Introduction

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a promising technique to produce mammalian transgenic clones. Embryos and fetuses have been successfully generated using SCNT in a range of species (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Misica, Day and Tervit1997, Reference Wells, Misica and Tervit1999; Wakayama et al., Reference Wakayama, Perry, Zuccotti, Johnson and Yanagimachi1998; Wilmut et al., Reference Wilmut, Schnieke, McWhir, Kind, Campbell, Nussbaum and Sunstein1997; Polejaeva et al., Reference Polejaeva, Chen, Vaught, Page, Mullins, Ball, Dai, Boone, Walker and Ayares2000; Chesné et al., Reference Chesné, Adenot, Viglietta, Baratte, Boulanger and Renard2002). In livestock, however, SCNT cloning is inefficiently developed to full-term (Cibelli et al., Reference Cibelli, Stice, Golueke, Kane, Jerry, Blackwell, de Leon and Robl1998; Kato et al., Reference Kato, Tani, Sotomaru, Kurokawa, Kato, Doguchi, Yasue and Tsunoda1998; De Sousa et al., Reference De Sousa, King, Harkness, Young, Walker and Wilmut2001; Watanabe & Nagai, Reference Watanabe and Nagai2009, Reference Watanabe and Nagai2011; Meng et al., Reference Meng, Jia, Sun, Wang, Wan, Zhang, Zhong and Wang2014; Jia et al., Reference Jia, Zhou, Zhang, Wang, Fan, Wan, Zhang, Wang and Wang2016). Most cloned embryos die during post-implantation development, and those that survive to term are frequently defective (Wrenzycki et al., Reference Wrenzycki, Wells, Herrmann, Miller, Oliver, Tervit and Niemann2001; Cibelli et al., Reference Cibelli, Campbell, Seidel, West and Lanza2002). Abnormal placentation has been described in several cloned species (Suemizu et al., Reference Suemizu, Aiba, Yoshikawa, Sharov, Shimozawa, Tamaoki and Ko2003; Farin et al., Reference Farin, Piedrahita and Farin2006). Moreover, recent molecular evidence supports the hypothesis that the placental lineage is particularly vulnerable to problems arising from somatic nucleus reprogramming after nuclear transfer (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Smith, Tian, Lewin, Renard and Wakayama2007).

Successful nuclear transfer depends on nuclear reprogramming of an adult somatic nucleus to an embryonic state. Normal development involves many epigenetic modifications. DNA methylation, a well studied epigenetic modification, has been regarded as a key contributor to mammalian development, gene regulation and genome stability (Klose & Bird, Reference Klose and Bird2006). Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 1 (MBD1) is highly related to DNA methylation. Its MBD domain recognizes and binds to methylated CpGs. This binding allows it to trigger methylation of H3K9 and results in transcriptional repression. The CXXC3 domain of MBD1 makes it a unique member of the MBD family due to its affinity to non-methylated DNA. MBD1 acts as an epigenetic regulator via different mechanisms, such as the formation of the MCAF1/MBD1/SETDB1 complex or the MBD1-HDAC3 complex (Li et al., Reference Li, Chen and Chan2015). Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), the first MBD to be characterized, localizes to densely methylated DNA. This protein can bind to as little as one methylated CpG dinucleotide and represses transcription through a transcriptional repression domain (TRD). MeCP2 can associate with histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), providing a link between DNA methylation and histone deacetylation and methylation, which act as a transcriptional repressor by binding to target gene promoters and silencing their transcription (Nan et al., Reference Nan, Tate, Li and Bird1996; Fuks et al., Reference Fuks, Hurd, Wolf, Nan, Bird and Kouzarides2003).

As methylation levels always changes along with embryogenesis, MBDs with its interacting partners, including proteins and non-coding RNAs, participate in normal or pathological processes and function in different regulatory systems. Because of the important role of MBDs in epigenetic regulation, we hypothesized that MBD1 and MeCP2 may have a crucial function in developmental events, including embryo cleavage and placenta development. This study aimed to characterize the coordinated mRNA expression and protein localizations of MBD1 and MeCP2 in embryos and placentas from transgenic cloned goats in an effort to determine how MBD1 and MeCP2 functions. These findings could provide clues to understanding the low efficiency of transgenic cloning.

Materials and Methods

This study was performed in strict accordance with recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Nanjing Agricultural University. All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and every effort was made to minimize suffering.

