The World Trade Organization (WTO), according to all who have served as Director-General (D-G), seeks to achieve universal membership.Footnote 1 It has, as of late 2008, 153 members, representing approximately 91% of the world's population, 98% of world GDP, and 96% of world trade. Twenty-five of these countries have joined the organization through a formal accession process since it was founded in 1995. And yet there are still 26 other countries, with a total population of 565 million, currently under review for accession, most prominently the Russian Federation. In addition, there are, by the author's count, 17 countries with a total population of 64 million that are neither members nor applicants for membership. Despite the broad current membership of the WTO, its accession process and accompanying negotiations have become increasingly lengthy and controversial. Some applicant countries complain that existing WTO members have attempted to impose terms upon them that go beyond the obligations of existing WTO members, while incumbent members complain that applicants do not move quickly enough to make their legislation and institutions comply with WTO rules. This paper sets out to examine the political economy of the WTO accession process, focusing on the time it has taken for the first 25 new WTO members to accede, as well as the terms of their accession.Footnote 2

The paper is organized as follows. The analysis begins with a review of the benefits of WTO membership, and a review of members, recent accessions, observers, current applicants, and those outside the WTO system. There follows a historical discussion of the GATT system of accession, and how it accommodated countries under more lenient rules of participation. A review of the factors behind a growing interest in expanding the trading system leads to an account of the stricter WTO accession rules. An empirical study of the accessions since the founding of the WTO provides the basis for a discussion of factors that may be slowing the membership process. The paper concludes by taking stock of WTO accession practice, and offering recommendations for improving the process.

Overview of current WTO membership and accession

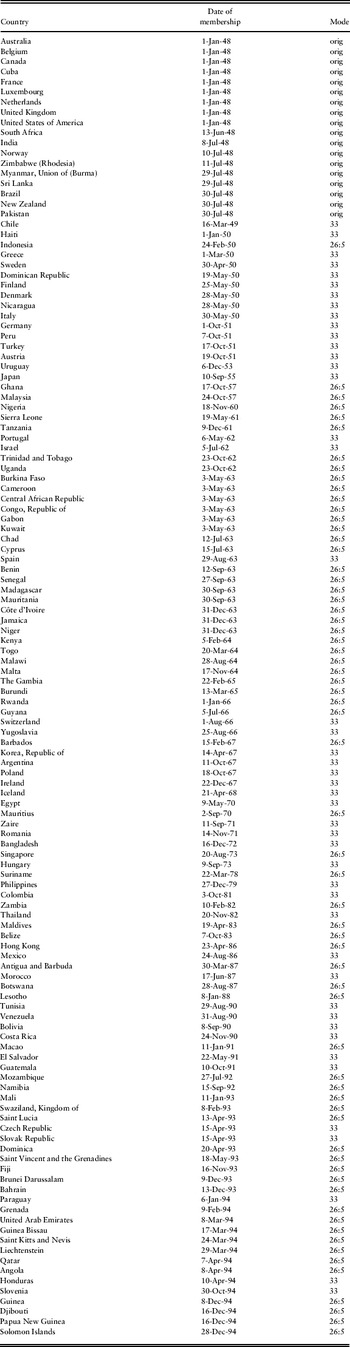

The WTO founding membership comprises the 128 Contracting Parties (CPs), as they were known, of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) at the end of 1994. These countries negotiated and ratified the Uruguay Round trade agreement, which created a new and more comprehensive trade organization, the WTO. The GATT had been founded in 1947 with 23 original CPs, as a vestige of the Havana Charter, which had intended to establish a comprehensive International Trade Organization. However, that proposal failed to receive adequate political support from the United States. GATT membership grew slowly at first, but expanded rapidly in the 1960s, as many newly independent countries joined, and surged again in the late 1980s and early 1990s, after the Uruguay Round was launched. Table 1A shows the GATT membership as it stood at the end of the Uruguay Round and founding of the WTO.Footnote 3

Table 1A. GATT CPs that became WTO founding members

Sources: Jackson (Reference Jackson1969), Appendix D, GATT Documents Database, Stanford University, various.

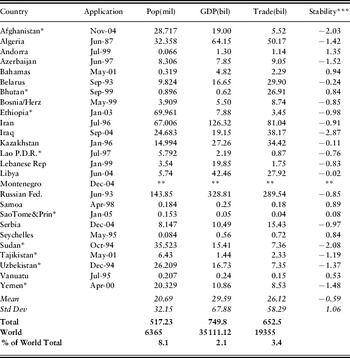

After its founding in 1995, several countries carried over their requests for GATT membership to the newly formed WTO, and others started application procedures only after the new organization came into existence. By late 2008, 25 countries had acceded to the WTO (Table 1B), bringing the membership to 153, while an additional 26 countries were in varying stages of the accession process (Table 2A). There were, finally, 17 countries listed as United Nations members that were not WTO member or applicant countries (Table 2B).

Table 1B. WTO accession countries (as of August 2008)

Notes: * least developed country (WTO list).

** World Bank Index of Political Stability, 2004–2007.

*** Average bound tariff for category.

Source: WTO (2005a), plus updates from WTO press releases (www.wto.org).

Table 2A. Countries in WTO accession negotiations (August 2008)

Notes: * denotes least-developed country (World Bank list lowest quartile: 2005 GNI per cap<$825).

** Montenegro data are included with Serbia's.

*** World Bank index of political stability, 2004.

Population, GDP, and trade figures are for 2004.

Sources: WTO (2005b) ; World Bank WDI database, World Bank Governance Index database.

Table 2B. Remaining countries not yet applying for WTO membership

Notes:* denotes least-developed country (World Bank list lowest quartile: 2005 GNI per cap<$825).

** trade figures not separable from France's.

*** trade figures not separable from Italy's.

Sources: UN Membership database, World Bank WDI database; World Bank Governance Index database.

