Elections produce a significant number of votes that are assigned neither to political parties nor to political candidates. We refer to these as invalid votes. By invalid votes, we mean manifestations of electoral processes that result in ballots that are not counted for the purpose of mandate allocation. These principally include blank votes, null votes and spoiled votes. Invalid votes were for a long time of peripheral interest to analysts of electoral behaviour but in recent years a plethora of comparative research has shifted attention to them, partly because of their significant presence in some countries (Cohen Reference Cohen2017, Reference Cohen2018; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Moral Reference Moral2016; Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Singh Reference Singh2017; Solvak and Vassil Reference Solvak and Vassil2015; Uggla Reference Uggla2008). Invalid voting has also gained broader attention in the public debate when mobilizing for deliberate vote invalidation has become a widely used political practice – often through social media – in such diverse settings as Serbia (Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik Reference Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik2014), Bolivia (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014), Hungary (Gessler Reference Gessler2017) or Mexico (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013). The legitimacy of elections that exhibited an extraordinary share of invalid votes was recently questioned after the presidential elections in France (Gougou and Persico Reference Gougou and Persico2017). Such high rates of protesting or erring voters generally undermine electoral mandates, particularly in close and politically salient elections. Invalid voting is of crucial importance in fragile democracies in Latin America, a region that has the largest share of invalid votes in both presidential (Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016) and legislative elections (Cohen Reference Cohen2017).

Given the growing importance of invalid voting and expanding – but still incipient and mostly fragmented – research, we can still draw only a limited picture of the origins of invalid voting and of the causal mechanisms underlying the many structural, circumstantial or individual factors hypothesized to affect it. We therefore put forward a new theory of the sources of invalid voting by presenting an original causal typology of the determinants of invalid voting. Unlike previous treatments, our proposal satisfies the three criteria for constructing analytically useful typologies with categories that are: (1) mutually exclusive, (2) exhaustive and (3) comparable (Gerring Reference Gerring2001: 120). The proposed classification simplifies the origins of invalid votes into distinct categories, drawing attention to the fact that each category requires different theoretical explanations through different causal mechanisms. Second, we carry out a systematic meta-analysis of all aggregate-level studies (both within-country and cross-national) of the determinants of invalid voting and draw conclusions from both qualitative and individual-level quantitative research. Third, finding that the state of literature is characterized by contradictory findings, we explain the principal reasons for this and chart an agenda for future research.

Origins of invalid voting: a conceptual framework

The principal theoretical classifications simply distinguish the origins of invalid votes by the nature of variables used in empirical models. This divides them into explanations based on ‘institutions, society or protest’ (McAllister and Makkai Reference McAllister and Makkai1993; and followed by Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007). The first approach includes variables such as compulsory voting, types of electoral system, ballot structure and the concurrence of elections. The socioeconomic approach concentrates on economic development, literacy rates and education. The final political-protest cluster explains invalid voting as an intentional act, motivated by voters’ dissatisfaction with the political circumstances or economic situation (Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995; Uggla Reference Uggla2008; Zulfikarpasic Reference Zulfikarpasic2001). Such classifications do not, however, create mutually exclusive categories because several theorized causal mechanisms (for example, protest motives) of invalid voting correspond to two or more categories and empirical variables.

Other classifications follow the criteria of comparability. They differentiate highly politicized invalid votes from apathetic invalid voters (Stiefbold Reference Stiefbold1965), incompetence, social marginality, the political and polity model (Uggla Reference Uggla2008), voter error, protest voting and voter apathy (Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016) or voter confusion, voter discontent and voter apathy (Moral Reference Moral2016). Yet such classifications have not been exhaustive, leaving some types of invalid ballots unaccounted for. The deficiency is in neglecting the role of electoral institutions (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013) and a weak conceptualization of voter dissatisfaction leading to ballot invalidation.

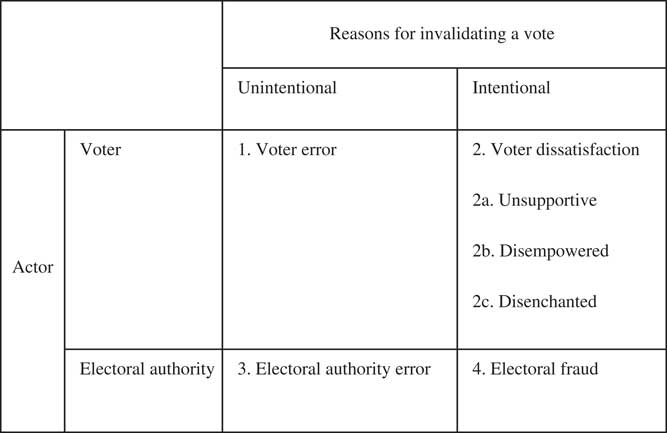

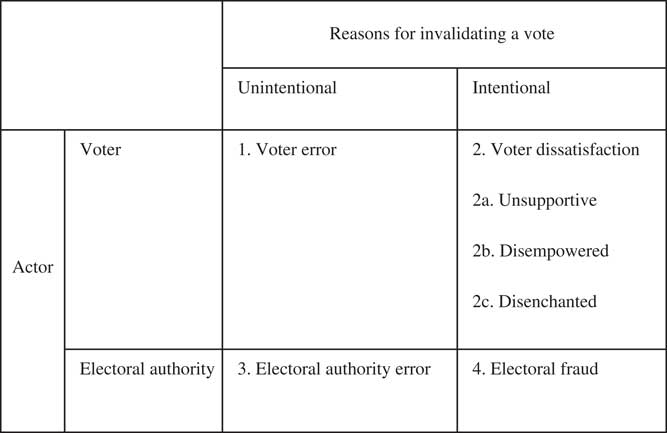

We therefore propose a novel causal typology providing theoretically distinguishable causal mechanisms of the origins of invalid voting based on two dimensions: the actor that invalidates the vote (voter or electoral authority) and the intentionality of such invalidation (see Figure 1). In the dimension where the voter appears as the actor, we differentiate the voter error model – if the voter considers her vote valid, but it is invalidated in the process of counting – and three models under which the ballots are spoiled by voters intentionally manifesting one of three types of dissatisfaction. In the second actor dimension, invalid votes are erroneously (unintentionally) produced by incompetence and negligence by the electoral authority. But the electoral authority may also intentionally invalidate valid ballots to manipulate electoral outcomes by conducting an electoral fraud. We now briefly discuss the causal mechanisms underlying each type.

