1. Introduction

The value of preferential access schemes by the main purveyors of preferences, the EU and the US, has eroded over the years: the lowering of most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs, extension of preferences by the EU and US to more countries, unpredictability often compounded by complicated origin requirements to qualify for preferential access. Against this trend, three changes to origin requirements have sought to restore market access. In 2001, under the Africa Growth Opportunity Act (AGOA), the US announced that certain AGOA beneficiaries would satisfy the origin requirement for apparel under a minimum domestic content (i.e. fabric could be imported from third countries). This ‘single transformation rule’ was also adopted by the EU for Everything but Arms (EBA) beneficiaries in 2011. And, at the WTO ministerial in Nairobi in 2015, for non-reciprocal preferences for least-developed countries (LDCs), it was stipulated that preference-granting members shall consider allowing the use of non-originating materials up to 75% of the final value of the product.

Have these changes arrested the erosion of market access under preferential schemes? Market access is again at stake with the EU/friends of Jordan initiative to the Syrian refugee crisis that has resulted in Jordan hosting about 1.47 million Syrian refugees accounting for nearly 20% of the population by 2015. A relaxation decision (decision No.1/2016) based on Rules of Origin (RoO) requirements allowing, among others, for non-originating fabric in T&A was announced for a period of ten years in July 2016 for selected products produced in selected zones. Market access for Jordanian exports to the EU would be improved by moving to a single transformation rule in the EU–Jordan Association Agreement (the EU–Jordan FTA, henceforth EUJFTA). The decision states that it aims at creating 200,000 job opportunities for Syrian refugees.

This paper is primarily concerned with the likely effects of this initiative. We compare Jordan's current utilization of EU-preferences with the utilization of preferences for Jordanian exports to the US under the Jordan–US Free Trade Area (Jordan–US FTA, henceforth JUSFTA), which also benefits from the proposed simplified origin requirement. The paper focusses on Textiles & Apparel (T&A), an important export sector for Jordan and many other developing countries. The paper also adds evidence on the market-access suppression effects of origin requirements in apparel.

The remainder of the paper expands on the Jordanian case study, comparing performance under the EU (EUJFTA) and US (JUSFTA) FTAs (both FTAs were initiated at the same time and followed parallel paths of implementation). Section 2 describes EUJFTA and JUSFTA along two dimensions: extent of preferential market access (taking into account the erosion of preferences for Jordan from other beneficiaries of EU and US preferential schemes) and RoO requirements. Section 3 compares the evolution of EUJFTA and JUSFTA over the ten-year period of implementation before taking a detailed look at the utilization of preferences under both FTAs in 2016. Trade patterns and utilization of preferences have been quite different in view of rather similar preferential access. Size of flows, origin requirements, and competition from other recipients of market access in the EU and the US have all contributed to these divergent outcomes. Section 4 gives econometric estimates that confirm several observations in Section 3: preference utilization rates (PURs) are positively related to preference margins. PURs are lower under EUJFTA due to the double-transformation rule than under JUSFTA where the single-transformation rule applies to apparel. Controlling for preference margins, origin requirements in apparel are independently correlated with PURs. Even though we cannot control for all factors affecting PURs in apparel, the results suggest that allowing for fabric to be imported from third countries to meet the origin requirement would help restore market access for Jordan to the EU and, more generally, contribute to arresting the erosion of market access under preferential schemes.

2. Preferences and origin requirements under EUJFTA and JUSFTA

Jordan is a party to several reciprocal Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). The two most relevant ones for evaluating trade performance are EUJFTA and JUSFTA.Footnote 1 These two FTAs are the most relevant for a comparison both because the EU and the US are ‘similar’ along several dimensions (such as market size, tastes, and income). Also, as shown in Table 3, the EU and the US have markets of a similar size for imports of apparel. Most importantly, the US and the EU are the only countries that report systematically PURs in their respective FTAs (and other non-reciprocal trade agreements). Jordan is also eligible for non-reciprocal market access through the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) that generally gives less market access than FTAs. The GSP is not considered further here.Footnote 2

