The coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic has created an unprecedented need for web-based mental health resources and has been coined a ‘turning point for e-health’ (Wind, Rijkeboer, Andersson, & Riper, Reference Wind, Rijkeboer, Andersson and Riper2020). In addition to telehealth, i.e. interventions delivered by a health professional remotely via technology, standalone online interventions are increasingly available for a wide range of mental health conditions, such as depression (Andersson & Cuijpers, Reference Andersson and Cuijpers2009), anxiety (Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, Reference Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy and Titov2010; Pennant et al., Reference Pennant, Loucas, Whittington, Creswell, Fonagy, Fuggle and Expert Advisory2015), and eating disorders (Aardoom, Dingemans, Spinhoven, & Van Furth, Reference Aardoom, Dingemans, Spinhoven and Van Furth2013). The efficacy of these interventions has been demonstrated in many randomised controlled trials and is largely comparable to that of traditional face-to-face interventions (Olthuis, Watt, Bailey, Hayden, & Stewart, Reference Olthuis, Watt, Bailey, Hayden and Stewart2016). In addition, web-based interventions have been shown to be more cost-effective when compared to traditional therapy (Musiat & Tarrier, Reference Musiat and Tarrier2014).

Intervention adherence is key to the mechanism of action in psychological interventions in that for any treatment to produce an effect, it is required that the client receives a sufficient ‘dose’. As such, it is unsurprising that adherence to traditional mental health interventions, such as face-to-face therapy, is positively associated with intervention outcomes (Killaspy, Banerjee, King, & Lloyd, Reference Killaspy, Banerjee, King and Lloyd2000). Whereas the focus of adherence research in these traditional interventions has been on the completion of activities between intervention sessions (Simpson, Marcus, Zuckoff, Franklin, & Foa, Reference Simpson, Marcus, Zuckoff, Franklin and Foa2012) or on the adherence of therapists to treatment procedures (Webb, Derubeis, & Barber, Reference Webb, Derubeis and Barber2010), adherence in the context of web-based interventions relates to accessing and completing the online content. It has frequently been suggested that adherence to computerised mental health interventions is inherently low (Eysenbach, Reference Eysenbach2005). However, the setting and design of trials appear to be an important factor for intervention adherence. While open trials often are associated with poor intervention uptake and adherence (Farvolden, Denisoff, Selby, Bagby, & Rudy, Reference Farvolden, Denisoff, Selby, Bagby and Rudy2005; Lillevoll, Vangberg, Griffiths, Waterloo, & Eisemann, Reference Lillevoll, Vangberg, Griffiths, Waterloo and Eisemann2014), systematic reviews and meta-analyses of web-based interventions within controlled trials and with individuals at clinical severity have shown that treatment completion rates range between 50% and 90% (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy and Titov2010; Christensen, Griffiths, & Farrer, Reference Christensen, Griffiths and Farrer2009) and thus compare to completion rates achieved in face-to-face psychotherapy studies (Swift & Greenberg, Reference Swift and Greenberg2012).

A frequently used approach to improve the efficacy of web-based mental health interventions is the provision of guidance. While it has been suggested that guidance increases intervention efficacy by means of increasing intervention adherence (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Buntrock, Lehr, Smit, Riper, Baumeister and Berking2018), there is little evidence on the impact of the guidance on intervention adherence in computerised mental health interventions. To date, four systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide indicative evidence on the relationship between human guidance and intervention adherence. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Baumeister, Reichler, Munzinger, and Lin (Reference Baumeister, Reichler, Munzinger and Lin2014) investigated whether guidance improves adherence and efficacy in web-based mental health interventions. The authors found guided interventions to result in lower symptom severity and increased adherence with regard to the number of completed modules and intervention completers. Similar results were found in a more recent meta-analysis limited to anxiety disorders (Domhardt, Gesslein, von Rezori, & Baumeister, 2019). These studies, however, were limited in scope and as a result, only included a small number of papers. With regard to comparing guided to unguided interventions, Baumeister et al. (Reference Baumeister, Reichler, Munzinger and Lin2014) identified seven studies and Domhardt et al. (Reference Domhardt, Gesslein, von Rezori and Baumeister2019) identified four studies. Another study reviewed predictors of adherence to online psychological interventions for mental and physical health problems. In four studies where quantitative indicators of adherence were reported, guidance was identified as a significant predictor and compared to unguided interventions, adherence was greater in guided interventions (Beatty & Binnion, Reference Beatty and Binnion2016). The studies outlined above have in common that they did not include a clear definition for what constitutes guidance. Thus, forms of guidance which differed considerably in quality, intensity, and the amount of human involvement, such as online forums, telephone coaching, or automated feedback were included and compared. Shim, Mahaffey, Bleidistel, and Gonzalez (Reference Shim, Mahaffey, Bleidistel and Gonzalez2017) addressed this limitation and specifically reviewed the impact of human-support factors in computerised intervention for depression and anxiety. Adherence was operationalised as non-usage attrition and the authors found mixed results regarding the impact of guidance when compared to conditions without guidance. However, despite defining guidance as supplementary care delivered by a human, the authors also include studies with fully automated support, such as email reminders. A shared limitation of these reviews is that none of these studies specifically investigated the link between guidance and adherence. As a result, these studies had more narrow inclusion criteria, which resulted in small numbers of included studies and, for example, may have omitted evidence from studies that only reported adherence data without intervention outcomes. A summary of evidence from existing studies and their limitations is provided in the online Supplementary Material (Table S1). Understanding the association between guidance and intervention adherence is important for understanding how such interventions work and how they can be implemented.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to investigate and quantify the impact of the guidance on adherence to web-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of mental health conditions. To overcome some of the limitations of previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews, this study used a clear definition of what constitutes guidance and included only high quality (randomised controlled) trials. Specifically, the aim of this paper was to test the following two hypotheses: (1) Individuals receiving guidance complete a greater proportion of the intervention compared to those completing an unguided intervention, and (2) compared to unguided delivery, guidance leads to a larger proportion of individuals completing enough intervention content to have received an adequate dose.

