In the penultimate volume of his panoramic Tableau de Paris (1781–88) Louis-Sébastien Mercier observed that

Neighbour and rival, London inevitably provides the pendant to the portrait I have painted – the comparison suggests itself. The two capitals are so close and so different, yet bear such a resemblance to one another that, to complete this work on Paris, I must tear my eyes away from its imitator [Émule].Footnote 1

One day, he swore by Newton and Shakespeare he would make it to London and provide this missing pendant. In fact, Mercier had already paid London a visit some time in 1780–81 and penned a lengthy manuscript entitled ‘Paris comparé a Londres’, now preserved in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal – and subsequently published by Bruneteau and Cottret in 1982 – as Parallèle de Paris et Londres. This fascinating work is arguably the most rigorous and enjoyable comparison of the two capitals ever undertaken, comparing not only public works such as hospitals, churches, prisons and bridges, but also social customs and rituals – even horses and colds, things one might otherwise assume to be the same in both cities.

Mercier's Parallèle is a fascinating resource for urban historians. This article will focus on just one of his comparisons, however: that between pleasure gardens in London and in Paris.Footnote 2 Pleasure gardens were privately operated suburban entertainment resorts which combined tree-lined allées for promenading with ornate, often temporary structures in which to drink, dance, eat, view paintings and watch short dramatic or acrobatic performances. Pleasure gardens usually opened only in summer, on nights when the weather was fine. Entry cost relatively little, a shilling or 12 sous in many cases; less than a day's wage for an artisan. Alongside the understandable attraction of escaping the humid confines of the city, much of the gardens' alfresco appeal lay in the unscripted entertainment afforded by the crowd itself: admission fees were low enough to admit members of both the noble elite as well as the middle class. In a society defined by rank, pleasure gardens were exciting, if occasionally unsettling, places to be.

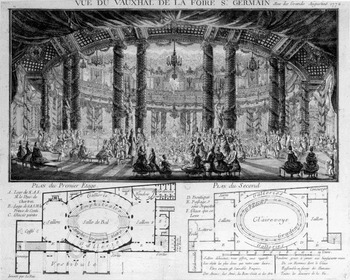

The most famous pleasure garden was London's Vauxhall, established south of the Thames in 1661, on an 11-acre site currently bordered by Kennington Lane to the south, and the railway line into Waterloo to the west. It featured long allées lit by lanterns, a raised orchestra, supperboxes and a small rotunda to which a series of history paintings were added by 1760, celebrating recent victories over the French. Vauxhall survived for almost another century, spawning many rival gardens in London and elsewhere in Britain and Ireland.Footnote 3 It also had its imitators on the continent. In France, indeed, pleasure gardens were commonly called ‘les Wauxhalls’ – and for simplicity's sake that is how they are referred to here. In the years between 1764 and the Revolution at least ten opened in Paris; others opened in Strasbourg, Bordeaux, Marseilles and Lille.Footnote 4 They originated as additions to established suburban summer fairs, such as that of Saint Germain, where the Italian Jean-Baptiste Torré opened his ‘Vauxhall’ in 1764 (Figure 1).Footnote 5 In the early 1770s, however, they came into their own, and even became the focus of ambitious developments of hitherto neglected suburban areas, such as the Champs Elysées. Wauxhalls such as Ranelagh (1774), Cirque Royale (1775) and the Panthéon (1784) saw large bodies of financial speculators invest literally millions of livres in entertainment complexes that combined gardens, cafés, boutiques and salons, usually clustered around a massive central ballroom. In the years following France's defeat in the Seven Years War (1756–63) Wauxhalls were one symptom of Anglomanie. They can also be seen as a polite version of the guinguettes popular with the working class, who patronized such suburban establishments to enjoy gardens, bowls, food, dancing and – thanks to their location outside the city limits, duty-free wine. Promoters presented Wauxhalls as a means of encouraging those who would never think of entering a guinguette to experiment with a new type of entertainment space in which middling and noble ranks could encounter each other in pleasant surroundings. They would, it was hoped, also serve to nudge an overly stratified French society in an ‘egalitarian’ or ‘patriotic’ direction. This temporary laying aside of social distinctions for the purpose of pleasure would, it was believed, teach the better sort how to achieve the same unity in pursuit of other, more important patriotic or national projects of the 1760s and 1770s: the encouragement of commerce and trade, the reconstruction of the French navy and the reform of state finance.Footnote 6 To some extent these projects accelerated the shift from a court- to a Paris-centred culture. In 1785, for example, Queen Marie Antoinette had her architect emulate Paris' Wauxhalls in his designs for temporary winter ballrooms at Versailles.Footnote 7

Figure 1: Vue du Vauxhal de la Foire S Germain (1772), (c) BnF

The combination of emulation and idealism that underpinned these late eighteenth-century pleasure gardens can help us understand how eighteenth-century Londoners and Parisians perceived their cities in two important ways. The first is by considering their relationship to the concept of the ideal, well-regulated city. What did these private enterprises have to contribute to the public project of creating a free, yet ordered, city? Here the concept of ‘police’, in the now archaic sense of ‘regulation’, is of especial importance. Arlette Farge has considered police in the context of the eighteenth century, but her work has focused predominantly on the ‘hard’ police of police spies, prisons and lettres de cachet.Footnote 8 This article seeks to recover a ‘softer’ police, one less centred on a punitive state, one based round the self-regulating ‘amicable collision’ described in Shaftesbury's Characteristics of 1711.Footnote 9 As we shall see, this police could actively resist royal or state agency.