Benefits of WTO membership

Countries will gain from trade through their own unilateral trade liberalization efforts, so it is not immediately evident that membership in the WTO adds to a member country's economic welfare.Footnote 4 However, the revealed preferences of 128 founding member countries, in addition to 25 new members and 26 applicants that have been willing to endure a lengthy accession process, show a strong perception among these countries that membership in the WTO system is beneficial. Its value in fact derives principally from the institutional elements of a rules-based organizational network. Despite the gains from unilateral free trade policies, most countries' governments find it difficult to overcome mercantilist tendencies, embedded in entrenched protectionist lobbying of import-competing industries, potential terms-of-trade gains from tariffs in large countries, and nationalist economic ideologies. WTO membership requires each member to commit to a set of trade policy rules regarding imports (principally MFN and national treatment), and to reciprocity in trade negotiations and orderly dispute settlement. These measures provide an external ‘anchor’ that helps to prevent submission to domestic protectionist interests. In addition, the commitment element of membership among a country's trading partners provides an important additional benefit by reducing the risk of arbitrary market access barriers or closure that each country's export and import sectors would otherwise face in international trade. This commitment in turn encourages domestic and foreign direct investments in trade-related activities. For many smaller countries, WTO market access rules are particularly important, since they would have great difficulty bargaining for such broad market access provisions on their own. An additional benefit for all members comes from the multilateral bargaining network of WTO negotiations, which tends to reduce the transaction costs of trade-opening agreements for each individual member.Footnote 5 Global trade liberalization would otherwise have to proceed on the basis of hundreds or thousands of bilateral or regional agreements, which would furthermore be likely to create conflict and discrimination in trade relations, and inefficiency in welfare.Footnote 6 Finally, the dispute resolution mechanism provides third-party adjudication of alleged rules violations, thereby protecting and securing members' negotiated gains from trade liberalization.

In summary, WTO membership makes it possible for its members to gain from trade through its ability to improve market access for its members, to commit its membership to trade policy rules, and to protect the benefits of negotiated agreements through dispute settlement. The main difficulty of joining the WTO lies in the adjustment and compliance costs – political, social, and economic – that accompany trade liberalization and de-regulation. Some of these costs are incurred because a number of institutional elements of WTO membership require expenditures to develop legal and regulatory systems, such as intellectual property protection, customs valuation, and product standards compliance. For poorer countries, external aid may be required to finance these expenditures. In addition, liberalization measures may entail disruption or displacement of local import-competing industries as part of the process of the re-allocation of domestic resources, a situation often made worse by factor immobility and other market rigidities. Internal market reforms and (in wealthier countries) adjustment assistance to workers may be necessary to smooth the process of adjustment that is necessary to move resources into more competitive industries, and may therefore shape the domestic policy agenda as part of joining the WTO. Poor countries in particular typically have deficient internal adjustment mechanisms, including a lack of infrastructure, weak market institutions, and insufficient trade capacity. Yet the benefits of a rules-based agreement guaranteeing non-discriminatory market access terms and dispute resolution provide the potential for increased trade and economic growth, and therefore also a strong argument for joining.

A related and more difficult question arises regarding the value of new membership to the incumbent WTO members, and how this factor may affect accession terms and the length of accession negotiations. Theoretically, it is clear that each additional member to the WTO brings the world economy closer to the ideal of fully liberalized global trade, and thereby increases economic welfare for all WTO members. However, the economic gains for the existing membership will be marginal if the country is small, and, even when the applicant country is large, the stakes may be small relative to the volume of world trade. Many applicant countries have already opened their economies to a certain degree, and the additional openness of WTO membership may be significant for them as individual countries, but less significant to the collective WTO membership, which is therefore less motivated to grant them admission to the organization quickly. Incumbent member countries also look at new WTO members in terms of their implications for future dispute settlement cases. Whatever gains from trade the new member may bring to the trading system, a country with unresolved compliance issues may create acrimonious dispute cases. For this reason, wary WTO members, especially those anticipating increased trade flows with the applicant country, will take a slower and more deliberate approach to the accession process. Finally, the incumbent countries may see the accession negotiations as an opportunity to extract concessions from the applicant country without having to offer reciprocal concessions.

The GATT system's accession process

Accession to the GATT from1948 to1994 was in many ways easier and more open than the WTO process that followed it. The GATT was a more limited agreement and of more modest scope, covering primarily trade in manufactured goods. As a condition of admission, an applicant country's compliance with the GATT was therefore easier to negotiate. In addition, since the GATT was originally conceived as a temporary ‘bridge’ agreement to a more comprehensive ITO, which never came into being, GATT membership was based on a Protocol of Provisional Application (PPA), which reduced an applicant's requirements to implement certain articles of the GATT, depending on the country's existing legislation (Jackson, Reference Jackson1969: 39–41; Lanoszka, Reference Lanoszka2001: 580–581).Footnote 7

GATT accession procedures were governed by GATT articles 33 and 26. In the early years of the GATT, countries applying for membership under article 33 typically entered into organized tariff negotiations (the 1949 Annecy and 1951 Torquay Trade Rounds), which upon ratification effectively granted membership to the new participant-signatories. Fourteen new members joined the GATT in this way, without separate protocols of accession. Subsequently, under article 33 a country could negotiate an individual protocol of accession, under the terms of the PPA described above, requiring a two-thirds majority vote of the existing CPs. From 1955 to 1994, 32 countries joined the GATT through article 33 protocols of accession. This was the pathway to GATT membership for countries that had not recently gained independence from a colonial power (see below). As the liberalizing measures of GATT negotiations accumulated over time, the ‘ticket of admission’ into the GATT increased commensurately. Yet the waiver provisions of the PPA allowed for considerable flexibility in some negotiations for membership, such as those for Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia, which had communist political systems and varying degrees of non-market and mixed economies.Footnote 8 In addition, countries anticipating accession under article 33 could make a declaration of ‘provisional accession’, which would allow the country to enjoy GATT (particularly MFN) treatment in its trade relationships with GATT members that sign on to the declaration (Jackson, Reference Jackson1969: 94).

The other pathway to formal GATT membership was through article 26:5(c), which applied to those countries that had previously been colonies of existing GATT members, but had gained national independence. If the colony had previously been treated as a customs territory under GATT rules, it was allowed to join the GATT, under sponsorship of the former colonial power. This was a simple and straightforward process under which 64 newly independent countries from Africa, the Caribbean, and Asian-Pacific areas became GATT members. In addition, the benefits of GATT membership were also extended to many countries that did not in fact have full GATT membership. Former colonies eligible for article 26:5(c) accession enjoyed ‘de facto application’ of GATT treatment during the interim period before they became full members, as long as they reciprocated with GATT treatment towards its existing membership (Jackson, Reference Jackson1969: 97–98).