Methods

This meta-analysis is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and The PRISMA Group2009). A protocol for this meta-analysis was not published.

Literature search

Three electronic databases (Medline, PsychINFO, and CINAHL) were searched on 16/11/2020 using a range of relevant search terms within title, abstract, or keyword. The complete search terms are provided in the online Supplementary Material. No restrictions regarding the year of publication or study quality were made. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews were included in search terms and separately screened for references of interest for this study, as were references of included studies. To ensure high quality and low heterogeneity of included studies with regard to the quality of research methods and the quality of reporting, grey literature was not searched. Only peer-reviewed and published studies were included.

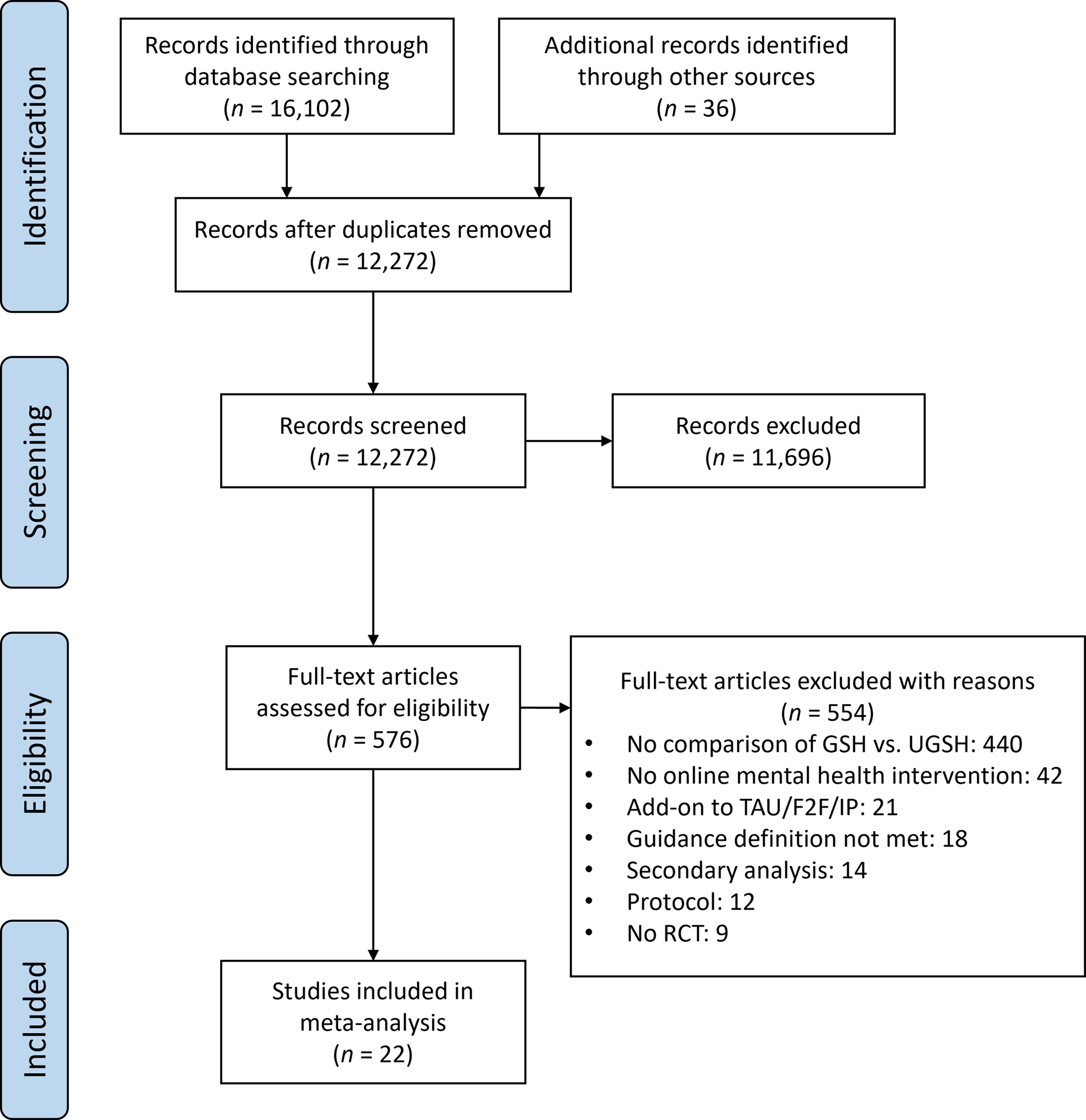

Initial screening of search results by title and abstract was performed by two authors (CJ, PM), full texts were screened by all authors (PM, CJ, MA, SW, TW) with each study being screened by at least two authors. Any disagreement regarding the inclusion of studies was discussed and resolved with a third author. Figure 1 shows the study selection and screening process.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Eligibility criteria

For the purpose of this meta-analysis, guidance was defined as any direct and bidirectional communication with the individual designed to support the clinical aspects of the intervention, facilitate intervention completion and/or achieve the desired clinical outcomes. Guidance must be related to the online intervention content and not constitute a separate standalone intervention, such as motivational interviewing or exposure. No restrictions were applied regarding the mode of delivery of guidance. Thus, communication as part of guidance can be synchronous (e.g. phone call, online chat) or asynchronous (e.g. email, text message). Based on this definition, email reminders, pure technical support, or personalised feedback were not considered intervention guidance. In addition, the support provided to a group of people completing the intervention, such as moderated discussion forums or online group chats were excluded, because it has been demonstrated individuals are more likely to disclose negative emotions to an individual support person than to an online group (Rogers, Griffin, Wykle, & Fitzpatrick, Reference Rogers, Griffin, Wykle and Fitzpatrick2009). Given internet interventions are often designed to replace and are compared to face-to-face interventions, a definition of guidance was chosen that ensures guidance mimics the therapeutic process.

