Introduction

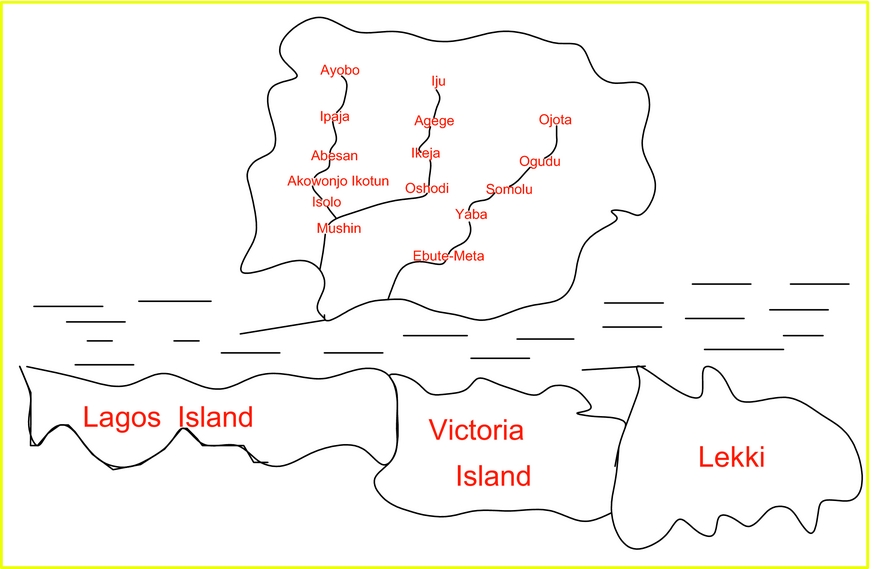

The article discusses gentrification in Lagos between 1929 and 1990 within the context of the colonial government's policies on town planning and segregation. The year 1929 is chosen as the starting date against the backdrop of the current scholarly argument that gentrification is largely a post-World War II phenomenon.Footnote 1 The evidence provided by Lagos does not endorse this approach. I also extend the discussion of gentrification until 1990 to show that post-colonial Lagos, as the capital of Nigeria until 1990, inherited the legacy of underdeveloped physical planning by the colonial government in its urban renewal programme.Footnote 2 The article covers Lagos Island, Victoria Island, Lekki, Ebute-Meta, Yaba and Ikeja Division under which were areas like Ikeja, Mushin, Isolo and Oshodi among others. These areas formed metropolitan Lagos in the period under study (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map showing the area of study

Since the appearance of Ruth Glass’ work on gentrification in 1964, there have been many debates on theories of the economic and social pre-conditions of gentrification and the empirical evidence of what should be regarded as constituting a gentrifying neighbourhood.Footnote 3 Gentrification is defined as the rehabilitation of working-class and derelict housing and the consequent transformation of an area into a middle-class neighbourhood.Footnote 4 Some scholars have argued that capitalism is based precisely on its ability to displace the working class in various situations, and history has shown us many examples of the ways in which legislators, the wealthy and the politically influential have managed to move the poor when it was profitable or expedient to do so.Footnote 5 Whether at the level of individuals, family, household or community, opportunities and preferences with respect to housing consumption are ‘socially structured by finance capital and state intervention’. Well-educated professional single women or women who are part of a dual income marriage are also seen as conspicuous participants in the gentrification process.Footnote 6 It is also argued that a number of key factors contribute to gentrifying processes, most notably the growth of new industrial and service sectors and the emergence of a new and homogeneous middle class.Footnote 7 Chris Hamnett has argued that each of the two major explanations for gentrification (the rent gap and the production of gentrifiers) are partial explanations, each of which is necessary but not sufficient.Footnote 8 Gentrification is not merely seen as the invasion of inner-city areas by ‘yuppies’, but instead is a far more complex and ‘chaotic’ concept.Footnote 9

There has been a concern with debating and theorizing the overarching causes, and how the generalities of gentrification are translated in contingent ways at an empirical level.Footnote 10 Daren Smith examines the relationships between higher education students and physical urban change. The degree to which gentrification is observed and its possible future trajectory might be linked to the existence of large numbers of students in the urban area.Footnote 11 This view is expanded by Daren Smith and Louise Holt when they consider in more detail the connections between studentification and gentrification.Footnote 12 They have noted how the desire to keep abreast of new conditions and expressions of gentrification has welded a well-defined group of researchers, despite competing and opposed standpoints.Footnote 13

