INTRODUCTION

When the field of “Indian Ocean history” properly emerged in the second half of the twentieth century, it did so in a self-consciously comparative context. Many of those who participated in the early formulations of the Indian Ocean as a distinct field of historical study had in mind Fernand Braudel's classic two-volume study of the Mediterranean Sea (1st ed. 1949; 2d rev. ed. 1966), despite the many differences between the two spaces in terms of geographical layout, scale, and density of traffic.Footnote 1 Even the religious geography of the Indian Ocean appeared far more complex and layered than that of the early modern Mediterranean, which was schematically often divided along a straightforward Christian-Muslim axis of the sort which came to the fore during the celebrated Battle of Lepanto (1571). But this did not prevent Indian Ocean historians from liberally transferring arguments and models from the Mediterranean, even if notes of caution were periodically sounded.Footnote 2 Since then, other historians have been tempted by quite another comparison, with the Atlantic Ocean.Footnote 3 To be sure, here, too, the differences are striking between the two spaces. Unlike the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, the Atlantic only emerged as a two-sided zone of interaction at the very end of the fifteenth century, and when it did so the two sides had very different weights, since they were clearly organized at the two ends of a political and imperial spectrum until at least the end of the eighteenth century. Yet, it has become common enough for historians of various phenomena, be it colonial urbanism or the slave trade, to essay a comparison between the Atlantic and Indian Ocean spheres, and even transfer analytical models from the former to the latter as if this were the most natural of exercises. Taking as its principal space of analysis the western Indian Ocean, this essay points to the importance of understanding its specificity, and its distinctive institutional, economic, and political mechanisms in the early modern period. This is not to deny the eventual utility of comparisons—a question to which I will return by way of conclusion—but rather to ensure that we do not confuse the exercise of comparison itself with simple equivalence.Footnote 4

Figure 1. The Western Indian Ocean (prepared by Bill Nelson).

Now, it is a commonplace to speak of mobility in the western Indian Ocean, whether at the time of the Geniza records from Fatimid Cairo (tenth–twelfth centuries CE) or the thirteenth-century papers from the Red Sea port of Quseir, or in the centuries that followed.Footnote 5 Those who traveled included merchants, like the Jews of the Geniza documents, but also pilgrims, savants (such as the celebrated Ibn Battuta in the first half of the fourteenth century), mercenaries, and state-builders, as well as slaves and humble mariners. However, while some networks of mobility have been well studied—notably those between the Red Sea and Persian Gulf and western India—others remain somewhat in the shadows. Links between western India and East Africa were undoubtedly more complex geographically than those, let us say between India and Iran, in the centuries leading up to 1500, but they were also subject to what has (perhaps exaggeratedly) been called a relative historiographical “erasure.”Footnote 6 To the extent that it has been fully attended to, it is really for the modern period, notably after 1750, when the British Empire offered a joint political framework for the two areas.Footnote 7 Further, direct maritime linkages between the two areas were weaker and more convoluted in comparison to those that ran between western India and the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. Typically, therefore, contacts passed through either Gujarat, which apparently maintained links both with the Horn of Africa and the Swahili coast, or through the Hijaz and Hadramawt, to which shipping from Deccan ports like Chaul and Dabhol regularly made its way.Footnote 8

Regarding the Gujarat-East Africa link in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a well-known essay by Edward Alpers from the 1970s remains a good point of departure. In it, Alpers commented:

Before the arrival of the Portuguese in Indian Ocean waters, trade between India and East Africa was based primarily on the exchange of gold from southern Zambesia and ivory from the coastal hinterland of East Africa for cotton cloths from India and glass beads from both India and Venice. The importance of exotic trade goods for East Africa was vividly recounted in an early sixteenth-century Portuguese report, which suggested that “cloth and beads are to the Kaffirs what pepper is to Flanders and corn to us, because they cannot live without this merchandise or lay up their treasures of it.” Among the [other] items involved in the trade were rhinoceros’ horn, tortoise shell, and some slaves from East Africa, grain from India, and Chinese porcelain, which was transshipped in western India.

Alpers went on to suggest that the “fifteenth century may have witnessed important changes in both the personnel and organization of trade with the rise to prominence of the Muslim sultanate of Gujarat from 1392 and the domination of Indian Ocean trade by Gujarati merchants.” He was unable to provide many details, however, beyond citing the usual early sixteenth-century Portuguese sources (Tomé Pires and Duarte Barbosa), on the role played by the ports of Khambayat (Cambay) and Diu.Footnote 9 On the East African end, he noted the significance by the fourteenth century of Kilwa, Mombasa, and Mogadishu (on the Banadir coast), and then further north, of Berbera and Zayla‘ around the Horn of Africa.

The relative paucity of textual sources has meant that historians of the Swahili coast in the pre-1500 period have largely drawn their arguments in recent decades from archaeology, numismatics, and the occasional inscription. These arguments were initially set out in broad brush strokes, but we can discern far more precision in recent studies that trace a long history of trade and settlement on this coast prior to 1500.Footnote 10 Moreover, the archaeologist Mark Horton has set out a set of interesting hypotheses regarding what he terms a “hidden trade [between India and Africa] in a variety of commodities, such as cloth and beads, that were vital to the prosperity of the whole system, but which are seldom recorded in the texts.” Making comparisons based on a close study of material culture and artefacts, he has even suggested that “Indian artisans may have moved to East Africa, [and] Africans may have moved, as well, around the Indian Ocean, not as slaves but as genuine artisanal communities.” Despite the “currently insufficient evidence to reconstruct in detail the relationship between northwestern India and East Africa from the eleventh until the fourteenth centuries,” Horton goes on to argue, “it is clear that a complex interaction existed between the two regions involving the movement of commodities and artisans in both directions.”Footnote 11 However, the regions of India for which he makes this argument seem largely to be Gujarat and Sind. The Deccan only features in relation to one instance, that of an eleventh-century East African bronze lion figurine, “based upon contemporary Indian figurines, possibly from the Deccan region.”

EARLY PORTUGUESE CONTACTS AND CONFLICTS

The nature of the textual record obviously changes significantly after about 1500, with the Portuguese arrival in the western Indian Ocean, in ways that are both expected and unexpected. The anonymous shipboard account of Vasco da Gama's voyage along the Swahili coast in 1498 already marks this change. Rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the fleet had in late November 1497 initially encountered only pastoralists. But within a few weeks, sailing north, they found a settlement with thatched houses and inhabitants who were willing to trade copper for cloth. Not long thereafter, they encountered small coastal boats, and the first indications of a complex trading system, where one of their local interlocutors told them “that he had seen ships as large as those that we had brought.”Footnote 12 By early March, they were able to put in at Mozambique Island, where the Portuguese found that the inhabitants were not only numerous, but “of the sect of Muhammad and speak like Moors,” dressed in “rich and embroidered” clothes. There were also signs of the presence of “white Moors” from further up the coast, bringing cloth and spices in exchange for ivory and gold. Mozambique Island thus marked for them the southern limit of the spread of Islam along the coast at the time; and it was here that Gama engaged in his first armed conflicts with local populations, though he also managed to get hold of two Muslim pilots who reluctantly took his fleet as far as Mombasa, where they arrived in early April. Once in Mombasa, the pilots fled as quickly as they could, and Gama was eventually obliged to find another pilot—a Gujarati—in Malindi, who as we know conducted him across the western Indian Ocean to Calicut. It was in Malindi, moreover, that the Portuguese for the first time encountered Indian ships and merchants, though it is unclear from which region they originated.

