1. INTRODUCTION

In the face of omnipresent cross-border environmental concerns, confrontational and competitive international adjudication has not proved to be an effective strategy for improving state compliance with international environmental obligations. In response, advisory and non-adversarial mechanisms were considered more appropriate for encouraging gradual compliance by parties with their treaty obligations. Consequently, almost all the major multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) have established compliance and implementation mechanisms, without prejudice to the availability of dispute settlement procedures.Footnote 1 Notable among them is the 1998 Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention).Footnote 2

Article 15 of the Aarhus Convention envisages the establishment of a committee to review state compliance with the provisions of the Convention. The first meeting of the parties (MoP) to the Aarhus Convention, in Lucca (Italy) in October 2002, adopted Decision I/7 on the Review of Compliance, establishing the Compliance Committee of the Aarhus Convention (the Committee).Footnote 3 Decision I/7 charged the Committee with, among other matters, the obligation to consider individual cases of complianceFootnote 4 submitted by members of the public, including natural persons, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and private legal entities. During 15 years of operation (from 2004 to June 2019) the Committee has become one of the most active compliance mechanisms in existence. Since its establishment, it has received 169 communications from members of the public concerning questions of compliance affecting the majority of member states and addressing key provisions of the Convention.Footnote 5

The dominant epistemic narrative surrounding the Committee portrays it as a non-judicial, optional arrangement the rulings of which are non-binding, authoritative interpretations. However, during recent years this narrative has been reconsidered, with commentators claiming that the Committee offers not just a soft remedy but has taken the path towards judicialization, and issues rulings which are binding, authoritative interpretations of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 6 The scholarly debate on the legal status of the rulings of the Committee is, to a certain degree, a response to the concern that the findings and recommendations of an advisory and non-judicial body might not have the necessary legal impact on the behaviour of non-compliant parties. This line of thinking suggests that treating the rulings as authoritative interpretations, legally binding decisions or ‘something more than soft law’Footnote 7 will ensure or strengthen the desired legal effect.

This reasoning assumes that the more the Committee is perceived as a quasi-judicial body and the more its rulings are viewed as binding, the higher will be the impact of the Committee on domestic practice. Yet, this assumption has never been empirically tested. To fill this gap this article first conducts an assessment of the impact of the rulings of the Committee related to access to justice provisions of the Aarhus Convention (Article 9). It examines how and to what degree the Committee's recommendationsFootnote 8 issued between 2004 and 2012 have been absorbed into state practice.Footnote 9 The impact assessment reveals that in fewer than 41% of the cases parties have recorded some degree of compliance with Committee rulings, whereas in 59% they recorded no progress.

Based on the empirical findings, the article then engages with the academic discourse concerning the legal binding effect of the rulings of the Committee. A holistic view of the Committee's practice and its impact offers an alternative way of evaluating the status and binding effect of its rulings. It suggests that the decision of parties to comply is determined typically by the substance of rulings as it relates to domestic circumstances rather than by the institutional character of the Committee and the binding effect of its rulings. Additionally, the use of the term ‘soft law’ in relation to the Committee's rulings denotes not only their lack of binding effect but also their future-oriented character, their capacity to create expectations about future conduct throughout the compliance process, and to inform the understanding of all parties about what constitutes compliant behaviour. The empirical insights caution against attaching too much importance to the role of binding effect in ensuring compliance.

The article is organized in seven sections. Following this introduction, Section 2 provides a general overview of the Aarhus Convention, its Compliance Committee and the normative character of its rulings. Section 3 defines the methodology of the impact evaluation, after which Section 4 describes the Committee's practice relating to access to justice. Section 5 discusses the domestic circumstances that lead to non-compliance by parties. Section 6 then explores the Committee's impact on improving state practice. Finally, Section 7 reviews the issues of judicialization of the Committee and the normative character of its rulings in light of the empirical findings.

2. THE AARHUS CONVENTION AND ITS COMPLIANCE MECHANISM

2.1. The Three Pillars of the Aarhus Convention

The Aarhus Convention is a legally binding international treaty. As at December 2019 it has 47 parties (46 states parties and the European Union (EU)). Its subject matter comprises three procedural human rights: (i) the right to information; (ii) the right to participation; and (iii) the right of access to justice.

Academic discussion of the Aarhus Convention ranges from its general contribution to the field as arguably ‘the most significant international achievement in the field of environmental rights of recent years’Footnote 10 and the implementation of various provisions of the Convention,Footnote 11 to the relevance of the Convention for other human rights treaty regimes in Europe.Footnote 12 These are but a few themes explored in the context of the Aarhus Convention's third pillar of access to justice. Special mention must also be made of the numerous implementation studiesFootnote 13 and facilitative workFootnote 14 carried out by the Task Force on Access to Justice of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 15

The right of access to justice is enshrined in Article 9 of the Aarhus Convention. It entitles the public to have access to domestic review procedures (a court of law or other independent and impartial body established by law) in respect of all matters of environmental law,Footnote 16 including (i) refusals and inadequate handling of requests for information; (ii) reviewing the lawfulness of decisions, acts, or omissions as part of the decision-making process for activities with environmental impact; and (iii) reviewing the acts and omissions of private persons and public authorities in alleged violation of national environmental laws.Footnote 17

Article 9(4) and (5) detail the merits of the review, which require the availability of (i) adequate and effective remedies (including injunctive relief); (ii) fair, equitable, and timely procedures; (iii) access that is not prohibitively expensive; (iv) review of decisions issued in writing; and (v) public access to those decisions. Article 9(5) also encourages parties to establish appropriate assistance mechanisms to remove or reduce financial and other barriers to access to justice.

