Both the party-state and general public widely acknowledge that there is rampant corruption in China. Corruption has permeated all public sectors of the country, breeding strong resentment among the general populace and undermining the legitimacy of the Party.Footnote 1 However, China does not seem to have fared particularly worse than comparable countries in terms of the degree of corruption. For instance, according to the Corruption Perceptions Index released by Transparency International, China has consistently scored higher than other comparable countries in recent years: in 2012, China scored 39, higher than India (36), Indonesia (32), Vietnam (31), and Russia (28).Footnote 2 Over the years, the Chinese party-state has punished a large number of corrupt officials, including high-ranking leaders. From 2000 to 2005, for instance, more than 200,000 corrupt public employees were disciplined, and some were executed.Footnote 3 The various measures taken by corrupt agents to avoid punishment indicate that the punishment meted out by the state to corrupt officials retains a certain degree of credibility.

The mixed picture of anti-corruption measures in China is related to the approach employed by the Party authority. Effective anti-corruption is highly conditional. As Susan Rose-Ackerman writes, the “deterrence of criminal behavior depends on the probability of detection and punishment and on the penalties imposed – both those imposed by the legal system and more subtle costs such as loss of reputation or shame.”Footnote 4 In other words, the timely investigation of corrupt agents and the meting out of appropriate punishment are crucial for effectively curbing corruption and enhancing the government's anti-corruption reputation. In authoritarian regimes, the anti-corruption efforts of the government can be compromised because of its political calculations, which compound efforts to detect and discipline corrupt agents. Authoritarian governments rely on their agents for political support and policy implementation, and punishing corrupt officials is costly owing to a variety of considerations, including faction politics, patron–client relations, and the reliance of the state on agents for governance. However, exempting corrupt officials only encourages more corruption. Therefore, the state authority needs to strike a balance between tolerating and punishing corrupt agents.

This paper explores how the Chinese party-state seeks to balance the cost of punishment with the need to curb corruption. It focuses on how the Party has attempted to enhance its credibility in terms of routing out corruption by examining the punitive measures it takes against those officials convicted of crimes. Punishing convicted officials has important implications for anti-corruption efforts because it demonstrates to others the consequences of being caught. This study reports that when the Chinese party-state is unable or unwilling to uncover more high-ranking corrupt officials, it tends to punish those who have been caught and convicted more harshly. The party-state hopes to demonstrate its political will to clamp down on corruption by showcasing severe punishment for high-ranking officials.

Rationale for Punishing Corrupt Officials

Authoritarian governments face a dilemma when disciplining malfeasant agents, including corrupt agents.Footnote 5 On the one hand, the need for punishment is evident: tolerating corrupt officials only encourages more corruption, which undermines both the authority and legitimacy of the state. The malfeasance of government officials weakens the trust of citizens in their regimeFootnote 6 and provides the pretexts for opposition forces to incite anti-government sentiments.Footnote 7 In 1989, for instance, the students in China used the issue of corruption to appeal to and mobilize their fellow citizens, legitimize a demonstration, and support the call for political reform and democracy.Footnote 8 On the other hand, punishing corrupt officials can be costly. In an organizational setting, the use of discipline may demoralize disciplined agents and cause agents to cease their support for the agency. Disciplined agents may exhibit anxiety and aggressive acts or feelings towards the punishing agent.Footnote 9 Depressed agents may reduce their productivity and contribution to the organization.

The government incurs similar costs when it punishes corrupt officials. When sanctions upset the agents, it is better to emphasize the role of education when tackling corruption.Footnote 10 Groenendijk argues that when the authority confronts corrupt agents, it has to minimize not only the harm but also the cost of addressing corruption.Footnote 11 The authority needs to determine the extent to which corruption will be reduced, the costliness of the policy, and the worth of the reduction, compared to the direct and indirect costs of anti-corruption policies. An anti-corruption campaign should not be pushed so far that its costs outweigh the benefits, because it is not the sole outcome sought by the authority.