JUSFTA provided for the elimination of tariffs on all goods and services, excluding tobacco and alcohol, over a ten-year period starting in 2001, starting with the removal of the lowest tariffs. By 2005, tariffs for over 4,000 products, accounting for 96% of all goods imported by the US from Jordan, entered the US tariff-free (Al Nasa et al., Reference Al Nasa's, Chin, Leonard, Munoz and Reilly2008).Footnote 3

EUJFTA came into effect in 2002 with further liberalization of agricultural products in 2007 and a protocol on Dispute Settlement entered into force in 2011. Along with 15 other members, Jordan is part of the Euro-Mediterranean (EUROMED) partnership, a ‘hub-and-spoke’ FTA in which all EUROMED have the same preferential access to the EU for nearly all products (there are a few exceptions for some agricultural products). All face the same RoO requirements, although since December 2016 for a period extending to ten years, certain Jordanian exports face simplified RoO requirements (see below). Additionally, the EU launched negotiations for a Deep and Comprehensive FTA (DCFTA) with Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia in 2011. The DCFTA is to include trade in services (included under the JUSFTA), government procurement, competition, intellectual property rights, and investment protection.

2.1 Preferential margins under EUJFTA and JUSFTA

Preferential margins provide a first measure of potential market access. Figure 1 shows the distribution of two measures of preference margins at the HS8 level: the unadjusted and the adjusted margin. The unadjusted margin is the MFN tariff minus the preferential tariff (usually zero). The adjusted preferential margin, sometimes called the ‘competition-adjusted margin’, subtracts from the preferential margin, the trade-weighted tariff for other recipients of preferences. The adjusted preferential margin for an HS8 product can be negative if some partners pay an MFN tariff at the HS8 level while its main competitors for the product pay less than the MFN tariff. For example, Table 3 shows that China has an unadjusted preference margin of 0.0% in the US for apparel, but an adjusted margin of (–4.0%) because other significant apparel suppliers to the US pay less than the MFN tariff.

Figure 1. Distribution of preferential tariffs for Jordanian products to US and EU (HS8)

Comparing the adjusted and unadjusted distributions in Figure 1 shows that the correction for preferences granted to other recipients widens the difference in tariff shares within most ranges of the distribution. For the EU, the adjusted preferences push the distribution towards the 1%–2.5% range but leave the share of lines with zero tariffs at 25%. For the US, the adjustment raises the percentage of zero preferential margins up to 32% from 25%. Comparing the two adjusted distributions in Figure 1 shows that the EU has somewhat less preferential access to ‘offer’ if one concentrates on the ranges beyond the 5%–10% range. The EU has a lower share of tariff lines with preferential margins in the 10%–15% range and beyond (around 2%–3% vs. 5% of tariff lines for the US).

2.2 Origin requirements under EUJFTA and JUSFTA

All preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) – reciprocal and non-reciprocal such as the Everything-but-Arms (EBA) and GSP – require establishing origin status for exports from a member country in the Agreement to prevent trans-shipment through the low-tariff partner. This is done by the application of rules of origin (RoO).Footnote 4 At the same time, RoO impose costs on exporters (and importers) that have to submit the necessary documents to qualify for tariff preferences. These RoO are typically very complex and often ‘made-to-measure’. The outcome is that the magnitude of these costs is difficult to assess and it is widely documented that the rather large differences in PURs around similar preference margins is a reflection of the differential costs they impose on exporters and importers.Footnote 5

EU and US PTAs use a combination of methods to establish origin. Whereas RoO differ across US FTAs, almost all EU FTAs are based on the PanEuroMed (henceforth PANEURO) System, in place since 2004 (see below). Typically, establishing origin involves the combination of regime-wide rules that apply to all sectors (e.g. a roll-up or absorption principleFootnote 6) and a Change of Tariff Classification (CTC) at different levels (e.g. chapters or headings) across sectors. These can be coupled with a value-added criterion and, in some cases, such as for T&A, a processing requirement.Footnote 7 In the case of T&A, JUSFTA requires minimum domestic content. Unlike most other US FTAs that require a ‘yarn-forward’ (or triple transformation rule),Footnote 8 JUSFTA allows for fabric to be imported from third countries to meet the origin requirement provided that it undergoes substantial transformation.Footnote 9

