Introduction

The re-acquisition of totipotency in somatic cells was experimentally demonstrated by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) more than half a century ago (Gurdon and Melton, Reference Gurdon and Melton2008; Moura, Reference Moura2012; Matoba and Zhang, Reference Matoba and Zhang2018). Subsequent decades of intensive research have led animal cloning by SCNT to several applications in both scientific and commercial settings (Melo et al., Reference Melo, Canavessi, Franco and Rumpf2007; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Smith, Tian, Lewin, Renard and Wakayama2007; Keefer, Reference Keefer2015; Matoba and Zhang, Reference Matoba and Zhang2018).

Despite the potential of animal cloning by SCNT, the procedure is still of low efficiency and labour intensive (Solter, Reference Solter2000; Kishigami et al., Reference Kishigami, Wakayama, Van Thuan, Ohta, Mizutani, Hikichi, Hong-Thuy Bui Balbach, Ogura, Boiani and Wakayama2006; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Smith, Tian, Lewin, Renard and Wakayama2007; Keefer, Reference Keefer2015). The SCNT technique remains essentially performed as first described (Briggs and King, Reference Briggs and King1952; Gurdon, Reference Gurdon2006; Ogura, Reference Ogura2017), in which somatic cell genomes are inserted by cell fusion or injection into enucleated eggs by micromanipulation (Briggs and King, Reference Briggs and King1952; Solter, Reference Solter2000; Kishigami et al., Reference Kishigami, Wakayama, Van Thuan, Ohta, Mizutani, Hikichi, Hong-Thuy Bui Balbach, Ogura, Boiani and Wakayama2006; Vajta, Reference Vajta2007; Kyogoku et al., Reference Kyogoku, Yoshida and Kitajima2018; Matoba and Zhang, Reference Matoba and Zhang2018).

Numerous alternative enucleation approaches have been described and progressively improved to simplify this labour-intensive procedure (Fulka et al., Reference Fulka, Loi, Fulka, Ptak and Nagai2004; Li et al., Reference Li, White and Bunch2004; Iuso et al., 2013; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Hajian, Forouzanfar, Ostadhosseini, Moulavi, Ghanaei, Gourbai, Shahverdi, Vosough and Nasr-Esfahani2015; Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Oliveira, Leal, de Lima, Del Collado, Vantini, Monteiro, Niciura and Garcia2015). Two main strategies have been pursued to attain micromanipulation-free functional oocyte enucleation. First, methods that forces all oocyte chromosomes to be expelled in a polar body (PB) (Fulka et al., Reference Fulka, Loi, Fulka, Ptak and Nagai2004). Second, functional approaches that destroy or inactivate the oocyte genome, therefore eliminating the need for its physical removal (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hwang, Shin, Park, Han and Lim2004; Moura et al., Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008, Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019; Kuetemeyer et al., Reference Kuetemeyer, Lucas-Hahn, Petersen, Lemme, Hassel, Niemann and Heisterkamp2010). However, none of these alternate enucleation approaches yields satisfying enucleation efficiencies. Strategies to eliminate chromosomes in the PB have met with generally low enucleation efficiencies, subject to the protocol or interspecies variability, and susceptibility to enucleation reversibility (Elsheikh et al., Reference Elsheikh, Takahashi, Hishinuma and Kanagawa1997; Savard et al., Reference Savard, Novak, Saint-Cyr, Moreau, Pothier and Sirard2004; Costa-Borges et al., Reference Costa-Borges, Paramio, Calderón, Santaló and Ibáñez2009).

Some alternate enucleation approaches are efficient to inactivate or destroy the oocyte genome, but embryonic development was diminished or poorly characterized (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hwang, Shin, Park, Han and Lim2004). By contrast, radiation is useful for enucleation of amphibian or fish oocytes destined for SCNT (Wakamatsu et al., Reference Wakamatsu, Ju, Pristyaznhyuk, Niwa, Ladygina, Kinoshita, Araki and Ozato2001; Gurdon, Reference Gurdon2006), due to their unique tolerance to DNA damage and polyploidy during early development (Finkielstein et al., Reference Finkielstein, Lewellyn and Maller2001; Wakamatsu et al., Reference Wakamatsu, Ju, Pristyaznhyuk, Niwa, Ladygina, Kinoshita, Araki and Ozato2001). Therefore, it is still imperative to physically remove the oocyte meiotic spindle during mammalian SCNT (Ogura, Reference Ogura2017; Kyogoku et al., Reference Kyogoku, Yoshida and Kitajima2018).

