They struck Levi as splendid beings, from quite another planet than the one he had been in only five minutes ago – spring-footed, athletic, carelessly loud, coal-black, laughing, immune to the frowns of Bostonian ladies passing with their stupid little dogs. Brothers.Footnote 1

The most recent novel from highly acclaimed black British writer Zadie Smith is set in an East Coast college town. The story is (mostly) about a year in the troubled marriage of a white British art history professor, Howard Belsey, his African American wife, Kiki, and their three biracial children. However, Smith also focusses on issues of racial and ethnic identity, American institutions and ideology, cultural conflict and inequality which are all rendered visible through the invention of a fictional place named “Wellington.” Held up against similar locations in the region, nothing much distinguishes the liberal-arts college or the suburbanites who reside in town. They are college-educated professionals, they earn median family incomes higher than most Americans, and they are mostly white. But the author does not offer readers the “placelessness” of a standardized American landscape.Footnote 2 The large population of Haitian immigrants in the neighboring urban center, who work as janitors on the campus and as “cleaners” to the college faculty, lets us know that Wellington was not created with just any of the “Little Three” New England colleges (Amherst, Williams and Wesleyan) in mind. Zadie Smith is imagining Boston.Footnote 3

Smith's engagement with a broad range of themes and eclectic writing style make it difficult for scholars to categorize her novels.Footnote 4On Beauty has been described as academic satire, as an homage to E. M. Forster, as postcolonial Caribbean writing, and as a follow-up to Zora Neale Hurston's Tell My Horse.Footnote 5 But the novel is most important here as a Boston book. Several reviewers identify the city as the character that really nails things in place.Footnote 6 They point out how it anchors the imagination of readers, as it does in her previous work about race relations and multicultural Britain. I build on their observations to show how the city functions, in the words of Percy Lubbock, as a “presence and an influence that counts throughout – and counts particularly in a matter that is essential to the book's effect, a matter that could scarcely be provided for in any other way.”Footnote 7 While I do not wish to suggest that Smith's aim was to represent, with any accuracy, the material realities of Boston, this essay considers the ways Wellington reflects Smith's urge to make meaning out of the spaces, social relations and narratives that define the city. Joan Acocella considers the project a success because the episodes that unfold in the Belsey household achieve what the realistic novel is intended to do – hold up a mirror to its time.Footnote 8 I aim to show that the social commentary of On Beauty functions specifically through the enactment of place and the sense that what is meaningful in social life occurs in and through place.

Peter Preston (2007) characterizes Smith's use of thick description as “incidental detail” that may be engaging on a local level but whose relation to the book's overall concerns is either unclear or too studied.Footnote 9 However, I argue that her attention to locality – how Wellington is constructed as a place – is worth considering more carefully. The novel is almost ethnographic in the development of the characters and in its attention to their speech, and the text parallels a phenomenological perspective of place in its rigorous description of Wellington “as it is lived and reflected upon in all of its first-person concreteness, urgency, and ambiguity.”Footnote 10 Several passages seem transcribed, rather than written. Smith borrows rap lyrics from her brother “Doc Brown,” rehearses lectures on Rembrandt paintings, and depicts phonetically the “strange squelch of vowels” (“eyeano”) that is the Belsey children's stock response to all of their parent's queries (88). Whether or not the story calls for this much texture, a close reading suggests that Smith's characters need place.

The creation of a credible Wellington is what renders the social reality of her subjects in all its complexity. For Levi Belsey, the sense of where black folk belong – not what they look like – determines his identification or estrangement; it influences his cognitive map of Wellington and directs his behavior throughout the novel. He adopts a Brooklyn accent, feigns residence in Roxbury, and romanticizes the “street.” Place also reaffirms the moral order of Wellington. The novel revolves around the tension between us here in Wellington and them out there and what happens when those different worlds try to connect. Smith paints a colorful (sometimes mocking) picture of the world of the Wellington campus, liberal in principle but largely removed from the actual social conditions outside its walls. Even James Woods, who describes the writing in White Teeth as “hysterical realism,” maintains that “her details are often instantly convincing, both funny and moving. They justify themselves.”Footnote 11