The PANEURO System, in place since 2004, covers more than 50 countries. It requires a double transformation rule.Footnote 10 Jordan and other Mediterranean countries engaged in the ‘Barcelona process’ operate under the PANEURO RoO requirements. PANEURO allows for diagonal cumulation.Footnote 11 For T&A, the standard allowance criterion that applies across sectors is replaced by an allowance in terms of weight on non-originating materials. Jordan has signed the convention that will extend regional cumulation between EUROMEDs, EFTA/Turkey/EU to the Western Balkans.Footnote 12

The EU relaxation decision (decision No.1/2016) relaxed origin requirements for certain goods produced in Jordan for a ten-year period until 31 December 2026. Products with relaxed rules of origin are listed in Article 2 of the Decision. The list includes petroleum products, fertilisers, some chemical and plastic products, articles of leather, textiles, and apparel. Notably, manufacture from fabric is sufficient to confer origin to Jordanian apparel. This amounts to a temporary replacement of the double transformation rule by a single transformation rule for apparel. The objective being to alleviate the Syrian refugee crisis by creating jobs for Syrian refugees (the decision states that the aim is to create 200,000 job opportunities for Syrian refugees), the decision only applies to goods produced in development zones and industrial areas listed in the decision. In those qualifying zones, the total work force of each production facility should contain at least 15% refugees in the workforce during the first and second years and at least 25% from the third year on.Footnote 13

3. Assessing EUJFTA

The EU and the US entered FTAs with Jordan around the same time, leading to a removal of tariffs over a ten-year period with the largest reduction in tariffs towards the end of the period around 2012. Both also had, or entered, reciprocal and/or non-reciprocal trade agreements with other partners, complicating the assessment of the effects of the two FTAs. This section compares performance under EUJFTA and JUSFTA. Section 3.1 compares the evolution of imports from Jordan over the period of implementation of the FTAs. Section 3.2 then looks at the utilization of preferences at the HS8 level for 2016. Correlates of PURs across partners are then examined in Section 4.

