1. Introduction

The fourth industrial revolution, characterized by technologies that blur the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres, marks the commencement of the era of the digital economy.Footnote 1 However, using technologies to connect the physical world with the digital world also creates significant new challenges for policymakers in the global economy. In foreign investment law, states are seeking to promote digital economic development while strengthening their ‘right to regulate’ the digital economy, especially data. One way in which states impose regulation is through data localization, whereby specific categories of data are required to be collected, processed, or stored inside a country, thus precluding cross-border data transfer. Given modern life relies heavily on digital trade in a number of sectors including telecommunications, computer services, and internet publishing services, the issue of how data localization influences digital trade has been receiving increasing attention.Footnote 2 However, scholars have paid less attention to the relationship between data localization and investment. With increasing cross-border digital investment, data are likely to be recognized as property, a typical category of ‘asset’, and thus an investment for international investment law.Footnote 3 Based on the assumption that data localization measures may cause additional costs for foreign corporations, some states and scholars have argued that data localization measures violate principles of national treatment,Footnote 4 which prohibits negative differentiation between foreign and national investors.Footnote 5 This article will examine whether data localization violates national treatment in international investment treaties.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 starts by asking whether data localization measures may violate national treatment in international investment treaties. That is, do data qualify as ‘investment’ in international investment treaties? Section 3 applies the ‘three-step’ approach to assessing the legality of data localization in international investment treaties, asking: whether foreign investors and domestic investors are in ‘like circumstances’; whether foreign investors are treated less favorably by data localization measures; and whether there are either explicit or implicit exceptions in international investment treaties for states to justify the differential treatments. Based on jurisprudence from international investment arbitrations, this article proposes that whether or not data localization legislation violates national treatment in international investment treaties will depend on several factors, including the state's regulatory purpose, the state's classification of economic sectors, and the state's technological capability to prevent surveillance and attack. Section 4 considers data localization in domestic legislation and international treaties from a Chinese perspective. From a study of the decisions of cases before Chinese domestic courts and Chinese international investment treaties, this article finds that data should qualify as an ‘investment’ under Chinese international investment treaties. As China adopts the pre-establishment national treatment provision in its Foreign Investment Law and the China–EU Comprehensive Investment Agreement, China needs to carefully set out the legal bases for limiting the cross-border transfer of data to ensure that they are not violating its national treatment obligations in international investment treaties.

2 Data and Investment in International Investment Treaties

2.1 Data Localization in Domestic Legislation Regarding Investment

There are various data localization laws in different states, which fall into three categories. The first category is that data should be physically stored within a country's jurisdiction, regardless of whether the data could also be transferred abroad.Footnote 6 For example, the Federal Law No. 242-FZ of Russia requires that the processing of personal data of Russian citizens be conducted with the use of servers located in Russia.Footnote 7 The second category requires that the use of computing facilities remain within a state. Through a decree amending the Code of Electronic Communications, France made a ‘territorial’ restriction that requires that the interception systems of electronic communications be established in France.Footnote 8 The third category is localization of service. For example, Canada requires 80 percent of the members on the board of directors of facilities-based telecommunication services suppliers to be Canadian citizens.Footnote 9 Although there are other ways to cause additional burdens on free data transfer, such as a levy of ‘data tax’ to data derived from users’ activities in a state,Footnote 10 such measures are generally different to direct and explicit data localization. In this regard, this article focuses on the above three categories.

Among the three requirements, the requirement of where data are stored/processed applies to both national citizens and foreign investors. Meanwhile, infrastructure and service localization are likely to affect foreign investors more than domestic investors. Therefore, data localization, especially the requirement of local storage, is likely to raise concerns that national treatment, which is primarily concerned with preventing discrimination based on nationality,Footnote 11 has been violated. A preliminary question is whether data are ‘investment’ in international investment treaties.

2.2 The Definition of ‘Investment’ in International Investment Law

There is no uniform definition of ‘investment’. In international investment law, the definitions of ‘investment’ vary from domestic regimes to international regimes. And the definitions also differ among different countries. From a comparative study of these different definitions,Footnote 12 some patterns of development can be observed. Currently, most BITs adopt a rather broad and open-ended approach by defining ‘investment’ as including ‘every kind of asset’, and the definition clause is usually accompanied by an illustrative list of assets that fall within the definition,Footnote 13 while many multilateral investment agreements and free trade agreements define ‘investment’ with a closed list. In these BITs, the term ‘every kind’ provides an open-ended avenue to include a variety of assets. In fact, this broad approach is more often endorsed by developed countries than developing countries because developed countries are more likely to be capital-exporting countries in cross-border trade and investment. In these circumstances, the developed countries are inclined to enlarge the scope of protection for the exported capital.

