Introduction

Traditionally, production of sex-diagnosed embryos has required embryo biopsy, which significantly compromises viability of in vitro produced embryos and is economical only when these embryos can be transferred fresh (Hasler et al., Reference Hasler, Cardey, Stokes and Bredbacka2002). Furthermore, as some IVP protocols seem to favour male embryo development (see e.g. Bredbacka & Bredbacka Reference Bredbacka and Bredbacka1996, Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Larsen, Ramsign, Lovendahl, Räty, Peippo, Greve and Callesen2005), the number of good quality female embryos available for sex diagnosis may be relatively small. With sex-sorted spermatozoa, large numbers of embryos of the desired sex could be produced without the disadvantages of embryo biopsy (Seidel Jr, Reference Seidel2003). Nucleus breeding schemes (e.g. ASMO; Stranden et al., Reference Strandén, Korpiaho, Pakula and Mäntysaari2001; Korpiaho et al., Reference Korpiaho, Strandén and Mäntysaari2003), which are based on the use of embryo technology (both in vivo and in vitro embryo production), would benefit from the efficient production of calves of the desired sex. In addition, in the case of unpredicted slaughter of a genetically valuable heifer or cow, oocytes collected for IVP (Kananen-Anttila et al., Reference Kananen-Anttila, Lindeberg, Reinikainen, Kaimio, Peippo and Halmekytö2005, Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Weigel, Fricke, Rutledge, Leibfried-Rutledge, Matthews and Schutzkus2005) could be fertilized with sex-sorted spermatozoa to ensure offspring of the desired sex.

A few studies have reported in vitro embryo development results with X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa (Beyhan et al., Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999, Lu et al., Reference Lu, Cran and Seidel1999, Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lu and Seidel2003, Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007, Bermejo-Alvarez et al., Reference Bermejo-Alvarez, Rizos, Rath, Lonergan and Gutiérrez-Adán2008). Differences in developmental rates between female and male embryos produced with X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa have been reported (Beyhan et al., Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999). In other studies, however, kinetics of female and male embryo development were similar (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Cran and Seidel1999, Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lu and Seidel2003, Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007, Bermejo-Alvarez et al., Reference Bermejo-Alvarez, Rizos, Rath, Lonergan and Gutiérrez-Adán2008). Differential expression of developmentally important genes between embryos produced with sex-sorted and unsorted spermatozoa have also been observed (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007). To date only one study reported embryo quality data and the true sex ratio of embryos produced with X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007).

The aims of this study were to compare kinetics of fertilization, embryo production rates, embryo quality and sex ratio after in vitro fertilization of oocytes with commercially available cryopreserved flow cytometrically sorted X and Y spermatozoa. A specific aim was to evaluate the economical use of low-dose sex-sorted spermatozoa by limiting the number of sex-sorted spermatozoa doses to one per IVF and excluding an additional isolation step for motile spermatozoa.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

Cell culture dishes were purchased from Nunc and reagents and solutions from Sigma–Aldrich unless otherwise stated.

In vitro maturation (IVM)

Abattoir-derived ovaries of variety of breeds were transported to the laboratory at room temperature within 6 h of collection. Following aspiration and recovery of cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) only oocytes lacking cumulus cells, or having expanded cumulus cell masses, were discarded. The remaining COCs were washed twice with washing solution (Complete Ultra with 0.1% albumin and 25 mg/l kanamycin sulfate; ICPBio) and once in IVM medium. For maturation approximately 50 COCs were placed into 500 μl of maturation medium prepared on a 4-well dish without oil. In the middle of the 4-well dish 1 ml of sterile water was added to provide humidity. The maturation medium was TCM199 with Glutamax (Gibco BRL, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco BRL), 0.25 mM sodium pyruvate, penicillin–streptomycin, 2 μg/ml FSH (Ovagen, Bodinco B.V.), 10 μg/ml LH and 1μg/ml β-estradiol. Immature oocytes were matured for 24 h.

In vitro fertilization (IVF)

X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted spermatozoa from a single bull were purchased from Cogent Ltd. According to the supplier, there were 2 million spermatozoa in each X and Y dose. Unsorted control semen straws from England each contained 15 million spermatozoa.

Straws were thawed for 1 min in a 37 °C water bath. Only one straw of the X-sorted and one of the Y-sorted spermatozoa were used to fertilize each batch of abattoir-derived oocytes. An unsorted control straw of the same bull was cut into halves under liquid nitrogen before thawing and the remaining half was enclosed in a larger straw and kept in liquid nitrogen for the next run.

