There is no Past, so long as Books shall live!

A disinterr'd Pompeii wakes again . . .

Edward Bulwer-Lytton, “The Souls of Books” (1893)I. The Last Days in its Cultural Contexts

Ever since the discovery in 1749 of the remains of Pompeii, destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, the excavations have yielded rich materials for understanding the daily life of the Roman Empire. They also featured as themes in contemporary European design, art, and music, including opera. In the nineteenth century, previously diverse elements were unified into a romantic mythic narrative, fixed in material form, disseminated, consolidated, imported to Pompeii, naturalised, and then re-exported. This process is evident in the publication history of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel, The Last Days of Pompei (1834). Taking in the spin-offs and feedbacks of theatre, songs, opera, pantomime, the circus, high and popular art, and book illustrations, we use quantified information about readerships and viewerships from archival and other primary sources to show how, within the economic and technological governing structures of the Victorian age, cultural consumers cooperated with producers to invent myths and clichés still vigorous today.

The Last Days of Pompeii begins with a scene of wealthy Pompeians sauntering through the streets of Pompeii where they encounter Nydia, a blind slave girl selling flowers. This casual meeting between her and the rich Greek Glaucus introduces the storyline. Nydia, who soon loves Glaucus across the insuperable social divide, is purchased by him and presented as a gift to the beautiful and virtuous Greek heiress, Ione, who is the ward of Arbaces, an Egyptian priest of the religion of Isis. A plot by Arbaces to gain her (and her money) is thwarted by Nydia, but when Ione's brother discovers the plot, Arbaces murders him and sets up Glaucus to take the blame. However when Glaucus is made to fight a lion in the gladiatorial arena, the ferocious beast turns away, much to the disappointment of the baying crowds, and insists on returning to its cage. Suddenly the volcano erupts and buildings shake and fall to the ground as the city is torn open by earthquakes. Arbaces, who tries to persuade the people that the volcano portends the vengeance of his gods against his enemies, is killed by a falling imperial statue. In the darkness and confusion of the last day only the blind Nydia can find her way through the rubble-strewn streets, and she leads Glaucus and Ione to the port. On the voyage to Athens, however, Nydia throws herself into the sea, suicide being allowed by ancient ethics. Her heroic sacrifice earns her a marble shrine, but also relieves the narrator of having to invent a later life. Her death makes way for the socially matched, newly converted, Christian couple to live together happily ever after.

When Bulwer wrote and published The Last Days of Pompeii, he was inserting himself into a tradition some of whose themes went back to the ancient Jews, Greeks, and Romans, others to the European Renaissance, and some that were more recent. He was able to draw on and adapt a wealth of cultural production relating to Pompeii and its destruction as offered to different types of cultural consumers in a variety of media across Europe. And in some cases it can be shown from the biographical record that he had direct knowledge of his predecessors, both ancient and recent. Among recent predecessors were paintings, volcanic spectacles, literature and travel writing, and opera, yet none of these, either individually or together, came close to being as influential as his novel was to become.

The main focus of this essay is on the materialities of the production and diffusion of the ideas in the Last Days, asking questions such as how did the text come to be written in the form that it was, who had access to the book, when, in what numbers, in which versions, and with what consequences? The essay also explores the materiality of the adaptations and spin-offs – theatre, songs, opera, pantomime, the circus, high and popular art, and book illustrations – that both influenced the text of the novel by being anticipated, and then helped to shape readerly and viewerly responses and interpretations. In exploring how Bulwer and other agents were able both to exploit the tradition and to carry it forward in new ways to immense new readerships and viewerships within the technical-economic as well as the cultural constraints and opportunities of the Victorian age, we are fortunate in being able to draw on a body of scholarly books and articles, including some very recent, in which some of the cultural contexts have been explored, mainly within the conventions of criticism of the works as texts.Footnote 1

It may be useful first to offer a brief summary of some of Bulwer's immediate predecessors who helped to set cultural contexts into which The Last Days of Pompeii was to prove so decisive an intervention. Most, including theatrical productions, were visual. As Nicholas Daly notes in “The Volcanic Disaster Narrative,” in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, erupting volcanoes provided a popular subject for artists, with Vesuvius increasingly dominating (262–63). Among the paintings were Jacques Volaire's The Eruption of Vesuvius (1771) and The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius (1777), Jacob More's Mount Vesuvius in Eruption: The Last Days of Pompeii (1780), J. M. W. Turner's Vesuvius in Eruption (1817), and John Martin's The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822). Many readers in England could be confidently expected to know this painting by Martin, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1822, more widely circulated as a mezzotint (indeed painted with mezzotint in mindFootnote 2), and turned into a diorama at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in 1822 (Daly 263). Almost all initial readers would have recognised Bulwer's Arbaces as much the same as the Arbaces of Byron's play Sardanapalus (1821), and some may have seen engravings of Delacroix's apocalyptic painting, The Death of Sardanapalus (1827).

Adrian Staehli observes that Bulwer's immediate inspiration for writing the novel was Karl Briullov's painting, The Last Day of Pompeii (1833), that he saw in Milan (“Katastrophenszenarien” 3). In contrast to most previous paintings of Vesuvius, Briullov focused on the Pompeians and the “panopticon of human despair and fear of death,” rather than the power of nature (Staehli 7, trans. ours). In all these ways, Bulwer's The Last Days of Pompeii, although a work of literature that at first did not include illustrations, thus both drew on and helped to disseminate the artistic conventions of the apocalyptic sublime in which human beings are shown as tiny, terrified, and helpless victims of overwhelming forces of nature or of the vengeful wrath of the Judaeo-Christian god as told in biblical stories such as Noah's flood or the description of the end of the world in the Book of Revelation.

Bulwer also drew on traditions from plays. By the 1800s volcano spectacles could regularly be seen in the London theatres (Daly 260–61), and Mary Beard notes that re-enactments were put on in Pompeii itself throughout the nineteenth century (“Taste and the Antique”). Bulwer's narrative includes a visit to a witch in a cave taken from a play, “The Witch of the Volcano,” which had enjoyed a long run in London in the early 1830s, so bringing in a stock scene of the old woman and her curse and providing an occasion for another old favourite, a switch of love potions.Footnote 3 Gladiators too were already established on stage.Footnote 4 In the Last Days, Bulwer's descriptions of Pompeian life before the eruption emphasise the brutality, corruption, luxury, and immorality of the Roman rulers. Slaves are treated casually and cruelly, with topical allusions to the debates about the “property rights” of slave owners (bk. 1, ch. 3), while the effeminate and pampered lords go from banquet to banquet, and from one trivial entertainment to another.Footnote 5 The Roman men spend much time in unmanly washing – some bathing as often as seven times a day – and fall into an ‘enervate and speechless lassitude . . . dreading the fatigue of conversation’ (bk. 1, ch. 7). The women are vain (Figure 1). Occasional passages hint at unspeakable orgies (Figure 2).