The succeeding voyages between 1498 and 1505 obviously consolidated the trading knowledge of the Portuguese concerning the Swahili coast. They also led the Portuguese to make an initial bid for the gold trade of the region, using in exchange textiles purchased in India. To do this, they decided to build a fortress in Kilwa, a port with which they had duly established contact in 1500 through the fleet of Pedro Álvares Cabral. However, this fort, named Santiago by Dom Francisco de Almeida, was abandoned after a short existence in 1512 and the Portuguese then concentrated their activities elsewhere, in sites such as Sofala and Mozambique Island. As Malyn Newitt has noted, the gold trade “had fallen off sharply in the second decade of the century as the gold traders moved their operations to Angoche and as the wars among the Karanga chiefs in the interior interrupted the supply of gold to the fairs.”Footnote 13 The instinctive Portuguese response to this commercial failure was to attack rival trading networks, such as those based in the Querimba Islands (1523) and in Mombasa (1529). But these attacks produced little by way of trading success, so that their focus began to shift to the far more dispersed trade in ivory by the 1530s. This enterprise was, however, quickly transformed into the private business of the captains of Mozambique and individual Portuguese entrepreneurs, while (as Newitt notes), “the poverty-stricken royal factory at Sofala carried on virtually no trade at all.”

Nevertheless, these early years of Portuguese dealings produced some materials of interest to historians. The best known of these came into the possession of the official chronicler João de Barros, who was also the superintendent of the Casa da Índia in Lisbon, which oversaw trade on the Cape Route. We know that Barros had from the 1530s instructed a number of Portuguese who were in Asia to find materials that could help him fill in local historical details in his chronicle. From one such source came what he referred to in his Décadas as “a chronicle of the Kings of Kilwa (huma chronica dos Reys de Quiloa),” without stating precisely what language it was in.Footnote 14 This text speaks of the “Shirazi” settlement of the area and its alleged influence on the history of the city-state of Kilwa and its environs, suggesting that traders and other settlers from the interior Iranian city of Shiraz and/or the port city of Siraf arrived in the area several centuries before the Portuguese and played a crucial role there. An alternative narrative that has Muslim settlers arriving in the region from Daybul, at the mouth of the Indus, has also enjoyed some popularity in recent times.Footnote 15

Over the course of the sixteenth century, trade between India and the Swahili coast evolved to a fair extent, as the consequence of both Portuguese policies and other factors. The classic analysis by Edward Alpers of aspects of this commerce suggested that “it represented only a small part of India's total overseas trade,” not exceeding “four per cent of the total trade of Western India” even as late as 1600. He stressed the role of three commodities: cotton-textiles imported from India into Africa, and ivory and gold exported from Africa to India. Alpers proposed nevertheless that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, “the East African market for Indian cotton textiles was very small indeed when compared to the domestic market and to those of Arabia, Burma and Malacca.” On the other hand, he argued that “before about 1800 … the main market for the ivory of East Africa remained the traditional market from India.”Footnote 16 However, given the nature of the Portuguese records from the period, Alpers could not quantify either the imports or the exports of these commodities, let alone propose a reconstruction of trends over time. Some two decades after his important work, the Portuguese historian Manuel Lobato returned to the question with a closer look at the institutional context of trade, on which we shall draw extensively here.Footnote 17 It appears from Lobato's analysis that in a first phase, namely the 1510s and 1520s, as the Portuguese were engaged in Kilwa and Sofala, trade with India tended to focus on the port of Malindi and was largely carried on Gujarati ships. The Portuguese Estado's attitude to this trade was variable, as they episodically tried to come to an accord with the Sultan of Malindi, allowing ships from his port the use of their cartazes (safe-passes) to trade.

But Malindi-based merchants rarely felt safe in this period. For instance, in 1518, a Portuguese ship near the island of Soqotra captured “a nao of the Guzerates which they said was coming from Melynde to Canbaya, and its cargo was a great quantity of ivory, copper, coir, and other goods that might well be worth 12,000 or 15,000 pardaos, and 79 meticaes of gold and 150 of silver, and also many valuable Moors and captive slaves.”Footnote 18 Instead of carrying the prize to Goa, the Portuguese captain is said to have secretly sold the goods in Chaul and the ship in Diu. In letters from the Sultan of Malindi to the Portuguese ruler from around 1520–1521, he complained repeatedly of the behavior of the Portuguese in Malindi, with their “hard words and deeds towards us,” which included robbing some 9,500 xerafins worth of goods; he points a finger concretely at two Portuguese ships whose captains Rui Lourenço and João Fernandes “came to this port of Melindi and corrupted and destroyed it and seized goods in it, saying openly that Your Highness is aware of this and considers it good if the port of Melindi is damaged.”Footnote 19

Eventually, a form of system emerged, thanks in part to the Portuguese acquisition of a fort and trading post in Chaul in the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. In 1530, Chaul was declared to be the sole official port where the textile procurement for Sofala and Mozambique was to be carried out. In the middle decades of the sixteenth century, we thus see the emergence of the so-called navio do trato de Chaul, which could either be a single large vessel or several smaller ones, with a monopoly over the trade to Sofala. Together with Bassein, the hinterland of Chaul also became the most important area for the procurement of trade beads (contas) by the Portuguese for the African market. In turn, a large quantity of ivory was imported every year into Chaul and sold in the markets of the Deccan. What this implied then was a division of the Swahili coast trade, roughly north and south of Cabo Delgado. To the north, the Portuguese played what was at bottom a predatory role, with the real trade being carried out by Indian and local merchants, and the long-distance commerce remaining mostly in the hands of the Gujaratis. If in the initial years Malindi (and to a lesser extent Mombasa) dominated, as the century wore on, the port of Pate in the Lamu Archipelago (north of Mombasa) emerged as the great center for textile imports from India. The Portuguese acquisition and fortification of Mombasa in the 1590s eventually rendered these processes of hide-and-seek even more complicated. On the other hand, the restrictive and monopolistic policies of the Portuguese Estado ensured that in the southern areas over which they had greater control the direct links with the Deccan were greatly reinforced. In addition to the aforementioned trade with Chaul, the consolidation of Mozambique Island as a way-station on the Carreira da Índia ensured that its links with Goa grew ever more pronounced also through the so-called concessionary viagens de Moçambique, made, as an account from around 1580 put it, “in a ship fitted out at the cost of the royal treasury, in which they send supplies, and munitions, and Cambay cloth, and beads and other merchandise, which are sent on the King's account.”Footnote 20 This was important because once Goa became the capital of the Estado in 1530, its population of settlers (or casados) grew apace, and each settler household became a source of demand for slaves, many of whom were imported from Mozambique, Sofala, and adjacent regions. Unfortunately, most studies remain distressingly vague on the numbers involved in Goa until the latter half of the eighteenth century, far beyond the period under consideration here.Footnote 21 But we are aware that by the end of the sixteenth century there were probably several thousand slaves in Goa, of whom a large proportion came from eastern Africa. In turn, at least some of these either fled or may even have been sold into the neighboring Deccan Sultanates, Bijapur and Ahmadnagar.Footnote 22