In authoritarian regimes, the government does not rely on electoral support to stay in power and to rule. Instead, it relies on its agents for governance and political support. Considering that corruption is a crime, an official can no longer maintain a position of authority if he or she is convicted. In other words, the investment of the state in the official will be wasted. In China, the state authority acknowledges that the adoption of anti-corruption measures is to maintain the well-being of the Party's organs, and meting out punishment is not the ultimate purpose. The state authority must rely mainly on education to deal with the majority of cadres who have common problems: “It is not easy for a person to become a cadre or for the Party to train a cadre. The Party cannot turn a person into an official overnight. Instead, it takes much time, money, and energy to do so.”Footnote 12

Naturally, the costs are higher when the government punishes high-ranking officials; however, tolerating corrupt high-ranking officials is more damaging to the anti-corruption efforts of the Party. As a result, the Party's approach to dealing with corrupt high-ranking officials can better reveal its strategy for curbing corruption.Footnote 13

Dealing with corrupt high-ranking officials

In China, similar to elsewhere, more resources and time are generally required to train high-ranking officials. My data suggest that it generally takes 27 years for a person to be promoted to prefecture Party secretary, while it takes 26 years to be mayor, and 36 years to reach provincial Party secretary or governor status.Footnote 14 Moreover, high-ranking officials are very likely to have contributed to the Party and state previously and form the key personnel of the state. Therefore, they have accumulated more of what Hollander terms as “idiosyncrasy credits;” that is, “an accumulation of positively disposed impressions residing in the perceptions of relevant others; it is … the degree to which an individual may deviate from the common expectancies of the group.”Footnote 15 The deviations of high-status people with more idiosyncrasy credits may be tolerated more than those of others within their organizations.

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials administer various types of discipline based on the seriousness of the malfeasance: (1) Party discipline; (2) administrative discipline; (3) organizational discipline; and (4) legal punishment. The severity of the discipline varies from inner-Party warnings to the death penalty. Legal punishment is meted out when an official commits a criminal offence and the other types of discipline are inadequate to deal with a crime of that level.Footnote 16 Party discipline is executed by the Party's Discipline Inspection Commission (DIC). Limited by the available data, this study mainly focuses on cases which have received legal punishment.

Existing evidence seems to suggest that corrupt high-ranking officials are less likely to be detected and/or investigated. First, corrupt high-ranking officials tend to have a longer period of latency (that is, the time span between when an official commits their first act of corruption and when they are detected). Yong Guo and Andrew Wedeman both use the latency period of corruption as an indicator to approximate the likelihood of an official being caught.Footnote 17 Following this approach, I use data collected from the Procuratorial Daily (Jiancha ribao 检察日报, see below) to construct both the latency period and the investigation period, which is the time span from when the investigation begins to when a suspect is initially tried in court. Figure 1 shows that both the latency and investigation periods increase along with the rank of the official.

Figure 1: Latency Period of Officials of Different Ranks

Other types of statistics likewise suggest that high-ranking officials are less likely to be investigated and punished by the Party disciplining institution or to receive legal punishment. For example, nationwide in 1996, only 2.5 per cent of the cases concerning high-ranking officials (i.e. at the administrative level of county magistrate or higher) who were accused of corruption and reported (jubao 举报) to the DIC were investigated by the DIC, compared with 10.7 per cent of cases concerning lower-ranking officials. Therefore, although reports of corruption involving high-ranking officials accounted for 16.6 per cent of the total cases reported, cases involving high-ranking officials only accounted for 4.4 per cent of the total cases investigated.Footnote 18 In Liaoning province from 1994 to 2000, the DIC disciplined approximately 7 per cent of the Party members (including officials and non-officials) whose wrongdoings were reported. However, a variation was presented across officials of different ranks. Roughly 16 per cent of the Party members who did not hold administrative positions were punished. Meanwhile, of those who were disciplined and received punishment, 9 per cent were ordinary cadres, approximately 5 per cent were officials at the level of township head, 3 per cent were officials at the administrative level of county head, and less than 1 per cent were officials at the administrative rank of city mayor or higher.Footnote 19 Moreover, high-ranking officials may be less likely to face legal punishment after their cases are filed (li'an 立案) by the Procuratorate. According to the Procuratorate's annual report, of the cases filed by procuratorates against officials between 1993 and 2006, approximately 55 per cent of ordinary officials were criminally penalized, as opposed to 23.5 per cent of senior officials at the administrative rank of county magistrate or higher.Footnote 20

When asked about the cause of the rampant corruption in China during an interview, an official of a city discipline inspection committee responded that “high-ranking officials are corrupt.” The challenge faced by the party-state is that its credibility when dealing with corruption is determined by the resolve it demonstrates in detecting and punishing corrupt officials, especially high-ranking officials. Therefore, an important issue the Chinese party-state has to address in terms of tackling corruption is how to deal with corrupt high-ranking officials.