In short, GATT membership was subject to varying terms of accession, and included various levels of participation. The underlying concept of GATT participation, based on its broadly inclusive nature, was to create a ‘big tent’ in order to spread the application of GATT treatment as widely as possible. This state of affairs appeared to generate increasing difficulties over time. In the absence of detailed protocols of accession, it was often unclear exactly what obligations many countries had under the GATT, especially those that had entered under article 26:5(c).Footnote 9

Accession rules in the WTO system

Compared to the GATT procedures for accession, the WTO is a much more legalistic organization. This is because it broadened the scope of trade negotiations into many new areas and thereby increased the stakes (and rewards) of membership. No longer limited primarily to tariff negotiations in manufactures, the WTO reaches into each member's agricultural subsidy, trade-related investment, intellectual property, services trade, customs valuation, and phyto-sanitary policies. All new WTO members must therefore comply with the obligations of the sum of all WTO agreements at the time they join, a much larger set of commitments than existed under the GATT. No ‘provisional accession’, ‘special protocols’ (as for non-market economies), or ‘de facto application’ of membership is possible in the WTO. In addition, WTO membership subjects its members to the discipline (and protection) of a dispute settlement system that is now subject only to a ‘negative consensus’. This means that all WTO members must together veto a dispute settlement decision in order to overturn it, in contrast to the ability of any member under the GATT (including the defendant country) to veto a decision. In principle, the goal of the new WTO approach was to define more precisely each member's rights and obligations, and to hold everyone more strictly to account in terms of abiding by the rules. In order to avoid dispute settlement cases, new members must therefore be in compliance with WTO obligations across a wide spectrum of policies, which increases the burden of accession negotiations.

The WTO accession process itself is also much more formal than it was under the GATT, even though the provisions of WTO article 12 state simply that countries may accede ‘on terms to be agreed between it and the WTO’ with approval by a two-thirds majority of the existing WTO membership (WTO, 1994), although votes are rarely taken. The complexity of the negotiations is revealed in the 20-step procedure for accession that has developed (see WTO, 2006), summarized in Table 3. The negotiations broadly follow two overlapping stages, the preparation of a potential member's ‘memorandum of the foreign trade regime’ (see below) and bilateral negotiations with Working Party (WP) members. As a practical matter, WTO accession decisions are driven ultimately by approval of the members, who have not delegated any formal negotiating role to the WTO Secretariat. Accession negotiations therefore take place between the applicant and the WTO membership. All interested WTO members can take part in the WP that presides over the accession process, and each incumbent member has the right to engage in bilateral negotiations with the applicant regarding specific issues.Footnote 10 Individual WTO member countries, even small ones, can potentially stall or block the progress of the WP in any given case.

Table 3. Accession procedures in chronological order

Source: World Trade Organization, Accessions page, http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/acc_e.htm.

Additional guidelines for accession are found in the Doha Declaration, in which the WTO members state that they:

attach great importance to concluding accession proceedings as quickly as possible. In particular, we are committed to accelerating the accession of least-developed countries (art. 9) … Accession of LDCs remains a priority for the Membership. We agree to work to facilitate and accelerate negotiations with acceding LDCs. (art. 46)Footnote 11

The hortatory language in the Doha Declaration, however, provided no guarantee of quick accessions, as the record has shown.

What determines the length of WTO accession negotiations?

It was common under the GATT system to refer to the terms of an accession protocol as the ‘ticket of admission’ to the organization. In practice, the price of admission to the GATT was often quite low, as described earlier in the discussion of waivers, article 26:5(c) accessions, and various intermediate levels of participation. Yet the later accessions to the GATT did reflect an acknowledgement of the increasing ‘cost’ of joining, in terms of tariff concessions and obligations, after several rounds of trade negotiations had continued to lower trade barriers (see Smith, Reference Smith and Schott1996). Still, the average length of time from application to accession for the 30 countries joining the GATT under individual article 33 protocols was 62 months (note that article 33 accessions during the Annecy and Torquay rounds did not require individual protocols). Some accession negotiations dragged on for many years, but even then the applicant country often enjoyed provisional GATT membership status, as was the case with Switzerland, Egypt, Philippines, Thailand, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. Most other countries joined the GATT more quickly, and often had de facto GATT status in most of their trade relations before officially joining.

In contrast, the WTO accession process is framed by two demanding institutional factors. The first is the applicant's preparation of the ‘Memorandum of the foreign trade regime’, followed by its review and evaluation by the WTO WP. In the Memorandum, the applicant country must identify all aspects of its legislation and administration that have a bearing on trade policy and WTO obligations. This document is then subjected to exhaustive scrutiny by the WP, which must ultimately be satisfied that the applicant's trade regime is in conformance with the requirements of WTO membership (see Table 3, steps 5–12). Members of the WP typically submit questions or challenges to the applicant's Memorandum, to which the applicant is obliged to respond, and to undertake corrections needed to come into compliance with WTO obligations. This process may go through much iteration, lasting from several months to several years. The second institutional factor is the right of any existing WTO member to negotiate a bilateral agreement with the applicant country regarding additional rules and concessions, which would then become part of a final MFN application in the WTO protocol of accession. Depending on the specific interests of an applicant's trading partners, an applicant may need to complete several bilateral agreements, and these negotiations may be detailed and acrimonious, leading to further delays in the accession process.

Negotiations to join the WTO are therefore potentially lengthy. The elapsed time for WTO accessions among the first 25 new members averaged 101 months, and Table 1B shows that the length of the accession process has increased over time, from the relatively short negotiations of early joiners Ecuador and the Kyrgyz Republic (40 and 34 months, respectively), to the typically longer negotiations of later joiners such as China (185 months), Nepal (179 months), and the Ukraine (174 months). Current applicants to the WTO as of August 2008 had already been negotiating for an average of 116 months (the sample includes recent applications), as shown in Table 2A. While some cases appeared to be near completion (Russia, Vanuatu), others had been dragging on since the pre-WTO period with no end in sight (Algeria, Belarus, Sudan, Uzbekistan). One reason for the longer accession process is that the concept of the ‘price of admission’ has become much more important, in view of the fact that the WTO has built upon 48 years of prior GATT-sponsored trade liberalization, in addition to the wider scope of agreements (and thus obligations) that all WTO members must accept. In joining the WTO, a new member benefits from the sum of all previously negotiated liberalization measures, and current members typically demand that the applicant make all the appropriate market access concessions and adjustments to its economy that are commensurate with WTO membership. These concessions include not only tariff reductions and the elimination of traditional trade barriers, but also offers of market access in services sectors, as well as compliance of national laws and regulations with the requirements of the TRIPS agreement, sanitary/phytosantiary standards, and technical barriers to trade. A legislative action plan to bring the legal and regulatory framework into line with WTO obligations is required. Kavass (Reference Kavass2007) notes that many applicant countries do not realize the nature and extent of reforms that will be required until after the detailed negotiations begin.

The WTO accession process can therefore be lengthy, complicated, and costly, especially for governments that do not have a well-established framework for regulating trade, intellectual property and other trade-related activities. Many developing and transition economies, burdened with a legacy of central planning and/or weak legal and policy institutions, have difficulty just determining where all the elements of trade policy are located in their own governmental structure. Poor countries may lack the capability of analyzing the impact of WTO membership on their economies, and may also suffer from a lack of commitment by the government, as the trade ministry competes with other governmental sectors for limited resources and priority in the country's policy agenda. These difficulties are likely to add to the time it takes to negotiate an accession agreement. As mentioned earlier, the lengthiness of the accession process may also be the result of the desire of incumbent WTO members to assure that all major WTO compliance issues have been laid to rest, so that the danger of acrimonious WTO disputes is minimized. According to this view, it makes little sense to rush the accession negotiations if the result is that many outstanding issues of contention remain with the new member regarding intellectual property, market access, and other policies affecting trade.