Pedro Machado's long-term view of the trade between East Africa and India in his recent book draws in turn on Lobato's analysis, adding to it materials from the latter half of the eighteenth century. He points to the fact that “East Africa and Mozambique were not the largest export markets for Gujarati textiles in this period, the greatest number going to the Middle East,” and also stresses the importance of “the widespread African textile production that existed on the coast, islands and interior of East Africa.” Further, he argues that it was only in the course of the eighteenth century—thus beyond the chronological scope of the present essay—that a new “free trade regime” enabled Gujarati merchants to expand their exports to East Africa, so that “annual imports of Indian textiles stood at 300,000–500,000 pieces from the middle of the [eighteenth] century.”Footnote 23 It is clear from his discussion that it is imprudent to take such figures (which are already rough estimates for the eighteenth century) backward into the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Machado has suggested in another essay that already in the early sixteenth century, Gujarati textiles were to be found on the East African coast “in a vast array of styles, colours, and shapes,” and that the “bulk were transported into the interior where they were in great demand.” His broad conclusion, though relegated to a footnote, is significant for us: “Due to the limits of the evidence, it is difficult to determine precisely whether Gujarati textiles became more important in these centuries than they had been in earlier ones, or whether they are more noticeable because the documentation improves.”Footnote 24 At the same time, it is clear that there was a shift in terms of regional emphasis in textile procurement in India. From an initial focus on northern and northwestern Gujarat, the sixteenth century saw the growth in importance of the so-called panos de Balagate, produced in the Deccan hinterland of Chaul. In turn, the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw a return to northwestern Gujarat, as Diu emerged to the fore though the activities of its indigenous merchants (baneanes) in the East African trade.Footnote 25

FROM THE SWAHILI COAST TO ETHIOPIA

While commercial relations between the Deccan ports and the Swahili coast thus attained a certain importance over the course of the sixteenth century, relations with northeast Africa were in fact of far greater political significance. Again, the Portuguese had some role to play in the matter, but in a rather complicated way. By the last decades of the fifteenth century, as they prepared to enter the trade of the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese were anxious to find Christian allies in the region to aid them against the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. This led them to send envoys to the ruler Eskender (r. 1478–1494) of the Solomonid dynasty in Ethiopia, and to continue efforts to contact “Prester John” (as they termed these kings) in the early decades of the sixteenth century. Intermittent diplomatic relations followed during the regency of Queen Eleni (1507–1516), at a time when the Portuguese under Afonso de Albuquerque first penetrated the interior of the Red Sea and installed themselves in the island of Soqotra.Footnote 26 They persisted during the time of Lebnä Dengel (or Dawid II, r. 1507–1540), a period when the Ethiopian rulers gradually found themselves under menace from the coastal sultanate of Barr Sa‘d-ud-Din (sometimes loosely termed Adal), under its powerful and charismatic leader Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim.Footnote 27 Imam Ahmad, popularly known as “Grañ,” the left-handed, made an alliance with the Ottomans in the neighboring areas of the Red Sea, and was able, after initial campaigns in the late 1520s, to deal the Ethiopians a severe defeat in 1531. The Portuguese by this time were increasingly suspicious of the Christianity practiced in Ethiopia, which they suspected of being tainted with Judaism. Nevertheless, they felt constrained to intervene, partly to impede Ottoman advances into the area, and did so through an expeditionary force led by Cristóvão da Gama.Footnote 28 Even though Gama was eventually killed (or “martyred”) in the southern Tigray region in August 1542, the Ethiopians were thereafter able to gain the upper hand, as Imam Ahmad himself was defeated and killed by the forces of king Galawdewos (r. 1540–1559) at the battle of Wayna Daga in February 1543.

These campaigns between the 1520s and 1540s had a major impact on the market for military slaves in the Horn of Africa, and a spillover effect into the markets of the Hijaz, Yemen, and Hadramawt. It was precisely in these markets that African slaves were generally procured for Indo-Muslim states. The presence of such slaves—known as zanji or zangi (for those from the Swahili coast) and habashi (for those from the Horn of Africa)—is known from the time of the Delhi Sultanate and its offshoots, even if their precise numbers are impossible to know.Footnote 29 Drawing on the earlier, very rough estimates of Ralph Austen, Paul Lovejoy proposed in a classic work on slave trade that the Red Sea and Swahili coast each exported roughly a thousand slaves a year in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with the numbers increasing considerably only after 1700.Footnote 30 In turn, these estimates have been critically scrutinized by the French historian Thomas Vernet, who has observed that they are simply “not supported by the assessments given in contemporary documents.” Instead, he suggests that the “slave trade run by Swahili, Comorian, and Arab merchants, who provided themselves in Madagascar and the Cape Delgado and Juba areas, might have fluctuated between 3,000 to 6,000 slaves a year in the seventeenth century … [with] a low estimate of around 3,000 to 4,000.” As regards to their destinations, he states that the “Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf probably absorbed the majority of the captives, followed by the Swahili towns, and finally, the Portuguese settlements.”Footnote 31 Revised estimates for the trade across the Red Sea have, however, not been made to date. Recent works of a qualitative nature have nevertheless pointed to the steady participation of both Christian and Muslim actors in this slave trade, and that “one should cease to think of slave trade in the Horn of Africa as a phenomenon uniquely linked to Muslim merchants, but rather envisage it as a system in which Christians and Muslims participated with shared interests as well as real competition.”Footnote 32 That said, it can be argued that the trade also followed rhythms, and that there were certainly peaks and troughs exacerbated by conflict, with the decades from the 1520s to the 1540s representing a significant peak. It should also be stressed that, unlike the case of the Atlantic, historians of the western Indian Ocean are currently not positioned to speak with any clarity regarding the gender composition of the slave trade, though the proportion of women seems to have been far lower than in the Atlantic case.