Progress on understanding the underlying mechanisms of chemical oocyte enucleation approaches should aid their improvement (Lan et al., Reference Lan, Wu, Han, Ge, Liu, Wang, Wang and Tan2008; Li et al., Reference Li, Kang, Jin, Hong, Zhu, Jin, Gao, Yan, Cui, Li and Yin2014; Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Oliveira, Leal, de Lima, Del Collado, Vantini, Monteiro, Niciura and Garcia2015). Recently, Moura et al. (Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019) identified conditions to rescue most cellular roadblocks (i.e. diminished oocyte maturation and early embryonic development arrest) during functional oocyte enucleation by actinomycin D (AD) for bovine SCNT. However, cloned blastocyst development after AD functional enucleation remained lower than the conventional SCNT protocol (Moura et al., Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019). One strategy to further improve functional oocyte enucleation would be to replace AD with other DNA damaging molecules that may circumvent developmental arrest.

Mitomycin C (MMC) is a well characterized molecule that inhibits DNA replication irreversibly (Tomasz and Palom, Reference Tomasz and Palom1997), but its potential for chemical oocyte enucleation remained unexplored. As MMC does not inhibit gene transcription as do other DNA damaging agents such as AD (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Rabinowitz and Reich1962), it may activate fewer DNA repair mechanisms that trigger an early embryonic arrest. Therefore this study aimed to test MMC as a chemical to functionally enucleate oocytes for bovine SCNT.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated.

Oocyte in vitro maturation

Oocyte in vitro maturation (IVM) was performed as described by Moura et al. (Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008). In brief, bovine ovaries obtained at slaughterhouses (Distrito Federal, Brazil) and 2–8 mm follicles were aspirated using an 18-gauge needle with a vacuum system. Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) with at least three cumulus layers and a homogeneous cytoplasm were selected. The IVM medium was TCM-199 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, CA, USA), 0.01 IU ml−1 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), 24 IU ml−1 luteinizing hormone (LH), and antibiotics (i.e. penicillin and streptomycin) at 39°C with 5% CO2 in air for 17–24 h, as described below.

Mitomycin C (MMC) treatment

After 17 h of IVM, COCs were washed in fresh IVM medium and denuded using 0.2% hyaluronidase with gentle pipetting. Denuded oocytes were incubated in 10 μg ml−1 MMC for varying incubation periods (0.5, 1.0, 1.5 or 2.0 h), washed five times in IVM medium, and placed in IVM medium until completion of 24 h of IVM. Non-treated control oocytes [P(CTL)] were subject to a vehicle-containing medium. The nuclear maturation efficiency was determined by the number of eggs with a PB at 24 h of IVM.

Somatic cell culture and cell-cycle synchronization

Bovine primary fibroblasts from an adult cow were used in the experiment. Early passage fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented (Gibco) with 10% FBS, and antibiotics. Furthermore, cells were passaged once a week and kept under confluence for at least 48 h for cell-cycle synchronization before being used for SCNT.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT)

The SCNT was carried out as previously described (Moura et al., Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008, Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019), with minor modifications. Briefly, COCs denuded at 17 h of IVM and eggs with homogeneous cytoplasm and a visible PB were selected randomly for SCNT or parthenogenetic development. Eggs for MMC enucleation remained incubating in 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h.

Eggs were used for SCNT after incubation in 0.33 μg ml−1 cytochalasin D and 7.5 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342 for 20–30 min. Micromanipulation was carried out with a Nikon TDM inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan) and Narishige 188 micromanipulators (Narishige, Japan) at room temperature.