2.2. The Committee as an Optional Arrangement for Compliance Review

Article 15 of the Aarhus Convention obliges the MoP to establish, on a consensus basis, optional arrangements of a non-confrontational, non-judicial and consultative nature for reviewing compliance with the provisions of the Convention. It also provides for the right of the public to submit communications.

The compliance mechanism was ‘one of the most contentious issues during negotiations’Footnote 18 and Article 15 emerged as ‘merely an enabling clause’Footnote 19 for the process of setting up the Committee. The Committee's creation turned out to be challenging because of the open-ended formulation of Article 15.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, the first MoP in October 2002 adopted Decision I/7 on the Review of Compliance, establishing the Committee and its general procedural arrangements. Over the course of its existence the Committee has developed and continuously updates its modus operandi.Footnote 21

Decision I/7 requires the Committee to consider the following cases: (i) submissions by parties on the compliance of another party or on their own compliance; (ii) referrals by the Secretariat of the Convention; and (iii) communications from the public. The Committee first convened on 17 March 2003. It meets three times a year in Geneva (Switzerland). All nine membersFootnote 22 of the last intersessional CommitteeFootnote 23 serve in their personal capacity and are legal practitioners or academics, mainly in the field of environmental law.

According to the Committee's modus operandi, following discussion of a compliance case (which includes also a formal hearing to which parties are invited), the Committee finalizes its findings and submits them to the case participants for final comment. The Committee's findings and recommendations are then provided to the forthcoming MoPFootnote 24 for endorsement of the findings and adoption of recommended actions.Footnote 25

Upon the adoption of the decisions by the MoP, the Committee starts the follow-up and monitoring of progress in the implementation of its recommendations. The Committee reports on any progress made to each subsequent MoP until full compliance is achieved. The objective of the compliance procedure is therefore not only the determination of (non-)compliance, but also the ultimate compliance of the party concerned.Footnote 26 The Committee determines the non-compliance of the party and the applicable law, and carries out further administration of the compliance case. The latter aspect is crucial for the purpose of understanding the legal characteristics of the rulings of the Committee.

2.3. The Legal Nature of the Rulings of the Committee

Decision I/7 and the modus operandi of the Committee are silent on the legal quality of the Committee's rulings. Academic commentators give different views on the issue. The prevailing interpretation of the rulings pivots upon Article 31(3)(a) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT).Footnote 27 On this basis, some authors claim that the Committee's findings of non-compliance are not legally binding, but that this ‘may be remedied by an endorsement by the MoP of the rulings of the Committee, because such endorsement may constitute a subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions’Footnote 28 in accordance with Article 31(3)(a) VCLT. Others consider that, upon MoP endorsement, the rulings of the Committee become legally binding on the contracting parties and the Convention bodies as far as the findings of the Committee may explain the meaning of Convention provisions or interpret the obligations under the Convention in such a way that the practice of a particular party constitutes a breach of those obligations.Footnote 29

Given the advisory and non-adversarial nature of the Committee, relevant scholarship also uses the term ‘soft law’ to describe the rulings of the Committee.Footnote 30 Soft law is a residual category, defined only doctrinally. To say that the rulings of the Committee are soft law is firstly to invoke their non-binding effect.Footnote 31 However, the term ‘soft law’ denotes meanings other than simply non-binding. The International Common Law (ICL) framework, for example, provides an explanatory framework to qualify the legal effects of the decisions of international tribunals and implementation bodies.Footnote 32 According to the ICL, the rulings of the Aarhus Committee could indeed be labelled ‘soft law’ because they create expectations about the future conduct of parties and interpret or inform our understanding of binding provisions of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 33

The scholarly debate on the legal character of Committee rulings has emerged in response to concern that the findings and recommendations of an advisory and non-judicial body might not have the necessary legal impact on the behaviour of non-compliant parties. This line of reasoning suggests that accepting the rulings as authoritative interpretations, legally binding decisions or ‘something more than soft law’Footnote 34 will ensure or strengthen the desired legal effects. Though these claims presume a correlation between the normative character of the Committee rulings and their legal effects, the impact of the rulings on national legal orders has never been assessed.Footnote 35 The next sections of this article address this gap in our knowledge. Firstly, the impact on national legal orders of rulings in relation to Article 9 will be assessed for the period 2004–12. In light of the empirical findings, the article will then discuss whether the normative characteristics of the rulings of the Committee, in effect, play a significant role in the decision of parties to comply with them.

3. DATA AND THE METHODOLOGY OF THE IMPACT EVALUATION

3.1. Data Sources

The impact assessment is based on primary sources,Footnote 36 namely, the Committee's rulings (findings and recommendations on compliance), decisions of the MoP, and the Committee's progress reports. Each non-compliance case was coded and scored manually.

