Background

The demand for the palliative care service in Australia, like many countries in the world, is increasingly growing (AIHW, 2016, 2019). A rapidly aging population, along with increases in chronic progressive diseases and the increase in the prevalence of cancer, has been attributed as significant drivers (WHO, 2014; Palliative Care Outcome Collaboration, 2018; AIHW, 2019).

The World Health Assembly 2014 resolution called on all member states to strengthen palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course and ensure that palliative care is a fundamental component of universal health coverage (WHA, 2014). Australia is recognized as a world leader in the provision of palliative care. Australian ranked overall second in the world in a review of 80 countries on the quality of palliative care by The Economist Intelligence Unit (2015), with indicators for human resources and affordability ranked as first in the world.

Moreover, Australia has had a strong national policy agenda with a National Palliative Care Strategy since 2000. This was supported by multiple activities and initiatives at the state and territory government levels who have supported a strong palliative care agenda in Australia (DoH, 2018a, 2018b; AIHW, 2019). The policy, practice, and research nexus as a driver for strengthening and improving palliative care is recognized as a key goal in the National Palliative Care Strategy (2018). Funding for palliative care research in Australia has been sporadic at the national, state, and territory government level due to other competing priorities and changes in government directions. This resulted in less palliative care research to be undertaken by researchers than in other research areas.

Furthermore, palliative care research has not been a priority in Australia and this has been further complicated by a lack of the comprehensive palliative care database in Australia (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2012; Productivity Commission, 2017). The AIHW argues that “better palliative care data will assist policymakers, palliative care providers, researchers and the general public to better understand the amount and nature of palliative care activity in the Australian healthcare sector.”

Nevertheless, the provision of palliative care services and innovative programs and projects in Australia has been gradually expanding due to the Australian government's commitment to improve the lives of palliative care patients over the last few years (PCA, 2018b; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2011). This has led to the development of two major initiatives in the form of informative booklets to provide additional information relating to navigating palliative care research through a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and evaluating palliative care projects, programs, and services in 2004. The resources not only were beneficial to the National Palliative Care Program but also for the broader research community conducting research in palliative care (Lee and Kristjanson, Reference Lee and Kristjanson2003; Eagar et al., Reference Eagar, Watters and Currow2010).

The HREC and palliative care research resource provided guidance for any researchers in Australia undertaking ethical palliative care projects that are consistent with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines (Masso et al., Reference Masso, Dodds and Fildes2004). The second initiative is intended to provide guidance to the methods and tools that are available to evaluate palliative care projects, programs, and services in Australia (Eagar et al., Reference Eagar, Cranny and Fildes2004). Since the introduction of these resources, palliative care research has been steadily increasing (Payne and Turner, Reference Payne and Turner2008; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Dodd and Tattersall2017). To date, research into palliative care in Australia has been undertaken by researchers, clinicians, service providers, and others into various facets of palliative care. Mapping the research undertaken thus far in Australia has the potential to identify strengths and gaps in this increasingly important area of research.

Nationwide reviews of palliative care research have been undertaken previously in Ireland, Scotland, and Sweden. These reviews covered an extended period of times of up to 15 years and their objectives were to identify key themes of palliative care research undertaken in the respective countries in order to set priorities for the future. Research priorities related to models of palliative care provision, symptom control, spiritual issues, and education were all common across these reviews (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Nimmo and Baughan2006; McIlfatrick and Murphy, Reference McIlfatrick and Murphy2013; Henoch et al., Reference Henoch, Carlander and Holm2016; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018).

In Australia, a preliminary search of the literature found no reviews addressing a similar topic. Undertaking a similar scoping review in Australia is very timely given the implementation of voluntary assisted dying (VAD) legislation in Victoria (Beardsley et al., Reference Beardsley, Brown and Sandroussi2018). This review will inform researchers of the current palliative care research undertaken in Australia in order to identify gaps and set priorities. It will provide valuable information for targeting future interventions in order to improve the quality of life for palliative care patients.

Aim

A scoping review was undertaken to identify all Australian palliative care research published between January 2000 and December 2018 and to map this research into broad thematic areas. The following research questions were explored:

1. How many Australian research papers were published between January 2000 and December 2018 and how do the annual numbers vary over this period?

2. What were the research areas of focus for palliative care in Australia?

3. What types of studies were undertaken, what designs were used, and what are the characteristics of the study populations?