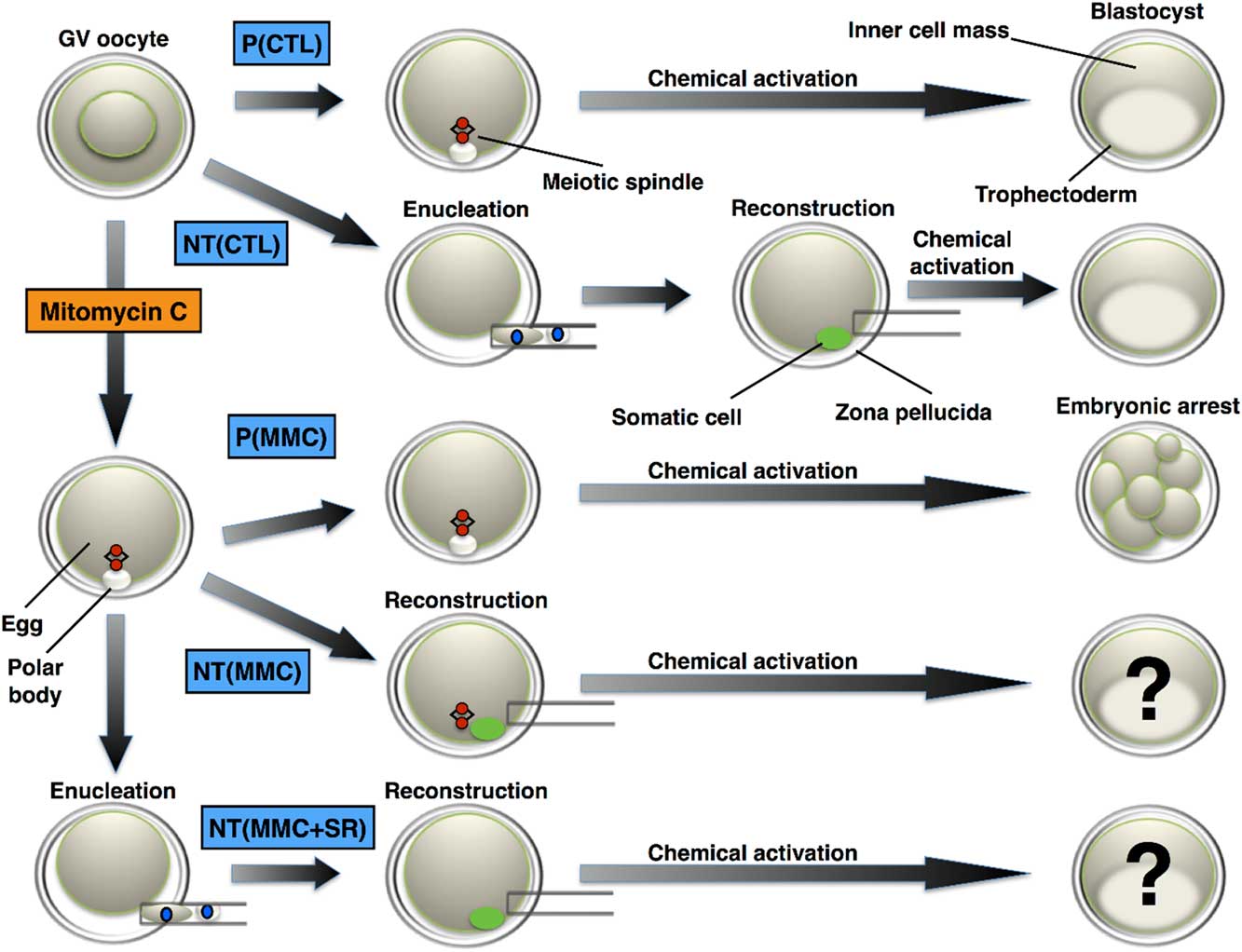

Oocyte enucleation was carried out using three approaches according to the experimental design (Fig. 1). For control nuclear transfer [NT(CTL)], eggs oriented to the position analogous to five or four o’clock on a clock face had the PB with approximately 5% of the adjacent cytoplasm removed with a bevelled injection pipette. The exposure of the cytoplasm biopsy to ultraviolet (UV) light confirmed the meiotic spindle removal. The PB was removed solely for SCNT using MMC enucleation [NT(MMC)], and the injection pipette was also exposed to UV light to rule out any accidental removal of the meiotic spindle removal. The NT(MMC+SR) group was carried out by MMC treatment (10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h) followed by removal of the PB and 5% of the adjacent cytoplasm (spindle removal) at least 1 h after resuming MMC incubation.