Figure 1. After Franz Kirchbach, “Dressing Room of a Pompeian Beauty.” Engraved illustration from Edward Bulwer Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii (London and New York: Routledge, c1900). Private collection.

Figure 2. J. J. Waddington, after E. F. Sherie, “‘Drink, feast, love, my pupil!’ said he; ‘blush not that thou art passionate and young.’” Etching. The Last Days of Pompeii (London: G. J. Howell, c 1900). Private collection.

The assertion that the Romans of the Empire were morally decadent compared with their Republican ancestors went back to writings of the Romans themselves. There are similarities in the Last Days to descriptions of luxury in Petronius's Satyrica, written in the late first century (Harrison 84–88). And the novel reinforces wider contemporary themes in the Victorians’ emerging view of themselves as an intellectual and artistic people. That it was a country's literature and art that made it great, Bulwer himself was to promote in the preface to his historical work Athens: Its Rise and Fall (1837), in which he declared that it was the literature of Athens “more than the arms or the institutions of Athens, which have rendered her illustrious” (vii). As Simon Goldhill remarks, the Last Days joined attempts “to keep Greece as pure as possible, by denigrating Rome” (196). When Glaucus and Ione are in Athens, they see how hollow Roman civilization is compared with Greek. Like Victorian travellers to Athens and visitors to the Elgin Room at the British Museum, they “behold the hand of Pheidias and the soul of Pericles” (Chapter the Last).

The Last Days was admiringly dedicated to archaeologist Sir William Gell, the greatest expert on Pompeii, whose grand and lavishly illustrated Pompeiana (second ed., 1832) was the source of much of the scholarly apparatus in the footnotes. In the final words, reprising the preface, the narrator of the Last Days repeats that, since he wrote the work on the spot, he can claim archaeological accuracy in spite of being “from that remote and barbarian Isle [Britain] which the imperial Roman shivered when he named” (Chapter the Last). These claims to authenticity were renewed in a second preface in 1850 in which he calls in as further witnesses “the profound scholarship of German criticism.”

Inserting Christians

In one large respect, however, for all its learned scholarly apparatus, the Last Days was unfair to the archaeological record. Although no unequivocal evidence had been found to suggest that there were Christians in Pompeii, nor indeed has any been found subsequently, the Last Days is given a strong Christian thread. Glaucus's father, readers are told, had played host to Paul when he gave his famous speech on the Areopagus in Athens recorded by the author of the Acts of the Apostles. However, young Glaucus, in a serious misremembering of what his father had told him about what Paul said, attributes his own rescue to “the hand of the unknown God!” Nydia and the lion were instruments of a divinely guided destiny that saved him from the general destruction. But the Last Days also cautioned its readers against copying the early Christians. Glaucus is tolerant: “I shudder not at the creed of others” (Chapter the Last). His “lukewarmness” he claims as a virtue. The Christianity of Glaucus is that of a nineteenth-century Anglican.

In the end, however, the Last Days is less about nineteenth-century English bourgeois Christianity than about providentialism, a more ancient, enduring, and resilient idea. The destruction of Pompeii, according to the Last Days, was the working out of the plans of divine Providence, another idea that Bulwer did not invent but picked up and ran with. Many said that Pompeii was “fated.” A few years earlier, for example, an opera, L'ultimo giorno di Pompeii, had played in London which included the line “oh Pompeii, thy last day is registered in heaven.”Footnote 6 Similarly, Lincoln Fairfield's long narrative poem of 1832, The Last Night of Pompeii, combines the volcano with a Christian moral schema. As Nicholas Daly notes, several plot elements of Bulwer's Last Days are reminiscent of Fairfield's poem: a virgin is about to be raped by a priest of Isis but is rescued by the eruption, the hero is almost devoured by the lion in the arena but the eruption causes it to kneel instead, Pompeii is destroyed but the Christians escape and found a new Christian community (268).

A few years before Bulwer was writing the Last Days, William Rae Wilson, a fierce Christian with a deep antipathy to Roman Catholicism, had visited the site of Sodom and Gomorrah, which he saw as “strikingly monumental of the tremendous wrath of God,” and confirmatory of the truth of the Bible (168). At Pompeii, he was delighted to see a similar scene of destruction: “how beneficial, too, even in its temporal effects, has been that Divine and Heaven-revealed Religion, to which, among its other blessings, we are indebted for the extirpation of enormities that make us shudder” (Records 228). However, before the Last Days, the idea that the Pompeians had brought their destruction on themselves was not wide-spread.Footnote 7 In Bulwer's novel, Pompeii was unequivocally added to the list of cities, including Sodom, Gomorrah, Babylon, Tyre, and Nineveh that the Judaeo-Christian god had righteously punished.Footnote 8 The Pompeians had it coming (Figure 3).

Figure 3. After Franz Kirchbach, “The Hour is Come!” Engraved illustration from The Last Days of Pompeii (London and New York: Routledge, c1900). Private collection.

The Historical Novel

So were there any new ingredients? The preface acknowledged the author's debt to Walter Scott and the immensely popular Waverley novels, and to the theory of historical romance that both Scott and Bulwer theorised as well as practised.Footnote 9 Putting fictional characters into real historical situations, they argued, offered a more truthful view of the past than either fiction or history. Romance was universal. Bulwer made an explicit claim that he was filling a gap – the paucity of romances that had survived from the ancient world.

The novel skilfully employs linguistic and framing devices that allow the narrator to move the story, and its lessons, through time. The characters speak in an invented archaic diction (“howbeit,” “didst thou,” “darksome,” “Nazarene”) that disguises that they are English men and women of 1834, starting a tradition that still flourishes in sword and sandals epics. Assertions of racial continuity (“a population that still preserve a strong family likeness to their classic forefathers”Footnote 10) bridge the time gaps – the people of Pompeii are explicitly presented as just like the people known to readers,Footnote 11 and their social position and their characters can be read from their costumes and faces. Occasionally the narrator points directly to the read-across, warning that the British had better look out. The London boxing ring is a modern example of effeminacy as well as brutality, as dangerous to masculinity as the fashionable vapour baths:

So we have seen at this day the beardless flutterers of the saloons of London thronging round the heroes of the Fives Courts . . . male prostitutes who sell their strength as women their beauty; beasts in act, but baser than beasts in motive, for the last, at least do not mangle themselves for money. (bk. 2, ch. 3)

