Introduction

According to Sugita Genpaku, the magic lantern was first seen in Japan in the late 1760s or early 1770s.Footnote 1 Hitherto regarded by historians as a curiosity of popular culture, the particular timing of the magic lantern's arrival and subsequent spread allows the device to be reconfigured as a novel lens through which to explore some of the defining intellectual trends of the latter Tokugawa period. Most notably, the publication in 1774 of Sugita's own anatomical manuscript, Kaitai shinsho, reflected and influenced newly emerging ideas about nature and the human body. This article will examine the magic lantern's early history in the country as an instance of technology in dialogue with these broader movements of thought. The central meaning that was constructed for the magic lantern in relation to these ideas—that it functioned as a mechanical equivalent of the human eyeball—was significant enough to have had practical consequences in medicine.

The magic lantern was many things in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Japan. Early written references to the device following its initial appearance differ significantly not only in how they contextualize its usage and purpose, but also in the names with which they denote it. The existing literature on the magic lantern in Japan, on the other hand, tends to be relatively restrictive in ascribing its meaning and significance. In part, this narrowness of scope is related to the fact that the magic lantern's history in Japan has only recently become a topic of scholarly interest. Prior to the late 1980s, the only substantive work on the subject was Kobayashi Genjirō’s Utsushi-e, a monograph hand-written and self-published for its 1951, 1969, and 1975 editions.Footnote 2

Yamamoto Keiichi's 1988 book Edo no kage-e asobi, a descriptive examination of the art of shadow puppetry in the Tokugawa era, pre-empted a rise of Japanese scholarly interest in the magic lantern and is one of the most heavily referenced works on the subject. The key significance of the magic lantern in this period, in Yamamoto's eyes, was that it introduced colour into the pre-existing traditions of silhouette-based kage-e (‘shadow pictures’), thus linking them with later forms of projected imagery.Footnote 3 It was also, he notes, an artefact of early nineteenth-century popular culture that, unusually for the period, owed its existence to interaction with Europeans rather than with Japan's Asian neighbours.Footnote 4 The section of Yamamoto's Edo no kage-e asobi that covers the magic lantern, therefore, is bounded by an overarching theme of the acculturation of a Western device to traditional Japanese artistic and performative forms.Footnote 5

While the twenty-first century has seen a slow increase in the attention paid to the magic lantern in Japanese-language academic literature, the English-language historiography remains minimal. Timon Screech dedicates a small portion of his book The Lens within the Heart, an exploration of artistic trends in the Tokugawa period, to the magic lantern, but this is the only English-language monograph to examine the device's history in Japan prior to the Meiji period.Footnote 6 Screech's interest in the magic lantern is framed by its status as an imported Western artistic device in an era in which, he writes, the West ‘represented a new alterative’ to the artistic and philosophical influence of China and, to a lesser extent, Korea.Footnote 7 The device thus forms a small part of a larger narrative in which, through popular art, an associative and non-logical ‘Japanese’ visual consciousness is seen as giving way in the mid to late Tokugawa period to a new way of seeing that was fixed and differentiating, and that constituted ‘a transfer from the European Enlightenment’.Footnote 8

As well as being a product of a lack of research, the limited scope of historiographical approaches to the magic lantern in Japan is also, as Screech and Yamamoto's respective examples suggest, a corollary of the academic specializations of those who have written on the topic since Kobayashi. So far, all have come from a background in the study of visual culture, and increasingly of film history in particular. Their collective interests, as a result, have been in the visual tropes that located the magic lantern within the wider culture of Japanese art and entertainment, and that also linked it to supposedly ‘modern’ or ‘Western’ trends in visuality and perception.Footnote 9 For historians with a specific background in film studies, such as Iwamoto Kenji, Ōkubo Ryō, Komatsu Hiroshi, and Ueda Manabu, the magic lantern is also portrayed as falling within a teleological ‘history of screen practice’ leading through the Meiji era and up to the emergence of cinema and animation.Footnote 10

There are many merits to these approaches, and they are undeniably apt for illuminating those aspects of the magic lantern that were performative, aesthetic, and connected to the misemono (lit. ‘things to see’) culture of the era. Valuable research has already been conducted by the aforementioned authors examining the visual imagery of the magic-lantern show and elucidating several striking connections with later techniques in film projection. At the same time, however, the current set of approaches hold considerable limitations in their ability to help one understand more deeply the factors underlying the usage, development, and contemporary significance of the magic lantern in Japan.

This is because a perspective focused solely on the device's significance within the context of visual culture inadvertently serves to strip away other meanings attached to it by contemporary Japanese. This article will demonstrate that, while many in Japan did see the magic lantern merely as a novelty item, misemono attraction, or piece of Western ephemera, its meaning also stretched far beyond these boundaries. This broader meaning can be described as a technological one, relating not only to what it could do visually, but also how it was used, made, and understood, and, most of all, how it was seen to apply the physical laws of nature within human contexts.Footnote 11 Technology also, crucially, allows knowledge to be tested and re-evaluated, and for new discoveries about nature to be made.Footnote 12 By delving deeper into the history of the magic lantern from this technological perspective, the current study will reveal the device's indelible relationship to contemporary epistemology, the active development and implementation of scientific knowledge, and trends in ways of seeing nature and the human body in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Japan. In so doing, it will also extricate the device from the West-centric and teleological narratives that have defined its history until now, and articulate its greater significance within Japanese intellectual history.

First of all, though, it is necessary to define precisely what is meant by the term ‘magic lantern’, particularly since there was no single expression used by the Japanese for the device in this period. The Japanese-language historiography typically employs the name gentō (‘phantom lamp’) for the magic lantern, except when referring to a domestically produced wooden version, which is labelled utsushi-e (‘projected pictures’). This nomenclature, though it serves the purpose of broadly demarcating the visual styles associated with these two different types, is a potential source of confusion.Footnote 13 The English term ‘magic lantern’ is used in this article both for the sake of clarity and to highlight the essential technological uniformity across all forms of the apparatus. Regardless of contemporary labels or the materials used in their construction, all utilized the same basic components—a boxed light source, mirror, lenses, and glass slides—and all operated on the same principles. These shared elements, which enabled the apparatus to project images from the slides onto a screen, also formed the basis of Japanese intellectuals’ interest in and understanding of the device.

Scientific understanding of nature is a central issue in the early history of the magic lantern in Japan, yet this aspect has gone mostly overlooked. Partly, this omission stems from a more general misinterpretation of the priorities, interests, and motivations of the Rangaku (‘Dutch Studies’) movement. The popular association of the magic lantern with this movement goes back to the late eighteenth century, although this association was not always a positive one. For the writer and shogunal official Hekizentei Kunenbō, for example, the perceived uselessness of the magic lantern symbolized what he saw as the Rangaku scholars’ obsession with arcane ephemera. In 1798, Kunenbō published a satirical kibiyōshi entitled Hōtsuki chōchin oshie shōkei (‘A Short Cut to the Teachings of the Hōtsuki Lantern’) with illustrations by Utagawa Toyokuni.Footnote 14 Part of the book concerns a physician called Hōtsuki-sensei (‘Dr. Hōtsuki’), whose name is likely a pun based on the similarity between the word hōzuki (a species of flowering fruit that resembles a paper lantern, and is thus often known outside of Japan as the Japanese lantern plant) and the name of the prominent Rangaku scholar, Ōtsuki Gentaku.Footnote 15 With a large spherical head capable of projecting light like a magic lantern, Hōtsuki-sensei is depicted in one scene in a classroom imparting to his pupils a succession of esoteric facts connected with Holland: ‘In Dutch, you should be aware, they call a pillow an ōrekyussen, while the word for arse is ārusu.’Footnote 16

One of the two earliest surviving references to the magic lantern in Japan also appears in a kibiyōshi and, like Kunenbō’s later work, here too it is presented as a symptom of a society fixated by empty fads. Muda iki (‘Useless Records’) was penned in 1779 by Koikawa Harumachi, a samurai of the Ojima domain in Sugura province who was stationed in Edo.Footnote 17 In the preface, the oranda zaiku kage-e (‘Dutch trick shadow picture’) is said to epitomize the ‘limitless changes’ taking place within contemporary Edo life as the focus of popular attention flits from one novelty to the next.Footnote 18 For Harumachi, therefore, both the magic lantern and the Rangaku movement with which it was identified held no greater worth than any of the other new fashions of the 1770s, such as the hobby of rearing mice and rats as pets, which he subjected to derision.Footnote 19

Despite criticism in recent years, the prevailing historiographical view of the Rangaku movement continues to rest upon two main perceptions. The first is the idea that one of its defining and formative features was an interest in a specific brand of novelty. Marius Jansen, for instance, paints Rangaku as ‘one of the products of a Tokugawa seclusion system’.Footnote 20 According to this view, the isolationism of the sakoku (‘closed country’) policy built an aura of mystery around the West, which fuelled a fascination for facts and artefacts, however ephemeral, connected to the Dutch.Footnote 21 Inquisitiveness towards the outside world is thus seen as constituting the original and underlying drive which gave shape to the Rangaku movement. By working with Dutch texts, collecting Dutch curios, and, where possible, meeting with the Dutch themselves, these scholars could ‘satisfy their curiosities’.Footnote 22

The second characterization focuses on the movement as both a starting gun for and a herald of later trends of ‘Westernization’ in the nineteenth century.Footnote 23 Beyond novelty, argues Donald Keene, the West was a source of learning and beliefs to replace the increasingly discredited cosmology associated with Classical Chinese learning. Rangaku scholars, he writes, ‘turned to the West not only for mechanical knowledge but for a way of life’.Footnote 24 Moreover, in the works of many historians, this process is portrayed less as a coherent intellectual movement than a reflexive and perhaps even inevitable development in favour of the superior knowledge and products of the West. David Wittner, for instance, writes that, from the early 1800s, ‘Western knowledge flowed into Japan’ and that Western technology soon ‘followed in the wake of Rangaku knowledge’.Footnote 25

These perceptions, however, are highly generalized, and the historical narratives that rest upon them, as a result, ultimately tell us very little about the wider discourse on knowledge in eighteenth-century Japan, or the place of Rangaku within it. References to the magic lantern within the writings of Rangaku scholars are relatively few, but, from examining them, it is nonetheless clear, first of all, that these scholars ascribed far deeper value to the magic lantern than that suggested by either Kunenbō or Harumachi, and, moreover, that they did so in a way that also complicates the existing historical image of the Rangaku movement. Their motivations for seeking ideas across national borders extended far deeper than ‘curiosity’ or nascent urges to ‘Westernization’.

