Introduction

Across the world, there is a wide range of views on the use of assisted dying as an option for those who are terminally ill. Assisted dying refers to both voluntary active euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (PAS). These two types of assisted dying are distinguished by a difference in the degree of involvement of a doctor.Reference Nora, Bernat and Beresford1, Reference Holm, Fillit, Rockwood and Woodhouse2

Typically, both methods of euthanasia assistance occur for the purpose of relieving the patient from intolerable and incurable pain. This is an important motive for those who request assisted suicide.Reference Emanuel3 The presence of intolerable suffering as assessed by a physician is one of the primary criteria for PAS in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.Reference Rietjens, van Tol, Schermer and Heide4–Reference Ruijs, van der Wal, Kerkhof and Onwuteaka-Philipsen6

However, it is essential to recognise that both methods of assisted dying are to be distinguished from other end-of-life practices and their current ethical-legal status. End-of-life practices are a highly debated topic in many countries. The international evidence is regularly used to either back or oppose attempts at legal reforms.Reference Downar, Boisvert and Smith7, Reference Suarez-Almazor, Belzile and Bruera8 Canada, the United Kingdom (UK) and France have all referred to research carried out in other countries to support the debate, together with cases brought to the Law courts.Reference Delamothe, Snow and Godlee9

One example of an end-of-life practice is the withdrawal of treatment, at the request of a competent patient or their leading clinician. Usually, this requires a process of appealing to the Law courts.Reference Turner-Stokes10 The withdrawal of treatment is the only action towards assisted dying, which is currently legal in the UK. It comes under the definition of ‘Passive euthanasia’, and was ruled to be legal after the case of Anthony Bland, in 1993, was brought before the Law courts.Reference Szawarski and Kakar11

Currently, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, assisting a suicide is a crime. In the UK, euthanasia has no legal position, and acts of euthanasia have previously been treated as murder. However, it is the Suicide Act 1961,12 which makes it a specific offence of ‘criminal liability’, when a person is complicit in another person’s suicide.Reference Parry-Jones13 Those convicted can potentially face up to 14 years in prison. There is no specific crime of assisting someone to commit suicide in Scotland because the Law there has been left in an uneasy state of prevarication regarding their attitude to assisted suicide.Reference Chalmers14 However, it is still possible there for an individual engaging in complicity with another person’s suicide to be the subject to prosecution for culpable homicide.

The Law throughout the UK prevents dying people from asking for medical help to assist them to die. However, there have been several recent attempts to change this. In England, the legislation proposed by Lord Joffe: Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill (2005–06)15 was rejected by the House of Lords, along with the rejection of the Bill proposed by Lord Falconer several years later, Assisted Dying Bill (2013–14).16 In Wales, there were four separate attempts to introduce an assisted dying Bill between 2003 and 2006, and all were rejected by politicians.

There is an ongoing worldwide debate both for, and against, making assisted dying legal and acceptable. At present euthanasia is legal in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland. Assisted suicide is also legal in Canada, Japan and the US states of Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Vermont, Montana, Washington DC and California. Several European countries, such as Spain, Sweden, England, Italy, Hungary and Norway, all allow passive euthanasia under strict circumstances. Passive euthanasia is when a patient suffers from an incurable disease and decides not to accept life-prolonging treatments, such as artificial nutrition or hydration.

Only a few countries approve of assisted dying as a whole, with assisted suicide being provided for by Laws in the Netherlands, Switzerland and the US State of Oregon. In Belgium and the Netherlands, there is legislation for euthanasia. However, unlike in other countries, in Germany, assisted suicide can be practised by anyone who is not a physician, because there is no existing Law that forbids this.

When working with a patient making end-of-life decisions, beyond the ethical concerns present with any client, the position is that the ambiguously defined and potentially dynamic role of the psychologist could give rise to complex ethical dilemmas and legal liabilities.

Purpose of the study

The growing worldwide acceptance of the use of assisted suicide and euthanasia and the complex ethical and social dimensions of this issue present an interesting context in which to explore the understanding of and the views and attitudes towards assisted death and euthanasia in a general population in the UK.

