Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows. If only you knew how strange it is to be there. It is a world without sound, without colour. Everything there – the earth, the trees, the people, the water and air – is dipped in monotonous grey. Grey rays of sun across the grey sky, grey eyes in grey faces, and the leaves of the tree are ashen grey. It is not life but its shadow, it is not motion but its soundless spectre.

Maxim Gorky, 4 July 1896What I saw was the Count's head coming out from the window. I did not see the face, but I knew the man by the neck and the movement of his back and arms. . . . I was at first interested and somewhat amused, for it is wonderful how small a matter will interest and amuse a man when he is a prisoner. But my very feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over the dreadful abyss, face down, with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings. At first I could not believe my eyes. I thought it was some trick of the moonlight, some weird effect of light and shadow, but I kept looking, and it could be no delusion. . . . What manner of man is this, or what manner of creature, is it in the semblance of man? I feel the dread of this horrible place overpowering me; I am in fear – in awful fear – and there is no escape for me; I am encompassed about with terrors that I dare not think of . . .

Jonathan Harker, 12 May 189-The years 1895 to 1897 are a memorable period in the history of scientific and aesthetic analysis of the human body's movements, physical gestures, and signs. Not only are these the years of the parallel emergence of the early cinema and psychoanalysis, but they are also the years in which Henri Bergson's Matter and Memory (1896) and Max Nordau's Degeneration (1892; first English translation 1895) entered the literary marketplace as two very different studies of the temporality of the body and its symptoms of temporal inscription. If we add to this brief catalogue the continuing significance of the serial photography of Étienne Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge throughout the 1880s and 90s, the establishment of Thomas Edison's Black Maria studio, and Jean Martin Charcot's and Albert Londe's photographic research into the gestures of hysterical bodies, we see that the mid-1890s offered cultural critics an extraordinarily healthy dose of scientific (and not so scientific) thinking about the mechanics of the modern body in motion, and its various nervous ticks, convulsions, symptoms, and unconscious motivations. Individually, these examples have been well-explored from cultural and historical perspectives, of course, but they do seem to culminate in a singular cultural fascination with the scientific aesthetics of writing, reproducing, and managing the problem of motion in modern life.

Not coincidentally, Bram Stoker's Dracula first appeared in the British literary marketplace in 1897, just in time to offer its own commentary on the state of the body in this new age of cinematography – understood broadly as the writing or reproduction of movement. The novel's contribution to cultural debates about the degeneration of the species, and Stoker's adoption of the scientific thought of such notable figures as Nordau, Charcot, and Cesare Lombroso, are well known by now. Yet, while there has always been an intimate correspondence between Dracula and the cinema, the novel's debt to fin-de-siècle theories of the moving image have yet to be explored to their fullest potential. This essay intends to offer some insight into the cultural affinities between the novel and the emergence of cinematography, or what Tom Gunning and others have referred to as the “culture of attractions” at the turn of the century.Footnote 1 The two excerpts quoted above will condition my reading of the novel, and as such, I will return to them frequently throughout the following pages. Briefly, at the outset, we start with the idea that Maxim Gorky's review of the early cinema and Jonathan Harker's encounter with the image-movement of Dracula's body are both kinds of primal scenes of the moving image. The hysterics produced in both, whether feigned or truly symptomatic, are indicative of modern anxieties about the seductive dangers of cinematographic or moving bodies on screen or in the pages of late-Victorian gothic fiction. Fundamentally, Stoker's Dracula emerges in 1897 as a cultural document profoundly preoccupied not so much with technologies of inscription, as many critics have argued, as with fin-de-siècle thought about the experiences of modern time and movement.

The cinematograph made its first “official” appearance in Paris in December of 1895, entering a marketplace that had become increasingly aware of the mass appeal of large-scale visual images, moving or otherwise.Footnote 2 In the following pages, I interrogate some of the contradictions at the heart of the early cinema's supposed revolution in scientific analysis of the human form through a reading of Stoker's gothic tale of vampire bodies. Gorky's review of the cinematograph above is one of the most eloquent of late-nineteenth-century responses to the flicker of images embodied by the cinema, even though we find in his account a profound uncertainty about the camera's reproduction of real life and its corresponding excess of signification.Footnote 3 For Gorky, and indeed for many contemporary reviewers of the film programs offered by the Lumières, Thomas Edison, and other prominent Victorian filmmakers, the cinema reproduced images of bodies that seemed to be haunted by the supernatural, and this was the case often despite claims that the cinematographic eye was infallible and only capable of reproducing real life as it really is. In contrast to the camera eye's scientific pretensions, the period's many projected filmic bodies presented spectators with “puzzling shadows and outlines struggling to realize some sort of coherence” (Auerbach 2). Like its many predecessors in the techniques of image production, the cinematograph produced a realm of shadows, ghosts and specters that had already been haunting theatres, music halls, and photographs for decades.Footnote 4 Despite the cinematic body's indexicality with real life and real movements, the remains of the supernatural were entangled with a fundamental experience of lifelessness that assaulted spectators with an excessive reality. The cinema reproduced the gait, gestures, and movements of real bodies, but it also drained the vitality of life from them, offering instead an explosion of visibility both real and extraordinarily unreal. The cinema gave birth to a rational, scientific invasion of the undead (a carryover from the nineteenth-century tradition of the phantasmagoria) that would define the very experience of modernity.

Whether or not Stoker was aware of the stark similarities between his undead vampires and the early cinema's animated corpses, Dracula does contain a noticeable anxiety about scientific method that seems to play on the crisis of perception often exhibited by early cinema filmmakers and spectators. One need only look closely at the excerpt from Harker's journal above to see this crisis at work. Tricks of perception confound the rational perspective of an emerging young barrister from London, in ways both terrifying (for Harker) and sensational (for Stoker's readers). Dracula's movements amuse Harker at first, but then shift to a moving image of terror when he realizes the truth of their defiance of the laws of physics. Harker's reliance on recording, in precise detail, all that he experiences at Castle Dracula comes from his participation in a new class of professional men, as Nicholas Daly has argued. Harker's experiences in the Carpathian Mountains are thus both a threat to, and a rationale for, the novel's bureaucratization of perception. His attempts to record all he has observed, and only the facts of his imprisonment, serve as an early motivation for the eventual “team of experts” (Daly 30) that will track Dracula's movements upon his arrival in London. At the same time, the vampire images that assault Harker during his imprisonment radically resist the bureaucratizing impulse at the heart of professionalization, while also referencing a persistent concern about the seductive nature of moving forms and time-based images. The professional vampire hunters that will eventually track Dracula's movements through London are part of a larger movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century towards a time-based economy. Yet, fundamentally we should also see the vampire's movements as a kind of symptom of bureaucratic notions of time and temporality. Although ancient and supernatural, Dracula's movements are thoroughly modern in their effect on spectators and observers like Harker (both in Castle Dracula and during his second encounter with the Count in London).