All emptied straws were washed with 1 ml of sperm-TL (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Susko-Parrish, Winer and First1988) to make sure that all spermatozoa were recovered. The content of each straw was washed twice by centrifugation at 450 g in 4 ml of sperm-TL at room temperature. The motility of the recovered spermatozoa from each straw was estimated visually under a phase contrast microscope.

The number of spermatozoa recovered from each straw was calculated using a counting chamber. As the numbers of spermatozoa obtained from X-sorted and Y-sorted straws were the limiting factors, along with the number of Y-sorted spermatozoa straws available for this study, unsorted concentration was fixed according to the most diluted sex-sorted spermatozoa group. Subsequently, the spermatozoa concentration was equal among the different groups within each IVP run, but varied between IVP runs (ranges: 0.556 × 106 to 1.08 × 106 spermatozoa/ml and 2224 to 6750 spermatozoa/oocyte).

After maturation, COCs were washed twice with washing solution and once in IVF medium (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Susko-Parrish, Winer and First1988), which was prepared without glucose (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Susko-Parrish and First1989). The final heparin concentration was 10 μg/ml. After washing, 80–130 COCs were transferred to 500-μl IVF drops prepared on a 4-well dish without oil. In the middle of the 4-well dish 1 ml of sterile water was added to provide humidity. After addition of the spermatozoa each IVF drop was supplemented with penicillamine (2 μM), hypotaurine (10 μM) and epinephrine (1 μM). Matured oocytes and spermatozoa were co-incubated for 20 h.

In vitro culture (IVC)

After fertilization, cumulus cells were removed from the presumptive zygotes by vortexing (90 s) in washing medium. Approximately 20 presumptive zygotes were sampled from each group to count the number of pronuclei. The remaining zygotes were washed twice in washing solution and once with IVC medium before culture. The culture medium was SOFaaci (Holm et al., Reference Holm, Booth, Schmidt, Greve and Callesen1999) supplemented with fatty acid free BSA (4 mg/ml, cat # A8806). Culture volume was 1 μl/zygote under oil (MediCult, Cat # 1010050). The culture groups were X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa, sorting control and unsorted spermatozoa. In the sorting control group equal numbers of zygotes fertilized with the X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa were pooled after fertilization to evaluate the possible IVC condition derived differences in the development between the sexes. Cleavage rates were recorded at approximately 40 hpi and the zygotes that had not yet cleaved were removed from the culture drops. Half of the culture volume was replaced on day 5 of culture with fresh culture medium. Blastocyst numbers were recorded at days 7, 8 and 9 post-insemination.

IVM, IVF and IVC culture set up

All in vitro embryo production steps were carried out in Modular incubator chambers (MIC-101, Billups-Rothenberg Inc.) placed inside regular CO2 incubators for temperature control at 39 °C. For IVM and IVF, the oxygen level was 20% and for IVC 5%. Three large open Petri dishes filled with sterile water were placed inside the chamber to provide maximum humidity.

Pronuclei and sperm aster analyses

To evaluate the success of fertilization and the proportion of normally fertilized oocytes, the pronuclei were counted under UV illumination after staining the zygotes at 20 hpi with 3 μg/ml of Hoechst 33258 and 15% ethanol in PBS for 12 to 48 h at 4 °C in the dark.

For sperm aster analysis, oocytes fertilized with X-sorted (n = 57), Y-sorted (n = 48) and unsorted (n = 53) spermatozoa were collected at 10 hpi from two IVP runs. For this study, the spermatozoa concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106/ml and 5000/oocyte in each IVF group to achieve a constant IVF environment for detailed analysis of fertilization kinetics. In sperm aster analysis we followed the protocol of Navara et al. (Reference Navara, First and Schatten1994) with modifications. The treatments for the sperm aster analysis were performed on 4-well dishes in 0.5 to 1 ml volumes except for the primary and secondary antibodies and for the pronuclei staining where 96-well dishes and 0.1 to 0.2 ml volumes were used. The incubations were carried out at 39 °C unless otherwise stated. The specificity of the sperm aster analysis was controlled by omitting the primary antibody in some zygote samples (negative control).