While it is impossible to produce numerical estimates, African elite slaves were probably outnumbered in India for long periods by Turkic slaves originating from Central Asia, who dominated the mamluk (or ghulam) institution in Delhi in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.Footnote 33 Periodically, though, groups of habashis did emerge into prominence, as they did by briefly seizing direct power in the Bengal Sultanate in the late fifteenth century. It is no coincidence that this was in a period when the Bengal Sultans had opened direct relations with Mecca and were periodically sending envoys and funds there. A new dynasty was eventually founded by a Meccan Sayyid, who took the title of ‘Ala-ud-Din Husain Shah (r. 1494–1519). But even during his reign, if Tomé Pires may be believed, the habashis continued to have a major role: “The people who govern the kingdom [Bengal] are Abyssinians (Abixins). These are looked upon as knights (avidos por cavaleiros); they are greatly esteemed; they wait on the kings in their apartments. The chief among them are eunuchs and these come to be kings and great lords in the kingdom. Those who are not eunuchs are fighting men. After the king, it is to this people that the kingdom is obedient from fear.”Footnote 34

Elite slavery was also known in the fifteenth-century Bahmani Sultanate, as we see from reading the chronicles of the region, and habashis were particularly present in the palace interior. But the historiography abounds in vague generalizations and can give us only a limited number of concrete examples of their power. Relating events from the late 1480s, for example, the chronicler Sayyid ‘Ali Tabataba'i claims that “a clique of Habshis in the service of the Sultan [Mahmud Shah II] had the utmost confidence placed in them; and owing to the power they possessed in the affairs of government, used to behave in a very imperious manner.”Footnote 35 Names of some of these notables have come down to us, in particular a certain Dilawar Khan Habashi, a particular opponent of the Turkish group at the court led by Qasim Barid (who was later to found the Bidar Sultanate). Tabataba'i makes this rivalry one of his great themes to explain the collapse of the Bahmani state and the emergence of its successors. In another passage, we learn:

At this time the power and authority of the people of Habshah and Zangbar in the service of the Sultan had increased a thousand-fold, and the other State officials had no longer any power except in name. The whole country and the offices and political affairs of the kingdom and the government treasuries they divided among themselves, and arrogantly ignoring the sovereign, themselves governed the kingdom. But since the star of their good fortune had now reached its zenith, after continuing for a long time undiminished: as is invariably the rule with fortune as well as the revolving heavens—the star of that clique began to decline.

The key figure here is not Dilawar Khan (killed in a military accident involving an elephant), but another personage. Pires, writing in the 1510s (but referring to a past time), mentions a handful of great “lords” in the declining Bahmani polity and states: “Milic Dastur [Malik Dastur] is an Abyssinian slave of the king (abixi escpravo del Rey), and is almost as important as each of these. His land borders on the Narsinga [Vijayanagara] frontier, and he lives in Gulbarga where he has a garrison.”Footnote 36 Other Portuguese chroniclers refer to him as a eunuch (capado), and the Deccan chronicles identify him as Malik Dinar Dastur-i Mamalik, who was eventually killed around 1509–1510 on the orders of Yusuf ‘Adil Khan. Malik Dinar thus failed to do what several other notables of varying origins did, that is to lay the foundations of a regional state from the vestiges of the moribund Bahmani Sultanate.Footnote 37

The first third of the sixteenth century represents a relatively low point for the fortunes of Ethiopians in the Deccan, partly because this was a high point for Shi‘ism in the region and the Ethiopians were usually devout Sunni converts. To comprehend the upswing that their trajectory took thereafter, we need to return to the conflicts in the Horn of Africa, as well as political processes in neighboring Gujarat. One of the earliest scholars to pay attention to this question was the British Orientalist E. Denison Ross, while editing an Arabic chronicle written in Gujarat by a certain ‘Abdullah Hajji-ud-Dabir Ulughkhani.Footnote 38 Ross proposed that in spite of the presence of some prominent figures in the fifteenth century (such as one Sidi Bashir, who constructed a major mosque in Ahmedabad), the really major influx of habashis into Gujarat took place in the 1530s, and that this process accompanied the move of a certain number of Ottoman subjects from the Red Sea to Gujarat, particularly a group around the figure of Mustafa Bairam, titled Rumi Khan.Footnote 39 It is well known that these Ottomans (or rumis) played an important role in Gujarat politics from the time of Sultan Bahadur Shah (d. 1537) and extending into the following decades. Some of them, like Khwaja Safar Khudawand Khan, were instrumental in shoring up the significance of port cities such as Surat, which they fortified and rendered defensible against Portuguese attacks. However, the reader of the text of Ulughkhani, Zafar al-Walih, can also discern that the number of important habashis in the upper strata of the Gujarat Sultanate's administration grew apace at this time. Ross listed a number of these, such as: (1) several notables with the title of Jhujhar Khan, including Bilal Habashi and his son Marjan Sultani;Footnote 40 (2) at least two persons, Sandal and ‘Abdul Karim, father and son, with the title of Fulad Khan; (3) and Yaqut Habashi, titled Ulugh Khan (d. 965 H/1557), followed by his son Muhammad Ulugh Khan, who was the chief patron of the chronicler.Footnote 41 Ross further argued that many of these Ethiopians were purchased in the slave-markets of the Red Sea or acquired as tribute by the Ottomans from Imam Ahmad in the course of his campaigns in the late 1520s and early 1530s. Consequently, they often continued to show a considerable (though not complete) loyalty to the Rumis and their families in Gujarat politics, especially in the difficult decades of the 1550s and 1560s. This was particularly so in the reign of Sultan Ahmad in the late 1550s, when two significant factions faced off, led respectively by ‘Abdul Karim I‘timad Khan and ‘Imad-ul-Mulk Aslan Rumi. Among other significant habashi figures mentioned in the chronicles of the period are Yusuf Khan, Dilawar Khan, Bahram Khan, and Bijli Khan, all of whom seem to have participated in court politics as well as held significant appanages.

HABASHIS AND PORTUGUESE

Historians of the period have probably not paid adequate attention to an additional set of sources that shed considerable light on the role of the Ethiopians in India at this time, namely those in Portuguese.Footnote 42 For example, the chronicler Diogo do Couto (1542–1616), in his Décadas da Ásia, returns time and again to the place of some figures who are too insignificant, for whatever reason, to appear in the Perso-Arabic materials, even if he too remains focused on male figures with a military-commercial profile.Footnote 43 Couto is an intriguing figure who cannot easily be pigeonholed into the stereotype of the Catholic crusader-historian, and who took a certain pride in incorporating elements gathered from renegades and indigenous informants in his narratives.Footnote 44 Some of these were persons with whom the Portuguese Estado had extended dealings because they were in close proximity to places like Diu, where they had a fortress. We may take one case from the 1550s, that of a certain Habash Khan (or “Abiscan”), who appears several times in Couto's text. In his version, after the assassination of Sultan Mahmud in 1554, there was a move by several Gujarat notables to seize autonomous control of territories. Habash Khan thus took “the lands of Dio from the hills of Una to those of Junager and made his residence in the city of Novanager.”Footnote 45 He also appointed an agent by the name of Sidi Hilal to ensure that he received half the proceeds of the customs-house of Diu. This led to a series of skirmishes between the Sidi and the Portuguese, and if the Portuguese were initially successful in brutally raiding the Ethiopian settlement close to their fort, they eventually began to suffer significant losses. Alarmed by this, they sent a diplomatic message asking the powerbroker ‘Imad-ul-Mulk at court to intervene in their favor. As a consequence, Sidi Hilal was replaced by a certain Sidi Marjan, but Habash Khan retained broad control of the area. After a brief gap, he continued to raid the Portuguese at Diu, which led them to try another tactic. They corresponded with a certain Tatar Khan, a rival notable who had seized hold of Junagadh, and complained to him that Habash Khan was “a weak and false Abyssinian, possessing no merits (Abexim fraco, e falso, e sem merecimento algum).”Footnote 46 Tatar Khan was prevailed upon to march on the coastal lands and seize Porbandar, Mangrol, and other coastal sites. Caught between these attacks and the Portuguese, it is reported that Habash Khan was obliged to abandon the area and retire to the east. Refusing the demands of Tatar Khan and his agents to develop Ghogha as a center of maritime trade to the Red Sea, the Portuguese were able for a time to centralize shipping at Diu, which remained their customs-house and chief port in the area.