The purpose of this study was not only to explore the understanding of and the views and attitudes of a population towards assisted dying, but also to explore these in relation to an individual’s personal demographics, professional background and education and to further identify which individuals would or would not consider assisted death under certain circumstances.

The sample population in this study will include a variety of individuals from different educational and professional backgrounds. The hypothesis of the study is that individuals from a health and/or psychology-related background will, overall, be less likely to support assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted during August 2018. The sample population was a target number of 300 people obtained through a simple random sampling method of participants who were all volunteers, anonymous and from the general population in the UK.

The researcher was confident that a large enough sample could be achieved through access to individuals through the use of convenience sampling using email channels and social media, based on a platform designed for data collection using Survey Monkey. It was recognised that the study needed to sample enough participants to enhance the reliability and validity of the research.

This study included the use of human subjects in the data collection and consequently required that the design of the study met ethical principles of research,Reference Braun and Clarke17 including beneficence, non-malfeasance, integrity and impartiality, as considered by the University of Hull Research Ethics policy, and their requirement to submit the Ethics Checklist for research projects involving human participants. This study gained ethical approval from the University’s Ethics Committee.

Participants were not forced, coerced or bribed into completing the questionnaire. Participants were offered the option to cease completing the questionnaire at any point during completion. Qualitative data collected from all participants was anonymised.

The questionnaire was anonymous, and informed consent was sought by the completion of a text box, but it was also assumed through the completion and return of the questionnaires.

Consent was gained from each participant through a separate page on the online survey software prior to the start of the questionnaire. Participants were informed at the start of the survey that all responses would only be used for the present study. All of the data was anonymised and complied with the Data Protection Act (2018).18

Confidentiality of the data provided was adhered to and requests for personal data were minimised, and participants could choose whether or not to contribute such information.

Procedure

The data collection was a mixed method of quantitative and qualitative design using a single survey approach through the use of an online-based questionnaire, delivered through the university’s licence to onlinesurveys.ac.uk. This method provided a balance between data, which can be analysed and presented through SPSS, as well as provided data, which can contextualise the beliefs and values of participants. Requiring the qualitative data alongside the quantitative data further defines the existing data and provides a more in-depth understanding, thus improving the reliability of the data collection and analysis as well as ensuring robust research outcomes.

The questionnaire comprised of single multiple choice, tick box questions and open-ended questions, with space provided to add explanations and additional information. The first part of the questionnaire was concerned with the demographics and background of the participant and yielded dichotomous nominal data.

Before the primary research was conducted, a pilot study was carried out to verify a clear understanding of instructions, timing and the validity of the responses to the questionnaire. Responses were recorded, and participants were asked to provide feedback on their experiences in completing the questionnaire.

Feedback provided on the pilot questionnaire allowed for an informed view on improvements which were made prior to carrying out the main body of research, including the addition of an extra question, improving the clarity of the questions and allowing for an estimation of how long the questionnaire would take to complete.

Measures

The participants were first asked about their demographics and educational background. Then, they completed a more qualitative section regarding their opinions towards assisted dying. Finally, the third section covered scenarios and asked them to provide their response to quantitative multiple-choice questions, and through qualitative questions to explain their reasoning.

Data analysis

The answers supplied provided a wide range of data, which were then split into their separate categories of qualitative and quantitative data. The quantitative data was analysed and evaluated with the use of IBM SPSS, version 24. Qualitative data was then analysed with the use of a multivariate analysis of variance.

The qualitative data was coded to formulate themes and collective responses to form concrete indicators for those themes. This analysis was primarily performed manually with final themes and concepts being typed up later. Different views were evaluated through a combination of SPSS, for quantitative data, and content analysis, for the qualitative data.

Results

In response to the online-based questionnaire, from a target population of 300, 117 responses were received. One response was excluded from the data collection because it did not meet the inclusion criteria, due to the responder not completing the consent section.