The cumulus cells were removed by vortexing the inseminated oocytes in prewarmed (39 °C) microtubule stabilizing buffer (PHEM: 18 mg/ml PIPES, 6.5 mg/ml HEPES, 3.8 mg/ml EGTA, 0.99 mg/ml MgSO4, pH adjusted to 7.0 with 1 N KOH) containing 0.5–1 mg/ml hyaluronidase and 4 mg/ml PVP. Thereafter, the zona pellucidae of the zygotes were removed with 0.25% w/v protease in 0.1 M PBS and the zygotes were left to recover for 45–60 min in Holding solution (ICPbio.). The cell membranes of the zygotes were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PHEM for 3 to 4 min. In the next step, the zygotes were fixed in PHEM containing 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 15 min. The non-specific background fluorescence was quenched by NaBH4 treatment (1 mg/ml in 0.1 M PBS, pH 8.0) and the non-specific binding of the antibodies was blocked by incubating the zygotes in 0.1 M PBS with 20% normal goat serum (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) for 1–4 days at 4 °C. The primary antibody was mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin (clone E7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, USA) diluted 1:4 in 0.1 M PBS containing 5% goat serum and it was incubated with the zygotes for 1 h. The secondary antibody was FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Zymed) diluted 1:100 in 0.1 M PBS containing 5% goat serum and incubated for 1 h in the dark. The pronuclei of the zygotes were stained with Hoechst 33342 (10–30 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (10 to 20 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally the zygotes were transferred on to microscope slides in a drop of anti-fading reagent (Mounting Medium, Inova Diagnostics Inc.) and a cover slip was attached without squeezing the zygotes. The slides were stored at 4 °C in the dark until analysed with epifluorescence and confocal laser microscopy. The number of pronuclei in each zygote was recorded according to the epifluorescence and confocal images. The diameters of the paternal pronucleus and the sperm aster structure were measured from the confocal images using image-processing software (Olympus DP-soft). Only the zygotes with two pronuclei and one sperm aster structure were depicted as normally fertilized and included in the comparisons of pronucleus and sperm aster diameters in the four experimental groups. The quality of sperm asters was evaluated from the images received after confocal microscopy and defined as follows: (1) two or more sperm aster structures; (2) one diffuse, not measurable sperm aster structure; and (3) one distinct, measurable sperm aster structure (Navara et al., Reference Navara, First and Schatten1996). The same person did the analyses throughout the experiment.

Quality and sex ratio of embryos

Each day of collection (days 7, 8 and 9 post insemination) the number and quality (IETS quality coding: 1 excellent–good, 2 fair, 3 poor, 4 dead or degenerated; Robertson and Nelson, Reference Robertson, Nelson, Stringfellow and Seidel1998) of blastocysts were recorded prior to the collection for sexing. Day 7 to 8 embryos having qualities 1–3 were considered to be transferable. For sexing, the zona pellucidae were removed in Tyrode's acid solution (pH 1.8). The sexing was carried out according to Bredbacka and Peippo (Reference Bredbacka and Peippo1992). On day 9, also the remaining cleaved zygotes considered as IETS quality 4 were collected for sexing.

Differential staining of expanded blastocysts

Day 7 and 8 expanded blastocysts (qualities 1 to 3) from one IVP run were subjected to differential staining to evaluate the ICM:TE ratio. The differential staining method used in this study (Korhonen et al., Reference Korhonen, Kananen, Ketoja, Matomäki, Halmekytö and Peippo2008) was based on work published by Thouas et al. (Reference Thouas, Korfiatis, French, Jones and Trounson2001) with modifications (Bredbacka, P., personal communication).

Before staining, embryos were grouped according to stage of development and quality. In the first step, embryos were incubated in Hoechst 33342 solution (PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ supplemented with 4 mg/ml BSA and 25 μg/ml Hoechst 33342) for 2 h at 39 °C. In the second step, trophectodermal cells were permeabilized in Permeabilization Buffer (formula provided by FinnZymes Oy) for 2.5 min at room temperature followed by two washes in PBS (with Ca2+ and Mg2+) supplemented with 4 mg/ml BSA. In the third step, embryos were incubated in propidium iodide solution (PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ supplemented with 4 mg/ml BSA and 10 μg/ml propidium iodide) for 20 min at room temperature followed by a wash in PBS (with Ca2+ and Mg2+) supplemented with 4 mg/ml BSA. Stained embryos were mounted on the objective slides with antifade solution (FluorGuard™ Antifade Reagent, Bio-Rad) and the ICM:TE ratio was assessed under UV illumination. The proportions of ICM cells were calculated by dividing the number of blue cells by the total cell number using an inverted phase contrast microscope (Olympus XI70) fitted with an ultraviolet lamp and excitation filter (460 nm for blue and pink fluorescence).

