1. Introduction

Trade preferences in favor of developing countries have been granted by most industrialized countries since the 1970s (Pomfret, Reference Pomfret1986; Cooke, Reference Cooke2011). It is considered as a useful way of providing poorer countries with better opportunities for economic growth. Better access to developed countries’ markets is expected to provide certain economic advantages such as higher export volumes and prices and familiarity with Western markets (Collier and Venables, Reference Collier and Venables2007).

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) was signed into law in May 2000 to encourage increased trade and investment between the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). It offers beneficiary countries trade preferences by reducing tariff and nontariff barriers as a complement to foreign aid. AGOA provides eligible countries with duty free access to the US market for over 1800 products in addition to those available under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) (Seyoum, Reference Seyoum2007; Didia et al., Reference Didia, Nica and Yu2015). AGOA includes a special apparel rule of origin for lesser developed members, which allows them to use non-US, non-AGOA fabric in making apparel for duty-free export to the US market. The Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 extended AGOA, including the third-country fabric provisions, for ten years through 2025 (USITC, 2014; USTR, 2016).

AGOA has been subject to various amendments over the years. AGOA II (2002) enhanced preferential access of Sub-Saharan Africa countries’ exports to the US market while AGOA III (2004) extended AGOA till 2015 and expanded the third country fabric provision

(duty/quota-free access for apparel made from fabric originating anywhere in the world).

AGOA IV (2006) amended portions of the AGOA provisions and further expands the third country fabric provisions (USITC, 2014). Historically, preference rules on apparel imports have been stringent. These rules often required at least three transformational processes (yarn, fabric, assembly) in beneficiary countries to qualify for US duty free treatment. These rules made it difficult for many developing countries to qualify for such benefits due to the capital and technology requirements of fabric production. The AGOA rule made an important exception to this requirement. It not only gave all beneficiary countries extensive duty free, quota-free access to the US market but also generous rules of origin that provided a waiver for wearing apparel. The waiver allowed less developed beneficiary countries to use third-country fabrics or yarn and still export clothing under AGOA preferences. Countries not defined as less developed (Mauritius, South Africa) are required to meet GSP rules of origin for clothing that requires the use of US or regional yarns and fabric. This helped boost beneficiary clothing exports to the US from 730 million USD (2000) to 1.4 billion USD (2019) (Agoa info.com).

AGOA IV provides the US president powers to accord such benefits for apparel that is both uncut (or knot to shape) or sewn or otherwise assembled in beneficiary countries from fabric or yarn not formed in the US or beneficiary country. This is based on a determination by a delegated committee that such yarns or fabrics cannot be supplied by the domestic industry in commercial quantities in a timely manner. During the 2001–2020 period, 92% of apparel exports estimated at 21.05 billion USD entered the US duty free under AGOA. AGOA removes import duties that could be as high as 32% for certain articles of apparel, providing beneficiary country exporters with a significant boost to their competitiveness in the US market.

Country eligibility is based on certain criteria: progress toward establishing market-based economic reforms, policies to reduce poverty, combat bribery and corruption, as well as protect internationally recognized worker rights. It also requires countries to establish the rule of law and political pluralism, and to reduce barriers to US trade and investment. Countries may not be eligible if they exceed the lower band of the World Bank's definition of a high-income country (19 USC; USTR, 2016).

Trade preferences are not enough to explain export performance by beneficiary countries. Instead, such relationships are moderated by rule of law (proxy for the regulatory environment) as well as inward foreign direct investment (FDI) which is an increasingly important driver of trade flows (due to the growing fragmentation of production and the development of distribution networks across countries). The research is driven by two key questions:

1. What is the role of AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions in increasing beneficiary country exports?

2. What is the role of rule of law and FDI in moderating the main effects of AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions on export performance?

This study complements prior research on the positive effects of trade preferences on export performance (Lederman and Ozden, Reference Lederman and Ozden2004; Nouve, Reference Nouve2005) by measuring trade preferences in terms of tariff concessions for each product exported to the US from beneficiary countries (based on the dollar value of tariffs that would have been paid on imports if the most-favored nation (MFN) tariff has been imposed). Previous studies on trade preferences have only used indicator variables as a proxy for trade preferences (0 for pre-AGOA and 1 for AGOA years). We offer a more comprehensive, product-based approach to the analysis of trade preferences. Moreover, many of the prior studies were conducted during the early years of AGOA and do not examine its effects over several years.

AGOA is a term used to measure AGOA with a dummy (0 if a country is not AGOA beneficiary and 1 if it is a beneficiary) whereas AGOA tariff concessions are intended to measure AGOA using tariff concessions. They are different ways used to measure AGOA.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1 Dynamic Effects of Preferences

Production of goods in many developing countries encounters diminishing returns because of the small size of their markets. Large markets of trade preference donor countries such as the US generate a supply response from firms that are motivated to exploit the potential of unrealized opportunities. Large markets enable firms in beneficiary countries to achieve economies of scale at the plant and industry level and benefit from learning effects from competing with established producers. Large initial investments necessitate a growing sales volume to realize a reasonable rate of return and in the absence of large domestic markets, access to foreign markets via exports becomes critical.

Economies of scale tend to strengthen the general case for trade preferences. Krugman's model (Krugman, Reference Krugman1979) predicts that when two countries are open to trade, market size is enlarged, and economies of scale come into play and production costs can be reduced for all goods. General equilibrium modeling also suggests that economies of scale have the effect of increasing the gains from trade (Gruen, Reference Gruen1999).

The Heckscher–Ohlin ‘factor proportions’ model indicates the benefits of exchanging products which embody different factors proportions. The theory states that differences in factor endowments of the nations and differences in factor proportions of producing different commodities account for differences in comparative costs and hence form the basis for international trade (Heckscher and Ohlin, 1991). The gains from trade in the Heckscher–Ohlin model (like the Ricardian model) are those derived from specialization that arise because of differences between countries. For example, the US meat processing industry has been consolidating over the years and has managed to attain economies of scale leading to the ability to deliver meat products at lower prices to the world market (Lee and Schluter, Reference Lee and Schluter2001). US comparative advantages in the industry are based on its abundant farmland, feed production, and consolidation that allowed it to achieve scale economies (unit costs decrease with the scale of production). Heckscher–Ohlin's theory also underscores the need to remove trade barriers to expand beneficial trade. Deardorff (Reference Deardorff1979) shows that with intermediate inputs, a trade barrier on an input that raises its price can make production of the final good too costly even though the country might otherwise be a relatively low-cost producer of the final good. The empirical literature on new trade theories may suggest small potential gains from mild unilateral protection (Venables and Smith, Reference Venables and Smith1986; Helpman and Krugman, Reference Helpman and Krugman1989). However, bilateral, and multilateral trade liberalization tend to imply much greater welfare gains once we allow for imperfect competition and scale economies (Dixit, Reference Dixit1988; Francois and Roland-Holst, Reference Francois and Roland-Holst1997).

An important feature of increasing returns to scale tends to be interaction and learning effects (Brosnan et al., Reference Brosnan, Doyle and O'Connor2016). Learning effects imply that producers learn by interactions and experience because of which unit costs of production may decrease. Trade preferences provide opportunities for multinational firms to globalize their input sourcing, i.e., stimulating the internationalization and fragmentation of production across countries traded within global production networks (Keane, Reference Keane2013). External economies develop due to spillover and network effects resulting from the clustering of productive activities (Krugman and Venables, Reference Krugman and Venables1995). Network theory suggests that firm networks influence their development possibilities and strategic actions. Many studies indicate how viable internationalization is achieved through linkages to foreign firms in global supply chains.