More important than either of the above assessments of the movement was its core concern with the universal laws of nature, and its scholars’ widely shared conviction that nature's internal logic should form the epistemological basis for everything from medical practice and calendrical calculations to moral behaviour and social equality.Footnote 26 The many aspects of this intellectual endeavour—including the need to establish the reliability of knowledge, the importance of the human body as a product of natural principles, and the stress upon the interconnected and universal quality of nature—converged around the technology of the magic lantern. In a way that historians have failed to recognize, the technology was bound not only to the study of the body, and in particular to the eye, but also to the development of an important methodological shift in the epistemological outlook of the Rangaku movement, which allowed deductive reasoning to complement empirical evidence about nature.

In order to delineate the meaning of the magic lantern within this intellectual context, this research adopts an approach that looks for connections between the technology of the magic lantern and the wider discourse on knowledge about nature. The analysis of these connections rests primarily on the written sources of those generally thought of as being part of the Rangaku movement, as well as from a wider set of contemporary texts on subjects such as medicine and magic. This is set within the framework of a broad survey of ophthalmology in Japan during the period under examination, so as to explain how this technology was utilized to overcome theoretical and observational obstacles to a fuller understanding of the eye's complex mechanism. The magic lantern, in this way, becomes an alternative lens with which to disclose the origins of Japanese scientific and medical developments without resorting to the premise of such events being ‘transfers’ from Europe. Through the magic lantern, such critical events in scientific knowledge in Japan can be properly historicized, the impulses behind them understood, and their place within the global circulation of ideas reconceptualized.

Ransetsu benwaku (‘Correcting Errors about the Dutch’)

Few sources help to articulate the value ascribed to the magic lantern by its early contemporaries more plainly than Ōtsuki Gentaku's Ransetsu benwaku, released in two volumes in 1799, the year after the author was parodied by Kunenbō.Footnote 27 The title, which translates as ‘Correcting Errors about the Dutch’, reflects the general aims of the book as Ōtsuki presented them. He framed the text as a simple reference book: a series of titled entries with no other explicit overarching theme than the customs and culture of the people of Holland. Each entry begins with the phrase toite iwaku (‘The question is asked …’), followed by a query, misconception, or rumour about Holland or the Dutch, which Ōtsuki then goes on to answer, rectify, or demystify.Footnote 28

The source's true breadth, though, reflective of Ōtsuki's scholarly interests, covered much more than the state of affairs in Holland. As such, it serves as a corrective to both contemporary and historiographical misunderstandings about the Rangaku movement. The backdrop to the writing of Ransetsu benwaku was the Shirandō (‘Shiba Dutch Academy’), the private school that Ōtsuki established in Edo's downtown Kyōbashi district in 1786, and at which he taught almost 100 students before his death in 1827.Footnote 29 As well as physicians such as Udagawa Genshin and Naka Tenyū, the academy also produced graduates specializing in fields as diverse as world geography (Hashimoto Sōkichi) and the study of India (Yamamura Saisuke).Footnote 30 The multi-layered focus of Ransetsu benwaku, written with input from his students, not only reveals Ōtsuki's way of thinking and the scope of his teaching at the Shirandō, but also embodies a critical and highly influential stage of Rangaku thinking. It reveals a historical moment at which the application of the movement's principles to a wide range of topics was possible, and its epistemological methods were beginning to develop beyond the empiricist parameters that had initially defined them.

Before examining the specific section of Ransetsu benwaku on the magic lantern, it is first necessary to explore in more depth the pivotal discourses running through the text, which not only contextualize, but also actively shaped and stimulated, Ōtsuki's interest in and thinking about the technology. Ōtsuki was born into a family of surgeons in the Sendai domain and became a student of the physician Sugita Genpaku after moving to Edo in 1779 while in his early twenties. Medical matters take up an accordingly large part of the first volume of Ransetsu benwaku, with a particular focus on illnesses, remedial substances, and matters relating to diet. For example, one of the many remedial substances that Ōtsuki described was anastatica, a type of tumbleweed known as the Rose of Jericho, which he referred to both by a transliteration of its Dutch name, rozū hanerego (from roos van Jericho), and its name in Chinese medicine, ansanki (lit. ‘easy childbirth plant’). After ‘considering both Chinese and Dutch theories’, Ōtsuki stated that the Chinese beliefs that the plant helped alleviate pain in childbirth and that it was toxic if not properly prepared were ‘groundless rumours’.Footnote 31

Even this, however, only partially expresses the deeper threads of empiricism, materialism, and universalism that connect the various entries of the book. In the third entry of Ransetsu benwaku, for instance, which is nominally about the ‘frivolous rumour’ that Dutchmen have no heels, Ōtsuki used the eye as a synecdoche for the universality of the human body as a whole.Footnote 32 In doing so, he laid out his understanding of the relationship between the external appearances and the internal workings of the body:

These people [the Dutch] are looked down on as animals either because their eyes are different to ours or because they are from a different continent. It is the case that [the eyes of] people from our country and theirs do look somewhat different in colour. Nevertheless, when it comes to the physical components of the body, there is no difference whatsoever. At no point is the operation of the body any different.

The eyes of the Indian kurobō (lit. ‘black boys’) whom I saw when I travelled to Nagasaki were slightly different to ours, and the Chinese, Koreans, and Ryūkyūans each also have small variations.Footnote 33 Differences in the appearances of the eyes can even be seen between people of Tōō, Hokusetsu, Shikoku, and Tsukushi, all within the same country.Footnote 34 Yet, regardless of colour and appearance, physical function remains the same.Footnote 35

In this way, while ostensibly limiting his criticisms to a selection of specific misunderstandings about the Dutch, Ōtsuki was able to express a far broader intellectual critique. By distinguishing the superficial external differences in appearance from the internal universality of the human eye, and by extension the rest of the human body, he was not only advocating a medical policy, but also taking contentious philosophical and epistemological positions.

From a practical medical perspective, if human anatomy was universal, then treatment should also be standardized and made equal regardless of the person being cared for. This assertion of fundamentally equality, though, was an implicitly provocative position in a country whose system of governance involved entrenched social variegation predicated upon assumed inequality.Footnote 36 Moreover, Ōtsuki's stance also unequivocally challenged existing medical knowledge, much of it directly derived or adapted from Chinese remedial texts and traditions, and as such usually referred to as kanpō (lit. ‘Chinese methods’). In his words, this body of established medical learning ‘did not extend to internal matters’, instead relying ‘solely upon external treatment even when it comes to seasonal afflictions, closed wounds, antenatal and postpartum care, children infected with pox, or strains of measles’.Footnote 37

Ōtsuki's characterization of kanpō as a superficial and specious medical doctrine served the epistemological purpose of advancing his wider criticism of established knowledge. The existing body of knowledge represented by kanpō, as he envisioned it, was built on the unreliable foundations of external appearances. In its place, he wrote, it is necessary to go beyond the skin, hair, and limbs ‘to get to the internal organs, veins, arteries, muscles, and membranes’, and ‘to first know the whole of the human body in its natural state’, before one can practise medicine. As with medicine, Ōtsuki suggested, so with other matters of understanding nature.Footnote 38 True knowledge could only be obtained by first questioning both established facts and the external appearances upon which they were based, and then verifying or invalidating these through the observation of internal workings.

Of the magic lantern itself, Ōtsuki first described the uncanny visual effects that it produced, noting that the projected images ‘appear the size of a human and look as if they are alive’.Footnote 39 He referred to the device as a kage-e tōrō (lit. ‘shadow lantern’), but also observed that ‘In Holland, it is called a tōfuru rantāru [from the Dutch toverlantaarn], which means yōtō [lit. “supernatural lamp”]’.Footnote 40 Behind this supernatural façade, however, Ōtsuki found a scientific explanation:

A hole is made in the front of a specially positioned box with a lamp inside. When glass with an upside-down and back-to-front image drawn on it is placed in this opening, the image is reversed and a non-inverted image is projected onto the cloth hanging opposite. The image is also enlarged.

The object is as an eyeball. This is the same principle by which the eye reflects and forms within itself all creation. It is simple to understand if one examines the device and identifies this principle.Footnote 41

Outwardly, Ōtsuki suggested, the way that the magic lantern manipulated light seemed supernatural, at one point even to the Dutch themselves: ‘The name yōtō likely comes from people who were ignorant of this principle, and therefore could not explain it.’Footnote 42 It was only through a process of mistrusting outward appearances and looking internally, he advocated, that one could decipher the device's natural principles and understand the true reality of its workings.

The central idea of Ōtsuki's entry on the magic lantern in Ransetsu benwaku, though, was his conception of the device's relationship to human anatomy.Footnote 43 For Ōtsuki, the answer to how the magic lantern could produce coloured images that ‘look as if they are alive’ was that the device functioned as a mechanical replication of both the essential structure and underlying principles of the eye itself. Within this analogy, the parts of the magic lantern were likened to the components of sight. The screen, the glass lens, and the illustrated slide became, respectively, the retina, the crystalline lens, and the object being viewed.