The moving body was at the heart of numerous scientific and aesthetic discourses in the final two decades of the century, from Muybridge's and Marey's photographic studies of bodies in motion and Bergson's investigations into the nature of movement and duration to the early cinema. The goal of such projects (the storing and reproducing of every minute increment of Time), and its inevitable failure, speaks to a desire at the turn of the century to not only capture a moment, as Leo Charney has suggested, but also to “rescue the possibility of sensual experience in the face of modernity's ephemerality” (“In a Moment” 279). While literary criticism of Dracula frequently situates Stoker's explicit erotics of blood and penetration within the cultural context of fin-de-siècle debates about decadence and degeneration, I want to suggest an alternative approach to the explosion of visibility in the novel's early chapters, one that both compliments and challenges much recent critical interest in the novel's debt to communications technologies and graphic inscription.Footnote 5 In the two excerpts cited at the outset of this essay, we find two descriptions of seemingly supernatural experience, two immobilized and delirious spectators, and two encounters with the undead. Dracula produces a series of moving images of the vampiric body that are analogous to late-Victorian engagements with the modernity of the cinematic image. Like the appearing and disappearing screen bodies in the films of Georges Méliès, one of the early cinema's most prominent pioneers, Dracula consistently stages the visibility of the vampire body within the context of the spectacle of modern illusion, and thus produces an experience of the moving image that radically questions the team of expert's attempts to thwart Dracula's invasion of Metropolitan London.Footnote 6 This consistent questioning, or undoing, of scientific method emerges primarily through the seduction of the moving image. The temporality of the undead plays on the fears of the spectator in both Castle Dracula and the cinema theatre, serving as a reminder of the perverse fantasy of the Real, and the seductive core of modernity's production of ephemeral, and indeed ethereal, spectacles.

Jean Baudrillard has argued, in an influential discussion of the state of seduction in the age of modern technologies of reproduction, that the screen body today has become entangled with modes of production that attempt to penetrate to the core of reality through the denial of the artifice of appearance. Situating the modern production of sexuality (via Freud and Foucault) within an ages-old attempt to end the “seduction of appearances” (1), Baudrillard posits a theory of the seductive image that had already proved to be frustrating for early cinema pioneers and their scientific predecessors. “Seduction,” Baudrillard writes, “is, at all times and in all places, opposed to production. Seduction removes something from the order of the visible, while production constructs everything in full view, be it an object, a number or concept” (34). For Baudrillard, reality lacks interest because it is “a place of disenchantment, a simulacrum of accumulation against death” (46). The realm of seduction, in contrast, operates within and against modern scientific regimes, consistently frustrating perception – whether subjective or technological – through a play of appearances.

And this is precisely what happens in Stoker's novel: the vampire-image (its movements, appearances, and disappearances) consistently antagonizes the senses through a series of seductive encounters, in which the vampire-image never fully presents itself according to a logic of production and complete visibility, despite Van Helsing's insistence later on in the novel that Dracula's movements betray his criminal, atavistic nature. Harker's early encounters with undead images during his imprisonment at Castle Dracula reveal a radical questioning of the production of reality by modern communications technologies: phonography, photography, telegraphy, and telephony, most notably. This is the case for both Harker and his fellow vampire hunters and Stoker's readers, who, given the novel's documentary form, never fully encounter the vampire except through second-hand accounts. The reduction of the vampire to a mere trace picks up steam in the second half of the novel, after the vampire hunters’ final encounter with the undead Lucy Westenra. Her “white, dim figure” (236), described by Dr. Seward, flits towards her own tomb, presenting a marked contrast to the rustle of “actual movement” (237) heard in some nearby bushes where Van Helsing has discovered Lucy's potential victim, a helpless child. This scene and that of the vampire hunters’ eventual destruction of the impure, un-dead Lucy a few entries later comprise two striking examples of the seduction of the moving image in the 1890s, for not only does Seward describe Lucy's vampire body as “more radiantly beautiful than ever” (238), but her body – its shape – unsettles the predilections of her suitors. “Lucy Westenra, but yet how changed,” Seward writes before ultimately describing the loathing he has for this image-body that once was the woman he desired as a wife: “I call the thing that was before us Lucy because it bore her shape. . . . At that moment the remnant of my love passed into hate and loathing; had she then to be killed, I could have done it with savage delight” (249). From this point on in Dracula, the bureaucratic elements of the vampire hunters’ “campaign” (366) against the Count efface imperfectly the remnants of such early encounters with the vampiric moving image. The seduction of appearances, though, remains a troubling anxiety throughout Stoker's novel, in ways strikingly, yet only analogously, cinematic.Footnote 7

The endless reincarnations of Dracula in popular media have resulted in a widespread understanding of the vampire as a romantic figure, albeit one with a dangerous appeal for the disaffected, the lonely, and the gothic. The undead are everywhere, and have been everywhere, in modern media from cinema to television, fiction to graphic novels, and theme parks to Las Vegas motion simulation rides. Most recently, the success of Stephanie Meyer's Twilight series and their film adaptations demonstrates not only the vampire's legacy but also postmodern culture's ongoing fleshing-out of the vampire-image-as-character begun as early as some of the many twentieth-century film adaptations of Stoker's original. The identification with the vampire that Nina Auerbach recognized in the popular culture of the 1980s and 1990s has become a kind of hyper-identification in 2010.Footnote 8 No longer underground, vampires have become media darlings as even major America television networks and cable distributors scramble to profit from the cult of the undead. Today's vampire-as-commodity has effectively reified the seductive vampires of Stoker's original. As a result, new readers of Dracula are often surprised at the dialectic of visibility/invisibility in the novel, in which undead bodies resist complete embodiment through their many seductive tricks, illusions, and hauntings, and the extent to which the novel's closure of that dialectic in the form of a seemingly simplistic adventure romance seems strangely hap-hazard.Footnote 9

The year or so that separates the “official” birth of the cinema and the publication of Stoker's novel has led to some frustrating inconsistencies for critics interested in Dracula's possible cinematic origins. Much of this frustration comes from a type of historiography that actually fuels Baudrillard's argument about seduction. As critics and historians, we look for direct influences between one cultural phenomenon and another. We refuse to be seduced by the intriguing possibilities of un-corroborated affinities or surface similarities, even while the question of “what might have been?” functions as a kind of pleasurable intellectual dilemma. This is especially the case with Stoker's novel and its possible debt to cinematography. Despite its technological arsenal of typewriters, phonographs, and telephones, the only late-Victorian visual technology present in Dracula – Jonathan Harker's Kodak photographs of the Count's new London property at Carfax Abbey – is so obscure and inconsequential as to suggest an explicit effacement of the visual from the novel's repertoire of technologies. Given the novel's obsession with documenting and storing the evidence of Dracula's movements, and its resulting doubt about the reliability of the senses, it is astounding that Harker never chooses to turn his Kodak camera on the Count as evidence of his experiences in the Carpathian Mountains. As various nineteenth-century theories of photography attested, the taking of a photograph was often understood as the equivalent of a vampiric act – an emptying out of the vitality that constitutes a life, but also the process of storing eternal celluloid bodies.Footnote 10 To this end, Jennifer Wicke suggests that “it is possible to speculate that if a vampire's image cannot be captured in a mirror, photographs of a vampire might prove equally disappointing” (473). Given the novel's almost-obsessive anxiety about the nature of the vampire image, and its resulting crisis of subjectivity, critics are often left to ponder what might have been had Stoker developed further his mention of Harker's Kodak camera.