This article's evaluation of the impact of the Committee is based on communications submitted between 2004 and 2012, regarding which Committee rulings were adopted at the fifth MoP in 2014 (19 cases in total). Fixing 2012 as the final year for the impact evaluation was preconditioned by the regularity with which the MoP convenes (every three years). As the MoP conclusions on the progress of Committee recommendations are the basis for the evaluation, measuring the progress recorded during the fifth session of the MoP in July 2014 will be possible only by comparison with the decisions of the sixth session of the MoP, which took place in September 2017. The parties’ progress can therefore be evaluated only with regard to Committee findings issued by the end of 2013 and approved by the fifth MoP in 2014.

3.2. The Approach to and the Methodology of Quantitative and Qualitative Impact Evaluation

Progressive changes in the parties’ behaviour indicate the impact of the Committee. Accordingly, this article occasionally uses the terms ‘compliance’ and ‘impact’ synonymously. Although the work of the Committee might have multiple spillover effects, the current evaluation does not consider the Committee's broader socio-economic, environmental, and political implications or influence.

The Committee's quantitative impact is measured as being the positive difference between the number of recommendations issued and the number of recommendations complied with. Respectively, a four-degree index is applied for the impact evaluation: (i) no impact/compliance; (ii) minor impact/compliance; (iii) partial impact/compliance; and (iv) full impact/compliance. If the party has made no progress under a particular communication it remains non-compliant. If it complies with fewer than half of the recommendations its compliance level will be labelled as minor compliance. If it has complied with half but not all of the recommendations it is considered to be in partial compliance. Compliance with all of the recommendations is considered to be full compliance. A numerical value is attached to each impact rate to calculate the Committee's final impact rate: non-compliant (0); minor compliance (1); partial compliance (2); and full compliance (3).

The objectivity of such an evaluation of the Committee's recommendationsFootnote 37 may not account for the significance of complying with some recommendations over others. However, any assessment of compliance based on the significance of non-compliance introduces additional biases, as it involves a subjective judgment of domestic conditions. For example, if the Committee recommended that country X and country Y establish more open standing rules for NGOs, the same recommendation for party X may be implementable without significant effort, whereas implementation for party Y may be a challenging 10-year task.

The MoP decisions that evaluate parties’ progress are considered with ‘no ifs or buts’. The only exception is communication ACCC/C/2008/31 concerning compliance by Germany. The Committee's conclusion about Germany's full compliance is oddly inconsistent with the role it attributes to domestic practice when determining parties’ compliance. The Committee provides no grounds for such a deviation but includes a statement that:

[D]ue to the short time since the ‘Aarhus amendment's’ entry into force, its application in practice is not yet known and … in the future it might examine allegations regarding the application of the ‘Aarhus amendment’ in practice or allegations regarding access to review procedures under Article 9 paragraph 3, should such cases be brought before it.

Ironically, in the same communication ACCC/C/2008/31 concerning compliance by Germany, the Committee expressly states its stance on the role of national practice.Footnote 38 I therefore include Germany among the non-compliant parties, which deviates from the evaluation method otherwise adopted in this article.

With regard to the degree of party compliance, the article also considers the directions and temporal aspects of improvements in compliance. The timing of compliance includes the period from the MoP decision on non-compliance to the MoP decision on compliance progress.