4. What are the gaps and areas of need in the current research?

Inclusion criteria

The methodology of this current scoping review is based on published scoping review methodologies by Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Peters, Godfrey, McInerney and Soares2016) and Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Godfrey and Khalil2015). This review included research with participants of any age and any condition using palliative care services. The concepts of interest were the number of papers published every year, the areas of palliative care research undertaken in Australia, the type of research, and strengths and gaps in the research. The context of the review was any health care settings including primary care and tertiary settings that include inpatients, outpatients, community-based care, and home-based care. This scoping review included quantitative study designs including experimental, descriptive, and observational studies. Qualitative studies were also included in this review. Only data published in English were considered for the review. No gray literature was searched, as we were interested in studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals based on scientific methods that use evidence to develop conclusions.

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy was utilized in this review. An initial limited search of Ovid MEDLINE, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was undertaken to examine the text words contained in the title and abstract and of the index terms used to describe the article. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was undertaken across all included databases. Thirdly, reference lists of identified articles or reports were manually searched for additional studies and information as mentioned by Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Peters, Godfrey, McInerney and Soares2016) and Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Godfrey and Khalil2015).

Information sources

The following databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL plus, and PsycINFO. The search terms will consist of a combination of search terms relevant to palliative care in conjunction with search terms relevant to the Australian context. These included palliative, terminal, hospice, dying, end of life, last year of life, bereavement, place of death, supportive care, advance care planning, dementia, as well as end stage in combination with cancer, heart, kidney, liver, or lungs. To identify research conducted in Australia, search terms included Australia or Australian. Search terms included MeSH terms and keywords as appropriate on the database searched (Table 1).

Table 1. Data extraction results

To supplement the systematic search, publication lists of well-established palliative care researchers based in Australia were examined and researchers involved were contacted to highlight any potential eligible publications for the review.

Data extraction

Relevant data were extracted from the included studies to address the review question. The methodology outlined by Peters et al. was used. The data extracted will include the following: types of studies undertaken (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and/or reviews), population studied (adults, children, carers, and health care professionals), and areas of focus (cancer, non-cancer, and other conditions). In order to categorize the research themes, a set of themes were identified from previous research studies; these included symptom management (physical/psychological), assessment, services and settings, bereavement, communication and education, coordination of care, carers, quality of life, rural, and urban.

Mapping the results

The extracted data are presented in the tables to reflect the descriptive summary of the results that aligns with the objective and question of the scoping review.

