1. Introduction: Goals and scope

The present paper focusses on the multiple readings that finite adverbial clauses assume in relation to their degree of syntactic and semantic integration with the host clause. Our empirical evidence is mainly from English and Italian, supplemented with Dutch data, because the verb-second (V2) patterns in that language offer additional insight into the syntactic analysis. Our core data consist of adverbial clauses introduced by the English conjunctions while and Italian mentre. Throughout, these clauses are taken as representative of a wider range of finite adverbial clauses.

1.1 The data

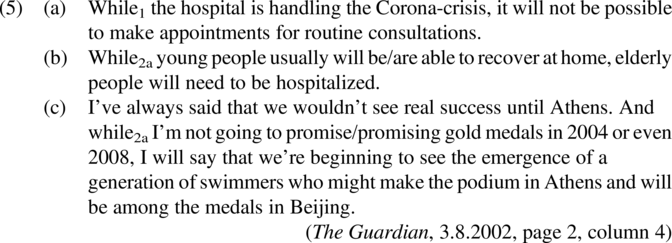

Both English finite while clausesFootnote 2 and Italian finite mentre clauses can encode a number of distinct readings.Footnote 3 The relevant patterns are illustrated in English (1) and Italian (2). Subscripts distinguish the readings of the clauses; the distinction between while 2a/mentre 2a in (1b) and (2b) and while 2b/mentre 2b in (1c) and (2c) arises from the fact that in Haegeman’s (Reference Haegeman1984a and subsequent work) work both these uses of the adverbial clauses were viewed as instances of ‘peripheral adverbial clauses’, a point we reconsider below (see Schönenberger & Haegeman (Reference Manuela and Haegeman2021), Haegeman & Schönenberger (Reference Haegeman and Schönenberger2021).

The temporal while 1 clause in (1a) is a modifier of the event encoded by the host clause; the adversative while 2a clause in (1b) encodes a background assumption which provides evidence to enhance the relevance of the host clause proposition; the while 2b clause in (1c) is a temporal adverbial clause which modifies the speech event. The contrast between English (1a) and (1b) is replicated in Italian. Mentre clauses do not seem to lend themselves, though, to be used as speech event modifiers (2c), for reasons that are unclear to us and we assume are tangential to the present discussion. The unavailability of the speech event modifier use of a mentre clause is perhaps related to specific aspectual restrictions relating to mentre (see Section 2.1.1). An acceptable alternative to Italian (2c) would be (2d). Incidentally, the unavailability of the speech event modifier use of mentre clause indirectly supports the hypothesis that English while 2a and while 2b must be distinguished.Footnote 4

There are parallels to be observed between the examples above and other adverbial clauses: we illustrate this with conditional clauses. Conditional clauses introduced by English if or by Italian se also display various functions. An if/se clause can function as an event conditional ((3a), (4a)), as a conditional assertion ((3b), (4b)) (Kearns Reference Kearns2006) or as a speech event modifier ((3c), (4c)). Only event conditionals (sometimes) allow paraphrasing with if and when (3d) in English or with se e quando (4d) in Italian. Conditional assertions in ((3b), (4b)) echo contextually salient propositions for which they provide a background proposition which enhances the relevance of the host proposition; in such conditionals, if can be paraphrased with ‘given that’. This conditional does not chart possibilities, as a regular conditional would do, but echoes a contextual proposition which highlights a fact and which forms the background for the matrix proposition.Footnote 5 Importantly, conditional assertions do not have to be strict echoes of actual utterances. ‘They may also be echoes of an internal or mental proposition (thought) such as the interpretation of an experience, perception etc.’ (Declerck & Reed Reference Declerck and Reed2001: 83). The if and when paraphrase is not available for conditional assertions. Observe that, differently from mentre (2c), the Italian conditional conjunction se ‘if’ can introduce a speech event modifier (4c).

The patterns illustrated for English while and Italian mentre can be replicated, for instance, for Dutch terwijl or for French tandis que. Section 4.2.2 discusses Dutch patterns in which V2 syntax sheds additional light on the syntax of adverbial clauses of the type illustrated in (1b) and (2b).

1.2 Goals

Our first goal is to discuss the diagnostics introduced to distinguish the while/mentre clauses in (1a) and (2a) from those in (1b) and (2b). We evaluate the diagnostics and, following Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, Reference Freyb), we reassess Haegeman’s (Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc, Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991, Reference Haegeman2012) original binary classification of adverbial clauses in terms of central vs. peripheral adverbial clauses. Haegeman’s binary classification will be replaced by a ternary classification, along that developed by Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, Reference Freyb; see Heycock Reference Heycock, Everaert and Riemsdijk2017), with the following three clause types:

-

• Central Adverbial Clauses (CACs), corresponding to while 1/mentre 1 clauses

-

• Peripheral Adverbial Clauses (PACs), corresponding to while 2a/mentre 2a clauses

-

• Non-integrated Adverbial Clauses (Frey’s NonICs), corresponding to English while 2b clauses, as well as to English if 2b clauses, and Italian se 2b clausesFootnote 6

Drawing from data from both English and Italian, we first focus on PACs introduced by while 2a/mentre 2a and we discuss them as evidence to further confirm Frey’s (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, Reference Freyb) ternary classification, adding support for Frey’s claim that PACs pattern with high sentential adverbials. In Section 5, we turn to non-integrated finite adverbial clauses and demonstrate that though it is appropriate to set such clauses apart from PACs, the non-integrated clauses identified in our paper do not share all the properties associated with Frey’s NonICs, suggesting that non-integrated clauses are not a homogeneous set. Using the framework of Greco & Haegeman (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020), will elaborate a tentative, more abstract analysis to allow for some unification of non-integrated finite adverbial clauses.

1.3 Organization of the paper

Section 2 presents an inventory of differences between the adverbial clauses introduced by while 1/mentre 1 in (1a)/(2a) and those introduced by while 2a/mentre 2a in (1b)/(2b). These differences have often been signalled in the literature as evidence for postulating a difference in structural integration. Section 3 reviews two syntactic analyses that have found relatively wide support in the existing literature in one form or another. Section 4 reassesses the diagnostics from Section 2 as the basis of the syntactic analyses presented in Section 3 and concludes that, in fact, the diagnostics are not fit for purpose. This section replaces the binary typology of adverbial clauses introduced in Sections 2 and 3 with a ternary typology, inspired by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b). Section 5 focusses on the syntactic and interpretive properties of non-integrated clauses.

