Scholarship on colonial policing has burgeoned in the last few decades. Criminologists, historians, sociologists and theorists of law offer a wide array of expertise on what has become an intrinsically interdisciplinary field of study. While pioneers paved the way for research that analysed colonial policing mainly from an institutional perspective,Footnote 1 later authors have shown that colonial police institutions were ‘far from monolithic’.Footnote 2 Recently, several scholars have started to unpack the ‘coloniality in colonial policing’, questioning what precisely makes colonial policing colonial.Footnote 3 Some have pointed to low staffing levels, limited budgets or policing supervision to expose the ‘essential weakness of colonial empires’,Footnote 4 while others stressed the ‘penal excess’, noting how policing was often exceptionally repressive and imprinted by racialized power asymmetries.Footnote 5 Numerous studies identified colonizers’ fears – be it of large masses, anti-colonialist revolts, vagrancy or unemployment – as key reasons for such violent policing regimes, and such anxieties will play a key role in this article as well.Footnote 6

Multiple authors have discussed how, in colonial cities and towns, colonial authorities consciously deployed urban planning and spatial segregation as ways to soothe these anxieties and facilitate police control and colonial order.Footnote 7 Recently, however, several authors have revealed that the implementation of these colonial urban planning schemes was often incomplete.Footnote 8 Nonetheless, the consequences of urban planning issues for colonial policing have not been addressed extensively, and despite the many publications revealing the intricate relation between policing and urban space, spatiality has often remained conspicuously absent from the academic debate on colonial policing.Footnote 9

A related body of literature has dealt with anti-colonial movements. Scholars have studied the protest and social unrest of the colonized as both a cause of and response to repressive colonial regimes and policing.Footnote 10 James Scott's seminal work marked a milestone, expanding the debate to other forms of ‘everyday resistance’ that had escaped scholarly attention.Footnote 11 However, his publications and the academic work he inspired have been criticized not only for overly romanticizing ‘ordinary people’ as ‘smart and crafty rebels’, but also for overly politicizing mundane practices.Footnote 12 As Benoît Henriet recently argued, while these prosaic struggles also draw ‘attention to some practical failures of the colonial rule’, ‘rather than resistance, adaptation seems to be a more suitable term’ to describe some of the ways in which colonial subjects ‘merely tried to work “the system…to their minimal disadvantage”’.Footnote 13 Actions of colonized subjects in response to daily policing routines – which I will discuss in this article, and which have been largely overlooked in colonial policing studies – seem to reflect practices of both ‘everyday resistance’ and ‘adaptation’. Rather than politically driven ‘resistance’, these actions were likely fairly local and non-political outbursts of unrest and ‘adaptation’; yet, their effects were undoubtedly political, as they confirmed and further intensified European anxieties surrounding African urban masses and impacted the way colonial policing was conducted.

In this article, I address the intricate relation between anxiety, colonial policing, unrest and urban space, and stress the importance of inserting spatiality into the academic debate on colonial policing. I do so by zooming in on the colonial history of Kenya, a neighbourhood in Lubumbashi, the second city of the Democratic Republic of Congo.Footnote 14 Kenya is nowadays often considered the city's hotspot, a ‘bastion of bandits and hemp smokers’ whose reputed ‘crime rates are the highest of Lubumbashi’. As a result, Lubumbashi's inhabitants often refer to it as the ‘Commune Rouge, because of the violence’ that is believed to plague the quarter.Footnote 15 Of course, tracing the origins and meanders of such a sobriquet is difficult, and not the aim here. However, what this article will reveal is that Kenya already had the reputation of being a dangerous neighbourhood during Lubumbashi's colonial past.Footnote 16 Elisabethville – as the city was called until 1966 – was founded in 1910, but the planned urban development of Kenya took place only after World War II, when colonial rule was increasingly questioned under the impetus of the rising world powers of the USA and the Soviet Union.Footnote 17

In response, Belgium, like France and Great Britain, adopted a new colonial discourse and started promoting a ‘harmoniously racially mixed’ colonial society – then trumpeted as the communauté belgo-congolaise.Footnote 18 Belgian King Baudouin publicly endorsed this new political discourse by advocating for improved ‘human relations between Whites and Blacks’ and a ‘true communauté belgo-congolaise’.Footnote 19 Another important advocate was Léon Pétillon, governor-general of Belgian Congo from 1952 until 1958, who developed the idea throughout several public speeches. While he remained a fierce advocate of continued colonial rule, he did support a ‘mutually profitable union’ between colonized and colonizers, with ‘reciprocal rights and obligations’.Footnote 20 It was in this reciprocity, however, that the communauté belgo-congolaise still implied a racial hierarchy, with Europeans having a moral obligation to educate and Africans reduced to a pupil in need of tutelage. Despite its promises, the discourse of the communauté belgo-congolaise remained not only vague, but also superficial, as its proclaimed socio-political changes were, in effect, limited.Footnote 21