If the novel itself seems resistant to a direct cinematic (or photographic) influence, it does nevertheless profess a fascination with the spectacle of visual representation. We might turn here to Stoker's career at Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre as a source for the novel's numerous visual analogies (the picturesque, the pantomime, the diorama) in its early entries. As acting manager of one of London's most well-known theatres, Stoker would have been aware of the latest exhibitions of moving photography in neighboring music halls and theatres throughout the 1890s. Even so, literary critics and biographers have yet to discover any concrete evidence of a cinematic influence in the novel.Footnote 11 Lamenting these realities, David J. Skal has at least offered a consolatory suggestion that, “had motion pictures been sufficiently developed at the time,” [Stoker] would quite likely have been intrigued by the possibilities of film as film would later become intrigued with Dracula” (25). Likewise, Ronald R. Thomas offers a similar consolation in his claim that Stoker may have attended a screening of an 1896 vampire film by Méliès. Thomas refers to Le Manoir du diable (1896), a short film depicting a bat flying into an ancient castle while transforming magically, through developments in stop-motion cinematography, into an image of Mephistopheles. Méliès's devil-figure conjures up a young woman and a series of supernatural creatures from a magic cauldron. The short film comes to a conclusion as one of the conjured creatures brandishes a crucifix in an effort to force the devil away, thus bringing the vampire-cinema analog to a startling moment of clarity. Often understood to be the cinema's first vampire film, Le Manoir emphasizes the intersections of magic, the supernatural, and the experience of mechanical reproduction through a series of images that details the sudden appearance and disappearance of moving bodies intended to assault the spectator with the force of the occult.Footnote 12 Despite the intriguing affinities between Stoker's novel and this early vampire film, Thomas can only suggest that “it is entirely possible, even likely, that the film was seen by Stoker” (303). The possibilities are seductive, leading one astray from the right path of literary history, because the literary critic must resort to conjecture and speculation in forging such a link. Both Skal and Thomas also turn to the revisionary historicism of Frances Ford Coppola's 1992 film adaptation of Stoker's novel, which imagines the possibility that Dracula would have been compelled to attend a screening of the cinematograph upon his first arrival in London. More than any other film adaptation of Dracula, Coppola's draws explicit connections between the cinema and the undead, but as a consequence, it has also limited the discussion of the novel's cinematic heritage to a type of technological determinism that can only see influence where there is direct evidence. Neither Skal nor Thomas, it seems, has been fully seduced by the vampiric affinities between Dracula and the cinematography of the 1890s, preferring instead to let the evidence (or lack thereof) remain in a state of conjecture.

My intention here is not to suggest that readers of Dracula give in completely to the seduction of fascinating, yet uncorroborated, evidence for the novel's cinematic origins. I do think we need to be careful about how we phrase the discussion of cultural affinities between seemingly connected, yet disparate, events. This is the case especially if we are to highlight the seductive image-world of vampires at work in Stoker's novel. However, a little intellectual seduction might allow us to forge affinities between vampires and the cinematic undead in the 1890s, not in order to make arguments about a cinematic influence in Dracula but rather to suggest that seduction functions as a kind of keynote holding together both Stoker's undead bodies and those similarly undead moving images of the early cinema. Ian Christie suggests that the cinema's early years were but one response to a “life wish,” in nineteenth-century aesthetics, to take representational practices to their ultimate state of finality: a perfect copy of reality.Footnote 13 Yet this drive is but one facet of the project of moving images, which in their early cinematic moments had already demonstrated an awareness of the moving body's seductive dynamics. Both Gorky and Harker demonstrate an explicit attention to the details, and unsettling visibility, of bodies moving through the interplay of light and darkness. Indeed, there is no question that the novel's opening chapters, which constitute among other things Harker's initial thoughts on the unsettling visual experiences associated with the undead, are organized according to a common gothic strategy of associating the supernatural with the deprivation of the senses. The typical narrative of perceptual violation and deception of the senses in the gothic literature of the period emerges in Stoker's decision to isolate Harker's experiences in what is essentially a kingdom of shadows (like Gorky's description of the cinematograph theater hall), removed far from the rational time-oriented way of life in London: “it seems to me,” Harker observes, “that the further East you go the more unpunctual are the trains” (33). The novel's vampiric movements, and their corresponding demand for a type of enforced-spectatorship, play out in a virtual cinematographic theatre immediately after Harker's arrival, and eventual imprisonment, at Castle Dracula.

The young barrister's suggestion in his journal that Dracula's movements appear through an illusory interplay of light and shadow and tricks of the moonlight pinpoint Stoker's commitment to gothic narratives of the supernatural that question the scientific rationale of modern skepticism. Thus critics frequently suggest that the novel's early scenes at Castle Dracula construct a dichotomy between the Count's ancient powers and the modernity of the novel's typewriters, phonographs, telegraphs, and telephones.Footnote 14 This is certainly supported by Harker's own claim that his experiences in Transylvania are “nineteenth century up-to-date with a vengeance” and that the supernatural forces of the past have “powers of their own that mere ‘modernity’ cannot kill” (67). Yet Harker's encounters with Dracula and his vampire women are also suggestive of what Jean-Louis Comolli has identified as a distinctly modern “frenzy of the visible” (122) in the second half of the nineteenth century, an interplay between moving images of undead bodies (their sudden appearances and disappearances, materializations and dematerializations) and the seductive spectacle of modernity's erotically-charged cinematics of sexual invasion and assault. Linda Williams adopts Comolli's phrase in her provocative study of pornography, asserting that the frenzy of the visible of the early cinema serves as the prehistory to the viewing pleasures and powers of the pornographic image.Footnote 15 Stoker's novel participates in the period's frenzy of visible bodies, and more importantly situates it within a kind of pornographic seduction that produces “ghastly, chalkily pale” (156) feminine bodies drained of the vitality of life and reduced to “white, dim figure[s]” (236) that do not so much move in accordance with the gravitational pull of muscles and nervous stimulus as they flit like shadows moving through the flicker of dust and light. Such supernatural movements in both Dracula and the early cinema offer up images of modern bodies in motion that defy rationality and reason, even while they seem in fact to emerge from a common interest in the period with storing and reproducing the temporality of bodily inscription and movement.