Included peer-reviewed publications were required to (1) be a randomised controlled trial, (2) be published in English, (3) be a standalone psychological prevention or treatment programme targeting a primary mental health condition, (4) be delivered online via a computer or smartphone, (5) experimentally compare at least two intervention groups of which one received intervention guidance as described above, while one group completed the intervention unguided, (6) report rates of intervention adherence for all intervention groups, and (7) include interventions that were structured and consisted of multiple sessions or modules, thereby mimicking face-to-face interventions and in order for adherence outcomes to be meaningful. Based on these criteria, interventions offered in addition to treatment, as usual, face-to-face therapy, or hospital treatments were excluded, as these interventions would confound with intervention guidance. In addition, virtual reality or cognitive bias modification interventions were excluded, because their mechanism of action is assumed to substantially differ from intervention primarily based on second and third-wave treatments, such as cognitive behaviour therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy.

Data extraction

Outcome measures

Two outcome measures are of interest for this meta-analysis. First, a continuous measure describing the degree of intervention content completion across participants in both groups, such as the average number of modules completed. Means and standard deviations reported for this outcome were scaled to 100% based on the total number of intervention modules in each study to ensure that outcomes were comparable across all studies. The second outcome of interest was a dichotomous measure describing the number of individuals in each study who completed the intervention. For studies where authors provided an a priori definition for a sufficient intervention dose (e.g. eight out of ten modules), the outcome was based on the number of individuals completing the defined intervention proportion. For all other studies, the outcome was based on the number of individuals completing the full intervention. All outcomes were extracted for the baseline and post-intervention assessment. These two outcomes were chosen, as they were identified as the two most commonly reported adherence measures in randomised controlled trials of online interventions (Beintner et al., Reference Beintner, Vollert, Zarski, Bolinski, Musiat, Gorlich and Jacobi2019).