2.2 The Theory of Strategic Trade Demands

Firms’ trade demands have a long history in the international trade literature (Milner and Yoffie, Reference Milner and Yoffie1989; Osgood, Reference Osgood2017). Historically, firms have demanded for trade barriers in the form of tariffs or quotas in the event of a serious competitive threat from imports or in response to the behavior of their foreign rivals and their governments. Recent studies, however, indicate that exporters and manufacturing firms with extensive global intra-firm trade flows are opposed to protectionism at home (Osgood, Reference Osgood2017). This is because protectionism imposes higher costs on their business by restricting access to low-cost imported inputs and disrupting intra-firm trade flows, thus reducing their relative competitiveness. These firms consider free trade as a profit maximizing strategy. They also believe that protectionism at home could increase the probability of retaliation by foreign governments against their investments or exports. For example, when the US imposed tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines in January 2018, China responded by announcing a list of 128 US products as the targets of US retaliatory tariffs (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang and Hart2018). In the context of African countries, US protectionism in terms of reduction or removal of AGOA benefits have often been accompanied by removal of investment concessions or provision of investment concessions (mining and other natural resources) in favor of Chinese companies.

An important implication of the theory of dynamic industry preferences (one form of trade liberalization) is that trade preferences tend to reduce rather than increase industry demand for protection. This is partly a result of the dominance of large firms and changes in industry characteristics in terms of capital intensity and trade dependence. Over the last few decades, the number of small firms in footwear, apparel, and textiles in the US registered a substantial decline while the average size of big firms increased. Large firms in these industries tend to be capital-intensive and they support trade liberalization since this increases the price of their abundant factor resources (Hathaway, Reference Hathaway1998; Milner and Tingley, Reference Milner and Tingley2011). Such preferences also allow these firms to coordinate their global value chain activities in a way that enhances their competitive position. Such firms will gain rather than lose from trade preferences.

3. Literature Review

A survey of the extant literature on the role of AGOA trade preference on beneficiary countries’ exports is limited and the findings are mixed. In general, the literature covers the following major areas: (a) the extent to which beneficiary countries use the preferences granted under AGOA (utilization rates), (b) the estimated impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports, (c) the role of trade preferences in increasing and diversifying beneficiary country exports, and (d) the role of trade preference regimes by other developed countries on beneficiary country exports such as the GSP and EU trade preference (EBA).

Keck and Lendle (Reference Keck and Lendle2012) examined the ratio of imports claiming AGOA preferences to imports eligible for AGOA preferences in 2008 and found that to be at 92%, which is higher than those of many free trade agreements (utilization rates). Using 2002 data, Brenton and Ikezuki (Reference Brenton and Ikezuki2004) show that while average utilization rates for AGOA were over 80% (comparable to EU preference programs), one-third of countries had rates below 20% and 37% of countries had rates greater than 80%. In agricultural product exports, 14 countries had utilization rates above 90% (AGOA/GSP) but two countries did not use preferences at all (Dean and Wainio, Reference Dean and Wainio2006).

Several empirical studies have examined the effects of AGOA on beneficiary country exports. In general, they show that AGOA's impact has been positive (but typically small) or insignificant. Significant and positive effects have, however, been registered at the sector and country-specific levels. Nouve (Reference Nouve2005) estimating the effects of AGOA on African exports using a dynamic panel analysis (1996–2004) found AGOA to have a positive and significant effect on beneficiary country exports to the US. He also found that there was a spillover effect of an additional $0.16 to $0.20 in overall exports to the US for every dollar increase in AGOA exports. Using a gravity model and exports at the HS 2-digit level for the period 1997–2001, Lederman and Ozden (Reference Lederman and Ozden2004) found that participation in the AGOA scheme led to 5% higher exports for the average beneficiary country. Using disaggregated export data (1998–2006), Frazer and Van Biesebroeck (Reference Frazer and Biesebroeck2010) found that AGOA had significant effects on exports of agricultural goods, manufactures, and apparel but not petroleum and minerals. Cooke (Reference Cooke2011), using different levels of product aggregation, found that AGOA led to increased exports of apparel and non-apparel products (effects higher for apparel than non-apparel products) and contributed to raising beneficiary country exports to the US by 38.3 to 57.8%, respectively. Yeboah et al. (Reference Yeboah, Shaik and Musah2021) evaluating the impact of AGOA on members’ agricultural exports show a significant growth in bulk commodity exports to the US (wheat, corn, oilseeds, cotton, pulses, tobacco etc.).

Didia et al. (Reference Didia, Nica and Yu2015) performed a cross-country analysis using ordinary lease squares (OLS) and the generalized methods of moments (GMM) estimation technique on aggregated data spanning 12 years and found a large, positive, and significant impact of AGOA on beneficiary exports. However, the authors found a disproportionate impact in favor of crude oil exports, which does not align with the intentions of the Act. A study comparing the relative impact of AGOA and the EBA (Everything but Arms program by Sorgho and Tharakan (Reference Sorgho and Tharakan2019) that allows duty and quota free access of exports from least developed countries to the EU) shows that during the 1996–2015 period, AGOA had a larger impact than EBA on beneficiary countries’ exports. The study underscores the adverse impact of stringent rules of origin and successive trade liberalization in advanced countries that is leading to the erosion of preferential benefits. Mahabir et al. (Reference Mahabir, Fan and Mullings2020) examining whether exports of apparel under AGOA crowds out EU-15's imports from SSA show the complementarity of African exports to the two markets and that every percentage growth in exports to the USA is associated with a less than proportionate increase in exports to the EU-15, indicating a higher utilization of the special waiver. A survey-based study by Karingi et al. (Reference Karingi, Páez and Degefa2012) also found that a majority of private sector respondents believed that AGOA was critical for their exports and economic relations while a quarter of the respondents stated that AGOA was not important.

A few studies found that AGOA was not responsible for increased exports from beneficiary countries to the US. Zappile (Reference Zappile2011) using export data from 1995 to 2005 found no significant effect of AGOA on total nonoil exports. Using a gravity model on export data from 1997 to 2004, Seyoum (Reference Seyoum2007) found no link between AGOA and total exports (significant effects were found for certain sectors such as textiles and apparel). Similarly, Tadesse and Fayissa (Reference Tadesse and Fayissa2008) using aggregate trade data for 1991–2006 found no significant effect of AGOA on total beneficiary country exports. However, they found significant effects of AGOA in 19 of 99 product categories such as vegetables, fruits and nuts, beverages, plastics, tea, spices, fabrics, apparel, and tin. A recent study by Moyo et al. (Reference Moyo, Nchake and Chiripanhura2018) using several variants of propensity score matching techniques show that the impact of AGOA on SSA exports is generally negative and statistically significant. Cooke and Jones (Reference Cooke and Jones2015) found that AGOA contributes to export diversification in Sub-Saharan Africa and state evidence from the economic development literature that relates greater export diversification to high per capita income. In their subsequent study, Cooke and Jones (Reference Cooke and Jones2020) found that after an initial period of adjustment, AGOA eligibility is associated with significantly higher rates of future per capita GDP growth in eligible countries (not necessarily immediately or permanently).