What, then, do we miss if we see the details of the local context as incidental in the realist novel? Philosophers Edward Casey and Robert Mugerauer conclude that, even in spite of our mobile, continually changing postmodern era, being-in-place remains a necessity for people because having a place is an integral part of who and what we are as human beings.Footnote 12 And in this case it is not race but place (finding a place, feeling out of place, knowing one's place) that helps us understand many of the dilemmas On Beauty's black characters face. As New Yorker critic Joan Acocella argues,

The novelist, like a scientist, sets up special conditions. What if we fed these mice only cupcakes? What if we married this traditional Southern black woman to a white British intellectual? That way we can get information about glucose metabolism, information about race, that wouldn't come clear under random circumstances.Footnote 13

Location, the where of the story, is one of the “special conditions” Acocella's scientists and novelists set up. A laboratory, like a city, a university or a house, is a place.Footnote 14 And each is, according to geographer Edward Relph, a territory of significance, distinguished from other areas by its name, its particular qualities, the stories and shared memories connected to it, and by the intensity of meanings people give to or derive from it.Footnote 15 While the lab gives a scientist near total control over the objects of analysis, a city, on the other hand, has a pre-existing reality that a novelist either creates or exploits. I argue here that Zadie Smith does the latter. The choice of New England as a setting, together with geographical imagery, is used to reveal aspects of American race relations that “wouldn't come clear under random circumstances.” From this perspective, it is significant that Smith chose Greater Boston as the site of her first American race novel, and even more so that Haitians are so central to her effort to write a sense of the city into On Beauty.

In what follows, I focus on the presence of Haitian immigrants throughout the text. However, I move beyond critics' observations that “Smith's predilection for scholarly reference tak[es] precedence over believable representations of her characters.”Footnote 16 Indeed, Haitian immigrants appear in On Beauty – as maids, waiters, vendors, cab drivers and, later, discontented strikers – as if transplanted directly from the pages of major American newspaper coverage of so-called “boat people” fleeing the dire poverty of Haiti. Yet even her most clichéd Haitian characters should not be read as casual insertions whose sole function is to introduce dramatic irony. More than any of the local details, Haitians authenticate Smith's imagined geography. They help establish both the (historical) time and place (or context) of her novel, which are, as Eudora Welty argues, “the two bases of reference upon which the novel, in seeking to come to grips with human experience, must depend for its validity.”Footnote 17

Further, as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that Haitians do more than give Smith's Wellington a distinct and recognizable identity. They tell the story of American race relations. Through the Haitian characters and dimensions of everyday life in Wellington, On Beauty illuminates important social realities of contemporary urban living, such as enduring inequality, complex black diasporan relations, and the ironies of America's much-celebrated post-civil rights movement/post-11 September/post-racial society. I will discuss each of these in turn below. Notwithstanding the critique that Smith's fictional Haitians do not seem fully imagined, I conclude that it is precisely the complex, partial and open-ended nature of literary representation that challenges social scientists to see all social phenomena as, to use Arjun Appadurai's term, “emplaced” – or constituted in part through location and material form and their multiple imaginings.Footnote 18 In this way, fiction can be a powerful analytical tool, not to unquestioningly reinforce naturalized notions of place, but to reveal beliefs and values and bring them into tension with countercurrents and American subcultures.

Theoretically, this article is informed by humanistic geographer Edward Relph's ideas in Place and Placelessness. Relph's work is a meditation on the importance of place in ordinary human life. He argued that place was a fundamental aspect of people's existence in the world. Places, he wrote, “are fusions of human and natural order and are the significant centers of our immediate experiences of the world.”Footnote 19 My interest in the importance of place and locality in the novel is grounded equally in the many examples, in this work and others, of Smith's efforts to understand worlds beyond her own. Phenomenologists of place suggest that an individual's strong relationship (be it love/loathing, attachment/alienation or enchantment/antipathy) with a particular place will drive her to look for parallels in other places.Footnote 20 Therefore when Smith turns the Haitian maids – or housekeepers, as they might be referred to in American English – into “cleaners,” the more common reference in British English, she reveals her status as an outsider, which fuels both her ability and her need to make sense of an American racialized space.