The global shift in colonial policy-making led historians such as Crawford Young and Frederick Cooper to characterize the post-war period as the era of ‘welfare colonialism’ or ‘developmentalist colonialism’.Footnote 22 Seemingly oxymoronic, these notions acknowledge the genuine attempts by colonial authorities to improve living conditions of the colonized, while not losing sight of other, economic and political motives that colonial policy-makers continued to pursue during this decade. For example, various authors have shown that by improving social amenities, colonial authorities not only aimed to increase the well-being of the colonized and legitimize colonial rule, but also boost the productivity of African labourers and ‘manage their socio-political activities and lifestyle’.Footnote 23 In the context of Belgian Congo, historian Nancy Hunt described the following two ambiguous and intertwined ‘modes of presence’: a ‘biopolitical’ state that ‘worked to promote life and health’ and a ‘nervous state’ that ‘policed and securitized’ out of a ‘dread’ of African insurgencies.Footnote 24

Kenya's initial urban planning project combined these two ‘modes’. On the one hand, the authorities sought to provide Kenya's future inhabitants with improved urban living conditions by offering better housing, ‘modern’ infrastructure and increased social amenities. On the other, Elisabethville's European policy-makers’ fear of large African masses led them to identify Kenya, the most populous African neighbourhood, as a possible hotbed of political insurgency. Thus, while Kenya's urban planning was to embody the new post-war welfarist aspirations of colonial policy-makers, its urban space also had to cater to local European anxieties by facilitating police control.

As such, the neighbourhood's entangled history of public fear, policing, unrest and urban planning provides a valuable vantage point to insert spatiality into the academic debate on colonial policing. I will do so by making two inter-related arguments. First, I zoom in on the consequences of the neighbourhood's urban planning problems for practices of policing and unrest. The neighbourhood's original urban planning project confirms a narrative of how colonial urban space was designed to facilitate public order, well known amongst scholars. Yet, the analysis of this initial urban project, which was never fully implemented, opens up a more thorough understanding of spatial practices of policing and unrest. Because this urban planning project was not completely realized, police forces had to readapt policing plans, daily police patrols and military schemes to the built environment, while African inhabitants used the spatial opportunities that this partially executed urban planning scheme offered to their advantage during brawls with the police. Second, an attentiveness to spatiality can add to our understanding of the ambiguous colonial policy concerns of fear and welfare that characterized the post-war period. A spatial reading of the neighbourhood's urban planning schemes as well as military plans reveals that Kenya became the arena of welfarist ambitions while at the same time embodying many of the fears of anti-colonialist movements that emerged or became larger in the post-war period.

