Introduction

Necrotising external otitis, also known as malignant otitis externa, is an aggressive, potentially fatal infection of the external ear canal, skull base and adjacent soft tissues. The term malignant otitis externa was first used in 1968 by Chandler, in a seminal review, to reflect the condition's grim outcome; however, the terms invasive and necrotising are increasingly being used to convey the fact that necrotising external otitis is not a neoplastic condition.Reference Chandler1–Reference Nadol2

Patients usually present with symptoms of acute external otitis, such as itching, extreme otalgia and otorrhoea. However, patients occasionally present as an acute neurological emergency with signs of skull base osteomyelitis and intracranial extension.Reference Clark, Pretorius, Byren and Milford3–Reference Cavel, Fliss, Segev, Zik, Khafif and Landsberg5 Diabetics, immunocompromised patients and the elderly are particularly affected; the prevalence of diabetes in necrotising external otitis patients has been reported as between 51 and 100 per cent.Reference Chandler1, Reference Franco-Vidal, Blanchet, Bebear, Dutronc and Darrouzet6–Reference Mani, Sudhoff, Rajagopal, Moffat and Axon9

The most common pathogen in necrotising external otitis cases is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative, obligate aerobe not commonly found in the external auditory canal.Reference Grandis, Branstetter and Yu10, Reference Carfrae and Kesser11 Other pathogens have also been implicated, including Gram-positive organisms, Aspergillus flavus, Proteus mirabilis and candida species.Reference Clark, Pretorius, Byren and Milford3, Reference Ali, Meade, Anari, ElBadawey and Zammit-Maempel7

The disease process begins at the osseous-cartilaginous junction and then spreads rapidly through soft tissue, cartilage and bone, causing necrosis of these tissues. Secondary involvement of the cranial nerves, in particular the facial nerve and the lower cranial nerves (IX, X and XI), is suggestive of skull base involvement.Reference Sudhoff, Rajagopal, Mani, Moumoulidis, Axon and Moffat12 Facial nerve paralysis is usually the first neurological abnormality to develop, and indicates involvement of the stylomastoid foramen.Reference Salit, McNeely and Chait13 Although facial nerve involvement is an indicator of progression of necrotising external otitis, it is not a sign of adverse prognosis, as the majority of patients with facial nerve paralysis proceed to full recovery.Reference Soudry, Joshua, Sulkes and Nageris14

Treatment is primarily with long term antibiotics, although aggressive debridement and hyperbaric oxygen may be required for resistant cases. Although rare, necrotising external otitis is a potentially fatal disease, with complications which include temporomandibular joint (TMJ) osteomyelitis, sigmoid sinus thrombosis and meningitis. With aggressive, timely treatment, mortality rates have been reduced from 50 per cent to 10–20 per cent.Reference Bhandary, Karki and Sinha15

Reaching a definite diagnosis of necrotising external otitis is frequently difficult. A combination of a high index of clinical suspicion, laboratory investigation, imaging and histological evaluation (to exclude malignancy) all play a role. Clinical features such as refractory external otitis, severe otalgia, purulent exudate, granulation tissue, presence of P aeruginosa, cranial nerve palsies and diabetes (or an immunocompromised state) should all raise suspicion of necrotising external otitis.

Both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide excellent resolution of soft tissue infection in the subtemporal region and the stylomastoid foramen. Computed tomography is sensitive to bone erosion and decreased skull base density, and is of particular value in assessing the middle ear, mastoid, bony facial nerve canal, petrous apex and carotid canal.Reference Grandis, Curtin and Yu16 However, in the early stages of osteomyelitis, before bone demineralisation has occurred, bony changes may not be evident on CT.Reference Sreepada and Kwartler17 Although the presence of bone erosion is an important feature aiding the initial diagnosis of necrotising external otitis, it does not correlate closely with the clinical outcome.Reference Sudhoff, Rajagopal, Mani, Moumoulidis, Axon and Moffat12 Magnetic resonance imaging provides added benefit in assessment of the parotid region, meninges and medullary bone spaces.Reference Grandis, Curtin and Yu16 Retrocondylar fat infiltration has been proposed as one of the most frequent diagnostic findings in patients with necrotising external otitis.Reference Kwon, Han, Oh, Song and Chang18 In our unit, CT is usually performed as the first line of investigation when necrotising external otitis is suspected, because it is readily available, faster, and capable of identifying bony erosion and soft tissue masses. We reserve MRI for patients with suspected intracranial involvement, and those who pose a diagnostic problem.

However, CT and MRI are limited in determining disease resolution if changes persist despite effective treatment.Reference Grandis, Curtin and Yu16

Nuclear medicine imaging has also been used for the diagnosis and follow up of necrotising external otitis cases; modes have included three phase technetium Tc99m methylene diphosphonate scintigraphy (bone scan), technetium-99 hexamethyl propylene amine oxime white cell scintigraphy white cell scintigraphy, and gallium Ga 67 scintigraphy.

