Introduction

Entrepreneurship studies have looked extensively at several concepts that influence entrepreneurial activity, especially the concept of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess2001; Poon, Ainuddin, & Junit, Reference Poon, Ainuddin and Junit2006; Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, & Frese, Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009; Semrau, Ambos, & Kraus, Reference Semrau, Ambos and Kraus2016; Mthanti & Ojah, Reference Mthanti and Ojah2017; Stambaugh, Martinez, Lumpkin, & Kataria, Reference Stambaugh, Martinez, Lumpkin and Kataria2017). EO ‘represents policies and practices that provide a basis for entrepreneurial decisions and actions’ (Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009: 763) and is considered to provide the basis for growth, competitive advantage and superior performance for firms (Kraus, Rigtering, Hughes, & Hosman, Reference Kraus, Rigtering, Hughes and Hosman2012). EO dimensions include innovation, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009; Mthanti & Ojah, Reference Mthanti and Ojah2017). However, little is known about how EO influences new business development among Indigenous communities. What has been lacking is a conceptual basis for examining EO from an Indigenous perspective (Swinney & Runyan, Reference Swinney and Runyan2007; Warriner, Reference Warriner2007; Zainol, Reference Zainol2013). We address this gap by developing a conceptual model to guide research into EO in Indigenous communities. We do so by exploring the dimensions of EO from the perspective of Māori entrepreneurs, the Indigenous people of New Zealand. Taking this approach is significant as Indigenous communities around the world view entrepreneurial activity as central to the achievement of socioeconomic goals and nation rebuilding (Robinson & Ghostkeeper, Reference Robinson and Ghostkeeper1987, Reference Robinson and Ghostkeeper1988; Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, & Honig, Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004; Anderson, Dana, & Dana, Reference Anderson, Dana and Dana2006; Anderson, Honig, & Peredo, Reference Anderson, Honig and Peredo2006). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify key dimensions of Indigenous entrepreneurial orientation (InEO) and to understand how these components influence entrepreneurial behaviour. Although there are limited explorations of EO in extant Indigenous entrepreneurship literature (Swinney & Runyan, Reference Swinney and Runyan2007; Sabah, Carsrud, & Kocak, Reference Sabah, Carsrud and Kocak2014), the nature of EO in an Indigenous community context remains poorly understood.

Most EO studies adopt a Western-centric approach to entrepreneurship (what does this mean – what are its characteristics [value and context neutral – not allowing for diversity), ignoring Indigenous worldviews, including how Indigenous people perceive and relate to the entrepreneurial ecosystem [Swinney & Runyan, Reference Swinney and Runyan2007; Zainol, Reference Zainol2013] – what does this mean – Indigenous worldviews are more holistic, relational, etc.). To address this oversight, we propose a culturally constituted concept, namely an InEO, which we explore in the context of Māori entrepreneurs. We do not claim universality in our conceptualisation of an InEO; rather our intention is to illustrate through difference a culturally specific alternative to the exploration and understanding of EO.

It is keenly debated by Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers that sociocultural context matters for entrepreneurship and research, especially within an Indigenous context (Bishop & Glynn, Reference Bishop and Glynn1999; McNatty & Roa, Reference McNatty and Roa2002; Tapsell & Woods, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008a, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008b; Overall, Tapsell, & Woods, Reference Overall, Tapsell and Woods2010). Much of the debate centres on the notion of ‘context’ and how it is conceived of and empirically explored in accounting for organisational, collective or individual cultural distinctiveness (Tapsell & Woods, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008a, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008b; Ruwhiu & Cone, Reference Ruwhiu and Cone2010; Jack, Zhu, Brannen, Prichard, Singh, & Whetten, Reference Jack, Zhu, Brannen, Prichard, Singh and Whetten2013). For Indigenous entrepreneurship and especially Maori entrepreneurship theory, it is important to understand the contextual specificity in which Indigenous entrepreneurs are embedded. This will lead to a more consolidated view of EO in an Indigenous context. One of the few empirical studies of EO among Indigenous communities was conducted by Swinney and Runyan (Reference Swinney and Runyan2007), who compared Native American and ‘majority’ (non-Indigenous) entrepreneurs’ EOs. The study found few differences between the two groups. However, the research utilised scales derived from non-Indigenous studies of EO. In contrast, our study does not assume that a Western view of EO will be applicable in an Indigenous context.

Therefore, we specifically address the research question of: ‘what is an Indigenous view of entrepreneurial orientation’. We do so by exploring how Māori entrepreneurs understand and enact the five dimensions of EO. This article reports on the interview responses of 12 Māori entrepreneurs with business between 0 and 3 years in New Zealand who were asked how their Indigenous worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem influenced their perception of EO. Our contribution is an understanding of EO that is enriched by giving weight to the contextualised processes and relations of social and cultural exchange that are specific to the wisdoms of non-Western worldviews, in this instance an Indigenous Māori worldview. We suggest that understanding the dynamics of InEO has much relevance to contemporary business and society within the New Zealand context, which in turn has broader implications for the development of context and value-rational understandings of EO and entrepreneurship more generally around the world. The paper is organised as follows. To begin with, we construct a conceptual model of InEO based on a review of the Māori entrepreneurship and EO literature. We then outline the research design and method used to guide our study. The results are then presented, followed by a discussion of the implications for policy, practice and theory. The paper concludes with suggested areas of future research.

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial orientation

Previous research in Western contexts confirms strong links between EO and new business (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess2001; Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009; Kreiser, Marino, Dickson, & Weaver, Reference Kreiser, Marino, Dickson and Weaver2010; Pearce, Fritz, & Davis, Reference Pearce, Fritz and Davis2010). Earlier studies explored the strategic practices of innovative individuals (e.g., Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1973; Khandwalla, Reference Khandwalla1977; Miller, Reference Miller1983). EO is commonly defined as ‘a set of distinct but related behaviours that have the qualities of innovativeness, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, risk-taking, and autonomy’ (Pearce, Fritz, & Davis, Reference Pearce, Fritz and Davis2010: 219). There has been some debate as to whether EO is attitudinal or behavioural (Voss, Voss, & Moorman, Reference Voss, Voss and Moorman2005; Pearce, Fritz, & Davis, Reference Pearce, Fritz and Davis2010; Miller, Reference Miller2011; Moruku, Reference Moruku2013; Anderson, Kreiser, Kuratko, Hornsby, & Eshima, Reference Anderson, Kreiser, Kuratko, Hornsby and Eshima2014; Kollmann & Stöckmann, Reference Kollmann and Stöckmann2014), or both (Stambaugh et al., Reference Stambaugh, Martinez, Lumpkin and Kataria2017). This study takes the position that EO encapsulates both attitudinal and behavioural aspects (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Kreiser, Kuratko, Hornsby and Eshima2014) because sociocultural factors in an Indigenous context could lead to proclivities or behaviour. This assumption is justified in the modelling of an Indigenous view of EO later on in this section.

Figure 1 depicts two commonly held views of EO. As a unidimensional construct, the dimensions of innovation, risk-taking and proactiveness are predicted to covary (Covin & Slevin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991; Mthanti & Ojah, Reference Mthanti and Ojah2017). That is, all three dimensions must be present to infer EO. If some dimensions are missing, then a firm is not considered entrepreneurial (Zahra & Covin, Reference Zahra and Covin1995; Marino, Strandholm, Steensma, & Weaver, Reference Marino, Strandholm, Steensma and Weaver2002; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005; Poon, Ainuddin, & Junit, Reference Poon, Ainuddin and Junit2006; Dai, Maksimov, Gilbert, & Fernhaber, Reference Dai, Maksimov, Gilbert and Fernhaber2014). Conversely, the multidimensional view posits that EO dimensions vary independently. That is, environmental and organisational factors are likely to alter each dimension over an organisation’s lifecycle (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996). The antecedents for each dimension are also likely to vary in different environments.