This paper shows that when the party-state is unable or unwilling to uncover more corrupt high-ranking officials, it must severely punish those high-ranking officials who are convicted if it still hopes to contain corruption. In China, corrupt high-ranking officials are directly investigated by the central or provincial authority. The central government demonstrates its determination to curb corruption to lower-level government officials and the public by severely punishing convicted officials. Tolerating high-ranking officials results in the “leakage of authority” at the lower levels of the hierarchy. In Inside Bureaucracy, Anthony Downs explains how the leakage of authority occurs as orders pass through the levels of a political hierarchy: official A issues an order to B, but B's own goals indicate that his commands to his subordinate C should encompass only 90 per cent of what he believes official A actually has in mind. If C thinks in the same manner, by the time A's order reaches officials at level D, these officials will receive commands that encompass only 81 per cent (90 per cent of 90 per cent) of what A really intends.Footnote 21 Such leakages cumulate when several levels are involved, which can drastically impact the effectiveness of orders issued by top-level officials.Footnote 22 In agent management, the leakage of authority results in the unprincipled tolerance of erring agents at lower levels.

To maximize the effect of punishing high-ranking officials, the government likewise chooses to publicize such cases and make them high profile. Research on crime deterrence suggests that highly publicized executions can significantly reduce homicide cases.Footnote 23 As Pogarsky suggests, “The formation of the threat perception is central to deterrence and to the society's ability in deterrence-oriented criminal control.”Footnote 24 Therefore, when a case attracts considerable public attention, authorities are more likely to impose a severe punishment, sometimes to meet the expectations of the public.Footnote 25 In China, the investigation and punishment of high-ranking officials are generally given a high profile by the media upon the instruction or encouragement of the state authorities.

The Chinese party-state's strategy of severely punishing high-ranking officials is indicative of its need to balance the punishment against the cost involved. Although this method of selective punishment compromises the value of the punishment as a deterrent, it still creates uncertainty for state agents in the country.

Data

Researchers of corruption inevitably encounter the issue of whether the data used are accurate or representative. Survey data on corruption generally measure the perceptions of people instead of actual occurrences of corruption. Data released by the government on corruption cases contain biases that arise from the censored disclosure of sensitive information; however, the public can only access information on corrupt agents through government-sanctioned sources. This study attempts to reduce the biases inherent in the government data used in this research by collecting the data in a more systematic manner.

The Central Discipline Inspection Commission (Zhongyang jilü jiancha weiyuanhui 中央纪律检查委员会) (CDIC) and the Supreme Procuratorate both publish newspapers: News of China's Discipline Inspection and Supervision (Zhongguo jijian jiancha bao 中国纪检监察报) and Procuratorial Daily. However, the CDIC's newspaper, News of China's Discipline Inspection and Supervision, does not publicize corruption cases regularly and is not a good source for systematic data on corruption. In contrast, the Procuratorial Daily regularly reports on corruption cases and serves as an accessible source of systematic data on corruption. This study is based on the cases reported in this newspaper from 1993 to 2010.

According to Chinese criminal law, an act is defined as corrupt if it involves (1) accepting or giving bribes; (2) embezzlement; (3) misappropriation; (4) failure to explain the sources of a large amount of income; (5) concealment of deposits abroad; (6) dividing state-owned assets; and (7) dividing confiscated property. For the purposes of the research for this paper, the criterion for including a case is whether a suspect is convicted of any of these crimes. Moreover, considering that this study focuses on the punishment of corrupt officials, the data includes only civil servants and excludes staff members working in non-administrative public institutions and state-owned enterprises. Finally, since this study is concerned with legal punishment results, it only includes cases that receive criminal sanctions; cases which were still “under investigation” at the end of 2010 have been dropped.

Based on the above criteria, 2,946 cases were recorded, more than 80 per cent of which occurred after 2000. The data apparently suggest that there were more corruption cases in some central provinces, such as Anhui, Henan and Hubei, and a few others in the east, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, than in north-western provinces such as Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Qinghai. The data are only suggestive of the potential difference in frequency across provinces.

This dataset covers the corruption cases that resulted in criminal penalties. Thus, this paper only studies a portion of corruption cases, and does not investigate those cases resulting in Party or organizational discipline. Also, all the cases in the dataset come from the Procuratorial Daily. Corruption cases not reported on by this newspaper do not form part of this study. Needless to say, the limited availability of data means that the findings in this study are explorative rather than conclusive.