Ambiguous urban planning

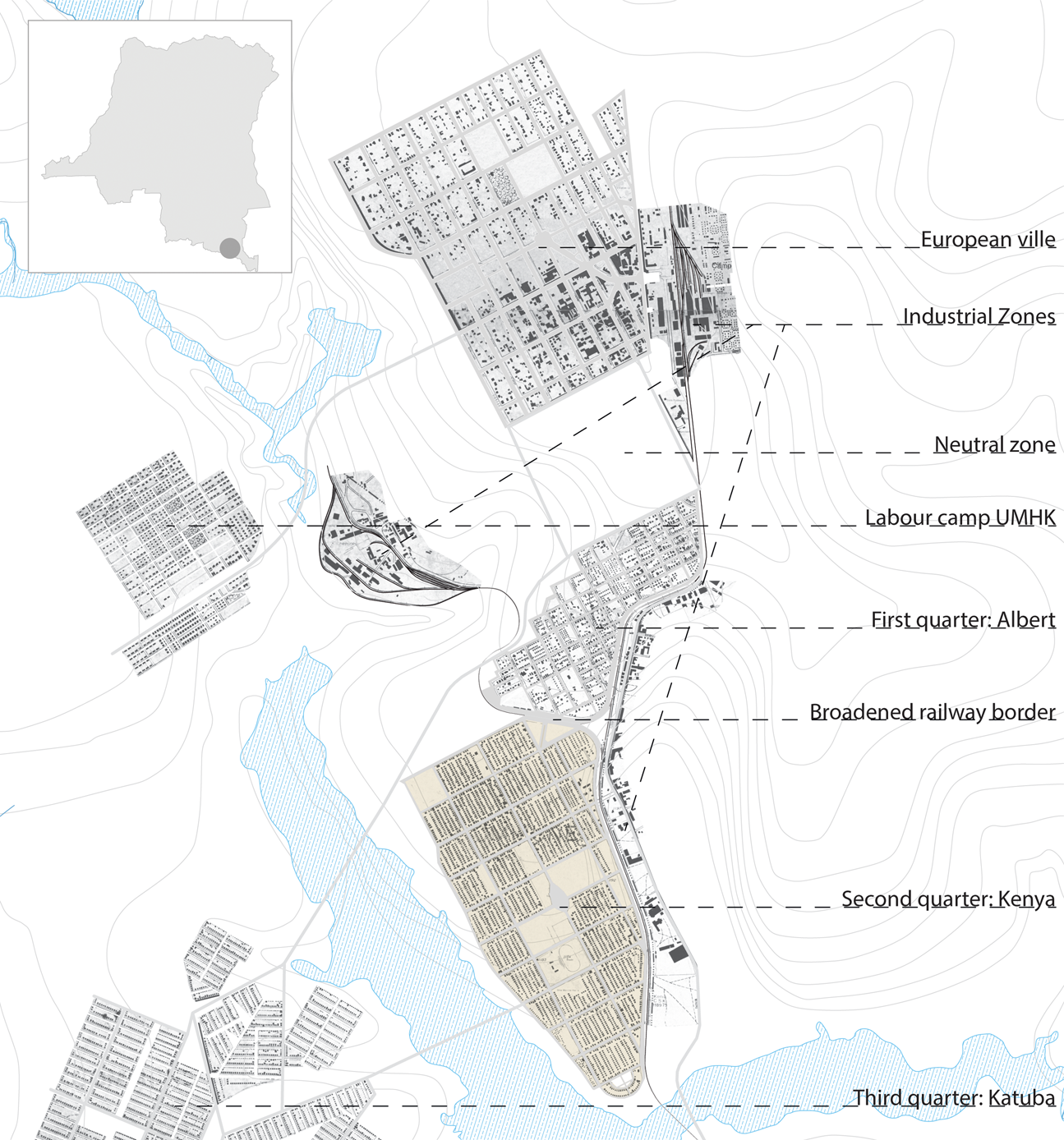

Situated in the copper-rich Katanga province, Elisabethville was founded in 1910 as a mining town and quickly became the economic heart of Belgian Congo. As mining companies such as the Union Minière du Haut Katanga attracted an increasing African labour force, the colonial authorities ordered these newly arriving migrants to settle in either the companies’ labour camps or the so-called Centre-Extra-Coutumier.Footnote 25 This African quarter, called quartier Albert, was separated from the European ville through an 800-metre-wide no man's land referred to as the zone neutre, an urban planning intervention common in colonial cities. African migrants increasingly arrived, and the quartier Albert quickly expanded. As a result, the colonial authorities decided to add a second neighbourhood to the Centre, adjacent to the old quarter but across the railway, at the then vacant site of the current Kenya neighbourhood (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Indication of main zones in Elisabethville of around 1955. Author's drawing.

Shortly after the colonial government had taken this decision, the Wall Street crisis plunged Belgian Congo's economy into a deep recession. Copper demand collapsed, and sharpened anxieties about the growing masses of unemployed Africans took an even stronger hold of the European population.Footnote 26 The colonial government changed its housing politics, aiming to exclude Congolese inhabitants who failed to present valid proof of employment from the quartier Albert. While as a result, the official African population declined by about 20 per cent, ‘a considerable number of unemployed who were determined not to return to their place of origin’ remained ‘in or near Elisabethville despite the efforts of the administration to dislodge them’.Footnote 27 Although archival records of this crisis period are scarce, it is safe to say that some, if not many, of these illegal city dwellers settled at the empty scrublands of future Kenya, setting up self-built thatched huts.Footnote 28

During the war, the site became increasingly crowded due to urban immigration. Tellingly nicknamed Nyasi – ‘straw’ in Swahili – this informal settlement lacked running water, electricity or a basic sewage system, and these dire living conditions triggered the colonial administration to search for a location for a new neighbourhood. Various proposals were put on the table, all of which were ultimately dismissed after unfruitful discussions which lasted over two years. The main problem undermining the debate was the European policy-makers’ widespread fear of large concentrations of Africans living together in a single neighbourhood. The district commissioner, A. Gille, was clear, saying that ‘the massive gathering of indigenous populations…should particularly be prevented. In a massive neighbourhood…it is clear that the words of order can spread with the speed of an electric current, and that even the smallest subversive vibration may dangerously resonate without the Police and European authorities knowing.’Footnote 29 A year earlier, these concerns had already resulted in a provincial decree that dictated that a single African neighbourhood could not shelter more than 25,000 Africans. As a consequence, urban development at the Kenya site was officially prohibited by law because it was situated too close to the existing quartier Albert. However, the proposed alternatives, often remote satellite neighbourhoods, also stirred anxiety among European policy-makers because the settlements threatened to encircle the European city.Footnote 30

Meanwhile, Nyasi was slowly turning into a bidonville as more and more African migrants were arriving and illegally building new shacks. The continuously deteriorating social and sanitary conditions in Nyasi forced the colonial authorities to forfeit two years of discussions, put aside their anxieties and circumvent the provincial decree.Footnote 31 The Urban Committee created a spatial loophole in the decree and a short-term solution to the African housing problem by broadening the vacant space of the railway that separated the quartier Albert from the future Kenya neighbourhood, which meant that Kenya could legally be considered a distinct entity. The neighbourhood – which over more than 10 years had become populated by African migrants constructing informal settlements and had become known and feared by Elisabethville's European population as the town's bidonville – would now become the stage for changing post-war ambitions.

