The assumption that ‘any social reality is, first and foremost, space’ – as pointed out by Fernand BraudelFootnote 1 – should imply the adoption of space itself as a crucial element for the study of society, both past and present. Modern historiography, however, has traditionally assigned far less relevance to the spatial dimension with respect to its temporal counterpart. This has determined a sort of ‘divorce’ between time and space, and a consideration, more often than not, of the latter as more of a neutral backdrop to human action than an essential factor with a specific influence on historical developments. Even in the field of urban history, in which space traditionally represents a fundamental dimension of analysis, many studies involving social groups have conceived of urban space simply as a place, in general inert and neutral, within which to examine the structure and actions of classes.Footnote 2 It is only in relatively recent times, in the wake of the ‘spatial turn’ in human and social sciences influenced by the ‘new’ cultural geography and post-modern thinking, that scholars have turned their investigations to the relationships between urban space and social identities adopting new perspectives and assuming the former as an essential reference for the construction and expression of the latter.Footnote 3 In particular, various studies have explored the relationship between urban space and its internal articulations on the one hand, and the development of middle-class and bourgeois identities on the other, in different national contexts during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 4

Following the suggestions offered by such historiography, this article deals with the relations between dwelling space and social identities in post-war Rome, concentrating on the bourgeoisie. However, before moving on, it is necessary to clarify the use of the terminology adopted in the text. Unlike Great Britain, in Italy the representation of society as a body structured according to classes, and thus the adoption of a coherent language of class in order to describe its articulations, has never been a shared custom.Footnote 5 The Italian terms ceti medi (or classi medie) and borghesia – which can be considered equivalent to the English ‘middle classes’ and ‘bourgeoisie’ – have vast and blurred meanings, in addition to at least a partial overlap.Footnote 6 In adherence to the terminology used in the sources, the choice has been made here to use the term ‘bourgeoisie’ rather than ‘(upper) middle classes’. It must be pointed out, however, that when writing in Italian, the preferred expression would be ceti borghesi, a plural form with a broader and more composite meaning than the singular ‘bourgeoisie’. In any case, it must be clarified that these expressions are used here in primarily cultural terms, that is, in reference to the lifestyles, values, tastes and consumption patterns of individuals and social groups, rather than in strictly economic-social terms, or as categories based on occupation, income and wealth.Footnote 7

It must also be pointed out that the term ‘dwelling space’ is used here on two levels: micro (the home, both internal and external) and macro (the neighbourhood of residence). Building on the idea that the aspect and location of the home are symbolic elements that represent important indicators for the social positioning of residents and their differentiation in terms of class and status,Footnote 8 this article investigates in what forms, in post-war Rome, bourgeois social identities were formed and expressed through elements related to the residential environments inhabited by these same social groups.

To understand fully the relevance of this theme, it is worthwhile pointing out that during the twentieth century, and in a particularly marked manner after World War II, Rome was defined by a strongly bourgeois connotation. This is true in terms of both its social composition, at the time a reflection of its role as a capital city in which tertiary functions prevailed over industrial development, as well as the representations of the city in public discourse, often marked by a vein of controversy.Footnote 9 However, notwithstanding this importance, the Roman bourgeoisie has been the object of very little study. In fact, for the period examined here, the research on social groups and their residential environments, conducted largely by sociologists, has concentrated almost exclusively on the working classes and the poor.Footnote 10

In order to analyse the dwelling space of the Roman bourgeoisie, it is first of all necessary to identify where these social groups lived. A number of studies on the social geography of Rome conducted by geographers and sociologists demonstrate that at the beginning of the 1950s the area with the most elevated social composition, that is, with a significant concentration of bourgeois residents, consisted of a portion of the historic centre plus a group of neighbourhoods located north of it. During the following two decades, this area, on the one hand, was consolidated and enlarged towards the north, expanding in particular towards the north-west, and, on the other hand, extended towards the south, creating a second nucleus of bourgeois neighbourhoods in the south-west.Footnote 11

The choice has thus been made to focus our analysis on two neighbourhoods located along this north-west–south-west curve: Parioli and Casal Palocco. In virtue of their characteristics and the symbolic values associated with them, each of these two quite different neighbourhoods can be seen as constituting a sort of model of Roman bourgeois residential environment: respectively, a traditional bourgeois neighbourhood in the case of Parioli, and a modern American-style one in the case of Casal Palocco. As will be shown, they both represent privileged laboratories of observation in which the elements of relation between dwelling space, lifestyles and social identities emerge in a particularly marked manner. In the absence of comparable quantitative data on social composition, this article focuses on such elements adopting a socio-cultural approach and relying mainly on qualitative description drawn from sources such as literature, film, newspapers and magazines, autobiographies, and oral history interviews.

A traditional bourgeois neighbourhood

‘This is the privileged area of Rome, and you are not truly refined and up-to-date if you don't live “in Parioli”.’Footnote 12 These words, taken from an article on the ‘upper-class neighbourhoods’ of the Italian capital published in the municipal government's magazine in the early 1950s, are very significant. They clearly indicate that living in the Parioli neighbourhood was considered an important element of distinction, a true and proper constitutive trait of an elevated social status. For the purposes of this article, the analysis of the characteristics of this neighbourhood and the social identity of its inhabitants is thus of great interest.