By anthropomorphizing the device in this way, and describing it as ‘as an eyeball (manako)’, Ōtsuki was also mechanizing the body.Footnote 44 Conceptually, the eye became a piece of apparatus. Not only could a comprehension of the eye be approached through an analogous dichotomy of external and internal; Ōtsuki proposed that the eye could be understood through observing the magic lantern. By examining the device, he commented, one could comprehend ‘the same principle by which the eye reflects and forms within itself all creation’.Footnote 45 It was this technological aspect, grounded in the practical application of scientific knowledge, which defined the core value and meaning of the magic lantern within this intellectual movement. It offered Ōtsuki, and other Rangaku scholars, a working model with which to test and evaluate theories about the mechanisms of vision. In short, by simulating the eye's internal workings, the magic lantern made them external and observable. Looked at from this perspective, the timing of the arrival of the device in Japan gains especial significance within the study of optics and the human eye.

The problems of observation in ophthalmology

The early history of the magic lantern straddled that of the wider endeavour to understand human vision and its maladies. The workings of the eye were of special interest to Rangaku scholars, with many of the most significant texts produced by the movement either dedicated to or touching heavily upon ophthalmological matters. This focus on the eye had an underlying medical rationale. Eye conditions and diseases were among the most debilitating of all ailments, as well as being one of the most familiar to both doctors and citizens in Tokugawa Japan. The blind also had a notable public presence in such cities as Edo and Kyoto, where many engaged with wider society as musicians, entertainers, masseurs, and moneylenders, and were represented through their own prominent guild, the Tōdōza (‘Guild of Our Way’).Footnote 46 As well as being widespread among the general population, issues with eyesight were particularly prevalent among scholars, and early retirement due to failing vision was common.

Nevertheless, the particular interest in sight and vision within the Rangaku movement cannot be separated from its epistemic concerns about verified and unverified information. One of the central concepts around which the movement formed was that of jikken, meaning observation, or literally ‘seeing reality’. Under the influence of scholars from the School of Ancient Medicine (Koihō), most notably Yoshimasu Tōdō and Yamawaki Tōyō, early Rangaku figures such as Sugita Genpaku had concluded that direct visual observation was the only sound basis for knowledge. Faced with a ubiquity of medical and scientific texts containing what Yamagata Bantō called ‘the errors of the ancients’, jikken was considered the only reliable means of separating these errors from the truth.Footnote 47

For a movement focused upon re-examining and validating knowledge in this way, it became of primary importance that they comprehend the workings of their chief means of authentication: the eyes. As Rangaku scholars began to trust more in first-hand observation through the procedures of scientific observation, their limited knowledge of how the human eye works seems to have produced a lingering epistemological uncertainty that, in turn, directed investigative energy towards ophthalmology. The accuracy of the vision of the human eye thus became an issue intertwined with questions about the reliability of knowledge, and an understanding of how the eyes render reality gained special status as an area of medical investigation.

In kanpō, by contrast, little attention was typically paid to sight and vision per se, and the eyes were primarily seen as a way of diagnosing deeper medical issues. Complaints such as bloating and excessive flatulence, for instance, were diagnosed by identifying the symptom of ‘itchy eyes’ in a patient. Each of the external parts of the eye was considered to be linked to an internal organ: the pupil to the kidneys, the iris to the liver, the upper eyelid to the stomach, the lower eyelid to the spleen and bladder, the sclera to the lungs, and the lacrimal caruncle to the heart. An ailment affecting an internal organ, it was believed, would manifest in its respective part of the eye.Footnote 48

Beyond this diagnostic use, however, the eyes were not particularly valued as an object of medical study.Footnote 49 The structure and receptive component of the eye was understood to be limited to that which was in evidence externally. Depictions of the eyes in kanpō texts were two-dimensional and were typically either elliptical or teardrop-shaped, with the eyelids occasionally shown as holding the disc of the eye in a pincer-like grasp.Footnote 50 Although they lacked a conception of the three-dimensional physiology of the eyeball, by the eighteenth century, ophthalmologists were nevertheless able to perform some complex procedures, such as cataract couching using a needle. Yet, general theories on the causes of disorders of the eye tended to be abstract or moralistic ones, such as the idea that declining eyesight was caused by sexual excess, or that blindness was divine punishment for selfish acts, rather than biological explanations.Footnote 51 Prior to the wider paradigmatic shift towards conceptualizing the human body as having an interior machine-like structure, and thus working in accordance with constant and universal physical principles, the eye fell within the same metaphysical and symbolic system as the rest of the body.

An early swing away from the orthodoxies of kanpō doctrine came with the publication in 1742 of Negoro Tōshuku's Ganmoku gyōkai (‘Understanding the Eye’), containing the first reference to the three-dimensional eye in a Japanese text. Circumventing the ban on human dissection, Negoro, a Kyoto physician, had made detailed sketches of the bodies of two executed criminals that he found dumped outside the city in 1732, and, in 1741, he published his primary findings as a series of illustrations and notes on the human skeleton.Footnote 52 This experience, alongside the opportunity for close observation of the eye while performing cataract surgeries, inspired him to put forward a new theory of vision. In Ganmoku gyōkai, Negoro hypothesized that ‘divine water’ (jinzui) circulated within the spherical eye and that blurry vision is caused by disturbances to the flow of this water, while cessation of circulation caused vision to be lost altogether.Footnote 53

A markedly more influential event for the field of ophthalmology, though, was the publication in 1774 of Sugita Genpaku's Kaitai shinsho (‘New Book on Anatomy’). The book was primarily based upon a single European source: an anatomical textbook entitled Ontleedkundige Tafelen (‘Anatomical Tables’), which was itself a 1734 Dutch translation undertaken by Gerard Dicten of Johann Adam Kulmus's 1722 German text Anatomische Tabellen.Footnote 54 In 1771, Sugita and Maeno Ryōtaku had taken copies of Dicten's translation with them when, along with Nakagawa Junan, they were given rare permission to witness an eta, a member of an outcast group, carry out the dissection of a 50-year-old woman who had been executed at the Kozukappara keijō in north-eastern Edo.Footnote 55 Observing that the woman's internal organs matched the illustrations in Ontleedkundige Tafelen, the group decided to collaborate on a full translation.Footnote 56 Like virtually all subsequent Rangaku texts, though, Kaitai shinsho shows considerable variations from the original. While much of the lay-out and content remain the same, certain elements, including all of Kulmus's footnotes, are omitted in the Japanese text.Footnote 57 Moreover, while the anatomical figures as they appeared in Ontleedkundige Tafelen were reproduced exactly, four additional illustrations depicting the physiology of the hands and feet were duplicated from another medical text, Govard Bidloo's Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams (‘Dissection of the Human Body’), first published in 1690.Footnote 58 Consultation and interpretation of other sources besides Ontleedkundige Tafelen were evidently a significant part of the process of composing the finished text.

In copying Kulmus's illustrations, Kaitai shinsho showed its Japanese readers for the first time the physical three-dimensional structure of the human eye (Figure 1). Sugita, with input from Maeno and Nakagawa, devised a set of entirely new words to represent those newly discovered components of vision that lay beneath the surface. Sugita identified the retina as the receptive component in vision and described the rest of the eyeball as being mainly composed of eki, meaning literally ‘fluid’ but here broadly denoting the refractive elements of the eye, including the clear gel of the vitreous humour that fills the main cavity of the eyeball; the watery liquid of the aqueous humour in front of the lens; and the elastic protein structure of the crystalline lens itself.Footnote 59 For the vitreous humour, Sugita used shōshiyoeki (lit. ‘glass-like fluid’); for the aqueous humour, suiyoeki (lit. ‘water-like fluid’); and for the lens, suishōeki (lit. ‘crystal fluid’).Footnote 60 ‘The image inside the eye,’ Sugita wrote, ‘is things being projected through the eki onto the retina.’Footnote 61 For the retina itself, Sugita used the word ramonmaku, meaning literally ‘thin imprint film’, further emphasizing its role as a receptor onto which the rest of the eye's components cast an image of reality.Footnote 62

Figure 1. Sugita Genpaku, Kaitai shinsho, 1774, vol. 1, p. 8. The three illustrations at the bottom of the page depicting the internal eye are labelled, left to right, as follows: ‘The whole form of the eyeball’; ‘Blood vessels seen with the membrane pulled back’; ‘Each eki seen with the eye cut open’. Source: Waseda University.

In the section of Ontleedkundige Tafelen on the eyes, Dicten had referred to the retina by the Dutch word netvlies, the Greek word amphiblestroides, and the Latin word retina.Footnote 63 Each of these refers to the netlike formation of the blood vessels on the back of the eye. Sugita, however, chose ramonmaku as a term that allowed readers to visualize the receptive function, rather than merely the appearance, of the retina. This example reveals Sugita's process of creating new terms that expressed his understanding of the physical nature of human anatomy using familiar concepts, as well as the extent to which he was willing to move away from direct translation where a method of critical and interpretive reworking was more appropriate to his aims. This method, as much as the content of the book, had a profound impact upon the Rangaku movement.

The half-century following the publication of Kaitai shinsho represents a crucial point in Japanese medical science, where dissection had begun to reveal more accurately the form of human anatomy, but not necessarily to explain how the body worked. Physicians familiar with Kaitai shinsho and subsequent similar Rangaku texts started to conceive of a human interior with parts systematically ordered like those of a machine, but in many cases with an understanding of their respective processes that remained vague. Sugita's representation of vision in Kaitai shinsho exemplifies the gulf between describing the physiology and muscular movements of the eye and apprehending the mechanisms of sight. He was able to describe the visual components, yet, without a comprehension of optical theory and the behaviour of light, could only vaguely describe that they somehow worked together to ‘project’ an image onto the retina. The central role of the lens in this process, in particular, was left unacknowledged.