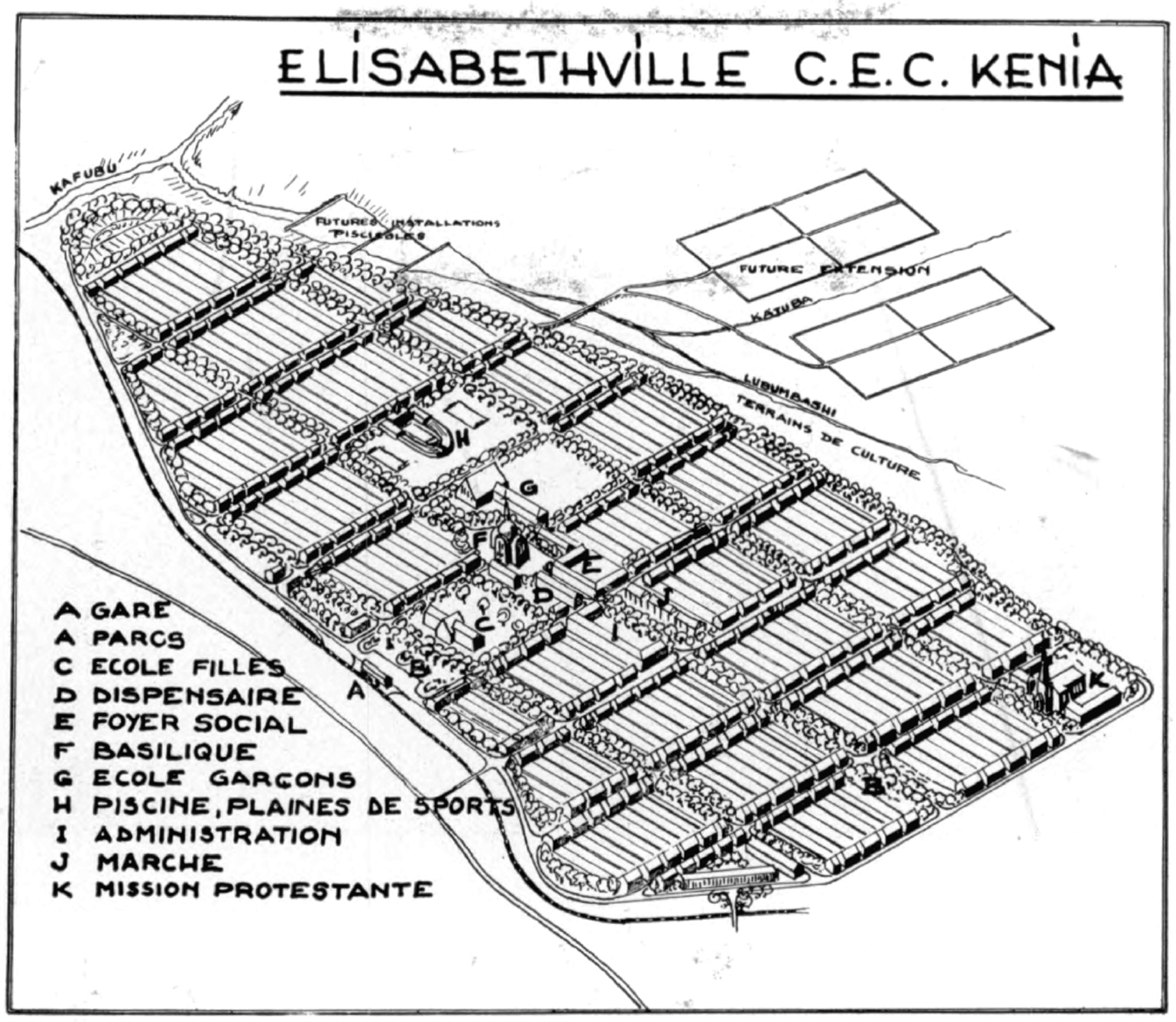

Post-war policy-making was characterized by two agendas simultaneously: security and welfare, both crucial to understand the goals of Kenya's initial urban planning project.Footnote 32 These were perhaps epitomized by a small yet fascinating sketch of Kenya that Assistant District Commissioner Ferdinand Grévisse, one of the town's most influential administrators, published in 1951 (see Figure 2). At first glance, the image may have reminded Grévisse's Belgian readership of the familiar tranquillity of a typical village in the metropole's countryside. One of the key ambitions of the new neighbourhood was indeed to function as a transitional space between rurality and urbanity. With its public greenery, free-standing and relatively spacious housing, sports facilities, schools and a social community centre, Kenya undoubtedly improved the social conditions of its inhabitants, but at the same time was to acclimatize and adapt these new migrants to western urban society.

Figure 2. 'Perspective view of the Centre-Extra-Coutumier of Elisabethville'. Unknown illustrator, published by then Assistant District Commissioner F. Grévisse: Le Centre Extra-Coutumier d'Élisabethville: quelques aspects de la politique indigène du Haut-Katanga industriel (Brussels, 1951), 459.