Figure 1 Entrepreneurial orientation perspective

Innovation is at the heart of entrepreneurship and the proclivity to innovate is often considered the first dimension of the EO concept. Innovation may result in new or modified goods, services, technologies, processes or administrative structures (Hult, Hurley, & Knight, Reference Hult, Hurley and Knight2004). Innovation that replaces an existing product, process or structure reflects the Schumpeterian view of ‘creative destruction’. In support of the multidimensionality view, Hughes and Morgan (Reference Hughes and Morgan2007) conclude that innovativeness and proactiveness have the most influence on performance at the embryonic stage of a firm. This implies that firms may display different dimensions of EO at different stages of development and when faced with varying environmental conditions (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess2001).

Proactive firms seek new market opportunities, develop future goods or services and are more likely to enjoy first-mover advantages. The earlier view was that proactive firms were the first to initiate innovations (Miller, Reference Miller1983). However, a proactive firm may stay ahead of competitors by adjusting and improving existing products and services (Kollmann & Stöckmann, Reference Kollmann and Stöckmann2014). Businesses that do not actively engage in identifying emerging markets and changing customer needs are also likely to be less innovative (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Pérez-Luño, Wiklund, & Cabrera, Reference Pérez-Luño, Wiklund and Cabrera2011; Kollmann & Stöckmann, Reference Kollmann and Stöckmann2014).

Studies of EO at the firm-level define risk-taking as the commitment of resources to projects where the outcomes are unknown and where organisations are willing to deviate from the known to the unknown (Covin & Slevin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991; Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Mueller & Thomas, Reference Mueller and Thomas2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005). Risk-taking and proactiveness influence adoption of innovative practices driven both internally and externally to the firm (Pérez-Luño, Wiklund, & Cabrera, Reference Pérez-Luño, Wiklund and Cabrera2011; Kollmann & Stöckmann, Reference Kollmann and Stöckmann2014). However, organisational and environmental factors mediate the links between risk-taking and performance (Lumpkin and Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996).

Autonomy has been defined as the ‘independent action of an individual or a team in bringing forth an idea or a vision and carrying it through to completion’ (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996: 140). The freedom to exercise one’s own initiative is also seen as an entrepreneurial antecedent (Lumpkin, Cogliser, & Schneider, Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009). An element of autonomy is present in every entrepreneurial act because individuals have to exercise initiative when making business decisions, such as new product development through entrepreneurial teams that can create a competitive edge (Lumpkin, Cogliser, & Schneider, Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009).

Competitive aggressiveness has been defined as a ‘firm’s propensity to directly and intensely challenge its competitors to achieve entry or improve position, that is, to outperform industry rivals in the marketplace’ (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996: 148). An alternative view is that proactiveness is directed towards opportunities that others have not discovered, whereas competitive aggressiveness is a response to the activities of competitors who are exploiting current opportunities. A firm’s level of aggressiveness – whether aimed at exploiting new opportunities or responding to competitors – is likely to be influenced by company lifecycle stage, market environment, current performance levels (Covin & Slevin, Reference Covin and Slevin1989; Covin & Covin, Reference Covin and Covin1990; Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005) and strategic marketing aims (Knight, Reference Knight2000).

The EO dimensions discussed above are Western in their ontological and epistemological assumptions. Missing is a conceptualisation of EO that will take contextual factors, such as lived experiences, oral stories, traditions and Indigenous knowledge systems into account. Thus, in the following sections, we review the field of Maori entrepreneurship, highlighting the distinctive sociocultural context that drives definition and business practices. Then we present our model of InEO and discuss the antecedents that are likely to influence Māori perceptions of EO.

Māori entrepreneurship

Indigenous entrepreneurship has been defined as enterprise-related activities carried out by Indigenous people for the benefit of Indigenous people (e.g., Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle and Lansdowne2005; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2005). The Indigenous entrepreneur is not self-oriented but focussed on creating benefits for their community as they seek to preserve their culture and gain control of their future (Peredo & Anderson, Reference Peredo and Anderson2006). Different Indigenous communities may undertake various economic activities, but the practices and organisational cultures are essentially based on their worldview, which could be community-oriented or purely commercial and self-determining. This assertion is corroborated by recent studies indicating that embedding Indigenous values in community-led corporation aligned with concepts and mission of social entrepreneurship (Curry, Donker, & Michel, Reference Curry, Donker and Michel2016). Indigenous entrepreneurs often seek to preserve their cultures and control their futures (Peredo & Anderson, Reference Peredo and Anderson2006; Henry, Reference Henry2017).

Māori worldview is anchored and deeply rooted in the spiritual realm. There are different myths on creation in Māori mythology. The common line of thought is on Rangi (Sky Father) and Papatuanuku (Earth Mother) whakapapa on how the world came to be based on the Lo tradition (Irwin, Reference Irwin1984; Walker, Reference Walker2003). The account of how creation came by Irwin (Reference Irwin1984) portrays a sequence of events that led to the eventual creation of a natural world based on Māori mythology. Thus, the natural world, which includes plants, animals and humans, are the results of the activities of the offspring of Rangi and Papa who desired to see the light.

In Te Ao Māori, this illustration shows that humans are related to the natural environment because they both evolved from Rangi and Papa. Kaitiakitanga (stewardship, guardianship) is directly related to this account as it reckons with the need to use the natural resources as guardians and stewards. Marsden (Reference Marsden2003) captures Kaitiakitanga in a more detailed way. He suggested that stewardship is a wrong word to use as it connotes guarding another’s property. He notes that Kaitiaki is ‘a guardian, keeper, preserver, conservator, foster–parent, protector’ (Marsden, 2003: 67). This creates a special relationship between Māori and the mother earth—Whenua because they all evolved from Rangi and Papa.

Māori entrepreneurship refers to the process through which individual or group of Māori descent engage in enterprise-related activities within Māori or non-Māori enterprise (Mika, Reference Mika2016). Māori entrepreneurship, as a distinctive form of Indigenous entrepreneurship, has been the focus of some studies (Barcham, Reference Barcham1998; Frederick & Henry, Reference Frederick and Henry2003; Reihana, Sisley, & Modlik, Reference Reihana, Sisley and Modlik2007; Warriner, Reference Warriner2007; Bargh, Reference Bargh2012). Henry argues, ‘Māori entrepreneurship has a long history, is founded on Māori culture and values, is collective in nature and must be understood within its socio-cultural context’ (Reference Henry2017: 27). Recently, there has been growing concern about the need to protect culturally derived intellectual property when entrepreneurs commercialise certain goods and services (Riley, Reference Riley2004; Stabinsky & Brush, Reference Stabinsky and Brush2007). In addition, sustainability, particularly the need to preserve natural habitats and food sources, is also an important aim (Posey & Dutfield, Reference Posey and Dutfield1996).

Although there is no single definition of a Māori business, common attributes of Māori entrepreneurship are based on identity, people or cultural immersion in business (Durie, Reference Durie2003; Spiller, Pio, Erakovic, & Henare, Reference Spiller, Pio, Erakovic and Henare2011). Both authors also suggest that Māori businesses predominantly adopt kaupapa Māori concepts and practices that tend to be influenced by cultural values, including the promotion of family (whanau), subtribal (hapū) and tribal (iwi) welfare (Warriner, Reference Warriner2007), self-determination (Durie, Reference Durie2003) and the development and preservation of intergenerational wealth (Semyonov & Lewin-Epstein, Reference Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein2013). Aspiring Māori entrepreneurs face a number of challenges. These include limited access to business development funding (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2013) and mentoring (Hook, Waaka, & Raumati, Reference Hook, Waaka and Raumati2007). However, how these cultural context and attributes influence and impact on entrepreneurial proclivities is unknown.