PLACE MATTERS

On Beauty includes the standard publisher's note: “This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.” But critics and commentators have not resisted the urge to speculate about which New England college and town Wellington stands in for. A book reviewer for the Boston Globe acknowledges that both Cambridge and Wellesley are referenced in the novel:

The American portion of On Beauty takes place in a college burb a half-hour away from Boston by train, a toy town called Wellington, full of pomp and mock Tudors and Victorians, that resembles Wellesley in name and ambiance but whose wider arc has shades as well of Cambridge.Footnote 21

Smith's Wellington could also be modeled on Medford, MA, a city of about fifty-four thousand residents, less than ten miles northwest of Boston. Given the metropolitan area's tight municipal boundaries, Cambridge can appear to flow into Medford. The Belsey home at 83 Langham Drive – “large, lovely and within spitting distance of a half-decent American University” (17) – would fit in seamlessly in the affluent neighborhood of West Medford, making the college itself Tufts University. According to available Census data, Medford is 86·5 percent white, with a median family income of $79,476; moreover, 39 percent of the population has a bachelor's degree or higher (16 percent have graduate or professional degrees).Footnote 22

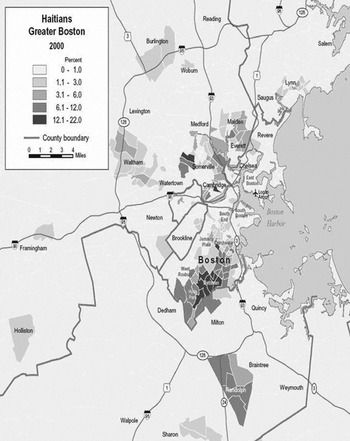

Importantly, Medford is also one of several Boston-area cities and towns where Haitians account for over one-third of the black residents. The Greater Boston area is a significant site in the geography of the Haitian diaspora and it has been home to the third-largest community of Haitians in the United States since the 1980s.Footnote 23 Like other blacks, they are concentrated in the city of Boston (where almost half the Haitians in the state of Massachusetts reside), with growing numbers settling in places like Smith's Wellington. Haitians make up 34·3 percent of the total black population in Medford and 45·6 percent in Somerville (see Figure 1).Footnote 24

Figure 1. Haitians in Greater Boston, 2000. Source: US Census Bureau, Census 2000 (Allen & Turner, 2004).

While this essay maintains that delivering a sense of place is central to the success of the novel, I do not wish to suggest that Wellington/Boston is unique. After all, Boston is not the only American city where a sizable community of Haitians has taken root and Smith borrows locals from other urban sites. Rather, it is the phenomenon of an increasingly multicultural place that is most important here. Boston is, for the first time in its history, a “majority–minority” city. As a result of post-World War II immigration, Asians, Latinos and blacks constitute over 50 percent of its population. What this new diversity means for the city's identity – and the identity of nearby suburbs that remain predominantly white – animates Smith's Wellington and the experiences of the novel's central characters. Henry Yu describes the history of the region as both distinct and distinctly American:

In the Northeast, a region dominated by large-scale European migration, the demonization of blacks helped mold together a diverse array of European migrants through the promised benefits of white supremacy. This was despite the fact that migrant flows of African Americans northward were relatively small until the twentieth century, but antiblack practices served a different purpose than in slaveholding regions in the Southeast.Footnote 25

Though Smith cleverly conveys this historical significance, setting Wellington apart from other recognizable sites in the American urban imaginary, Jacqueline Nassy Brown's comments about the materiality of place in Liverpool might well be remembered here:

The materiality of a place lies not merely in its physical, visible form (and visibility itself is a moving target) but in its identity as, for example, a seaport, or as the original site of Black settlement, or as a site hospitable or hostile to capital investment, or as one of Britain's problem cities. In similarly discursive terms, place's materiality is produced through enactments of the very premise – implicit though it might be – that place matters.Footnote 26

