1. Introduction

Many overviews have argued the changing dimensionalities of electoral competition in Italy, identifying the rise of a distinct pro-/anti-European ideological divide (Di Virgilio et al., Reference Di Virgilio, Giannetti, Pedrazzani and Pinto2015; Giannetti et al., Reference Giannetti, Pedrazzani and Pinto2017). This policy dimension has appeared to be unrelated and orthogonal to other issue domains, arising from the overarching left–right dimension, and it may constitute a dimension of its own in Italy. This view is consistent with the works that have assessed the orthogonality of the pro-/anti-European ideological divide, which cuts across the left–right dimension (Hix and Lord, Reference Hix and Lord1997; Van der Brug and Van Spanje, Reference Van der Brug and Van Spanje2009).

The euro crisis (2008–2014) acted as a powerful catalyst in hastening the politicization of this issue dimension (Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017; Charalambous et al., Reference Charalambous, Conti and Pedrazzani2018), opening up new opportunities for the parties. In fact, the European institutions took center stage in promoting the formation of Monti's technocratic cabinet. Italy suffered from both a GDP stagnation and an unemployment rate increase. Moreover, Italy's public accounts came under market speculative attacks, resulting from the spillover effects of the Greek sovereign debt crisis. The EU increased pressure on the Italian government to implement austerity policies, fuelling political discontent. Indeed, the EU took center stage in the management of the financial crisis, determining policy guidelines at the domestic level. These efforts came from the creditor states intergovernmental bodies, under the leadership of the German government that was strongly committed to preventing new crises (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2013). Therefore, Italy coped with the economic crisis by reducing public spending and adopting austerity measures under the EU aegis.

According to Morini (Reference Morini, Nielsen and Franklin2017, Reference Morini2018), since the outbreak of the euro crisis, trust in the EU has collapsed in Italy, shifting from a permissive consensus to a clear-cut Euroscepticism. Thus, between 2007 and 2014, Italy gradually turned into one of the most Eurosceptic countries within the EU (Morini Reference Morini2018), becoming a very interesting comparative case study, justifying a country-based empirical study on EU conflict politicization. Therefore, the euro crisis may have unleashed a new divide, where parties have been more likely to politicize a pro-/anti-European dimension. Multidimensionality in political competition has often actually been considered as a resource for parties to reverse or strengthen an electoral trend (Riker, Reference Riker1986).

Thus, the research question is the following: Since the outbreak of the euro crisis, how much have Italian parties politicized European integration, transforming their electoral supply and reshaping voting preferences?

The notion of conflict politicization is crucial to this work, hinging upon party strategic efforts in emphasizing and polarizing new issues. To capture transformations in the electoral supply, the article uses the EU issue entrepreneurship index (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012) to assess the conflict politicization within the party system.

However, a conflict politicization also relies on the voters’ electoral responses to the resulting party supply. If the parties were able to link voter preferences on a structured pro-/anti-European dimension, a fully politicized European integration would emerge in the political system. To assess the link between party stances and electoral choices on EU issues, the Downsean proximity model (Downs, Reference Downs1957) is employed, testing the party/voter congruence on the pro-/anti-European dimension.

The first section introduces the hypotheses and fundamental theoretical definitions, such as conflict politicization and EU issue entrepreneurship. In the second section, the changes in party supply are ascertained by observing the EU issue entrepreneurship levels. The third section provides models of electoral preferences, analyzing the impact of a pro-/anti-European dimension on voting behavior. This work analyses the 2009–2014 period, based on available data of Italian voter preferences, provided by the European Elections Studies (EES). These electoral rounds allow for testing the politicization hypothesis during a crucial period, where Italian voter EU support had dramatically decreased.

2. The politicization of European integration

The notion of conflict politicization has been dealt with in many works, which have tried to shed light on this phenomenon. Van der Ejik and Franklin (Reference Van der Ejik, Franklin, Marks and Steenburgen2004) have identified the lack of party agency as an obstacle preventing the Sleeping Giant of European integration from awakening. When a political party matches voter preferences with a set of policy alternatives, conditioning voting choices, a political conflict may occur. Hutter and Grande (Reference Hutter and Grande2014) have developed a politicization index by combining three dimensions: salience, actor expansion, and polarization. Although recognizing the fundamental importance of issue saliency, they have considered the expansion of the actors involved (the scope of conflict) as a precondition to politicize a new divide, which mainly requires governmental and party actors operating in the electoral arena. Moreover, they have identified the positional polarization, defined as the intensity of a conflict, as another key ingredient, unleashing two opposing and stable, but radically diverging, political camps.

This work relies on Hutter and Grande's (Reference Hutter and Grande2014) three-dimensional approach to observe whether the party actors have tried to politicize a conflict in the party system. Consequently, a party system politicization is defined as a process of the transformation of previous non-contentious issues into an object of public contestation, which is mobilized by the parties, emphasizing and polarizing the new issues within the party system. EU issue entrepreneurship (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012), a yardstick combining issue positions and issue saliency, is adopted for measuring party politicization efforts, tracing their attempts to prime EU issues into the political debate. Therefore, the Entrepreneurship Increase Hypothesis (H1) arises: Since the outbreak of the euro crisis, Italian parties have become increasingly entrepreneurial on EU issues, thus politicizing a latent conflict in the party system.

Even if political parties play a pivotal role in introducing new conflicts (see also: Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2012), a politicization also depends on public opinion reactions in the electoral arena. This work argues that voter/party congruence is a compounding element to spark off a conflict within the political system. Indeed, when partisan supply does not match voter preferences on those issues entering the party system, there is no conflict in the political system. Issue politicization is also an activity of linking the elite positions to the broader voter orientations. Party issue priming does not translate into voting choices as a matter of course, often becoming a major failure when voters do not respond to these cues (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989). Although the party entrepreneurial commitments remain a necessary precondition for a conflict within the party system, a political system politicization entails a deep-seated linkage between voters and parties on the new issues, affecting electoral preferences. The political systems are also compounded by a no-party polity (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976), made up of citizens outside the elite sphere. Thus, to politicize a conflict in the political system, the voter responses should match the party entrepreneurial efforts, revealing a party–voter congruence on the new issues, which become significant electoral determinants.