Figure 1 Classification of the Origins of Invalid Votes

Voter Error Model (Type 1)

This model supposes that some voters are incompetent to cast a valid vote but intend to do so. The first studies on invalid voting showed that a low level of education of the electorate is to blame for an excessive number of such invalid votes (Mott Reference Mott1926). Invalid voting results from an unintentional error of the voter due to the complex electoral system or ballot design (Carman et al. Reference Carman, Mitchell and Johns2008; Herron and Sekhon Reference Herron and Sekhon2005; Kimball and Kropf Reference Kimball and Kropf2005; Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995; Taylor Reference Taylor2012), which interact with the voter’s lack of skill and competence to cast a ballot correctly (Hill and Young Reference Hill and Young2007; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Mariën and Pauwels2011; McAllister and Makkai Reference McAllister and Makkai1993; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Reynolds and Steenbergen Reference Reynolds and Steenbergen2006). Studies generally point out that some institutional designs are too demanding and make errors more likely.

Voter Dissatisfaction (Type 2)

A proportion of invalid ballots are cast intentionally by voters to demonstrate their dissatisfaction. However, such protest has rarely been theorized in a systematic manner. We differentiate three types of invalid voting by dissatisfied voters relying on a concise causal typology that classifies political dissatisfaction along two dimensions: the level of political support and the level of subjective political disempowerment (Christensen Reference Christensen2016). This typology improves significantly on earlier theoretical accounts, which have mapped political dissatisfaction on a single dimension, seeing it either as a result of inadequate political support, political trust or satisfaction with democracy (Dalton Reference Dalton2004; Easton Reference Easton1965), or as a result of citizens having low levels of internal political efficacy and a perceived inability to influence political decisions (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Stoker Reference Stoker2006). The different combinations along these two dimensions produce theoretically distinguishable and sharply different types of citizen dissatisfaction: unsupportive, disempowered or disenchanted. These types can be directly related to existing theoretical explanations of the origins of invalid votes.

Unsupportive Invalid Voting

Invalid voters who combine a low level of political support with a high degree of subjective empowerment are best described as unsupportive in terms of the manifestation of their political dissatisfaction. Such individuals are critical citizens who distrust the authorities but have a high level of political interest (Christensen Reference Christensen2016: 785). Their invalid vote can be construed as an active and informed protest against the existing flawed political system. Such invalid voting has been theorized to be a sign of a well-considered protest aimed against authoritarianism and the poor grade of democracy (Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007: 440). This type of protest vote is an illustration of voters having significant political reasoning and sophistication. It is predominantly a protest made by middle-class urban and well-educated voters (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; McAllister and White Reference McAllister and White2008), but not exclusively. Unsupportive protest voting might occur where there is a worsening quality of democracy, increased corruption or weak electoral competition.

Disempowered Invalid Voting

At the opposite end of the continuum are those dissatisfied citizens with a high level of political support but a low sense of subjective political empowerment. Such disempowered individuals doubt their abilities to affect political decisions and their invalid votes reflect apathy and lack of interest. Some people do not want to be active in politics, which they consider uninteresting, unimportant and complicated (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002). Disempowered citizens cast an invalid vote because they feel that some elections are less important and their efficacy is low (Arbache et al. Reference Arbache, Freire and Rodrigues2014). A similar mechanism may also be derived from the rational choice theory of voting (Downs Reference Downs1957; Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968), which views the voting decision as a function of the preliminary calculation of the extent to which the vote is decisive and of the costs and benefits of a preferred candidate winning. As the perceived importance of the elections decreases, the apathetic and disempowered voters may under some circumstances cast an invalid ballot rather than abstain for the same reasons. The factors connected to this mechanism reflect two types: a low concentration of votes and the closeness of the electoral race. Both influence the rates of ballot invalidation (Uggla Reference Uggla2008: 1158). A parallel effect on invalid voting may be traced in a poorly differentiable ideological or political offer from the political parties (Moral Reference Moral2016: 6). This model, however, does not assume any wilful or protest behaviour. So why do voters bother to turn out but not vote? We assume that for some voters, participation in elections represents a moral and civic duty (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008) and they cast an invalid ballot when less is at stake and they consider their vote to be less decisive. Compulsory voting drives up the intentional ballot spoilage by uninterested and politically ignorant voters in a similar way (Singh Reference Singh2017: 4).

Disenchanted Invalid Voting

The last category consists of citizens who combine both low subjective political empowerment and low political support. Disenchanted citizens are alienated from the political system and have lost belief that they can influence political outcomes. This attitude entails emotional responses to politics that are increasingly negative in tone and character. Invalid votes may be considered a form of protest implying voters’ disenchantment with bad or worsened individual socioeconomic status and with the traditional political elites, as well as reflecting the voters’ generally anti-democratic and anti-system stances. This anti-political culture manifested in a high incidence of invalid votes poses the most serious threat to democracy because it erodes the legitimacy of elections. Invalid ballots reflect a weak political competition since voters’ opinions are that ‘it does not matter who wins the election’ (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013: 73; Zulfikarpasic Reference Zulfikarpasic2001: 267). Individuals who are distrusting of or discontented with the democratic system may become irritated if their electoral participation is effectively enforced, and thereby they become less willing to cast a meaningful ballot (Singh Reference Singh2017: 3).

Electoral Authority Error (Type 3)

Electoral authorities can also be blamed for a proportion of invalid votes due to unintentional error. Electoral commissions may accidentally invalidate a lawfully valid ballot because of the complexity of the counting process of complicated ballots or due to complicated election proceedings. The literature on invalid votes has not paid adequate attention to the issue or the quality of the election administration. Most studies have focused on various electoral procedures and settings (Herron and Sekhon Reference Herron and Sekhon2005; Kimball and Kropf Reference Kimball and Kropf2005). Only one study of Italian elections explains invalid ballot rates as a product of the detection of invalid ballots by the election officers and party representatives under elections that are not close enough to merit counting the ballots properly (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013). Votes being counted incorrectly because of negligence are relatively common. An Argentinian study found that counting irregularities occurred in more than a third of ballot boxes and are far more likely to occur in poorer municipalities (Ronconi and Zarazaga Reference Ronconi and Zarazaga2015).

