Introduction

The effect of socioeconomic factors on body height has been the subject of many research studies. This relationship is clear when data from the 18th and the 19th century are analysed (Baten & Murray, Reference Baten and Murray2000; Alter, et al. Reference Alter, Neven and Oris2004; Jacobs & Tassenaar, Reference Jacobs and Tassenaar2004). The use of skeletal remains has shown a correlation between stature and welfare for many historical periods (Steckel & Rose, Reference Steckel and Rose2002; Steckel, Reference Steckel2005). Studies from the second half of the 20th century reported socioeconomic differences in body height on all continents in highly developed, as well as developing, countries, and even in supposedly classless socialist countries (Komlos & Kriwy, Reference Komlos and Kriwy2002; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Kuh, Peasey, Pajak, Malyutina and Kubinova2008; Viswanathan & Sharma, Reference Viswanathan and Sharma2009; Krzyżanowska & Umławska, Reference Krzyżanowska and Umławska2010; Singh-Manoux et al., Reference Singh-Manoux, Gourmelen, Ferrie, Silventoinen, Gueguen and Stringhini2010; Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Özaltin and Finlay2011). However, such differences are much smaller in countries with low socioeconomic inequality and well-developed social welfare systems than in countries with considerable inequality (Rona et al., Reference Rona, Mahabir, Rocke, Chinn and Gulliford2003; Bielicki et al., Reference Bielicki, Szklarska, Kozieł and Ulijaszek2005).

It is commonly assumed that economic factors have an indirect impact on body height and other anthropometric traits, and that these are indicators of living conditions and lifestyle. A high correlation between anthropometric traits and parents' earnings, education, family size, extent of urbanization of town of residence, dietary habits and physical exercise has been reported (Bielicki, Reference Bielicki, Ulijaszek, Johnston and Preece1998). Unhealthy living conditions and malnutrition increase the risk of diseases, and frequent or untreated infections delay biological development (Bogin, Reference Bogin1999).

Adult height is achieved over a long period and reflects living condition in childhood and adolescence. Differences in body height depending on socioeconomic status are visible not only among adults, but also at a younger age (Eiben & Mascie-Taylor, Reference Eiben and Mascie-Taylor2002; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bogin, Varela-Silva and Loucky2003; Redziĉ & Hadzihaliloviĉ, Reference Redziĉ and Hadzihaliloviĉ2007; Finch & Beck, Reference Finch and Beck2011). Despite there being numerous papers on factors affecting biological development, few of them are based on longitudinal studies (Youlton &Valenzuela, Reference Youlton and Valenzuela1990; Fedorov & Sahn, Reference Fedorov and Sahn2005; Freitas et al., Reference Freitas, Maia, Beunen, Claessens, Thomis, Marques, Crespo and Lefevre2007). The stages of growth that are crucial in determining socioeconomic disparities in biological development are yet to be fully explained.

The human pattern of growth and development is unique, and different from the animal pattern. There are two intensive growth periods: the first three years of life and the growth spurt during adolescence. Growth rate is much slower in other periods (Bogin, Reference Bogin1999). Patterns of height growth from infancy to early adulthood are controlled by a number of genetic and environmental factors. The genetic association study on longitudinal height growth in a large prospective cohort study from birth to adulthood shows that among the 48 genetic variants associated with adult height seven had a measurable effect on growth during infancy and five on growth during puberty. However, only one of these was associated with both (Sovio et al., Reference Sovio, Bennett, Millwood, Molitor and O'Reilly2009). Nutritional factors are known to have a considerable effect in infancy, whereas sex steroids and other hormones strongly regulate height growth in adolescence (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Jalil and Karlberg1998; Veldhuis et al., Reference Veldhuis, Roemmich, Richmond, Rogol and Lovejoy2005). However, the time and magnitude of the adolescent growth spurt also varies considerably among individuals. Well nourished children from families with good socioeconomic conditions experience the growth spurt earlier than malnourished children from families with poor living conditions (Steckel, Reference Steckel1986; Bogin, Reference Bogin1999). Earlier studies have shown that human stature is probably determined by two growth spurts, one in infancy and one in adolescence (Tanner, Reference Tanner1981). More recent publications suggest that a child's first years are the most significant for the development of body height (Cole, Reference Cole2003; Silventoinen, Reference Silventoinen2003; Steckel, Reference Steckel2009; Tucker-Seeley & Subramanian, Reference Tucker-Seeley and Subramanian2011).

The aim of the present work was to establish whether socioeconomic status has an impact on the increase in body height between 7 and 18 years of age, and whether the extent of differences in body height between socioeconomic groups changes during development.

Methods

Data for the study were collected in a cross-sectional survey among 1008 female secondary school students in two cities of southern Poland, Cracow and Nowy Sącz. The subjects were born in 1982–1984 and were 16 (n=463), 17 (n=345) and 18 (n=200) years old when the survey was carried out.

