Introduction

To date, more than 5 million pregnancies have been conceived by in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures worldwide (Wang and Sauer, Reference Wang and Sauer2006). Since the first live birth by IVF in 1976, the efficiency of this procedure has been enhanced over time, increasing pregnancy rates and decreasing the number of embryos transferred in each cycle (Wade et al., Reference Wade, MacLachlan and Kovacs2015). The number of children born by this technique remains low, however, and it has been reported that babies born by assisted reproductive techniques suffer more perinatal complications compared with babies conceived naturally (Wang and Sauer, Reference Wang and Sauer2006).

Previous studies have established that chromosome abnormalities are common during early development in humans embryos generated by IVF procedures (Vanneste et al., Reference Vanneste, Voet, Le Caignec, Ampe, Konings, Melotte, Debrock, Amyere, Vikkula, Schuit, Fryns, Verbeke, D’Hooghe and Moreau2009). The reason for the high incidence in chromosome abnormalities is still unknown, however culture conditions and hormonal stimulation might influence the incidence of aneuploidy in human embryos (Munné et al., Reference Munné, Magli, Adler, Wright, De Boer, Mortimer, Tucker, Cohen and Gianaroli1997; Weghofer et al., Reference Weghofer, Munné, Brannath, Chen, Tomkin, Cekleniak, Garrisi, Barad, Cohen and Gleicher2008). Furthermore, more de novo chromosomal abnormalities have been detected prenatally in children conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) compared with in the newborn population conceived naturally (Bonduelle et al., Reference Bonduelle, Van Assche, Joris, Keymolen, Devroey, Van Steirteghem and Liebaers2002; Okun and Sierra, Reference Okun and Sierra2014). The increase in chromosomal abnormalities in embryos could be a potential cause of low pregnancy rates in women of an advanced maternal age (>35 years) who have been subjected to IVF procedures (Wilton, Reference Wilton2002).

Prenatal diagnosis techniques or preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) are used for genetic analysis of embryos before the time of embryo transfer (Dahdouh et al., Reference Dahdouh, Balayla, Audibert, Wilson, Audibert, Brock, Campagnolo, Carroll, Chong, Gagnon, Johnson, MacDonald, Okun, Pastuck and Vallée-Pouliot2015). Transfer of only euploid embryos has been established as a method that increases implantation and live birth rates and decreases gestational losses (Mastenbroek et al., Reference Mastenbroek, Twisk, van Echten-Arends, Sikkema-Raddatz, Korevaar, Verhoeve, Vogel, Arts, de Vries, Bossuyt, Buys, Heineman, Repping and van der Veen2007). More recent studies, however, have demonstrated that transfer of only euploid embryos is not always consistent. Grifo and colleagues described that single thawed euploid embryo transfer (STEET) generated a higher implantation rate compared with transfer of embryos produced by routine IVF, but no differences were observed in the clinical pregnancy rate between both groups (Grifo et al., Reference Grifo, Hodes-Wertz, Lee, Amperloquio, Clarke-Williams and Adler2013). Despite that finding, STEET significantly reduced the multiple gestation rate compared with routine IVF (Grifo et al., Reference Grifo, Hodes-Wertz, Lee, Amperloquio, Clarke-Williams and Adler2013). Similarly, Munné and colleagues determined that transfer of euploid embryos selected by next-generation sequencing (NGS) did not improved overall pregnancy outcomes in all women (Munné et al., Reference Munné, Kaplan, Frattarelli, Child, Nakhuda, Shamma, Silverberg, Kalista, Handyside, Katz-Jaffe, Wells, Gordon, Stock-Myer and Willman2019). A significant increase was only observed in ongoing pregnancy rate per embryo transfer when PGT-A was used in a subgroup of women aged 35–40 years (Munné et al., Reference Munné, Kaplan, Frattarelli, Child, Nakhuda, Shamma, Silverberg, Kalista, Handyside, Katz-Jaffe, Wells, Gordon, Stock-Myer and Willman2019). Although PGT-A might not improve pregnancy significantly and live birth rate in all cases, is still a useful tool to reduce multiple gestation rate and enhance pregnancy rate in older women. Analysis by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) determines any quantitative deviation (gain or loss of DNA sequences). This technique can detect any alteration in chromosome copy number (trisomy or monosomy) and unbalanced chromosome translocations (Munné, Reference Munné2012). For this reason, aCGH analysis is still one of the most used techniques for selection of euploid embryos

Conversely, the culture medium of human embryos contains gDNA and mtDNA (Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013). Total DNA and mtDNA concentrations have been correlated with an increase in embryo fragmentation, but a correlation between gDNA and embryo fragmentation has not been observed (Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013). The reason why gDNA is detected in the culture medium of human embryos is still unknown (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Yang, Zhao, Xiong, Guo, Xiao, Chen, Song, Wang, Chen, Xiao, Yao and Cai2019). One study evaluate the presence of gDNA in culture medium of human embryos for their genetic diagnosis by NGS (Capalbo et al., Reference Capalbo, Romanelli, Patassini, Poli, Girardi, Giancani, Stoppa, Cimadomo, Ubaldi and Rienzi2018), however based on NGS analysis the culture medium had increased discordance compared with blastocoel fluid samples that may have been due to maternal DNA contamination in the culture medium (Capalbo et al., Reference Capalbo, Romanelli, Patassini, Poli, Girardi, Giancani, Stoppa, Cimadomo, Ubaldi and Rienzi2018). For these reasons, more studies are needed to improve the use of culture medium for genetic diagnosis of human embryos.