Māori culture is dynamic because their perception and view of the world is influenced by their cultural values and for those who associate with their culture in business. Māori ownership, control and cultural influence on decision-making and approach to management are key factors that differentiate Māori from non-Māori in business (Mika, Reference Mika2016). Interestingly, non-Māori enterprises perceive the benefits of adopting Māori culture within the context of Māoriness as a component of the essence of New Zealand, as a tangible and useful resource, point of differentiation, credibility and an asset (Jones, Gilbert, & Morrison-Briars, Reference Jones, Gilbert and Morrison-Briars2005). Keelan and Woods (Reference Keelan and Woods2006) argued for the need to recognise the role of Māori traditional stories such as Māui-tikitiki-a-Tāranga presented as ‘Māuipreneur’ in Māori entrepreneurship. The metaphor of associating the exploits of Māui with entrepreneurship accentuates this ancient story and offers a link for research into the various ways entrepreneurial traits were demonstrated by Māori ancestors. Māoriness and customs are recognised as what sets Māori entrepreneurship apart from other forms of entrepreneurship (Harmsworth, Reference Harmsworth2005; Jones, Gilbert, & Morrison-Briars, Reference Jones, Gilbert and Morrison-Briars2005; Te Puni Kōkiri, 2007; Davies, Reference Davies2011). Awareness of the stories of entrepreneurial exploits from Māori ancestors exemplifies the fact that entrepreneurship growth in contemporary Māori is continuously evolving. The entrepreneurial spirit demonstrated by Māori ancestors is embodied in the culture and beliefs as exemplified by the cultural values such as tino rangatiratanga because it accentuates the drive for self-autonomy and ability to determine economic, social and cultural issues.

Addressing Māori and non-Māori, entrepreneurs is more than identity but it is the contextual factors such as management approach, ownership structures and business values that create the in-between space rather than a binary or dualities. This study focusses on how Māori entrepreneurs perceive and demonstrate EO. Within Māori communities, entrepreneurial activity tends to be culturally oriented, influencing the perception of opportunity and risk (Tapsell and Woods, 2010). Thus, it is likely that Indigenous worldviews and sociohistorical factors will also affect Māori perceptions of concepts, such as EO. Although it is probable that a strong EO may help the founders and owners of new business ventures to overcome these hurdles, there has been little research to establish what a Māori perspective of EO might be or how it might influence business behaviours. This is explored under the section ‘Modelling and an Indigenous view of EO’.

Modelling an Indigenous view of EO

It is generally agreed that contextual factors influence EO (Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005; Stettler, Shirokova, Bogatyreva, & Baldauf, Reference Stettler, Shirokova, Bogatyreva and Baldauf2014). Previous research suggests that different cognitive processes influence EO, opportunity recognition, start-up motivation, self-efficacy and network participation of Indigenous enterprises (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004). Recent studies affirm that social norms and societal culture influence the prediction of entrepreneurial behaviours in collectivist societies (Siu & Lo, Reference Siu and Lo2013; Semrau, Ambos, & Kraus, Reference Semrau, Ambos and Kraus2016). These assertions are clear indications that EO in a collectivist society such as Māori would be perceived differently due to norms and the beliefs that are predominant in the culture. Therefore, adopting the views of Māori entrepreneurs provides a platform for considering how Indigenous worldview could influence the perception of EO. At the same time, Māori entrepreneurs are operating within an entrepreneurial ecosystem specific to New Zealand that involves government policy, etc. Upon gaining insight into their view, predicting EO can be explored further to gain more insights on the factors that could lead to manifestation of entrepreneurial behaviours. Note that in our initial model we have included the five most common Western-derived dimensions of EO discussed in the previous section. However, how these dimensions are perceived by Māori entrepreneurs, whether some dimensions should be modified or deleted and/or others included in an Indigenous view of EO, was not determined until after we conducted our study. Therefore, the discussion in this section is developing the conceptual model.

Worldview

The influence of Indigenous cultural values and beliefs on entrepreneurship concepts has been neglected (Curry, Donker, & Michel, Reference Curry, Donker and Michel2016). However, there has been increased attention on how cultural values derived from distinctive worldviews has influenced firm performance (Siu & Lo, Reference Siu and Lo2013; Saeed, Yousafzai, & Engelen, Reference Saeed, Yousafzai and Engelen2014; Semrau, Ambos, & Kraus, Reference Semrau, Ambos and Kraus2016). Worldview influences how Indigenous organisations make and execute strategic choices and manage resources (Posey & Balée, Reference Posey and Balée1989; Finlay, Reference Finlay2011). Hence, Māori worldview stands at the core of exploring how Māori entrepreneurs perceive EO. Worldview can be defined as the values and beliefs that shape how people relate to the world around them (Koltko-Rivera, Reference Koltko-Rivera2004; Hart, Reference Hart2010). The worldviews of Indigenous entrepreneurs also reflect their histories as well as present conditions (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004). In order to understand how Māori worldview influences Māori entrepreneur’s perception of EO, it is vital to grasp the major features within Māori worldview that are woven into Māori existence.

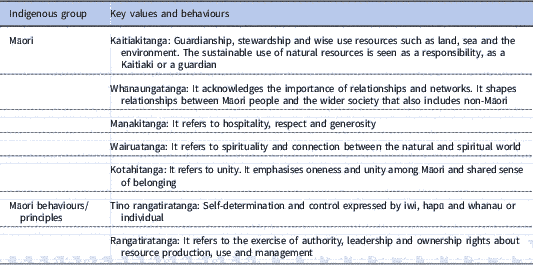

Māori worldview is profoundly rooted in the spiritual realm and the ethical rules that existed before European colonisation (Mead, Reference Mead2012). However, in the 200 years since colonisation, Māori worldview has bridged contemporary and traditional knowledge (Doherty, Reference Doherty2012). According to Henare, ‘worldview, values, ethics, morals, and associated cultural practices are integral components of Māori ancestral legacy that preserve both unity and identity with roots in and continuity with the past’ (Reference Henare2001: 201). An interwoven perspective of life is evident among Māori who integrate customary practices and values in modern businesses (Harmsworth, Reference Harmsworth2005; Reihana, Sisley, & Modlik, Reference Reihana, Sisley and Modlik2007; Haar & Delaney, Reference Haar and Delaney2009; Te Puni Kōkiri, 2013). Table 1 shows some key values within Māori culture that help shape worldview and which may influence EO and related business practices.

Table 1 Māori values and behaviours

Māori knowledge is closely related to the daily lives of people, stories and experiences passed down from generations. For example, within Māori worldview the concept of whanaungatanga acknowledges the importance of relationships and networks and may be exemplified by the contributions of family members to different areas of a business (Haar & Delaney, Reference Haar and Delaney2009). Community social capital refers to the ability to access resources within one’s community as a result of trustworthiness and voluntary organisational membership (Kwon, Heflin, & Ruef, Reference Kwon, Heflin and Ruef2013). Social capital can also extend beyond one’s immediate family and community. For example, Māori entrepreneurs often network across cultures and may view business networks as extensions of their cultural networks (Foley, Reference Foley2010) to which they are accountable.

In New Zealand, self-employment is a popular means of attaining self-determination (De Vries & Shields, Reference De Vries and Shields2006). In an Indigenous context, self-determination includes rights to nationhood, autonomy and the opportunity to leverage land (Mörkenstam, Reference Mörkenstam2005; Broderstad, Reference Broderstad2010). Napoleon (Reference Napoleon2005) suggested that individual self-determination is required to promote collective self-determination among Aboriginals in Australia. However, as with the cultural values outlined in Table 1, there is a lack of empirical evidence of how these aspects of Māori worldview influence perceptions of EO and associated practices of Māori business owners.