Long before Baudrillard, then, we find commentaries on the seductive moving image such as Gorky's that offer a sufficiently-realized analysis of the simulacrum as hyperreal, one that would be supported by a host of other spectators throughout the cinema's early years. In the same year, 1896, a columnist for the New Review confirmed Gorky's assessment of the disturbing images of the cinema screen: “Here, then, is life; life it must be because a machine knows not how to invent; but it is life which you may only contemplate through a mechanical medium, life which eludes you in your daily pilgrimage. It is wondrous, even terrific. . . . It is all true, and it is all false” (qtd. in Harding and Popple 14). The reviewer's claim that the cinematograph reproduces merely an “illusion” of life emphasizes the basic operations of the cinematic apparatus and its reliance on “persistence of vision,” a widely-disseminated concept for explaining the reality that the human eye is incapable of seeing what the cinematic eye reveals (the reliance on human consciousness to fill in the gaps of perception between each frame of the cinema reel).Footnote 16 The camera's ability to produce the “unconscious optics” of the visible world, to use Walter Benjamin's well-known phrase, also had a powerful impact on spectators’ responses to cinematic bodies moving at the “unnatural” speed of 16 frames per second or less.Footnote 17 As Gorky suggests, the movement of bodies through the frame had a unique way of situating public life within an alien environment of grey city streets. One Lumière actualité of a carriage moving through a Parisian boulevard “teems with life and, upon approaching the edge of the screen, vanishes somewhere beyond it” (Gorky 5). Gorky's sense of discomfort emerges from his feeling of immobility – the images appear and disappear with a general disregard for the spectator's nerves. Moreover, Gorky writes, the Lumières’ image of Paris life occurs “in strange silence where no rumble of the wheels is heard, no sound of footsteps or of speech. Nothing. Not a single note of the intricate symphony that always accompanies the movements of people. Noiselessly, the ashen-grey foliage of the trees sways in the wind, and the grey silhouettes of the people, as though condemned to eternal silence and cruelly punished by being deprived of all the colours of life, glide noiselessly along the grey ground” (5). This incorporation of the supernatural reflects a fundamental anxiety in the 1890s that cinematic images were confined to a seduction (not a reproduction) of the real that would eventually expose the limitations of future cinematic development. “To seduce is to die as reality and reconstitute oneself as illusion” (69), Baudrillard writes, and this is certainly what Gorky came to understand during his experiences in the kingdom of shadows, namely that what actually defines the visible field of early cinematography is a thoroughly illusory and eerily undead approximation of reality. Analogously, the modern image reveals its latent vampiric core.

The emphasis in such reviews on the lifeless movements of bodies condemned to eternal silence gestures towards a decidedly gothic environment of deprivation in which the spectator would be a prisoner or captive, compelled to be seduced by the appearance of an undead life that shows all the requirements of an adequate representation of reality, but reveals those very indexical requirements as an excessive play of appearances and simulations. Here cinema recalls the image of the undead, the eternally lifeless living. More importantly, however, Gorky's response, like other early responses, ultimately condemns the future of the cinema, in much the same way that Louis Lumière would that same year, not only because of the cinematographic eye's production of an undead universe but also because of its debauched, sexually-charged exhibitions and its uncertain status as a scientific instrument.Footnote 18 Lumière's now-apocryphal claim that “the cinema is an invention without any future” reflects the uncertainties that many early filmmakers, scientists, and spectators felt about the cinema's popular appeal as a commodity.Footnote 19 Gorky's experiences took place, after all, at Charles Aumont's Theatre-concert Parisien, a Russian replica of a French cabaret in which men could see the latest wonders in visual technology while being entertained simultaneously by hundreds of chorus dancers. For Gorky, the cinematograph's moving images of the “clean toiling life” of Workers Leaving the Factory and An Arrival of the Train at the Station contrasted starkly with the debauched mise-en-scène of the concert theatre. The cinematograph's potential as a tool of science, he suggests, “is not to be found at Aumont's where vice alone is being encouraged and popularized” (6). Moreover, the vice popularized by the cinema theatres’ clientele would result, Gorky prophesizes, in other films “of a genre more suited to the tone of the concert Parisien” (6). This description of a coming spectacle of the seductive play of appearances of a debauched modernity reinforces Baudrillard's claim about the modern image's penchant for disrupting the illusory correspondence between the Real and the act of representation. What Gorky realizes in his review of the cinematograph is that its potential as a popular deployment of seemingly immoral images of nude and sexually-seductive bodies outweighs all claims to scientific value. At issue then for many early spectators and reviewers of the cinema was precisely this concern about the artifice of seduction emerging from the supposed realism of moving pictures. As Nead argues, the animation of photographic images in the 1890s resulted in a “brave new world of sexualised representation” (173) that produced two types of animated bodies: “first, the moving bodies seen through peepholes and on the screens of late Victorian visual culture; and second, the bodies of viewers as they experienced a particularly intense form of embodied, haptic spectatorship” (174).

This realization of the haptic intensity of moving images comes to fruition in Stoker's novel, particularly in its early chapters as Harker narrates his experiences while traveling in the East and Mina comments on the strange natural forces at work in London. Despite the novel's documentary style, which radically removes a singular authorial voice from the narrative of events, we should nevertheless pay attention to its latent self-critique of documentary realism as artifice. Harker's journey East, for example, while written in journal form and eventually transcribed by Mina's typewriter, contains numerous references to visual artifice and sensory tricks of perception, each registered through the body. Likewise, one of the more obvious references to the visual artifice of perception is Mina's observation that, upon Lucy's disappearance from her bed in Whitby, the view from her window reveals “a fleeting diorama of light and shade” (125) as ominous clouds pass by. Unbeknownst to Mina, Dracula's presence haunts her reference to the diorama, which was introduced by Daguerre in 1822 as a new embodied visual spectacle much like the panorama in earlier decades.

Even earlier in the novel, Jonathan's transition from an aesthetics of panoramic travel, in which the landscape unfolds around him to form a seemingly coherent experience of totality, to a subjective perception of falsehood and illusion becomes one of numerous exemplary proto-cinematic moments throughout the novel. Harker moves through space toward an inevitable confrontation with Dracula.Footnote 20 His perceptual confusion after being picked up by Dracula's carriage produces a series of tricks and illusions that heighten the novel's gothic effects, but they also enhance a full-scale assault on consciousness. “Once there appeared a strange optical effect,” Harker writes in his journal, “when [the Count] stood between me and the flame he did not obstruct it, for I could see its ghostly flicker all the same. This startled me, but as the effect was only momentary, I took it that my eyes deceived me straining through the darkness” (43). For Harker, this moment of trickery is the product of a shift in his experiences from the aesthetics of the outside to the delirious deprivation of the senses experienced on the inside:

What sort of place had I come to, and among what kind of people? What sort of grim adventure was it on which I had embarked? Was this a customary incident in the life of a solicitor's clerk sent out to explain the purchase of a London estate to a foreigner? . . . I began to rub my eyes and pinch myself to see if I were awake. It all seemed like a horrible nightmare to me, and I expected that I should suddenly awake, and find myself at home, with the dawn struggling in through my windows, as I had now and again felt in the morning after a day of overwork. (45–46)

The novel's early chapters consistently question personal encounters with the undead image. Harker's journal turns to an almost-scientific emphasis on recording accurate accounts of all he knows to be true. The eye of the observer of supernatural phenomena thus turns to a descriptive recording of Dracula's habits, customs, and rituals. As Harker writes, “I must find out all I can about Count Dracula, as it may help me to understand” (59). His intentions thus parallel the vampire hunters’ scientific methodology later on in the novel. Readers witness Van Helsing and Dr. Seward, for example, obsessively analyzing Mina's typewritten record of events, thus further reinforcing Harker's earlier reportage as the only way to counter the vampire's movements.

