Introduction

The mechanisms by which genomic integrity is maintained and sent through generations during meiosis is a challenging subject for investigation. Histones are subjected to several post-translational modifications, which occur predominantly in the tail region. These modifications include acetylation, ubiquitylation and methylation of lysines and arginines, phosphorylation of serines, threonines and tyrosines, glycosylation, biotinylation, ADP-ribosylation, and carbonylation of several different residues (Jenuwein and Allis, Reference Jenuwein and Allis2001). Histone modification is a major factor that changes chromatin structure, thereby influencing gene expression (Greer and Shi, Reference Greer and Shi2012).

Organisms require an appropriate equilibrium of stability and dynamics in their gene expression profile, to maintain cell identity and to differentiate. In this context, epigenetic regulation is essential for this dynamic control. Post-translational methylation of histones is an important type of chromatin modification that influences biological processes during early development and differentiation (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Teyssier and Strahl2005).

Histone methylation is more complex than any other histone covalent modification. The consequence of methylation can be positive or negative towards transcriptional expression, depending on the position of the methylated residue within the histone tail (Jenuwein and Allis, Reference Jenuwein and Allis2001). Lysine residues can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated, and arginine residues can exist in a mono- or dimethylation state (Martin and Zhang, Reference Martin and Zhang2005). There are at least 24 identified sites of arginine and lysine methylation on core nucleosomal histones (Kouzarides, Reference Kouzarides2007). Such combinatory potential of methylated nucleosomal core histones is necessary to allow regulation of dynamic processes that require sequential timed events (Martin and Zhang, Reference Martin and Zhang2005).

Enormous progress has been made to identify post-translational histone modifications. Moreover, specific enzymes that ‘write’, ‘erase’ and ‘read’ these histone markers have been identified and characterized.

Different degrees of lysine methylation (mono-, di-, trimethylation) are associated with different biological functions. The enzymes responsible for these modifications are histone lysine (K) methyltransferases (KMTs) that contain the catalytically active SET (Suppressor of variegation, Enhancer of Zeste, Trithorax) domain, with one exception (Dot1, renamed KMT4, is known as disrupter of telomeric silencing 1). All these SET proteins use S-adenosyl methionine as a co-substrate to catalyze the transfer of one or more methyl groups to the amino groups of lysine (van Leeuwen et al., Reference van Leeuwen, Gafken and Gottschling2002).

Before 2004, it was not clear if K-methylation was reversible, as in K-acetylation. The finding and characterization of the first histone lysine (K) demethylase (KDM) – an H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) demethylase, LSD1, that is able to demethylate mono- and dimethylated histone lysine residues– determined the identification of a major class of enzymes and led to deciphering the important epigenetic mechanisms involved in development and differentiation (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Lan, Matson, Mulligan, Whetstine, Cole, Casero and Shi2004). At this time, a plethora of histone demethylases and methyltransferases has been discovered that mediates complex biological processes. Depending on the biological context, some methylation events are stably maintained (silenced heterochromatin state), whereas others are dynamic (cytodifferentiation or response to environmental stimuli). It is a certainty for now, that the diverse patterns of methylation events provide exceptional regulatory power (Greer and Shi, Reference Greer and Shi2012). Methylated histones are recognized by chromatin effectors (readers) that recruit other molecules to alter chromatin structure and function (Taverna et al., Reference Taverna, Li, Ruthenburg, Allis and Patel2007).

Methylation of H3K4 is associated with open chromatin and specifically with genes that are potentially active. H3K4 methylation can lead to the recruitment of specific factors such as the CHD1 protein, shown to be bound to H3K4me2 and H3K4me3, and the NURF complex, involved in nucleosomes dynamics at active genes (Sims et al., Reference Sims, Chen, Santos-Rosa, Kouzarides, Patel and Reinberg2006, Štiavnická et al., Reference Štiavnická, García-Álvarez, Ulčová-Gallová, Sutovsky, Abril-Parreño, Dolejšová and Nevoral2020). Other proteins recruited by H3K4 methylation include ISWI ATPase, which binds via other proteins (Li et al., Reference Li, Ilin, Wang, Duncan, Wysocka, Allis and Patel2006).

