Introduction

Irritability is an important yet understudied symptom domain in adult patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Hwang, Rush, Sampson, Walters and Kessler2010; Judd, Schettler, Coryell, Akiskal, and Fiedorowicz, Reference Judd, Schettler, Coryell, Akiskal and Fiedorowicz2013). While it is reported by over half of adult patients with MDD (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Hwang, Rush, Sampson, Walters and Kessler2010; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Schettler, Coryell, Akiskal and Fiedorowicz2013), it is neither prominently highlighted by the NIMH Research Domain Criteria nor assessed by commonly used measures of depression severity (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow, Klein and Keller2003), reflecting its lack of inclusion as a diagnostic criterion symptom for MDD in adults (Association, 2013). Importantly, its presence or worsening is associated with earlier age of onset, greater disability, and poorer long-term clinical course (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Hwang, Rush, Sampson, Walters and Kessler2010; Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush, & Trivedi, Reference Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush and Trivedi2018; Judd et al. Reference Judd, Schettler, Coryell, Akiskal and Fiedorowicz2013). A recent report highlighted the clinical utility of measuring irritability within the context of two separate 8-week long acute-phase antidepressant trials (Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush, & Trivedi, Reference Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush and Trivedi2019). Authors found that irritability improved from baseline-to-week-4 and this improvement predicted remission (none or minimal depression) and no-meaningful-benefit (<30% reduction in depression) at week-8, both independent of baseline-to-week-4 improvement in depression (Jha, Minhajuddin, et al., Reference Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush and Trivedi2019). This report addresses the central question those findings raised-of how patients' self-report of irritability symptoms associated with measures of overt behaviors such as anger attacks (Pine, Reference Pine2019).

Anger attacks are bouts of anger that start suddenly, are disproportionate to the situation, are not part of the patient's usual behavior, and are associated with autonomic activation (Fava, Anderson, & Rosenbaum, Reference Fava, Anderson and Rosenbaum1990). In the Massachusetts General Hospital Anger Attacks Questionnaire (AAQ), Fava and colleagues operationalize the presence of anger attacks as patient's report of irritability and overreaction to minor annoyances in the past 6 months along with at least one episode of an anger attack in the past month that is accompanied by autonomic arousal and/or violent behavior (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Anderson and Rosenbaum1990, Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, McCarthy, Pava, Steingard and Bless1991, Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993). Typically, over a third of patients with MDD meet the criteria for the presence of anger attacks (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, McCarthy, Pava, Steingard and Bless1991).

Fava et al. have previously reported that while levels of depressive symptoms were similar, patients with anger attacks had significantly higher levels of anxiety, somatization, and hostility symptoms than patients without anger attacks (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993). Further, they found a greater reduction in hostility but not in depressive, anxiety, and somatization symptoms with antidepressant treatment in patients with anger attacks than those without anger attacks (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993). Other groups have reported similar findings. For example, Painuly et al. previously found in a small study that depressed patients with anger attacks (n = 20) had significantly higher levels of irritability and anxiety than patients without anger attacks (n = 20) (Painuly, Sharan, & Mattoo, Reference Painuly, Sharan and Mattoo2007). In a subsequent report with a larger sample size (n = 328), they replicated these findings of elevated irritability and anxiety in patients with anger attacks than those without anger attacks (Painuly, Grover, Gupta, & Mattoo, Reference Painuly, Grover, Gupta and Mattoo2011). Additionally, they found that the frequency of anger attacks was positively correlated with irritability and aggression (Painuly et al., Reference Painuly, Grover, Gupta and Mattoo2011). Taken together, these reports suggest that patients with anger attacks have similar levels of depression but higher levels of irritability and anxiety than patients without anger attacks (Fava, Reference Fava1998). Additionally, the presence of anger attacks may be associated with greater reduction in irritability but not in depression or anxiety symptoms with acute-phase antidepressant treatment.