3.1 Trade under EUJFTA and JUSFTA

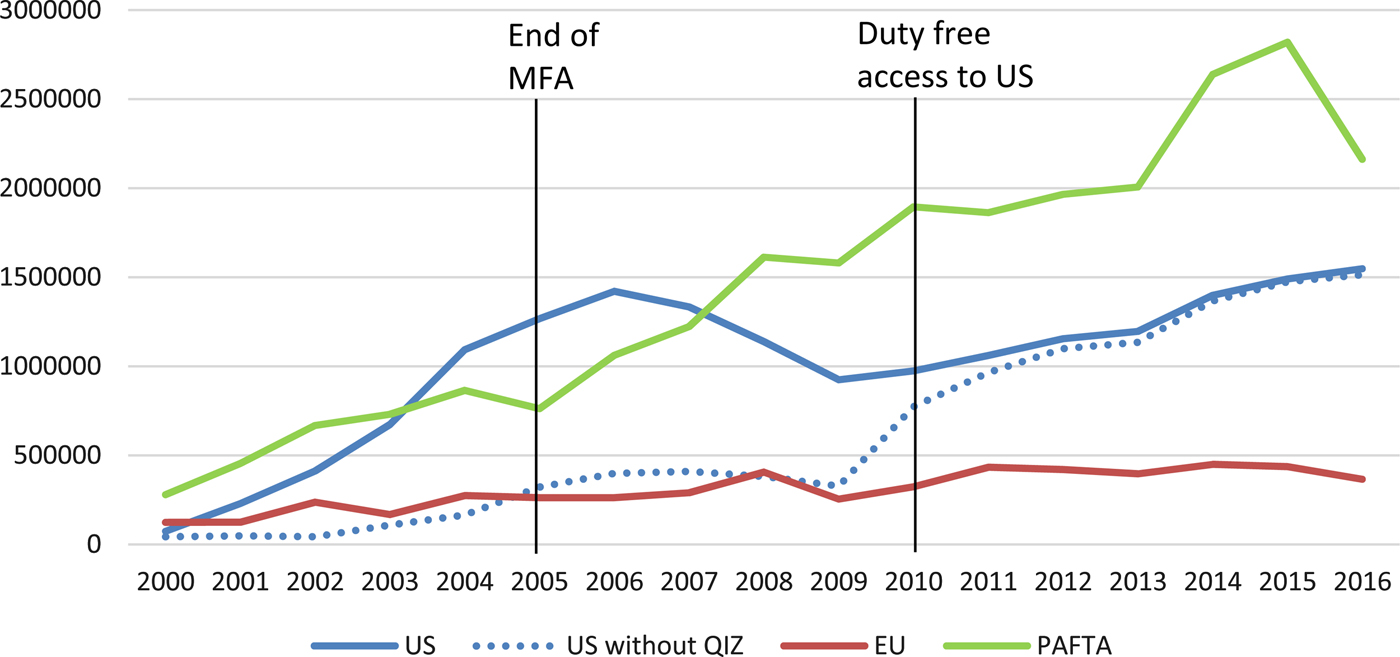

Figure 2 shows the evolution of Jordanian exports to its principal partners with whom it has preferential trade agreements (EUJFTA, JUSFTA, PAFTA). Exports to the EU have started from a low base and have grown more slowly than exports to the other destinations. Exports to PAFTA grew rapidly until turmoil settled in the region starting around 2010 while exports to the US and the EU registered a sharp fall during the 2007–2009 financial crisis. Exports to the US, when inclusive of exports originating from the Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZs) show a sharp increase starting around 2001, the first year of JUSFTA implementation. This is because exports of apparel originating from the QIZs – which have very similar RoO requirements to those under JUSFTA – could enter the US market duty-free from the start, while exports of apparel from Jordan could only enter duty-free starting in 2010.Footnote 14 If one excludes exports to the US from the QIZs, Figure 2 shows that the growth rate of exports is the same for EUJFTA and JUSFTA until 2009. Then, exports from the QIZs contract until virtually disappearing by 2014 but exports under JUSFTA continue to grow while exports under EUJFTA have stagnated over the period 2010–2016.

Figure 2. Jordanian aggregate exports under EUJFTA, JUSFTA, PAFTA (2000–2016)

Annex Figures A1 and A2 give more detail about the evolution of Jordanian exports to the US and the EU in the sectors that account for 90% of exports. For the US, exports are concentrated in the apparel sector. For the EU, the export basket remains far more diversified and only knitted apparel (CH61) appears in the figure. Figures A1a and A1bFootnote 15 confirm that the sharp growth in exports to the US originated from knitted apparel (HS61) and non-knitted apparel (HS62). Together, they accounted for close to 90% of Jordan's exports to the US. Figure A1b shows that exports for these two sectors originating from the QIZs fell sharply starting around 2006 when tariffs on exports of apparel from Jordan started to fall. As mentioned above, US tariffs on apparel imported from Jordan were lifted in 2010. Up until then, Jordanian exports could enter the US duty-free provided that they were declared as originating from the QIZs (and that they satisfied the QIZ RoO requirement). Notwithstanding the end of the Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA) in 2005, the sharp growth in exports from Jordan excluding QIZs that started around 2009 could be interpreted as an approximation of the long-run export supply elasticity to a 10% (margin adjusted) preferential rate under the prevailing RoO requirements. Figure A2 shows that exports to the EU have remained diversified and that preferential access has not resulted in a move towards a concentration of exports to the EU in labour-intensive products, although one observes a growth in the share of knitted apparel (CH61) during the period 2012–2016.

In conclusion, Figures A1 and A2 show that knitted (HS61) and non-knitted (HS62) apparel dominated export growth to the US but are absent from the growth of Jordanian exports to the EU. These different paths partly reflect higher preferential margins in HS61 and HS62 for the US than for the EU, but, as shown below, they also reflect other considerations including greater competition from other preference-receivers on the EU than on the US side and a more lenient RoO requirement under JUSFTA. This greater competition is partly reflected in a larger discrepancy between unadjusted and adjusted margins for the EU than for the US in the textiles and apparel sector. Under JUSFTA, the adjusted preferential margins for HS61 and HS62 are about a third lower than the unadjusted rates. Under EUJFTA, the adjusted rates are about half the corresponding unadjusted rate.Footnote 16 This is not surprising since the EU extended greater (and more lenient) preferences to LDCs under EBA than the US did under AGOA, as qualification was subject to periodic review in the US (see Table 3).