Methylation of H3K4 interacts with other modifications. For example, H3R2me2 is prevented by H3K4me3 and, conversely, H3R2me2 prevents H3K4 methylation in mammals (Guccione et al., Reference Guccione, Bassi, Casadio, Martinato, Cesaroni, Schuchlautz, Lüscher and Amati2007, Kirmizis et al., Reference Kirmizis, Santos-Rosa, Penkett, Singer, Vermeulen, Mann, Bähler, Green and Kouzarides2007). Methylation of H3K9 by SUV39H KMT is prevented if H3K4 is methylated and H3S10 is phosphorylated. This process could be a way to exclude repressive H3K9 methylation on actively transcribed genes (Rea et al., Reference Rea, Eisenhaber, O’Carroll, Strahl, Sun, Schmid, Opravil, Mechthel, Ponting, Allis and Jenuwein2000). Monoubiquitylation of H2BK123 affects levels of H3K4me3. One suggestion is that the Set1 complex tri-methylates H3K4 only if the nucleosomes are in a certain conformational state, defined by ubiquitylation of H2B (Zhang and Reinberg, Reference Zhang and Reinberg2001, Burlibaşa et al., Reference Burlibaşa, Zarnescu, Cucu and Gavrilă2008). AOF2 (synonym KDM1a) is a specific lysine demethylase involved in the removal of mono- and di-methylation of H3K4 (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wynder, Bochar, Hakimi, Cooch and Shickhattar2006) and acts synergistically with histone deacetylases (HDAC 1/2), REST corepressor 1 (RCOR1) and PHD protein 21A (PHF21A) to repress transcription (Godmann et al., Reference Godmann, Auger, Ferraroni-Aguiar, Di Sauro, Sette, Behr and Kimmins2007).

Epigenetic events in the testis regarding H3K4 methylation have just begun to be studied. The interplay between different kinds of epigenetic modifications remains poorly understood. Little information regarding the link between DNA methylation and histone methylation is mentioned in the literature. DNA methylation seems to have a role in directing H3K9 methylation (Bartke et al., Reference Bartke, Vermeulen, Xhemalce, Robson, Mann and Kouzarides2010). It has also been demonstrated that histone methylation can interfere with DNA methylation, these two markers reinforce each other to establish a stable repressive chromatin state (Greer and Shi, Reference Greer and Shi2012).

In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the consequences of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5aza2DC, decitabine) treatment for H3K4me3 distribution at different stages of germ cell differentiation in murine spermatogenesis. 5aza2DC is a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor, used as an anticancer agent for treatment of different types of cancer (Gabbara and Bhagwat, Reference Gabbara and Bhagwat1995).

Materials and methods

Animals

Mus musculus BALB/c was chosen as the mammalian model organism. Male adult mice were kept in constant environmental conditions (12 h:12 h, light:dark cycles, 22 ± 3°C temperature, 30% humidity), fed with standard granules and had access to drinking water ad libitum.

To collect biological samples, the animals were sacrificed in compliance with the European Council (86/609/CEE/24.11.2004) recommendations regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and scientific purposes.

5aza2DC treatment

Here, 12 male mice were divided into two groups; 10 individuals were injected with 5aza-2DC and two individuals were injected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and used as control animals.

Treated male adults were injected intraperitoneally two times a week for 6 weeks with 0.1 mg/kg body weight 5aza2DC, to expose male germ cells throughout their development.

