1. Introduction

The Canada–US Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) created a system for binational panel judicial review of antidumping and countervailing duty determinations of domestic government agencies. This system replaced judicial review in the domestic courts with ad hoc tribunals composed of three panelists from one country and two from the other. In the case of Canada and the United States, both countries have laws in English and follow the common law tradition.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) extended the Chapter 19 system to include Mexico.Footnote 1 In the case of Mexico, laws are in Spanish, it follows the civil law tradition, and Mexican law has distinctive features, such as the concept of Amparo. Amparo applies to the Mexican equivalent of judicial review of administrative action, among other matters. The extension of this system to Mexico transplanted the common law concept of judicial review into the Mexican legal system, albeit via the application of the applicable standard of review in Mexican law.Footnote 2 The extension to Mexico of this system of common law judicial review has not been a smooth process.Footnote 3

In Chapter 19, the applicable law is not NAFTA, but rather the domestic law of the importing country that applies its domestic trade remedy laws.Footnote 4 NAFTA Article 1904 requires the binational panel to apply ‘the standard of review set out in Annex 1911 and the general legal principles that a court of the importing Party otherwise would apply to a review of a determination of the competent investigating authority’. In the case of Mexico, the standard of review in Annex 1911 is Article 238 of the Código fiscal de la federación. Footnote 5

NAFTA Chapter 19 was a key issue in the NAFTA renegotiation that produced the USMCA.Footnote 6 The United States wanted to eliminate this dispute settlement mechanism, having been the target of 43 of the 71 matters brought before Chapter 19 panels.Footnote 7 Chapter 19 is unique to NAFTA. It originated in CUSFTA as a substitute for substantive rules on trade remedy laws.

There were three reasons that Canada wanted to replace judicial review by the US judiciary with binational panel review: (1) with no appeals and time limits, it would provide speedier resolution of trade remedy disputes; (2) the panelists would have greater expertise than judges in a highly technical area of law, resulting in less deference to government investigating agencies; and (3) binational panels would have less bias against foreign companies than domestic courts.Footnote 8

Initially, there was resistance on the part of the US judiciary to having foreign lawyers interpreting and applying US law, particularly with the expansion of Chapter 19 to include Mexico under NAFTA.Footnote 9 Mexico agreed to give up on Chapter 19, but Canada insisted on keeping it in place. In the end, this strategy allowed negotiations to progress to a successful conclusion, one that preserves Chapter 19 for all parties (now USMCA Chapter 10).

Some argued that this system was no longer necessary, because domestic judicial review of trade remedy measures has improved in the United States, and Chapter 19 suffers from defects, such as a shortage of expert panelists.Footnote 10 However, it has played a key role in Canada–United States disputes over Canadian softwood lumber exports, and permits duties to be refunded when Canada succeeds in overturning US antidumping and countervailing duties, something that the WTO dispute settlement system does not provide. Moreover, Chapter 19 has succeeded in meeting some of its original objectives. Binational panels have avoided the perception of national bias, except in rare cases in which the panel has divided along national lines.Footnote 11 The absence of appeals to domestic courts has achieved the objective of shortening the time it takes to resolve a dispute; the Extraordinary Challenge Committee review process has been used only three times each for CUSFTA and NAFTA cases.Footnote 12 Lack of expertise in trade remedies law continues to be an issue, but one that has improved over time. Nevertheless, even if Chapter 19 has met the original objectives sufficiently for parties to include it in the USMCA, the experience of the WTO Appellate Body serves as a cautionary tale regarding the importance of adequate legal reasoning in international trade tribunals.

Why was the Binational Panel such a controversial topic of the new agreement? Why did Canada insist on keeping it, the United States seek to eliminate it, and Mexico agree to abandon it? In the context of transnationalism, the law is not only instrumental for shared economic purposes but also expressive of national and supranational legal cultures. Negotiators, drafters, and panelists share a historical, cultural, and perhaps even an emotional attachment to their legal practices and communities.Footnote 13 USMCA jurisdictions needed to develop or maintain a shared legal understanding, but also sensibility to the law of each country. Thus, it may come as no surprise that Canada, a bastion of domestic bilinguism and bijuralism, also sought to maintain this vehicle for cross-cultural understanding at the transnational level. However, it is unclear to what extent the binational panel system has achieved this objective.

This article analyzes the extent to which differences in language, legal traditions, and legal cultures imply limits on the effectiveness of inter-systemic dispute resolution. What are the key linguistic and common/civil law differences in this regard? Has the binational panel system been able to reconcile different conceptions of standards of review? To what extent can one really understand the ‘other’: can a foreign lawyer understand and apply the general legal principles that a court of the importing Party otherwise would apply to a review of a determination of the competent investigating authority, in accordance with NAFTA Article 1904.2? For instance, can a US lawyer interpret and apply the Mexican standard of review as a Mexican lawyer would? It is not always possible to answer to these questions from a reading of panel decisions. In some cases, there is something missing in the panel's reasoning. For example, in place of an explicit application of the standard of review, there might be only a discussion of the insufficiency of evidence or the inadequacy of the reasoning of the investigating authority.Footnote 14

Our objective is to identify a subset of issues raised by the binational, bilingual, and bijural nature of this system so that they can become the subject of further research in the Chapter 19 system and in other systems that face similar issues.Footnote 15 This is the first article to analyze these issues systematically in the context of NAFTA Chapter 19.Footnote 16 In the current international environment, in which the role of dispute settlement systems is being called into question, it is more important than ever to consider how well binding trade dispute settlement is working, particularly in the North American context, and particularly in light of the new United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, in which the NAFTA Chapter 19 system will continue to operate. This article focuses on how well binational panels have operated across different languages, legal systems, and cultures. Our focus is on how the backgrounds of panelists affect their legal reasoning. Even when one agrees with the conclusion of a tribunal on a particular legal issue, one can disagree with the reasoning (as happens in concurring opinions, for example). Even if one agrees with the final outcome of a particular dispute, one can still disagree with a tribunal's legal reasoning. Defective legal reasoning in one case can undermine a tribunal's credibility and affect outcomes in future cases, even if it does not change the outcome of a case in which it occurs. Indeed, one can attribute the collapse of the WTO Appellate Body to defects in legal reasoning, at least in part.Footnote 17 Does the challenge of assessing the adequacy of the reasoning of an investigating authority in a different language, a different legal system, and a different legal culture undermine the adequacy of the reasoning of the panel itself?

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 analyzes how legal parochialism and human cognition can affect the legal reasoning and processes of panels, based on relevant literature and interviews with panelists, arbitrators, and their advisors. We then analyze different barriers to overcoming legal parochialism. Section 3 analyzes linguistic barriers. Section 4 analyzes legal culture barriers. Section 5 analyzes professional shortage barriers.

