This article explores the making of two central markets in (post-)colonial sub-Saharan Africa from a comparative perspective. In both Dakar (Senegal) and Kinshasa (Democratic Republic Congo), as in many other African cities, the marketplace has always been an organizing principle within the urban fabric. While the importance of the marketplace in Africa definitely predates the colonial occupation of the continent, the colonial period was a turning point in terms of architectural articulation, urban morphology and the physical location of the marketplace, as well as its economic and political orientation. In the colonial society and city, which was largely characterized by racial segregation, marketplaces played a crucial role, as they formed one of the rare spaces where the various population groups encountered each other. Whether showing continuity or discontinuity with colonial modes of planning, in post-colonial cosmopolitan Dakar and Kinshasa, the role of the various population groups and agencies in the spatial production of the marketplace is an ongoing process.

While this comparative study engages with some of the central issues raised by Stobart and Van Damme in the introduction to this issue – such as the way that markets shape cities and define urbanity – it also problematizes other issues, inherently related to the geo-political specificity of the two cities discussed. Characteristics of market development in (post-)colonial Africa essentially differ from those in the west, where markets played a key role in the construction of the ‘modern’ industrial city, of bourgeois and liberal society and of democratic citizenship. In the colonial urban environment, administration and commerce were far more important than industry. As a result, ‘top down’ processes of social engineering and surveillance of the colonized ‘other’ were especially relevant to the spatiality of the market – thus paving the way for ‘bottom up’ dynamics. In addition, as is clear from the other contributions to this issue that deal with the global north, the municipal market model, the political arena and private vendors were united in asking for a ‘common good’ and acting through some solidarity of interests. Yet this situation has rarely existed in (post-)colonial sub-Saharan Africa. The history of this region shows that pressure groups such as modern elites, the bourgeoisie or land owners were far from as dominant as they were in industrializing Europe. Thus, appeals on their part to the municipal body to act in accordance with urban growth in terms of infrastructure and market provision could pass almost unnoticed by the (post-)colonial states.

Drawing on primary and secondary sources and on work in situ, this article scrutinizes to what extent colonial planning policies, and their unforeseen consequences, defined the urban form of the central marketplaces in Dakar and Kinshasa, under French and Belgian colonial rule respectively. As the marketplace can be seen as the outcome of a continual process of urban agency between different actors in the colonial society, the various ways in which local actors contested French and Belgian planning policies are also studied. With regard to the urban form of the marketplace, the spatial considerations in the establishment of the markets themselves are analysed, with reference to debates on urban segregation during the inter-war period and their influence on the (re)location of the marketplace in the city. The marketplace also formed a place where strict segregation on a racial basis could be negotiated, and, more particularly, the relations between the contemporary ‘sanitary discourse’ and the spatiality of the marketplace. Manifested in the urban form, (pseudo-)sanitary considerations resulted in a gradual exclusion of the central marketplace from the European part of the city, a process that changed the urban fabric considerably.

In spite of the fact that the position of these markets was once again challenged in the post-colonial era, these markets still stand today at the core of urban identity, playing a key role in their respective cities, countries and even beyond. While Marché Sandaga is situated in Dakar's commercial and administrative heart, and on the junction between major regional and international transportation routes, Kinshasa's Marché Central, called Marché Public during the colonial period, can be considered as one of Africa's largest marketplaces, accommodating more than 30,000 merchants – almost 10 times its planned occupancy. Remaining by far the most important sites for the interplay of interests, lifestyles and cultures and major places of exchange and encounter, these markets are continuously being (re-)produced by multiple and intricate forces, agencies and intermediary groups.

In order to understand the role of these markets in contemporary Dakar and Kinshasa, it is vital to trace them back to their historic origins. By confronting a series of planning projects that were proposed for the marketplaces with a variety of sources, and by analysis on the micro-level, this article tries to establish a richer understanding of the mechanisms and limits of (post-)colonial planning. On the level of historiography, within the limited literature on (post-)colonial urban planning cultures in sub-Saharan Africa, comparative studies that deal with the planning (and architecture) of two or more colonial powers are rare,Footnote 1 and few deal with market spatialities. This article intends, inter alia, to address this neglected area.