The Ethiopian elite in Gujarat is thus presented in the Portuguese view as a formidable and intractable group, determined to resist them where possible. After these events in Kathiawar, their next set of confrontations occurred a few years later, in the context of the frontier region of south Gujarat. Here, the Portuguese Estado was troubled by the rise and consolidation of the port of Surat, which had emerged as an important commercial center in the 1540s. Consequently, they attempted to obtain a foothold in the near vicinity and eventually managed to persuade first ‘Imad-ul-Mulk and then I‘timad Khan to cede to them the area of Daman, south of Surat. A group of Portuguese began to settle the area from late 1556, but the matter proved complicated, mainly because of the presence of a powerful set of Ethiopians in the area who were quite deeply entrenched.Footnote 47 Our main information again comes from Couto, who notes that chief figures who resisted were a certain Sidi Bu Fath (“Cide Bofatá”), assisted by Sidi Ra‘na (“Cide Rana”), as well as a Turk named Qarna Bey (“Carnabec”). This resistance was finally broken when the viceroy Dom Constantino de Bragança arrived in February 1559 with a large fleet and substantial reinforcements, so that Sidi Bu Fath was obliged to abandon his small fort at Daman and withdraw to the north, beyond the Kolak river and as far as Parnera and Valsad.Footnote 48 However, on the viceroy's return to Goa, the Sidis returned to the attack and a see-saw struggle followed over several months. First, the Portuguese mounted an attack on Valsad, and then the habashi cavalry swept down as far as Sanjan, Dahanu, and Tarapur, causing considerable destruction to those southern territories. However, despite their best efforts, they were unable to take Daman itself, where the captain Dom Diogo de Noronha managed to hold out. In a last throw of the dice, a new actor entered the scene: this was, in Couto's words, “an Abyssinian called Cide Meriam [Sidi Marjan], a man considered to be a great knight, and who had five hundred horses in his stables.” Gathering together a total force of some eight hundred horse and a thousand foot-soldiers (four hundred of whom were gunners), he descended on Daman from the north in October 1559. On this occasion, the Portuguese decided not to wait in their fort, but instead sent out a force to meet him, hoping for a combat in the “fields of Parnel [Parnera].” Couto's account of the combat is initially somewhat romantic.Footnote 49 Two cavaliers, Marjan and the Portuguese Garcia Rodrigues de Távora, after an exaggeratedly courteous exchange of letters, apparently met on horseback in single combat and charged at each other lance in hand. They then fell to the ground in a mêlée, surrounded by others. At this point, things took a different turn, as an anonymous Portuguese soldier pierced Marjan through with a lance, killing him on the spot.Footnote 50 What Couto does not mention (though Jesuit sources from the 1580s do) is that his body was then carried back by his men to Surat, where it was buried with honor in the mausoleum of Khwaja Safar Khudawand Khan. By the mid-1570s, the Sidi had acquired the posthumous reputation of a protector of mariners and a performer of miracles, and Hajji-ud-Dabir reports that when he visited his tomb in 1575, crowds gathered there on Fridays. In his brief account, he notes that Marjan had come from Bharuch to Daman to conduct a holy war (fi al-jihad) against the Portuguese, and that on his death he was therefore remembered as “the holy warrior and martyr (al-mujahid al-shahid)” Marjan.Footnote 51

The end of Sidi Bu Fath's regime at Daman arguably had more significant consequences for the habashis of western India than has generally been realized. If Couto may be believed, there were “three thousand Abyssinians” in the settlement in 1559, and Bu Fath may have taken some two thousand with him when he fled. It is of some interest that the Portuguese chronicler does admit that the Estado came to terms with some of those who remained: “Because there were few Portuguese here who wished to accept villages [in grants], the viceroy granted them to Abyssinians [who had become] Christians, so that they might remain here, with the obligation of maintaining firearms (espingardas).”Footnote 52 This was a process known as aforamento, which the Portuguese had already followed in the 1530s in other nearby territories such as Bassein; the grantees (foreiros) received villages, and collected revenue, in exchange for rendering some basic military services. A later fiscal document from 1592, the so-called Tombo de Damão, gives us an indication of some of the most significant grantees and their locations (see Table 1 and Figure 2).Footnote 53 A few may be found in the central parganas of Moti Daman, and Nani Daman, but most are located in the outlying areas of Lavachha, Sanjan, and Tarapur, bordering on the lands of the so-called “rei de Sarzetas,” the Koli Raja of Jawhar. But it is obvious that a much larger exodus took place southward into the Deccan. This was also because the 1560s and 1570s would prove relatively unwelcoming for the habashis in Gujarat. The Mughal conquest of the region in 1572–1573 in reality left little place for this group in the political system, in comparison to the preceding fifty years. As we know, the Mughal mansabdari system, though it might have been accommodating to a variety of groups, never could find a real place for the habashis (with rare exceptions such as Sidi Miftah Habash Khan, commander of Udgir).Footnote 54

Table 1. Ethiopian-Origin Foreiros in the Daman Region, 1560–1590

Source: Artur Teodoro de Matos et al. eds., O Tombo de Damão, 1592 (Lisbon: CNCDP, 2001).

Figure 2. Daman and its environs (prepared by Bill Nelson).

Figure 3. Mosque of Sidi Bashir in Ahmedabad (photo by Cemal Kafadar).

