1. INTRODUCTION

In 2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced China's intention to develop the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI routes will connect over 60 countries, accounting for 60% of the world's population and a collective gross domestic product equivalent to 33% of the world's wealth.Footnote 1 Accordingly, China has now rapidly become one of the world's largest overseas investors and has increasingly encouraged more companies to operate abroad. With the rise of overseas investment by Chinese companies under the BRI, it is important to consider the impacts of such investment overseas. This is an urgent issue given that China's foreign investment significantly is concentrated in developing countries, which often lack the strong legal and regulatory institutions required to protect social and environmental justice. Some Chinese foreign investments have been concentrated in environmentally sensitive areas and carbon-intensive infrastructure projects.Footnote 2 To ensure the sustainability and green credentials of Chinese foreign investment and address criticism from the international community, there is a need to improve the investment practices of Chinese companies under the BRI.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is crucial for improving the behaviour of Chinese companies overseas. The concept is conventionally understood as voluntary and market-based corporate behaviour without direct government involvement. The manner in which CSR has been developed in China challenges this mainstream understanding. Over the past decade China has demonstrated a state-centric approach towards promoting CSR. This may be understood as a complementary regulatory approach to address the limitations of a fully market-based CSR model. While existing studies have already noticed the state-led approach to CSR in China, they focus only on its application in advancing domestic CSR practices rather than such practices overseas.Footnote 3

This article aims to fill this gap in the academic literature with an examination of China's CSR policy development in the context of a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) infrastructure project in Africa, which is a central destination for China's BRI. It aims to enrich the knowledge of China's state-centric CSR by contextualizing Chinese investment in Africa and it addresses the following questions. How has the state-centric approach been applied to promote Chinese sustainable investment overseas? What are the features, strengths and limitations of the state-centric approach in advancing the CSR practices of Chinese companies in Africa? What are the policy implications that emerge from the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) case in Kenya?

To address these questions, this article analyzes China's regulatory framework for CSR overseas, and discusses the necessity to promote sustainable investment in Africa. It pays close attention to the development of China's CSR in Africa – the major investment destination of the BRI. The article examines legal documents on the promotion of sustainable investment by the Chinese government between 2007 and 2017. Taken together, these documents provide a framework that reveals how the Chinese state intends to shape the social and environmental performance of all Chinese companies overseas. It also gives an in-depth analysis of the SGR project in Kenya. The findings are based on in-depth interviews, an extensive review of publicly available documents, and field visits to project sites between September 2016 and February 2017. Through the policy analysis and the empirical case study, the article analyzes the strengths and limitations of the state-centric approach in advancing CSR by Chinese companies overseas. The findings of this article indicate the importance for the state in promoting China's sustainable investment overseas. The Chinese government uses its various institutional connections to create a stronger awareness of policy objectives and provide incentives for policy implementation. Under state guidance, Chinese companies are increasingly following global trends in adopting socially responsible business practices.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 outlines state-centric CSR as a conceptual framework, and introduces the emerging state-centric CSR in China by reviewing recent sustainable investment policies. It then analyzes the potential challenges and opportunities for applying China's state-centric CSR approach abroad and the differences between domestic and overseas implementation of the approach. Section 3 puts China's state-centric approach in a more concrete geographical context – Africa – and examines the state's motivations in promoting the CSR performance of Chinese companies in Africa. Section 4 analyzes the challenges and limitations of the current state-led approach and relevant policies in the African context. Section 5 uses the case study of the SGR project in Kenya to identify the strengths and limitations of the state-centric approach in advancing Chinese companies’ overseas CSR. This is achieved mainly through the analysis of the key actors in the implementation of the SGR project, including the Chinese government, China Exim Bank and the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), the Kenyan government, and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and media. Section 6 summarizes the key findings of the article.

2. THE EMERGENCE OF STATE-CENTRIC CSR IN CHINA

2.1. The Development of CSR

CSR is typically understood as voluntary corporate action that goes beyond minimum regulatory compliance.Footnote 4 The development of CSR theory reflects a paradigm shift from one that protects the economic interests of shareholders to one that increasingly takes into consideration stakeholders’ interests as well as global social welfare. In the context of environmental and social protection, CSR essentially suggests that companies should pay greater attention to environmental protection, human rights, anti-corruption measures, and the interests of non-traditional stakeholders such as employees, consumers, and local communities.Footnote 5 The traditional understanding of CSR is that it is market based and driven by non-governmental actors. Companies voluntarily engage in more socially responsible activities because of various considerations, such as reputation, long-term profitability, and pressure from shareholders and consumers.Footnote 6 Under a market-based approach, civil society and the media are often decisive in influencing market reactions and public perception. Although governments may adopt incentives to motivate companies to conform with legal requirements, much of the impetus towards responsible business practice depends on self-regulation by companies and their engagement with investors and other stakeholders.Footnote 7 However, voluntary CSR frameworks cannot force companies to make unprofitable but socially beneficial decisions. In addition, market-based approaches to CSR often cannot effectively address opportunistic behaviour such as free riding, which can undermine the effectiveness of CSR.Footnote 8