This article finally considers how these resorts served to transport visitors to the other city through carefully packaged fantasies, fantasies that in some cases prefigure the dislocating effects seen in the ‘Parises’ at Las Vegas and Orlando. These ‘virtual cities’ constructed inside pleasure gardens challenge the notion that Mercier's emulation was a one-way process.

Navigating New Bablyon

The crowds that paced the walks and orbited the rotundas within London's pleasure gardens consisted of different ranks and professions. As they promenaded, drank, ate, ogled and shopped they engaged in activities of autovoyeurism, display and consumption that the so-called ‘luxury debates’ of the 1750s had problematized. The chaotic, disordered city was presented as the font of this enervating, vicious luxury in John Brown's well-known jeremiad, the Estimate of the Manners of the Times (1757), a work whose pessimism has to be seen in the military context of the Seven Years War, which started very badly for Britain. London was growing out of control, its population rising from around 600,000 to 950,000 over the course of the century. Paris started from a much smaller base and grew more slowly. Daniel Roche estimates a rise from 500,000 in 1700 to somewhere between 600,000 or 700,000 in 1789, at which point the Revolution led the city to contract in population.Footnote 10 Canute-like attempts by Louis XIV and later monarchs to draw a boundary to the city's advancing tide had, however, highlighted its apparently unstoppable growth. When the War turned spectacularly in Britain's favour, therefore, one found Frenchmen like Fougeret de Montbron adopting a similarly pessimistic view of Paris, or Nouvelle Babylone as Fougeret dubbed it in his 1759 jeremiad against the city's consumptive dissipation. Both Brown and Fougeret argued that circulation of money and people should be slowed and that leisure resorts should be shut down, so that each class would remain ‘within the limits of their rank’.Footnote 11 Works published by Henry Fielding and Ange Goudar in 1755 and 1756 respectively issue similar warnings of the disruptive social and moral consequences of assuming that stable economic and population growth could be achieved by developing a consumer economy.Footnote 12 Those attempting to puff Vauxhall in the 1750s had to be careful, therefore. They could hardly dare deny that luxury ‘makes too rapid a Progress among us’, but nonetheless insisted that pleasure gardens satisfied a valid, polite appetite. ‘Let all Ranks among us be more or less industrious’, one concluded, ‘but let us not be Goths.’Footnote 13

As architect John Gwynn's 1766 book London and Westminster Improved indicates, a decade later little had changed; London was still perceived as anything but an ordered metropolis. For Gwynn it was a pestilential warren of streets clogged with carriages, livestock, corpses, markets and offensive matter with nowhere to go. A ‘Hottentot crawl’ (kraal) is how he summed it up.Footnote 14 Although he noted the existence of newish institutions such as the Foundling Hospital and the Society of Arts, for the most part his short book complains of the urgent need for street widening, the demolition and reconstruction of royal palaces and the relocation of markets and cemeteries to the suburbs. Circulation was the key to establishing a policed city. Gwynn had started his career in the circle around Frederick, prince of Wales, and refused to see royal or state involvement in town planning as unEnglish, but as a reasonable attempt to create a policed city. He cited Louis XIV's public works in Paris with approval.Footnote 15 In the 1760s, Frederick's son, the newly enthroned King George III, began meddling in politics and the arts to a degree sufficient to upset many Britons, not least John Wilkes, who led a noisy and phenomenally popular campaign against the king's ministers. Royal interventions intended to improve London were therefore lampooned as ‘Butification’ – a pun on the name of the king's despised prime minister, the Scot Lord Bute. A 1762 London ordinance sought to improve both the circulation of air and tidy away some of the city's most eye-catching street furniture: its signs. Such a step had been taken in Paris in 1761, much to Mercier's approval. Yet this police intervention was fiercely resisted by Hogarth and others – as a government assault on a quintessentially English art form.Footnote 16 While the Paris parlement ordered the closure of the central cemetery of the Innocents in 1765, London's overcrowded cemeteries blighted and infected its heart until the 1850s.Footnote 17 Yet it is important not to overdraw the contrast between the two cities. Though Paris may have shed its signs, noble resistance prevented the city authorities from taking the logical next step of introducing house numbering in the summer of 1779. Without the new numbers or the old signs (which had been vital to navigation), it could be said the city was left worse off than before.Footnote 18

Guidebooks attempted to create order where there seemed to be none, and form an important source for any discussion of how the policed (policé) city was perceived in the eighteenth century. As the later sections of this article will make clear, these books are (apart from a few drawings and pamphlets) the only sources that survive for Parisian Wauxhalls. Jèze's anonymous État ou tableau de Paris of 1760 attempts to portray the city not as a series of quartiers, but as a collection of institutions, markets and services intended to provide the user with ‘the necessary’, ‘the useful’ and ‘the pleasant’. Each of these categories is itself divided into several sub-headings and sub-sub-headings. Thus ‘education’ comes under ‘the necessary’, but is in turn divided into descriptions of where to find education of ‘necessary’, ‘useful’ and ‘pleasant’ varieties. In lieu of a map the guide begins with a pull-out diagram that lays out the system in all its ramifications. The Paris it presents is one of order among abundance. There is no other city ‘in the universe’, we are informed, where one can find the necessary, useful and pleasant assembled with the same degree of convenience, ‘thanks to the admirable police which one finds reigning there’.Footnote 19