The genesis of Marché Sandaga and Marché Central

The title of this section does not suggest that the sole genesis of both marketplaces was the pioneering colonial endeavour rising out of a former terra nullius. Although, especially in pre-colonial western Africa and on the lower Congo River, there were occasional markets outside cities, African cities could never be imagined without markets as an integral component of their spatiality. The existence of the market, as an historical institution, depended on several factors, such as agricultural hinterland and the complex organization of political authority, trading networks and specialized groups in the collection and redistribution of supplies.Footnote 2 Colonialism, however, distorted the pre-colonial configuration and location of towns. Because its impact was essentially political and economic, some of the old caravan routes and inland commercial centres were effectively destroyed. The spread of cash cropping and the advent of a new revolutionary mode of transport, the railway, reoriented previous demographic, farming, settlement and trading patterns.

The origins of Marché Sandaga date back to 1862, with the establishment of Dakar as a colonial city immediately after the French occupation of the Cap Vert peninsula, over which Dakar now extends. Dakar's master plan presented an orthogonal vision in which two marketplaces are clearly visible on both sides of Place Prôtet (today's Place de l’Indépendance) – designed as the hub of the colonial city, with major administrative and transport functions. The first marketplace was that of Kermel, near the port, and the second was that of Sandaga, on the main caravan route to the hinterland (Figure 1).Footnote 3 In contrast to Kinshasa's Marché Central, which was displaced several times, Kermel and Sandaga squares have preserved their original function as urban markets up to the present day on their original 1862 sites. The Sandaga market became the prominent market at the expense of that of Kermel only upon the inauguration of its new structure in 1934; and, by the post-colonial period, Sandaga's supremacy had further increased, with Kermel subsequently serving as a food and artefacts market, mostly for the Senegalese bourgeoisie, foreign residents and tourists.

Figure 1: Early colonial Dakar in 1862. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

One of the striking features in Dakar's master plan was the drawing of its orthogonal grid on the site of ‘Ndakaru’ – a sparsely populated pre-colonial settlement of the Lebu people, made of eleven straw-hut villages on Cap Vert. The market square of Sandaga was placed over ‘Santiaba’, one of these villages which is also indicated on the master plan, and from which ‘Sandaga’ derives its name (Figure 1). As Dakar's master plan symbolized the metamorphosis of Ndakaru into a ‘real city’ of regular layout and permanent edifices intended for a European presence, it had been realized through Lebu expulsions from this newly established colonial ‘heart’. Some of their villages had been displaced several times to the expanding margins of the city by the 1910sFootnote 4 – a continual process that was sometimes inspired by sanitary orders. Yet in creating a de facto residential segregation on a racial basis, the French colonialists – in contrast to their British and Belgian counterparts – never used racial reasoning officially. Sandaga's square was still located within the ‘European’ city centre, but close to its western margins.

Like French Dakar and other contemporary colonial cities, Kinshasa, the former Léopoldville, was highly segregated along racial lines. Here, too, the binary structure of the city came into existence informally, since before 1930 there were no explicit ordinances favouring segregation on racial grounds. While the authoritative and paternalistic policy of the Belgian colonial government was from the outset marked by extreme segregationist tendencies, it was only in the 1930s that racial segregation in the city evolved from an improvised practice into an institutionalized policy. Before 1929, when Léopoldville became the actual capital of the Belgian Congo, the residential separation of colonizer and colonized was realized by an undefined ‘no man's land’. Originally, the market of Léopoldville, one of the first public facilities of the city, was situated in this ‘no man's land’ between the African and European quarters as it was one of the rare public functions that was shared by both communities (Figure 2).Footnote 5

Figure 2: Kinshasa in the mid-1920s with the shifting location of its marketplace. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