Statistical analyses

The experimental design was a randomized complete block design in which IVP run was considered as a blocking factor and X, Y, X+Y and unsorted spermatozoa were the four treatment groups. Variables describing fertilization and embryo development rates and quality followed binomial distributions and therefore were analysed using conditional logistic regression, taking into account the effects of IVP and the four treatments (Collett Reference Collett2003; CYTEL Software Corporation, 2002). These analyses were performed using LogXact 5 (CYTEL Software Corporation). The pair-wise differences between treatments were quantified using estimated odds ratios and tested using two-sided asymptotic tests. Odds ratio (OR) is the ratio of the odds (p/(1 – p)) that an event will occur in one group to the odds that the event will occur in the other group (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Secic and Huth1997). For example, when comparing the proportion of penetrated oocytes in treatments X and unsorted control sperm an estimated odds ratio of 0.14 is obtained, which means that in X the ratio of penetrated compared with unpenetrated is 0.14 times the same ratio in unsorted control sperm, i.e. the odds of penetration in treatment X are 0.14 times the odds of penetration in unsorted control sperm. If the direction of comparison needs to be changed, a converted odds ratio can be calculated as 1/original odds ratio. The OR comparing unsorted to X would then be obtained as 1/0.14 = 7.14. The interpretation is then the opposite: in the unsorted control the odds of penetration is 7.14 times the odds of penetration in X sperm. In the results section the presented estimated odds ratios are in some cases obtained as such converted odds ratios from the estimated odds ratios presented in Tables 2, 4 and 7.

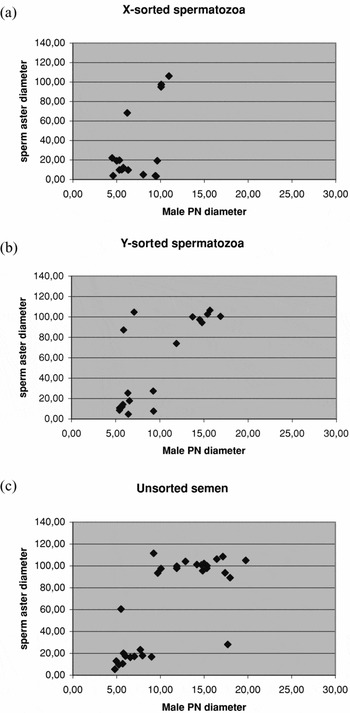

The sperm aster data were derived from two IVP runs, i.e. two levels of the blocking factor. Therefore, IVP was included in the model as a fixed factor in addition to the fixed treatment factor. Sperm aster diameters were categorized into large (≥60 μm) or small (<60 μm), because the data were clearly divided into two distinct groups (Figure 1). Due to the small sample size, exact conditional logistic regression (Agresti Reference Agresti2002) was applied. This analysis was performed using the LOGISTIC procedure of SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute). The pair-wise differences between treatments were quantified using estimated odds ratios and tested using two-sided exact tests.

Figure 1 Distribution of sperm aster and male pronuclei diameters in X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted spermatozoa groups.

Male pronuclei diameters were analysed using analysis of variance for a randomized complete block design with factorial treatments (treatment group and size of sperm aster) by considering IVP run as a fixed blocking factor (Littell et al., Reference Littell, Milliken, Stroup and Wolfinger1996). The model was fitted using the MIXED procedure of SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute). Pair-wise comparisons were performed with two-sided t-type tests.

Total cell numbers of day 7–8 expanded blastocysts and the corresponding ICM proportions were calculated from one IVP run. Thus, the data were analysed using a two-way analysis of variance. In the statistical model the fixed effects of sperm, day and their interaction were taken into account. The model was fitted using the MIXED procedure of SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

Kinetics of fertilization

A total of 573 fertilized oocytes were stained to evaluate the rate of successful fertilizations (Tables 1, 2). According to analysis of pronuclei (at 20 hpi), penetration rates (≥2 pronuclei) were compromised in the X-sorted group (mean 58.0%) when compared with the Y-sorted (89.8%) and unsorted (90.0%) groups (estimated odds ratios (OR): 0.15, p < 0.001 and 0.14, p < 0.001, respectively). Penetration rates correlated negatively with normal fertilization rates. The proportions of zygotes having normal fertilization with two pronuclei were smaller (OR: 0.56, p = 0.04 and 0.62, p = 0.07, respectively) in the Y-sorted (59.7%) and unsorted groups (61.5%) compared with the X-sorted group (73.3%).