Electoral Fraud (Type 4)

The intentional invalidation by the electoral authority of ballots that were cast as valid is responsible for a proportion of invalid ballots. There have been several explorations of the use of ballot invalidation to commit fraud (Herron Reference Herron2010, Reference Herron2011a, Reference Herron2011b; Losada Reference Losada2006; Manning Reference Manning2010; Mebane Reference Mebane2010). One way is for the electoral authority to invalidate part of the ballots for the (usually opposition) candidate against whom the fraud is perpetrated. Such practices have been reported in Mozambique where the polling station staff usually added an extra ink mark on ballots for opposition candidates to make them invalid, or when – in another presidential election – the central electoral authority decided to invalidate a large number of votes, thus changing the election outcome (Manning Reference Manning2010: 159). A negative association between invalid vote share and votes for Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and an application of Benford’s Law on invalid voting indicated that vote fraud and ballot box stuffing were likely to have been practised in the 2009 Iranian elections (Mebane Reference Mebane2010). A similar analysis revealed no evidence of fraud in Ukraine (Herron Reference Herron2011b). Where ballot box stuffing occurs, lower levels of invalid votes in situations of high reported turnout (that is, the turnout is partially fabricated by stuffing the box with valid ballots) are indicative of electoral fraud, as in Azerbaijan (Herron Reference Herron2010: 422) or Colombia (Losada Reference Losada2006). Because both high and low levels of invalidation can be associated with electoral fraud, and because both processes can be at work simultaneously (Herron Reference Herron2001b: 51), invalid ballots are a problematic indicator of fraud.

Methodological Strategies and Substantive Results

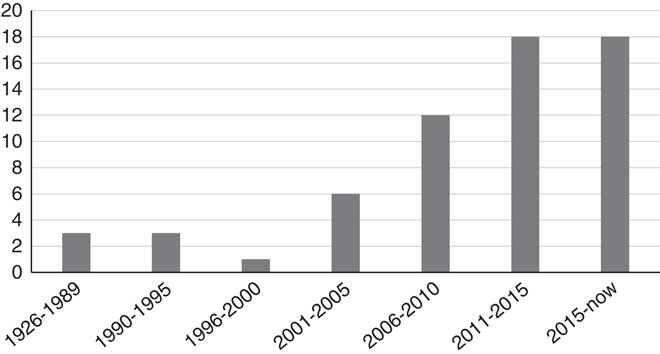

This section provides a summary of the principal conclusions in the existing research. We identified 54 research articles whose principal aim was to explain the determinants of invalid voting up to 2018 (see Figure 2). We manually searched Google Scholar for citations to any given article. When another article with the main theme of invalid ballots was found this way, we again searched for the articles that have cited it. This mimics the logic of the snowballing technique, guaranteeing that most articles which aim to explain the occurrence of invalid voting are included in the analysis. Further, we included as many relevant non-English papers as possible while dismissing descriptive national reports lacking coherent theory and causal explanations. There are countless other pieces of published research where invalid voting is not the main theme and we also comment on these where appropriate.

Figure 2 Number of Articles on Invalid Voting Source: The authors’ elaboration.

The research agenda on invalid ballots has witnessed a gradual improvement in the methodological rigour and diversity of analytical techniques used. While earlier studies relied exclusively on aggregate-level research, the recent availability of survey data has allowed us to directly test the observable implications of the theories of voting behaviour. Despite that, the aggregate research continues to dominate the field. We counted 26 aggregate-level studies employing regression models of the determinants of invalid voting (Ackaert et al. Reference Ackaert, Wauters and Verlet2011; Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013; Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Cisneros and Freigedo Reference Cisneros and Freigedo2014; Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Damore et al. Reference Damore, Waters and Bowler2012; Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Galatas Reference Galatas2008; Gendźwiłł Reference Gendźwiłł2015; Herron Reference Herron2011a; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Mariën and Pauwels2009; Kimball and Kropf Reference Kimball and Kropf2005; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; McAllister and Makkai Reference McAllister and Makkai1993; Nihuys Reference Nihuys2014; Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017; Pion Reference Pion2010; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995; Reynolds and Steenbergen Reference Reynolds and Steenbergen2006; Rosenthal and Sen Reference Rosenthal and Sen1973; Singh Reference Singh2017; Socia and Brown Reference Socia and Brown2014; Superti Reference Superti2015; Uggla Reference Uggla2008), while 11 studies utilize data from individual survey responses (Arbache et al. Reference Arbache, Freire and Rodrigues2014; Borba Reference Borba2008; Carlin Reference Carlin2006; Cisneros Reference Cisneros2016; Cohen Reference Cohen2017; Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Mariën and Pauwels2009; Katz and Levin Reference Katz and Levin2016; Moral Reference Moral2016; Singh Reference Singh2017; Solvak and Vassil Reference Solvak and Vassil2015). Two studies combine both (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016). There are also two studies using experimental designs (Ambrus et al. Reference Ambrus, Greiner and Sastro2015; Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar Reference Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar2015) and one combining experimental and aggregate data analysis (Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017). Two studies use natural or quasi-experimental designs (Hirczy Reference Hirczy1994; Singh Reference Singh2017). There are nine other studies on invalid voting that do not use inferential statistics to test causal models (Cohen Reference Cohen2016: 83; Giugăl and Ogaru Reference Giugăl and Ogaru2013; Hill and Young Reference Hill and Young2007; Mackerras and McAllister Reference Mackerras and McAllister1999; Mott Reference Mott1926; Śleszyński Reference Śleszyński2015; Stiefbold Reference Stiefbold1965; Young and Hill Reference Young and Hill2009; Zulfikarpasic Reference Zulfikarpasic2001) and two qualitative case studies (Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik Reference Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik2014; Pehr Reference Pehr2009).

There is little disagreement that aggregate-level research has many shortcomings, but there are important reasons why such research is crucial to our understanding of invalid voting. Individual-level research should be preferred whenever attitudinal and behavioural characteristics of individuals are posited as explanatory factors, while aggregate research helps more to elucidate institutional determinants. Hierarchical models that include both levels (Cohen Reference Cohen2017; Singh Reference Singh2017) are able to secure the best of both worlds but have limitations of their own.