In addition, participation of different extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the intercellular communication of several types of cells has been described (Dragovic et al., Reference Dragovic, Gardiner, Brooks, Tannetta, Ferguson, Hole, Carr, Redman, Harris, Dobson, Harrison and Sargent2011). Three principal types of EVs have been described: (i) apoptotic bodies (ABs; 500 nm to 3 μm in diameter), which are released by cells undergoing apoptosis; (ii) microvesicles (MVs, 100 nm to 1 μm), which are generated from the plasma membrane; and (iii) nanovesicles (30–100 nm), including exosomes (Exo), which are generated in the multivesicular bodies of the endosomes and released via exocytosis (Dragovic et al., Reference Dragovic, Gardiner, Brooks, Tannetta, Ferguson, Hole, Carr, Redman, Harris, Dobson, Harrison and Sargent2011). Exosomes are implicated in intercellular exchange of proteins, metabolites, lipids, mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, viral RNA, mtDNA and gDNA (Kalluri and LeBleu, Reference Kalluri and LeBleu2016). Microvesicles and exosomes are involved in embryo–maternal communication and also in gamete maturation, fertilization, embryo development and implantation in different species (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rome, Jalabert, Forterre, Singh, Hincks and Salamonsen2013; Machtinger et al., Reference Machtinger, Laurent and Baccarelli2015; Mellisho et al., Reference Mellisho, Velásquez, Nuñez, Cabezas, Cueto, Fader, Castro and Rodríguez-Álvarez2017). Exosomes contain gDNA and have been found in cell culture supernatants, as well as in human and mouse biological fluids including blood, seminal fluid and urine (Kalluri and LeBleu, Reference Kalluri and LeBleu2016). Additionally, human embryos generated by IVF secrete exosomes to the culture medium that are 50–200 nm diameter, express the typical markers of MVs and exosomes, CD63, CD9 and ALIX, and contain OCT4 and NANOG mRNA (Giacomini et al., Reference Giacomini, Vago, Sanchez, Podini, Zarovni, Murdica, Rizzo, Bortolotti, Candiani and Viganò2017).

Limited information has been reported related to EVs and their effects on the developmental capacity of human embryos. No previous study has reported the analysis of gDNA inside EVs as an alternative method for PGT-A. For these reasons, the hypothesis of this research was: ‘The evaluation of EVs from culture medium and its gDNA content reflect the developmental competence of human embryos and can be used as a non-invasive method for PGT-A’. To evaluate this hypothesis, our objective was to ‘correlate the quality and concentration of EVs isolated from culture medium and its gDNA content with the developmental competence of human embryos generated by ICSI’.

Materials and methods

Ethics committee

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Concepción. The ICSI procedures were carried out at the fertility centre Centro de Reproducción Asistida y Especialidades de la Mujer (CRAM), which has had all ethical and sanitary standards approved by the Ministerio de Salud de Chile.

Experimental design

Culture medium was collected from embryos generated by ICSI in a certified fertility clinic and transported to the laboratory. Culture medium samples were identified and classified based on the morphological quality of their respective embryos (POOR, FAIR or TOP quality). In the first experiment, identification and characterization of EVs isolated from culture medium of in vitro produced embryos were carried out using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and flow cytometry analysis. Subsequently, MVs/Exo and ABs were isolated from culture medium and each sample was evaluated individually by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA); the size and concentration of the MVs/Exo and ABs were determined in each sample of culture medium. These results for MVs/Exo were evaluated and related with embryo quality.

Presence of gDNA in the MVs/Exo isolated from culture medium was confirmed by electrophoresis and analysis was performed using Tape Station Analysis software. Finally, aCGH analysis was used to evaluate the presence of gDNA and chromosome abnormalities in MVs/Exo isolated from culture medium. For this, culture media from single embryos were centrifuged and then filtered using a 100 kDa Amicon system. Three assays were performed, two assays in which the culture media of TOP quality embryos were analyzed and the third assay to compare the similarity in chromosome ploidy between arrested embryos and their respective culture medium.

In vitro embryo production and morphological classification

This study was made in collaboration with the fertility centre Centro de Reproducción Asistida y Especialidades de la Mujer (CRAM), in which patients with fertility problems were subjected to ICSI. For this procedure, cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected in phosphate-buffered saline (SAGE In Vitro Fertilization, Inc., a CooperSurgical Company, USA). COCs were denuded with hyaluronidase (LifeGlobal, USA); oocytes at metaphase II (MII) stage were microinjected with spermatozoa and transferred to a dish containing fertilization medium (Global Total for fertilization®, LifeGlobal, USA). Fertilization was assessed 18 h after ICSI by visualization of the two pronuclei (2PN); zygotes with 2PN were cultured individually in 50-μl droplets of Global Total® (LifeGlobal, USA) under mineral oil (LiteOil®, LifeGlobal, USA). Embryos were incubated in an atmosphere of 6% CO2 in air (c. 20% O2), and relative humidity ≥ 90% at 37°C (Labotect Incubator C200, Germany).

At day 3 of culture, embryos were evaluated and selected for embryo transfer or cryopreservation. Embryo classification was based on blastomere number and morphological quality (blastomere size, cytoplasm homogeneity and grade of fragmentation). A two digit number was given to each embryo, the first number corresponded to the blastomere number. and the second number corresponded to the size and fragmentation grade of the blastomeres (1: blastomeres of equal size and without fragmentation; 2a: blastomeres of equal size and with ≤ 20% of cytoplasm fragmentation; 2b: blastomeres of equal size and with ≥20% of cytoplasm fragmentation; 3: blastomeres of different size and without fragmentation; 4: blastomeres of equal or different size with ≥30% fragmentation; and 5: embryos with ≥50% cytoplasm fragmentation). This protocol and classification method has been used for a long time by the fertility CRAM centre with acceptable pregnancy results.

For this research, based in the morphological evaluation done by the fertility centre, the embryos were classified as TOP, FAIR or POOR quality. TOP quality embryos had a blastomere number ≥8, with an equal size among blastomeres and ≤ 20% cytoplasm fragmentation (1–2a). FAIR-quality embryos had six or seven blastomeres, with an equal size among blastomeres and 20–30% cytoplasm fragmentation (1–2b). POOR quality embryos had a blastomere number ≤5, with an equal or different size among blastomeres and with >30% cytoplasm fragmentation (1–5).

Culture medium was collected from the classified embryos. Additionally, embryos that were not able to be transferred or cryopreservation, instead of being discarded, were taken as samples for this research with previous consent from the patients.

Sample collection and storage

Culture media from day 3 embryos generated by ICSI were collected individually into sterile microcentrifuge tubes. Additionally, embryos that were classified as non-viable and had undergone developmental arrest, were collected individually into sterile microcentrifuge tubes. Samples were transported at −20°C from the reproductive centre to the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of the University of Concepción. After arrival in the laboratory, samples were stored at −80°C until NTA or genetic analysis.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis of EVs isolated from culture medium

Individual samples of culture medium (c. 50 µl) were diluted with 550 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min at 4°C to eliminate any possible detritus in the samples. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 2500 g for 20 min at 4°C to separate the EVs into MVs/Exo and ABs. The supernatant that contained the MVs/Exo was collected and separated from the pellet. The pellet that contained the ABs was collected and diluted with 550 µl PBS. Samples of MVs/Exo and ABs from each individual embryo were subjected to NTA using the NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Panalytical, UK). Each individual sample was subjected to NTA at least three times and the mean values were calculated. To ensure accurate results, all culture medium samples were diluted similarly to achieve the same dilution factor. Diameter (nm) and concentration of MVs/Exo and ABs from each sample of culture medium were estimated.