From section 1 of the questionnaire, related to the survey demographics, there were responses from 36 male and 80 female responders. Their ages ranged from 19 to 88 years (median = 41·66 years, standard deviation = 17·58 years). The majority of participants indicated they were from the UK, 85·34%, and 12·07% indicating they were of various other nationalities and 2·59% choosing not to indicate their nationality.

The sample demonstrated a wide range of professional and educational backgrounds. Many respondents had completed a higher education degree of some description (undergraduate degree = 25%, postgraduate degree = 27·6%, PhD = 27·6% and 17·2% declined to answer).

From section 2 of the questionnaire, the overall majority of respondents were in support of assisted dying, with 85·5%, believing that assisted dying should be legal in the UK (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bar chart shows the results of Question 9. ‘In 2018, assisted dying is not legal in the UK. Do you think it should be made legal?’

Furthermore, the majority of respondents also believed that individuals should be allowed to decide when, 88%, and where, 88·9%, they die (see Figures 2 and 3, respectively).

Figure 2. Responses for question 15.

Figure 3. Responses for question 17.

The responses and demographic data was further analysed into three groupings; these were educational background, gender and highest educational achievement.

SPSS analysis of variance

There wasn’t a statistically significant difference in responses based on educational background. F (15,299) = 1·10, p = 0·35, Wilk’s Ʌ = 0·862 and partial η 2 = 0·05. The detailed results are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Statistics for analysis of responses against participants’ educational background

a Design: Intercept + Q5.

b Exact statistic.

c The statistic is an upper bound on F that yields a lower bound on the significance level.

d Computed using alpha = 0·05.

There wasn’t a statistically significant difference between responses based on gender. However, it is important to note that there were unequal sample sizes involved in this analysis. Therefore, F (3,112) = 1·34, p = 0·26, Wilk’s Ʌ = 0·965 and partial η 2 = 0·04. The detailed results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Statistics for analysis of responses against participants’ gender

a Design: Intercept + Q2.

b Exact statistic.

c Computed using alpha = 0·05.

The third grouping analysed was the participant’s responses against their highest educational degree/qualification. Once again, the statistics given were not statistically significant. F (9,219) = 1·34, p = 0·22, Wilk’s Ʌ = 0·878, and partial η 2 = 0·04. The detailed results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Statistics for analysis of responses against the highest degree of education

a Design: Intercept + Q6.

b Exact statistic.

c The statistic is an upper bound on F that yields a lower bound on the significance level.

d Computed using alpha = 0·05.

Due to only a minority of respondents being against the concept of assisted dying, there wasn’t a statistically significant difference found in any of the possible grouping variants.

Other questions looked more closely at the individual’s thoughts on assisted death. 47% would consider physician-assisted death (PAD) within the UK if it was legal, 31·6% might consider it, 12% would not consider it as a possibility (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Responses for question 16.

Exploring this theme further, participants were asked whether they would travel to a country where PAD is legal, considering PAD is not legal in the UK. Responses indicated that 21·4% of respondents would definitely travel to another country for PAD if necessary, while a further 45·3% would under certain circumstances. 11·1% of respondents would not consider the option, and 22·2% were uncertain how they would respond (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Responses for question 11.