Empirical Analysis

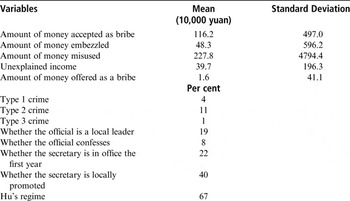

As elsewhere, the punishment for a corrupt official in China is generally determined by the severity of his or her corruption, which is often measured by the amount of money involved. In China, legal punishment for a convicted official ranges from a fixed term of imprisonment to the death penalty. My purpose is to examine the factors that affect the severity of the punishment imposed on convicted officials. Therefore, the dependent variable in the analysis is the type of punishment. The modes or types of punishment are divided into the following categories from less to more severe: (1) a fixed term of imprisonment; (2) life imprisonment; (3) the death penalty with reprieve; and (4) the death penalty. For analytical purposes, the latter three are treated as severe punishments. In our data, 2,429 cases have information on the legal punishment meted out to convicted officials. Table 1 shows that most convicted officials (83 per cent) were given a fixed term of imprisonment.

Table 1: Types of Punishment

Source:

Procuratorial Daily 1993–2010.

Independent variable

This study aims to examine the attitude of the government towards high-ranking corrupt officials. Thus, it focuses on the relationship between the severity of the punishment issued and the administrative rank of a convicted official. According to Chinese civil service laws, there are 11 categories of administrative ranks for civil servants. Such categories range from staff and clerk (the lowest) to national leaders (the highest). The data collected show the number of corrupt officials in the top three ranks to be very small, and they are therefore included in the administrative rank category of “vice-governor (fu bu ji 副处级) or higher.” Thus, in my analysis, officials are divided into eight categories (see Table 2). Of the 2,854 officials in the data with information about their ranks, those at the administrative rank of township head (ke ji 科级) or lower account for approximately 42 per cent of convicted officials, whereas officials at the administrative rank of vice-governor or higher constitute less than 3 per cent.

Table 2: Distribution of Officials by Rank

Source:

Author's data collected from the Procuratorial Daily 1993–2010.

Control variables

In the empirical analysis, four sets of control variables are included. First, the type and the magnitude of corruption are controlled for because the degree of punishment for a corrupt agent is tied to the amount of money involved. In addition, according to Chinese criminal law, bribery and embezzlement are more serious crimes than others, such as misappropriation, giving bribes and failing to explain the sources of a large amount of income. Thus, the empirical analysis includes both the type of corruption and its magnitude in terms of the amount of money involved in each type of corruption.

Some officials may have also committed other crimes that can be divided into three types. Type 1 crimes include dereliction of duty, abuse of power, and violating laws for personal gain. Type 2 crimes include introducing bribery and dividing public property. Type 3 crimes include sheltering criminals and illegally keeping guns.

A second set of control variables includes the attitudes or attributes of corrupt officials. They include (1) whether the corrupt official offers concessions, and (2) whether the official is the major local leader (i.e. the Party secretary or the head of the government). According to the pertinent laws and government regulations, corrupt officials who cooperate or confess may receive a reduced punishment. It is assumed that major local leaders will receive a more severe punishment than other officials who have the same administrative rank but who do not assume a position as important as that of local leader. This is because punishing high-profile leaders can produce a stronger deterrent effect.

A third set of variables includes the investigating official's career information. One variable involves the career of the provincial secretary. A person in the first year of his or her term in office is assumed to have a higher level of determination in terms of anti-corruption efforts because he or she needs to perform well. If this person has been promoted locally, he or she is likewise assumed to be less willing to issue harsh punishments to local corrupt officials because of local connections. I also differentiate if the cases occur under Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 or Jiang Zemin's 江泽民 regime. Finally, all the models include the time trend. Table 3 summarizes the variables used in the statistical analysis.

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics of Control Variables (N = 2377)

Source:

Author's data collected from the Procuratorial Daily 1993–2010.

Model and results

This study aims to examine how the party-state punishes high-ranking officials. Prior to conducting the statistical analysis, data is presented on the punishment of officials from different ranks. The punishments are divided into the aforementioned four categories, namely, a fixed term of imprisonment, life imprisonment, the death penalty with reprieve, and the death penalty. Figure 2 shows that fewer high-ranking officials were given a fixed term of imprisonment; instead, more high-ranking officials were given one of the three types of severe punishment. Officials with the highest rank (i.e. vice-governor or higher) were more likely to be given severe punishments.