2. Legal Parochialism and Human Cognition

Legal parochialism can have a profound impact on outcomes. Solutions differ in common law and civil law, due to conceptual differences. Disputes tend to arise when there are difficult legal issues to resolve, and that is where conceptual differences matter the most. Legal parochialism operates on different levels. At a basic level, it can hamper the ability to determine whether there are differences between legal concepts. Beyond detection of differences, it can complicate conceptualizing and applying concepts in a way that fully appreciates the differences. Perhaps the most pernicious effect occurs when a tribunal member does not believe that a decision is right, because it does not ‘feel’ right. It would be a mistake to underestimate the importance of legal parochialism in bijural settings.Footnote 18 Indeed, the effect of biases that stem from legal parochialism, and how to counter them, would be a useful addition to the growing literature on the effects of cognitive biases on legal reasoning.Footnote 19

While the bijural composition of Chapter 19 panels may help to counter legal parochialism, some cognitive biases continue to operate even when we are aware of their existence.Footnote 20 Moreover, if panelists are unaware of their use of cognitive shortcuts, they are unlikely to correct cognitive errors.Footnote 21 Availability bias (the tendency to think that examples of things that come readily to mind are more representative than is actually the case) can be mitigated.Footnote 22 An example in the binational panel context might be to give greater weight to common law concepts, or to use common law concepts as a filter, when trying to understand and apply civil law concepts. Awareness can mitigate some other biases, such as the ‘compromise effect’ (the tendency to take less extreme options if mediocre options are available). However, the anchoring effect (tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered) is more difficult to eliminate.Footnote 23 To what extent might this cause an American common law panelist to rely too heavily on the opinion of a Mexican civil law panelist who writes the first draft of a decision or, alternatively, to give even greater weight to a draft written by a fellow American common law panelist? Anchors that do not provide any useful information (for example a common law concept that does not help in the interpretation and application of a civil law concept) may still influence legal reasoning, even if the panelist knows that the initial information does not add any value to the decision-making process.Footnote 24 Moreover, people are vulnerable to hindsight bias (the tendency to view events as more predictable than they really are) even when they are aware of it, and even many years of legal experience combined with advanced knowledge about hindsight bias are not mitigating factors. Moreover, more detailed information may lead to stronger cognitive illusions.Footnote 25 With respect to cross-cultural communication and cognitive bias, evolutionary psychology tells us that the influence of evolutionary forces on human intuitions decreases their reliability. For example, tribalism influences political views and affects the acceptance of scientific evidence. Counterintuitively, the more educated a person is, the more likely it is that they will use their intellect and education to counter scientific arguments that fail to coincide with the prevailing view of their group.Footnote 26 It is beyond the scope of this article to conduct the necessary scientific experiments to analyze these questions in greater depth. Rather, our point is that a linguistic, cultural, and legal background is highly likely to influence legal reasoning, in the same way that other intuitive cognitive biases would do.

Our perceptions of the world pass through cognitive filters that are wired into our brains based on the evolutionary forces that have shaped the human brain, but also through more recently acquired individual filters based on language, culture, education, and experience. Culture, language, legal, and professional background create cognitive filters through which individual panelists process concepts and information. For example, a Chapter 19 panel may be composed of an economist, a Mexican lawyer with a focus on domestic law, a Mexican lawyer with a focus on international law, a common law trade lawyer, and a common law lawyer with a focus on international law. A common law lawyer can have great difficulty understanding the Mexican legal concept of amparo. An economist might not even try to understand it and leave it to the lawyers. If a panelist is not able to understand foreign legal concepts through the filter of the logic and perspective of their educational background (common law or civil law, domestic law or international law background, lawyer or economist), they are not able to understand the concepts.Footnote 27

In some Chapter 19 panels involving Mexican dumping investigations, Mexican lawyers focus more on procedural issues than do American lawyers. The importance of Mexican procedural law is unfamiliar to American lawyers, who tend to focus more on substantive issues, and they depend on the Mexican panelists to navigate Mexican procedural law. Moreover, in addition to difficulties associated with different backgrounds in different legal backgrounds, many Chapter 19 panelists do not have expertise in trade remedies law. They may have expertise in tax law, investment law, finance law, or other areas of law, and process concepts from trade remedies law through their own area of expertise. The panel selection process could be improved by screening panelists for expertise in trade remedies law, as well as for training in both civil law and common law. However, since many panelists are drawn from law firms, conflicts of interest limit the pool of expert panelists. Moreover, a lack of strict requirements for the qualifications of panelists in Chapter 19 gives governments too much discretion to choose less qualified panelists. Thus, while it is unrealistic to expect all panelists to develop expertise in foreign law, there is much that can be done to improve the Chapter 19 process by improving selection of panelists.Footnote 28

In the context of cultural globalization, regional economic interdependence, and bijural trade agreements between nations, how should lawyers tackle foreign legal ideas? One possibility can be the functional approach of comparative law. According to functionalists, different legal institutions can perform similar functions.Footnote 29 Legal systems solve universal problems through different rules, concepts, or institutions.Footnote 30 In its most extreme version, the functionalist does not need to prove similarities among legal systems, but rather to ‘presume’.Footnote 31 When it appears that there are no similarities, the functionalist must try harder and reformulate the inquiry to find them.

In contrast, comparative legal studies question functionalism for its obsession with ‘sameness’ and its ignorance of differences.Footnote 32 There can be cross-cultural communication to understand differences and identify similarities, but this approach requires a degree of ‘cultural immersion’.Footnote 33 It requires, as Vivian Curran puts it: ‘increased acquaintance with foreign legal cultures’,Footnote 34 such as the fluency in the foreign language, to assess differences from within the legal culture. Others argue that it requires understanding legal traditions as a set of rooted historical attitudes towards the law in a given society.Footnote 35

Binational panels may draw upon each of these approaches, but they also face distinct challenges. The functional approach seems to be at the heart of the institutional design of the panel. Ultimately, binational panels serve as the functional equivalent of the domestic court and must apply the standard of review as a domestic court would.Footnote 36 However, it is unclear to what extent panelists are familiar with foreign domestic practice. Moreover, it is unclear to what extent they use comparative methodology to identify equivalent concepts between two legal systems. Panelists may be acquainted with the foreign legal culture because of foreign postgraduate degrees. Nevertheless, it is uncertain how symmetrical this cultural rapprochement between nations is. Do Canadian and American lawyers have experience in practice or study in Mexico to the same extent that the Mexican lawyers have experience in practice or study in Canada or the United States?