A boastful passage in that preface in which Bulwer claimed to have succeeded “where all hitherto have failed” was later quietly dropped.Footnote 12 But in one of the author's main aims, the claim was a valid one. The Last Days did put individuals into the ruins and thereby reanimated them. A modern visitor to Athens could imagine walking where Pericles had walked. In Rome too the ruins were populated by memories of the famous dead. But before the Last Days, Pompeii had been mainly art and archaeology, with only Pliny providing some human interest. Some visitors, for example John Moore in 1781 and Chateaubriand in 1827, advocated the reconstruction of Pompeii to aid the imagination.Footnote 13 Ruins were, according to ancient wisdom, standing reminders of the transitoriness of human pretensions. Ruins instantiated a philosophy of history, made famous across Europe by The Ruins by Count Volney, his meditations on the ruins of empires, first published in 1788. As Volney declared in the preface: “I will dwell in solitude amidst the ruins of cities: I will inquire of the monuments of antiquity what was the wisdom of former ages.”Footnote 14 However Pompeii did not moulder under ancient briars or creeping ivy like ancient ruins in the vicinity.Footnote 15 On the contrary, it looked new.Footnote 16 Nor were there local people with folk traditions. The reverend John Chedwode Eustace's A Classical Tour through Italy An. MDCCCII, the standard travel guide in use before the Last Days, spoke of visitors to Pompeii feeling like intruders, imagining that they might suddenly meet the master of the house into which they were trespassing. The general impression was of silence, solitude, and repose (vol. 3, 69).Footnote 17 Until the Last Days, Pompeii was a “City of the Dead.”Footnote 18

Bulwer's novel was the product of its cultural context. What was new, and what was to capture the imagination and admiration of millions of Victorians, was using this material as backdrop to an array of individual characters in a romance that unfolds in time, that is, Bulwer's skill as a novelist. Like Scott, Bulwer combined pre-existing material into a story with a moral purpose. As he had pointed out in England and the English: “Facts, like stones, are nothing in themselves; their value consists in the manner they are put together, and the purpose to which they are applied” (1: 126).

II. The Material Book

When Bulwer draftedThe Last Days of Pompeii, he was already a famous and financially successful author. He understood the political economy of cultural production of his day, and was leader of a political campaign for copyright to be extended to dramatic writing. The Last Days of Pompeii can help us to retrieve Victorian attitudes to Pompeii. However, without an understanding of the governing structures of consumption as well as of production that enabled the novel to be brought into being in the material form that it was, we risk prolonging the romantic fallacy of the author as “creator,” or of treating the printed literary text as an emanation of the zeitgeist.

For a new work of fiction to be published in the British market of 1834, the almost unshakeable convention required the book to be initially published in three volumes. The commercial circulating libraries, the main initial customers, could then have each of the volumes hired out to different subscribers in succession to be read serially over a number of weeks within families that had ample leisure. The printed text of the Last Days is not much more than 150,000 words, a length that could be comfortably fitted into one volume, and even that figure was the result of an artificial lengthening insisted upon by the publisher (Gettman 235). This episode, which only a few insiders could have known about, resulted in an insider joke in the passage about the baths:

The number of these smegmata [lotions] used by the wealthy would fill a modern volume – especially if the volume were printed by a fashionable publisher; Amoracinum, Megalium, Nardum – omne quod exit in um. (bk. 1, ch. 7; schoolboy Latin for “everything that ends in um”)

Already before it was published the Last Days was inviting readers to be knowingly co-opted into a shared fiction. Did any reader from the highest income groups of England ever seriously think that the Romans took seven baths a day between meals?

Bulwer's name did not appear anywhere in the book. The novel was presented as “By the Author of ‘Pelham,’ ‘Eugene Aram,’ ‘England and the English’ &c. &c. In Three Volumes.” By this device, potential buyers and readers were alerted to what to expect. Pelham, especially, the novel on which Bulwer had made his name, was an exploration of the emerging construct, the “English gentleman” with a classical education. The Last Days of Pompeii presented itself as a book written by a real gentleman for real gentlemen and their ladies, guaranteed before it was even ordered to contain nothing to bring a blush to an Ionian cheek.

As Bulwer and his first publisher Bentley knew, the commercial success of any newly published novel depended upon the orders from the circulating libraries. The more that is excavated from the archives of Victorian authors and publishers, the more determinative the role of the buyers of the circulating libraries turns out to have been. If the buyers decided not to take the risk for whatever reason, a novel had no future. And their judgment was much influenced by what they thought might be the reactions of the guardians of public morals, a self-selecting group who used their social position or ecclesiastical office to patrol the textual limits of what was suitable for an English Ione to read. In practice complaints were few, but the whole production system of fiction writing, agents, authors, internal editors, publishers, designers, and others was aimed at forestalling potential objections from these “imagined interventionists.”Footnote 19

Publication of The Last Days of Pompeii was not free of risk, however. There were many among the rich and leisured users of circulating libraries who might have seen references to their ennuyé selves, to use a favourite word of the day, and Bulwer may have exaggerated and ironised the excesses of the ancient Romans in order to forestall that reaction. Indeed a providentialist might be inclined to say that the last minute printing delays were part of a grand scheme to promote the book and its Christian message. On 27 August 1834, after a few years of rumblings, minor earthquakes, and intermittent eruptions, Vesuvius erupted again as was reported in the British press, giving the book an immediate topicality such as publishers dream of.

The Last Days of Pompeii appeared on the market in late September 1834. On 13 October, Lady Blessington was able to tell Bulwer:

[I]t is in everybody's hands. Hookham [owner of the fashionable circulating library in London] told me that “he knows of no work that has been so much called for” (I quote his words) and the other circulating libraries give the same report. The classical scholars have pronounced their opinion that the book is too scholarly to be popular with the common herd of readers – but the common herd, determined not to deserve this opinion, declare themselves its passionate admirers, so that it is read and praised by all classes alike. (Lytton, Life 1: 443)

The use of “common herd” by the doyenne of the “silver fork” school needs to be contextualized. The retail price of the Last Days, thirty-one shillings and six pence before binding was equivalent to about three week's wages of a clerical worker. A subscription to a circulating library was also expensive – Mudie's charged one guinea a year – and membership never widened beyond the aristocratic and professional classes.Footnote 20 Compared with the size of the reading nation, the numbers of copies produced was tiny. During its first sixteen years as a material book, the total number sold in Britain did not exceed six or seven thousand.

Most of the reviews were highly favourable, praising the work's “great power, originality, beauty,” “finely contrasted characters,” and “animated dialogues,” regarding it as “one of the most admirable works of fiction in the English language,” with “vigour and freshness of genius” and so on.Footnote 21 Bulwer was commended in the Examiner for having revivified the ruins: “In Glaucus, he has brought to life the owner of that fairy mansion which is termed the House of the Tragic poet. This is a striking part of the reality of the novel” (23 October 1834). However, one remark in the Morning Post that the Last Days had greatly exaggerated the scale of some of the buildings appears to have stung Bulwer personally (13 November 1834), perhaps because it undermined his claim to be the successor to Scott, who was always scrupulous in his historical detail.Footnote 22 In an “Advertisement to the Second Edition,” that was included in the 1839 edition but never reprinted, Bulwer claimed poetic licence, but also an expectation that he would be vindicated by future excavations.Footnote 23 For all his learned footnotes Bulwer had been convicted of being unfair both to his model Scott and to the archaeology. The Last Days had mythologized a provincial town into a great city comparable with Rome itself.