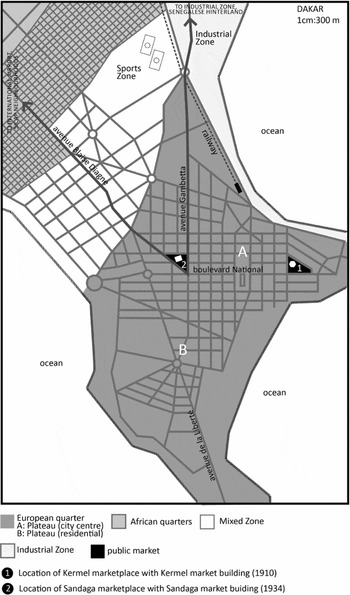

Because of the limited available space in the city centre, from the 1920s onwards, the European town gradually extended into the ‘no man's land’ and as a result neutralized the railway as a physical barrier between both communities.Footnote 6 Tradesmen followed this expansion of the European town in the direction of the African quarter and established a new commercial district on the boundary of both quarters, the most favourable position for trading. In 1925, a new market building was constructed in the middle of the new commercial district, by a Jewish businessman from Rhodes.Footnote 7 As a consequence, the new commercial district was gradually transformed into the main city centre of Léopoldville. Many of the tradesmen in the surroundings of the market were of Portuguese, Greek and Italian descent, and due to their willingness to talk local languages and their slightly darker skin in comparison to Belgians, spatially as well as sociologically they occupied an intermediate position in the colonial city.Footnote 8 The diversity of nationalities around the public market gave the city centre a cosmopolitan character and weakened the physical barrier between the European and African quarters on a micro-level (Figure 2). As for Dakar, aside from an African in-migration of various ethnic groups who were gradually attracted to the colonial urban pole, its cosmopolitanism was characterized already by the 1910s with a growing Luso-African, métis and Lebanese presence.Footnote 9 These groups became important in the city centre, especially following the establishment of the Plateau as a prestigious quarter for French expatriates south of the city centre. The city centre thus became the commercial centre – governed by Sandaga and Kermel – but also retained administrative and residential functions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Dakar in the mid-1910s with Sandaga and Kermel marketplaces. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

Marché Sandaga and Marché Central in the inter-war sanitary discourse

The establishment of the ‘native quarter’ (i.e. the ‘Médina’) in Dakar in April 1914, as a consequence of a severe outbreak of bubonic plague, could be regarded as the most drastic segregationist move in the history of the city.Footnote 10 Indeed, the previous relocations of the Lebu residences outside the city centre – mainly by the Comité d’Hygiène et de Salubrité Publique, created in the 1880s – were not systematic.Footnote 11 In the first weeks after the plague's outbreak, the idea of complete separation between the city centre Plateau and the quartiers indigènes was still not apparent. Initially, two cordons sanitaires were established, placing large parts of the country and the city in quarantine and with no free movement of Africans permitted.Footnote 12 But since they were inefficient and disrupted the city's commercial life, these cordons were only temporary. A few months after the April outbreak, a new village de ségrégation exclusively for Africans, the ‘Médina’, was established by the colonial authorities at a distance of 800 metres from the Plateau. A permanent cordon sanitaire between Europeans and Africans had now thus been created (Figure 3). Offering parcels of sandy land with elementary installations, it was intended to accommodate the African population transferred from the Plateau due to their use of ‘sub-standard’ building materials.

Sandaga square was accounted for within the original master plan, and thus was still included within the ‘protected’ area, but it was situated on its extreme end to the west. It was on the border of the cordon sanitaire and the Médina and African quarters beyond. The square and its environs was the site of the indigenous ‘Santiaba’ – the pre-colonial toponym was still preserved – now engulfed within the French system of streets and avenues. However, this area was considered as a ‘Plague Zone’ in Dakar, and therefore was subjected to the harshest anti-plague measures. The entire population (about 3,000 people) was evacuated in August 1914 and spent 10 days at the newly established lazaretto at its north, and was then forced to resettle at the new Médina while all its straw huts were burnt.Footnote 13 But the enforced transfers from the city centre to the Médina were never completed. This was because of a variety of local, regional and international reasons related, inter alia, to the timing of the outbreak of World War I, and to the regional status of Dakar.