Figure 1 Functional oocyte chemical enucleation by mitomycin C. Inactivation of the egg chromosomes is demonstrated by inhibition of parthenogenetic development. Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) into MMC-enucleated eggs rescues embryonic development by introduction of a DNA replication-competent nucleus. Physical removal of the meiotic spindle (conventional enucleation) after MMC treatment (MMC enucleation) addresses the specificity of MMC effect on egg chromosomes. GV: germinal vesicle; MMC: mitomycin C; P(CTL): control parthenogenetic development; P(MMC): MMC-treated oocytes show abolished parthenogenetic development – control of MMC enucleation. NT(CTL): control nuclear transfer using egg enucleation by micromanipulation and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC): denuded eggs treated with MMC and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC + SR): denuded eggs treated with MMC, followed by meiotic spindle removal after MMC incubation and reconstructed with a somatic cell.

Egg reconstruction was carried out with a somatic cell through the same slit made during enucleation. Egg-somatic cell couplets were immediately fused by applying two 30 μs pulses of 2.1 kVA cm−1 with an electrocell manipulator (BTX 200, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described (Moura et al., Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008). Fusion evaluation was after 30 min. Non-fused couplets were subjected to a second fusion. Fused units were cultured before chemical activation, as described below.

Chemical activation and embryo culture

Procedures were carried out as previously described by Moura et al. (Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008, Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019). Fused couplets were subject to chemical activation using 5 μM ionomycin for 5 min and 2 mM 6-dimethylaminopurine (6-DMAP) in the SOFaaci medium for 4–5 h. The activated couplets were washed extensively and cultured in SOFaaci medium supplemented with 0.34 mM trisodium citrate, 2.77 mM myo-inositol, and 5% FBS at 39°C with 5% CO2 in air. Embryos were co-cultured on a cumulus monolayer, and embryonic development recorded at 48, 168 and 192 h post-activation.

Embryo transfer (ET)

The ET procedure and pregnancy diagnosis were carried out at the Geneal Genética e Biotecnologia Animal (Uberaba, Brazil), under current legal and ethical legislation. One or two blastocysts were transported in TQC Holding Plus medium (AB Technology, Pullman, WA, USA) at 39°C until non-surgical transfer to synchronous recipient heifers. After embryo implantation, pregnancies were monitored by ultrasound scanning within 30-day intervals for assessment of fetal viability.

Statistical analysis

Binomial data (maturation, cleavage, blastocyst, and pregnancy rates) analyzed by chi-squared test using absolute frequencies. Differences with a probability of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhibition of bovine parthenogenetic development using mitomycin C

The incubation of denuded oocytes in 10 μg ml−1 MMC did not affect maturation rates (Table 1), except the 1.0 h MMC treatment. Eggs were subject to chemical activation after incubation with MMC (Table 1). The effect on cleavage rates was proportional to the duration of incubation with MMC (53.84–66.35%), in comparison with their non-treated control (72.93%). MMC abolished blastocyst development at day 7 (0.00–5.68%), in contrast with substantial control development (27.98%). Day-8 blastocyst rates were also diminished in a time-dependent manner (Table 1).

Table 1 Maturation rates and parthenogenetic development after incubation of bovine oocytes with mitomycin C

Five replicates. MMC*: mitomycin C concentration in μg ml−1.

CTL: vehicle-treated control.

Maturation: eggs with a visible polar body at 24 h of IVM. Cleavage: embryos with two or more blastomeres at 48 h post-activation. D7/D8: blastocysts at 168 h and 192 h post-activation, respectively.