Understanding the complex visual system of the eye presented an especially difficult challenge for medical scholars following the publication of Kaitai shinsho. Even after dissection revealed the interior anatomical structure of the eye, a key element in its workings remained invisible. Vision depends on the precise refraction of light through the lens of the eye and onto the retina, yet the process is at the same time imperceptible to the eye. Unlike the pumping of blood by the heart, in other words, ocular refraction could not be viewed directly. The Rangaku movement's stress on knowledge that could be evaluated and verified through observation, therefore, came up against a significant hurdle when it came to vision itself. Since the mechanisms of the eye could not be observed by the eye, the principles along which it worked had to be examined and demonstrated through substitute devices.

Optics and the magic lantern

The introduction and increasing use of the magic lantern in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries coincided not only with the development of a materialistic rather than metaphysical understanding of nature and the human body, but also specifically with the development of optical theory in Japan. In view of this, it is noteworthy that an envisaged connection between the eyes and the optical device was present in some of the earliest Japanese writings about the magic lantern. Through looking at the language and context of these references, it becomes apparent that Ōtsuki's conception of the device ‘as an eyeball’, and by extension the eyeball as a magic lantern, was not an entirely original idea, but rather the evolution of a pre-existing one.

One of the two oldest surviving references to the device in Japanese—the other being Koikawa Harumachi's aforementioned Muda iki—is the three-volume book of magic tricks, Tengu-tsu (‘The Goblin's Nose’), published in Osaka in 1779 by the prolific chronicler of magic tricks, Hirase Hose.Footnote 64 In Tengu-tsu, Hirase provided a description of the magic lantern under a section entitled ‘A Trick for Displaying the Spirits of the Dead’:

A thing called a kage-e megane can be found in megane-ya. You should try it. It projects various figures. When any image is placed into the megane in the box, that image can then be viewed on whatever you project it onto …. Last year it was shown as misemono in Naniwa's new district (Shinchi), and, since it was not easy to see that show, I will describe it here with the help of the following diagrams.Footnote 65

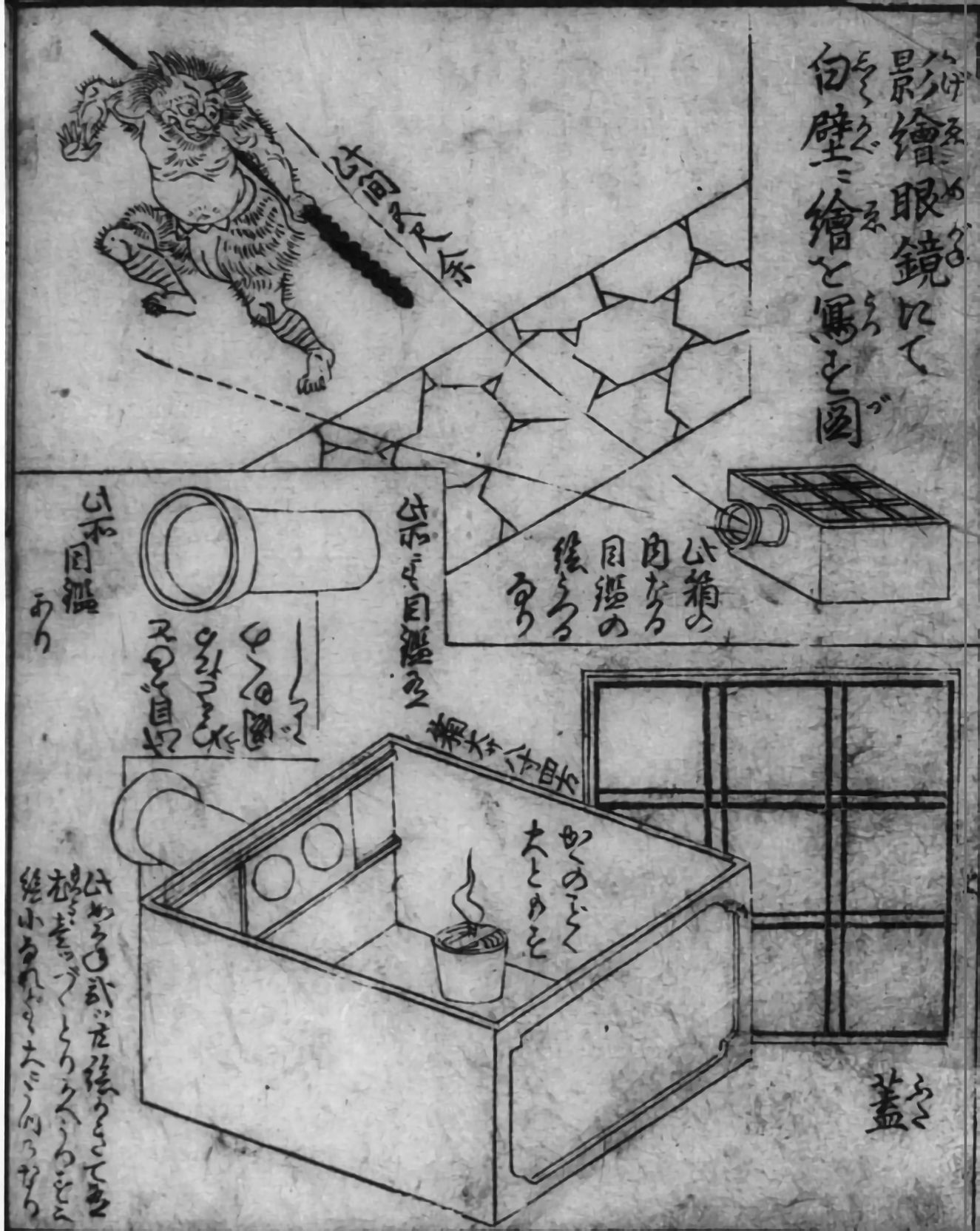

The first illustration that follows shows a magic lantern with a tube extending from its front and two diverging lines that represent the projection of light from this source onto the opposing wall, upon which a life-like image of an oni—a folkloric creature similar to an ogre—is produced. Underneath, a diagram details some of the basic components inside the device, including a candle and a slot into which the glass slides were placed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hirase Hose, Tengu-tsu, 1779, vol. 2, p. 6. Source: National Diet Library.

The recurring word in Hirase's description of the magic lantern is megane, conventionally meaning ‘eye glasses’, although it is clear that he applied the term with a much broader association. When, for example, Hirase referred to a component inside the device called the megane, into which ‘the image is placed’, he was specifically denoting the lenses.Footnote 66 In this sense, Hirase's name for the magic lantern, kage-e megane, might be translated as ‘shadow picture lens’. Hirase also commented, however, that the device was sold in megane-ya. To broadly define megane-ya in the same manner—that is, as shops that sold devices with lenses—is to minimize the fact that the original and principal trade of these shops was as dispensing opticians. These businesses had first appeared as spectacles became commercially available in the seventeenth century and led to the gradual expansion of a network of expertise and commerce through which other lensed devices, such as magnifying glasses, sunglasses, and telescopes, were imported, traded, studied, and reproduced in the eighteenth century.Footnote 67 By the 1770s, according to Hirase, magic lanterns too counted among the stock sold in the megane-ya of Osaka and Edo.

The fact that magic lanterns were commonly sold in opticians’ stores created opportunities for the development of the idea that the device and the eye were governed by the same set of natural laws. For those whose chief interests lay elsewhere, such as Hirase, the term megane may have simply offered a catch-all label for the increasing variety of lensed devices at a time when their physical mechanism was not well understood. Nonetheless, it was a label that explicitly linked these often-complex contraptions to the fundamental convex or concave lenses that Japanese opticians had been using to correct eyesight on a significant scale since at least the 1730s. For those physicians and researchers who in the late eighteenth century were trying to build upon the achievement of Kaitai shinsho, therefore, a foundational bridge between technology and ophthalmology had already been built.

The terminology used to refer to the magic lantern remained in flux into the nineteenth century, with numerous other terms used alongside kage-e megane. A considerable bulk of these, though, were linked either to visual optics through the word megane or to the optics of light more generally.Footnote 68 Morishima Chūryō, for instance, in compiling his 1798 Japanese-Dutch dictionary, Bango-sen (‘Language of the Barbarians’), gave first a relatively literal translation of the Dutch word for the magic lantern: toverlantaarn. Transliterating this word as ūfuru rantārun, Chūryō used for its Japanese equivalent characters for shōkontō, meaning ‘devil-summoning lamp’.Footnote 69 However, he attached to this translation a note that the word should not be read as shōkontō, but rather ekiman-kyō, reflecting a popular name of the device in Edo.Footnote 70

The first part of this name for the magic lantern appears to refer to an individual named Eijkman, rendered in Japanese as Ekiman. Although Eijkman's full identity is unclear, it is possible that he was a Dutchman through whom one of the early magic lanterns in Edo was acquired.Footnote 71 More pertinent, however, is the second part of the term: kyō, a word that had originally meant ‘mirror’ but, during this period, came to mean ‘lens’ when used in the context of physics. Like megane, this appellation also appears in various sources. Sugita Genpaku, for example, used the term genyō-kyō, a word that is difficult to translate into English but which means roughly ‘lens of reality and the supernatural’.Footnote 72 Again, the centrality of the word kyō signifies that the lens was commonly understood among scholars to be the key component of the magic lantern.