Results

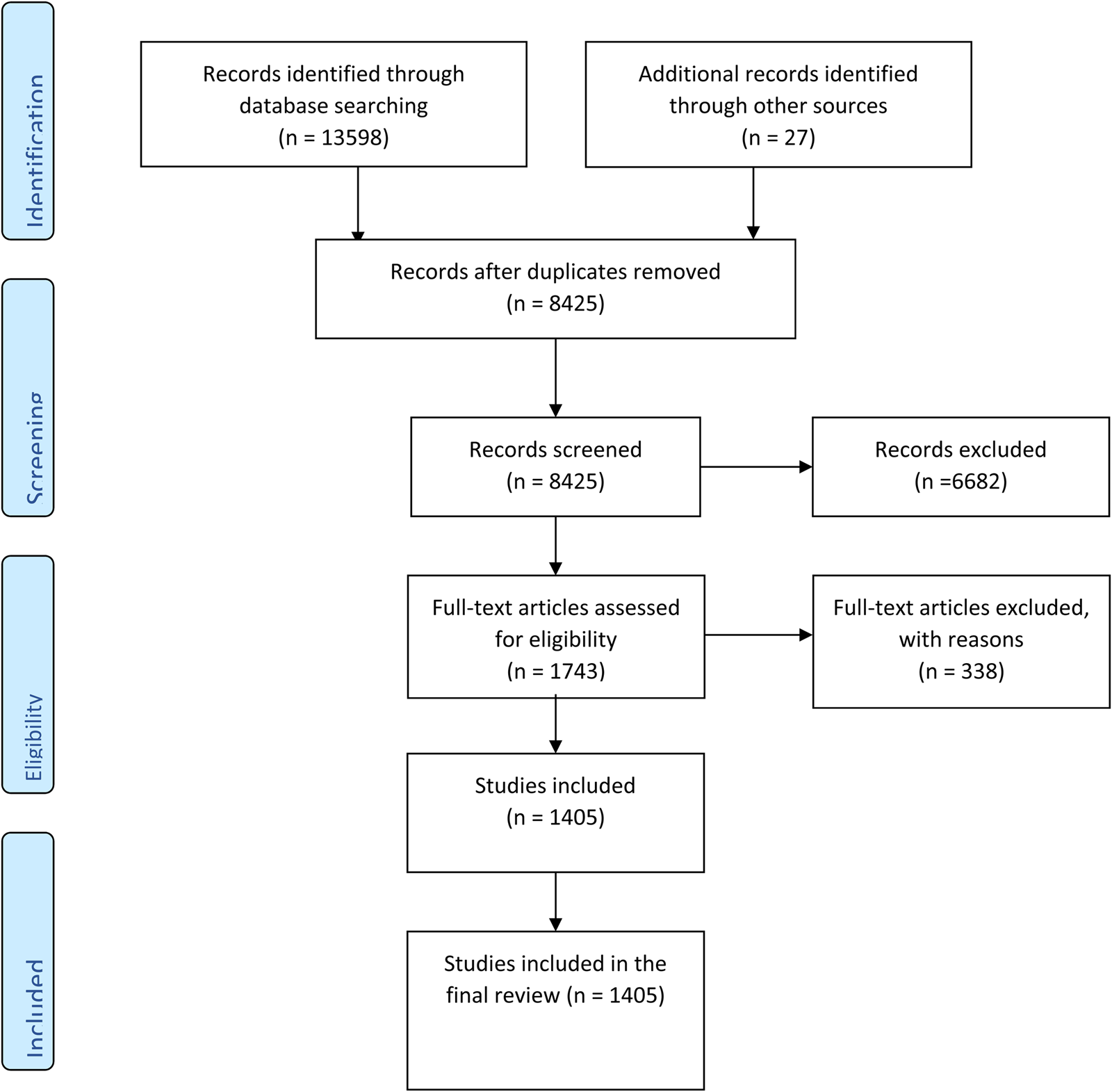

The electronic search of databases identified 13,598 records. An additional 27 records were identified through other sources. All records were entered into Endnote X8 where duplicates were removed resulting in 8,425 citations. These records were then screened by two members of the research team and other 6,682 records were excluded. A total of 1,743 full-text articles were assessed for scoping review eligibility. Of these, another 338 articles were excluded because: (i) not research (n = 140), (ii) not an Australian study (n = 22), and (iii) not focused on palliative care (n = 176). In all, 1,405 articles were included in the scoping review. The search decision process (PRISMA chart) is summarized in Figure 1. A list of all the included studies is detailed in the Supplementary Material.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart summarizing the search strategy (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009).

In the next stage of the review, the extraction of the data and results from the included studies were summarized in alignment with the aims of the study and the four research questions. This extraction process adhered to the methodology for conducting scoping reviews described by Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Godfrey and Khalil2015) and Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Peters, Godfrey, McInerney and Soares2016). We then categorized these results into five broad parameters, as shown in Table 1.

Number of Australian palliative care research publications (2000–2018)