Aim of the study

Using a sample of convenience from the Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response in Clinical Care (EMBARC) study, a double-blind placebo controlled randomized study of sertraline for 8-weeks, this report aims to evaluate the following specific questions:

(1) Do adult outpatients with MDD and anger attacks differ on levels of depression, anxiety, hostility, and irritability at baseline from those without anger attacks?

(2) If yes, do patients with a higher frequency of anger attacks have higher levels of these symptoms at baseline?

(3) Does the presence of anger attacks at baseline predict changes in depression, anxiety, and irritability with acute-phase antidepressant treatment?

(4) If yes, does treatment arm (sertraline v. placebo) affect this association?

Additional analyses evaluated the association of anger attack and irritability with depressive episode subtypes (melancholic or atypical) and with participants' self-reported feelings of hostility. As anger attacks may occur without overt aggressive behaviors and the first item assesses about the presence of irritability over the past 6 months, additional analyses were conducted based on the presence of overt aggressive behaviors. Hence, participants who reported aggressive behavior on AAQ were compared to those with no aggressive behaviors on measures of depression, anxiety, and irritability at baseline and with acute-phase antidepressant treatment. Findings of this report will elucidate the association among constructs of anger, hostility, and irritability, which while related are not completely redundant (Orri, Perret, Turecki, & Geoffroy, Reference Orri, Perret, Turecki and Geoffroy2018).

Material and methods

Study design and participants

EMBARC study

As previously described (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, McGrath, Fava, Parsey, Kurian, Phillips and Weissman2016, Reference Trivedi, South, Jha, Rush, Cao, Kurian and Fava2018), the EMBARC study (NCT01407094) enrolled 309 participants with MDD at four-sites. Of these, 10 were in a feasibility sample and 3 were randomized but were not eligible for the study (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, McGrath, Fava, Parsey, Kurian, Phillips and Weissman2016). Of the 296 participants with MDD who were randomized either to sertraline or to placebo, 3 did not complete the AAQ at baseline. Thus, the modified intent to treat sample for this report includes n = 293 participants with MDD with n = 149 randomized to placebo and n = 144 randomized to sertraline. Institutional review boards at each site approved the study and all participants provided signed an informed consent prior to completing any study-related procedures. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, McGrath, Fava, Parsey, Kurian, Phillips and Weissman2016) and are listed in detail at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01407094. Briefly, participants were 18–65 years of age, met criteria for current episode of MDD on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002), scored ⩾14 on Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR) at both screening and randomization visits, did not meet criteria for any failed antidepressant trial in the current episode based on Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (Chandler, Iosifescu, Pollack, Targum, & Fava, Reference Chandler, Iosifescu, Pollack, Targum and Fava2010), and agreed to and were eligible for all biomarker procedures (electroencephalography, psychological testing, magnetic resonance imaging, and blood draws). Participants were excluded if they did not tolerate sertraline or bupropion in the past, were pregnant/breastfeeding/planning to become pregnant, were medically or psychiatrically unstable, met criteria for psychotic/bipolar disorder in lifetime or substance abuse in past 2 months or substance dependence in past 6 months, or were on prohibited concomitant medications (antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, mood stabilizers, central nervous system stimulants, daily use of benzodiazepines or hypnotics, or antidepressants).

Measurements

Anger attacks

At the baseline visit of the EMBARC study, participants completed the AAQ (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Anderson and Rosenbaum1990). Using this self-report questionnaire, participants were categorized as either with anger attacks or without anger attacks present per Fava et al.: ‘classified as having anger attacks if they exhibited the following four criteria over the previous 6 months: (1) irritability, (2) overreaction to minor annoyances, (3) occurrence of anger attacks, at least one of which occurred within the past months, and (4) experience during at least one of the attacks of four or more of the following: tachycardia, hot flashes, chest tightness, paresthesia, dizziness, shortness of breath, sweating, trembling, panic, feeling out of control, feeling like attacking others, attacking physically or verbally, and throwing or destroying objects’ (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993). Additionally, participants with anger attacks were asked to report the frequency of attacks in the past month as following categories: 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9 or more (⩾9). Those participants who responded with ‘Yes’ to AAQ items regarding ‘physically or verbally attacking people’ and/or ‘throwing things around or destroying objects’ were grouped as participants with aggressive behavior present while others were categorized as without aggressive behavior.