Bone scanning is relatively rapid, inexpensive and easy to perform. It has a high sensitivity for detecting osteomyelitis, but is not specific for infection (as it can also be positive in malignancy and trauma), and does not detect soft tissue spread without bone involvement.Reference Grandis, Branstetter and Yu10, Reference Carfrae and Kesser11, Reference Amorosa, Modugno and Pirodda19 Bone scans also remain positive until cessation of osteoblastic activity, which may occasionally persist long after the infection has been eradicated; therefore, this imaging modality is of limited suitability when assessing the response to therapy.Reference Carfrae and Kesser11

The radiolabelled technetium white cell scan has a predilection for reticular endothelial systems; however, it is expensive, laborious, and may be negative in the presence of low-grade infection.Reference Okpala, Siraj, Nilssen and Pringle20

Gallium citrate is absorbed by macrophages and reticular endothelial cells and concentrates in areas of active inflammation, including soft tissue and bone infections.Reference Stokkel, Boot and van Eck-Smit21 Gallium scans quickly return to normal after the infection has settled, and can be used for radiological assessment of the response to therapy.Reference Slattery and Brackmann22 However, gallium imaging is expensive, time-consuming, and delivers a significantly higher radiation dose than bone or white cell scans. It also provides poor anatomical detail, which reduces its effectiveness as the initial imaging modality.

Some authors recommend the use of bone scans following treatment of necrotising external otitis, and the subsequent use of gallium scanning should the bone scan be positive despite apparent clinical resolution of the infection.Reference Okpala, Siraj, Nilssen and Pringle20 Our unit uses CT or MRI scanning at least three months after commencing treatment, to evaluate response, as earlier imaging does not usually show much change, and this protocol enables a full course of antibiotics to be administered prior to re-imaging. Radiological changes do improve with time, but minor soft tissue changes persist even if imaging is performed a year later.

Necrotising external otitis has a variety of clinical presentations, and consequently a broad range of radiological appearances. It is important to point out that patients presenting with otitis externa will usually have been treated with short courses of antibiotics prior to radiology being requested, such that there may be no clinical or radiological abnormality in the external auditory canal. Despite this, there may be a soft tissue mass below the skull base, with or without osteomyelitis. In addition, as imaging is now being performed earlier and earlier on at-risk patients, skull base erosion may not necessarily be present, and thus should not be used as the only criterion with which to diagnose necrotising external otitis.

In this review, we present the imaging characteristics of a number of patients presenting to our unit with necrotising external otitis. We also discuss the likely spread of infection, and the diagnostic difficulties faced by the radiologist.

Spectrum of disease

Necrotising external otitis usually begins insidiously at the osseous-cartilaginous junction as a focal area of ulceration and osteitis of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). The tympanic membrane is usually resistant to the infectious process. The disease usually extends inferiorly via tiny clefts in the cartilaginous portion of the external auditory canal (the fissures of Santorini), allowing access to the soft tissues beneath the temporal bone, around the stylomastoid foramen and the temporal fossa (Figures 2 to 4). Facial palsy may occur as a result of mastoid destruction, or more commonly due to subtemporal spread of infection to the stylomastoid foramen (Figure 2). Infection may extend posteriorly onto the mastoid process.

Fig. 1 Axial computed tomography scan demonstrating localised disease with external auditory canal involvement. Abnormal soft tissue is seen in the right external auditory canal, in a patient who presented with right-sided otalgia and otorrhoea (arrowhead). Subtle erosion of the anterior wall of the external auditory canal is also seen (arrow).

Fig. 2 Axial, T1-weighted, unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan, demonstrating a soft tissue mass around the left carotid artery, jugular vein and styloid process, extending into the parotid space (arrow).

Fig. 3 Axial computed tomography scan demonstrating abnormal soft tissue in the left skull base, around the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein (black arrowhead), with streakiness in the parapharyngeal space (arrow). Note the normal parapharyngeal space on the opposite normal side (white arrowhead).

Fig. 4 Axial computed tomography scan demonstrating a large mass lying medially in the right skull base (white arrow) with bulging of the right nasopharyngeal wall. Note that the mass extends around the right internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, temporomandibular joint and parotid gland.

From the infratemporal region, infection can rapidly spread anteriorly to involve the TMJ and parotid gland (Figure 5). Temporomandibular joint pain may be the first presentation of necrotising external otitis.

Fig. 5 (a) Axial computed tomography scan demonstrating a large soft tissue mass in the right skull base, centred around the TMJ and extending to the right parotid gland (arrow). (b) Coronal reconstruction demonstrating displacement of the right mandibular condyle inferiorly and laterally (arrow).

Medial extension of infection to involve the jugular foramen can result in palsies of the IXth to XIth cranial nerves (Figure 6). The vagus nerve is usually the first of these cranial nerves to be affected, with associated symptoms such as altered voice quality, dysphagia and vocal fold palsy. Palsies of the XIIth, XIth and then IXth cranial nerves subsequently follow, with speech and swallowing difficulties and shoulder weakness.