Perhaps the biggest shortcoming of aggregate research concerns the ecological inference problem, implying the inability of researchers to infer individual behaviour from aggregate data. However, there is an important reason why such strategies are justifiable when researching invalid votes. Self-reported responses in individual surveys obviously do not count invalid ballots cast due to voter error – that is, votes that are later invalidated by the electoral authorities. Since there is sufficient theoretical reason to suspect that many invalid votes are produced this way, many research settings need a measure that includes both intentional and unintentional invalid votes. This presents a trade-off: individual data and no ecological fallacy but incomplete figures about the extent of invalid voting, or aggregate data, an ecological inference problem, but complete figures on invalid voting. This trade-off is non-existent in the related literature on turnout where individual-level studies should be a fortiori preferred: there is no unintentional turnout.

Aggregate-Level Research: A Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis is based on articles published before June 2018 and which fulfil the following criteria: (1) invalid voting was used as the dependent variable; (2) the empirical model controlled for other determinants; and (3) the authors presented estimates of the statistical significance of the coefficients. We selected only the main models if the author presented a series of control models or series of various model specifications as robustness checks. In the case of hierarchical regression models (Singh Reference Singh2017), we selected variables from only the second level (compulsory voting and quality of democracy). We also compiled a list of all the variables used in all statistical models and subsequently classified variables with similar operationalization to appropriate concepts. We included only those variables that were used five or more times. This search has produced a total of 28 articles and 37 models. The resulting data set includes nine variables and 129 tests. We follow the coding procedure by Kaat Smets and Carolien van Ham (Reference Smets and van Ham2013: 3): a test is considered as a ‘success’ when a coefficient is statistically significant and in a hypothesized direction, an ‘anomaly’ as −1 if a coefficient is significant but in an opposite direction and a ‘failure’ if there was no statistically significant association at all. We compute the success rate and average effect size (rav) across all studies. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Tests of the Determinants of Invalid Voting

Note: Success rate is computed as the number of successes divided by the total number of tests. Average effect size is computed in two steps. First, successes minus anomalies are divided by the number of tests within a study. Second, each effect size is summed and divided by the total number of studies. A two-tailed t-test statistic is computed if the value is significantly different from 0 (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Compulsory voting provides the most robust result, being statistically significant and positively associated with invalid voting in all models. The quality of democracy is another robust factor explaining the occurrence of invalid votes. In only one in five models was the coefficient statistically insignificant and we do not observe an alternative situation in which the quality of democracy is positively correlated with invalid votes. The indicators of political competition – the fragmentation and competitiveness of the elections – show less consistent results. The rest of the variables feature some degree of inconsistency as we observe either statistically insignificant or contradictory empirical findings. The socio-demographic variables – unemployment, educational level, urbanization, age and wealth – are the most frequently used as they usually serve as controls, yet they have the lowest success rate. There are many other variables which did not pass the threshold of inclusion of at least five cases but some of which merit further exploration in future research.

Compulsory Voting

No other variable performs a more consistent effect on invalid voting than the existence of obligatory voting laws. All aggregate-level quantitative studies report a positive effect (Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Reynolds and Steenbergen Reference Reynolds and Steenbergen2006; Singh Reference Singh2017; Uggla Reference Uggla2008). Moreover, this effect is substantively strong. Studies that use a four-point scale of the severity of compulsory voting laws (Fornos et al. Reference Fornos, Power and Garand2004) report a 1.78 percentage increase in invalid voting for every one-point increase in a global comparison (Uggla Reference Uggla2008: 1158), and a 2.3 percentage point increase in a comparison of Latin American and post-communist presidential elections (Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016). Across the most developed OECD countries, compulsory voting is blamed for one of the highest rates of informal votes in Australia (Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016; Hill and Young Reference Hill and Young2007; McAllister and Makkai Reference McAllister and Makkai1993; Young and Hill Reference Young and Hill2009) and in Belgium (Ackaert et al. Reference Ackaert, Wauters and Verlet2011; Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Mariën and Pauwels2009; Pion Reference Pion2010) and Brazil (Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995).

Invalid votes under compulsory voting laws serve as an exit option for uninterested citizens who would rather not turn out at all, suggesting disempowered voters (Type 2b) (Hirczy Reference Hirczy1994; Singh Reference Singh2017; Uggla Reference Uggla2008; Zulfikarpasic Reference Zulfikarpasic2001), implying that invalid votes may be a functional equivalent of abstention in compulsory voting systems (Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995). If the political offer is too complex, less politically sophisticated voters are likely to cast an invalid vote (Moral Reference Moral2016: 5). Interestingly, those mechanisms that decrease voter turnout also increase invalid votes under compulsory voting. This effect of voting compulsion should strongly caution those who view obligatory voting laws as a magic bullet for promoting voter turnout (Franklin Reference Franklin1999; Jackman and Miller Reference Jackman and Miller1995; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1997; Norris Reference Norris2002). Although compulsory voting increases turnout, more than half of the turnout gained by forcing voters to the polls comes in the form of invalid ballots in a global cross-national comparison (Uggla Reference Uggla2008: 1160). These findings have important implications for the literature that argues that compulsory voting should be used to boost turnout.

Democracy

There is conclusive evidence that citizens in low-quality democracies or semi-democratic regimes are more likely to cast invalid ballots. The only insignificant test comes from a measurement of democratic experience (measured in the number of years since democratization) (Uggla Reference Uggla2008), but the six remaining tests (Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Singh Reference Singh2017; Uggla Reference Uggla2008) show that democracy has a substantively strong negative effect on ballot invalidation, measured both statically – usually through the Freedom House index – and dynamically as the change in the value of this index (Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007), or Polity IV index (Singh Reference Singh2017).

The robustness of this relationship results from causal mechanisms derived from several causal types in our classification affecting invalid voting in the same direction. Electoral fraud and electoral malpractice are more frequent in low-quality democracies (Birch and van Ham Reference Birch and van Ham2017), so invalidation by state authorities is also more likely there (Types 3 and 4). But most studies associate invalid voting in less democratic regimes with protest behaviour by citizens (e.g. Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007). Deliberately spoiling one’s ballot is an act of protest at an insufficient party offer in settings where pluralistic competition is limited and voters cannot express their preference for a viable opposition alternative.