Scholars of gentrification literature continue to abstract the unobservable forces of gentrification from the increasingly diverse observable phenomena within the material world.Footnote 14 The Hausmannization of Paris was seen by some as part of this process. It has, however, been shown that the rebuilding of Paris between 1850 and 1870 was an attempt to rationalize urban space by Emperor Napoleon III and his prefet de la Seine, Baron Georges Hausmann.Footnote 15 The reconstruction of the Second Empire of Paris was to correct the evils caused by long neglect of the past.Footnote 16 After the annexation of Lagos, the British administrator of the colony cleared ‘the beach of native tenements. . .and constructed wide streets for the sea breeze to blow through’. This brought about large-scale dispossession of land, destruction of property and a change in values in Lagos. It forced the indigenes to settle towards the north-western part of the Island and set the pattern for the British replanning of Lagos Island.Footnote 17 The growth of Lagos challenged many of the previously held assumptions about economic prosperity and demographic change as exemplified by nineteenth-century Europe and North America.Footnote 18

The geographical spread of gentrification is reminiscent of earlier waves of colonial and mercantile expansion which were predicated on gaps in economic development at the national scale and have moved into the countries and cities of the global south.Footnote 19 Indeed, the Anglo-American geo-space has provided a useful nursery for the nurture and development of gentrification literature, debates and theories. This has prompted Thomas Maloutas to raise the issue of contextual attachment of gentrification to the Anglo-American arena.Footnote 20 To what extent can we then say that gentrification is a global phenomenon with diverse causes and characteristics?

Gentrification is usually conceived of, especially in the developed world, as an activity that is typically the result of investment in a community by local government, community activists or business groups, and can often spur economic development, attract business and lower the crime rate.Footnote 21 Landlords, developers and banks all play key roles. Most of these studies fail to consider the colonial situation where colonial government policies created in most cases unintended consequences, one of which was gentrification. Approaches such as demographic-ecological, socio-cultural, political-economical, community networks and social movements canvassed by Bruce London and John Palen dwell extensively on socio-political situations in the developed world at the expense of the colonial factor.Footnote 22 The attempt by E.B.A. Agbaje to apply these approaches to Nigerian cities (Lagos included) is not only inappropriate but also unsuccessful.Footnote 23 Not even the production-side theory of Neil Smith, or the consumption-side theory of David Ley adequately capture the essence of colonial Lagos.Footnote 24 Again, the various stages of gentrification together with the factors shaping them do not explain the Lagos experience.Footnote 25 Thus, the present article aims at bridging the gap in extant studies by focusing on some colonial urban policies in Lagos, while drawing attention to some aspects of the problems imposed on colonial Lagos, which have subsequently become permanent features of post-colonial Lagos.

Town planning

Broadly speaking, town planning as a policy deals with the wholesome growth of a town as a whole by allocating specific sections of a town to particular needs and specifying suitable building regulations and the limitations of buildings per acre.Footnote 26 However, town planning as discussed in this article will be limited to the replanning policy of reclamation, slum clearing and rehousing. The first ever attempt at urban planning in colonial Lagos dates back to 1863, when the colonial government promulgated the Town Improvement Ordinance.Footnote 27

There were other attempts at urban development such as the Swamp Improvement Act of 1877; General Sanitary Board (1899); Native Authority Ordinance (1901); Lagos Municipal Health Board (1908); and Lagos Township Ordinance of 1917, among others. The details of these regulations have been discussed elsewhere.Footnote 28 Suffice it to say that the Lagos Township Ordinance promulgated by Lord Lugard created the Lagos Town Council of 1917 to tackle the overcrowded and insanitary conditions of the Township and Urban District of Lagos. Addressing the issues of overcrowding and insanitary conditions meant decongesting part of the island and resettling the people in less populated areas. The only area open to such settlement on Lagos Island was Ikoyi which had been expropriated for European settlement. Thus, people lived in uninhabitable areas like Elegbata, Alakoro, Anikantamo, Oko-Awo and Sangrouse on Lagos Island (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of Lagos Island showing overcrowded and insanitary areas

The floors of buildings in these areas were constantly damp, and during the rainy season, the yards and outhouses were mostly under water.Footnote 29 The fact that these areas were reclaimed without allowing for enough sedimentation before structures were imposed on them did not help matters. Living under such circumstances brought several health problems like tuberculosis and other lung-related diseases. The worst health problem came in 1924 when there was an outbreak of bubonic plague which started at Oko-Awo.Footnote 30

The government immediately acquired 700 acres of land at Yaba in order to relieve the serious congestion on the Island of Lagos.Footnote 31 Sir Hugh Clifford, the governor of Lagos, had recommended in 1924 that, in order to attract people to Yaba, freehold title should be given to anyone prepared to purchase sites and erect approved houses on them. The secretary of state, however, objected to this in 1925. According to him, unless experience proved otherwise, leasehold should be encouraged.Footnote 32 Therefore, a government policy which insisted on the leasehold of plot at the Yaba Housing Estate made it impossible to dispose of the plots of land in Yaba in spite of the infrastructure put in place.Footnote 33 Meanwhile, the terrible condition continued and the plague ravaged the area until the 1930s. Consequently, the colonial government decided on a comprehensive replanning of Lagos with the enactment of the Lagos Town Planning Ordinance of 1927. The duty of carrying out the provisions of the ordinance was vested in an Executive Development Board which became operational in 1928.