The production history of the Last Days in Britain can be summarized in the following table (Table 1), drawn from incomplete archives.

Table 1. Production History of the Last Days in Britain

a Our estimate is taken from the discussion by Gettman (see note 17) of the evidence of the Bentley Archives at the University of Illinois and compared with other archives, including other contracts made by Bulwer-Lytton that are in the British Library. Shortly after the book was first published in the United States, a story circulated that 10,000 copies had been sold in London on the first day of publication (“Fictitious Writing,” Atkinson's Casket [April 1837], p. 186) and that story has entered the secondary literature; see Meilee D. Bridges, “Objects of Affection: Necromantic Pathos in Bulwer-Lytton's City of the Dead,” in Hales and Paul 2011, pp. 90–104. However, the claim is not only disproved by the archival record but is at variance with what is known about fiction publication at the time.

b Bentley Records, British Library, add 46,674 (December 1838: first impression 4,042, October 1839; reprinted 1,000).

c Frank Arthur Mumby, The House of Routledge 1834–1934 (London, 1936), including a transcript of the contract, p. 57.

d Routledge archives, microfilm reel 4, p. 381. We have not yet been able fully to understand the complex entry but Routledge estimated for fifty editions, or rather impressions, of 10,000 each. Only a few copies have survived.

e Routledge archives, microfilm reel 5, p. 711.

f Estimate taken from the discussion on Penny Poets and Penny Novels in Sir Frederick Whyte's Life of W. T. Stead (London, 1925), 2:228–31.

Although incomplete, the record matches the general pattern of Victorian fiction, namely a small very expensive initial edition aimed at, and self censored for, the richest one or two percentiles of society, followed by a move down the demand curve during the period of copyright as each tranche of the market is taken and readerships widen, to be followed by a flood of extremely cheap sixpenny paper covered editions (as well as continuing more expensive editions) the moment the text came out of copyright. These patterns can be directly related to the technical-economic governing structures, limitations, and opportunities unique to that age, including especially the technology of stereotype plates and the intellectual property regime.

III. Readership and Influence

In terms of literary history seen as a parade of authors and first publications, the Last Days is a work of 1834. In terms of readership and influence, by contrast, its glory days are the late-Victorian and pre-1914 generation. The Last Days made its way into the guides to the best books intended for readers and librarians that flourished in late Victorian times, including A. H. D. Acland's A Guide to the Choice of Books for Students and General Readers (London: Stanford, 1891) and E. B. Sargant and Bernhard Winshaw's A Guide Book to Books (London: Frowde, 1891). And it made the cut in Sir John Lubbock's famous and much reprinted Hundred Best Books (1896), where it joined the Bible, Homer, Aeschylus, Plato, Shakespeare, Goethe's Faust, the Koran, the Maha Bharata, and other books of literature, history, exploration, and science in his attempt at a world canon.

The progressivist literary paternalism that the novel embodied was however soon to be defeated by the critique of modernism and the experience of the First World War. Soon the Last Days was being presented as a book for young people. In the post war years it became common to sneer at the book and the Victorian attitudes it appeared to represent, although many households had on their shelves copies which continued to be read.Footnote 31 In these respects Bulwer follows the trajectory of the rise and fall of Scott and the respect given to his works as moral teachers almost exactly.Footnote 32

Immediately on its publication in 1834, the Last Days changed ways of looking at Pompeii. As Isaac Disraeli, father of Benjamin, who had recently been there, wrote: “you have done more than all the erudite delvers have done” (14 November 1834, Lytton, Life 1: 443). Another friend, John Auldjo, wrote on 26 July 1836:

Will it not gratify you to know that people begin to ask for Ione's house, and that there are disputes about which was Julia's room in Diomed's villa? Pompeii was truly a city of the dead; there were no fancied spirits hovering o'er its remains, but now you have made poetical its very air, you have created a new feeling in its visitors . . . . (Lytton, Life 1: 445)

William Gell had been wary of the successful young novelist, whose talk had been of the economics of publishing, but when his copy arrived in Naples he was delighted:

I own I consider the Tragic Poets house since I read the novel, as that of Glaucus & have peopled the other places with Bulwers inhabitants in my own mind which is a proof that his Tale is judiciously applied to the locality. (Sir William Gell 154)

The archaeologist had not quite surrendered science to myth but he had made an accommodation with a sorcerer casting magic spells.Footnote 33 In 1834, too, in the absence of international copyright, publishers outside Britain could legally reprint, translate, or adapt as they chose. It was from one of these “piracies” that Auldjo arranged a translation into Italian in Milan, from which an even cheaper version, sold in parts, was produced in Naples. By 1836 the Last Days was being read in Italian in Pompeii (Lytton, Life 1: 445).

The colonizing myths and fictions soon established themselves as permanent settlers on the site. Throughout the nineteenth century and later, local guides, showing visitors round the remains of the amphitheatre, told elaborated stories of the lions that refused to fight the “Nazarenes” and of Pompeii destroyed as God's punishment for its wickedness.Footnote 34 Since pre-Last Days travellers make no reference to these stories, it seems certain the myths were imported, locally naturalized, and then re-exported. Mary Shelley had visited Pompeii in 1818 with Shelley, whose interest had been primarily archaeological and artistic; she too noted the change that Bulwer's romance had brought about when she made a second visit in 1843. As she wrote in her published journal:

A greater extent of the city has been dug out and laid open since I was there before, so that it has now much more the appearance of a town of the dead . . . Bulwer, too, has peopled its silence. I have been reading his book, and I have felt on visiting the place much more as if really it had been once full of stirring life, now that he has attributed names and possessors to its houses, passengers to its streets. Such is the power of the imagination. It can not only give “a local habitation and a name” to the airy creations of the fancy and the abstract ideas of the mind, but it can put a soul into stones, and hang the vivid interest of our passions and our hopes upon objects otherwise vacant of name or sympathy. (Rambles 2: 279)Footnote 35

As far as the United States was concerned, in 1834 American publishers were also free of legal copyright restrictions. However, the New York publisher Harper Brothers reprinted the book in two volumes almost as soon as it was published in London (Seville 63). The exact circumstances are not fully known, but we know that Harpers paid for an advance set of proofs, so giving the firm a valuable lead over other publishers.Footnote 36 Harpers also had another advantage, being one of the first companies who exploited the recently perfected technology of stereotype plates which meant that they could keep a title in print as long as there was demand, reducing marginal cost and therefore price.