Embryos

Embryos in our study consisted of two groups: N (normal) group and T (transgenic clone) group. The N group was in vivo embryos produced by the internal fertilization. The T group was in vitro embryos produced by SCNT.

In vivo embryo production

To obtain sufficient in vivo embryos, oestrous synchronization was performed using an intravaginal device (EAZI-BREED™ CIDR®, Animal Health Supplies, Ascot Vale, VIC, Australia) for 12 days each group (n = 5). Superovulation treatments were initiated at 48 h (Day 10) before the end of progesterone exposure. All Saanen dairy goats were superovulated with a total dose of 180 IU follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH; Pituitary Follitropin For Injection, Ningbo Sansheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, China), which was divided into six decreasing doses i.m. given twice daily. Two injections of PGF2α analogue and 50 μg of d-cloprostenol (Cloprostenol Sodium for Injection, Ningbo Sansheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, China) were given concurrent with fifth and sixth FSH treatments. After CIDR removal, the does were checked for oestrus with an aproned adult male twice daily and were randomly mated to one of three fertile bucks every 12 h as long as they displayed standing oestrus. At 24–36 h after the last mating, the embryos were collected.

In vitro embryo production

The manufacturing process of in vitro embryos using SCNT is shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, goat fibroblast cells from ears of 3-month-old goats were used to produce donor somatic cells harboring the hLF gene for SCNT. The culture and passage of donor cells, oocyte collection and enucleation, nuclear transferring, oocyte activation, embryo culture, and embryo transfer were carried out in order (Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhang, Zhou, Jia, Li, Song, Wang, Wang, Zhang, You and Wang2012).

Figure 1 Manufacturing process of in vitro embryo using somatic cell nuclear transfer. (A) In vitro maturation oocytes. (B) Mature oocytes without cumulus oophorus. (C, D) enucleation; (E, F) nuclear transfer.

Embryo collection

Reconstructed and internal fertilization embryos were washed three times, transferred into 150-µl droplets of M16 medium (Sigma, USA) under mineral oil, and cultured for 6 days at 38.5°C with 5% CO2 in air. Cleavage and development to the blastocyst stage were observed from day 2 to day 7. One-cell embryos, 2–4-cell embryos, 8–16-cell embryos, morulas, and blastocysts were also collected (Fig. 2). Twenty embryos from each stage were randomly selected and stored in Sample Protector for RNA (TaKaRa, China) until RNA isolation.

Figure 2 Transgenic cloned embryos at different developmental stages. (A) 2-cell stage; (B) 4-cell stage; (C) 8-cell stage; (D) 16-cell stage; (E) 32-cell stage; (F) blastocyst stage.

Placentas

Placentas in our study consisted of three groups: normal goats (NG), live transgenic cloned goats (LTCG) and deceased transgenic cloned goats (DTCG). NG included four newborn normal goats from conventional reproduction, which were used as the control. LTCG included four live cloned goats that were lived healthy up to now. DTCG included four dead cloned goats that died within 3-day after birth. All placental samples were weighed out, the size and number of placenta cotyledon were measured, and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use. Other portions of the placentas were fixed for 24 h in 4% formaldehyde, and stored in 75% alcohol. Fixed tissues were analysed for structural organization.

Gene expression analyses

Total RNA was isolated from embryos and placentas using RNeasy Micro kits (Qiagen, Germany), and placental tissue RNA was extracted using RNAprep Pure kits (Tiangen, China) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied BioSystems, USA) and detected using SYBR Green Master Mix in a reaction volume of 20 µl. The primers used in real-time PCR are shown in Table 1. Comparative quantification of MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Pfaffl, Reference Pfaffl2001).

Table 1 Primers for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Abbreviations: bp, base pair; F, forward; R, reverse.