2. The external syntax of adverbial clauses: Diagnostics

In a number of papers, Haegeman has argued for a binary classification of adverbial clauses:

-

• ‘central’ adverbial clauses like those introduced by while 1/ mentre 1 in (1a) and (2a) modify the state of affairs encoded in the matrix domain

-

• ‘peripheral’ adverbial clauses like those introduced by while 2a,b in (1b)/(1c) and mentre 2a in (2b) provide contextually accessible background propositions that contribute evidence for the relevance of the host proposition

This section reviews some diagnostics used to substantiate this classification. The discussion compares while 1/mentre 1 clauses modifying the event expressed by the host clause with while 2a/mentre 2a clauses that encode a background assumption. In Section 4.3 speech event modifiers as in (1c) will be argued to constitute a separate class; their syntax is then discussed in Section 5.

2.1 Scope phenomena (non-exhaustive)

A range of distinctions between the adverbial clauses in (1a)/(2a) and those in (1b)/(2b) reflects their interaction with the host clause in terms of scope. We review just some of these here. For further discussion see Haegeman & Robinson (Reference Haegeman and Robinson1979), Haegeman (Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc), Haegeman & Wekker (Reference Haegeman and Wekker1984), Haegeman (Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991/Reference Haegeman2009, Reference Haegeman2003, Reference Haegeman2012, Reference Haegeman2019, Reference Haegeman, Holler, Suckow and de la Fuente2020), Haegeman, Shaer & Frey (Reference Haegeman, Shaer and Frey2009).

2.1.1 Temporal/modal/aspectual subordination

The scopal distinction between the central adverbial clauses in (1a)/(2a) and the peripheral adverbial clauses in (1b)/(2b) is reflected in their relation to temporal, aspectual and modal operators (i.e. so-called TAM operators) in the host clause.

2.1.1.1 Temporal subordination

Typically, central adverbial clauses display effects of temporal subordination. This is especially clear in English future-oriented adverbial clauses, as widely discussed in the literature (see Palmer Reference Palmer1965, Reference Palmer1974, Reference Palmer1990; Jenkins Reference Jenkins, Peranteau, Levy and Phares1972; Haegeman & Robinson Reference Haegeman and Robinson1979; Haegeman Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc; Haegeman & Wekker Reference Haegeman and Wekker1984; Niewint Reference Niewint1986 and references cited). The temporal while 1 clause in (5a) contains a present tense form is; yet it refers to a future state of affairs: As a result of temporal subordination, the present tense encoded on is inherits the futurity reading from the future time modal will in the host clause, a phenomenon dubbed ‘will-deletion’ (Jenkins Reference Jenkins, Peranteau, Levy and Phares1972). In (5a), encoding futurity by means of the modal will in the temporal while clause would switch the interpretation to that of a peripheral while 2a clause. On the other hand, in the peripheral while 2a clause in (5b), futurity is encoded independently, by the modal will, and in the peripheral while 2a clause in (5c), futurity is encoded by periphrastic be going to. Notably, replacing the expressions of futurity in (5b) and in (5c) with present tense forms affects the interpretation: In (5b), a present tense form in the adverbial clause either receives a present time interpretation (‘while it is the case now …’), as in a peripheral while 2a clause, or it receives a future time reading due to subordination to the future time in the matrix clause (‘will need’) meaning that the clause is turned into a central while 1 clause acting as a temporal modifier of the host clause. In (5c), replacing be going to with a present tense form shifts the temporality of the peripheral clause to the present.

There are also restrictions on tense forms in mentre 1 clauses. Giusti (Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 723) says:

Il Tempo della principale è sempre uguale a quello della temporale, tranne nel caso del perfetto (semplice e composto) a cui corrisponde un imperfetto nella temporale.

[The tense of the main clause is always identical to that in the temporal clause, with the exception of the perfect (simple and complex) to which corresponds an imperfect in the temporal clause (our translation).]

Note that in (6), the Italian analogue of (5), the central mentre 1 clause (6a) does contain a future tense gestirà ‘will handle’. This is because the Italian sequence of tense system differs from the English one in that Italian does not operate the analogue of will-deletion in the central clause. A full discussion of language-specific rules of temporal subordination is beyond the scope of this paper. The example (6b) is parallel with (5b).

2.1.1.2 Modal subordination

In (7a), the central while 1 clause is in the scope of the epistemic adverb probably; in (7b), the peripheral while 2a clause is not in the scope of the epistemic adverb (see Verstraete Reference Verstraete2002: 242–243). The attested (7c) illustrates the two types of adverbial clauses: epistemic certainly in the root clause scopes over the central while 1 clause though not over the peripheral while 2a clause, whose epistemic value is encoded in probably.

The effects are reproduced in Italian (8):

The central mentre 1 clause in (8a) is in the scope of probabilmente ‘probably’, unlike the peripheral mentre 2a clause in (8b).

The same effect is illustrated in (9) and (10).

In (9) the epistemic adverb probably/probabilmente directly modifies the central while 1/mentre 1 clause; in (10), this option is unavailable for a while 2a/mentre 2a clause.

2.1.1.3 Aspectual subordination

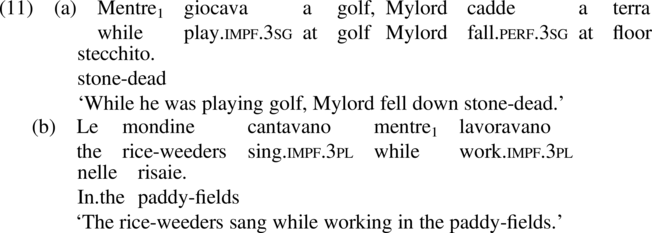

In some cases, the relation between a central adverbial clause and the host clause may entail restrictions on the choice of aspectual forms. Giusti (Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 721) defines temporal mentre 1 as a conjunction functioning as an introduttore temporale (‘temporal subordinating conjunction’). Mentre 1 clauses establish a temporal relation between the event they express and the event in the main clause, adding durativity to the simultaneity. In (11a) the main clause encodes an instantaneous event, in (11b) it encodes a continuous event (11b) (Giusti Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 723 ex. (10)):

One aspectual restriction on the mentre 1 clause is that, while the clause modified by a mentre 1 clause may contain a perfective pattern, the tense inside the mentre 1 clause itself must be simple (compare (11a) and (12)). See Giusti (Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 723) for further restrictions.