For all its apparent idiosyncrasy, Jèze's Tableau allows us to see how a desire for ‘la ville policée’ was changing the distribution of the city's public spaces, especially those intended for entertainment. It describes fairs under the heading of ‘commerce’, itself a sub-heading of ‘the useful’. ‘Public promenades’ appear under ‘the pleasant’, along with theatres. Fairs are not classified as entertainment, and barely merit any description. The gardens of the Arsenal, the Tuileries and other royal palaces meet with high praise. Their entrances are protected by troops from the Invalides, and ‘soldiers, servants and poorly dressed people’ are excluded.Footnote 20 Inside one can eat and promenade. The guidebook also notes the new boulevards on the edge of the city, which are planted with trees and laid out with sand walks and benches. Here the main sight is ‘the concourse of an infinite number of carriages, which paint a magnificient picture of the taste of this great city’.Footnote 21

These comments confirm a trend David Garrioch and several other scholars have noted, one by which areas of the city became more specialized in three decades after 1760, both in their functions and in the types of people they accommodated. A key development was the 1762 relocation of the Opéra Comique and the acting troupes of Audinot and Collet from temporary seasonal stages at the fairs of Saint Germain and Saint Laurent. Instead of providing a ‘host’ around which less successful troupes, showmen, hawkers and other ‘parasites’ could gather, these performers took up residence in purpose-built theatres in the centre of town. Here different ranks were clearly demarcated by fixed seating, free from the jostling crowds of the menu peuple. The better sort stopped patronizing the suburban fairs. Those fairs that survived were forcibly relocated to new public squares in the rapidly developing western half of the city, where they underwent more rigorous surveillance and rapidly atrophied. Thus the Saint Ovide fair was moved to the Place Louis-le-Grand (now Place Vendome) and then the Place Louis XV (Place de la Concorde).

The charms of equality

Meanwhile the edges of the city were smartened up, with straight boulevards, milestones, benches and allées of trees. People still went there to while away summer evenings, but, again, were now clearly divided along social lines: the lower sort on foot, the better sort in their carriages. Although the mixing of ranks was characteristic of both, the new Wauxhalls were very different from the old guinguettes.Footnote 22 This is made clear by a 1769 lyric drama whose title seems to conflate the two: A.C. Cailleau's Le Waux-hall populaire, ou les fêtes de la guinguette (1769). The hero of this piece of dramatic hackwork (dedicated to Voltaire) is Jean-Philippe, a porter from the Halle au Blé, out to spend his Sunday holiday drinking with his girlfriend Louison. The narrator meets them on the way to the guinguette on foot, which, he claims, is actually a more upright and better form of transport than a carriage.Footnote 23 Once arrived he describes how Jean-Philippe fetches his greasy meal from the kitchens himself, and proceeds to share it with his friends:

After a song interlude another fight breaks out; this time two women are fighting over a man. Before the company heads home to recover before another day's work they decide to have a dance. But they refuse the violinist's offer to lead them in an Allemande ‘like they play at Wauxhall’: ‘Why, do you take us for whores,/And our lovers for vagabonds?/It's okay to love dancing/But that indecent kind/I leave to those fancy balls/Which they give at them Wauxhalls,/Where the nobs go in droves.’Footnote 25 Despite this witty sting in the tail, it is clear that as far as its author was concerned Le Waux-hall populaire was an oxymoron. If anything the title implies that the guinguette, though older, is in fact just a new, low variant of Wauxhall. Both spaces emphasized the mingling of ranks and laying aside of strict etiquette, so it was clearly important for the Wauxhalls to manifest difference by redescribing the established guinguette as a cheap imitation. The drama confirms a trend noted by Isherwood, one by which it was becoming easier to distinguish between licensed, ‘professional’ and ‘policed’ spectacles and the rest, increasingly characterized as ‘plebeian’.Footnote 26 This clarity was, as we shall see, to pose a serious problem for the Wauxhalls.

Wauxhalls also differed architecturally. In contrast to the temporary stalls and tents of the fairs they were highly ambitious permanent structures. Indeed, the Wauxhall became a building type in its own right. Jacques-François Blondel included a model design for one in his Cours d'architecture (1771–77), and a competition to encourage young French architects in the 1770s had entrants all design one.Footnote 27 The rotunda at the largest Wauxhall, the Colisée (architect Louis-Denis Le Camus, designed 1769, opened 1771), had a diameter of 25 metres, and stood next to a huge terrace for fireworks complete with a reflecting pool and enough space for 8,000 spectators.Footnote 28 The social aims of Wauxhall promoters were of equally vast proportions, implying that they were factories for making individuals of different ranks into ‘citoyens’. ‘The people are too much the slaves of the rich’, wrote one advocate of Wauxhalls in 1769, ‘while the rich are too far beneath the people, too little like citizens.’Footnote 29 The same year saw Anne-Marie du Bocage hymn the charms of London and Paris Vauxhalls in similarly egalitarian terms:

As she put it in another poem on the ‘Pleasures of the Waux-Hall’, ‘it's the place where everyone jostles and everyone fits in . . . it makes Paris the perquisite (appanage) of Equality’.Footnote 31

The success of the Wauxhalls became a test sat by French society itself, rather than a commercial endeavour vying for custom. The anonymous author of another pamphlet noted that

Drawn together by shared pleasure, the public becomes its own spectacle: each gives to the others the same pleasure he receives in turn; the whole world contributes to produce one great effect, and nobody considers their pride injured for having provided amusement for others . . . Every class of this public ennobles itself, all seem to make but one rank . . . The Great, the Rich are with the people (peuple), with – to coin a phrase – the world's sea (la mer du monde) that makes up such assemblies; they leave behind their coaches and cortège, which put out the humble bourgeois. Such ill-feelings are like those evil weeds which poison good grain. If they appear among our Wauxhalls we must bid our pleasures farewell, as well as our great national projects – for petty interest will be their ruin.Footnote 32

Though it seems far-fetched to us today, belief in the power of pleasure gardens to reform society can be found in several French works published in the 1760s and 1770s – both those penned by hacks in the pay of Wauxhall shareholders, as well as disinterested Anglophile philosophes such as the Abbé Coyer. Wauxhalls recalled the ‘Golden Age’, and invited comparison with the public festivals of ‘the most highly policed nations’ (les Nations les plus policées), such as the ancient Athenenians.Footnote 33 This ‘Vauxhall utopianism’ was closely related to other cultural initiatives undertaken by the French crown in an attempt to encourage patriotism and improve its own image. One of these involved the court commissioning paintings commemorating great events in French history. Several of these paintings were exhibited in an art exhibition held at the Colisée in 1776, perhaps a response to Coyer's complaint that French public resorts lacked equivalents for the aforementioned history paintings displayed at Vauxhall.Footnote 34 ‘The charms of equality’ unleashed by such resorts were teaching ranks how to police themselves.Footnote 35 Gachet's 1772 pamphlet on the Colisée referred to ‘citizens rendered very policed (policé) by their regular large assemblies’.Footnote 36 This policing process is a product of the Wauxhall crowd's self-surveillance, or ‘autovoyeurism’, as Peter de Bolla has described it in the context of Vauxhall.Footnote 37

In Britain, ‘police’ was always going to be a harder sell. In 1756 Lord Chesterfield had noted in a contribution to The World that ‘We are accused by the French, and perhaps but too justly, of having no word in our language, which answers to the word police, which therefore we have been obliged to adopt, not having, as they say, the thing.’ Two years before fellow contributor Horace Walpole bracketed ‘severe police’ with ‘racks’ and ‘gibbets’, the natural accessories to ‘wooden shoes’, soupe maigre and other Francophobic tropes beloved of Englishmen.Footnote 38 To a profoundly libertarian nation like the English, therefore, there could be a certain amount of nervousness at the mere thought of granting the word English residency, let alone allowing ‘police’ to reorder the city. To men of Enlightenment like Adam Smith, however, the word ‘police’ was vital to the European project of reforming regulation of the economy so as to maximize public happiness and utility – and so we find it used in this sense in his 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments. Footnote 39 Even those less articulate middling men of business who supported Wilkes' anti-ministerial antics in the following decade had good reasons for sharing Smith's enthusiasm for police, albeit one that was largely defined in opposition to a police that served the interests of an aristocratic landowning elite.Footnote 40 Here again, Henry Fielding is an instructive figure. In 1751 he published his Plan of the Universal Register Office. The design of this office was as ambitious as that of Jèze's Tableau, having as its goal ‘to bring the World, as it were, together into one Place’, by creating an office that would put consumers and producers of every kind in communication with each other. As Miles Ogborn has shown, the Fielding brothers' more familiar ‘police’ (in the sense we are more familiar with today) activity had its origins in this attempt to create a higher order in a physically disordered city. The one was based on an ‘ideology of circulation’, the other on ‘the vigorous Circulation of the Civil Power’.Footnote 41

Vauxhall and Ranelagh were models of circulation-friendly planning. Vauxhall's straight avenues appear to stretch to the horizon in Samuel Wale's engraved view of 1751 (figure 2), bisected by shorter ‘cross-walks’ at regular intervals. This grid layout resisted the tendency towards gently curving or serpentine paths observed in garden design of the period. Ranelagh's circular rotunda allowed promenading in inclement weather – the crowd circulated clockwise in the mornings, counter-clockwise in the afternoon, a bell being rung at noon to let everyone know when to change direction. Despite the crowds a French guidebook of 1779 observed: ‘a silence reigns within, one that astonishes foreigners, especially the French’.Footnote 42 The circular or semi-circular lines of supper boxes allowed the crowd to observe itself in a way French and some English visitors found exhilarating. As Mercier noted in his Parallèle: ‘Decorum reigns in these places, where neither embarrassments, nor disputes, nor scandal, nor the impertinent, nor any watch (garde) of any sort are to be found. The company freely and peacefully enjoys itself, each in his own way.’Footnote 43 Equality, independence and police went together.