Protein location analyses

After fixation, placental tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 6-μm sections were cut and mounted on slides. Sections were processed for immunohistochemical staining as described previously (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Key and Kalra1991). A primary rabbit anti-MBD1 antibody (1:500, Abcam, USA) and secondary antibody (1:1000, Beyotime, China) were used in the immunohistochemical analyses. Specific protein immunoreactivity was visualized by incubation with DAB (3,3´-diaminobenzidine, Beyotime, China). The primary antibody was replaced with normal rabbit serum as a negative control.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (IBM, USA). Experimental data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences in the mean were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant differences were defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Relative expression of MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA in transgenic cloned embryos

During the early embryonic developmental stage, MBD1 and MeCP2 expression showed significant differences between transgenic cloned embryos and fertilized eggs (Fig. 3). Specifically, at the 2–4-cell embryo stages, compared with fertilization embryos, MBD1 expression was significantly higher in transgenic cloned embryos (P < 0.05, Fig. 3 A), but MeCP2 was significantly lower in transgenic cloned embryos (P < 0.05, Fig. 3 B). At 8–16-cell embryo stages, the MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA levels in transgenic cloned embryos were higher compared with fertilization embryos (P < 0.05, Fig. 3). At the morula and blastocyst stages, MBD1 expression was extremely lower in transgenic cloned embryos than fertilization embryos (P < 0.01, Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3 MBD1 and MeCP2 transcript levels in zygotes and transgenic cloned embryos of goats during early development. (A) transcript levels of MBD1; (B) transcript levels of MeCP2. N: fertilized eggs; T: transgenic cloned embryos. 1-cell: single cell embryo; 2–4 cell: 2–4-cell blastomere; 8–16 cell: 8–16-cell blastomere; M: morula; B: blastocyst. Bars with different superscripts are statistically different (P < 0.05).

Placenta morphology analyse of transgenic cloned goats

The fetal weight of the normal goats (NG) and LTCG were lower than the DTCG, which was the opposite of the placentome number results (Table 2). The average placentome number of NG and LTCG was higher than that of DTCG. Moreover, the significantly variance displayed on the placentome at diameter 2 cm, 2–4 cm, 6–8 cm and >8 cm (Table 3).

Table 2 Fetal weight, placental weight, placentomes number of different groups

DTCG, dead transgenic cloned goats, LTCG, live transgenic cloned goats; NG, normal goats.

a,b Means with a, b within each column within each factor represent significant difference (P < 0.05).

Table 3 Number of placentomes in different diameters of different groups

DTCG, dead transgenic cloned goats; LTCG, live transgenic cloned goats; NG, normal goats.

a,b Means with a, b within each column within each factor represent significant difference (P < 0.05).

Placenta fetalis were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The histologic characteristics of placenta fetalis are shown in Fig. 4. In the trophoblastic epithelium, cylindrical cells arranged in palisades and numerous binucleate cells can be visualized. In addition, fetal mesenchyme, a connective lax tissue with elongated cores that is vascularized with blood vessels of diverse caliber, is located close to the epithelium.

Figure 4 Photographs of placenta stained with haematoxylin–eosin. BN: binucleate cells; BVs: blood vessels; FM: fetal mesenchyme; TE: trophoblastic epithelium.

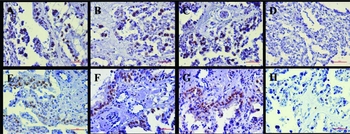

Protein localizations of MBD1 and MeCP2 in placenta fetalis of transgenic cloned goats

MBD1 and MeCP2 immunoreactivities were detected in binucleate cells of the trophoblastic epithelium (Fig. 5). In control sections, virtually no immunoreactivity was observed when normal rabbit serum was used in place of the primary antibody.

Figure 5 Protein localizations of MBD1 and MeCP2 in placentas. (A) MBD1-NG; (B) MBD1-LTCG; (C) MBD1-DTCG; (D) MBD1 control; (E) MeCP2-NG; (F) MeCP2-LTCG; (G) MeCP2-DTCG; (H) MeCP2 control. NG, Normal goats; LTCG, Live transgenic cloned goats; DTCG, Dead transgenic cloned goats; Control, the negative control. Positive signals appear brown in color, and counterstaining background appears blue in color.

Relative expression of MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA in placenta fetalis

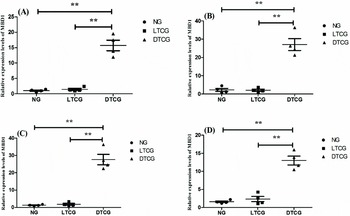

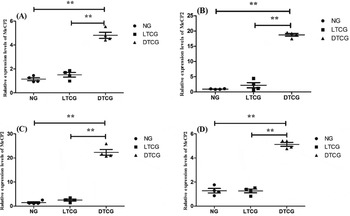

MBD1 expression levels of DTCG on placental cotyledons at diameter 2 cm, 2–4 cm, 4–6 cm and 6–8 cm were significantly higher than that of normal and LTCG (P < 0.05, Fig. 6). Analogously, in all placental cotyledons with different diameters, the total level of MeCP2 expression in DTCG was significantly higher than normal and LTCG (P < 0.05, Fig. 7).