But this was certainly not true for the Sultanates of the Deccan, in particular Ahmadnagar and Bijapur, and to a lesser extent Golconda. During the second half of the sixteenth century, there was a great deal of promiscuity between these courts owing not only to frequent intermarriages among the royal houses, but also because notables (or amirs) regularly switched loyalties between them. In the last third of the century, in the late 1560s and 1570s, the growing shadow of the habashis is first discernible in Ahmadnagar, during the reign of Murtaza Nizam Shah, as they intervened in a number of key struggles. In the first of these, they helped Murtaza against his mother and the former regent, Khunza Humayun, who was determined to keep control of power; she was arrested and sequestered in Shivneri fort (near Junnar).Footnote 55 Not long thereafter, in 1570, the Sultan launched an attack on the Portuguese at Chaul, which resulted in an extended siege that failed to attain its purpose. Contemporary Portuguese sources report the arrival on Saturday, 15 December 1570, of the Ahmadnagar general Farhad Khan with “eight thousand horse, and many foot soldiers, and twenty elephants.” They further add: “Faratecão [Farhad Khan] was an Abyssinian captain, of great reputation, who greatly liked the Portuguese from the time of that great second siege that the Moors laid on Diu when Dom João Mascarenhas was captain, when this Abyssinian was in the service of the king of Cambay.” In other words, he had already been in Gujarat in the mid-1540s and possessed long experience of dealings with the Estado da Índia.Footnote 56 Others involved in the siege operations included another habashi commander, Ikhlas Khan (“Agalascão”), described as “a very important person in the kingdom and captain-general of the field.”Footnote 57 While this siege failed, when the Ahmadnagar armies came back to attack Portuguese Chaul again in the mid-1590s they were led by Fahim Khan (apparently a eunuch of Bengali origin) and the Ethiopian Farhad Khan, probably the same personage from the 1570s. According to the Portuguese chronicles, Farhad Khan fought desperately on this occasion, but was eventually wounded and captured along with his wife and daughter. If we are prepared to follow the account by Couto, before Farhad Khan died of his wounds he converted to Christianity and was buried with ceremony in Chaul; his wife produced a sizeable ransom and left for Ahmadnagar, while the daughter also converted and was taken off to Lisbon.Footnote 58

While the Ethiopian group had emerged by 1570 in a position of prominence in Ahmadnagar, in turn the murder of ‘Ali ‘Adil Shah in 1579 opened up the possibility for them of profound changes in Bijapur. In the 1580s, the éminence grise who emerged was Dilawar Khan Habashi, together with two other Ethiopians, Ikhlas Khan and Hamid Khan. The early years of the reign of Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah in Bijapur thus witnessed a turn toward a moderate form of Sunni Islam (unlike the Twelver Shi‘ism favored by his uncle), and a gradual reconfiguration of courtly style, which was defined in a mature version toward the end of the century. Yet despite his early tutelage by Dilawar Khan, Ibrahim proved too wily a bird to be dominated by any single group, and in time he even promoted Maharashtrian Brahmin ministers when they suited him better. On the other hand, by the end of the 1580s, the habashis were prepared to consolidate power in Ahmadnagar, apparently through a tactical alliance with the Dakanis against the long-dominant Iranian migrants. A period of considerable turmoil ensued, as various rulers were displaced and assassinated from the late 1580s onward and scores were settled between political factions through bloodletting on the streets of the Sultanate's capital. A number of habashis stand out in this context: Yaqut Khan, ‘Ambar Khan, Shamshir Khan, Ankas Khan, Bulbul Khan, Habash Khan, and Abhang Khan (as well as the near-ubiquitous Farhad Khan), as well as the main figure, the millenarian sectarian leader Jamal Khan (d. 1591), whom the Persian chroniclers regarded as bearing a great deal of responsibility for the turmoil. Adding to these problems, and in some versions even the root cause of them, was the growing pressure of Mughal expansion from the north. It appears that by the end of the 1590s the Mughals were expecting their superior armies to advance easily beyond the river Narmada and handily defeat the weakened Ahmadnagar state, as they had done in the Rajasthan, Bengal, Sind, and elsewhere.

THE RISE OF THE MALIKS

In the event, matters proved far more complicated. It took more than three decades for Ahmadnagar to submit, and the other two major Deccan Sultanates persevered until the late 1680s. There were several causes for this delay, if one wishes to see it in that way, including the diplomatic acumen of some of the Deccan Sultans. But a key one was the emergence of a powerful habashi elite in the Deccan, which built up clever regional alliances and offered substantial military resistance. As late as 1609, Philip III was writing to his viceroy in Goa with the view that opposing the Mughal armies was a hopeless task. He recalled that the earlier governor “had written to me of [the state] in which the conquest of the Deccan was, with gave great reason for trepidation, because though the Mogor [Mughal] claimed to be our friend and had again sent an ambassador who was in waiting, he had heard that he [Jahangir] did not have good intentions with regard to his affairs; and because of the state in which even the walls of my fortresses in the North [Province] were, there was nothing to stop him except some resistance from the Idalcão [‘Adil Khan], who had sent ambassadors to the Malik, and to the Cotta Maluco [Qutb-ul-Mulk], king of Masulupatão, and Avancatapanaique [Venkatappa Nayaka of Ikkeri], to all get together.”Footnote 59 In reality, even if Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah did apply himself to diplomacy (mixed with generous bribes to Mughal frontier-commanders), the real obstacle was in Ahmadnagar. In 1600, the Mughals had taken the capital city of the Sultanate, after some years of resistance mounted by Chand Sultana, regent and sister of a former ruler. But her own power had resided, as an earlier Portuguese viceroy had remarked, in an alliance with a protégé of the deceased Jamal Khan, namely Abhang Khan. This powerful figure—referred to both as Habashi and Zangi in the records—based himself in the fortified center of Junnar, west of Ahmadnagar, and this in turn became the initial base of one of those in his entourage who emerged in a position of prominence: ‘Ambar Jiu or Malik ‘Ambar.

Much has been written about this figure, and a great deal of it is either open speculation or generous exaggeration.Footnote 60 Richard Eaton's short study of ‘Ambar remains one of the most useful in recent times, and carefully sifts plausible versions of his history from less plausible ones.Footnote 61 It would seem that ‘Ambar was born with the name of “Chapu” in the Horn of Africa around 1548, then sold in the slave-market of Mokha, before being owned for a time in Baghdad by a certain Khwaja Mir Qasim. From Iraq, he was then sold to an important Ahmadnagar amir Khwaja Mirak Dabir, titled Chingiz Khan, who was wakil and peshwa of the kingdom in the early 1570s.Footnote 62 After his master's death in 1574 or 1575, he was apparently manumitted and spent some time without fixed employment. At any rate, a good decade and a half later, in the early 1590s, he appears to have spent time at the frontier fortress of Kandhar (40 kilometers southwest of Nanded) in order to secure it for Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah (perhaps during the rebellion of his brother Isma‘il). He even constructed a bastion (the burj-i ‘Ambar) and left two inscriptions there.Footnote 63 This seems to have been a custom of his, for other inscriptions bearing his name can be found at Antur fort and in the Shivneri Hills, the latter one still referring to him, interestingly enough, as “Chingizkhani.”Footnote 64 After his time in Kandhar, Malik ‘Ambar returned to Ahmadnagar service and joined Abhang Khan Habashi, rising quickly to command 150 horsemen. After the fall of Ahmadnagar in 1600, he seems to have hesitated in terms of his loyalties and considered offering his services to the Mughals. The account of the Mughal envoy Asad Beg Qazwini, present several times in the region in the early seventeenth century, gives us a good number of details, and suggests that on at least two occasions the subject of winning ‘Ambar over had been discussed in high Mughal circles, such as with ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i Khanan. Of particular interest is Asad Beg's highly positive portrayal of the Ethiopian: not only was he “the bravest of the men of the time,” but he was apparently exemplary both in his courtesy and piety, giving large sums in alms and ensuring that in his camp, on every Friday evening, twelve thousand recitations of the Qur'an were carried out by ‘ulama of caliber.Footnote 65 The chronicler Firishta, also a contemporary, describes his rise as follows.