Entrepreneurial ecosystem

The notion of entrepreneurial ecosystem is a burgeoning area in Māori entrepreneurship gaining focus within private sectors with recent reports such as BERL, Maui Rau and Chapman Tripp reports on Māori economy. This development shows that entrepreneurial ecosystem is increasingly becoming important in shaping Māori entrepreneurship. Recent reports by Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2015) show that entrepreneurial behaviour among Māori entrepreneurs is imbalanced as some parts of the country have more entrepreneurialism than other parts of the country.

The notion of ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’ may facilitate this, as it emphasises the individual and collective sets of characteristics that position the process of entrepreneurship that occurs within a community of interdependent actors (Isenberg, Reference Isenberg2010; Zahra & Nambisan, Reference Zahra and Nambisan2012; Stam, Reference Stam2015). Although there is no exact formula for the creation and sustenance of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Isenberg, Reference Isenberg2010), there are several attributes that are considered to be influential, including system leadership, intermediaries/mentors, network density, talent, support services and local/national government support (Stam, Reference Stam2015).

Researchers of entrepreneurial ecosystems also acknowledge the role of entrepreneurs themselves as important players in setting the strategy of the enterprise and influencing its interaction with the ecosystem (Stam, Reference Stam2015). This would include the adoption of advanced managerial practices highlighting a clear need for appropriate levels of training and business education to advance and sustain managerial capability in small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Ates, Garengo, Cocca, & Bititci, Reference Ates, Garengo, Cocca and Bititci2013). The unique characteristic of SMEs, specifically as an entity with limited resources and specialist expertise, draws the attention to a deficit of approaches ‘to strategy development and implementation, the role of the owner/manager and the absence of formalised HR policies and practices’ (Darcy, Hill, McCabe, & McGovern, Reference Darcy, Hill, McCabe and McGovern2014: 402). These areas of concern facing SMEs in terms of performance are reflected in issues raised by Māori SMEs. Major concerns for Māori businesses are people-related, including succession issues and access to skilled staff. In addition, issues such as a lack of capital/access to funding, balancing family and business interests and access to expertise are also the areas of concerns (ANZ Bank, 2015). The importance of understanding the different stages of small business growth and anticipating critical requirements can aid managers and owners in navigating the relationships between organisational lifecycle, competitive strategy and performance (Churchill & Lewis, Reference Churchill and Lewis1983; Lester, Parnell, & Carraher, Reference Lester, Parnell and Carraher2003; Tam & Gray, Reference Tam and Gray2016).

Entrepreneurial ecosystem are factors that emerge in different parts of the ecosystem with specific assets (Mason & Brown, Reference Mason and Brown2014). Isenberg (Reference Isenberg2011, Reference Isenberg2014) outlined six different aspects of the ecosystem, but three out of that domain make up this second theme: government policy, economic (finance) and opportunities (markets). Entrepreneurship development policies appear to have had limited success in improving the rates of new business creation by Indigenous entrepreneurs (Buultjens, Waller, Graham, & Carson, Reference Buultjens, Waller, Graham and Carson2005; Hindle, Reference Hindle2005; Harmsworth, 2006; Rante & Warokka, Reference Rante and Warokka2012; Shoebridge, Buultjens, & Peterson, Reference Shoebridge, Buultjens and Peterson2012). It is argued that the ‘direct actions or inactions of governments will influence the conditions for entrepreneurship’ (Lee & Peterson, Reference Lee and Peterson2000: 408). This assertion is confirmed by a recent study that indicates that the entrepreneurial ecosystem in New Zealand does not create enough room for Māori-owned SMEs to emerge and flourish (Hanita, Rihia, & Te Kanawa, Reference Hanita, Rihia and Te Kanawa2016). This indicates a tension between the New Zealand Government’s business development policies and the needs of Māori entrepreneurs. In addition, low economic status often restricts Indigenous entrepreneurs’ access to business finance (Foley, Reference Foley2006a, Reference Foley2006b; Furneaux & Brown, Reference Furneaux and Brown2007) that then hampers business operations and growth (Zapalska, Perry, & Dabb, Reference Zapalska, Perry and Dabb2002; Mapunda, Reference Mapunda2007).

On a more positive note, opportunities increasingly transcend local and regional boundaries, and Indigenous people are more involved in the global economy (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004; Anderson, Dana, & Dana, Reference Anderson, Dana and Dana2006; Anderson, Honig, & Peredo, Reference Anderson, Honig and Peredo2006). Davidsson’s (Reference Davidsson2015) conceptualisation of entrepreneurial opportunity may help explain why some Indigenous people pursue new economic activities while others do not, despite being faced with similar external enablers, cultural values and beliefs. Davidsson (Reference Davidsson2015) argues that differing resources, commitments, aims and/or timing issues may influence go/no go decisions. Individual entrepreneurs may also have varying interpretations on the attractiveness of a potential new venture opportunity (Sarason, Dean, & Dillard, Reference Sarason, Dean and Dillard2006; Sarason, Dillard, & Dean, Reference Sarason, Dillard and Dean2010). Acknowledging these three factors within the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the exploration of EO can contribute to a better understanding of entrepreneurialism among Māori entrepreneurs.