Perhaps the most controversial element of WTO accession lies in the fact that bargaining power lies squarely with the incumbent WTO members, especially the large and politically powerful countries, and these countries may have increased their exploitation of this power with each successive accession negotiationFootnote 12. Odell (Reference Odell2006: 9–11, 22–23) argues that any new bargaining situation forces negotiators to act on the basis of bounded rationality: to make the best decision given incomplete information and uncertainty about the outcome.Footnote 13 Additional experience, however, promotes a recognition of their own bargaining power, leading to strategies that can win additional concessions from applicants. The hypothesis is that WTO members involved in accession WPs began in 1995 with a new and unfamiliar negotiating situation, and then in the course of these negotiations learned progressively to impose increasingly demanding terms on applicants.Footnote 14 The bargaining asymmetry is reinforced by the fact that the applicant alone is asked to adjust its trade regime for the purposes of joining; no reciprocal concessions come from the incumbent members, who have ‘paid’ for their WTO benefits in earlier trade negotiations. This imbalance applies particularly to small applicant countries, which have few means of leverage or influence on WTO members in general, and can only appeal to moral suasion or plead their lack of resources to fulfill costly obligations. Even large countries, such as China and Russia, have had little room for deflecting demands for concessions in the bilateral stage of negotiations, although one can argue that China, with its large potential import market, was able to bargain for longer transition periods for some of its obligations. Russia, for its part, has appeared to be using what leverage it had in domestic energy market development to try to reach more favorable terms of WTO accession.Footnote 15

The record of WTO accessions so far has also revealed that new members must often make additional ‘rule commitments’, and often accept ‘WTO-plus’ terms of accession, that is they must make concessions that go beyond the existing WTO obligations of members at comparable levels of development.Footnote 16 The number of negotiated rule commitments is shown in Table 1B. The number of these commitments has also generally grown with each new accession, especially in the most recent cases, but, more importantly, details of some of these commitments show that they go beyond WTO obligations for existing members. Evenett and Primo Braga (Reference Evenett and Primo Braga2005) report, for example, that Jordan agreed to give WTO treaties precedence over other international treaties, beyond the requirements of customary international law, that Ecuador agreed to eliminate all subsidies before its accession date, and that China agreed to transitional safeguard provisions that do not apply to any other WTO members.Footnote 17 Adhikari and Dahal (Reference Adhikari and Dahal2003) report that Cambodia gave up its right to agricultural export subsidies and agreed to submit to additional TRIPs measures. In the services sector, most acceding countries ended up making commitments to open trade in many more sub-sectors than was agreed to by their peer WTO incumbents during the Uruguay Round (Evenett and Prima Braga, Reference Evenett and Primo Braga2005; Adhikari and Dahal, Reference Adhikari and Dahal2003).Footnote 18 While Kennett (Reference Kennett, Kennett, Evenett and Gage2005: 50–53) observes that not all rule commitments involve ‘WTO-plus’ provisions, the number of such commitments may be taken as a rough measure of the degree to which applicants have had to agree to special obligations of interest to incumbent WTO members.Footnote 19

In addition, applicants may be required to lower tariffs to levels lower than those of incumbent WTO members. For example, Anderson and Martin (Reference Anderson and Martin2005) calculated that the average bound agricultural tariff for all existing WTO developing country members was 48%, while the average for the first 25 newly acceding WTO members was about 20% (Table 1B), most of which are developing or transition countries. For LDCs that were already members of the WTO, the average bound agricultural tariff was 78%, but the average for the three new LDC members, Nepal, Cambodia, and Cape Verde, was 29.5%, well below the overall developing country average as well. Most new WTO members therefore entered with lower tariffs, by substantial margins, than their incumbent WTO member counterparts, indicating that the new members have had to submit to more demanding (from a mercantilist perspective) obligations than existing members. In addition, the pattern shows a general decline in the bound tariff rate as the total number of completed accessions increased (a trend to be examined in more detail below).

Despite the view of some legal scholars denouncing WTO-plus measures and extra tariff concessions (see for example Broude, Reference Broude1998: 164), the asymmetrical distribution of bargaining power has become a strongly embedded feature of the accession process. There is strong evidence that many WTO members are keen to press this advantage, based on a ‘consolidationist’ approach to the trading system (Smith, Reference Smith and Schott1996: 173). As indicated in the earlier discussion of the GATT's rather loose membership criteria and the frustration it caused in some members, one major motivation for negotiating a new trading system was to establish a more specific set of legal obligations that could be adjudicated in dispute settlement cases. This approach to the WTO trading system's accession process implies that new members with poorly developed market and trade institutions should be required to make concrete commitments to bring their economies into compliance with the norms of an open trading system. The ‘big tent’ of the earlier GATT accession conditions therefore gives way to the ‘narrow gateway’ through which new WTO members must pass.

Regression analysis

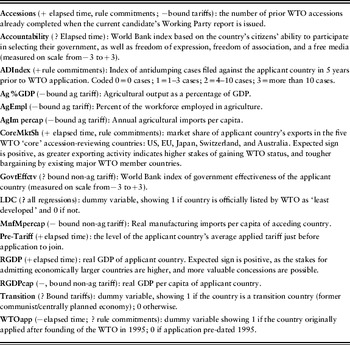

What factors have contributed to the lengthy accession process and to the terms of accession? It is difficult to generalize, since each country's negotiations are unique. However, it may be reasonable to hypothesize that certain factors have played a systematic role. Four OLS regression equations were tested, with the following dependent variables: (1) the elapsed time from WTO application to final accession; (2) the number of special WTO rule commitments agreed to by the acceding country; and (3) the final bound average non-agricultural and (4) agricultural tariff of the acceding country. Based on the institutional provisions of the accession process discussed above, one type of explanatory variable would try to capture the extent to which there is a gap between the applicant's current trade regime and the required WTO-compatible trade regime, such as development or transitional economy status, or measures of total or per-capita GDP. A greater gap would imply a longer negotiating process. These and additional explanatory variables may also indicate the extent to which the applicant country is important enough to target for additional concessions (and lengthier negotiations), such as those measuring market share in WTO members' markets and other economic profile statistics. Trade and political profile variables may suggest either longer or shorter negotiations, based on the tendency for the applicant country's exports to attract antidumping cases, for the country to have high pre-WTO tariffs, or to exhibit strong governance characteristics (a possible indication that the country will agree to quick negotiations in order to establish the ‘anchor’ benefits of WTO membership for its economy). Finally, explanatory variables regarding the negotiating circumstances, such as how many completed accessions have preceded the applicant's WP report, or whether the original application occurred before the WTO was founded in 1995, may indicate the importance of learning by incumbent WTO members involved in the negotiations, and how they view ‘carryover’ applications from the GATT era. The tested explanatory variables therefore fall into the following three groups; a complete listing of the tested variables and their expected signs is contained in Table 4:

1. Economic Profile variables. Economic variables such as the applicant country's GDP, per capita GDP, sectoral shares of employment or GDP (for agricultural and non-agricultural tariffs) may play a role in the length of the accession process and the terms of accession. In addition, a set of dummy variables identifies least developed country (LDC) applicants and transition economy applicants.