This work relies on the Downsean minimum distance theory to verify whether the party/voter linkages have become substantiated over time, showing an increasing degree of EU issue voting (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010). Here, the EU Issue Voting Hypothesis (H2) arises: Since the onset of the euro crisis, the party–voter congruence on EU issues has increased its impact on Italian electoral preferences, politicizing European integration in the political system.

From the above-mentioned approach, there emerges a twofold objective. On the one hand, to examine transformations in electoral supply among the Italian parties and, on the other hand, to observe whether the electoral preferences have changed, realigning voters along the pro-/anti-European dimension.

In this work, party/voter positions are ordered within one single dimension, whereby, on one pole, parties/voters support less European integration (anti-Europeans) and, on the other pole, parties/voters support more European integration (pro-Europeans) (Ray, Reference Ray2007). Although this scale overrides some complexities inherent to the party policies, it potentially synthetizes general orientations toward European integration, encompassing various EU domains (budgetary, defense, foreign, etc.). This work attempts to identify the emergence of an overarching pro-/anti-European dimension, in the same vein as that for the left–right dimension. To explore the general pro-/anti-European dimension, the Chapel Hill Expert Surveys (CHES) are used, where experts were asked to indicate the orientation of the party leadership toward European integration, ranging from 1 (strongly opposed) to 7 (strongly in favor). The experts do not simply refer to party manifestos, but usually tap into different information sources (newspapers, roll-call votes, and leader discourses) (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenburgen and Vachudova2015). To capture the party positions, multiple information sources are considered more reliable.

3. EU issue entrepreneurship

The party capacities for maneuvering their position in the issue space are limited by their pre-established reputation (De Sio and Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014), while party strategies on issue emphasis can be modified or adjusted. The notion of saliency revolves around the parties’ selective emphases on the issues. Parties choose to focus on certain issues during electoral campaigns when they hold some competitive advantages, dismissing those issues that could benefit their adversaries (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983). Nevertheless, party positional shifts may actively interact with issue saliency. By expressing an extreme position on a certain issue, a party may actually boost that issue's visibility, while, when a party adopts moderate stances on a policy, it often aims at overshadowing that issue. Consequently, this work argues that policy position and saliency manipulations are closely interwoven, using the EU issue entrepreneurship notion, which combines issue saliency and position (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Hobolt and De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015).

Hobolt and de Vries (Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015) have come up with a clear definition of an issue entrepreneur, which is a party that ‘actively promotes a previously ignored issue and adopts a position that is different from that of the mean position in the party system’. (Ibidem, 1168). The two scholars provided a mathematical formula to calculate EU issue entrepreneurship: (P eu − MP eu) × SP eu. MPeu represents the average position in the party system on EU issues, while P eu indicates the single party stance and, finally, SP eu stands for the saliency that a party ascribes to EU issues. EU issue saliency is obtained through the CHES dataset, where experts evaluate the ‘relative salience of European integration in the party's public stance’ on a scale ranging from 0 – of no importance – to 10 – of great importanceFootnote 1. The objective is not to establish the EU issue entrepreneurship direction, positive or negative, but seek to ascertain the index magnitude, shedding light on the emergence of a new dimension. Those parties seeking to politicize European integration would increase their score, achieving an entrepreneurship increase strategy. Conversely, the parties aiming to deflect the EU issues would diminish their score, achieving an entrepreneurship decrease strategy. The 2010 score is established as the index to observe whether the parties achieved an increase/decrease strategy. If the 2014 party score exceeds at least one unit compared to the 2010 score, the strategy is qualified as an entrepreneurship increase. Instead, if a party score diminishes by one unit or remains stagnant, it is an entrepreneurship decrease strategy.

This empirical step presents some challenges in Italy, where it is difficult to achieve a cross-time analysis. In fact, the Italian 2013 elections fell into the category of critical elections (Key, Reference Key1955), where the Total Electoral Volatility (TEV) (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990) reached a score of 39.1 (Chiaramonte and Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte, Emanuele, Chiaramonte and De Sio2014). This trend mirrored a mass electoral realignment, coupled with the emergence of new electoral parties. The party competition patterns changed, marking an unprecedented voting shift from the two pre-established electoral coalitions (center-right and center-left) toward new parties (M5S and SC). These electoral trends revealed a genuine tripolarization of the electoral supply, bringing to a close the bipolar era. Many parties resulted from the internal splits of pre-existing political subjects (FI, FDI, and NCD), new ones being created ex-novo (M5S), while others vanished (IDV). Observing the EU issue entrepreneurship variations is complicated because of this electoral volatility, making it impossible to ascertain the 2010 indexes achieved by new parties. However, by assuming electoral fragmentation as a constant, the work observes the entrepreneurial swings of the established parties (PD, LN, etc.) and the strategic efforts of the new ones (M5S, etc.).

4. The Italian party supply on the pro/anti-European issue dimension (2010–2014)

The criterion to delimit the party selection is a vote threshold, including the parties polling at least 3% of votes. Unquestionably, ‘there is the difficulty of establishing a threshold, since any cut-off point is inevitably arbitrary’. (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990, 128). In spite of its approximation, the chosen yardstick can be a rough indication of party blackmail or coalition potential (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976). The established threshold is extrapolated from the EP elections with the available data being provided by the EES (2009–2014).