The aspectual restriction imposed by mentre 1 in (12) does not obtain for peripheral mentre 2a: While central mentre 1 clauses associate with durative aspect, peripheral mentre 2a clauses can also encode a punctual event (13a) (Giusti Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 730). In addition, mentre 2a clauses may contain a perfective form (13b).

In line with the literature, we assume that TAM restrictions are syntactically determined. For instance, in the context of his formalization of sequence of tense patterns, Hornstein (Reference Hornstein1990: 43) writes:

Temporal adjuncts headed by temporal connectives such as when, while, after, before, as, until, and since interact with the tense of the matrix clause. … There are rather specific tense-concord restrictions that obtain between the tense of the matrix clause and the tense of the modifying clause. These restrictions can be largely accounted for structurally in terms of the C[onstraint] on D[erived] T[ense] S[tructures] and the rule that combines these clauses into complex tense structures.

Hornstein’s constraints on temporal structures are confined to what we label central adverbial clauses and do not extend to peripheral adverbial clauses. He observes:

There is a secondary conjunctive interpretation that all these connectives (as, while, when) shade into. They get an interpretation similar to and in these contexts. And is not a temporal connective, and these conjunctive interpretations do not tell against the theory [of temporal subordination and complex tense structures]. (Hornstein Reference Hornstein1990: 206 fn. 19)

Importantly, though, peripheral adverbial clauses cannot be fully equated to conjuncts. We illustrate this point briefly for English while 2a clauses, where at least two differences emerge. On the one hand, differently from second conjuncts, peripheral adverbial clauses which follow the associated host clause do not allow subject ellipsisFootnote 8 (14a, b). In addition, unlike second conjuncts, peripheral adverbial clauses do not allow gapping (15a, b).

Besides TAM operators, a range of other sentential operators can scope over the temporal while 1/mentre 1 clause and cannot scope over the peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clause. We illustrate some patterns; for additional English and Dutch data see Haegeman (Reference Haegeman2019, Reference Haegeman, Holler, Suckow and de la Fuente2020); for Italian see Giusti (Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 731–738).

2.1.2 Sentential negation

A central while 1/mentre 1 clause can be in the scope of a sentential negative operator, as shown in (16) and (17):

A sentential negator cannot scope over a peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clause:

2.1.3 Focus

Temporal while 1/mentre 1 clauses can be in the scope of focal operators such as even/perfino in (20), and they can constitute the focus of a cleft sentence as shown in (21) (Giusti Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 734).

These options are unavailable for while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, as shown in (22) and (23).

Example (24) illustrates while 1/2a/mentre 1/2a clauses which are ambiguous between the central temporal reading and the peripheral reading.

As shown in (25), the central while 1/mentre 1 clause can function as a clausal predicate, a pattern unavailable for the peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clause.

2.1.4 Interrogative scope

A central while 1/mentre 1 clause can be in the scope of an interrogative yes/no operator. This is not possible for peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses. Examples (26a–d) illustrate root interrogatives, (27) replicates the contrast for embedded interrogatives.

The same contrast emerges with wh-scope. As shown in (28a) and (28b), central while 1/mentre 1 clauses can function as a reply to a wh-question. This is not possible for peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, as shown in (28c) and (28d). This point is also discussed in Giusti (Reference Giuliana, Renzi, Gianpaolo and Cardinaletti2001: 734–735), whose (71a) and (75a) are repeated as (28b) and (28d).

2.2 A first syntactic analysis

Based on the scope effects discussed in Section 2.1, Haegeman (Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc, Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991, Reference Haegeman2003, Reference Haegeman2012, etc.) proposes a distinction between central and peripheral adverbial clauses that is grounded in syntax. Her underlying assumption is that scope relations are conditioned by structure (pace Declerck & Reed Reference Declerck and Reed2001: 37–38), more specifically by c-command relations as defined in the generative paradigm. Haegeman develops two alternative proposals, one that considers both adverbial clause types as syntactically integrated, differing only in the level of adjunction and a second one according to which central adverbial clauses belong to sentence-internal syntax (also referred to as the narrow syntax, or sentence-level syntax, as opposed to discourse-syntax), while peripheral adverbial clauses are extra-sentential constituents, that is, outside syntax proper and integrated at the level of discourse-syntax. Here, we summarize these two alternatives schematically.

-

(i) In one approach, the level of adjunction is crucial in distinguishing central adverbial clauses from peripheral adverbial clauses:

-

• central while 1/mentre 1 clauses are adjoined within the TP domain, either to vP/VP or to TP, as shown in (29)

-

• peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are adjoined to the root CP, as shown in (30a)

-

-

(ii) In the second approach, syntactic integration as such is the distinctive factor:

-

• as before, central while 1/mentre 1 clauses are adjoined within the TP domain, either to vP/VP or to TP, as shown in (29)

-

• peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are extra-sentential, i.e. they are non-integrated ‘orphans’Footnote 9 which combine with the host clause at the discourse level (30b); the idea was that peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are assimilated to non-restrictive relative clauses (but see note 18 for some provisos)

-

Both analyses achieve the desired effect that TP-internal constituents c-command central adverbial clauses and do not c-command peripheral adverbial clauses, leading to the scope effects illustrated above. Recall that in Haegeman’s original classification, peripheral adverbial clauses comprise both adversative while 2/mentre 2a clauses and conditional assertions (if 2a/se 2a) as well as speech event modifiers like those illustrated in (1c) for while 2b and the conditional if 2b/se 2b clauses in (3c) and (4c). We return to this point in Sections 4.2 and 5.

2.3 Further support for the proposal

This section presents two additional differences between central adverbial clauses and peripheral adverbial clauses which follow from the syntactic analyses outlined above. We again concentrate solely on peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses. Speech event modifying while 2b clauses are addressed mainly in Section 5.

