1. Introduction

In times of economic crises, many governments have turned to anti-dumping duties as a ‘safety valve’ to alleviate pressure on domestic producers. After all, a crisis itself may lower consumer demand, limit access to credit, or trigger other phenomena that reveal the economic vulnerability of domestic firms. Anti-dumping duties provide for a means to alleviate pressure from foreign competitors, by raising tariffs and therefore the cost of competing foreign products.

During the 2008–2009 global recession, officials feared a repeat of the beggar-thy-neighbor policies of the 1930s, where countries successively raised tariffs on each other's imports, thereby exacerbating the crisis. However, this outcome was largely averted. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and various academics have touted this aversion as a success of the multilateral trading system in managing protectionist pressures in a time of crisis.

While the 2008–2009 crisis did not lead to a major increase in the volume of anti-dumping measures, it did reveal the pressures incumbent on governments to take action when domestic firms come under pressure during times of crises. Moreover, these crises need not be global in nature to trigger such pressures. A supply shock, balance-of-payments mismanagement, or even bad weather can give rise to an economic crisis and raise pressures on governments to enact anti-dumping duties to protect domestic firms.

However, governments cannot accuse foreign producers of dumping and raise tariffs at will. When authorizing anti-dumping duties, WTO law requires that a government's investigating authority analyze the impact of the dumped imports on the prices of competing like products in the domestic market, including consideration of whether there has been price undercutting or price suppression of a significant degree. Price suppression refers to the prevention of price increases, which would have otherwise occurred.

How can one identify price suppression? Inevitably, the investigating authority must construct a counterfactual of domestic prices that would have resulted in the absence of dumping. Yet, the law itself is silent on how the analysis is to be done. Instead, it provides considerable discretion to the investigating authority to undertake this analysis. However, as the Appellate Body has made clear, this discretion is not without bounds.

Calculating a counterfactual price and performing a price suppression analysis is difficult, even in normal times. To do so requires that the investigating authority make certain assumptions and draw certain inferences. A foreign government may seek to challenge whether these assumptions and inferences are reasonable and grounded in credible facts. WTO adjudicators are placed in an unenviable position of deciding whether the investigating authorities’ actions overstep the bounds of the discretion afforded it in the treaty language itself.

This task of performing a price suppression analysis is made even more difficult in abnormal economic times. After all, in times of crises, the behavior of firms and consumers may deviate from those that prevail under normal conditions. This makes the task of calculating a counterfactual price as part of a price suppression analysis even more daunting for an investigating authority.

What must an investigating authority do under such conditions? What types of adjustments must it make to take account of the abnormal economic times? When does failure to make such adjustments make its counterfactual price – and therefore, its price suppression analysis – illegitimate? In the Russia–Commercial Vehicles dispute, the WTO Appellate Body (AB) was called upon to answer these questions.

This article examines the Appellate Body's decision in this dispute. Section 2 discusses the background facts of the Russia–Commercial Vehicles dispute. Section 3 provides an overview of the applicable law and past jurisprudence. Using the facts of the Russia–Commercial Vehicles dispute as a case study, Section 4 examines the difficulties confronting investigating authorities, when conducting a price suppression analysis during a financial crisis or otherwise abnormal economic circumstances. Section 5 offers some concluding thoughts.

2. Background

The specific product that underlies the case study of price suppression and dumping on which this Article will focus are light commercial vehicles (LCVs). Before discussing the facts of this dispute further, it may help to understand what specifically these are. In setting tariff rates, the Harmonized System differentiates between vehicles used primarily for the transport of people as opposed to goods or for other specialized purposes. It also differentiates between vehicles based on their physical properties, such as their weight, number of wheels, whether they are refrigerated, and so forth. In general, most governments consider these to be vehicles used for transport of commercial goods door-to-door that weigh less than 3.5 or 5 tonnes. These are primarily vans and pick-up trucks. While many producers of LCVs (like other motor vehicles) are European, American, and Japanese, they now also include producers in developing countries such as Tata, BYD, as well as the Russian producers involved in this dispute.

From 2007 through 2008, Russia enacted an applied tariff rate of 10% for LCVs. However, beginning in 2009, the applied tariff rate was raised to 25%. In 2009, Russia was not yet a member of the WTO and therefore had not bound its tariff rates.