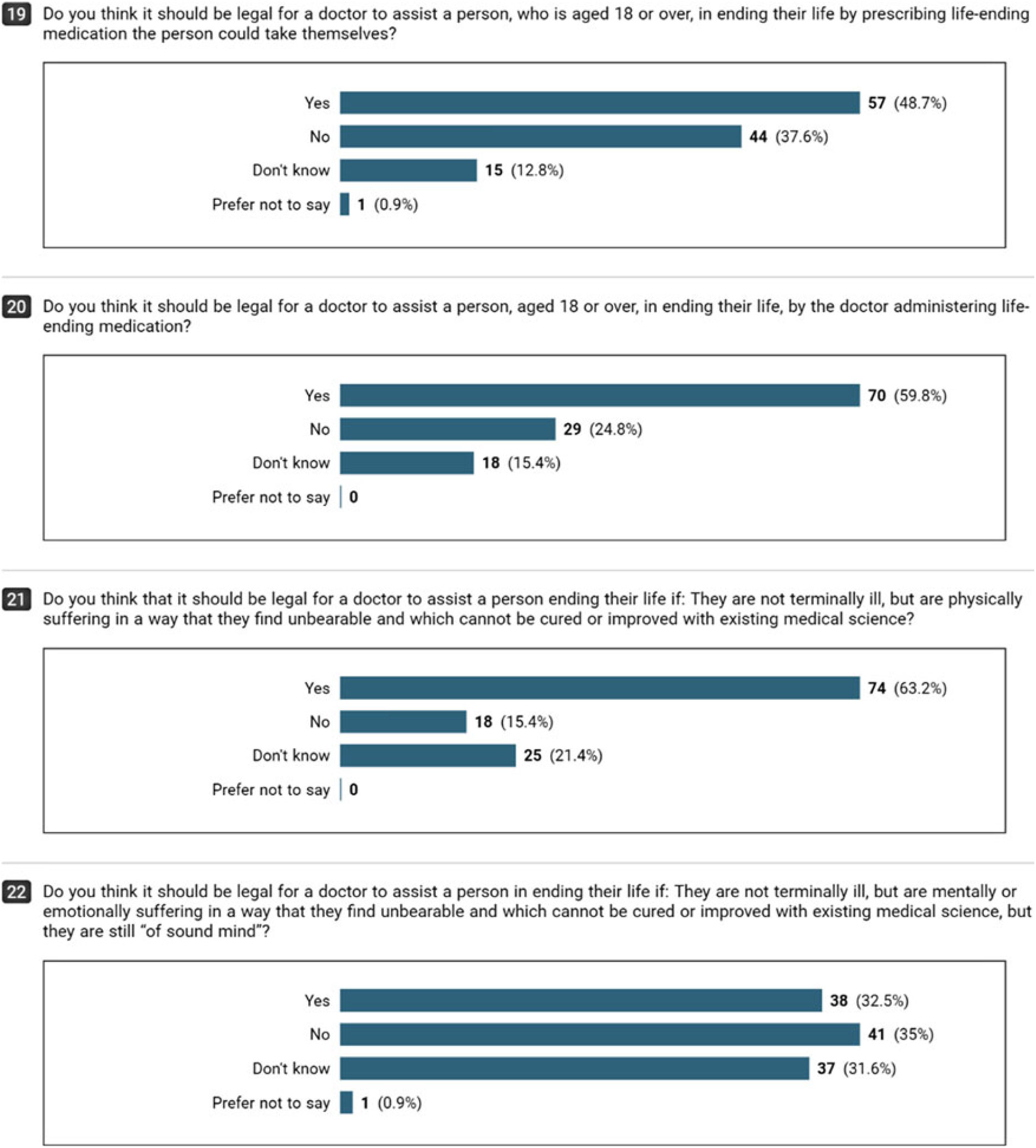

Finally, the participants were questioned on the circumstances that may lead to an individual making the decision for PAD. The majority of responders were in support of a doctor supporting PAD; however, more responders were in agreement with a doctor administering the lethal medication than the individuals taking it themselves, 59·8 and 48·7%, respectively.

These results showed that responders believed more strongly that PAD should be available to those whose physical suffering is unbearable, rather than those who have emotional or mental health suffering, 63·2 and 32·5%, respectively (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Responses for questions 19, 20, 21 and 22.

It is noted for each of these four questions that between 15·4 and 31·6% of responders indicated that they don’t know if a doctor should assist in an individual’s suicide in any of these circumstances.

Qualitative: findings

Section 3 of the questionnaire was concerned with responders’ understanding and personal views of assisted dying. There was a 100% response rate on all eight qualitative questions. However, with regards to answering the question, the response was 98·3%, with two respondents choosing not to respond to the questions and answering the questions regarding their understanding of the concept with:

‘I do not agree’.