Depression severity

Clinicians conducted the structured interview (Williams, Reference Williams1988) for the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) to assess depression severity at each visit of the EMBARC study. Previous reports have found high concurrent validity of HAMD-17 with other measures of depression severity such as the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (Vittengl, Clark, Kraft, & Jarrett, Reference Vittengl, Clark, Kraft and Jarrett2005). During screening and baseline visits, patients also completed the 16-item QIDS-SR scale.

Anxiety

Participants completed the three-item anxiety domain of the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale (CAST-ANX) at each visit of the EMBARC study. Individual items included, ‘I feel anxious all the time,’ ‘I am feeling restless, as if I have to move constantly,’ and ‘I cannot sit still.’ These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses of ‘strongly disagree,’ ‘disagree,’ ‘neither agree nor disagree,’ ‘agree,’ and ‘strongly agree’ corresponding to scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 with a total score range of 3–15. Previous reports have found strong psychometric properties of the CAST-ANX domain (Jha et al., Reference Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush and Trivedi2018; Minhajuddin, Jha, Chin Fatt, & Trivedi, Reference Minhajuddin, Jha, Chin Fatt and Trivedi2020; Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Wisniewski, Morris, Fava, Kurian, Gollan and Rush2011).

Irritability

Participants completed the five-item irritability domain of the CAST scale (CAST-IRR) as a measure of irritability at each visit of the EMBARC study and the CO-MED trial. Individual items included, ‘I wish people would just leave me alone,’ ‘I feel very uptight,’ ‘I find myself saying or doing things without thinking,’ ‘Lately everything seems to be annoying me,’ and ‘I find people get on my nerves easily.’ These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses of ‘strongly disagree,’ ‘disagree,’ ‘neither agree nor disagree,’ ‘agree,’ and ‘strongly agree’ corresponding to scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 with a total score range of 5–25. Previous reports have found strong psychometric properties of the CAST-IRR domain (Jha et al., Reference Jha, Minhajuddin, South, Rush and Trivedi2018; Minhajuddin et al., Reference Minhajuddin, Jha, Chin Fatt and Trivedi2020; Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Wisniewski, Morris, Fava, Kurian, Gollan and Rush2011).

Hostility

Using a Visual Analogue of Mood Scales (VAMS) at baseline, participants rated their current mood as hostile—friendly on 250 mm horizontal lines (Pizzagalli et al., Reference Pizzagalli, Evins, Schetter, Frank, Pajtas, Santesso and Culhane2008; Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, McGrath, Fava, Parsey, Kurian, Phillips and Weissman2016). These responses were converted on a 100-point scale with lower scores indicating more hostile mood.

Presence of melancholic or atypical features

Clinicians completed current major depressive episode specifier module of SCID to identify the presence of melancholic or atypical features (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002). The presence of melancholic features was determined by the affirmative response to either ‘loss of pleasure in all, or almost all activities’ or ‘lack of reactivity to usually pleasurable activity’ along with the presence of three or more of following: distinct quality of mood, depression worse in morning, early morning awakening, marked psychomotor retardation or agitation, significant anorexia or weight loss, and excessive or inappropriate guilt. The presence of atypical features were identified by the presence of mood reactivity (brightening of mood in response to an actual or potential positive event) along with of two or more of the following features: significant weight gain or increase in appetite, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and longstanding pattern of interpersonal rejection sensitivity.