2.3.1 VP anaphora and sloppy identity

Both analyses in (29)–(30) lead to the correct prediction that in English VP anaphora can affect central while 1 clauses while this is unavailable for peripheral while 2a clauses. In (31a) so does James can be made explicit as in (i), with the while 1 clause as part of the ellipsis and with his being interpreted as coreferential either with John (‘strict identity’) or with James (‘sloppy identity’) as in (ii). Example (31b) shows that a peripheral while 2a clause is not affected by VP anaphora: The string so has Janet only has reading (i), in which the while 2a clause is not contained in the ellipsis site. Reading (ii) is unavailable. Crucially, this contrast does not generalise to all anaphora. Example (31c) shows that the peripheral clause can be included in sentential anaphora, i.e. both readings are available here. What is crucially excluded is VP-anaphora, providing evidence that these adverbial clauses are not as low as those affected by VP anaphora.Footnote 10

In (32a), neanche Don Gaetano can have a strict identity reading for suo processo ‘his trial’ as paraphrased in (i) or a sloppy identity reading as in (ii). In (32b), the anaphoric neanche Piero does not comprise the mentre 2a clause (compare (i) and (ii)). Moreover, sentential anaphora with e questo è vero anche per ‘and this is true also for’ is also available for mentre 2a clauses, as seen in (32c).

2.3.2 Embedding

2.3.2.1 Embedding within complement clauses

Assuming the analysis in (29)–(30a) above, in which the level of integration sets apart central while 1/mentre 1 clauses from peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, we correctly predict that both adverbial clauses are embeddable within complement clauses. See also Frey (Reference Frey2018: 14, Reference Frey2020a, b), but see Section 3.2.

Also, anticipating the discussion in Section 3.1, examples (33) and (34) are problematic for the non-integration analysis of peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, which, according to this analysis, would be outside the scope of the sentence-internal syntax.

2.3.2.2 Embedding within central adverbial clauses

Central while 1/mentre 1 clauses are embeddable inside central adverbial clauses such as the conditional clauses in (35). As suggested by the bracketing, the while 1/mentre 1 clauses are to be viewed as temporal modifiers of the event encoded in the if 1/se 1 clause. In (35a) the temporal while 1 clause, which is embedded in the (bracketed) central conditional clause, is modally subordinated, with its past perfect tense in had met inheriting the irrealis reading from the irrealis modal in the host clause (‘would have asked’). The temporal mentre 1 clause is embedded in the conditional se 1 clause in (35b). Example (36) is an additional illustration of the same pattern.

In contrast, peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses cannot be embedded inside central adverbial clauses such as conditional clauses.

The while clause in (37a) must be read as a central while 1 clause: Its present tense can only be interpreted as temporally subordinated, leading to the strange assumption that his sister’s Cambridge degree is temporary and that at some future point she will lose her Cambridge degree. A (peripheral) adversative reading of the while clause as paraphrased in (37b) is not available.Footnote 11 The same effect obtains for Italian (38).

It has been independently shown that the left periphery of central adverbial clauses, such as the event if 1 conditional, is impoverished (for arguments see e.g. Haegeman Reference Haegeman2003, Reference Haegeman2012; Frey Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b). The non-embeddability of peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses within central adverbial clauses is correctly predicted by both syntactic analyses of peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses outlined in (30). In both analyses – the high insertion analysis of the peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses (30a) and the orphan hypothesis (30b) – peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are associated with the (left)Footnote 12 periphery of the clause, and this is independently known to be restricted in the case of central adverbial clauses.

2.4 Summary

Table 1 summarizes the differences between central adverbial clauses and peripheral adverbial clauses. Recall that our argumentation remains restricted to adversative while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, (see Sections 3.1 and 5).

Table 1 Diagnostics to set apart central and peripheral while/mentre clauses.

3. The syntactic typology

Based on the scope effects reviewed in Section 2.1, Haegeman (Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc, Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991, Reference Haegeman2003, Reference Haegeman2012, etc.) argues for a syntactic distinction between the central and peripheral adverbial clauses and puts forward two alternative proposals. In the first, both adverbial clause types are syntactically integrated, differing only in the level of adjunction; in the second, central adverbial clauses belong to sentence-internal syntax, while peripheral adverbial clauses are sentence-external constituents and are integrated at the level of discourse-syntax.

Haegeman crucially views the two analyses in (30) as alternatives: All peripheral clauses are analysed either in terms of different degrees of embedding or in terms of (non-)integration. However, it has become clear over time that both analytic options must be available simultaneously in the grammar, albeit for distinct data (see also Frey Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b, to whose work this section is heavily indebted). We show first that the analysis of peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses as either orphan constituents or as CP-adjoined is untenable. Section 5 demonstrates how an updated version of the orphan account can capture the properties of speech event modifiers such as while 2b temporal clauses (in (1c)) or if 2b/se b conditionals in (3c) and (4c).

3.1 Problems for an orphan account of peripheral adversative while 2a/mentre2a clauses

3.1.1 Embedding

As shown by Haegeman et al. (Reference Haegeman2009) and Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b), a non-integration (orphan) hypothesis for adversative while 2a/mentre 2a clauses is challenged by the fact that these adversative clauses can be embedded, with sequence of tense effects and pronominal binding as the reflex of their syntactic integration. Consider (39).

In the English (39a), for instance, the viewpoint and the propositional content of the while 2a clause are attributed to the subject of the matrix clause the ethicist, and not to the speaker, who may well disagree with this. In addition, in the while 2a clause the past tense was is imposed by the embedding of the while 2a clause under a past tense matrix verb (declared): the ethicist would have made the statement It is not immoral to take pride in one’s accomplishments. Footnote 13 These properties are replicated for Italian in (39b). It is difficult to envisage how a non-integration account could naturally capture these scope effects.

3.1.2 Comparative evidence: Verb second

As shown by e.g. Reis (Reference Reis, Christa, Karl-Heinz and Schwarz1997) and Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b), a non-integration (orphan) hypothesis for adversative while 2a/mentre 2a clauses is also contradicted by the fact that in V2 languages the analogues of these adverbial clauses can and must constitute the prefield constituent of a V2 clause, standardly considered ‘a position of full integration’ (Frey Reference Frey2018: 13). This is illustrated by the Dutch terwijl 2a clause in (40).

