1. Introduction

World Trade Organization (WTO) law offers three forms of remedies to protect a domestic industry against the injurious effects of imports: safeguard measures,Footnote 1 antidumping measures,Footnote 2 and countervailing dutiesFootnote 3 (collectively, ‘trade remedies’). Safeguard measures temporarily restrict imports of a product so as to protect a specific domestic industry from an increase in imports of any product that is causing, or threatening to cause, serious injury to the industry.Footnote 4 Antidumping measures, on the other hand, are introduced as a means of counteracting the injurious effects of products that are sold to another Member at ‘less than the normal value of the product’.Footnote 5 Finally, countervailing duties are introduced so as to protect a domestic industry from exporters or producers whose products benefit from a government subsidy that causes or threatens to cause injury to the industry in the importing country.Footnote 6

Due to the distorting effects of trade remedies,Footnote 7 their use is subject to the satisfaction of stringent criteria. In particular, these criteria include: (1) a requirement to determine that it is imports that have caused injury to the domestic industry (the causal link requirement); and (2) a requirement to determine that the injury to a Member's domestic industry was not caused by some factor or factors other than imports (the non-attribution requirement). This article will use the term ‘other known factors’Footnote 8 to mean all of those factors that could potentially cause injury to a Member's domestic industry other than imports. A domestic competent authority performs both the causal link and non-attribution analyses. It is only if the analysis that is performed by the domestic competent authority of a Member is challenged by another Member that a WTO Panel and the AB would be required to review the analysis of the domestic competent authority.

Despite the obvious benefits of having clear guidance about how the causal link and non-attribution limbs are to be interpreted, both the jurisprudence and academic commentary evidence a degree of confusion about how the rules are to be interpreted. This confusion has two fundamental sources. First, many commentators query the economic assumptions that are embedded in the drafting of Article 4.2 of the Safeguards Agreement, Article 3.5 of the Antidumping Agreement, and Article 15.5 of the SCM Agreement (collectively, ‘the provisions’). In particular, the provisions are drafted so as to reflect the premise that imports are capable, in some circumstances, of injuring a domestic industry. Several commentators, however, have contended that imports are a function of consumer tastes and habits, and therefore, that it is more accurate to say that it is a change in consumer tastes and habits via imports that can cause injury in some circumstances.Footnote 9 This economic debate is beyond the scope of this article. Moreover, any discussion of the jurisprudence relating to findings of temporal and other sources of correlation between imports and other injurious factors is also beyond the scope of this article, since this jurisprudence essentially relates to the same economic debate.Footnote 10

This article instead concerns itself with the second source of confusion raised by the provisions. This relates to the lack of a clear and consistent methodology for domestic competent authorities to use in order to: (1) separate the effects of imports from other known factors; and (2) determine whether the injurious effects of the imports are sufficient to reach the requisite injury threshold, as is required by the provisions. In adopting this focus, the article starts from the basic assumption that the economic premise embedded in the provisions of the trade remedies agreements is justified – namely, that imports are capable of causing harm to the domestic industry of a Member. In the alternative, this article argues that, even if the provisions are indeed ‘economically fallacious’,Footnote 11 a fact-finder is still required to follow the guidance in the jurisprudence as to how they are to be interpreted until such time as the provisions are either redrafted (which seems unlikely) or the jurisprudence signals a radically new interpretation.

As will be detailed in Section 4 below, the jurisprudence has consistently found that domestic injury need not be the product of imports alone. Instead, the AB has held that domestic injury may be the result of a combination of causal contributions from both imports and other known factors. Due to the AB's approach, a number of commentators have questioned the point of separating imports from other known factors.Footnote 12 Whilst this critique regarding the utility of the non-attribution limb is certainly compelling, this article argues that it is possible to reconcile the AB's approach with a meaningful non-attribution analysis. Such a reconciliation is possible if it is accepted that there is a level of causal contribution to a domestic industry from imports and a maximum level of causal contribution from other known factors. Indeed, it will be argued in Section 5 that the notion of using a minimum level of causal contribution from imports may also be inferred from both the statements made by the AB in US–Wheat Gluten and the three-step process involved in performing a causal link and non-attribution analyses set out therein. Section 4 will first consider the approach to performing the causal link and non-attribution analysis in the jurisprudence concerning each of the trade remedies. The conclusions drawn in Section 4 will then go on to inform the discussion in Section 5 regarding the role of the non-attribution analysis in determining causation in the application of trade remedies. Section 6 will then consider factors that are important in setting a threshold for the causal contribution of imports to serious injury. Finally, Section 7 draws upon the theoretical perspectives developed in the previous sections to propose a practical three-step model for performing the non-attribution and causal link analysis (‘Tripartite Non-Attribution/Causation Analysis’). First, however, the article examines the way in which the causal standard, ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ has been interpreted in the jurisprudence, and this is the subject of Section 2.