The second observation of this comparative study is that there are generally six categories of assets that fall within the definition of ‘investment’, but just five of them are covered by most BITs. These five categories are movable and immovable property, companies and interests in companies, intellectual property rights, claims, and concessions, although the relevant language in each BIT varies slightly. Additional types of asset are licenses and permits, which are contained in only a few BITs.Footnote 14 The first five categories basically refer to the transfer of rights between private parties in accordance with laws of general application, while the sixth category concerns rights that the state grants to private parties through special legislation or administrative action.Footnote 15

Currently states generally intend to adopt a broad approach when interpreting investment so as to encourage free investment, but the breadth of recognized investment still varies among states. According to the above mainstream definitions of investment, current international investment treaties have not explicitly listed ‘data’ as a category of investment. Though many international investment treaties include intellectual property rights as a category of investment, ‘raw’ user data not creatively processed are not regarded as an intellectual property right.Footnote 16

Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention intentionally leaves investment undefined to preserve flexibility and to allow for ‘future progressive development of international law on the topic of investment’.Footnote 17 The approaches to interpreting investment in international investment arbitrations are not unanimous and consistent.Footnote 18 In the existing case law, a widely, yet not universally, accepted approach to define investment is the Salini test. It states an investment must have four essential elements: (i) a contribution of capital or other resources; (ii) a certain duration; (iii) the assumption of risk; and (iv) a contribution to the development of the host state.Footnote 19

As for the requirements of ‘a contribution of capital or other resources’, the Salini test can be financial, cultural, or environmental.Footnote 20 According to arbitral practice, the contribution of resources is not limited to financial capital, but also includes ‘know how, equipment and personnel’, and ‘financial terms’.Footnote 21 The contribution requirement calls for a consideration of the nature and the type of data. The economic and social value of data varies in different types of data. According to an approach taken by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) based on the distinction of the parties involved in data flows, data can be classified into four types: Business to Business (B2B), Business to Consumer (B2C), Government to Citizen (G2C), and Citizen to Citizen (C2C).Footnote 22 B2B data, such as financial resources, and B2C data, such as health and financial services, are likely to meet ‘a contribution of capital or other resources’ requirement. G2C data, such as citizens’ health and tax data, are produced by the government. C2C data, such as emails and messages, are produced by citizens. Both G2C and C2C do not, when conceptualized narrowly, involve a foreign corporation's expenditure of resources. However, it should be noted that the practical reality is much more complicated than the theoretical classification, namely there are numerous mixed-data circumstances. For example, when a foreign social media such as Facebook is operating in the host state, it carries C2C data produced by Facebook users. Facebook may claim that it carries B2C data processed based on the C2C data. In this way, Facebook has made a significant ‘contribution of capital and other resources’ in producing and operating its B2C data so that these data are protected as ‘investment’ in the International Investments Agreements (IIAs).

In building a database, data are consistently created, collected, and processed, which takes a certain duration and updates the database substantially, meeting the Salini test requirement of ‘a certain duration’. With respect to the requirement of ‘the assumption of risk’, given the importance of data, many states regulate free cross-border data transfer through domestic regulations. In this sense, data are at risk of being regulated. Regulation such as data localization is likely to increase costs to foreign investors.Footnote 23 Namely, foreign investors are at risk of suffering economic loss given the regulation.

Another key to applying the Salini test to data is to consider whether the requirement ‘a contribution to the development of the host state’ is met. Whether data can contribute to the development of the host state depends on specific facts. In a broad sense, data can bring economic and social benefits to the host state in many ways, including giving rise to new business opportunities and increasing competition and co-operation within and across sectors.Footnote 24 Data can also underpin the host state's many new business models that transform markets and sectors and drive productivity growth.Footnote 25 In many cases, foreign corporations’ data can contribute to the development of the host state by promoting its digital economy. Based on the above analysis, B2B and B2C data with economic value are likely to satisfy the definition of investment either in international investment treaties or by virtue of the Salini test. However, this does not mean that other categories of data do not definitely contribute to the development of the host state. The understanding of the nature of data is related to the element in the discussion. In the Facebook example above, Facebook users provide their data for free to Facebook, which monetizes the data. Considering that the contribution is not limited to financial capital but includes personnel, according to the Salini test if we take data as labor in the Industrial Revolution,Footnote 26 data provided to Facebook can also contribute to the development of the host state similarly to the contribution of labor, no matter whether the enterprises have paid for collecting these data or not. Assuming that data are regarded as an investment in an international investment treaty, the next question is whether data localization violates the national treatment principle in international investment treaties.

3 Data Localization and National Treatment in International Investment Treaties

3.1 Economic Impact of Data Localization on Investment

According to a 2018 OECD study, a 10% increase in bilateral digital connectivity raises goods trade by nearly 2 percent.Footnote 27 Cross-border data transfer is essential for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, creating a new breed of ‘micro multinationals’ which are ‘born global’.Footnote 28 Data transfer enables small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) to access information technology services and therefore to reduce their cost for upfront investment in digital infrastructure. With better access to critical knowledge and information, SMEs can overcome their information disadvantages and compete with larger enterprises.Footnote 29 Conversely, there are a number of studies that indicate that data localization gives rise to an increase in costs for corporations.Footnote 30 In the past, corporations choose data centers with cheap electricity, low taxes, and a large number of qualified IT specialists.Footnote 31 Data localization measures usually entail additional costs for enterprises, including investment in storage capacity, duplication of servers, and data management.Footnote 32 Specifically, data localization legislation is likely to have a greater impact SMEs than large transnational enterprises.Footnote 33