Statistical analysis plan

As reported earlier, the modified intent to treat sample includes all EMBARC study participants who were randomized to sertraline or placebo and completed AAQ at baseline (n = 293). Independent sample t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare continuous and categorical features, respectively, between participants with anger attacks and those without anger attacks at baseline. For symptoms that differed significantly, analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare their levels based on the frequency of anger attacks in the past month (categorized as 1–2, 3–4, 5–8, and ⩾9). When applicable, Cohen's d effect size (d) was estimated to convey the magnitude of differences in levels of symptoms (depression, anxiety, hostility, and irritability). To evaluate if baseline anger attacks predicted changes in depression, anxiety, and irritability, repeated measures mixed model analyses were used with depression, anxiety, and irritability as the dependent variable in separate models, along with anger attacks, time, and time-by-anger attacks interaction as key independent variables of interest, and select baseline variables (age, sex, site, race, and ethnicity) as covariates. As repeated-observations for VAMS were not available, hostility was not included as an outcome in mixed model analyses. For symptoms with a significant time-by-anger attacks interaction, mixed model analyses were repeated and included a three-way interaction term (time-by-anger attacks-by-treatment arm) for time, anger attacks, and treatment arm (sertraline or placebo) to evaluate if treatment arms moderated the association between baseline anger attacks and changes in symptom levels. To evaluate if the presence of aggressive behaviors affected our analyses, we also compared depressed patients with aggressive behavior to those without aggressive behavior.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and threshold of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

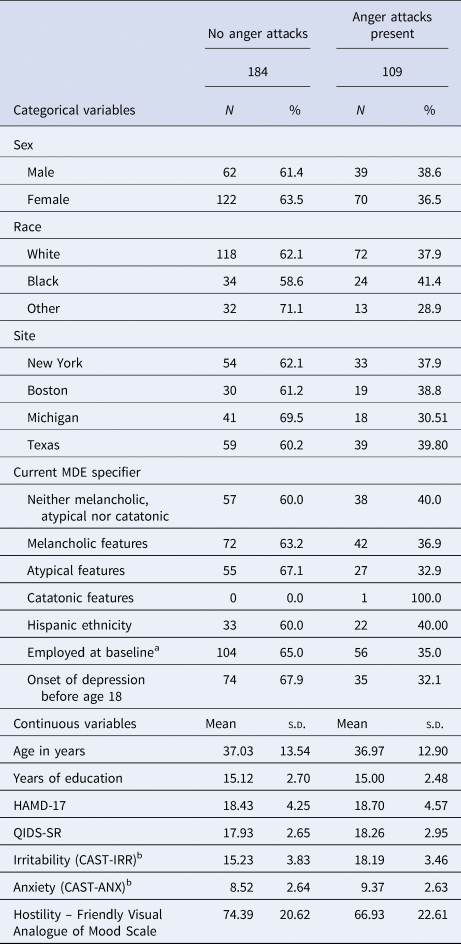

Baseline characteristics of EMBARC study participants with (37.2%, 109/293) and without (62.8%, 184/293) anger attacks are reported in Table 1. Of those participants with anger attacks, 40.4% (44/109), 29.4% (32/109), 17.4% (19/109), and 12.8% (14/109) reported 1–2, 3–4, 5–8, and ⩾9 attacks in past 1 month, respectively. The proportion of participants with melancholic or atypical features was similar in those with anger attacks and those without anger attacks, see Table 1. Similarly, levels of irritability were similar in participants with melancholic features [mean = 16.27, standard deviation (s.d.) = 4.01], atypical features (mean = 16.35, s.d. = 3.77), or neither (mean = 16.36, df = 4.12).

Table 1. Clinical and demographic differences in EMBARC study participants with and without anger attacks

HAMD-17 is 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, QIDS-SR is 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report, CAST-IRR and CAST-ANX are irritability and anxiety domains respectively of Concise Associated Symptom Tracking Scale.

a Missing n = 4.

b Missing n = 1.

Do adult outpatients with MDD with anger attacks differ on levels of depression, anxiety, hostility, and irritability at baseline from those without anger attacks?