2. The Meaning of a ‘Genuine and Substantial Relationship of Cause and Effect’

In US–Wheat Gluten, the AB said that the causal standard for determining whether imports caused serious injury in the safeguards context was ‘a genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’.Footnote 13 The AB applied the same causal standard in the context of countervailing measures.Footnote 14 The AB has not yet had an opportunity to examine the anti-dumping causation standard in detail, but it did criticize a panel for failing to ‘examine whether the [United States International Trade Commission (USITC)] identified and explained the positive evidence establishing a genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect between imports and threat of injury’.Footnote 15 The causal standard of a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ has also been applied in the context of serious prejudice under the SCM Agreement.Footnote 16

Having found that the ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ standard applies to the provisions, it remains to consider: (1) the meaning of this standard, and (2) whether this causal standard has any implications for the determination of the causal link in the application of trade remedies. In examining the meaning of the term, ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’, this article will look at how the term has been interpreted in the serious prejudice jurisprudence, where the term is discussed in significantly greater depth than the trade remedies context. In so doing, it is important to note, as the AB did in US–Cotton,Footnote 17 that the causal link and non-attribution requirements in the trade remedies context ‘apply in different contexts and with different purposes’ than the causal link and non-attribution requirements in the serious prejudice context, and ‘[t]herefore, they must not be automatically transposed’.Footnote 18 Nonetheless, the jurisprudence that relates to the serious prejudice context can still be useful in helping to understand the meaning of that causal standard in the context of trade remedies.

In the context of serious prejudice, the AB in United States – Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft (Second Complaint) considered that the term, ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ means that:

When tasked with determining whether the causal link in question meets the requisite standard of a ‘genuine and substantial’ causal relationship, a panel will often be confronted with multiple factors that may have contributed, to varying degrees, to that effect. Indeed, in some circumstances, it may transpire that factors other than the subsidy at issue have caused a particular market effect. Yet the mere presence of other causes that contribute to a particular market effect does not, in itself, preclude the subsidy from being found to be a ‘genuine and substantial’ cause of that effect. Thus, as part of its assessment of the causal nexus between the subsidy at issue and the effect(s) that it is alleged to have had, a panel must seek to understand the interactions between the subsidy at issue and the various other causal factors, and make an assessment of their connections to, as well as the relative importance of the subsidy and of the other factors in bringing about, the relevant effects. In order to find that the subsidy is a genuine and substantial cause, a panel need not determine it to be the sole cause of that effect, or even that it is the only substantial cause of that effect. A panel must, however, take care to ensure that it does not attribute the effects of those other causal factors to the subsidies at issue, and that the other causal factors do not dilute the causal link between those subsidies and the alleged adverse effects such that it is not possible to characterize that link as a genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect. The subsidy at issue may be found to exhibit the requisite causal link notwithstanding the existence of other causes that contribute to producing the relevant market phenomena if, having given proper consideration to all other relevant contributing factors and their effects, the panel is satisfied that the contribution of the subsidy has been demonstrated to rise to that of a genuine and substantial cause.Footnote 19

The AB further considered the meaning of the term, a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ in US–Tyres (China) Footnote 20 when interpreting the meaning of ‘a significant cause’ in paragraph 16.4 of the Protocol on the Accession of the People's Republic of China to the World Trade Organization. Footnote 21 In that case, the AB found that the term ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ ‘implies a higher degree of causality than subject imports being merely “a cause” of the requisite level of injury to the domestic industry’.Footnote 22

With this survey of the meaning of ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ in view, it is clear that the causal standard relates to something less than 100% import-induced injury. That is, the causal standard has some tolerance for other known factors. Before seeking to interrogate the nature of the causal standard, it is important first to consider the meaning of ‘injury’ in the context of trade remedies.

3. The Meaning of ‘Injury’ in the Trade Remedies Context

It has just been seen that the legality of implementing a trade remedy depends on whether a Member can demonstrate that there is a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ between imports and injury to an industry. This section is concerned with understanding what is meant by ‘injury’ in the trade remedies context.