Figure 6 MBD1 transcript levels in placental cotyledon with different diameters. (A) dia. ≤ 2 cm; (B) 2 cm < dia. ≤ 4 cm; (C) 4 cm < dia. ≤ 6 cm; (D) 6 cm < dia. ≤ 8 cm; **Represent extremely significant deviation (P < 0.01). NG, Normal goats; LTCG, Live transgenic cloned goats; DTCG, Dead transgenic cloned goats.

Figure 7 MeCP2 transcript levels in placental cotyledon with different diameters. (A) dia. ≤ 2 cm; (B) 2 cm < dia. ≤ 4 cm; (C) 4 cm < dia. ≤ 6 cm; (D) 6 cm < dia. ≤ 8 cm. **Represent extremely significant deviation (P < 0.01). NG, Normal goats; LTCG, Live transgenic cloned goats; DTCG, Dead transgenic cloned goats.

Discussion

In SCNT, active demethylation of donor somatic cell DNA shortly after nuclear transplantation is thought to be important for reprogramming subsequent embryonic development. MBD1 and MeCP2 are members of the MBD protein subfamily that bind methylated CpG. The DNA methylation pattern is believed to be ‘read’ by the conserved MBD family of proteins (Wade, Reference Wade2001; Jaenisch & Bird, Reference Jaenisch and Bird2003).

During embryonic preimplantation development, significant changes occur in DNA methylation amount and patterns (Santos & Dean, Reference Santos and Dean2004). A further passive loss of methylation has been observed as DNA replicates between the 2-cell and morula stages, with somatic cell levels being re-established at or after the blastocyst stage (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Niveleau, Walter, Fundele and Haaf2000; Bourc'His et al., Reference Bourc'His, Le Bourhis, Patin, Niveleau, Comizzoli, Renard and Viegas-Pequignot2001; Dean et al., Reference Dean, Santos, Stojkovic, Zakhartchenko, Walter, Wolf and Reik2001). In this study, MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA levels from fertilized eggs were further reduced with embryonic development to a minimum at the 8–16-cell stage, demonstrating the important role of MBD1 and MeCP2 in linking DNA demethylation with embryogenesis. These results are consistent with a number of previous studies on dynamic changes in the localization of five members of the MBD gene family during murine and bovine preimplantation embryo development (Ruddock-D'Cruz et al., Reference Ruddock-D'Cruz, Xue, Wilson, Heffernan, Prashadkumar, Cooney, Sanchez-Partida, French and Holland2008).

Discrepancies were detected between transgenic cloned embryos and fertilized eggs in MBD1 and MeCP2 mRNA levels during preimplantation development. In fertilization embryos, the phase of MBD1 and MeCP2 minimal expression was at 8–16-cell embryo stage. However, in transgenic cloned embryos, the timing of MBD1 minimal expression was postponed until the morula stage, and the time for MeCP2 minimal expression was advanced to the 2–4-cell embryo stage. During embryonic preimplantation development, at the time of the maternal to zygotic transition (MZT), DNA methylation is minimal, maternal transcripts are degraded and the newly formed embryo must begin transcription (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Santos, Stojkovic, Zakhartchenko, Walter, Wolf and Reik2001; Oswald et al., Reference Oswald, Engemann, Lane, Mayer, Olek, Fundele, Dean, Reik and Walter2000; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Niveleau, Walter, Fundele and Haaf2000). MBD proteins have been implicated in both global transcriptional regulation (Klose & Bird, Reference Klose and Bird2006) and, more specifically, in repression of Oct4, a pluripotency marker expressed during early embryogenesis (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Le Menuet, Chung and Cooney2006). These results suggested that there was a disorder timing for the regulation of MBD1- and MeCP2-mediated gene transcription, which affects the demethylation of donor somatic cells and maternal gene activation during early embryogenesis.

