Introduction

Initiation of sperm motility is regulated in a species-specific manner and also depends on the fertilization environment (Morisawa, Reference Morisawa1994). In external fertilization of many freshwater-dwelling lower vertebrates including anuran amphibians, a change in osmolality at spawning triggers sperm motility (Inoda & Morisawa, Reference Inoda and Morisawa1987; Morisawa, Reference Morisawa1994; Takai & Morisawa, Reference Takai and Morisawa1995). Whereas, internal fertilization is typical in urodele amphibians (Hardy & Dent, Reference Hardy and Dent1986; Greven, Reference Greven1998), and in the case of the red-bellied newt, Cynops pyrrhogaster, the sperm motility-initiating substance (SMIS) is known to act at fertilization (Ukita et al., Reference Ukita, Itoh, Watanabe and Onitake1999; Watanabe & Onitake, Reference Watanabe, Onitake and Sever2003; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). SMIS is a 34-kDa protein that is localized to granules near the surface of egg jelly. The granules are covered with a sheet-like structure that contains an acrosome reaction-inducing substance. The acrosome reaction exposes these granules to the outer surface of the jelly matrix and thus triggers sperm motility initiation. Motility initiation that is associated with the acrosome reaction is highly adapted in urodele internal fertilization, which occurs without sperm contact with freshwater (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Nakazawa, Watanabe and Onitake2006; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). A SMIS homologous protein localizes to the egg jelly of Hynobius lichenatus, an externally fertilizing urodele amphibian (Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010), suggesting that the SMIS activity may function in urodele amphibians that undergo external fertilization and may contribute to the change of fertilization mode from external to internal. To address this interesting idea, examination of the existence of the SMIS-mediated fertilization mechanism in amphibians belonging to other orders is needed.

Eggs of the externally fertilizing anuran, Discoglossus pictus, exhibit a ‘dimple’, a pit located at the centre of the animal hemisphere, which constitutes the only site where successful fertilization may occur (Campanella, Reference Campanella1975; Talevi & Campanella, Reference Talevi and Campanella1988). The egg is surrounded by three jelly layers, which are thicker in front of the dimple. In addition, there is a thick, lens-shaped jelly plug that sustains the 2.33 mm long sperm, causing the sperm to converge at the dimple.

D. pictus sperm are packed in sperm bundles. When they are spawned and come in contact with J3, the outermost jelly layer, sperm motility is initiated (Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Carotenuto, Infante, Maturi and Atripaldi1997). As Discoglossus egg jelly contains acrosome reaction-inducing activity at the outer matrix of J3 (Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Carotenuto, Infante, Maturi and Atripaldi1997), a possible similarity is pointed out in the functional machinery of the egg jelly between Discoglossus and Cynops (Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Kamimura, Takai, Watanabe and Onitake2002; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010).

To elucidate this possibility, we prepared the egg-jelly extract (JE) and confirmed that Discoglossus sperm, like those of Cynops, initiated motility in the JE. The JE-inducing motility initiation occurred in a different manner from the hypo-osmotic solution-inducing one and was suppressed by the addition of anti-SMIS monoclonal antibody (mAb). The anti-SMIS mAb recognized several bands including two major protein bands that have the molecular sizes of 34 kDa and 18 kDa in the JE as visualised by immunoblotting. However, scanning electron microscopic observation showed no granular structure near the outer surface of the egg jelly. These findings suggest that the Discoglossus egg jelly contains candidate proteins that are homologous to SMIS, which may initiate sperm motility in the Discoglossus egg jelly with a manner partially different from the SMIS protein of C. pyrrhogaster.

Materials and methods

Gametes

Sexually mature females of D. pictus were injected with 250 units of Profase HP (Serono, Rome, Italy). Eggs were obtained from the ovisac by surgical operation at approximately 18 hours post-injection. Sperm were collected from the male seminal vesicles, following injection of 200 units of Profase HP (see Talevi & Campanella, Reference Talevi and Campanella1988). Eggs and sperm were stored until use at room temperature in moist chambers without any addition of solution.

Jelly extracts

To prepare the JE, D. pictus eggs were suspended in modified Steinberg's salt solution (ST; 58.2 mM NaCl, 0.67 mM KCl, 0.83 mM MgSO4, 6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 10 mM Tris–HCl; pH 8.5) at 2 ml per egg layered in a 6 cm dish. The solution was then shaken at 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant of this suspension was harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4°C for 30 min and stored at –30°C.