Additionally, EVs from follicular fluid from the patients subjected to oocyte collection were isolated and used as the positive control. For EVs, isolation follicular fluid was processed as described previously (Hung et al., Reference Hung, Hong, Christenson and McGinnis2015). Ultracentrifugation steps were performed as described previously by our research group (Mellisho et al., Reference Mellisho, Velásquez, Nuñez, Cabezas, Cueto, Fader, Castro and Rodríguez-Álvarez2017).

EVs identification by TEM

TEM was used to identify the morphology of the EVs. EVs from culture medium were placed on formvar-carbon-coated copper grids for whole-mount preparations and subjected to TEM analysis, as described previously (Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Stern, Novik, Tran and Stanley2014; Marin and Scott, Reference Marin and Scott2018). Four grids were prepared for TEM analysis of isolated vesicles. The grids were washed and fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 MPBS, and then contrasted in uranyl-oxalate solution (pH 7.0) for 5 min and methyl cellulose-UA on ice for 10 min. Images were processed using ImageJ 1.47t software. Grids were visualized on a Zeiss EM 900 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss, Germany) operated at 80–90 kV.

Evaluation of EVs markers by flow cytometry analysis

In this experiment, EVs from TOP quality and POOR quality embryos were isolated and processed by flow cytometry analysis, as described previously (Mellisho et al., Reference Mellisho, Velásquez, Nuñez, Cabezas, Cueto, Fader, Castro and Rodríguez-Álvarez2017). Markers CD9, CD63, CD81 and CD40L were analyzed in MVs/Exo and ABs isolated from the culture medium of embryos. For this, EVs (35 μL or 4 × 108 particles/ml) were incubated with 4 μm aldehyde/sulfate latex beads (0.125 μl or 1.25 × 105 particles/ml) (Life Technologies, Santiago, Chile) in a final volume of 100 μl of PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, 22 μl of 1 M glycine/PBS (100 mM final concentration) was added to block the unbound sites of the latex beads and was kept for 45 min at room temperature (RT). The EVs/beads complexes were washed twice with 1 ml PBS/0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) by centrifugation at 1500 g for 3 min at RT. After that, EVs/beads complexes were incubated with primary FITC-conjugated anti-human antibodies against CD63 (Abcam, catalogue no. ab18235, clone MEM-259) or CD9 (Abcam, catalogue no. ab34162, clone MM2/57) for 1 h at RT. Next, the EVs were incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-CD81 antibody (Abcam, catalogue no. ab81436, clone M38) or with primary rat monoclonal anti-CD40 antibody (Abcam, catalogue no. ab25044, clone 1C10). Additionally, EVs isolated from ovarian follicular fluid were used as positive controls. Finally, labelled EVs/beads complexes were washed twice with 1 ml PBS/0.5% BSA and 100 μl pellets were resuspended in 400 μl Focusing Fluid (Life Technologies, Inc., USA) and subjected to analysis using an Attune™ NxT flow cytometer (Life Technologies, Inc., USA). A negative control for the antibody reaction was performed using latex beads alone incubated with anti-CD63 or anti-CD9 for 1 h at RT.

Electrophoresis of gDNA from culture medium

For this experiment, fresh culture medium without previous use (Global Total®, LifeGlobal, USA) was used as a negative control, developmentally arrested embryos were used as a positive control and samples from EVs isolated from medium conditioned by individually cultured embryos were analyzed. Each group had three replicates. Prior to electrophoresis, gDNA was extracted and amplified using the PicoPLEX whole-genome amplification (WGA) kit (Rubicon Genomics, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Electrophoresis was performed using a Agilent D1000 Screen Tape System size range 35–1000 bp. For the running ladder, 3 µl D1000 sample buffer was mixed with 1 µl of D1000 ladder. For samples, 3 µl D1000 sample buffer was mixed with 1 µl of DNA sample. Samples were loaded on D1000 Screen Tape using the 2200 Tape Station and controller software. Analysis was performed using Tape Station Analysis software. Additionally, EV samples isolated from medium conditioned by individually cultured embryos were analyzed using an Epoch™ microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek) to confirm the results of the electrophoresis.

WGA and aCGH analysis of embryos and EVs from culture medium

aCGH was selected to analyze chromosome ploidy in embryos and EVs from culture medium. Agilent oligo-based SurePrint G3 8×60K CGH microarrays (Agilent Technologies, USA) were used to allow successful detection of genome-wide copy-number changes of single cells within 24 h, which is more cost-effective compared with fluorescence in situ hybridisation and bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Additionally, the use of the WGA system PicoPlex DNA-seq kit (Rubicon Genomics, Inc.) allowed preimplantation genetic diagnosis by aCGH with similar efficiency compared with NGS (Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Stern, Novik, Tran and Stanley2014)

Two experiments were performed using aCGH analysis. In the first experiment, two aCGH analyses were carried out, for these two assays EVs (MVs/Exo and ABs) from culture medium of TOP quality embryos were analyzed to confirm the presence of gDNA and chromosomal abnormalities. In the second experiment, a third assay was performed in which arrested embryos and their respective culture medium were analyzed to verify the similarity in chromosomal abnormalities between both types of samples.

To achieve these experiments, samples of culture medium were first diluted with 550 µl of PBS and centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min at 4°C to eliminate any possible detritus in the samples. The remaining supernatant containing the EVs was filtered using a 100 kDa Amicon system (0.5 ml, Merck) by centrifugation at 2500 g for 20 min to concentrate EVs in a c. 20 µl volume. These culture medium samples along with collected arrested embryos were subjected to WGA.

Whole-genome amplification was performed using a PicoPLEX WGA kit (Rubicon Genomics, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Samples were placed in a 200 µl-sterile microcentrifuge tube, mixed with 5 µl lysis extraction buffer, followed by 5 µl pre-amplification cocktail and finally with 60 µl amplification cocktail, and incubated in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions in each specific step, respectively. The amplified gDNA was stored at −20°C until the purification procedure.