In the safeguards context, ‘serious injury’ to an industry is defined in the Safeguards Agreement as ‘a significant overall impairment in the position of a domestic industry’.Footnote 23 Turning to the Anti-Dumping context, ‘injury’ is defined as ‘material injury to a domestic industry, threat of material injury to a domestic industry or material retardation of the establishment of such an industry’.Footnote 24 The agreement does not define the term ‘material’. It does, however, require that a determination of injury be based on positive evidence and involve an objective examination of: (i) the volume of dumped imports and the effect of the dumped imports on prices in the domestic market for like products; and (ii) the consequent impact of the dumped imports on domestic producers of the like product.Footnote 25 Finally, in relation to countervailing duties, ‘injury’ is defined in the SCM Agreement in the same way as ‘injury’ is defined in the Anti-Dumping Agreement – namely, ‘material injury to a domestic industry, threat of material injury to a domestic industry or material retardation of the establishment of such an industry’.Footnote 26

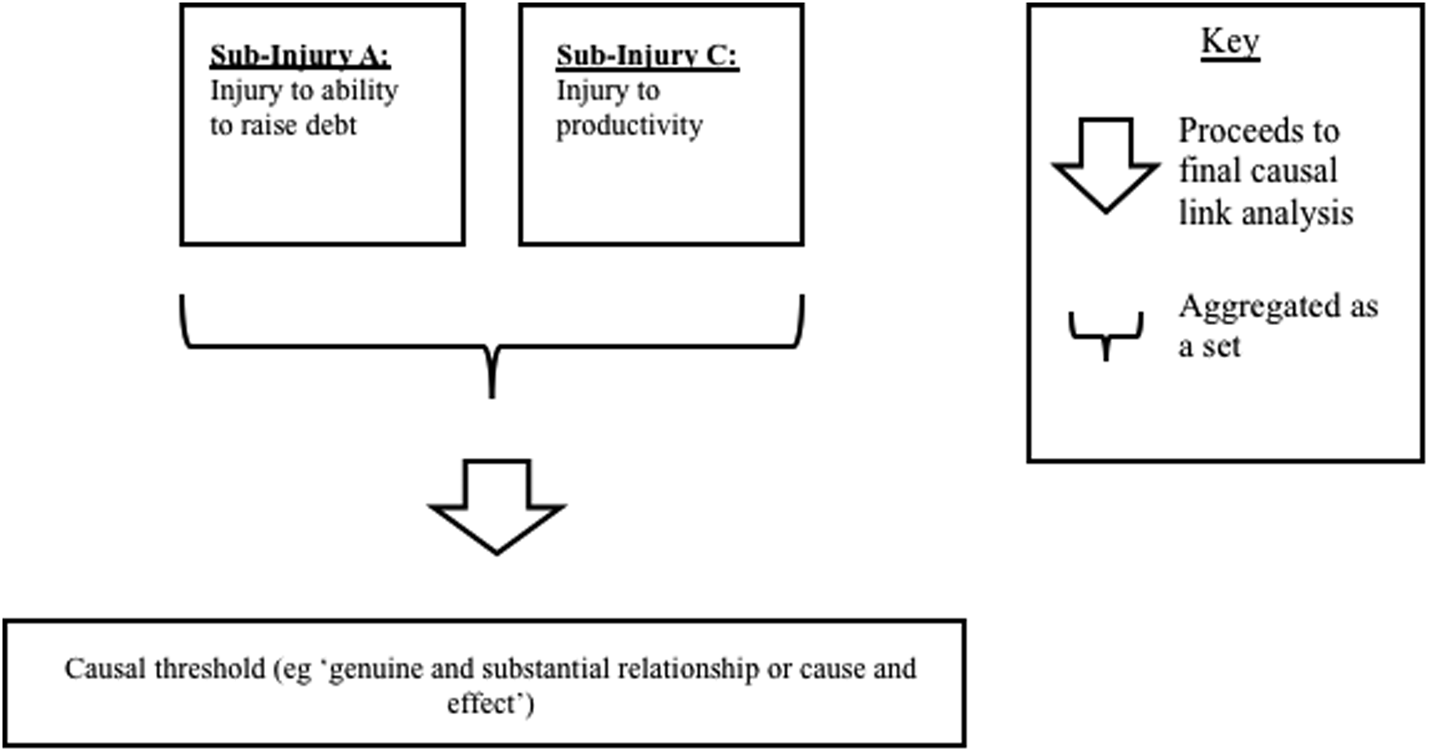

It is worth emphasizing that these definitions conceive of ‘injury’ as a general harm to an industry. This general or ‘overall’ harm to an industry is manifested in many ways – for example, injury to an industry manifests in an inability to raise debt, an injury to consumer demand, an injury to productivity etc. This article will call these manifestations or indicia of an overall harm ‘sub-injuries’, as they are smaller, more specific injuries that are a subset of the overall harm to an industry. Sub-injuries are additive, in the sense that they may be added together to total the ‘overall’ harm. This idea may be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of how an ‘overall’ injury to industry might be divided into sub-injuries

It is conceded that it is somewhat artificial to balkanize the indicia of injury to an industry in the clinical fashion suggested by ‘sub-injuries’. That is, in reality there is a significant degree of overlap between sub-injuries. For example, injury to an industry's productivity will obviously impact an industry's cash flow and this, in turn, will self-evidently affect an industry's ability to raise debt, etc. Nonetheless, it is suggested that the exercise of sub-dividing the overall injury into smaller sub-injuries is necessary for the process of performing the econometric analysis at Step 2 of the Tripartite Non-Attribution/Causation Analysis to be discussed in Section 6 below. To this end, it is suggested that data be collected about the nature of the ‘sub-injuries’ as they are at a particular moment in time.