Figure 2: Distribution of Penalties Imposed on Officials of Different Ranks (N = 2,377)

The relationship between the severity of punishment and the rank of a corrupt official presented in Figure 2 is constructed without controlling for other variables, and the proposed relationship may be superficial or inaccurate. According to criminal law, corrupt activities are punished mainly according to the type and magnitude of corruption. High-ranking officials are more likely to be involved in serious corruption. Therefore, a statistical analysis is conducted by controlling for the variables discussed above, especially the type and magnitude of corrupt activities. Considering that the dependent variable is an ordinal categorical variable, an ordered logit model is employed to estimate the effect of administrative rank on the severity of penalty imposed on officials.

The statistical results are reported in Table 4. In Model 1, the rank of the corrupt official is treated as a continuous variable while controlling for the magnitude of corruption. Although a positive relationship exists between rank and the severity of penalty, the relationship is not statistically significant. When the rank of the corrupt official is treated as a categorical variable (the model is not shown), the effect of rank on degree of punishment is not linear. Therefore, a quadratic term of rank is included to estimate the non-linear relationship between the rank of the corrupt official and the severity of penalty in Model 2. The statistical outcomes indicate that both rank and its quadratic item significantly affect the severity of the penalty but in a non-linear manner. Specifically, the first order of rank is negatively associated with the severity of the penalty. Thus, the probability of receiving a more severe punishment decreases first as the rank of the corrupt official increases. The probability of receiving a more severe penalty is lowest when the administrative rank is county magistrate (i.e. chu ji 处级, coded as 5). Among the officials whose administrative rank is at the level of county magistrate or higher, the probability of receiving a harsher punishment increases as the rank of the corrupt official becomes higher. The increase in probability accelerates as the rank becomes higher.

Table 4: Ordered Logit Model of Severity of Punishment on Official's Rank

Notes:

Standard errors in parentheses; * p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In Models 3 and 4, more control variables are included, and the effect of rank on the severity of penalty does not change significantly. The control variables, except for the seriousness of the crime, have no significant effect on the severity of the penalty. The magnitude of corruption increases the probability ratio of being more severely punished. For instance, as shown in Model 4, the expected probability of receiving a harsher punishment increases by 1.83 (e1.043−1 = 1.83) when the amount of money accepted as a bribe increases by 1 per cent. Corrupt officials who commit other crimes are much more likely (five times more) to be severely punished than those who do not. The effect of the time trend is significantly negative, suggesting that the probability of receiving a severe penalty decreases by 0.234 (1−e−0.266 = 0.234) each year.

To understand the non-linear relationship between the rank of the corrupt official and the severity of the imposed penalty better, Figure 3 presents the predicted probability of the punishment for officials of different ranks. In this analysis, several specifications apply to the values of control variables. An official is convicted of corruption in 2004. They are assumed to have received a bribe amounting to 1 million yuan but to have committed no other crimes, and they are likewise assumed not to be local leaders or to have confessed. In addition, the provincial secretary is neither in the first year of office nor locally promoted.

Figure 3: Predicted Probability of Imposing Different Types of Penalties on Officials of Different Ranks

The probability of receiving a “fixed term of imprisonment,” which is the lightest penalty, is roughly 0.42 for staff or clerks. It increases to approximately 0.75 when the rank of the official is upgraded to deputy county magistrate, and then decreases to 0.46 when the rank reaches vice-governor or higher. In terms of the severity of the punishment, compared to officials at the rank of deputy county head, officials at the lowest and highest ranks are both more likely to receive a severe punishment. For instance, the probability of staff or clerks receiving the death penalty is 0.049 higher than it is for officials at the level of county magistrate, and the probability of officials at vice-governor rank or above receiving the death penalty is also 0.039 higher than it is for officials at the level of county magistrate.

This pattern shows that the state authority tends to issue stronger punishments to corrupt officials who are of a higher ranking (i.e. on the right side of the U-shape curve) to strengthen the deterrent effect. In addition, lowest-ranking officials are likely to be severely punished (i.e. on the left end of the U-shape curve), perhaps because to do so is less costly. Officials at the rank of county magistrate are less likely to be given a severe penalty compared with these two groups. What can be the rationale behind this U-shape distribution? The following section analyses this pattern by examining the political considerations on the part of the party-state.