Amplified gDNA was purified using an illustra™ GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Subsequently, purified gDNA was quantified using an Epoch™ microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek). The labelling step was performed using the Sure Tag Complete gDNA Labelling Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Samples were mixed with random primers and then labelled with Cy3 or Cy5 dyes. For this, one-half of the samples was labelled with the Cy3 master mix (5× buffer, 10× dNTP, Exo-Taq restriction enzyme and Cy3 dye) and the other half with the Cy5 master mix (5× buffer, 10× dNTP, Exo-Taq restriction enzyme and Cy5 dye). The kit also provided female and male human references that were previously amplified, purified, quantified and labelled similarly to the samples. Finally, samples and references were placed in a thermal cycler and incubated in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation, samples and references were purified in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions.

For the hybridization step, the Agilent Hybridization Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA) was used. Cot-1 DNA (Cot-1 Human DNA, 625 µg, Agilent Technologies Catalogue Code 5190-3393) was used to avoid non-specific hybridization. After incubation, samples were placed on a GenetiSure Pre-Screen array 8×60k (G5963-60510) (Agilent Technologies, USA) and then placed on a Hybridization Gasket Slide (Agilent Technologies, USA). The slide was placed in an hybridization oven at 67°C and mixed at 20 rpm for 24 h. Agilent’s CGH Wash Buffer Kit was used; the array was washed with Wash Buffer I for 5 min at RT. A second wash was performed using Wash Buffer II for 1 min at 37°C. Once finished, the slide was scanned using the Agilent SureScan Microarray Scanner Bundle (G4900DA, Agilent Technologies, USA).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, results obtained from NTA were subjected to analysis of variance and least significant difference Fisher’s test was used to compare the means using Infostat statistical software (University of Cordoba, Argentina). Additionally, for aCGH analysis, results were analyzed using CytoGenomics 4.0.3.12 software (Agilent Technologies).

Results

Identification by TEM of EVs isolated from culture medium of embryos generated by ICSI

EVs from follicular fluid were used as a control for identification. Furthermore, culture medium from the embryos was concentrated using 100 kDa Amicon filters to identify EVs from embryos. As was expected, more EVs were found in the follicular fluid compared with embryo culture medium, and indicated that the isolation procedures used for each type of sample had been performed correctly. EVs from follicular fluid were visualized as dark spherical or ovoid structures surrounded by a double lipid layer, with a diameter of 100–200 nm (Fig. 1A–E). Conversely, scarce presence of EVs was observed in culture medium samples due to limited amounts of the samples. EVs from embryo culture medium were characterized as spherical or ovoid structures, with a dark or grey tone and a less defined double lipid layer surrounding them, compared with EVs from follicular fluid. Sizes of EVs from culture medium were 100–200 nm similar that observed in the follicular fluid (Fig. 1F–H).

Figure 1. Identification of extracellular vesicles (EVs) by transmission electron microscopy. (A–E) EVs isolated from human follicular fluid. (F–H) Extracellular vesicles isolated from culture medium of human embryos. EVs are visualized as spherical or ovoid structures, surrounded by a lipid membrane and with a diameter between 50–200 µm.

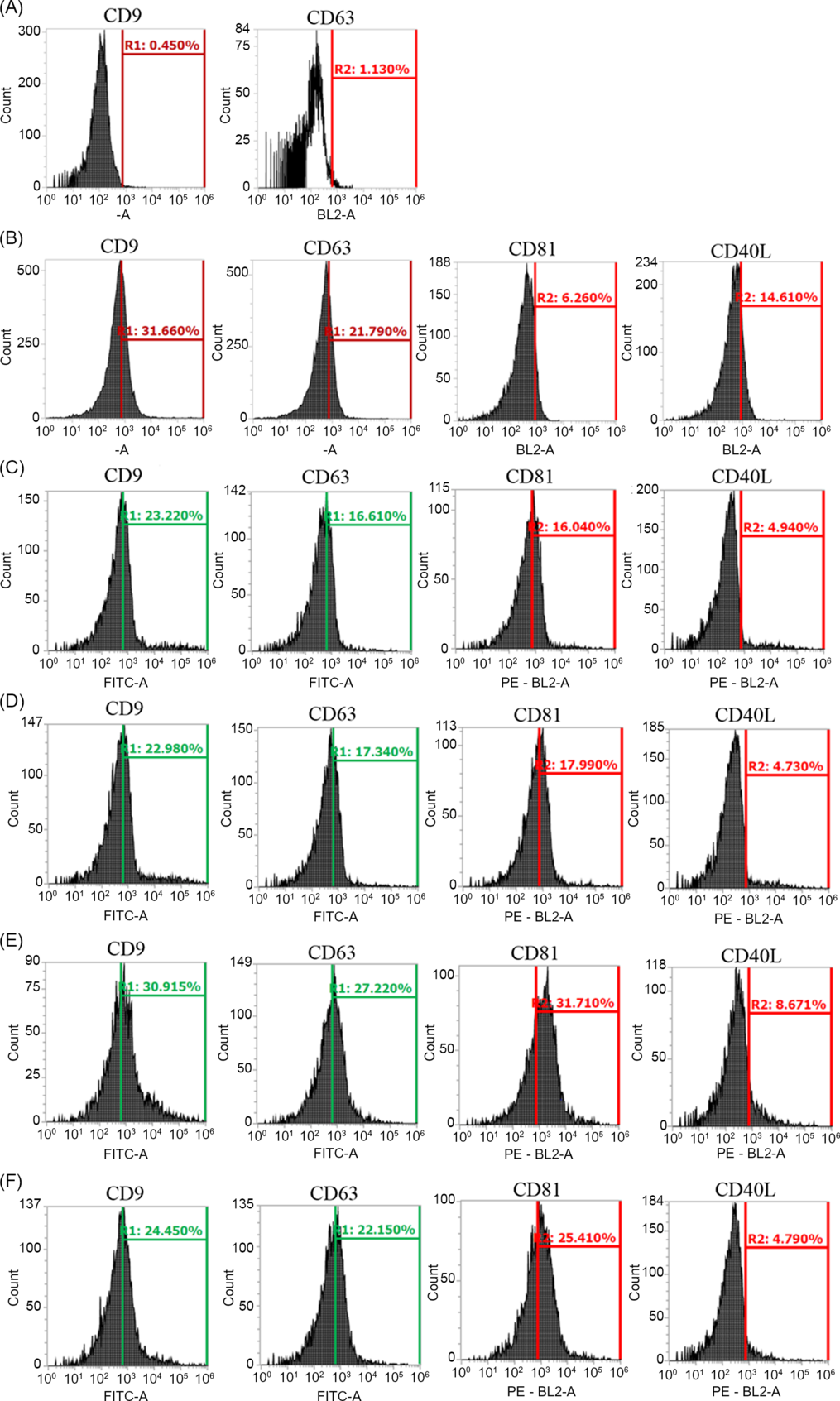

Characterization by flow cytometry analysis of EVs isolated from embryo culture medium