Yes, but only on levels of anxiety, hostility, and irritability. Levels of depression, as measured by HAMD-17 (t = −0.50, df = 214, p = 0.620) and QIDS-SR (t = −0.94, df = 208, p = 0.350), did not differ between participants with anger attacks and those without anger attacks (Table 1). Participants with anger attacks had significantly higher levels of anxiety (t = −2.66, df = 225, p = 0.008, d = 0.32), hostility (t = −2.82, df = 211, p = 0.005, d = 0.35), and irritability (t = −6.80, df = 243, p < 0.0001, d = 0.80), also see Table 1. Higher scores on irritability were associated with greater hostility (Pearson's r = 0.34, p < 0.0001).

Do patients with higher frequency of anger attacks have higher levels of irritability and anxiety at baseline?

Yes. Among participants with anger attacks, there was a statistically significant difference in levels of irritability (F = 5.74, df = 3, 104, p = 0.001; Fig. 1, Panel A) and anxiety (F = 4.41, df = 3, 104, p = 0.006; Fig. 1, Panel B) on the basis of the frequency of anger attacks in the past month. In post hoc tests, the magnitude of difference between participants with 5–8 and ⩾9 attacks in levels of irritability (d = 0.16) and anxiety (d = 0.42) was small (Cohen, Reference Cohen2013). However, participants with 5–8 attacks had higher levels of irritability than those with 3–4 (d = 0.64) and 1–2 (d = 0.87) attacks. Similarly, participants with ⩾9 attacks had higher levels of irritability than those with 3–4 (d = 0.80) and 1–2 (d = 1.01) attacks. Participants with 5–8 attacks also had higher levels of anxiety than those with 3–4 (d = 0.71) and 1–2 (d = 1.08) attacks. Anxiety in participants with ⩾9 attacks was either of similar magnitude or moderately higher than those with 3–4 (d = 0.28) or 1–2 (d = 0.56) attacks.

Fig. 1. Baseline irritability and anxiety in EMBARC study participants with anger attacks (n = 108 (Among participants with anger attacks (n = 109), one participant with 3–4 anger attacks in the past 1 month had missing data for irritability and anxiety domains of Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale (CAST) in the EMBARC study)) based on the frequency of attacks in past 1 month.

Does the presence of anger attacks at baseline predict changes in depression, anxiety, and irritability with acute-phase antidepressant treatment?

Yes, but only for changes in irritability. There was no significant week-by-anger attacks interaction for depression (unadjusted p = 0.813) and anxiety (unadjusted p = 0.771) symptoms with acute-phase antidepressant treatment, see Table 2. There was a significant week-by-anger attacks interaction for irritability (p = 0.045 after Bonferroni adjustment). While participants with anger attacks experienced greater reduction in irritability, their irritability levels remained significantly higher than those of participants without anger attacks throughout the acute-phase antidepressant treatment period (Fig. 2, Panel A). The observed mean (s.d.) scores of CAST-IRR at week-8 in participants with (n = 87) anger attacks and those without anger attacks (n = 146) were 14.22 (5.08) and 12.76 (4.33) respectively (d = 0.32). In contrast, anxiety levels were no longer different at week-8 (Fig. 2, Panel B) between participants with and without anger attacks.

Fig. 2. Changes in irritability and anxiety among participants with and without anger attacks in the EMBARC study. Legends: EMBARC is the Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care study. LS means are least square means obtained from repeated measures mixed model analyses. CAST is Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale.

Table 2. Mixed model analyses of changes in depression, anxiety, and irritability based on the presence of anger attacks at baseline

p* is the p value after Bonferroni adjustment (three independent variables of interest in these three mixed model analyses). All mixed model analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and site.

Does treatment arm (sertraline v. placebo) affect the association between baseline anger attacks and changes in irritability with antidepressant treatment?

No. The three-way interaction of week-by-anger attack-by-treatment arm was not significant in predicting changes in irritability (F = 0.50, df = 1, 1401, p = 0.835).