The advantage of breaking down the analysis of injury to an industry into ‘sub-injuries’ – instead of examining the ‘overall’ injury in one step – is that an analysis that is broken down into its component parts is more likely to be fine-grained in nature, thereby increasing its accuracy and robustness. Conversely, analysing the ‘overall’ injury in one step is likely to be deficient in detail and of questionable accuracy. The notion of injury and ‘sub-injuries’ will be returned to in Sections 6 and 7 below. Before this, it remains to consider the factors involved in drawing the causal link between imports and injury.

4. The ‘Multi-factorial’ Approach

The first time that a Panel was requiredFootnote 27 to consider whether a domestic competent authority had satisfactorily demonstrated the causal link between increased imports and ‘serious injury or threat thereof’ was in US–Wheat Gluten,Footnote 28 in the context of safeguards. In that case, the US–Wheat Gluten Panel held that a WTO Member must ‘demonstrate that the increased imports … in and of themselves, cause serious injury.’Footnote 29 The US–Wheat Gluten Panel then went on to say that this does not mean that other known factors could not exist in a situation of serious injury, but simply that increased imports must be sufficient in and of themselves to reach the threshold of ‘serious injury’.Footnote 30

This idea that increased imports would be the sole reason to introduce safeguards will be referred to, throughout this article, as the ‘sufficiency of imports approach’. To illustrate the ‘sufficiency of imports approach’, it is helpful to think of the injury threshold as a kind of horizontal line along a y-axis. Depending on the nature of the imports, the imports will either reach this horizontal line or not. This may be seen in Figure 2, which demonstrates a situation in which the injury from imports does not reach the level of ‘serious injury’. Please note that the notion of ‘sub-injuries’ has been dispensed with in order to simplify the below diagram.

Figure 2. Graphic illustration of the ‘sufficiency of imports approach’

The US–Wheat Gluten Panel reflects the sufficiency of imports approach. That is, the Panel acknowledges that other known factors may have contributed to the injury in question, but it contends that imports must be sufficient in and of themselves to reach the threshold of ‘serious injury or threat thereof’. The US–Lamb Panel substantially repeated the sufficiency of imports approach in its report.Footnote 31

The AB in US–Wheat Gluten disagreed with the sufficiency of imports approach, leading it to overturn both the non-attribution and causal link analyses of the US–Wheat Gluten and US–Lamb panel reports. Specifically, the AB in US–Wheat Gluten said that: ‘the language of Article 4.2(b), as a whole, suggests that “the causal link” between increased imports and serious injury may exist, even though other factors are also contributing “at the same time”, to the situation of the domestic industry.’Footnote 32 It is convenient to call this approach by the short-form, ‘multi-factorial approach’. An illustration of the multi-factorial approach may be seen graphically in Figure 3 (again, the idea of ‘sub-injuries’ has been dispensed with in order to simplify the diagram).

A comparison of Figures 2 and 3 confirms that it is easier to reach the ‘serious injury’ threshold when the multi-factorial approach is used than when the sufficiency of imports approach is used. This is because, under the multi-factorial approach, both imports and other known factors might be combined together to reach the ‘serious injury’ threshold. The sufficiency of imports approach, however, would require that the ‘serious injury’ threshold is reached using imports alone. It follows from this that a causal link is more easily drawn when using the multi-factorial approach. The multi-factorial approach was subsequently upheld in later safeguards jurisprudence.Footnote 33

Figure 3. Graphic illustration of the ‘multi-factorial approach’

The applicability of the multi-factorial approach was confirmed by the panel in US–Hot Rolled Steel Footnote 34 and the need to perform a non-attribution analysis was also affirmed by the AB in the same case.Footnote 35 The multi-factorial approach and non-attribution requirement have been applied in subsequent Anti-Dumping jurisprudence.Footnote 36 Once again, the AB also confirmed the use of the ‘multi-factorial approach’ to the Article 15.5 context in EU–PET (Pakistan).Footnote 37 In short, the jurisprudence in relation to the use of all three of the trade remedies would seem to require the use of the multi-factorial approach and a non-attribution analysis that separates and distinguishes the causal contributions of imports vis-à-vis other known factors.

The multi-factorial approach and the non-attribution analysis developed in the above jurisprudence are consistent with the way in which the AB defined the term, ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ in US–Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint). That is, it will be recalled from the passage quoted in the previous section that the AB said in that case that ‘[t]he subsidy at issue may be found to exhibit the requisite causal link notwithstanding the existence of other causes’, but that a panel must ‘ensure that it does not attribute the effects of those other causal factors to the subsidies at issue’.Footnote 38 Notwithstanding the fact that the US–Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint) was concerned with subsidies instead of imports, the multi-factorial approach and the non-attribution analysis square precisely with the definition of a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’.