2. Trade and Political profile variables. One set of variables in this category measures politically sensitive profile information, such as the market share of the applicant in the five key WTO members typically involved in all accession negotiations (US, EU, Japan Australia, Switzerland), an index of antidumping cases brought in pre-WTO years against the applicant country, and the pre-WTO tariff level in the applicant country. In addition, the World Bank ‘government effectiveness’ and ‘accountability’ country indexes indicate a possible determinant of an applicant's efficiency and credibility in bargaining.

3. Negotiating circumstances. As an indicator of the bargaining experience and possible learning of the incumbent WTO negotiators, the ‘accessions’ variable measures the number of prior accessions already completed as the applicant country completes negotiating its accession protocol. Since the Working Party holds most of the bargaining power, the accumulation of negotiating experience may encourage each new Working Party to drive a harder bargain with the applicant. Thus, more accessions that have already been completed implies a longer bargaining process as the Working Party extracts additional concessions. In addition, there is a dummy variable WTOapp to distinguish ‘pre-Marrakesh’ applicants who first applied to the GATT, subsequently carrying over their application to the WTO, from those ‘post-Marrakesh’ applicants whose petition for membership came only after the WTO was founded.

Table 4. Independent variables and expected signs of coefficients

Elapsed time

The first set of regressions uses elapsed time from application to final WTO accession as the dependent variable. It is difficult to establish a specific behavioral model of time-to-accession because each case is subject to individual circumstances, and delays can arise from both sides of the negotiations. The linear regression model and limited availability of common data for all counties may therefore suggest statistical correlations rather than cause-and-effect relationship. Results for the elapsed time regressions are shown in Table 5A, and are arranged in descending order of the R-squared statistic. The results provide support for the hypothesis that the accession negotiations have become longer as the total number of WTO accessions has increased, at least for the first 25 completed accession cases. The variable Accessions represents the accumulated number of WTO accessions that had been completed before the final WP report for a given applicant country was issued. Thus, for the first new WTO acceding member, Ecuador, this number was 0 and for the acceding member with the latest WP report in the sample, the Ukraine, the number was 24.Footnote 20 The results indicate that for each additional WTO accession completed before this stage in an applicant's accession negotiations, the elapsed time from application to formal accession increased by approximately 3.3 to 4.4 months, ceteris paribus, with consistently strong statistical significance. The implication, based on the earlier discussion of asymmetrical negotiating strength and consolidationism, is that the WP has accumulated negotiating experience and has increasingly exercised its bargaining power for each case under review, leading to an increasingly lengthy accession process. It is also possible that incumbent bargaining power is enhanced by the network externality of WTO membership, a factor that would be consistent with these results. As more and more countries join the WTO, the cost of remaining outside the network increases for non-members, lending increasing bargaining power to existing members, which dictate terms of accession. Thus, increasing exploitation of bargaining power through learning is perhaps compounded by the inherent increase in bargaining power through the network externality as more countries join.

Table 5A. Regression results

Dependent variable: elapsed time to accession. N=25 (standard errors in parentheses)

Notes: * denotes significance at 10% level; ** 5% level; *** 1% level.

Data sources: CIA Handbook; IMF listing of transition economies; United Nations, Comtrade database; World Bank Governance Index database; World Bank WDI database; WTO website, pages for Accessions, Anti-dumping, Developing Countries; WTO trade statistics page; WTO (2004). See bibliography, ‘Databases and Websites’, for URL information.

The variables for post-Marrakesh application and pre-WTO tariff levels exhibited somewhat statistically weaker results, but nonetheless had the expected signs. Filing an application after the launch of the WTO on 1 January 1995 (WTOapp) reduced elapsed time by 21 to 31 months, with 5% significance in most of the regression variants in which it appears. The implication is that the fact that these ‘legacy’ membership applications were left incomplete from the GATT period may have been systematically more problematical.Footnote 21 A one percentage point increase in an applicant's pre-WTO tariff level increased elapsed time by 0.8 to 1.6 months, with statistical significance at 5% or better in three of the five variants in which it appeared, but without statistical significance in the other two. The trade policy profile variable, AD Index (showing AD cases filed against the applicant in years prior to and during the negotiations), indicated an increase of nine to ten months for each unit increase in the index, suggesting that countries targeted by antidumping investigations will face longer negotiations.Footnote 22 Finally, the ‘good governance’ variable Accountability, as well as the dummy variables for LDCs and for transition economy status, were generally insignificant.Footnote 23

Among the economic profile variables, real GDP (RGDP) and the applicant's share in five key WTO import markets (CoreMktSh), were highly correlated with each other.Footnote 24 All had a positive coefficient, and were in some cases significant at the 10% level or better. For example, an increase in an applicant's total import market share in the aggregated ‘core’ WTO countries (US, EU, Australia, Japan, Switzerland) by one percentage point increases the candidate country's elapsed time by 15 to 21.5 months as reported in three variants, suggesting longer bargaining the greater the country's importance as an exporter. An applicant country's size and economic ‘footprint’, based on these various measures, all suggest that larger countries take somewhat longer to negotiate accession.