Immunocytochemistry

H3K4me3 labelling was performed using rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam Cat# ab8580, RRID:AB_306649) as the primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (Abcam Cat# ab150077, RRID:AB_263035) as the secondary antibody. Testes and epididymis were fragmented and washed in 0.05 M potassium chloride solution. Hypotonia was achieved using the same solution for 40 min. and then samples were centrifugated for 10 min at 1000 rpm. Pellets were resuspended and dropped onto slides previously covered with poly-l-lysine, and then washed with PBS for 15 min, and treated with PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature (RT) to allow permeabilization. Slides were rinsed three times (5 min per wash) with PBS, and incubated in 1% BSA in PBS/0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) with 0.3M glycine for 30 min to block non-specific binding of antibodies. In the next step, cells were incubated with primary antibody anti-H3K4me3 (1:200 dilution) in 1% BSA in PBS from stock solution, 1 mg/ml, overnight at 4°C. The solution was decanted away and then slides were washed three times in PBS, 5 min per wash. Cells were incubated with the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 diluted 1:500 in 1% BSA in PBS) for 1 h in the dark at RT. After washing three times in PBS, cells were counterstained and mounted in Fluoroshield mounting medium containing DAPI (Abcam, Cat# ab104139). Experiments were performed using the same comparative study for the negative control (slides without primary antibody). Digital images were obtained using an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope and processed using QuickPhoto Micro 2.3 software.

Quantification of immunostaining and statistical analysis

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) can be used to assess changes in specific testicular population following treatment with chemicals or hormones. To accomplish this, stains were quantified using the threshold tool in ImageJ software program v.1.2.4 (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; RRID:SCR_003070). All images were captured using the same microscope settings, so that the same threshold settings were used. Using ImageJ software, the staining intensity for each cell stage (control/5-aza-2DC treatment) was computed. The histograms of the stains were plotted in the range 0–255, where zero represents maximum intensity and 255 indicated no stain. Here, 10 mean values (± standard deviation (SD)) were recorded for each cell stage and the mean staining intensities were calculated. One-way analysis of variance was carried out to determine statistical significance between the mean values of different sperm cells stages. A 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05) was used to determine statistical significance. An unpaired t-test (GraphPad Prism v.8.4.3 software; RRID:SCR_002798) was carried out to determine statistical significance between the mean values of the control and tested groups. All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences were considered significant at P-values < 0.05.