The ordinance that established the Lagos Executive Development Board (LEDB) was intended to make provision for the replanning, improvement and development of Lagos.Footnote 34 A major thrust of the LEDB's programme of replanning the city of Lagos was slum clearing, which involved the demolition of several buildings. Houses which the colonial government regarded as ‘dangerous structures’ and ‘decided plague foci’ were pulled down. By the end of 1933, 400 houses and shacks had been demolished. The demolition continued through the 1950s when a vigorous slum clearing programme was undertaken under various town planning schemes.Footnote 35 The Yaba housing scheme had been initiated in order to solve the housing problem on the island consequent upon the outbreak of plague. In order to attract people to Yaba, it was designed in such a way that several infrastructure facilities were put in place.Footnote 36 The logic behind making Yaba a model residential area was to abate the nuisance of insanitary dwelling on Lagos Island by providing the people with an alternative way of living. However, people refused to take up residence in Yaba for the simple reason that the government wanted plots in Yaba disposed through leasehold. The colonial government had vacillated between individual ownership and communal ownership in their land policies. Since communal ownership gave the colonial government substantial power in land matters, the government insisted on a leasehold of ninety-nine years which retained the right of government in any sale of land within the colony of Lagos. Individual rights did not confer on the colonial government the rights to use land as it desired. The chiefs’ rights in customary land tenure were synonymous with the state's rights to grant or allocate land.

To the typical African man, however, land was something that his children and generations yet unborn should inherit. This was something the colonial government of Lagos failed to understand. Thus, between 1924 and November 1928, no single plot had been taken up in Yaba, in spite of the huge investment of over ₤250,000 by government.Footnote 37 Moreover, by the time the Yaba scheme was initiated, a number of people had taken up freehold plots and built houses at Surulere and Oju-Elegba on the west of the railway line near Yaba.Footnote 38 So, the possibility of purchasing freehold land at Surulere and Oju-Elegba from private land owners rendered the Yaba Housing Scheme unfeasible ab initio. Therefore, it is not entirely correct to say that Lagosians were encouraged to leave the island for the mainland as a result of the construction of a new and wider Carter Bridge in 1931.Footnote 39 By the middle of the 1920s, people had taken up residence in suburbs like Surulere, Oju-Elegba and Mushin among others.Footnote 40 Most of these people worked or had businesses in Lagos. Again, these villages (Surulere and Oju-Elegba) were more difficult to access than Yaba. Tunde Agbola has shown how the land acquisition process in Nigerian cities has contributed to the chaotic pattern of urban development where the adjoining villages have fused with the main city resulting in the creation of suburban slums lacking the facilities and infrastructure necessary for decent city living.Footnote 41

The colonial government later realized the futility of its action and reversed its leasehold policy. Thereafter, development on the estate proceeded so rapidly that by the end of 1932, 174 houses had been completed and 177 were under construction. The rise in the demand for Yaba plots continued after this date so that by the end of 1952, the Land Department had difficulty coping with the avalanche of requests (over 1,600 applicants) for the allocation of the remaining 32 plots of land.Footnote 42

Furthermore, the LEDB undertook major development and slum clearance within the municipality of Lagos. It concerned itself with slum clearance on Lagos Island, the reclamation of Victoria Island, Surulere, south-west Ikoyi, the Apapa housing scheme and the industrial layouts of Apapa, Iganmu and Ijora.Footnote 43 The Lagos central planning scheme of 1951 ensured the clearing and redevelopment of 20 acres of slum dwelling for the people who had been displaced from the various planning schemes of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, who were then to be relocated at Surulere. In a similar manner, Haussmann was responsible for reconstructing Paris following the cholera epidemic of 1832–35 and 1848–49.Footnote 44 Sutcliffe has shown three main phases: of urban planning and laying out of streets (1850–85); of building and housing (1885–1914); and of the preservation of the historical heritage of Paris (after 1914) in the urban renewal efforts.Footnote 45

The mass and indiscriminate demolition of houses did not, however, go down well with the people of Lagos who protested against the LEDB's demolition exercise. The Eleko of Lagos, Oba Sanusi Olusi and his chiefs petitioned the colonial government in 1930 about the ‘rampant demolition of houses under the pretence of anti-plague measures which had rendered many souls homeless’. They pleaded that ‘some margin should be given to that class of old people who are happy in their homes’. The tense political climate of the period did not help the slum clearance programme. There was a press war which peaked in the 1950s.Footnote 46 It should be noted that some of those displaced in downtown Lagos had earlier been resettled at Obalende in 1929, which gave the area its name – Obalende (the king drove me here).