After the return of Akbar Padshah from Burhanpur to Agra [April 1601], two persons of the late Nizam Shahi government distinguished themselves by their enterprise and conduct and, in spite of the Mughal forces, down to the present period, have retained almost the whole of the Nizam Shahi dominions. The one, Malik ‘Ambar Habashi, possesses the country from the borders of Tilang to within one farsakh of the fortress of Bir, and four karohs of Ahmadnagar, and from twenty karohs west of Daulatabad to within the same distance of the port of Chaul. The latter, known as Raju, possesses lands from Daulatabad as far north as the Gujarat frontier and south to within six kos of Ahmadnagar: both officers from necessity profess the semblance of allegiance to Murtaza Nizam Shah the second.Footnote 66

In the following years, ‘Ambar first defeated Miyan Raju, and then expelled the Mughals from Ahmadnagar. In 1610, he moved his capital from Junnar to the prestigious center of Daulatabad and began the process of reorganizing the land cadasters of the region in an effort to rationalize the revenue administration. Further, he showed a distinct interest in maritime affairs, as we see from his repeated dealings with the Portuguese in Chaul, as well as with Danda Rajapuri, slightly to the south. Later, in the 1610s and 1620s, we find references to ships owned by him and his associates plying the routes to the Red Sea and the Hadramawt. English Company records inform us that the master of their ship, the Andrew, reported in September 1621 the seizure of “a juncke of the Mellick Ambers, which he had taken coming from the Red Sea, upon consideration of wrongs which hee had donne unto our marchants in Mogulls country by robing their caffely in coming downe from Agra.”Footnote 67 This retaliation for an attack on a caravan in central India carrying English goods (for which they incorrectly accused ‘Ambar) became the occasion for a drawn-out dispute. The English even sent a representative, Robert Jeffries, to Daulatabad, but he was unable to make much headway.Footnote 68 Nevertheless, these dealings in the first half of the 1620s showed that Malik ‘Ambar was active as a maritime trader from Chaul and nearby ports, using as his agents other Ethiopians, such as Sidi Sarur, nakhuda (or master) of his captured ship. He also appears to have used these ships to the Red Sea to carry “rice for the poore [pilgrims], which hee yearly sendes,” a confirmation of his reputation for alms-giving (sadaqa).Footnote 69