In the light of the already apparent indigenous anti-segregationist protests in Marché Kermel, where agitated merchants refused to sell food to Europeans,Footnote 14 and the spatial position of the Santiaba area, closer to the indigenous quarters and the cordon sanitaire, plans were made to shift the commercial weight from Kermel to Sandaga. A series of blueprints for this shift were issued following the war, in the 1920s,Footnote 15 though the building of Sandaga itself – the same village that we see today – was not completed until August 1934. As to the permanent cordon sanitaire, it was preserved by Dakar's authorities well after the end of the plague in January 1915, throughout the late 1930s.Footnote 16 In the inter-war period, public amenities were built in this ‘neutral’ zone, such as a racecourse and a stadium (Figure 3).

Similar developments occurred in Léopoldville where, by the beginning of the 1930s, the blurring of boundaries between the African and European quarters became a major colonial concern. Here, too, the ‘sanitary syndrome’ was in operation as a pretext and legitimation for racial segregation.Footnote 17 According to the Public Health Department (Service d’Hygiëne), an unoccupied neutral zone (zone neutre) of 800 metres had had to be implemented in Léopoldville. Its supposed purpose was to avoid the transmission of malaria from the African quarter into the European town.Footnote 18 Although a segregationist plan, developed by the Colonial Office in Brussels in 1931, existed for a neutral zone in Léopoldville,Footnote 19 it was mainly the guidelines of the Public Health Department that determined the decisions of the city council (Comité Urbain)Footnote 20 as no local town planning department existed during the inter-war period.

In 1933, the Comité Urbain began, at the request of the Public Health Department, the implementation of the cordon sanitaire by the expropriation of the upper part of the African quarter and the establishment of a series of recreational facilities for Europeans. Here, the latter consisted of a zoo (le Jardin Zoologique), a park (Parc De Bock) with botanical gardens and, in 1936, a golf course (Léo Golf Club) (Figure 4). Although the expropriation of Africans was relatively inexpensive, it proved very difficult because no accommodation was prepared by the Comité Urbain for the Africans who were to be relocated. In addition, the implementation of the cordon sanitaire was obstructed by the presence of a small garden town for Europeans who were reluctant to move and obtained permission from the Comité Urbain to stay. As a result, only a small strip of 300 metres, instead of the original 800 metres of the cordon sanitaire, was actually completed.Footnote 21

Figure 4: Kinshasa in the mid-1940s with the shifting location of its marketplace. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

Yet, from the beginning of its creation, this spatial segregation was challenged by Africans travelling to the public market of Léopoldville, still located in the European quarter. Moreover, parts of the cordon sanitaire were gradually being appropriated by Africans in order to establish new markets that were nearer the African quarters. One of these new markets was the Marché de Tabora, established mainly by West and East Africans (Figure 4). Such unofficial activities obscured further implementation of the cordon sanitaire and, because of economic interest and fear of resistance, were tolerated by the Comité Urbain.Footnote 22 Therefore, while Africans were barely involved in urban planning, the ambivalent choices of the Comité Urbain regarding the public market allowed them to establish informal markets and to escape to some extent from the segregationist restrictions. This gap between official colonial planning interests and de facto implementations is evident in the case of Dakar.

Meanwhile, in Léopoldville, the presence of African tradesmen and customers around the public market in the European town engendered protests and complaints by many Europeans, who proposed to erect two separate marketplaces: one in the European town and one in the native quarter.Footnote 23 Reluctant to establish public functions in the African quarter, the Comité Urbain moved the market to the neutral zone in 1943 to remedy the situation (Figure 4).Footnote 24 In favour of a more strict segregation, this resettlement of the marketplace did not please the expatriate community. Yet the design of the new market building seemed to be a good compromise, as it was totally closed at the side towards the European town, and in this way the Europeans did not have to see or smell it.Footnote 25 The decision of the local government to position the market, a proven space of encounter, in the neutral zone, which by definition was intended as a space of segregation, may seem contradictory, if not ironic. Moreover, this relocation further hindered the implementation of the neutral zone, as it would only result in the additional passage of Africans into the neutral zone. Although all members of the Comité Urbain agreed on the principle of the neutral zone, as in Dakar, local interests, pragmatic considerations and a quest for immediate remedies prevailed in the implementation process.