Body height was measured for each of the subjects. Body height data for previous years were collected from the schools' medical records. Measurements of body height and weight were made as part of a medical examination. Each student was examined in the 1st, 3rd and the final grade of primary school. The subject's age at subsequent measurements was contained in one of three age categories: 7 (6.5–7.49), 9 (8.5–9.49) and 14 (13.5–14.49) years. The measuring procedure was identical in all schools, with surgeries equipped with the same measuring instruments. Measurements at 16–18 years were also made according to the same procedure.

A questionnaire was used to collect information on subjects' socioeconomic status. ‘Place of residence’ was categorized as: (1) village, (2) city with up to 100,000 inhabitants, and (3) city with more than 100,000 inhabitants. ‘Parents’ education' was categorized as: (1) primary or vocational, (2) secondary, and (3) higher. ‘Number of children in the family' was categorized as: (1) one, (2) two, (3) three, and (4) four and more. Based on all of the above data, a socioeconomic status evaluation index was established and subjects were qualified as belonging to families of low, average or high socioeconomic status (SES). The division was introduced on the basis of the value of the first component obtained in the principal components analysis (PCA). The loadings of analysed variables on the SES index were as follow: 0.43 – place of living; 0.59 – mother's education; 0.58 – father's education; and −0.36 – number of children in family. The eigenvalue of the factor reached 2.78 and explained 62.1% of common variation in SES.

The survey method was also used to collect information on age at menarche. Age at menarche was established by a retrospective method. Girls were asked to provide the date of their first menstruation with an accuracy of one month or quarter. Age at menarche was calculated from date of menarche and date of birth. In cases when, instead of an exact date, participants reported only month and year of menarche, the 15th day of an indicated month was used for calculation, and when the date of menarche was reported approximately in the range of 2–3 months, the midpoint of the reported period was used for calculation. If the age at menarche was lower than the mean −1 SD, subjects were categorized as having an early onset of maturation; if it was contained in the interval of the mean ±1 SD, the girls were classified as having an average onset of maturation; if it was greater than the mean +1 SD, they were classified as having a late onset of maturation.

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine the normality of the preliminary quantity variables. The results showed that distributions of analysed anthropometric variables did not deviate from normal. To compare the socioeconomic group at different ages a two-way analysis of variance for repeated measure designs was applied. Differences between socioeconomic groups in height at age 14 years were tested using two-factor analysis of variance, where puberty rate was the second factor.

Results

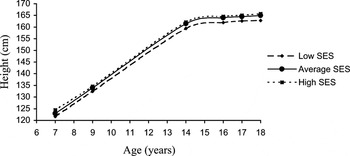

The within-subject test showed that the difference in body height with age was significant (p<0.001), and the test for the interaction of SES and age indicated that the pattern of differences in mean height by age category did not change with socioeconomic group (p>0.05, not significant) (Fig. 1). Tests of between-subject differences showed that SES had a significant influence on stature for all analysed age intervals. Girls from families of low status were the shortest, and girls from families of high status were the tallest (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Height (cm) by age cohort and socioeconomic category.

Table 1. Height (cm) by age cohort and socioeconomic category

a Significance of SES differences, based on the repeated measures analysis of variance with post-hoc comparison.

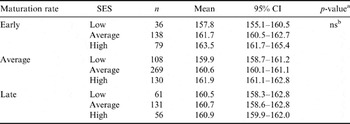

However, as is widely assumed, differences in stature during adolescence may be a consequence of varying developmental tempo, and in particular different ages of the puberty growth spurt. In the surveyed group, the mean age at menarche among low SES girls was 13.48; that among average SES girls was 13.23; and that among high SES girls was 13.04. The differences were statistically significant (p<0.001). For this reason, in the separated 14-year-old group two-way analysis of variance was conducted with SES and maturation rate as factors. After dividing the material into uniform groups in terms of maturation rate, pronounced socioeconomic gradients in body height were found (Table 2). The test of the maturation rate and SES interaction showed a non-significant result (Table 2). Therefore, differences in stature at 14 years of age according to socioeconomic status did not result from a different maturation rate.

Table 2. Height (cm) at 14 years of age by maturity and socioeconomic category

a Significance of interaction between ‘maturation rate’ and ‘socioeconomic status’, based on MANOVA.

b ns, non-significant.