4.1 EU issue entrepreneurship in 2010

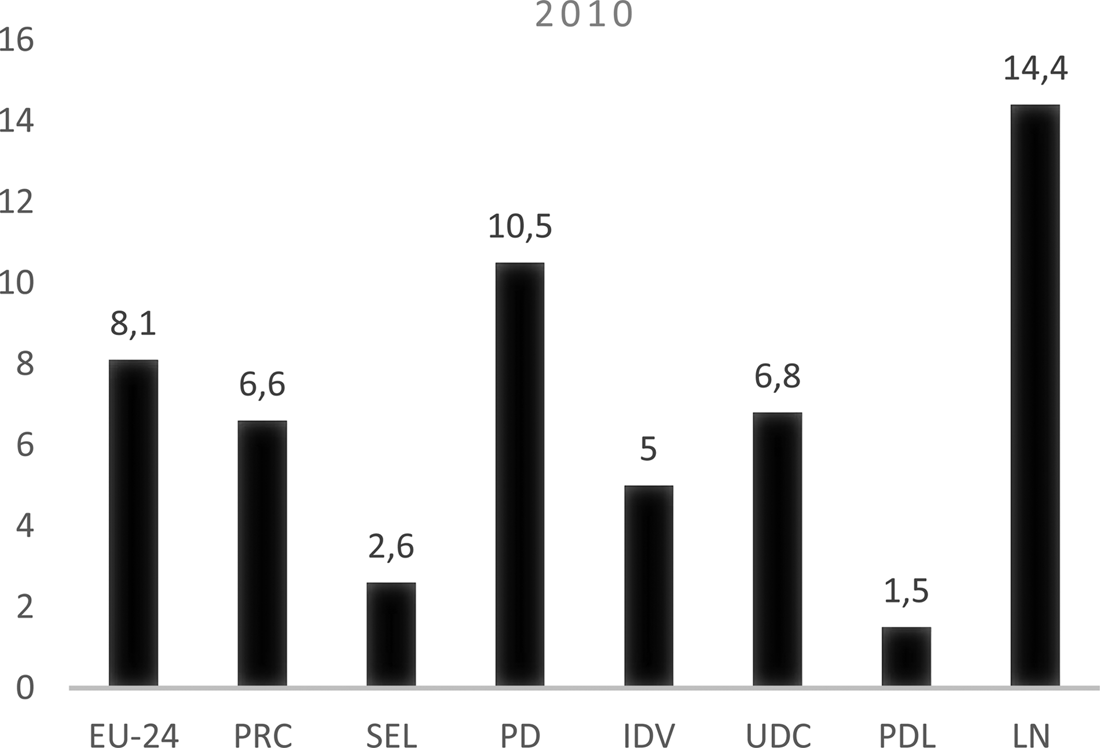

In Figure 1, the degree of Italian party entrepreneurship for 2010 is reported. To better qualify the scope of EU issue entrepreneurship in Italy, this table also shows the average entrepreneurship index achieved by the main European political parties, using the same criterion adopted for selecting the Italian parties.Footnote 2 This index is made up of the simple arithmetic mean of the main parties’ EU issue entrepreneurship, allowing for observing the comparative magnitude of the Italian parties’ strategic efforts.

Figure 1. 2010 EU issue entrepreneurship.

Many parties showed negligible levels of entrepreneurship, including the major government actor – The People of Freedom Party (PDL). Berlusconi's party recurrently advanced an opposition to European integration, often deviating from the other pro-European center-right parties belonging to the European People's Party (EPP). Since its foundation, Forward Italy (FI) linked its EU stand to Italian interests, periodically swinging from a Euro-pragmatic to a Euro-critic position. According to Conti (Reference Conti2006), the party commitment to market liberalism fostered a favorable orientation toward European integration. However, the party never endorsed the construction of a federal EU (Conti Reference Conti2006; Conti and Memoli Reference Conti, Memoli and Conti2013), perceiving the EU as more of a market integration project. In 2008, the FI merged with the other Italian center-right party (AN), founding the PDL, which went on to win the 2008 general elections. The 2010 observation reflects the PDL's lack of references on European integration. This party placed a low emphasis on EU issues (3.7), obtaining an insignificant level of entrepreneurship (1.5). The PDL probably sought to overshadow the conflict with the European Commission (EC). Indeed, the party electoral program pledged a large-scale tax reduction and important infrastructural projects in 2008. These policy goals contrasted with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) ceilings, which could have limited the responsiveness of Berlusconi's cabinet. Therefore, the major governing party blurred the existing external constraints, minimizing this potential issue divide.

Surprisingly, the radical left parties were not very committed to politicizing EU issues. The Communist Refoundation (RC), stemming from the Italian Communist Party (PCI) adopted a critical stance on European integration (Conti, Reference Conti2006; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Taggart and Szczerbiak2008). The party linked the deepening of the EU to a neo-liberal market, potentially threatening workers’ conditions. However, Conti and De Giorgi (Reference Conti and De Giorgi2011) empirically demonstrated that, while the RC held ministerial positions in the second Prodi government (2006–2008), it fully endorsed pro-European legislative measures. This pattern revealed a growing inconsistency between the party's ideological background and its policy actions. This became more evident in 2010, with the RC adopting a soft Eurosceptic stance (3.3), weakly emphasizing EU issues (3.7) and achieving a modest level of entrepreneurship (6.6).

The other party in this political camp was the Left Ecology and Freedom (SEL), led by the President of the Apulia Region, Nicky Vendola. SEL formed electoral coalitions both regionally and locally, developing a coalition potential in the center-left. By adhering to these electoral alliances, this party embarked on an ideological moderation path, changing its strategies on the EU. The party displayed a neutral ideological position (4.5) on EU issues, combined with a very low emphasis on European policies (4.3). SEL was faced with a trade-off between its government aspirations and to some extent an anti-European ideological background. Thus, the party adopted a dismissive strategy on EU issues, minimizing this source of political contestation by assuming a low entrepreneurship level (2.6).

The Union of the Center (UDC) represented a position of continuity with the Italian Christian Democracy (DC), embodying a strong support for European integration. As a Christian Democrat party, belonging to the EEP, the UDC persistently maintained a pro-European position, but without achieving a prominent entrepreneurship (6.8). Similarly, the Italy of Values (IDV), led by a former magistrate, Antonio Di Pietro, although displaying Europhile attitudes and belonging to the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for the Europe Group (ALDE), was not very committed to politicizing European integration.