We argue that binational panels face a threefold challenge. First, they face a linguistic barrier. Words are difficult to translate, and their translation may increase the abstraction of certain concepts. Think, for instance, of the untranslatability of ‘anti-dumping’ to Spanish, which has adopted the English word for dumping. Moreover, the selection of translations involves political judgments and ideological decisions.Footnote 37 In turn, these translation decisions may influence the outcome of cases, as they do when applying the rules of interpretation to multilingual treaties.Footnote 38 Language is not only a way to communicate but a determining factor in shaping our worldview that even influences our cognitive processes.Footnote 39

Second, panels face a legal culture barrier. The acquaintance with a particular legal tradition is part of ‘tacit knowledge’.Footnote 40 Familiarity with legal culture influences how lawyers conceive, apply and critique legal institutions. Lawyers deploy, consciously or not, what we call legal shortcuts that allow them to perform legal activities in their own language, culture, and system with a higher degree of efficiency than a foreign lawyer.

Third, as a consequence of the first two obstacles, panels face a professional shortage barrier. Panels require lawyers to be experts in international trade law and trade remedies, but also to speak, or at least to understand a foreign language, and to master foreign rules, concepts, and doctrines. Some individuals may meet this demanding profile, but our research shows that the list of panelists does not always reflect these needs. The next part of this article will address these three issues in turn, before we ask to what extent our typology of issues represents problems of design or problems of implementation.

3. Linguistic Barriers

Linguistic barriers are nothing new for the law and the issues that they raise in trade remedy disputes between Mexico and the United States should be relatively manageable. However, differences among the texts of laws, court decisions, and panel decisions may lead to confusion if, for example, Spanish-speaking lawyers prepare legal arguments based on the Spanish text of the laws (and the Spanish translations of panel reports), while their counterparts prepare theirs in English.

Substantive differences in translated legal texts can arise from simple errors, difficulty in translating ambiguous terms and different placement of terms in the different languages, which creates ambiguity.

The category of simple errors is not as simple as its name implies. For example, there has been some discussion regarding the correct translation of ‘should’ and ‘shall’ in Spanish, among both negotiators and translators. In English, ‘should’ is generally not mandatory, whereas ‘shall’ generally is mandatory. However, Article 11 of the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding provides that a panel ‘should make objective assessment of the matter before it’, which has been interpreted as a mandatory due process provision.Footnote 41 Thus, in this context, ‘should’ means ‘shall’. The French text uses ‘devrait’ and the Spanish text uses ‘deberá’, which both mean ‘should’. In this example, there is no error in translation. Rather, the issue came to light as a result of subsequent interpretations of this provision in WTO disputes, which considered that such a due process provision must be mandatory by its very nature.

Another problem arises as the result of false cognates, i.e., words that appear similar but that have a different meaning in different languages, such as ‘doctrine’ in common law and ‘doctrina’ in Spanish and other civil law countries. The former refers to judicial precedents,Footnote 42 whereas the latter relates to the academic work of researchers.Footnote 43

On occasions, a literal translation from English to Spanish denotes an entirely different legal institution. Consider the notion of ‘nuisance’ cited in Bovine Beef and Eatable Offal. Footnote 44 In the common law, nuisance refers to a private law liability. By contrast, in Mexican public law, a ‘nuisance’ (acto de molestia) refers to the state action that affects individual rights without a final deprivation. This bijural distinction carried practical consequences. The importing company argued that the requirement from an authority that lacked legal power was a nuisance that must be declared void, without the need of proving any further harm.Footnote 45 By contrast, the panel took a more harm-oriented (and perhaps common law) approach.Footnote 46

The courtesy translation of the panel decision in Urea from USA and Russia is a rich source of mistranslations. This raises questions regarding the extent to which a poorly done translation could hamper the ability of English speakers to comprehend the details of the reasons for the decision and to what extent that matters (i.e. if they agree with the decision and the explanation provided for that decision by the Mexican panelist(s) that writes the decision). The translation refers to concept of standing in ‘our legal systems’ (the use of the plural could be a typo, but is misleading nonetheless, since it implies that the concept of standing is shared across legal systems). An example of an incomprehensible translation is ‘hypothetic dispense of the countervailing duty’. Rather crucially, the translators keep translating ‘cuota compensatoria’ as countervailing duty, but it should be antidumping duty in English.Footnote 47

The latter error provides an example of an intralinguistic difference causing a mistranslation into English (Mexican law refers to cuota compensatoria as an all-inclusive term for countervailing duties and antidumping duties, whereas other Spanish-speaking countries use separate terms, as do the authentic Spanish legal texts of the WTO). When the case involves antidumping duties and the translation refers to countervailing duties, it is a serious translation error.

In the Review of Final Determination of Antidumping Duties imposed on imports of Ethylene Glycol Monobutyl Ether from the USA,Footnote 48 the Panel invoked a Mexican precedent about the burden of proof of injuries in ‘constitutional controversies’.Footnote 49 However, this term is another false cognate. In Mexican law, constitutional controversies constitute a special procedure to solve conflicts regarding federalism or separation of powers between two state actors, not a dispute between private actors and a state agency. Once a lawyer understands the technical meaning of this term, she may distinguish the precedent and point to other decisions that contradict the position of the Panel.Footnote 50 Inadequate translations can undermine a lawyer's capacity to effectively argue the case.

This linguistic asymmetry also may impede efficient communication among panelists. For instance, in the case Imports of Carbon Steel from the US,Footnote 51 panelists discussed the Spanish and English versions of Article 5.10 of the Antidumping Agreement, which state:

Salvo en circunstancias excepcionales, las investigaciones deberán haber concluido dentro de un año, u en todo caso en un plazo de 18 meses […]. (emphasis added)

Investigations shall, except in special circumstances, be concluded within one year, and in no case more than 18 months […].

According to the majority (3 Mexicans and one American) the Spanish version was more lenient.Footnote 52 Because the Spanish version starts with ‘exceptional circumstances’, they suggested it provided deference and flexibility for the investigating authority to carry out the investigation in a longer period of time. However, Dale P. Tursi, an American of Italian descent, dissented on temporal grammatical distinctions. He observed that the majority disregarded that ‘deberán’ was a future-indicative expression, not the more relaxed future-conditional suggested by the majority. While all the panelists agreed that the investigating authority failed to issue the determination on time, the majority considered the defect harmless.