With his description of the magic lantern in Ransetsu benwaku, Ōtsuki Gentaku's key step was to make the link that, if the lens was the most important element in enabling the device to project an image, then a similar lens could also be the core focal component in the human eye, allowing it to form an image in the same way. Even this, however, was not entirely new by the late 1790s. Ōtsuki's fellow Rangaku writer and painter, Shiba Kōkan, explained in his 1795 book, Oranda tensetsu (‘Dutch Astronomical Theories’), that behind the pupil of the eye is a thing ‘which is like a lens (kyō), and which reflects and shifts in the way that water does when one faces it’.Footnote 73 Without naming it, he wrote that its substance was ‘like glass’.Footnote 74 Moreover, like Ōtsuki, Kōkan also made a connection between the eye and lensed devices. ‘The people of the West,’ he wrote, ‘have comprehended the eye, and make megane in accordance with the example of its natural action.’Footnote 75 Kōkan does not, however, overstate this connection. He saw this crucial but unnamed component of the eye as being like glass but also like water, and therefore having no precise manmade equivalent. The structure and workings of the eye were ‘a basis for the manufacture’ of megane, without necessarily being characteristics that could be reverse engineered and mechanically reproduced wholesale.Footnote 76

For Ōtsuki, by contrast, the behaviour of light through both the lenses of the magic lantern and the optical lens of the eye was not merely analogous, but practically identical. The device operated like the human eye, and vice-versa. The magic lantern focusing the image from a slide onto a screen was a literal external replication of the way that the internal system of the eye focused an image of ‘all creation’, to use Ōtsuki's words, onto the retina.Footnote 77 Thus, since the pictures on the glass slides used in the device were reversed in the process of being projected onto the screen, he wrote, the same process logically occurs within the eye. The image reaches the retina upside-down and back-to-front.Footnote 78 Whereas Kōkan acknowledged the limits of dehumanizing and mechanizing the body, alluding to the intangibility of both the eye's peculiar anatomy and the gi (‘energy’) that he believed passed through the eye to form vision, Ōtsuki tended to push such complications aside in pursuit of a comprehensively materialistic understanding of nature.Footnote 79

A deeper understanding of the eye

The exact structure of the eye is not laid out in detail in Ransetsu benwaku. In 1798, however, the year prior to its publication, Ōtsuki had completed a draft of his most ambitious work, a full revision of Kaitai shinsho. It would not be until 1826, the year before Ōtsuki's death, that his new edition, Chōtei kaitai shinsho (‘Revised New Book on Anatomy’), was fully completed and published.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, with his 1798 draft, Ōtsuki had already transformed the five relatively slim volumes of Sugita's primer into a manuscript on the workings of the human body that was far more expansive than either that work or Kulmus's original text.Footnote 81 What is more, among the enormous mass of medical information in Ōtsuki's revised edition that did not appear in its predecessors, there was also a new account of what he called ‘the true principles of seeing with the naked eye’.Footnote 82

Into Sugita's somatic rendering of the observable surgical anatomy of the eye, Ōtsuki here interposed a conception of light as having a similarly concrete and tangible physical structure that the human eye imperceptibly manipulates to form vision. Central to the act of seeing, Ōtsuki wrote, is ‘the substance of light’ (kōmyō no karada): ‘This substance is a pattern of regular rays… It is a strange substance which can bend in many ways when shone through a lens.’Footnote 83 Ōtsuki incorporated new concepts and parts of the eye in his description to match the centrality and physicality of light expressed in his explanation. He went into depth, in particular, on the form and function of the crystalline lens. The suishōeki (‘crystalline lens’) is in the form of a nakadaka-kyō (‘convex lens’), he wrote, which bends incoming rays of light as they ‘penetrate the heart of the lens’.Footnote 84 It possesses the characteristic of kusshin (‘elasticity’), allowing it to adjust when viewing near or far objects.Footnote 85 The most common disorders of vision, he noted, are the result of variations in physiology that affect this process.

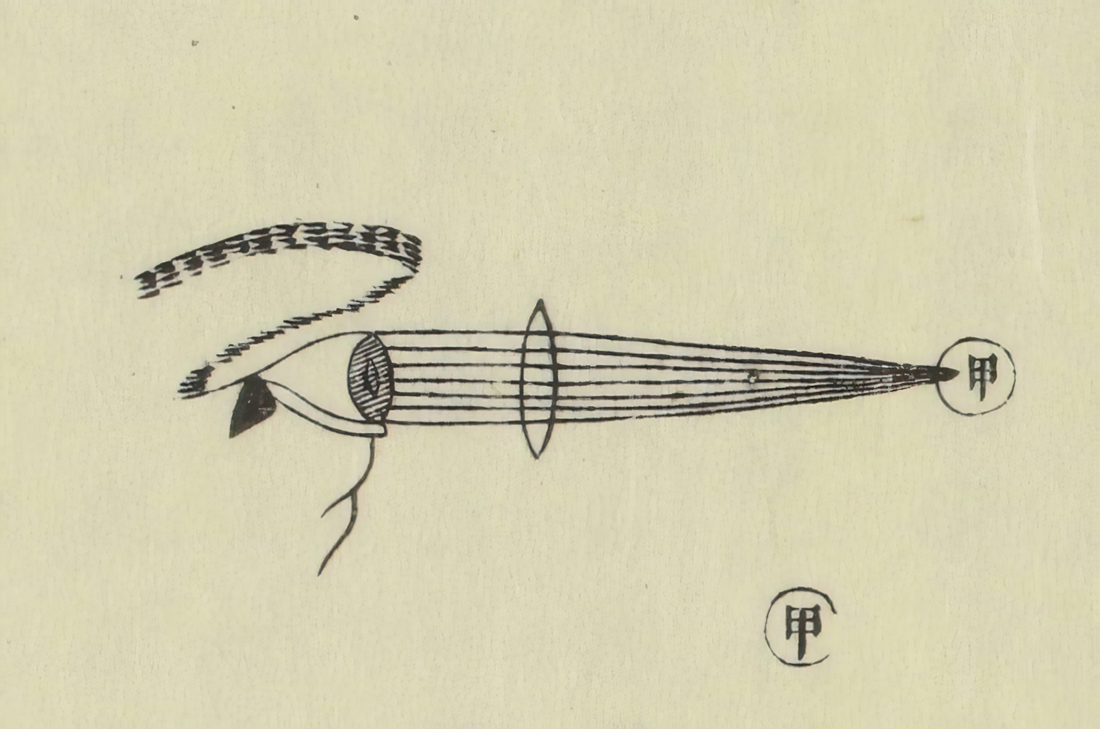

The sole illustration embedded in the main text of Chōtei kaitai shinsho served to help elucidate this complex principle of light as ‘a pattern of regular rays’.Footnote 86 In a similar way to Hirase's use of diverging lines to visualize the projection of the image outward from the magic lantern in his 1779 diagram, Ōtsuki's illustration depicts light as directional geometric lines (Figure 3). Entitled ‘Object through a lens: Diagram of entering the eye in parallel’, it shows what he described as ‘three rows’ of light rays diverging as they reflect off an unspecified object located a short distance away, then being focused by a glass lens into the eye.Footnote 87 The lens inside the eyeball, he noted, could similarly alter light from ‘triangular rays’ (i.e. converging or diverging rays) to ‘parallel rays’, and vice-versa.Footnote 88 In giving light physical representation on the page, Ōtsuki thus imbued it with the status of a physical substance, albeit a ‘strange’ and malleable one.

Figure 3. Ōtsuki Genpaku, Chōtei kaitai shinsho, 1826, vol. 5, p. 24. Source: Waseda University.

In this way, the eye's mechanism was shown as depending chiefly upon the precise interaction of one substance—light—with another—the crystalline lens. While the form of one could be seen only through dissection and the other only through experimental observation, the materiality and physical qualities of both were emphasized. Light was, in other words, a mechanistic component in the overall system of the eye. By transforming the workings of the eyes from an abstract process to a tangible one, Chōtei kaitai shinsho presented the act of seeing as an entirely materialistic concept as opposed to a metaphysical one. The question of how faithfully the human eye captures reality thereby became a mechanical one, with Ōtsuki suggesting that, so long as the interior mechanism operated correctly, the reliability of vision was self-evident.Footnote 89 A lens could bend light, but it could not violate the constant and universal principles that underpinned it as a material structure.

Ōtsuki's conception of the eye in this manner was subject to a number of influences beyond his investigations into the magic lantern. Although, like Sugita, Ōtsuki consulted a wide range of both Dutch and Chinese texts, some of his most significant influences likely came from other Japanese texts published around the time that he was working on Chōtei kaitai shinsho. In 1794, Ōtsuki had obtained a copy of Martinus Pruys's Verhandeling over de oogziekten (‘Treatise on Ophthalmology’), a 1787 Dutch translation of J. J. E. Plenck's Doctrina de morbis ocularum.Footnote 90 He had been given the text by Katsuragawa Hoshū, a shogunal physician whose prominent position allowed him opportunities for in-depth discussions with the Dutch when they came to Edo to pay homage to the shogun.Footnote 91 The final translation was undertaken by Sugita Ryūkei, one of Ōtsuki's pupils and son of Sugita Genpaku.Footnote 92 Ōtsuki was, therefore, primarily a middle-man in this process, having neither procured the text first-hand nor taken direct responsibility for its translation. Nevertheless, the resulting Japanese medical manuscript, Ganka shinsho (‘New Book on Ophthalmology’), owed part of its existence to Ōtsuki and he would undoubtedly have been aware of the new knowledge contained within it.