The choice of whether to use the sufficiency of imports approach or the multi-factorial approach has profound policy implications. First, a direct consequence of the multi-factorial approach is that, if the injury threshold is easier to reach using the multi-factorial approach, this means, in turn, that trade measures (and their attendant trade-distortive effects) will be easier to justify than when the sufficiency of imports approach is used. A second consequence of the use of the multi-factorial approach is that domestic competent authorities must find some way of separating and distinguishing the harms caused by increased imports from those caused by other known factors.Footnote 39 The purpose of this process is to assist with carrying out the non-attribution analysis – namely, ensuring that harm caused by other known factors is not falsely attributed to the harm produced by imports.Footnote 40 It is therefore important to consider the role of the non-attribution analysis in determining a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’, which is the subject of the next section.

5. The Role of the Non-Attribution Analysis in the Face of the Multi-Factorial Approach

Having seen that the AB has consistently found in favour of the multi-factorial approach, this article now turns to consider the apparent incompatibility between the multi-factorial approach and a non-attribution analysis. That is, on the one hand, it has just been seen that the multi-factorial approach requires that the causal contribution of imports be combined with the causal contribution of other known factors; and, on the other hand, a non-attribution analysis is aimed at separating imports from other known factors. A number of scholars have commented on this ostensible contradiction.

Irwin, for example, writing in the safeguards context, has said that ‘[n]on-attribution requires the authorities to separate and distinguish the sources of injury but otherwise plays no substantive role in the proceedings and cannot affect the end result.’Footnote 41 Similarly, Sapir and Trachtman have said that:

The AB's position on non-attribution in the safeguards setting has always been incoherent: the AB believes that separation is required, but cannot articulate a purpose for separation given that (in its view) there is no need to determine that the increased imports (in that context) are sufficient on their own to cause serious injury.Footnote 42

Also writing in the safeguards context, Sykes has said that ‘[i]f increased imports need not suffice to cause serious injury … but must simply have made some contribution to injury, what is the point of the non-attribution requirement?’Footnote 43 Finally, writing in the antidumping context, Mavroidis et al. also contend on what seems to have been the same assumption that:

While there is an obligation to separate and distinguish the nature and extent of the injury caused by other factors, it appears that the [AB] holds the view that there is no need to somehow quantify and deduct the injury caused by other factors from the injury caused by the dumped imports to determine whether the dumped imports alone were sufficient to cause material injury. What the goal of separating and distinguishing these other factors’ effects then is, remains an open question.Footnote 44

Despite this ongoing concern in the literature, it is suggested that a non-attribution analysis is only at odds with the multi-factorial approach if injury to the industry must be caused by 100% imports. One way of resolving this inconsistency is to infer that the threshold of import-induced sub-injury is actually less than 100%. That is, it might be inferred that there is some tolerance for those sub-injuries to industry that were the product of a combination of imports and other known factors. Indeed, the idea that a threshold that is lower than 100% import-induced may also be inferred from the AB's insistence on a multi-factorial approach. It is worth repeating that the AB has said that ‘the language in the first sentence of Article 4.2(b) does not suggest that increased imports be the sole cause of the serious injury, or that “other factors” causing injury must be excluded from the determination of serious injury’.Footnote 45 Moreover, it is worth recalling that the AB in US–Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint) said that ‘a panel need not determine [a subsidy] to be the sole cause of that effect, or even that it is the only substantial cause of that effect’Footnote 46 in order to find a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’.

It surely follows from the AB's statements that the test for non-attribution must be something less than 100% import-induced, though the AB has not explicitly stated what this threshold is. This tolerance for some level of causal contribution by other known factors reflects a more realistic view of harm to industry. That is, it is unrealistic that harm to industry would purely and solely be caused by imports alone. Instead, it is logical that those sub-injuries inflicted on an industry would be the result of a combination of injurious effects inflicted by both imports and other known factors.

Indeed, the idea that injury to an industry need not be 100% the product of imports can also be seen in US domestic law. For example, in the US safeguards context, the Senate Finance Committee has held that the USITC need only ‘assure themselves’ that imports are a substantial cause.Footnote 47 This is a different standard to Article 4.2 of the Safeguards Agreement; but nonetheless, it indicates that, in US domestic law, imports need not be the sole cause of injury to domestic industry. Moreover, in the context of countervailing duties, the United States’ countervailing duty legislation provides that countervailing duties may be imposed where an industry is materially injured ‘by reason of imports’.Footnote 48 The USITC does not need to determine whether subsidized imports are the principal cause of material injury – rather, only that the subsidized imports contributed to the injury.Footnote 49 In sum, under US domestic law, injury from imports must reach, on its own, a minimum threshold – namely, ‘substantial cause’ in the safeguards context and ‘by reason of’ in the countervailing duties context. There is no requirement, however, that injury to industry be the product of imports alone in the context of safeguards and countervailing duties.