What is the impact of linguistic asymmetry? First, the Spanish–English comparison is arduous, if not impossible, for a monolingual lawyer. Second, linguistic abilities interact with legal ones. The fluency of a bilingual judge may provide not only the technical skills for the comparison but also the cultural sensibility to link linguistic insights with legal concepts. ‘Deberán’ indicates an almost absolute duty, a command that, when unfulfilled, produces a harm. Tursi's acquaintance with Spanish, together with his common-law knowledge on torts, puts him in a privileged position. He detects what a monolingual lawyer misses, but he also employs an expansive conception of harm than bilingual civil lawyers may not fully appreciate. In brief, bilingualism is a necessary but insufficient condition to be a competent cross-cultural panelist.

4. Differences in Legal Traditions and Legal Cultures

On the surface, Canada, Mexico, and the US agreed to the same set of rules in the NAFTA. However, those rules are translated into three different languages, implemented as domestic law in two different legal traditions (common law and civil law), administered by different domestic institutional bodies, and interpreted through different cultural lenses. At the end of this process, it is difficult to see how the end product in one legal culture could be the same as in the others. In short, we are not really playing by the same rules, because we interpret and apply those rules in distinct ways.

How do we bridge the gap between our legal cultures and legal systems? Once the NAFTA created a unified market, it was necessary to develop a shared legal understanding. The convergence between the common and the civil law tradition can be achieved, as John Merryman noted, by at least three strategies.Footnote 53 First, by the harmonization or unification of legal texts among diverse jurisdictions. Second, by the transplantation of legal rules from one jurisdiction to the other.Footnote 54 Finally, by ‘natural convergence’,Footnote 55 i.e., the shared interests among jurisdictions may prompt the development of a ‘modern’ or global legal cultureFootnote 56 formed by general patterns, communal beliefs, and attitudes across jurisdictions.

We conceive the binational panel a promising yet improvable mechanism of transnational legal engineering to achieve a shared legal language, without minimizing differences among Canada, Mexico, and the USA. The harmonization of texts is, at best, superficial. It is one thing to amend a text; it is quite another to grasp, interpret, and apply it through new legal and linguistic lenses. Legal transplants also have been questioned as a kind of legal imperialism or, at least, as culturally insensitive.Footnote 57 The binational panel recognizes the limits of reforming texts and instead proposes, at least in theory, a horizontal, bijural, and plulinguistic body that transcends political borders. The binational panel is a cross-cultural body that adjudicates cases in light of domestic law.

For the most part, Canada and the United States operate in English and follow the common law legal tradition (with French and civil law not necessarily relevant to judicial review of federal administrative action.) However, even between two very similar countries, there are differences in their legal cultures, which produce different approaches to similar legal issues.

In the report of the Extraordinary Challenge Committee (ECC) under the United States–Canada Free Trade Agreement, Certain Softwood Lumber Products from Canada, the spirited dissent of Judge Malcolm Wilkey sets out several concerns regarding potential frictions between legal systems in Chapter 19 judicial review.Footnote 58 Judge Wilkey expressed concern that misapplying the standard of review, which would be grounds for the ECC to overturn the panel decision, was a likely outcome of having foreign lawyers providing judicial review of US agency action in trade remedy cases. He noted the importance of legislative history in US statutory interpretation, in contrast to its minor role in Canadian and English law. He criticized the Canadians for ignoring relevant Senate and House Committee reports in this regard.Footnote 59 In particular, Judge Wilkey complained that the panel had not shown sufficient deference to US agencies, and that this was an example of misapplication of the standard of review, which requires greater deference by US courts. He criticized the panelists for being experts in trade law, rather than experts in the field of judicial review of agency action, which meant that they do not have adequate familiarity with the standards of judicial review under United States law, particularly in the case of the Canadian members. In his view, the Binational Panel is ill-prepared for the role of a generalist judge reviewing the work of an administrative agency, to whose expertise he has been accustomed to giving deference. Moreover, he argued that there is no way to educate such persons on the US standards of judicial review of agency action, particularly the Canadian members.

Judge Wilkey suggested that there are only three ways to become an expert in the matter of judicial review of administrative agency action, over a period of years: (1) arguing cases before a reviewing court; (2) teaching courses in administrative law; or (3) sitting on one of the reviewing courts itself. In addition, since the ECC replaces in the hierarchy a Court of Appeals composed of experts on judicial review of administrative agency action, but is composed of former judges, there is no way for Canadian members of the ECCs to become immersed in the standards of judicial review of agency action in the United States. Canadian administrative law is different, Canadian review standards are different, and Canadian members necessarily do not have the same familiarity with US standards of review that US members do. They are therefore not qualified to apply US law, in his view.Footnote 60

Judge Wilkey rejected the notion that having the expertise to show less deference could be justified as one of the purposes of having expert binational panels. He criticized Justice Hart's view that the Chapter 19 system may reduce the amount of deference which can be paid to the US agencies and that this was intended. In Wilkey's view, this would violate the agreement that the standard of appellate review in each country would remain the same. In Wilkey's view, this implied that two different bodies of US law, in both substance and procedure, would emerge: one based on Binational Panels and ECCs under the CUSFTA (later NAFTA), and another applied to imports from all other countries, based on a more deferential standard of review in US courts.Footnote 61

Finally, Judge Wilkey predicted that, if this was a problem in judicial review between Canada and the United States, two common law countries with similar legal traditions and antecedents, it would be worse with Mexico becoming a third member of NAFTA. In Judge Wilkey's view, Mexico has no legal system or traditions in common with the United States whatsoever, since it is a Civil Law country. In his view:

Mexico ‘has no mechanism and no concept of judicial review of administrative agency action; it has only the much abused and discredited ‘amparo’, or flat prohibition against an official act being carried out. If Canadians on the Panels and ECCs have failed - as in my judgement here they have - to comprehend the United States standards of judicial review of administrative agency action, what can we expect from lawyers and judges schooled in the Civil Law?Footnote 62

Judge Wilkey's views on Mexican law are rather exaggerated. Indeed, Mexico's use of legislative history as a method of statutory interpretation is arguably closer to the US practice than that of Canada. Moreover, his characterization of the concept of ‘amparo’ is plainly wrong. Nevertheless, Judge Wilkey's 1994 dissent raised the kind of concerns that we set out to address in this article, and therefore it seems a good starting point for the consideration of the issue of how to address these types of frictions between legal systems and legal cultures.Footnote 63

An alternative to Wilkey's approach is a more culturally sensitive but still a functionalist one. Dale P. Tursi, the dissenting panelist in Carbon Steel, set the outline of this approach. Tursi argued, in fact, that the binational panel of the CUSFTA ‘arose from the necessity of Parties to bridge an impasse over the harmonization of domestic trade laws’.Footnote 64 He argued that panelists must be acquainted with the foreign law that they interpret. He claimed that panelists must understand the purpose of Chapter 19, which requires a ‘functionalist understanding’ of the standard of review, the domestic legal framework, and their interaction.Footnote 65 According to him, the role of panelists is closer to that of domestic judges rather than arbitrators. Panelists should give weight to domestic sources, including the Mexican notion of jurisprudencia, legal principles, and the national constitution, as a Mexican judge would.Footnote 66