In principle, the impact of applicant country's bargaining power, based for example on its GDP or the size of its import market, appears at first to be ambiguous. Larger countries may be able to dictate better terms (and perhaps quicker accessions) than smaller countries, based on the supposed eagerness of incumbents to add a larger contributor to world trade to their ranks. However, a larger country that bargains harder could also lengthen the negotiations. In addition, small countries may agree more quickly to the incumbents' terms if their goal, for example, is to link in to the policy anchor of WTO membership. In the regressions, the economic profile variables all exhibit a positive impact on elapsed time. This suggests that either the applicant's additional bargaining power (if any) tends to lengthen the negotiations, or the applicant's size increases the stakes for the incumbents and thereby encourages them to bargain harder to strike WTO entry terms favorable to them. Smaller countries, may, ceteris paribus, be insignificant enough to warrant quicker approval.Footnote 25

In summary, based on the sample of 25 countries that joined the WTO from 1995–2008, the regression equation with the best fit indicated that the elapsed time from application to final formal accession had a ‘baseline’ intercept value of 39.5 months, with time increasing by 3.3 months for each additional accession of other countries completed before that country's WP report, and about nine months for each additional unit increase in the AD index. Applying for accession after the founding of the WTO reduced elapsed time by about 25 months, and a 1% increase in the applicant's average applied pre-WTO tariff level increased the negotiating time by 1.4 months. A one-unit increase in the applicant government's Accountability index reduced elapsed time by about eight months, but this result was not statistically significant. The adjusted R-squared value of this regression was 0.762.

Table 5B. Regression results

Dependent variable: rule commitments. N=25 (standard errors in parentheses)

Notes: * denotes significance at 10% level; ** 5% level; *** 1% level.

Data sources: CIA Handbook; IMF listing of transition economies; United Nations, Comtrade database; World Bank Governance Index database; World Bank WDI database; WTO website, pages for Accessions, Anti-dumping, Developing Countries; WTO trade statistics page; WTO (2004). See bibliography, ‘Databases and Websites’, for URL information.

Table 5C. Regression results

Dependent variable: Non-AgTariff. N=25 (standard errors in parentheses)

Notes: * Denotes significance at 10% level; ** 5% level; *** 1% level.

Data sources: CIA Handbook; IMF listing of transition economies; United Nations, Comtrade database; World Bank Governance Index database; World Bank WDI database; WTO website, pages for Accessions, Anti-dumping, Developing Countries; WTO trade statistics page; WTO (2004). See bibliography, ‘Databases and Websites’, for URL information.

Table 5D. Regression results

Dependent variable: AgTariff. N=25 (standard errors in parentheses)

Notes: * denotes significance at 10% level; ** 5% level; *** 1% level.

Data sources: CIA Handbook; IMF listing of transition economies; United Nations, Comtrade database; World Bank Governance Index database; World Bank WDI database; WTO website, pages for Accessions, Anti-dumping, Developing Countries; WTO trade statistics page; WTO (2004). See bibliography, ‘Databases and Websites’, for URL information.

WTO rule commitments

An important part of the negotiating agenda is the set of rule commitments that applicant countries agree to in their terms of accession, which is part of the ‘price of admission’ to the WTO. As noted earlier, rule commitments vary in terms of their severity, and no attempt has been made to categorize or weight them in the regression data. The regression results for the number of rule commitments by an applicant, reported in Table 5B, confirm the informal observations of Evenett and Primo Braga (Reference Evenett and Primo Braga2005) that applicant concessions have increased as the number of accessions has increased. The accessions coefficient was positive and highly significant in most regression variants, indicating an increase in the number of rule commitments by 0.6 to 1.1 for each additional accession completed prior to an applicant country's WP report. Among the applicant status and trade policy profile variables, the results were weaker, with some unusual results. An increase by 1 in the AD index resulted in three to five additional rule commitments, with 10% or better statistical significance in four out of five variants. LDC status resulted in 10 to 14 fewer rule commitments, with 10% or better significance in the four variants tested. This result is consistent with the official WTO proclamation to facilitate LDC accession. Post-Marrakesh applications appear not to influence the number of rule commitments, however, as this variable showed no statistical significance.Footnote 26

The economic and political profile variables, in contrast, showed much more significant results. A one percentage point increase in import market share among key WTO members increased the number of rule commitments by 12 to 14.5, for example. A particularly interesting result was that a one-unit increase in the government accountability index resulted in five to seven fewer rule commitments, with 10% or better significance in the four variants tested. The World Bank accountability index focuses on measures of political participation, transparency, and openness, such as freedom of the press. This result suggests that applicant countries exhibiting greater accountability may have been regarded as potentially less disruptive in terms of their trade practices, thereby requiring fewer constraining special rule commitments. Looking at it from a negative perspective, the lower the accountability rating, the more the incumbent WTO members may have thought it necessary to bind the new member with special constraining rules.

In general, the regression results support the hypothesis that learning based on previous accessions has increased rule commitments. In the variant with the best fit, the baseline number of rule commitments was about 18, and each additional prior accession increased the number of rule commitments by about 0.9, with this number reduced by 10 for LDC applicants, and by 6 for each one-unit increase in an applicant's accountability index. A one-unit increase in the AD index increased rule commitments by about 4, and a $10 billion increase in an applicant's real GDP increased rule commitments by about 0.4. The adjusted R-squared value was 0.83.

Tariff commitments

Results for average final tariff binding commitments by newly acceding countries are shown in Tables 5C and 5D. In these regressions, lower tariff bindings represent a tougher bargain for applicants and tighter WTO commitments. The results show consistently that additional WTO accessions by other countries tighten subsequent applicants' tariff bindings, with statistical significance at the 5% level or better. For non-agricultural tariff bindings, each additional accession lowers (tightens) the average bound tariff by approximately 0.4 percentage points; for agricultural tariff bindings, it tightens the tariff by 0.5 to 0.6 percentage points. LDC status generally allows for less stringent tariff bindings. Final bound non-agricultural tariffs for LDCs were higher by seven to eight percentage points, with 5% or better statistical significance. For agricultural tariff bindings, the LDC effect was also strong statistically, raising them by 14 to 16 percentage points, with 1% statistical significance in most cases. One interesting result is that transition country status is most significant for non-agricultural tariff bindings, and actually tightens them by an additional seven to 8.5 percentage points. The transition economy dummy coefficient for agricultural tariff bindings was also negative, but significant at the 10% level in just two of the four variants, reducing (tightening) the agricultural tariff by five to seven percentage points. There is informal evidence that several transition countries accepted lower, more stringent tariff bindings in manufactures as part of their strategy to adjust their economies and integrate more quickly into the world trading system (see Drabek and Bacchetta, Reference Drabek and Bacchetta2004). Along similar lines, the World Bank government effectiveness measure was highly significant in some regression variants, lowering the negotiated non-agricultural tariff by five percentage points, but remained insignificant in explaining agricultural tariffs.Footnote 27 More effective and efficient governments tended to agree to tighter tariff bindings, perhaps again as part of an ‘anchor’ strategy that welcomed WTO discipline. Higher overall pre-WTO applied tariffs, on the other hand, indicated somewhat higher final tariff bindings for non-agricultural goods, but not for agricultural goods.