This is especially apparent in the neighbourhood's housing scheme, which had to make Africans arriving from the Congolese rural hinterland feel at home while also instilling new, Europeanized understandings of what an urban, ‘modern’ home should look like (see Figure 3). The parcels followed the rectangular structure of the grid, a wall separated each lot from the neighbouring one and every plot was to contain a single, free-standing dwelling. With this, colonial policy-makers aimed to recreate the homelike feeling of being in what they thought of as an African village, while also adhering to the ‘rational’ logics of European urban planning. As Grévisse explained: ‘in indigenous agglomerations, social and technical reasons seem to inhibit storied or contiguous buildings…It is therefore important to isolate the dwellings in the middle of walled yet relatively spacious parcels, giving the families the impression of being at home.’Footnote 33

Figure 3. Image indicates hierarchic grid of main avenues, streets and alleyways, the subdivision of each building block into smaller, walled-off lots, and four-room houses designed for nuclear families. AA/GG 14418, Projet de lotissement au C.E.C., Kenya, 6 Sep. 1950.

With the image, the assistant commissioner did not merely aim to inform Elisabethville's European population of the urban planning of the new African neighbourhood, but may have also implicitly tried to soothe Elisabethville's European anxieties about large African masses that would settle in the new neighbourhood. Contrary to what the illustration suggests, the longest axis of Kenya is around 2.4 kilometres long, and the initial plan counted over 9,000 dwellings for 37,500 inhabitants; yet, the image depicted far fewer houses. Similarly, Kenya's church and public green space were heavily over-scaled, both through graphic tweaks that implicitly evoked the peacefulness of Belgian rurality and created the illusion of a small, less populous and thus easily controllable community.Footnote 34 Indeed, much of Kenya's urban planning was designed along a grid pattern to allow for efficient control and observation. This was common to many colonial cities or African labour camps, as a grid was not only easy to plan and realize, but – through its hierarchical structure of broad avenues and smaller streets – also ‘facilitated police control, and broke up densely populated areas into manageable units’.Footnote 35 Street lights ensured the observability of the neighbourhood during night-time, and the police station and the administrative passport service were located at the main road leading into the neighbourhood, overseeing the most important entry point to the quartier.

Grévisse's illustration is wrought by opposing the rhetoric of welfare colonialism, peaceful European sub-urbanity, public order and disciplined urban space. It not only shows how already in 1951, colonial policy-makers tried in vain to curb the emerging reputation of Kenya as a dangerous hotbed, but also how the neighbourhood's urban planning was to realize the ambiguous agenda of the post-war period.

Policing an incomplete urban planning project

However, these ambitions were never fully realized. Because of budgetary miscalculations and failures to deploy the right funding during the correct fiscal year, several aspects of the original design crucial for the controllability of the neighbourhood fell outside financial possibilities and were never realized. Most alleyways and some of the secondary streets were never asphalted, making these inaccessible to large police jeeps.Footnote 36 Street lights were never installed along secondary streets and alleyways, drastically reducing the observability of public space, and instead of high walls, low hedges separated the different plots, but just barely.Footnote 37 As a result, each larger street block in between the avenues was transformed into an almost unified, unlit, semi-public space. Moreover, a large share of the residences was increasingly sublet and by 1957, the neighbourhood counted over 47,000 inhabitants.Footnote 38 Contrary to the original intentions of its urban planning project, Kenya had become hard to police.

Institutional challenges also impeded easy control. Belgian Congo was characterized by a ‘complex maintenance of law and order landscape’, in which several police forces operated without clearly delineated tasks or legally defined responsibilities.Footnote 39 As a result, policing often proved a complex operation, in which a ‘pragmatic pick and mix’ of varying forces and administrative bodies collaborated and sometimes clashed to ensure public order.Footnote 40 This was all the more true for Kenya, which, as part of the Centre-Extra-Coutumier, had a legal status distinct from that of the European ville and was thus officially policed by a Police de Centre. However, with only one or two Belgian commanders and around 15 unarmed Congolese officers for the ever increasing number of inhabitants, this force was heavily understaffed and utterly incapable of handling potential large-scale insurgencies. As such, in case of revolts, the Police de Centre was to be assisted by several other police forces that existed in Elisabethville at the time: the Police Territoriale, the army or Force Publique and the Corps de Volontaires Européens, a corps of European vigilantes.Footnote 41

Despite its continuous shortage of staff,Footnote 42 the Police de Centre did carry out routine tasks, such as traffic control, taking stock of stolen bikes, sanitary inspections and police patrols. Especially during the rainy season, these patrols were forced to stay on the paved and well-lit main avenues (see Figure 4). Although most of the daily reports on police patrols were not preserved, a few fragmentary series have nonetheless been kept safe in the colonial archives.Footnote 43 These accounts suggest that these police units rarely encountered substantial problems along the way. Aside from the occasional cases of public drunkenness, a recovered stolen bike, unpaid taxes or untidy lawns, the policemen left the section for ‘infractions’ and larger ‘events’ in the reports empty most of the days.

Figure 4. Depiction of trajectory of police patrols in 1956 in the Centre-Extra-Coutumier of 1956. Although these routes often changed, the police mainly stayed on the asphalted avenues, and devoted its main attention to the Kenya neighbourhood. AA/GG 17551, several documents on the Itinéraire de Service Police Territoriale du C.E.C., 1955–56.