Evaluation of sperm motility

Sperm bundles in the seminal fluid (1 μl) were smeared onto a glass slide, and 100 μl aliquots of JE, ST, or ST diluted 10-fold with distilled water (1/10 ST) was dropped onto the slide. Samples were then observed immediately using a compound microscope, and the experiment was conducted independently at least five times. Sperm motility was evaluated by the amount of sperm bundles that released sperm as ‘+’ most bundles have exposed sperm outside; ‘±’ less than 50% of the bundles have exposed sperm outside; and ‘–‘, few bundles have exposed sperm outside. To estimate the effects of the α34 mAb, D. pictus JE was diluted in a stepwise fashion and pretreated with anti-SMIS mAb or non-specific immunoglobulins (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10 μg/ml for 30 min at 4°C.

Nuclear staining

Sperm bundles smeared on the glass slide were treated with JE, ST, and 1/10 ST. The samples were treated with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide for 30 min, washed with ST, and then imaged under a Leica DM6000B UV-photomicroscope equipped with a digital camera.

Immunoblotting

Discoglossus pictus JE was analyzed using electrophoresis with a 15% polyacrylamide gel in Tris–glycine buffer (192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3). Western blotting onto a nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad) was performed as described by Towbin et al. (Reference Towbin, Staehelin and Gordon1979). The membrane was then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS, and incubated with 1 μg/ml α34 mAb for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with 1 μg/ml of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma-Aldrich). Specific binding of the antibodies to jelly substances was then visualised by treatment of the membrane with 0.1% 4-chloro-1-naphthol, 0.05% H2O2, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4).

Scanning electron microscopy

Preparation of egg jelly was performed as described previously (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). Briefly, D. pictus eggs were fixed in methanol at –80°C for 1 h and subsequently transferred at –20°C for 2 h. They were then treated in ethanol at 4°C overnight. After treatment with 50% ethanol and 50% t-butanol for 1 h, the eggs were immersed in 100% t-butanol at room temperature for 1 h. They were freeze-dried in the ID-2 freeze dryer (Eiko) and dissected with a fine blade. The specimens were coated with platinum and observed using a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6701F, JEOL).

Results

Effects of Discoglossus JE and low osmolality on sperm motility initiation

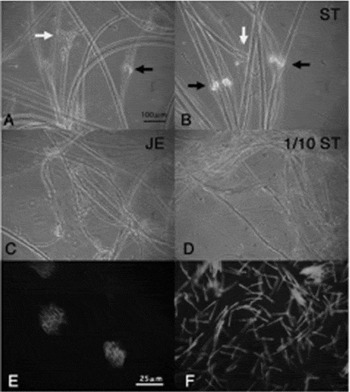

Discoglossus sperm are packed in bundles and initiate motility just when they come in touch with the surface of the egg jelly (Campanella & Gabbiani, Reference Campanella and Gabbiani1979). In the present study, dry sperm were treated with JE to characterize the motility-activating activity in Discoglossus egg jelly. Sperm were ejected from most bundles as soon as the bundles were immersed in JE (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Motility of each sperm lasted for less than 20 s. Few sperm were ejected in ST, used as a negative control, suggesting that a substance responsible for sperm motility initiation was present in the JE. Sperm were also ejected from most bundles when they were immersed in 1/10 ST, a hyposmotic solution that commonly triggers sperm motility in externally fertilizing anurans (Inoda & Morisawa, Reference Inoda and Morisawa1987; Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Carotenuto, Infante, Maturi and Atripaldi1997).

Table 1 Motility initiation of Discoglossus sperm by JE and 1/10 ST

Figure 1 Motility of Discoglossus sperm in JE and hyposmotic solution. Sperm bundles were immersed in JE or hyposmotic solution (1/10 ST). (A) Sperm bundles in seminal fluid. (B–D): Sperm bundles immersed in ST, JE, and 1/10 ST, respectively. Many ejected sperm were observed in each bundle in JE or 1/10 ST, while few ejected sperm were observed in ST. (E, F) show fluorescence images of sperm bundles stained with propidium iodide in ST and JE, respectively. The bundle included orderly lined sperm nuclei in ST (black arrows), whereas single nucleus was observed in every sperm ejected from the bundles in JE. White arrows indicate tips of the sperm bundles. Scale bar: 100 μm.

In C. pyrrhogaster, motility initiation was induced sporadically among sperm in JE, whereas it was induced simultaneously in sperm immediately after suspension in hyposmotic solution (Watanabe & Onitake, Reference Watanabe, Onitake and Sever2003). Discoglossus sperm showed a similar difference after storage of the sperm bundles for 1 day at 4°C. Each sperm bundle released sperm after varying amounts of time in JE, whereas, in the hyposmotic solution, sperm were immediately ejected from all responding sperm bundles. In addition, when the sperm were treated first with JE and then with hyposmotic solution, most bundles released sperm, whereas not as many bundles released sperm when the treatment was performed in reverse order (Table 2). These results suggest that the Discoglossus sperm may have different signalling pathways for motility initiation triggered by JE or low osmolality.