The institutional constraints in developing countries highlight the need for alternative approaches to market-based CSR. Scholars have revisited the role of government in promoting CSR.Footnote 9 Government involvement in driving CSR has been proposed as a complementary way to promote it.Footnote 10 Zadek, for instance, highlights the engagement of governments with CSR frameworks as a new and crucial stage in the development of CSR.Footnote 11 Over the decades, governments have joined other stakeholders in strengthening CSR in various fields, such as public welfare and environmental protection.Footnote 12 As McBarnet suggests, CSR is a field where market forces, voluntary action and legal obligation intertwine.Footnote 13 On the one hand, CSR practices are enforced by civil society and consumer activism; on the other hand, regulation, policy making, standard setting, and other forms of governmental facilitation of CSR also influence the voluntary adoption by companies of responsible business practices.Footnote 14

More modern understandings of CSR in the western context are that CSR is no longer purely voluntary, but is subject to stronger pressures from the government under the social licence to operate.Footnote 15 It is often argued that states have an obligation under international law to regulate overseas companies to prevent and remedy violations of human rights.Footnote 16 State regulation, such as regulation by the Canadian government, is an important tool for addressing human rights concerns arising from the operations of multinational companies in global mining.Footnote 17 Clearer and more frequent endorsement of business responsibilities by international instruments, such as guidelines issued by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), have also promoted the role of states in overseeing respect for human rights by the private sector.Footnote 18 Financial institutions, too, are having greater universal influence in promoting the private sector's sustainable financing.Footnote 19 International norms, together with the changing role of states, help to further ensure the implementation of CSR.Footnote 20

2.2. China's State-Centric CSR Approach

The limitations of the conventional market-based approach and the emerging role of states suggest a possible alternative, ‘state-centric’ approach to CSR, as practised in China where the government and its affiliated institutions are the primary actors in driving and framing CSR initiatives. The state-centric CSR framework was originally proposed to explain the domestic CSR behaviour of Chinese companies.Footnote 21 While some studies in China have commented on the state-centric approach, they have focused on its application to Chinese domestic rather than overseas CSR practices.Footnote 22 China has rapidly become one of the world's largest overseas investors, with investments concentrated heavily in infrastructure projects under the high-profile BRI. Its grand infrastructure projects in Africa, for instance, have sparked controversies arising from their community and environmental impacts. Considering the mounting international scrutiny and criticism of the environmental and social performance of Chinese companies, it is important to examine how the state-centric approach can be extended to the CSR behaviour of such companies overseas. This article, therefore, discusses the strengths and limitations of the state-centric approach in the context of Chinese foreign investment.

China is a leading practitioner of the state-centric CSR approach. Its development of CSR has several distinctive characteristics that set it apart from those of other countries. Although the models of CSR in the western context are no longer purely voluntary but are subject to stronger pressure from governments, CSR development in OECD countries is still far more strongly driven by market, shareholder and stakeholder pressures, and includes a wide spectrum of market-based CSR practices.Footnote 23 It relies more on voluntary measures and private standards for responsible investment, and less on governments. Governments play an indirect role in regulating companies, such as through transparency and requirements for the reporting of corporate activities.

In the context of Chinese CSR, however, national and subnational government actors are not only regulators but also companies’ most important stakeholders in advancing CSR. It can be understood as a complementary regulatory approach to address the limitations of a fully market-based approach of CSR.Footnote 24 The state-centric approach is closely associated with China's authoritarian political system and the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) broad roles as ‘intermediary, as sponsor or patron of civil society and business organizations, and as controlling shareholder of state enterprise’.Footnote 25 The Chinese government has political, social, and economic motivations to promote CSR and develop a more environmentally and socially sustainable framework.Footnote 26 In this context Chinese governmental authorities are able to advance CSR directly by using their capacity as legislator, regulators, enforcers, and market players.Footnote 27 Furthermore, as Chinese SOEs are linked to state organs through institutionalized channels and political practices, their performance and behaviour are closely intertwined with the political interests of the government. Lin and Milhaupt observe that the Chinese central government exercises great power over the selection and compensation of top managers of SOEs.Footnote 28 As top managers of Chinese SOEs usually hold important positions in the government concurrently, the CCP is also functionally well situated to monitor personnel in SOEs.Footnote 29 Close institutional, relational, and bureaucratic ties between the state and the business community give the government the power to influence the CSR programmes of Chinese SOEs.