3.2 Preference utilization under EUJFTA and JUS FTA

About 85% of world trade is registered under MFN status, so trade registered under preferential status is small.Footnote 17 Only the EU and the US disclose regularly the use of preferences for imported goods.Footnote 18 Assuming that RoO requirements prevent trans-shipment, in the short to medium term, a high rate of utilization of preferences is the first yardstick to assess the intended effects of any PTA. Three factors are important in accounting for differences in PURs across sectors and eligible countries:

• The depth of preferential access captured by the preferential margin (see Figure 1 and Tables A2 and A3).

• The size of the shipment because of the fixed costs of complying with RoO requirements (Table A4).

• The complexity of RoO requirements (Table 3).

Table 1 compares the aggregate utilization of preferences by tranches of unadjusted (since the PUR depends on the extent of preferences) preferential margins and the import value range for EUJFTA and JUSFTA for 2016. Preference Utilization Rates (PURs) are computed at the HS8 level for products with a positive MFN tariff. The PUR is the share of imports entering under the preferential trade regime that comply with the RoO requirement.Footnote 19 Under JUSFTA, there are no shipments in the first two bin categories of $0–10 and $10–100, but there are some shipments in these categories under EUJFTA. As one would expect, PURs under these small shipment categories are low.Footnote 20

Table 1. Preference utilization rates (PURs) by unadjusted preferential margin and by import value range (2016)

Note: Calculations based on HS8 level data. A blank field indicates no combination in the data.

Source: Eurostat for trade data and TRAINS for tariff data for the EU; USITC for trade and tariff data for the USA.

For the import value ranges with shipments under both FTAs, for each preferential range, the PUR generally increases with the shipment value range, although there are a few exceptions to this pattern for EUJFTA and there are a few instances where the uptake is lower in the 20+ adjusted preferential margin range. This could reflect small shipments. Turn to apparel (HS61 and 62). Under EUJFTA, the preferential margin is in the 10–15% (HS61 and HS62) range, while under JUSFTA, the preferential margin is in the 10–15% range (HS61) and the 15–20% range (HS62) (see Tables A2 and A3). Note that for all import value ranges, the PUR is low in the 10–15% under EUJFTA while, on the contrary, it is high in the corresponding 10–15% and 15–20% ranges under JUSFTA. Finally, if fixed costs are important, one would expect higher PURs in the higher import value ranges. This is generally the case, as confirmed in the regression results in Table 4 for a larger sample of preference receivers for both the EU and US preferential schemes.

Two other patterns are apparent from the comparisons. First, PURs are high for JUSFTA for large shipment sizes. In the $1 million and above ranges, with one exception, the PUR is 100% under JUSFTA, while this is not so for EUJFTA. Second, PURs are high in the low preferential margin 0%–5.5% ranges for both FTAs, which suggests that, on the whole, administrative costs are not high. These PURs are a very rough measure of fixed costs since one would need individual transactions rather than an average from all transactions during a year as shown in Table 2. Since both the EU and US allow for self-certification, differences in fixed costs could reflect product-composition effects and differences in shipment size for which we have no data.Footnote 21

Table 2. Preference utilization rates (PURs) of MFN dutiable imports by country (2016)

Note: * For the USA, utilization rates include FTA+ GSP+ QIZ + Civil Aircraft + pharmaceuticals.

Table A1 shows PURs and adjusted preferential margins by section for 2016 for both EUJFTA and JUSFTA. The patterns confirm those in Table 1. Ten of 21 sections have PURs of 90% or above for JUSFTA, while, under EUJFTA, only five sections have PURs above 90%. Several factors could account for these patterns: small value flows for the EU relative to the US that might be insufficient to cover fixed costs.Footnote 22 Probably more important are the differences in origin requirements across US FTA partners.