At the same time, however, the global financial crisis hit, weakening consumer confidence worldwide. This was especially true for durable goods, such as imported motor vehicles, in many markets, including Russia. In addition, the world price of oil, Russia's main export, plummeted, triggering a more than 20% decline in the ruble against the US dollar between 2008 and 2009 (8.5% in real terms). The perfect storm of higher tariffs, ruble depreciation, and greater economic uncertainty hit foreign auto producers hard, causing them to lose much market share in the Russian market and that of the Eurasian Customs Union. Whereas the combined market share of imports from foreign producers amounted to 75% in 2008, it had plummeted down to 35% in 2009.Footnote 1

The main beneficiaries of this shift were Russia's domestic producers – Sollers-Ellabuga LLC (‘Sollers’) and Gorkovsky Avtomobilny Zavod (GAZ). The combined market share of the two companies increased from 24% to an astonishing 65%

in the Russian and Eurasian Economic Union market. By 2011, their market share had recovered back in 2009. Of the two, Sollers was the dominant firm. For the period 2008–2011, Sollers accounted for 87.9% of the LCVs produced.Footnote 2

Over the next two years, however, as global market conditions returned to normal, German and Italian producers of LCVs recovered their lost position to what it was in 2008. By contrast, other foreign car producers failed to recover. Whereas these other firms once held a market share that was larger than that of the German and Italian producers, by 2009 this was no longer the case. Two years later, in 2011, the market share of these other foreign producers had plummeted to a negligible level of 1%.

The gains made by German and Italian producers in 2010 and 2011 came not only at the expense of other foreign producers but also at the expense of the two domestic Russian firms. They too saw their market shares drop, by 2% in 2010 and by a further 6% in 2011.

Finally, on 22 August 2012, Russia became a member of the WTO. As part of its accession, Russian authorities agreed to bind its tariff rate for LCVs at 10%. Domestic producers, therefore, sought ways to raise the tariff rates for imported LCVs back to earlier levels.

2.1 Russia's Anti-Dumping Investigation on Light Commercial Vehicles

Alarmed by the rapid inroads made by their German and Italian competitors, Sollers filed a complaint on 3 October 2011 with the Department for Internal Market Defense (DIMD) of the Eurasian Economic Commission, alleging dumping of LCVs by German and Italian firms.

In response to this petition, DIMD initiated an investigation on 16 November 2011. Initially, it defined the domestic producers of the domestic like product to include both Sollers and GAZ. DIMD sent questionnaires to both firms and received responses from both. However, upon reviewing these responses, DIMD determined the data provided by GAZ was ‘deficient’. DIMD then proceeded to redefine the domestic industry producing the like product to consist of only Sollers and relied solely upon data submitted by Sollers in analyzing the impact of the dumped product on domestic industry.Footnote 3

Before imposing anti-dumping duties, an investigating authority must conduct both a dumping investigation and an injury investigation. Not only must it find evidence of dumping by the foreign firms, but before duties can be imposed, it must also find that the domestic industry was injured as a result of the dumped imports. The periods of investigation for these two investigations as conducted by DIMD, however, were not identical. For the dumping investigation, DIMD considered the relevant period to be from the second half of 2010 through the first half of 2011 (i.e., July 2010–June 2011). It therefore collected data for this 12-month period. For the injury investigation, however, DIMD considered a longer period of time stretching over four years (2008–2011), that included the full calendar years.

A year later, in November 2012, the investigating authorities announced that they would extend the investigation, without issuing any preliminary duties. Finally, on 16 May 2013, DIMD announced that it would impose anti-dumping duties of 29.63% for German LCVs and 23.03% for Italian LCVs.Footnote 4

2.2 WTO Challenge and Panel Ruling

On 21 May 2014, the European Union filed a complaint alleging that the Russian anti-dumping measures violated several of its WTO commitments. The dispute represents the first (and to date, only) time that Russian trade remedies have been challenged before WTO dispute settlement. Specifically, the EU alleged that Russia violated more than 20 different obligations of the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement (ADA), as well as GATT Article VI.Footnote 5

Following unsuccessful consultations, a Panel was requested in September 2014 and composed in December 2014. In June 2015, the Chair of the Panel informed the WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) that its work was delayed a result of the lack of available experienced lawyers within the WTO Secretariat. In December 2015, two of the three original Panel members resigned. The WTO Director-General appointed their replacements ten days later.Footnote 6 Altogether, more than two years would pass since the Panel's original composition before its report was finally circulated to the WTO membership on 27 January 2017.