Risk of bias in individual studies

The methodological quality of included studies and risk of bias was assessed using the revised Risk of Bias tool (RoB2) developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Savovic, Page, Elbers, Blencowe, Boutron and Higgins2019). The tool assessed risk of bias arising from the (1) randomisation process, (2) effect of assignment to intervention, (3) effect of adhering to intervention, (4) risk of bias from missing outcome data, (5) measurement of the outcome, and (6) from the selection of the reported result. Study quality was assessed by the first author only.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using the meta package included in the STATA 16 software (StataCorp, 2019). To test the first hypothesis, a meta-analysis was conducted aggregating the continuous outcome. Random effects meta-analyses were performed to compute the overall effect size estimate (Hedges's g). It should be noted that within STATA, g is calculated based on the approximation for the unbiased effect size estimator described by Hedges (Reference Hedges1981, p. 114), correcting for small sample bias. To test the second hypothesis, the dichotomous outcome was included in a separate meta-analysis. Log odd's ratios were calculated as indicators of effect size. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all effect sizes at 95%. Where study data did not allow for the calculation of effect sizes, authors were contacted for additional data.

Proportions of intervention completers in the guided and unguided condition across studies were aggregated using the approach described by Nyaga, Arbyn, and Aerts (Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts2014) and with the STATA package metaprop. The used STATA syntax is included in the online Supplementary Material of this paper.

Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Cochran's Q-test (Cochran, Reference Cochran1954), as well as the H and I 2 statistics described by Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, and Altman (Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003). The presence of potential reporting biases was investigated through visual inspection of funnel plots and tests for asymmetry (Higgins, Savović, Page, Elbers, & Sterne, Reference Higgins, Savović, Page, Elbers and Sterne2019). The trim-and-fill (Duval & Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000) method was used to determine the potential number of studies missing due to publication bias and to adjust the aggregated effect size estimator accordingly. For the continuous outcome, funnel plot asymmetry was investigated using Egger's regression test. Due to the susceptibility of this test to type I errors with dichotomous outcomes (Schwarzer, Antes, & Schumacher, Reference Schwarzer, Antes and Schumacher2002), the Harbord (Harbord, Egger, & Sterne, Reference Harbord, Egger and Sterne2006) and Peters tests (Peters, Sutton, Jones, Abrams, & Rushton, Reference Peters, Sutton, Jones, Abrams and Rushton2006) were used for the dichotomous outcome. For most included studies adherence was a secondary outcome but is potentially correlated with the primary (clinical) outcome. Thus, the presence of publication bias was also investigated based on the primary clinical outcome for each study.

Results

Studies

A total of 22 studies published between 2008 and 2019 were identified and included in this meta-analysis. The most common reason for the exclusion of studies was the lack of comparison between guided and unguided intervention arms (Fig. 1). However, for most studies, multiple reasons for exclusion applied. Of the included studies and after contacting authors for missing data n = 19 reported data on the average intervention adherence and n = 21 reported data on the number of individuals completing the full intervention. Characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of 22 included studies

Note: ACT = Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, BD = Bipolar Disorder, CBT = Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, GAD = Generalised Anxiety Disorder, IAD = Illness Anxiety Disorder, MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, NR = Not reported in study, PD = Panic Disorder, SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder, SP = Social Phobia, SSD = Somatic Symptom Disorder.

Participants

The 22 included studies had a total of 5176 participants of which 3946 were included in this meta-analysis, as some studies included intervention arms not relevant to this study. A total of 1967 individuals across studies received unguided interventions and 1979 received guided interventions. The majority of studies recruited participants from community settings, often through advertisements in newspapers or online. Nevertheless, in n = 14 studies individuals were required to meet diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder to be eligible for the study. All but one study (Puolakanaho et al., Reference Puolakanaho, Lappalainen, Lappalainen, Muotka, Hirvonen, Eklund and Kiuru2019) targeted adults, with most participants being between 30 and 50 years of age. One study specifically targeted older adults (Titov et al., Reference Titov, Fogliati, Staples, Gandy, Johnston, Wootton and Dear2016). Females were generally overrepresented in the included studies. The majority of included studies were conducted in Australia (n = 10) or Europe (n = 7).