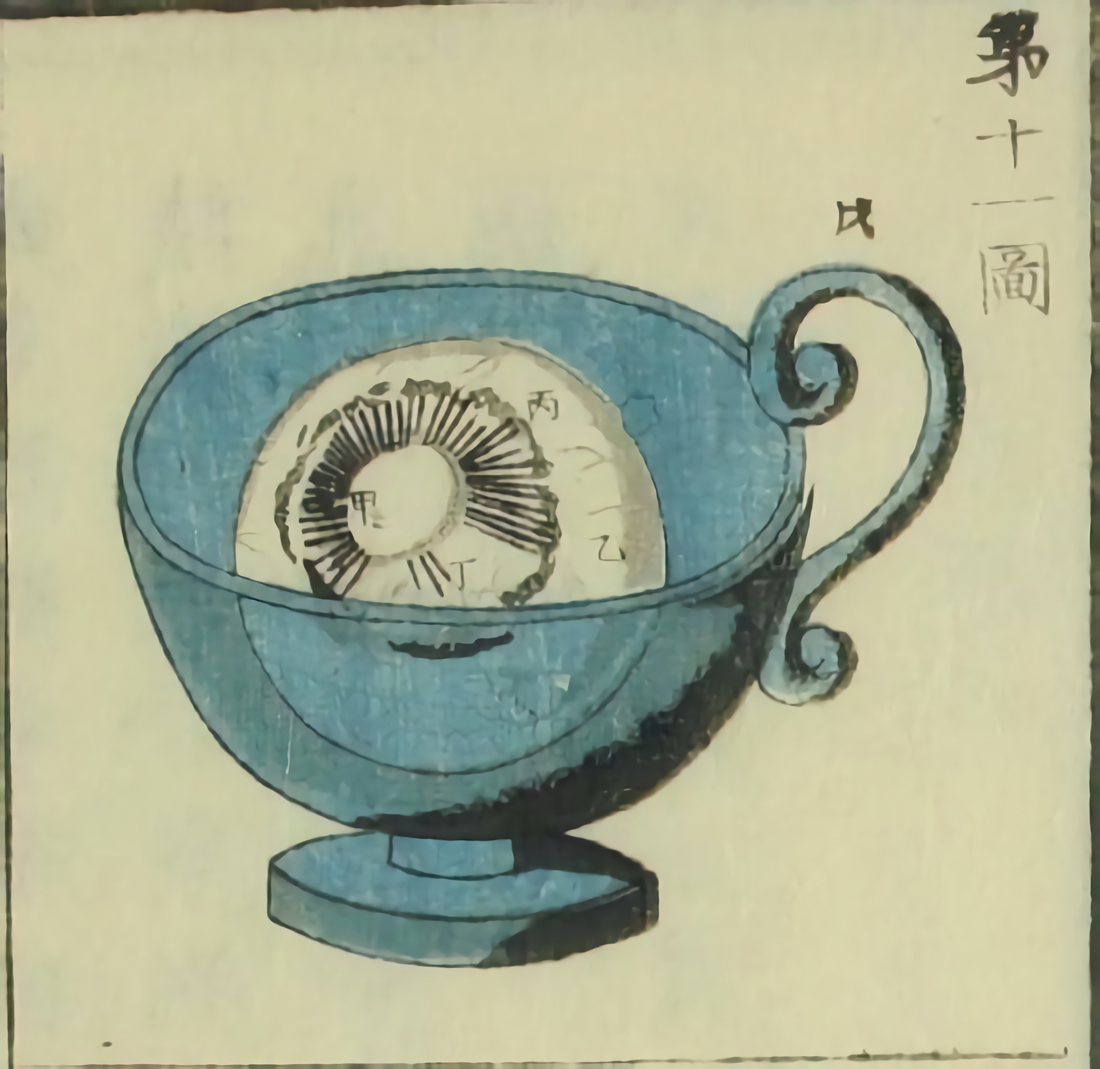

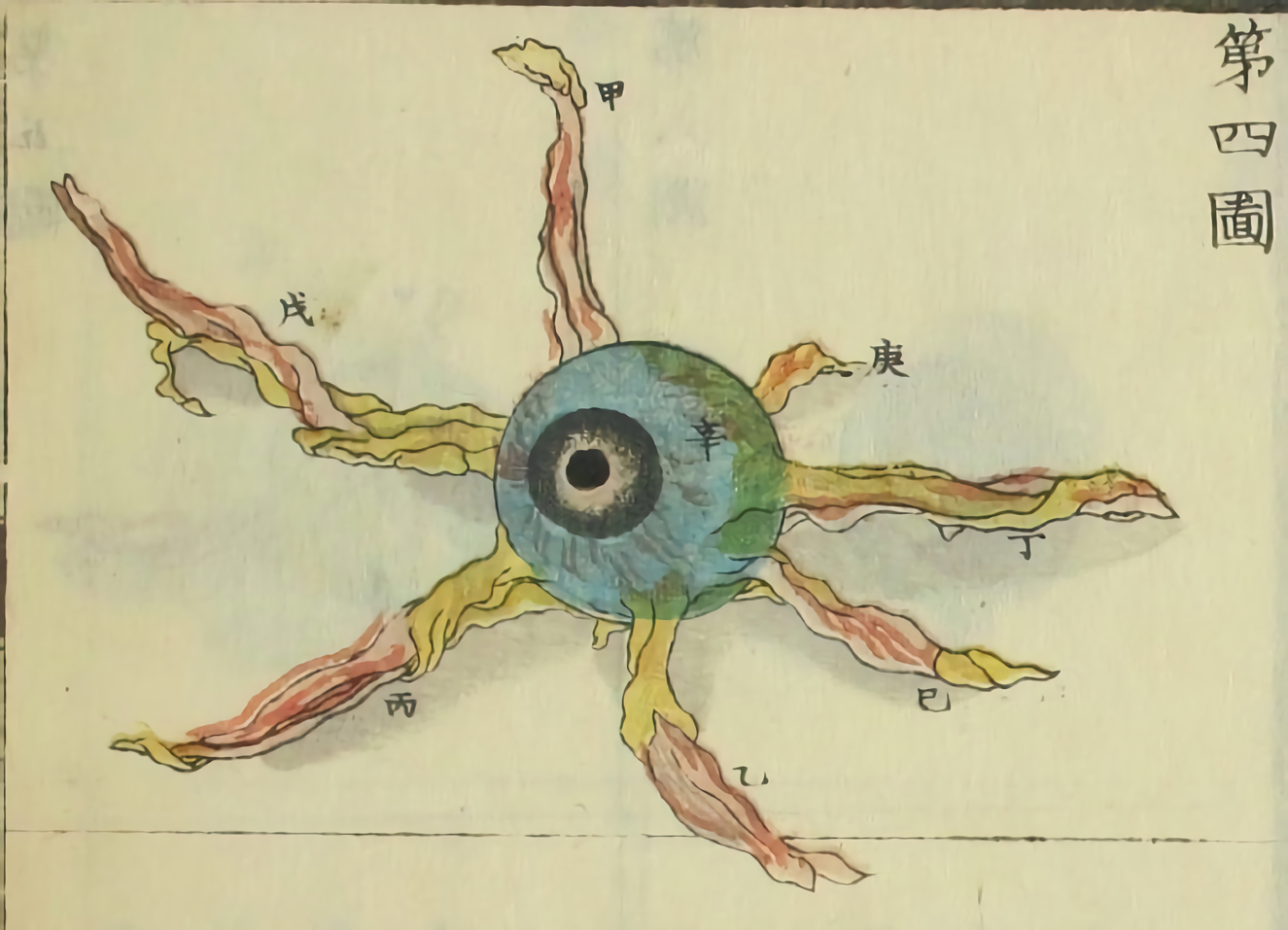

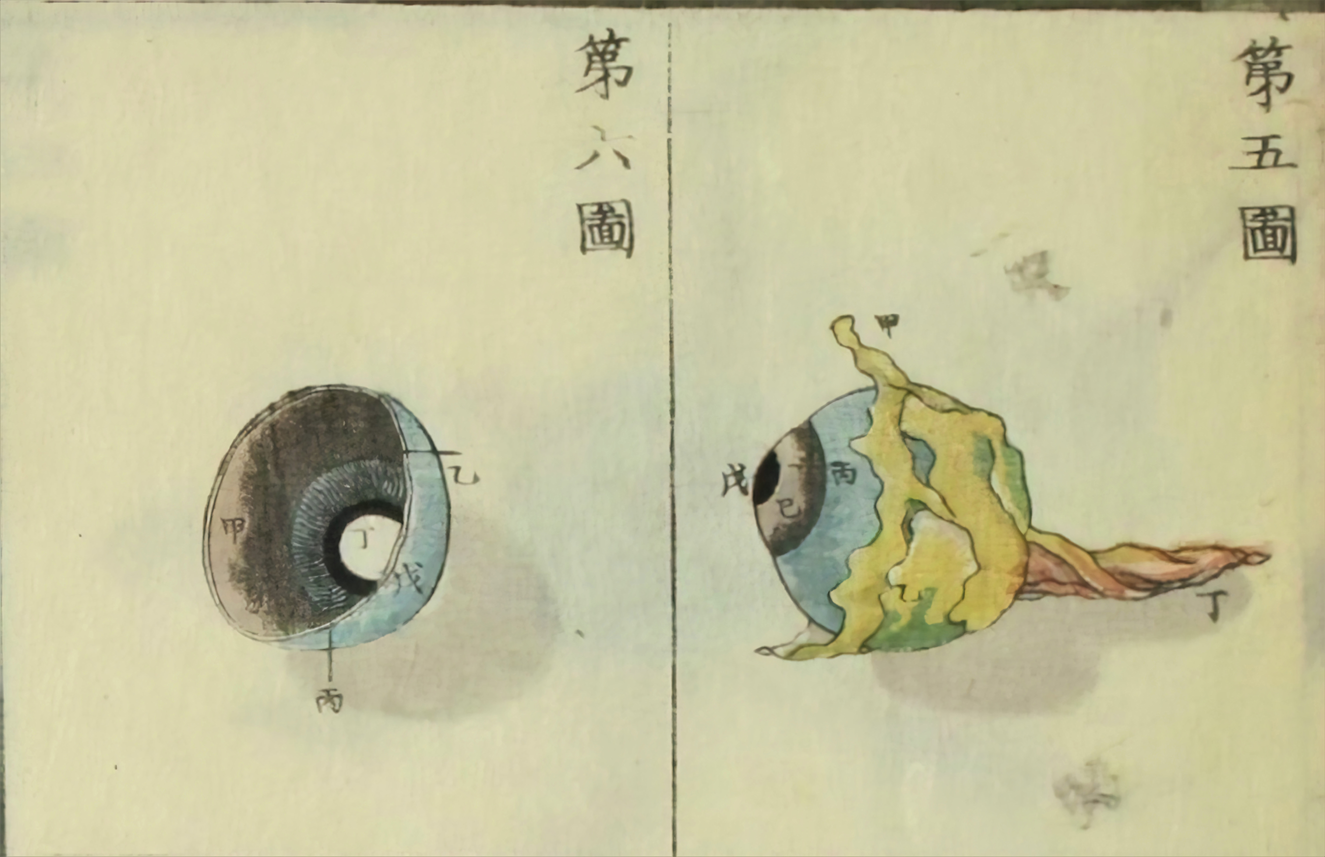

It took until 1815 for Ryūkei to complete Ganka shinsho, by which point it was a conspicuously different work from its original source.Footnote 93 Ryūkei had Ishikawa Tairō, a retainer to the shogun, provide original illustrations based on Ryūkei's first-hand dissection of several eyeballs and his observation of their interiors through a microscope (Figures 4–8).Footnote 94 These illustrations show that Ryūkei segmented the eye precisely and in a variety of ways, uncovering and examining features that had not previously been documented in Japanese medical literature. This dissection formed the basis of an extended process not only of translation and interpretation, but also of scrutiny, clarification, and verification.

Figure 4. ‘Through a container, the connection of the lens and the vitreous humour, and also the part of the ciliary muscle connected to the ciliary body’, Sugita Ryūkei, Ganka shinsho, 1815, vol. 1. Source: Waseda University.

Figure 5. ‘The six muscles of the eyeball’, Sugita Ryūkei, Ganka shinsho, 1815, vol. 1. Source: Waseda University.

Figure 6. Left: ‘A view of the inner surface of the front part of an eye cut in half’. Right: ‘The white membrane of the eyeball with the six muscles detached’, Sugita Ryūkei, Ganka shinsho, 1815, vol. 1. Source: Waseda University.

Figure 7. Left: ‘The reverse side of an unfolded uvea seen through a microscope’. Right: ‘A view of the inner surface of the back part of an eye cut in half’, Sugita Ryūkei, Ganka shinsho, 1815, vol. 1. Source: Waseda University.

Figure 8. Left: ‘The three ekis [humours] of the eye cut front-to-back’. Right: ‘The retina with the choroid coat detached’, Sugita Ryūkei, Ganka shinsho, 1815, vol. 1. Source: Waseda University.

One of the elements of the eye that Ryūkei dissected and examined was the uvea, comprising the iris, choroid, and ciliary body (Figure 7). This required carefully removing the sclera, the white of the eye, in order to view the choroid and ciliary body underneath and, as such, had been beyond the capabilities of the those who had previously performed dissections in Japan. In Pruys's translated text, little time was spent describing the form and function of the uvea, which he referred to both as uvea, a word that derives from the Latin word uva, meaning ‘grape’, and as druivenvlies, meaning literally ‘grape layer’.Footnote 95 Ryūkei, by contrast, included an illustration of a dissected and ‘unfolded’ uvea, depicted its constituent parts, and explained how it works to control vision ‘by means of the accumulation of an intricate sequence of many minute movements’.Footnote 96 Rather than directly translating Pruys's nomenclature into Japanese, Ryūkei also chose the word futomomo-maku (‘rose-apple film’) for the uvea, possibly alluding to a similarity between the shape of the dissected uvea when laid out flat and the futomomo (‘rose-apple’) fruit when split in half.Footnote 97