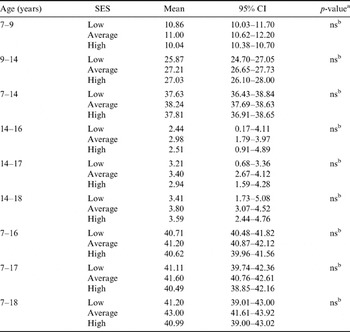

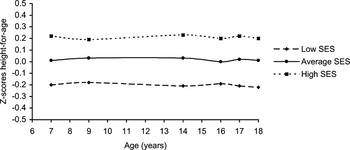

Socioeconomic status did not have any impact on the increase in body height between the ages of 7 and 9 years, 9 and 14 years, 14 and 16, 17, 18 years, 7 and 14 years and 7 and 16, 17, 18 years (Table 3). The differences in mean body height between high and low SES groups did not vary significantly with age and were 2.8 cm at the age of 7 years, 2.1 cm at 9 years, 2.6 cm at 14 years, 2.7 cm at 16 years, 2.4 cm at 17 years and 2.9 cm at 18 years. Figure 2 presents standardized height-for-age Z-scores by age cohort and socioeconomic category.

Table 3. Height gain (cm) by age cohorts and socioeconomic category

a Significance of SES differences based on ANOVA.

b ns, non-significant.

Fig. 2. Standardized height-for-age Z-scores by age cohort and socioeconomic category.

Discussion

No marked differences in growth rate among individuals are observed in the prenatal period, which is reflected in a low variation in birth weight and length (Cole, Reference Cole2003). After birth, a period of rapid growth begins due to the secretion of growth hormone. A high growth rate is observed during the first year of life, followed by a period of slower growth, with another peak in adolescence (Bogin, Reference Bogin1999).

The growth process and body height in adulthood are influenced both by genetic and environmental factors (Silventoinen, Reference Silventoinen2003; McEvoy & Visscher, Reference McEvoy and Visscher2009). Malnutrition in early childhood is known to be a considerable factor in the regulation of height and growth. The effects of malnutrition may be partly compensated by the prolonged human growth period (Steckel, Reference Steckel1986). Some populations suffering from malnutrition attain their adult stature as late as at 25 years of age (Bogin, Reference Bogin1999). Many studies have shown that children from families of low socioeconomic status begin puberty at a late age, and reach each stage of development at an older age than children from families of high socioeconomic status (Obeidallah et al., Reference Obeidallah, Brennan, Brooks-Gunn, Kindlon and Earls2000; Olszewska & Łaska-Mierzejewska, Reference Olszewska and Łaska-Mierzejewska2008; James-Todd et al., Reference James-Todd, Tehranifar, Rich-Edwards, Titievsky and Terry2010). A significant difference in the mean age at menarche between socioeconomic groups was noted in the surveyed group. Girls from families of low socioeconomic status had their first menstruation at an older age than their peers from families of high status. Still, despite the significant differences in age at menarche between socioeconomic groups, the increases in body height between the ages of 7 and 14 years, and 7 and 16, 17, 18 years, were similar in children from families of lower SES and families of high SES. Lack of annual measurements makes it impossible to precisely determine the age and intensity of the adolescent growth spurt. It is thus difficult to establish the correlation between the timing and intensity of the adolescent growth spurt and adult body height of the surveyed girls. According to data cited in research studies, there is a negative correlation between the timing and rate of the adolescent growth spurt, which among European and Euro-American females ranges from −0.21 to 0.60 (Largo et al., Reference Largo, Gasser, Prader, Stuetzle and Huber1978; Hauspie, Reference Hauspie, Johnston, Roche and Susanne1980; Wember et al., Reference Wember, Goddemeir and Manz1992). On the other hand, a weak and statistically insignificant correlation between peak height velocity and age at peak height velocity has been reported among non-Western populations (Floyd, Reference Floyd1998). This may be due to different living conditions (Bogin et al., Reference Bogin, Wall and Mac Vean1990; Floyd, Reference Floyd2000). Socioeconomic factors may influence the relationship between age and the intensity of the growth spurt. Research carried out among Tapei girls has demonstrated that young female subjects from well-educated families with a good financial situation display a statistically significant negative correlation similar to European or American girls from well-off families, whereas a statistically significant positive correlation was observed among girls from poor families and girls whose living conditions had considerably improved when they were in primary school. However, the differences in stature increments in childhood and adolescence between those groups were very slight and statistically insignificant (Floyd, Reference Floyd2000). Other researchers have indicated that the time and intensity of the growth spurt is not significantly correlated with the stature of an adult individual (Tanner et al., Reference Tanner, Whitehouse, Marubini and Resele1976; Largo et al., Reference Largo, Gasser, Prader, Stuetzle and Huber1978; Sheehy et al., Reference Sheehy, Gasser, Molinari and Largo2000; Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, Sheehy, Molinari and Largo2001).

In the present study SES-related inequalities in height were found to remain unchanged over juvenile and adolescent stages and were 2.8 cm at age 7 years and 2.8 cm at 18 years. The results suggest that differences in body height depending on socioeconomic conditions are established in early childhood and persist to early adulthood. The scale of such differences does not vary in adolescence.