On the contrary, two parties reached important levels of entrepreneurship – the Democratic Party (PD) and the Northern League (LN). These two parties strongly diverged in ideology and government status, but both often drew attention to EU issues. Many works assessed the LN positional flexibility along the pro-\anti-European dimension (Giordano, Reference Giordano2004; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2005; Conti, Reference Conti2006). The party program revolved around the political empowerment of the Northern regions, at times petitioning for secession and challenging the central state. Initially, the LN identified the EU as a hospitable environment to fulfill its policy goals. The party elite perceived European integration as a political device to reduce the prerogatives of the nation-state, moving toward a ‘Europe of regions’ (Morini, Reference Morini, Nielsen and Franklin2017). The party aimed to strategically exploit the alleged Italian incapacity to meet the convergence criteria to join the single currency, justifying the creation of a new state (Padania) to reach this objective (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Taggart and Szczerbiak2008). After the Italian accession to the European Monetary Union (1998), the LN saw the EU as a hurdle for de-centralization. Thus, the party shifted to an anti-European position, accompanied by a radical rightwing adjustment (Caiani and Conti, Reference Caiani and Conti2014). The LN clearly established its ownership on Euroscepticism, breaking a pro-European consensus in Italy. Nonetheless, by examining the LN roll-call voting in parliament, Conti and De Giorgi (Reference Conti and De Giorgi2011) found scant congruence between the party's self-declared anti-Europeanism and its legislative behavior, which had been recurrently Euro-pragmatic. Their governmental status could have largely explained a certain positional moderation on European integration policies. However, although it had partially blurred its position on European integration, this party was the strongest (Eurosceptic) entrepreneur in Italy in 2010, achieving a score of 14.4.

On the other hand, the Italian PD steadily supported the deepening of European integration, which constituted an important part of its political ideology. This party resulted from the merger of the Left Democrats (DS) and the Daisy – Liberty and Freedom Party (DL) in October 2007. Both these political formations had previously developed a principled Europeanism approach (Conti, Reference Conti2006), which entailed an increasing authority transfer to the supranational institutions, leaning toward a federal vision of Europe. Thus, they marked a strong ideological distance from the center-right parties, which endorsed a qualified inter-governmentalism (Quaglia and Radaelli, Reference Quaglia and Radaelli2007). This pro-European stand resulted from center-left government experiences (1996–2001; 2006–2008), where these cabinets took important integration steps. The first Prodi government (1996–1998) expressed its political commitment to meeting the convergence criteria for the EMU accession, enacting some domestic policies, such as fiscal adjustments and budget cutbacks. Thus, the cabinet combined Italian internal affairs with European issues, which topped its political agenda, presenting entry to the EMU as the core political objective to be pursued by the government. By accomplishing the EMU accession, the two main center-left parties enhanced their reputation as pro-European actors with the PD foundation not changing any of the center-left Europhile strategies, which played an important role in the party platform. The party displayed a very pro-European position (6.4), attaching notable saliency to EU issues (7), becoming a relatively strong Europhile entrepreneur (10.5).

In brief, this work argues that the Italian debate did not significantly revolve around EU issues, also mirroring its low comparative systemic saliency, where Italian party entrepreneurship lagged behind the mean level achieved by other European parties (8.1). This finding is consistent with the empirical background presented by Giannetti et al. (Reference Giannetti, Pedrazzani and Pinto2017), who observed a limited politicization of EU issues during the pre-2013 election period.

Many party actors did not seem committed to politicizing a new political divide, seeking to maintain the pre-existing conflicts. Neither mainstream (FI, UDC, and IDV) nor protest parties (RC and SEL) tried to alter their electoral supply to realign voters on a new issue dimension. Nevertheless, two notable outliers came into being – the PD and LN. These parties, which achieved politicization strength in two opposing directions, were already acting as authentic entrepreneurs, perhaps laying the foundations for the establishment of the pro-/anti-European conflict.

4.2 EU issue entrepreneurship in 2014

The electoral supply abruptly reversed in 2014 (Figure 2), probably due to the consequences of the euro crisis. The established Italian parties (PD, LN, FI, and SEL) increased their EU issue entrepreneurship and the new-comers (M5S and FDI) tackled this conflict. Three parties, LN, M5S, and FDI, behaved as strong Eurosceptic entrepreneurs, prompting a further polarization on EU issues, which may have given rise to this dimension.

Figure 2. 2014 EU issue entrepreneurship.

The LN stood out as the most prominent actor in this anti-European party cluster. In 2011, many events (Berlusconi's downfall and LN party official judicial investigations) paved the way for a landmark leadership turnover, when Matteo Salvini won the party primaries.

Salvini's seizing of power ushered in a new era for the party, taking the LN toward an ideological and strategic restructuring. Under his leadership, the LN relinquished the politicization of the center-periphery cleavage (Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017), ceasing to underline regional questions. The party largely focused on European integration, strongly conveying anti-European messages to its constituents. In 2014, the LN shifted its stance by assuming a very extreme Eurosceptic position (1.1), ascribing a strong emphasis on EU issues (8.9) and doubling its entrepreneurship score (28.5). It crusaded against the austerity policies and European institutions, launching anti-European political rallies (Morini, Reference Morini, Nielsen and Franklin2017, Reference Morini2018). Salvini pledged to withdraw Italy from the single currency, also accusing the EU of a lack of democratic accountability (Castelli Gattinara and Froio, Reference Castelli Gattinara and Froio2014). The LN combined an anti-austerity platform with some nationalistic-identitarian arguments related to EU integration. Above all, the party tried to seize on popular concerns regarding the weakening of nation-state borders, favored by European integration, maintaining its ownership of anti-immigration issues, incompatible with support for European integration. This party perhaps found a winning formula – economic-utilitarianism and nationalism. However, the party's anti-European reputation was probably eroded away by its positional fluctuations, due to the change in its governmental status and leadership turnover.