Table 1 Mean penetration and normal fertilization rates at 20 hpi.

a2PN + >2PN/all examined oocytes.

b2PN/penetrations.

Table 2 Comparisons between treatments in penetration and normal fertilizations.

a2PN + >2PN/all examined oocytes.

b2PN/penetrations.

At 10 hpi, 17, 19 and 30 zygotes that were considered normally fertilized (2 pronuclei, 1 sperm aster) for the X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted groups, respectively, were subjected to measurements of sperm aster and male pronuclei diameters. Because the data were not normally distributed (Fig. 1), they were classified within each sperm group as small (<60 μm) and large (≥60 μm) asters. The proportion of the large sperm asters from all asters measured were 26.7%, 46.0% and 56.1% for the X, Y and unsorted groups, respectively. The differences in the proportion of the large sperm asters between the experimental groups were not significant.

Average male pronuclei diameters (μm, estimated means ± SE) were 7.99 ± 0.97, 10.05 ± 0.78 and 10.37 ± 0.73 for the X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted groups, respectively. The differences between treatments in the male pronuclei diameters depended on the size of sperm aster (large or small). The male pronuclei diameters of the X-sorted group zygotes were significantly smaller than those of the Y-sorted and unsorted semen group zygotes (p < 0.05), but only when the sperm aster was classified as large.

The average qualities of the sperm asters were good in the X-sorted and unsorted groups: 3.00 and 2.98, respectively. The quality of the sperm asters was more compromised in the Y-sorted group (2.53).

Development rates and qualities of embryos

In total, 4569 oocytes in nine batches were matured, fertilized and cultured in vitro. Three additional IVP batches were omitted from the final analyses due to technical problems (e.g. bacterial contamination) during IVP.

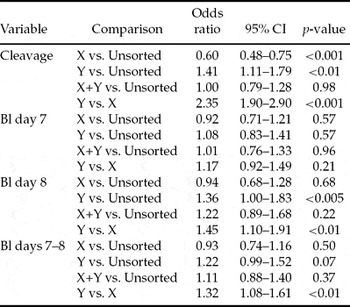

Cleavage rate was lowest (65.3%) in the X-sorted group (OR: 0.60, p < 0.001) and highest (81.5%) in the Y-sorted group (OR: 1.41, p < 0.01) when compared with the unsorted group (75.0%) (Tables 3, 4). No differences were recorded in the cleavage rates between the unsorted and sorting control groups (75.0% vs. 75.9%). More transferable day 7–8 embryos (OR: 1.32, p < 0.01) were produced from oocytes fertilized with the Y-sorted spermatozoa (31.9%) than from the ones fertilized with the X-sorted spermatozoa (26.4%) (Tables 3, 4). There were no differences between the sorting control and unsorted groups (29.6% vs. 27.7%). On day 7, no significant differences were observed in the proportion of blastocyst obtained between any of the groups (X: 15.5%, Y: 17.4%, sorting control: 16.6%, unsorted: 15.9%). On day 8, more embryos were recovered from the Y-sorted group (14.5%) compared with the X-sorted (10.9%) or unsorted (11.8%) groups (OR: 1.45, p < 0.01 and 1.36, p < 0.005, respectively). The difference between the sorting control group (12.9%) and unsorted group (11.8%) was not significant on day 8. If the differences in fertilization rates between the groups were ignored, i.e. blastocyst rate defined as blastocysts/cleaved zygotes, there were no significant differences between any of the groups on days 7–8 (results not shown). Only 12.7%, 10.6%, 10.8% and 9.6% of the blastocysts were obtained on day 9 from the X-sorted, Y-sorted, sorting control and unsorted groups, respectively (Table 7).

Table 3 B Mean cleavage (at 40 hpi) and blastocyst rates of zygotes placed in culture.

Table 4 Comparisons between spermatozoa groups in cleavage (at 40 hpi) and blastocyst rates of zygotes placed in culture.