Masses can occasionally be bilateral and central, thereby mimicking a nasopharyngeal tumour. Patients can present to general medical teams because of vague symptoms, prompting brain (rather than skull base) imaging views masses below the skull base may be overlooked (Figure 7). Skull base osteomyelitis can subsequently develop (Figures 8 and 9).

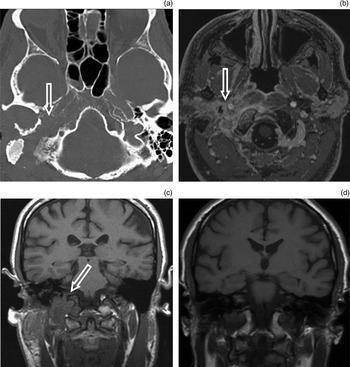

Fig. 6 Imaging findings for jugular foramen destruction. (a) Axial computed tomography scan showing bony destruction of the right side of the skull base, localised to the jugular foramen. (b) Axial, fat-suppressed, T1-weighted, post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing an infiltrative, enhancing mass extending onto the parotid gland. (c) Coronal, T1-weighted, unenhanced MRI showing a mass and loss of marrow signal in the region of the right jugular foramen and occipital condyle (arrow). (d) Coronal MRI scan performed two years later for separate symptoms, showing that the above changes have largely resolved.

Fig. 7 Axial computed tomography demonstrating a large, central nasopharyngeal mass (arrow); such lesions can mimic malignancy.

Fig. 8 Imaging findings for clivus and basiocciput involvement. (a) Axial computed tomography scan showing extensive destruction of the right basiocciput and clivus (arrow). (b) Axial, T1-weighted, unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan showing loss of the normal high marrow signal (arrow).

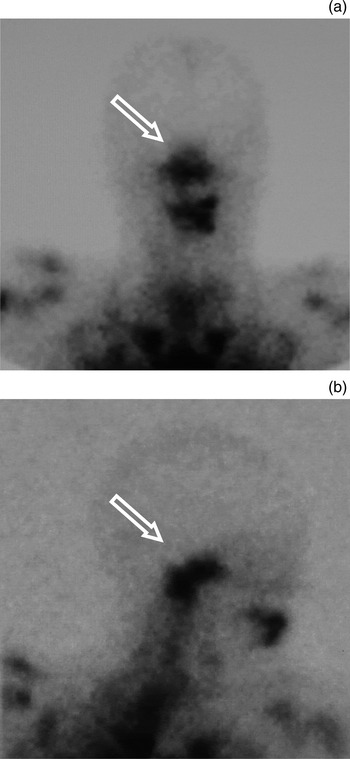

Fig. 9 (a) Anteroposterior and (b) right lateral views of technetium white cell imaging in a patient with necrotising external otitis, demonstrating increased uptake in the region of the skull base (arrows); however, note poor anatomical resolution.

Furthermore, extension through the petroclival (petro-occipital) synchondrosis can result in intracranial involvement, with secondary meningitis, abscess formation and sinus thrombosis (Figures 10 and 11). Infection can spread caudally down the spinal canal. Sigmoid sinus and jugular thrombosis may also occur due to intense inflammation around the jugular fossa (Figure 11).

Fig. 10 Imaging findings for meningeal enhancement secondary to necrotising external otitis. (a) Coronal and (b) axial, post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging scans for a patient with necrotising external otitis, demonstrating intense dural enhancement due to meningeal extension of disease. Note extension along the left tentorium (a; arrow), and along the left internal auditory meatus and prepontine cistern (b; arrow and arrowhead, respectively).

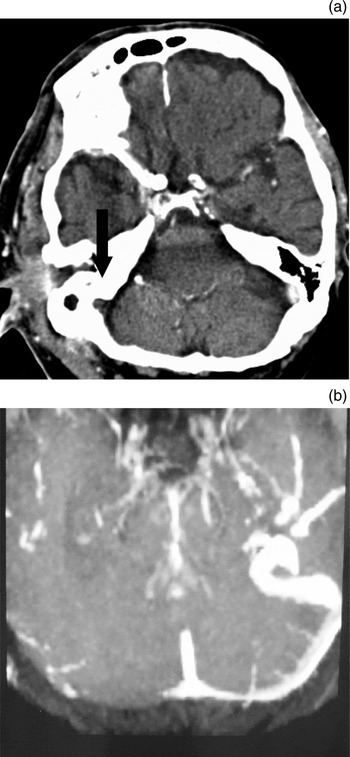

Fig. 11 Imaging findings for dural sinus thrombosis. (a) Axial, contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan demonstrating right sigmoid sinus thrombosis (arrow); also note the periauricular soft tissue mass. (b) Axial magnetic resonance imaging venogram demonstrating right transverse sinus thrombosis in the same patient (with necrotising external otitis).

Conclusion

Necrotising external otitis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The imaging findings in the early stages are frequently subtle, and even in advanced cases the findings may not be recognised unless there is a high index of clinical suspicion. Computed tomography, MRI and isotope scanning all have a role to play in the diagnosis and follow up of necrotising external otitis.