Exploratory analyses with aggressive behaviors

Of the 293 participants, 84 (28.5%) reported physically/verbally attacking people, 55 (18.8%) reported throwing things around/destroying objects, and 96 (32.8%) reported either one or both aggressive behaviors. Of the 96 participants with aggressive behavior, 86 (89.6%) met criteria for anger attacks. Participants with aggressive behavior had higher irritability (mean = 18.35, s.d. = 3.55; t = −6.55, df = 290, p < 0.0001, d = 0.82) than those without aggressive behaviors (mean = 15.33, s.d. = 3.77). Levels of anxiety (p = 0.075) and depression (p = 0.510) at baseline did not differ on the basis of aggressive behaviors. Furthermore, there was no significant week-by-aggressive behaviors interactions for changes in depression (unadjusted p = 0.760) and anxiety (unadjusted p = 0.642) during acute-phase antidepressant treatment. While participants with aggressive behaviors experienced greater reduction in irritability, their irritability levels remained significantly higher than those of participants without aggressive behaviors even after acute-phase antidepressant treatment (see online Supplementary Table ST2 and Fig. SF1).

Conclusions

In this report of a large sample of adult outpatients with MDD, we extended the clinical utility of measuring irritability by demonstrating its association with overt behavior of anger attacks. In our sample, over a third of patients met criteria for anger attacks. These patients had significantly higher levels of irritability and anxiety as compared to those without anger attacks. While anxiety levels were no longer different after acute-phase antidepressant treatment, patients with anger attacks continued to report higher levels of irritability than those without anger attacks even after 8 weeks of treatment. When only the presence of aggressive behaviors was considered, those with these behaviors had significantly higher levels of irritability at baseline than those without aggressive behavior, and this difference persisted even after acute-phase antidepressant treatment. The association between baseline anger attacks and persistently elevated irritability post-treatment was not moderated by the treatment arm (sertraline v. placebo).

Our findings of elevated levels of anxiety and irritability in adult depressed patients with anger attacks are consistent with previous reports (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993; Painuly et al., Reference Painuly, Sharan and Mattoo2007). Additionally, our findings of greater reduction in irritability but not in depression and anxiety among patients with anger attacks compared to those without anger attacks is consistent with the report of Fava et al. (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Rosenbaum, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993) where patients with anger attacks experienced greater reduction in hostility, a construct related to irritability, but not in depression or anxiety symptoms with fluoxetine treatment. These findings argue for systematic assessment of irritability as part of a measurement-based care protocol for the treatment of depression Trivedi et al. (Reference Trivedi, Jha, Kahalnik, Pipes, Levinson, Lawson and Greer2019), which may allow validation of these findings in real-world clinics (Jha, Grannemann, et al., Reference Jha, Grannemann, Trombello, Clark, Eidelman, Lawson and Trivedi2019) and further enhance their generalizability.

We found in our sample that higher frequency of anger attacks was linearly associated with irritability but not with anxiety. While irritability and anxiety often exist together and are correlated, recent reports from the developmental literature suggest that their neural mechanisms may be distinct (Kircanski et al., Reference Kircanski, White, Tseng, Wiggins, Frank, Sequeira and Brotman2018; Stoddard et al., Reference Stoddard, Tseng, Kim, Chen, Yi, Donahue and Leibenluft2017). To our knowledge, similar studies have not been done in adults. Findings of this report also elucidate association among constructs of anger attacks, aggressive behavior, hostility, and irritability. Aggressive behavior was common among those with anger attacks with 78.8% (86/109) reporting either one or both aggressive behaviors. The range of irritability and hostility levels in participants with anger attacks partially overlapped with that of participants without attacks. Furthermore, while higher levels of irritability were associated with greater hostility, the two measures had a shared variance of 12.5% only. Future studies should comprehensively evaluate these symptoms and behavior constructs to determine their shared v. unique variance and include assessments from clinicians and other observers in patients' lives such as family members or co-workers. Findings from our report also argue for systematic screening of anger attacks as it may identify a group of adult patients with MDD who experience persistently elevated irritability, which in turn has been associated with poorer long-term outcomes (Judd et al., Reference Judd, Schettler, Coryell, Akiskal and Fiedorowicz2013).