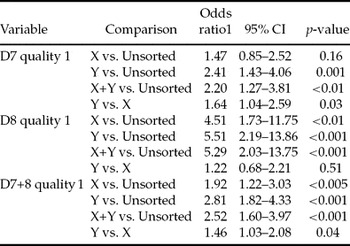

On days 7–8, the proportion of quality 1 embryos was smallest (19.0%) in the unsorted group compared with the X (30.6%), Y (38.9%) and sorting control (36.0%) groups (OR: 0.52, p < 0.005, 0.36, p < 0.001 and 0.40, p < 0.001, respectively) (Tables 5, 6). Furthermore, the proportion of quality 1 embryos was higher in the Y-sorted (38.9%) than in the X-sorted (30.6%) group (OR: 1.46, p = 0.04; Table 6). On day 7, the proportion of quality 1 embryos recovered from the unsorted group was lower than that derived from the Y-sorted and sorting control groups, but did not differ significantly from the X-sorted group (Table 6). More quality 1 embryos were produced with the Y-sorted (47.1%) than X-sorted (35.6%) spermatozoa (OR: 1.64, p = 0.03; Table 6). On day 8, the proportion of quality 1 embryos recovered from the unsorted group was lower than that from any other group (Table 7). The difference between the X-sorted and Y-sorted groups was not significant.

Table 5 Mean day 7–8 transferable embryo quality.

Table 6 Comparisons between treatments in quality 1 blastocyst rates.

Table 7 Mean kinetics and quality of blastocyst development.

aBlastocysts/zygotes placed in culture.

After differential staining the estimated average total cell numbers (±SE) of day 7–8 expanded blastocysts were 127.6 ± 11.67, 95.7 ± 10.19 and 123.7 ± 9.36 for the X-sorted (n = 7), Y-sorted (n = 8) and unsorted (n = 9) groups, respectively. The differences between the groups were not statistically significant. Corresponding average ICM proportions (±SE) were 25.7 ± 1.91, 23.6 ± 1.67 and 25.7 ± 1.53 for the X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted control groups, respectively. The differences between the groups were not statistically significant.

The total cell count was significantly higher (p < 0.05) on day 7 compared with day 8 within each group (X: 134.6 ± 12.48 vs. 120.5 ± 19.73; Y: 106.8 ± 12.48 vs. 84.7 ± 16.11; unsorted: 144.6 ± 12.48 vs. 102.8 ± 13.95). ICM proportions were not significantly different within groups between days 7 and 8 (X: 26.4 ± 2.04 vs. 24.9 ± 3.23; Y: 23.3 ± 2.04 vs. 23.9 ± 2.64; unsorted: 27.6 ± 2.04 vs. 23.9 ± 2.28).

Sex ratio of embryos

On average (means ± SD), 12.6 ± 7.76% and 10.1 ± 4.81% of day 7–8 embryos were of the undesired sex among oocytes fertilized with the X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa, respectively. The percentage of embryos of undesired sex varied between the IVP batches, being from 0 to 21% and from 3 to 16% for the X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa, respectively. In the unsorted group, 46.2 ± 10.06% and 51.3 ± 11.37% of the transferable embryos were male and female, respectively. In the sorting control group 52.2 ± 15.61% and 46.3 ± 15.09% of the transferable embryos were male and female, respectively.

At day 9, the proportion of males from cleaved embryos (≥2 cell stage) was 7.0, 72.3, 40.2 and 38.4 for the X-sorted, Y-sorted, sorting control and unsorted groups, respectively. Within the X-sorted, Y-sorted, sorting control and unsorted groups, 94.6%, 89.1%, 89.6% and 85.3% of the embryos were sexed successfully, respectively.

Discussion

We aimed to evaluate the effect of cryopreserved low-dose sex-sorted X and Y spermatozoa on subsequent fertilization, cleavage and blastocyst rates, as well as, transferable embryo quality and sex ratio. In general, the rate of transferable embryo production was not compromised and the developmental kinetics of zygotes was not significantly affected by the use of sex-sorted spermatozoa compared with the use of unsorted semen (sorting control vs. unsorted semen group in Tables 3, 4). Embryo quality was significantly better in the sorting control group compared with the unsorted group (Tables 5–7). Thus, according to our results, sex sorting and cryopreservation of spermatozoa did not affect embryo production rates and quality. These results were, however, obtained using a single bull and may not therefore apply to sex-sorted semen from an entire bull population or breed.