Place matters have always been important to this author. Zadie Smith experienced meteoric rise to the literary world's unique form of stardom after the publication of White Teeth (Penguin, 2000). On Beauty is her third novel, following the 2002 publication of Autograph Man.Footnote 27 In 2002 she was awarded a residential fellowship from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University to work on a book of essays called The Morality of the Novel. While in residence, she produced instead several short stories and very likely began conceptualizing her next novel. Smith credits her stay in the area as inspiring On Beauty: “Being in Massachusetts was like a sensory overload. It was absolutely phenomenal. I spent a lot of time walking around, and I think that turns up in the book – the streets, the colors.”Footnote 28 Whereas place for some is mostly a lived background, Smith attends closely to the character of the places she encounters. Take her review of David Fincher's film The Social Network (2010) as an example. She not only recalls the time she spent in New England, but also drops countless insider references – ranging from actress Natalie Portman's presence at Harvard to exhibits at the Harvard Museum of Natural History – that establish her role as a participant observer:

I can say (like everyone else on Harvard's campus in the fall of 2003) that “I was there” at Facebook's inception, and remember Facemash and the fuss it caused; also that tiny, exquisite movie star trailed by fan-boys through the snow wherever she went, and the awful snow itself, turning your toes gray, destroying your spirit, bringing a bloodless end to a squirrel on my block: frozen, inanimate, perfect – like the Blaschka glass flowers.Footnote 29

Smith has been faulted for this kind of signifying and the overabundance of popular-culture allusions in her work. But her success in visually setting the scene for the novel is a product of her “time walking around” and “being there” becomes an essential part of claiming authority.Footnote 30

THE WHERE OF THE NOVEL

On Beauty presents a bricolage of Boston place-markers and an array of Boston types populates the story. Wellington is located in a region where authentic American whiteness is imagined to reside.Footnote 31 There are numerous descriptions of Wellington in terms of traditionalism and race. On the one hand, Smith seems to align the whiteness of Wellington with its idyllic appeal – prosperity, serenity and beauty dwell there. At the same time, she draws attention to broader practices and dynamics of racialization and inequality in a region of America that perhaps best mirrors the challenges that grow out of its migration history.

The very house in which the Belseys live, for example, mimics the racial situation in a newly diverse city located in a predominantly white state and a predominantly white region of the country. As Fischer notes,

The house takes on larger proportions, symbolic of racial relations in the United States and emblematic of who “belongs.” … Levi receives hostile stares from white passers-by as he approaches his own house, and Howard fails to understand his [son's] experience as a young black man in America … The house seems oddly devoid of colour, suggesting an inability to see beyond the binary of black and white.Footnote 32

At key moments in the narrative, however, Smith reminds readers that a diverse black community is also part of this landscape. In addition to southern mammies,Footnote 33 there are black Brahmins, biracial middlemen, conservative West Indian intellectuals, ghetto blacks and West African traders. Notably, Haitian immigrants appear throughout the text much like the ones who serve meals in student dining halls and the ever-exclusive Harvard Faculty Club; who paint the college dormitory rooms in the summer; and who mop the floors of Boston hospitals, nursing homes and other institutions.

It is clear after reading less than fifty pages that Smith's Haitians gird the lifestyle of Wellington for both newly middle-class whites and blacks. For Smith, these Haitians constitute the “usual chaos” of Wellington, simultaneously apart from what Jerome Belsey describes as a “comforting dreamscape” (401), but somehow fully integrated:

He walked into a lively late-afternoon square. A saxophonist playing over a tinny backing track alarmed Murdoch. Jerome picked the dog up. A small food market had been set up on the east side, and this competed with the usual chaos of the taxi rank, students at a table protesting the war, others campaigning against animal testing and some guys selling handbags. Near the T-stop, Jerome saw the table his mother had described. It was covered with a yellow cloth embroidered with the words HAITIAN SUPPORT GROUP. (401)

Her exploration of the unfinished business of multiculturalism and the trouble with binary racial categories begins with the household drama in the Belsey home, but quickly moves out into the wider world of Wellington. Through the family's spoken and unspoken conflicts, Smith troubles easy understandings of race in terms of black and white and of American society as post-racial. And if readers are meant to read Wellington as a “house divided,” it is noteworthy that the first outsider to enter the biracial Belsey home is Monique, the Haitian cleaning lady – who complicates questions of race and inequality. Smith notes, for example, Kiki's uneasiness in her class position, “nervous of what this black woman thought of another black woman paying her to clean” (11).