InEO

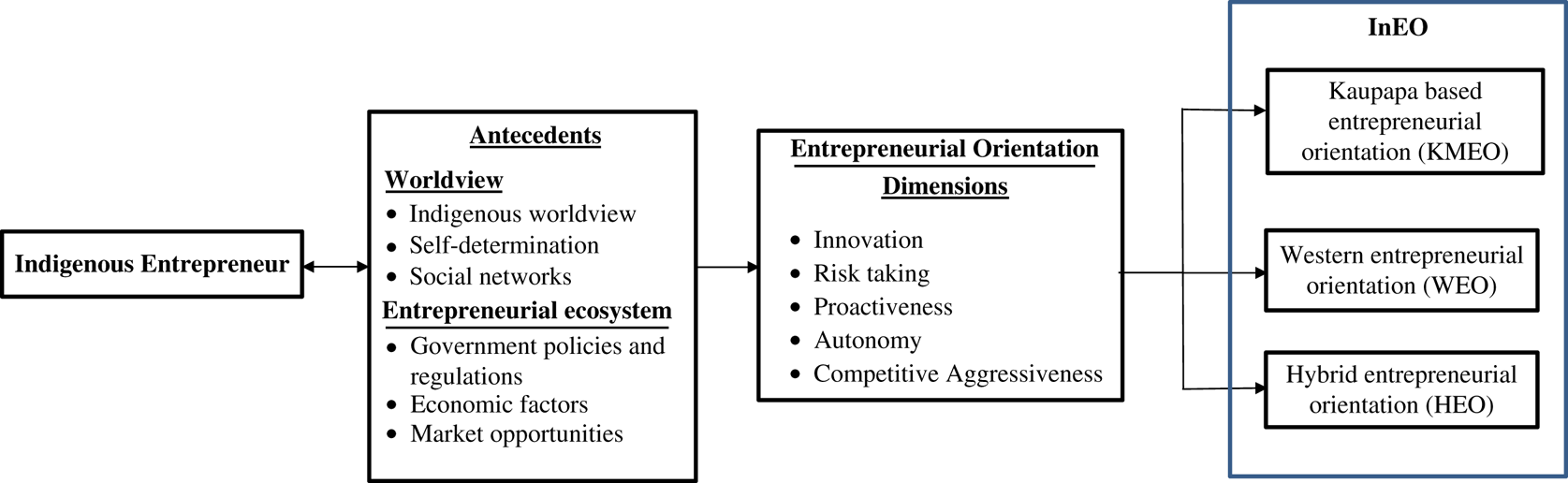

Based on the theoretical framework presented earlier, Figure 2 illustrates how Indigenous entrepreneurs’ worldviews (Kawagley, Norris-Tull, & Norris-Tull, Reference Kawagley, Norris-Tull and Norris-Tull1998; Thaman, Reference Thaman2003; Durie, Reference Durie2005; Cheung, Reference Cheung2008) and entrepreneurial ecosystems (Isenberg, Reference Isenberg2010, Reference Isenberg2011, Reference Isenberg2014) are likely to be the key influences on the nature and consequences of InEO. These three typologies were developed based on the literature review and the notion that context matters for entrepreneurship (Overall, Tapsell, & Woods, Reference Overall, Tapsell and Woods2010; Welter, Reference Welter2011). For a culturally constituted EO, culture and community interest are likely to be at the core of decision-making and business practice. The heterogeneity evident among Indigenous cultures suggests that Indigenous entrepreneurs will adopt different cultural values in their business practices. The decision-making processes and behaviours that infer the presence of EO will be influenced by the cultural norms, beliefs and personal values of the entrepreneur who demonstrates a culturally constituted EO. This assertion is corroborated by the recent conclusions drawn by Curry, Donker, and Michel (Reference Curry, Donker and Michel2016) that increased awareness of Indigenous worldviews among First Nations is leading to community development models that focus less on individualism and Western values. Hence, the first proposition suggests that:

Proposition 1:Indigenous worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem will influence Indigenous entrepreneurs who are culturally aware, leading to a more culturally inclined EO where decisions and business practices are based on cultural values and beliefs.

Figure 2 Initial conceptual model of Indigenous entrepreneurial orientation

A Western entrepreneurial orientation (WEO) may not negate cultural values, but the predominant business practices and decision will be anchored on Western business practices. A WEO reflects the aspects of a Western economic perspective of EO where the emphasis is on business growth and performance (Avlonitis & Salavou, Reference Avlonitis and Salavou2007; Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009; Andersén, Reference Andersén2010; Craig, Pohjola, Kraus, & Jensen, Reference Craig, Pohjola, Kraus and Jensen2014). Existing studies show that some urban Indigenous Australians had relinquished elements of cultural value consciously from business interactions (Foley, Reference Foley2006b). The motive behind these was linked to operating among the predominant culture.

Other reasons will also include accessing markets, posterity, control and the desire for a better life. Based on the empirical findings, Foley (Reference Foley2008) concluded that urban Indigenous Australians aligned with the dominant culture as a way to access their markets, take control of their actions, have a positive attitude to succeed and have a strong desire to provide a better life for their children and members of their wider family. Interestingly, Foley (Reference Foley2008) noted that 64% of Indigenous entrepreneurs surveyed ventured into the business by recognising, seizing opportunities and networking. Networking enhanced the Indigenous entrepreneur’s success and survival (Paige & Littrell, 2002 cited in Foley, Reference Foley2008).

Proposition 2:Indigenous worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem will influence Indigenous entrepreneurs who are not only culturally aware but are also Western inclined leading to a more Western inclined EO.

The fact that not all Indigenous entrepreneurs act the same way or have the same cultural inclination creates a third view called the hybrid. From a hybridity, postcolonial theory is a combination of cultural values with Western values, in this case business strategies. For example, the Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corporation in British Columbia promotes their cultural heritage through their ventures, which include a winery, ski resorts and a golf course (Camp, Anderson, & Giberson, Reference Camp II, Anderson and Giberson2005). However, there can be conflicts between tourism, traditional land uses and cultural activities. For example, some Swedish Sámi believes that tourism and ski resorts encroach on grazing land and commoditise their culture and heritage (Kvarfordt, Sikku, Teilus, Crofts, & Svensk Information, & National Sámi Information Centre Sweden, Reference Kvarfordt, Sikku, Teilus and Crofts2005; Müller & Huuva, Reference Müller and Huuva2009). Hence, altering Western view of business and aligning with predominant cultural values such as preserving heritage show that what could be an opportunity for one Indigenous community can be considered as undermining the cultural wealth of the group. Thus, creating a balance in social and profitability goals within Indigenous contexts will become increasingly important where there are different values set on what is most important within the community (Barba-Sánchez & Molina-Ramírez, Reference Barba-Sánchez and Molina-Ramírez2014; Curry, Donker, & Michel, Reference Curry, Donker and Michel2016).

Proposition 3:The demands of culture and need to be economically viable will influence how worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem is perceived by Indigenous entrepreneur leading to a hybridised view of EO.

Method

A qualitative research method was adopted to gain insights into how Indigenous entrepreneurs perceive and enact EO. Qualitative approaches have been described as best when we want to explore and understand social reality, where little is currently known, or we want to explore pertinent questions in different contexts (Rossman & Marshall, Reference Rossman and Marshall2010; Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). Therefore, addressing the research question of ‘what is an Indigenous view of entrepreneurial orientation’? − lend themselves to an interpretive–explorative research approach.

Research design

We elicited participants’ lived experiences and opinions about Māori worldview and the New Zealand entrepreneurial ecosystem. This is consistent with the open and conversational style of interviews recommended for collecting qualitative data in Indigenous contexts (Kovach, Reference Kovach2010). Open conversation style of interview encourages researcher to approach interviews as conversation in line with storytelling often used as a method of obtaining knowledge in Indigenous context. Fraser (Reference Fraser2004) asserts that culturally pervasive stories are an essential element for creating meaning and that narrative analysis provides a credible means for producing knowledge from this type of data. An approach that draws narrative from interviews is common in research with Māori communities (Bishop, Reference Bishop1996; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Haami, Benton, Satterfield, Finucane, Henare and Henare2004) and enables researchers to take into account the sociocultural systems of relationships, historic circumstances and current practices that may influence the topic being studied (Clandinin & Connelly, Reference Clandinin and Connelly2000; Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2001). Thus, a conversational approach provides a suitable forum for Indigenous peoples to construct their accounts of practices, historical events and exchanges (Ruwhiu & Cone, Reference Ruwhiu and Cone2010) and is appropriate for the current study.

Participants and sampling

From a wider study comprising 31 Māori entrepreneurs who were contacted via LinkedIn and email, 12 participants were selected. The criterion for sampling was based on identity – Māori-owned businesses that had been operating between 0 and 14 years. We purposively selected 12 owners of a variety of new commercial ventures (operating for 3 years or less) for the current study out of the 31 participants to explore InEO at the early stage of business development. Subsequent studies can build on this and consider InEO at later stages of the business cycle. The owners identified their enterprises as ‘Māori businesses’. That is, owned by the people of Māori descent who acknowledged that their cultural heritage had some influence on their management decisions. We are interested in the perceptions of owners of new ventures, rather than established enterprises, for this paper as new firms are usually smaller and therefore more likely to display an EO (Nason, McKelvie & Lumpkin, Reference Nason, McKelvie and Lumpkin2015). Various industry sectors are represented, although most firms are service-based (the most common being consulting), and most of the interviewees were male (see Table 2). Pseudonyms are used to ensure anonymity; participants with Māori names have Māori pseudonym and English pseudonym for those with English names.

Table 2 List of participants

ICT = information and communication technology.

The limited number of interviews used in this study is acceptable, given that we are dealing with a relatively homogenous group (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006) regarding their cultural heritage and occupation.

Data collection and analysis

The interviews were conducted in an open-structured conversation style (Kovach, Reference Kovach2010). Open-structured conversations allow participants to share their thoughts more freely. Four of the interviews were held face-to-face, and the other eight were conducted via telephone, Skype or Zoom software. The interviews ranged from 1 to 2 h.

The first author transcribed the interviews and copies were sent to participants for validation. Thematic analysis of the narratives was then conducted (Fraser, Reference Fraser2004; Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Table 3 depicts the process of organising the data into initial themes, simplified themes and thematic categories.