Table 2 compares the aggregate PURs for EU and US FTAs with some Middle-East and North African countries and, in some cases, for non-reciprocal preferences under the GSP for the US. Recall that preferential access is usually the same across FTA partners so a comparison of utilization of preferences is a rough indication of the effects of RoO. For EU FTAs, if one omits the Occupied Palestinian Territory PURs are high except for Jordan (and to a lesser extent Lebanon). Since RoO requirements are the same for all EU partners (these operate under PANEURO requirements), these differences could reflect composition effects and/or fixed costs playing out differently across shipment sizes.

By contrast, in the case of the US, RoO vary across partners and, as discussed earlier, RoO requirements for Jordan for T&A are the most lenient. Among the US FTAs, PURs are highest for Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt, all of which have the single transformation rule for T&A.Footnote 23 It is noticeable that Morocco has a PUR low in the US in spite of the same preferential margin as Jordan. Although it does not have an FTA with the US, Tunisia has GSP with higher PURs than Morocco. This difference in PURs is most likely due to Morocco facing much stricter RoO requirements for T&A.Footnote 24

More detail is provided at the HS2 (97 chapters) level in Tables A2 for JUSFTA and A3 for EUJFTA. The tables show adjusted and unadjusted margins, export volumes, and the number of HS8 observations for each chapter. Both tables show heterogeneity in PURs. Table A2 for JUSFTA confirms the 100% PUR for apparel (HS61 and 62), which have the highest adjusted margins of 14% and 11%. These two sectors also account for the bulk of imports under JUSFTA. But not all chapters with sizeable adjusted preference margins have high PURs. Of nine sectors with adjusted preferential margins of 5% and above, tools and cutlery (HS82) has a zero PUR, headgear (HS65) has a PUR of 29% and glass and glassware (HS70) has a PUR of 67%. Both sectors account for a negligible share of US imports from Jordan. Otherwise, sectors with large import volumes, such as for pearls and precious stones (HS71), have high PURs, even though preferential margins are not in the high range. In sum, Table A2 does not give the impression of high compliance costs associated with preferences in the case of JUSFTA.

For EUJFTA, inspections of PURs and preference margins show less regularity. Some exceptions to the expected positive PUR adjusted margin relation appear for the EU in Table A3. The most glaring one is for apparel (HS61 and HS62), where the adjusted preferential margins are around 6% – about half the corresponding rates under JUSFTA – but the PURs are very low at 1% (HS61) and 7% (HS62), even though imports from both sectors are not negligible (31 and 3 million €). These low PURs stand in contrast with the PUR of 67% for HS63 (other made-up textile products for 4.4 million €). In general, however, HS categories with adjusted preferential margins in the 10%–25% have PURs in the 90% above range so the low PURs for apparel appear as an exception. For example, edible vegetables (HS7) has a PUR of 100% for an adjusted margin of 3.3%. High PURs are also observed for animal fats and oils (HS15), sugars (HS17), tobacco (HS24) which have adjusted preferential margins in the 10% or above range.

In sum, except for HS61 and HS62, the patterns of PURs in Table A3 do not suggest high compliance costs under EUJFTA. However, a comparison of the top ten recipients of (adjusted) preferential margins at the HS4 level for both countries in Table A4 shows that for EUJFTA, with the exception of tobacco (HS2403), the top ten preference-adjusted margins do not always have high PURs and all represent negligible value flows (less than 100,000€). The opposite is the case for JUSFTA. Among the top ten, all have PURs of 100% and most are important flows in value terms.

Competition from other suppliers might also be a reason why Jordan does not supply garments to the EU market. Table 3 shows the top ten sources of apparel imports in 2016 for the EU and the US. Two patterns stand out. First, patterns are strikingly similar for both the US and the EU: (i) same order of magnitude among the top suppliers: (ii) a similar ranking among the top suppliers (China, Bangladesh, Vietnam): (iii) some importance for regional suppliers (Morocco and Tunisia for the EU and Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador for the US). Second, for the US, the top exporters have negative adjusted preferential margins (this is because as MFN suppliers they obtain less favourable terms than NAFTA and CAFTA_DR suppliers). Thus, compared with other suppliers in the US market, Jordan is getting as good, or better, access than competitors. On the other hand, on the EU side, Jordan is only getting better access than China, India, and Vietnam. So, in effect, Jordan is competing with garments from LDCs that also enter under the single transformation rule in the EU market.