By 1955, 913 dwellings had been provided at Surulere and all had been occupied by 1962.Footnote 47 The displaced population could not be accommodated at the original location.Footnote 48 The tenants, who occupied various rented apartments all over Lagos and who constituted a large percentage of the population, were inevitably evicted. Again, reclaimed land cost more than the total compensation paid to owners of buildings. Hence, the greater majority of the people were displaced. Even when they wanted to buy plots in the newly reclaimed area, the plots were smaller than their former plots.Footnote 49According to the initial plan, the LEDB was supposed to purchase the designated area, redevelop it and then redistribute its plots. The plots were to be sold back to their original owners at 120 per cent of the acquisition cost, and the owners were expected to rebuild their homes in accordance with modern building standards. However, most of them could not raise the money, including the additional 20 per cent. Neither did they have sufficient funds to modernize their premises. Moreover, the extended family could rarely come to an agreement concerning the repurchase of the property.Footnote 50 Consequently, the LEDB decided in 1958 to initiate a new scheme for persons affected by the slum clearance, and to resettle them on the easternmost area of Lagos Island after its reclamation. Yet this area was soon confiscated by the Federal government and the plots in the area were allocated directly to government administrators. In return, temporary shops were allocated to the members of the evicted community in the slum clearance district itself. Also, local traders who were not affected by the clearance scheme but who had some connection with government officials had shops allocated to them in the area.Footnote 51

Furthermore, those who managed to reacquire their land in most cases were too poor to erect approved structures on their plots and so had to lease the land to rich property speculators in the vibrant land market of Lagos. These constraints aggravated housing and land use problems in Lagos. Many people were forced out of Lagos Island. Rent differentials brought about by land prices forced people on low incomes to move to the suburbs of Lagos in the nearby villages and other non-urban settlements.Footnote 52

The industrial development that took place in Lagos after 1950 resulted in an unprecedented rate of growth and the spatial expansion of the continuously built-up area beyond the legal confines of the municipality. Within the municipal boundary itself, the population rose from 230,256 in 1950 to over 650,000 in 1963.Footnote 53 As the population increased, the demand for housing and land also increased. The gradual absorption of the villages into the metropolis meant a rapid loss of agricultural land. Besides, much of the private housing development was virtually uncontrolled and unplanned and often illegal, with dire consequences for the environment.

In addition, the government's rehousing scheme at Yaba and Surulere did not produce the desired result. If anything, it compounded the problem of housing. Several people could not afford the rent in these areas and so moved inland in all directions – Ojota/Ketu axis (north-east); Abule-Egba/Sango axis (north); Amuwo-Odofin/Ojo axis (north-west); and Lekki, especially, Maroko and Ilado villages (south-east) among others. All these were areas outside the municipality of Lagos. The unregulated pattern of development was replicated everywhere (Figure 3). By the early 1970s, the whole of Lagos faced an alarmingly high rent as a result of the housing scarcity occasioned by demographic pressure. This reached its peak in 1974, when the Lagos government under Mobolaji Johnson promulgated a rent edictFootnote 54 in order to force down rent. This, however, did not achieve the desired result as rent kept going up, the main reason being that the government did not own its own housing units. The government was interested in making the environment clean and free of disease. This explains the type of housing units (blocks of flats) both the Lagos and Federal governments later put in place in Lagos.Footnote 55 Blocks of flats ensured higher rents. However, the demand for accommodation at this time outstripped any consideration of quality. There was no movement from lower residential houses to middle ones so as to create vacancies.

Figure 3: Map showing urban sprawl in all directions

This situation forced the government of Lateef Jakande to be directly involved in the provision of housing in areas like Isolo, Abesan, Amuwo-Odofin, Oko-Oba, Akowonjo, Iponrin and Ebute-Elefun among others. Apart from Ebute-Elefun, Isolo and Iponri, the rest were in the suburbs outside the municipality of Lagos. Although the direct involvement of government in housing went a long way towards showing how land and space could be judiciously used, as houses consisted of two-storey buildings of six flats each and so relieved residents of undue competition for land, it merely succeeded in stabilizing rent in the interim. First, the absence of housing data made it possible for those who were already house owners to buy the housing units which they sub-let to tenants at exorbitant prices. Second, the Lagos government continued with the slum clearance programme which led to the displacement of more people. For example, the government of Colonel Raji Rasaki in 1990 brought about the demolition of Maroko, Ilado, Gedegede, Obalensoro, Moba and a host of others in the name of ‘slum clearance and illegal squatters’. However, no sooner had these areas been cleared than they were allocated to people on high incomes who could afford to pay the exorbitant land prices. This action further compounded the problems of other areas in the suburbs of Lagos, such as Iju, Agbado, Ikotun, Egbe, Idimu, Ejigbo, Iba, Ijegun, Ipaja and Ayobo among others.Footnote 56 Lindsay Sawyer rightly observed that the construction of roads, which was due to the political clout and organization of some residents, often followed developments in some of the peripheral areas.Footnote 57

On the whole, the urban policy of replanning had wider implications for colonial and post-colonial Lagos. First, the slum clearing exercises carried out as part of the replanning programme of government in the 1920s until 1990 were not implemented with sincerity of purpose. Urban renewal measures were often carried out in colonial cities with less regard for their social impact than would have been possible in Britain at the time.Footnote 58 The British colonial administrators frustrated attempts by Nigerians to improve municipal government in their towns. Also, Lugard's dual system of native authority and townships hindered the emergence of a responsible urban government.Footnote 59 It was not intended that all the evacuees would go back to their original abode.