Considering the possible economic costs for foreign corporations, some scholars argue that data localization measures violate principles of international investment law, including national treatment, fair and equitable treatment, and non-expropriation.Footnote 34 However, some other scholars do not agree. They claim that states can maintain their ‘right to regulate’, to pursue public welfare, and other interests.Footnote 35 The intentions to balance interests of data regulation and other public welfare can also be found in recent digital trade agreements.Footnote 36 So far, there is extensive scholarship addressing whether data localization violates national treatment in international trade law and how WTO law can contribute to the regulation of cross-border data transfer.Footnote 37 So far, no dispute before the WTO has clarified the relationship between data localization and states’ national treatment obligation. Though there have been two WTO cases with respect to the applicability of the GATS to internet services,Footnote 38 neither of them specifically addressed data localization measures. Furthermore, given that national treatment in international investment treaties and in the WTO has certain historical links, notwithstanding some differences in language,Footnote 39 GATT/WTO jurisprudence has noticeably influenced investor–state arbitral jurisprudence. This influence has been manifest in many cases before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which has drawn upon WTO jurisprudence when interpreting national treatment in investment dispute settlement. WTO jurisprudence on national treatment, such as the Japan–Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages case,Footnote 40 plays a guiding role in the interpretation of ‘like circumstances’, one key element of national treatment in international investment treaties. This interpretative influence has guided the ICSID despite WTO law differing from international investment treaties in various respects, including the scope of application, legislative body, and justifiable exceptions. In this regard, even though data localization may violate national treatment in international trade law, the assessment of the legality of data localization in international investment treaties will be different. This article applies the ‘three-step’ approach to assess the legality of data localization in international investment treaties in the next sections.

3.2 An Assessment of the Legality of Data Localizations by Applying the ‘Three-Step’ Approach

An evaluation of the legality of data localization in international investment treaties requires consideration of cases before international arbitral tribunals. It is well-acknowledged that the concrete application of a national treatment clause is fact-specific.Footnote 41 In terms of the interpretation of ‘like circumstances’, each tribunal adopts its own rules of interpretation. The differing thresholds employed by different tribunals and the inconsistency of outcomes have contributed to the ‘legitimacy crisis’ in international investment treaty arbitration.Footnote 42 This inconsistency is exacerbated by the fact that the common principle of precedent is not applicable in international investment arbitration; prior decisions have no binding force. Unlike the WTO, which has an Appellate Body with a centralized interpretation authority,Footnote 43 there is no organ in the international investment regime that can give ultimate authoritative interpretations and reconcile conflicting decisions.Footnote 44 Therefore, it is challenging to draw universal principles from the cases concerning the interpretation of national treatment.

Many international arbitral tribunals refer to a ‘three-step’ process in applying the national treatment clause.Footnote 45 First, the foreign investor and domestic investor should be in ‘like’ circumstances. Second, the treatment accorded to the foreign investor should be at least as favorable as the treatment accorded to domestic investors.Footnote 46 Third, consideration is given to any legitimate, non-protectionist rationales to justify the differential treatment.Footnote 47 In this context, whether data-localization violates a national treatment obligation is never a simple question, but should be determined according to the circumstances of each case. This article conducts this analysis sequentially following the ‘three-step’ approach.

3.2.1 Like Circumstances

To apply national treatment in international investment treaties, it must first be established that the foreign investment and domestic investment are in like circumstances. Determining whether foreign investment and domestic investment are in like circumstances requires the investment tribunal to make ‘an evaluation of the entire fact setting’ and think of ‘all the relevant circumstances’.Footnote 48

3.2.1.1 Comparators

Occidental v. Ecuador and Methanex v. US demonstrates the two divergent approaches that tribunals are now adopting concerning comparable subjects with consideration of ‘the entire fact setting’. In the Occidental Exploration & Production Corporation v. Ecuador case, the tribunal compared all foreign investors with domestic investors. It implied that foreign investors in different economic sectors might be in like circumstances with domestic investors.Footnote 49 However, the NAFTA tribunal favored a contrary approach in Pope & Talbot v. Canada, where the tribunal only compared foreign investors that were in the most ‘like circumstances’ and not comparators that were in less ‘like circumstances’.Footnote 50 In most cases, such as the SD Myers v. Canada,Footnote 51 tribunals reconcile the two approaches by comparing foreign investors with domestic investors in the same economic sectors to find out whether they are in similar circumstances. In Olin v. Lybia, the tribunal also upheld this approach by stating that the fact that two factories operated in the same business sector indicates the existence of a similar location.Footnote 52

‘The same economic sector’ approach seems more reasonable. Under this approach, foreign investors who claim that a host state's data localization legislation violates national treatment in international investment treaties must first prove that they are in the same economic sectors as the relevant domestic investors. There is no worldwide uniform standard to classify economic sectors. Every state has its own criteria to classify the state's economic sectors concerning information and technology industries. For example, currently, China adopts the Catalogue of Industries for Encouraging Foreign Investment (Revision 2020), while the United States, Canada, and Mexico apply The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Therefore, whether or not a foreign investor is in the same business sector as a domestic investor involves examining the host state's industry catalogue.