A study on continental developments (Africa Research Bulletin, 2019) states that AGOA has not been the game-changer it was hoped for because it did not lead to large volumes of trade in terms of SSA's exports to the US market and export diversification. The volume of AGOA trade remains modest. For example, exports of clothing from beneficiary countries are estimated at about one billion USD amounting to just 1% of all US clothing imports in 2019. Petroleum exports continues to dominate and Africa attracts only about 1% of all US foreign investment. The challenge is to attract foreign direct investment into beneficiary countries that produce manufactured goods for the US market. The generous rules of origin are expected to stimulate the establishment of light manufacturing and alleviate the lack of sophistication in their exports (Fabricius, Reference Fabricius2016). The generous rules of origin have allowed Southeast Asian firms to use beneficiary countries as a trade corridor to reach the US market, i.e., they can source as many garments as they wish from overseas and re-export them to the US (Thomas, Reference Thomas2017). Chinese textile firms in many parts of Africa, for example, have used the opportunities afforded by AGOA to export to the US while also creating jobs and transferring manufacturing know-how technology. US tariff reductions under AGOA have also benefitted US bulk buyers.

Some of the studies cover a relatively short period following the implementation of AGOA thus picking up only its short-term effects while a few other studies were limited by the small number of products covered in the study.

4. Hypotheses Development

There are internal and external barriers that discourage African firms from initiating and/ or expanding exports. They range from information barriers, functional barriers (knowledge, information), product or marketing barriers (product quality, packaging, distribution) to complex political systems, uncertain political environment, and patronage networks (Rutihinda, Reference Rutihinda2008; Lakew and Chiloane-Tsoka, Reference Lakew and Tsoka2015).

Even though African economies are characterized by an institutional framework where relation-based governance may be more important than rule based formal system, firms’ control and coordination strategies differ reflecting the within country variations in these countries. The institutional framework within which firms operate has an important role in influencing the transaction costs of production and market exchange. As multinational firms operate in different countries, such differences in the institutional environment could have implications on inter-firm collaboration which in turn influences performance outcomes (Singh, Reference Singh2012). The central premise of our model is that there are factors that moderate the relationship between trade preferences (AGOA) and export performance. We believe that export performance cannot be solely determined by conventional factors such as exchange rates or the availability of trade preferences. Further explanations shift away from pure trade concessions and explore an interdisciplinary approach to determine additional factors that moderate the relationship between AGOA trade preference and export performance of beneficiary countries. The quality of a countries’ domestic legal institutions has a significant impact on the coordination and overall transaction costs of firms and indirectly affects the volume of a country's exports. It is also important to underscore the role of inward FDI in enhancing skills development, upgrading domestic technological capabilities, and facilitating export-oriented production (USITC, 2014). Thus, the positive association between AGOA trade preference and beneficiary countries’ export performance becomes stronger with robust domestic legal institutions (rule of law) and inward FDI.

4.1 The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and Export Performance

Economic integration has had a spotty record as an economic policy strategy. In some developing countries, integration experiments (such as the East African Common Market, 1967–1977) failed partly because potential gains are looked at only in static terms such as growth in exports or imports based on preference margins (trade creation versus trade diversion) (Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Field and Cobb2010). Such gains are not always obvious because member countries often trade little with each other and are not large economically. There are also distribution and sovereignty issues. Success rests on the realization of dynamic gains from increased investment and new industries, skills development and upgrading of technological capabilities to serve the larger market. Unilateral preferences (trade preferences given by rich countries that are not reciprocated, i.e. African countries under AGOA are not expected to provide preferential trade benefits to US exports to their countries) such as AGOA improve economic efficiency by substituting lower cost production for higher cost production from the home country of foreign producers.

The implementation of AGOA and other trade agreements has stimulated the establishment of buyer-driven commodity chains that export products to developed country markets. Producers in these countries are engaged in contract manufacturing for global buyers such as Walmart and Gap in labor intensive export sectors. They often invest in production technology to meet the standards required by foreign buyers. Networking with major overseas buyers and their marketing and distribution channels has been critical in improving export performance.

Hypothesis 1: AGOA tariff preference (tariff concessions) has a positive effect on beneficiary country exports.

4.2 AGOA and Rule of Law: The Moderating Effects of Rule of Law

In order to promote national exports (especially global value chains (GVC) participation in industries that boost exports), it is important to improve the quality of domestic legal institutions. Domestic legal institutions help deepen GVC participation in industries that produce complex and customized products. A recent report (WTO, 2017) suggests that only six African countries reach or are above the rule of law index's global average.

The quality of institutions determines transaction and production costs for exporters (Li et al., Reference Li, Vertinsky and Zhang2013). Country level studies provide support that home country legal institutions play a significant role in facilitating a country's exports. Some of the studies show that domestic legal institutions explain patterns of a country's exports more than the level of physical capital and skilled labor combined (Nunn, Reference Nunn2007). In the context of this study, rule of law is used as a proxy for domestic legal institutions which refers to a system that is impartial, promotes transparency in business relationships and enforcement of contracts, as well as imposing penalties on illegal opportunistic behaviors (North, 1990).

Rule of law is critical for taking advantage of trade preferences to boost exports through GVCs or other domestic intermediaries. Transaction cost economics and contract theory provide explanations about the role of contracts in value chain activities (Eller and Salminen, Reference Eller and Salminen2020). They suggest the importance of complete contracts that specify rights and obligations and coordinate tasks and functions. Complete contracts also help reduce risk and uncertainty and enhance interfirm resource efficiency. Such actions, complemented by legally binding monitoring and enforcement practices, are likely to have a positive effect on overall firm performance. However, we know that contracts to guard against opportunism and supplier non-performance are incomplete. The best defense against such a potentially disruptive practice by unethical partners in the market is the integrity of the country's legal system. Thus, a country's governance structure is an important factor in enabling successful GVC participation of domestic firms. GVC requires intra- and inter-firm relations between agents located in different countries with heterogeneous legal systems. These relations may not be explicit or implicit and often remain incomplete. A country's rule of law could determine a firm's choice of location and sourcing of inputs (Taglioni and Winkler, Reference Taglioni and Winkler2016).

Extant research focuses primarily on the main effects of AGOA on export performance, largely ignoring the way certain moderators affect the AGOA–export performance relationship. Consistent with institutional theory, we suggest that rule of law may play an indirect role, enabling firms to exploit different resources that may have a positive effect on export performance. By reducing cronyism, corruption, and enhancing economic freedom, rule of law helps entrepreneurial firms exploit foreign market opportunities (made possible by AGOA) by aggressively seeking out foreign clients. Scholars observe that reducing bureaucratic hurdles in exporting countries in the form of arbitrary and restrictive rules of origin and certificates of direct shipment will enhance the positive impact of AGOA on beneficiary exports, i.e. reliable legal institutions exert a consistent positive effect on the utilization of tariff concessions to enhance export opportunities (Ritzel et al., Reference Ritzel, Kohler and Mann2018).

Hypothesis 2: Rule of law moderates the relationship between AGOA trade preference (tariff concessions) and beneficiary country exports such that the relationship becomes stronger as the rule of law increases.