Under the state-centric CSR approach, the key roles of the Chinese government include mandating, facilitating, and endorsing the Chinese practice of CSR.Footnote 30 Theoretically, the Chinese government can endorse and raise awareness of CSR through direct policy statements, information dissemination, training, and educational programmes. It can facilitate CSR practices through capacity building, drafting voluntary guidelines and certification systems, auditing and monitoring, standard setting, establishing financial and reputational incentives, and providing government-coordinated services.Footnote 31 It can also facilitate CSR by enacting regulations to implement multilateral conventions and guidelines. It can mandate and promote the adoption of CSR through legislative and regulatory enforcement to advance the CSR practices of Chinese companies – for example, the government could require mandatory sustainability reporting of companies’ codes of conduct. Finally, it can partner with businesses and civil society in designing, implementing, and monitoring programmes to advance and promote CSR practices. This would require the government's direct collaboration with companies, participation in international organizations, and involvement in dialogues about CSR with other stakeholders.

2.3. Strengths and Limitations of State-Centric CSR

The state-centric approach to CSR has some strengths. It fosters and enhances positive communication between the Chinese government and the business community. It may also improve compliance by Chinese companies with CSR policy initiatives in practice. Like formal regulation, state-backed CSR instruments ‘signal the government's endorsement of CSR practices’, which can have a stronger indirect effect on social norms than the CSR policies made by companies themselves.Footnote 32 In addition, the government's all-encompassing control over the economy and society has advantages in nationwide policy formation and implementation. It may help ‘regulatory convergence’ across companies.Footnote 33 This is impossible under the traditional CSR approach where the scope of CSR policy is only company based.

Moreover, as the Chinese government can influence many dimensions of corporate operations through its administrative control of the issuing of licences to operate, it can effectively motivate companies to adopt relevant CSR guidelines.Footnote 34 The government can mobilize various institutional, managerial, and financial resources to protect its political image when harmful social and environmental accidents occur overseas. In this way, the Chinese government can more effectively monitor and advance CSR directly and enhance the implementation of CSR initiatives. The state-centric approach thus fills some important gaps in addressing the incapacity and unwillingness of companies to genuinely tackle social and environmental problems under a conventional market-based CSR approach.

However, there are limitations to the state-centric CSR approach. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the continued commitment, resources, and influence of the Chinese government. It requires extensive governmental resources and financial input to develop, administer, and enforce CSR programmes. The viability of state-centric voluntary tools depends also on the capacity and will of state agencies and government officials. Corruption, lack of transparency and competence of government officials could all undermine the legitimacy of the Chinese government as an advocate of CSR.Footnote 35

In light of the fundamental tensions between economic growth and environmental protection,Footnote 36 protective measures may be eroded by ineffective implementation overseas as a result of local protectionism and the prioritization of economic development goals in policy making in host countries. A series of guidelines issued by the Chinese government to guide sustainable investment overseas of its companies could be used as a way to justify state legitimacy. Because of the voluntary nature of the guidelines, the concern is that they are not necessarily inimical to substantive performance,Footnote 37 especially considering that some African countries have weak rule of law and legal institutions or high levels of corruption. Uncertainty about actual implementation also raises the possibility that the guidelines would be merely symbolic in nature. When the guidelines cannot effectively be implemented, they will do little to solve the problem, but will only mask weak performance and limit state accountability.Footnote 38

In addition, the state-centred approach arguably ‘constrains the space for public participation and civil society leadership in CSR’.Footnote 39 Unlike the CSR practices of western companies, which are driven almost entirely by robust civil society organizations and companies themselves,Footnote 40 the CSR practices of Chinese SOEs are driven mainly by the Chinese government through strong control over civil society organizations and via the companies’ close political and economic connections with the government.Footnote 41 Civil society and media in China are strictly controlled by the government and have far less power in influencing public opinion. Even though the Chinese government also sees ‘harnessing the influence of international standard-setting organizations, economic institutions, trading partners, internal management, and civil society’Footnote 42 as important mechanisms of informal social control, the country's state-centric CSR approach towards civil society remains conservative compared with CSR strategies in democratic countries.