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81 and CD40L) in EVs (MVs/Exo and ABs) isolated from culture medium of TOP quality or POOR quality embryos. Additionally, EVs from follicular fluid were used as a positive control. Furthermore, aldehyde/sulfate latex beads without samples were used as a negative control. The results of the negative control were 0.45% CD9 and 1.13% for CD63 (Fig. 2A). In the follicular fluid used as positive control, the results of surface markers positivity were 31.6% CD9, 6.2% CD81, 21.8% CD63 and 14.6% CD40L (Fig. 2B). For ABs isolated from TOP quality embryos, results were 23.2% CD9, 16.6% CD63, 16.0% CD81 and 4.9% CD40L (Fig. 2C). In ABs isolated from POOR quality embryos, results were 22.9% CD9, 17.3% CD63, 17.9% CD81 and 4.7 CD40L (Fig. 2D). For MVs/Exo isolated from TOP quality embryos, results were 30.9% CD9, 27.2% CD63, 31.7% CD81 and 8.7% CD40L (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, results of MVs/Exo isolated from POOR quality embryos for surface marker positivity were 24.4% CD9, 22.1% CD63, 25.4% CD81 and 4.7% CD40L (Fig. 2F). In summary, surfaces markers were detected at similar rates in follicular fluid and EVs isolated from culture medium of in vitro produced embryos, regardless of embryo quality. These results along with TEM identification demonstrated the presence of EVs in culture medium of human embryos generated in vitro.

Figure 2. Identification of EVs by flow cytometry analysis of exosome surface markers CD9, CD63 and CD81, and the microvesicle surface marker CD40L. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of aldehyde/sulfate latex beads used as negative control. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of follicular fluid used as positive control. Flow cytometry analysis of ABs from culture medium of TOP quality and POOR quality embryos (C) and (D), respectively. Flow cytometry analysis of MVs/Exo from culture medium of TOP quality and POOR quality embryos (E) and (F), respectively.

Isolation of MVs/Exo and ABs from culture medium of embryos generated by ICSI

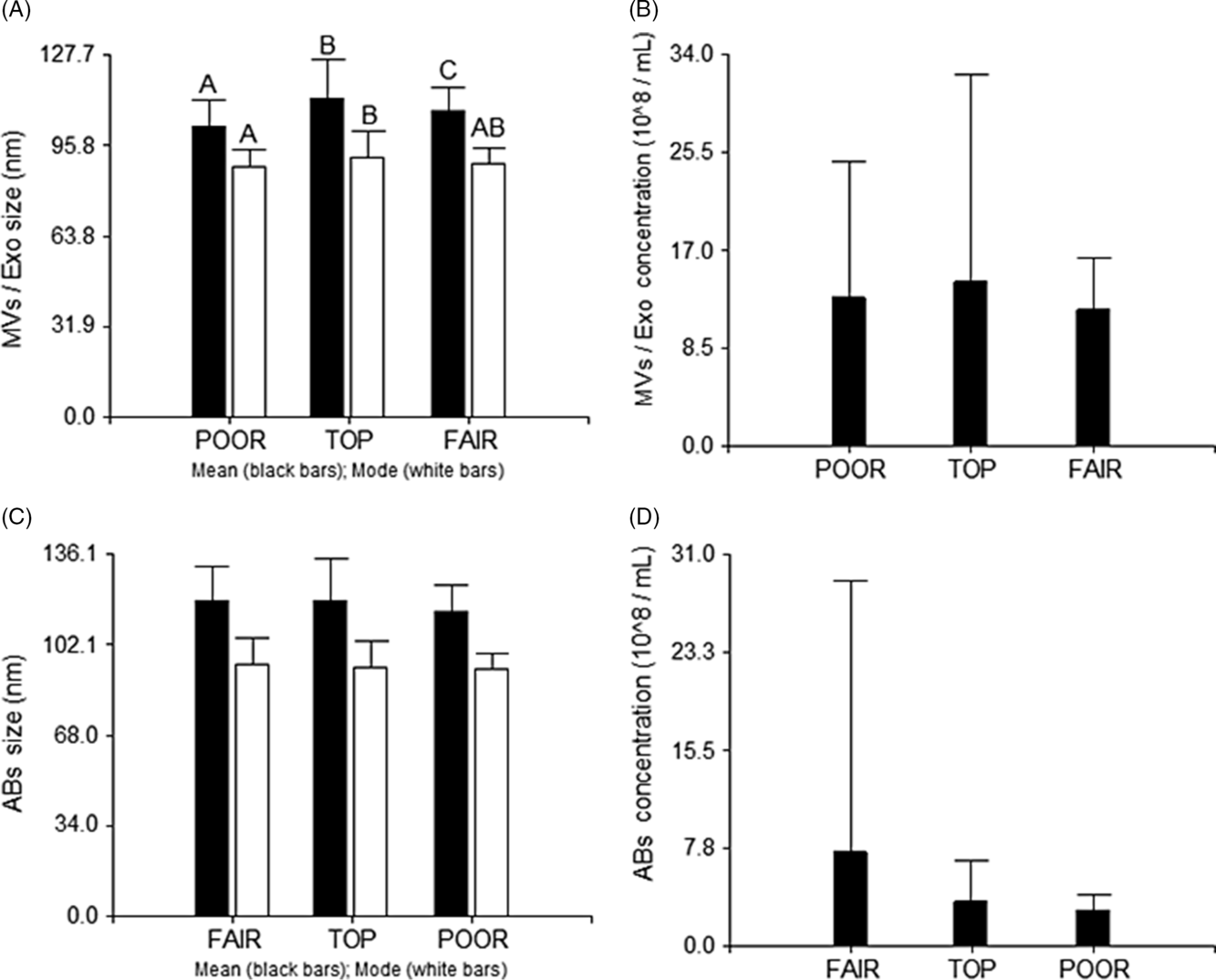

Centrifugation successfully separated MVs/Exo from ABs. NTA revealed that particles isolated as presumptive ABs had a higher diameter and a lower concentration (mean: 118.08 nm, mode: 94.19 nm and 5.34 × 108/ml, respectively) compared with the isolated MVs/Exo (mean: 108.45 nm, mode: 90.12 and 12.98 × 108/ml, respectively) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) of MVs/Exo and ABs isolated from culture medium of human embryo generated by ICSI. (A) Particle size (mean and mode, ± standard deviation (SD)) of MVs and ABs. (B) Concentration of MVs/Exo and ABs × 108 /ml (mean ± SD). (A, B) Different letters within the same graph indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Evaluation of diameter and concentration of MVs/Exo and ABs and their relationship with embryo quality

