Introduction

Oogenesis is a unique process in the life cycle of metazoan organisms. During the growth phase of oogenesis, a huge amount of maternal transcripts and proteins accumulates in the cytoplasm. Activation of gene expression in oocytes is thought to be controlled by the oocyte-specific transcription system, however common mechanisms for maternal gene activation have not been elucidated. To date, efforts to determine the mechanisms of transcriptional control have been made mainly in mammals. For example, promoter analyses of h1oo, nucleoplasmin and zar1 genes by the luciferase reporter system revealed that E-box elements and Nobox-binding element (NBE) are essential for oocyte-specific expression of these genes (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Anzai, Matsuoka, Tokoro, Shin, Amano, Mitani, Kato, Hosoi, Saeki, Iritani and Matsumoto2008). Another study showed that the expression of gdf9 requires E-box elements located in the promoter sequence (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Elvin, Lin, Hadsell, Wang, DeMayo and Matzuk2006). A recent transgenic study of mice also showed the importance of E-box elements and NBEs in the promoter sequence for oocyte-specific expression of the gene oog1 (Ishida et al., Reference Ishida, Okazaki, Tsukamoto, Kimura, Aizawa, Kito, Imai and Minami2013).

The histone b4 (hb4) gene encodes a major linker histone that is specifically expressed in Xenopus oocytes (van Dongen et al., Reference van Dongen, Moorman and Destrée1983; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dworkin-Rastl and Dworkin1988; Cho and Wolffe, Reference Cho and Wolffe1994; Dworkin-Rastl et al., Reference Dworkin-Rastl, Kandolf and Smith1994) and this linker histone is replaced with a somatic cell linker histone referred to as histone H1 during early embryogenesis (Dimitrov et al., Reference Dimitrov, Almouzni, Dasso and Wolffe1993). Transition of the linker histones during oogenesis and embryogenesis occurs in both amphibian and mammalian species (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dworkin-Rastl and Dworkin1988; Cho and Wolffe, Reference Cho and Wolffe1994; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Hennebold, Macfarlane and Adashi2001). Importantly, some reports have demonstrated the physiological relevance of switching variant linker histones. It has been shown, for instance, that linker histones in oocytes and embryonic cells distinctly control chromatin structures (Saeki et al., Reference Saeki, Ohsumi, Aihara, Ito, Hirose, Ura and Kaneda2005). Steinbach et al. (Reference Steinbach, Wolffe and Rupp1997) demonstrated that transition of linker histones controls the cell competence to the mesoderm-inducing factor in Xenopus embryos. More importantly, studies on amphibian animals have demonstrated that an oocyte-specific linker histone (HB4) has a significant role in reactivation of pluripotent genes (Jullien et al., Reference Jullien, Astrand, Halley-Stott, Garrett and Gurdon2010; Reference Jullien, Miyamoto, Pasque, Allen, Bradshaw, Garrett, Halley-Stott, Kimura, Ohsumi and Gurdon2014) or in transdifferentiation in somatic cells (Maki et al., Reference Maki, Suetsugu-Maki, Sano, Nakamura, Nishimura, Tarui, Del Rio-Tsonis, Ohsumi, Agata and Tsonis2010). Therefore, it is likely that the oocyte-specific linker histone has an important function in epigenetic regulation of the chromosome structure as well as transcriptional regulation of the developmental genes.

As the hb4 gene is specifically expressed in Xenopus oocytes and this linker histone has a physiological role in oogenesis and embryogenesis, we wanted to elucidate the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of this linker histone. Results of promoter analysis of the Xenopus hb4 gene in early studies suggested the existence of positively and negatively regulatory elements in the proximal sequence, but the molecular nature of the activity has not been elucidated (Cho and Wolffe, Reference Cho and Wolffe1994). Therefore, we cloned X. tropicalis genomic DNA from the 5′ flanking region to the third exon of the hb4 gene (hb4 −6273/2915 bp) and showed that a 5′ flanking region (hb4 −3076/29 bp) has the capability to drive oocyte-specific transcription in a reporter assay. The existence of transcriptional activity in the hb4 −3076/29 sequence was also confirmed in transgenic animals carrying enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) as a reporter gene. Subsequent studies indicated that the proximal region has an activity for the transcription of hb4 in oocytes and that the Nobox plays an essential role in the regulation through the NBE located in this region. The involvement of Nobox in the expression of oocyte-specific genes both in amphibian and mammalian animals suggested a conserved role of Nobox in the initiation and maintenance of maternal genes in vertebrate species.

Materials and methods

Generation of reporter DNA constructs from X. tropicalis genomic DNA

Xenopus tropicalis genomic DNA was isolated from skeletal muscle of an adult female (a Nigerian A strain frog supplied by NBRP, Hiroshima University, Japan). Three regions of the genomic DNA from the 5′ flanking sequence to the third exon sequence (from −6273 to +2915) were amplified using Tsk Gflex DNA polymerase (TaKaRa). The DNA fragments were phosphorylated using T4 polynucleotide kinase and ligated into the IS-pBSIISK(+)-β-EGFP vector (Ogino et al., Reference Ogino, Fisher and Grainger2008) at the SmaI site. A fragment of the 5′ flanking DNA (−3076/+29) was also inserted into the pGL3-β-luc vector. The pGL3-β-luc (β-actin luc) vector was constructed from the pGL3 basic vector (Promega) by transferring the β-actin promoter sequence (SacI/HindIII fragment) from the IS-pBSIISK(+)-β-EGFP vector. Further deletion constructs were made as summarized in Fig. S1. Prediction of transcription factor-binding sites in the flanking sequence of hb4 was performed using a program supplied by JASPAR databases (Sandelin et al., Reference Sandelin, Alkema, Engström, Wasserman and Lenhard2004).