Campaigns for invalidating ballots have been common in semi-democratic elections, as in Indonesia under the Suharto regime where voters cast blank ballots as a sign of their dissatisfaction with the restrictions surrounding the elections (Cribb Reference Cribb1984: 659; King Reference King1994: 9) as well as a form of opposition to the regime (Ananta et al. Reference Ananta, Arifin and Suryadinata2005: 19). Similarly, ballot spoilage demonstrates a protest at the electoral system and the official regime candidates in non-democratic elections in Iran (Samii Reference Samii2004: 419). Invalid voting in the electoral-authoritarian regime of Azerbaijan has also been construed as an outright expression of political dissent by voters (Herron Reference Herron2011a).

Closely related to protest behaviour but distinct in nature is casting invalid ballots in fully non-democratic regimes where voters are not allowed to choose between political alternatives. To the extent that such ballots are used and counted (and if such counts may be trusted), blank ballots were viewed as perhaps the only electoral way of demonstrating discontent in the Soviet Union (Gilison Reference Gilison1968). In Czechoslovakia, this strategy was used as early as the first election after the communist takeover in 1948, when 9.3 per cent of voters cast blank ballots as a protest at the lack of options when the choice was to vote for a single candidate list led by the Communist Party (Pehr Reference Pehr2009: 104). In Cuba, this form of displaying political discontent is more common in areas with highly educated citizens and in regions closer to the capital city Havana, indicating that invalid ballots are cast in places where more political information is circulated and where there is less strict political control (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Galvis and Superti2017). Casting blank or null ballots signals opposition to non-democratic regimes and reflects critical protest behaviour (Type 2a).

Political Competition

Numerous studies find that political competition has a substantial effect on electoral behaviour. Low competitiveness and the absence of a preferred political alternative is often associated with invalid voting. Most operationalizations use traditional indexes of the effective number of parties or candidates, but some rely on their absolute numbers. Others employ largest party vote shares or differences between the first and second parties. Building on the research that found a negative relationship between the degree of fragmentation and turnout (Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Franklin Reference Franklin2004; Jackman Reference Jackman1987; Kostadinova and Power Reference Kostadinova and Power2007), most researchers have tested whether such fragmentation is positively correlated with invalid voting. Citizens are more likely to waste their votes under fragmented party systems as the chances of their preferred candidate winning decline. Yet, the overall results do not provide a clear and consistent picture. Most studies agree on the positive effect of party system fragmentation (Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016) as well as the simple number of candidates (Rosenthal and Sen Reference Rosenthal and Sen1973; Superti Reference Superti2015) or parties (Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995). But two studies found the opposite. Negative associations are reported from studies of Italian (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013) and Colombian municipal elections (Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017: 103).

The reasons for including the margin of victory in models of invalid voting as the most frequent operationalization of the decisiveness of the electoral race (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013; Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016; De Paola and Scoppa Reference De Paola and Scoppa2014; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Uggla Reference Uggla2008) are derived from a theoretical justification that close electoral races increase the perceived utility of one’s vote (Downs Reference Downs1957; Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968). A similar rational choice case is made for casting a valid as opposed to invalid vote. The closer the electoral results, the lower the numbers of invalid votes as the voters perceive that their vote has a bigger value. Other measurements include the vote share of the first party (Uggla Reference Uggla2008), the specific competitiveness index (Galatas Reference Galatas2008) and a square root of victory margin (Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017). One of the two deviant cases is Italy, where the administrative error of the electoral authority is assumed to operate (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013), but all other studies report the assumed positive relationship of closeness to invalid voting.

Unemployment

The majority of tests confirm that unemployment has a positive effect on invalid voting. Overall, in seven studies the positive effect was statistically significant (Ackaert et al. Reference Ackaert, Wauters and Verlet2011; Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013; Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Nihuys Reference Nihuys2014) and in six insignificant but in the hypothesized direction (Herron Reference Herron2011a; Superti Reference Superti2015; Uggla Reference Uggla2008). There is only one anomalous finding: unemployment has been consistently strongly inversely related to the casting of blank ballots in Canadian elections (Galatas Reference Galatas2008: 466). To the extent that unemployment serves as a proxy for protest-driven electoral behaviour, this protest may be channelled through voting for existing parties rather than casting invalid ballots. The reviewed studies mostly use unemployment as a control variable and do not pay much attention to the theoretical debate on the hypothesized causal effect of unemployment. A disenchantment motive is the most frequent explanation (Type 2c in our typology). However, unemployment also serves as a proxy variable for the level of economic development. The latter is linked to the social marginalization or exclusion of low-skilled and low-educated unemployed who do not turn out and if they do they are more likely to cast an invalid vote due to low skills (Type 1).

Education

Existing research has drawn a rather complex picture as several contradicting causal mechanisms were identified with respect to educational attainment. Although most comparative studies report a negative relationship between educational level and invalid voting (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Galatas Reference Galatas2008; Kimball and Kropf Reference Kimball and Kropf2005; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995; Reynolds and Steenbergen Reference Reynolds and Steenbergen2006; Socia and Brown Reference Socia and Brown2014), four studies found an opposite relationship (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Cisneros and Freigedo Reference Cisneros and Freigedo2014; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Pion Reference Pion2010), while three other studies report a statistically insignificant relationship (Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Superti Reference Superti2015; Uggla Reference Uggla2008). Rather than low-skilled, low-educated voters making mistakes at the polls (Type 1), it might rather be the highly educated and sophisticated ones who intentionally express their dissatisfaction with current politics, authoritarian tendencies or corruption through ballot invalidation (Type 2a). Furthermore, there are reasons to expect that the two opposing explanations operate simultaneously in all elections (e.g. Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013). Which one prevails depends on many circumstantial factors. The effect of the education level is thus contextually dependent and the weak contradictory findings may reflect inadequate methodological strategies in separating both causal types, rather than the insignificance of education.