However, at this moment in Transylvania, Harker's stress upon the reproduction of accurate details demonstrates a heightened level of personal panic, resulting in his eventual bout of shock after his escape: “12 May. – Let me begin with facts – bare, meagre facts, verified by books and figures, and of which there can be no doubt. I must not confuse them with experiences which will have to rest on my own observation or my memory of them” (61). His journal asserts a breakdown in communication, a fundamental disconnection between the experience of vampiric movements (and illusions) and the facts of Dracula's existence. Seduction begins to take its place in Harker's experiences at Castle Dracula. His desperate attempt to hold onto facts and figures masks a deeper emerging problem: the seduction of the visible. The vampire's bodily movements are central to this seduction.

While Stoker's narrative of the increasingly illusory experience of the undead conforms to nineteenth-century anxieties about the deception of the senses after the advent of sophisticated visual technologies for the reproduction of reality, there nevertheless remains a sense throughout Harker's journal that to encounter the undead is not to experience a voyeuristic, and hence private, experience of the modern image, but rather a full-scale assault of the spectacular and the erotic. Such an argument contrasts much recent scholarship on the early cinema, which still retains psychoanalytic film criticism's emphasis on the voyeuristic elements of the viewing experience. Nead, for example, applies the critical lens of voyeurism and fetishization to her reading of the erotic displays of disrobing women in many early films.Footnote 21 Although informative in its account of the pleasures experienced by early cinemagoers, such an argument limits the discussion of seduction's manifestation in the film body, in favor of readings of the viewing experience that emphasize an unknowing object of the gaze in a private setting. The pleasure of looking in voyeurism does not sufficiently address the turning away, the destabilizing of the right or proper path, at work in the seduction process of the early film image's assault on the spectator's body. Dracula's early pages compel readers to notice an absence of the literary conventions of voyeurism. Dracula appears and disappears through a combination of pleasing and terrifying spectacles of light and dust, and his movements are like a spectacular display of seduction, the visible and the invisible interacting, condensing, and dancing kinetically, practically inviting Harker to confront them for all their horror and fascination. Harker's emphasis on dust dancing in the moonlight and the flicker of the vampiric image are certainly reminiscent of early spectators’ responses to the often-annoying presence of the cinematic apparatus during public exhibitions, but more importantly they invoke the mythology of the panicking, and hence primitive, spectator, that Gunning sees as central to the fin de siècle's culture of attractions. Referring to the common myth that early spectators responded with outright panic at the first display of the Lumières’ Arrival of the Train at the Station, Gunning argues against psychoanalytic-influenced film criticism and its limited understanding of the phenomenological experiences of the early cinema spectator. It was not the impending confrontation with the image of the train that startled the audience but rather the “force of the cinematic apparatus” itself (“Aesthetic” 114). The cinema apparatus hummed and clicked, and dust frequently found its way under the lens, producing an irritating flicker and a corresponding audience interested in the physiological sensations of the cinema experience, not the representational effect of a reality-image.

In Castle Dracula, the dust in the moonlight enhances this contemporary sense of a gothicized perception and atmosphere: the flicker of the image in both the cinema and the gothic space of Stoker's novel produces an assault on the nerves of the modern spectator/observer. Gorky's ultimate declaration about the experience of the cinema seems to second Harker's encounter with the undead. “This mute, grey life,” Gorky writes, “finally begins to disturb and depress you. It seems as though it carries a warning, fraught with a vague but sinister meaning that makes your heart grow faint. You are forgetting where you are. Strange imaginings invade your mind and your consciousness begins to wane and grow dim” (6). Part of the core anxiety about modern culture's reproduction of moving images was precisely this invasive assault on the body and its nervous system. The spectator's relative immobility produces a sense of isolation and submission to the image. As Mary Ann Doane writes, “the spectatorial body the cinema addresses and the body its representations inscribe is a body continually put at risk by modernity” (“Technology's Body” 536). Such is also the case for Harker when he encounters the seductive display of Dracula's three vampire women. Here, Harker's body meets the body of the cinema's primitive spectator, each assaulted by a modern spectacle of visibility. Even though Stoker's narrative consistently associates vampiric movements with an ancient occultism, Harker's captive immobility and visual delirium have all the markings of a modern spectatorial experience.Footnote 22 Like their Master, Dracula's three vampire brides (who represent an erotically-charged parallel to Lucy Westenra's whimsical regret that British society will not allow her to marry all three of her male suitors) move within the workings of a gothic apparatus of tricks of the moonlight and the interplay of light and dust. In similar fashion to Gorky's comments on the cinematograph's erotic potential to debase life, to reduce mechanical vision and its scientific potential to a debauched form of erotic display, Harker's descriptions of Dracula's women express anxiety about the seductive play of appearances of female bodies in motion. The vampire women, one of which Harker “seemed somehow to know . . . in connection with some dreamy fear,” momentarily lead him away from his obsession with the truth of Dracula's existence through an erotic fantasy of the simulacrum's sexual assault on the body of the male spectator. Waiting in an “agony of delightful anticipation” (69), Harker describes his first encounter with their undead sexuality through contemporary rhetoric of the modern attraction. The potential physical assault of the encounter, the desire to be punctured by the image of horrific “red lips” (69), destabilizes Harker through a delirious hypnotism. Dracula's interruption of this moment of seduction horrifies him, but his panic is not so much the result of a moving image of excessive monstrous femininity as it is about the disorienting form of the image of seductive bodies appearing and disappearing in an erotically-charged dance of undeath. Dracula satiates the vampire women's lust for blood by providing a “half-smothered child” (71) for their consumption, thus describing essentially a perversity of motherhood, but Harker's horror strangely deflects attention away from this moment of cannibalistic femininity toward the sheer audacity of the display of the vampire women's disappearance.Footnote 23 What matters, and what fundamentally unsettles the captive, is seduction – the removal of the object of desire from the order of the visible:

The women closed round, whilst I was aghast with horror: but as I looked they disappeared, and with them the dreadful bag. There was no door near them, and they could not have passed me without my noticing. They simply seemed to fade into the rays of moonlight and pass out through the window, for I could see outside the dim, shadowy forms for a moment before they entirely faded away. (71)

Only after this moment of disappearance does Harker fall into unconsciousness. The modern image of seduction proves to be too unbearable, and thus offers an almost explicit parallel to contemporary accounts of the cinematic image. Harker's initial encounter with Dracula's vampire women emphasizes the sudden disappearance of the female form, asserting a kind of rupture in the sober perception of the male spectator.Footnote 24 Like the Lumières’ train at the station, which assaults spectators through its full-frontal arrival and subsequent disappearance from the film frame, Dracula's vampire women demonstrate the kinetic, seductive uncertainty of the moving image.