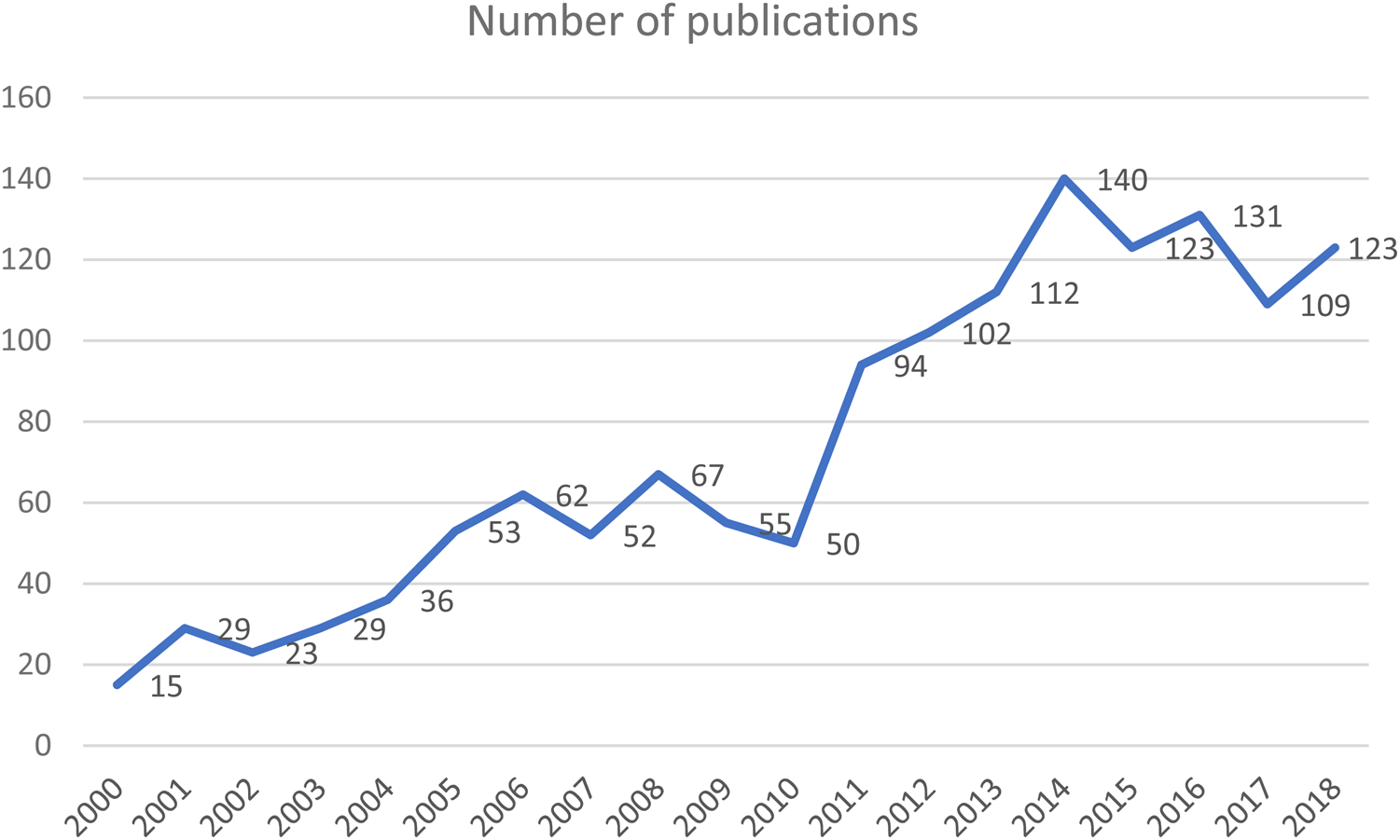

Our review identified 1,405 Australian palliative care research publications between January 2000 and December 2018. From only 15 published articles in 2000 to 123 articles in 2018, the publishing trend over these years was an upward one (Figure 2). This rise was steady from 2000 to 2006 after which the number of articles fluctuated for 4 years until 2010 when only 50 were published. However, from 2010 to 2014, there was a significant increase in publications. In 2011, the number of publications, 94 articles, was nearly double the number published in 2010. In 2014, the most productive year in the scoping review period, 140 palliative care research articles appeared. From 2014 until the end of the review period, there was a slight overall decline, from 140 to 123, in the total of published articles.

Fig. 2. Australian palliative care research publications (2000–2018).