The second of these strong Eurosceptic entrepreneurs has been the Five Star Movement (M5S), the Italian post-crisis success story. Many works stressed the distinctive populist character of this party, which directly appealed to the real people (the civil society), rejecting the inward-oriented political class, derogatorily defined as the caste (Franzosi et al., Reference Franzosi, Marone and Salvati2015). Consequently, the M5S increased its reputation as an anti-political and anti-establishment actor, stressing anti-corruption and cost-cutting issues in Italy. In 2013, the party program had not officially expressed any direct reference to EU issues, which were absent from its platform (Corbetta and Vignati, Reference Corbetta and Vignati2014). Castelli Gattinara and Froio (Reference Castelli Gattinara and Froio2014) underlined that Grillo himself criticized EU bureaucratic decision-making, which led to the formation of Monti's cabinet. The 2014 CHES's round empirically supported this strong Eurosceptic identity, mirrored by an extremely high EU issue entrepreneurship level (25.8). The M5S cued the voters with Eurosceptic political shortcuts by adopting a radical anti-European stance (1.4), over-emphasizing the EU issues (8.9). In 2014, the party campaigned on an anti-European political platform, the seven-point program for Europe, calling for the elimination of the fiscal compact and the creation of Euro bonds. Furthermore, the party questioned Italian membership in the Euro, proposing a national referendum to leave the Eurozone. The M5S tried to politicize European integration, clarifying its Euro-critical positions to gain electoral advantages from the spreading popular Euroscepticism.

The third strong Eurosceptic entrepreneur was the right-wing party, Brothers of Italy (FDI). The PDL parliamentary backing of the Monti government prompted many intra-party divisions, leading to an internal split and the foundation of the FDI. This splinter party was chiefly made up of the former National Alliance (AN) elite, who took the leadership of the re-branded party. The FDI underwent an ideological transformation, modifying its position on EU issues, vigorously reacting against the EU-driven austerity packages and adopting an outright anti-European stand (2.2), thus, obtaining a strong level of entrepreneurship (14.3). The FDI primed the EU issues by joining the anti-currency camp and opposing the major EU-led fiscal restraints (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Cotta and Verzichelli2016). In doing so, this party relinquished its mainstream party status, embracing a protest-oriented platform. However, the FDI tackled many other policy facets, such as social and immigration issues, encompassing the left–right dimension. Therefore, although the FDI may have increased its voting support along the pro-\anti-European dimension, its electoral fortune can still be explained by traditional political conflicts.

Although the radical left parties, SEL and RC, boosted their EU issue entrepreneurship, they lagged behind their radical right counterparts. When the PD-SEL alliance failed to obtain an absolute majority of seats in both the Houses of Parliament, the PD chose to form a grand coalition with the center-right. Hence, SEL re-profiled itself as an anti-European party (3.1), strengthening EU issue saliency (5.6) and increasing its entrepreneurship level (6.7). In 2014, SEL formed an electoral cartel, the Tsipras List (LT), with other leftist formations, including the RC, which also increased its Eurosceptic entrepreneurial strength. The LT raised opposition to the EU neo-liberal bias, opposing austerity policies imposed by the European institutions. Hence, the Italian radical left restructured its Eurosceptic electoral supply (Calossi, Reference Calossi2016), establishing an anti-austerity platform, criticizing the fiscal compact (Morini, Reference Morini2018).

The main center-of-right party, FI, increased its tactical endeavors on this policy dimension. In 2011, Berlusconi was toppled due to mounting international pressures, which reached a peak in the autumn, when an extraordinary European Council summit was held to specifically tackle the Italian crisis. Berlusconi blamed the European institutions for his government's downfall, determining a pronounced anti-European turn of the PDL. In spite of the party's vote of confidence for Monti and the legislative support for the austerity measures, the PDL adopted a Eurosceptic stance (Castelli Gattinara and Froio, Reference Castelli Gattinara and Froio2014). Consequently, in the 2013 campaign, the PDL recurrently accused Monti of his pro-German leanings, which were placing the Italian economy under pressure. Thus, the PDL primed outright anti-European arguments, drawing attention to the negative consequences of the austerity policies. This positional shift was unmistakably clear in 2014, when Berlusconi's party, re-labeled FI, took a negative stance on European integration (3.4), becoming an anti-European mainstream party. The FI actually boosted its level of saliency ascribed to EU issues (5.9), increasing its entrepreneurship (5.3). To sum up, the FI expressed a moderate European opposition, which was probably related to a determined economic-political conjuncture.

The center-of-left PD also increased its politicization efforts on the pro-/anti-European dimension. In December 2013, the 38-year-old mayor of Florence, Matteo Renzi, won the party primaries, marking an important generational turnover within the PD. He subsequently replaced his party colleague, Enrico Letta, as Prime Minister. Renzi's government was a turning point in center-left strategies concerning European integration. Though the party support for European integration remained stable (6.6), Renzi clearly changed the PD narrative on EU issues (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016). He focused more on European questions, achieving a notable level of saliency (7.6) and, thus, increasing the party's entrepreneurship (17.5). Renzi initially deployed the traditional pro-European rhetoric of the Italian center-left, resorting to the external constraint principle to warrant his policy-making. He presented reforms (including institutional ones) as a necessity required at the European level, which gave his government a key legitimacy. However, Renzi subsequently reverted this narrative concerning Europe, presenting demands for pro-growth measures within the Eurozone. Furthermore, the Prime Minister emphasized the EC's lack of democratic accountability, placing the blame on the EU for the worsening of Italy's economic situation. He tried to publicly prove his ability to resist European directives and to obtain a margin of discretion in budgetary policies (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016). However, in spite of these inter-institutional conflicts, the Italian PD never abandoned its pro-European tradition, playing on its Europhile position electorally. In a nutshell, the party politicized the EU conflict, colliding with the other political formations on the pro-\anti-European dimension.