On numerous counts, the Panel sided with the EU. The Panel concluded that DIMD violated Articles 3.1 and 4.1 of the ADA in defining the ‘domestic industry’ to include only Sollers and excluding GAZ in its final report, after initially including both firms in its initial definition and requesting data from both.Footnote 7 It also concluded that DIMD violated Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the ADA in its price suppression analysis, as well as Articles 3.1 and 3.5 of the ADA in relying upon its price suppression analysis in its causation analysis.Footnote 8 Finally, the Panel held that DIMD violated: (a) Article 6.5 of the ADA in treating certain items of information as confidential when the submitters had not shown good cause for confidential treatment, and (b) Article 6.9 of the ADA because DIMD failed to inform all interested parties, especially two exporters (Daimler AG and Volkswagen AG) of certain essential facts, meaning information that was treated as confidential in its investigation.Footnote 9

However, it did not rule in favor of the EU in its entirety. The EU had asserted a claim that DIMD's treatment of several factors in its injury analysis violated Articles 3.1 and 3.4 of the ADA. Evaluating these factors one-by-one, the Panel, in most instances, rejected the EU's arguments, finding that the EU failed to demonstrate that DIMD's evaluation of a given factor was not based on an objective examination of positive evidence.Footnote 10 The EU also asserted that DIMD failed to take into account four required factors, thereby violating Article 3.4 of the ADA. For one of these factors – the magnitude of the margin of dumping – the Panel agreed with the EU.Footnote 11 For three of the factors, however, Russia retorted that DIMD had considered them in the confidential version of the report. The Panel then proceeded to examine the confidential version of the report, leading it to find that the EU failed to establish that the DIMD's treatment of these factors amounted to a violation of Articles 3.1 and 3.4.Footnote 12

2.3 Appellate Body Ruling

A few weeks after the final Panel report was circulated, both the EU and Russia announced their intention to appeal. Both parties filed notices in February 2017.Footnote 13 The entire appeal took over a year, with the final AB report circulated in March 2018 and adopted on 9 April 2018. Altogether, the AB was asked to consider five issues on appeal.

First, Russia challenged the Panel's ruling that DIMD improperly defined the domestic industry. The AB upheld the Panel's ruling that DIMD re-definition of the domestic industry, in which it chose to exclude GAZ without explanation after seeking information from it, amounted to a violation of Articles 3.1 and 4.1 of the ADA.Footnote 14

Second, the EU challenged the Panel's actions concerning its rulings on Articles 3.1 and 3.4, regarding the treatment of certain information by DIMD in its injury analysis. The Appellate Body found that the Panel acted inconsistently with Article 11 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) and Article 17.6(i) by relying on the confidential investigation report in its evaluation of the EU's claims.Footnote 15 The AB therefore reversed the Panel's finding that the EU had failed to establish that DIMD's failure to consider three of the required injury factors amounted to a violation of Articles 3.1 and 3.4 of the ADA.Footnote 16 However, the AB then determined that it could not complete the analysis, and hence, it could not reach a conclusion as to whether DIMD's failure to consider the three required factors did indeed amount to a violation.Footnote 17

Third, the EU argued that the Panel erred in finding that the DIMD was not required to evaluate the inventory information of a related dealer (Turin Auto) when examining injury to domestic industry. The AB rejected the EU's argument, agreeing with the Panel that consideration of such information would to take place on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 18

Fourth, Russia argued that the Panel erred in considering that a violation of Article 6.5 of the ADA under certain conditions leads to an automatic violation of Article 6.9 of the ADA. The AB agreed, clarifying that the two inquiries are separate and distinct.Footnote 19 The AB then accepted the EU's request to complete the analysis, and, upon doing so, found that the DIMD's failure to disclose certain essential facts did indeed constitute a violation of Article 6.9 of the ADA.Footnote 20

Finally, the AB engaged in extensive discussion of the Panel's ruling concerning price suppression and the ability of the domestic market to absorb price increases. While the AB held that the Panel did not err in its interpretation and application of Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the ADA, it found that the Panel acted inconsistently with Article 11 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding because the ‘Panel's findings concerning the DIMD methodology, long-term price trends, and the degree of price suppression are not coherent and consistent with the Panel's earlier finding that the manner in which the DIMD used the 2009 rate of return to determine the domestic price target’.Footnote 21 It also faulted the Panel for having undertaken an assessment of the relevant evidence of DIMD's investigation record when considering whether the domestic market could further absorb price increases.Footnote 22 After reversing the Panel on this point, the AB then completed the analysis and nevertheless found DIMD to have acted inconsistently with Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the ADA.Footnote 23 These elements of the ruling will be discussed further below.

3. Constructing Counterfactuals for a Price Suppression Analysis: How Much Discretion is Afforded to Investigating Authorities?

This Article hones in on one element of the AB ruling that merits closer attention – namely, what is required of an investigating authority when conducting a price suppression analysis. The concept of price suppression is the prevention of price increases, which otherwise would have occurred. In this context, the argument is that but for the dumped imports, the domestic producer would have otherwise been able to increase prices for its product further and reap higher profits. It, therefore, is injured by its foreign competitor, and anti-dumping duties are required as a response.