Among economic profile variables, manufacturing imports per capita and real GDP per capita were statistically significant at the 5% level of better, but only in the non-agricultural tariff regressions. An increase in an applicant's annual per capita manufactures imports by $100 decreased the negotiated average non-agricultural tariff by about 0.1 percentage point, and that an increase in real GDP per capita of $100 decreases this tariff by about 0.06 percentage points. An interpretation of this result that is consistent with WTO incumbent bargaining power would be that tariff negotiations were tougher on applicant countries with more manufactures imports and higher GDP per capita, since the market access stakes were higher for WTO incumbents. None of the other economic profile measures showed significant results in either the non-agricultural or the agricultural tariff regressions. In the best-fit regression variant for non-agricultural tariffs, with an adjusted R-squared statistic of 0.66, the baseline bound tariff level was about 20%, with each additional prior accession reducing this number by about 0.4, LDC status increased it by 8, the applicant's transitional economy status lowering it by about 8, and an increase in the government effectiveness index by 1 decreased the negotiated tariff by five percentage points. The best-fit regression for agricultural tariffs had an adjusted R-squared value of just 0.388. It showed a baseline tariff of 30.4%, with each additional prior accession lowering the number by about 0.5, LDC status raising it by about 14, transition economy status lowering it by about 7, and each additional $100 of agricultural imports per capita decreasing the tariff by two percentage points (but not statistically significant at the 10% level).

Outstanding accession cases

As of August 2008, there were 26 countries under review for WTO accession. Together these countries represent about 8% of the world's population, 2% of world GDP, and 3% of world trade. By far the largest is the Russian Federation, but there are other countries of significant population and/or GDP, such as Iran, Iraq, and Algeria. There are also very small applicants in this group, including Andorra, Bahamas, Bhutan, Samoa, Sao Tome & Principe, Seychelles, and Vanuatu. Some have submitted applications for WTO membership recently, but others are still in the group of ‘legacy’ applicants from the GATT, including the Russian Federation, Algeria, Belarus, Sudan, and Uzbekistan. As noted earlier, the average elapsed time since application to August 2008 for this group was already over 116 months, already longer than the average for the first 25 WTO members to join (101 months). Eleven countries are in transition from non-market to market economies and nine have LDC status. Several are currently suffering from ongoing civil wars or insurgencies (Afghanistan, Iraq, Ethiopia, Sudan) and many others also exhibit questionable political stability.Footnote 28 Two appear on the US list of ‘countries of concern’, formerly described as ‘rogue states’ sponsoring terrorism (Sudan, Iran).Footnote 29 This group is therefore, on average, poorer, smaller, less stable, and less likely to receive full support from WTO incumbents than the sample of 25 new WTO members. Based on the foregoing analysis, it may be expected that their WTO accession negotiations will be lengthy. As for the group of 17 non-member, non-applicant countries, it also contains several LDCs and several politically difficult cases, such as North Korea, Liberia, and Somalia. Most of the non-applicant group do not even have observer status at the WTO, and so have not even shown interest in joining.

The current applicants continue their negotiations in uncertain and in many ways more pessimistic times. The Doha trade negotiations, launched so hopefully in October 2001, suffered through the failed Cancun ministerial meeting in 2003 and became increasingly mired in bickering until the series of collapsed talks in 2006, 2007, and 2008. Trade pessimism appears to be rising in the US and EU, making these WTO members more likely to drive a hard bargain in accession negotiations, since they may have come to see these negotiations as an opportunity to wring concessions from new WTO members that could not be won multilaterally in the Doha round. As for the applicants, while most are likely to see the ‘static’ advantages of WTO membership, based on MFN treatment and protection of gains under dispute settlement, some may now be questioning the ability of the WTO to deliver dynamic gains through progressive trade liberalization.

Three concerns, three proposals

The WTO system is required by its institutional mandate to strike a balance between openness to new members and discipline in maintaining adherence to its rules and norms. Thus, long accession negotiations can be defended by existing members as the necessary price for maintaining the integrity of the organization, as well as defending their national economic interests. It is also clear, however, that WTO accession negotiations have often led to ‘WTO-plus’ requirements for new members. This is the inevitable result of a process that gives most of the bargaining power to incumbent members, with no formal guidelines on terms of accession. From the consolidationist point of view, one could argue that stricter entry requirements, even beyond the obligations of current members, serve to enhance the liberal trade order. Furthermore, some countries have apparently accepted WTO-plus terms as politically useful external anchors for internal reforms. Yet the WTO accession process as it has developed reveals three potentially serious concerns.

1. Opportunity cost of delayed accession. The first problem is that delays in accession entail an opportunity cost of foregone trade, and foregone participation in the WTO system. The longer countries remain outside the WTO system, the less the gains from trade for them and their (potential) trading partners. The counterargument is that shorter accession times imply less comprehensive compliance and more disputes, perhaps crippling trade relations and decreasing the gains from trade down the road. How might the accession process be shortened without undermining the integrity of the trading system? One possible remedy would be to partition WTO benefits and corresponding obligations with a program of graduated membership, more like the ideas of provisional membership and special protocols of accession under the GATT system of old. Countries could ‘partially’ join the WTO with initial commitments to more liberal trade in goods, followed by concessions in TRIPS and other areas later on. Existing WTO members could similarly withhold WTO benefits in terms of adjusted tariff treatment, for example, with timetables for ramping up to full benefits that are commensurate with the applicant's schedule of increasing WTO compliance. The key to this approach lies in relaxing the accession principle of full compliance with existing WTO agreements, at least in terms of WTO accession.Footnote 30 It is true that partial membership would complicate WTO relations within the organization, but a reformed system could use strict timetables and quid pro quo concessions and benefits to promote it and encourage it as a transitional arrangement.

A simpler and more modest alternative would be to formally introduce special and differential (S&D) treatment into WTO accessions, especially for LDCs but perhaps on a graduated basis for more advanced developing countries as well. The WTO General Council did in fact issue a decision (WTO, 2002) that ‘[n]egotiations for the accession of LDCs to the WTO be facilitated and accelerated through simplified and streamlined accession procedures’, declaring that ‘WTO members shall exercise restraint in seeking concessions and commitments’ and grant special and differential treatment in terms of transition periods for compliance.Footnote 31 Charnovitz (Reference Charnovitz2007: 18) has noted, however, that the subsequent protocols of accession for two LDCs, Cambodia and Nepal, did not contain any indication that such S&D treatment was applied. The evidence from the regression study above suggests that the WPs applied milder requirements on LDC accessions informally, in terms of the number of rule commitments and the level of tariff bindings. A formal provision in accession rules and protocols that specifies S&D treatment and extends it to include transition periods would establish the desired framework for more flexibility and perhaps faster negotiations. However, implementing formal, specific S&D requirements is likely to be difficult, since WTO members would thereby be conceding significant bargaining power.Footnote 32

The informal nature of WTO incumbent negotiating flexibility is also evident in certain aspects of China's protocol of accession, which included several transitional provisions. A large country with attractive market access prospects for incumbent WTO members may have enough leverage to negotiate more favorable terms, but, in general, no applicant country can count on any negotiated easing of accession terms. To ease the general rules requiring a complete single undertaking requirement upon accession, more systematic WTO guidelines for the accession WP would be required, and as Lacey (Reference Lacey, Streatfeild and Lacey2007) has noted, WTO members are unlikely to yield their powerful negotiating leverage. The problem is made more difficult because applicant countries themselves may also be responsible for delays in accession. Yet as a practical matter, in view of the list of remaining applicant and other non-member countries, some additional flexibility in WTO accession requirements to most of the remaining and future applicants, based on an extension of the General Council decision discussed above (WTO, 2002), would allow the admission of new members more quickly into the WTO system.