4. THE COMMITTEE'S ARTICLE 9 PRACTICE

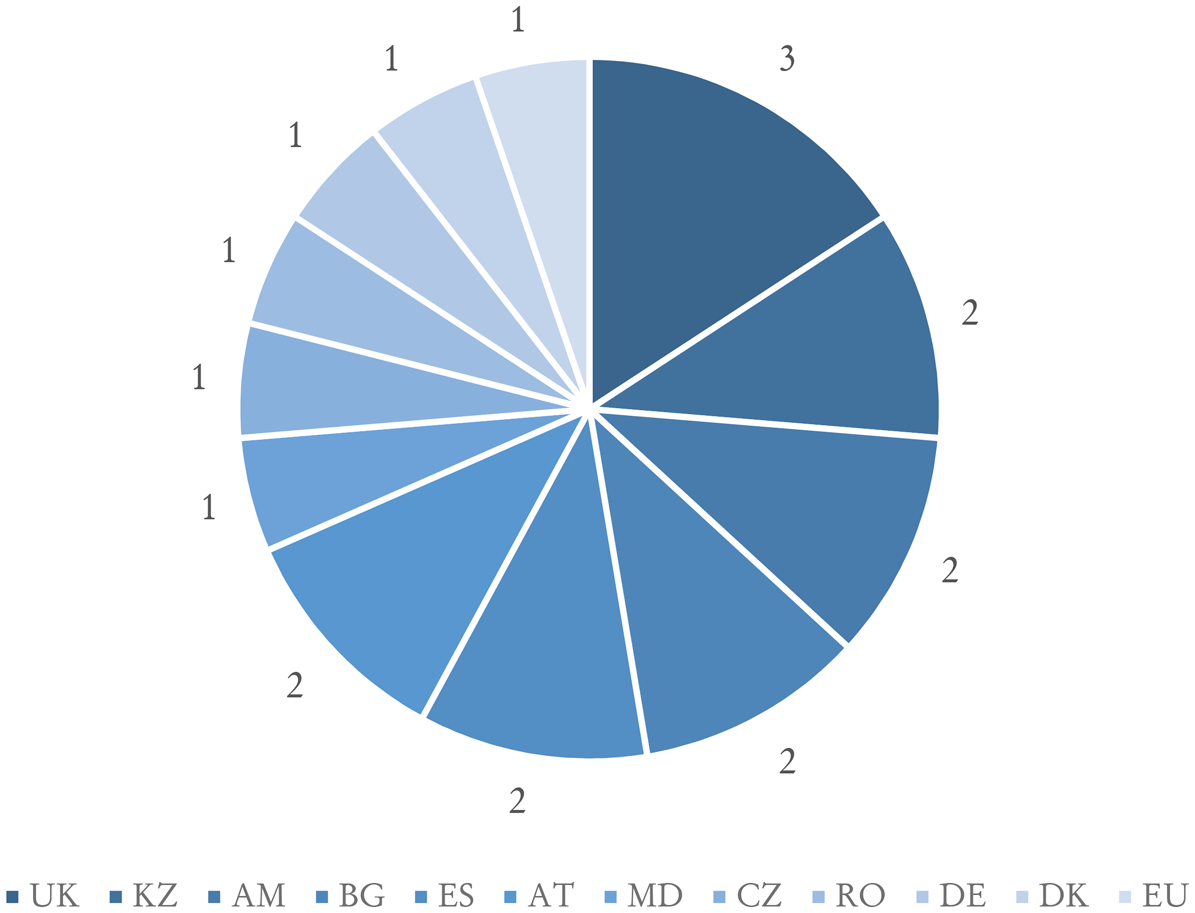

Of the 87 communications submitted for the Committee's consideration in the period 2004–13,Footnote 39 the Committee deemed (i) 60 cases (69%) admissible; (ii) 25 cases (29%) non-admissible; and (iii) in two cases (2%)Footnote 40 summary proceedings were applied.Footnote 41 In 19 (out of 60) admissible communications the Committee found 12 parties to be in non-compliance with the Article 9 provisions.Footnote 42Figure 1 below illustrates the distribution of these 19 communications among the 12 parties.

Figure 1 Distribution of 19 Non-Compliance Cases

Ten other Article 9-related communications were deemed inadmissible: in one instance for unknown reasons,Footnote 43 in five instances for being manifestly unreasonable,Footnote 44 and in four instances for lack of corroborating information.Footnote 45

The following tables list parties that have been found to be non-compliant solely with Article 9 (Table 1) or conjointly with other articles of the Convention (Table 2).

Table 1 Cases of Non-Compliance with Article 9

Table 2 Cases of Non-Compliance with Article 9 and Other Articles

The United Kingdom (UK) is at the top of the list with three cases,Footnote 46 followed by Armenia, Austria, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, and Spain, all tied with two communications each. The remaining parties each have one communication. Parties are most commonly found to be non-compliant with Article 9(4) (in 15 cases) and least often with Article 9(1) (in two early cases only).

All communications relating to Article 9 were initiated by non-state actors. Among the communicants are small or recognized transnational non-profit organizations (such as Ecoera NGO in Armenia and the Association for Environmental Justice in Spain) or their associations (such as ClientEarth and OEKOBUERO), natural entities, environmental protection associations and foundations (such as the Danish Ornithological Society, the Balkani Wildlife Society in Bulgaria, and the Environmental Law Foundation in the UK), private actors (Greenpeace UK), and others (see the distribution of communicants among the 19 cases in Figure 1).

Although the Committee provides no redress for violations of individual rights,Footnote 47 communications by the public stem mostly from unsuccessful attempts or prospective failures to exercise treaty-enshrined rights within national legal systems.Footnote 48 However, even if this does not technically constitute redress, the Committee's recommendations provide indirect remedies for members of the public, particularly given that Article 9 communications stem from domestic public interest litigation.

Figure 2 The Breakdown of Communicants in Access to Justice Cases

The average duration of case processing for the Committee is 24.5 months (median 21). The longest durations were 60 months (Germany, ACCC/C/2008/31) and 99 months (EU, ACCC/C/2008/32). The minimum was eight months (Moldova, ACCC/C/2008/30).

5. A KIND REMINDER TO COMPLY

Louis Henkin stated that ‘almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time’.Footnote 49 To an extent, this optimistic statement is true for compliance with Article 9 of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 50 Eight years of Committee practice reveal an ongoing struggle on the part of nation states to nurture a legal culture that prioritizes access to justice for the protection of the environment across the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) region.

The circumstances that led the CommitteeFootnote 51 to declare non-compliance with Article 9 vary considerably. Those circumstances are listed below, as reflected in Article 9.

Firstly, lengthy legal procedures, including denial of access to justice through which members of the public might challenge decisions permitting activities with environmental impact, led the Committee to declare non-compliance with Article 9(1) and (2) by Kazakhstan,Footnote 52 Moldova,Footnote 53 Armenia,Footnote 54 the Czech Republic,Footnote 55 and Germany.Footnote 56 In the case of GermanyFootnote 57 and the Czech RepublicFootnote 58 the Committee found there were limitations on challenging acts or omissions by public authorities or private persons contravening national environmental laws (Article 9(3)).