Results

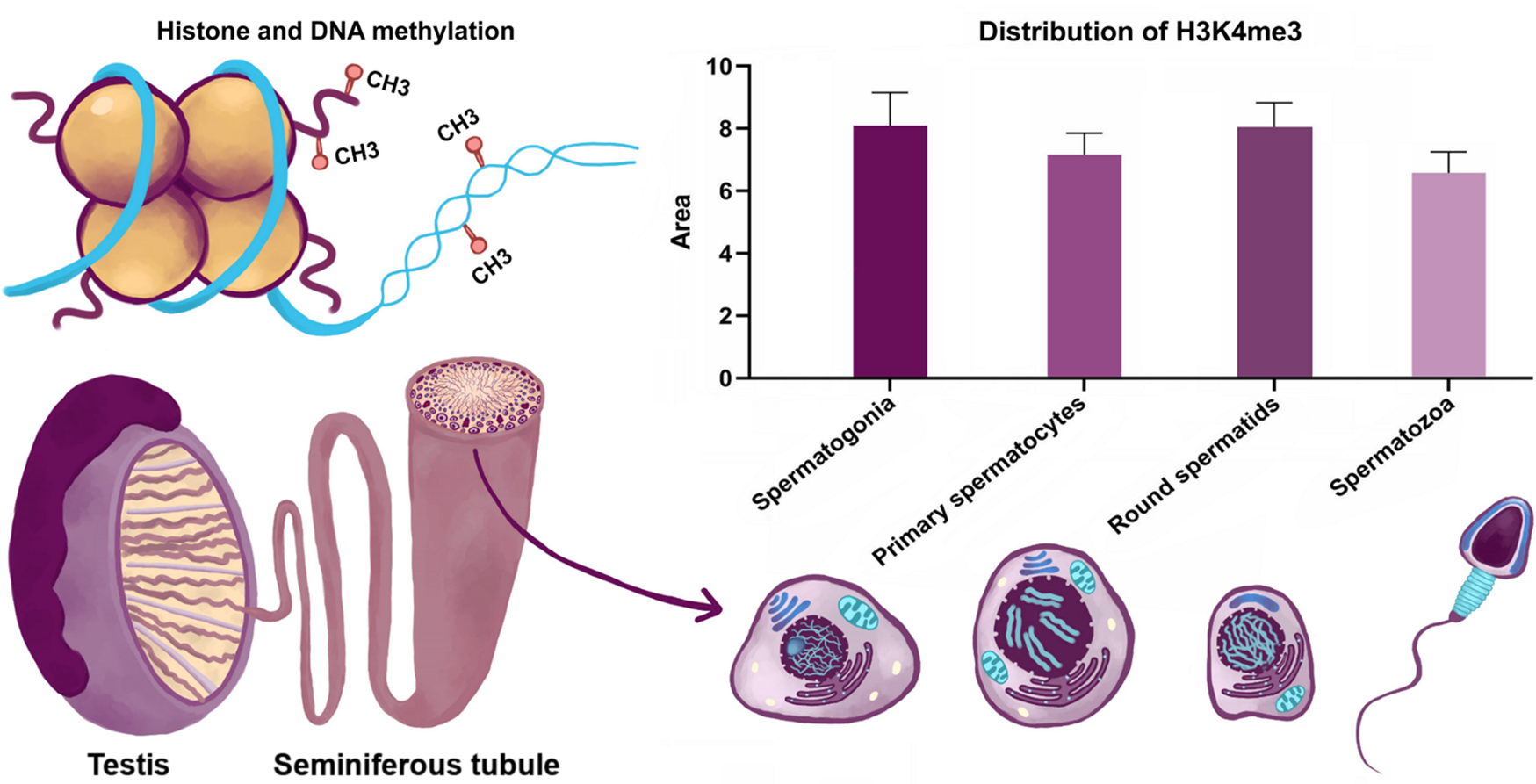

To assess the localization pattern of histone H3K4me3 in mouse spermatogenesis, we conducted immunocytochemistry analysis using an anti-H3K4me3 antibody.

The primary antibody used in this experiment recognized the K4 trimethylated isoform of histone H3. Specificity of primary antibody has been tested previously (Mizukami et al., Reference Mizukami, Kim, Tabara, Lu, Kwon, Nakashima and Fukamizu2019). Immunostaining with the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488) for H3K4me3 in mouse spermatogenic cells produced a nuclear pattern that was dependent on the cell type and stage of the reproductive cycle. ICC analysis using anti-H3K4me3 revealed a selective localization of this epigenetic marker (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Immunofluorescence detection of H3K4me3 in control mouse testes. As a negative control for ICC, cells were reacted only with secondary antibody (without anti-H3K4me3) (×100 magnification).

The staining pattern for H3K4me3 was dynamic (Fig. 2). The signal was weak in spermatozoa, while the staining was strong in spermatogonia and spermatids, and moderate in primary spermatocytes.

Figure 2. Dynamics of H3K4me3 in spermatogenesis.

Global H3K4me3 has been highlighted in primary spermatocytes and in round spermatids (Fig. 2). In other differentiation stages, the presence of this modification is more subtle, being located in certain regions such as the nucleolar region of the spermatogonia nuclei or at an inner surface nuclear membrane localization in round spermatids (Fig. 1). These chromatin domains could have critical roles in the establishment of global chromatin environments and orchestration of DNA-based biological tasks.

Spermatogonia undergo self-renewal to ensure constant spermatozoa production (Roosen-Runge, Reference Roosen-Runge1962). During this process, specific genes have been identified with particular expression patterns that are influenced by histone modifications (Song et al., Reference Song, Liu, An, Nishino, Hishikawa and Koji2011). In this context, the level of H3K4me3 in spermatogonia could be correlated with a particular gene expression profile. Spermatocytes undergo a long prophase of meiosis. During differentiation, chromatin becomes continuously condensed, the homologous chromosomes exchange DNA segments through homologous recombination. In this stage, most genes are silenced. Our results showed a moderate signal in primary spermatocytes, with dynamics in different stages of prophase. The signal for H3K4me3 is significantly reduced in leptotene and pachytene stages, indicating that genes may be generally transcriptionally inactivated. Staining intensity increased from the diplotene spermatocyte stage. In spermiogenesis, spermatids undergo extreme condensation of chromatin into the sperm head, in which most histones are replaced by protamines. Knowledge on the mechanisms controlling replacement of histones by protamines is still limited. Our results highlighted a strong signal in round spermatids and a lower intensity of signal in spermatozoa. H3K4me3 could facilitate histone–protamine exchange, this epigenetic marker is usually related to relaxation of chromatin structure in round spermatids.