How can one tell if prices for a given good are abnormally lower than what should prevail under ordinary conditions? Moreover, even if they are, how can one tell whether it is the action of foreign competitors that is preventing prices from rising, as opposed to a number of other confounding factors?

To discern whether price suppression has occurred inevitably requires the investigating authority construct a counterfactual. How is it to do so? What discretion does an investigating authority have in terms of how it performs its analyses, and when does an investigating authority overstep its bounds?

Before diving into an examination of the AB's ruling in this specific case, it bears examining the applicable law as well as prior AB cases discussing such issues. The notion of price suppression, as an element of an anti-dumping investigation, arises out of Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the ADA, which sets forth what is required as part of an injury investigation. Article 3.1 of the ADA sets forth what is required of an investigating authority when conducting an injury inquiry. It reads as follows:

A determination of injury for purposes of Article VI of GATT 1994 shall be based on positive evidence and involve an objective examination of both (a) the volume of the dumped imports and the effect of the dumped imports on prices in the domestic market for like products, and (b) the consequent impact of these imports on domestic producers of such products.

Article 3.2 of the ADA then clarifies what is required as part of the examination of the effect of dumped imports on prices of domestic like products, as provided in Article 3.1. It is in this paragraph that the notion of a price suppression analysis is discussed, albeit limitedly. Article 3.2 reads:

With regard to the effect of the dumped imports on prices, the investigating authorities shall consider … whether the effect of such imports is otherwise to depress prices to a significant degree or prevent price increases, which otherwise would have occurred, to a significant degree. No one or several of these factors can necessarily give decisive guidance.

Note then that the two provisions require that an investigating authority, as part of its injury determination, must examine the impact of dumped imports on domestic prices for the like product, of which one possible impact might be price suppression. However, Article 3.2 does not provide any methodological guidance for how this price suppression analysis is to be done. Nor does it require that the investigating authority make a definitive determination as to whether the effect of dumped imports is significant price suppression. The language simply states that the investigating authority must make such an inquiry on the basis of positive evidence and that its examination must be objective.

The silence of Articles 3.1 and 3.2 on the precise methodological requirements that must be followed in a price suppression analysis, on first glance, appears to suggest that negotiators intend to provide investigating authorities with considerable flexibility and leeway in terms of how they perform this analysis. So long as the examination is objective and based on actual evidence, the investigating authority retains considerable discretion.

The bounds of this discretion have been clarified somewhat in a handful of previous cases. In Mexico–Anti-Dumping Measures on Rice, the AB confirmed that Articles 3.1 and 3.2 do not prescribe a particular methodology, and therefore, an investigating authority enjoys a certain discretion. Nevertheless, the AB noted:

Within the bounds of this discretion, it may be expected that an investigating authority might have to draw on reasonable assumptions or draw inferences. In doing so, however, the investigating authority must ensure that its determination are based on ‘positive evidence’. Thus, when, in an investigating authority's methodology, a determination rests upon assumptions, these assumptions should be derived as reasonable inferences from a credible basis of facts, and should be sufficiently explained so that their objectivity and credibility can be verified.

… An investigating that uses a methodology premised on unsubstantiated assumptions does not conduct an examination based on positive evidence. An assumption is not properly substantiated when the investigating authority does not explain why it would be appropriate to use it in the analysis.Footnote 24

In the China–GOES case, the AB once more re-affirmed that the investigating authority's price suppression analysis must be based on ‘positive evidence’ and an ‘objective examination’ of the price effects.Footnote 25 Moreover, the AB clarified that it is insufficient for an investigating authority to simply engage in a trend analysis of what is happening to domestic prices for its price suppression inquiry.Footnote 26 Instead, the AB stipulated that an investigating authority, when performing a price suppression analysis, ‘is required to examine domestic prices in conjunction with subject imports in order to understand whether subject imports have explanatory force for the occurrence of significant … suppression of domestic prices’.Footnote 27

This interpretation of Articles 3.1 and 3.2 of the ADA give rise to the need for investigating authorities to perform a counterfactual analysis in an anti-dumping investigation with allegations of price suppression. The investigating authority cannot simply engage in a trend analysis of what has happened to prices during the period of alleged dumping to show that prices were kept down. Rather, the investigating authority must offer objective proof that, absent the alleged dumping, prices would have otherwise been higher. Hence, the methodology and assumptions underlying the counterfactual analysis are of significant importance whenever a domestic industry seeks protection through anti-dumping duties and alleges price suppression.

4. Case Study: Examining DIMD's Counterfactual Analysis

What constitutes a proper counterfactual analysis, especially when there is an economic crisis or shock during the period of investigation? In this next section, we use the Russia–Commercial Vehicles dispute as a case study to illustrate some of the difficulties that can arise when the counterfactual analysis encapsulates a period of abnormal economic activity.