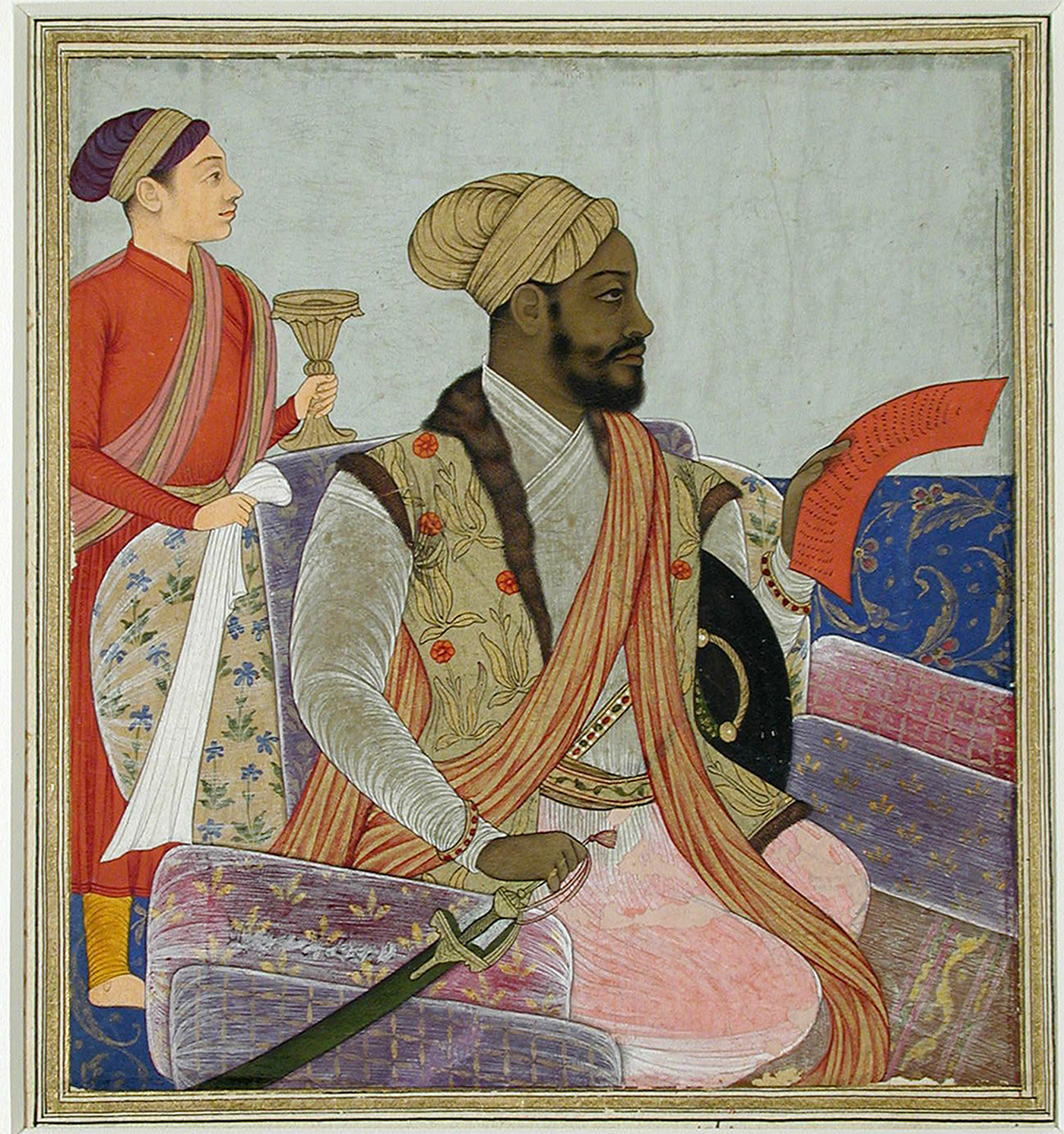

Unlike the case of late fifteenth-century Bengal, Malik ‘Ambar did not choose to directly seize sovereign power, and instead reserved for himself the more modest title of peshwa. After his death in May 1626, his son Fath Khan, as well as a number of other Ethiopians, continued to play a significant political role in Ahmadnagar, and thereafter in Bijapur. An analysis of the Bijapur elite (or umara) in the middle decades of the seventeenth century continues to show a sizeable place for these men, some of whom even emerged as important literary and cultural figures in the Dakani language, such as a certain Malik Khushnud (fl. 1630–1645), author of the important versified work Jannat Singar.Footnote 70 They also play an important role in the southward campaigns that took the Bijapur Sultanate in the direction of the conquest of a good part of the Kannada and Tamil country in the 1640s and 1650s. Those involved in the southward push included Sidi Raihan, first titled Ikhlas Khan, and then Khan-i-Khanan (d. 1657), who was a prominent commander (Figure 4); Randaula Khan, titled Rustam-i-Zaman, who controlled parts of the Konkan and the port of Rajapuri; and other prominent figures including Sidi Jauhar of Karnul and his son-in-law Sidi Mas‘ud.Footnote 71 In the course of the seventeenth century, a group of Ethiopians also gradually took control of Janjira, a fortified island off Rajapuri (south of Chaul) and made it the center of their activities as purveyors of maritime protection and violence. After the fall of Ahmadnagar in 1636 they gained more autonomy, and in the 1660s they entered into open conflict with the expanding Maratha state of Shivaji for control of the Konkan and its trade. The Marathas mounted repeated attacks on Janjira in 1669–1670 and 1675–1676, and carried out others later; the Sidis for their part were driven to seek an alliance with the Mughals and managed eventually to survive the Maratha onslaught.Footnote 72 We cannot be certain of the migratory paths taken by most of these individuals and families since they are less well-documented than is Malik ‘Ambar. Unlike him, some of them may have belonged to a second or third generation, with roots going back perhaps to an earlier moment in Kathiawar or Daman.

Figure 4. Ikhlas Khan with a Petition, The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.442.

Figure 5. Inscription by Malik ‘Ambar at Antur Fort (author's photo).

CONCLUSION

This essay has focused on certain aspects of human and commercial mobility across the western Indian Ocean, notably between the African East Coast and western India in the early modern period. As noted at the outset, this is a less-studied theme than the relatively robust and historically continuous maritime commercial link between the Persian Gulf and India, a link made even stronger with the establishment in the Deccan of the Bahmanis and their successors.Footnote 73 On the other hand, relations between the Deccan and eastern Africa were probably indirect in the medieval centuries and they were only rendered more stable and direct in the sixteenth century, with the emergence of direct contacts between Chaul and Goa, on the one hand, and ports such as Sofala, Mozambique, and Mombasa, on the other. The migratory movements involved are also contrasting. Though some military slaves certainly made their way from Iran via the Persian Gulf ports to the Deccan, most movement was by free individuals. These were mostly male, but there were some women, even if their individual movements and careers are far harder to follow and track down. Further, there was also a real process of circulation, for these Persians often retained contact with their watan (homeland) and even returned there on occasion.Footnote 74 In contrast, the vast majority of Africans (usually from the Horn of Africa) found their way as slaves to the Deccan, and western India more generally. The names that they had in India often reflect this fact and referred to precious or semi-precious stones and objects—Marjan (coral), Yaqut (ruby), ‘Ambar (ambergris), or Sandal (sandalwood)—or were terms of loyalty or ethnicity; most did not carry the names they would have had in eastern Africa. We also have little or no evidence of their maintaining contacts or correspondence with their places of origin, as we do for some of the prominent Ottoman kul-slaves, for instance.Footnote 75

Nonetheless, some memories remained or were maintained in place. The most intriguing instance of this comes from ‘Abdullah Hajji-ud-Dabir Ulughkhani, who, as we have seen, served not one but two habashi masters. Among the textual sources he uses and cites are some from India (and Gujarat), but there is one that stands out. This is the Arabic chronicle of Shihab-ud-Din Ahmad ‘Arab Faqih, Futuh al-Habasha (or Tuhfat al-Zaman). Written in the Red Sea region early in the second half of the sixteenth century (its author originally came from the port of Jizan), this text was meant to exhort the Muslims of the region to return to their combat against the Ethiopian Christians, and as such it was intended at the same time to recall the life and circumstances of the now-deceased hero Imam Ahmad. It is clear that Hajji-ud-Dabir possessed a manuscript of this text, for he paraphrases long passages from it in order to provide some context to the many habashi notables who people his own history.Footnote 76 Further, it is obvious that he had spoken with at least some of them, for he adds details that do not appear to come from the text of ‘Arab Faqih. In sum, most of the habashis of Gujarat and the Deccan in the early modern period looked back not to a Christian past in the Horn of Africa, but to a history that located them squarely in the struggle to establish a place for Islam in the western Indian Ocean.

Can we advance our understanding of this particular set of histories by placing it in a larger comparative context, either that of the Atlantic or of the Mediterranean? One comparison that is frequently made is in quantitative terms, by measuring the African slave trade eastward in the Indian Ocean in relation to that westward into the Atlantic. The fact is, however, that not only are the statistics for the Indian Ocean far less reliable than those for the Atlantic, but comparing the two trades in such terms is problematic in other ways. Slaves were transported across the early modern Atlantic essentially in a context of plantation slavery, or on some occasions as household slaves in an urban context. With relatively few exceptions, such as the Mascarene Islands (Mauritius and Réunion), plantation slavery was not the norm in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 77 Furthermore, the possibility of crossing the waters to be integrated as an elite slave into a distant political system was a real possibility in the western Indian Ocean until 1750, whereas for Africans headed westwards it was unrealistic to expect such an outcome in Portuguese Brazil, Spanish America, or Anglo-America (even if former slaves could sometimes enjoy considerable economic success).Footnote 78 The habashis of Gujarat and the Deccan could thus, at least in some conspicuous instances, become powerful agents and political actors, rather than subaltern performers in a history dominated by other groups. Of course, this does not mean that it is not useful or interesting to compare individual trajectories, or microhistories, across the two oceanic spaces. This is precisely what historians of Islam in Brazil or colonial America have in particular helped us to do in recent times.Footnote 79 At the same time, extending the comparison to the relatively minor—but nevertheless significant—phenomenon of African slavery in a space such as the early modern Ottoman Empire helps us nuance the contrast between the Indian Ocean and Atlantic spaces. The crucial post of the habashi “chief eunuch” in the Ottoman court gives us access to a series of fascinating figures, ranging from Mehmed Agha (d. 1590) in the high Ottoman period, to Beshir Agha (d. 1746), a century and a half later.Footnote 80 While they became powerful political intermediaries, and thus at some remove from the African-Americans of the colonial era, these figures were usually unable to be more than powerbrokers and thus were more limited and circumscribed in their scope and ambitions than their South Asian counterparts. Further comparison could help us to better comprehend the specificity of these politico-social regimes, as well as their trajectories over time.