2.4. How Does the State-Centric Approach to CSR Work Beyond Chinese Borders?

The state-centric CSR framework was originally proposed to explain the domestic CSR behaviour of Chinese companies. As more and more Chinese companies invest overseas, with corresponding impacts on local communities in host countries, there is a need to examine how the application of the state-centric CSR approach influences the overseas CSR behaviour of these companies.

China's ‘Going Out’ policy provides the context and legitimacy for its companies to invest overseas. It aims to encourage and support Chinese companies in their foreign investment to solve problems of over-capacity in production within the Chinese economy and to facilitate industrial structural adjustments.Footnote 43 The ‘Going Out’ policy involves various procedures, administrative approval, outflows of funds, and inflows of capital.Footnote 44 Among all stakeholders, the Chinese government and state-controlled financial institutions are the major actors in influencing the process of Chinese corporate investment overseas. Specifically, before a Chinese company ‘goes out’, it usually needs to obtain administrative approval from the Chinese government and capital from a financial institution. In most cases, the financial institution is a state-owned bank, such as China Exim Bank. The Chinese government uses a wide range of substantial state finance to facilitate the foreign investment activities of Chinese companies. Hence, the Chinese government and its state-controlled financial institutions are vital stakeholders in ensuring the overseas operation of Chinese companies. In addition, the government promulgated various regulations and policies between 2007 and 2018 on promoting sustainable overseas investment by the Chinese government, companies, and financial institutions.Footnote 45

In both Chinese companies and financial institutions the ownership structure exerts significant influence over governance practices. Most Chinese companies that engage in large-scale overseas infrastructure projects are SOEs, and the financial institutions providing support for the projects are state-owned policy banks. The Chinese government plays a major role in the supervision and governance of the state-owned banks, including influence over its lending practices to SOEs.Footnote 46 The government exercises direct and indirect control over SOEs ‘not only as controlling shareholder, but also through personnel management, cross-shareholdings, and direct bureaucratic oversight’ by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).Footnote 47 As Chinese SOEs are organized as ‘networked hierarchies’, they are linked to state organs through institutionalized personnel channels.Footnote 48 The interaction among the Chinese government, Chinese overseas SOEs, and state-owned banks provides the conditions for the implementation of the state-centric approach.