Earlier work by Fava and colleagues suggests that patients with anger attacks may have distinct biological underpinnings of their illness. They have previously shown a blunted prolactin response to both thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulation (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Fava, Pava, McCarthy, Steingard and Bouffides1993) and fenfluramine challenge (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Vuolo, Wright, Nierenberg, Alpert and Rosenbaum2000) in patients with anger attacks, which they linked to dysregulation of serotonergic neurotransmission (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Vuolo, Wright, Nierenberg, Alpert and Rosenbaum2000). However, it may also be related to aberrant dopaminergic neurotransmission, given dopamine's inhibitory effect on prolactin secretion (Fitzgerald & Dinan, Reference Fitzgerald and Dinan2008). Consistent with this notion, Dougherty et al., found evidence for down-regulation of dopamine receptors in the striatum of patients with MDD and anger attacks as compared to healthy controls (Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Bonab, Ottowitz, Livni, Alpert, Rauch and Fischman2006).

The additional biological relevance of anger attacks may be found in its association with cardiovascular and metabolic pathology. Fava et al. had initially observed that patients with anger attacks had higher cholesterol levels than those without anger attacks (Fava, Abraham, Pava, Shuster, and Rosenbaum, Reference Fava, Abraham, Pava, Shuster and Rosenbaum1996). A subsequent study validated the association between anger attacks and elevated cholesterol levels and additionally found higher prevalence of smoking for >11 years among patients with anger attacks (Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, Iosifescu, Bankier, Perlis, Clementi-Craven, Alpert and Fava2007). Furthermore, in patients with MDD and anger attacks, plasma homocysteine levels correlated with length of current depressive episode and severity of symptoms, but no such association was seen MDD patients without anger attacks (Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, Papakostas, Mischoulon, Bottiglieri, Alpert and Fava2006). Reflecting this higher cardiovascular burden, Iosifescu et al. found that patients with anger attacks had higher severity of white matter hyperintensities overall and in subcortical regions as compared to those without anger attacks (Iosifescu et al., Reference Iosifescu, Renshaw, Dougherty, Lyoo, Lee, Fraguas and Fava2007). Future studies should systematically evaluate the role of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction in patients with anger attack and irritability (Van Praag, Reference Van Praag2001). Emerging evidence points bidirectional association (Gold & Kadriu, Reference Gold and Kadriu2019) between the HPA axis and lateral habenula, a key brain region in reward circuit that has been shown to modulate aggressive behavior in pre-clinical models (Flanigan et al., Reference Flanigan, Aleyasin, Li, Burnett, Chan, LeClair and Russo2019; Golden et al., Reference Golden, Heshmati, Flanigan, Christoffel, Guise, Pfau and Russo2016).

There are several limitations of this report. Findings of this report were obtained by unplanned secondary analyses, and as such they may not be adequately powered and should be considered preliminary. The presence of anger attacks was ascertained only at baseline. Thus, we cannot estimate the proportion of participants who no longer met criteria for anger attacks after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment. The assessments of anger attacks, aggression, hostility, and irritability were restricted to a self-report measure which differs from studies in youths where it is common to include assessments from parent/teacher(s) (Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine, & Leibenluft, Reference Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine and Leibenluft2017). As anger attack questionnaire explicitly asked for the presence of irritability in past 6 months, it may explain in part the overlap between the presence of anger attacks and irritability. However, additional analyses based on aggressive behaviors produced similar findings. Finally, the inclusion and exclusion criteria of our studies may make the findings of our study less generalizable to all MDD patients (Zimmerman, Balling, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, Reference Zimmerman, Balling, Chelminski and Dalrymple2019).

In conclusion, in this large sample of adult outpatients with MDD, we found that irritability is an important symptom domain which is associated with overt presentation of anger attacks. Additionally, the presence of anger attacks in adult patients with MDD may identify a sub-group of patients who have persistently elevated irritability despite acute-phase antidepressant treatment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000112.