The example also shows that the Dutch terwijl 2a clause cannot function as an extra-sentential constituent in the V3 pattern (see Haegeman & Greco Reference Haegeman and Greco2018, Greco & Haegeman Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020), that is, it cannot constitute a non-integrated orphan.

3.2 Problems for the CP/ForceP adjunction account of peripheral adversative terwijl 2a clause

The syntactic analysis of the while 2a clause in terms of CP/ForceP-adjunction (Haegeman Reference Haegeman2003, Coniglio Reference Coniglio2011, Frey Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016) in (30a) is further challenged by the word order patterns illustrated in (39) and (40). First, in the embedded environment (39) the complementizer that linearly precedes the adverbial clause. If the while 2a clause were genuinely CP-adjoined, it ought to precede the complementizer. Second, in the V2 pattern in (40) ForceP/CP-adjunction should entail that the adverbial clause can precede a full-fledged V2 clause, contrary to fact.

4. A reappraisal of the diagnostics

4.1 The diagnostics

Section 2 has shown that peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses differ from central adverbial while 1/mentre 1 clauses in a number of ways. Based on these differences, Haegeman (Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991, Reference Haegeman2003) developed two alternative analyses: according to one analysis, peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are structurally less integrated with the host clause (30a); according to the alternative, they are not syntactically integrated (30b) and link up with the host clause at the level of discourse. On closer inspection, the diagnostics Haegeman advances to support her conclusions and the corresponding syntactic analyses are not quite fit for purpose and fail to provide conclusive evidence for either of the two analyses advanced. Indeed, the diagnostics used in Section 2 for setting apart peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses also systematically single out epistemic adverbs, exemplified below by the epistemic modal adverb probably/probabilmente. Such adverbs are standardly taken to be part of the clausal domain (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 34; also e.g. Cinque Reference Cinque1999; Ernst Reference Ernst2001, Reference Ernst and Di Sciullo2002, Reference Ernst2007, Reference Ernst2009), witness the fact that in English they follow the canonical subject position (41a). Epistemic adverbs

-

• are outside the scope of the temporal operator, see (41);

-

• are outside the scope of negation, see (42);

-

• cannot be focused or cleft, see (43);

-

• cannot be wh-questioned, see (44);

-

• do not undergo VP Ellipsis (VPE), see (45);

-

• do not embed in central adverbial clauses, see (46).

As shown by (47), the unacceptable patterns in (41)–(46) are not due to the categorial status of the -ly/-mente adverbs. The patterns are acceptable for temporal adverbs such as English recently (see Li, Shields & Lin Reference Li, Shields and Lin2012: 232) or Italian recentemente ‘recently’.

Table 2 summarizes the parallelisms between central while 1/mentre 1 clauses and temporal adverbs such as recently/recentemente, on the one hand, and between peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses and epistemic adverbs such as probably/probabilmente, on the other. The table also demonstrates the differences between the two clause types and between the two types of adverbs.

Table 2 Adverbial modifiers: Clauses and non-clausal.

Even if epistemic adverbs such as probably/probabilmente may well be argued to be interpreted higher than their surface position, their linear position shows them as part of the sentence-internal syntax (see Cinque’s Reference Cinque1999; Ernst Reference Ernst2001, Reference Ernst2007, Reference Ernst2009) and, hence, they must be integrated in the clausal structure. The evidence for their syntactic integration has already been mentioned: Epistemic adverbs can typically follow the subject position in English (41a). Furthermore, epistemic adverbs constitute the prefield constituent in V2 clauses in Dutch (see Frey Reference Frey2020a: 34 ex. (93) for the same argument from German) and cannot give rise to the V3 patterns typically associated with extra-sentential constituents, such as, for instance, eerlijk gezegd ‘honestly’ illustrated in (48c).Footnote 14

From the parallelisms between while 2a/mentre 2a clauses and epistemic adverbs we can conclude the following:

-

(i) W.r.t. syntax/degree of integration of the adversative while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, the diagnostics do not show that peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are not integrated with the host clause.

-

(ii) The diagnostics only show that, like epistemic adverbs, peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses must be somewhere ‘higher’ in the clausal structure and outside the relevant scope domains.

-

(iii) Independently, the distribution of epistemic adverbs such as probably/probabilmente shows that these adverbs must at some point be part of the clausal domain. Like several other constituents, they may, of course, move to the left peripheral CP domain.

-

(iv) Table 2 also shows that in terms of the diagnostics, central adverbial clauses introduced by while 1/mentre 1 pattern with regular TP-related adverbs.

4.2 Speech act modifiers are different

In Section 2, we identified three uses of English while clauses: the relevant examples in (1) are repeated for convenience in (49).

So far, we have been focusing exclusively on the contrast between (49a) and (49b). The central temporal while 1 clause in (49a) modifies the event encoded in the host clause; the peripheral adversative while 2a clause in (49b) provides a background assumption enhancing the relevance of the proposition encoded in the host clause. Example (49c) contains a temporal while clause, but this is now not used as a temporal modifier of the event encoded in the host clause, i.e. the timing of the BBC’s announcement, but rather it modifies the speech event time (see Haegeman & Schönenberger to appear). Recall that the subscripts ‘2a’ and ‘2b’ in (1) are intended to reflect Haegeman’s earlier analysis, in which both the while 2a clause and the speech event modifying while 2b clause where considered as peripheral adverbial clauses. It turns out, though, that the while 2b clause in (49c) is actually a temporal while clause recycledFootnote 15 as a temporal modifier of the speech event. Similarly, in (3c), an event conditional is recycled as a conditional on the speech event.Footnote 16 As mentioned in Section 1, Italian temporal mentre 1 clauses cannot be recycled as speech event modifiers, but this is specific to mentre clauses: an event conditional clause introduced by se 1 ‘if’ can be recycled as a speech event conditional, as shown in (4b, c), repeated here in (50).

Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) shows convincingly that Haegeman’s binary classification is inadequate, regardless of the specific analysis adopted. We reproduce two arguments here, both drawn from Frey’s discussion. See also Haegeman & Schönenberger (to appear).