4.1 Trend Analysis

During the period of the injury investigation, 2008–2009, the average annual domestic price of LCVs increased by 33.5% in ruble terms, with most of that increase coming in 2009, when the ruble price soared by 25.5% (see Table 1). This upward trend took place along side a price of imports that also soared in ruble terms in 2009 but fell in the subsequent two years to end the period at 7% higher than 2008.

Table 1. Annual percentage changes in weighted average prices and unit costs, 2009–2011

Note: †Import price include customs duties.

Source: Author's calculations and DIMD investigation report (non-confidential version), Tables 4.2.5 and 5.2.

The EU argued the fact that both domestic and imported prices trended upwards contradicted the DIMD's finding of price suppression. However, the Panel rejected this argument on the grounds that price trends alone are uninformative about price increases that ‘otherwise would have occurred’. Thus the Panel reinforced the conclusion of the China–GOES ruling that trend analysis is no substitute for counterfactual analysis.

This case provides a good illustration of the wisdom of that conclusion, because the price trends were significantly affected by the macroeconomic factors having little to do with dumping. In particular, the period was one of relatively high inflation (9% on average), a large depreciation of the ruble in 2009, and rising unit costs. The effect the exchange rate can be seen in Table 1, where the bottom three rows show the prices and unit costs in US dollar terms. There we see that import prices fell overall, and the upward domestic price trend was more modest and in line with cost increases. Moreover, we see an almost perfect linear fit between domestic price changes and unit cost changes.

4.2 DIMD's Counterfactual Analysis

In this case, the investigating authority estimated the counterfactual domestic price as a constant markup over the observed average cost of the domestic producer.Footnote 28 The markup was chosen to be that which would give the domestic producer ‘reasonable rate of return’, which DIMD took to be the profit margin of the domestic producer in 2009. In other words, the counterfactual price in each year was chosen to be that which would produce the 2009 profit margin, given the actual average cost in that year.

Some arithmetic may help clarify this point. The profit margin (M) of a firm is defined as

Noting that revenue is defined as price multiplied by the quantity sold, and total cost divided by quantity equals the unit (or average) cost of production (AC), the above expression can be rearranged to produce

Fixing the profit margin at the 2009 level and allowing the price to vary over time with AC amounts to choosing the counterfactual or ‘target price’ in each year to be

Thus, the target price is a constant proportional markup over AC.Footnote 29 While the markup is not disclosed in the Panel Report, data provided in the DIMD's Investigation Report suggest that the profit margin in 2009 was 24.4%, in which case the target price is roughly a 32% markup over AC.Footnote 30