Interventions

Intervention length ranged from four to 18 modules, with an average of M = 7.00 (s.d. = 3.15) modules across studies. The most commonly targeted disorder was depression with nine studies (41%). Of those studies, three also targeted anxiety symptoms (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Fogliati, Fogliati, Johnson, Boyle, Karin and Titov2018; Kleiboer et al., Reference Kleiboer, Donker, Seekles, van Straten, Riper and Cuijpers2015; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Fogliati, Staples, Gandy, Johnston, Wootton and Dear2016). A total of six studies targeted social phobia (n = 3) or social anxiety disorder (n = 3). A large majority (77%) of the included studies investigated interventions based on cognitive behavioural therapy models and three studies reported interventions based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. All studies delivered intervention content via the internet, however, one study also included supplementary intervention content delivered via smartphone (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Lindner, Ly, Dahlin, Vernmark, Andersson and Carlbring2016). Adherence data for this study was only extracted for the web-based component. In the study by Farrer, Christensen, Griffiths, and Mackinnon (Reference Farrer, Christensen, Griffiths and Mackinnon2011), individuals were offered access to a psychoeducation website prior to access to a web-based CBT intervention. For this study, adherence data were extracted for the latter intervention.

Guidance

With the exception of two studies, participants generally received guidance from a mental health professional and communicated via email or telephone. In most studies, guidance was provided weekly. In the study by Gershkovich, Herbert, Forman, Schumacher, and Fischer (Reference Gershkovich, Herbert, Forman, Schumacher and Fischer2017) participants were contacted via regular video calls and Puolakanaho et al. (Reference Puolakanaho, Lappalainen, Lappalainen, Muotka, Hirvonen, Eklund and Kiuru2019) provided guidance through face-to-face sessions with additional text messages. Proudfoot et al. (Reference Proudfoot, Parker, Manicavasagar, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Whitton, Nicholas and Burckhardt2012) investigated a web-based intervention for individuals with bipolar disorders and provided guidance through individuals with a lived experience of the bipolar disorder instead of a health professional. Overall, guidance in the included studies focused on the provision of feedback on intervention progress and tasks, the provision of encouragement to support individuals in completing the intervention, providing an opportunity for clarification of intervention content, and supporting participants to put newly acquired skills into practice. It should be noted that six studies from Australia used a virtually identical protocol for providing intervention guidance (see Table 1) in their studies (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Staples, Terides, Karin, Zou, Johnston and Titov2015, 2016, 2018; Fogliati et al., Reference Fogliati, Dear, Staples, Terides, Sheehan, Johnston and Titov2016; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Dear, Staples, Terides, Karin, Sheehan and McEvoy2015, Reference Titov, Fogliati, Staples, Gandy, Johnston, Wootton and Dear2016).

Effect of guidance on content completion

There was a statistically significant but small effect of guidance on the average completion of intervention content in web-based mental health interventions with the adherence being greater in the guided condition. The estimate of the average effect size was g = 0.29 (95% CI 0.18–0.40, z = 5.35, p < 0.001), thus providing support for hypothesis 1. Figure 2 shows the forest plot of individual and aggregated study effects with a 95% CI and study weights.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of study effects for average intervention completion in guided and unguided web-based interventions.