Financial support

The EMBARC study was supported by NIMH grants U01MH092221 (to Dr Trivedi) and U01MH092250 (to Drs. McGrath, Parsey, and Weissman). This work was also funded in part by the Hersh Foundation (Dr Trivedi, principal investigator). The CO-MED trial was funded by NIMH under contract N01 MH-90003 to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (principal investigators, A.J. Rush and M.H. Trivedi). Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals provided medications for CO-MED trial at no cost. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. NIMH had no role in the drafting or review of the manuscript or in the collection or analysis of the data. The authors thank the clinical staff at each clinical site for their assistance with these projects; all of the study participants; Eric Nestler, M.D., Ph.D., and Carol A. Tamminga, M.D., for administrative support.

Conflict of interest

Ms. Wakhlu and Drs. Minhajuddin and Chin Fatt have no conflicts to report. Dr Jha has received contract research grants from Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development. Dr Fava has received research support from Abbot Laboratories Alkermes, American Cyanamid, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, BioResearch, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clintara, Cerecor, Covance, Covidien, Eli Lilly, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GlaxoSmithKline, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Hoffman-LaRoche, Icon Clinical Research, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen R&D, Jed Foundation, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Methylation Sciences, NARSAD, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Neuralstem, NIDA, NIMH, Novartis, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer, Pharmacia-Upjohn, Pharmaceutical Research Associates, Pharmavite, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Reckitt Benckiser, Roche Pharmaceuticals, RCT Logic (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions), Sanofi-Aventis US, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Synthelabo, Tal Medical, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has served as adviser or consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Acadia, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, AXSOME Therapeutics, Bayer, Best Practice Project Management, Biogen, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Biovail Corporation, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Cerecor, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Forum Pharmaceuticals, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmbH, i3 Innovus/Ingenis, Intracellular, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MSI Methylation Sciences, Naurex, Nestle Health Sciences, Neuralstem, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Osmotica, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic (Formerly Clinical Trials Solutions), Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis US, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Schering-Plough, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and VistaGen; he has received speaking or publishing fees from Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, AstraZeneca, Belvoir Media Group, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Imedex, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, Novartis, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PharmaStar, United BioSource, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has equity holdings in Compellis and PsyBrain; he has a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design, which are licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to Pharmaceutical Product Development, and a patent application for a combination of ketamine plus scopolamine in MDD, licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to Biohaven; and he receives royalties for the MGH Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire, the Sexual Functioning Inventory, the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire, Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms, the Symptoms of Depression Questionnaire, and SAFER, and from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Wolkers Kluwer, and World Scientific Publishing.

Dr Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals. He has provided unpaid consulting for Pharmavite LLC and Gnosis USA, Inc. He has received honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy, Blackmores, Harvard Blog, and PeerPoint Medical Education Institute, LLC. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for published book ‘Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives.’ Dr Cusin has received research support from Shenox. She has received consulting honoraria from Janssen, Takeda, Boehringer, Lundbeck, and Alkermes. She has received royalties from Springer for published book ‘The Massachusetts General Hospital Guide to Depression.’ Dr Trombello owns stock in Merck Pharmaceuticals and within the past 36 months owned stock in Gilead Sciences, both unrelated to the current project. Dr Trivedi has served as an adviser or consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Abdi Ibrahim, Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals), Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Axon Advisors, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Cerecor, CME Institute of Physicians, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Fabre Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Global Services, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, Johnson & Johnson PRD, Libby, Lundbeck, Meade Johnson, MedAvante, Medtronic, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Naurex, Neuronetics, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PgxHealth, Phoenix Marketing Solutions, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Products, Sepracor, Shire Development, Sierra, SK Life and Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Tal Medical/Puretech Venture, Targacept, Transcept, VantagePoint, Vivus, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has received grants or research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Cyberonics, NARSAD, NIDA, and NIMH.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.