The findings showed that the majority of respondents to have a good understanding of the term ‘Assisted-dying’ and its implications on easing end-of-life practices for those who suffer unbearably, either in a care setting or at home, and the fear of legal consequences and lack of approved options:

‘Everyone has the right to decide if they wish to live or die. No one has the right to judge others by making this important and drastic decision. People’s individual rights and wishes should be respected, even if we do not agree or like the outcome’.

‘Palliative care is not excellent throughout the UK, and people still die undignified and painful deaths. Fear of litigation can still prevent people from having proper pain relief in home settings’.

While coding the results, two main themes emerged in support of assisted dying. Theme 1 was that it should be an individual’s personal choice whether they wish to assist their own death, and theme 2 was that it was perceived that because of the lack of treatment options for terminally ill people who are suffering unbearably, assisted suicide was acceptable.

However, there were also several arguments made for why the concept should remain illegal:

‘This is not a choice for people. It is a choice of God who created us.’

‘I think it is open to abuse by unscrupulous relatives/doctors thus making it murder’.

Comments against assisted dying tended to focus on two main themes: religious beliefs and the fact that the practice has the potential to be abused by those who would receive personal benefit.

During the coding of the data, there were several main themes that occurred throughout the responses: Religious beliefs, unscrupulous reasons, medical reasons and moral reasons.

Arguments for assisted dying

Personal reasons

Many respondents felt the practice should be legal for the reason of it being an individual’s own choice on how their life should end. There was a strong response rate of 64·3% to indicate that it should be the individual’s decision on how they should be allowed to die and that they should not be judged by others for their decision. Many respondents felt the decision should be theirs to make when the time comes and that they should not have to be influenced by others due to the potential stigma they will receive for making that decision:

‘Everyone has the right to decide if they wish to live or to die. No one has the right to judge others by making this important and drastic decision-people’s individual rights, and wishes should be respected, even if we do not agree or like the outcome’.

There was a conflict between the responses of those who felt strongly about how those who are physically able to, can and do end their own lives and that such an opportunity should be available for those who are not physically able to carry out the suicide themselves:

‘A person should be allowed to end their life if they feel the need to. People who are able to do so are allowed to do it so the same should be for those who need help doing so’.

There are others who recognise that legalising the practice will cause its own problems, which will need a high level of regulation to make it possible.

‘Needs a high level of regulation and safeguards in place but should be legalized to maintain dignity over life, choices in illness and death’.

Medical reasons

For the sub-question to question 9, ‘In 2018, Assisted-dying is not legal in the UK, do you think it should be made legal?—Please give reasons for your answer’, 22·2% of respondents indicated that they felt it should be the legal choice of the person dying of a terminal illness, whether to make their last few hours less painful and traumatic for all involved. One respondent indicated that they felt it would have been far less distressing for both patient and family, personally if their family member had not suffered as they passed:

‘Having watched 8 people die in the past 7 years, half of those a long, drawn-out death from cancer, I have learnt a lot about the process of dying. Far more than any non-healthcare-professional should know. I have watched four family members in the past decade (and one other 17 years ago) die a slow, lingering death. These relatives lived full and happy lives. They would not have lost out on anything by being given extra morphine in their final weeks, once they were bedridden and their loved ones had said goodbye. It would have been a lot less traumatic for my family who has now died, and for those who kept vigil by their bedsides, had they been entitled to assistance in death’.

One respondent, who has a pharmaceutical background, looks at the concept from a different angle which is no less important than a personal one:

‘As a pharmacist of 32 years, I have seen the pain and suffering too many individuals when pain or other upsetting symptoms could not be controlled’.

Others acknowledge how medical advances in the last few decades mean everyone is living far longer than a century ago. 5·4% of responses suggest it is due to medical intervention that people who are ill are living longer, but not recovering, and that medical intervention should therefore be allowed to ease the suffering of those who are terminally ill and won’t recover, thus easing symptoms of depression in the patient and family as they suffer through pain and treatments to prolong that suffering:

‘Given our medical advances, humans now live too long for our bodies to cope. Arthritis, Dementia/Alzheimer’s, Cancers and many other undignified and painful illnesses are at their highest incidences with people of an older age. I’m by no means saying that with arthritis you should be allowed to end your own life - but with a terminal illness (such as cancers) or an undignified one (such as dementia/Alzheimer’s) it should be possible to assist in easing said person on (if it is their individual wish) to avoid suffering’.