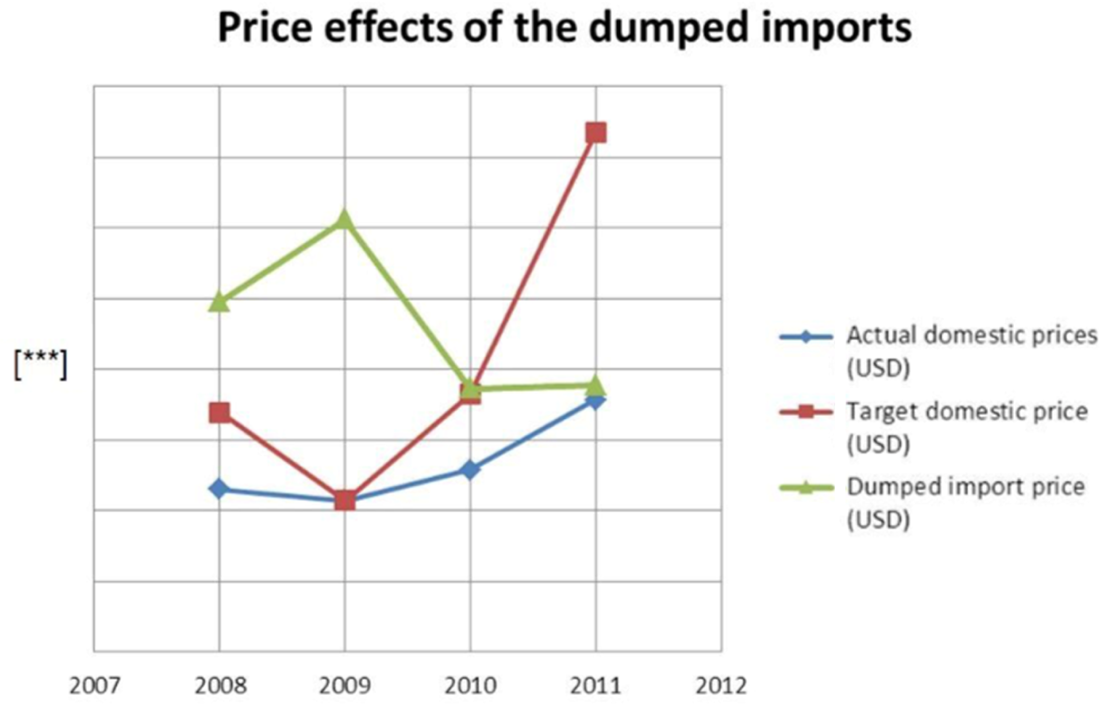

This target price was discussed in the Panel Report and reproduced below as Figure 1. The target price increased dramatically after 2009, as production costs increased. Meanwhile domestic prices rose far more modestly, and the price of imports fell. The DIMD concluded that because the domestic price failed to keep pace with the target price, and that this occurred along side an increase dumped imports and declining import prices, dumped imports had suppressed domestic prices to a significant degree.

Figure 1. Comparison of target with actual prices in US dollars

Among the numerous objections the EU raised about the DIMD's price suppression analysis, the two most important involved direct challenges to the validity of the target price. First, the EU argued that, because the 2009 profit rate was abnormally high due to the financial crisis, it should not have been used as the benchmark without adjustments. Second, noting that domestic prices in ruble terms had already increased significantly in 2009, and the raw materials costs continued to rise, the EU complained that the DIMD ‘failed to examine the likelihood that the market would accept additional domestic price increases’. Put differently, the EU questioned whether the cost increases apparently driving up actual domestic prices would have been fully passed through to domestic prices absent dumping, as assumed in the counterfactual. Taken together, these arguments challenge the target price as a true reflection of the price that would have prevailed in the years after 2009 absent dumping.

4.3 Rate-of-Return Assumptions

Both the Panel and the AB found that the DIMD acted inconsistently with Articles 3.1 and 3.2 because it failed to consider the financial crisis in determining the appropriate rate of return for the counterfactual analysis. Neither body challenged the use of constant markup over AC based on a benchmark profit margin as legitimate counterfactual methodology. Neither body faulted DIMD's reasons for using 2009 as a benchmark, nor did they state that the financial crisis necessarily undermined 2009 as a benchmark. Rather they faulted DIMD for apparently ignoring this possibility.

The notion of constructing a price on the basis of cost plus a reasonable profit is hardly novel in antidumping cases. Indeed, it is one of legally recognized methods of constructing a dumping margin. Article 2.2 of the Antidumping Agreement clarifies that when actual comparator prices are unavailable, ‘the margin of dumping shall be determined by comparison with … the cost of production in the country of origin plus a reasonable amount for administrative, selling and general costs and for profits’, and that these reasonable amounts, ‘shall be based on actual data pertaining to production and sales in the ordinary course of trade of the like product by the exporter or producer under investigation’ when possible.

According to the Panel Report,

We do not mean to suggest that an investigating authority may not rely on a benchmark rate of return in constructing a target domestic price that is less than ideal, so long as it recognizes and takes into account relevant factors in its consideration. An objective and unbiased investigating authority in the underlying investigation would, in our view, have questioned whether the effects of the financial crisis, including the preference for the domestic product, would continue and thus whether the high rate of return reported in 2009 could reasonably be expected in the subsequent years in the absence of dumped imports. Nothing in the DIMD's Investigation Report suggests that it undertook such an assessment in its consideration of price suppression.

As already mentioned, the Panel Report did not disclose the profit margin for Sollers in any year; however, the DIMD itself reported that it had risen by 9.4 percentage points in 2009 and declined by 9.0 percentage points 2010. Coupled with the fact that the domestic price and the unit cost rose by 25.5% and 13%, respectively, in 2009, we can infer that the GPM in 2008 was 15%, rising to 24.4% in 2009 and falling back to 15.4% in 2010. Had DIMD used either 2008 or 2010 as the benchmark, the markup would have been about 18%. In this case, the counterfactual price would have been below the actual price in 2009, roughly equal to 2010, and greater than in 2011 by about 20%.

The reason DIMD gave for using 2009 as a benchmark was because that was the year in which dumped imports were minimal and therefore not causing injury. DIMD rejected 2008 on the grounds that it was the startup year for Sollers in the LCV market, and it rejected 2010 on the grounds of it being tainted by a large increase in dumped imports. The Panel agreed with this reasoning.