However, although Tursi agreed that ‘ilegalidades no invalidantes’ (‘non invalid illegalities’) was the equivalent to the US notion of ‘harmless error’, he failed to make explicit his functionalist methodology. As previously discussed, the issue in Carbon Steel was whether a delayed resolution was a harmless error. One can argue that the errors of state agencies that do not cause harm must not invalidate the final resolution. However, the relevant question is whether common law, and civil law panelists share the same understanding of ‘harm’. A panelist committed to legal certainty may argue that the agency's delay is a harm in and of itself because companies are not able to ascertain their obligations within the time set out in the Antidumping Agreement. In contrast, another panelist may argue that an expectation to have no delays is not a protected interest. Similar to the issue of ‘nuisance’, the lack of a transparent functionalist methodology that established a common ground between panelists affected the outcome of the case.

A more culturally sensitive and rigorous methodology is needed. This methodology may be centered on core or overlapping values and goals shared by the countries which can be protected or achieved by different legal institutions across the three jurisdictions. This methodology should be able to overcome misperceptions about foreign law and permit a better understanding of the degree of commonality between domestic and foreign legal concepts.

The application of NAFTA Article 1904 is particularly challenging. It states that:

The panel shall apply the standard of review set out in Annex 1911 and the general legal principles that a court of the importing Party otherwise would apply to a review of a determination of the competent investigating authority.’ (italics added)

Interpreted in isolation, Article 1904 is ambiguous.Footnote 67 The degrees of similarity of standards of review may be affect the likelihood of predictable outcomes or affect the coherence of legal reasoning. However, Article 1904.8 indicates that panels lack the power that domestic courts have: panelists are not empowered to declare the absolute voidness of an agency decision. Moreover, this mechanism replaced domestic judicial review and opted for binational panels applying domestic standards of review, not a treaty-mandated standard of review like the one set out in the WTO Antidumping Agreement. While Chapter 19 panels cannot reach outcomes that are identical to those of domestic courts, they must apply the standard of review as domestic courts would by following an analogous procedure and invoking similar legal reasoning.

Perhaps panelists intuitively grasp the foreign law and practice by understanding it through the filter of their understanding of the comparable concept in their own law. Common law lawyers may understand civil law nullity through the lens of common law voidness, or address the relationship between the executive branch of government and the judiciary in Mexico in light of the US doctrine of judicial deference to federal agency decisions. However, this approach creates what we call the intuitive functionalist paradox. On the one hand, as decision-makers, they ought to justify the methodology to identify similar legal institutions transparently. On the other hand, they may understand and analyze the law intuitively as something self-evident that does not require explicit justification because they operate automatically after years of legal training.

The challenge of intuitive functionalism is twofold. The first is the role of the panels. For instance, in Chicken legs, the panel considered that its role has ‘some degree of equivalence with the Federal Court of Fiscal and Administrative Justice’.Footnote 68 The Panel was asked to dismiss a petition because a party has initiated domestic proceedings, in addition to the binational review proceedings. The panel held that ‘it cannot be thought that [the Federal Fiscal Court] could deny a plaintiff access to a nullity procedure when the applicant has submitted a constitutional procedure (Amparo) with the corresponding constitutional court’.Footnote 69 However, what is the methodology that the panelists followed to ascertain the equivalence between courts and panels? It is unclear how panelists determined that ‘it cannot be thought’ that the domestic court could have acted differently. Possibly the panelists are correct, but they fail to provide an explicit methodology, perhaps precedent-based, for predicting how a domestic court would act.

The second challenge is the cross-cultural and bijural analysis of specific, functionally equivalent, legal ideas. In addition to the issue of harmless error discussed above, in several cases the panelists equate the common law concept of standing with the civil law concept of ‘legitimación procesal activa’ or juridical interest.Footnote 70 If the American panelists use the courtesy translation, they would equate the two concepts, unless corrected by the Mexican panelist who wrote the decision in Spanish. Can the ‘binational’ panel really be binational if the panelists from one legal system/language rely on the panelists from the other legal system/language in such situations?

In this process, lawyers deploy, usually unconsciously, what we call legal shortcuts. These cognitive shortcuts allow them to translate foreign legal ideas to their language, culture, and system.

In the Urea case, the Panel rejected the investigating authority's termination of the investigation for ‘lack of subject matter’ based on the lack of legal standing as plaintiff (‘legitimación procesal activa’) of AGROMEX. The Panel reasoned that the legal institution of legal standing as plaintiff (‘legitimación procesal activa’) may not be applied within administrative proceedings.Footnote 71

Mexican law operates in the background of Mexican lawyers’ minds. They understand common law standing through the filter of their understanding of Mexican law. They may understand standing as legitimatio ad causam linked to the historical civil law dichotomy between subjective entitlement and objective law.Footnote 72 Not every violation of objective law entails a subjective entitlement justiciable before the courts. However, if the case were decided today, Mexican lawyers would also have in mind the broader understanding of legitimate interest. This is not a violation of a subjective right but a violation of objective law that indirectly affects individuals, entities, or collectivities. That is, it entails a non-exclusive harm as understood in Amparo and administrative law in light of recent reforms and as developed by the Mexican Supreme Court.Footnote 73 Is this completely analogous with the predominant US notion of standing?

Similarly, American law colors an American lawyer's perception. They would understand standing at the binational procedure as they conceive it in their domestic courts. They could assume that plaintiffs must prove a recognizable injury, causation, and redressability as developed by common law courts, and, particularly, the United States Supreme Court.Footnote 74

Are Mexican and common law lawyers discussing the equivalent concept in their respective jurisdictions or are they missing important differences? By contrasting both understandings, they may discern whether both institutions are sufficiently equivalent as to count as one and the same. If so, they could discuss if the institutions need to be tailored to the context.

One salient example of a legal cultural barrier is the Mexican institution of jurisprudencia. This term has a very technical meaning in Mexican Law. Jurisprudence in other civil law jurisdictions usually refers to a line of decisions from superior courts with persuasive, rather than binding value.Footnote 75 While Mexican jurisprudencia is similar to the civil law conception, it has a very unique meaning.Footnote 76 Jurisprudencia refers to a legislative doctrine of weak binding precedent.