MVs/Exo isolated from TOP quality embryos had the highest diameter (mean: 112.17 nm, mode: 91.74 nm) compared with embryos classified as FAIR (mean: 108.02 nm, mode: 89.67 nm) or POOR quality (mean: 102.78 nm, mode: 88.17 nm) (P < 0.05). No statistical differences were found in concentration of MVs/Exo between embryos classified as TOP (14.26 × 108/ml), FAIR (11.85 × 108/ml) or POOR quality (12.94 × 108/ml) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. NTA results of EVs isolated from culture medium of human embryos morphologically classified as TOP, FAIR and POOR quality. (A, B) Diameter (mean and mode ± SD) and concentration (mean ± SD) of MVs/Exo isolated from culture medium of TOP, FAIR and POOR quality embryos. (C, D) Diameter (mean and mode ± SD) and initial concentration (mean ± SD) of ABs isolated from culture medium of TOP, FAIR and POOR quality embryos. Different letters in the same graph indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Regarding ABs, no statistical differences were found in the diameter of ABs from embryos classified as TOP (mean: 118.64 nm, mode: 93.91 nm), FAIR (mean: 118.41 nm, mode: 94.68 nm) or POOR quality (mean: 114.54 nm, mode: 93.28 nm) (P > 0.05). No statistical differences were found in AB concentration among TOP (3.26 × 108/ml), FAIR (7.54 × 108/ml) or POOR quality embryos (2.79 × 108/ml) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Detection of gDNA in EVs isolated from culture medium of embryos generated by ICSI

The presence of gDNA in EVs isolated from medium conditioned by individually cultured embryos was evaluated. For this, three samples of EVs isolated from culture medium of human embryos at day 3 of development were analyzed. Fresh commercial culture medium (without use) was used as a negative control. Additionally, developmentally arrested human embryos (at day three of development) that were discarded for embryo transfer were used as a positive control.

Detectable gDNA was present in the negative control samples, average concentration was 2.74 ng/µl. EV samples from culture medium of day-3 embryos contained some detectable gDNA, average concentration was 0.15 ng/µl. Additionally, detectable gDNA was present in the positive control samples, average concentration was 6.56 ng/µl. Detection of gDNA in arrested embryos used as a positive control indicated that extraction and amplification procedures for gDNA were performed correctly. Additionally, five samples of EVs from embryo culture medium were analyzed using a spectrophotometer to verify the presence of gDNA, which was detected in the five samples (Sample 1 = 5.3 ng/µl, Sample 2 = 2.2 ng/µl, Sample 3 = 5.2 ng/µl, Sample 4 = 3.02 ng/µl and Sample 5 = 4.60 ng/µl) which confirmed the results of the electrophoresis.

Detection of gDNA in the negative control might be caused by the presence of human serum albumin in commercial culture medium (Global Total, LifeGlobal, USA), which might contains traces of gDNA. Furthermore, the fact that EV samples from medium of in vitro culture embryos had a reduced concentration of gDNA compared with the negative control samples might be due to the isolation procedure used to separate EVs from the culture medium. This might indicate that gDNA detected in the culture medium of embryos is carried over from EVs secreted by the embryo (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Detection of genomic DNA by electrophoresis. Pictures of the electrophoresis gel and the quantification of gDNA using the Tape Station Analysis. (C1–C3) Culture medium (Global Total®) used as negative control. (M1–M3) EVs isolated from culture medium of human embryos. (E1, E2) Developmental arrested human embryos used as positive control.

Identification of gDNA and chromosomal abnormalities by aCGH in EVs isolated from embryo culture medium

In this experiment, 26 samples of culture medium from TOP quality embryos were analyzed. First, 14 samples of total EVs (MVs/Exo/Abs) isolated from embryo culture medium were analyzed. In the second array, 12 samples of only MVs/Exo from embryo culture medium were analyzed. In the first array, gDNA was detected in all EV samples along with the presence of 23 chromosome pairs (22 autosomes and the X and Y chromosomes) (Fig. 6A, B). In this array, 7/14 (50 %) samples had chromosomal abnormalities (gain or loss) in at least one chromosome pair. Similarly, in the second array, in which only MVs/Exo were analyzed, 23 chromosome pairs were also detected in all samples. In these samples, 8/12 (66.6 %) had at least one type of chromosome abnormality. The highest incidence of abnormality present in the 15 samples with chromosome irregularities was detected in the chromosomes C4: 6/15 (40 %) and C13: 6/15 (40 %) (Table 1).

Figure 6. aCGH results analyzed by Cytogenomics software. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) (MV/Exo and ABs) isolated from culture medium of TOP quality embryos. The results are shown as the comparative analysis against the references Male and Female. The 23 chromosome pairs were detected. (A) EVs isolated from culture medium, without chromosomal abnormalities, the XX chromosomes were detected. (B) EVs from culture medium, an abnormal gain was detected in C19, the XY chromosomes were detected. (C, D) Comparative analysis between arrested embryos and their respective culture medium. The result are showed as the comparative analysis vs. the references Male and Female. Differences in the chromosomal dotation are indicated as blue bar (gain) or pink bar (loss). (C) Arrested embryo (male) with its respective culture medium that indicate chromosomal abnormalities (Medium: C4, C7, C8, C13, C15 and C17; Embryo: C4 and C13). (D) Arrested embryo (female) with its respective culture medium without abnormalities.

Table 1. Rate of chromosome abnormalities detected in EVs from culture medium of TOP quality embryos

* Indicates the chromosome pairs with the highest proportion of abnormalities detection in all the samples.