State authorities and disparate incentive structures

In China, state authorities at different levels investigate corrupt officials of different ranks. According to the Party's “Regulations on handling violations of Party discipline,” a malfeasant Party member is to be investigated by the discipline inspection committee of the next level up.Footnote 26 Therefore, the provincial or central authority investigates officials at the administrative rank of prefecture mayor or higher, and authorities at the city level or lower investigate officials at the administrative rank of county magistrate or lower. State authorities at different levels have different considerations when dealing with corrupt agents.

Anti-corruption efforts are tied to the legitimacy of the party-state, but legitimacy is of varying importance to state authorities at different levels. In China, the central government is more responsible for the operation of the political system and by and large represents the regime. Thus, it has a greater interest in protecting the legitimacy of the regime. In contrast, local officials are more concerned with policy implementation or task fulfilment and local issues – legitimacy is not their primary concern.Footnote 27 Therefore, compared with central or provincial authorities, lower-level local authorities have less motivation to issue stringent penalties to corrupt officials in order to produce a deterrent effect.

Nevertheless, if local leaders are more tolerant of corrupt officials, why have some local officials been severely punished (i.e. at the left end of the U-shape curve)? One possible explanation is that the connections these officials have with local leaders may vary, and the willingness of local leaders to protect officials of different administrative ranks likewise varies. Officials at the lowest level generally have fewer political resources than high-level officials. Consequently, if low-ranking officials are very corrupt, local leaders may not be strongly motivated to offer protection. Corrupt officials are sometimes caught and punished because they lack connections, and the severity of sentences inversely varies with hierarchical position.Footnote 28

The different incentive structures of state authorities at different levels affect their attitudes towards corrupt officials. Of the nearly 2,900 cases in the dataset, 1,308 provided information on the level of the agency responsible for investigating the reported corruption. Of these cases, approximately 38 per cent were investigated by county-level agencies, roughly 69 per cent were investigated by prefecture-level agencies, 26.5 per cent were investigated by provincial-level agencies, and 4.5 per cent were investigated by central agencies. For analytical convenience, investigative agencies are divided into two categories, namely, agencies at the provincial level and higher, and agencies at the prefecture level or lower. Table 5 shows officials of different ranks and the corresponding investigation agencies. It reveals that lower-ranking officials are mostly investigated by lower-level agencies, whereas the majority of officials at the level of deputy prefecture mayor were investigated by provincial or central agencies. The provincial or central DIC sometimes becomes involved in the investigation of low-ranking officials when the case is complex or involves other high-ranking officials. Very few high-ranking officials are initially subject to investigation by lower-level agencies, but lower-level agencies can receive the authority to investigate higher-ranking officials if those officials are involved in crimes with low-level cadres.

Table 5: Agencies Responsible for the Investigation of Corrupt Officials

Source:

Author's data collected from the Procuratorate Daily 1993–2010.

In China, once the state authorities have decided to investigate corrupt agents, especially important officials, they have usually already gathered evidence. Consequently, officials under investigation are very likely to be convicted. When a discipline inspection committee decides or is allowed to investigate a person, it forms a team and then adopts the so-called shuang gui 双规 (double designation) approach This means that the detained cadre is required to report to a designated place at a designated time for questioning. Once a provincial or central state agency investigates a high-ranking official, it is likely that that official will receive a severe punishment if he or she is convicted.

The following statistical analysis demonstrates the intention of provincial and central authorities to punish high-ranking officials in order to showcase their determination to crack down on corruption. Table 6 shows the statistical results. In Model 1, the dummy variable of whether the case is investigated by a provincial or central agency is included. Holding others constant, if an official is investigated by the provincial or central agency, the probability of them being severely punished is approximately 82 per cent (=e0.597−1) higher than for an official who is investigated by an agency below the provincial level.

Table 6: Effect of the Level of Investigation Agency on Punishment

Notes:

Standard errors in parentheses; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In Model 2, an interaction term between the rank of a corrupt official and the level of supervisory agencies is introduced. The statistical result indicates that the effect of rank expectedly changes with the change in the level of investigating agencies. In cases investigated by agencies below the provincial level, the probability of an official receiving a more severe penalty decreases by 0.492 (=1−e−0.678) per rank. In contrast, in the cases investigated by agencies at the provincial or central level, when the rank rises by one level, the probability of receiving a more severe penalty increases by 1.65 (e0.975−1).