Urbanization

Variables measuring urbanization produce similarly inconsistent results. This is not surprising because more educated people live in metropolitan areas. Two contradictory explanations of the causal link between urbanization and invalid votes have been put forward. The first contends that the urban citizens are better informed about the electoral process and exposed to more intense electoral campaigns (Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995: 801). They are also better educated than rural dwellers and are less likely to protest against the liberal democratic system (Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018). Furthermore, rural areas would be expected to feature a higher incidence of invalid votes because of stronger social control whereby individuals feel obliged to vote because of social pressure and the blank ballot functions as an effective substitute for abstention (Zulfikarpasic Reference Zulfikarpasic2001: 259). The alternative explanation carries contradictory predictions. Larger pools of potentially politically sophisticated citizens vote in highly educated urban areas. This stimulates invalid voting because of citizens’ disaffection with electoral institutions or current politics (Superti Reference Superti2015). The two contradictory predictions are mirrored in contradictory empirical findings. An overall negative association was reported in most studies (Ackaert et al. Reference Ackaert, Wauters and Verlet2011; Cisneros and Freigedo Reference Cisneros and Freigedo2014; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Gendźwiłł Reference Gendźwiłł2015; Herron Reference Herron2011a; Kimball and Kropf Reference Kimball and Kropf2005; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017; Pion Reference Pion2010; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Superti Reference Superti2015), yet several report the opposite (Aldashev and Mastrobuoni Reference Aldashev and Mastrobuoni2013; Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Socia and Brown Reference Socia and Brown2014). The effect of urbanization is context-dependent on other circumstantial factors which define whether associations reflecting the effects of protest or modernization prevail in any given election.

Age

The success and failure ratio of age-related variables is evenly split. While three studies report the hypothesized positive effect (Ackaert et al. Reference Ackaert, Wauters and Verlet2011; Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Socia and Brown Reference Socia and Brown2014), three others report the opposite (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016; Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016). Similar to other socioeconomic variables, two rival explanations have been put forward. One suggests that the elderly are more inclined to commit a voting error, while the other suggests that younger voters have a propensity to protest as critical and unsupportive citizens (Type 2a). Whichever prevails again depends on contextual factors. Additionally, the effect might not be linear but curvilinear (see Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte Reference Dejaeghere and Vanhoutte2016) as both young and elderly citizens may be prone to cast an invalid vote, although for different reasons. Moreover, this variable can also measure some other spatial-structural concepts.

Wealth

A general assumption is that wealthy citizens are less likely to cast a protest-motivated invalid vote because they are generally satisfied and aware of their political efficacy. Moreover, there are mostly congruent theoretical predictions of the reasons why a negative effect of wealth on invalid voting is to be expected. Apart from the wealthier electorates being more politically efficacious and generally more satisfied with the state of the economy, more economically developed countries also have efficient and well-performing bureaucratic apparatuses capable of smooth election administration. Surprisingly, the empirical research gives quite opposite findings. While there are three studies (Pion Reference Pion2010; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995; Socia and Brown Reference Socia and Brown2014) reporting contradictory results to the initial prediction, all the remaining studies (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Cohen Reference Cohen2018; Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016; Pion Reference Pion2010; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007) but one (Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016) show an insignificant relationship with economic development. The conclusion is quite clear: aggregate-level studies report no substantial effect of wealth on invalid voting. Other factors seem to be more important.

Individual-Level Studies

Research based on individual voters’ self-reported decisions to cast invalid votes has been scarce and more recent. We were able to identify only 13 such systematic analyses. Nine of them use single national data sets (Arbache et al. Reference Arbache, Freire and Rodrigues2014; Borba Reference Borba2008; Carlin Reference Carlin2006; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Mariën and Pauwels2009; Katz and Levin Reference Katz and Levin2016; McAllister and White Reference McAllister and White2008; Stiefbold Reference Stiefbold1965), while four exploit the recent availability of cross-national comparative surveys (Cohen Reference Cohen2017; Moral Reference Moral2016; Singh Reference Singh2017; Solvak and Vassil Reference Solvak and Vassil2015). This is an important addition because aggregate-level studies can only imperfectly model relationships that posit individual-level causal mechanisms due to ecological inference problems. The downside of individual-level studies is that self-reported invalid voting does not include possible ballot spoilage by voter error, electoral authority error or electoral fraud – which may create a substantial proportion of invalid ballots. Unlike turnout, the rate of invalid voting is ultimately decided by the electoral bodies, not by individual voters, so their sincere self-reported decision to cast a positive ballot may have been transformed into an invalid ballot biasing any individual-level study inferences.

It therefore comes as no surprise that individual-level studies conclude that most invalid votes are indeed cast intentionally as an expression of discontent (Carlin Reference Carlin2006; Cohen Reference Cohen2017; Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016; Katz and Levin Reference Katz and Levin2016), or as a result of either voter apathy or confusion due to the complex political context (Arbache et al. Reference Arbache, Freire and Rodrigues2014; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014). Unconventional voting stemming from disengagement and distrust of politics is even intensified under compulsory voting laws (Singh Reference Singh2017). A further advantage is that individual-level data allow us to study different motivations for casting invalid ballots. Mihkel Solvak and Kristjan Vassil (2015) show that invalid votes were driven by the lack of perceived political choice and anti-partisan attitudes rather than by anti-EU protest. Another study finds that a complex political offer has a different effect on sophisticated as opposed to unsophisticated voters (Moral Reference Moral2016). When a party system offers a larger set of distinct alternatives, the sophisticated voters are less likely to vote unconventionally and are more likely to support fringe parties.

Individual-level research provides crucial evidence for separating the effects of different causal mechanisms among the three types of voter dissatisfaction. Shane P. Singh (Reference Singh2017) hypothesized that politically knowledgeable and interested people are less motivated to cast an invalid ballot than distrusting citizens with negative feelings towards democracy under compulsory voting. A study of Bolivian judicial elections made an important differentiation between casting blank and null ballots, discerning very different causal structures (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014). Citizens with low information and political skills were more prone to cast a blank ballot while distrustful and opposing citizens intentionally spoiled their ballot as a protest.

Although observational individual-level studies are invaluable for understanding and differentiating between the mechanisms for intentional invalid balloting (in the second quadrant of the classification), they cannot illuminate the processes through which invalid votes arise by voter error. Both types clearly coexist in any given election. This limits the relevance of observational individual-level studies because diverging causal structures of both types of invalid ballots multiply the methodological challenges of separating their proportions and interpreting their causal structure.