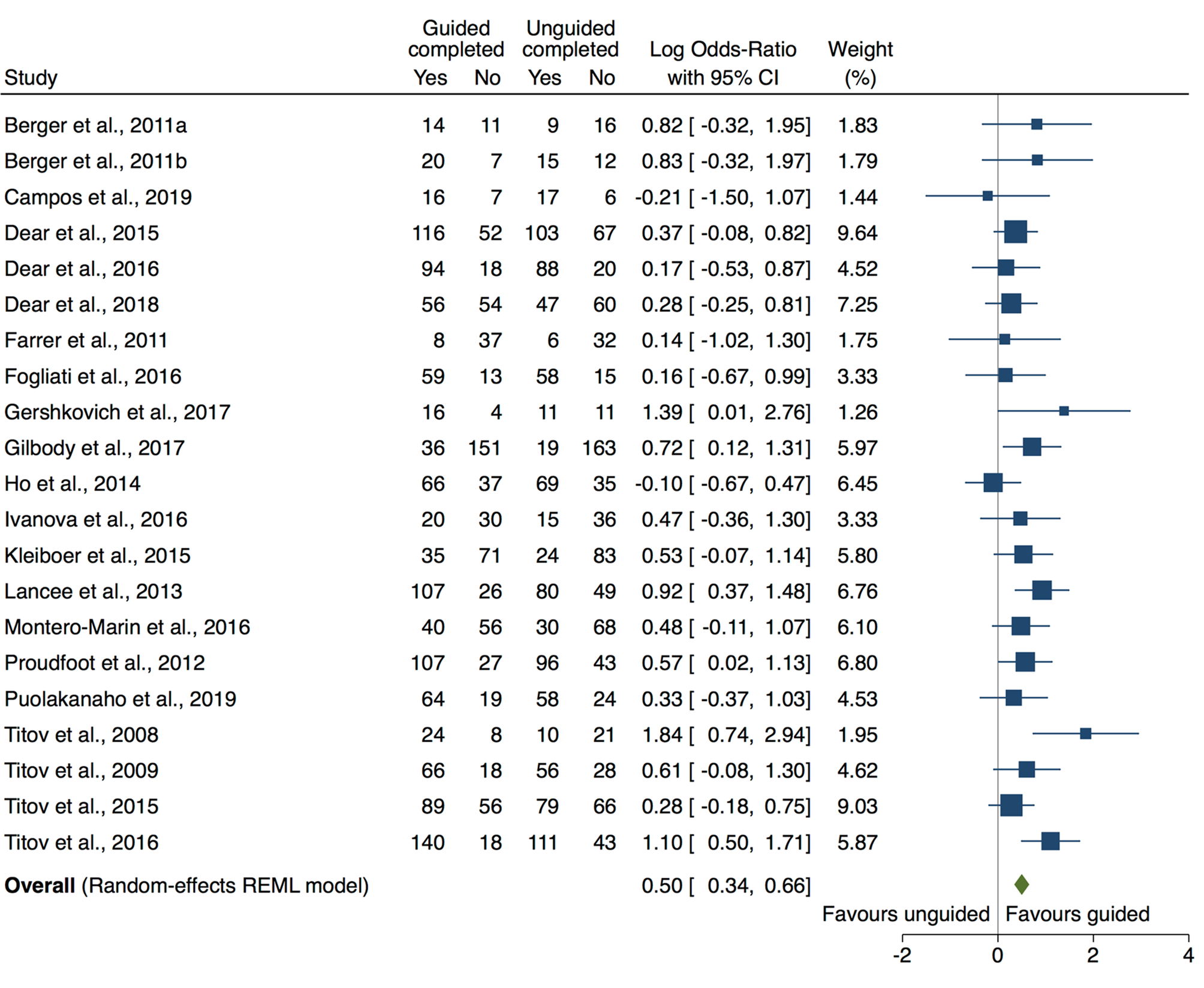

Effect of guidance on completer rates

The meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in full intervention completion rates between unguided and guided intervention groups across studies. The aggregated log odds ratio (OR) was 0.50 (95% CI 0.34–0.66, z = 6.42, p < 0.001), which is equal to an OR of 1.65 (95% CI 1.41–1.93). The aggregated proportion of intervention completers in unguided groups across studies was 0.52 (95% CI 0.41–0.62). In the guided intervention groups that figure was 0.64 across studies (95% CI 0.53–0.74). Figure 3 shows the forest plot of individual and aggregated study effects with a 95% CI and study weights.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of intervention completion rates with 95% CIs.

Heterogeneity

Between the included studies there was considerable heterogeneity regarding the interventions used, guidance formats, and recruitment strategies. With regard to the reported effect sizes the meta-analysis on the average intervention completion rates across studies suggested the presence of heterogeneity (I 2 = 51.81%, H 2 = 2.07, Q(18) = 37.46, p = 0.005). There was no evidence for heterogeneity with regard to the dichotomous outcome of intervention completers (I 2 = 10.43%, H 2 = 1.12, Q(20) = 23.92, p = 0.246).

Risk of bias

The methodological quality of the included studies was generally high. Figure 4 shows a summary of the RoB2 ratings. Most studies had a low risk of bias across all domains. In cases where the risk of bias was higher, sources of risk primarily included missing outcome data and the selection of study results due to the lack of study protocols. Individual risk of bias ratings for each study is shown in online Supplementary Table S2.

Fig. 4. Summary of risk of bias ratings for included studies.

Publication bias

Overall, publication bias was not suggested. Visual inspection of the funnel plot of Hedges' g for module completion against the standard error of the outcome showed no asymmetry (Fig. 5). In addition, the regression-based Egger test for small-study effects was statistically not significant (z = 1.22, p = 0.223). The estimated average of intervention completion rates did not change when adjusted for publication bias using the trim and fill procedure. Visual inspection of the funnel plot of the log ORs plotted against the standard error of the outcome did not suggest the presence of publication bias. This assessment is supported by the high p values obtained in the Harbord (z = 0.75, p = 0.452) and Peters tests (z = 0.97, p = 0.330). Similar to the continuous outcome, the trim and fill procedure did not impute any missing studies or adjust the aggregated effect size. Publication bias was investigated for the primary clinical outcome of each study. Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested no asymmetry, which was confirmed in a statistically non-significant Egger test (z = 0.10, p = 0.923). In addition, the trim and fill method imputed no additional studies.