Normal embryos undergo demethylation, followed by remethylation, to achieve genome-wide methylation reprogramming in early preimplantation development (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Santos, Stojkovic, Zakhartchenko, Walter, Wolf and Reik2001). In particular, it might be significant if the inner cell mass (ICM) remains methylated because trophectoderm cells are the first differentiated cell type to form during development and trophoblast-specific gene expression is essential for embryonic nutrition and implantation (Beaujean et al., Reference Beaujean, Hartshorne, Cavilla, Taylor, Gardner, Wilmut, Meehan and Young2004). We found that MBD1 levels were extremely low in transgenic cloned embryos at the blastocyst stage, suggesting that MBD1 affects global remethylation of the embryonic genome, which may cause cloned embryo implantation failure.

After embryonic implantation, the placenta is designed to allow efficient exchange between the mother and fetus to optimize growth and development (Penninga & Longo, Reference Penninga and Longo1998). Furthermore, a correlation between placental size and litter weight has been determined, suggesting that smaller placentas are more efficient (Osgerby et al., Reference Osgerby, Gadd and Wathes2003; Konyalı et al., Reference Konyalı, Tölü, Daş and Savaş2007). In addition, the number of placentomes decreases under extreme conditions, such as malnutrition (Konyalı et al., Reference Konyalı, Tölü, Daş and Savaş2007).

Notable differences in fetal weight, placental weight, and placentome number and size were detected between live transgenic cloned (LTCG) and deceased transgenic cloned (DTCG) goats. Specifically, the LTCG fetal weight and placentome number values were significantly higher compared with the DTCG. However, the LTCG placental weight was lower than that in the DTCG. These results indicated that placental efficiency was reduced in DTCG, proving that placental dysfunction in transgenic cloned goats may lead to their death.

Similar to other ruminants, the goat has a characteristic placental epithelium with two morphologically and functionally distinct cell types: there are mononucleate and binucleate trophoblast cells in the trophectoderm (Igwebuike, Reference Igwebuike2009), which were observed in the HE staining analyses of placentas from transgenic goats. Binucleate cells produce hormones, such as placental lactogen and progesterone, and through a fusion process with an uterine epithelial cell or the fetomaternal syncytium, release their contents into maternal connective tissue (Wooding et al., Reference Wooding, Morgan, Monaghan, Hamon and Heap1996; Igwebuike, Reference Igwebuike2009). Binucleate cells are also involved in villi development (Wooding et al., Reference Wooding, Morgan, Monaghan, Hamon and Heap1996; Klisch et al., Reference Klisch, Wooding and Jones2010). Moreover, binucleate cells account for 15–20% of cells in the ovine trophectoderm for most of the gestation period. However, close to term, their numbers decrease concomitantly with increased fetal cortisol levels (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Wooding and Fowden2002). These studies revealed that binucleate cells are a unique feature in ruminants that have essential roles in placental development and function. Interestingly, MBD1 and MeCP2 proteins were strongly expressed in binucleate trophoblast cells, suggesting that MBD1 and MeCP2 may modulate the function of binucleate cells. Studies have shown that DNA methylation regulates placental lactogen I (PRL-I) gene expression, and MeCP2 overexpression could inhibit PRL-I gene expression (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kimura, Minami, Ohgane, Hattori, Tanaka and Shiota2001). In addition, lack of MBD1 in mice could cause placental hypoplasia and eventually lead to miscarriage (Li et al., Reference Li, Bestor and Jaenisch1992; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Skarnes and Bird1996). In this study, we found that MBD1 and MeCP2 expression levels in DTCG were higher compared with LTCG. These data suggest that MBD1 and MeCP2 expression or overexpression may be connected with the placental dysfunction and the death of transgenic cloned goats. However, the detailed mechanism needs to be further elucidated. A future study is needed in order to provide evidence of the direct role of MBD1 and MeCP2 during embryonic and placental development, possibly using modification of MBD1 and MeCP2 expression via overexpression or knockdown methods in donor cells.

In conclusion, MBD1 and MeCP2 likely have important roles in linking DNA demethylation and remethylation during embryogenesis. Aberrant MBD1 and MeCP2 expression was present in transgenic cloned embryos, which may cause embryo implantation to fail. Additionally, MBD1 and MeCP2 protein expression in binucleate cells highlights its possible role in placental development. MBD1 and MeCP2 overexpression was detected in the placentas from DTCG. These findings are presumably due to aberrant epigenetic nuclear reprogramming during SCNT, which may cause developmental insufficiencies and ultimately death in cloned transgenic goats.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the work of Jingang Wang for embryo transfer and goats raising, as well as thanking Lizhong Wang and Shan Lan for their technical assistance. This study was supported financially by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 31672422).