4.3 AGOA and Foreign Direct Investment: The Moderating Roles of FDI

We argue that inward FDI will moderate the main effects of AGOA on export performance. FDI provides important assets for export-oriented production in technology-intensive products. It also plays an important role in primary product exports and has been a key source of new industrial technology for local exporters (UN, 2002). Such assets are firm-specific, costly, and difficult to acquire independently. Lavie and Miller (Reference Lavie and Miller2008) suggest that foreign partnering reduces cultural and institutional distance, creates familiarity and trust between the parties, and increases organizational adaptation resulting in an enhanced performance trajectory (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Moderating effects of Rule of law and inward FDI on the AGOA–export relationship. (a) Main Effects: Effect of AGOA (AGOA tariff concessions) on beneficiary country exports to the US; (b) Moderating effects: Moderating effects of rule of law and inward FDI on the relationship between AGOA (AGOA tariff concessions) and beneficiary exports to the US.

AGOA is likely to attract export-oriented FDI (that targets the US market) from the EU, Japan, and other advanced countries. For example, FDI from the EU countries to SSA has increased during the AGOA period (projects in auto industry, chemicals, and a wide variety of industries have gone up). Furthermore, existing trade friction between the EU and US is likely to lead to more export-oriented EU FDI in SSA to take advantage of the US market.

We suggest that FDI also plays an indirect role enabling local firms to increase exports by leveraging new market opportunities facilitated by AGOA. Dynamic effects of preferences arise from skills development, upgrading of technological capabilities, and the establishment of viable, international competitive industries. It also leads to diversification horizontally into new products and markets or vertically into greater domestic value addition (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Jauch and Traub-Merz2006). Trade preferences provide a basis for the development of competitive export industries, which is often achieved by attracting export oriented FDI. A USITC report (USITC, 2014) found that AGOA had a positive impact on FDI flows, particularly in the textiles and apparel sector in Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, and Swaziland, and also in South Africa's automotive industry. Besides FDI's direct effects on exports, prior studies support a positive moderating role for FDI in the relationship between AGOA and export performance (USITC, 2014). Based on the above discussion, we propose the following moderation hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Foreign direct investment moderates the relationship between AGOA trade preferences (tariff concessions) and beneficiary country exports such that the relationship becomes stronger as foreign direct investment increases.

5. Data and Methodology

To determine the impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports, we examine annual exports to the US market between 1989 and 2015 using US import data from 38 Sub-Saharan Africa countries (only 33 countries have been members throughout the period). The list of beneficiary countries as of 2018 is listed in Appendix 1.

Panel data are used to test the hypotheses. We have unbalanced panel data due to missing observations. One advantage of using panel data is that it offers a solution to the problem of bias caused by unobserved heterogeneity, a common problem in the fitting of models with cross-sectional data (Dougherty, Reference Dougherty2016). It also allows for regression analysis with both spatial (such as countries or firms) and temporal dimension (time span). We use the fixed effects approach to examine the effects of AGOA over time.

The equations for analyzing the interactions are indicated as follows:

Model 1: Yipt = B 0 + B 1Xit + B 2W1it + B 3W2it + B 4 (Xit*W1it) + B 5 (X1it*W2it) + B 6 Cit + Eipt

Model 2: Yipt = B 0 + B 1Xipt + B 2W1it + B 3 W2it + B 4 (Xipt*W1it) + B 5 (Xipt*W2it) + B 6Cit + Eipt

where:

Yipt = AGOA beneficiary country (i) exports of product (p) to the US in years (t) = 1989–2015 (variable in log).

Xit = AGOA beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015. Zero if not AGOA beneficiary and 1 if beneficiary.

Xipt = Tariff concessions for beneficiary country (i) for product (P) in years (t) = 1989–2015 (variable in log).

W1it = Rule of law in beneficiary country (i)in years (t) = 1989–2015.

W2it = Inward FDI from the rest of the world to beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015 (variable in log)

Xit * W1it = Interaction term between AGOA beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015 and rule of law in beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015.

Xit * W2it = Interaction term between AGOA beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015 and inward FDI in beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015

Xipt * W1it = Interaction term between tariff concessions for beneficiary country (i) for product (p) in years (t) = 1989–2015 and rule of law in beneficiary in years (t) = 1989–2015.

Xipt * W2it = Interaction term between tariff concessions for beneficiary country (i) for product (p) in years (t) = 1989–2015 and inward FDI in beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015

Cit = controls (time and cost of starting a business; time to register a property; cost to export; cost to enforce contracts; time to import goods; exchange rate; US GDPPC) for beneficiary country (i) in years (t) = 1989–2015.

Eipt = sample error term. B 0 = intercept. B 1-6 = coefficients of the parameter estimates.

Two versions of the above equation are estimated, i.e., one for AGOA and another for AGOA tariff concessions. Exports are estimated at the product level for beneficiary countries. Tariff concessions take the value of 0 for countries that are not AGOA beneficiaries.

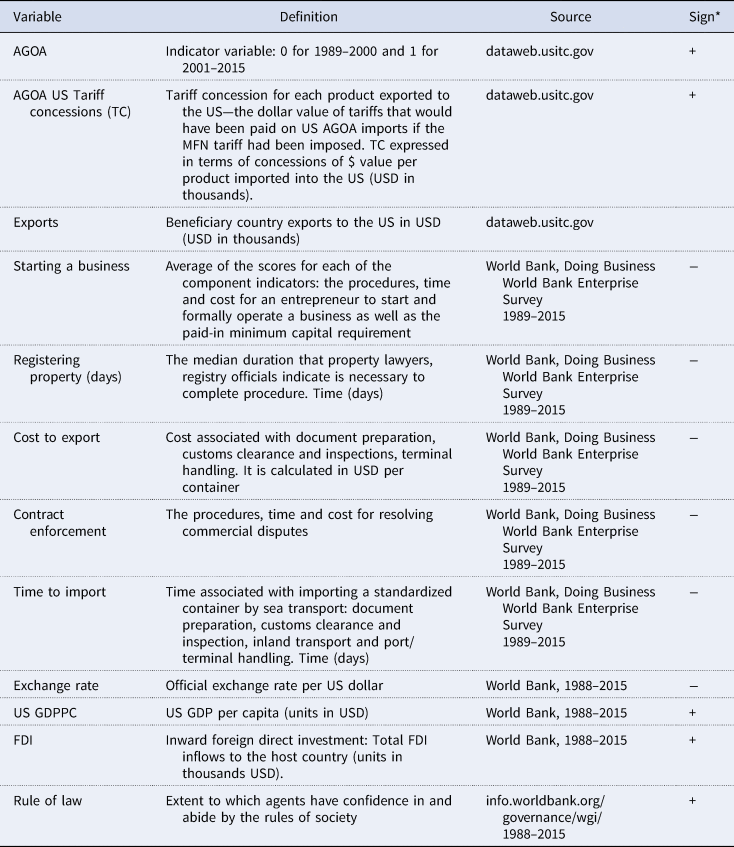

The dependent variable used in the analysis is the natural log of Sub-Saharan Africa exports (38 beneficiary countries) to the US for the period 1989–2015. Data were drawn from US International Trade Commission (http://dataweb.usitc.gov). Table 1 summarizes the variables, measures and sources of data.

Table 1. Variables, measures and sources

Sign*: Expected sign.

The independent variables of interest are AGOA and AGOA tariff concessions. To test our hypothesis related to the impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports, we expanded our sample to include a few countries that were on and off the beneficiary country list. As the AGOA indicators, 1 is assigned to country beneficiaries and 0 to countries that were not beneficiaries, i.e., beneficiary exports before AGOA as well as non-beneficiary country exports to the US before and after AGOA. Even after the implementation of AGOA in 2001, some countries that were beneficiaries were taken off the list for human rights violations and other reasons while some others were put back on the list as things improved.