According to the Amparo Act, there are three ways of producing binding precedents or jurisprudencia for inferior judicial bodies. The first is reiteration: a line of five decisions from the Circuit Courts, Chambers of the Supreme Court, or the Full Court, voted by special majorities: unanimity at Circuit Courts, four out five Justices in Chambers, and eight out of eleven in the Full Court. The second is ‘contradicción de tesis’: when two or more Circuit Courts issue conflicting decisions, the Circuit Plenary or the Supreme Court, by a simple majority, decides the criterion that must prevail. The third is substitution: after applying a binding criterion from a superior court, Circuit Courts, or Chambers of the Supreme Court, the relevant court may suggest to the author of the precedent to abandon its criterion for future cases, provided that a special majority approves the substitution of criterion. Otherwise, a decision is merely persuasive, not a binding precedent. For instance, four judgments of the Supreme Court voted by a unanimous Full Court are not a binding precedent for any court in the nation, unless and until another supermajority decides the fifth case. This complex legislative regulation of jurisprudencia stands in sharp contrast to the notion of vertical precedent in the common law, in which a decision from a superior court is binding on inferior courts.

One of the most peculiar aspects of jurisprudencia is the ‘tesis’. Tesis are a kind of official rationes decidendi that the same court that solved the case selects to publish in the official Gazette of the Federal Judiciary.Footnote 77 Tesis are the written expression ‘in abstract terms, of the legal criterion laid down when deciding a case’Footnote 78. The Supreme Court Rule that regulates the tesis, a 75-page document, states that these must be so clear that they can be understood without ‘resorting to the written judgment’.Footnote 79

The courtesy translation in the Urea case refers to a ‘judicial precedent’ in Mexican law.Footnote 80 However, the concept of jurisprudencia in general, and of tesis in particular, clashes with predominant approaches to precedent, the ‘hallmark’Footnote 81 of the common law. A first-year common law student might struggle to master the skill of identifying a ratio decidendi, but would find jurisprudencia much odder, to say the least.Footnote 82 Another unfamiliar aspect is that tesis deprives precedents of factual context, which is a key element to understanding the reasoning behind the ruling in common law.Footnote 83

A standard Mexican judgment is lengthy and full of references to tesis, but panel resolutions do not cite as many tesis as the domestic equivalent would. For instance, in a 146-page judgment from a Mexican international trade court there are thirty tesis cited on matters of conflicts of jurisdictions, evidence, procedure, and substantive law.Footnote 84 In contrast, in Bovine Beef and Eatable Offal,Footnote 85 the panel wrote a judgment of eleven pages and cited only one case. In Chicken Legs,Footnote 86 a 150-page decision, the Panel only analyzed five tesis.Footnote 87 This comparison shows the importance of tesis in Mexican law. However, it is unclear how a binational, bicultural, bijural panel deals with this distinctively Mexican institution. Are panel decisions a coherent hybrid of two legal traditions and the product of a respectful cross-cultural dialogue? Or are they merely a ‘literal’ translation?

How do common law lawyers read, understand, and use the Mexican tesis and jurisprudencia if they do not read Spanish? Do they trust the Spanish–English translation? Moreover, how do common law lawyers understand the use of jurisprudencia? The reasoning process is very different from using common law precedents. Applying a statutory provision may be similar to apply a Mexican tesis, but what about following a precedent? The latter seems to suggest that the subsequent case adds something to the precedent being followed, increasing its force. Is following a precedent akin to expanding a statutory rule through analogical reasoning or is it a more fact-oriented activity?Footnote 88 A common law lawyer also tends to distinguish precedents in order to avoid following their reasoning or conclusions, a form of reasoning that tends not to occur in the Mexican system.

Two early binational panel decisions provide an excellent example of contrasting approaches to the use of precedents when addressing the same legal issue of whether a binational panel has the jurisdiction to annul the decision of the investigating authority.Footnote 89 Both reach the same conclusion that a binational panel does not have the power to annul the decision of the investigating authority, because the standard of review is limited to article 238 of the Federal Fiscal Code (FFC), thereby excluding the application of FFC article 239.Footnote 90 While the decisions do not indicate the author, they do indicate that the original language of the decision is Spanish (High Fructose Corn Syrup) or English (Flat Coated Steel Products), by indicating whether or not the English version is a courtesy translation. Moreover, the style of legal analysis confirms that the former is authored by a Mexican lawyer and the latter by an American lawyer.

The legal reasoning in High Fructose Corn Syrup reflects a Mexican analytical approach. The decision first notes that the Mexican Constitution requires that rules that grant jurisdiction to an authority be strictly applied (para. 286). This is followed by a lengthy explanation regarding the sources of Mexican law, before proceeding to thoroughly analyze the legal basis for the panel's jurisdiction to review the investigating authority's response to a WTO ruling. No cross-cultural legal issues arise explicitly, but there appears to be an implicit reliance on the Mexican lawyer who wrote the decision to get the Mexican law right.

To what extent does the tribunal's approach to writing the decision influence the impact of cognitive shortcuts in legal reasoning? There are no rules regarding how an arbitral tribunal operates in this regard. It differs from tribunal to tribunal. Arbitrators can agree to divide up tasks (especially if they are very busy with their own legal practice for example), circulate written drafts to each other, and then comment on the drafts. Alternatively, they might first engage in a collegial discussion, then circulate a draft, and then provide comments. Another approach is to have a discussion in which they identify key issues and share preliminary views, and then prepare written drafts to exchange among themselves for comments. Another approach is to assign one member of a tribunal to write the decision and then circulate it to the others, at which point they can decide whether to agree, concur, or dissent. In general, it is useful to work out ideas in written drafts and then test the legal reasoning by receiving comments and having discussions. Indeed, writing is part of the deliberative process and serves to test one's reasoning, particularly in complex cases.Footnote 91 In that regard, it is not that different from the process of co-authoring an academic article and taking it through the peer review process.