Similarly, in EU domestic law, there is also some allowance for the causative role of other known factors in bringing about injury to industry in the antidumping context. First, the investigation into causality at the EU level involves both a positive test and a negative test. The positive test, namely, Article 3(6) of Regulation 1225/2009,Footnote 50 does not specifically require injury to be caused ‘through the effects of dumping’. Accordingly, it is sufficient to make an injury determination when the volume and/or price levels of the dumped imports indicate that dumping was a significant cause of injury, even though there may be more significant causes than the dumping.Footnote 51 In sum, as with the US domestic law context, injury in the EU anti-dumping context requires that injury from dumping must, on its own, reach a certain threshold – namely ‘significant’ cause. The negative causality test is set out in Article 3(7) of the same regulation. It provides that: ‘known factors other than the dumped imports which at the same time are injuring the Community industry shall also be examined to ensure that injury caused by these other factors is not attributed to the dumped imports under paragraph 6’. In other words, the EU domestic law provides for some form of non-attribution analysis, and then allows a causal link to be drawn between imports and injury, even where other known factors have also played some causative role. This survey of US and EU domestic law has shown that there are contexts in which injury to industry need not be 100% the product of imports.

Moreover, the EU Commission's approach to determining causation in relation to the application of trade remedies further suggests that the threshold may be something less than 100%. The EU Commission has extensively used the ‘breaking the causal link’ approach to determine causation, which also relies on the notion of having a minimum level of injury by subject imports and a maximum level of injury by other known factors. This approach involves, as a first step, making a provisional assessment as to whether there is a causal link between imports and the domestic injury. Then, as a second step, the fact-finder must turn to consider whether any other known factors could have broken this causal link.

Implicit in the ‘breaking the causal link’ approach is that the point at which the causal link is broken is the point at which the percentage of other known factors exceeds its maximum, and, concomitantly, that imports fell short of reaching their threshold. For example, in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1013 of 17 July 2018,Footnote 52 the Commission made a preliminary determination that there was a causal link between the increase of steel imports and a threat of serious injury to the EU.Footnote 53 It then went on to examine other known factors that might have broken the causal link – including, global overcapacityFootnote 54 and imports from the European Economic Area.Footnote 55 The Commission determined, however, that these other known factors were insufficient to have broken the causal link between steel imports and injury to the EU, and, accordingly, provisional safeguard measures were implemented.Footnote 56 To put this another way, the other known factors did not exceed the maximum level of injury to ‘break’ the causal link between the subject imports and injury to industry.

In contrast, in Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 1194/2013 of 19 November 2013, the Commission made a preliminary determination that there was a causal link between the dumped imports of biodiesel from Argentina and the injury suffered by the Union industry.Footnote 57 This conclusion, however, was revisited by the Commission in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1570 of 18 October 2018.Footnote 58 In the latter case, the Commission found that, during the investigation period almost half of all imports into the Union came from Indonesia at a price lower than either Union or Argentinian prices.Footnote 59 Moreover, the exponential increase of import volumes from Indonesia as well as their market share significantly contributed to the material injury to the Union industry.Footnote 60 Finally, the Commission found that the Union industry was at overcapacity and that the Union had inflicted some injuries on itself.Footnote 61 Accordingly, the Commission concluded that it could not establish that there was ‘a genuine and substantial causal relationship between the dumped imports from Argentina and the material injury suffered by the Union industry’.Footnote 62

It is implicit in the reasoning of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1570 of 18 October 2018 Footnote 63 that the point at which the causal link between the dumping of Argentinian biodiesel and the injury to the Union industry occurred was the point at which the other known factors exceeded the maximum threshold (and, by implication, that the dumping of Argentinian biodiesel fell short of the threshold). In this sense, the ‘breaking the causal link’ approach appears to be premised on this same idea of having some kind of maximum threshold of other known factors and minimum threshold of imports. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a non-attribution and causal link analysis that would not adopt this approach. The EU Commission has not actually explicitly prescribed the threshold at which the other known factors is exceeded; but the above case suggests that one does, in fact, exist.