Microinjection and reporter assay

An ovary was surgically removed from an adult female of Xenopus laevis and dissected into several pieces with scissors in Ca−Mg-free 100% Maller’s modified Ringer (MMR) (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Ovary fragments were incubated in 0.2% collagenase solution (in Ca−Mg-free 100% MMR) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation to remove follicle cells. After thorough washing, stage VI oocytes were incubated in 100% MMR for 2−4 h at 18°C and were used for DNA injection. Circular plasmid DNA containing EGFP (1 ng/oocyte) or luciferase (0.1 ng/oocyte) reporter gene was microinjected into germinal vesicle of oocytes. Injected oocytes were kept at 18°C until the reporter assay was performed. Fertilized eggs of Xenopus laevis were obtained by artificial insemination. The eggs were dejellied with 2.5% thioglycolic acid (pH 8.3) and washed several times in 50% MMR. Circular plasmid DNA containing luciferase reporter gene (0.1 ng/embryo) was injected into the region between the animal pole and sperm penetration point. Injected embryos were incubated at 18°C until the reporter assay was performed.

Luciferase reporter assay

After incubation for appropriate periods (6, 9 or 24 h), three oocytes or embryos that had been injected with luciferase reporter constructs were collected in a 1.5 ml tube and were stored at −80°C. They were homogenized in 150 μl of a cell lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, 2 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1% glycerol and 0.1% Triton X-100) and were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 s. An aliquot of the supernatant (10 μl) was added to a substrate solution (100 μl) (Promega) and the light unit values of the mixture solution were measured using a luminometer (Atto). As the relative light unit values varied from different batches of oocytes and embryos, we always calculated the fold-induction ratios by comparison with luciferase activities obtained after injection of the pGL3 basic vector (promoterless). We calculated the mean and standard deviation values from three samples in a group.

Western blot analysis

For detection of GFP expression in the reporter DNA-injected oocytes, western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Kurihara, Tamaki, Mashima and Maéno2014). At 24 h after DNA injection, oocytes were added to a cell lysis buffer (0.1 M KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 mM HEPES−KOH, pH 7.4) and were homogenized with a disposable pestle (Bio-Masher, Sarstedt Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). After brief centrifugation, the protein extract (four oocyte extracts per lane) was loaded in 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and was then transferred to a membrane (Hybond™-ECL). The membrane was incubated with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Medical and Biological Laboratories Co. Ltd, Nagoya, Japan) at room temperature for 2 h and further incubated with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories Inc., UK) for 2 h. Positive signals were visualized by nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate (NBT/BCIP) solution as a substrate.

Generation of a transgenic frog

Production of transgenic Xenopus laevis was carried out using a meganuclease method according to a previous report (Ogino et al., Reference Ogino, Fisher and Grainger2008). Plasmid DNA (X. tropicalis hb4 −3076/+29 in IS-pBSIISK(+)-β-EGFP ) was cut with I-SceI and was injected into fertilized embryos in the region between the animal pole and sperm penetration point within 1 h after fertilization. Injected eggs were kept at 18°C until the next day. Screening was carried out according to the presence or absence of GFP fluorescence at the tailbud stage and a female that carried the transgene was mated with a wild-type male to obtain an F1 generation.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) from organs isolated from transgenic F1 frogs or wild-type frogs. Complementary DNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Superscript VIRO, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primers used for amplification of hb4, Nobox, odc and EGFP genes were as follows: hb4, 5´-TCTTCCTTGGCCTTTTTAGC-3´ (forward) and 5´-GCTAAAAAGGCCAAGGAAGA-3´ (reverse); odc, 5´-GGTTCAGAGGATGTGAAACT-3´ (forward) and 5´-CATTGGCAGCATCTTCTTCA-3´ (reverse); Nobox, 5´-CGACTTCCACTGCATAGCCT-3´ (forward) and 5´-GTCCTGATCTTCAGAGGCCT-3´ (reverse); EGFP, 5´-GGCATCGACTTCAAGGAGGA-3´ (forward) and 5´-CTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC-3´ (reverse).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP assay was performed as reported previously (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Tomita, Shi and Wong2006). Oocytes were injected with the RNA coding for myc-tagged Nobox and hb4 −288/+28 luc DNA. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 1% w/v formaldehyde and sonicated. The obtained lysate was immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody. Amplification of the DNA after precipitation was performed with the following primers: 5´-GCCTTTAATTGCTTGTAATTTTTC-3´ (−288/−265) and 5´-CCTTCTTAGGCCCCATCTCAGAATC-3´ (+5/29).