Thus, the colonial government sowed the seed of gentrification, which resulted in serious urban problems; slum dwelling, unregulated development, sanitation problems, squalor and overcrowding, especially in the suburbs of metropolitan Lagos. In all the areas where demolition exercises had occurred, new buildings which ‘conformed’ to the regulations of town planning schemes were erected; land value and rents increased; and more importantly, original occupants were dispossessed.Footnote 60 The result was the emergence of shanties in the suburbs including Lekki and even on Lagos Island in the swampy areas and along the foreshore of the lagoonFootnote 61 at places like Ije, Ilubinrin, Isale-Eko, Maroko (Lagos Island), Makoko, Bariga and Ajeromi (mainland) among others. This pattern of development later became a prominent feature of urban blight and sprawl from the 1950s until the twenty-first century. This process gave Lagos its present mega city status as more and more people moved in and expanded the metropolitan area.

Second, the movement of people out of the island after the plague that ravaged the island in 1924 did not stop the characteristic haphazard pattern of township development. Apart from Yaba Housing Estate that was planned from the beginning, other areas on the mainland like Oju-Elegba, Surulere, Mushin, Ojuwoye, Onigbongbo, Ajeromi, Oshodi, Agege and Maroko, and Ilado villages among others in Lekki, were not planned before people drifted into them. As a result, the same pattern of unregulated development was replicated in other areas of Greater Lagos. Houses and structures were erected in a haphazard manner with no regard for roads, drainage or even sewage.

The colonial government had extended the urban area of Lagos to include several suburbs inland. Thus, the municipal area was extended one mile north of Agege in order to abate the nuisance of insanitary conditions and unregulated development.Footnote 62 The entire area was initially placed under the jurisdiction of the Lagos Town Council until the Ikeja District Council was established in 1927. This however, had little effect on regulating the development of suburban Lagos. First, unregulated colonial land policies encouraged unregulated development. Second, the new council was too extensive for easy administration and control. Third, the colonial government did not have the necessary hands to administer and enforce town planning laws and regulations. Thus, the concern of the colonial government to correlate the planning of neighbouring suburban areas with slum clearance on Lagos Island, so that those displaced by the replanning scheme would not transfer the same condition to those areas, was frustrated.

Third, the reclamation exercise carried out by the colonial and post-colonial governments of Lagos was not well co-ordinated. Admittedly, the government filled some areas with sand dredged from the harbour. In low-lying areas where the government encountered the problem of inadequate reclamation, it gave its tacit approval to the unscientific and unhealthy practice of using refuse to reclaim swamps. This merely turned many low-lying areas into refuse dumps and breeding grounds for disease. In addition, technical opinion in colonial Lagos was that swamp land reclamation might not, in some cases, be suitable for building until 15 years after the completion of reclamation.Footnote 63 The history of reclamation in the period under study suggests that the Lagos government did not adhere too strictly to this. Reclaimed areas were occupied as soon as they were reclaimed by whatever means. The government tolerated such practices with dire consequences for post-colonial Lagos. The incidence of collapsed buildings has been high in these areas (Idumagbo, Idunsagbe, Isale Agbede and Princess Street) of Lagos Island from the 1980s, until the twenty-first century.Footnote 64

Fourth, the rehousing scheme in an area like Surulere was ill conceived. It brought about an increase in the budget of those who were lucky enough to secure rooms in Surulere. Those whose children were schooled in Lagos were compelled to spend additional money on transport or board their children in hostels in Lagos. Evictees whose offices or businesses were in Lagos also experienced inconvenience. Thus, it was reported by the West African Pilot that

In Surulere, many people live as far as two miles from the nearest bus stop. The same is true of those living at Abule Ijesha, and other areas in the outskirts of Lagos. Even those who live in Yaba and Ebute-Meta have to wait for almost two hours in the morning before they get bus to take them to the island. As a result of this delay, several workers have become habitual late comers. . .The Lagos Town Council's . . . is partially responsible.Footnote 65

Indeed, it has been argued that ‘town planning suffered from the uneasy central-local relations in colonial Lagos, and unlike in Britain, was never adequately integrated into local government’. Colonial officials in Lagos and Nigeria generally resented town planners as the interfering agents of the central authority and were not interested in promoting responsible urban government, which might involve changing the indirect rule system at the expense of the traditional chiefs.Footnote 66 Moreover, they were interested in reducing public expenditure on municipal planning to the barest minimum.Footnote 67 A town planning officer was not appointed for Nigeria until 1928, 14 years after the creation of the town planning institute in Britain,Footnote 68 which probably explains why Maxwell Fry was surprised to meet a town planning officer who was doing anything but town planning in Lagos in the mid-1940s.Footnote 69

The replanning policy seemed to have created two societies in colonial Lagos, as slum dwelling became formal and distinct from better planned areas of Lagos. The unplanned areas were characterized by a grid-iron pattern of urban land development and covered by unregulated buildings and narrow streets. The planned areas were characterized by buildings set back from the road with tree-lined avenues and long straight roads. Again, the post-colonial governments of Lagos seemed to have endorsed urban blight as a way of living and created more such neglected areas with their ill-digested policies. People in these areas were wary and suspicious of outsiders who were usually thought to be government agents or spies. Their alienation could take the form of hostility to outsiders including law enforcement agents.