The markets and post-World War II planning: encounters in the ‘zone neutre’

In the post-war era, colonial states pursued more interventionist policies in sub-Saharan Africa and set up comprehensive socio-economic development plans to organize the growth of urban centres and to enhance the welfare of the colonized people. In the French colonies, such developments were motivated by reforms aimed at the integration of the colonies into a broader French Union (Union Française, 1946), and then more substantial autonomy following the ‘Loi Cadre’ of 1956. In the Belgian Congo, these were motivated by the paternalistic belief that economic betterment was more important for Africans than political liberty. By the mid-1950s, while Britain and France were reforming their colonial relations with most of their colonies in Africa, colonialism in the Congo seemed stronger than ever, and was still curtailing the freedom of African political organizations.Footnote 26 In both French and Belgian colonies, the post-war development project was an ambiguous enterprise, as it formed a justification for a solid continuation of colonial rule at a time when the ‘colonial state – really for the first time – faced a sustained and serious challenge of legitimating its rule to the subject population’.Footnote 27 These somewhat equivocal policies were mirrored in their accompanied urban planning proposals, bringing to the fore the role of the markets within the growing urban agglomerations. Interestingly, in both Dakar and Léopoldville, this role was directly related to the further divergence of the cordon sanitaire or the neutral zone from their original segregationist function. For different reasons at each site, this divergence was not always preplanned or well controlled by the formal planning apparatus.

In Dakar, a mission d’urbanisme was invited after the war in 1945 to prepare a master plan for the entire peninsula. Based on earlier plans, this master plan showed, among other things, a clear end to the policy of housing the emerging African middle class, introducing a socio-economic differentiation within African society.Footnote 28 ‘Development’ and ‘efficiency’ were amongst the new technical vocabulary that was now used, together with a preoccupation with zoning principles – not only differentiating between functions but also between racial and socio-economic groups. In the master plan, different zones were assigned to different population groups. For example, the elite of Africans who lived according to French values and standards, the so-called évolués, were placed in-between the residential quarters for Europeans and Africans.Footnote 29 The site of Sandaga – which, in the 1930s, was empowered by the colonial authorities by the erection of the market building and became a central point by the late 1940s – not only stood at a meeting point between several such ‘zones’ and residential quarters covering a wide range of incomes. It also stood in the midst of elaborated transportation systems, incorporating terrestrial, maritime and air routes (Figure 5).Footnote 30

Figure 5: Dakar around the 1940s and the 1950s. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

This proposed segregation was realized to a considerable extent, not in the way it was imagined by the urban planners, but instead largely through the agency of intermediary groups in Dakar's colonial society, such as the Lebanese traders. As migration from the town increased from the 1940s onwards, more and more Lebanese traders settled in the vicinity of the Sandaga market, filling in large parts of the nearby former cordon sanitaire with commercial and residential installations. Apart from the obvious attraction of the marketplace, other reasons can also explain the settlement of Lebanese traders in this area. A prominent reason was that out of fear of losing their valuable lands in the city centre due to strict building regulations there, many Lebus living in this area started to rent their lands out to Lebanese traders on condition that the latter would build according to the regulations. This system of land tenure, known as the ‘bail de Tound’, created an unprecedented pressure there, further increasing prices of rent and land ownership.Footnote 31 The colonial authorities, although reluctantly, tolerated the advent of these intermediary groups for economic reasons: they bridged the gap between the big European companies and the African small traders. This particular ‘laissez-fairism’ regarding the appropriation of the former cordon sanitaire only resulted in a further enhancement of the role of nearby Sandaga and the sophistication and variegation of its merchandise. Marché Sandaga thus never lost its paramount position, oriented towards the regional and not only towards the local. This was in spite of the emergence of more Dakaroise markets at this stage – such as Marché Tilène, Colobane, Soumbédioune and HLM.