Table 3 Thematic development from analysis of narratives

The simplified themes are themes that were identified from the textual data of participants. These themes were numerous because participants used synonyms when responding to questions on their cultural values. Therefore, in analysis, the simplified themes were constructed using similar words that captured the initial themes. All references to beliefs, customs and values were categorised as cultural values and practices. The thematic category shows the antecedents that informed the conceptual model and how they relate to the initial and simplified themes. This combination is beneficial when we want to use the themes in exploring individual, interpersonal, cultural and structural aspects of the participant’s story. This gives a basis for ascertaining how the participants viewed EO. Thus, the narratives are focussed on analysing the conversation and dialogue between the researcher and the interviewee.

Results

InEO

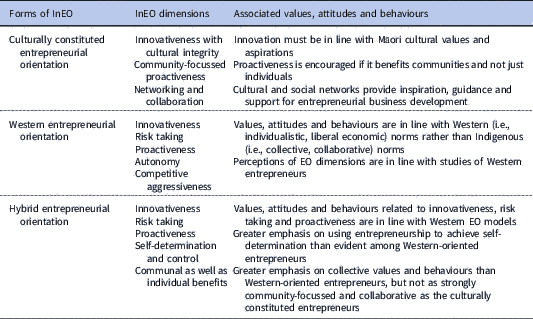

In general, participants in this study demonstrated an understanding of EO. However, EO is enacted differently to the way that it is usually depicted in studies undertaken in Western contexts. In fact, we discovered three distinct forms of InEO. Based on the interpretation of the participant narratives of the participants, three EO were identified as possible continuum. This suggests that some participants are more or less oriented to one or the other but does not send signals about whether or not a business is Māori ‘enough’. Figure 3 shows the modified conceptual model shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3 Indigenous entrepreneurial orientation (InEO) model based on findings

The first typology is a kaupapa Māori EO reflecting a culturally oriented EO. The phrase reflects a predominant Māori way of doing business. These entrepreneurs are more likely to focus on cultural values, beliefs and customs when making decisions and setting goals. The second form of InEO reflects a W EO that includes the sorts of values, goals, strategies and practices commonly taught in business schools. The third form is a hybrid orientation where entrepreneurs combine Indigenous cultural values with Western business practices, creating an ‘in-between’ space (Bhabha, Reference Bhabha1996; Frenkel & Shenhav, Reference Frenkel and Shenhav2006).

Kaupapa Māori EO

A kaupapa Māori EO articulates the values, attitudes and business practices of participants in this study who are strongly influenced by a Māori worldview. It is a culturally constituted form of EO. One of the interviewees, Apera, said he was culturally oriented in his business approach because his intention is to provide a platform for his hapū (subtribe) to be economically empowered. Benjamin shared similar aims and explained how worldview influenced his intentions: ‘It is about knowledge of my culture, language, identity, and knowledge [that] has enabled me to have another view of our world to the dominant Western image presented to us’. Adopting a more culturally constituted EO is also evident in service delivery. Anthony said: ‘Māori cultural values might not necessarily be obvious in the output, but it is in the input’. Underlying these narratives is the fact that business decisions will be influenced by this approach where cultural values that revolve around whānau ora becomes a baseline. For Benjamin, expressing a culturally constituted EO is encapsulated by language, identity and culture. These different elements are critical aspects that influence business decision and practices.

Integrating cultural values into business also influences other aspects of EO such as innovation, risk-taking, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness. When asked to define EO dimensions (innovation, risk-taking and competitiveness), it appears that neoliberal policies negate entrepreneurialism among Māori (Frederick & Henry, Reference Frederick and Henry2003). In answering the question above, Hine’s response was ‘I am trying to stick with innovation with an integrity base, a base Māori people intended’. Benjamin also said, ‘If it is not new…it is transactional…the mindset is the fact that we have been colonised so much and many of our whānau have lost sight of our culture and language and those elements’. Innovation with integrity is reflected in the views of Benjamin and Hine whom both work in the educational sector as consultants. Both participants draw on historical factors to form their ideology of what innovation means.

The effect of this imbalance as narrated by Benjamin will be evident in business decisions of an Indigenous entrepreneur even though decision-making is not considered as purely autonomous for those involving family members such as Benjamin and Anthony who have family members as business partners. The EO of Indigenous entrepreneurs who are conscious of social-historical factors will reflect this conviction in business decisions and practices – reintegrating what they perceive as valuable to Māori and opposes their pursuit of self-determination or collective well-being. Overall, participants with predominantly kaupapa Māori EO perceived the influence of entrepreneurial ecosystem on their business practices in different ways. For example, there is quite a negative connotation associated with the current political economy that some participants reflected on. For example, Benjamin believes ‘There is a strategy by [the] government to confuse us, and when you create disillusionment for Māori people, they tend to run towards the colonising ways of doing things. They have been taught through the system especially through education and religion that the Pākehā way of doing things is far more superior [to] our ways’. Our Māori entrepreneurs who are more Kaupapa Maori entrepreneurial orientation – hold on more strongly to their Māori identity, and culture as a form of resistance and challenge to the status quo.

On a more positive note, Steve highlighted the influence of Whanau Ora, a multidisciplinary work programme jointly implemented by the Ministries of Health, Te Puni Kōkiri and Social Development. He explained, ‘Yes. Our business is built around community and family. Our business practices reflect looking after each other and strengthening each other toward accomplishing goals and aspirations’. He believed that associating with organisations who encourage family health and welfare (whānau ora) helps reinforce Māori ways of being and doing business. Steve said he does not see competitors as competitors but looks for the opportunities that can be utilised to do more for Māori whānau, changing how he views competitive aggressiveness. The concept of whānau ora, focusses on family well-being and it is connected to the idea of identity and positioning of the Indigenous entrepreneur, explained by Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2015). A stronger focus on collectivism rather than individualism was evident within the kaupapa Māori view of EO and echoes previous research in Indigenous entrepreneurship (Redpath & Nielsen, Reference Redpath and Nielsen1997; Anderson, Honig, & Peredo, Reference Anderson, Honig and Peredo2006). Benjamin affirmed this, ‘It is part of our cultural values …to create and engage and connect our people to each other’. Hine added that in Māori-owned business: ‘It is [conducted] in [a] collaborative way’. These narratives draw attention to specific cultural values, such as the concept of whanaungatanga (the importance of good family and community relationships and networks), as an underlying variable of EO. This appears to support previous research findings that Māori entrepreneurs tend to perceive their social network as an extension of their cultural network (Foley, Reference Foley2010).

In summary, the main InEO dimensions suggested by this group could be termed: innovativeness with cultural integrity; proactiveness to improve community well-being; and networking and collaboration to gain inspiration, insights, support and resources to improve entrepreneurial business development aims, strategies, practices and the resulting collective benefits.

WEO

Those with a WEO do not necessarily refute their Māori culture and heritage. Although aspects of a Māori worldview may influence entrepreneurs’ behaviour in a social context, cultural values may have limited influence in a business context. As suggested by Todd who explained, ‘There are different types of Māori, I am more city Māori. I have integrated into modern society … There are a couple of principles on how we tie ancient Māori knowledge. We convert it into today’s context’ and Tim who acknowledged ‘I am more Western, but there are times when the Māori sidekicks in’. Underlying the narrative of Todd and Tim is the fact that both entrepreneurs’ view of their culture is not entirely separated from their Western ideology, but have different ways they demonstrate cultural affinity or connectedness to Māori culture in business. For example, in his work with rural organisations, Todd often makes use of Māori analogies, even though he does not identify strongly as a Māori business. Todd believes autonomy ‘comes [from] something inside even though we work on a collective together. Inside me, I have this driving force which comes from [experience] of many social ills’. Although consensual decision-making may be the norm in Indigenous entrepreneurship due to collectiveness (Rønning, Reference Rønnning2007), this group of entrepreneurs appear to be more autonomous based on their individuality and experiences.