To understand the dynamic regulation of, and by, histone methylation, it is useful to take a holistic view of regulation of, and by, this chromatin modification. To gain an insight into the mechanisms controlling histone methylation and the interplay between histone methylation and DNA methylation we investigated the in vivo effect of 5aza2DC on murine spermatogenesis.

ICC analysis with H3K4me3 in the 5aza2DC-treated group of mice revealed the presence of the signal at the following stages of male germ cells differentiation: (1) in the spermatogonia the H3K4me3 was localized in the nucleolus region; (2) in primary spermatocytes the signal had a particular localization concentrated both in certain chromatin domains and in a significant amount in the cytoplasm; and (3) in round spermatids the signal decreased. Surprisingly, in mature spermatozoa, the H3K4me3 signal was detected in higher intensity compared with in round spermatids (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Immunofluorescence detection of H3K4me3 in the 5-aza-2DC-treated mouse group. As a negative control for ICC, cells were reacted only with secondary antibody (without anti-H3K4me3) (×100 magnification).

Mean pixel values were calculated from each histogram. Results showed a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the mean reactivities of H3K4me3 in primary spermatocytes from the treated group. For round spermatids and spermatozoa, a statistically significant decrease (P < 0.05) following 5aza2DC was noticed. No statistically significant differences were observed in spermatogonia mean signals between the control and 5aza2DC treatments (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effect of 5aza2DC treatment staining intensity for each cell stages (control/5-aza-2DC treatment). Unpaired t-tests were caried out to determine statistical significance between the mean values of the control and tested groups. Error bars represent ± SD.

Concomitant with the inhibition of DNA methyltransferases, there is extensive apoptosis of different cell types, especially of primary spermatocytes, that leads to infertility. Regarding this hypothesis, two studies conducted by Burlibaşa and colleagues (Burlibaşa and Zarnescu, Reference Burlibaşa and Zarnescu2013; Burlibaşa et al., Reference Burlibaşa, Ionescu and Dragusanu2019), demonstrate that apoptosis induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors could be accelerated by inhibiting DNA methyltransferase.

Discussion

The results of this study allowed us to propose a critical role for chromatin modifying enzymes in the control of chromatin architecture and composition during sperm differentiation. Our studies highlighted a crosstalk between epigenetic markers to achieve a higher-order structure in mature sperm with implication for zygotic chromatin function. Clearly, abnormal DNA methylation is in fact associated with altered histone modifications. In conclusion, we have shown a unique pattern of methylation of histone H3 in male germ cells. These results may contribute to the understanding of sperm-specific epigenetic regulation, which would therefore be an important source for the investigation of chromatin reorganization, nucleosome assembly machinery, pluripotency and differentiation.

A highly dynamic remodelling state could make sperm cells susceptible to environmental factors, causing infertility, and the altered epigenetic markers could be inherited and further result in phenotypic defects in the offspring. For this reason, it is imperative to study the dynamics of chromatin structure and composition during sperm differentiation to develop new methods of diagnosis and treatment, especially in the context of assisted reproductive technologies. An important challenge for epigenetics in the future will be to understand the interaction between various epigenetic modifications, to achieve a sperm-specific epigenetic code with important consequences for fertility and offspring health.

Acknowledgements

This research acknowledges the effort of all authors in planning the experimental design and interpreting the results. The authors are also grateful to student D. Apetrei for technical support.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, LB and CD; methodology, LB and A-TN; statistical analysis LB and CD; writing, original draft preparation, LB; writing, review and editing, LB, A-TN and CD; supervision, LB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

Animals used in these experiments were BALB/c mice. To collect biological samples, the animals were sacrificed in compliance with the European Council (86/609/CEE/24.11.2004) recommendations regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and scientific purposes. The animal study was approved by the University of Bucharest Animal Care and Use Committee. Our animal facility laboratory is a Good Laboratory Practice manipulation implemented in accordance with national (ANM) and international (EMEA) rules.