Secondly, in Armenia the absence of access to review procedures for NGOs and the non-availability of adequate and effective remedies led the Committee to find non-compliance with Article 9(2), (3) and (4).Footnote 59 Similar findings of non-compliance in Bulgaria were based on the unavailability of access to challenge General Spatial Plans or Detailed Spatial Plans, and final decisions permitting activities listed in Annex I to the Convention.Footnote 60

Thirdly, lack of access to a timely review procedure, no standing for NGOs to challenge acts or omissions of a public authority or private person in many of its sectoral laws that enforce environmental legislation, as well as failure to ensure that courts properly notify parties of the time and place of hearings and of the decision made, led to conclusions of non-compliance with Article 9(3) and (4) in four communications involving three parties: Kazakhstan,Footnote 61 the EU,Footnote 62 and Austria.Footnote 63

Fourthly, lack of adequate remedies (including injunctive relief), untimely and ineffective remedies for review procedures, and prohibitively expensive proceedings were the main reasons for non-compliance with Article 9(4) by Bulgaria,Footnote 64 Romania,Footnote 65 Spain,Footnote 66 Denmark,Footnote 67 and the UK.Footnote 68 The absence of appropriate assistance mechanisms to remove or reduce financial barriers in SpainFootnote 69 and prohibitively expensive costs in the UKFootnote 70 resulted in non-compliance with Article 9(4) and (5).

6. THE IMPACT OF THE COMPLIANCE COMMITTEE

Of the 19 communications on non-compliance, the impact of two was impossible to assess. Evaluation of communication ACCC/C/2008/24 concerning compliance by Spain was impossible to assess because the follow-up on progress was merged with communication ACCC/C/2009/36/ES, also relating to Spain. With regard to communication ACCC/C/2008/32 concerning compliance by the EU, the sixth MoP failed to reach a consensus and the decision was deferred for consideration by the next MoP.

6.1. Quantitative Evaluations

As of June 2019 parties remained in a state of non-compliance with nine communications out of 17 (distributed across 11 parties). Minor compliance is recorded under one communication, partial compliance with regard to three communications, and full compliance under four communications (see Table 3).Footnote 71 Overall, in 59% of the cases, parties have remained non-compliant, whereas in 41% they have recorded some degree of compliance. The detailed evaluation under each communication and the respective scoring are presented in Appendix I at the end of this article.

Table 3 Scoring of Compliance Impact

Table 3 reveals that compliance by parties in earlier cases is higher than appears in later cases. Whether this is because in earlier cases parties had more time to improve their compliance is tested by contrasting the timing with the degree of compliance/non-compliance for each case (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Per Case Timing and the Rate of Compliance

As is evidenced by Figure 3, after 2011 the level of compliance with access to justice provisions declined. For communications submitted before 2011, various degrees of compliance are observable within 36 months (with the exception of communications ACCC/C/2008/27/UK, ACCC/C/2008/31/DE,Footnote 72 and ACCC/C/2009/36/ES). Communication ACCC/C/2004/08/AM regarding compliance by Armenia is an exception, as it was only after 96 months that the party achieved some degree of compliance. That being said, in the majority of instances improvements were recorded in approximately three years.

The picture is slightly different for communications submitted after 2011. Among those cases, in only one instance – ACCC/C/2011/57/DK – was full compliance recorded in 36 months. In the remaining six instances parties remained non-compliant during the following intersessional period of 36 months. It is therefore evident that, from a timing point of view, parties performed better for communications submitted before 2011 than for those submitted from that date. The next MoP, in 2020, will be essential for gaining a more complete picture of the degree and depth of parties’ performance.

There are probably several reasons for such a time lag, which include the gravity of issues relating to compliance, the degree of change in the domestic legal culture and practices required by the recommendations of the Committee. The time lag could also relate to a possible decline in the Committee's authority or of NGOs within the national legal orders, or the politics of compliance supported by various stakeholders (including financial support mechanisms and capacity-building activities). These all require in-depth and separate statistical enquiries that are beyond the scope of this article.

6.2. Qualitative Evaluations

The impact of the Committee, considered in the context of existing literature on access to environmental justice, is indicative of an emerging and consistent practice of access to justice across the UNECE region. The Committee's communications with parties over the eight-year period have resulted in:

• reasonable time limits for judicial review in England, Wales and Scotland;

• access to courts for NGOs in Armenia to challenge environmental decisions under Article 6;

• an opportunity to challenge the acts and omissions that contravene environmental laws relating to urban planning and land use in the Czech Republic;

• improved execution of final court decisions in Moldova with regard to access to information cases;

• the establishment of timely and expeditious review procedures in Austria;

• the provision of less costly access to review procedures in Denmark; and

• standing for NGOs in access to information cases and the availability of effective remedies in a review procedure concerning omissions by public authorities to enforce environmental legislation in Kazakhstan.

Despite these positive indications, it is disquieting that the practices, policies or legislation of some parties have remained unchanged for more than six years. These instances of long-lasting non-compliance raise a legitimate concern over whether, for these parties, the compliance process serves to legitimize domestic inaction. For almost 10 years, the UK has been expected to change its costs system to prevent litigation from becoming prohibitively expensive.Footnote 73 Some eight years later, Austria still has no clear criteria for NGOs to challenge acts or omissions that contravene national laws. Inadequate and ineffective review procedures in Bulgaria have continued for seven years; and in Armenia standing criteria for NGOs, which are inconsistent with the Convention, have existed for almost 14 years. The non-availability of legal aid in Spain has lasted for approximately 10 years. Romania's untimely and ineffective remedies for review procedures concerning information requests have been on the Committee's agenda for approximately six years.