Comparison by aCGH analysis of arrested embryos with their respective EVs isolated from culture medium

In this experiment, arrested embryos considered non-viable and usually discarded, were used for aCGH analysis, together with total EVs (MVs/Exo/Abs) isolated from their respective culture medium. In total, seven arrested embryos and seven samples of culture medium were analyzed together (Fig. 6C, D). Three of the seven analyzed embryos had a normal chromosome ploidy and this was similar in their respective culture medium samples. Additionally, four embryos had abnormal ploidy similarly to the results obtained in their respective culture medium samples. Despite that, the abnormalities detected in the arrested embryos were not completely similar to abnormalities detected in the EV samples. In general, EV samples isolated from culture medium had an increased number of chromosome abnormalities compared with their respective embryo. The rate of chromosome abnormality detected in the 23 chromosome pairs in the EV samples (24.9%) was significantly higher than the abnormalities detected in their respective embryo samples (8.7 %) (P = 0.03). However, abnormal gains or losses detected in specific chromosome pairs in the arrested embryos were also observed in their respective EVs samples. The rate of similarity in chromosome dotation (normal dotation, gain or loss) detected in arrested embryos and in their respective EVs samples was 70–80% (Table 2).

Table 2. Percentage of similitude in the chromosome endowment between arrested embryos with chromosomal abnormalities and their respective EVs isolated from culture medium

* Indicates the number of chromosome with the same endowment (normal, gains or losses) between the arrested embryos and their respective EVs.

Discussion

EVs, especially exosomes, are detected in a great variety of biological fluids and also in the medium of different types of cell cultures (Kalluri and LeBleu, Reference Kalluri and LeBleu2016). Analysis of EVs has been described previously in human embryos generated in vitro, due to their possible implications for genetic diagnosis (Giacomini et al., Reference Giacomini, Vago, Sanchez, Podini, Zarovni, Murdica, Rizzo, Bortolotti, Candiani and Viganò2017; Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Balakier and Librach2019). In these previous studies, in vitro cultured embryos were found to secrete EVs into the culture medium and the size of these vesicles was either 50–200 nm (Giacomini et al., Reference Giacomini, Vago, Sanchez, Podini, Zarovni, Murdica, Rizzo, Bortolotti, Candiani and Viganò2017) or 30–500 nm (Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Balakier and Librach2019). EVs released by human embryos expressed CD9 and CD63 markers (Giacomini et al., Reference Giacomini, Vago, Sanchez, Podini, Zarovni, Murdica, Rizzo, Bortolotti, Candiani and Viganò2017; Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Balakier and Librach2019). This expression was similar to that described in our research, in which EVs from human embryos were positive for CD9, CD63, CD81 and CD40L expression. Some tetraspanins, such as CD9, CD63 and CD81, are present particularly on exosomes (Kowal et al., Reference Kowal, Arras, Colombo, Jouve, Morath, Primdal-Bengtson, Dingli, Loew, Tkach and Théry2016), which could indicate that, in our research, exosomes could be detected in the culture medium of human embryos. In vitro cultured human embryos are able to release EVs at each stage of development and these EVs are able to cross the zona pellucida (Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Balakier and Librach2019), therefore EVs might play a role in embryo–maternal cross-talk communication. In earlier stages of development, EVs secreted by oviductal cells are taken up by oocytes, sperm and embryos and improve oocyte maturation, fertilization and embryo development (Bridi et al., Reference Bridi, Perecin and Silveira2020; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Oh, Kim and Lee2020; Lopera-Vasquez et al., Reference Lopera-Vasquez, Hamdi, Maillo, Gutierrez-Adan, Bermejo-Alvarez, Ramírez, Yáñez-Mó and Rizos2017; Al-Dossary et al., Reference Al-Dossary, Strehler and Martin-DeLeon2013). Similarly, EVs from embryos could be taken up by oviductal cells due to the EV lipophilic membrane. However, to the best of our knowledge, it has not been reported that EVs secreted from embryos can modify the functionality of oviductal cells. Although the role of EVs secreted from embryos during their early development in the oviduct is still not completely known, it has been proposed that these EVs and their cargo could be a non-invasive source for PGT-A (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Bolumar, Amadoz, Jimenez-Almazán, Valbuena, Vilella and Moreno2020). No previous studies have reported a relationship between the quality of human embryos and the EVs released by them. In our research, TOP quality embryos at day 3 of development released EVs (MVs/Exo) that had a larger diameter compared with the diameter of POOR quality embryos, and demonstrated a relationship between embryo morphological quality and their EVs secretion pattern. This result could be used as a non-invasive indicator of human embryo development in future studies.

In addition, in this research, no significant differences were observed in the EV concentration among TOP, FAIR and POOR quality embryos. EV concentration in human embryos, however, might be related to pregnancy rate (Abu-Halima et al., Reference Abu-Halima, Häusler, Backes, Fehlmann, Staib, Nestel, Nazarenko, Meese and Keller2017; Marin and Scott, Reference Marin and Scott2018). Abu-Halima and colleagues stated that human embryos that achieved pregnancy after embryo transfer had a low concentration of EVs in the culture medium compared with embryos that did not achieve pregnancy (Abu-Halima et al., Reference Abu-Halima, Häusler, Backes, Fehlmann, Staib, Nestel, Nazarenko, Meese and Keller2017). Similarly, Palliger et al. demonstrated by flow cytometry that the culture medium of competent embryos that achieved pregnancy after embryo transfer had a significantly lower concentration of EVs compared with non-competent embryos (Pallinger et al., Reference Pallinger, Bognar, Bodis, Csabai, Farkas, Godony, Varnagy, Buzas and Szekeres-Bartho2017; Marin and Scott, Reference Marin and Scott2018) Related to this, it was reported that activation of p53 in response to induced DNA damage might generate cellular arrest, apoptosis or cellular senescence, which is also associated with an increase in exosome secretion (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Paine, Brooks, McCubrey, Renegar, Wang and Terrian2008).

In other species, such as bovine, the size and concentration of EVs isolated from culture medium of in vitro produced embryos were significantly correlated with embryo competence (Mellisho et al., Reference Mellisho, Velásquez, Nuñez, Cabezas, Cueto, Fader, Castro and Rodríguez-Álvarez2017). In our study, an increase in the diameter of EVs was observed in embryos with the highest developmental competence (TOP quality). However, no differences were observed in EV concentration among embryos of different developmental competence. More studies are needed to validate our results related to EV concentration.