The idea of collectiveness does not erode the need to be competitive for this typology, but both Todd and Tim perceive autonomy and competitive aggressiveness differently and affirm that there is tendency to act as individualistic, and they uphold the need to be competitive as an Indigenous business. Participants who appear to have this EO appear to be highly competitive and actively taking steps in seeking business opportunities through competition and coopetition. Todd highlighted that they are very innovative and cutting edge because they are constantly seeking new ways to overcome challenges. Two ways they achieve this is by coopeting with other consulting firms where there is a common interest while also competing with the ‘big names’. Tim shares similar views and believes innovation, proactiveness, risk-taking, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness are equally important in business. His views affirm the argument that EO covary (Covin & Slevin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991).

Western business practices are also utilised when identifying and evaluating opportunities. As explained by Todd ‘We use entrepreneurial systems, processes, and disciplines …When we see an opportunity, and we need to change in a certain way, we will do a small test’. A balanced entrepreneurial ecosystem supports cultural inclusion, facilitates policies and leadership, provides finance and human capital, has markets for products and offers institutional and infrastructural support (Isenberg, Reference Isenberg2010). As with the kaupapa Māori entrepreneurs, the Western-oriented group admits that the entrepreneurial ecosystem in New Zealand is imbalanced. As Todd observed, ‘The current entrepreneurial ecosystem suits a different type of entrepreneur…whereas Māori… do not have the resources to take off’. This supports the findings of the industry study that indicated that Māori small business has been overlooked as a pathway to future economic development (Hanita, Rihia, & Te Kanawa, Reference Hanita, Rihia and Te Kanawa2016).

In summary, the five Western dimensions of EO − innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness − all appear to be relevant. This may be partly due to the admission by members of this group that the current environment is not conducive to the development of new ventures by Māori entrepreneurs. Instead, this group of entrepreneurs has adopted a pragmatic stance and exploited market opportunities using more Western-oriented practices. As a result, they appear to reflect more Western (i.e., individualistic, liberal economic) norms rather than Indigenous (i.e., collective, collaborative) norms. Perceptions of EO dimensions are generally in line with studies of Western entrepreneurs.

Hybrid entrepreneurial orientation (HEO)

Participants who demonstrated the in-between perspective are interpreted as having a HEO. Participants indicated a HEO. Tipene said, ‘I am probably in the middle…I am just like any other business owner. I want sustainability for my family. No matter what people say, that is what they want’. Similarly, Roland acknowledged, ‘I would say I am in the middle. I am there on purpose because I have thought deeply about that spectrum’. He believes there are advantages of such a perspective, saying, ‘The benefits of being on the cultural spectrum are connections, affiliation, spiritual, contentment, and belonging. The benefit of a Western spectrum is knowledge [technology]. What if there was a third way?’.

The purpose of the in-between position can be categorised into family well-being, cultural advantage and business knowledge. The emphasis on creating balance and also working within the culture in which the entrepreneur is embedded leads to the adoption of cultural practices. As Arana said ‘I think if we bring [Māori and Western] together we will create a powerhouse. It has to be within our values for it to be reasonable and it changes in every person. Our Māori values of looking after [whānau] is huge; we are doing it for the kids. I do not think we are doing that at the moment’. Indications of cultural bricolage that emerged in our analysis of the Western-oriented entrepreneurs appear even stronger in the hybrid group. Indiana said, ‘I categorise my business as a mainstream business [that] specialises in Indigenous clients …. However, in my business, I am authentically myself, that is a Te Arawa woman’. The above narratives appear to support earlier studies that suggest the cultures of the coloniser and the colonised often converge (Bhabha, Reference Bhabha1996; Frenkel & Shenhav, Reference Frenkel and Shenhav2006; Kuortti & Nyman, Reference Kuortti and Nyman2007). Consequently, we see a more multifaceted perspective in relation to entrepreneurial practice as narrated by Kiri, ‘I will bring everything from wherever [Māori, Western or Eastern], any tools that assist me to achieve what I am trying to achieve’. The narratives exemplify how the in-between is manifested in practice.

In general, the perception of EO dimensions, worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem of participants who demonstrate HEO are based on their evaluation and potential outcomes. Three of the key dimensions of EO from a Western perspective also seem to resonate with this group. Roland said, ‘The main unique selling proposition is innovation. Those three things go together − innovation, risk-taking and proactive’. Tipene also believed proactiveness is part of his nature because he is often ‘two steps ahead and have to wait for people to catch up’. As with the other two InEO groupings, the participant narrative also acknowledges that the entrepreneurial ecosystem has serious limitations. Kiri believed that tino rangatiratanga (the right to self-determination) should motivate more Māori to stop defaulting to social services. She explained the inherent hindrance it causes because ‘charity groups [do not] teach [Māori] to be independent’. Kiri has a dual entrepreneurial identity because she has a social business that focusses on Māori well-being and a commercial business that focusses on financial profits. Tipene observed that entrepreneurship development support needs to be more equitably distributed if greater numbers of Māori are to shape and control their economic futures because ‘Most of the functionality goes to iwi [tribal organisations] and they do not come to the lower end of the scale of Māori businesses’.

In summary, the three key Western dimensions of EO − innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness − appear to be relevant to the HEO. However, supplementing this are aspects of the Māori worldview, including tino rangatiratanga (the right to self-determination and control), and accountability to current and future generations. Although Indigenous cultural drivers are evident in the aims and aspirations of the hybrid group, they are also willing to combine Māori and Western values and practices in their businesses. Thus, they are interested in achieving both communal and individual goals and benefits.

Discussion

Prior studies have noted the importance of context and culture in understanding Indigenous entrepreneurship (Overall, Tapsell, & Woods, Reference Overall, Tapsell and Woods2010; Tapsell & Woods, 2010). In answering the research questions, the current study supports previous findings that the sociocultural context in which an Indigenous entrepreneur is embedded influences business aims and practices (e.g., Reihana, Sisley, & Modlik, Reference Reihana, Sisley and Modlik2007; Foley, Reference Foley2010; Klyver & Foley, Reference Klyver and Foley2012). Analysis of the 12 in-depth interviews revealed three distinct forms of InEO among Māori business owners: a kaupapa Māori or culturally constituted EO, a WEO and a hybrid (Māori–Western) EO. Table 4 summarises the three forms of InEO and the associated values, attitudes and behaviours derived from the narratives.

Table 4 Three forms of indigenous entrepreneurship orientation (InEO)

Note. EO=entrepreneurial orientation.

The results of this study illustrate that Māori entrepreneurs perceive EO differently to the way it is currently expressed in the literature. This finding extends previous research on EO where some contingency variables such as firm size, structure, strategy, strategy-making processes, firm resources, culture, environmental factors and top management characteristics were suggested (e.g., Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005; Pérez-Luño, Wiklund, & Cabrera, Reference Pérez-Luño, Wiklund and Cabrera2011) by including the influence of worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Table 4 shows how the three forms identified from the narratives represent the dimensions. This finding challenges the views of Lumpkin and Dess (Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996) because participants in this study who were either entering the market with new products/services (Todd, Arana and Davis) or entering established market (nine participants) demonstrated business decisions and practices based on their worldview or perception of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in which they operated. The implication of this is that Indigenous entrepreneurs with new businesses will connect the EO dimensions to the predominant EO demonstrated in their behaviours, values and business practices. For example, a more culturally oriented EO will connect their EO dimensions to their predominant cultural values as seen with some entrepreneurs in this study such as Apera, Anthony, Benjamin and Hine.