All eligible products under AGOA enter duty free into the US market. We calculate AGOA tariff concessions as the import duty that would have been paid in the absence of AGOA. For each product, the tariff concession is thus the MFN duty rate multiplied by the total value of imports. MFN duty rates are tariff rates that countries agree to impose on imports from other members of the WTO (unless that country is a member of a preferential trade agreement). MFN duty rates are the highest rates that WTO members charge one another. The data exclude imports under the generalized system of preferences.

5.1 Control Variables

We controlled for several variables reflecting the determinants of trade flows suggested in the literature.

5.1.1 Starting a Business

The costs of starting and operating an export business can be costly and time consuming. The regulations and documentation requirements in many countries are often quite complex and capital is often tied up before a reasonable level of profit is realized. Chaney (Reference Chaney2016) states that firms defray a fixed entry cost to enter a foreign market and that liquidity constraints can be a major obstacle to accessing a foreign market. He suggests that in the face of such liquidity constraints, only wealthier firms or firms with sufficient domestic sales are able to export. We believe that the time and cost involved in entering a foreign market has a negative effect on exports. This variable is measured on the mean of the scores of the procedures, time and cost for an entrepreneur to start and formally operate a business, as well as the paid-in minimum capital requirement (Table 1).

5.1.2 Registering Property

The second variable deals with registration of property and used as a proxy for protection of property rights. Weak property rights lead to decreased vertical integration, less specialization in production organization, and increased transaction costs (Ferguson and Formai, Reference Ferguson and Formai2009). The absence of effective property rights also hinders the formation and development of vertically integrated firms and collaborative clusters capable of producing more sophisticated goods for exports. Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Qu and Zhang2012) find that stronger property rights facilitate greater exports of goods from complex industries. This variable is measured on the median duration that property lawyers, registry officials, indicate is necessary to complete a given procedure (Table 1).

5.1.3 Cost to Export

The high price of goods due to high export costs impedes the ability of consumers to buy imported goods. Producers would also not be able to procure high-quality foreign inputs (Mussa and Ramakrishna, Reference Mussa and Ramakrishna2018; Portugal-Perez and Wilson, Reference Portugal-Perez and Wilson2008). Various studies show that the reduction in trade costs leads to increased exports. Khan and Kalirajan (Reference Khan and Kalirajan2011) suggest that the growth of Pakistani exports during the 1994–2004 period was attributed to the reduction in trade costs in neighboring countries. Similarly, Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Eaton, Jensen and Kortum2003) observed that US manufacturing industries that experience large declines in trade costs showed relatively strong productivity growth and the tendency to export. Export cost is all cost associated with exporting a standardized cargo by sea transport through four defined stages: document preparation, customs clearance, inland transport handling, and port and terminal handling (Table 1).

5.1.4 Contract Enforcement

Poor contract enforcement can constitute an additional cost to exports and reduces the volume of trade (Olson, Reference Olson1996; Francois and Manchin, Reference Francois and Manchin2013). Nunn (Reference Nunn2007) finds that contract enforcement explains international trade patterns more than country endowments and labor combined. Krishna and Levchenko (Reference Krishna and Levchenko2013) also find that countries produce fewer complex goods partly due to less rigorous contract enforcement. Courts often violate the rights of foreigners as they are biased in favor of their own nationals (Ranjan and Lee, Reference Ranjan and Lee2007; Dixit, Reference Dixit2009). As contracts are less likely to be enforced, parties have the incentive to violate the terms of their own contract (Assche and Schwartz, Reference Assche and Schwartz2013). Contract enforcement, for example, can take less than 10 months in New Zealand and Norway while it can take about four years in Bangladesh. The variable is measured on the mean scores of the component indicators: the time, procedures, and cost of resolving a commercial dispute (Table 1).

5.1.5 Time to Import

In modern supply chains, the efficiency of one stage of the supply chain has ramifications on production outcomes in subsequent stages. The efficiency of the import process (days to import) largely depends on the efficiency of cargo handling at ports and the customs clearance process. Long delays in import processing impedes producers’ ability to obtain needed inputs for production. Furthermore, importers have to pay extra storage charges if the process takes time. Using highly disaggregated customs data from Thailand (2007–2011), Hayakawa et al. (Reference Hayakawa, Laksanapanyakul and Taiyo Yoshim2019) show that delays in customs processing reduces the frequency of export shipments, exports per shipment, and thus total exports. Several other studies also show that longer customs clearance time was associated with negative effects on exports (Carballo et al., Reference Carballo, Graziano, Schaur and Martincus2014; Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Hillberry and Alcantara2015). Time to import is measured on the number of days it takes to import a standardized container by sea transport (Table 1).

5.1.6 Exchange Rates

Low exchange rates tend to have a positive effect on export competitiveness in price sensitive segments and industries (Warner and Kreinin, Reference Warner and Kreinin1983). It is well recognized in the economic literature that a strong currency can have an adverse effect on exports and renders imports less expensive. Changing currency values alter relative prices and costs that either simulate or dampens international transactions in goods and services. It is based on official exchange rates per US dollar.

5.1.7 Importer Country GDP per Capita

A review of the literature supports the notion that importer GDP significantly influences bilateral trade flows. Large import markets such as the EU or US enable exporters to achieve economies of scale. AGOA has been quite an attractive opportunity for African countries because it allows firms duty free access to a large market with high-income consumers (high per capita GDP). A study by Roy and Rayhan (Reference Roy and Rayhan2011) examining the determinants of trade flows in Bangladesh demonstrates the important role of importer GDP. Similar studies on Namibia also show that increases in the country's exports are influenced by importers’ GDP (Eita and Jordaan, Reference Eita and Jordaan2008; Tumwebaze and Nahamya, Reference Tumwebaze and Nahamya2015). Importer GDP is measured by per capita GDP (US GDP per capita).

6. Results

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviation, and correlation matrix for the variables in the study. The result largely supports the hypotheses that the variables in the study are related to exports to the US. It strongly suggests that AGOA and AGOA tariff concessions can have an influence on beneficiary country exports. The AGOA and AGOA tariff concessions (TC) variables have a correlation of 0.63 (p < 0.01), 0.87 (<0.01), respectively, suggesting a strong positive association with the dependent variable. Similarly, the other independent variables show varying levels of association with the dependent variable. The variance inflation factors for the regression analysis on AGOA range from 1 to 2.96 and for tariff concessions range from 1 to 3.05, indicating no serious problems with multicollinearity (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Note: TC: Tariff concessions; STB: Starting a business (time/cost); TR: Time to register; CE: Cost to export; CEC: Cost to enforce contracts; TIG: Time to import goods; ER: Exchange rate; Law: Rule of law. Rule of law: Min: −2.23, Max: 0.856 and Number of observations: 13,026.

Correlations cannot be computed because one of the variables is constant.

*<0.10; **<0.05; ***<0.01.