There are no set rules regarding the writing process for Chapter 19 panels either. The Chapter 19 process does not mitigate or determine the effect of cognitive filters on the panel's reasoning. In fact, it is the other way around. The legal/cultural/linguistic filters of the panelists determine the process that the panel will follow. Each panel decides its own process, one that fits the profiles and personalities of the President and the other panelists. For example, the President can choose the process in consultation with the other panelists. He might choose to distribute tasks among panelists and have his team research the same tasks in parallel. He can then review all the drafts and use the collective input to write the decision. This approach can help to harmonize the distinct approaches of panelists with very different backgrounds, but it is the very fact of the diversity of panelist backgrounds that requires this process. Moreover, a panel with a diverse set of backgrounds benefits greatly from having a President who has expertise in both common law and civil law.Footnote 92

In Chapter 19 panels for Mexico–US disputes, the working language is most often English, since Mexican panelists are more likely to have an adequate level of English than for American panelists to have an adequate level of Spanish. When a panel is composed of practising lawyers and academics, one practice is to assign the writing of the first draft of the decision to the academic, who has more time to work on it. The draft is then circulated for comments to the other panelists.Footnote 93

The decision in Flat Coated Steel Products reads completely differently from HFCS in style, substance, and approach, including an effort to consult the amparo decisions of Mexican courts, very much in the way that a common law lawyer would do. In contrast, in HFCS the focus is on the Mexican Constitution, statutes, and the civil code, which looks more like the approach of a civil law lawyer. Before the Flat Coated Steel Products panel addresses the applicability of FFC article 239 (paras. 44–48), the panel's approach to prior case law is enlightening. The panel distinguishes all tribunal decisions, both in domestic Mexican law and Chapter 19 panels, and thus avoids the type of lengthy discussion of Mexican law found in HFCS. As we noted above, distinguishing ‘precedents’ is a common law practice that tends not to be used in Mexican law. The panel concludes that Mexican amparo cases do not provide clear guidance, and that previous Chapter 19 panel decisions provide guidance but are not binding.

The Flat Coated Steel Products panel applies a principle of international law to strictly limit panel jurisdiction (para. 23.), in contrast to HFCS case, where the panel used Mexican law for the same end. The Flat Coated Steel Products panel bases their approach on cases on an arbitration panel's jurisdiction, referring to the arbitration agreement, then uses NAFTA as the arbitration agreement in this case.Footnote 94 This approach permits the author to avoid having to deal with domestic Mexican law, other than to discount its relevance to the issue. Instead, the decision refers to International Court of Justice case law regarding the consent of States (para. 25), then notes that treaties are part of Mexican law under the Mexican Constitution (para. 28). This justifies a focus on international law. To distinguish domestic case law, the panel states that it is unaware of any tribunal decision interpreting ‘administrative determination’ in art 238 in the context of a dumping investigation. They then base their decision on the NAFTA text and the text of article 238.

A similar lack of cross-cultural deliberation is found in Ether. Footnote 95 The judgment starts by stating that state acts must be challenged by the proper ‘remedy’, namely, ‘appeal for reversal’ (recurso de revocación). However, ‘remedy’ in the common law is understood as the judicial relief to protect a right, not the process to review a decision. Even if a civil law notion like recurso is usually translated as ‘remedy’, both ideas suggest distinct practices. In the common law, ‘appeal’ is the mechanism that may redress the harm by the remedy of reversal. However, at least in private law, there is an array of remedies developed by common law courts in a case-by-case approach. In contrast, for the civil lawyer, ‘the concept of remedies remains a mystery’.Footnote 96 Common law remedies are court orders such as economic damages or injunctions. In contrast, civil law recursos are procedures to challenge an administrative or judicial decision. In particular, the recurso de revocación is a procedure to be filed before the Ministries of Finance or Economy to reconsider decisions of the executive branch without seeking judicial review before a court. Did common lawyers understand the nature of the recurso de revocación? Does it make sense for a common law lawyer that administrative agencies are empowered to reverse their own decisions when the company file a recurso de revocación without any court oversight?

This decision reveals another challenge for cross-cultural litigation. This decision starts by noting that the petition provided ‘valid legal syllogisms’Footnote 97 about legal errors. It then proceeds to engage in justification under an apparently deductivist approach. After reconstructing each of the arguments as part of a syllogism, the panel infers to individual conclusions that ‘follow necessarily’Footnote 98 ‘from the reasons stated above’.Footnote 99 Could a common lawyer reject the ‘deductivist’ civil law drafting style and advocate a more transparent discursive approach or would such a position be received as an example of cultural-insensitivity or arrogance?Footnote 100 In any case, it is difficult to imagine how a unilingual common law lawyer could truly understand the reasoning of a fellow panelist in this context.

5. Shortage of Cross-cultural Panelists

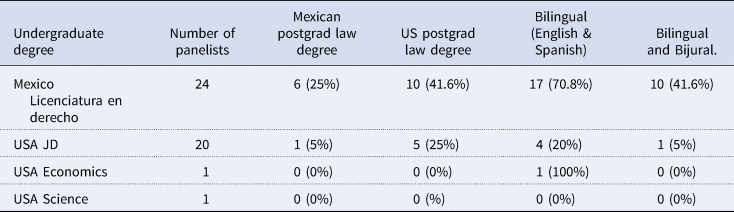

We researched the profiles of 46 out of the 48 panelists from the 15 cases in which Mexico was a responding party. Few Chapter 19 panelists are experts in both the common and the civil law. Several of the Mexican panelists are acquainted with US law, but few US panelists are familiar with Mexican law. There are a few Mexican-Americans who studied law in the US but have interests in their legal ‘roots’ and a few other common law lawyers who have studied and published about Latin American law.

Regarding their degrees, most of the panelists hold either a JD in the common law (21) or a Licenciatura in the civil law tradition for Mexicans (24). No panelists had both a JD and a Licenciatura. Only one was licensed in both jurisdictions, a Mexican law graduate with an LLM from Harvard who is licensed to practice in Mexico, federal courts in the US, and the State of New York.Footnote 101 None of the American lawyers was qualified to practice law in Mexico. In addition, one panelist was an economist and another holds a Bachelor in Science with an MBA in International Finance.

However, several panelists strengthen their credentials with postgraduate degrees.Footnote 102 Twenty-two panelists studied master's degrees. It is more common for Mexicans to study a postgraduate degree (15) than for Americans (7). Ten panelists studied Comparative Law or International Law degrees or diplomas, and five studied a degree or diploma in the domestic law of the foreign country. Several Mexicans pursued post-graduate studies in the US, but only one American had a JD, from Connecticut, and a Maestría en Derecho from Universidad Iberoamericana.Footnote 103 This leaves us with less than one-half of panelists with formal training in both jurisdictions. A common lawyer trained in the civil law is practically an eccentricity.

The asymmetry is greater regarding bilingualism. As a general rule, it is rare to find profiles of American lawyers who are bilingual (English–Spanish). Furnish, Gantz, Gordon, Hayes, Miranda, Reyna, Santos are exceptions. Furnish not only co-authored a paper about the Law of Latin American countries from a common law perspective,Footnote 104 but also, according to his CV, wrote a book on Mexican Law.Footnote 105 Santos, perhaps because of his Latino heritage, is trilingual.Footnote 106 Reyna, now a judge of the United States Court of Appeals, is another example: a former president of the Hispanic National Bar Association, founder of the Hispanic Culture Foundation, and even an Ohtli Award recipient.Footnote 107 Only six American panelists out of 23 have explicit bilingual credentials. In contrast, at least 18 Mexican panelists have at least bilingual credentials. Of these, Cuadra is trilingual,Footnote 108 Herrera-Cuadra is a polyglot and a specialized translator,Footnote 109 and Estrada is also a polyglot, and a promoter of multiculturalism and multilingualism.Footnote 110

Table 1. Bilingualism and Bijuralism at the NAFTA Panels

Source: Data collected by authors.