Table 2 The predominant effect of hyposmotic solution for motility initiation of Discoglossus sperm after 1-day storage

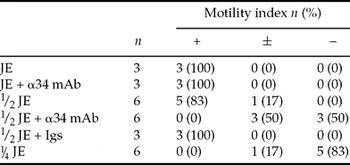

Suppression of sperm motility initiation in Discoglossus JE with α34 mAb

The α34 mAb binds specifically to SMIS or SMIS homologous protein in Cynops and Hynobius egg jelly and inhibits motility initiation in homologous sperm (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010; Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010). To examine the effects of the α34 mAb on sperm motility initiation in Discoglossus JE, JE was diluted with the ST in a stepwise fashion to prepare a diluted JE that retained a minimum level of the activity for sperm ejection in most sperm bundles (Table 3). Then, the diluted JE was pretreated with α34 mAb at 10 μg/ml for 30 min, and sperm bundles were immersed in the pretreated JE. Sperm were ejected in less than 50% of sperm bundles (Table 3). When sperm bundles were immersed in the diluted JE pretreated without immunoglobulins or with non-specific immunoglobulins as controls, the majority of the bundles released sperm. This result suggests that the motility initiation of Discoglossus sperm is suppressed by the α34 mAb.

Table 3 The inhibitory effect of the α34 mAb against JE-induced motility initiation

Igs, non-specific immunoglobulins.

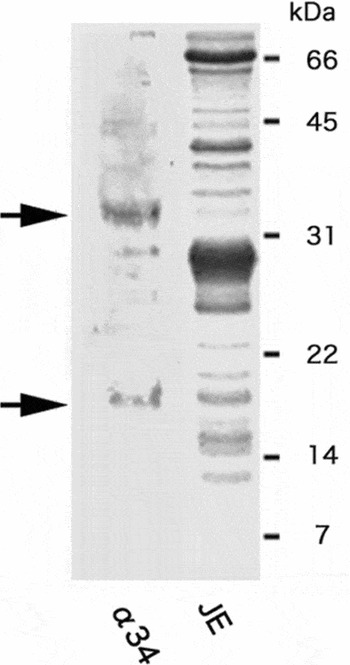

Immunoblotting of egg jelly with α34 mAb

The α34 mAb specifically recognizes the 34-kDa SMIS band in Cynops egg jelly (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010) and an 18-kDa band for SMIS homologous protein in Hynobius one (Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010). In the present study, we used this antibody for immunoblotting of Discoglossus JE. Using this antibody, we detected several bands including two major bands with the sizes of 18 kDa and 34 kDa (Fig. 2). Coomassie brilliant blue staining revealed the corresponding bands in JE, indicating that these proteins are candidates for the SMIS homologous protein that mediated sperm motility initiation in D. pictus sperm.

Figure 2 Immunoblotting of JE with α34 mAb. Solubilized JE substances were subjected to electrophoresis and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting with α34 mAb. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining of the gel after electrophoresis of JE was also performed. Several bands including approximately 18 kDa and 34 kDa (arrows) in sizes were detected using the α34 mAb.

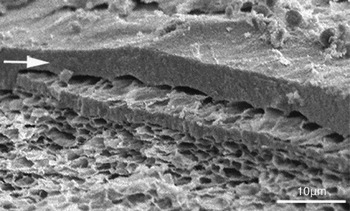

Scanning electron microscopy (EM) observation of Discoglossus egg jelly

SMIS localizes to the granular structures near the surface of Cynops egg jelly, providing an acrosome reaction-associated sperm motility initiation based on the fine structures (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). To examine whether a similar structural apparatus exists in Discoglossus egg jelly, we observed the fine morphology of the outer surface of the J3. A sheet-like structure of less than 5 μm appeared to cover the outer surface of the J3, and the structures underneath were arranged in a sponge-like fashion (Fig. 3). Although these structural features were fundamentally similar to those present in the Cynops egg jelly, no granules were identified below the sheet-like structure.

Figure 3 Scanning electron micrograph of the outer surface of J3. The outer surface of the matrix is covered with a sheet-like structure (arrow) and a network structure is observed underneath it with a sponge-like organization. Note that no granules are present under the sheet-like structure. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Discussion

Sperm motility-activating activity in Discoglossus egg jelly is essential for the homologous sperm to penetrate through the jelly matrix of J3 and the animal plug (Campanella & Gabbiani, Reference Campanella and Gabbiani1979; Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Carotenuto, Infante, Maturi and Atripaldi1997). In the present study, we demonstrated that SMIS activity might mediate the egg jelly-induced motility activation in the Discoglossus sperm (Figs. 1, 2, and Table 1). As D. pictus belongs to a primitive family in anuran amphibians (Duellman & Trueb, Reference Duellman and Trueb1994), this finding indicates that the SMIS activity may not be specific for urodele amphibians but function among anuran and urodele amphibians regardless of the modes of fertilization.