Results

The hb4 −3076/+29 sequence drives expression of a reporter gene in oocytes

hb4 is a linker histone gene specifically expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dworkin-Rastl and Dworkin1988). In this study, in order to identify the transcriptional control elements, flanking and intron sequences of X. tropicalis hb4 genome DNA were amplified from the genomic DNA that had been extracted and purified from adult muscle tissue. Three regions of DNA (−6273/−3315, −3076/+29 and +67/+2915) from the hb4 5´-flanking sequence to the third exon were amplified by a PCR strategy and were inserted into vectors derived from a pBS containing the chicken β-actin minimum promoter sequence and EGFP reporter gene (IS-pBSIISK(+)-β-EGFP) (Ogino et al., Reference Ogino, Fisher and Grainger2008). Plasmid DNAs containing the three regions of the hb4 genome as well as control DNA containing the β-actin minimum promoter sequence were injected into stage VI oocytes and the oocytes were incubated for 24 h. Expression of GFP was not detected or was very weak in oocytes when the control DNA (β-actin promoter), −6273/−3315/EGFP DNA, or +67/+2915/EGFP DNA was injected. By contrast, a certain level of GFP expression was confirmed by injection of −3076/+29/EGFP DNA (Fig. 1A−1H). Western blot analysis revealed that a 26-kDa band was specifically detected by an anti-GFP antibody in the extract of oocytes that had been injected with −3076/+29/EGFP DNA (Fig. 1I). Therefore, we concluded that the proximal sequence from −3076 to +29 of the hb4 gene contained a control element for transcriptional activation of hb4 in oocytes.

Figure 1 Identification of positive regulatory elements in the X. tropicalis histone b4 gene. (A−H) Three regions of the flanking and intron sequences of X. tropicalis hb4 gene were examined for transcriptional activity. Each DNA that had been amplified from the genomic DNA was inserted upstream of the EGFP reporter gene and the resultant plasmid DNA (1 ng) was injected into the germinal vesicle in oocytes. GFP signal was observed 24 h after injection. Images in bright (A, C, E, G) and dark (B, D, F, H) fields show that GFP expression was positive in oocytes injected with the reporter construct containing the −3076/+29 promoter sequence. (I) Western blot analysis showed the expression of GFP in oocytes that had been injected with the reporter construct containing the −3076/+29 promoter sequence from the hb4 gene. Soluble protein from four oocytes was loaded in each lane.

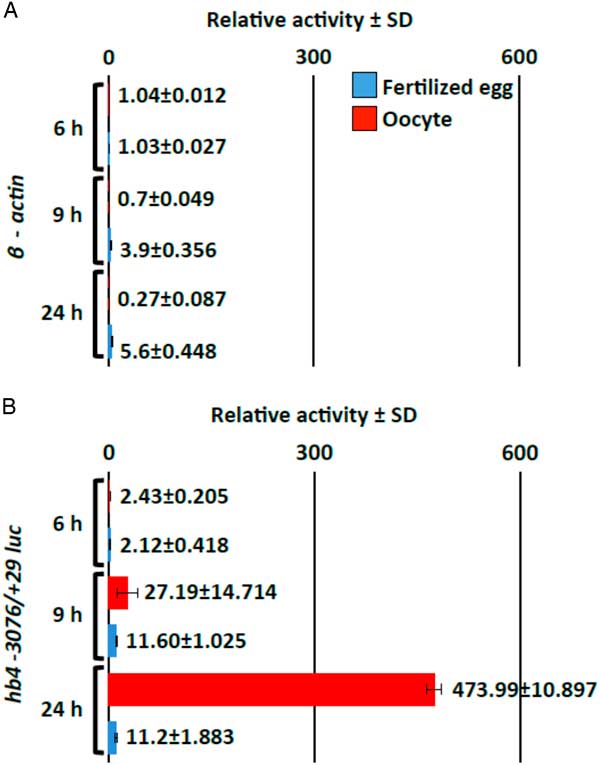

To test whether hb4 −3076/+29 DNA drives cell type-specific transcription in oocytes, we compared the transcriptional activities in oocytes and developing embryonic cells (Fig. 2). For this purpose, the DNA fragment of −3076/+29 was inserted into a plasmid containing the β-actin minimum promoter sequence and the luciferase gene (hb4 −3076/+29 β-actin luc). The construct or a control plasmid containing the β-actin minimum promoter sequence and the luciferase gene (β-actin luc) was microinjected into oocytes or into fertilized eggs. The cells were incubated for 6, 9 or 24 h and then the cells were harvested to measure luciferase activity in the extract. Relative folds to the values obtained from the injection of control plasmid DNA (luc gene without the promoter sequence) were plotted and were compared between the oocytes and developing embryos (Fig. 2A). Relative folds of luciferase activity in the fertilized eggs injected with β-actin luc DNA were 3.9 at 9 h and 5.6 at 24 h of incubation. Conversely, luciferase activities in the oocytes injected with β-actin luc DNA did not increase up to 24 h of incubation, suggesting that the minimum promoter sequence drives the transcriptional activity to a certain degree only in the developing embryo. Relative folds of luciferase activity in the fertilized eggs injected with hb4 −3076/+29 β-actin luc DNA were 11.6 at 9 h and 11.2 at 24 h of incubation. We speculated that the minimum promoter sequence drove the transcriptional activity to a certain degree in the developing embryo and therefore the hb4 −3076/+29 sequence did not drive the transcriptional activity in embryonic cells. By contrast, relative activities increased dramatically when plasmid DNA containing hb4 −3076/+29 luc DNA was injected into the oocytes (Fig. 2B). The activities were 27.2-fold at 9 h and 474-fold at 24 h of incubation relative to those of the promoterless plasmids. We concluded therefore that the hb4 −3076/+29 sequence included a positive regulatory element specifically activated in oocytes.