The widespread adoption of stereotyping enabled publishers across the English-speaking world to share manufacturing plant. And soon they did so for illustrations as well as texts. The Last Days was one of the first novels to benefit from this transformation of publishing into a globalised business, with many American editions being identical with the English apart from their title pages.Footnote 37 Its huge success was due not just to its appeal, but also to a precise conjuncture of technical-economic factors.

IV. The Last Days Live on Stage

The text of the novel is author-led, and no readers apart from the initial anticipated “imagined interventionists” participate in any feedback loop. Readers may pick and choose, make their own interpretations, and read against the grain, but until the work came out of copyright, they could not alter what had been textually decided in the summer of 1834. Very different from this form of production was that of the parallel medium that coexisted with the novel from the beginning, adaptation on the live stage. Within three months of its publication as a novel, The Last Days of Pompeii could be seen on the London and New York stage, continuing for exceptionally long runs.Footnote 38

That adaptations for the stage would certainly happen, willy nilly, had evidently been fully anticipated by Bulwer. Although, at his own urging, dramatic copyright had recently been introduced, it did not yet prevent adaptations into other media appearing under the name of another “author.”Footnote 39 Adaptation with or without the approval or involvement of the novel's author or publisher was normal with any novel that had some success. Indeed, the Last Days, with its detailed descriptions of costumes and localities and short chapters, appears to have been deliberately drafted with transfer to performance media in mind. Reviewers at the time noticed the novel's “peculiar aptitude for scenic representation which every page presents” (rev. in the Morning Post, 16 December 1834). The Last Days also included many songs and ballads that not only helped to bulk up the text but could, and did, take on a life of their own, another feature in which Bulwer followed the successful example of the Waverley novels. In those respects too, the Last Days was socially produced within the technical-economic, including intellectual property, structures operating in 1834.

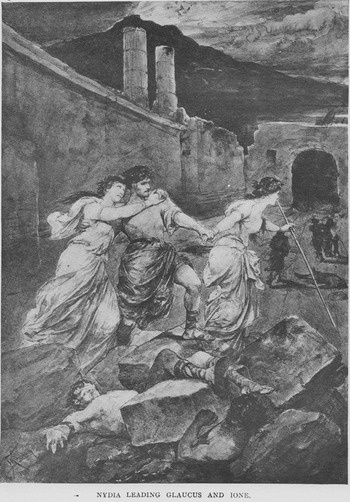

Stage versions appeared throughout the nineteenth century, notably John Oxenford's five-act drama The Last Days of Pompeii at the Queen's, that made a feature of Nydia's throwing herself into the sea (Figure 4). But most performances were not plays in the modern sense. Until 1843, only Covent Garden, Drury Lane, and in the summer, the Haymarket, were “Theatres Royal” with the exclusive right to produce “spoken drama.” All others were so-called “illegitimate” or “minor” theatres without this license. The way that theatres like the Pavilion, or the Garrick, where versions of the Last Days were performed, got around this restriction was to intersperse dialogue with song and dance numbers, and with spectacle, to create burletta, the only legitimate generic form they could stage.

Figure 4. Nydia throwing herself into the sea. Engraved illustration from Oxenford's The Last Days of Pompeii. Illustrated London News, 27 Jan. 1872. Private collection.

Compared with the readerships of the novel, large though they eventually became, the theatre audiences were enormous. A growing number of theatres in the early nineteenth century had capacities of several thousand: Covent Garden and Drury Lane held some 2,500 and 3,600 people respectively (Worrall 227, and Flanders 295), the Coburg (which became the Victoria in 1833) nearly 4,000 (Flanders 330), even travelling shows at fairgrounds could at times accommodate about 1,000 people in very large tents (Worall 227), and several semi-permanent circus buildings could hold as many as 3,000 people (Russell 373). Capacities tended to increase throughout the century. By the 1870s, the Britannia was able to pack in 3,923, Astley's 3,780, the Pavilion 3,500, Drury Lane 3,800 (Donohue, “The Theatre” 255). And the range of prices was wide, as can be seen from the playbills. However, even the most expensive was much lower than the price of the book. The Adelphi, illegitimate but more fashionable, charged 1s for the gallery, 2s for the pit and 4s for a box. Prices for the patent theatres in 1834 ranged between 1s for the Upper Gallery and 7s for the Stalls.Footnote 40 The Pavilion, a house mainly frequented by a working-class audience, charged admission prices for the Last Days of between 6d and 1s6d (Figure 5). The Pavilion refers to Scott almost as part of the title: just as Bulwer associates himself with Scott, theatre managers, too, use Scott's name to evoke connotations of high quality as well as immensely popular historical stories.

Figure 5. Pavilion Theatre's Playbill for The Last Days of Pompeii, or the City of the Dead! As Designated by the Immortal Sir Walter Scott. 1835. Victoria and Albert Museum, Theatre and Performance Archives.

Most of the spectators at the East End playhouses came from the immediate neighbourhood: journeymen, mechanics, shopkeepers, clerks, sailors, and women and children.Footnote 41 However, new bridges as well as improved transport made the East End houses more easily accessible to more affluent audiences from elsewhere in London. In the early 1820s, Queen Caroline herself famously visited Astley's, the Surrey and the Coburg.Footnote 42 The Adelphi, where Buckstone's highly successful version of the Last Days ran for 64 nights in the 1834–35 season, was one of London's most popular theatres, with “peers and apprentices, dukes and dustmen” among its audience (Moody 39).

Information about the capacities of the various venues is sketchy, partly because managers tended to think in net revenues from a range of prices, rather than numbers of viewers as such. The runs varied, and of course not every performance was sold out, and the length of the run is not always documented. However an indication of the comparative viewerships that can be compared with the indications of comparative readerships in Table 1 is offered at Table 2.

Table 2. Theatrical Adaptations and Spectacles

Even a conservative total estimate indicates of a minimum of 50,000 to 100,000 viewers for the 1834–35 season. This can be compared to the 1000 initial copies of the printed book, perhaps leading to a readership of 5,000 to 10,000. Furthermore, the estimates for the Adelphi, the Pavilion, and the Garrick, are based on capacity records from the 1850s, but the houses would have been larger than in the 1830s. Even taking this into account, the data suggests a minimum of 50,000 to 100,000 initial viewers. When the Adelphi or the Pavilion put it on, more people saw a version of the story in a single night than read it in a year. And many of these viewers did not have access to the book. Far more people learned about the destruction of Pompeii from seeing the adaptations than ever did from reading the book.