Different superscripts ( a–c ) in same column indicate values that differ significantly (P<0.05).

Embryonic development after bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer into mitomycin C-enucleated eggs

To demonstrate functional chemical oocyte enucleation, the introduction of a viable nucleus via SCNT should recover developmental potential after MMC enucleation (Fig. 1). MMC-enucleated eggs reconstructed with somatic cells were subject to embryonic development evaluation. Fusion rates were not affected by MMC exposure (Table 2). The incubation with MMC reduced cleavage rates after activation (66.40%) and reconstruction (64.77%), in contrast with parthenogenetic control [P(CTL): 86.50%] and the control SCNT [NT(CTL): 86.84%]. At day 7, NT(CTL) blastocyst rate (21.92%) was lower than [P(CTL): 36.50%], although higher than both [P(MMC): 0.00%] and [NT(MMC): 2.27%] (Table 2). More importantly, NT(MMC) blastocyst rate was higher than P(MMC) but remained lower than NT(CTL) and P(CTL) (Table 2). The NT(MMC+SR) had a cleavage rate similar to P(CTL) and NT(CTL), although higher than MMC-treated groups. Additionally, NT(MMC+SR) blastocyst rate was similar to NT(CTL) at days 7 and 8, but higher than P(MMC) and NT(MMC) (Table 2).

Table 2 Somatic cell nuclear transfer into chemically enucleated eggs by mitomycin C (MMC)

Five replicates. P(CTL): vehicle-treated denuded eggs; P(MMC): denuded eggs treated with 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h; NT(CTL): control nuclear transfer using egg enucleation by micromanipulation and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC): denuded eggs treated with 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC+SR): denuded eggs treated with 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h, followed by meiotic spindle removal > 1 h after MMC incubation and reconstructed with a somatic cell.

Cleavage: embryos with two or more blastomeres at 48 h post-activation. D7/D8: blastocysts at 168 h and 192 h post-activation, respectively.

Different superscripts ( a–d ) in same column differ significantly (P<0.05). NA: Not applicable.

In vivo development of bovine cloned embryos generated using mitomycin C-enucleated eggs

The ET of 21 SCNT blastocysts into 19 recipients led to five early 30-day pregnancies (23.80%) and one 60-day pregnancy (4.76%). One early pregnancy from NT(MMC) was established at day 30 but lost before day 60 (Table 3). Two further early pregnancies from NT(MMC+SR) blastocysts were lost between days 30 and 60, while only one pregnancy from NT(CTL) survived beyond day 60 (Table 3).

Table 3 In vivo development after transfer of cloned embryos obtained by somatic cell nuclear transfer to chemically enucleated oocytes by mitomycin C (MMC)

NT(CTL): control nuclear transfer using egg enucleation by micromanipulation and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC): denuded eggs treated with 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h and reconstructed with a somatic cell; NT(MMC+SR): denuded eggs treated with 10 μg ml−1 MMC for 1.5 h, followed by meiotic spindle removal > 1 h after MMC incubation and reconstructed with a somatic cell. Different superscripts ( a–d ) in same column differ significantly (P<0.05).

Discussion

Exposure of bovine oocytes to MMC did not affect their viability, as demonstrated by PB extrusion rates, therefore suggesting efficient resumption of meiosis and cell-cycle progression. The MMC concentration used above was based on studie in somatic cells for preparation of feeder cells (Llames et al., Reference Llames, García-Pérez, Meana, Larcher and del Río2015), and oocytes may tolerate even higher MMC concentrations without any detrimental effects on meiotic progression (Yuen et al., Reference Yuen, Merriman, O’Bryan and Jones2012). Remarkably, 1 h incubation in MMC was the sole time window that diminished oocyte nuclear maturation. This discrepancy may have arisen from oocyte heterogeneity caused by retrieving them from follicles of various sizes, as the oocyte response to DNA damage is progressively diminished during oocyte maturation and follicle growth in vivo (Brewen and Payne, Reference Brewen and Payne1979; Adriens et al., Reference Adriens, Smitz and Jacquet2009). This oocyte heterogeneity would therefore lead to a stochastic non-linear incubation dose–response or incubation time–response, as found in other experimental settings (Russell and Russell, Reference Russell and Russell1992; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Walker, Tesfaigzi, Schollnberger and Walker2003).