Figure 2 Oocyte-specific activity of the hb4 −3076/+29 promoter sequence. A luciferase reporter construct containing the β-actin minimum promoter sequence alone (negative control) (A) or a construct containing the hb4 −3076/+29 promoter sequence (B) in addition to the β-actin minimum promoter sequence was injected into oocytes (red bars) and fertilized eggs (blue bars) (0.1 ng/oocyte or egg). The oocytes and fertilized eggs were harvested at 6, 9 or 24 h after injection and luciferase activity in the cell extract was measured. The transcriptional activities were calculated by relative values of luciferase activity obtained by injection of the basic luciferase construct.

A transgenic frog carrying the hb4 −3076/+29 sequence shows germ cell-specific activation of a reporter gene

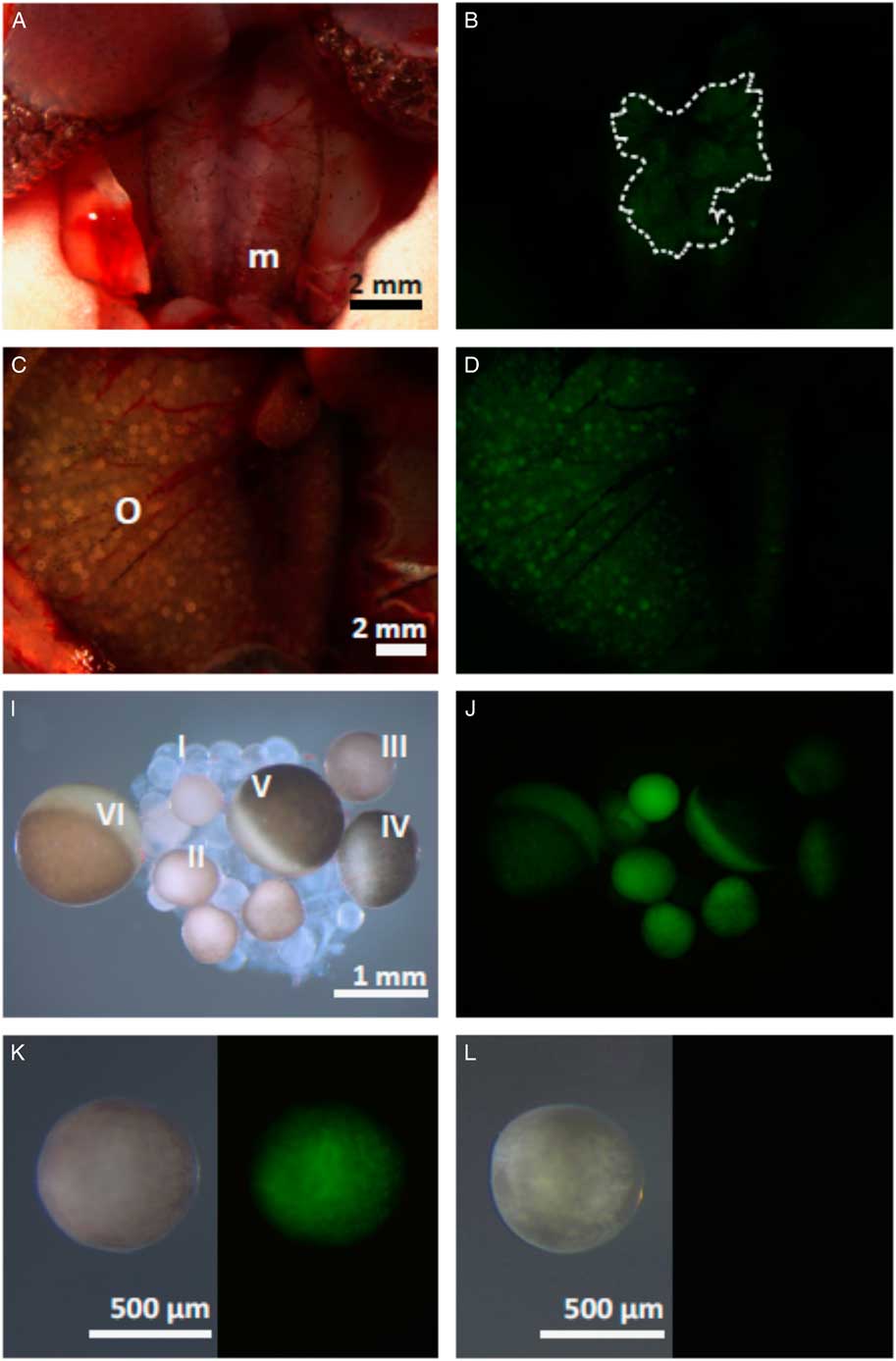

To determine whether the promoter sequence of hb4 −3076/+29 contains the elements necessary and sufficient for transcription activity in an oocyte, we attempted to produce a transgenic frog with the EGFP reporter sequence under control of the hb4 promoter sequence and the actin minimum promoter sequence. F1 generation animals derived from transgene-carrying Xenopus laevis were analyzed (Fig. 3). Anatomical observation in metamorphosed females (3 months old) showed that weakly positive expression of GFP was visible in the ovary (Fig. 3A,B). Furthermore, the intensity of GFP expression was high enough to examine the expression in each oocyte in the ovary of a matured female (6 months old) (Fig. 3C,D). In the dissected ovary, stage I oocytes were GFP negative, whereas stage II to stage VI oocytes were strongly positive (Fig. 3E,F). The defolliculated oocyte (stage III) of the transgenic female was GFP-positive (Fig. 3G), but that of the wild-type female was negative (Fig. 3H). No GFP expression was detected in a male frog at 3 months of age (Fig. 3I,J), but the expression became positive in the testis of a matured male frog (6 months old) (Fig. 3K,L). RT-PCR analysis revealed that EGFP was clearly expressed in the adult ovary and testis but not in other organs, whereas hb4 was expressed only in the ovary (Fig. 3M). Immunohistochemical observations showed that GFP expression was localized in the region in which matured spermatids existed (Fig. S2), suggesting that the promoter sequence of hb4 −3076/+29 drives the transcription activity in a germ cell-specific manner.