Arguments against assisted dying

Religious reasons

There were several respondents who were firmly against the concept of assisted dying on religious grounds. These few respondents, 0·43%, were considerably less thorough in completing their responses when asked to provide reasons for their answers on multiple-choice questions. The responses state that their reason for believing that assisted dying should not be made legal is due to religious beliefs:

‘It is against my beliefs’.

‘This is not a choice for people. It is a choice of God who created us’.

A few respondents were very clear throughout the questionnaire on their views and opinions regarding why it should not be made legal. They indicated how it was up to their religions’ higher power on who should die at what time. One respondent indicated that their opinions stemmed from their belief of how all life is precious and should be protected at all costs:

‘I have a strong Christian faith and beliefs which would stop me from ending my own life, and especially for involving someone else in this act. I believe that we must protect life at all costs. I also believe that doctors who have trained to save a life should never be put in a position where they are asked to cause the death of a patient. We do not know the psychological toll this will take on them over time. I am also aware of the many hospices throughout the UK which strive to provide a dignified death through care and, where appropriate, the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. I believe that the government must do more to promote and protect hospices and the provision of palliative care throughout the UK’.

Unscrupulous reasons for assisting

There were several respondents who stated assisted dying should not be made legal, and they would not condone it due to any system not being entirely safe. Respondents highlighted the fact that there would have to be fixed safeguarding if it became legal. One individual highlighted how the system was not suitable for the UK. Others indicated concern about whether those who assisted in the death were doing so for selfish reasons:

‘There are too many safeguarding issues and detecting whether or not someone has been coerced towards seeking to end their life is too difficult’.

‘Assisted suicide - one could be coerced. Suicide - your choice alone’.

For those respondents who mentioned different unscrupulous intentions behind assisting in death, this was a powerful topic. There was concern about whether the individual seeking help was doing so of their own free will, whether they were being unknowingly coerced or whether they were not mentally fit to make the decision. This is highlighted very well by one respondent who pointed out the risk of abuse to the system:

‘Risk of abuse and lack of robust framework to protect individuals’.

Medical reasons

The third theme identified in the data against assisted dying was due to medical reasons. One respondent highlighted that medicine is a science that not even science is foolproof and that mistakes will always occur:

‘Medicine is just a study and is never 100% correct - it may be that your life will not end as badly as predicted. Your life is not always what you want it to be, but that does not mean you should kill yourself because tomorrow may hold a blessing’.

This response indicates a lack of trust that diagnoses are not accurate 100% of the time and that assisted death should not be an option because an individual will never know what their future would have been like, and the outcome might have been better than expected.

A second respondent was also concerned and highlighted human error as the reason they are against assisted suicide. Another respondent indicated how human error happens every day, and no system can account for it all of the time. Human error will occur, and procedures will go wrong or happen to the wrong person:

‘This procedure is irreversible therefore no mistakes can be made. Human error will lead to murder’.

Moral reasons

The final theme identified while coding the data was moral reasoning. Seven respondents, 0·6%, highlighted that they did not agree with the concept of assisted dying due to firm beliefs that life is precious. However, the reasons behind this theme were more complex. One response indicated that this was due to wanting to appreciate the life they had with their loved ones for as long as possible:

‘My life is precious. My time spent with loved ones is precious - I wish to spend as long as possible with them’.

Others revealed a concern for the family left behind by those who sought assisted death in a foreign country. The response highlighted how distressing this could be for family members who are left with no other choice than to stay behind:

‘Travelling elsewhere to die can be cruel for those left behind, causing unnecessary heartache and expense. It is illegal in this country for a reason’.

A final point of view was the lack of appreciation of the life these individuals already have. This response notes that no matter how dark life becomes, a light can always be found. They comment on how assisting a suicide is not appropriate and should not be supported:

‘I fail to see the difference between the two. However, assisted dying is an inappropriate compromise to suicide and should not be condoned, there is always a light to be found in the dark’.