V. What the Consumer Wanted

With a printed book, because it is a durable capital asset that can be passed from hand to hand and read limitless times, the political economy structures, when supported by the monopoly of copyright, encourage the producers to start at the top of the demand curve and move down as slowly as possible. This structure encourages texts aimed at economic elites, artificially high prices, access spreading slowly over time, and feedback anticipated not actual. With theatrical performance, by contrast, because the fiction is simultaneously consumed as it is produced, and empty seats cannot be carried forward, the structures of political economy encouraged arrangements aimed at satisfying the whole market simultaneously, by for example, building ever larger theatres, advertising heavily, and differentiating and discounting prices across a wide range. The novel is top down, producer led, the theatre is bottom up, consumer led, and there is a large overlap between the individuals who participate at the higher price levels.

These structures of the theatre also bring about instantaneous feedback, immediate knowledge of what works on the night and an ability to change the product as a result. And we can see how soon the unstable stage versions diverged from the version fixed in print. Much of what was thought to please the “imagined interventionists” of the circulating libraries was stripped out. There is almost nothing of what Angus Easson calls the Biedermeier “harmless Christianity” and “uxorious domesticity” that modern readers find so cloying in the novel (113). Indeed there is almost no Christianity, discussion of religion being discouraged by the censors, but this lack is also an example of the risks of equating Victorian mentalities with the ideologies of the printed text of the Victorian novel.

The playbills give further indications of what the producers thought the consumers wanted. The three lines printed in the biggest font on the Pavilion Theatre's playbill for The Last Days of Pompeii are “Shock of an earthquake!” “Arena and Amphitheatre,” and “Eruption of Vesuvius!!” The Garrick Theatre's bill emphasises “A flash house in Pompeii!!” “Colossal head of Isis,” “Effects of an Earthquake,” “Abode of the Witch!!” “Fight of the Gladiators,” “Eruption of Vesuvius,” and “Destruction of the City of Pompeii!” The bills designate the plays as spectacles, while at the same time telling a moral story of Roman decadence and depravity duly punished by the destruction of the city.

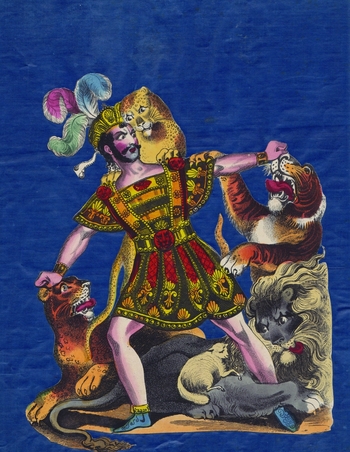

The reluctant lion was a firm favourite, sometimes played with live lions and other dangerous animals – and often for laughs. The story was a gift to lion tamers, providing them with a familiar storyline, with costumes, into which to insert their performance. The Brute Tamer of Pompeii, first performed as early as 1838, became a popular feature in the huge Astley's theatre and arena. The famous American animal performer and circus owner, Isaac van Amburgh, also performed the role, and seems usually to have worn Roman costume. Two popular prints, one from London, the other from the United States, show the Roman costume and the Pompeian stage setting (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. The Brute Tamer of Pompeii; or, the living lions of the jungle. Performed at Astley's Royal Amphitheatre, London, Aug 1838. Narrativized play: Tales of the Drama. London: E. Lloyd. Hamilton College, New York. Courtesy of Christian Goodwillie.

Figure 7. Juvenile drama, portrait of the American-animal trainer Isaac van Amburgh, as the Brute-Tamer of Pompeii. c 1838. Cut out, hand colored, and mounted on blue linen. Private collection.

Reviews of the plays at the end of 1834 focus on spectacle and scenery, as well as comment on the play's popularity, which will, The Satirist suspects, “benefit the treasury more than any other piece of the season” (rev. of Adelphi's 21 December performance). Journals admire “the whole general array and splendour and fitting up of the stage, with the triumphant catastrophe at the close” (Examiner rev. of same). Reviewers comment on the Amphitheatre and gladiators, as well as the “vivid and grand exhibition” of the eruption (Morning Chronicle rev. of the Victoria's 27 December performance), which “conveyed to the spectator a good idea of the terrors of that awful natural phenomenon” (Bell's Life rev. of the Adephi's 21 December performance). Of the characters, the blind, selfless, and pure Nydia, who in Buckstone's version makes her appearances only to sing and to rescue others, is by far the most discussed. Played at the Adelphi by Mrs Keeley, Nydia receives “unqualified approbation [and] admiration” from reviewers (Morning Post rev. of the Adephi's 16 December performance). They admire “the truth and pathos” of the representation of Nydia as well as her songs (The Satirist). Other characters are barely mentioned, nor is the plot explained or discussed.

Another highly popular version was Robert Reece's burlesque The Very Last Days of Pompeii, staged in 1872 at the Vaudeville, a house with a capacity of 1,000. Tickets could be had from 6d in the Gallery to 7s in the Stalls, and the play ran for at least 250 nights.Footnote 45 The play was reprinted cheaply for amateur and school performance all over Britain. It is full of topical and self reflexive jokes, and favourite hate figures like the witch, at whom the audience might be expected to hiss, but these jokes only work if most of the audience is familiar with a straight version.

Enter the Lion, [. . .] he is a large but mild-looking animal— he sits down, and washes his face like a cat.

Arbaces: Call that a Lion!

Sallust: The brute, how I could lash ye!

Apæcides: I've seen a better made of papier maché.

In addition to the novel and the theatre, the myths of Pompeii were constructed, selected, disseminated, and reinforced in the form of pictures. And again this was not a derivative or ancillary medium but a parallel stream of cultural production and consumption that both took from and fed into the others. The numerous nineteenth-century paintings that share themes with the Last Days have been covered elsewhereFootnote 46 and only a few points need be added in this essay. What is striking, as with many British Victorian paintings, is the extent to which viewers are expected to know the story, probably assumed to be the version in the novel. Some of these paintings themselves became as well known as the story. James Pain's 1880s huge outdoor spectacle version, for example, with a spectatorship of 10,000 per performance in London in the summer months of 1888 (Mayer 90), expected audiences to be familiar both with the plot and with famous paintings. It had had a similarly successful run in America (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The Last Days of Pompeii performed at Manhattan Beach. Pyrodrama by James Pain. From Harper's Weekly, 1885. British Library by permission.

“Nydia” carried a host of associations, not all derived from the Last Days, just by being named. The statue by Randolph Rogers, named as Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii (1853–54) gave some help in its title and may have invited comparison with Hiram Powers's naked Slave Girl, who has a Christian image on her leg. These works of “high” art were often purchased to be displayed in provincial galleries as part of an agenda with educational aims. The painting of Nydia by Cuno Baron von Bodenhausen, that was used as an illustration in books, was reproduced around 1890 in the form of a beautifully coloured porcelain plaque that could be hung on a wall as part of a series that included similar plaques of the Virgin Mary and other female Christian saints.Footnote 47 Anonymised Nydia became actual not just metaphorical Biedermeier.