2. Financial and technical requirements for meeting WTO obligations. The second objection relates to the resource capacity of many new and potential WTO members to adjust to the requirements of membership. Many WTO rule commitments require government expenditures and institutional development that may be costly to fulfill. Finger and Schuler (Reference Finger and Schuler2000) documented the costly nature of certain Uruguay Round commitments, including TRIPS, customs valuation, trade facilitation, and sanitary/phytosanitary standards. In the absence of systematic aid and technical assistance, these requirements represent unfunded mandates that many poorer countries cannot afford, or which would divert scarce resources from more productive use in those countries. In poor countries, with undeveloped markets and institutions, the burden of adjustment can be great. The solution to this problem lies in building more coherence in WTO relations with the World Bank, IMF, development banks, and other international institutions and agencies. The WTO, along with several other international organizations, has in fact sponsored an ‘Integrated Framework’ (IF) program for helping the LDCs, the poorest of the developing countries, to build the necessary institutional capacity and expertise to take part in the world trading system, including WTO accession.Footnote 33 However, these efforts have not appeared to reduce significantly the time-to-accession.Footnote 34 For other developing countries with income levels above the LDC cut-off, IF aid is currently not available, although the World Bank has stepped up efforts to support WTO accession countries (Auboin, Reference Auboin2007: 16). In the absence of IF assistance, trade negotiators from the rich countries do not come to the bargaining table with capacity-building budgets to sweeten the pot, and are not inherently qualified to negotiate the terms of their use (see Finger and Wilson, Reference Finger and Wilson2007). Better coordination of financial compensation to offset the costs of WTO rule commitments and other access obligations for all (not just LDC) developing country and transition economy applicants could not only speed the accession process, but also facilitate a more rapid integration into the WTO system. The key is that temporary, transitional subsidies could be used in this manner to secure permanent liberalizing measures and gains from trade.

3. Consequences of Lopsided Bargaining in Accessions. The third objection is largely political, but with potentially serious economic consequences. In the absence of guidelines on the terms of accession, the lopsided negotiations format, pitting the collective WTO incumbent membership against a single applicant, tends to be discriminatory in what it can demand from the acceding country. In response to this objection, it is reasonable to observe that stricter WTO-plus commitments and tariff bindings by applicants to levels below those of existing WTO members do in principle contribute to a more open trading system, and may even help those countries secure internal reform programs. Yet to the extent that the outcome is the result of power politics, the ends may not justify the means. In general, within the WTO consensus-based system, a certain amount of arm-twisting, threats, and bullying is bound to take place behind closed doors, and one must acknowledge such practices by the large countries as a fact of life in global trade relations.Footnote 35 Yet if the deck is stacked too heavily against the applicant countries, it will be difficult for many of them to achieve a sense of participation in the WTO as a trade forum. The risk is that heavy handed treatment in accession talks may poison the well of future trade negotiations. One possible solution to this particular problem could begin with an understanding among incumbent WTO members restraining the use of WTO-plus demands, again along the lines of the 2002 General Council decision (WTO, 2002). For example, the process could establish benchmarks for expected entry concessions on the part of the applicant, based on the obligations of current members of similar size and development status. In the absence of formal guidelines for the accession WPs, it would, however, be much more difficult to establish the practice of restraint, given the pattern of demands shown by existing members towards WTO applicants so far.

Conclusion

Many observers have complained about the length of WTO accession negotiations, and about the increasingly demanding concessions that incumbent members have been extracting from new members. This study has provided some statistical confirmation of the patterns of elapsed time in the negotiations and of the terms of accession. The regression results show a link between cumulative accessions and increasing length of time until a country's accession is complete, suggesting that incumbent WTO members have learned to assert their bargaining power more and more in each new accession negotiation. The number of WTO rule commitments has increased for each new accession completed, and the final average bound tariffs in agriculture and in non-agricultural goods have been tightened. For least developed countries, the preliminary result (based on the cases of Cambodia, Nepal, and Cape Verde) is that the accession negotiations are not significantly shorter, despite the intention of the Doha agenda to expedite the process. Their terms of accession have been somewhat less demanding, however. Still, the prospects for the group of 26 current WTO applicants are not encouraging. Many have already been negotiating longer than those countries that have acceded to the WTO, and many may face delays for various political reasons.

The WTO remains arguably the most successful international organization of its kind, bringing significant economic benefits to its members through a system of rules, a forum for dispute settlement, and a framework for further trade liberalization. It has indeed moved closer to universal membership, but many of the remaining accession cases are likely to be extremely difficult. The accession process has become excessively lengthy and burdensome for applicants, delaying the gains from trade and a more inclusive trading system, imposing heavy financial costs on new members, and potentially creating lingering resentment from the one-sided negotiations. WTO members could improve the accession process by introducing more flexibility in transition periods, improving the coordination of aid to fund mandated internal reforms, and limiting the demand for ‘WTO-plus’ concessions from applicants. Some of these provisions are already in place, formally or informally, for LDC applicants, through the IF facility and the 2002 General Council decision on LDC accessions. A formal implementation of these reforms and their extension to applicants with incomes above the LDC level, perhaps on a graduated basis, could contribute significantly to achieving the goal of universal membership.

WTO rules have imparted to its members superior bargaining power in accession negotiations, which they have learned to exploit, all the more so in response to the stalled Doha Round. They are unlikely to give up their superior bargaining power easily, but perhaps the best prospect would lie in an effort to revive the GATT-based approach of getting everyone inside the tent first through a broader application of S&D treatment in accessions, supported by redoubled efforts to revive multilateral trade liberalization. As a consensus based organization, the WTO may in fact find it easier to promote multilateral trade liberalization in future years by easing up on the draconian accession process now, thereby promoting a more viable system of participation and ‘ownership’ by its new members.