Differences were, however, obtained between the X-sorted and Y-sorted groups. Oocytes fertilized with the Y-sorted spermatozoa had higher penetration and cleavage rates and produced more transferable embryos of better quality by day 8 than oocytes fertilized with the X-sorted spermatozoa. With regard to developmental kinetics, on day 7 no differences were recorded in embryo production rates between the X-sorted and Y-sorted groups. On day 8 significantly more transferable embryos were produced from oocytes fertilized with the Y-sorted spermatozoa than from oocytes fertilized with the X-sorted spermatozoa, reflecting delayed development of zygotes produced with Y-sorted spermatozoa perhaps due to higher levels of polyspermy. As no differences between the X-sorted and Y-sorted groups were observed as the differences in fertilization rates were ignored (blastocyst rate defined per cleaved oocytes, results not shown) and as the sex ratio of transferable embryos from the sorting control group did not deviate from the expected, it seems that this observation was not due to a ‘culture effect’, i.e. in vitro culture conditions favouring male embryo development. Rather, X-sorted spermatozoa penetrated oocytes less efficiently as evidenced by sperm aster data and reduced numbers of fertilized oocytes and cleaved zygotes. The large sperm asters associated with significantly smaller male pronuclei in the zygotes fertilized with the X-sorted spermatozoa indicate different kinetics of fertilization for the X-sorted versus Y-sorted spermatozoa or unsorted spermatozoa for this bull.

Beyhan et al. (Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999) reported dimorphic development of zygotes fertilized with X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa. In their study, zygotes produced with Y-sorted spermatozoa had larger sperm asters of better quality at 12 hpi compared with zygotes produced with X-sorted spermatozoa. Aster sizes and qualities of unsorted semen were intermediate between the two sex-sorted spermatozoa groups and there were no significant differences in male pronuclei diameters between the groups. As at a given time point the male pronuclei diameters reflect kinetics of fertilization and the sperm aster diameters and qualities reflect fertility of the semen (Navara et al., Reference Navara, First and Schatten1996), there were no differences in timing of fertilization between the respective experimental groups, but the quality of the Y-sorted spermatozoa was better than that of the X-sorted spermatozoa (Beyhan et al., Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999). In our study, in contrast, the quality of the X-sorted spermatozoa appeared better (better quality sperm asters) compared with the quality of the Y-sorted spermatozoa, although fertilization was delayed (small male pronuclei diameters).

Despite implications of compromised spermatozoa quality and a high rate of polyspermy after fertilization, Y-sorted spermatozoa produced quantitatively and qualitatively the best embryos in this study. Morphological quality of transferable embryos was best in the Y-sorted spermatozoa group at every time point. Surprisingly, unsorted semen produced the worst embryos in this study, although equally high rates of polyspermy were found in the Y-sorted and unsorted group. Only one bull was used in our study and IVF conditions (e.g. spermatozoa and heparin concentration) were not optimized in advance because of the limited number of spermatozoa doses available. Selected heparin concentration may have been too high, as evidenced by high rates of polyspermy in the Y-sorted and unsorted groups. On the other hand, with lower heparin concentrations fertilization rates with the X-sorted spermatozoa might have been even lower. Fertilization rates have been shown to correlate positively with blastocyst rate in cattle (Alomar et al., Reference Alomar, Mahieu, Verhaeghe, Defoin and Donnay2006). High rates of polyspermy, however, may explain subsequent delayed development of embryos (Kawarsky et al., Reference Kawarsky, Basrur, Stubbings, Hansen and King1996).

Use of gradient separation on fresh sex-sorted semen in IVF has resulted in good day 7–8 blastocyst rates (X-sorted 26% and Y-sorted 28%; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Cran and Seidel1999). Zygotes produced with frozen–thawed gradient separated X and Y spermatozoa have not, however, reached similar blastocyst rates (X-sorted 17.3% and Y-sorted 16.9%; K. Morton, personal communication). Beyhan et al. (Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999) did not isolate live spermatozoa when using fresh sex-sorted spermatozoa and obtained good blastocyst rates (X-sorted: 27% and Y-sorted 27%). In addition, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Guo, Su, Nedambale, Zhang, Schenk, Moreno, Dinnyés, Ji, Tian, Yang and Du2006) produced female embryos with X-sorted frozen–thawed spermatozoa from one of the bulls without an additional isolation step with good blastocyst rates (22% on day 7). As additional isolation steps increase the volume of sex-sorted semen required per IVF, it is advantageous if such a step is not necessary.