Parioli is located in northern Rome, between Viale Tiziano and the parks of Villa Glori, Villa Ada and Villa Borghese. Its development can be traced back to the first decades of the twentieth century, with a considerable acceleration in the inter-war years. During this period, upmarket blocks of flats were built in the area, which was home – alongside important political and military figures such as Pietro Badoglio, commander-in-chief of the Italian army, and Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law and foreign minister from 1936 to 1943 – above all to professionals and public officials, giving it a clearly distinctive social identity with respect to those areas inhabited by the lower middle class (Figure 1).Footnote 13 As will be seen in more detail later in this article, the construction of Parioli was then completed between the end of World War II and the 1950s, in the context of the building boom that invested Rome and Italy's other large cities.Footnote 14

Figure 1: Parioli, a group of villini for public officials built in the 1920s on Via Mangili (M. Sanfilippo, La costruzione di una capitale. Roma 1911–1945 (Cinisello Balsamo, 1993))

Unfortunately, there is no reliable data about the social composition of the neighbourhood during the period under consideration.Footnote 15 What is certain, however, is that in general terms the population of Parioli was of elevated social origins. Indicative in this sense is a report from the early 1950s by the young journalist Elio Petri – who later moved on to an important career as a film director – in which he refers to Parioli as ‘the richest neighbourhood in Rome’.Footnote 16 In reality, during the post-war period Parioli became a true icon of the rich neighbourhood, not only Roman, but also national. Evidence can be found, for example, in an article published in the Milanese newspaper Il Giorno in 1962, in which the well-known journalist Giorgio Bocca stated that in Carpi – a small town in the Emilia region home to an affluent knitwear industry – the area of villas inhabited by wealthy businessmen was known as ‘the Parioli of Carpi’.Footnote 17

If these representations of Parioli by external observers highlighted the wealth of the neighbourhood's residents, ‘internal’ sources, such as autobiographies and oral history interviews with residents, offer interesting elements relative to their values and lifestyles. In her autobiography, for instance, Marina Ripa di Meana – stylist, writer and well-known member of the Italian jet set, as well as the daughter of a lawyer and a housewife from Parioli – tells of how, as an adolescent in the 1950s, she and her sister were prohibited by their mother from walking through the neighbourhood because ‘it was not correct for two young girls to wander the streets “like two tramps”’.Footnote 18 The reference to the figure of the ‘tramp’ reveals the importance, in these domestic environments, of a traditional bourgeois value such as respectability. In fact, it indicates that Marina's mother's restrictions were not derived solely from a generic desire to control her adolescent daughters, but also from her belief that spending one's time in the streets was a form of behaviour perhaps akin to the working classes or the poor but, in any case, unworthy of a bourgeois lifestyle.

The oral history interviews conducted for this research indicate that also under other respects the education passed on to children was of a traditional nature. Of particular interest, from this point of view, is the perspective offered by the historian Francesca Socrate, daughter of an ‘a-typical’ Parioli family, given that her parents, functionaries of the Italian Communist Party, had a different income and political orientation than the majority of the neighbourhood's residents, in general wealthier and politically conservative.Footnote 19 Socrate recalls how her classmates received an education strongly focused – other than on bourgeois respectability and a repressive attitude towards sexual behaviour, above all for young girls – on the learning of good manners and ‘a rather rigid etiquette’.Footnote 20 This implied, amongst other things, knowing how to behave at table, an element whose importance was underlined by sociologists, such as Pierre Bourdieu, who observed that the bourgeois conception of dining as a rigorously formalized ‘social ceremony’ is opposed to the elementary ‘plain eating’ of the working classes.Footnote 21 ‘For example – Socrate recounts – they knew how to peel fruit using a fork and knife. I remember, because I didn't know how to do this; and a friend's father made fun of me because I always ate a banana in order to avoid the problem [of having to peel fruit using cutlery].’Footnote 22

Equally rooted in tradition was another characteristic element of the inhabitants of Parioli: their elegant and rigorously classic style of dress. This form of dress can be found at the centre of the portrait of a crowd waiting for the Sunday mass in front of the church of San Roberto Bellarmino in Piazza Ungheria, depicted by the writer and journalist Carlo Laurenzi in a diary-like book from the mid-1950s. Using a light and ironic tone, Laurenzi describes the women's suede jackets, the camel hair coats and Scottish scarves worn by the elderly, the tailleurs and valuable pearl necklaces worn by girls, pointing out that even young children ‘after turning five years of age and acquiring the right to wear their first suit, [were] already dressed in clothes from Caraceni’.Footnote 23 In a decisively more critical manner, the protagonist of Alberto Moravia's novel La vita interiore – a girl from Parioli who develops a morbid rebellion against the bourgeois universe embodied by her adoptive mother – describes the expensive tailored clothes worn by the latter, highlighting the uniformity of the elegant dress code adopted by the neighbourhood's residents: ‘In a certain sense, it could be said that she wore a uniform. The uniform of a bourgeois resident of Parioli.’Footnote 24 Finally, in an autobiographical book, the screenwriter Enrico Vanzina – born in 1949 and son of the director and screenwriter Steno, one of the many figures from the world of cinema who lived in the neighbourhood – recalls, with a certain dose of self-irony, his youthful fascination with traditional English elegance: ‘We young people would meet in Piazza Euclide, dressed in cavalry tweed trousers and Saxon shoes. Thinking back, we were a bit pathetic in our desire for an amatriciana-style England.’Footnote 25

Notwithstanding Vanzina's consideration that he ‘never fully accepted the idea of being a “pariolino”’,Footnote 26 he and his friends appear to be typical representatives of this interesting social category. A research of Italian dictionaries indicates that the term pariolino came into use during the 1940s. In fact, it appears in the appendix dedicated to neologisms, edited by Bruno Migliorini, in the ninth edition of the Dizionario moderno delle parole che non si trovano nei dizionari comuni, from 1950, though it is not present in the previous 1942 edition. The text reads: ‘From the elegant Parioli neighbourhood in Rome. Often used with a hint of envy or irony.’Footnote 27Pariolino is thus an adjective constructed on the base of what appears to be one of the fundamental characteristics of the neighbourhood: elegance. Dictionaries and works of literature testify that the grammatical function of the term and its meaning – in which the element of elegance was mixed with distinction and respectability – remained substantially unchanged during the following years. In the 1961 Niccoli dictionary, for example, we find the term pariolino as an adjective, with the meaning: ‘dwelling in the exclusive Parioli neighbourhood in Rome’ and, in an extended sense, ‘refined; stylish in dress and expression’.Footnote 28 In this sense, and with the hint of irony mentioned by Migliorini, the term was used by Alberto Arbasino in his 1963 novel Fratelli d'Italia, in which, among the guests at a party in a noble palazzo, we find a few ‘parioline girls’.Footnote 29