Bringing the discussion back to WTO law, if the threshold is something less than 100% and that causal contributions to ‘serious injury’ may be the product of both imports and other known factors, it follows that the non-attribution analysis must achieve two outcomes. That is, it must: (1) separate harm caused by imports from harm caused by other known factors; and (2) allocate to imports and other known factors a percentage that reflects their causal contribution to injury. Indeed, these two outcomes appear to be consistent with the three-step approach to the non-attribution and causal link analysis proposed by the AB in US–Wheat Gluten Footnote 64 in the safeguards context. In that case, the AB said that the non-attribution and causal link analysis should involve: (1) distinguishing the injurious effects of imports from the injurious effects caused by other factors; (2) attributing the level of injury caused by imports on the one hand vis-à-vis other known factors; and (3) as a final step, determining whether a causal link exists between imports and injury to industry, ‘and whether this causal link involves a genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect between those two elements’.Footnote 65 Therefore, the idea of non-attribution being a two-step process that is followed by a final causal link analysis is consistent with the three-step approach set out by the AB in US–Wheat Gluten.

The idea that the non-attribution analysis might include the allocation of percentage weightings to imports on the one hand and other known factors on the other is in keeping with the conception of non-attribution discussed by the Panel in EC–Countervailing Measures on DRAM Chips:Footnote 66

In our view, it does not suffice for an investigating authority merely to ‘check the box’. An investigating authority must do more than simply list other known factors, and then dismiss their role with bare qualitative assertions, such as ‘the factor did not contribute in any significant way to the injury’, or ‘the factor did not break the causal link between subsidized imports and material injury.’ In our view, an investigating authority must make a better effort to quantify the impact of other known factors, relative to subsidized imports, preferably using elementary economic constructs or models. At the very least, the non-attribution language of Article 15.5 requires from an investigating authority a satisfactory explanation of the nature and extent of the injurious effects of the other factors, as distinguished from the injurious effects of the subsidized imports.Footnote 67

Here, the panel suggests that it is not sufficient simply to separate imports from other known factors; but that inquiry ought also to be had into the level of causal contribution. To this end, the emphasis of ‘nature and extent of the injurious effects of the other factors’ is significant.

In order for a non-attribution analysis not only to disaggregate the injurious effects of imports vis-à-vis other known factors, but also to allocate percentage contributions to them, it is suggested that the non-attribution analysis should rely on the use of quantitative tests.Footnote 68 That is, a quantitative test would be more appropriate than a qualitative test in determining how responsibility for an injury to an industry should be apportioned. Indeed, the panel in EC–Countervailing Measures on DRAM Chips even suggests that the non-attribution analysis should draw upon ‘economic constructs or models’.Footnote 69 To this end, some econometric tests have already been developed, largely in the context of trade remedy investigations involving section 201 of the US 1974 Trade Act.Footnote 70 These existing econometric tests might be adapted to the WTO context; or alternatively, panels have the ability, under Article 13.2 of the DSU,Footnote 71 to consult econometricians regarding the design of appropriate quantitative tests. Having established in this section that a useful non-attribution analysis can be reconciled with the multi-factorial approach if the threshold for injury to industry is less than 100%, it now remains to discuss at what level the threshold ought to be set.

6. The Threshold

Section 4 above discussed the idea that the AB has consistently found that an injury to an industry may be the product of a combination of imports and other known factors – that is, the multi-factorial approach should be used. Section 4, in turn, then posited that this multi-factorial approach might be reconciled with a useful non-attribution analysis, if the threshold for including import-induced injury was something less than 100%. Section 4 also considered that the non-attribution analysis involved two separate steps: (1) separating imports from other known factors; and (2) apportioning causal responsibility for injury to imports vis-à-vis other known factors based on econometric tests. This section will discuss what an appropriate threshold might be for import-induced injuries. That is, whilst it is suggested that the threshold ought to be something less than 100%, it is unclear at what level it should be set.

It has been seen that the raison d’être for having a threshold is that only those sub-injuries to industry that received a minimum level of causal contribution from imports should be included in the final causal link analysis. So, for example, if the threshold of causal contribution from imports to sub-injury to industry is 70%, those sub-injuries to industry that were found, after a non-attribution analysis, to be less than 70% the product of imports (and thus, more than 30% other known factors) would be excluded from the causal link analysis at the final stage. If, on the other hand, the threshold for the non-attribution test is 50%, then those sub-injuries that were 50% the product of imports (or more) and 50% the product of other known factors (or less) would not be discarded.

Self-evidently, the lower the threshold, the more sub-injuries would go on to be included in the causal link analysis at the final stage. Moreover, the more sub-injuries that are included in the analysis, the greater the likelihood, in turn, that the threshold of ‘serious injury or threat thereof’ would be reached and the causal link between imports and injury would be made out. This idea may be seen graphically in Figure 4 below:

Figure 4. The impact of different tolerance thresholds on whether sub-injuries/sub-effects would pass the causal threshold

It follows from this observation that the ‘serious injury’ threshold must be set bearing in mind the level of trade distortion inflicted by each type of trade remedy. For example, antidumping measures tend to be less trade-restrictive than safeguard measures,Footnote 72 and therefore it is likely that the ‘serious injury’ threshold would be set lower than for safeguard measures. It is also possible that the AB would wish to retain some level of flexibility as to the point at which the threshold might be set, depending on the nature of the case at hand. Retaining such flexibility, however, would be at the cost of legal certainty. Either way, it would be helpful to have some indication from the AB as to how the threshold might be set in relation to each of the trade remedies.