This is not to say that such ‘infractions’ or ‘events’ never occurred; the unpaved and unlit alleyways could not properly be patrolled, and no infractions were ever recorded there, creating blind spots in the urban space. Moreover, several ‘events’ were actually registered in police reports in the archives. These were most often short-lived, involving little more than drunk taunting after curfew hours, a ruckus of spectators after an unfortunate car crash or hooligans storming the football field. Nevertheless, they shed light on how Congolese inhabitants deployed Kenya's urban spaces to their advantage during brawls with the police.Footnote 44

One procès-verbal is particularly revealing. After the 10 p.m. curfew, two European police officers and several African policemen took off on a regular curfew check at the Quatre Saisons, the nickname for the crossing of avenue de la Basilique and avenue Mitwaba, which had a bar at each corner. There, they found ‘a good number of consumers sitting at the tables of the bar…despite the late hour’. They urged them to return home, but they protested and one woman even ‘smashed a bottle to hit the [African] policemen. While we intervened, we were treated to bricks thrown by individuals hidden in between the houses bordering the avenue.’ The officers switched on their headlights to locate the hidden rock throwers: ‘In the beam of our headlights, we saw several men taking flight and hiding behind the hedges.’ The stand-off continued as they returned to the police office: ‘After covering some hundred metres, new rocks were launched in our direction which hit the right flank of our vehicle. The malicious throwers waited for us, positioned at the corners of the houses.’ While of course only suggestive, this report still provides clues about the spatial practices of protest during such brawls. The troublemakers used the unlit space between the houses and hedges as a refuge. There, they could move about freely and, without being seen, throw rocks at the police jeeps, which may have had trouble driving into the muddy, unpaved and dark alleyways.Footnote 45

Another, larger and more violent, fight occurred during a show at a temporary theatre at Kenya's market, on 13 and 14 October 1956. During the premiere, numerous people who had booked for the next day had taken a seat, since the entry tickets did not mention the exact reservation date. As the theatre was full and closed its doors, a raging crowd was left outside. The police agents, Congolese and Europeans alike, were ‘obliged to retreat, attacked by several hundreds of Congolese who threw rocks and other objects they could lay their hands on’. As the only armed members of the police, the European officers decided to resort to more drastic measures: ‘We drew our gun and firing a warning shot, we attacked the crowd, shouting to the [African] policemen to follow us.’ The crowd dispersed, but ‘from time to time, rocks were still thrown by people hidden between the houses’.Footnote 46 In a retrospective letter on the riots, the head of the Police Territoriale criticized the theatre's ‘location which was deplorable from a security point of view: The Market Square counts multiple bars, and forms the crossing point of numerous roads. Two of those are currently being asphalted and have several buildings under construction.’ This meant that ‘the protestors had ideal positions and an impressive “stock” of munition at their disposal, which they were quick to profit from. Additionally, they could hide (as indigenous persons often do well) in the mentioned buildings where, as the crowd was being dispersed, they could take refuge to surreptitiously and instantly reappear.’Footnote 47

As such, the riots during the show not only confirm the spatial practices of protest that the first report already alluded to, with rioters using the unlit, unpaved alleyways and dark spaces in between the houses as a hideout. The remark in parentheses – seemingly mentioning a fact widely known among European officials – also unveils that colonial police officers were painstakingly aware of the various ways in which Kenya's inhabitants deployed their neighbourhood's incomplete urban planning project.Footnote 48 Building on Benoît Henriet's earlier cited considerations regarding ‘everyday resistance’, attention to spatiality reveals how protests against policing also engendered instant ‘adaptation’ and ‘practices of elusiveness used to thwart the colonial schemes for surveillance and control’.Footnote 49 Yet these were still moments of violence, and even if they did not occur daily, nor were they necessarily political acts in themselves;Footnote 50 they still may have had political consequences similar to ‘everyday resistance’ by fanning the flames of Kenya's dangerous reputation.Footnote 51

Anticipating revolt: military plans for a notorious neighbourhood

Not only these riots, but also anti-colonial riots emerging across the continent caused increasing anxiety among the colonial administration. Until roughly 1957, rather than being based on actual threats in Kenya, this nervousness was mainly triggered by the presence of African masses and the confrontation of the colonial government with its own urban planning issues. However, as political independence movements mushroomed and colonial policy-makers’ confidence in the post-war ‘Pax Belgica’ vanished, fears of anti-colonial revolts increased.Footnote 52 Even more than before, the police force was preoccupied with preventing large numbers of Africans amassing in the streets and organizing nationalist revolts.

Throughout the 1950s, the various police and military forces developed three military schemes which, responding to European anxieties, outlined what to do in case of possible insurgencies. In the form of extensive maps and mission descriptions, policy-makers stipulated how police forces were to divide and separate revolting African masses, comb out Kenya and protect the European ville. In these three military schemes, colonial policy-makers sidestepped the public discourse of the communauté belgo-congolaise and – through an increasingly elaborate system of legal differentiation, advanced weaponry and temporary spatial segregation – reverted to a more rigorous racial distinction between Europeans and Africans.