In the following decade, by contrast, a twofold evolution of great importance took place: on the one hand, the use of the term as a noun and, on the other hand, a shift in its meaning. For example, in the aforementioned novel by Moravia, a friend from Milan addresses the protagonist as follows: ‘You are a girl from a good family; how do they refer to you in Rome? As a pariolina.’Footnote 30 In this case, the term is used as a noun, but the semantic sphere – ‘from a good family’ refers to wealth and respectability – is similar to the previous one. Decisive in the mutation of the meaning was an episode from the crime pages: the so-called Circeo crime. At the end of September 1975, a group of young bourgeois boys raped and beat two working-class girls in a villa near the Circeo, a seaside resort not far from Rome. One of the girls died as a result of the beating, while the other managed to survive and assist with the capture of the assassins (with the exception of one, who fled justice). These latter were militant neo-fascists who, although not living in Parioli, used to meet in some of the neighbourhood's bars.Footnote 31 Thus, in various of the many newspaper articles dedicated to this event, the boys were referred to as ‘pariolini’ or ‘young pariolini’ – with the term pariolino often between quotation marks, indicating that it had not yet fully passed into common usage.Footnote 32

As testified to by the major Italian dictionaries, this passage took place in the following years, also and above all in the wake of the vast public debate raised by the Circeo crime. In the Zingarelli dictionary, the term pariolino – absent in the 1970 edition – appeared in the subsequent 1983 edition as ‘from Parioli’ (adjective) and ‘young man from a good family with right-wing political tendencies, often arrogant or rowdy’ (noun).Footnote 33 Analogously, the 1987 Garzanti dictionary presents the term as an adjective meaning ‘from Parioli, an elegant residential neighbourhood in Rome’, and a noun meaning ‘young wealthy and snobbish Roman, often sympathetic to right-wing politics’.Footnote 34 It is evident that, with respect to the 1950s and 1960s, the meaning of the term had changed significantly, at least in its use as a noun. It now referred exclusively to the younger male generation and highlighted – alongside an elevated social extraction – snobbery, a right-wing political orientation and a propensity for violence.

As mentioned, this change in meaning must be directly related to the Circeo crime. At the same time, it is important to point out that, even before this tragic event, snobbery and a sense of social superiority were already considered specific attributes of the residents of Parioli. Evidence of this can be found, for example, in a film from the late 1950s, I ragazzi dei Parioli, whose plot is surprisingly similar to some aspects of the Circeo crime: two boys from Parioli, rich and spoiled, pose as film producers seeking actresses for a film and manage to lure two working-class girls who dream of a career in cinema to their home; the boys induce the girls to drink and attempt to seduce them, though with scarce results; finally, they are joined by other friends and improvise a party, making ferocious fun of the girls for their naivety and lack of class (Figure 2).Footnote 35

Figure 2: Boys from Parioli making fun of a working-class girl in the movie I ragazzi dei Parioli (1959)

In any case, the fundamental piece of information here is that between the 1970s and 1980s – based on a few characteristics of the neighbourhood and in the wake of news stories – the pariolino had become a social type, with well-defined and universally recognizable traits. The term had moved away from the exclusive reference to the neighbourhood, and it was now possible to be a pariolino without living in Parioli. On the other hand, not all young residents of Parioli considered themselves pariolini. Recalling his youth, for example, Paolo Piperno identified and contrasted two typologies of young people in 1960s Parioli. On the one hand, the pariolini who met in Piazza Euclide, whose wealthy parents gave them significant sums of money to purchase brand-name clothing, scooters or cars and, as a result, possessed an air of superiority, ‘somewhat like supermen’; politically, they inclined towards the right, and showed ‘a slightly more relaxed attitude towards school’, often taking home lessons or attending private institutions (more costly and less difficult than public schools). On the other hand, ‘the non-pariolini who, however, lived in Parioli: those, for example, like myself’, who came from less wealthy families and had less pocket money, attended public schools and received a severe education focused on a sense of obligation that required above all effort in study and high scholastic grades, had a generally left-wing political orientation and were, overall, ‘much more normal’.Footnote 36

Thus, beneath the uniformity of many representations of the neighbourhood and its residents, Parioli was, instead, home to diverse social identities. These internal articulations also emerged in the memory of other interview subjects, in direct relation – an important element to this article – to different parts of the neighbourhood. For example, Michele Surdi recalls that during the 1960s his classmates at the Mameli – the secondary school attended by the majority of Parioli youth – belonged to ‘two social groups’ that were also ‘two geographic groups’. On the one hand, ‘the intellectuals, to whom, even rebelliously, I belonged’, who were left-wing, read books and wore ‘their parents’ old clothes’. On the other, the right-wing students, who did not read and ‘wore English shoes at 15 years of age – to my great envy, truth be told – and cashmere sweaters’. In terms of music, while the first ‘listened to Brel, Brassens and the French chansonniers, as well as Rita Pavone, the others listened exclusively to Rita Pavone’. In terms of family background, the first came from a ‘liberal or cultured bourgeoisie’, composed above all of professionals and intellectuals, who were long-time residents of the neighbourhood and lived in ‘the old, 1930s Parioli’. The second, by contrast, were the children of traders, managers of public companies and builders, who were relative newcomers to the neighbourhood and lived in ‘the new, 1950s Parioli’: a ‘commercial bourgeoisie’ looked upon with a sense of superiority by the old residents, who considered them vulgar and crass.Footnote 37