In C. pyrrhogaster, SMIS acts in association with acrosome reaction-inducing substance based on fine structures in the egg-jelly matrix. SMIS localizes to granules near the surface of egg jelly (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010), which are covered by a sheet-like structure containing acrosome reaction-inducing substance (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Fukutomi, Kubo, Ohta, Takayama-Watanabe and Onitake2009, Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). At the onset of sperm–egg interaction, quiescent sperm undergo the acrosome reaction on the sheet-like structure, digest it, and then are exposed to the SMIS protein to initiate motility. This mechanism is critical for the successful internal fertilization of C. pyrrhogaster (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Nakazawa, Watanabe and Onitake2006, Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010). In case of D. pictus, we identified a thick sheet structure on the surface of the animal plug but did not find granules (Fig. 3). Although the detailed localizations of SMIS homologous proteins and acrosome reaction-inducing substance are unknown in the egg jelly of D. pictus, the SMIS homologous proteins of D. pictus are supposed to act in a different manner. Further study about the localizations of these molecules is needed to elucidate the possible action of the SMIS activity to D. pictus sperm.

Low osmolality and the SMIS in egg jelly are known to be significant for the success of external and internal fertilization, respectively (Inoda & Morisawa, Reference Inoda and Morisawa1987; Morisawa, Reference Morisawa1994; Watanabe & Onitake, Reference Watanabe, Onitake and Sever2003). Both cues for motility initiation are effective in the sperm of C. pyrrhogaster (Ukita et al., Reference Ukita, Itoh, Watanabe and Onitake1999) and H. lichenatus (Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010). Each cue acts through a distinct intracellular signalling pathway as SMIS-initiating motility depends on a Ca2+-sensitive K+-channel (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Ito, Watanabe and Onitake2003) but low osmolality does not (Watanabe, unpublished data, Reference Watanabe, Ito, Watanabe and Onitake2003). The results of the present study indicate that Discoglossus sperm also respond to both low osmolality and the egg-jelly substances (Fig. 1 and Table 1), and this response is likely to be through different signalling pathways (Table 2). In C. pyrrhogaster, SMIS in egg jelly is a natural inducer for sperm motility initiation in the internal fertilization (Ukita et al., Reference Ukita, Itoh, Watanabe and Onitake1999; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kubo, Takeshima, Nakagawa, Ohta, Kamimura, Takayama-Watanabe, Watanabe and Onitake2010), whereas it is difficult for low osmolality-induced motility to contribute to fertilization in eggs inseminated in freshwater (Itoh et al., Reference Itoh, Kamimura, Watanabe and Onitake2002). In H. lichenatus, as males spawn sperm with contacting the cloaca to egg-jelly surface (Sasaki, Reference Sasaki1924), the SMIS homologous protein has a chance to act as a predominant cue for sperm motility initiation in their mode of external fertilization (Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010). Although the exact role of the egg jelly-induced motility initiation in fertilization of D. pictus is unclear, fertilization easily succeeds without immersing eggs in water when sperm bundles are artificially inseminated by direct contact to egg jelly (Campanella & Gabbiani, Reference Campanella and Gabbiani1979). This fertilization condition is similar to the internal fertilization of C. pyrrhogaster (Watanabe & Onitake, Reference Watanabe, Onitake and Sever2003) and enough for successful fertilization in H. lichenatus (Ohta et al., Reference Ohta, Kubo, Nakauchi and Watanabe2010). Discoglossus egg jelly may also act predominantly for sperm motility initiation at natural fertilization.

Diversified modes of amphibian fertilization are a potent model system for examining how species-specific fertilization mechanisms arose. The results of the present study raise a probability that the SMIS-mediating mechanism had been established in an ancient species of anuran and urodele amphibians, and evolutionarily modified to fit with the urodele internal fertilization. SMIS may be a useful probe to understand the modification of fertilization mechanism in conjunction with the change of fertilization environments from external to internal. SMIS may also be useful to examine the modification of the external fertilization mechanism in some terrestrially living anurans, whose sperm lose the ability to respond to low osmolality (Van der Horst et al., Reference van der Horst, Wilson, Channing, Jamieson and Ausio1995). We recently identified a gene encoding the SMIS antibody-recognized protein (Watanabe et al., unpublished data), and further comparative studies on the molecular level will contribute to our understanding of the diversification of the fertilization modes in amphibians.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Grant in Aid for Scientific Research (C) 21570236 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.