The present findings show that participant perception of worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem made up of six factors influences business decisions and practices of new business created by Indigenous entrepreneurs. The predominant views of Māori entrepreneurs indicate that the sociocultural values of Indigenous entrepreneurs will influence their business from start-up. This affirms the views of previous studies on EO that EO is initiated at entry stage (Pérez-Luño, Wiklund, & Cabrera, Reference Pérez-Luño, Wiklund and Cabrera2011). However, Māori worldview creates a basis on which the participants perceived the influence of social network and self-determination. The findings show that cultural values in social network meant using the relationship as a building block for furthering network ties for start-ups. This resonates with the concept of whanaungatanga in Māori culture, and it epitomises relationship that is characterised with reciprocity. These findings support the view that social-cultural values influence entrepreneurial activities among Indigenous entrepreneurs (Reihana, Sisley, & Modlik, Reference Reihana, Sisley and Modlik2007; Foley, Reference Foley2010; Klyver & Foley, Reference Klyver and Foley2012).

The findings show that culturally inclined Māori entrepreneurs with new businesses integrated more cultural values and customary practices into the business from start-up stage. For the more culturally oriented entrepreneur, their views on self-determination and social relations were based on cultural values which participants perceived as important. This finding is supported by the assertion that Indigenous culture and belief system are different from Western culture (Hart, Reference Hart2010; Smith, Reference Smith2012), and thus influences how participants in this research perceived these various factors in their business and enact EO.

Indigenous entrepreneurs who demonstrate WEO will have predominantly Western ideologies in business such as controlling events and having more control over business decisions although cultural or customary practices are reflected in some aspects of the business. Entrepreneurs who demonstrate this form of EO will be pragmatic, individualistic corroborating previous studies where internal locus of control was linked to performance (Poon, Ainuddin, & Junit, Reference Poon, Ainuddin and Junit2006). The findings reveal that Indigenous entrepreneurs who may appear to have more of this orientation will perceive EO from a very Western perspective and would prefer to utilise Western business models.

The notion that Indigenous communities are collective and are heavily laden with Indigenous culture has been perceived as incompatible with requirements for business success (Peredo & McLean, Reference Peredo and McLean2013). However, this research rejects that notion and argues that the two worlds can be adopted by highly Westernised Indigenous entrepreneurs. This is better articulated by the hybrid entrepreneur who consciously integrates his cultural values with Western values to create an in-between position (Bhabha, Reference Bhabha1996; Frenkel & Shenhav, Reference Frenkel and Shenhav2006) that incorporates aspects of Western and Indigenous culture. The present findings support hybrid views of the in-between and indicate that participants in this study creates a business framework, manages the cultural aspects and still adopts Western business practices. Building on the analysis and discussion, InEO can be defined as business practices, decision-making and entrepreneurial acts of Indigenous entrepreneurs that include Indigenous cultural values and Western business practices in ways that lead to a culturally constituted, Western and HEO. Thus, we explore Indigenous view of EO by exploring how Māori entrepreneurs understand and enact the five dimensions of EO in line with the propositions suggested in this study.

Conclusion

Addressing the research questions and how Māori entrepreneurs’ worldview and understanding of the ecosystem influences perception of EO creates a platform for exploring EO in an Indigenous context. Although there has been a dearth of research into the conceptualisation of EO from an Indigenous perspective, entrepreneurship is viewed as an important means to improve the socioeconomic well-being and further self-determination and to preserve heritage (Clarkson, Morrissette, & Regallet, Reference Clarkson, Morrissette and Regallet1992; De Bruin, Reference De Bruin2003; Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004). This paper argued that Māori entrepreneurs’ worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem in which they are embedded influences their perception of EO among new business owners. The Māori context provides an important platform to explore how Indigenous worldview and the contextual environment influence the perception and portrayal of EO. The results of our study affirm that argument by revealing the notion of InEO.

Theoretical implications

The results have important theoretical implications. Our findings suggest that there is no such thing as a single, distinct form of InEO. Rather, there are likely to be a variety of forms, especially among Indigenous people living in colonised countries. This also challenges assumptions about the applicability of a Western population-derived EO construct to immigrant (ethnic) entrepreneurs. In addition, our findings raise questions about the validity and generalisability of existing Western views of EO (i.e., whether it is a three- or five-component constructs) to entrepreneurs belonging to the dominant social group. Particularly as there are likely to be various types of entrepreneurs with different aims and backgrounds within a single community or country (e.g., social entrepreneurs, eco-entrepreneurs, community entrepreneurs, institutional entrepreneurs, commercial entrepreneurs, and hybrid entrepreneurs).

In addition, Peredo et al. (Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith and Honig2004) asked if the cognitive processes influenced EO, opportunity, start-up motivation and network participation in Indigenous entrepreneurship. This study indicates that sociocultural context in which the Indigenous entrepreneur is embedded creates differences in EO, start-up motivation and social network. Although this may require some modification to suit particular context, researchers can now explore mental modes of Indigenous entrepreneurs to gain a different perspective of EO. This study contributes to theory by presenting a holistic view that can serve as a platform for exploring the concept of EO in Indigenous contexts. First, by highlighting the importance of acknowledging sociocultural factors such as worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem when studying EO among Indigenous groups and showing how these different factors collectively influence how Indigenous entrepreneurs perceive EO.

Policy implications

The results also have important implications for policy. From an economic development perspective, it is vital to understand how cultural factors affect the proclivity and behaviour of existing and aspiring Indigenous entrepreneurs. It is imperative that the entrepreneurial ecosystem (including business development policies and support mechanisms, finance, business education and market access) is balanced and supports entrepreneurialism (Rante & Warokka, 2013). The participants in this study perceived that the ecosystem in New Zealand is imbalanced and hampers the efforts of Indigenous people to establish new ventures. It is worth noting that research in other countries indicates that entrepreneurship development programs often fail because they do not align with Indigenous values and beliefs (Peredo & McLean, Reference Peredo and McLean2013).

Practical implications

From a practice perspective, the findings suggest that existing and aspiring new business owners should not feel bound to aspire and/or conform to a single predetermined form of EO if they are to become successful Indigenous entrepreneurs. Rather, they need to find a balance between their own cultural values and their economic aspirations. Context is important, if entrepreneurs are focussed mainly on community development, then a culturally driven form of InEO might be more appropriate. If they wish to achieve both personal and communal ambitions, then a hybrid Indigenous–Western approach might be more applicable.

Limitations and Future Research

This paper assesses how a Māori worldview and entrepreneurial ecosystem influences perceptions of EO among new business owners. Our study makes significant contributions to theory, policy and practice to this emerging area of inquiry. In order to gain a better understanding of the various forms and dynamics of InEO, more research in other Indigenous context is required. We suggest three questions for future studies, based on our findings and a review of the Indigenous entrepreneurship and EO literatures:

-

∙ Does InEO change over time? For example, do those entrepreneurs with a culturally constituted EO move towards more Western or hybridised attitudes, values and behaviours as they become more experienced and/or fail to cope with entrepreneurial ecosystem barriers and other institutional voids?

-

∙ Do agencies set up to facilitate new business development create barriers for existing and aspiring Indigenous entrepreneurs by ignoring the importance of cultural values? How can these barriers be overcome?

-

∙ How do variables proposed in the model suggested in this paper explain causal relationships, especially the EO–performance relationship among Māori entrepreneurs?

The last question would require a quantitative approach, but effort should be made to ensure that the measurement scales recognise the subjectivity inherent in the context of the study. The findings of this study reflect the views of a relatively small sample of Māori entrepreneurs. The limitation to this study is the sample size, but it provides a platform for conducting a wider study with more samples. The findings offer important insights but cannot be generalised across other contexts. Future research on InEO can include larger and diverse sample of entrepreneurs from other industries.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is an original work that has not been submitted nor published anywhere else. All authors met criteria for authorship and have read and approved the paper.

Financial Support

The University of Otago postgraduate publishing bursary of University of Otago supported this work.

Conflicts of Interest

None.