All of these respondents clearly indicate their own beliefs and opinions about the concept. It is a concept that is highly controversial and debated readily all over the world. However, one respondent has addressed the issues entirely in the first sentence of her response. The response summarises the thoughts behind the majority of responses, which do not support the idea of assisted dying:

‘It is a difficult question to answer because with every solution is a problem and has unforeseen consequences, but it has happened in other countries’.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate and evaluate the views and opinions of individuals towards the topic of assisted dying and euthanasia. Information was gathered through the mixed methods questionnaire and then screened for possible grouping variables for the quantitative statistics. The data analysis revealed that there was no statistical significance in various groups due to the majority of the participants being in favour of the legalisation of assisted dying and euthanasia.

There was no correlation between those who support assisted dying or those who do not and their professional background or educational status. This was not in support of the original hypothesis of this study : ‘the outcomes of the study will find that those individuals from a health and a psychology related background will overall, be less likely to support assisted suicide and euthanasia’.

The study included a review of the relevant legislation for other countries and states around the world. This review revealed the logistics and issues others faced in attempting to legalise assisted dying, such as in Australia, where it was legal for a short period of time before the decision was overturned and once again made illegal.Reference McCormack and Fléchais19 It is unlikely that the debate over the legalisation of PAD and euthanasia will ever end. At present, the majority of the legislation that exists addresses the choice of assisted dying in respect of adult patients who are terminally ill, with their deaths predicted within a specific time frame, typically 6 months.

The study found that the majority of respondents believe that assisted dying and euthanasia should be a legal option available to those who are physically suffering and that they should have the choice. The results show that the majority of participants believe that it should be legal in the UK, that everyone should have the right to make their own choices about their life and that they should be able to seek assisted dying because of unbearable suffering or because they are terminally ill with less than 6 months left to live, should they so wish. Many responders felt strongly that if patients were able to make this choice, then the experience would be far less traumatic for everyone involved and that the patient could thereby die peacefully and painlessly with their loved ones by their side.

None of the countries or states that have legalised PAD and/or euthanasia have incorporated policies requiring psychological or psychiatric reviews in all cases of requests for assisted dying, although it has been recommended several times over the years by several different studies and reviews on the topic.Reference Bosshard, Broeckaert, Clark, Materstvedt, Gordijn and Müller-Busch20–Reference Werth, Lewis and Richmond22 In all cases, it is deemed the patient should display mental capacity and competence, but there isn’t a requirement for them to be assessed by psychiatrists or psychologists to confirm this capacity and competence.

The study reveals many strong opinions on autonomy, focusing on how it should be an individual’s decision and that the decision should not be impeded by the House of Lords rejecting the legalisation of PAD within the UK. However, at the same time, the analysis shows that those who are in favour of legalisation recognise the importance of having sufficiently structured safeguards in place to overcome the foreseen problems.

This was one of the main reasons for several respondents as to why PAD and euthanasia should not be legalised. The responses expressed their concerns about the high potential for abuse, where those who would benefit from the death of the patient could potentially coerce them into agreeing to euthanasia. This clearly highlights the necessity for checks and balances to control the circumstances and keep the patient safe, at the same time as respecting their wishes.

The UK already has a proposed model for the introduction of PAD, which can be found within the Bill proposed by Lord Falconer, Assisted Dying Bill [HL] (2013–14).16

The Bill includes a level of criterion for when assisted dying could be considered, whether the patient is of legal age, is suffering from a progressive disease which is resistant to treatment and where the patient expected to die within 6 months. In these circumstances, it would typically be the decision of the medical professional to decide whether the patient is eligible to be given this choice. However, the strong negative reaction of medical professionals to the Bill saw it being rejected in the House of Lords.