Types of studies

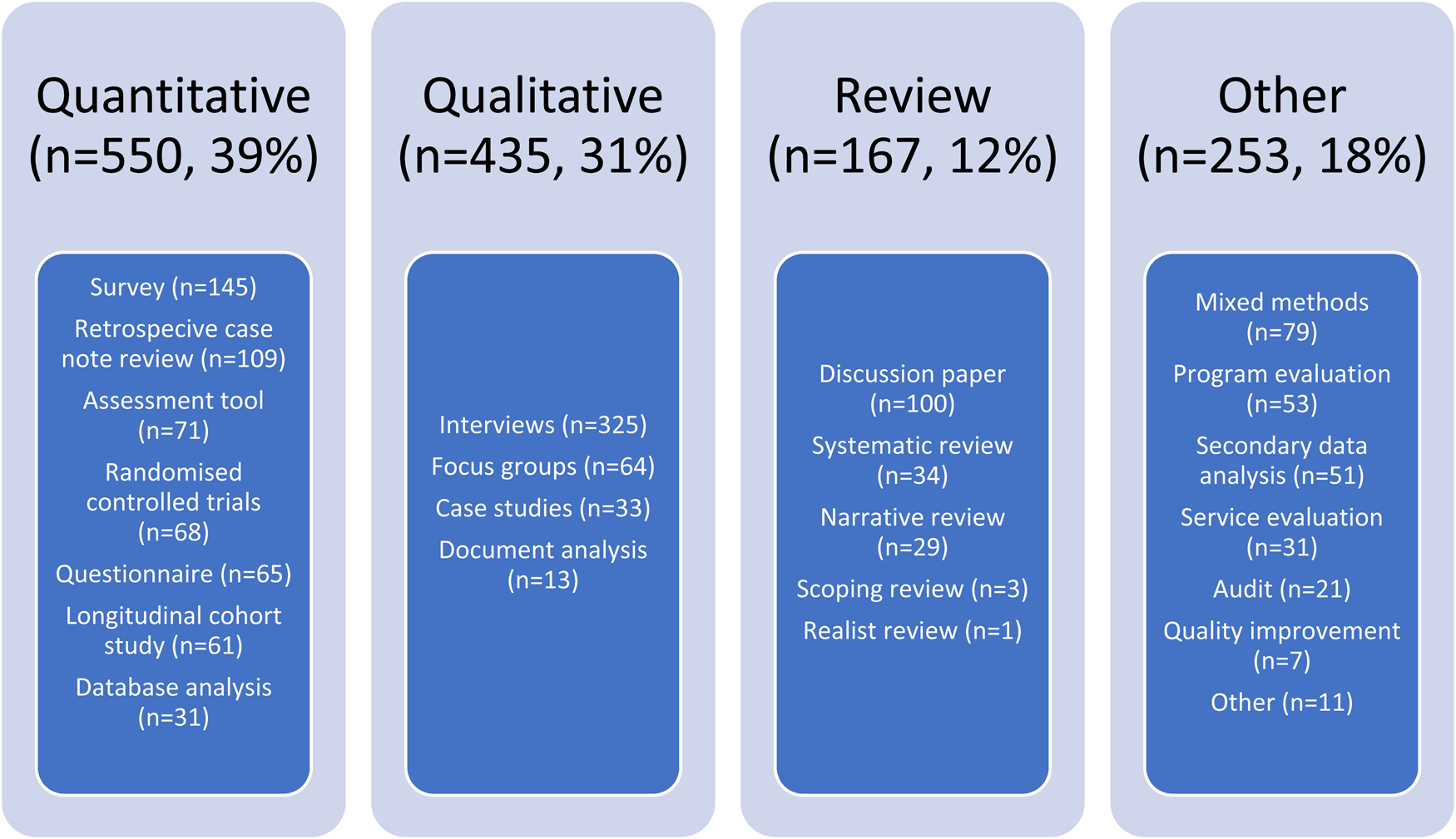

Nearly 40% of the studies were quantitative (39%) and a third were qualitative studies (31%). The remainder of the studies were reviews, mixed methods, quality improvement projects, and others. Quantitative studies included randomized controlled studies, cohort studies, surveys, questionnaires, and case note reviews. Qualitative studies included interviews, focus groups, and document analysis, as shown in Figure 3. When we examined the types of studies by a method, interviews emerged as the most frequent method used (23.2%, n = 325). Clinical studies such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were less than 5% of the methods used (refer Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Methods reported in Australian palliative care research publications.

Study populations

One-third (30%) of the research was done with carers' participants followed by nurses (22%) and doctors and physicians (18%). Adult patients were included in 15% of the studies. Few studies included children and Aboriginal patients, as shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4. Participants in Australian palliative care research studies (2000–2018).

Areas of focus

Figure 5 shows that 38% (530 articles) of studies did not specify the diagnosis of the cohort under investigation. The most frequently reported diagnosis in the studies was cancer with 42% (585 articles) of the publication total. Only 8% (108 articles) of the studies reported a diagnosis other than cancer (e.g., motor neuron disease, dementia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and 12% (177 articles) reported a diagnosis of end-stage conditions (renal, hepatic, and heart)

Fig. 5. Areas of focus in Australian palliative care research studies (2000–2018).

Research themes

The most frequently explored theme was physical symptoms (such as pain, breathlessness, nausea, delirium, and dyspnea) with a total of 16% of all articles followed by communication (16%). There was a large gap to the next most frequently explored theme, service delivery (9%), and coordination of care (9%). Assessment of patients (7%), end-of-life decision-making (7%), and rural/regional (7%) all produced a similar number of publications. Very few studies addressed topics such as anticipatory medications, dementia, quality of life, E-Health, after-hours care, end-of-life care, spirituality, and health economics, as shown in Figure 6.