The memory of these residents thus paints a socially composite portrait of Parioli, structured around a dichotomy, in terms of values, tastes and lifestyles, between an ‘us’ composed of a consolidated, cultured and austere bourgeoisie, and a ‘them’, represented by a more recent and perhaps wealthier bourgeoisie, though less educated and with a tendency to flaunt their wealth. So, to use the words of Bourdieu, Parioli can be seen as a ‘social space’, home to two different fractions of the bourgeoisie, one richer in economic capital, and the other with a greater cultural capital.Footnote 38

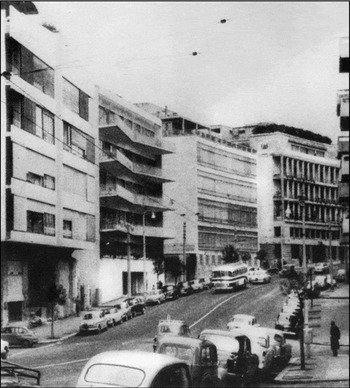

A modern American-style suburb

The second neighbourhood being examined, Casal Palocco, is very different from the first in various respects, first of all in its construction.Footnote 39 As mentioned above, Parioli was completed during the post-war period, when private developers and building co-operatives constructed a multitude of modern-styled blocks of flats around pre-existing nuclei. Some of these buildings were of architectural importance, such as the Casa del Girasole in Viale Bruno Buozzi, designed by Luigi Moretti.Footnote 40 In general terms, however, the various interventions were neither sufficiently planned nor co-ordinated, and led to the progressive densification of the neighbourhood (Figure 3). As a result, in 1951, the journalist Antonio Cederna stated that the area of the new Parioli was growing into ‘the most chaotic neighbourhood of the century’Footnote 41 and, at the beginning of the 1960s, the planning historian Italo Insolera pointed out that, while up to ten years earlier Parioli ‘undoubtedly offered a discretely comfortable environment, with numerous gardens, high-class dwellings, villas, and calm streets’, later ‘building speculation completely destroyed it: the usual wave of blocks of flats submerged everything like a magma, transforming beautiful panoramas into “the façade on the other side of the street”’, while in the ‘naturally narrow’ streets there was no longer any space to park ‘not only the “American cars” so popular in the area, but even the [Fiat] “600s” and “Vespa [scooters]”’.Footnote 42

Figure 3: Viale Bruno Buozzi, one of Parioli's main streets, in the post-war period; the first building on the left is Luigi Moretti's Casa del Girasole (private)

Casal Palocco, on the other hand, is an extensive suburb located approximately 10 km south-west of the city. It was planned and constructed between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s by a single large development company: the Società Generale Immobiliare (SGI). Based on the model of the American suburb, Casal Palocco was proposed as a radical alternative to the reduced urban and environmental quality of inner-city neighbourhoods such as Parioli. The widespread promotional campaigns run by the SGI highlighted the abundance of green space, the absence of traffic and noise, the ample supply of sports and commercial facilities, as well as the difference in the homes – villas and single- or multi-family houses, all with their own garden – with respect to traditional flats in condominium buildings in urban neighbourhoods. Focusing on key concepts such as modernity, freedom, youth, holiday and serenity – ‘the most modern residential neighbourhood’, ‘a new way of dwelling for the young of yesterday, today and tomorrow’, ‘a home immersed in nature for being on holiday 365 days a year’, ‘a home in Casalpalocco is living in freedom’, were only some of the slogans used – the advertisements promised prospective buyers not only a different home and a different residential environment but, in more general terms, a new lifestyle (Figure 4).Footnote 43

Figure 4: ‘A home immersed in nature for being on holiday 365 days a year’, advertisement for Casal Palocco, 1967 (Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Società Generale Immobiliare Sogene, Ufficio Pubblicità, folder 3, subfolder Roma dépliants)

Also thanks to these promotional campaigns, Casal Palocco attracted above all those employed in relatively nearby areas with a high concentration of tertiary workplaces, such as the EUR business park and the Fiumicino airport. An SGI publication stated that in 1972 some 62 per cent of all breadwinners were executives and clerks (with pilots and other airline company employees alone amounting to 14 per cent), 11 per cent were self-employed, 9 per cent traders and 5 per cent industrialists and company directors.Footnote 44 Though it is not possible to make a precise comparison with Parioli due to the lack of analogous data for this neighbourhood, it can be stated that with all probability the population of Casal Palocco was slightly less elevated in its social extraction and, as a recently developed area, with a lower average age.