Figure 3 Organ-specific expression of GFP in transgenic frogs carrying the hb4 −3076/+29 sequence. (A−L) Anatomical views of 3-month-old (A, B) and 6-month-old (C, D) female frogs are shown. Expression of GFP in the ovaries was confirmed in both the 3-month-old and 6-month-old female frogs (B, D). Oocytes were isolated from the ovaries of the 6-month-old female frog (E, F) and it was shown that stage II oocytes, but not stage I oocytes, expressed GFP. The defolliculated oocyte (stage III) of the transgenic animal was also positive for GFP expression (G), but that of the wild-type animal was negative (H). Anatomical views of 3-month-old (I, J) or 6-month-old (K, L) male frogs showed that the expression of GFP is positive in the testis at 6 months of age (L). (M) RT-PCR analysis was performed to examine the expression of EGFP and hb4 in various organs. hb4 was expressed only in the ovary, whereas EGFP was expressed in both the ovary and testis. m, mesonephros; o, ovary; t, testis. Dotted line in (B) shows the ovary weakly expressing GFP.

The most proximal region of the promoter sequence drives activation of a reporter gene

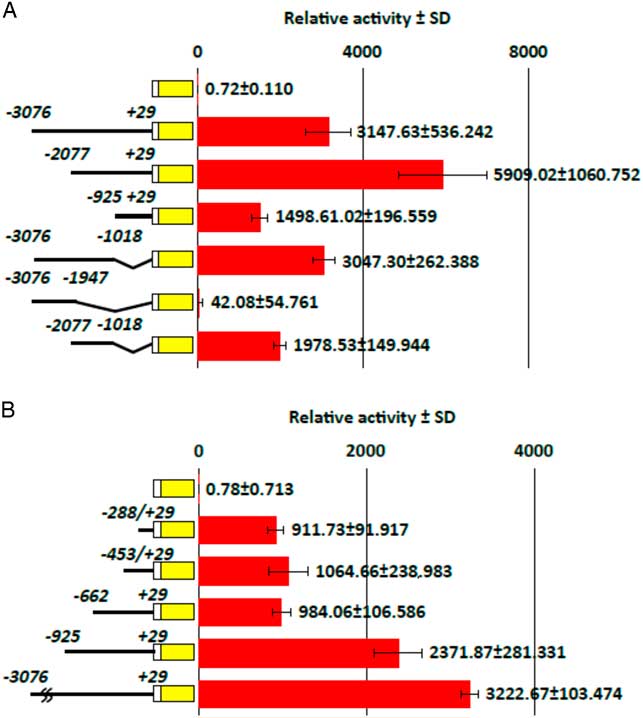

In order to identify the elements responsible for expression in the oocyte, reporter assays using a series of deletion constructs of the hb4 −3076/+29 sequence were performed (Fig. 4A). Each deletion mutant was inserted into a plasmid containing the β-actin minimum promoter sequence and the luciferase gene and the plasmid was injected into oocytes. Luciferase activity in the cell extract was measured 24 h later. Relative folds to the values obtained from injection of control plasmid DNA (luc gene without the promoter sequence) showed that deletion constructs from the 5′ sequence of the promoter region (−3076/+29, −2077/+29, −925/+29) induced a certain level of transcription activity in oocytes, indicating that the proximal sequence in the −925/+29 region included an element for oocyte expression. Among the deletion constructs from the 3′ sequence of the promoter region (−3076/+29, −3076/−1018, −3076/−1947), the −3076/−1947 region had no activity for transcription, while the two other constructs showed a high level of transcription activity. In addition, the −2077/−1018 region showed a high level of transcription activity. Based on the results, we concluded that more than two elements for transcription exist in the sequence of −2077/+29 and that the proximal sequence less than −925 is sufficient for activation of transcription in oocytes.