On the ideological level, the post-World War II urban planning of Léopoldville was the opposite of the situation in Dakar. Although a similar class of évolués existed in Belgian colonial society, this was not translated into urban space.Footnote 32 On the contrary, Léopoldville's first post-World War II master plan was highly racial in nature, injecting new life into the idea of the cordon sanitaire. This plan, officially published in 1951, was designed by the central colonial government in Brussels, and was intended to be implemented locally by Léopoldville's town planning department. The Brussels plan devoted a lot of attention to the monumental restructuring of the European town, proposing a huge neutral zone around the African quarter and separate markets for the European and African community.Footnote 33 In order to transform Léopoldville into a majestic capital city, the so-called ‘Le Grand Léo’, it was argued that massive expropriations would be required, especially for the establishment of the huge neutral zone.Footnote 34 It was exactly because of the many objections to these expropriations by Europeans and Africans that the Brussels plan was not well received at the local level.Footnote 35

While the Brussels plan was rejected by the Comité Urbain, an alternative master plan was made by Léopoldville's town planning department. This plan was no less segregationist. Indeed, it paid little attention to the implementation of the neutral zone and left the existing commercial district and marketplace of Léopoldville untouched, but the city's different racial communities were intended to be housed in self-contained satellite towns, separated by large open spaces.Footnote 36 However, as a result of the ongoing disputes between the metropolitan and local levels of administration, neither of the two master plans was realized. In practice, some elements of both master plans were implemented haphazardly on a modest scale, but without long-term objectives. The consequence was improvised decisions, uncoordinated choices and an overall laissez-faire policy regarding urban planning.

The reason for the breakdown of the neutral zone in this era can therefore be attributed to an internal dispute between the colonial planning organizations. While the existence of a neutral zone between the African and European quarters was estimated to be of high importance by the central government in Brussels, the local administration did not always seem to recognize the need for a neutral zone. The dispute enabled intermediary population groups, mainly tradesmen of Portuguese, Greek and Italian descent, to settle down in the vicinity of the central market, located in the neutral zone. As in Dakar, these intermediary figures in colonial society gradually changed the neutral zone from a separating device within the urban structure into an area of exchange and encounter. Unwilling to damage the economic interests of these tradesmen, because they provided Léopoldville with luxury goods and commodities that would otherwise be unavailable, the Comité Urbain left their massive appropriation largely uninterrupted. Moreover, the increased pressure from real estate agents, and private and public investors in the neutral zone from the beginning of the 1950s onwards, can be considered as another reason for its evaporation.Footnote 37 Such developments, made possible by the inconsistent laissez-faire politics of the colonial administration, transformed Kinshasa into a bustling city, often called ‘Kin-la-belle’.Footnote 38

Marché Sandaga and Marché Central in the post-colonial period

While official colonial rule ended in French sub-Saharan Africa around 1960, France kept strong ties with its former colonies after independence, especially in light of the deepening French-African co-operation. Already by the late 1950s, France introduced substantial political and economic changes in its colonies, including their incorporation in the capitalist world market.Footnote 39 These changes in the late colonial years enabled a smooth decolonization process to take place, while at the same time ensuring a continued French influence in its former colonies within the framework of bilateral development co-operation.Footnote 40 For the Belgians, in contrast, who were confident in the success of their colonial regime in the Congo even by the mid-1950s, decolonization seemed an almost irrelevant option and Africans were not significantly incorporated in the state's institutions. Following extensive riots in Léopoldville in 1959, the decolonization ‘process’ only lasted 18 months.Footnote 41 The consequent breakdown of the state machinery resulted in foreign involvement from an early stage, introducing new foreign actors in the Congo, as opposed to the former French colonies where France generally maintained a monopoly position. After independence, the lasting French presence in the former French colony and the new French presence in the former Belgian colony continued to shape both marketplaces in Dakar and Kinshasa.

Dakar, the capital of Senegal since 1960, experienced large-scale planning and housing projects after independence, with a strong French involvement. The local urban planning department, for example, remained staffed with French personnel for a considerable time; the French architect Michel Ecochard was appointed to draw Dakar's first post-colonial master plan as an external consultant.Footnote 42 The principal (colonial) housing corporation SICAP, and to a lesser extent OHLM, remained largely dependent on French funding up to the 1980s (when multi-lateral donors, such as the World Bank, replaced France).Footnote 43 Apart from a general ‘laissez-fairism’ on the part of the Senegalese government, France's desire for a return on its investment strongly affected the implementation of most of these urban planning and housing projects. For instance, in many post-colonial SICAP quarters, in order to reduce the cost, there was a general neglect of public amenities, such as markets, and in comparison to colonial standards, paradoxically, the SICAP housing after independence was either of low quality or targeted a very limited group of well-off clientele.Footnote 44