Another Haitian, Pierre the driver – “one of the many from that difficult island who now found occupation in New England” (24) – not only makes it possible for Howard Belsey to avoid driving, but also feeds his middle-class, cosmopolitan pretensions. Later in the text we learn why the Langham Drive house does not quite function as a symbol of Howard's success, but initially Smith conveys Howard's class background through Pierre. Howard's familiarity (relationship is too strong a word) with the Haitian cabbie suggests a lifestyle quite unlike the existence someone with “a proper job, the kind the Belseys had had for generations” (25) would normally have.

Monique, Pierre, Chouchou and other apparently minor Haitian characters are just as important for the development of the novel as any of the Belseys or the Kipps. Their refusal to fit into the either–or paradigms – black or immigrant, insider or outsider, oppressed victim or, as Levi thinks to himself when he first encounters them, “situationists transform[ing] the urban landscape” (194) – forces the people of Smith's Wellington to recognize their contradictions and reexamine their relationships. Just when readers are ready to celebrate the triumphs of diversity, Haitians reveal the layers of racialized stratification in Wellington, where some blacks have been successful by creating a “little black enclave” (405) but are still far short of achieving insider status.

In this way, Haitian immigrants provide a sort of couleur locale that is crucial to the novel.Footnote 34 As I show in the next section, they move the text forward. And sometimes Smith's Haitian characters make the reader pause to question something familiar or taken for granted about contemporary urban space.

“SITUATIONISTS TRANSFORM THE URBAN LANDSCAPE”

Haitians are central to the story of Wellington. They work for low pay as servants; Haitian art is the commodity that seals the upper-middle-class position of the Kipps (113, 175); Haitian laborers do menial jobs, freeing African Americans like Carl Thomas and Elisha for better positions (374 and 387); and Haitian vendors sell the knockoff Louis Vuitton and Prada purses (246) that help Wellington consumers maintain the illusion of affluence. But a central theme in On Beauty is that the existence of diversity does not mean that belonging can be taken for granted, especially for blacks. The following exchange between Levi and Chouchou (renamed Choo because it suits his young African American friend) demonstrates that some blacks can only know Wellington through a subordinated position:

Levi Belsey and his mother Kiki repeatedly express their alienation and frustration about being in this liberal, intellectual Wellington community, but not of it. In a heated argument with her husband, a screeching Kiki confesses,

Everywhere we go, I'm alone in this … this sea of white. I barely know any black folk any more, Howie. My whole life is white. I don't see any black folk unless they be cleaning under my feet in the fucking café in your fucking college. Or pushing a fucking hospital bed through a corridor. (206; italics in original)

Kiki's outburst suggests that the inclusion of even middle-class blacks in places like Wellington requires a kind of excommunication from their racial communities.

In fact, the Belseys seem to be striving to secure their belonging by emphasizing the otherness of Haitians and black diasporans. Before instructing Monique to clean her study (11), Kiki introduces the Haitian maid in terms that allude to their sameness then quickly signals their difference from each other. Compare, for example, the descriptions of Kiki's long dreadlocks (14) to Monique's “own sparse hair”:

The new cleaner, Monique, was a squat Haitian woman, about Kiki's age, darker still than Kiki. This was only her second visit to the house. She wore a US navy bomber jacket with a turned-up furry collar and a look of apologetic apprehension, sorry for what would go wrong even before it had gone wrong. All this was made more poignant and difficult for Kiki by Monique's weave: a cheap orange synthetic hairpiece that was in need of renewal, and today seemed further back than ever on her skull, attached by thin threads to her own sparse hair. (10–11)

Kiki's later appraisal of the nameless Haitian trader (47) emphasizes his skin color and lean, almost undernourished, build.

The stallholder was a black man, exceptionally skinny, in a green string vest and grubby blue jeans. No shoes at all. His bloodshot eyes widened as Kiki picked up some hoop earrings … He was unsmiling and intent upon a sale. He had a brutal, foreign accent … Aside from her money, the guy seemed barely concerned with her, neither as a person nor as an idea. He did not call Kiki “sister”, make any assumptions or take any liberties. (47–48)

Like Howard's description of Pierre the driver (25), Kiki's interactions suggest that racialized difference, class and national difference intersect in complex ways to impact the possibility of meaningful encounters or connections.