3.2.1.2 The State's Regulatory PurposeFootnote 53

Some tribunals also take the regulatory purpose of the host state into account in examining whether the foreign and domestic investors were in like circumstances or not.Footnote 54 This approach was taken in UPS v. Canada, where the tribunal held that only Canada Post could fulfill Canada's universal service obligation to attain the Publications Assistance Program's objective (PAP).Footnote 55 Given the objectives and operations of the PAP, UPS was not in like circumstances with Canada Post, and the differential treatment was therefore justified.Footnote 56

As promoting the digital economy becomes part of many states’ national strategy, some digital corporations are becoming increasingly important to the fulfillment of their home states’ digital economic regulatory purposes. Article 1 of the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 refers to promoting ‘more open, equitable, and reciprocal market access’ in extensive fields, including trade, investment, and intellectual property.Footnote 57 If the US corporations submit that only the US corporations can fulfill the objectives and operations of the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015, they will be considered not to be in like circumstances with foreign investors in the same economic sectors. In such circumstances, the UPS v. Canada approach is very likely to be abused and would render the national treatment clause useless. Therefore, it would be better to restrict the UPS v. Canada approach's application or at least interpret it strictly. For example, there should be an explicit link between the state's regulatory program and the specific domestic investor.

3.2.2 Less Favorable Treatment

As an essential element of national treatment, ‘no less favorable treatment’ requires the host state to ensure equality of competitive opportunities between domestic and foreign investors.Footnote 58 In many cases, it has been confirmed that only when a claim of having received less favorable treatment is based on nationality would the discrimination be considered by an arbitral tribunal to be a violation of national treatment.Footnote 59 As explained in Section 1 of this article, the requirements of data localization restoration, infrastructure localization, and service localization apply equally to domestic and foreign investors. Therefore, there is usually no de jure discrimination. Rather, the core issue is whether data localization legislation results in de facto discrimination towards foreign investors.

3.2.2.1 The Level of Treatment

It is not reasonable that differential treatment alone should give rise to a conclusion of nationality-based discrimination. Indeed, completely identical treatment is almost impossible to implement. The US Restatement describes the principle of non-discrimination in section 712 (3) as an unreasonable distinction.Footnote 60 Cases such as Marvin Feldman v. Mexico also hold that differential treatment could be taken as less favorable treatment to establish a denial of national treatment insofar as the difference amounts to de facto discrimination.Footnote 61

Concerning the extent of differential treatment that constitutes de facto discrimination, there are generally three approaches taken by international tribunals. The first approach is in the S.D Myers v. Canada case, where the tribunal held that the key to determine whether the foreign investor received less favorable treatment lies in ‘whether the practical effect of the measure is to create a disproportionate benefit for nationals over non-nationals’.Footnote 62 The second approach assesses whether the measures lead to an unreasonable distinction between foreign and domestic investors. This approach was upheld in the three cases of Feldman v. Mexico, Archer & Lyle v. Mexico, and Clayton/Bilcon v. Canada.Footnote 63 For example, in Clayton/Bilcon v. Canada, the tribunal found that Canada made an unreasonable distinction by applying different modes of review and evaluative standards to Bilcon and domestic investors.Footnote 64 The recent approach taken in Apotex v. the United States revealed a tendency to lower the threshold for host states’ measures to violate national treatment. In Apotex v. the United States, the tribunal held that the treatment must have some not-insignificant practical negative impact on foreign investors.Footnote 65

These different approaches may lead to different answers to whether data localization legislation results in less favorable treatment to foreign investors than domestic investors. Following the S.D Myers v. Canada approach, the critical issue is whether data localization legislation would create a disproportionate benefit for nationals over non-nationals. Admittedly, data localization results in negative economic consequences for both domestic and foreign investors, but there are no data showing that domestic entities will thereby be granted considerable advantages over foreign corporations.

The Apotex v. the United States approach renders a comparison of the impact of data localization measures on domestic investors as compared to foreign investors unnecessary. Instead, measures must merely have some not-insignificant practical negative impact on foreign investors.Footnote 66 In this case, without a comparison of the impact on foreign investors and on domestic investors, data localization legislation is easily regarded as ‘less favorable treatment’ with reference to this approach for having negative economic impact on foreign investors.

The Feldman v. Mexico approach requires the tribunal to determine whether the measures lead to unreasonable distinctions between the treatment of foreign investors and domestic investors. The key to assess whether there are ‘unreasonable distinctions’ is to examine whether there are rational bases to justify differential treatment of the host states.

3.2.2.2 Rational Bases to Justify Differential Treatment

If there is differential treatment, some tribunals assess whether there are rational bases for the host states to treat foreign investors differently. This approach was adopted in Feldman v. Mexico and Pope & Talbot v. Canada. Footnote 67 Suppose the host states can provide rational explanations which prove that their treatment does not bring about unreasonable distinctions between foreign investors and domestic investors. In such a case, there is no ‘less favorable treatment’ for foreign investors.

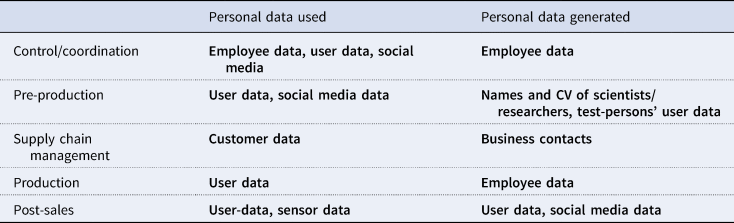

Not all data bear the same importance and sensitivity to states. In the case of data localization, many pieces of legislation focus on the nature and categories of data rather than the nationality of the data owners. As indicated in Table 1, personal data are used and generated throughout all production processes, including control and coordination, pre-production, supply chain management, production, and post-sales. The sensitivity of personal data in each process varies.Footnote 68

Table 1. Examples of personal data in production

Source: Swedish Board of Commerce. 2015. “No transfer,no production-a report on cross-border data transfers, global value chains and the production of goods.” European Commission, April 28, 2015. https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/publ-no-transfer-no-production.pdf.