Reasons for choosing PAD

A reoccurring theme for respondents to the questionnaire, and one of the most common reasons given for choosing PAD, was the loss of dignity, reported on behalf of both the patient and the family. It is for this reason that the most touted term in the context of assisted dying and euthanasia has become ‘Death with Dignity’. PAD and euthanasia are also referred to under this term in several legislative reports for the various states in the USA.23–26

The study indicates that death with dignity is the concern for physicians in other countries who do participate in PAD. Physicians in Washington state, Oregon as well as the Netherlands who are asked about the motives of their patients, have stated the motive that stands out the most is concern over the patient loss of dignity.Reference Downar, Boisvert and Smith7

Another reason for choosing PAD, which occurs far less, but it still mentioned by respondents, is the patient’s perceived burden to others. This is particularly true for palliative care where the patient has returned to their own home. It is a reason why a few respondents stated they would consider euthanasia. This response was usually associated with the participant having a family member who returned home before their death. It was noted how this added stress and anxiety to the family when the patient perceived their own care at home as a burden to others. Thus, it was reported to be a common reason for desiring euthanasia, by the patient, when they felt they became a burden for those who cared for them the most.Reference Wilson, Curran and McPherson27

Reasons for not choosing PAD

One of the reasons identified in this study for individuals not wanting to consider PAD and euthanasia is the risk of abuse and coercion of vulnerable people. It is known that abuse of the elderly already occurs across the UK, and it is believed by some respondents that if PAD was to become legal with inappropriate safeguards, then it is only a matter of time until an elderly patient is coerced through abuse or manipulation by those who would benefit from their death.Reference Suarez-Almazor, Belzile and Bruera8, Reference Turner-Stokes10

A second reason identified is because of the religious views of the participants. There was a good indication and a common reason for participants not to consider PAD and euthanasia because of the intrinsic value of every human life. It is the belief of these respondents that it is crueller to those who are left behind when someone dies. A repeated view stated by several respondents is that it is not our place to decide to take a life, but god’s place, and all human life is sacred and should therefore be protected.Reference Abeles and Barlev28

The main limitation was the small scale of the study.

The questionnaire had its limitations due to the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative questions. The quantitative data gathered was limited in its responses with there being no identifiable grouping variable for comparison when using statistics. The questionnaire was not as long as originally planned due to the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative data, as well as the amount of time needed to complete the survey.

A more thorough study, involving a larger sample size and therefore participants from a greater range of disciplines, would increase the ecological validity of the study, while also allowing for the possibility of discovering whether there are demographic groupings, which become statistically significant when the data is analysed. If the study had been longitudinal, then it could have also explored whether participant’s responses to the questions change over time, as their personal circumstances change. Both of these options would improve the reliability and validity of the study.

As part of this study, respondents were questioned on at what point or when would they consider seeking an assisted death for themselves. This could be further explored for more details. Further research could sample patients who are terminally ill or are suffering from a degenerative disease, to carry out qualitative research on their desires and wishes for end-of-life care, to make the experience less traumatic and distressing for all those involved.

Conclusion

Worldwide, there is much ongoing debate about the right of an individual to seek assisted suicide. Some modern-day societies have sought to provide legislation to legalise PAD whilst others have firmly taken the stance to make it illegal, for example, in the UK.

The majority of respondents in this study, the majority living in the UK, indicated that they believe assisted suicide should be made legal, an option available for those who are terminally ill. Views indicated that if assisted dying was legal, it would allow terminally ill patients to die with dignity and without prolonging pain. The wishes of the individual should be accepted without fear of judgement by others for their decision. This would grant the terminally ill and mentally competent adult the ability to decide on when to die and to pass away painlessly, peacefully and with their family close by when the time comes.

A minority of respondents in this study were opposed to assisted suicide, no matter what the circumstances were. This view was supported by the belief that assisted dying isn’t a right for anyone to have, and no one should take their own life, because life is precious. However, generally, respondents agreed that it is important to ensure that a terminally ill patient’s last days are as pain-free, comfortable and as dignified as possible.

Author ORCIDs

Sophie Duxbury, 0000-0003-2593-0434

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my appreciation to all those who participated in filling out the questionnaire created. Their willingness to take the time to provide their opinions and knowledge has been greatly appreciated.