Figure 2: J. Saint Muller after Samuel Wale, Vauxhall Gardens (1751), Guildhall Library, City of London

The invisible hand

London's pleasure gardens thrived without state or royal involvement. Far from being dependent on royal favour or royal institutions, George II was only able to put on a son et lumière in 1743 to celebrate his own victory at the Battle of Dettingen by borrowing equipment from Vauxhall Gardens' manager, Jonathan Tyers. In Paris, of course, the situation was different, and in order to function operators of Wauxhalls had first to secure a privilège or arrêt from the king, which depended on having contacts at court or on a willingness to pay off the royal Opéra (L'Academie Royale de Musique, established in 1669), which held a monopoly on musical performances in the city. Given the Anglomanie of the de facto prime minister, the Comte de Choiseul, this was relatively easy. Although the finances of the Colisée were anything but transparent (even after the resort's collapse, it took decades to sort out the mess), it seems safe to conclude that Choiseul was himself a major investor, along with three fermiers-généraux with court links.Footnote 44 Though Choiseul fell from power in December 1770, the king's Anglophile brother, Artois, was a heavy investor in the development of the nearby quartier of La Roule, and so the court took a number of steps to encourage Parisians to visit the Colisée, by relocating or shutting down rival attractions. Despite such efforts the resort did not survive long.Footnote 45 Bought by Artois in 1779, the site subsequently played host to another experiment in English urban design: a housing estate called ‘Nouvelle Londres’, designed by François-Joseph Belanger. This was made up of relatively modest, two-storey terraced houses, a striking contrast to the more ornate apartment blocks rising elsewhere in the city.Footnote 46 But other Wauxhalls kept operating until the mid-1780s. In 1784 Anna Francesca Cradock was able to visit two in one night (a Sunday), admiring the gardens, see-saws and ballroom at the Redoute Chinoise and then moving on to Ruggieri's Wauxhall to catch the fireworks.Footnote 47 Reorganized along a subscription system in 1784, the Parisian Ranelagh lasted until 1830.Footnote 48

French guidebooks to London recorded with some bitterness British claims that French attempts to recreate Vauxhall in Paris were a fool's errand. In his 1770 guide to London the Swiss Pierre-Jean Grosley observed that ‘the English claim that similar pleasures could never thrive in France, thanks to the unruly humour (l'humeur tapageuse) of the French’.Footnote 49 Five years later Pidansat de Mairobert may have been satirizing such claims when he had the eponymous ‘Milord All'Eye’ of the Espion Anglois write in a putative letter home to an English friend:

The French, my Lord, ape us in everything. They, too, have their public resorts, promenades for layabouts to walk in, resorts that bear some relation to ours, but which only go to show the futility of the endeavour. You never see those happy parties gathered at tables, where the spirit of sociability and the softest sentiments are displayed. They have done nothing to make these gardens a political institution (institution politique) by putting on show the sort of paintings we have in ours, capable of arousing the love of glory among our fellow citizens through the spectacle of our victories and the defeats of our rivals. They do not use music to cheer the place up, to create another type of spectacle, that pleases the ears and moves the heart. The pleasure gardens here are so empty, in fact, that one is regularly reminded of the words of one foreigner, who, after spending a long time walking round the Colisée seeing the same crowd of men and women circulating round and round the same point, cried out: ‘When's it going to start?’Footnote 50

It seems odd that the circulation that appeared so exciting in London was less satisfying in Paris. One reason for criticism of Wauxhalls (and in particular the Colisée) may be that visitors were aware of the political agenda underpinning such enterprises, and suspected the invisible hand which kept people circulating inside them of being an extension of the court. The bookseller Bachaumont carefully observed the rise and fall of the Colisée in his Mémoirs secrets. He noted the project's financial backing by the City, the fermiers-généraux and the Conseil d'État, and concluded that this ostensibly private resort had in fact become ‘an affair of state’.Footnote 51 Mercier's visit to the Colisée left him exasperated with ‘the laymen with their noses in the air [who] circulate and crowd around’. In the end it drove him to ask: ‘Who does not meddle in our pleasures – that is to say, who does not spoil them for us? Authority presides at all our diversions; Authority arranges them for us, and it is impossible for us to modify them.’Footnote 52

Milord All'Eye was wrong. The problem was precisely that Wauxhalls had been made a ‘political institution’, but in a most curious fashion. The court was using the absolutist tools at its disposal – privilèges, arrêts, fermiers-généraux – to take apart and reconstruct public leisure and its geography in a consensual, market- and public-friendly form. The uncanny sense that new spaces for ‘free’ circulation were in fact being manipulated by the court was given added resonance by the French government's experiments during the 1760s and 1770s in removing restrictions on the movement and trading of grain. Unfortunately rumours spread that speculators – including the king himself – were profiteering, leading to a series of grain riots across the country.Footnote 53 These experiments at free circulation were, like the Wauxhalls, an attempt to emulate British models of circulation. They suggest that circulation could continue to inspire a certain amount of fear and suspicion, albeit a fear of a different kind from those luxury-based fears expressed back in the 1750s.