A few diary entries later, and a month and a half after his initial encounter with the vampire women, Harker is forced to repeat this dance of undead seduction. After noticing for the second time “quaint little specks floating in the rays of the moonlight” (76), he contemplates initially their soothing effects. However, his sense of calm quickly morphs into panic as the “aerial gamboling” (76) transforms like a Méliès trick film into a potentially violent assault. In the proto-cinematic rhetoric of Dracula's castle, in Stoker's cinematography of the undead, the female form carries more palpable force than the Lumières’ A Train Arriving at the Station:

Something made me start up, a low, piteous howling of dogs somewhere far below in the valley, which was hidden from my sight. Louder it seemed to ring in my ears, and the floating motes of dusk to take new shapes to the sound as they danced in the moonlight. I felt myself struggling to awake to some call of my instincts; nay, my very soul was struggling, and my half-remembered sensibilities were striving to answer the call. I was becoming hypnotised! Quicker and quicker danced the dust, and the moonbeams seemed to quiver as they went by me into the mass of gloom beyond. More and more they gathered till they seemed to take dim phantom shapes. And then I started, broad awake and in full possession of my senses, and ran screaming from the place. The phantom shapes, which were becoming gradually materialized from the moonbeams, were those of the three ghostly women to whom I was doomed. I fled, and felt somewhat safer in my own room, where there was no moonlight and where the lamp was burning brightly. (76–77)

This passage marks the culmination point of the novel's early chapters concerning Harker's experiences at Castle Dracula. The emphasis here on vampiric movements evokes the epistemological frenzy of the modern spectacle. Later on in the novel, when Van Helsing brings the “committee” (275) of vampire hunters together in a formal deployment, the vampire's abilities to move through solid objects and dematerialize and rematerialize at any moment is forced to confront a modern science of disciplining and regulating bodily movements. Yet, at this point, the very explosion of visibility is more than just the literary realization of traditional gothic sensory deprivation: Dracula's vampire women may be the product of an immortal supernatural bloodstream, but their seductive dance of the undead remains distinctly modern, even at the expense of Harker's insistence that they are fundamentally a residue of an ancient, occult order.

The novel's rhetoric of the hypnotic dance of the feminine undead would have been quite familiar to Stoker's readers, given the popularity of the figure of the Vanishing Lady in London's theatres throughout the 1880s and 90s and the simultaneous popularity of Loie Fuller, Annabelle Moore, and their Serpentine Dances, which incorporated cinematic techniques into their choreography. The Vanishing Lady act, a popular magic performance in the period, instituted a form of representation of female bodies that produced an image of femininity entirely incorporated within modern culture's circulation of commodities. Various incarnations of the act, the culmination point being Méliès's short films of numerous vanishing women, emerged throughout the period of Stoker's writing of Dracula. Karen Beckman situates the many reincarnations of the act of feminine disappearance in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century popular culture within the context of a feminist criticism of visual spectacle and cultural mobility. The Vanishing Lady, in all of its media forms, emphasizes the reproducibility of the female form while also re-inscribing that reproducibility through a magical production of immobility. As Beckman writes, “the male magician makes this body vanish, and, though it often returns at the end of the trick, the female body seems to lie completely in the hands of the magician, or so the trick would have us believe” (47). Such spectacles of disappearance emphasized an effacement of feminine visibility, but more importantly, they also revealed a subtle trace of resistance in the body of the woman who refuses to remain in a state of disappearance. For the magic act to fully reveal its seductive pleasures, the woman must return within the technical parameters of modern spectacle.

Similarly, the distinctly modern choreography of Loie Fuller's Serpentine and Butterfly Dances in Paris in the early 1890s would offer up an image of feminine seduction in which the body of the female disappears within the technical craft of modern illusion and lighting. Fuller's particular contribution to modern dance stems from her deliberate designification of her own dancing body from the spectacle of movement. Incorporating long, flowing garments that hid the body from the spectator's view, Fuller took the spectacle of dance one step further by incorporating an almost-cinematic experience of light to illuminate her flowing garments (Figure 32). As Martin Battersby argues, Fuller “personified what Art nouveau artists felt about Woman as an abstraction – a vague, tantalising, ethereal vision” (164–65). More recently, Elizabeth Coffman has suggested that Fuller's particular “interpenetration” (73) of art and science offered a fundamental resistance to the physical culture movement of the second half of the nineteenth century that emphasized a modern management of bodily musculature through training and regimentation. In contrast to modern disciplinary regimes, Fuller's dancing limited the visibility of the body through a process of disappearance enhanced by the modern science of lighting and staging.

Figure 32. [Loie Fuller, full-length portrait, standing, facing front; raising her very long gown in shape of butterfly]. Photographic Print. c1902. Library of Congress.

In 1906, Fuller would produce her own cinematic images of dancing bodies, in which the female body would merge with the erotic display of the cinema screen to produce its own brand of disappearing woman.Footnote 25 This fusion of dance and the cinema was not necessarily coincidental or the product of Fuller's technological vision, however. For even as early as Edison's kinetoscope shorts, the dancing female form profited from popular interest in the spectacle of the attraction. Edison's Serpentine Dances, a series of shorts filmed in his early years before the advent of cinematic projection, featured the dancing of Annabelle Moore. Edison needed to convince potential purchasers that his machines would appeal to the public, so he borrowed from the inevitable appeal of the seductive bodies of modern dance. His short films of Moore's dancing, the frames of which were sometimes hand-painted in brilliant colors, demonstrate the extent to which the dancing body had been replaced by seductive patterns of light, color, and flowing garments (Figure 33). We might suggest, speculatively, that the Serpentine Dances serve as ideal illustrations of what Harker sees during his encounters with the vampire women in Castle Dracula.

Figure 33. Annabelle Serpentine Dance. Dir. Thomas Edison. Perf. Annabelle Whitford Moore. Edison, 1895. Kino Video.