We did not use swim-up or gradient separation to isolate motile spermatozoa, therefore poor quality spermatozoa were also used for fertilization and the actual proportion of motile spermatozoa was much lower that the total number added. In addition, the spermatozoa concentration varied between IVP batches in this study for practical reasons. The total number of spermatozoa added per oocyte did not however seem to affect penetration, polyspermy, cleavage or blastocyst rates (results not shown). Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Guo, Su, Nedambale, Zhang, Schenk, Moreno, Dinnyés, Ji, Tian, Yang and Du2006) reported that only 600 spermatozoa per oocyte are enough for successful fertilization when no additional isolation step is used. In our study, the lowest number of spermatozoa per oocyte was just above 2000. As motile spermatozoa were not separated in our study, the actual number of spermatozoa able to fertilize were on average 30%, 30% and 50% for X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted spermatozoa, respectively.

In this study, approximately 50% of the embryos were obtained on day 7, 40% on day 8 and 10% on day 9 for all spermatozoa groups (Table 7). Delayed development was correlated with poor embryo quality (Table 7) and may have resulted from high rates of polyspermy (Kawarsky et al., Reference Kawarsky, Basrur, Stubbings, Hansen and King1996). Already from day 7 to day 8 the proportion of quality 1 embryos dropped 12, 18 and 20 percentage units in X-sorted and Y-sorted and unsorted groups, respectively. The corresponding differences between days 7 and 9 were even greater: 33, 43 and 40 percentage units for X-sorted and Y-sorted and unsorted groups, respectively. Morton et al. (Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007) did not report significant differences in the proportion of grade 1 embryos between X-sorted, Y-sorted and unsorted groups. Many authors have, however, reported delayed embryo development with sex-sorted spermatozoa compared with unsorted semen (Beyhan et al., Reference Beyhan, Johnson and First1999, Lu et al., Reference Lu, Cran and Seidel1999, Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007). As various culture systems are involved, comparison of the results between experiments is difficult. Using SOF in IVC, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Fricke, Leibfried-Rutledge, Rutledge, Penfield and Weigel2006) reported a day 8 blastocyst rate of 12.2% (quality 1 38.9%, quality 2 41.7% and quality 3 19.4%) with frozen–thawed X-sorted spermatozoa. Our unsorted IVP control bull of proven in vitro fertility, which was included in three IVP runs of this study, produced more transferable embryos than the other experimental groups (35.2%; quality 1 19.5%, quality 2 41.4%, quality 3 39.1%). Significant variation in cleavage, morulae and blastocyst rates between bulls has been reported both before and after flow-cytometrical sorting (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lu and Seidel2003, Xu et al., Reference Xu, Guo, Su, Nedambale, Zhang, Schenk, Moreno, Dinnyés, Ji, Tian, Yang and Du2006). Therefore, results from one study may not be comparable to other studies using different bulls.

Within both the X-sorted and Y-sorted group, on average, nine out of ten transferable embryos were of the predicted sex. There was, however, variation among IVP batches. In other studies where embryos were diagnosed for sex, the proportion of embryos of predicted sex was higher (96%; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Guo, Su, Nedambale, Zhang, Schenk, Moreno, Dinnyés, Ji, Tian, Yang and Du2006, Morton et al., Reference Morton, Herrmann, Sieg, Struckmann, Maxwell, Rath, Evans, Lucas-Hahn, Niemann and Wrenzycki2007), which may be a result of purity adjustments during the separation process.

It is concluded that acceptable embryo developmental rates can be reached in vitro with low-dose sex-sorted spermatozoa without an additional isolation step for motile spermatozoa. However, the results show that X-sorted and Y-sorted spermatozoa may not be equivalent in terms of embryo yield and quality. However, variation in the success of sorting among bulls may give different results from studies using only a single bull.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Marko Kallio (VTT) for technical advice on sperm aster immunohistochemistry. Development Manager Peter Bredbacka (FinnZymes Oy) is greatly acknowledged for the help with the differential staining. Tuula-Marjatta Hamama (MTT) and Elina Reinikainen (University of Kuopio) are thanked for excellent technical assistance during in vitro embryo production. This study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.