The articles, interviews and letters in the local monthly magazine La Gazzetta di Casal Palocco constitute an excellent source for understanding the social reality of this neighbourhood. Between 1969 and 1970, the magazine asked numerous residents why they chose to live in Casal Palocco and their opinions about life in the area. Arun Chattergjie, an Indian executive at the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) who had lived in Parioli before moving to Casal Palocco, explained his choice as follows: ‘[There was] too much noise . . . and then we wanted a house with a garden, near the sea.’Footnote 45 The jeweller Marcello Cecchini spoke of a desire to abandon ‘the cages of clay brick, inside which you can count the steps of the old lady living upstairs, while from outside exhaust gases from buses and scooters come in, along with screams, the noise of trams, odours, and so forth’.Footnote 46 In short, freedom from the inconveniences of living in a block of flats and life in the city, to which the lawyer Domenico Pugliatti added another form of liberation, highlighting that in Casal Palocco ‘human relations take place on a simple level that frees us from the weight of urban formalities and helps us rediscover our more genuine side’.Footnote 47

This last argument is very important. A key element of the social identity of Casal Palocco's inhabitants was, in fact, the informality of behaviour and social relations. This was combined with a notably youthful attitude, shared even by the less than young, as pointed out in an article in the Gazzetta:

In conformist Italy, Casal Palocco is an island on its own, in which everyone feels young. Women of all ages wear miniskirts, taking advantage of the sun's healthy rays, or go shopping American style, with their hair curlers hidden under a scarf, using bicycles that are so good for the atrophied muscles of so-called civilian life, while men flaunt enviable suntans under their grey hair.Footnote 48

The informality of social relations clearly emerges in the stories of Rita Chiodoni, who moved to Casal Palocco as a child in 1963. She recalls how her parents often organized dinner parties or backyard barbeques with friends and neighbours:

‘So let's have a dinner party at so-and-so's’, American style: you bring this, you bring that – even this was a different way of living . . . I can make some comparisons: [when we lived in Rome] my mother went to my aunt's house and – perhaps because it was my aunt – she said: ‘I'll bring you something.’ Otherwise, you just went [and that was it]; maybe you brought sweets. But you didn't go with dishes of food. Because this was almost offensive; she would say: ‘Why would you bring a tray of lasagne! Do you think I don't have money to make lasagne?’ By contrast, here in Casal Palocco, it became normal that you went to so-and-so's and brought something, someone else brought something else; it was about uniting families and spending time together.Footnote 49

What is important to note here is that both the Gazzetta article and Rita Chiodoni agree on the ‘American-styled’ behaviour of Casal Palocco's residents, marked by practicality and informality. These attitudes were also expressed in their style of dress, as pointed out in another article in the magazine, which recommended that women accompanying their children to school or going shopping wore trousers ‘because they are non-invasive and practical fashion items’ and ‘are very useful when riding a bicycle, [which is] an everyday tool . . . In Casal Palocco, with its entirely local taste, free from the slavery of an overly formal fashion, above trousers one wears a long pullover, but never an identical jacket; rather, a comfortable leather jacket.’Footnote 50 Men also tended to adopt a casual style, as shown by a letter to the magazine in which a woman pointed out her husband's surprising change in attitude: ‘Before, he would not even step out onto the balcony without a tie; now, in Casalpalocco, he says it is ridiculous to go against the crowd, that even the bourgeoisie changes, and we must be careful not to let ourselves go, because in the end we grow old only if we want to.’Footnote 51 In analogous terms, Fabrizio Schneider, for many years the director of the Gazzetta, recalls that: ‘there was almost a uniform: the tracksuit. Everyone wore a tracksuit . . . The tie no longer existed . . . This was the most appreciated thing: “Finally we don't have to change our clothes; we can leave the house dressed as we are, in the end we know everybody and there is no need for formalities of any type”.’Footnote 52

The informality, youthfulness and ‘Americanism’ of Casal Palocco's residents must be placed in direct relationship with the profound social and cultural changes that swept across Italy between the late 1950s and the early 1970s. Thanks to the ‘economic miracle’, Italy passed from being a relatively poor and primarily agricultural country to one of the world's top industrial economies.Footnote 53 The resulting massive increase in income permitted, above all the middle classes and bourgeoisie, a significant growth in consumption and a strong proportional shift in purchases from necessity to superior goods and services (cars and household appliances, recreational activities and holidays, etc.).Footnote 54 The process of modernization was deeply influenced by models, symbols and ideas coming from the US. In fact, the new patterns of consumption were closely linked to the rapid diffusion of an American-styled consumer culture that imposed itself over the previous set of values centred on the predominance of saving, though it must be stressed that Americanization did not imply passive reception of external models but a complex synthesis of overseas influences and local traditions and trends.Footnote 55 This was accompanied, especially from the mid-1960s onwards, by a true revolution in values and lifestyles, which involved aspects such as gender roles, sexual behaviour and relationships between different generations and social groups.Footnote 56 From this last point of view, traditional hierarchies and forms of deference lost their vigour under the prevalence of more informal attitudes in social relations.Footnote 57 Young people played a leading role in such processes of change, distinguishing themselves from adults and acquiring identity as a social group strongly characterized by specific lifestyles and forms of material and cultural consumption.Footnote 58 What is more, youth culture began to exert an entirely new influence on the rest of society; as pointed out by Arthur Marwick: ‘Such was the prestige of youth and the appeal of the youthful lifestyle that it became possible to be “youthful” at much more advanced ages than would ever have been thought proper previously.’Footnote 59

It is thus against the backdrop of these impetuous social and cultural transformations that we must read the words of a woman who, when interviewed by the Gazzetta during a survey of the neighbourhood, declared that by moving to Casal Palocco she and the other residents had abandoned everything that they had been before, ‘to become friendly, anti-conformist, sporty and, above all, fundamentally, inexorably, “palocchini”’.Footnote 60 In analogous terms, one of the people interviewed for this research, Pippo Ciorra, when asked if as a young man he considered himself to be a palocchino, responded affirmatively, specifying that ‘being a palocchino meant being a weirdo, substantially: however, a well-bred weirdo; . . . a sort of out-of-place American; . . . it meant that you wore very worn-out Levi's, and your shirt hanging out [of your trousers]; . . . palocchino was also a synonym for spoiled, very spoiled’.Footnote 61