From the perspective of a domestic competent authority trying to make out this causal link, then, the lower the threshold, the easier it is to demonstrate the causal link. The easier it is to make out the causal link, the easier it is, in turn, to justify the use of trade remedies. For this reason, the threshold must be set with great care. It must balance the practical reality that injuries to industry are generally inflicted by a combination of imports and other known factors vis-à-vis the ease of justifying the introduction of trade remedies. Having now surveyed the theoretical underpinnings of the causal link and non-attribution analysis, as well as the factors to be considered in setting the threshold, it remains to bring these elements together and put forward a proposed three-step model of what a causal link and non-attribution analysis might look like in practice.

7. The Three-Step Causal Link and Non-Attribution Analysis

In order to consider how the causal link and non-attribution analysis might look in practice, it is arguably helpful to draw on the guidance from the AB in US–Wheat Gluten set out in Section 5 above, which said that the causal link and non-attribution analysis outlined above could be conceived of in three steps.Footnote 73 Although the US–Wheat Gluten case was concerned with safeguards, it is suggested that the conceptual basis underlying the causal link and non-attribution analysis is the same for anti-dumping and countervailing measures (though the threshold may differ for each trade remedy, as was discussed in Section 6 above).

The first step consists of separating out the different sub-injuries inflicted on a domestic market. For example, the sub-injuries might include: injuries to the ability to raise debt, injury to productivity, injury to corporate profits, loss of sales, etc. The second step involves apportioning responsibility for each sub-injury between imports on the one hand vis-à-vis other known factors using econometric tests. Once this apportionment is completed, it remains to assess which sub-injuries are sufficiently the products of imports that they reach the prescribed threshold. For example, if the prescribed threshold is ⩾70%, only those sub-injuries that are ⩾70% the product of imports would go on to be considered in the final causation analysis in the third step – that is, a consideration of whether there is a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ between imports and the injury to the industry. These three steps may be summarized in Figure 5.

As can be seen from Figure 5, sub-injury B does not qualify for the final causal link analysis in Step 3 because it has been found that the level of causal input from imports to sub-injury B is less than the threshold amount of ⩾70%. As a result, only sub-injuries A and C qualify for the final causal link analysis in Step 3. In relation to Step 3 – that is, the question of whether there is a ‘genuine relationship of cause and effect’ between imports and injury – the jurisprudence has offered very little practical guidance. Nonetheless, it would seem logical that the domestic competent authority must aggregate all of the sub-injuries that have qualified for Step 3 and then decide whether they are sufficient in number and extent to constitute a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ between imports and injury. To put this in more technical language, the inquiry interrogates whether, once the injurious effects of the other known factors are separated, the sub-injuries are sufficient as a set to amount to a ‘genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect’ between imports and the overall injury to the industry. The analysis in step 3 might therefore be represented in Figure 6.

Figure 5. Graphic illustration of a proposed causal link and non-attribution analysis

Figure 6. Step 3 of the causal link and non-attribution analysis

The advantages of using the three-step causal link and non-attribution analysis proposed here are that: (1) it has the potential to be a more transparent and fairer method of demonstrating causation between imports and injury, especially if the AB were to set a pre-determined threshold; (2) it adheres to the requirements of the provisions and the guidance in the jurisprudence; and (3) it promotes a rigorous approach to determining causation based on quantitative methods.

8. Conclusion

Before one Member can implement trade remedies against another, it is critical that the Member satisfies itself that the harm to its domestic industry was the result of imports, as opposed to other known factors. The performance of a non-attribution and causal link analysis is central to this process. That is, non-attribution seeks to distinguish the causative impact of imports from other known factors, whilst the causal link analysis aims to draw a positive link between the imports and harm to industry. Nonetheless, it has been seen that several commentators have queried the utility of a robust non-attribution analysis in the face of the AB's insistence that injury to the domestic industry need not be the result of imports alone. In short, commentators question the point of separating imports from other known factors, if the two are then later combined.

This article has sought to resolve this apparent contradiction by proposing that there is an implied threshold of causative contributions from imports and a maximum causal contribution from other known factors. Such an approach relies on the use of econometric tests as a means of separating the causal contributions of imports from other known factors and allocating responsibility to each accordingly. The article then draws upon these theoretical elements to put forward a practical three-step model that may be performed as a means of achieving a non-attribution and causal link analysis based on the guidance given by the AB in US–Wheat Gluten.