Pleasure gardens provided eighteenth-century Parisians and Londoners with an opportunity to envisage a higher social order underpinning apparently chaotic urban growth. The ease with which order was maintained, and the patriotic promise the gardens enshrined, suggested that commercial circulation and widespread emulation of the elite did not add up to a recipe for social and moral collapse. Concerns remained in Paris, however, that spaces supposedly devoted to ‘the charms of equality’ were just a new type of absolutist theme park, a political illusion. As we have seen, for Mercier the Wauxhall fantasy was just too fantastic to be pleasurable. It was unreasonable, he argued, to expect les grands and les petits to come together.Footnote 54 The regime's attempt to encourage ‘freer’ forms of assembly was also belied by the introduction of patrols of Gardes-Françoises to public resorts around mid-century, one of a series of ordinances handed down by the lieutenant general of police, Marc Réné de Voyer, marquis de Paulmy d'Argenson.Footnote 55 A Garde keeps watch in Gabriel de Saint Aubin's sketch of the Colisée interior (Figure 3) – the only fixed point in a maelstrom of movement. The confused reaction to the introduction of Wauxhalls suggested that Shaftesbury had been right to warn of the futility of trying to encourage that ‘amicable collision’ which fostered a polite public. In his Characteristics (1711) he had argued that to attempt to police such interaction (even with the intention of encouraging it) would inevitably destroy the very civility it claimed to promote.Footnote 56

Figure 3: Gabriel de Saint Aubin, interior view of the Colisée (1772), by kind permission of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection

One of the fantasies pleasure gardens therefore offered was that police and égalité could be realized in the same city. Another fantasy they supplied was that of being able to visit the rival capital without leaving one's own. In so far as Paris was associated (in English minds, at least) with politeness and ‘hard police’ and London (in French ones) with cut-throat commerce and a jostling, licentious liberty these fantasies were another way of thinking about the free yet policed city. Virtual visiting was rendered even more appealing by the difficulties of travel. Horace Walpole thus warned readers of The World not to expect the same standards of behaviour from continental highwaymen. English ones were, he facetiously claimed, ‘more polite than French ones’, who lacked any ‘scavoir vivre’.Footnote 57

Though not necessarily pleasant, travel was a luxury, and while the flow between Paris and London was generally stronger in the direction London–Paris than Paris–London French Anglomanie during this period more than compensated for the smaller numbers of French tourists in London. Plays by Samuel Foote and prints satirized both The Englishman in Paris (1753) and The Frenchman in London (1770), making them into well-worn stock characters, to the point where going to the theatre and seeing oneself pilloried was itself incorporated into guidebooks. Francois Lacombe's 1777 Londre [sic] et ses environs thus recommended a visit to Foote's theatre, to see how Parisians were made fun of. They could, he noted, have their revenge by looking at the native female spectators: ‘English women ape the fashions of Paris to such an extent, they are the laughing-stock of all Europe.’Footnote 58

One of the most dramatic examples of how London pleasure gardens facilitated a ‘virtual visit’ to Paris was the extravaganza organized at Marylebone Gardens (Figure 4) in 1776. Located on Marylebone High Street, on an eight-acre site covered today by Devonshire and Weymouth Streets, it had initially opened in the mid-seventeenth century as a bowling green linked to the nearby Rose of Normandy Tavern. Daniel Gough reopened it as a pleasure garden in 1738, charging one shilling admission and offering food, wines and a band performing ‘concertos, overtures, and airs’.Footnote 59 Its layout consisted of the usual tree-lined allées, a large assembly room and a temple or ‘Great Room’ (erected some time before 1746). Like Vauxhall, it was on the edge of town, although the laying out of a major new thoroughfare to the north (Marylebone Road) in 1757 effectively cut it off from the fields that had previously been its backdrop. In 1776 it unveiled a new alfresco entertainment called ‘The Boulevards of Paris.’ This consisted of a series of stalls set up in imitation of a Parisian shopping street, and may have built on the area's association with the French Huguenot community in London, which had its church next to the Gardens. One newspaper described the show as follows:

The public has been informed that Representation of the BOULEVARDS of Paris was to be given; and considering this as an attempt only to represent that busy chearful Spot, it is undoubtedly entitled to the Applause it met with. The Boxes fronting the Ball-room, which were converted into Shops, had a very pleasing Effect, and were occupied by Persons, with the following suppositious Names, legible by means of transparent Paintings: – Crotchet, a Music Shop; a Gingerbread Shop (no Name over it) the Owner in a large Bagwig, and deep Ruffles, a-la-mode de Paris . . . La Blonde, a Milliner; Pine, a Fruiterer; Trinket, a Top Shop; Filligree, ditto; Mr Gimcrack, the Shop unoccupied, and nothing in it but two Paper Kites; Tete, a Hair-dresser. The Shopkeepers seemed rather dull and awkward at their Business, till the Humour of the Company had raised their Spirits by purchasing. Madam Pine, Messieurs Trinket, and the Marchand de la Gingerbread, ran away with the Custom from all their Competitors.