The utilization of experimental methods in invalid voting research is situated at the opposite end of this trade-off. While avoiding the ecological inference problem and inferring from individual responses, they typically focus on determinants of ballot invalidation through voter error (Type 1). Experiments have been used in three studies of invalid voting (Ambrus et al. Reference Ambrus, Greiner and Sastro2015; Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar Reference Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar2015; Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017). In a Colombian study subjects were asked to cast their vote under three experimental designs that tested the effect of training and ballot paper design on the probability of an invalid vote, producing mixed results (Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar Reference Beltrán-Oicatá and Sandoval-Escobar2015). Another Colombian study tested the effect of two ballot designs, finding that a simplified ballot substantially reduced the total number of invalid votes (Pachón et al. Reference Pachón, Carroll and Barragán2017). Such findings have direct policy implications for improving ballot design and hence for empowering another part of the electorate that has been excluded from the electoral process.

Qualitative Research

The field is clearly dominated by statistical research, and studies using qualitative evidence are very scarce. This one-sided emphasis on quantitative studies is detrimental to the development of the research agenda. Qualitative evidence is crucial in a number of steps, such as hypothesis generation. Given the causal complexity of invalid voting, researchers need to engage qualitative techniques more frequently. Furthermore, qualitative inquiry should serve as an important device for concept formation. Not only may qualitative archival research uncover historical contexts of ballot invalidation, as in a blank ballot protest against the Czechoslovak communist regime in 1948 (Pehr Reference Pehr2009), but qualitative treatments alert us to the often multiple, shifting and overlapping meanings of casting invalid votes which are not easily captured in the categories used by statistical research. For instance, the use of blank – or Golput (from Golongan Putih or White Group) – votes under the Suharto regime in Indonesia may refer to a person, a movement, an action, an attitude or a behaviour and has had several connotations (such as equating blank ballots with pure-mindedness, which is also expressed by the colour white) (Ananta et al. Reference Ananta, Arifin and Suryadinata2005: 20; King Reference King1994).

Invalid votes in Serbia have been qualitatively interpreted as part of a broader trend in which participants engage in anti-system activities and challenge notions of formal power (Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik Reference Obradović-Wochnik and Wochnik2014). Despite the huge number of parties in that election, voters complained about a lack of real choice and emphasized that parties were virtually indistinguishable. This led to an unprecedented ballot-spoiling campaign using social media platforms. The highest rates were in the wealthiest and most educated urban areas, suggesting that these were unsupportive and dissatisfied voters who had high political efficacy. Such critical citizens (Dalton Reference Dalton2004; Norris Reference Norris1999) protest against corruption, economic stagnation and the inadequacy of the political elites. Qualitative research is especially valuable if it explores mobilization through social movements and political campaigns for ballot invalidation. The importance of such campaigns is demonstrated in a study of 21 Latin American elections, finding that highly publicized and widespread invalid voting has the potential to harm electoral mandates and democratic legitimacy (Cohen Reference Cohen2016).

Explaining the Contradictions

The existing literature has failed to come up with a single general account of invalid voting. While two determinants (compulsory voting and the level of democracy) have a consistent effect, the majority of the literature is characterized by contradictory explanations which militates against establishing a core explanatory theory of invalid voting. The following section aims to provide reasons behind this state of affairs, with the hope that their elucidation will direct future research.

Insensitivity to Context

Our meta-analysis produced starkly inconsistent results for some variables. However, the alternative effect (as opposed to the hypothesized one) was in most cases caused by different socioeconomic or institutional contexts. For example, educational levels and urbanization are negatively associated in democratic and well-developed countries (Fatke and Heinsohn Reference Fatke and Heinsohn2017; Power and Garand Reference Power and Garand2007; Power and Roberts Reference Power and Roberts1995); however, in less democratic ones, there is a positive association with invalid voting (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Cisneros and Freigedo Reference Cisneros and Freigedo2014; Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Galvis and Superti2017; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Herron Reference Herron2011a; Pion Reference Pion2010). Similarly, there are different associations with the age structure. Generally, the error rate rises with voters’ age. However, under certain circumstances the protest of young voters might dominate the election, resulting in contradictory findings (Hill and Rutledge-Prior Reference Hill and Rutledge-Prior2016). Another example is the differential effect of electoral fragmentation under different electoral systems. Under first-past-the-post the fragmentation actually makes elections more important and decisive as each vote matters more (Damore et al. Reference Damore, Waters and Bowler2012). Conversely, under proportional systems electoral fragmentation may lead to a higher incidence of invalid votes. These contradictions can therefore be explained away by some modifying contextual factors by positing interaction effects (see Berry et al. Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012).

Interaction effects in aggregate-level studies also provide indirect tests of individual-level micro-foundations of invalid voting. For example, a modifying effect of the quality of democracy was reported if the incumbent candidate was running in a presidential election, but no such effect was found in fully democratic countries – which is purportedly explained as the voters being motivated by protest (Kouba and Lysek Reference Kouba and Lysek2016). Interaction effects can also be employed in individual-level studies employing hierarchical modelling of higher-level contextual or institutional variables, as performed by Singh (Reference Singh2017: 9), who studied the different effects of compulsory voting in an interaction with several individual characteristics such as a lack of information, level of political distrust and negative orientations towards democracy.

The Problem of Equifinality

Our initial classification predicts four main types of invalid ballots, each being produced by a sharply diverging causal pathway. All may coexist in any given election. This is a situation which set-theoretic methods label equifinality or multiple conjunctural causation: the idea that there are multiple causal paths to the same outcome (Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2006: 236). The presence of equifinality is arguably not a methodological problem per se but becomes one when it is impossible to establish which specific outcomes belong to which causal type. This is the case of invalid ballots.