But the pictures that were most often seen were illustrations in books. They reached far more viewers over longer time-scales than the paintings or prints. The period when the Last Days was most read, or at any rate most sold as a book, the second half of the nineteenth century, coincides exactly with a golden age of artistic illustrations. And again this phenomenon, from which the Last Days benefited immensely, is only fully understandable when put within the material technical-economic opportunities and conjunctures of its time. For just as the word text of the Last Days as a novel to be read was able to ride on the huge technological productivity improvements in the manufacturing of printed books that occurred during Victorian times, so too it rode on a parallel productivity revolution in the manufacture of visual images that occurred over the same period and that took the story to widening and eventually immense viewerships. Just as the Last Days cannot be adequately understood if it is regarded solely as an autonomous work of literature, without taking account of the two-way feedbacks with theatre, so too the illustrations both helped to determine how the novel was read and interpreted, and they responded to what the producers anticipated that readers would welcome. Although many editions were printed without illustrations, for innumerable others the travelling personal art gallery that accompanied the words was an intrinsic part of the paratext of the books, that both helped to pre-set the expectations of readers before they began to read and influenced their subsequent responses.

Before the Last Days, illustrations in novels were rare. The main medium, engraving on copper, was laborious and costly to manufacture. Most copper plates produced a maximum of 750 -1,000 impressions before they became worn, and even with re-engraving and refurbishment, new plates had to be manufactured after about 1,500. In the 1830s, however, with the perfection of the technology of engraving on steel or on coating copper plates with steel, the number of impressions that could be taken was almost unlimited. We see both a sudden huge increase in the quantities of visual images and the beginning of a long run reduction in the price of access. By the mid 1830s the ladies’ annuals were producing so many illustrations engraved on steel in impressions of 5,000 and more that T. H. Fielding, a contemporary author of technical manuals, thought that the public were “weary of seeing in every shop and on every table the beautiful engravings which steel plates had showered upon the land” (30). The earliest, and for a long period the only, two illustrations of the Last Days were steel engravings. The frontispiece to Bentley's 1839 edition offers a scene of domesticity little different from that of a contemporary English drawing room (Figure 9), and the vignette picks out the episode of the reluctant lion (Figure 10). With the ending of the Bentley series, these images ceased to be reproduced, though the Christian-friendly lion appeared in many subsequent editions to the extent that there is scarcely an illustrated book that does not show that episode.

Figure 9. W. Greatbatch after a painting by W. Wright, “Turning, he beheld Nydia kneeling before him, holding up to him a handful of flowers.” Engraved frontispiece from The Last Days of Pompeii (London: Bentley 1839). Private collection.

Figure 10. W. Greatbatch after a painting by W. Wright, “The beast evinced no sign either of wrath or hunger; its tail drooped along the sand instead of lashing its gaunt sides; and its eye, though it wandered at times to Glaucus, rolled again listlessly from him.” Title page vignette from The Last Days of Pompeii (London: Bentley 1839). Private collection.

The second early illustration, also an immediate expectation-setting frontispiece, first appeared in the 1850 edition and was composed by Hablot K. Browne, famous as illustrator to Dickens. Strongly neo-classical, it took expectations in another direction, to Greece. This illustration, like Bulwer's word, humanises the archaeological artefacts shown in Gell's Pompeiana. It is a vision of the elegance of ancient Hellas – Pompeii as Elgin Marbles (Figure 11). This image, that appears from its innumerable thin and tiny lines to be an etching on steel, benefitted from, or was perhaps designed for, another contemporary productivity improvement that was even more revolutionary in its impact than steel engraving, the invention of electrotyping. This technology enabled accurate copies of the metal plates to be made without limit. As Fielding notes, the duplicates were “perfect . . . the faintest lines and even blemish in the polish of the original plate is preserved” (94–96). The plates from which this illustration was made were duplicated and shared between publishing houses, even across the Atlantic, just as publishers also shared stereotype plates for the word text. Innumerable impressions were made from the plates or electrotype copies in London, first by Chapman and Hall and then by Routledge over decades. In the United States it continued to be included in the American Lippincott edition of 1867, and the Collier edition of 1896, and perhaps later.

Figure 11. After Hablot K. Browne. Engraved frontispiece from The Last Days of Pompeii (London: Chapman and Hall, 1850). Private collection.

The advent of photography enabled the Last Days to be illustrated with photographs of the ruins of Vesuvius and of items in the museums, but in general the medium matched the message. Photography, a cold modern technology, was reserved for archaeology – a science that demanded accuracy. For interpretation, publishers and readers preferred artistic invention which was then reproduced by photographic processes such as photogravure, which reproduced some of the textures of painting, into metal plates or wood blocks from which multiple copies could be taken. Photogravure meant that illustrations, notably those by Franz Kirchbach, could be imported from Germany where the technology was at its most advanced. Until the very end of the century no image copying technology could economically use colour in mainstream books.

Among the artists who illustrated the Last Days in its various nineteenth- and early twentieth-century English-language editions were Cuno Baron von Bodenhausen, Hablot K. Browne, Kurt Craemer, Gene Christman, Bertha Cuson Day, A. A. Dixon, Edmund H. Garrett, Joseph M. Gleeson, Frederick Gilbert, Franz Kirchbach, J. M., George Morrow, Miss M. Phillips, E. F. Sherie, Lancelot Speed, C. H. White, W. Wright, F. C. Yohn, and anonymous. As with all book illustrations, other agents were often at least as determinative of the nature of the images that were produced, in particular those who commissioned them, as well as the engravers, lithographers, and others concerned with the reproduction processes. The illustrations to the translations into French, German, and Italian, mainly done by local artists in their national styles, offer many of the same episodes as the British and American editions: the luxury, the witch, the lion, the catastrophe (Figure 12), and the death of Nydia.

Figure 12. After Franz Kirchbach, “Nydia leading Glaucus and Ione,” Engraved illustration from The Last Days of Pompeii (London and New York: Routledge, c1900). Private collection.

The illustrations should not be dismissed or disregarded as mere optional extras prepared by others to decorate the authored literary work. On the contrary, once we disengage ourselves from romantic notions of autonomous immaterial literary texts, we can explore how illustrations in books had their own rhetorical tendencies and effects. Roland Barthes, in his writings on the rhetorics of cinema whose essence is movement, noted the central importance of the still photographs used, for example in advertising or in displays outside the cinema, in throwing off the constraint of time and making what he called a third meaning.Footnote 48 We suggest that the illustrations performed the same role for novels that also follow a logical-temporal order, appearing to demand to be read from the beginning to the end. Indeed it is striking how rapidly once the technical-economic constraints eased, the choice of episodes to be illustrated in the Last Days settled into a consistent pattern. It would be an exaggeration to say that a Victorian man, woman, or child glancing through an illustrated edition would learn the whole story, but like the audiences for burlesques, they could quickly pick up and follow the gist.