7. THE SOFT AND THE HARD CORNERS OF THE COMMITTEE'S PRACTICE

Besides offering an empirical insight into the performance of this unique treaty mechanism, the assessment of the Committee's impact in relation to Article 9 may also have implications for a number of academic debates, covering questions from the status of non-state actors in international lawFootnote 74 and the impact of judicial review on bureaucratic decision makingFootnote 75 as well as on domestic and international politics,Footnote 76 to the role of courts in maintaining the environmental rule of law.Footnote 77 However, the purpose of the assessment in this article is to build a solid empirical ground to examine the relationship between the normative characteristics of the rulings of the Committee and the decisions of parties to comply with them.

7.1. The Binding Nature of the Rulings of the Committee and their Impact

In the debate concerning the binding nature of the rulings of the Committee, two key propositions emerge. According to the first of these, nothing that the Committee does by itself may be legally binding. However, the latter can be remedied,Footnote 78 or the rulings may become binding,Footnote 79 once they are endorsed by the MoP as authoritative interpretations of the Aarhus Convention (Article 31(3) VCLT).Footnote 80 The second proposition suggests that the endorsement of the rulings by the MoP, the application of the domestic remedies rule,Footnote 81 and the procedure for considering communications are evidence that the Committee offers not just a soft remedy but is already a judicialized institution capable of generating decisions with legal effect.Footnote 82 While, in principle, this article is not opposed to these ways of thinking about the Committee and its output, some aspects of such reading are still open to dispute.

Firstly, the binding effect of decisions of the MoP cannot be inferred from their status as subsequent agreement or subsequent practice. As subsequent agreement or practice, MoP decisions are merely to be taken into account in interpreting the Aarhus Convention (Article 31(3) VCLT), together with the context (Article 31(2) VCLT), and in addition to the legally binding text of the Aarhus Convention (Article 31(3) VCLT).Footnote 83 The recommendations of the Committee endorsed by the MoP advise the party concerned about possible waysFootnote 84 of improving compliance, but are not part of the binding text of the Convention. In this respect the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has held, with regard to the International Whaling Commission (IWC), a similar treaty institution, that its non-binding recommendations, issued for the application and interpretation of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW),Footnote 85 may ‘be relevant [only] for the interpretation of the Convention or its schedule’.Footnote 86 Overall, and with few exceptions,Footnote 87 the decisions of the highest political and governing bodies of treaties are still deemed an ‘orientational aid to interpretation’Footnote 88 and outside the scope of legally binding sources of international law.Footnote 89

Secondly, the claims that the Committee offers not ‘just a soft remedy’ and has become a more judicialized institution the rulings of which, as authoritative interpretations, have the capacity to generate legal effectsFootnote 90 does not find full support either in the epistemic discourse or in the evidence of the actual impact of those rulings on state practice.

In relation to the epistemic discourse, it is notable that in 14 years only two parties – Bulgaria (ACCC/C/2011/58)Footnote 91 and the EU (ACCC/C/2008/32)Footnote 92 – explicitly disputed their obligation to implement the Committee's recommendations.

The progress report for Bulgaria under communication ACCC/C/2011/58 stated that the ongoing consultations between the various national authorities will address the Committee's recommendations, ‘taking into account not only the concerns related with compliance by Bulgaria with the provisions of the Convention, but also socio-economic and administrative aspects’.Footnote 93 On this basis, the Committee concluded that ‘the Party concerned seems to maintain the position that implementing the recommendations of the Committee is not required for its full compliance with [Article 9(2)–(3)]’.Footnote 94

The second instance is the much-discussed denial by the EU of certain parts of the Committee's reasoning under communication ACCC/C/2008/32. At the core of this denial was the EU's disagreement with the Committee's finding that the party had failed to comply with Article 9(3)–(4) because neither the EU Aarhus RegulationFootnote 95 nor the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) complies with the obligations arising under those paragraphs.Footnote 96 The EU view is that the Committee's finding that the jurisprudence of the EU courts should take a certain direction in order to comply with the Aarhus Convention amounted to unwarranted instructions to the European Court of Justice or to the General Court regarding their judicial activities.Footnote 97 The European Council refused to accept recommendations of the draft Decision VI/8f. In the view of the European Council, the principle of separation of powers in the EU prevents the Council from giving instructions or making recommendations to the CJEU concerning its judicial activities.Footnote 98 Hence, the European Council considered that it was not in a position to act upon recommendations of the Committee and to give them legal effect. At the Sixth MoP, the EU proposed that the MoP take note rather than endorse the findings of the Committee, as it normally does according to established practice. The latter suggestion was deemed unacceptable by some parties and non-state actors,Footnote 99 including NorwayFootnote 100 and Switzerland,Footnote 101 as it imperilled the long-standing practice of endorsement of the findings of the Committee by consensus. As the MoP did not reach a consensus, it deferred the adoption of the decision until the next MoP.