The problem was that DIMD failed to consider whether the relatively high 24.4% profit margin in 2009 was due to recessionary factors not likely to persist in subsequent years, even without dumping. DIMD could have argued that one of the key factors pushing up the domestic profit margin in 2009 was the 2009 tariff hike, and that this factor was persistent. It could have argued that 2009 was actually a low point in demand for LCVs in Russia, whereas subsequent years would have actually been more favorable. It could have argued that the ruble depreciation in 2009 was roughly offsetting of the calculated dumping margin, which was not challenged.Footnote 31 The DIMD did not make any of these arguments its Investigation Report, and for this reason, it was found in violation.

However, the unanimity of both the Panel and the AB in requiring the investigating authority to take into account the normality of market conditions in a benchmark year points to a deeper issue, namely, that the counterfactual price markup should not be regarded as constant in the face of changing market conditions. The DIMD implicitly recognize that market conditions matter for profit margins, and thus markups, when acknowledging that the condition of being a startup (in 2008) and the presence of subject imports (in 2010) depressed profit margins in those years. It is entirely valid to ask that an investigating authority consider other relevant economic factors as well. Not only this, but a proper methodology would compare the actual price with a counterfactual price that controls for all these other relevant factors, such that the only difference between the two is the affect of dumping. To the extent that the Panel/AB ruling moves price suppression methodology in this direction in the future is a good decision.

4.4 Analysis of Market Ability to Absorb Additional Price Increases

The limitations of estimating a counterfactual domestic price as a constant markup over AC grow even more serious when considering the pass-through of cost increases to prices.

The Panel rejected the EU argument that DIMD was required to consider whether the market would absorb price increases beyond those that took place in its consideration of price suppression. However, the AB overturned this decision.

The European Union had argued that the DIMD should have considered this issue for three reasons: (a) domestic prices increased between 2008 and 2009 and again between 2010 and 2011; (b) there were ‘quality issues’ with Sollers' LCVs that would have limited any price increases; and (c) there was a significant increase in the domestic industry's cost of production due to the increasing cost of raw materials.

The Panel rejected these arguments one by one. First, it argued that past price increases do not by themselves call into question the ability of the market to accept more, and thus is was incumbent on the EU to show more evidence, which it did not. Second, it argued that the evidence of quality problems with Sollers’ LCVs was weak, as it was based on only a single magazine article. Third, and most remarkably, the Panel stated

concerning the increasing costs of production, we note that producers will normally seek to pass increased costs of production on to consumers in order to maintain their profit margins. There is no evidence and no arguments on the record to indicate that the rising cost of production could not have been passed on, in the form of increased prices, to consumers in the absence of dumped imports. Accordingly, we consider that the increasing costs of production cannot call into question the market's ability to accept additional price increases.

This final point is demonstrably false. Basic economic theory posits that firms wish to maximize profits, not maintain profit margins. If raising prices to maintain a profit margin were to significantly reduce the firm's quantity sold, such a move could reduce profits and therefore be suboptimal.

Figure 2 shows that Sollers passed on approximately one quarter of the percentage changes in unit costs to prices. The figure shows this in relation to the DIMD's assumption of complete pass-through, which follows from its target price as defined in equation (3). Complete pass-through means that an increase in unit cost of any percentage should lead to the same percentage increase in price. The fact that Sollers's actual price is only one quarter as responsive as that is, in DIMD's view, the consequence of dumping. However, this not the only possibility.

Figure 2. Pass-through of costs to prices in US dollars (% changes)

Economic theory tells us that a profit-maximizing firm should follow the following simple pricing rule:

where P is the profit-maximizing price, MC refers to the firm's marginal cost of production, and ɛ denotes the elasticity of demand for the firm's product. The elasticity of demand measures the percentage reduction in demand (hence quantity sold) that would occur in response to a 1% increase in price. It is a measure of the responsiveness of consumers to price changes, and the more responsive consumers are, the smaller is the firm's markup over marginal cost.

Note that equation (4) is not an alternative to equation (2). They are both true. The difference is that (4) is a statement about the behavior of the profit-maximizing firm, whereas (2) is simply an accounting identity. The pricing rule (4) therefore has predictive power, whereas equation (2) can only be observed after the fact.

A comparison of (4) with (3) reveals two important deviations of the DIMD's target price from profit-maximizing behavior. First, changes in the profit-maximizing price are driven by changes in marginal cost, whereas changes in the target price are driven by changes in average cost. Second, the markup over marginal cost implied by the profit-maximizing price depends on the elasticity of demand, which may change over time in response to cost changes. The target price, on the other hand, maintains a fixed markup over average cost.