4.2.1 Embedding

Speech event modifying adverbial clauses like the while 2b clause in (49c) are unembeddable. Consider (51).

In (51a), the (temporal) while clause modifies either the time of the event encoded in the main clause (our while 1) or it is ‘recycled’ as a temporal modifier of the speech event (our while 2b). In the former reading, the present tense are in the while clause is temporally subordinated to that in the matrix clause, that is, it has a future interpretation. In the second reading, present tense are refers to speech time. The embedded while clause in (51b) must be interpreted as modifying the time of the event encoded in the (bracketed) clause it modifies (while 1); an interpretation as a ‘recycled’ temporal modifier of the speech event (while 2b) is unavailable.

4.2.2 V2 patterns

Speech event modifying adverbial clauses like Dutch terwijl 2b clauses cannot constitute the first constituent of a V2 clause, as shown in (52).

Instead, the speech event modifying terwijl 2b clause is an extra-sentential constituent which combines with a full-fledged V2 root clause, leading to a licit V3 order.

4.3 A ternary classification of adverbial clauses

Table 3 summarizes the properties of English while clauses: Haegeman’s original binary classification was essentially in line with properties A–F and H, but taking into consideration properties G and I – pointed out in Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, Reference Freyb), we conclude that adversative while 2a clauses and speech event modifying while 2b clauses must be differentiated.

Table 3 Three types of adverbial clauses.

Frey (Reference Frey, Reich and Speyer2016, Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) develops a ternary classification in terms of (i) CAC as in (1a)/(49a), (ii) PAC2a as in (1b)/(49b) and (iii) NonIC2b as in (1c)/(49c).

From this classification, we retain that speech act modifying while 2b clauses are distinct from while 2a, clauses, which provide a contextually salient proposition that interacts with the main clause proposition. We turn to the syntax of while 2b clauses in Section 5.Footnote 18 From now on we reserve the term PAC for the while 2a/mentre 2a clauses, which provide a background assumption as evidence for relevance of the proposition encoded in the host clause.

4.4 Epistemic adverbials and PACs

This section offers additional support for the parallelism between peripheral adversative while2a /mentre 2a clauses and epistemic adverbs, as postulated by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b).

Frey adopts Krifka’s (Reference Krifka2017, to appear) hierarchy in (54):

For our purposes, the main properties of the relevant projections identified by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020b) are the following:

-

(i) ‘The TP represents a proposition.’

(Frey Reference Frey2020b: 17 ex. (46i))

-

(ii) ‘The judgement phrase (JP) encodes the private assessment of a proposition by a judge.’

(Frey Reference Frey2020b: 17 ex. (46ii))Footnote 20

-

(iii) ‘The speech act phrase (ActP) encodes a speech act performed by a speaker.’

(Frey Reference Frey2020b: 18 ex. (46iv)

As discussed in Section 4.1, Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) unifies PACs and subjective epistemic adverbials as both encoding not-at-issue expressions: in other words, like epistemic adverbs, PACs are not part of the propositional content that is being communicated. In terms of their syntax, Frey proposes that PACs modify JP, which is external to the proposition (i.e. TP); JP also hosts subjective epistemic adverbs. The parallelisms observed between epistemic adverbs and PACs in Section 4.1 and summarized in Table 2 would thus be syntactically encoded if the two were assigned the same syntactic position. Frey’s (Reference Frey2020a) subjective modals, which including epistemic adverbs, are characterized as follows: ‘Subjective modals, being not-at-issue, are external to the proposition which is communicated by the clause in which they occur’ (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 10).

Among the functions related to JP listed in Frey (Reference Frey2018: 24) are the following: ‘A subjective modal operating on a proposition ϕ expresses the degree of the judge’s confidence in the truth of ϕ’ (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 12 ex. (32i)). Frey’s analysis for subjective modals makes the following correct predictions:

-

• In complement clauses, Frey’s (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a) subjective epistemic modals will follow the complementizer.

-

• The incompatibility of epistemic adverbs with CACs follows on the assumption that CACs have a deficient left periphery. For the sake of the present discussion, we follow Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a) and assume that CACs are structurally truncated.Footnote 21

-

• Subjective epistemic modals function as the initial constituent in a V2 configuration when they move to a left-peripheral specifier position.

Following Frey’s insights as confirmed by the parallelisms listed in Table 2, we assume that in terms of Krifka’s approach, ‘A PAC is base-generated in a position adjoined to the JP of its host’ (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 22 ex, (59)). This leads to the following correct predictions:

-

• PACs can be embedded in a complement clause; in which case they will follow the complementizer.

-

• The incompatibility of PACs with CACs follows on the assumption that CACs have a truncated left periphery as in Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a). See also footnote 20 for discussion.

-

• PACs can figure as the initial constituent in a V2 configuration, moving to a left-peripheral specifier.

As a tentative interpretive characterization, we propose that a PAC A in a clause S denoting the proposition ϕ encodes that a judge selects an accessible/salient proposition A as the discourse context in which the host proposition ϕ is maximally relevant. The kind of relevance relation will then be determined by the choice of subordinator.

A problem for the analysis proposed here is that while epistemic adverbs may surface clause-medially in what would be their JP positionFootnote 22, peripheral adverbial clauses must forcibly move to the clausal periphery.Footnote 23 One option would be to relate this to a weight effect;Footnote 24 alternatively, peripheral adverbial clauses host a discourse-related feature which forces them to attain the appropriate left-peripheral position.

5. Non-integrated clauses are not homogeneous

5.1 Non-integrated adverbial clauses: External and internal syntax

This section examines whether the properties associated with Frey’s own NonICs (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) extend to the speech event modifying clauses identified as non-integrated here. Because our classification is based on different empirical data, we refrain from using Frey’s abbreviation ‘NonIC’ to designate our own non-integrated speech event modifying adverbial clauses. Though we believe that our diagnostics are faithful to the spirit of Frey’s proposal, the clause types we identify as non-integrated turn out not to share all the properties Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) attributes to his NonICs. Frey associates the following distributional and interpretive properties with NonICs (Frey Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b).