Soon the illustrations in the books merged with the conventions of the paintings. As a first-time reader of the Last Days in 1926 wrote:

Everyone knows them. The artist has clumped together a few girls in tunics, a fountain, a dove, a Nubian slave, a leopard skin, and a marble column and called the resultant hotchpotch “The Glory that was Rome.”Footnote 49

The subject of Sir Edward John Poynter's painting Faithful unto Death (1865) was taken up and repeated later by the book illustrator Lancelot Speed, whose etching appeared in editions by more than one publisher in the 1890s.Footnote 50 Speed's version (Figure 13) took its caption from the words of the novel. Faithful unto Death has usually been taken to illustrate selfless devotion to duty, maybe even Christian sacrifice.Footnote 51 However Speed's version, seen by many more people than Poynter's, is more true both to the spirit and the text in the Last Days which reads: “He remained erect and motionless at his post. That hour had not animated the machine of the ruthless majesty of Rome into the reasoning and self-acting man. There he stood, amidst the crashing elements; he had not received the permission to desert his station.” In the background to Speed's version can be seen women and children in danger and distress, but, as Bulwer had explained, in a modern phrase, Roman society has not yet socially evolved enough to make him go and help them.

Figure 13. After Lancelot Speed, “Amidst the crashing elements: he had not received the permission to desert his station.” Engraved illustration from The Last Days of Pompeii (London: Nisbet, c 1900). Private collection.

If the soldier is “faithful,” he is displaying the traditional military virtue of obedience, as celebrated in Tennyson's “Charge of The Light Brigade” (1854): “Theirs not to reason why.” He is like Casabianca, who, in Mrs. Hemans's poem of that name (1826), a Victorian favourite, “stood on the burning deck/Whence all but he had fled.” But if the soldier is as incapable as a machine of thinking for himself, that only shows yet again that the Roman Empire did not deserve its imperial responsibility. Both versions are reassuring for Victorian readers and viewers. The Roman sentry is another of the many examples of Bulwer reminding the reader that his novel is based on archaeological observation. The footnote to the text of the novel reads: “The skeletons of more than one sentry were found at their posts.”Footnote 52 As Simon Goldhill notes, Bulwer identified “each of his characters’ skeletons in the contemporary excavation” and had two skulls from Pompeii in his home: those of Arbaces and Calenus (201).

For viewers and readers outside the high bourgeoisie, a different Last Days was presented. When the copyrights expired the innovative publisher John Dicks commissioned a set of images for his sixpenny edition. They are highly dramatic, almost as if they were taken from stage versions, with violence and horror, but also a respect for ordinary Pompeians (Figure 14). The contradictions between the religious traditions were brought out starkly, if inadvertently, in an illustration in a French edition of the Last Days by the Armenian artist Charles Atamian, reproduced as Figure 15. The stones and burning lava from Vesuvius spill into the text in a bold trompe l'oeil, encouraging readers who are immersed in the story to see themselves as trying in vain to flee the destruction. The passage from the novel is however from the later scene when Glaucus and Ione wake up on their boat and find that order has been restored. In the English version: “They looked at each other and smiled – they took heart – they felt once more that there was a world around and a God above them.” Even in the original English, readers may have thought that, when all their family, friends, and neighbours had died a horrible death the day before, such sentiments were scarcely a satisfactory closure. In the French translation, the disjunction is exacerbated by a small change to the wording and the juxtaposition of image and text. As the French text reads, translated into English: “the world was still standing and was directed by a powerful and merciful God” (emphasis added, Figure 15). No wonder many Victorians were inclined to say “if this is Christianity, I prefer the pagans.”

Figure 14. After Frederick Gilbert, “Athenian, resist me, and thy blood be on thine own head.” Engraved title page from The Last Days of Pompeii (London: Dicks, 1883). Courtesy of the British Library. A number of the Gilbert illustrations were also used in editions published by Ward & Lock.

Figure 15. After Charles Atamian, “The volcanic mountain, dazzling with a sinister splendour, was no more than a column of fire burning the earth and the heavens.” Illustration from Les Derniers Jours de Pompéi, Adaptation inédite, ornée de 40 aquarelles de Ch. Atamian (Paris: Linsson, early 20th century). Private collection.

The 1890s represent the high-water mark for the Last Days, when finally it reached mass readerships in addition to the mass viewerships it had long since achieved in some cities. By then it had been joined by a spate of what were known at the time as “toga novels” and “toga plays,” notably Ben Hur and Quo Vadis, but also others since forgotten, such as The Sign of the Cross or The Barbarian Ingomar which adopted the conventions of decadent Romans, virtuous Christians, and lions in the arena and were disseminated by the same range of media.Footnote 53

Throughout the century, the Last Days acted as a guidebook to Pompeii visitors, aiding their imagination as they contemplated the ruins.Footnote 54 Indeed by the turn of the nineteenth century, the art historians and archaeologists were becoming impatient at the extent to which the myths of the Last Days were overwhelming their attempts to understand the site. For example, the authors of Pompeii, Painted by Alberto Pisa, Described by W. M. Mackenzie, one of the first books to provide colour images, remark despairingly about the archaeological remains of the kitchens in the “house of Pansa”: “One wonders whence Bulwer-Lytton conjured up the gorgeous feasts that strew the pages of The Last Days of Pompeii” (47).

The “they had it coming” theme that rode on an archaeology that was almost as mythical, continued to exercise its power, as was made explicit by an American Christian bishop who visited with his family in 1895, calling it

this ruined city which was overwhelmed by the wrath of God in a single night: its polluted streets and houses, which even now indicate depths of depravity that have seldom been witnessed in the history of the world, ruined and utterly destroyed as habitations for the living. Surely the moralist will be excused for drawing his lesson from the destruction of this comparatively modern Sodom and Gomorrah. (Clark and Clark 572)Footnote 55

This tradition as it stood at around 1900 slipped easily across into the new technology of radio, film, television, and other media where it has continued to thrive, renewed every few years for a new generation. The conventions and clichés that Hollywood adopted from the Last Days, and its theatrical and visual companions, are still as they were formalised in 1834 and earlier, including the archaic speech, the brutality, the beasts, the banquets, the baths, the lace-up sandals, the insertion of imaginary Christians, the misreading – and misrepresentation – of the scale and implications of the ruins, the portentous attempts to awe young people and adults into Anglo-American middle-class conformity, and the burlesques which undermined them.

For the modern visitor to the streets of Pompeii, Nydia no longer sells her flowers, Arbaces no longer spins his dark oriental spells, nor does Ione smile sweetly. But for the tens of millions elsewhere who are dependent on contemporary popular cultural production, only the names have changed. Even today it is necessary for any factual presentation of discoveries at Pompeii to begin by disowning the myths of the movies.Footnote 56 In the continuing competition between scientific archaeology and moralising myths, The Last Days of Pompeii has not been defeated.Footnote 57