Based on this research, we developed a typology of cross-cultural adjudicators useful to determine the nature of the challenges that they face when working in a bijural and bilingual environment. The first three are positive indicators of capacity to operate in this environment, while the fourth is a negative indicator.

5.1 Adequate Knowledge of International Trade Law and Trade Remedies

NAFTA Annex 1901.2 only requires ‘general familiarity with international trade law’, rather than expertise in trade remedy law specifically. However, a central purpose of NAFTA Chapter 19 was to replace judicial review by judges, who would be unlikely to have expertise in trade remedy law, with panelists with expertise in this field, whose expertise would make them more able to question the decisions of investigative authorities.

5.2 Adequate Knowledge of Their Own Legal System and Legal Culture

The majority of the panelists that we examined would be familiar with their legal system because of their JD or LLB degrees. However, that does not guarantee expertise in trade remedy law.

5.3 Adequate Knowledge of the Foreign Legal System and Legal Culture

Lawyers who have pursued a diploma or degree in comparative or in the domestic law of a foreign country may become better acquainted with the foreign law. Alternatively, a panelist can become acquainted with the foreign law by practicing law abroad. However, our research shows that this is uncommon.

5.4 Lack of or Insufficient Knowledge of the Foreign System

This is could be the case for unilingual lawyers, with no training in the other legal system, who also lack a sufficient degree of cultural immersion.

6. Conclusion

Do the preceding issues represent a design or an implementation problem? We argue that it is both. It is a design problem, to the extent that the very concept of the binational, bijural panel creates challenges for the translation of legal concepts in a way that a foreign lawyer can fully understand. However, in other respects, it is an implementation problem; choosing better-qualified panelists and translators would reduce the degree of problems encountered. However, choosing better qualified panelists and translators will not eliminate linguistic issues. Even in the WTO, which has perhaps the most highly qualified translators in this field of law, challenges still arise.Footnote 111 Moreover, the WTO Secretariat employs highly qualified and multilingual lawyers to assist dispute settlement panels and the Appellate Body, whereas the NAFTA lacks this kind of Secretariat support for its panels. In this regard, the absence of a permanent, professional team of lawyers to support the work of panels could be viewed as a design flaw, although how panelists choose their assistants would be an implementation issue. Regarding the use of terminology, greater use of definitions could help, as it has in the multilingual context of the European Union.Footnote 112

This paper reconceives the role of panelists as comparatists/practitioners. Panelists do not propose different understandings of shared legal ideas or suggest reforms of domestic law in light of foreign law, as academics would. Moreover, unlike domestic judges, where the use of foreign law is non-mandatory, panelists must be educated in foreign and domestic law. Panelists must solve foreign legal disputes as if there were their own. In a more general sense, this paper is a step towards the better design of cross-cultural, multilingual, and pluri-jural courts and tribunals in the age of globalization and pluriculturalism.

As we have shown, binational panels face a threefold challenge. First, they face a linguistic barrier. Translation of statutes or judgments always implies choices made between potential meanings. These linguistic decisions may affect the outcome of cases. Second, panels face a legal culture/legal system barrier. Lawyers deploy, usually unconsciously, what we call legal shortcuts. These cognitive shortcuts allow them to translate foreign legal ideas to their language, culture, and system. However, panelists fail to make explicit such shortcuts, which impedes the transparent comparison of apparently similar legal ideas. Third, as a consequence of the first two challenges, panels face a professional shortage barrier. Most panelists are acquainted with the common law and speak and read English because of legal practice (in the case of American panelists) or foreign postgraduate degrees (in the case of Mexican panelists). Nevertheless, this familiarity is asymmetrical regarding the civil law and Spanish, where few American lawyers are likely to have much knowledge and experience.

In this way, we have signaled drawbacks in contemporary roles and understandings of binational panels but also identified potential solutions for cross-cultural adjudication. The increasing dialogue and interconnection between different countries and legal traditions can profit from these insights. More cultural immersion is needed among panelists or judges. However complete immersion among lawyers and total convergence between jurisdictions is impossible. Moreover, as Christoph Winter notes regarding the effect of cognitive biases in tribunals, ‘judicial decision-making is unlikely to become flawless based on natural intelligence.’Footnote 113 Indeed, we are not advocating the pursuit of the perfect panelist, since that is unrealistic. However, we do believe that improvement is possible, particularly given increasing opportunities for lawyers in the NAFTA countries to pursue double degrees in common law and civil law.Footnote 114 There is a mismatch between economic interdependence and the potential of bijural education, on the one hand, and the design and implementation of Chapter 19, on the other. Indeed, our message is as much for law schools as it is for governments who choose panelists to serve on Chapter 19 panels.

We have empathy for the difficult task that panelists face, based on our own experience writing this paper. It is not easy to express foreign legal concepts in a different language in a way that lawyers from a different legal system can understand, especially when trying to avoid a distortion in the meaning of the concept. In our case, it has proved to be a challenge, even though we both are bilingual and bijural. We can only imagine the challenges that a unilingual and unijural lawyer would face. Perhaps the binational panel system is simply asking too much in this regard. Further exploration of that question remains a fruitful area for further research. Another fruitful line of inquiry for future research could explore how panelists reach interpretative agreements among themselves.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge ITAM and the Asociación Mexicana de Cultura for their generous support of this research. The opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of the WTO. We thank our ITAM colleagues for their helpful comments on earlier drafts: Tatiana Alfonso, Micaela Alterio, Amrita Bahri, Raymundo Gama, Juan González Bertomeu, Mauricio Guim, Alberto Puppo, Alejandro Rodiles, Gabriela Rodríguez, Guilherme Vasconcelos, Eugenio Velasco, and Christoph Winter. We are also grateful for helpful comments from Sungjoon Cho, Yang Liu and Vera Korzun at the American Society of Comparative Law 2019 Annual Meeting and Works-in-Progress Conference. We are especially grateful to our interviewees: Carlos Bernal, Jorge Miranda, Gabriela Rodríguez, and Todd Wetmore. Last, but not least, we thank the referees at World Trade Review for their very helpful comments, which contributed a great deal to improving this article