Figure 4 Identification of transcriptional activities in various deletion mutants of the hb4 promoter sequence. Luciferase reporter constructs containing various regions of the hb4 −3076/+29 promoter sequence were injected into oocytes (0.1 ng/oocyte). The oocytes were harvested 24 h after injection and luciferase activity in the cell extract was measured. The transcriptional activities were calculated by relative values of luciferase activity obtained by injection of the basic luciferase construct. (A) Deletion experiments from the 5′ and 3′ sequences of the promoter region showed that a proximal (−925/+29) and a distal (−2077/−1018) sequences drove an activity for oocyte expression. (B) A deletion experiment from the 5′ sequence in the proximal region (−925/+29) showed that a proximal (−288/+29) sequence drove an activity for oocyte expression.

Subsequent experiments were carried out to identify a core sequence for the oocyte-specific expression. We made three additional deletion constructs (−662/+29, −453/+29, −288/+29) and examined their transcription activity in oocytes after injection of the plasmid DNA (Fig. 4B). Reporter assays indicated that all of the three deletion constructs induced a high level of transcription activity in comparison with the −925/+29 sequence. Therefore, we concluded that the −288/+29 sequence contains an element for oocyte-specific transcription.

Nobox and NBE in the promoter sequence are involved in the hb4 transcription in oocytes

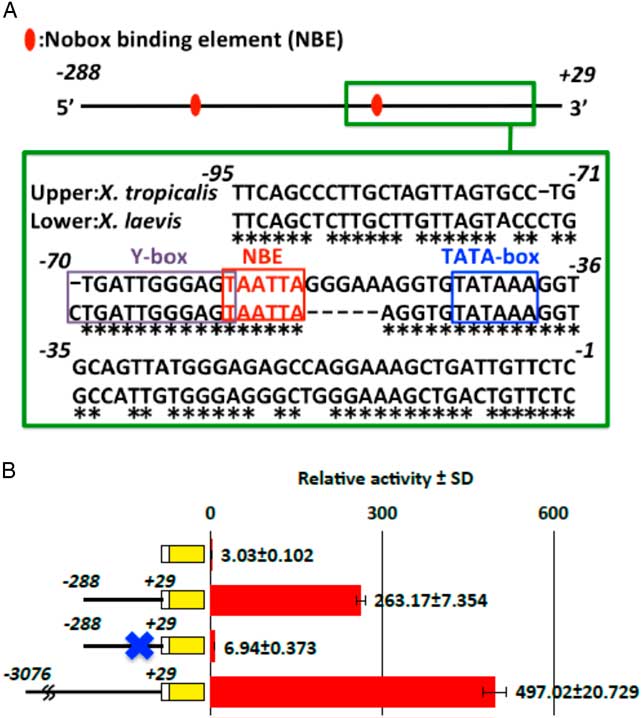

Previous studies have shown that the expression of oocyte-specific genes is regulated by an E-box and NBEs in mammalian species (Huntriss et al., Reference Huntriss, Gosden, Hinkins, Oliver, Miller, Rutherford and Picton2002; Suzumori et al., Reference Suzumori, Yan, Matzuk and Rajkovic2002; Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Anzai, Matsuoka, Tokoro, Shin, Amano, Mitani, Kato, Hosoi, Saeki, Iritani and Matsumoto2008; Ishida et al., Reference Ishida, Okazaki, Tsukamoto, Kimura, Aizawa, Kito, Imai and Minami2013). Therefore, we searched for transcription factor-binding motifs including these two factors in the proximal sequence of the hb4 gene (−288/+29). Two NBEs were found in the −288/+29 sequence (Fig. 5A). Importantly, the proximal sequences including the NBE sites were highly conserved between X. tropicalis and X. laevis genomes. To examine the role of the proximal NBE sequence, six nucleotides (TAATTA) were deleted by a PCR-mediated plasmid DNA deletion method (Hansson et al., Reference Hansson, Rzeznicka, Rosenbäck, Hansson and Sirijovski2008) and the resultant reporter construct was used for a luciferase assay. The luciferase activity in the NBE-deleted construct decreased to 2.6% of that in the control construct (−288/+29) (Fig. 5B). Therefore, we concluded that the NBE sequence (−55/−60 in the X. tropicalis genome) is an essential element for transcriptional activation in oocytes.

Figure 5 Involvement of a Nobox-binding element in oocyte-specific transcriptional activity. (A) The transcription factor-binding site in the promoter sequence (hb4 −925/+29) of the X. tropicalis hb4 gene was searched for using the JASPAR database (Sandelin et al., Reference Sandelin, Alkema, Engström, Wasserman and Lenhard2004). Three NBEs were found in the whole sequence and an NBE site was found in the most proximal region in the promoter sequences of both X. tropicalis and X. laevis (chr4L) genomes. The TATA-box and Y-box (Tafuri and Wolffe, Reference Tafuri and Wolffe1990) are also shown. (B) A luciferase reporter assay showed that the proximal NBE site is essential for transcriptional activity. Construct DNAs were injected into oocytes (0.1 ng/oocyte). The oocytes were harvested at 24 h after injection and luciferase activity in the cell extract was measured.