Considering both cases together, it appears that in its written submissions Bulgaria never raised the question of the binding effect of the rulings of the Committee. Bulgaria considered its compliance with the recommendations of the Committee possible to the extent that they do not compromise domestic socio-economic and administrative considerations. In the EU case, the position proposal drafted by the EU Commission concluded:

The Committee's findings will be submitted for endorsement to the sixth session of the Meeting of the Parties to the Aarhus Convention, which will take place 11 to 14 September in Budva, Montenegro, whereby they would gain the status of official interpretation of the Aarhus Convention, therefore binding upon the Contracting Parties and the Convention Bodies.Footnote 102

This proposal was eventually rejected by the European Council. Even the draft of the document that describes the rulings of the Committee as official interpretationFootnote 103 provides no substantiation of the reasons why adoption by the MoP would make the findings of the Committee binding upon the contracting parties and convention bodies. The EU Commission explains its position firstly on the findings of the Committee (matters of substance) and implications of the findings, and only then turns to the question of binding effect.Footnote 104 Arguably, had the EU Commission agreed with the substantive conclusions of the Committee, the argument relating to binding effect would not have been invoked. It is notable in this context that, as of 2019, the CJEU has never cited the Committee's rulings as sources of law.Footnote 105 The opinions of the Advocates General, in contrast, are comparatively generous in their engagement with the Committee's practice.Footnote 106

The above two instances indicate that in the decision of parties to accept or to comply with the rulings of the Committee, the question of binding effect is auxiliary. At the core is the (at times gradual) acceptance of the substance of the findings and the recommendations.

In relation to the actual impact (legal effects) of the rulings, the Committee has been able to ensure that in 41% of cases the parties improved their compliance record through its advisory procedure and through consistent communication, which relies on the parties’ good faith in seeking future compliance. In the remaining 59% of the cases improvements are still in progress. Against this empirical background, can we actually claim that the binding effect of the rulings is what has determined the observed impact? Would the impact have been higher than 41% had the parties perceived the Committee as a fully fledged judicial institution and its rulings as legally binding authoritative interpretations rather than non-binding recommendations? The influence of the Committee in relation to Article 9 communications neither confirms nor rejects the impact of binding effect. However, it provides insights that caution against a position which attaches overwhelming importance to the role of binding effect in ensuring compliance of the parties.

First and foremost, the MoP and the Committee rely on a range of measures to ensure compliance of the parties (Decision I/7 (37)). While the MoP is vested with the power to deploy the full complement of the measures available under the Aarhus Convention,Footnote 107 pending consideration by the MoP the Committee may, with a view to addressing the compliance issue without delay, provide advice or facilitation. Additionally, with the agreement of the party concerned, the Committee may (i) make recommendations to the party concerned; (ii) request the party concerned to submit a strategy, including a time schedule, to the Committee regarding achieving compliance with the Convention and to report on the implementation of this strategy; and (iii) in cases of communications from the public, make recommendations to the party concerned on specific measures to address the matter raised by the member of the public.

The main measure used by the Committee and the MoPs to ensure improvement in compliance in 41% of the cases was the recommendation (paragraph 37(b)). In its entire practice, the MoP has issued a caution (paragraph 37(f)) – which, together with suspension (but not withdrawal) of special rights and privileges, is considered a more confrontational means of enforcing complianceFootnote 108 – to only four parties in response to long-lasting inaction in implementing the recommendations: Ukraine,Footnote 109 Kazakhstan,Footnote 110 Turkmenistan,Footnote 111 and Bulgaria.Footnote 112 It is to be noted that the binding status of the Committee rulings, or the lack thereof, has no impact on the range of measures the Committee may take in order to influence the behaviour of the parties.

The empirical data in this article also indicates that the same party may react differently to various rulings, or even to different parts of the same ruling. For example, the UK has managed to establish reasonable time limits for judicial review in England, Wales and Scotland, whereas for almost ten years it has taken insignificant steps to change its costs orders to prevent environmental litigation from becoming prohibitively expensive. Armenia was able to open the doors of its judicial system to NGOs to challenge decisions under Article 6 of the Aarhus Convention, but the criteria for NGO standing have remained inconsistent with the Convention for years. Similarly, Austria has introduced timely and expeditious review procedures, but it has still to establish clear criteria for NGOs to challenge acts or omissions that contravene national laws.

The choices made by the parties in the above instances could be explained by a number of reasons, which include an unfavourable cost–benefit analysis of the consequences of less costly access to environmental justice; lack of capacity to address the recommendations as is required by the Committee, and so on. The choice to respond or not is based on the substance of the recommendations, and not on their binding effect. The alternative way of thinking would suggest that parties perceive one ruling or part of the same ruling of the Committee to be binding and have therefore complied, and perceive other rulings, or different parts of the same ruling, as non-binding and not subject to compliance. The latter is legally implausible as recommendations of the Committee are subject to unconditional implementation in their entirety.