Notably, the talented African American spoken-word artist from Roxbury turned Wellington hip-hop archivist achieves his new sense of belonging at Wellington by emphasizing his difference from the Haitians:

In Smith's Wellington, lower-class, unskilled African Americans, like Carl Thomas, are no longer at the bottom of the local racial hierarchy. They may be outsiders (from Roxbury), but, as Carl put it, they “don't clean shit” (387). However, Zora Belsey delivers a stinging reminder of the limits of their (and her own?) belonging later in the novel, in a confrontation with Carl:

You go to Wellington for a few months, you hear a little gossip and you think you know what's going on? You think you're a Wellingtonian because they let you file a few records? You don't know a thing about what it takes to belong here. (417)

The position of Haitians in On Beauty also highlights realities of racism that are usually invisible. In order to secure employment, for instance, blacks and other minorities often have to conform to a stereotype that compromises their dignity:Footnote 35

With everybody already seated, he [Howard] was left with the waiting staff, so black in their white shirts, holding high those trays of Wellington shrimp that always looked much better than they tasted. They were informal back here, laughing and whistling, speaking their boisterous Creole, touching each other. Nothing like the silent docile servers they became in hall. (342)

The dash of comic relief in Howard's experience in this space is notably absent in Choo's recollection of the same event. His experience of Wellington, and perhaps even migration to the United States in general, is much like Howard's depiction of Wellington shrimp. The reality of “a docile servant” is nothing like the better life that lured him to come to America, with its streets paved in gold, where economic opportunities are boundless:

“I was there Tuesday,” said Choo, ignoring him. “In the college.” He treated this word like ink upon his tongue. “Fucking serving like a monkey … teacher becomes the servant. It's painful! I can tell you, because I know.” He thumped his breast. “It hurts in here! It's fucking painful!” He sat up straight suddenly. “I teach, I am a teacher, you know, in Haiti. That's what I am. I teach in a high school. French literature and language.” (361)

I highlight these different relationships to the same racialized space not to claim that one is more genuine or valid than the other, but to point out that in On Beauty place is defined by the imaginations of many.Footnote 36

Smith also suggests that in highly stratified places such as Wellington/Boston, social divisions among blacks take on new meaning. When Levi first meets Carlene Kipps (from England), he cannot quite recognize her because differences among black people complicate his understanding of authentic blackness: “To Levi, black folk were city folk. People from the islands, people from the country, these were all peculiar to him, obstinately historical – he couldn't quite believe in them” (81). In his search for essence, difference has no place.Footnote 37 Throughout the novel, Levi's preoccupation with blackness influences his cognitive map of Wellington. His search for an authentic black identity leads him thirty minutes outside of Wellington, by train, to Boston and to a group of Haitian immigrants. Another important though minor character whom we meet through Levi is Felix (from Angola), described as “blacker than any man Levi ever met in his life”:

His skin was like slate. Levi had this idea that he would never say out loud and that he knew didn't make sense, but anyway he had this idea that Felix was like the essence of blackness in some way. You looked at Felix and thought: This is what it's all about, being this different; this is what white people fear and adore and want and dread. (242)

Diasporan blacks represent a dimension of blackness and non-belonging that somehow resonates with the young, biracial Belsey. Levi's depiction of how Haitians are received is an indication of both their social position and his:

These past few days, coming to meet the guys after school, hanging with them, had been an eye-opener for Levi. Try walking down the street with fifteen Haitians if you want to see people get uncomfortable. He felt like Jesus taking a stroll with the lepers. (243)

Haitians are apparently outside the boundaries of the Wellington community. Kiki's exchange with Carlene Kipps suggests that Levi is not alone in this assessment:

kiki: But you'll like it here in Wellington – generally, we all take care of each other pretty well. It's a community-minded kind of place …

carlene: But when we drove through town I saw so many poor souls living on the street! …

kiki: … We've certainly got a situation down there – there's a lot of very recent immigrants too, lot of Haitians, lot of Mexicans, a lot of folk out there with just no place to go. It's not so bad in the winter when the shelters open up. (93; emphasis added)

Again, I want to suggest that it is more than class, or even Americanness, that marks Levi's and Kiki's distinctions (notably, Carlene Kipps, a black British woman, does not remain an outsider for long). Spatial boundaries cement these differences. Place reaffirms a moral order of us “here in Wellington” and them “down there” and becomes a basis for distinguishing one group from another. Feminist geographer Melissa Gilbert makes a similar argument about gender.Footnote 38 Our ideas about “race,” immigration, and poverty are not only socially constructed but spatially constructed through notions of the inner city, the underclass, immigrant neighborhoods and, I would add, the campus.