Table 3. Top ten sources of imports of apparel (HS61 & HS62) in 2016

Notes: India and Vietnam are in the process of negotiating an FTA Bangladesh has been suspended from GSP in 2013 based on failure to meet labour safety with the EU standards.

NA stands for not-applicable, as no preferential RoO are required for MFN treatment.

*Indicates a Least Developed Country (LDC).

Table 4. Correlates of utilization of preferences on EU and US markets (2016) (Dependent variable: preference utilization rate)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Significance level: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

4. Evidence on the effects of RoO requirements from other FTAs

The comparison of PURs under EUJFTA and JUSFTA suggests that differences might at least partly, be due to differences in RoO requirements between the two FTAs, especially in the T&A sector. This section checks if this impression holds when controlling for other factors influencing preference utilization in a larger sample of countries exporting to the EU and the US. We estimate a regression of PURs on preference margins and import volumes for all countries exporting under preferential schemes to the EU and US. The objective is to check if one can detect a Jordan and/or apparel effect. As in Keck and Lendle (Reference Keck and Lendle2012), the following model is estimated separately for the EU and the US with 2016 data:

$$\eqalign{u_{k,x} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1 m_{k,x} + \beta _2 \log \left( {eligm_{k,x}} \right)+\beta _3\,{jor_{k,x}} \cr & \quad + \beta _4 (t \& a)_{k,x} + \beta _5 \left({jor_{k,x}}\right)(t\& a)_{k,x} \; + \; \beta _6 Agr_{k,x} + \gamma _x + \varepsilon _{k,x}}$$

$$\eqalign{u_{k,x} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1 m_{k,x} + \beta _2 \log \left( {eligm_{k,x}} \right)+\beta _3\,{jor_{k,x}} \cr & \quad + \beta _4 (t \& a)_{k,x} + \beta _5 \left({jor_{k,x}}\right)(t\& a)_{k,x} \; + \; \beta _6 Agr_{k,x} + \gamma _x + \varepsilon _{k,x}}$$ In (1), u k,x is, the PUR, i.e. the use of preferential access on imports of product k (at the HS8 level) by country x ; m k,x is the unadjusted preferential margin defined as the difference between the MFN tariff and the lowest preferential rate available for countryx; eligm k,x is the value of eligible imports of product k from country x; jor k,xis a dummy variable equal to 1 if exporter x is Jordan and 0 otherwise; ![]() $\left( {t\& a} \right)_{k,x} $ is a dummy equal to 1 if product k is in the apparel sector; γ x. is a country dummy. Equation (1) is estimated separately for the US and the EU because there is no concordance for products defined at the HS8-level.Footnote 25 Country dummies are included to control for heterogeneity.

$\left( {t\& a} \right)_{k,x} $ is a dummy equal to 1 if product k is in the apparel sector; γ x. is a country dummy. Equation (1) is estimated separately for the US and the EU because there is no concordance for products defined at the HS8-level.Footnote 25 Country dummies are included to control for heterogeneity.

The estimations are restricted to the products eligible for preferential treatment, i.e. products with 0 MFN tariffs and products excluded from the preferential regimes are not considered. The PUR is the ratio of imports entering under preferential treatment to total imports of the product eligible for preferences (i.e. to imports with a positive MFN tariff). We expect u k,x to be positively correlated with both a higher preferential margin (β 1 > 0) and with a higher import volume (β 2 > 0) because of fixed costs. If costs associated with RoO are purely variable costs, the utilization should only vary with the preferential margin. It should be independent of the volume when controlling for the margin. A coefficient (β 3 > 0, β 3 < 0) would capture a positive (negative) Jordan effect and, when interacted with apparel (β 5 > 0 or β 5 < 0), the coefficient would capture the effect of differences in RoO. The dummy variable for agriculture captures the possibility that meeting origin requirements should be easier as the ‘wholly obtained’ origin requirement is likely straightforward to implement (β 6 > 0)

When computed at the transaction level, the preferential utilization is either 0 (the product eligible for preferential treatment is imported under the MFN regime) or 1 (the eligible product is imported under the preferential trade regime). As we do not have access to transaction level data, preferential utilization rates range between 0 and 1 when computed at the HS8 level. As the dependent variable is the proportion of eligible imports that enter under preferential regimes, it is a continuous variable bounded by 0 and 1. Then the OLS linear regression is unsuitable. Hence, we use the fractional logit model as suggested by Keck and Lendle (Reference Keck and Lendle2012) but also report OLS and Tobit estimates for comparison with other estimates.