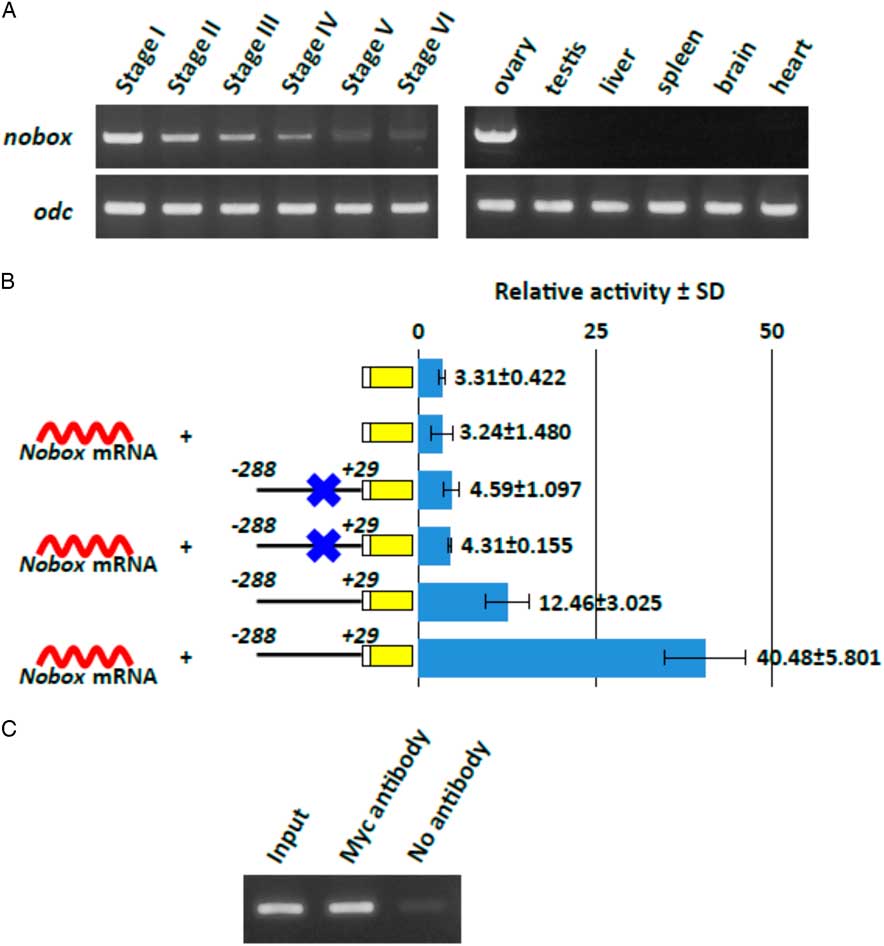

In order to determine whether Nobox has a crucial role in activation of the hb4 gene in an oocyte, we performed RT-PCR analysis to detect the Nobox transcript in oocytes of various stages and in various organs of the adult frog (Fig. 6A). We found that the Nobox transcript was highly expressed in stage I oocytes and that the amount of the message gradually decreased during the growth of oocytes. In adult organs, Nobox was expressed in the ovary but not in any other organs examined. We then examined the activity of recombinant Nobox for transcription of a reporter construct (hb4 −288/+29) (Fig. 6B). The reporter DNA and X. laevis Nobox mRNA were co-injected into a 2-cell stage embryo and the activities were measured after 24 h of incubation. The transcriptional activity in the reporter DNA (hb4 −288/+29) with Nobox mRNA was 3.2-times higher than the activity in the reporter DNA without Nobox mRNA. In addition, the NBE-deleted construct did not respond to the overexpression of Nobox mRNA. Finally, we performed ChIP analysis to show direct binding of the Nobox protein to the NBE in the −288/+29 sequence. The mRNA coding for a recombinant myc-tagged Nobox protein and the −288/+29 DNA were injected into the oocytes and the cell extract was immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody. PCR of the precipitated DNA indicated that the DNA including the NBE site was selectively amplified (Fig. 6C). The result confirmed that Nobox expressed in oocytes binds to the NBE sequence and plays an essential role in transcriptional activation of the hb4 gene in oocytes.

Figure 6 Expression and function of Nobox in Xenopus oocyte. (A) RT-PCR analysis was performed to examine the expression of X. laevis Nobox in oocytes at various stages and in various adult organs. The analysis showed that Nobox is only expressed in the ovary. (B) Overexpression of Nobox mRNA enhanced luciferase reporter expression through the NBE sequence in fertilized eggs. Nobox mRNA (0.5 ng) and hb4 −288/+28 reporter construct (0.1 ng) with or without the NBE sequence were co-injected into 2-cell embryos. The embryos were harvested at 24 h after injection and luciferase activity in the cell extract was measured. (C) The oocytes were injected with mRNA coding for myc-tagged Nobox and hb4 −288/+29 luc DNA. After crosslinking of the DNAs and proteins, immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-myc antibody. The PCR products from a sample before the precipitation process were used as a positive control (input) and a sample precipitated without the anti-myc antibody (no antibody) is also shown.