Moreover, Haitians reveal contradictory black diasporan relations, including Carl's indifference/hostility to the immigrant underclass (see 135), hierarchical relations among blacks (see 11), Kiki's unfulfilled expectations of identification with foreign-born blacks (48), and the cultural gulf that exists among blacks (245). The following moment best captures the challenges diasporization creates when several black groups are confined to a small geographic and metaphorical space in the city:Footnote 39

Choo looked Levi straight in his eyes, hoping for a fellow feeling. “I really fucking hate to sell things, you know?” he said, pretty sorrowfully, Levi thought.

“Choo – you ain't selling, man,” said Levi keenly in reply … “This ain't like working the counter at CVS! You hustling, man. And that's a different thing. That's street. To hustle is to be alive – you dead if you don't know how to hustle. And you ain't a brother if you can't hustle. That's what joins us all together – whether we be on Wall Street or on MTV or sitting on a corner with a dime-bag. It's a beautiful thing, man. We hustling!” …

“I don't know what you are talking about,” said Choo, sighing. “Let's get going.” (245)

Importantly, Smith mostly uses Levi's “innocent eye” to learn about black Boston. Letting him assume temporary control of the narrative, readers get to know Haitians through the eyes of an admiring black character. He experiences “the street” in a less threatening and a less exotic manner than either of his siblings. The passage cited in the epigraph is one example of what he feels there (see 194). And Levi is the only one of Smith's characters who is “overwhelmed by the evil that men do to each other” (355) or moved by Haitian music, “the plangent, irregular rhythm, like a human heartbeat” (408). Using Levi's admiration for the cultural diversity of black life, and his friendship with Choo and the other Haitian men in this way, permits a welcome departure from the scholarly emphasis on social distancing and conflict that has become pervasive in black immigrant studies.Footnote 40 And although Smith is silent about potential connections across differences that involve Haitian women, she hints at the possibilities for black diasporan relations:

Choo clasped his friend around his shoulders and had the gesture returned. “Your brother,” he said affectionately, “thinks of all his brothers. That's why we love him – he's our little American mascot. He fights shoulder to shoulder with us for justice.” (404)

To extend the argument further, Haitians exist as the foil against which a primary narrative strand of the novel unfolds. Wellingtonians struggle to live under the influence of a theoretical color-blindness and egalitarianism in their privileged white cocoon when race and inequality structures everything around them. The institution and the place quietly benefit from migrants who are employed at low wages unacceptable to established residents. Yet Wellington is unsure how to reconcile the challenges the outside world creates with any utopian conception of righteousness or beauty. In a climactic scene, Levi points out not only Kiki's complicity in the exploitation of Haitians but also the hypocrisy of the liberal, insulated world of Wellington:

Kiki: “I understand that you had concerns about these people, but, baby, Jerome's right, this is not the way you go about solving social problems, this is not how you –”

“So how do you do it?” demanded Levi. “By paying people four dollars an hour to clean? That's how much you pay Monique, man! Four dollars! If she was American you wouldn't be paying her no four dollars an hour. Would you? Would you?” (429)

In short, a large part of the story Zadie Smith aspires to tell about American race relations relies on Haitians. Smith could not imagine a place such as Wellington located in or near Boston that did not include Haitian immigrants. Their visibility in On Beauty locates the novel, letting us know that the story does not take place in Chicago, New York City or even Hanover, NH. In addition to evoking a particular setting or period, Haitians reveal the complexity of inequality of urban life in the post-civil rights movement era. And, perhaps most importantly, their experiences expose the limited narratives available for blacks in a place like Smith's Wellington/Boston.