The Italian UDC was the only party not to increase its EU issue entrepreneurship. The party had supported the technocratic Monti cabinet, endorsing its major austerity reforms and joining the centrist coalition, With Monti for Italy. This party aligned itself with the pro-austerity political camp, continuing on the European policy path begun by Monti. Nonetheless, after its defeat in the 2013 elections, the UDC reduced its EU issue saliency (4.3), acknowledging the drawbacks of the previous strategy. In 2014, the UDC formed an electoral cartel with the New Center-Right (NCD), a splinter party emerging from the PDL, which was created to support the Letta cabinet after the PDL's defection. The party became the PD's major coalition partner, expressing a vote of confidence also for the Renzi government. The NCD staked out a notable pro-European policy stance (5.8), emphasizing EU issues (7.7) in its political discourse. Thus, this party clearly attempted to set underway this policy dimension, obtaining a prominent level of entrepreneurship (12.2). Apart from the PD, the NCD resulted in being the most active pro-European entrepreneur.

These empirical findings allow for formulating a proposition on the Italian party electoral supply: Since the beginning of the euro crisis, Italian parties have become increasingly entrepreneurial on EU issues, thus politicizing a latent conflict in the party system. Consequently, H1 was corroborated by these results, where the majority of Italian parties increased their EU issue entrepreneurship (Table 1). Indeed, the pre-established parties (LN, PD, PDL/FI, SEL, and RC) adopted an Entrepreneurship Increase strategy, with the only exception being the UDC. Furthermore, the new parties (M5S, FDI, and NCD) strongly cued the voters on this issue dimensionality, sensing a political opportunity.

Table 1. Party strategies and EU issue entrepreneurship (2010–2014)

Therefore, the Europhile/Eurosceptic political entrepreneurs flourished, largely restructuring the electoral supply and, perhaps, electorally realigning voters. This trend is also mirrored by the comparative index, where most Italian party entrepreneurial efforts exceeded the average European entrepreneurship (8.3). Nonetheless, the Italian case requires a further empirical step to understand whether this conflict politicization actually occurred in the political system, observing the impact of EU issues on votes.

5. Voting preferences and European integration

The previous section has demonstrated the systemic growth of EU issue entrepreneurship, empirically sustaining H1. Consequently, the expectation is to observe an analogous transformation in voting behavior, where, since the onset of the euro crisis, the party–voter congruence on EU issues has increased its impact on electoral preferences (H2). The congruence between party supply and electoral preferences may have effectively prompted the politicization of the European integration conflict. Using the EES rounds (2009, 2014), linear regression models can be designed to analyze the relationship between Italian voters and European integration. These models are based on the Downsean ‘smallest distance’ theory (Downs, Reference Downs1957), where the voters are predicted to vote for the party closest to their preferences on one-dimensional issue space, varying from extreme left to extreme right. This work introduces a supplementary issue dimension, ranging from pro-European to anti-European, hereby regarded as a general dimension, synthetizing the other policy parcels inherent to European integration. The hypothesis is that voter/party proximity on the pro-/anti-European dimension has increasingly explained Italian electoral preferences. Thus, a meaningful increase in EU issue voting (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010) should be discerned from 2009 to 2014.

The work's dependent variable is the propensity to vote for a party, which arises from the conception of party utility (Downs, Reference Downs1957), subsequently redefined by Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007). According to Downs (Reference Downs1957), each voter has a system of preferences associated with each party, related to the expected benefits to be gained. Thus, the voter chooses the party that best matches their rational expectations. Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007) provided another empirical tool – the propensity to vote – hereby dubbed as party/electoral/voting preference. This article relies on voting propensity because voting choice, operationalized as a dichotomous variable, displays many weaknesses. Indeed, voting choice would be inadequate in representing the voter/party relations as voters do not totally reject the parties they are not voting for (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007), being biased by strategic calculations or institutional binding rules. Moreover, the use of voting propensity results in a more accurate control of party characteristics, allowing for comparing parties of different sizes by multiplying the number of cases. In fact, the EES voting choice does not actually provide a sufficient number of cases for comparing all the parties under study. As well, this dependent variable is more apt to test voter/party ideological congruence, better identifying individual voter characteristics (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007).

By assuming that voters are more prone to increase their voting propensity for a party that is contiguous to their ideological positions, two independent variables have been identified – left–right proximity and the pro-/anti-European proximity. These are created by calculating the ideological distance between the party positions (relying on the CHES rounds) and self-declared voter positions (available in the EES studies), and are both coded as 11-point variablesFootnote 3. When a voter increases their propensity to vote for a party by minimizing their ideological distance from the party issue position, the models will show a negative coefficient, thus demonstrating the party–voter ideological congruence. Instead, when a voter decreases their voting preference for a party by minimizing their ideological distance from the party issue position, there will be a positive coefficient, proving the voter–party ideological discrepancy. The expectation is that the European integration proximity has gained in explanatory power, while the left–right proximity has turned out to be less significant as a voting determinant. Consequently, the 2014 elections should have marked a discontinuity on voting causal factors, partially minimizing the impact of traditional conflicts. The models designed also take into consideration control variables to check other explanations. Party closeness is a proxy of the party identification, traditionally a powerful predictor of voting behavior (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960). Socio-demographic variables, such as gender, age class, and education years, traditionally affect voting preferences, being a source of empirical control. The cleavage variables are religiosity and trade union membership, which have also swayed the electoral preferences. Church-going voters tend to support conservative parties, while secularized voters usually support leftist parties. Trade union membership is a proxy measuring the class divide as a voting determinant. Finally, unemployment statusFootnote 4 is a measure of financial crisis contingent effects, which may reshape voter preferences.

5.1 EU issue voting in 2009

The 2009 elections reflected the low impact of the pro-/anti-European proximity on voting preferences, where the major parties were not influenced by the European integration conflict. In the previous sections, the LN was found to be a strong politicization agent, injecting Euroscepticism into the Italian context. However, the empirical results did not reveal any impact of a pro-/anti-EU proximity to explain the LN preferences, disproving the expectations. Although the party tried to establish its ownership of Euroscepticism, it had not electorally exploited its cues on this dimensionality. Even the core Europhile entrepreneur, the PD, had not electorally benefitted from the EU issue dimension. Conversely, traditional variables displayed prominent effects on the PD voting propensity, such as party closeness and left–right proximity. Moreover, trade union members were more likely to support the PD, mirroring the endurance of the cleavage-based explanation.