Therefore, many states treat different categories of data differently in their domestic legislation. For example, Nigeria requires all information and communication technology companies to host all subscriber and consumer data locally within the country, and data and information management firms to host government data locally within the country.Footnote 69 To distinguish different data, many states attempt to define the critical information infrastructure (CII) and enhance the protection of data concerning the CII.Footnote 70 The CII is essential to a state's national security and functioning of industrialized economies,Footnote 71 so there is sometimes special protection of data concerning CII. An example is China. Based on the definition of the CII in Article 31, Article 37 of China's Cybersecurity Law requires the CII operators to store within mainland China all personal information and important data gathered or produced within the mainland territory. If it is necessary to transfer data across borders, a security assessment of the locally stored data is required. Rationales for differential treatment can also be found in other domestic legislations. The EU focuses on states’ ability to protect data. Article 45(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) allows the transfer of personal data insofar as a third country or an international organization is able to provide ‘an adequate level of protection’. Under this circumstance, the transfer does not need to be specifically authorized. Both the categorization of the data and the requirement of ‘adequate protection’ in domestic legislation can be taken as rationale bases for the host states to adopt data localization measures and therefore can justify the states’ differential treatment.

3.2.3 Implicit or Explicit Exceptions

3.2.3.1 The Jurisprudence of Exceptions to Maintain the State's Sovereignty

International investment treaties are designed with a balance of different values. There is a tendency that more and more international investment treaties include exception clauses to achieve the goal of value balance,Footnote 72 which reveals that the development of a value will call for the compromise of another value. If the foreign investors and domestic investors are in like circumstances, and the host state's regulatory measures provide less favorable treatment to foreign investors, tribunals following the ‘three-step approach’ will examine whether there are any exceptions which justify the differential treatment.Footnote 73 One typical exception includes measures to maintain the state's sovereignty.

In the well-known Island of Palmas case, Judge Max Huber said that:

[s]overeignty in the relations between states means independence. Independence in relation to area of the globe is the right to exercise his functions within the state, excluding any other State.Footnote 74

Adopting this definition of the term, sovereignty is closely related to international relations and is both a legal and political concern. With the economic boom brought by the Scientific-Technical Revolution, states became more involved in international trade and investment. The concept of ‘economic sovereignty’ was proposed in the 1960s. In 1974, the United Nations General Assembly declared the establishment of a new international economic order in respect of the principle of ‘full permanent sovereignty of every State over its natural resources and all economic activities.’Footnote 75 In the same year, in the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, the United Nations General Assembly further explained the content of ‘full permanent sovereignty over national resources’ by declaring that ‘every State has and shall freely exercise full permanent sovereignty, including possession, use and disposal, over all its wealth, natural resources and economic activities’.Footnote 76 With the economic attribute of ‘state sovereignty’ becoming more prominent, the term is more characteristic of states’ domestic constitutional provisions than the original legal status in the international relations.Footnote 77

Admittedly, the concept of sovereignty evolves according to the demands of each era. With the digital era, scholars have become aware of the importance of ‘data sovereignty’ as an aspect of state sovereignty, even as early as 2000.Footnote 78 There are both broad and narrow definitions of data sovereignty. To define it broadly, data sovereignty refers to state sovereignty concerning national security and individual sovereignty concerns an individual's control over its privacy.Footnote 79 In a narrow sense, by focusing on the state's part, data sovereignty is defined as a state's authority to control its public information assets,Footnote 80 or a nation's right to collect and manage its own data.Footnote 81 This article adopts the narrow definition, which discusses only a state's data sovereignty rather than individuals’ rights.

From 2007, the US National Security Agency initiated a surveillance program code-named PRISM, which collected internet communications from various US internet companies. After Edward Snowden revealed the PRISM surveillance program to the public in 2013, the maintenance of states’ data sovereignty became a central concern to many countries.Footnote 82 Several states recognized the right to self-preservation in their domestic legislation;Footnote 83 and the right to self-preservation incorporates digital sovereignty in this digital era. France declared their intention to build a state of digital sovereignty.Footnote 84 Even the US, which declares its commitment to a digital economy through a free and open Internet and commerce without borders in its the Digital 2 Dozen, is just above the average level of digital restrictiveness among 64 countries because of various restrictive policies in digital trade in the US.Footnote 85 For example, under the USA PATRIOT Act, the government can intercept any data coming inside the country for security purposes.Footnote 86

Exceptions aimed at balancing states’ regulatory power regarding the protection of foreign investors are embedded in several international investment treaties. Some states require data localization in their domestic legislation and maintain their data sovereignty in exceptions in international investment treaties.

3.2.3.2 Explicit Exceptions in International Investment Treaties

The benefits of data localization for security and confidentiality are indeed context dependent for states. The privacy and confidentiality of information are not secured in cross-border data transfer.Footnote 87 The risk of exposure increases when data are transferred with every new intermediary. Thus, information stored locally by users may be better protected than information transferred abroad to a third party.Footnote 88 By reducing the risk of data exposure when they are transferred by a new intermediary, data localization can help protect privacy and information confidentiality for some states without a powerful data security system, i.e., for states that do not possess advanced encryption to secure data transferred abroad and that prevents remote attacks.