Ryūkei's efforts exemplify the common methodology of translators within the Rangaku movement, which was to view the text being interpreted as a basis for testing knowledge, rather than a direct and reliable source of knowledge in and of itself. By adopting an approach based on both first-hand observation of the eye and interrogative translation of Pruys's text in this way, Ganka shinsho was the most significant purely ophthalmological text of its era. It gave new clarity and detail not only to the structure of the eyeball, but to the way that its parts and the surrounding muscles move in synchrony in response to different conditions.Footnote 98 What Ryūkei did not elucidate, however, was the role of light in producing vision. His book was strictly concerned with the biology, rather than the physics, of sight.

The physics of vision

Another source with which Ōtsuki would have been familiar, Shizuki Tadao's Rekishō Shinsho (‘New Book on Calendrical Phenomena’), also exhibited such an exhaustively probing attitude towards translation as a process of sifting for accurate knowledge. As well as being a likely influence on Ōtsuki's ophthalmological work, the source holds special interest in two additional ways. First, it allows one to further locate the human body, and, by extension, the magic lantern, within the expanding cosmology of the Rangaku movement. Second, Shizuki's use of geometrical models was not only pioneering, but also paralleled, in an epistemological sense, the use of the magic lantern as a mechanical model to make theoretical observations.

Published in 1798, Rekishō Shinsho was a broad investigation into Newtonian physics, comprising nominally an edited translation of a Dutch anthology of the works of Oxford astronomy professor John Keill, but also making numerous references to other sources such as those of John Napier and Isaac Newton, as well as original scholarship by Shizuki.Footnote 99 Alongside the sections of the book on gravity and astronomy, there was also a considerable amount of historically important but historiographically overlooked material on geometrical optics, including in relation to the human eye. This section was focused neither on the details of human biology nor specific disorders of sight, but rather on sight as a physical phenomenon connected to the nature and behaviour of matter.Footnote 100

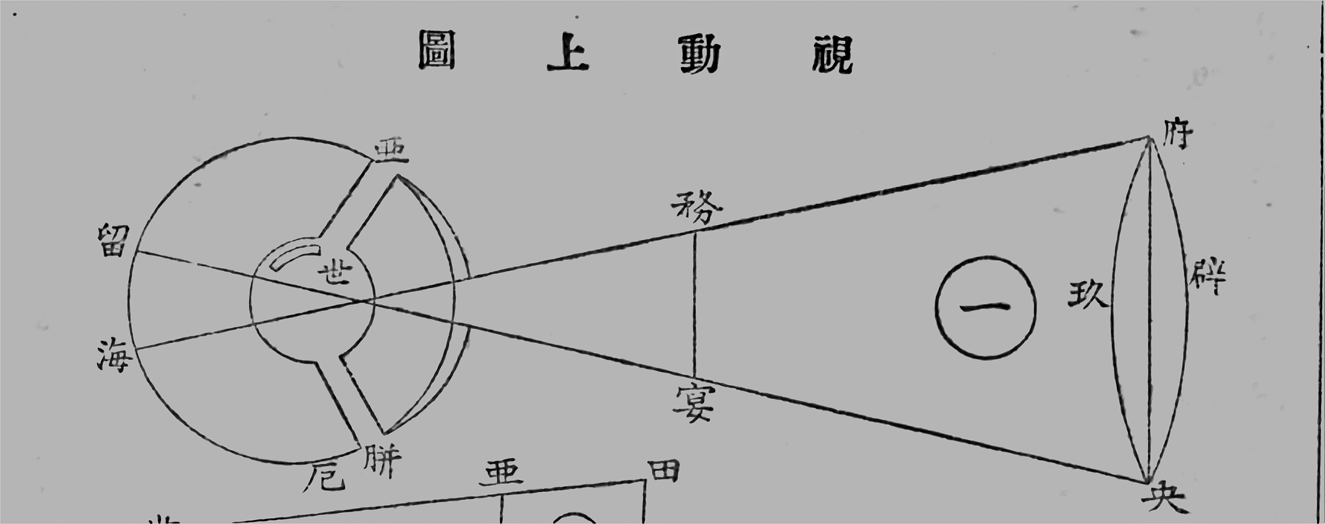

The eye in Rekishō Shinsho was a vague entity and Shizuki's illustrations of it, which were closely based on Keill's figures, were correspondingly impressionistic (Figure 9).Footnote 101 It was shown as a three-dimensional sphere with a crescent-shaped segment at the front and a spherical area in the middle that Shizuki referred to as ‘the heart of the eye’(ganshin), marked as 世 on the diagram.Footnote 102 He also identified the retina (ramonmaku) located within the fundus (gantei) at the back of the eye.Footnote 103 Shizuki explained that vision is affected by the strength of the light, the size of the object being observed, and the distance of the object, because these factors affect how much light can enter the eye. Unless light rays can pass through ‘the heart of the eye’ onto the retina, he wrote, the eye cannot form a picture.Footnote 104 Hence, the ‘field of vision’, which he marked as stretching from 亜 to 胼 on the diagram, is restricted at any given moment to objects whose light can directly reach the eye.Footnote 105 With this explanation, Shizuki introduced an explanation for the principles governing human vision, including the inversion of the image on the retina, which was based on a geometrical understanding of the behaviour of light.Footnote 106

Figure 9. Shizuki Tadao, Rekishō Shinsho, 1798, vol. 1. Source: National Diet Library.