Instead, the PDL downplayed EU issues in the political debate, trying to capitalize on other sources. This electoral analysis corroborates this expectation, confirming the PDL's unwillingness to compete on the pro-\anti-European dimension. Meanwhile, its proximity to voters on the left–right dimension held a strong explanatory power, being its chief voting determinant. The UDC, which devised Europhile shortcuts, did not electorally benefit from European integration proximity, which was statistically insignificant. On the contrary, this party relied on other explanations, attracting the electoral support of church-goers.

The RC epitomized a pattern of moderate opposition toward European integration, criticizing its neo-liberal embodiment, without strongly emphasizing EU issues. Unsurprisingly, this party did not capitalize on pro-/anti-EU proximity from voters, benefitting from other explanations (Table 2).

Table 2. Electoral preferences in Italy (2009)

Note: All estimates are from OLS models.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

However, two party formations, the IDV and SEL, which had not stood out as strong EU issue entrepreneurs, gained voting preferences along the pro-/anti-European dimension. The IDV, which did not strongly profile itself on EU issues, boosted its support by approaching voters on this dimension. This variable gained an important explanatory power within the party voting equation, being statistically significant. This empirical round took place in a very positive context for the IDV, which drew support from pro-European electors, gaining 8% of the votes. Nevertheless, this indicates a low consistency with the IDV entrepreneurial efforts on EU issues, which were weak. Similarly, SEL did not exhibit a strong level of EU issue entrepreneurship, providing voters with middle-of-the-road cues. Surprisingly, SEL gained electoral benefits by conveying moderate messages on European integration, being rewarded by voters, who probably appreciated its neutral stand.

It is worth noting that the 2009 elections took place in a period when EU issues were still uncontested and uncontroversial, being predominantly outweighed by the left–right issues as voting explanations. Indeed, this analysis ascertains the strong congruence between party supply – non-priming of European integration – and voter preferences – weakly reacting to these cues. Although two exceptions, IDV and SEL, emerged, the Italian parties did not reap substantial electoral payoffs on this dimension.

5.2 EU issue voting in 2014

The 2014 elections occurred at a different juncture, where the relationship between the Italian people and the EU had markedly deteriorated (Morini, Reference Morini, Nielsen and Franklin2017), opening up a window of opportunity for many political actors. The Italian parties, both the old and the new, increased their strategic efforts on the pro-/anti-European dimension, seeking to politicize a new conflict (Table 3).

Table 3. Electoral preferences in Italy (2014)

Note: All estimates are from OLS models.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The LN was the chief actor in boosting its EU issue entrepreneurship, attempting to realign voters on the pro-/anti-European dimension. However, these elections brought to light an unforeseen finding, that is, the null impact of pro-/anti-European proximity on LN support. Although the LN multiplied its entrepreneurial activities on this issue dimensionality, clarifying its Eurosceptic stance, it failed to reap any consequent electoral benefits. The voters may have encountered several difficulties in understanding the LN position, which was continuously modified by the party elite. Therefore, the LN conveyed blurred messages, without realigning the Italian electors on this dimensionality. Nevertheless, this empirical step is a snapshot of the early Salvini era, where the new leader undertook a strategic party renewal. Thus, the party may have planted the seeds for creating a new majority of voters along the pro-/anti-European dimension, gaining advantages in the medium-term.

Another important Eurosceptic outlet was the M5S, which established an anti-European program, advancing outright criticism of the single currency. The electoral round lent support to a pattern, where the M5S did not benefit from EU issues. Instead, this party successfully realigned the Italian electors along the left–right dimension, challenging the pre-established ideological divisions. Indeed, the left–right proximity variable proved to be a substantial and statistically significant explanation for M5S voting preferences. By providing voters with populist cues and by adopting a centrist position on this dimension, the M5S reshaped collective identities on the left–right issues.

The last Eurosceptic actor was the FDI, which failed to strategically prime the anti-European messages, gaining no benefits from the pro-/anti-European proximity. The party had probably suffered from its incumbency status, when it leaned toward a more Europhile position by endorsing Monti's policies. Furthermore, in being a new-comer, the voters may have had an unclear perception of its re-profiled anti-European shortcuts. Conversely, the Italian electorate had been more familiar with the FDI's rightist values, rewarding the party along the left–right dimension.

The radical left parties, SEL and RC, merged into the LT cartelFootnote 5, mostly cueing voters on the economic anxieties related to European integration. However, when the Italian radical left embarked on a more anti-European path, it did not increase its voting preferences on this issue dimensionality. Instead, the electors preferred other program aspects, probably revolving around economic policies. Therefore, the LT primed an anti-austerity platform, but it failed to link these issues to a Eurosceptic program.

The FI carried out a policy shift on this dimension, profiling itself as a mainstream Eurosceptic actor, enhancing its level of EU issue entrepreneurship. In 2014, the party achieved a statistically significant coefficient with a positive sign. Thus, voters reduced their propensity to vote for the party by ideologically approaching the FI Eurosceptic stance, revealing a positional incongruence with this aspect of the party program. The FI failed to steer the Italian electors on the anti-European position and its constituents leaned toward Europhile values. The party did not develop any credibility by outlining anti-European cues and this ideological leap may have triggered many concerns among its voters, who rejected a negative discourse on European integration.