Segregation

Colonial urban policy in Lagos also involved segregation. The concern for land use and environmental sanitation between 1863 and 1899 derived from attempts to protect the Europeans from health hazards.Footnote 70 Thus, the colonial government of Lagos fashioned a strategy for residential segregation. Urban segregation has ancient roots in Africa.Footnote 71 In the nineteenth century, the British drew on their Indian experience while the French drew on their experience in North Africa.Footnote 72 Phillip Curtin identified the connection between the knowledge of tropical diseases (particularly malaria) and the emergence of town planning in the cities of tropical Africa.Footnote 73 The British desire to reduce the number of deaths among the British troops stationed as a safeguard against a recurrence of the Indian mutiny had necessitated the maintenance of a sufficient distance between military cantonments and large concentrations of Indians.Footnote 74 This influenced the malaria germ theory that was later applied to create the sanitation syndrome in West Africa. The anti-plague measures that were implemented in the colonies also influenced segregation as a policy. The situation in Lagos was no different in contemporary colonies; some Europeans observed in Shanghai in the 1850s that ‘pigs and dogs are the only sanitary officers in China’ where public health systems were unknown.Footnote 75

The capitalist ideology of colonial urban space dictated that public expenditure be kept to the barest minimum, and that included municipal planning and administration.Footnote 76 Fiscal priorities inhibited the implementation of public sanitation, and indeed public works in general, until severe outbreaks of infectious diseases proved such economy to be dangerous.Footnote 77 However, J.W. Cell has argued that even though the practice of segregation is an old one, the doctrine of segregation came into vogue only at the end of the nineteenth century as ‘segregation was associated not with reactionary attitudes inherited from slavery or the frontier, but with phenomena ordinarily regarded as progressive: cities, factories, sophisticated communications, modern political systems’. Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch has noted that urban planning for Africans began in South Africa about half a century before it was developed elsewhere. The success of South Africa greatly influenced African colonial urbanism in both British and French colonies. Apartheid policy ensured downtown black and mixed districts were systematically destroyed despite their strong urban culture.Footnote 78 Many parts of South Africa, including Sophia town in Johannesburg, District Six in Cape Town and Cato Manor in Durban, practised forms of segregation in the nineteenth century and generated racism.Footnote 79

The development of a Cape Town ideology and the practice of racial segregation, as distinct from ‘traditional’ class-based forms of white exclusivity, were informed by the contemporary ad hoc development of segregatory practices in other parts of the Cape and beyond, especially in Natal and the American South. It was also influenced by Bond politicians who had seen responsible government as a means of using state resources like education to benefit Afrikaners.Footnote 80 According to Susan Parnell, even though the Native Urban Area Act of 1923 represented a new urban African policy, it carried over many of the pre-First World War traditions.Footnote 81 One such tradition was the exemption of ‘civilised Natives’ from segregated municipal locations. Exemptions granted to African men, however, did not extend to their wives and children who after 1924 had to live in the townships. The worker's labour was wanted in the colonies but not his relatives and dependants.Footnote 82 Thus, after initial imposition of thoroughgoing ‘medical’ racial segregation at Hill Station, Sierra Leone, within a year, two resident domestic servants were allowed for each colonial officer.Footnote 83 The policy was not so much about how native inhabitants could be freed from the dangers of the Anopheles, but how the comparatively small number of Europeans in the colonies could be protected from a health hazard. The argument that racial segregation was a method of prophylaxis has been described as being ‘at best dubious and at worst ethically indefensible’.

Urban segregation in India, South Africa and the United States revealed different dimensions. In India, the policy was much more about imperial power and the health and comfort of Europeans than it was about control over private housing markets. In South Africa, urban segregation/apartheid supported the country's migrant labour system and ultimately its police state as well as its divided property markets. Residential segregation in the United States by contrast was overwhelmingly focused on the goal of sustaining white control over urban property, especially housing.Footnote 84