The first scheme, the Plan de Trouble, was formulated during multiple meetings of a Commission Trouble, founded in 1949 by Elisabethville's local authorities anticipating the large numbers of Congolese that were migrating to the city and settling in the Kenya neighbourhood.Footnote 53 It outlined three main actions to be taken for the protection and safety of the European population in case of large-scale revolts. First, the city's European population was to move to a safe haven according to a plan d’évacuation. Second, a plan d'armement stipulated which weapons were to be given to not only military, but also civilian European officials. Third, a plan de défense specified the responsibilities of the various police forces. If a revolt broke out, colonial authorities expected it would most likely take place in Kenya. The Police du Centre, deemed unable to halt such riots, was to send policemen to the city centre on bikes to alert the chief of the Police Territoriale. However, during insurgencies, African policemen were no longer considered trustworthy informants. The plan stated that if ‘the police commissioner is informed by an indigenous policeman only that grave protests have erupted,…and if he cannot immediately find confirmation, he has to verify the situation on-site with a patrol’. The Police Territoriale, authorized to use armed vehicles, machine guns and tear gas, was then expected to hold off agitators long enough for the military to arrive. Infantry squadrons would be dropped off by truck or train at two strategically chosen points of intervention, split up the African crowd, push it back away from the city centre and set up blockades, sealing off the entrances to the European parts of town (see Figure 5).Footnote 54

Figure 5. Mapping based on excerpts from the plan de défense of the Commission Trouble: ‘The access of military trucks is made difficult by gathering indigenous Africans. The only point of access…to enter the C.E.C.-Kenya is through the passage at blocs 75/76. Examining the plan of the C.E.C. reveals the strategical assets to be gained from the fact that the Centre is practically cut in half by the railway line. Several military wagons – embarked from the station, and spreading out along the route circulaire around the passage of bloc 81 – isolate Kenya from the commercial center [Albert]. Units push back Kenya's agitators towards the Kafubu river.’ AA/GG 6182, multiple records of meetings of the plan de défense of the Commission Trouble throughout 1949. Author's drawing; symbols are based on legends used in maps of Opération Typhon, size of military groups are estimations based on convention and descriptions in Opération Typhon.

Whereas the Plan de Trouble was an operational military scheme, the second plan, Opération Tornade, was a large-scale military exercise that took place in 1957 in the four largest cities of the Katanga province.Footnote 55 The main reason behind the exercise was the fear that Congolese trade union movements, which had been on the rise in Belgian Congo,Footnote 56 would be spurred on by labour protests in Northern Rhodesia. In anticipation of possible revolts, the Congolese colonial authorities set up Opération Tornade, aiming to study ‘the challenges of maintaining and re-establishing public order in case of grave and widespread protests’.Footnote 57 Moreover, the colonial authorities deemed the modernization of the military as well as improved collaboration between the military, the various police forces and the colonial administration vital to the success of public peacekeeping. As such, an additional goal of Opération Tornade was to experiment with new communication and combat techniques, such as encryption of radio messages, aerial assistance and specialized squadrons of paratroopers.

Instructions were sent to all battalions taking part in the exercise, dividing them into allied police forces and those pretending to be Congolese rebels, who also received the location of their make-believe hideouts. During the exercises, from 1 until 9 August 1957, the allied battalions had to locate and halt these rioters, capture their arms and arrest and interrogate the insurgents. Given the fictive nature of the plan, the locations of the troops of make-believe rioters indicated the loci of European fear, as these were the places the authorities considered to be the hotbeds of resistance. Kenya was identified as the city's main concern. According to the operation's script, a band of pretend rebels was to maraud the road between Albert and Kenya. Next, the ‘unexpected arrival of 12 bn [battalions] and police forces caused the gangs to flee into the Kenya and Albert neighbourhoods’. There, the ‘agitators…find refuge and material aid’. At that point, similar to the Plan de Trouble, the battalions had to isolate Kenya from the other neighbourhoods of the Centre-Extra-Coutumier and close off access to the European city centre by setting up several blockades on the main roads and entry points. The police forces then had to systematically comb out the African neighbourhood; in French this is referred to as ratisser and quadriller, both terms that etymologically point to Kenya's rectangular street pattern that facilitated such sweeping operations. During house-to-house searches, the battalions had to confiscate all arms and munition and intercept seditious pamphlets, which were expected to be widely spread among Kenya's inhabitants (see Figure 6).Footnote 58

Figure 6. Mapping based on mission description of Plan Tornade. AA/GG 6182, description of Opération Tornade in the Centre-Extra-Coutumier of Elisabethville, Aug. 1957. Author's drawing.

A year later, Opération Typhon was organized, building on Opération Tornade. Instead of a make-believe exercise, this operation outlined effective instructions for restoring public order in Elisabethville in case of nationalist revolts. Once again, high-ranking non-military administrative personnel would be armed, receiving submachine guns at the police headquarters. Similar to earlier schemes, the various units of the Force Publique, the Police Territoriale and the Corps de Volontaires Européens were assigned different strategic points for defence, road control and blockades. However, where earlier military schemes spent more energy on controlling and ‘pacifying’ the African Centre-Extra-Coutumier, here the focus was primarily on defending the European city centre, with the roads connecting the African neighbourhoods to the city centre guarded most heavily. Efforts at public peacekeeping in the Centre-Extra-Coutumier were limited to mobile road control and the protection of important locations such as police stations. Additionally, a form of martial law would be proclaimed during Opération Typhon, redefining civil rights. When facing an insurgent African crowd, police forces were allowed to open fire after three warnings, using not only live ammunition but also grenades to halt the rioters (see Figure 7).Footnote 59

Figure 7. Based on archival maps for the military operations under Opération Typhon. AA/GG 6265, directives on Opération Typhon, 1958. Author's drawing.