The above observations lead to a final point. For all non-compliant states the Aarhus Convention is a legally binding treaty. However, as the practice of the Aarhus Convention illustrates,Footnote 113 the conclusion of the binding treaty did not constitute the end of the lawmaking process. Only through years of consistent communication, persuasion and additional lawmaking was the Committee able to develop agreed meanings and introduce them into domestic practice. Next to the advisory compliance mechanisms, the international legal order hosts a variety of international courts and tribunals. The binding force is inherent in the decisions of these international courts.Footnote 114 However, the process of compliance with the decisions of the ICJ and of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) faces challenges similar to those of the Committee.Footnote 115 A number of ICJ judgments remain unenforced.Footnote 116 The 11th Annual Report of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe states that, as of 2017, nearly half of the judgments rendered by the ECtHR since its inception 60 years agoFootnote 117 (around 7,500Footnote 118) are pending enforcement. It is important to remember that international law has no standing machinery available to enforce the decisions of courts and tribunals except where this is specifically addressed in the constituent instrument of the court or tribunal.Footnote 119 In essence, international adjudication relies on a voluntary compliance system and typically has a low level of enforcement authority.Footnote 120

7.2. The Impact of the Rulings of the Committee as Soft Law

Within the analytical framework of ICL the rulings of the Committee constitute soft law. They are more than just acts of the application of law as they also create expectations about the future conduct of parties, and interpret or inform our understanding of binding provisions of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 121

The rulings of the Committee create expectations about future conduct because, next to being acts which determine a party's non-compliance, they also launch a legal process which ceases only when full compliance by the party is achieved.Footnote 122 While considering cases of non-compliance, the Committee has also been engaged in legal interpretation, at times acting as lawmaker.Footnote 123 Following the analytical framework of ICL, under which the Committee develops the provisions of the Aarhus Convention, these new meanings become part of the binding law of the Convention. In fact, the Committee quite consistently applies its previous interpretations of Article 9 provisions in deciding subsequent cases.Footnote 124 Meanwhile, determination by the Committee of one party's non-compliance also informs the remaining parties that a particular set of circumstances leads to non-compliance, and parties may thus prevent the occurrence of similar situations within their legal systems.

Potential objections against presenting the rulings of the Committee as soft law may come from those who consider these types of document from international institutions (court rulings, resolutions, and so on) to be an application instead of an interpretation of law. This thinking suggests that the Committee's rulings and MoP endorsements thereof are only legal facts, originating from the pre-existing rule in the system (Aarhus Convention) and not legal acts emanating from the direct will of the international lawmaker – namely, parties to the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 125 In the distinction between legal actum and legal factum in civil law traditions, there can be no soft law Committee rulings because ‘softness results from the will of the subjects of the international legal order’ (and therefore concerns only legal acts).Footnote 126 Hence, even if they have possible legal effects, the Committee's rulings and the MoP's endorsements are not law. Rather, they may be classified as applications of the law.

While remaining open to different perspectives on the rulings of the Committee, it should be acknowledged that when, for example, the Committee declares Austria's non-compliance with Article 9(3)–(4) under communication ACCC/C/2011/63, it goes beyond applying the provisions of the Convention and also launches a compliance assurance process for Austria.Footnote 127 In such instances, rulings of the Committee also become future-orientated acts,Footnote 128 predominantly dealing with systemic rather than transitory non-compliance issues.Footnote 129

To summarize, the use of the term ‘soft law’ in relation to rulings of the Committee denotes meanings and effects (namely, its orientation to the future, expectations about future conduct, informing the understanding of the parties) that are not captured by the term ‘act of application of the law’. Defining the rulings as soft law not only signifies that they are non-legally binding recommendations on the application of the law; it also means that the rulings of the Committee are acts that initiate a legal process towards the gradual unfolding of the provisions of the Aarhus Convention into domestic practice, that they give new meaning and further develop the provisions of the Convention, and that they also inform all parties about the kind of domestic practice that may result in non-compliance under the Aarhus Convention.

8. CONCLUSION

Over the course of eight years and throughout the 17 communications relating to access to justice evaluated in this article, in eight instances (41%) the compliance dialogue secured varying degrees of improvement in national practice. Under nine communications (59%), improvements are still in progress.

The emerging picture is subject to various interpretations depending on the position taken. On the one hand, it is hard to imagine a more reasonable regional dialogue towards the establishment of a practice of access to justice in environmental matters than the compliance mechanism. On the other hand, the explicit and long-lasting non-compliance of some parties continues to challenge the authority of the Aarhus Convention, including its institutions. Particularly disquieting is the slowing down of the performance of parties under communications submitted after 2011.

Successful dialogue between the Committee, the parties and non-state actors has begun to foster a fairly new culture of public interest litigation for environmental protection across the UNECE region, whether through the broadening of standing rules, relaxation of costs regimes, or improvement in access to courts. However, for the UNECE region, evidenced by the empirical analysis in this article, public interest litigation for environmental protection has not yet become an established and widespread practice. This is demonstrated by the number and nature of communications submitted to the Committee. Only further influence of the Committee at the same pace and to the same degree may lead to the emergence of a European culture of public interest environmental litigation. However, the Committee's continually high caseload along with a slowdown in the pace of its influence also indicate that it is still too early to declare the internalization of the access to justice provisions by the parties to the Convention.

Despite the more recent claims that portray the Committee as a more judicialized institution and its rulings as binding, this article has demonstrated that the role of normative characteristics of the Committee and its rulings should not be exaggerated in the process of ensuring compliance by parties with their obligations under the Aarhus Convention.

APPENDIX I

The Impact Assessment