To see the first point more clearly, consider the case where the marginal cost is independent of the quantity produced (i.e., each unit of output costs the same as the next). In this case, average cost is related to marginal cost according to:

where AFC is average fixed cost (i.e., fixed cost per unit of quantity). Thus, the difference between average and marginal cost stems from the presence of fixed costs (e.g., manufacturing overhead). To the extent that changes in average cost are driven by changes in AFC, rather than MC, the target price, which moves in tandem with average cost, will fluctuate more than the profit-maximizing price, which is tied to MC. This is one potential explanation for the contrasting pass-through rates shown in Figure 2. While there is not enough information in the factual record of this case to support this explanation, it nevertheless highlights a danger of the DIMD method.

The deeper problem, and recurring motif of this case, is that DIMD's target price is based on a constant markup, even though markups may vary over time with market conditions, even ‘in the ordinary course of trade’. Many empirical studies document that marginal cost shocks are not fully passed through to prices at the firm level. The observed sluggish response of prices to cost disturbances is also reflected in prices being substantially less volatile than costs. For example, a substantial body of empirical work documents that exchange rate pass-through to prices is delayed and incomplete (Engel, Reference Engel1999; Parsley and Wei, Reference Parsley and Wei2001; Goldberg and Campa, Reference PK and Campa2006; Atkenson and Burstein, Reference Atkenson and Burstein2008). This is commonly referred to as ‘pricing-to-market’ (Krugman, Reference Krugman1987). Recent firm-level evidence of incomplete pass-through of tariff shocks to prices is found in Ludema and Yu (Reference Ludema and Yu2016) and De Loecker (Reference De Loeker, Goldberg, Khandelwal and Pavcnik2016). Perhaps of greatest direct relevance, Gron and Swenson (Reference Gron and Swenson2000) and Hellerstein and Villas-Boas (Reference Hellerstein and Villas-Boa2010) study cost pass-through to prices in the US automobile market, finding firm-level cost pass-through elasticities to be less than one half for most models. This is consistent with the 0.25 cost pass-through elasticity for domestic LCV prices shown in Figure 2.

The exact reasons behind incomplete cost pass-though is an area of much study in the economics literature. Krugman (Reference Krugman1987) argued that firms price to market to avoid large swings in market share. Atkeson and Burstein (Reference Atkenson and Burstein2008) argue that the greater the firm's market share the smaller is ɛ (i.e., the less responsive consumers are to an increase in the firm's price) and thus the greater is the firm's markup over marginal cost. This could explain why, for example, Sollers's profit margin was so high in 2009: because it gained significant market share during the crisis. But it would also imply that Sollers's profit margin would have decreased again as it gave back market share in 2010 and 2011. In addition, it implies that increases in marginal cost, due to raw materials price increases, for example, would not be fully passed on to consumers, because higher marginal cost implies a loss of market share and therefore a lower markup.

Fortunately, the AB overturned the Panel's finding on this issue, though not necessarily for the right reasons. The AB argued that there was evidence on the DIMD's investigation record relating to increases in domestic prices and cost of production as well as alleged quality issues that it deemed relevant to the question of whether the market could absorb additional price increases.

We consider that the DIMD should have explained in its investigation report, at a minimum, why this evidence does not show that the target domestic price relied on by the DIMD was a price that would not have occurred in the absence of dumped imports. This is because, were the DIMD to rely on a constructed target domestic price that could not have been absorbed by the domestic market, the target domestic price would not correspond to one ‘which otherwise would have occurred’ in the absence of dumped imports within the meaning of Article 3.2 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement.Footnote 32

5. Conclusion

Previous case law had established that investigating authorities in antidumping cases must conduct a counterfactual analysis to evaluate price suppression. That is, they must compare actual domestic prices with the counterfactual domestic prices that would have occurred in the absence of dumping. This case goes a step further to establish that in choosing data to construct counterfactual prices, in this case profit margins and average costs, the investigating authority must consider how such data are affected by market circumstances. If the data are likely to vary with market circumstances, even in the absence of dumping, then the investigating authority cannot blindly assume that the data chosen for a given base year should apply to all years in the period of investigation. To allow this would not only violate the ‘would have occurred’ clause but would incentivize the investigating authority to cherry pick the base year to maximize the appearance of price suppression.

This article concludes that the Appellate Body got this holding right, but perhaps did not go far enough. There is wealth of evidence that, particularly in imperfectly competitive markets such as motor vehicles, firms do not fully pass on marginal cost changes to prices. Therefore, a methodology that assumes a constant markup over marginal (or worse, average) cost, such that percentage cost changes are matched one-for-one with percentage changes in the counterfactual price, should be presumed false.

The temptation to resort to trade remedies increases during times of economic crises. While investigating authorities enjoy a degree of deference in how they perform their economic analyses for such periods, their analyses must align with objective reality. Future jurists must continue to engage in the important task of ensuring that investigating authorities do not base their decisions on unrealistic or lazy assumptions that fail to match up with positive evidence.