Inside the ballroom was illuminated with coloured lamps, and furnished at one end to look like the English Coffee House at Paris, ‘but the Mistress of it had too modest, too reserved a Behaviour, to give one the least idea of her being a Vender of Parisian Refreshment. Even a Quaker might have taken his Oath that she had never been within Sight of Calais.’Footnote 60 The display was repeated and new features added over the following weeks, creating an even more elaborate Paris. It was repeated the following year, Marylebone's last.Footnote 61

Figure 4: John Donowell, view of Marylebone Gardens (1755), Guildhall Library, City of London

Marylebone's Paris was not the ‘old Paris’, but the new Paris of the Boulevard du Temple, the increasingly fashionable Saint Honoré and the Champs Elysées: straight lines, wide carriageways, new shops and new leisure resorts. Marylebone's 1776 extravaganza is one example of how pleasure gardens transplanted visitors to the rival city, from London to Paris, in this case. As a ‘representation’ it admittedly had its limitations, as French observers noted. ‘Ma foi!’, a ‘French Gentleman’ supposedly commented on visiting the ‘Boulevards’, ‘It is a passing resemblance – but it is not quite right.’Footnote 62 The spectacle suggests that pleasure gardens were about more than ‘imitation’ of distant locales and the tastes and manners associated with them. They transported visitors to cities that did not exist.

Changing places

The apparently straightforward question ‘Who imitated whom?’ is a difficult one to answer, therefore. Vauxhall and Ranelagh predated Wauxhalls by many years, and the very label makes the initial debt obvious. After 1770, however, it becomes harder to distinguish between the original and the émule. Paris innovated by establishing indoor ‘Wauxhalls d'hiver’, a concept that would have appeared oxymoronic in London. It was suggested, for example, that the Grande Galerie of the Louvre might be turned into a ‘Wauxhall d'hiver’.Footnote 63 Boutiques, too, had not been in evidence at London pleasure gardens before Marylebone's ‘Boulevards of Paris’, but were a regular feature in Wauxhalls. The Wauxhall at the foire Saint Germain (est. 1768, see the plan in Figure 1) had a confectioner, perfumer and a modiste; the massive Colisée (1771) had all these and a jeweller.

Fireworks were another feature of pleasure gardens in which French Wauxhalls seemed to be leading the way. Originally imported from China in the fifteenth century, absolute monarchs like Louis XIV and to a lesser extent the Catholic church initially succeeded in monopolizing their use, as a particularly spectacular means of legitimating themselves. In France only a limited number of licensed artificiers du roi could make, sell or use them. Fireworks had been used in England in the seventeenth century to create sound effects, but otherwise they were also rarely heard or seen outside the court. Though some were let off at London's Ranelagh in the 1760s, it took another twenty years for them to reach Vauxhall, and they only became a regular feature there from 1798.Footnote 64 In Paris pleasure gardens and fireworks were closely connected from the start. Two of the most important impresarios of Parisian pleasure gardens were Italian pyrotechnicians: Jean-Baptiste Torré, who founded the first ‘Vauxhall’ in 1764 (and who later managed the Colisée), and the Ruggieri brothers, who started their Wauxhalls just a year later. The latter had been hired by George II for the aforementioned 1743 Green Park display, and would go on to stage the even more disastrous display held on the Place Louis XV on 30 May 1770. Intended to celebrate the nuptuals of Marie Antoinette and the Dauphin, the future Louis XVI, this went terribly wrong, causing a public stampede that killed 133.

Torré and the Ruggieri brothers brought the hitherto exclusively royal feux d'artifices historiés to the paying public for the first time.Footnote 65 Torré brought his skills to Marylebone Gardens in 1772. In 1774 he put on a show there entitled The Forge of Vulcan under Mount Aetna, which, an advertisement claimed, would be performed ‘in the same splendid Manner, in which it was exhibited before the Court of France last Year, on the Marriage of his Royal Highness the Count D'Artois’.Footnote 66 The perilous combination of fireworks, large-scale scenery and a vertiginous descent along a high-wire by an artiste with further fireworks strapped to their body was first attempted at the Colisée in 1773. This was later to become a signature act at Vauxhall, the French ‘Fire Queen’, Madame Saqui (Marguerite-Antoinette Lalanne), making her first descent in 1816.Footnote 67 Ballooning, too, was first seen at Ruggieri's Paris garden, in 1786, as a platform for launching fireworks. ‘Fire balloons’ did not become a feature of London's pleasure gardens until forty years later.Footnote 68 Lalanne was one of many performers (including singers, slack-rope artists, acrobats) to appear at pleasure gardens on both sides of the channel. Many of these performers, however, were far from being particularly French or English, though there were exceptions, such as les coqs anglais who performed ‘English-style’ cock-fights at the Colisée in July 1771.Footnote 69

The Parisian fad for pleasure gardens which peaked around 1775 seemed to go into decline after 1784, the year Torré's and Ruggieri's Wauxhalls were demolished. The Panthéon designed by the architect Lenoir in 1784 was the last Wauxhall to be built, and even though it had a prime location opposite the redeveloped Palais Royal it struggled more or less from the beginning.Footnote 70 In 1788 it added a bain public and in 1791 it was converted into a theatre. But there was still at least one ‘Wauxhall d'Été’ around in 1790, when a firework gala was staged to celebrate the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille.Footnote 71 Ranelagh managed to survive until 1830, helped by its location near the Bois de Boulogne. In London, Vauxhall managed to keep going until 1859, and the rather less select Cremorne Gardens enjoyed great popularity right up to its closure in 1877.Footnote 72 The years between 1764 and 1784, however, mark the highpoint of pleasure gardens as quasi-utopian spaces in which to envisage a whole society at play, yet under control.