In short, the residents of Casal Palocco shared a strongly characterized social identity – wealthy though informal, youthful and American-style – and they identified with their residential environment, considering themselves to be palocchini. All the same, the term palocchino never became a universally recognized social type, as was the case with the pariolino. This notwithstanding, analogous to what has been said about Parioli, when seen from outside, the fact of living in Casal Palocco was considered an element of distinction, indicative of an elevated social status. This is a circumstance of extreme importance to this article that emerges, for example, in the words of Rita Chiodoni, who recalls that, although she did not boast about living in Casal Palocco, her friends in Rome said: ‘“Well, she lives in Palocco”, as if to say I was a bit stuck up’; and even at the school she attended, in the EUR neighbourhood, ‘you were considered, you could say, in a certain manner, a bit more – what I mean to say is a bit more aristocratic’.Footnote 62

Also in Casal Palocco, in reality, beneath the uniformity of the representations as a wealthy neighbourhood and a youthful and informal residential environment, there were various internal articulations. Its social composition, for example, was homogeneous inside the various isole (residential complexes) of which the neighbourhood was composed, though between the one and the other there were differences that some residents were quick to point out in a polemical manner or with a hint of social competition.Footnote 63 During the discussions regarding the criteria for admission to the local club, in addition, there emerged a contrast between the democratic approach of those who felt it should be open to all residents and the search for distinction of those who wanted to ensure a more selective membership through the application of high fees.Footnote 64 Even in the general climate of informality, finally, various residents reiterated the necessity of preserving the respectability of the neighbourhood, decrying the practice of hanging laundry in front of home entrances or the presence of street vendors.Footnote 65 Rather than further investigating these internal articulations, however, a need for synthesis suggests that we abandon the macro scale and move on to an analysis of the Roman bourgeoisie's dwelling space at the micro scale: that of the home.

Bourgeois homes

Mario Soldati's 1962 short story Il verme tells the story of Margherita Marcucci, a minor noblewoman from the Marche region who marries a university professor living in Rome. The wedding turns sour and Margherita begins a tormented relationship with a young man, who becomes her lover. Beyond the developments of the story, what is important to this article is that Soldati imagines that, in view of the wedding, the protagonist had come to Rome ‘with a self-assured attitude and full of hope, to occupy the attico pariolino that represented her significant dowry and appeared to her, at the time, as an earthly paradise’.Footnote 66

Dwellings in Parioli were, for the most part, flats in buildings belonging to two of the typologies permitted by the city's master plan and building code: villini and palazzine. Their names were suggestive of a prestigious villa or palazzo (palace), and the characteristics of villini and palazzine – free-standing and relatively modest-sized buildings, with a garden or, at any rate, some open space around them – offered favourable exposure and ventilation, clearly differentiating them from the intensivi, which were taller and larger buildings often attached to one another.Footnote 67 As early as the 1930s, while this latter building type was most commonly associated with the petit bourgeoisie, the palazzina and villino were associated with the middle and upper classes.Footnote 68 Being smaller in size and having less flats, however, the villini were less remunerative for builders. As a consequence, from the mid-1920s onwards, Rome was witness to the construction of many more palazzine than villini,Footnote 69 and the prevalence of the former over the latter also characterized post-war Parioli. It is no wonder, then, that during this period the typology of the palazzina was strictly associated with the bourgeoisie, as found, for example, in the polemical identifications made by Insolera, according to whom ‘the palazzina is the home of the Roman bourgeoisie’ and ‘the other classes are differentiated also by their type of dwelling’, or the comments of Mario Manieri Elia, who pointed out that ‘an overbearing and insecure bourgeoisie culturally recognizes and socially identifies itself’ in the style of the palazzine found in neighbourhoods such as Parioli, ‘true and proper congested ghettos devoid of any real “urban” qualification’.Footnote 70

Inside the villini and palazzine, however, there was a precise hierarchy between flats, reflecting the pattern of ‘vertical differentiation’ typical of Mediterranean cities.Footnote 71 The most sought-after space was the attico, the ‘earthly paradise’ of the protagonist of Soldati's short story. This was the flat on the top floor, which benefited from the most light and air, and featured ample panoramic terraces. The attico represented a true and proper bourgeois status symbol, as highlighted, for instance, by the homonymous film released in the early 1960s. It narrates the story of a young woman of humble extraction who immigrates to Rome from the province and, devoid of any place to stay in the city, spends her first night camping out in the attico of a building under construction. From this moment onwards, conquering that attico ‘from which you could see all of Rome’ becomes her sole aspiration. The stages that lead to her integration within urban society are thus marked by self-interested relationships with different figures through whom she hopes to acquire the strongly desired flat. After marrying the elderly father of the engineer whose company constructed the building, she finally manages to realize her dream of social success.Footnote 72 Just how much living in an attico with a panoramic terrace was considered a constitutive trait of an elevated social status also emerges in an interview with Audrey Hepburn, granted to the popular magazine Oggi in 1970. Presenting the attico in a building in the city centre where she lived with her husband, a Roman neuro-psychiatrist, Miss Hepburn stated: ‘We have a divine terrace. All self-respecting Romans have one; and I have by now become a Roman.’Footnote 73

With respect to Parioli, Casal Palocco's dwellings were of another typology. With a few exceptions, they were not flats in condominium buildings, but villas and single- and multi-family houses with gardens. Living in a villa – a home that fused ancient noble images with modern Hollywood-inspired suggestions – was the ne plus ultra of social prestige: an element of distinction that was, not by accident, highly sought after also by that sort of new aristocracy composed of film stars and other members of the jet set, whose centre of gravity, during the years of the dolce vita, was Via Veneto.Footnote 74 Living in a villa, however, implied costs that only the wealthiest palocchini could afford, while the others had to ‘settle’ for semi-detached or terraced houses.