Shizuki did not at any point, however, refer to the role of the lens in the eye in focusing light from the object onto the retina. Although ‘the heart of the eye’ is most likely meant to signify the lens, and Shizuki did allude to its vital importance within the eyeball, he did not elucidate its exact purpose and describes light as travelling in a straight line from the object being viewed to the retina of the viewer. Given that the book was written at a time when the importance of the lens in the eye was not widely acknowledged, this absence is striking only because Rekishō shinsho was the first Japanese text to describe the Newtonian concept of light as a material substance that bends in measurable geometrical ways as it travels from one medium to another. Shizuki argued that light is composed of the same miniscule particles, which he referred to as bunshi, that accumulate to form matter. Matter, he added, accumulates in turn to form visible objects of different substances, and light interacts with these substances in different, often observable, ways.Footnote 107 Out of this idea of the fundamental unity of light with matter, Shizuki also articulated a number of distinct insights on its source and nature. Light is created, he claimed, when bunshi are imbued with ki (‘energy’) through contact with fire. The bunshi-ki (‘particle-energies’) that constitute light are intrinsically in motion from place to place, but they remain a physical substance. Therefore, wherever there is light, Shizuki argued, there cannot be a vacuum (shinkū).Footnote 108 This interpretation not only tied the normally intangible force of ki to a new front in experimental physics, but also linked wider philosophical notions associated with ki across various schools of East Asian cosmology—such as the concept that, in Shizuki's words, ‘transformation is endless and all things are one’—to new scientific theories.Footnote 109

Perhaps even more significant was the way that Shizuki approached the question of observation in relation to the eyes. Newton had viewed the precise mechanism of the eye as evidence that, in his words, ‘there is a being who made all things and has all things in his power and is therefore to be feared’.Footnote 110 Omitting all deistic references from his work, Shizuki chose instead to emphasize and elaborate Keill's statement that ‘to have a true and just notion of the World, one must suppose it to be observed in different Situations and Distances’.Footnote 111 First-hand observation from the perspective of one's own eyes, Shizuki suggested, was not enough. If knowledge is to be universal, it must be based upon observation considered from different physical perspectives. It is necessary, he wrote, ‘to remove oneself entirely and become other things’.Footnote 112

In order to achieve this, Shizuki continued, one must conceive of the material world as viewed not only from other points on Earth's surface, but from other points in the universe. Using mathematical models based on the geometrical behaviour of light, he stated, it was possible for astronomers to project the eye to different locations and calculate how the universe would appear when observed from that perspective.Footnote 113 ‘When an observer views the heavens from the perspective of the heart of the sun,’ he wrote, ‘it is as if the heart of the sun is the heart of the eye.’Footnote 114 Following this line of reasoning, Shizuki introduced heliocentric theory as being essentially a matter of relative perspective. While some historians have criticized this approach for failing to highlight the incommensurability of heliocentrism and geocentrism, Shizuki purposefully kept his work open to the future discovery of other, possibly greater frames of reference from which to observe the universe.Footnote 115 This meant that, unlike the majority of his European contemporaries, he was not wedded to the ultimately incorrect theory that the Sun was the centre of the cosmos.

Combining perspectives

Ryūkei's and Shizuki's texts are the two most notable works in their respective fields from this period, offering two disparate ways of viewing human sight. Ryūkei focused exclusively on the interior structure and movements of the eyeball itself, while Shizuki was concerned predominantly with the properties of light and matter. The former dissected the body while the latter anatomized light. Although Ganka shinsho was published considerably after Shizuki's Rekisho shinsho, neither that text nor the many ophthalmology books of the 1810s and 1820s that it directly inspired, such as Higuchi Shisei's 1823 book Ganka senyō (‘The Essentials of Ophthalmology’), pay any attention to the nature of light as a serious ophthalmological concern. The two spheres remained provincialized.

Ōtsuki was able to connect these two distinct perspectives in Chōtei kaitai shinsho chiefly because he could conceptualize the magic lantern as an accurate model of the eye. The mechanical structure of the magic lantern, and the precisely coordinated motions of its interior parts, formed the clear basis of its ability to operate. Yet, Ōtsuki noted in Ransetsu benwaku, any explanation of how the magic lantern achieved its effects that does not also take into consideration the principles of light cannot do so without falling back on supernatural notions.Footnote 116 As he applied this logic to the magic lantern, Ōtsuki also applied it the eye. The internal and interconnected physiological system of the eye, he argued, is similarly reliant upon a physical interaction with light.Footnote 117 Without the interplay of both of these physical elements—one visible only through dissection and the other invisible—humans could not experience the sensation of vision. In this way, the magic lantern was an essential bond linking the increasingly prominent field of ophthalmology to the optics of light.

The wider significance of this role was two-fold. First, it helped to produce new, practical medical knowledge and expand existing anatomical perspectives. Chōtei kaitai shinsho allowed Japanese physicians and ophthalmologists to finally comprehend both the physiology and the optical system of the human eye together. This understanding rested upon a further augmentation of the idea that the human body was essentially a utilitarian machine, a conceptual framework that had been developing since Sugita's Kaitai shinsho. Whatever the possible limitations of this mechanistic conception of the body and its relationship to technical devices, it is highly unlikely that the theoretical and practical advancements that Rangaku scholars produced in Japanese medicine and ophthalmology would have been possible without it.

Moreover, its influence in Tokugawa thought was both profound and lasting. In Kawamoto Kōmin's Kikai kanran kōgi (‘Expanded Observations on Waves in the Atmosphere’), completed in 1850, Kawamoto wrote:

The workings of the human body depend on the influence of things outside the body. In order for one to deal with this kibata (lit. ‘living machine’), it is essential that one explain these external things …. Physicians should start by mastering everything to do with physics, then become well-acquainted with physiology, and after that enter pathology.Footnote 118

Physics, he stated, ‘is the foundation, and medical treatment is the final stage’.Footnote 119 Although Kawamoto was himself a doctor and physician, he insisted that medicine should be studied as a subcategory of physics, since universal natural principles acted upon human anatomy exactly as they would on any object external to it. In support of this viewpoint, Kawamoto used the equivalence of the internal eye with the external magic lantern, which he referred to as matō (lit. ‘devil lantern’) (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Kawamoto Kōmin, Kikai kanran kōgi, 1851–58, vol. 15, p. 18. Upper illustration: ‘Light travelling through the magic lantern’. Middle illustration: ‘Physiology of the eye’. Bottom illustration: ‘Light travelling through the eye’. Source: Waseda University.

Second, the usage of the magic lantern in this way was significant from an epistemological perspective. Rangaku scholars had originally sought to comprehend the eye partly in order to corroborate the validity of direct observation as a method for acquiring accurate knowledge of nature. At the same time as an understanding of the mechanism of the human sight was beginning to come within grasp, however, figures such as Shizuki recognized that the single viewpoint on nature offered by the eye also had epistemological limits. For Shizuki, this led to the use of geometrical models to project the eye and conceptualize the universe as viewed from a perspective beyond that of the surface of Earth. The task of the observer, he wrote, is ‘to remove oneself entirely’.Footnote 120 For Ōtsuki, in a similar way, this recognition led to the use of technical models to comprehend those facets of vision that could not be perceived directly by the naked eye. The eye had to become something else in order to be fully observed. The magic lantern, in becoming an ‘extended’ eye, thus also became a site wherein actual observation could be complemented with knowledge obtained through indirect observation and deduction.

In theoretical terms, this meant a softening of the strict empiricist spirit of the earliest Rangaku figures. For Sugita, for example, direct and first-hand experience, embodied in the concept of jikken, was the only sound basis for knowledge about nature. While such fundamental procedures of empiricism undoubtedly continued to be deeply important to the Rangaku movement, however, these concerns were ultimately driven by a practical need for accurate knowledge of nature that could be reliably acted upon, whether through medicine, astronomy, or other fields. Real-world results, in this sense, carried greater weight than methodology. This meant that adaptability was central and Ōtsuki's synthesis of, on the one hand, his personal observations of the eye as a physician and, on the other, his conceptualization of the ‘extended’ eye as simulated by technology held epistemological validity because it yielded knowledge that was useful to ophthalmologists, dispensing opticians, and physicians. Chōtei kaitai shinsho finally allowed Japanese physicians and ophthalmologists to understand conditions such as myopia, hyperopia, and presbyopia as refractive errors.Footnote 121

As well as revealing new dimensions to the history of the magic lantern, ophthalmology, and geometrical optics in Japan, the sources examined here should also prompt a reappraisal of the historical image of the Rangaku movement. Vital to this reappraisal is an understanding that, rather than being formed around either the pursuit of novelty or a nascently West-centric concept of civilizational hierarchy, the movement had at its heart a much broader investigative drive to acquire knowledge of nature that was accurate, universal, and suitable to its scholars’ practical needs. The examined works by Sugita Genpaku, Sugita Ryūkei, and Shizuki Tadao were, as a result, not merely direct translations from European originals, but rather the products of an exhaustive process of critical analysis, experimentation, and reconstitution. All three scholars relied on multiple texts alongside methodical observation of the natural phenomena in question. These works, when opened up to the methodological tools of intellectual history, reveal themselves as rich sources for examining knowledge creation in Tokugawa Japan, rather than simply as sources with which to trace the adaptation of knowledge in the process of its transmission from the West.Footnote 122

In a similar manner, the magic lantern as a technology in Japan was not merely a translated or transferred version of the technology as it existed in Europe, but rather one whose meaning had been reconstituted to fit a new set of practical and epistemological requirements. In Tokugawa Japan, beneath the misemono spectacle, the much-vaunted novelty appeal, and the thematic and performative connections it held with other forms of entertainment, a far more significant type of value was ascribed to the magic lantern. This saw the magic lantern conceptualized as a mechanical representation of the human eye and become a prop for efforts within the Rangaku movement to visualize, demonstrate, and investigate how the eye forms an impression of the world around it.

In this way, the magic lantern was used in the process of creating knowledge that, despite often falling under the Rangaku title, falls into neither category of ‘Western’ nor ‘native’. Indeed, in cases such as these, where transnational contact interplayed with the construction and evaluation of knowledge so profoundly, a clear distinction between such categories is not possible. The early history of the magic lantern, therefore, presents an unmistakable example of the need to re-situate the study of Japanese history in a new arena away from such dichotomies, and hints at what such an arena might look like when it comes to questions of both technology and scientific understanding.