Data protection is a newly emerging concern for states with the coming of the digital era. Few early international investment treaties explicitly refer to data protection, either in exceptions to national treatment or general exception clauses. However, this situation is changing as more states realize the importance of data sovereignty. As the representative economic entity that emphasized protecting data as protecting fundamental human rights, the EU has explicitly included data protection as an exception in some recent EU FTAs, such as the 2016 EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the 2018 EU–Singapore FTA. Probably included as a means to strengthen the influence of the GDPR, Article 8.9(1) of the CETA reaffirms the states’ right to ‘regulate within their territories to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as … social or consumer protection’, and Article 28.3 explicitly refers to data protection as a general exception.Footnote 89 Further, Article 2.3(3)(e) of the EU–Singapore Investment Protection Agreement explicitly takes necessary measures for ‘the protection of the privacy of individuals in relation to the processing and dissemination of personal data and the protection of confidential of individual records and accounts’ as exceptions to national treatment requirements.

In future international investment treaties, more states are likely to follow the EU practice of explicitly including data protection in the exceptions, either as exceptions to national treatment or in general exceptions. There are two reasons for this. First, the legitimacy crisis of international investment arbitration arises from the treaty interpretations of international arbitral tribunals which tend to over-protect the foreign investors’ interests. This reminds the host states of the importance of strengthening their regulatory power.Footnote 90 With the reform of the investor–state dispute settlement mechanism, there is a tendency that states place more emphasis on the exception clauses in international investment treaties than ever. This is demonstrated by the number of recent international investment treaties (2012–2014) that include general exceptions, which is about five times greater than the early international investment treaties (1962–2012).Footnote 91 Hence, there appears to be a trend towards states using exceptions more frequently to maintain their state sovereignty. Second, several states show their serious concerns about data protection in domestic legislation.Footnote 92 According to the basic principle of pacta sunt servanda, states should bear responsibilities if they violate their treaty obligations. Domestic legislation should not conflict with the states’ commitment in international investment treaties. Therefore, states must clarify the legitimacy of data localizations in international investment treaties to make the legislation consistent with the states’ treaty obligations.

3.2.3.3 Implicit Exceptions in International Investment Treaties

Even though, so far, few states have explicitly referred to data sovereignty or data protection as exceptions in international investment treaties, there are still other possibilities for the host states to invoke non-precluded measures (NPM) clauses to secure their data sovereignty. With the number of NPM clauses in modern international investment treaties increasing,Footnote 93 it is necessary to consider whether NPM clauses in international investment treaties implicitly encompass the host states’ right to regulatory cross-border data transfer. More specifically, is it possible for the host states to invoke NPM clauses, including protecting national security, maintaining public order, or public morality to regulate cross-border data transfer?

Since World War II, the NPM clause has traditionally been embodied in US friendship, commerce, and navigation treaties. The NPM was then incorporated in the US model BITs. Two typical NPM clauses allow the states to take actions inconsistent with the treaty to protect national security or essential security and maintain ‘public order’ or ‘public morals’.Footnote 94

Indeed, indicated below in Table 2 are the regulatory objectives that motivate some states’ data localization requirements. The primary concern for states appears to be privacy regulation and cybersecurity. It is unsurprising that cybersecurity is a state's essential concern and constitutes a significant part of a state's national security. The Snowden leaks reminded most countries of the US's superior capacity for electronic surveillance.Footnote 95 In this sense, states at a comparative disadvantage in surveiling outside attacks and threats tend to use data localization legislation to reduce the risk to their cybersecurity.Footnote 96

Table 2. Data localization or storage requirements of representative states

Source: Lee-Makiyama, Hosuk. 2018. “Briefing note: AI & Trade Policy.” Tallin Digital Summit. https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/TDS2018-BriefingNote_AI_Trade_Policy.pdf.

Few investment arbitration cases, such as Thunderbird v. Mexico, have considered the meaning of ‘public morals’. An analysis of United States – Measures Affecting the Cross-Border Supply of Gambling and Betting Services (US–Gambling), which came before the WTO, can be of some assistance. In the US–Gambling case, the panel looked to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, and found that ‘‘public morals’ denotes standards of right and wrong conduct maintained by or on behalf of a community or nation.’Footnote 97 Furthermore, the Appellate Body reconfirmed on several occasions that states reserve the right to decide the level of protection of ‘public morals’.Footnote 98 Hence, the panel held that the prevention of underage gambling relates to public morals in the US–Gambling Case.Footnote 99 In Brazil – Certain Measures Concerning Taxation and Charges, the panel held that bridging the digital divide and promoting social inclusion is within the scope of ‘public morals’.Footnote 100 In European Communities – Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products, the panel found that the protection of animals is a public moral concern.Footnote 101 In China – Measures Affecting Trading Rights and Distribution Services for Certain Publications and Audiovisual Entertainment Products, the panel regarded that selling prohibited types of content could negatively impact China's ‘public morals’.Footnote 102 In this case, the concept of ‘public morals’ varies between different cultures, and the term is still regarded as vague and with a too wide scope because of the lack of a specific definition.Footnote 103 In this regard, some scholars propose to review the state's regulatory measure through the doctrine of necessity and proportionality.Footnote 104 Considering the functional link of the national treatment clause in WTO and international investment treaties,Footnote 105 similar language of ‘public morals’ in exceptions in both international investment treaties and GATT, as well as the referential significance of the WTO reports on investment arbitrations,Footnote 106 the interpretation of ‘public morals’ in the US–Gambling case can provide significant guidance. By applying the definition of ‘public morals’ in the US–Gambling case to international investment treaties, privacy is related to a state's ‘public morals’ because it denotes standards of right and wrong conduct, especially when data privacy is considered as a fundamental human right from the EU perspective. In this regard, states may invoke the exception of public morals when regulating cross-border data transfer.