Irrespective of the building typology, in any case, a fundamental characteristic of Casal Palocco's homes was the presence of a garden. Allowing children to play outside and adults to rest, spend time with friends or dedicate themselves to gardening, it was one of the elements that fostered the youthful and informal lifestyle typical of this neighbourhood. An article in the Gazzetta, for example, when highlighting the difference between Casal Palocco and Rome's urban neighbourhoods, underlined that ‘in Via del Tritone you will never see distinguished men digging in the earth’, something that could instead be seen in Casal Palocco, where ‘people are used to this, and many could no longer do without’.Footnote 75 And Rita Chiodoni recalls:

You opened the gate to the garden, you were watering your lawn and you saw others further down [the street]: ‘Hey, what are you up to, watering your lawn? Why not come by for a coffee?’; and perhaps you stopped watering and went to your neighbours, talked, drank a coffee and spent your time there; then maybe you had dinner together.Footnote 76

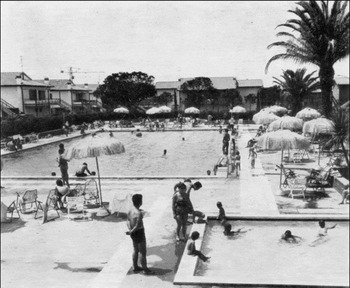

In relation to this, it is important to mention that in Casal Palocco various residential complexes (called isole) featured communal spaces and facilities such as swimming pools, tennis courts and play areas for children. Beginning in the 1950s, similar complexes proliferated in numerous bourgeois areas of Rome, in many cases constructed by the SGI.Footnote 77 As a consequence, if prior to this period domestic swimming pools and tennis courts were a privilege restricted to an elite group of wealthy people living in the most luxurious villas, these facilities later lost their purely exclusive nature and became important status symbols for the bourgeoisie. Besides representing an example of the ‘democratization of comfort’ tied to the profound economic and social transformations sweeping across Italy in the wake of the ‘miracle’, these facilities implied a redefinition of the relationship between private and public space. In fact, they offered residents the possibility of spending their leisure time ‘at home’, even if outside their domestic walls, creating a sort of intermediate sphere (one could refer to it as ‘semi-private’) that attenuated the sharp separation between domestic life and the world outside, which constituted a crucial trait of the traditional bourgeois lifestyle (Figure 5).Footnote 78

Figure 5: Casal Palocco, the communal swimming pool of the isola 33 on a Sunday afternoon (La Gazzetta di Casal Palocco, Aug.–Sep. 1969)

The presence of these residential complexes was thus another element that favoured informal attitudes and social relations. This is revealed, for instance, by the tennis tournament organized on the courts of the isola 22 in 1974, which was presented in the Gazzetta as ‘an opportunity to meet and get to know each other, in order to render relations between residents as friendly and informal as possible’.Footnote 79 Also from this point of view, 1950s and 1960s Parioli living was very different. Paolo Piperno's parents, for example, did not spend any time with the other families living in their palazzina, in which, what is more, the only common space was a courtyard used as a car park.Footnote 80 In analogous terms, Francesca Socrate recalls that in her villino ‘we only said hello’, and residents maintained a strong sense of privacy; networks of social interaction could be familiar, professional or political, but never neighbourly, because the presence of spaces of social interaction in the apartment building would have been seen as ‘a lowering of class’.Footnote 81

Moving on to an analysis of domestic interiors, the period under review was witness to transformations of great importance, such as the affirmation of the American-inspired assembled kitchen (known as cucina americana) or the diffusion of household appliances.Footnote 82 However, the focus here will be on the one space of the bourgeois home traditionally open to visitors: the living room (salotto-soggiorno).Footnote 83 In fact, by virtue of its accessibility to those extraneous to the family, this domestic space played an important symbolic role in expressing and simultaneously contributing to the definition of the inhabitants’ social identity.Footnote 84

In a short story from the early 1950s, Ercole Patti depicts a reception organized in a flat in Parioli, describing in a rather ironic tone the living rooms where the party takes place and the people participating in it. Important for the purposes of this article is the contrast between the exterior of the building – ‘a brand new tubular shaped building, wrapped in illuminated glass’ – and the interiors, filled with ‘neo-classical furnishings and coloured statues, alongside large branches of mimosa’.Footnote 85 In other words, the modernization of the architectural style was not matched by an analogous modernization of the living room furnishings. Similar indications can be found in the oral history interviews conducted for this research. The rooms described by Francesca Socrate – with their ‘valances, drapes, curtain covers, boiserie, tassels, heavy velvet couches, carpets and Chinese vases from I don't know what dynasty’ – recall the nineteenth-century salotti, filled with furniture and decorations; while Paolo Piperno summarizes the furnishings in his parents’ living room as follows: ‘To be honest, there was never anything modern in our home. That was not a kind of furniture that my parents liked.’Footnote 86

The living rooms of Parioli, in sum, were highly traditional domestic spaces, in which it was difficult to find the modern rationalist- or organic-style furnishings that characterized the most advanced European and American production in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 87 In all likelihood, many residents shared the opinion expressed by the first-person narrator of a story by Moravia regarding a home with modern furnishings: ‘all in tubular steel, exposed and cold; it was like being in a hospital's outpatient department’.Footnote 88 Even a modern device such as the television, whose regular broadcasts began in 1954, had trouble finding its place in these domestic spaces. Michele Surdi's family, for instance, postponed the purchase of a television for many years because ‘such a filthy and vulgar object could not be admitted’ in their home; but also in other dwellings this item was often located in a different space than the living room, or hidden in a cabinet, ‘because the television was ugly and ruined the salotto’.Footnote 89 On the contrary, traditionally furnished spaces were considered cosy and elegant, and antiques represented an important element of distinction. In fact, as pointed out by Bourdieu, ‘to possess things from the past’ – from noble titles to furnishings and paintings – expresses ‘a social power over time which is tacitly recognized as the supreme excellence’.Footnote 90