Fig. 5. Funnel plots for average intervention completion, intervention completer rates, and clinical outcomes.

Discussion

This meta-analysis examined the impact of guidance in web-based intervention for mental disorders on two indicators of intervention adherence. Consistent with our hypotheses, results suggested that guidance increases both the average proportion of intervention content completed by participants, as well as the number of individuals who complete the entire intervention. It is likely that the effect of adherence on average intervention completion can at least be partially explained by the increased number of individuals completing the full intervention, i.e. as more individuals complete the full intervention the average number of completed modules increases.

On average, the proportion of individuals completing the full intervention was 64% in the guided condition compared to 52% in the unguided condition across the included studies. This figure is in line with overall completion rates, irrespective of guidance, of previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy and Titov2010; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Griffiths and Farrer2009). The fact that most of the included studies in this meta-analysis recruited individuals who met the criteria for mental disorders may have contributed to this relatively high level of adherence. It could be considered that these individuals are highly motivated to improve their symptoms, lack access to traditional care or simply prefer the web-based mode of delivery, which in turn increases adherence (Christensen & Mackinnon, Reference Christensen and Mackinnon2006). However, the effects on both outcomes were small. On average, guidance increased the proportion of individuals completing the entire intervention content by only 12%. This highlights that the provision of guidance in web-based interventions should be carefully considered from a cost-effectiveness perspective. The benefits of providing guidance and thus more individuals completing the intervention have to outweigh the associated costs. Whereas unguided interventions can easily be scaled up and reach a large number of people, the provision of guidance requires personnel, infrastructure and safety procedures. There may be settings, however, in which the provision of guidance is not possible or practical, but where intervention completer rates of one in two clients are acceptable, such as stepped-care treatment models. In light of the fact that the included studies primarily used clinically more severe samples, it should also be considered whether guidance potentially has a more pronounced effect on completer rates in individuals with less severe psychopathology.

There is mixed evidence as to whether guided web-based mental health interventions are more effective than unguided interventions. Recent meta-analyses (e.g. Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Cuijpers, Ebert, McKenzie Smith, Coughtrey, Heyman and Shafran2019; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Rodriguez, Qian, Kishimoto, Lin and Berger2020; Pauley, Cuijpers, Papola, Miguel, & Karyotaki, Reference Pauley, Cuijpers, Papola, Miguel and Karyotaki2021) found no differences between guided and unguided computerised interventions and the results from this meta-analysis may provide some explanation for these findings. If adherence is only marginally better in guided interventions, this may not be sufficient to produce superior clinical outcomes. Other studies, however, have investigated the effect of guidance on intervention adherence and efficacy, and have found guidance to increase both (Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Reichler, Munzinger and Lin2014; Domhardt et al., Reference Domhardt, Gesslein, von Rezori and Baumeister2019). It has to be noted that based on the results from these studies it is not possible to determine whether it was increased adherence that lead to greater efficacy or whether individuals simply stop using an online intervention when their symptoms do not improve. Thus, a minimum amount of intervention adherence is essential but not sufficient for the efficacy of an intervention. Understanding the relationship between guidance, adherence and efficacy may contribute to the development and delivery of these interventions at scale and thus future research should further investigate this domain (Donkin et al., Reference Donkin, Christensen, Naismith, Neal, Hickie and Glozier2011). In addition to meta-analyses, this may also involve reanalysing data on an individual level.

The postulated correlation between intervention adherence and efficacy raises two important directions for research. First, if guidance merely increases efficacy by increasing adherence, other measures for increasing adherence, such as rewards or gamification strategies (e.g. virtual badges and achievements, scores, leader boards) could be considered.

A significant contribution to this question was made in a systematic review by Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard, and Van Gemert-Pijnen (Reference Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard and Van Gemert-Pijnen2012), who demonstrated that the inclusion of persuasive design principles, including reminders, self-monitoring, or tailoring, explained a considerable proportion (55%) of variance in adherence rates between studies. Nevertheless, the results need to be interpreted with caution as the considered design principles also included elements of human guidance. In another study by the same authors, human support was compared to fully automated support. No differences with regard to adherence were found, but individuals receiving human support reported better clinical outcomes than those receiving automated support (Kelders, Bohlmeijer, Pots, & van Gemert-Pijnen, Reference Kleiboer, Donker, Seekles, van Straten, Riper and Cuijpers2015).