TRAP OF VISIBILITY

Fischer is critical of Smith for “making her characters do double-duty as vehicles for the ideas in her books.”Footnote 41 And in keeping with this observation, the visibility of Haitians in Zadie Smith's novel is not unproblematic. Despite their (ever-)presence in On Beauty, Haitian subjectivity is overlooked in many ways. The Haitian characters are all one-dimensional, typecast as maids, cab drivers and street vendors who are never fully realized. All of the narrator's descriptions resort to the same generalized texture of poverty and a kind of monolithic blackness. The Haitian characters have little dialogue, no interior monologue to speak of, and none of the double consciousness the other black characters enjoy. The gesture of representational inclusion seems to function, simultaneously, as an act of containment. The inclusion of Haitians in On Beauty is analogous to an imagining of the city, simultaneously and contradictorily, as multicultural and still predominantly white. Haitians can be part of the picture, as long as they stay in their place.

And it would be fair to ask why Smith's Haitian characters lack intellectual depth, why are they so one-dimensional? Echoing Ralph Ellison's critique of African American caricatures in American literature:

… There were, and are, enough exceptions in real life to provide the perceptive novel with models. And even if they did not exist, it would be necessary, both in the interest of fictional expressiveness and as examples of human possibility, to invent them.Footnote 42

Despite the number of Haitians in Boston with varying personal histories or positions in economic space, Smith retells an urban narrative that sees all Haitians, in all places, as fundamentally the same. Actual Boston Haitians inhabit hers more as echoes or types than as fully imagined identities; they provide “partial presences” in otherwise unpopulated characters.Footnote 43

Smith's representation of urban space concerns me as a social scientist because of the power of fiction-truths and other narratives to constitute places and subjects.Footnote 44 Timothy Oakes argues, “If place is to be marshalled as a theoretically rich contribution to interdisciplinary cultural studies, it would be unfortunate, in evaluating the historical legacy of place in modern social thought, to confine our critical surveys to social science.”Footnote 45 Already, the line between fact and fiction is fuzzy. As readers we often put as much stock in fictional truths as we do in scholarly work. Critical ethnographers, historians and biographers readily admit that the work they produce is “fiction” in the sense that it is constructed or fabricated. When realist writers infuse their work with lifelike visual clues and real-world dialogue, when their engaging story settings evoke familiar places with a distinct culture or identity, or when novels rely on the details of actual events, the line between fact and fiction is blurred even more.Footnote 46

No matter how poorly imagined the Haitians in Smith's Wellington are, they signal a sensitivity to the significance of locality that helps the author create an authentic sense of place. Relph uses the concept of authenticity to denote an “experience of the entire complex of the identity of places – not mediated and distorted through a series of quite arbitrary social and intellectual fashions about how that experience should be, nor following stereotyped conventions.”Footnote 47 Smith conveys, with ethnographic sincerity, what Wellington looks like and feels like and the broad spectrum of experiences, meanings and potential futures it offers to her various characters.

Moreover, On Beauty opens a space to focus on aspects of belonging, blackness and place that social scientists have only recently begun to address in their scholarship. Many studies of black immigrants, for example, are written in a way that flattens the place-specific dimensions of experience. They describe the life of the group being considered (1) as if it were capable of being studied apart from the city in which it is situated or (2) as if it would be exactly the same regardless of where it occurred. Urban anthropologist Jack Rollwagon identified this tendency as the “city as constant” perspective.Footnote 48 More often than not, the city is held constant to stress the similarities of different contexts and the generalizability of a researcher's findings.

Before we dismiss the sense of place in Zadie Smith's Wellington as superficial in the sense that it comes from the kind of “abstract knowledge about a place [that] can be acquired in short order,”Footnote 49 we might recall, as Tynan suggests, “Helen Schlegel's appraisal of books [in E. M. Forster's Howard's End], that they ‘mean us to use them for sign-posts, and are not to blame, if, in our weakness, we mistake the signposts for the destination’ (Forster 114).”Footnote 50 Zadie Smith helps illuminate the significance of place in social relations and in post-racial America. And by exploring contemporary Boston as a context for black immigrant life, she challenges scholarly claims to privileged readings of the city. Although On Beauty might not ever be described, in terms of conventional understandings, as evidence, like the imaginative ethnographies of Paule Marshall and Claude McKay, the work enlarges our understanding of the spaces blacks from diverse backgrounds inhabit.Footnote 51