By contrast, the living rooms of Casal Palocco tended to be much more modern. According to Rita Chiodoni, ‘it was the house itself that required it’, in the sense that the modernity of the homes – from the exterior architecture to the interior layout, all the way to the presence of innovative elements such as built-in cupboards or fitted carpets – suggested congruous furnishings. Thus, when she moved to Casal Palocco, her parents purchased furnishings in the modern style to substitute those from their previous home, which ‘looked . . . bad, because they were, let's say, old [style] with respect to the structure of the house’.Footnote 91 In addition, the SGI's promotional strategy for Casal Palocco included the presentation of a few sample homes. Furnished in the modern style, they provided ideas and models for prospective buyers, for example Franco Proietti, who in 1969, after visiting one of these samples, chose the ‘so-called Swedish furniture’ for the living room of his new home.Footnote 92

All the same, it would be misleading to imagine that all living rooms in Casal Palocco were entirely furnished in the modern style. Photographs taken in the homes of residents and published in the Gazzetta, for instance, show modern living rooms alternated with others with traditional sofas and furniture.Footnote 93 Of further importance are the letters written to the architect who ran an interior design column in the magazine. In the December 1968 issue, for example, a woman wrote to ask for advice on how to organize her ‘living room in the nineteenth-century English style’, while another letter forced the architect to clarify that, when making recommendations to furnish living rooms in the modern style in a previous issue, he did not intend to exclude ‘in the most absolute terms, the insertion of antique furnishings in our living spaces’.Footnote 94 Thus, even amongst the palocchini, there were those who privileged antique and traditional furnishings, as an alternative to or alongside modern ones. On the one hand, this is an example of how individuals and social groups selectively accepted and adapted the domestic models proposed by modern architecture during the twentieth century to meet their needs.Footnote 95 On the other hand, it is an important confirmation of the persistent value of traditional furnishings in terms of elegance and distinction, even in a decisively modern and informal residential environment such as Casal Palocco.

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated that in post-war Rome dwelling space was fundamental to the development and expression of bourgeois social identities. In the first place, living in a certain neighbourhood or in a home with particular characteristics was an important indicator of status. Living in Parioli or in Casal Palocco, in a palazzina or a villino (perhaps in the attico), possessing antique furnishings or having access to external spaces such as swimming pools and tennis courts, were some of the numerous elements of distinction pertaining to the sphere of dwelling. As a matter of fact, these elements were not just indicators but also constitutive factors of an elevated social condition, because not only did they reflect the status of individuals and social groups, but also contributed to defining and reinforcing it.

Secondly, we have seen that diverse social identities were developed and expressed in different residential environments. The analysis of two neighbourhoods, in many ways paradigmatic, such as Parioli and Casal Palocco, has revealed the existence of very different, if not opposed, ways of being bourgeois. At the risk of some simplification, we can distinguish between a double ‘Parioli model’ and a single ‘Casal Palocco model’. The former was characterized by the co-existence of a consolidated bourgeoisie, with its austere behaviour, solid cultural bases, an attention to good manners and values such as decorum and respectability, alongside a new bourgeoisie, perhaps wealthier, though less refined and with a tendency to flaunt their wealth. Both, in any case, shared elements such as a traditionalist attitude (more in manners and forms of behaviour in the first case, and more in political orientation in the second), a classically inspired elegance, and a certain snobbery towards those considered to be socially inferior. The ‘Casal Palocco model’, on the other hand, consisted of a more modern bourgeoisie, characterized by youthful and ‘American’ attitudes, a sporty style of dress and informality in behaviour and social relations.

What is more, it is extremely important to point out that these differences must be read not only in synchronic terms, that is, as different ways of being bourgeois in different residential contexts, but also in diachronic terms. From this latter point of view, if considered in sequence, these ‘models’ are indicative of the evolution of the values, tastes and lifestyles of the Roman bourgeoisie over a period of significant social and cultural change. As it has been shown, during the third quarter of the twentieth century, Italy rapidly evolved from a still relatively traditional country into a modern consumer society that was deeply influenced by the American model and by the relevance of young people and youth culture, which became a crucial reference point for society at large. In this regard, to sum up, if in 1950s Parioli children and young people were dressed and expected to behave like adults, in 1970s Casal Palocco it was instead the adults who behaved and dressed like the young.

Another significant element that has emerged is that, during the period examined, the pariolino developed into a true social type. This indicates that so strong was the association of a residential environment such as Parioli with a set of attitudes, values, tastes, dress codes, leisure activities and meeting places, that the pariolino became a social identity defined precisely on the basis of these elements, that is, of lifestyle and patterns of consumption, irrespective of whether one actually lived in the neighbourhood or not. At the same time, it must be underlined that in Parioli, as in Casal Palocco, an in-depth analysis reveals a more blurred and contradictory picture than what has just been described. The complex interweaving of income levels, professional identities, consumption patterns, strategies of distinction, relationships with money and culture and elements of modernity and tradition makes it necessary to speak of a plurality of bourgeoisies. From this point of view, this study of post-war Rome presents an undoubted analogy with the results of the researches on the decades between Italian unification and the advent of fascism, the only period in the history of united Italy for which a consolidated historiography on the bourgeoisie is available.Footnote 96 In conclusion, it is hoped that this article will contribute to fostering a new wave of studies capable of producing analogous results, in terms of historical understanding, for the Italian bourgeoisie in the second half of the twentieth century. To this aim, the need is felt for a thorough comparison between Rome and other major Italian cities, which were quite different from the capital in terms of urban structure, built environment and social composition.