4 An Example of Data Regulation in China Legislation and the Relations to its National Treatment Obligation

4.1 Data and ‘Investment’ in China's Domestic Courts and International Investment Treaties

All Chinese BITs have definitions of ‘investment’, though these definitions vary between treaties. A typical definition of ‘investment’ in Chinese BITs is ‘a claim to money or to any performance having an economic value’.Footnote 107 In this regard, whether China acknowledges data's economic value is important in applying the Chinese BITs. Though it may not be clear whether data qualifie as an ‘investment’ for international investment treaties,Footnote 108 the Beijing Intellectual Property Court has already confirmed that data are an asset, which falls into the typical definition of ‘investment’ in Chinese international investment treaties. In Beijing Taou Tianxia Technology Development Co., Ltd. v. Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that internet companies have property rights over data collected and stored as a matter of competition law. The Court pointed out that data have become a commercial asset and an important economic contribution to an enterprise. The acquisition and use of data can become a source of competitive advantage and create more economic benefits for internet enterprises. In this way, data are an important competitive advantage and commercial resource for network operators. Therefore, the court held that Beijing Taou had infringed on the Beijing Weimeng's business resources by unlawfully using Beijing Weimeng's user data.

In Meijing v. Taobao, the Taobao Company and the Meijing Company disputed the nature of digital products. The Taobao Company submitted that the digital product ‘Business Assistant’ was the Taobao Company's fruits of labor, and the original data and derivative data contained in the data content are the intangible assets of the Taobao Company, so the Taobao Company enjoys property ownership and competitive property rights over ‘Business Assistant’. The Meijing Company disagreed by stating that the data content used by the Taobao comes from the property rights of network users, so the Taobao Company should not have rights or interests to the data content. In this case, Hangzhou Intermediate People's Court of Zhejiang Province upheld the findings of the Court at first instance. It held that though the data contained in ‘Business Assistant’ are derived from the original users’ information, the Taobao Company further developed the product through a specific algorithm after deep analysis filtering, refining integration, and anonymizing desensitization processing, thereby rendering it different from the unprocessed network data. The network operators should enjoy their own independent property rights for their big data products. In other words, network big data products have already become a valuable property right for network operators.Footnote 109

Considering the economic value confirmed in the above two cases in China's domestic courts, treaty interpretation principles indicate that data should be recognized as an investment in Chinese BITs.Footnote 110 Alternatively, if we apply the Salini test, as Chinese domestic courts have and thus confirmed that data products confer property rights, data qualifies as an ‘investment’.

4.2 Data Regulation and China's National Treatment Obligations in International Investment Treaties

Now that the Chinese court accepts at least commercial data as an asset, and considering that the definition of investment in Chinese BITs is based on the laws and regulations of China,Footnote 111 data are likely to fall under the definition of investment in Chinese international investment treaties. The next issue is whether data localization legislation violates China's national treatment commitments.

Approximately half of Chinese BITs include a national treatment clause.Footnote 112Modern Chinese international investment treaties appear to provide greater protection for foreign investors than the older generation of Chinese international investment treaties.Footnote 113 In 2013, China agreed with the US to adopt pre-establishment national treatment with a negative list in any future China–US bilateral investment treaty.Footnote 114 In a groundbreaking move, China adopted the pre-establishment national treatment with a negative list in the new China's Foreign Investment Law that came into force on 1 January 2020, so that national treatment would be extended to the pre-entry phase. The recent China–EU Comprehensive Investment Agreement also adopts the pre-establishment national treatment approach, which enlarges the scope of protection of foreign investors. While opening up is expanded and deepened through the adoption of the pre-establishment national treatment with a negative list, the ‘safety valves clauses’ in Chinese international investment treaties are insufficient. On the one hand, there are no clauses specifically for the cross-border data transfer in valid Chinese international investment treaties, because most valid Chinese international investment treaties were signed in the 1990s. On the other hand, though there are general exception clauses in a limited number of Chinese international investment treaties, such as the 2012 China–Canada BIT,Footnote 115 most Chinese international investment treaties do not contain exceptions for essential security interests, public order, or public morals.

As mentioned above, exceptions in IIAs play significant roles in setting out the legal bases for limiting cross-border transfer of data for not violating the national treatment obligation in international investment treaties. China has made an effort to set out the legal bases of its domestic data regulation legislation, but future work awaits. There are data localization requirements in several Chinese laws. For example, Article 37 of China's Cybersecurity Law states that ‘personal information and important data collected and produced by critical information infrastructure operators during their operations within the territory of the People's Republic of China shall be stored within China’. According to Article 40 of China's Personal Information Protection Law:

[c]ritical information infrastructure operators and the personal information processors that process the personal information reaching the threshold specified by the national cyberspace administration in terms of quantity shall store domestically the personal information collected and generated within the territory of the People's Republic of China.