Residential segregation of Europeans and Africans in colonial Lagos, as an urban policy, was therefore part of this institutionalized racism. The British policies of urban planning and public health programmes necessitated the introduction of residential segregation in colonial Lagos. This prepared the ground for the Township Ordinance of 1917, which apart from categorizing urban centres in Nigeria into first, second and third class townships also made segregation compulsory. For the first time in the history of town planning in Nigeria, the ordinance introduced zoning and sub-division regulation into planning practice. The colonial government created European residential areas at Ikoyi, Apapa, Ijora and to a lesser extent at Ikeja and Victoria Beach. Victoria Beach was developed in the 1950s primarily for people on high incomes whose residence at Victoria Beach segregated them from people on low incomes at Maroko and other such slums.Footnote 85 Ikoyi was strictly for the European officials and non-officials. Medical scientific knowledge of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries suggested that the ‘indigenous African was a repository of malaria and that the most feasible way to prevent malaria among Europeans was to segregate Europeans from natives’. Hence, only their African domestic servants were in principle allowed to live in their own quarters on the premises. In the Ikoyi leases, there was a standard proviso that ‘there shall be no sub-letting to non-Europeans, and there is a similar clause in an Apapa lease’. Residential segregation as an official policy was resented by educated Lagosians. The upsurge in nationalist activities made the colonial government reconsider the policy, so that by March 1950, the commissioner of Lagos Colony approved the first African application for a lease to a Mr Wynter-Shacklefield.Footnote 86

However, the acquisition of Ikoyi and other such areas for European residence had serious implications for Lagos. The legal implications of such acquisition were manifest in the famous case of Amodu Tijani. The case has been well documented. Suffice it to say that in November 1913, the government proposed to acquire portions of land which were the property of the Apapa community represented by Amodu Tijani, an Idejo chief who claimed compensation as the owner of the area. The case dragged on for years, but eventually Amodu Tijani won at the privy council. In addition, the acquisition of Ikoyi and Victoria Beach brought about the displacement of many people. Several villagers were forced to vacate their villages at both places for residencies at Eti-Osa, where they later lost their separate identities in an over-bloated Maroko.Footnote 87 Villages like Oroke, Ilabere, Apese and Magbon were transplanted into Maroko by the colonial government from their long held locations at both Ikoyi and Victoria Beach, in accordance with the law on residential segregation. The villagers resettled at Orile-Maroko and Ilado villages. The population pressure on Maroko engendered by the displacement of such people was increased because of the domestic servants of the Europeans living in the reservation. They lived in Maroko together with their wives and children because of its proximity to both Ikoyi and Victoria Beach.Footnote 88 With few exceptions, the Europeans refused to allow their domestic servants to reside on their premises together with their families in accordance with the segregation clause that established the Ikoyi leases. Thus, the population of Maroko increased overnight; dwellings were hurriedly and haphazardly erected to cater for the continuous influx of people; and Maroko became one big slum overlooking two of the best planned areas of Lagos – Ikoyi and Victoria Beach.

Several non-Europeans who applied for leases at Ikoyi were turned down on one excuse or another.Footnote 89 By 1949, the segregation law of the colonial government was replaced with a new one which specified the maximum number of people that could occupy a residence in the new leases of plots at Ikoyi.Footnote 90 These criteria later determined, in the post-colonial period, who resided in Ikoyi, Victoria Beach (Island), Ikeja and Apapa, as the policy of racial segregation changed to one of class segregation. The post-colonial governments of Lagos have since the 1980s made more of such areas available to the newly rich. For example, Ogudu GRA, Dolphin Estate and Maroko (Lekki Phase I), among others, were acquired to accommodate more people on high incomes. The result of segregation in both the colonial and post-colonial periods is the creation of two different communities in Lagos – a well-planned community with all the basic infrastructure befitting an urban area; and an unplanned community that was completely neglected and lacked the basic amenities of an urban centre.

Conclusion

The article has shown that some of the policies formulated by the colonial government brought about the disruption of the Lagos community. The replanning policies of reclamation, slum clearing and rehousing did not produce the desired result. The rehousing policy which produced the Yaba housing scheme suffered from administrative deficiency. The government's preference for leasehold at the time the Yaba Housing Estate was established produced the unintended result of expanding the frontiers of poor and unhealthy residential areas in the suburbs of Lagos, inhabited by the poor and people on low incomes. At Surulere, the rehousing scheme compounded the problem for those for whom the scheme was meant to provide succour. Several people displaced on Lagos Island could not afford the rent and so moved inland in all directions. As they moved into the periphery of the municipality of Lagos, they replicated everywhere the unregulated pattern of development that the colonial government of Lagos wanted to abate. Instead of rehousing, the colonial government should have settled for a resettlement scheme which would take care of all the displaced people by providing the infrastructure amenities they needed before they moved in.

The variegated land policies in colonial Lagos also created confusion in urban Lagos. At the beginning of colonialism in Lagos in 1861, the colonial government supported individual ownership and people in Lagos sold and bought land as they desired. By 1914, the government switched to the policy of communal ownership and Lagosians simply moved to areas outside the municipality of Lagos where they could deal privately in land with all the attendant problems.