-

(i) Like CACs, PACs can be placed in the prefield of a German V2 clause, a position of full integration. The prefield position is unavailable for NonICs (Frey Reference Frey2018: 13, Reference Frey2020a: 30, Reference Frey2020b: 10–11). This property carries over to our speech event modifying adverbial clauses.

-

(ii) Embedding together with the host clause is available for CACs and for PACs. Embedding is unavailable for NonICs (Frey Reference Frey2018: 14, Reference Frey2020a: 30, Reference Frey2020b: 11). Our speech event modifying adverbial clauses also fails to embed.

-

(iii) A NonIC encodes an independent speech act (Frey Reference Frey2018: 16, Reference Frey2020a: 30, Reference Frey2020b: 4). To be precise, a NonIC contributes a subsidiary speech act relative to the speech act performed by the host clause (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 30), with implications for both internal and external syntax. As for internal syntax, constituting itself a speech act, a NonIC must be projected to the level of ActP (Frey Reference Frey2018: 27, Reference Frey2020a: 30, Reference Frey2020b: 21). As for external syntax, constituting a speech act subsidiary to another speech act implies that a NonIC will have to be hosted by a speech act, i.e. a constituent projected to the level of ActP (Frey Reference Frey2020a: 30, (79)). By hypothesis, the NonIC is adjoined to the host ActP (Frey Reference Frey2020b: 26 ex. (71)).

Properties (i) and (ii) above follow: being ActP-adjoined, a NonIC cannot constitute the first constituent of a V2 configuration, which would be the specifier of ActP (i), and a NonIC cannot embed (ii).

Frey associates the following additional properties with NonICs (we refer to his papers for evidence from German):

-

(iv) PACs can be coordinated; NonICs cannot be coordinated (Frey Reference Frey2018: 17, Reference Frey2020a: 30, Reference Frey2020b: 26).

-

(v) Both PACs and NonICs allow weak R[oot] P[henomena]’ such as modal particles and sentential adverbials (Frey Reference Frey2018: 27, Reference Frey2020b: 27).

Strong RP such as tags, interjections and hanging topics (Frey Reference Frey2018: 10) are licensed by ActP-adjunction (Frey Reference Frey2018: 52, Reference Frey2020a: 31 ex (39)), entailing that strong RP depend on the presence of an ActP. Consequently, PACs, projecting only to JP, cannot host strong RP. A NonIC, which projects to ActP, may host strong RP (Frey Reference Frey2018: 27, Reference Frey2020a, b).

While properties (iv)–(v) undeniably characterize the specific German NonICs discussed by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b), to whom the reader is referred for discussion, they do not extend to our non-integrated adverbial clauses, i.e. clause types which properties (i) and (ii) single out as non-integrated.

As for property (iv), Frey’s (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) own NonICs cannot coordinate. In contrast, the recycled event modifying CACs we identified as non-integrated can coordinate (thanks to Andrew Radford, p.c., for judgements). The Italian the conditional conjunction se 2b ‘if’ (3c) can introduce a speech event modifying conditional clause; such clauses can be coordinated as in (56).

As for property (v), English tags and hanging topics are strong RP and hence only available when the containing clause projects to ActP (Frey Reference Frey2018: 10). Consider (57). By Frey’s diagnostics (non-embeddability, unavailability as the first constituent in V2), the speech event modifying adverbial clause is non-integrated. However, in spite of non-integration, neither tags nor hanging topics are available in the speech event modifying temporal while-clause, as shown by (57b) and (57c) respectively.

Like CACs modifying the event encoded in the host clause, temporal and conditional clauses recycled as speech event modifiers remain incompatible with argument fronting, a strong RP (Haegeman Reference Haegeman2012: 182 ex. (74)). The relevant English patterns are shown in (58) for a speech event related temporal while-clause and in (59) for a speech event related conditional (see (59a–c)). The a-examples show that argument fronting is ungrammatical in regular CACs, the b-examples illustrate a central adverbial clause recycled as speech event modifier and the c-examples show that in the latter context argument fronting continues to be ungrammatical. Corresponding Italian examples are given in (59d–f).

The above data lead to the conclusion that CACs recycled as speech event modifiers retain their internal syntactic properties and do not acquire properties unique to speech acts. CACs recycled as speech event modifiers were identified as non-integrated but if these recycled CACs belonged to Frey’s class of NonICs, one would expect them to pattern uniformly and to display the internal syntax of NonICs, allowing strong RP.

Frey himself does not discuss the internal syntax of CACs recycled as speech event modifiers. A short note in Frey (Reference Frey2018: 16), reproduced below, merely illustrates the pattern by means of causal clauses (Frey Reference Frey2018: 16 note 13).

Different adverbial clauses which usually occur as CACs or PACs may appear as NonICs in front of or following a V2-clause. This is also prosodically marked. (Frey Reference Frey2018: 16)

Our findings so far lead us to the conclusion that non-integrated clauses are not homogeneous: In spite of the external syntactic property of non-integration, CACs recycled as speech act modifiers differ from Frey’s NonICs.

Following up on the distinction between Frey’s NonICs and our CACs recycled as speech event modifiers in terms of internal syntax, one may then wonder in what way our recycled CACs themselves encode a (subsidiary) speech act, as per the hypothesis formulated by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b) for NonICs. The next section addresses this point.

5.2 Unifying non-integrated clauses

5.2.1 Background: Discourse-syntax and FrameP

Focusing on a specific set of West Flemish V3 patterns, Haegeman & Greco (Reference Haegeman and Greco2018) (also in Greco & Haegeman Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020) elaborate a general framework for patterns in which an initial adjunct combines with a full-fledged V2 clause at a level beyond the sentence-internal syntax. They propose that at the discourse level, the combination of the adjunct and the full-fledged V2 clause yields a discourse unit which they label FrameP:

Importantly, Haegeman & Greco’s FrameP in (60) is not a further extension of Rizzi’s (Reference Rizzi and Liliane1997) left periphery. The proposal echoes similar proposals in the literature. Haegeman & Greco (Reference Haegeman and Greco2018: 36) write:

Our FrameP [in (60)] is like several earlier proposals in the literature, including, among others, Emonds’s (Reference Emonds, Adger, DeCat and Tsoulas2004) DiscourseP, Cinque’s (Reference Cinque, Bonami and Hoffherr2008: 118-9) HP (also adopted in Giorgi Reference Giorgi, Cardinaletti, Cinque and Endo2014; Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2016), Koster’s (Reference Koster2000) P, de Vries (Reference De Vries2009) and Griffiths & de Vries’s (Reference Griffiths and de Vries2013) ParP. (Haegeman & Greco Reference Haegeman and Greco2018: 36)

Haegeman & Greco’s (Reference Haegeman and Greco2018) and Greco & Haegeman’s (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020) approach may be considered an update of Haegeman’s (Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991) orphan analysis of adverbial clauses.