A number of cases involving high-ranking officials who received severe punishments have been reported. During the 25 years preceding 2012, authorities from the central Party disciplined approximately 100 officials at the administrative level of vice-governor or higher. Among the 90 officials who were legally punished, 6 were sentenced to death, 26 were sentenced to death with reprieve, another 16 were sentenced to life imprisonment, and the remaining 42 received fixed-term prison sentences.Footnote 29 For instance, Liu Fangren 刘方仁, a former provincial Party secretary of Guizhou, was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2004 for accepting a bribe of 6.77 million yuan. In 2005, Tian Fengshan 田凤山, a former minister of land and resources, received the same sentence for receiving a bribe of 4 million yuan. Other officials given the same level of punishment include heads of provincial government agencies and prefecture leaders.

Officials given the death penalty with reprieve, which means that execution is commuted, include Li Jiating 李嘉廷, a former governor of Yunnan, who was found guilty in 2003 of taking 18.1 million yuan in bribes, and Cong Fukui 丛福奎, a vice-governor of Hebei, who was sentenced in 2002 for accepting bribes amounting to 9.36 million yuan. Li Jizhou 李纪周, a former vice-minister of the Ministry of Public Security, was also sentenced to death with reprieve in 2001 for taking 5.03 million yuan in bribes. Many other high-ranking local leaders received this sentence for similar misdemeanours.

There have been some high-ranking officials who have been executed, although the number has decreased in recent years. Zheng Xiaoyu 郑筱萸, the former head of the National Food and Drug Agency, was executed in 2007 for accepting bribes amounting to 6.49 million yuan and because the corruption in his agency distorted the Chinese drug market and angered the central government. Cheng Kejie 成克杰, a former vice-chairman of the National People's Congress, was executed in 2000 for taking 41.09 million yuan in bribes. Hu Changqin 胡长清, a vice-governor of Jiangxi, and Wang Huaizhong 王怀忠, a vice-governor of Anhui, were executed in 2000 and 2003, respectively, for corruption.

Although it is the central authority's intention to curb corruption by punishing corrupt high-ranking officials, inconsistencies have been observed in the disciplining of government officials at both the central and local levels. The statistical pattern that indicates that corrupt high-ranking officials are more likely to be severely punished differs from public perception, largely owing to these inconsistencies. For instance, Cheng Weigao 程维高, the former provincial Party secretary of Hebei Province, accepted bribes, protected corrupt subordinates, illegally created business opportunities for his family, and forced the local legal department to put the person who reported his corruption into a labour camp for two years. When finally punished, Cheng was exempted from criminal charges and was instead merely expelled from the Party.Footnote 30

The high-profile corruption cases of top officials naturally catch the attention of both the general public and officials alike. These high-profile cases tend to have a disproportionately significant impact on the perceptions of people and officials regarding the attitudes of the state towards corruption. Inconsistencies in the punitive measures dished out to corrupt agents not only undermine the credibility of the punishmentsFootnote 31 but also give rise to scepticism about the determination or motivations of the central authority. Erratic sentencing leads people to believe that anti-corruption efforts and the punishment of high-ranking officials are the result of political power struggles at the top rather than evidence of the determination of the central authority to clamp down on corruption. For example, in a case similar to that of Bo Xilai's 薄熙来 fall from grace, some people, including local officials, view the imprisonment of former Shanghai Party secretary, Chen Liangyu 陈良宇, as a consequence of his political defeat in a power struggle leading up to the 17th Party Congress.Footnote 32

Robustness of results

The previous results find a U-shape relationship between the rank of corrupt officials and the severity of criminal penalty they receive. Because these findings are explorative, I conduct additional robustness tests to increase confidence in the results.Footnote 33

The first robustness check is to re-categorize the dependent variable, the type of criminal penalty. Previously, I categorized criminal penalties into four types: fixed term of imprisonment, life imprisonment, the death penalty with reprieve, and the death penalty. Now I will re-categorize “fixed term of imprisonment” into types: less than ten years' imprisonment, and ten years' or more imprisonment. According to Chinese criminal law, serious corrupt activities receive a prison sentence of ten years or more.Footnote 34 The average fixed-term prison sentence in the data is 9.14 years. Therefore, the new dependent variable has five types. I conduct an ordinary logistic model to examine whether the effect of rank on punishment depends on how many categories the dependent variable has. As Model 1 in Table 7 indicates, the U-shape relationship between official rank and severity of punishment remains when categorizing the dependent variable into five types.