Against this background, and in spite of the decentralization of market functions in the overall urban agglomeration – including luxury shopping malls like the new Sea-Plaza commercial centreFootnote 45 and many informal trading networks – Sandaga's role and location is still unchallenged. It specializes in fruits and vegetables, fish, meat, ready meals, fabric and cloth, cosmetics, electronics, artwork and international money transfers; and it is occupied by more than 3,000 traders within the three-storey building and by a few thousand street traders in the vicinityFootnote 46 belonging to a variety of African ethnic groups and nationalities, Middle Easterners and, lately, Chinese. Sandaga's main-axis square, at the junction of Avenue Lamine Gueye and Avenue Emile Badiane, also serves as a space for performance, political riots and protests, and is characterized by a Mourid-Islamic presence. It also constitutes a focus for occasional raids by state and municipal authorities over the ‘illegal’ street trading phenomenon.Footnote 47

While Sandaga's role is unchallenged, the physical state of this edifice (in use since 1934) gives cause for concern (Figure 6).Footnote 48 Considered in the past as ‘a pearl at the very heart of the city’, in the present popular rhetoric it is described as ‘a real catastrophe’, ‘a time bomb’ and the like.Footnote 49 Besides other hazards in its immediate surroundings, such as air pollution, overcrowding, crime, unpleasant odours and the danger of fire because of clandestine electricity and high humidity, the building, listed as an historical monument by the government of Senegal, is dilapidated. Previous attempts to evacuate the building in order to enable renovation and conservation, such as the 2006 decree, were obstructed by its occupiers, demonstrating the social sensitivity such operations require. Even though a possible transfer to an alternative site, whether permanent or not, is being considered by both state and city authorities,Footnote 50 this mission is not only complex to realize because of the costs involved, but also controversial because of the symbolic value of the building as a lieu de mémoire within the urban fabric of Dakar's urban space.

Figure 6: Sandaga Market today. Photo by Liora Bigon.

As to post-colonial Kinshasa, while the Belgians continued to make their presence felt, they were chiefly replaced by new foreign actors. As regards urban planning, France, eager to expand its West African experience to the French-speaking Congo-Kinshasa, would take a leading role. In 1964, at the request of the Congolese government, a French urban planning mission (MFU) arrived in Kinshasa.Footnote 51 Apart from a massive eastern extension of the city, the so-called ‘Ville Est’, the MFU proposed erecting a new city centre as the former colonial administrative and commercial district had become peripheral to the majority of people due to the rapid urbanization the city had experienced since World War II. A ‘Futur Centre Ville’ was thus planned more to the contemporary geographical centre of the city and next to the area regarded as the heart of Kinshasa.Footnote 52 As a consequence, the market's location was again challenged, as the MFU wanted to decrease its dominant character, and with this solve the congestion in its environs by promoting the new ambitious city centre. The latter was considered appropriate for an international city as Kinshasa, at that time the most populous city of sub-Saharan Africa after Lagos.Footnote 53

Nevertheless, before the MFU even started thinking about the implementation of its master plan, published in 1967, the growth of the city meant that it was already outdated and the plan was abandoned in 1969. In addition, the master plan seemed largely unaffordable for a developing country and no legal or institutional framework for its implementation existed. Though a second master plan was proposed in 1975 by the same MFU, now supported by a team of French geographers, sociologists and anthropologists,Footnote 54 it equally failed to respond to the needs of the daily consumer of the city, the average Kinois. As a consequence, the urbanization process of Kinshasa after independence took place in the total absence of urban planning and through the extensive appropriation of space by the inhabitants of Kinshasa. While the MFU, as in Dakar and in accordance with the French tradition, primarily showed interest in the building of prestigious projects and heavy infrastructure that guaranteed a considerable economic return, Mobutu's government only showed interest in urban interventions that served its own personal and populist agenda.Footnote 55