While aggregate-level regressions may give a reasoned answer as to the prevalence of one or the other causal type of invalid ballots – and in fact such efforts often constitute the principal research questions – rarely is it possible to separate the exact proportions of each type of invalid ballot (or even provide a rough estimate). The problem in most analyses, then, boils down to asking the question: ‘What share of invalid votes is attributable to each one of the categories in our classification?’ This question is crucial but can hardly ever be answered. Invalid voting in a single election results from a number of causes whose empirical manifestations may run counter to each other. If, for instance, one sets the operation of the voter error model against the operation of the dissatisfaction model, such causal conditions as the level of education or interest in politics impact on invalid voting in contrary directions. The multicausal and equifinal nature of invalid voting cautions against straightforward interpretations and policy implications. Some have suggested that spoilt ballots could be used as a straightforward indicator of political disaffection (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014; Moral Reference Moral2016; Solvak and Vassil Reference Solvak and Vassil2015). But taking this general advice runs the risk that ready-made electoral statistics of invalid voting that mix together a hodgepodge of erring voters, critical protesters and disengaged citizens will be interpreted wrongly.

Omitting Agency-Centred Explanations

While structural determinants are clearly important explanations of invalid voting, conjunctural causes constituted by specific political actors for a limited time period are also relevant. We suspect that many contradictions in current research could be explained away by focusing on whether invalid voting is instrumentalized in the public discourse as a politically relevant act by identifiable political actors. Such agency-centred explanations can be distinguished using the type of actors as a criterion – that is, whether invalid voting is promoted by social movements channelling dissatisfaction or by political parties.

Some elections are accompanied by social movements mobilizing for a deliberate annulment of ballots. This was the case in the 2016 referendum in Hungary, where an originally satirical movement – the Two-Tailed Dog Party – provided a common identity for voters wanting to actively express their disapproval in the face of the opposition’s disunity and lack of clear message (Gessler Reference Gessler2017: 90). Similar mobilizations are often limited to a single election, as in the Argentine elections of 2001 where 22 per cent of voters cast a blank or null ballot. Past voters for the collapsed centre-right party bloc especially signalled their anti-elite protest this way in the midst of a severe economic and political crisis (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2008: 26). Such examples underscore the need to incorporate social movements into explanations of invalid voting as an intentional protest (Type 2a in our classification). This reflects a broader call for a dialogue between the election studies and social movement studies literatures, both of which have failed to appreciate the connection between elections and social movements – the two major forms of political conflict in democracies (McAdam and Tarrow Reference McAdam and Tarrow2010: 532). Several mechanisms are relevant for explaining the linkages between conventional political actors and social movements (McAdam and Tarrow Reference McAdam and Tarrow2010: 533) but perhaps the crucial one for ballot invalidation concerns the choice of this particular type of innovative collective action. Such a focus on specific political actors is almost entirely absent from the quantitative literature on invalid voting (but see Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2014). This highlights the need for qualitative treatments.

Political parties are unlikely agents of ballot invalidation mobilization because their fortunes are predicated on receiving valid votes. Moreover, because social movements, unlike political parties, are free to use innovative methods of contentious collective action (McAdam and Tarrow Reference McAdam and Tarrow2010: 532), parties are seldom thought of as mobilizing agents for ballot invalidation. Yet they have advocated the use of invalid ballots, especially when facing an unlevel playing field or outright abolition. An exceptionally high rate of null votes relative to both prior and later elections occurred in the 2009 elections to the Basque Parliament after the prohibited party Batasuna called on its supporters to cast a null vote and 5.7 per cent of the electorate did so (Ibarzabal and Laruelle Reference Ibarzabal and Laruelle2018: 355). Instructing voters to use blank ballots has been an even more frequently used strategy for some parties in semi-competitive elections. Juan Perón, for example, ordered his Peronista followers to cast blank ballots in the 1957 and 1960 elections – one quarter of all ballots were cast as blank on both occasions (Snow Reference Snow1965: 3).

Failing to include agency-centred variables in models of invalid voting may result in omitted variables bias and underspecified models. A study of the 2009 Mexican elections showed that in regions where the anulista movement campaigned for ballot invalidation, the relationship between education levels and invalid voting rates was positive, but negative where such mobilization did not occur (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2013: 65). Such interactions provide evidence for the different reasons (captured by our typology) for ballot invalidation taking place at the same time in any given election. Ultimately, the omission of agency goes far in explaining some of the contradictions in existing research on invalid voting.

Conclusion

The results of a meta-analysis of all aggregate-level empirical studies indicate that several theoretically important variables are significantly related to invalid voting. The strongest institutional determinant is compulsory voting, whose effect may be enhanced or inhibited by other factors, such as political competition, political trust or discontent. Research on invalid votes importantly shows that compulsory voting is not a panacea for declining electoral participation. Another lesson learned is that invalid votes are more widespread in less democratic regimes or authoritarian states. Additionally, it seems that some of the political variables (especially electoral fragmentation and closeness of elections) found to be negatively associated with electoral turnout are positively correlated with invalid votes for the same reasons.

On the other hand, our findings echo those made with respect to a recent review and meta-analysis of turnout which emphasized that there is no established core model of electoral turnout and that the effects of different variables are highly context-dependent (Stockemer Reference Stockemer2017: 712). We wish to emphasize the same conclusion with respect to the invalid voting literature. This means that researchers should be aware of the multidimensional origins of invalid voting and should not prematurely rule out alternative explanations. Moreover, different reasons for invalid votes very likely coexist at the same time in most elections. There are voters committing accidental errors as well as apathetic or alienated voters intentionally spoiling their ballots. Which reasons prevail depends on socioeconomic, institutional or conjunctural contexts.

Revealing the heavily context-dependent and equifinal nature of invalid voting has important methodological implications. The most widely used method – multiple regression – is not an optimal tool for understanding the causal structure of invalid voting. Non-significant results on a variable do not necessarily mean the absence of an effect but may be a result of two counteracting causal forces cancelling each other out. Positing interactions is a possible fix. Furthermore, the problem of equifinality reduces the utility of individual-level analyses because these cannot distinguish the proportion of each type of invalidated ballot. All this alerts us to the importance of agency-centred explanations as opposed to the purely structural arguments that prevail in the existing statistical research. Recognizing the role of agency in promoting invalid voting entails an increased sensitivity to the context, the often-episodic nature of invalid voting campaigns and its nature as a form of contentious politics in the midst of the crisis of representative politics.

Acknowledgements

Karel Kouba was supported by a research grant of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Hradec Kralove. Jakub Lysek was supported by a research grant of the Philosophical Faculty of the Palacky University Olomouc.