattern to those we presented earlier. We again see that an increase in task routineness leads to an increase in protectionist sentiment, particularly among those in offshorable occupations. Similarly, Panel B shows that the marginal effect of offshorability at low levels of task routineness is associated with a decrease in protectionist sentiment, while at high levels of task routineness, the marginal effect is associated with an increase in protectionist sentiment.

Figure 5. Marginal effects plots for Table 4, model 1

Figure 6. Marginal effects plots for Table 4, model 2

Table 4. Opposition to multinational activity

Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. Country fixed effects included. * p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

In Table 5, we return to the original dependent variable and examine the robustness of our findings to alternative measures of routineness and offshorability. First, we utilize an absolute measure of routineness, which is equal to the sum of the cognitive routineness and manual routineness scales. Higher values again indicate greater task routineness.Footnote 117 In Model 1, we again find support for our hypothesis that the effect of routineness is conditional upon occupation offshorability. The marginal effects plots are presented in the online appendix and follow a similar pattern to previous results. In the corresponding results for 2013 (Model 3), the coefficient on the interaction term is not statistically different from 0, but plots of the marginal effectFootnote 118 suggest an interactive relationship similar to that found in previous models.

Table 5. Alternative measures of occupation characteristics

Notes: Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. Country fixed effects included. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Finally, we interact routineness with the measure of offshorability developed by Acemoglu and Autor.Footnote 119 This measure differs from the main measure of offshorability because it is explicitly designed to be orthogonal to routineness. In Models 2 and 4, we again find that the effect of routineness depends upon offshorability. We present the marginal effects in the online appendix. The effect of a one-unit increase in routineness is increasing in the level of offshorability, and leads to an increase in support for protection at medium to high levels of offshorability. An increase in offshorability reduces support for protection at low to medium levels of absolute routineness; at high levels of absolute routineness, an increase in offshorability does not affect support for trade protection.

Finally, we perform a number of additional robustness checks available in the online appendix. First, we report the results of ordered logistic regressions. Second, we examine additional measures of protectionist sentiment. Finally, we examine the interaction between schooling and offshorability.Footnote 120 In all specifications, we continue to find support for our theory that trade preferences are a function of task routineness conditional upon offshorability.

Conclusion

We offer a new theory of trade policy preferences in which the winners and losers of globalization are determined by occupation characteristics. Building on the tasks literature from economics, we argue that trade today produces competitive pressures at the individual level, and thus the welfare consequences of trade are determined by occupation characteristics, rather than only factor ownership or industry exposure to trade. Specifically, we offer a novel theory in which individuals' trade preferences will be driven by the routineness of job tasks, conditional on offshorability. Using survey data from developed countries in 2003 and 2013, we find that as task routineness increases, individuals are more likely to support trade protection and that this effect increases in the level of task offshorability. Among those in nonroutine tasks likely to benefit from trade, an increase in offshorability actually reduces support for trade protection. Together, these findings suggest new patterns of protectionist sentiment that cannot be accounted for by the existing literature. Not only do we find support for our theory in two samples separated by ten years, which suggests that this finding is not fleeting or spurious, but this is also the first paper (to the best of our knowledge) to examine the 2013 ISSP data.

Our findings have several important implications for the politics of trade, and the politics of globalization more generally. First, further research must take into account the conditions under which occupation coalitions are likely to form in lieu of factor- or sector-based coalitions. This article focuses on clarifying an occupation-based theory of trade preferences, but does not integrate the occupation model with the HO and RV models in a larger theoretical framework. Such a framework could predict when one type of trade cleavage will emerge rather than another, depending on factor mobility. It should also consider how different domestic labor-market institutions could influence the nature of cleavages that emerge. Second, future research should examine the implications of these coalitions for the politics of protection, including how the diffuse preferences of labor interests are aggregated to shape policy outcomes. For instance, occupation-based lobbies were not common historically because in the past many individuals would work for the same employer over the course of a career. Today, with individuals likely to change employers multiple times, it is difficult for labor to find a way to organize, especially when peers in the same occupation are spread across many different employers. Thus fragmented production has important implications for labor's ability to influence policy. Third, the findings suggest new sources of protectionist sentiments that politicians must address to maintain sufficient support for continued openness. For instance, aggregate vulnerability to offshoring in congressional districts is found to reduce support for free trade among members of the US House of Representatives.Footnote 121 Last, some aspects of offshoring may not be addressed through trade policy tools, but rather immigration policy, as in the case of passporting financial rights within the EU after Brexit, or through different compensation policies.

Finally, our theory has new implications for the political economy of trade in developing countries. Developing countries, which are relatively labor abundant, will have a comparative advantage in routine tasks. Thus, individuals in routine tasks should benefit from trade in tasks, especially for those in offshorable occupations. However, that is not to say that low-skill individuals in developing countries will benefit from trade. Relatively skilled workers in the developing country may perform routine tasks offshored from the developed country, but the relationship between occupation characteristics and skills has yet to be explored in developing countries. However, new trade theory would suggest that skilled workers in developing countries benefit from trade.Footnote 122 This implies that relatively skilled individuals in routine-task-intensive occupations will benefit from trade. Finally, differences in factor endowments among developing countries become increasingly important when considering the division of labor across global supply chains, and the progress of some developing countries (e.g., China) in climbing the supply chain to provide higher value-added tasks.

Appendix

Data

Table 6. Sample country composition

Table 7. Summary statistics

Explanatory power

In Figure 7, “factor” refers to years of schooling, “industry” refers to the logs of comparative advantage and disadvantage, “occupation” refers to routineness, offshorability and their interaction, and “combined offshorability” includes all of these plus an interaction between years of schooling and offshorability.Footnote 123 For a full discussion of this figure, see the online appendix.

Figure 7. BIC for different specifications in 2003 and 2013

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818317000339>.