Both articles refer to the CII. There are rational bases for the Chinese government to require personal information and important data collected or generated by CII operators in China to be stored within the Chinese territory. In this regard, the establishment of a categorized and hierarchical data protection system is necessary, which is specified in Article 21 of China's Data Protection Law. To clarify the definition of CII and ways to protect it, the Regulation on the Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure (‘the Regulation’) was published in April 2021.Footnote 116 In Article 2, the Regulation further clarifies the scope of CII as pieces of infrastructure ‘in the event of damage, loss of function, or data leak,’ may ‘seriously endanger national security, national welfare, or the livelihoods of the people, or the public interest’. To further define CIIs, the regulators for the industries and technology fields mentioned in the above Article 2 of the CII Rules need to promulgate rules to identify CIIs in their respective industry jurisdictions.Footnote 117 In this way, the Regulation generally sets out the legal bases for limiting the cross-border transfer of data generated by CIIs.

Apart from the need to establish a categorized and hierarchical data protection system and to further define CIIs in respective industries, the integration of Chinese international investment treaties and China's domestic legislation needs improvement. Under Article 28 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, ‘a party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty’. In this sense, if future Chinese international investment treaties include data regulation provisions, these provisions should be consistent with the data and investment regulation rules in China's Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, Personal Information Protection Law, and Foreign Investment Law. In this regard, it will be important to clarify such essential definitions as ‘public morals’, ‘public order’, and ‘individual privacy’ in China's domestic data legislation.

The year 2021 has witnessed China's significant improvement of its data regulation legislation with China's Data Security Law and China's Personal Information Protection Law coming into force,Footnote 118 then it is likely to see China discuss ‘new issues’ more frequently in the negotiations of international investment treaties. Future negotiations and modifications of Chinese international investment treaties may require the Chinese government to emphasize cross-border data transfer clauses and exception clauses.Footnote 119 Considering that the US, the EU, and China have created three distinct data realms with different approaches to data governance,Footnote 120 it would be difficult for China to reach an agreement with the US and the EU on cross-border data transfer clauses in investment treaty negotiations. Unlike the US and the EU, China appears to have been inactive in the ‘new issue’ of data flows. However, after China's data regulation legal framework has preliminarily taken shape, China may be more willing to discuss the ‘new issue’ in future IIA negotiations. Noting that the Trump administration pressed China to loosen the implementation of the Cybersecurity Law in the trade war negotiation,Footnote 121 the South–North conflict could become more severe when the negotiation focuses on digital clauses or exception clauses. The US is firmly pushing its digital policies represented by Digital 2-Dozens in its BIT negotiations, aiming to strengthen protections for free cross-border data flows. However, China emphasizes the protection of the data generated by CII in light of concerns about national security, national welfare or the livelihoods of the people, or the public interest, and will thus restrict cross-border data transfer. If the China–US BIT negotiation restarts, it will be difficult for the two states to reach an agreement on the digital clause.

According to the available information, the EU and China have not reached an agreement on data regulation in the recent China–EU Comprehensive Investment Agreement.Footnote 122 Though there is data localization legislation in China and the EU, it is difficult for the China–EU BIT to conclude digital clauses. First, the IT enterprises of the EU are not as competitive as the Chinese IT corporations in the global market; thus, the EU may generally be more conservative towards cross-border data transfer. In other words, the EU may be keen to develop its IT industry and expand its internal market to replace the global IT competitors, and may therefore be less motivated to push for binding cross-border data transfer provisions.Footnote 123 Second, China is not on the list of non-EU states that are capable of providing adequate data protection recognized by the EU Parliament,Footnote 124 which reveals the differences in the understanding of data protection between China and the EU. Third, the EU already has an integrated legal system of data protection while China's data protection and regulation legislation is still in progress. Considering the disputes on cross-border data transfer, China can rely more on exception clauses to maintain its right to data regulation. The negotiation and upgrade of Chinese investment treaties should especially emphasize general exceptions and essential security interest exceptions.

5 Conclusion

Data are not only a valuable resource, but also an investment for the purposes of IIAs. With the rapid increase in cross-border data transfers, traditional IIAs need to reform in this digital era. Data localization is a new type of regulatory measure used by host states. Data localization measures may negatively impact foreign investment. However, from a legal perspective, there is no one-size-fits-all answer about whether data localization legislation violates national treatment in IIAs.

This article has sought to demonstrate that applying the ‘three-step’ approach concerning international investment arbitral cases establishes that a state's domestic legislation and technological capability each plays a critical role in assessing the legality of data localization measures with respect to national treatment in IIAs. Whether the foreign investor and domestic investor are in the same economic sector depends on the domestic catalogues of foreign investment, which vary between host states. In addition, how data localization is defined in domestic legislation determines whether there are rational bases for the host states to treat a foreign investor and a domestic investor differently. Furthermore, although only very few current IIAs explicitly list data protection as an exception to either national treatment or the whole treaty, some IIAs at least implicitly include data protection through exceptions relating to a state's essential security, public order, or public morals.

China is speeding up its domestic legislation to regulate cross-border data transfer through publishing regulations to the Cybersecurity Law and the Data Security Law. China needs to carefully set out the legal bases for limiting cross-border transfer of data in Chinese investment treaties and its domestic legislation. More comprehensive data regulation legislation is anticipated to ensure China's regulation complies with its IIAs.