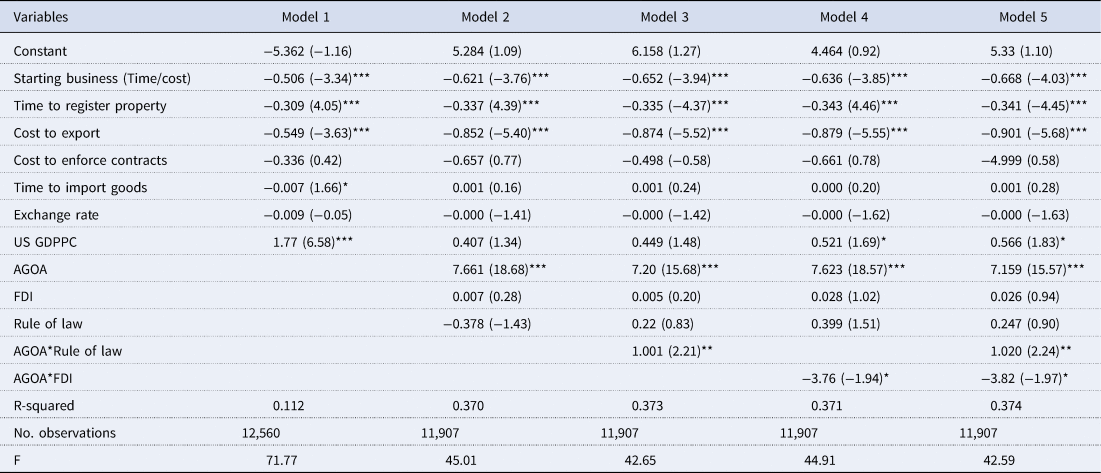

We conducted regression analysis to test our hypotheses. We use fixed effects regression based on the assumption that year-to-year variations in exports are random. A five-step regression model was used to assess the effects of AGOA and AGOA tariff concessions, respectively. Control variables were entered first. AGOA (AGOA tariff concessions), the two moderators (FDI and rule of law) were included as independent variables in the second step. Finally, the interaction terms between AGOA (AGOA tariff concessions) and moderators were entered separately in steps 3 and 4. The last step (Model 5) includes all the variables, including the moderators and interaction terms. The results of our findings are reported in Tables 3–5.

Table 3. Regression analysis of the impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports Fixed effects panel regression (Country/time fixed effects)

Note: Unstandardized beta and (t-statistics) reported in parentheses for fixed effects model.

*<0.10, **<0.05, ***<0.01

6.1 Direct Effects

The results show that when only the main effects are examined, AGOA (Table 3: model 2: t = 18.68; model 3: t = 15.68, p < 0.01; model 4: t = 18.57, p < 0.01) and AGOA tariff concessions (TC) (Table 4: model 2: t = 18.98; model 3: t = 19.40, p < 0.01; model 4: t = 17.35, p < 0.01) have a positive and significant effect on beneficiary country exports. Thus, hypothesis 1 is strongly supported. This finding supports the role of preferential market access in increasing beneficiary country exports. The estimated coefficient for AGOA is b = 7.661, t-value = 18.68, p-value < 0.001 and AGOA tariff concessions is b = 0.004, t-value = 18.98, p-value < 0.001. The unstandardized coefficients for the independent variables (AGOA and AGOA tariff concessions) show that as AGOA (AGOA tariff concessions) increase by one unit, beneficiary country exports increase by 7.661 (0.004) units, respectively. This could be attributed to lower tariffs and nontariff barriers in preference granting countries as well as higher preferential margins vis-à-vis foreign competitors. The result is consistent with previous empirical findings on the role of AGOA in increasing beneficiary country exports (Lederman and Ozden, Reference Lederman and Ozden2004; Nouve, Reference Nouve2005).

Table 4. Regression analysis of the impact of AGOA tariff concessions on beneficiary country exports Fixed effects panel regression (Country/time fixed effects)

Note: Unstandardized beta and (t-statistics) reported in parentheses for fixed effects model.

*<0.10, **<0.05, ***<0.01.

The rule of law variable is positive and significant for some models (Table 4 (AGOA tariff concessions): model 3: t = 8.15, p < 0.01; model 5: t = 5.25, p < 0.01). Even though a conducive regulatory climate is good for promoting exports, raw materials exports have often been made from politically unstable countries underscoring the fact that raw resource exports do not require the existence of robust governance mechanisms. Norman (Reference Norman2009) finds that resource exports are not associated with rule of law. However, as countries embark on national plans to increase their AGOA utilization rates by increasing manufactured goods exports (through participation in GVCs), rule of law will become more significant. It is important to have a legally binding and enforcement regime to govern the diverse intra and inter-firm relations to guard against opportunism and supplier non-performance.

This is supported by previous studies that show that the quality of domestic legal institutions (rule of law) matter for export performance (Berkowitz et al., Reference Berkowitz, Moenius and Pistor2006; Li et al., Reference Li, Vertinsky and Zhang2013). A recent World Bank study (World Bank, 2018) indicates that many African countries experience declines in regulatory quality and control of corruption suggesting that governance and strong legal institutions are still a concern in the region and pose serious challenges for businesses in promoting exports.

The evidence on the role of FDI in stimulating African exports is not conclusive. FDI is significant only for Table 4: (AGOA tariff concessions)-model 2: t = 1.81, p < 0.10; model 4: t = −26.21, p < .01. Even though the role of inward FDI in stimulating exports has been sufficiently underscored in the literature (UN, 2002; Grandinetti and Mason, Reference Grandinetti and Mason2012), its role in the context of African exports appears to be statistically insignificant or negative (except for model 2 in Table 4: t = 1.81, p < 0.10). FDI could potentially have a negative effect on a country's exports if (a) the technology transferred is low level, (b) it inhibits the growth of domestic exporters, or (c) the investment only targets the domestic market (Whiteaker, Reference Whiteaker2020). Except in a few sectors such as textiles and apparel, most of the FDI is in services (financial, information, and transportation) that do not generate exports. Some of the investments (food, beverages, alternative energy) were intended to access Africa's markets (market-seeking FDI) to satisfy domestic demand and were often import intensive. Mergers and acquisitions over the last few years may have also resulted in the acquisition of domestic exporting firms. EU countries are the major trading partners and largest source of FDI to SSA. In 2018, for example, total trade in goods between EU member states and SSA was worth 235 billion euros (more than 30% of Africa's total) compared to 46 billion euros for the US. Only 6% of Africa's exports go to the US compared to about 34% for the EU (European Union, 2020). Given the large percentage of European FDI in these countries, it is possible that exports are targeted to the European (not the US) market., i.e., increasing FDI into the continent is not associated with increased exports to the US. This matter needs further investigation.