The second direction for research relates to the most cost-effective ways of providing human intervention guidance and there is emerging literature in this area. For example, several studies excluded from this meta-analysis investigated guidance at different intensity levels and found no differences between the groups with regard to clinical outcomes (Aardoom et al., Reference Aardoom, Dingemans, Spinhoven, van Ginkel, de Rooij and van Furth2016; Alfonsson, Olsson, & Hursti, Reference Alfonsson, Olsson and Hursti2015). Other studies have investigated whether the professional background of the individual providing support has an impact on outcomes. One study targeting depression (Castro et al., Reference Castro, López-del-Hoyo, Peake, Mayoral, Botella, García-Campayo and Gili2018) found increased completion rates with the addition of therapist emails compared to technical assistance only. However, several other studies suggest no benefit from trained clinician input (Kobak, Greist, Jacobi, Levy-Mack, & Greist, Reference Kobak, Greist, Jacobi, Levy-Mack and Greist2015; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Titov, Andrews, McIntyre, Schwencke and Solley2010; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Andrews, Davies, McIntyre, Robinson and Solley2010). In another depression intervention, feedback was provided by either trained counsellors or by peer participants (Westerhof, Lamers, Postel, & Bohlmeijer, Reference Westerhof, Lamers, Postel and Bohlmeijer2019). While access to a counsellor increased the number of site visits and assignments downloaded, and was preferred by participants, there were no group differences on intervention completion or effectiveness. Results from this small number of studies suggest the effect of guidance in web-based intervention might be primarily attributable to non-specific factors of the interaction with participants, such as providing motivation and encouragement. Given the potential impact on intervention costs, the effect of clinical v. technical guidance on adherence remains an important area for ongoing research.

Overall, statistical heterogeneity between studies was small, albeit statistically significant for average completion of intervention content. In part, this can be attributed to the narrow inclusion criteria and definition of guidance. Furthermore, six of the included studies were from the same research team and were linked with regard to recruitment and other aspects of the research protocol. For example, all recruited individuals through the same website and had similar instructions for therapists providing guidance (see Table 1). In addition to increasing homogeneity, results from these studies were more likely to be similar and thus may have skewed the present meta-analysis. Overall, the increased number of publications in the field and the homogeneity between some of the included studies is likely to have contributed to the much clearer findings from this study compared to previous meta-analyses and reviews (Domhardt et al., Reference Domhardt, Gesslein, von Rezori and Baumeister2019). With increasing numbers of studies in the field, future research could further explore guidance and adherence in the context of disorders as well as the impact of intervention characteristics on the relationship between the two variables.

A number of limitations with regard to this meta-analysis need to be considered. The inclusion criteria were narrow thus potentially limiting the generalisability of the findings to other settings. For example, several studies used forms of guidance that did not meet the criteria defined for this meta-analysis and thus were excluded. It remains unclear whether guidance such as automated feedback, reminders, or pure technical support has the same effect on adherence as observed in the included studies. Intervention adherence was defined differently across studies. Of the 21 studies reporting the number of individuals who completed the intervention, only two studies provided a definition of what was considered an adequate dose (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Staples, Terides, Fogliati, Sheehan, Johnston and Titov2016; Fogliati et al., Reference Fogliati, Dear, Staples, Terides, Sheehan, Johnston and Titov2016), whereas other studies reported completion of the entire intervention content. These two conceptualisations are fundamentally different and likely introduced variance to the results. It should also be noted that of the included studies, ten were conducted in Australia and, of those, several shared similar protocols. While this is rather a general limitation of the field of web-based mental health interventions, with most studies having been conducted in Sweden and Australia (Olthuis et al., Reference Olthuis, Watt, Bailey, Hayden and Stewart2016), it highlights that findings from this review may not translate into other cultural contexts. Finally, while this meta-analysis showed increased adherence in guided intervention conditions, it is worth bearing in mind that the use of the intervention technology may only represent one aspect of engagement with the intervention content. Depending on the intervention and disorder, the completion of homework, monitoring records, or behavioural experiments between online sessions are likely key to the therapeutic efficacy (Michie, Yardley, West, Patrick, & Greaves, Reference Michie, Yardley, West, Patrick and Greaves2017).

Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis marks an important step in investigating the rationale for providing guidance in computerised mental health interventions and quantifying the effect of guidance on adherence. Understanding the impact of guidance may significantly contribute to improving adherence in such interventions, increase their efficacy, and thus increase acceptability and translation into practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004621.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant [grant number DP170100237].

Conflict of interest

None.