Discussion

In the present study, we elucidated the transcriptional activation elements in the proximal region of the 5′ flanking sequence of the Xenopus tropicalis histone b4 gene. The proximal promoter DNA of Xenopus laevis was cloned to detect the elements for transcription control in germ cells and somatic cells (Cho and Wolffe, Reference Cho and Wolffe1994) and a negative element in the promoter region for expression of the Xenopus laevis hb4 gene in somatic cells (A6 cell line) was found in that study. The mechanisms underlying specific activation of the hb4 gene in oocytes have not been elucidated. Here, we found an activating element in the region of the −288/+29 proximal sequence and we found that Nobox is an essential transcription factor for the expression of hb4 in oocytes. The involvement of NBE in transcriptional activation in oocytes has been suggested for several genes including npm2 and oog1 in mice (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Anzai, Matsuoka, Tokoro, Shin, Amano, Mitani, Kato, Hosoi, Saeki, Iritani and Matsumoto2008; Ishida et al., Reference Ishida, Okazaki, Tsukamoto, Kimura, Aizawa, Kito, Imai and Minami2013). Nobox is an oocyte-specific homeobox transcription factor that is essential for folliculogenesis and ovary development (Rajkovic et al., Reference Rajkovic, Pangas, Ballow, Suzumori and Matzuk2004; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Qin, Berger, Ballow, Bulyk and Rajkovic2007), therefore the present study suggested that the Nobox control system in oocyte development is conserved among tetrapod animals. In agreement with this hypothesis, it was found in the present study that the Nobox transcript was specifically expressed in the ovaries of adult frogs (Fig. 6) and that the oocyte-specific expression of Nobox gradually diminished in embryos during development (data not shown). Exceptionally, we found in RT-PCR analysis that stage I oocytes showed a high level of Nobox expression, but their GFP expression in the transgenic animals was negative. As discussed below, transcriptional regulation of the EGFP gene in the transgenic animals does not completely reflect endogenous control of the hb4 gene and by the RT-PCR analysis hb4 message was found to be abundantly expressed in stage I oocytes (data not shown).

A comparison of the promoter sequences in X. tropicalis and X. laevis indicated that approximately 100 nucleotides of the proximal sequence from the transcription starting site were highly conserved. A germline-specific transcription factor, FRGY2, that binds to the Y-box sequence located at the immediate upstream site of the TATA-box was identified in the previous studies (Tafuri and Wolffe, Reference Tafuri and Wolffe1990; Cho and Wolffe, Reference Cho and Wolffe1994). As high transcription activity was shown in the proximal flanking DNA sequence (300 nucleotides), it was suggested that the Y-box is involved in hb4 gene expression in oocytes. In the present study, in addition to the Y-box, the NBE located between the Y-box and TATA-box was shown to have an essential role in hb4 gene expression (Fig. 5A). Deletion of the NBE sequence resulted in almost complete loss of the reporter activity in the hb4 −288/+29-β-luc construct. The close locations of the Y-box and NBE in the promoter sequence raises the possibility that interaction of the Y-box binding protein and Nobox protein may occur. Further studies are needed to determine whether these two DNA binding proteins interact with each other and participate in transcriptional activation.

In a transgenic frog carrying the EGFP gene under the control of the hb4 promoter sequence (−3076/+29), GFP expression was induced in both the ovaries and testis. This was an unexpected result as the b4 transcript is expressed only in oocytes. The expression of GFP in the testis was not visible in tadpoles and froglets (3 months old), although GFP was detected in ovaries at these stages. This finding means that activation of transcription in the testis begins at a relatively late stage when spermatogenesis had progressed. Histological analysis showed that the GFP protein was localized in seminiferous tubules, in which matured sperms and spermatids exist. Therefore, we suggest that the hb4 promoter sequence is controlled specifically in male and female germ cells. Similar results were obtained from oog1 promoter analysis in a recent transgenic study in mice (Ishida et al., Reference Ishida, Okazaki, Tsukamoto, Kimura, Aizawa, Kito, Imai and Minami2013). The promoter sequence of oog1 containing a 3.9-kb flanking region induced strong expression of GFP in both the ovary and testis, whereas a 2.7-kb flanking region induced strong expression in the ovary and weak expression in the testis. The methylation statuses of the proximal sequences in these two transgenes are different, suggesting that epigenetic regulation is involved in differential expression of the oog1 gene in the testis and ovary. Although the mechanisms underlying the differential regulation in male and female germ cells are not known at present, it is possible that expression of hb4 is regulated by elements other than the 3-kb flanking sequence that may function as a male-specific repressor. Alternatively, it is possible that the transgene was inserted in a region under the control of the testis-specific enhancer and therefore EGFP was expressed in the transgenic animals.

The present study revealed that oocyte-specific expression of the hb4 gene in Xenopus is regulated by a conserved transcription factor, Nobox, that binds to the NBE located at the proximal flanking sequence of the promoter. Although removal of the NBE sequence from the reporter construct resulted in complete loss of the reporter activity, overexpression of Nobox in embryonic cells enhanced the reporter activity at a low level (3.2-fold; Fig. 6). The limited effect of Nobox overexpression might be due to the cell types used for the experiment. Interestingly, the level of reporter activity in fertilized eggs was 40-times lower than that in oocytes (Fig. 2). It is possible that a repressive factor exists in the fertilized egg and that it interferes with Nobox activity. Alternatively, a cofactor(s) might be necessary for Nobox to elicit its activity transcription of the hb4 gene. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms is needed for understanding Nobox-dependent activation through the proximal promoter region. In addition, regions other than the proximal sequence may be involved in the maintenance of transcriptional activity in oocytes. We found that the −2077/−1018 region showed a high level of transcriptional activity in oocytes. Another series of deletion study using the reporter construct is currently being carried out.

Financial support

This work was partly supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (16K07367).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Procedures for the anaesthesia and surgical operation of frogs were approved by the Ethics Committee of Niigata University, Japan.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0967199419000017