6.2 Moderating Effects

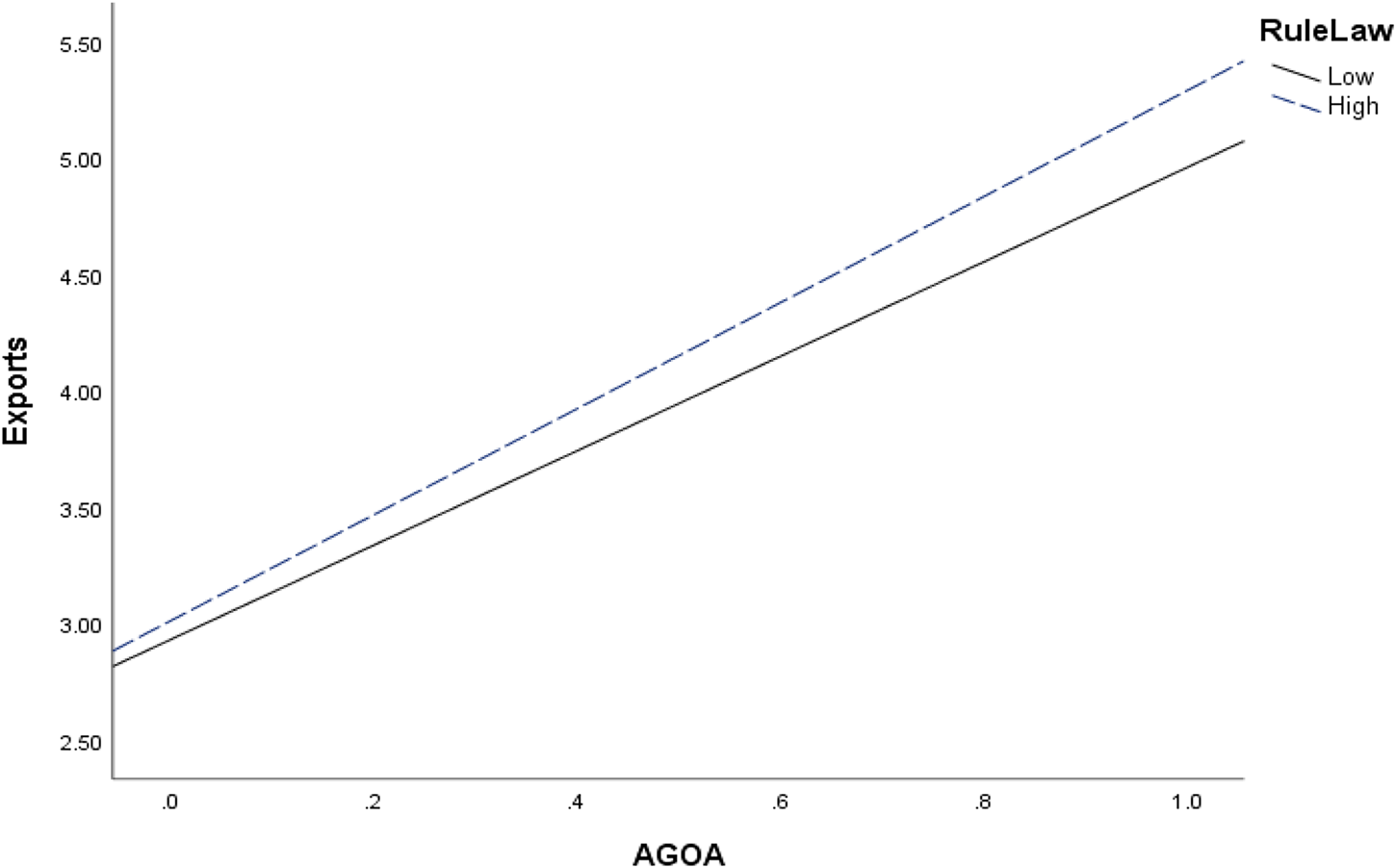

Our important contribution results from our investigation of the interplay between AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions and two moderators (rule of law and inward FDI) and particularly the contingent nature of the AGOA–export performance relationship. In the case of the first moderator, hypothesis (H2) predicted that rule of law moderates the relationship between AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions and export performance. Thus, it was confirmed by the significant moderating effect of rule of law on the relationship between AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions and export performance (Model 3, Tables 3 and 4). The positive effect of AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions on export performance becomes stronger in an environment of robust of law (Table 3, model 3 (AGOA): t = 2.21, p < 0.05; Table 4 (AGOA tariff concessions) t = 15.10, p < 0.01). This finding is in line with previous studies which show that robust rule of law will create certainty, predictability, and security, but will also restrict discretionary power of public officials which, in turn, will enhance the effective utilization of trade preferences and enhance exports (Ritzel et al., Reference Ritzel, Kohler and Mann2018). In short, the robust rule of law will enhance the positive impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports.

Regarding FDI (the second moderator), hypothesis (H3), predicting a moderating effect of FDI on the AGOA–export performance relationship, was also found to be supported. The results show that the positive effect of AGOA/AGOA tariff concessions on beneficiary country exports is weaker, as inward FDI increases showing the limited impact of AGOA on beneficiary country exports ((Table 3: model 4: t = −1.94, p < 0.10; Table 4: t = −42.03, p < 0.01). Increasing FDI in beneficiary countries does not appear to have stimulated production to take advantage of new market opportunities. This finding is in line with previous studies which show that most of the inward FDI is in infrastructure and services such as banking and transportation which do not generate exports. Other investments in energy, food, and beverages are also intended to access beneficiary country domestic markets and not are intended for exports (USITC, 2014; UNECA, 2017).

Many African countries have embarked on investing substantial resources in infrastructure development (education, health, reliable communications systems, sanitation, and affordable housing) to reduce poverty and attain sustainable economic development. For example, financial commitments for building the African infrastructure were estimated at over 100 billion USD in 2018 (OECD, 2017). These investments are not only import-intensive but also divert substantial resources from export sectors to non-exporting sectors.

The slopes (Figures 2 and 3) linking independent variables (AGOA) and exports are positive for high levels of both moderators. (a) At higher levels of AGOA, tariff concessions exports will be greater for countries with higher levels of rule of law; (b) At higher levels of AGOA tariff concessions, the level of exports will be weaker for countries with higher levels of FDI. At lower levels of tariff concessions, exports appear to be greater for countries with higher levels of inward FDI. This may be during the earlier phase of AGOA (when tariff concessions were not expanded in certain areas) when foreign firms primarily invested in and exported natural resources to the US market (resource-seeking FDI).

Figure 2. Moderating role of Rule of law. Beneficiary country exports (vertical axis); AGOA tariff concessions (horizontal axis). It shows that (a) the higher the tariff concessions, the higher the level of beneficiary country exports; (b) at higher levels of tariff concessions, exports to the US are greater for countries with higher levels of rule of law.

Figure 3. Moderating role of FDI. Beneficiary country exports (vertical axis); AGOA tariff concessions (horizontal axis). It shows that (a) the higher the tariff concessions, the higher the level of beneficiary country exports; (b) at higher levels of tariff concessions, exports to the US are greater for countries with lower levels of inward FDI. At lower levels of tariff concessions, exports to the US are greater for countries with higher levels of inward FDI.

A paired samples t-test is used to compare the means of beneficiary country exports (ten years before and ten years after AGOA) in major product categories using the harmonized tariff classification. This test determines whether there is a statistical difference between the paired means before and after AGOA. The table only shows product categories where there is a statistically significant difference. Table 5 provides the mean, standard deviation, and p-value for selected product groups from beneficiary countries. A significant increase in exports occurred in several product categories such as live animals, cereals, works of art, and leather products.

Table 5. Results of paired sample t-test: Selected product groups

Note: Before AGOA (beneficiary country exports for ten years before AGOA): 1992–2001.

After AGOA (beneficiary country exports for ten years after AGOA): 2002–2011.

*Number of pairs signifies pre-post analysis of mean values of product groups ten years before and ten years after AGOA.

*P-value <0.10; **P value <0.05; ***P value <0.01; SD: standard deviation.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

Preferential trade arrangements in favor of developing countries have been an important part of US trade policy for many decades. One of these preferential schemes is the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). AGOA was implemented in 2001 and provides preferential duty-free access to numerous products exported from designated African countries. An important aspect of this scheme is its non-reciprocity and unilateralism. The arrangement does not require reciprocal trade concessions from AGOA countries in exchange for the preferential treatment provided for their exports.