Fig. 6. Palliative care research themes in Australian studies (2000–2018).

Discussion

This review revealed a significant increase in palliative care research in Australia over the last 18 years. The results obtained were compared with similar studies undertaken in Europe and Africa (Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Garralda and Torrado2017; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Gardiner and Barnes2018; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018; McIlfatrick et al., Reference McIlfatrick, Muldrew and Hasson2018). The number of palliative care publications reported in Australia is almost five times more than those reported by the study undertaken in Scotland, three times more than those reported by African countries, and 10 times more than those undertaken in Ireland. A similar increase in the number of publications of palliative care research was reported by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Gardiner and Barnes2018). The authors in the latter review examined the patterns of international palliative care research in the global context. They reported palliative care to be a growing area of research with increasing numbers of studies reported each year (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Gardiner and Barnes2018).

Our study reported a sharp increase between 2010 and 2014. This coincided with the release of the Grattan report “Dying well” that outlined how end-of-life care could be improved for palliative care patients and released recommendations to increase government funding in this important area of research (Swerissen and Duckett, Reference Swerissen and Duckett2014; Duckett, Reference Duckett2018). The authors of the report issued a set of recommendations, addressing six funding models to address the diversity of patients presented in the varied health services setting and their needs in Australia.

In our review, there was slightly more quantitative than qualitative studies reported followed by systematic reviews. This reflects the breadth of research undertaken in Australia and the importance of both interpreting the available quantitative data routinely collected by clinicians and seeking to understand the experience, needs, attitudes of those involved in the provision, and receipt of palliative care. This finding is also consistent with other reviews (Henoch et al., Reference Henoch, Carlander and Holm2016; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Garralda and Torrado2017; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Gardiner and Barnes2018; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018; McIlfatrick et al., Reference McIlfatrick, Muldrew and Hasson2018). The percentage reported of reviews in Australia (12%) was similar to those reported in Scotland and Ireland (14%) but significantly higher than those reported in Ireland (4.5%) and Sweden (4%) (Henoch et al., Reference Henoch, Carlander and Holm2016; McIlfatrick and Murphy, Reference McIlfatrick and Murphy2013). Surveys were found to be the most popular tool used in the quantitative studies and RCTs represented less than 5% of all studies. This is not surprising given the cost of running RCTs and the ethical issue surrounding these types of studies (Khalil and Ristevski, Reference Khalil and Ristevski2018). Other similar reviews reported a significantly lower proportion of RCTs (3.5%) in Ireland (McIlfatrick and Murphy, Reference McIlfatrick and Murphy2013).

The majority of the included populations in this review was reported by carers (30%) and nurses (22%) followed by doctors (18%). Adult patients (15%), children (7%), and Aboriginal patients (5%) were less represented than health professionals. This is significantly different from other studies; for example, in Scotland, patients were the largest group of the study population (41%) as opposed to health care professionals (McIlfatrick and Murphy, Reference McIlfatrick and Murphy2013). Similar numbers of children were represented in both the Scottish study and our review (Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018). The vast numbers of research focussing on palliative care providers (nurses and doctors) could be explained by the difficulty in recruiting palliative care patients due to the progression of their conditions (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Rogers and Barclay2004; Wohleber et al., Reference Wohleber, McKitrick and Davis2012).

The increase in the research output focussing on health care professionals in Australia could be the result of the recent Australian government initiatives to improve the quality of care in palliative care settings (Sladek and Tieman, Reference Sladek and Tieman2008; PCA, 2018a; PCOC, 2018). The available funding facilitated further research to be undertaken by health care providers (Sladek and Tieman, Reference Sladek and Tieman2008; PCA, 2018a; PCOC, 2018).

The area of focus found in our review was cancer (42%), which is reflective of the main disease group in which palliative care is provided in Australia (AIHW, 2016, 2019). This number is higher than what was reported in the Scottish review (29%) and the World Health Organization (Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018; Cheong et al., Reference Cheong, Mohan and Warren2019). Nevertheless, this is consistent with the figures reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics regarding cancer to be one of the leading causes of death in Australia (ABS, 2018). The proportion of studies addressing non-cancer patients (8%) in this review is lower than other studies reported in Scotland (13%) (Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018). Nonmalignant cancer was also lower in our review than those reported elsewhere in general. Provision of palliative care to end-stage conditions was reported in 12% of the studies included in our review. Patients with dementia were only reported in 30 studies (2%). This result is consistent with another review by Finucane et al. (Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018). The authors explained that the few numbers of studies including these patients are possibly due to practical and ethical issues. However, it is expected that there will be increasing numbers of this population over the years due to the growing aging population in Australia.