The military plans described above never had to be executed. As such, more than bearing witness to the spatial tactics effectively used by police forces to subdue insurgencies, these schemes crystallize how the European fear of African riots caused a shift away from the official discourse of a communauté belgo-congolaise, towards the reconfirmation of racial distinctions. Throughout these three military schemes, several themes reoccur that confirm such redifferentiation between Europeans and Africans. First, in the changing legal environment during crisis situations, African policemen were not considered credible sources of information,Footnote 60 and European civilians were provided with arms under changing forms of martial law, which also allowed the use of live ammunition. Second, the fear of African revolts legitimized (a growing belief in) the use of increasingly sophisticated technology and techniques, such as encrypted radio communication, advanced weaponry and armoured vehicles. These ‘techniques of discipline’ created a de facto distinction between colonial police forces and African insurgents, and – by institutionalizing the possible yet planned use of rather brutal forms of live ammunition and violence against Congolese civilians – exemplified colonial ‘penal excess’.Footnote 61 Third, the three schemes not only defined a ‘keep’, an urban core that was to function as a ‘safe haven’ where European citizens could take refuge, but by extension also a ‘fringe’: an African periphery which was no longer strictly policed or securitized, but was only to be combed out, searched and infiltrated by relatively mobile squads.Footnote 62 Kenya was at the heart of this fringe, and was almost reinterpreted as ‘hostile’ territory. Strategic points of intervention, military blockades and routes for different soldier squads were set out in order efficiently to scan Kenya's urban space and isolate it from its surrounding neighbourhoods. Therefore, a spatial analysis of these military schemes suggests that Kenya's reputation of a Commune Rouge dates back to colonial times: while Kenya was never explicitly labelled as such in colonial sources, the colonial authorities already identified Elisabethville's most populous neighbourhood as the most dangerous African quarter in several policing plans. The agency of local fear throughout the three schemes is striking. If the new discourse of the communauté belgo-congolaise proclaimed by the central and metropolitan authorities was in itself already vague and superficial, the salient racial views and anxieties of local policy-makers, which myopically coincided with certain notorious urban spaces, only further impeded its implementation in Elisabethville.Footnote 63

Conclusion

During a mediatized trip around the colony in 1955, King Baudouin decided to pay Elisabethville's African neighbourhoods, including Kenya, an extensive visit. Above all, the trip was a propaganda stunt trumpeting the Belgian colonial endeavour and a pivotal moment for the government's new official discourse of the communauté belgo-congolaise.Footnote 64 Only a few days before King Baudouin drove by Kenya's Basilica, faithfully accompanied by Governor-General Pétillon and both waving at the thousands of inhabitants who had gathered along the main avenue, the monarch had fiercely argued that colonialism ‘was only justified by the well-being of the autochthonous population’, and that improving the welfare of the Congolese was an ‘imperative imposed by our sovereignty’.Footnote 65

Yet Kenya not only set the stage for a royal parade championing this new official, welfarist discourse. Its urban planning also bore witness to the ways colonial policy-makers deployed space not only to improve living conditions, but – driven by a local European fear of large African crowds and possible revolts – also to control, monitor, police and acculturate the neighbourhood's inhabitants. However, despite European perceptions of Kenya as a major hotbed of revolt, politically driven, large-scale riots never took place. Smaller forms of unrest did occur, during which the inhabitants adapted and improvised, making good use of the spatial opportunities Kenya's incomplete urban planning provided. Despite the absence of broad political insurgencies, European anxieties pushed police forces to develop various military schemes to suppress hypothetic revolts. These police reports and military schemes not only underpin the intrinsically spatial nature of actions of discipline and unrest, but also stand in stark contrast with the prevailing official discourse of a communauté belgo-congolaise that was emerging throughout the 1950s.

Kenya's urban space materialized an ambiguous agenda. The central authorities of Brussels and Léopoldville mobilized the neighbourhood as the scene of a propaganda parade festively proclaiming the communauté belgo-congolaise, anxious local policy-makers turned it into a stage of imagined ‘penal excess’ when anticipating hypothetical revolutionary riots and its inhabitants deployed the problems of the urban planning project during brawls with the police.Footnote 66 Its urban fabric was, as Brenda Yeoh put it, ‘a resource drawn upon by different groups and the contended object of everyday discourse in conflicts and negotiations involving both colonialists and colonized groups’.Footnote 67 This was especially true for actions of, and Congolese responses to, colonial policing. If scholarship on colonial policing has blossomed into a rich and interdisciplinary field of study, this analysis suggests that including an attentiveness to urban space and the built environment in the debate may unlock new and promising leads for future research.