4.1 Results

To save space, we only report one set of results since results across specifications are close. For each of the EU and US, we report an OLS, a TOBIT, and a fractional logit (GLM).Footnote 26 First, as expected, PURs are positively associated with the preferential margin (β 1 >0) . Second, as in Keck and Lendle (Reference Keck and Lendle2012), the dummy for agriculture is positive and significant for both specifications. Third, as in Keck and Lendle, controlling for the margin, a higher import volume is associated with a higher PUR, (β 2 >0) an indication of fixed costs. Fourth, as expected, the dummy for Jordan is positive for both the EU and the US, but of larger magnitude for the US. This difference in coefficient values suggests that Jordanian exports are more competitive in the US than in the EU. Finally, the interaction of the dummy for Jordan with the dummy for T&A is positive for the US and negative for the EU. In the EU market for T&A, LDCs have benefitted from the single transformation rule since 2011, while Jordan was still operating under a double transformation rule in 2016. On the other hand, in the US market for T&A, most competitors operate under the yarn-forward (triple transformation) rule while Jordan operates under the single transformation rule. Together, these results point towards the origin requirement in T&A having an independent effect on the utilization of preferences in T&A.

5. Conclusions

This paper reviewed trade under EUJFTA and JUSFTA two FTAs initiated under similar circumstance over comparable periods. The comparisons show higher growth of imports under JUSFTA than under EUJFTA and, as of 2016, a higher utilization of preferences under JUSFTA than under EUJFTA, especially in the apparel sector where import volumes from Jordan to the US are much higher than those to the EU. For other sectors, preference utilization rates (PURs) follow similar patterns rising with the preference margin and average volumes. For the apparel sector, under EUJFTA, the PUR is in the 1%–7% range for a preferential margin of 11%–12% while under JUSFTA, the PUR is at 100% for a margin in the 14%−16% range. Three factors combine to induce this stark contrast. A higher preferential margin for the US, more competition from other (mostly LDCS) suppliers in the EU market that benefit from a single transformation rule for T&A, and a single transformation rule for T&A under JUSFTA.

This very different performance under the two FTAs amply justifies the relaxation decision (decision No.1/2016) announced in July 2016 by which market access of Jordanian exports to the EU will be improved by moving to a single transformation rule. However, since LDCs also access the EU market under a single transformation rule, in the end this announcement may only have limited effects on Jordanian exports to the EU. In addition, the EU decision also limits the beneficiaries who must be located in designated special economic zones, which could be equivalent to a quota on exports under a capacity constraint eligible for preferential market access. Indeed, companies operating outside the designated areas will have to incur costs to move operations if they want to benefit from preferences. In addition, the conflict in neighboring Syria has disrupted land transport through the country towards Syrian and Lebanese ports, leaving the port of Aqaba in the south of Jordan as the only viable option for Jordanian merchandises. Yet, inland transport to the Aqaba port from many of the designated special economic zones is very costly.

Beyond the refugee crisis, other simplifications in origin requirements would also be welcome to restore market access under preferential schemes, such as eliminating RoO requirements for tariff lines with unadjusted preferential margins below 3% – which corresponds to the middle range of estimates of fixed costs – at least for small firms (see Cadot and Melo, Reference Cadot and de Melo2007; Keck and Lendle, Reference Keck and Lendle2012). A uniform low value content rule (say 20% value-added across the board) perhaps combined with a Change of Tariff Classification (CTC) at the subheading (HS6) level could also be envisaged. Alternatively, the CTC might be at the heading level, while for T&A, it could be accompanied by a lower value-content rule for apparel, which has shown to be responsive to preferences under the Jordan–US FTA.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745618000174