The MMC-mediated chemical enucleation was carried out during late IVM after denuding, as cumulus cells subject to DNA damaging drugs become toxic to the oocyte (Moura et al., Reference Moura, Sousa, Leme and Rumpf2008, Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zheng, Xie, Shen, Yin and Ma2015). Therefore, cumulus-enclosed oocyte exposure to MMC was avoided intentionally. This scenario demonstrates the relevance of understanding the mechanisms and possible roadblocks for enhancing the efficiency of alternative oocyte enucleation. Another indication of low or undetectable MMC cellular toxicity was the similar cleavage rates of parthenogenetic embryos from MMC-treated and non-treated eggs, although impaired post-cleavage development suggested the MMC effect on DNA replication inhibition.

The definitive demonstration of effective functional MMC-mediated chemical enucleation settles by high blastocyst rates after SCNT. However, MMC-enucleated eggs used for SCNT led to lower developmental potential than non-treated controls, from the cleavage stage onwards. Despite these facts, these cloned embryos led to higher blastocyst yields than in the MMC-enucleated parthenogenetic controls. The restoration of developmental potential by removal of MMC-treated meiotic spindles suggests that DNA damage caused by MMC is the major, if not the sole, factor responsible for SCNT embryonic arrest. Similar findings were found using functionally AD-enucleated eggs for SCNT (Moura et al., Reference Moura, Badaraco, Sousa, Lucci and Rumpf2019).

The DNA damage response (DDR) pathway detects and repairs DNA damage in eggs and embryos (Shimura et al., Reference Shimura, Inoue, Taga, Shiraishi, Uematsu, Takei, Yuan, Shinohara and Niwa2007; You et al., Reference You, Bailis, Johnson, Dilworth and Hunter2007; Yuen et al., Reference Yuen, Merriman, O’Bryan and Jones2012). If DNA lesions remain, cell-cycle arrest takes place and establishes permanent developmental block (Gjørret et al., Reference Gjørret, Knijn, Dieleman, Avery, Larsson and Maddox-Hyttel2003; Shimura et al., Reference Shimura, Inoue, Taga, Shiraishi, Uematsu, Takei, Yuan, Shinohara and Niwa2007). The effects of MMC on nucleic acids described in oocytes were similar to those of somatic cells (Tomasz and Palom, Reference Tomasz and Palom1997; Yuen et al., Reference Yuen, Merriman, O’Bryan and Jones2012). Fully grown mouse oocytes can detect interstrand cross-linking after MMC exposure, but the DDR pathway was not activated (Yuen et al., Reference Yuen, Merriman, O’Bryan and Jones2012). However, embryonic development was impaired permanently. A better understanding of the DDR pathway in eggs and early embryos (Shimura et al., Reference Shimura, Inoue, Taga, Shiraishi, Uematsu, Takei, Yuan, Shinohara and Niwa2007; Kujjo et al., Reference Kujjo, Ronningen, Ross, Pereira, Rodriguez, Beyhan, Goissis, Baumann, Kagawa, Camsari, Smith, Kurumizaka, Yokoyama, Cibelli and Perez2012; Collins and Jones, Reference Collins and Jones2016) will guide future studies to release SCNT embryos from cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis after MMC-mediated enucleation. In conclusion, MMC leads to functional chemical oocyte enucleation during SCNT and further suggests its potential for technical improvements.

Financial support

We would like to acknowledge the Universidade de Brasília and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superio (CAPES) for the scholarship to MTM. This study was supported by Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. MTM currently holds a PNPD-CAPES Fellowship.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

Experiments were carried out under current Brazilian ethical and legal standards.

Author’s contribution

MTM and RR designed the research; MTM and RVS carried out the research; MTM, CML, and RR analyzed the data; MTM and RR wrote the manuscript.