This situation is well exemplified by the new, modernist looking market building, erected between 1969 and 1971 on the site of the original Marché Public in the former neutral zone (Figure 7).Footnote 56 By the establishment of this new market building, President Mobutu wanted to enhance his popularity and represent his power in built form. Although this project stood in contradiction to the MFU's plan, which sought to decrease the dominant character of the existing market building in favour of the newly proposed city centre, the MFU contributed to its cost.Footnote 57 The market building, which was designed as a grouping of several concrete shell-shaped pavilions, had initially been intended to accommodate 3,500 traders. Only three years after the new market building had been completed, the numbers of traders had already doubled the number of places. Although most Greek, Portuguese and Italian tradesmen left the country after the zaïrianization ruined their businesses, they were quickly replaced by merchants from the Middle East and Asia who started to occupy the marketplace and especially the shops in its immediate surroundings.Footnote 58 In the following years, under the pressure of the informal economy and the real estate business, large parts of the adjacent Parc De Bock were converted into retail businesses, often with the silent approval of government employees (Figures 7 and 8). In 1985, the marketplace accommodated more than 10,000 merchants, of whom the majority was women, a new phenomenon for Kinshasa at that time.Footnote 59

Figure 7: Kinshasa around the 1970s and the 1980s with a focus on the central marketplace. Map made by Luce Beeckmans.

Figure 8: Kinshasa's Central Market today. Photo by Luce Beeckmans.

In contrast to the MFU's plan and objectives, the central market of Kinshasa never lost its dominant role as a major distribution centre of goods in the city, and even in the country. As the city continued to expand into the periphery, the position of the marketplace became increasingly problematic, and the flow of persons and goods completely overcrowded the few available roads to the market, causing long traffic jams in the direction of the city centre. In addition, due to the total collapse of public services and administration in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the congestion in the marketplace and the surrounding commercial district resulted in a serious degradation of the market infrastructure. Today, the roofs of the market building are being appropriated by gangs of street children, who live from doing small jobs for market traders and finding remnants of food at the market.Footnote 60 Only recently, the pressure on the city centre was further augmented through the construction of stores on the marketplace by today's omnipresent Lebanese real estate agents. The air pollution in the vicinity of the marketplace, the absence of garbage services and sewer and drainage systems has resulted in inhabitants nicknaming the city ‘Kin-la-poubelle’, referring to the modern and sanitary ‘Kin-la-belle’ that is missed and detested at the same time.Footnote 61

Conclusion

As significant places in both cities, Marché Sandaga and Marché Central have never lost their paramount role in Dakar and Kinshasa respectively. Representing a micro-cosmos, each marketplace, in a very condensed way, mirrored the changes taking place in the city at large. Our mapping of the many trajectories through time and place of these public institutions reveals much about the origins and cultural, social and political forces that shaped the city. Expanding on the gaps between (post-)colonial plans and their implementation, it has been shown that there are a variety of reasons for the tension between planning ideas and the actually realized urban landscape. It was argued that the gap between planning and implementation was to some extent linked to the agency of local actors. While the participation of local actors in the urban planning processes was indeed rare throughout the century, local actors have, to a certain degree, been able to divert urban planning proposals by hindering their implementation, (re)appropriating urban spaces or simply by remaining inactive. As a result, the agency of city dwellers ranged from active to passive resistance and was as much the result of daily patterns of use as of co-ordinated movements of resistance.

The essentially spatial perspective that characterizes this study focused on the (anti-)planning consequences of both markets in question, distinguishes this article from the other contributions to this issue. The latter deal with the urban history of the public market model from socio-political and economic perspectives – such as retail and wholesale, consumption and management. Even if one of the contributions lightly touches on material culture and performative aspects (see Kelley's article on London's street markets), these issues still relate to the market as an economic institution and site of exchange, rather than to the built fabric itself and its planning. In line with one of the key themes in this issue identified by Stobart and Van Damme, this comparative study of both marketplaces through history can be considered as a relevant exercise in ‘provincializing’ the modern. It reconstructs the intricate processes of (post-)colonial spatial production in Africa by focusing on their physicality.