These disparate bodies in motion – Dracula's vampire women, the Vanishing Woman act, Fuller's and Moore's serpentine dances – share a common seductive principle based on the haptic effect on spectators when the feminine form disappears and reappears from the frame or stage that grounds it in a substantial reality. More importantly, they also emerge both within and against the technical regime of bodily management and discipline at the turn of the century, influenced most noticeably by Marey's photographic studies of motion and bodily kinetics. Given Dracula's fascination with the spectacle of seduction, it is no coincidence that Stoker's vampire hunters also turn to techniques of discipline and control when they begin their counter-assault on the Vampire. When Van Helsing, “one of the most advanced scientists of his day” with an “absolutely open mind” (147) implores his student, Dr. Seward, to always remember that “knowledge is stronger than memory” (155), he basically recites the implicit rationale of Stoker's narrative mode of production. “I counsel you,” he warns Seward, “put down in record even your doubts and surmises. Hereafter it may be of interest to you to see how true you guess. We learn from failure, not from success!” (156). Everywhere in Dracula's collated collection of documents, diary and journal entries, phonograph recordings, telegrams, telephone conversations, travel logs, and newspaper clippings, an adherence to scientific method becomes the only supposed true path to defeating the Count's invasion of Metropolitan London and the seductive modern visuality that he and his vampire minions represent. The accumulation of documents that comprises the novel (transcribed and reproduced in triplicate by Mina's typewriter) exhibits a graphic impulse toward managing, limiting, and disciplining Dracula's movements throughout London. Dracula's mobility requires that his vampire hunters become the representatives of a modern bureaucratic agency (paradoxically armed with crucifixes, holy water, and garlic) in what Foucault has called the nineteenth century's “political economy” of the body.Footnote 26 This organization is equally reliant upon modernity's speed of transportation and communications transmission. The novel's railways, urban transport, and journeys back and forth from the Continent produce bodies that seem to move at speeds faster than the transmission of information. These bodies – of the vampire hunters and other modern citizens of the age of speed – become part of an economy of modern mobility that transforms mid-nineteenth-century anxieties about the speed of railway travel into a necessary force in the battle against Dracula's supernatural crimes against modernity.Footnote 27 As Foucault observes, modern disciplinary regimes instituted a shift in thought not only about deviance and the criminal body but also the institutional mechanisms through which “life” is produced as an experience of discipline, regulation, and control. At the core of this production of life, the body (of the criminal, the bureaucrat, the vampire) emerges as merely a by-product of a “microphysics of power” that “invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to carry out signs” (12, 25). Van Helsing's assertion that knowledge emerges from a scientific method of experimentation is essentially a foundational modern formula, in Foucault's sense, of the production of knowledge through power relations. That this production of the “facts” of Dracula's movements also parallels the movements of the vampire hunters becomes a necessary consequence of modern mobility.

In this sense, Stoker's novel contains political allegiances (albeit with some significant differences) to Marey's “graphical method” of data accumulation put forward throughout his work in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. A contributor to the rise of the cinema and a major influence on both Edison and the Lumières, Marey is most known for his lifelong fascination with the mechanics of life: the circulation of blood, the flight path of birds, the human body's movements.Footnote 28 Throughout his research from the 1870s, after the publication of Animal Mechanism (1873), to his later experimentations with chronophotography in the 1880s and 90s, Marey concluded that the two factors that impeded scientific development – the fallibility of the senses and the insufficiency of language for expressing knowledge of the natural world – required that scientists construct elaborate instruments for measuring the graphic traces left by nature's “universal language” (qtd. in Hankins and Silverman 9) of nature. Marey's scientific pursuit of the graphic reproduction of Time in his serial photographic studies of movement was persistently frustrated by the body's penchant for exceeding the confines of pure representation. Marey's interest in the “natural language of the phenomena themselves” (qtd. in Rabinbach 95) resulted in graphic traces of movement that could produce a sufficient reproduction of bodily mechanics, but they produced a visibility of the body that did not sufficiently enhance the limited capacities of the human eye. Even Marey's scientific tinkering with different recording devices, methods, and approaches to the reproduction of movement through time could not situate the body's movements within a graphic reproduction of what Bergson referred to, in the same period, as pure duration. Time also slipped between the cracks, between each individual temporal unit, producing photographic images in which the human body becomes increasingly abstract and even at times seems to disappear completely from the photographic frame (Figure 34). To quote Charney again, Marey, and his contemporary Muybridge, became “the artist[s] of emptiness” because they discovered, without knowing it, “a form for the re-presentation of vacant space, for the hollow futility of the project of representation” (Empty Moments 41).

Figure 34. Étienne-Jules Marey. Course de l'homme. Chronophotograph. c1890. Courtesy of La Cinémathèque Française.

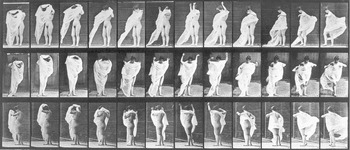

The inevitable failure of representation was not as serious a concern for Muybridge as it was for Marey. Muybridge's instantaneous photographs of nude men and women in Animal Locomotion (1887), and other collections, were more the product of a popular curiosity than a mechanistic recomposition of bodily movements. Muybridge's work produced thousands of sequences depicting bodies performing everyday movements (walking, running, jumping, turning, throwing, sitting), often without any scientific pretense at all.Footnote 29 Muybridge presented his photographic sequences to public audiences during a series of lecture tours through Europe and North America in the 1880s and 90s that cemented his fame as one of the early pioneers of the cinematic reproduction of motion. Through the exhibition of his zoopraxiscope, a rudimentary proto-cinematic apparatus that could project approximately 200 photographs in sequence, producing a rudimentary image of motion, Muybridge dazzled his audiences with the charm of a showman. His photographic sequences of nude women are particularly suggestive of the erotic possibilities of motion that worried Gorky in his review of the cinematographic. As Linda Williams argues, Muybridges's serial photographs often exceed the parameters of a purely scientific study. His use of props, for example, staged movements within the confines of gendered acts and activities: while Muybridge's nude men often perform athletic or physical movements with the use of dumbbells, boulders, baseballs, swords, and various tools, the props associated with feminine movements are “never just devices to elicit movement,” but rather they “are always something more, investing the woman's body with an iconographic, or even diegetic, surplus of meaning” (514). Moreover, Muybridge's sequences contain titles that explicitly evoke an erotic code (One Woman Disrobing Another; Getting Out of Bed) through a subtle play of expectations regarding the visibility of bodily activities. Even the most private moments are scrutinized under the pretense of scientific inquiry (Figures 35 and 36). Muybridge's “new kind of erotic display” (Christie 71) emphasized an explosion of the visible that would haunt Marey's more-scientific refusal of evidence gained from the senses and his corresponding graphic recompositions of movement that spoke in their own language, the mechanical language of locomotion.

Figure 35. Eadweard Muybridge, “Plate 73. Movements, Female, Turning Around in Surprise and Running Away” from Animal Locomotion (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1887). University of Pennsylvania Archives.

Figure 36. Eadweard Muybridge, “Plate 416. Movements, Female, Toilet; Putting on dress” from Animal Locomotion (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1887). University of Pennsylvania Archives.