The 2014 elections took place when the PD regained the reins of power and Matteo Renzi was enjoying his honeymoon period with the Italian electorate (Segatti et al., Reference Segatti, Poletti and Vezzoni2015). Renzi was committed to changing the content of pro-European discourse by shifting the blame onto the EU institutions, augmenting the PD's EU issue entrepreneurship. This empirical observation highlights a switch in voter motivations, where they minimized their ideological distance from the Europhile PD, increasing their likelihood to vote for the party. The pro-/anti-EU proximity variable increasingly explained the PD strength, becoming a statistically significant coefficient. By consistently developing pro-European messages and emphasizing EU issues, the PD spurred well-defined reactions among voters.

The other Europhile channel, the UDC, widened its voting propensity along the pro-\anti-European issue dimension, which exerted an explanatory power. The UDC targeted those who were more likely to support austerity policies, bringing electoral payoffs to the party. On the contrary, the governing NCD, which formed an electoral alliance with the UDC, was not able to gain electoral advantages on this issue dimension. This party did not manage to clarify its EU position, being a relative new-comer and a splinter party.

In 2014, the Italian electoral supply witnessed the rise of many anti-European outlets, priming Eurosceptic cues after the euro crisis. These protest parties attempted to exploit this factor, aiming at reversing the traditional voter majority and reshuffling electoral alignments in their favor, while mainstream actors responded along the pro-\anti-European dimension, conveying Europhile messages to the voters. Nonetheless, the findings contradict H2, disproving the electoral transformations, resulting in formulating the following statement: Since the onset of the euro crisis, the party–voter congruence on EU issues has not widely increased its impact on Italian electoral preferences, without politicizing European integration in the political system.

EU issue voting played a minor role in realigning voter preferences, only affecting the PD and UDC performance. These Europhile parties had probably been rewarded by voters for their major consistency on general integration policies, where they had not carried out any significant positional adjustments. Conversely, the other parties, especially the Eurosceptics, adopted many positional shifts along this dimension, being unable to simplify their cues. This empirical step reveals the major importance of achieving issue clarity to set in motion a conflict politicization and, thus, reshape electoral preferences (Carmine and Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1989).

6. Conclusions

Although some overviews have heralded the politicization of the European integration in Italy (Di Virgilio et al., Reference Di Virgilio, Giannetti, Pedrazzani and Pinto2015; Giannetti et al., Reference Giannetti, Pedrazzani and Pinto2017), there is evidence that trends are taking a different direction. The parties have effectively transformed their information shortcuts, priming EU issues to turn the latter into a source of electoral contestation. Indeed, the Entrepreneurship Increase Hypothesis has been borne out by empirical observations, indicating the transformative powers of the euro crisis. The Italian parties have actually politicized European integration in the party system, aiming to reap electoral benefits. Nonetheless, there has been a mismatch between strategic efforts and voter response, the latter mainly aligning themselves along the left–right dimension, overriding the EU issues. The findings have showed that the Italian voters have not been prone to reduce their ideological distance from parties on a pro-/anti-European dimension, disproving the EU Issue Voting Hypothesis. By observing the lack of congruence between party supply and electoral preferences, the limited nature of this conflict politicization is showed, remaining non-contentious in the political system. Thus, Italian parties have politicized the EU issues within the party system by emphasizing and polarizing these previously neglected issues in public debate. Nonetheless, in spite of their entrepreneurial efforts, they have failed to politicize the EU issues within the political system, because the party–voter congruence on these issues has not increased its impact on electoral preferences. By advancing these remarks, this article rules out the establishment of a general pro-/anti-European dimension, while the left–right dimension has remained resilient.

One of the key arguments explaining this limited politicization is the failure of party cueing activities. Indeed, Italian parties have constantly repositioned themselves on the pro-/anti-European dimension. These recurrent policy adjustments may have blurred the cues for voters, hampering any issue evolution. Parties have displayed many inconsistencies, maybe preventing the establishment of well-defined party/voter relations. If the party elites are not capable of clarifying their issue positions, then the likelihood to observe mass electoral re-alignments will diminish. Consequently, issue clarity (Carmines and Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1989) remains a fundamental pre-condition for a deep-seated conflict politicization. The Italian voters, by encountering an unstable electoral supply, may have been prevented from developing clear attitudes on EU issues. In fact, the Europhile parties, PD and UDC, which achieved a major ideological consistency, have gained some electoral benefits from the messages they conveyed to voters. On the contrary, Euroscepticism has not shown to be electorally profitable, though negative sentiments on European integration have arisen in Italian society (Morini, Reference Morini, Nielsen and Franklin2017). The anti-European channels – the LN, M5S, FDI, and LT – were not able to consolidate their ownership of Euroscepticism. Therefore, this was not an electoral asset as these parties did not link voter preferences along with this issue dimensionality.

This work is a snapshot of the evolving trends in the Italian electoral supply, where many actors adopted new strategies to politicize this conflict. Their entrepreneurial efforts may sediment over time, especially for the LN, M5S, and FDI, triggering medium- or long-term electoral realignments. Consequently, the Italian case will require a constant monitoring to understand the potential changes in voting preferences and the 2018 general elections represent the necessary empirical test to assess if this conflict will extend its reach over the overall political system. In fact, 2014 did not represent the peak of Euroscepticism in Italy (see: Eurobarometer 81–89), which has been steadily increasing. Moreover, this analysis has excluded the catalyst effect of the refugee crisis, erupting in 2015 (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), and linked to the negative response of the Visegràd countries, potentially leading to an external Eurosceptic contagion.

Summing up, the Italian case presents some problematic aspects related to the unstable positions and the opaque information shortcuts of the parties, which may have hindered the establishment of a pro-/anti-European dimension. A thorough politicization of European integration can be rejected as only scatter effects of EU issue voting were found. This observation has weakened a short-term hypothesis of a conflict politicization, which probably requires long-term interaction between elite cues and voter responses. Although the euro crisis has catalyzed a systemic growth in EU issue entrepreneurship, this clear-cut increase has not resulted in a new conflict in the political system, with EU issues not being translated into a matter of electoral contestation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2019.16

Author ORCIDs

Luca Carrieri, 0000-0002-6394-2746.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Leonardo Morlino and Susan Scarrow for their comments and advice.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.