The largest research themes in the Australian literature were found to address physical and psychological symptoms followed by service provider evaluation in the form of coordination of services, staff education, and decision-making. Very few studies addressed the end of life, cost–benefit analysis of current models, spiritual needs, after-hours access, medications, E-health, and economics. There were also small representations for populations such as children, aboriginal and regional and rural communities. This pattern is also consistent with those reported by other reviews (Henoch et al., Reference Henoch, Carlander and Holm2016; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Carduff and Lugton2018).

Palliative care patients require medications to address their physical symptoms, and it was interesting to note that only a small proportion (4%) of all studies addressed medications. Only five studies addressed anticipatory medications (Salins and Jansen, Reference Salins and Jansen2011; Olson, Reference Olson2014; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Butow and Tong2016; Tan and Cheang, Reference Tan and Cheang2016; Dredge et al., Reference Dredge, Oates and Gregory2017). These medications are essential to palliative care patients particularly toward their end of life. Recent research suggests that there is confusion and lack of knowledge by nurses and doctors on issues associated with these medications and targeted interventions addressing those challenges are urgently needed (Khalil et al., Reference Khalil, Poon and Byrne2019).

The gaps identified in this research are a reflection of the difficulty in recruiting those vulnerable populations (Khalil and Ristevski, Reference Khalil and Ristevski2018). E-health and health economics are growing fields across many topics and the small numbers represented in this review are evident of the need for researchers to undertake studies in these areas. Research into after-hours care could be facilitated by projects linking data from multiple sources such as hospital admissions and general practitioners’ visits. Data linkage in this field has the potential to provide valuable information about which services are accessed by these patients and the quality of care provided to them (Brettell et al., Reference Brettell, Fisher and Hunt2019; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Engelberg and Woo2019).

Some studies had a multifaceted approach including both health care professionals and patients and overlapping in their areas of focus, particularly longitudinal studies and studies reporting the secondary data analysis. This finding is consistent with the current trend of using the existing large database to scope the needs of various populations and identify gaps in research in existent areas of practice.

In an increasing effort to address the health disparities for this group of patients, the Australian government has established several initiatives such as Caresearch and the National Palliative Care Strategy. Caresearch is funded by the Australian Government under the 2017–2020 National Palliative care program. The project aims to provide a wide variety of evidence-based resources for all Australians. In addition to this project, the National Palliative Care Strategy involved detailed consultation with multiple stakeholders across Australia to set priorities to improve palliative care for all Australians (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Tieman and Damarell2018).

Another recent initiative is the establishment of the Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) program. This is a national program for palliative care services to routinely measure and benchmark patient outcomes. The PCOC database includes information of more than 250,000 palliative care Australians. The tool is currently used by health care professionals in many health care settings to improve the quality of care of palliative care patients (Currow et al., Reference Currow, Allingham and Yates2015; PCOC, 2018).

Palliative care is becoming a significant research priority given the latest Victorian's state government decision to legalize VAD (Beardsley et al., Reference Beardsley, Brown and Sandroussi2018). This resulted in Palliative Care Australia developing guidelines for those providing care to people living with a life-limiting illness (PCA, 2018a). Further research in this area is warranted to support palliative care patients at the end of their lives.

This review has a few limitations; it has only covered peer-reviewed literature and has omitted resources such as dissertations, government reports, and other non-peer-reviewed literature which may have added further insights into the available literature. Furthermore, due to the type of methodology employed, the review lacked any appraisal of the included studies. Future studies should also focus on the effectiveness of the interventions and models of care described in the included studies on patients’ care to ensure appropriate care for palliative care patients.

Conclusion

The current review presented a comprehensive search of the literature across almost two decades in Australia in the palliative care setting. It has covered a breadth of research topics and highlighted urgent areas for further research such as anticipatory medications, dementia, quality of life, E-Health, after-hours care, end-of-life care, spirituality, and health economics. Furthermore, populations such as children, indigenous people, and rural and remote communities were found to be underrepresented in the Australian research literature and need further attention.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519001111.

Acknowledgment

H.K. thank Fiona McCook for her initial work on the manuscript.

Appendix 1. Search strategy