These differences between the two forerunners in the field of serial photography demonstrate a persistent concern with the problem of representing and reproducing bodily movements. The reproduction of movement is a timely analog for the crisis of perception that plagues Stoker's novel and its scientific methodology of control. The novel's entire existence is premised on the assumption that the latest gadgetry of nineteenth-century information culture can trace, manage, and eliminate the vampire from London. Yet as Kittler suggests, the written word “merely stores the facts of its authorization” (Gramophone 6); that is, the graphic reproduction of experience that the novel's narrative relies on for its disciplinary management of Dracula's movements through London merely produces the vampire body as a type of movement divorced from a reproduction of the real. The vampire hunters’ scientific methodology regarding the movement of bodies attempts a de-supernaturalizing of the vampire, so to speak, as the crew of vampire hunters use their knowledge of Dracula's powers to limit his movements to the light of day, effectively attempting to inscribe the undead body within modern biopower.Footnote 30 The goal for Van Helsing and his crew, fundamentally, is to compel the Vampire to become a disciplined body, one that can be controlled, manipulated, and confined to a reduced and thus quantifiable range of motion. Van Helsing's knowledge of the occult, which allows the vampire hunters to engage with the supernatural powers of the undead, functions equally as well as their scientific method in this disciplinary intervention. The occult powers of crucifixes, holy water, and garlic supplement the limited capabilities of the materialist method of accumulation and accurate interpretation of details in an almost seamless fusion of the scientific and the occult.Footnote 31 Van Helsing's open mind regarding occult forces thus performs the same disciplinary work as science: either way, Dracula's body will be investigated, interrogated, and compelled to leave traces or clues of its movements. As a result, the vampire virtually disappears from Mina's typewritten collection, leaving only a graphic trace in its place, thus reducing Dracula to a trail of bureaucratic evidence. Dracula becomes a seductive figure, neither fully present nor fully absent in the novel's pages.

As a result of this disappearance from the text, the vampire still remains a seductive, threatening figure, despite modern biopower and its attempted management of vampiric “life.” Even so, this technical effacement of the vampire-image from their collection of documents reveals a core anxiety about the illusory phenomena of the supernatural. While their materialist faith in the accurate recording and storage of details compels Stoker's vampire hunters to reject evidence gained through the senses, undead simulacra still penetrate the narrative's core. Harker's experiences in Castle Dracula result in a surplus of visibility that defies even the most rudimentary narrative recollection. The novel's typewritten collection of documents thus cannot fully store the assault of images that characterizes the undead. The novel's early chapters emphasize this epistemological clash between supernatural images that defy the rational, bureaucratic faith in the “facts” and the graphic disciplinarity of later chapters.

My concluding remarks here are thus two-fold: on one hand, there is an analogy between the vampire hunter's graphical method of tracking Dracula's movements and the scientific pretensions of Marey's and Muybridge's serial photography. Both counter the seduction of modern motion-images with intense desire to make the body reveal all of its incipient movements, to make all images of motion conform to known laws. Essentially, the seduction of images must be reduced to incremental units of time. On the other hand, the seduction of the visible in Dracula and the serial photography of the period always reveals the impossibility of true representation of the moving form. The effect of such an impossibility is the revelation of erotic images. Certainly, Dracula is eventually eliminated as a threat to the English nation, but not fundamentally as a result of scientific method. The novel opens up a space for seductive images of bodies in motion to haunt any and all representational genres, techniques, and forms.

Like Marey's research into the body's movements, in which the body practically disappears from his graphic reproductions, leaving in its place an obsessive science of graphic traces, flows, lines of movement, in a deliberate attempt to limit the body's seduction of the senses, Dracula and his vampire women are also compelled to undergo a rigorous science of elimination. Read alongside the cinematography of both Marey and Muybridge, Stoker's novel becomes something not completely cinematic in the usual sense of the term, but rather cinematic in its debt to the science of images and temporality in the period. Dracula is a kind of failed representational machine, like the Lumière cinematograph, and more importantly its failure is all the more alluring because of its seductive play of vampire images that confound the graphic trace of the vampire hunters’ pursuit. Anson Rabinbach suggests that Marey's later graphic reproductions produced an “extraordinary economy of representation – the reduction of the body to a ‘geometric’ pattern of lines in space along a line of time” (108). Moreover, for Marey photographic reproductions of bodily movements were too seductive, in both Baudrillard's sense and literally, in that they led the objective, scientific eye astray while enticing the fancy of the scientific mind with the potential exchange value of representations of real life. In the late-1880s, Marey's assistant, George Demeny, would go against his employer's concerns about the coming invasion of the cinematic undead. He would became seduced by the fantasy of a photographic realism that was quite common for early cinema idealists:

How many people would be happy if they could for a moment see again the living features of someone who had passed away! The future will replace the still photograph, locked in its frame, with the moving portrait, which can be given life at the turn of a wheel! The expression of the physiognomy will be preserved as voice is by the phonograph. The latter could even be added to the phonoscope to complete the illusion. . . . We shall do more than analyze [the face]; we shall bring it to life again” (qtd. in Dagognet 162).

For Demeny, and indeed for many early enthusiasts of the cinematic image, the future of photographic realism would result in no less than the reanimation of the dead and the realization of eternal life for the living. “Embalming the dead,” Andre Bazin suggests, is the goal of all aesthetic modes of expression, but here the dead would no longer remain in the still form of the corpse (in this sense, the photographic frame would be its coffin) but rather would survive in the vitality and dynamic force of the film reel.Footnote 32 The dead would be sought after not only by scientists but also by loved ones and the general public.

The motion studies of Muybridge and Marey would eventually become part of the larger project of the early cinema, but even at this early point in the cinema's origins, the visibility of the natural order was already under threat by a seductive play of appearances and surfaces. Their serial photography would increasingly realize this problem with the seductive image of bodily movements (and particularly the female body in motion). Despite attempts to reduce motion to a visible and quantifiable register of distinct units of time, scientists realized, much to their chagrin, that the body resisted all attempts to reduce its explosion of appearances to a visual field of total control and production. An analogous situation occurs in Stoker's novel, where the vampire narrative must resort to a relatively conventional imperial adventure story. Dracula is certainly eliminated, but not by scientific means. Despite its larger claims to the contrary, the novel's reliance on scientific method fails as a disciplinary method for controlling the erotic spectacles of vampiric bodily movements. At best, the vampire hunters seem satisfied with their adventure, despite the fact that their scientific progress resulted in “nothing but a mass of typewriting” (419). Life goes on; seduction thwarts science, forcing it to rely on brute manly force (guns and wooden stakes) to contain evil.

Louis Lumière's declaration about the cinema's pointless future was issued as a direct response to such manifestations of the modern image that consistently refused to contribute to control, discipline, and management. By the turn of the nineteenth century, newspapers in Britain and the United States had begun to assess the most important technological discoveries of the century and their relevance in the coming years. As Christie has shown, only five years after its “official” birth, the cinema had indeed become a mode of representation lacking a future, as fin-de-siècle assessments of the future seemed almost oblivious to the “living picture craze” that had swept Europe and North America a few years earlier.Footnote 33 Prior to the cinematograph, Marey's refusal to pursue his research in the projection of moving images thus spoke to an emerging realization that the cinema's modernization of the senses was perhaps lacking in the social, scientific, and aesthetic progress it was supposed to embody. It thus seems that sometime immediately after its emergence – and indeed even earlier – the cinema's very modernity had become strangely passé and mundane. Yet, for all that, it did nevertheless open up a space for the play of the animated undead, those eerie phantoms of the Lumière cinematograph, to haunt modern representational practices. Today, we know that the cinema's moving images have become part and parcel of our own brand of culture industry, and it seems fitting to us that the vampire-image has played a part (even if not exactly a central one) in our encounters with the undead, the cinema's eternal images of a “life” that outlasts us, and indeed conditions our own experiences of living in the world.