The interpretation of FrameP is explicitized in Greco & Haegeman (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020).

Extending the concept FrameP and its interpretive properties proposed in Greco & Haegeman (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020) can be a fruitful way for unifying non-integrated clauses at a more abstract level. For Greco & Haegeman (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020) the introduction of a FrameP allows the accommodation of an additional speech act whose role is to establish a novel topic by introducing a discourse referent X denoted in their examples by the initial adjunct constituent. Among other things, the discourse referent X introduced via SpecFrameP may be a speech event modifier, that is, an independent referent related to the main assertion as in (61).

The associated root V2 clause constitutes a separate speech act. FrameP thus consists of two speech acts: the illocutionary speech act of assertion, question, etc. contributed by the host clause (‘CP’ in (60), ‘ForceP’ in an articulated CP) and the secondary speech act of frame setting (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1984, Endriss Reference Endriss2009, Ebert, Ebert & Hinterwimmer Reference Ebert, Ebert and Hinterwimmer2014). The speech act associated with FrameP is ‘secondary’ because it is parasitic on the speech act associated with the host clause. SpecFrameP encodes an entity (or a set of entities) in the discourse with respect to which the proposition expressed by the associated (V2) root clause (=CP) is interpreted as relevant.

We now partly reconcile Haegeman & Greco’s proposal with Frey’s hypothesis that a NonIC encodes a subsidiary speech act. Following Greco & Haegeman (Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020), a CAC recycled as a speech event modifier does not itself constitute a speech act, but the recycled CAC is part of the speech act encoded by FrameP. In other words, neither a ‘regular’ sentence-internal CAC in a V2 pattern nor a recycled CAC in SpecFrameP in the V3 pattern constitutes a speech act and hence their internal syntax does not differ. For more discussion of non-integrated clauses see also Haegeman, Lander & Schönenberger (Reference Haegeman, Lander and Schönenberger2021).

6. Summary

The focus of the paper is the observation that adverbial clauses display various readings: An adverbial clause may modify the proposition encoded in the host clause; it may also serve to bring to the fore a contextually salient proposition which serves as a background for the processing of the host clause proposition; or it may function as a modifier of the speech event itself. Haegeman’s early work (Reference Haegeman1984a, Reference Haegemanb, Reference Haegemanc) labelled the former type of adverbial clause as a ‘central adverbial clause’ and grouped the latter two as ‘peripheral adverbial clauses’. In this contribution, we inventorize systematic differences between the first two types of clauses, and we show that the observed differences between these adverbial clauses are replicated with a striking parallelism in the domain of non-clausal adverbial modifiers.

On the basis of these findings we first reexamine two syntactic analyses elaborated in the literature to set adverbial clauses apart, focusing mainly on the treatment of while 2/mentre 2 clauses classified as peripheral. In one approach, the difference between central and peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a clauses is viewed as one of the ‘degree of embedding’, with central adverbial clauses introduced by temporal while 1/mentre 1 being more integrated with the associated host clause than adversative peripheral while 2a/mentre 2a adverbial clauses (Haegeman Reference Haegeman, Chiba, Ogawa, Fuiwara, Yamada, Koma and Yagi1991, Reference Haegeman2009). In another approach, while 2a/mentre 2a clauses are assimilated to non-restrictive relative clauses and it is proposed that these adverbial clauses are orphans, that is, they are not syntactically integrated with the host clause but instead they are combined with the associated clause at the level of the discourse.

We first show that the empirical data challenge the syntactic analyses presented. Crucially, the diagnostics that set apart peripheral adversative/concessive while 2a/mentre 2a clauses from central temporal while 1/mentre 1 clauses also systematically set apart non-clausal epistemic adverbials, such as probably/probabilmente from non-clausal event/proposition modifying adverbials, such as recently/recentemente, as also pointed out in the traditional descriptive literature (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1972, Renzi, Salvi & Cardinaletti Reference Renzi, Salvi and Cardinaletti2001). Given the systematic parallelisms of the adversative while 2a/mentre 2a adverbial clauses with epistemic adverbs, any syntactic analysis of clausal adverbials must be aligned with that of the relevant non-clausal adverbials and a non-integration analysis is not appropriate for the relevant while 2/mentre 2 adverbial clauses.

Our conclusions offer new empirical support for the hypotheses elaborated in Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, b), who, adopting the classification and cartography of adverbials in Krifka (Reference Krifka2017, to appear), aligns the peripheral causal adverbial clauses in German with epistemic adverbs.

In the final part of the paper we turn to the cases in which a CAC is not used as a modifier of the proposition encoded in the host clause but rather is recycled as a modifier of the overarching speech event. These adverbial clauses are shown to be syntactically non-integrated and thus might be expected to pattern with the non-integrated clauses labelled NonIC by Frey (Reference Frey2018, Reference Frey2020a, Reference Freyb). However, while setting the event modifying adverbial clauses apart from PACs is definitely on the right track, we show that the non-integrated speech event modifying clauses do not pattern fully with the NonICs identified by Frey’s own work. Specifically, there is no evidence that recycled CACs are themselves speech acts and would have the internal syntax associated with speech acts. We explore Haegeman & Greco’s (Reference Haegeman and Greco2018) concept FrameP and the interpretive properties associated with it (Greco & Haegeman Reference Greco, Haegeman, Rebecca and Wolfe2020) to unify non-integrated adverbial clauses at a more abstract level. We propose that, while CACs recycled as speech event modifiers are not themselves speech acts, they are integrated at the layer FrameP and thus participate in the subsidiary speech act encoded by FrameP.