The study shows that AGOA as well as AGOA tariff concessions have a positive and significant effect on beneficiary exports. This finding is consistent with the data on US imports under AGOA. Beneficiary country exports under AGOA increased from US $7.6 billion in 2001 to US $24.9 billion in 2017 (USTR, 2018). During the same period, non-oil related exports rose from US $1 billion to US $4.3 billion. Exports of manufactured goods such as chemicals, electronics, machinery, transportation equipment, and other manufactured goods have experienced the largest growth after crude petroleum, increasing from US$0.2 billion in 2001 to over US$2 billion in 2017 (USTR, 2018).

It also shows the role of two important variables: rule of law and foreign direct investment in moderating the relationship between AGOA and beneficiary country exports. The study reveals that tariff waivers cannot be a substitute for policy or institutional reforms such as rule of law. The moderating role of FDI is negative and significant. This demonstrates that the positive relationship between AGOA and beneficiary exports is weaker under higher levels of FDI. However, its role in generating exports will hopefully increase in future as countries improve their business climate and encourage export-oriented FDI partly through linkages to global buyer or supplier driven value chains.

Foreign direct investment remained stable at about 2% of Sub-Saharan Africa GDP and reached about US $66 billion in 2016, an almost sevenfold increase in a decade (UN ECA, 2017). FDI flows to diversified exporters such as Ethiopia have been more resilient than for the economies dominated by primary product exports. There are concerted efforts to increase Africa's manufacturing output by diversifying the region's export base with increased value-added activities (FDI inflows) through closer engagement with advanced and emerging economies.

The European Union countries have remained the leading source of FDI to SSA. In 2018, for example, EU investment in SSA was estimated at 25 billion USD (accounting for about 70% of overall FDI to SSA) compared to 10 billion USD for the US. EU FDI in these countries that targets exports to the US market is likely to increase in the coming years due to a number of factors. First, the trade tension between the US and EU has escalated over the last few years. In 2018, the US imposed tariffs on EU exports of steel, aluminum, auto and auto parts on national security grounds. The EU retaliated by applying retaliatory tariffs on about $3 billion of US exports to the EU ranging from steel, whisky to motorcycles. EU MNCs could invest in SSA (especially in industries that are subject to US trade restrictions such as steel or auto parts) to take advantage of export opportunities in the US market. Secondly, special economic zones which have opened in many SSA countries (to allow for duty free entry of foreign inputs for eventual exports) as well as the ratification of the African continental free trade agreement in May, 2019 could have positive effects on FDI, especially in manufacturing and services. Foreign investors from the EU, Japan and other countries will target the market of 1.2 billion people with a combined GDP of more than 2.2 trillion. They are also likely to take advantage of AGOA to target the US market. At present, it appears that increasing levels of EU FDI into SS Africa appears to be focused on exporting to the EU market.

7.1 Practical Implications

The study shows that AGOA has had a positive and significant effect on beneficiary country exports. Much of the export is concentrated in the area of primary goods and light manufactures with low barriers to entry (Table 5). AGOA provides a form of industry protection in US export market.

It is important to note that US tariffs are generally low and most imports by value enter duty free under the WTO and bilateral/regional trade arrangements. Overall, US trade-weighted tariffs average about 1.7% in 2018. Overall, the importance of preferences in providing a competitive advantage for Africa's exporters is going to diminish over time. Preferences are thus an opportunity not a substitute for more comprehensive industrial strategies that enhance domestic capabilities. Product categories (Table 5) where exports have grown reveals that beneficiary countries do not have viable international competitive industries. Existing small scale industries may not survive without preferences. Beneficiary countries need to effectively address impediments to trade and investments to enable firms to become more competitive. This includes complementary policies such as implementation of a conducive regulatory regime for businesses, improvement in education and public infrastructure as well as lower costs and reduced times for exporting and importing of goods and services. For example, the World Bank estimates the costs of border and document compliance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique at US $3823 and US$1037, respectively per container compared for Malaysia at US $366 or Indonesia at US $424 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.IMP.CSBC.CD). Such costs are likely to nullify the AGOA advantages that accrue to these countries.

Firms in beneficiary countries need to enhance their competitive advantage in different ways. This includes, but is not limited to, developing new capabilities by investing in modern production methods and marketing through licensing, joint ventures, and other forms of collaboration with foreign firms. They also need to diversify into higher value-added goods and upgrade the skills of the workforce. Exporting has benefits beyond increasing market share. Competing in foreign markets facilitates access to foreign markets as well as technological information that can enhance the firm's innovation potential (Alvarez and Robertson, Reference Alvarez and Robertson2004). Other internal impediments to exporting such as information barriers (lack of knowledge about export markets, export assistance), market related barriers (access to distribution channels, matching competitor's prices, promotion, provision of technical and after sales service), financial and managerial (trained and capable management) barriers need to be sufficiently addressed to increase firm exports (Lakew and Chiloane-Tsoka, Reference Lakew and Tsoka2015).

AGOA will expire in 2025 and some countries have already started to lobby the US government for its extension. Many countries believe that it has contributed in expanding beneficiary country exports and has created certainty and predictability for US buyers and investors. Maliszewska et al. (Reference Maliszewska, Engel, Arenas and Kotschwar2018), for example, show that Lesotho could sustain a 1% loss in income by 2020 and a 16% decline in exports of textile and apparel if AGOA is terminated. Given US policy (African countries’ preference) to promote economic development of poor countries through trade (not aid), the question is not whether AGOA will be terminated but what form it is likely to take. The global trade environment is changing, most notably the EU's preference trade agreement with African, Caribbean & Pacific (ACP) countries. The new arrangement (economic partnership agreements) represents a transition from a non-reciprocal regime under the Lome Convention into a partnership model based on reciprocal market access under the umbrella of the Cotonou agreement (2003). The EU Commission has so far negotiated such partnership agreements with 16 African countries thus providing EU firms preferential access to African markets. There are concerns that such agreements place US firms at a disadvantage while AGOA provides access to the US market without any such reciprocity for US firms.

Africa's concerns with reciprocal agreements are likely to be tariff reductions and loss of government revenues, the adverse impact they may have on local producers and their potential threat to African regional integration efforts. However, recent studies show that non-reciprocal trade agreements (i) reduce the pressure for trade liberalization, thus undermining internal policy reforms that may promote faster expansion of trade; (ii) divert trade from efficient producers and come at the expense of other countries; and (iii) they can be revoked by a donor at short notice without any right of appeal (Grant and Lambert, Reference Grant and Lambert2008). Admassu (Reference Admassu2020) shows that African reciprocal trade agreements perform better than non-reciprocal agreements in promoting exports and imports, underscoring the importance of deepening and widening trade agreements to foster more trade in Africa.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

The fast-changing business environment requires a greater understanding of the factors that enhance exports of African countries beyond AGOA. Despite the implementation of AGOA, the export sector in these countries remains undeveloped. Future research can chart important avenues to increase African exports. More research can also be undertaken to study the nexus between FDI and exports in the context of these countries. Future research can also examine exports and FDI at a more disaggregated level to reach a full understanding of these relationships as well as cultural barriers to exports.

Appendix 1. AGOA Beneficiaries, 2018