Table 7: Robustness of Results: Ordered Logit Model of Criminal Penalty on Selected Independent Variables

Notes:

Standard errors in parentheses; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The pattern of punishing corrupt officials is also vulnerable to the systematic selection bias of the dataset. In particular, it is possible that cases where low-ranking officials receive the death penalty are not systematically covered by the newspaper, since the Chinese government most likely prefers to lower the profile of death penalty cases. If this is the case, the argument that the high-ranking officials receive harsher sentencing could be spurious. I conducted a model excluding death penalty cases to examine the possible impact from the selection bias of the dataset. As indicated in Model 2 in Table 7, I confirm that the effect of rank on penalty does not change when death penalty cases are excluded, except for a slight increase of coefficients.

I perform two additional tests of the findings to examine other possible explanations for the harsh punitive measures for high-ranking officials. In the first, I test the other possible explanation that high-ranking officials are severely punished as a consequence of political power struggles. To examine the effect of a power struggle, I investigate the disciplining of corruption in the year before or after the change of the central regime. In the dataset, the central regime changed only in 2003. Therefore, cases judged in 2002 or 2003, especially those involving high-ranking officials, are expected to be severely punished. Model 3 in Table 7 reports the results. There is no statistically significant difference in punishment levels for cases in normal years and those in the years before or after the central leadership changes. Furthermore, the effect of rank on severity of punishment is also not significantly enhanced in 2002 or 2003. These findings indicate that a power struggle could matter, but it does not systematically affect the severity of punishment.

Finally, I consider the effect of social pressure on the punishment meted out to officials. Given the same type and amount of corruption, high-ranking officials are more likely to have a higher profile and generate worse social impacts than low-ranking officials. In China, the widespread use of the internet, especially Weibo (a twitter-like microblog which was launched in 2007), provides a forum for the public to follow and discuss these cases. Thus, high-ranking officials may receive harsher sentences because the public condemns them more severely. To examine the effect of social pressure from the internet on the sentencing of corrupt officials, I use the year 2007, when Weibo was launched, to proxy the increased social pressure to punish corrupt officials harshly. Moreover, I use an interaction term of social pressure and rank, and the quadratic of rank. Corruption exposed in or after 2007, especially if it involves high-ranking officials, is expected to be more severely punished if the hypothesis of social pressure is supported. Model 4 in Table 7 reports the results. It indicates that there is no statistical evidence supporting the effect of social pressure, which is consistent with existing research.Footnote 35

Conclusion

The ability and willingness of the government to expose corrupt agents in a timely manner and impose appropriate punishments are fundamental to successfully curbing corruption. In other words, the government can increase the cost of committing crimes by reducing the uncertainty of being caught and increasing the severity of the punishment.Footnote 36 Authoritarian governments face little electoral pressure and so are less accountable to the public in terms of their anti-corruption efforts; however, punishing their own corrupt agents can be costly. When the government is unable or unwilling to increase the probability of detecting and investigating corrupt agents, then it has to punish those who have been caught and convicted severely to achieve a certain degree of credibility in terms of its anti-corruption efforts.

This paper elaborates the logic of selectively punishing corrupt agents as seen in corruption cases in China. Widespread corruption persists despite the claims of the central authority that combating corruption is a primary policy goal. An important factor behind the rampant corruption is the unlikelihood that corrupt agents will be exposed and investigated. As this paper has shown, the state authority has not investigated many government officials, especially those of a high rank, although reports of their malfeasance abound. The fact that corrupt agents face little prospect of being exposed can be attributed to the inaccuracy of information or to the lack of determination or political will of the party-state. Whatever the reasons, the low probability of being detected and convicted of corruption undermines the credibility of the Party's anti-corruption efforts.

Nevertheless, the Party likewise realizes the consequences of tolerating corrupt agents and is therefore under pressure to protect its reputation for tackling corruption. In the 1990s, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 warned that, “if the Party does not take corruption seriously, [and] stop it resolutely, both the Party and country will … change face.”Footnote 37 Consequently, the central authority has to showcase its commitment to clamping down on corruption. As this paper demonstrates, top officials are more likely to receive harsher punishment, including life imprisonment, the death penalty with reprieve, and the death penalty, if they are convicted. Although this approach of meting out severe punitive sentences to high-ranking officials may, to some extent, protect the reputation of the central authority, the deterrent effect remains limited because of the lower probability of being detected and investigated. For this reason, the new administration under Xi Jinping 习近平 has increased its efforts to investigate and punish both high-ranking and low-ranking officials.