The presence of free gDNA in the culture medium in human embryos generated by IVF procedures has been described widely (Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Fang, Chen, Chen, Xiao, Yang, Wang, Song, Ma, Bo, Shi, Ren, Huang, Cai, Yao, Xie and Shi2016; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lv, Chen, Sun, Wu, Wang, Chen, Chen and Zhang2017). Similarly, the presence of fetal gDNA was detected in the plasma and urine of pregnant women (Al-Yatama et al., Reference Al-Yatama, Mustafa, Ali, Abraham, Khan and Khaja2001). In both findings, free gDNA released from the embryo or fetus was evaluated by a non-invasive method for embryo sexing or chromosomal abnormality detection, with variable results (Al-Yatama et al., Reference Al-Yatama, Mustafa, Ali, Abraham, Khan and Khaja2001; Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lv, Chen, Sun, Wu, Wang, Chen, Chen and Zhang2017). More recently, it was documented that exosomes carried a great variety of molecules, including gDNA, and that these were found in the culture medium of different cell types (Kalluri and LeBleu, Reference Kalluri and LeBleu2016). The lipid membrane of exosomes might confer a strong resistance against the degradation processes to gDNA. For these reasons, gDNA carried by exosomes might be considered as possibly a non-invasive source for PGT-A.

In this research, gDNA was detected in fresh culture medium and in EVs isolated from medium conditioned by individually cultured embryos. gDNA concentration present in fresh culture medium was higher than in the EVs isolated from conditioned medium. Despite that, the results of our study indicated that this could be due to traces of free gDNA present in fresh culture medium instead of gDNA carried inside EVs. Serum albumin is not a EV source, and the presence of EVs has not been detected in culture medium that contains serum albumin (Pavani et al., Reference Pavani, Hendrix, Van Den Broeck, Couck, Szymanska, Lin, De Koster, Van Soom and Leemans2019). However, gDNA has been detected in plasma and serum (Stroun et al., Reference Stroun, Lyautey, Lederrey, Olson-Sand and Anker2001) and that can be carried over or held during the purification or isolation process. Nucleic acid contamination from human serum albumin present in culture medium has been indicated as possible source of foreign gDNA (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Shelling and Cree2016). For these reasons, we speculate that the continuous degradation of free gDNA present in culture medium during in vitro culture might explain why the gDNA concentration is higher in fresh unused medium and lower in medium used for embryo culture. Another possible explanation is that the lower concentration of gDNA in the EVs isolated from medium might be due to the centrifugation steps used for EV isolation and might indicate that free gDNA was eliminated during the isolation process and that only the gDNA present in EVs was quantified.

Finally, aCGH analysis demonstrated that MVs/Exo and the ABs from culture medium (analyzed separately or together) contained gDNA and that 23 chromosome pairs were detected. However, PGT-A results of EVs were not always consistent when compared with their respective embryos. This agrees with results described previously by Stigliani and colleagues who demonstrated that analysis of gDNA present in the culture medium of human embryos had a high grade of discordance compared with biopsies of blastocoel fluid (Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013). This difference was associated with a persistence of maternal DNA in the culture medium of human embryos (Stigliani et al., Reference Stigliani, Anserini, Venturini and Scaruffi2013). It has been postulated that the presence of cumulus cells, and even polar bodies, could contribute to secretion of maternal gDNA into the culture medium (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Shelling and Cree2016) Additionally, aneuploid embryos can undergo a self-correction process, which might be the consequence of multipolar divisions, blastomere exclusion or cellular fragmentation (Daughtry et al., Reference Daughtry, Rosenkrantz, Lazar, Fei, Redmayne, Torkenczy, Adey, Yan, Gao, Park, Nevonen, Carbone and Chavez2019) and this self-correction is related to embryo developmental competence (Barbash-Hazan et al., Reference Barbash-Hazan, Frumkin, Malcov, Yaron, Cohen, Azem, Amit and Ben-Yosef2009). The self-correction process of aneuploid embryos could explain why chromosome abnormalities detected in embryos are lower than chromosome abnormalities detected in the EVs secreted by them.

The mechanisms that explain why embryos release gDNA inside exosomes are not completely understood. Some studies have postulated that exosomes also play a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis (Harding et al., Reference Harding, Heuser and Stahl2013; Raposo and Stoorvogel, Reference Raposo and Stoorvogel2013). Takahashi and colleagues reported that the induced reduction of exosome secretion in senescent cells generated a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent DNA damage response (DDR) (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Okada, Nagao, Kawamata, Hanyu, Yoshimoto, Takasugi, Watanabe, Kanemaki, Obuse and Hara2017). The ROS–DDR originated from accumulation of nuclear DNA in the cytoplasm, which could be detected by STING, a cytoplasmic DNA sensor (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Ma and Barber2009). For these reasons, it was postulated that exosomes play a role in removing harmful chromosomal DNA fragments from cells (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Okada, Nagao, Kawamata, Hanyu, Yoshimoto, Takasugi, Watanabe, Kanemaki, Obuse and Hara2017). The results of our research, along with these previous reports, confirmed the presence of gDNA inside EVs secreted by human embryos produced in vitro. The presence of this gDNA might be related to homeostasis mechanisms and/or mechanisms related to cell–cell communication.

In conclusion, the size of EVs isolated from culture medium of human embryos might be used as a non-invasive method to evaluate their developmental competence. Furthermore, in this research, we detected the presence of 23 chromosome pairs in EVs isolated from culture medium of embryos. gDNA contained in the EVs had a high rate of chromosome abnormality, which was not always in accordance with that observed in the embryos. For this reason, we concluded that at day 3 of development, human embryos secrete EVs carrying gDNA. However, the analysis of gDNA carried by these EVs was not a completely reliable source to predict embryo ploidy, at least at this early time of development.

Acknowledgements

The research group of this investigation want to thank the Centro de Especialidades de la Mujer (CRAM) for its collaboration in this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Financial support

This work was supported by FONDECYT 1170310 from the Ministry of Education of Chile and CORFO 17Cote-72437. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical standards

All procedures used in this research were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethic Committee of the Universidad de Concepción and the fertility clinic Centro de Especialidades de la Mujer (CRAM), which obey the requirements established by the Ministerio de Salud of Chile.