Thus, in contradiction to the arguments of some scholars who have tried to explain or generalize the causes of gentrification in the developed world, gentrification resulted mainly in colonial Lagos from unintended colonial policies which kept pushing those on low incomes to the suburbs of Lagos, while at the same time expanding the frontiers of metropolitan Lagos at the expense of meaningful or qualitative infrastructure development in the suburbs. Again, unlike the process of gentrification in some Anglo-American cities, where the upper and middle classes were fleeing from the working-class residents to the suburbs, the working-class residents of Lagos were forced to seek residence in the adjoining villages (suburbs) of the colony of Lagos where rent was cheap. The elite of Lagos Island remained where they were. By contrast, in Anglo-American cities, where the movement of the elite to the periphery during the industrial development era created the pre-condition for the return and reappropriation of central locations, industry declined and inner cities started to be renovated and reappraised. Revanchism was not a factor in Lagos. Also, Preteceille has shown that ‘the centre of Paris has never been abandoned by the local elites’. Even in Woodstock, South Africa, which mirrored ‘aspects of the international experience of gentrification’, those processes were overlaid by the peculiarities of the South African urban situation.Footnote 91

In addition, some of these areas were difficult to access in the colonial period because of poor road networks, unlike the suburbs of London and some cities of the United States where a modern railway system allowed easy accessibility. Yet, the working class of Lagos had to commute between these villages and central Lagos where they worked and conducted their business. The unintended results produced by the colonial policies of town planning and segregation were such that there was an influx of people into the surrounding villages of municipal Lagos which increased the demand for residences that were hurriedly put in place to take care of the avalanche of requests. Initially, these were readily available as cheaply as possible, but as more and more people moved into the area, rent went up and people moved into more rural environments to cut housing cost.

The problems of the colonial cities have their roots deep in the colonial situation and colonial approaches survive in their policies and development agencies.Footnote 92 The problems brought about by these policies reverberated in the post-colonial period as the post-colonial governments of Lagos up until 1990 reproduced these errors on an even wider scale. A corollary of this was the division of Lagos – a neglected area inhabited by the poor with all the attendant social malaise and a well-planned area inhabited by the rich. Urban blight in the period under study was synonymous with unregulated development, housing crises, flooding, blocked drains, terrible roads, inadequate electricity supply, the absence of potable water, an inefficient transport system, crime, drug addiction, prostitution and a host of other social and psychological problems. They also had certain distinguishing characteristics – they were usually located in environmentally fragile areas. People in these areas were wary and suspicious of outsiders who were usually thought to be government agents or spies. They seemed to have developed a general feeling of hopelessness, helplessness, frustration, isolation and resignation. They took to hard living, specifically heavy drinking, crime, drug addiction and prostitution, as a way of escape from their predicament. Thus, although some scholars have argued that the process of gentrification can bring about development, attract businesses and even lower the crime rate in an area,Footnote 93 the reverse was the case, especially in the neglected areas of Lagos.

On the whole, gentrification in Lagos in the period under study did not follow the pattern identified by the Anglo-American apologists for gentrification who associate it with inner cities, rehabilitation/refurbishment, the middle class and economic transformation. We need to rethink the way we apply the concept across the board. I need not reiterate the argument of Eric Clark in the Atkinson and Bridge collections.Footnote 94 But rethinking the application of the concept of gentrification will enable scholars of urban studies to provide the general public with more useful analyses of our urban space. As the case of Lagos has shown, gentrification occurred not only in the inner city (central Lagos) alone but also in areas outside the inner city such as Ikoyi, Victoria Island, Lekki, Surulere, Yaba and areas under the Ikeja division, most of which were rural in the colonial period and for different reasons. Besides, the buildings that appeared in these areas were new and not necessarily refurbished/renovated ones. The contention that the buildings in Maroko and other areas of Lagos state where gentrification occurred were renovated is not correct.Footnote 95 In Maroko, for instance, the demolition exercise in 1990 did not leave a single residential building standing. All were completely demolished. New owners bought portions of land in the area and new buildings emerged in Lekki Phase I and Victoria Island Extension as shown earlier.

The issue of ‘developers’ raised by NwannaFootnote 96 should also be regarded with the utmost care so as not to confuse it with the idea of property developers and real estate companies in the Anglo-American urban space ‘exploiting opportunities to sell new condos’. This is a phenomenon that entered the Lagos urban renewal lexicon in the twentieth century and became more fashionable from the 1980s. It is an arrangement whereby the original owners of a building request the assistance of a building contractor to reconstruct the property and use it for a certain number of years after which it would revert to the original owners. The building is completely pulled down and a new structure replaces it.

In addition, the experience of Lagos also shows that gentrification predates World War I. It dates back to the nineteenth century, as is shown earlier with the settlement of the colonial officers and European traders at Ehin Igbeti (later Marina). This settlement set the pattern for the British replanning of Lagos Island. Therefore, the attempt by some of those who have written on gentrification in Lagos to fit the processes of gentrification in Lagos into the Anglo-American context does not help our understanding of the phenomenon. The experience of Lagos has definitely shown that there may be similarities in the processes of urban change in different cities, but there are also peculiarities. Understanding those peculiarities is key to our knowledge of urban renewal/regeneration in different cities of the world.