1784 represented a turning point both in the demolition of the two original Wauxhalls, as well as in the opening of the Palais Royal. The Palace had been given to Louis-Philippe-Joseph, duc de Chartres in 1776 by his father, the duc d'Orléans. Chartres was an Anglophile and habitué of the Wauxhalls; he had his own loge at the Saint Germain ‘Vauxhall’ (indicated in Figure 1). His decision to chop down trees and develop the large garden on the site met strong opposition from Parisians who had long promenaded there. The prince's right to consider it his own property was challenged by the author of one pamphlet on the subject, framed as a letter from ‘an Englishman settled in Paris’ to an English lord. To cut down the allée was, he argued, to cause ‘a lesion in public order, for on that established order depend an infinite number of things which cannot be destroyed, without causing a violent upset in the public mind (‘une révolution dans l'esprit des hommes’).Footnote 73 Chartres owed every single écu of his income ‘to the ancestors of those he today refuses to allow to promenade in his garden’.Footnote 74 What he failed to realize was the potential disasters that large cities contained within them:

Up until this point, my Lord, I have only drawn you a picture of the violent change (révolution) which the destruction of the great allée has brought about in the public mind. I have still to speak of the actual damage it has caused to the inhabitants – damage of a sort you would find difficult to imagine. I will give you a sketch, which you will insert in the annals of London. It cannot but be of some moment for the history of our world that all posterity should know that the removal of a promenade in this capital caused the ruin of 20,000 of its inhabitants. This anecdote is more interesting than one could ever imagine. It serves to demonstrate that in France just as in England there lies a flaw in the economy of peoples, and that London and Paris are too big. Every time, my Lord, that a government has allowed a million men to be shut up in a confined space of small circumference, the slightest small alteration it has made in it has caused a great revolution (une grand révolution). It is cause and effect.Footnote 75

Governments should, he argued, pay greater attention to such matters. The space and popularity of the old garden had made it crucial to the physical and economic health of the city, by providing a place for merchants of all nations to meet and transact business. It provided layabouts with something productive to do: walking for its own sake.Footnote 76 As well as foreshadowing the flâneurs Paris would produce in the following century this pamphlet shows just how far we have come from Fougeret de Monbron. Whereas in the 1750s circulation was something to be regulated by the state from above and kept within tight confines, by the 1780s it has taken on a life of its own. Even the slightest attempt to interrupt or divert the crowd's movement will overwhelm those arrogant or foolish enough to claim mastery of the ground under their many feet.

When the three-sided colonnade of 60 pavilions designed by Victor Louis opened in April 1784, however, critics and cassandras alike were rapidly silenced. The new Palais was just like the old, only better. Mercier called it ‘a small luxurious city enclosed in a large one’.Footnote 77 The Palais Royal complex was in a way a natural development of the Wauxhall phenomenon. When Mrs Thrale visited Paris she noted the outcry over the chopping down of the original trees. ‘The court had however Wit enough to convert the place into a sort of Vauxhall, with Tents, Fountains, etc., a Colonnade of Shops and Coffeehouses surrounding it on every side’.Footnote 78 Many of the pavilions were filled, not with shops, but with commercially operated museums, and clubs such as the ‘Club des Planteurs’, the ‘Club Militaire’ and the ‘Société Olympique’, associations aimed at planters, holders of the prestigious Croix Saint Louis and chess players respectively. Many of these institutions afforded further examples of Anglomanie. Scholars continue to debate the extent to which ranks mingled at the Palais Royal.Footnote 79 Yet it is clear that the Palais' arcades foreshadowed the more familiar boulevards of Haussmann's Paris a century later, a development which would turn the tide of emulation between London and Paris decisively in the latter's favour. The Wauxhalls played a part, if a small one, in making that ‘new’ Paris possible.

Pleasure gardens tamed those fears surrounding commercial expansion of the metropolis common at mid-century, challenging the belief which linked circulation of luxury commodities with social dislocation, with confusion rather than cohesion. This belief had been shared by both Londoners and Parisians. It would be relatively easy to construct an argument which had each holding the other responsible for the ‘infection’ taking hold in their own city, whether it be that British ‘Carthaginian spirit’ feared in Paris, or the French luxury feared in London.Footnote 80 The straight walks and elegant rotundas, however, suggested that circulation could be a source of pleasure, rather than dizzying, and a spectacle in its own right. As Mercier saw it, identifying Britain and France as natural and necessary enemies was not only unhelpful, it almost smacked of conspiracy:

If the two nations would only show some patience rather than prejudice they might find themselves in a position to help and instruct, rather than destroy, each other. Yet the French government fears nothing more than that the spirit of the English nation might arise in France, while the English nation fears nothing more than French tastes, fashions, manners and habits – and that the spirit of the French government might arise in England. This is what keeps the two nations apart.Footnote 81

Pleasure gardens showed that Mercier was right: Paris and London could enjoy a truly co-operative relationship, could indulge a healthy fascination for each other. They could swop places. London's pleasure gardens moved to the boulevards of Paris, while the boulevards of Paris moved to the pleasure gardens of London. While both may have been located on the periphery of their respective cities, comparing gardens takes us to the heart of how both London and Paris were imagined, both as corrupt ‘New Babylons’ and utopian villes policées, as voisines and rivales.