A regulatory overview of China's state-centric approach to CSR abroad

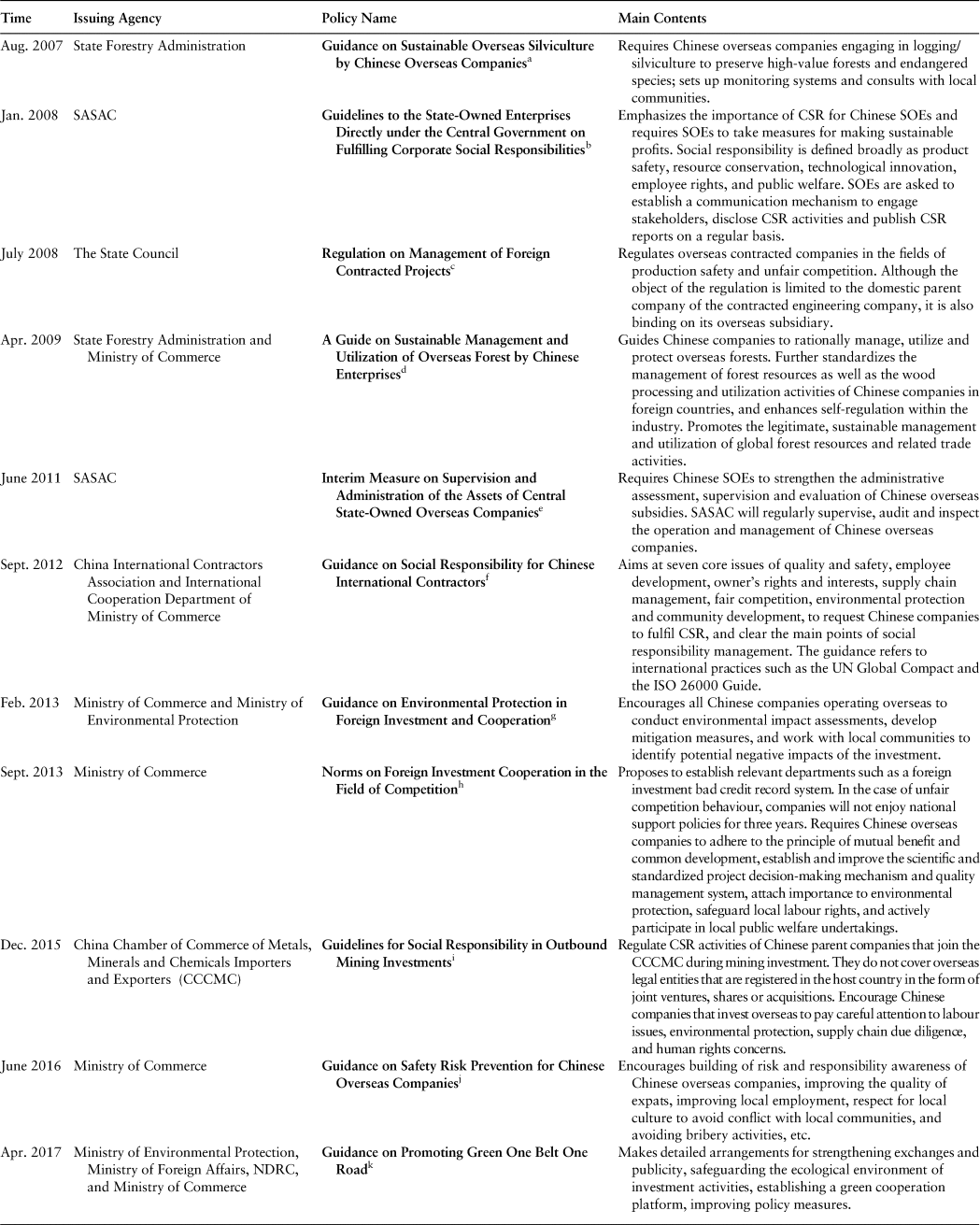

As China has rapidly evolved into one of the world's largest overseas investors, CSR is crucial for its companies to operate sustainably overseas. The Chinese government has promulgated many overseas sustainable policies and CSR guidelines to gain a better international reputation and to ensure the success of overseas investment projects.Footnote 49 Since 2006 the Chinese government has issued a series of guidelines and policies on overseas environmental and social protection to highlight its role in promoting Chinese companies’ CSR between 2007 and 2017. The policies are listed in Table 1 (in the Appendix at the end of this article) titled ‘State-led Initiatives regarding the Overseas CSR Performance of Chinese Companies’. Various agencies have been involved in the regulatory process; these include China's State Council, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministries of Commerce and Foreign Affairs, and other state entities such as the China Export Import Bank. Taken together, the various policy documents provide a framework that reveals how the Chinese state intends to shape the social and environmental performance of all Chinese companies overseas.

As a large part of China's foreign investment involves infrastructure contracts, the Chinese government has issued specific CSR guidelines in this area. In 2008, for instance, the State Council issued the Regulation on Management of Foreign Contracted Projects.Footnote 50 Consistent with the State Council's regulatory move, the China International Contractors Association in 2012 issued its Guidance on Social Responsibility for Chinese International Contractors, which recommends that suppliers and subcontractors should incorporate ‘ethics and environmental protection into procurement and subcontracting contracts’.Footnote 51 Consequently, Chinese companies have started to enact internal rules for suppliers and contractors: for example, the China Petrochemical Corporation has issued a Notice on Further Strengthening Contractor Management Work, which requires project contractors to comply with relevant laws and regulations and meet relevant qualification requirements.Footnote 52

The challenges of applying state-centric CSR abroad

The government's continued dominance in the political, economic, and social spheres in China creates conditions that are conducive to the emergence of a state-centric approach to CSR. However, the application of this approach in other national or geographical contexts presents many challenges, and some opportunities, as a result of the different cultural, economic, political, and legal dynamics of host countries.

Firstly, the institutional environment of the host country is an important variable in the effectiveness of the state-centric approach, as the Chinese central government has little control over the political, economic, social, and legal conditions in the host country. China's state-centric approach may be welcomed by host countries that share similar institutional qualities. However, it may encounter suspicion in host countries with democratic institutions and a tradition of active civil society involvement. As noted, an important limitation of the state-centric approach is the lack of engagement with civil society. This limitation is palpable within China as the social sphere is tightly state-controlled. However, this particular weakness of the state-centric approach may be alleviated when state-centric CSR travels overseas, particularly in host countries with active civil society monitoring, which might help to enhance the effectiveness of state-centric CSR.

Secondly, depending on the type of ownership, geographical distance may loosen state control over Chinese companies overseas. The Chinese government may not exercise the same level of control over its companies overseas as it does over its domestic companies. This loss of control is more salient in privately owned companies. While the government does not exercise control over privately owned companies through ownership, it can still influence many dimensions of the domestic operations of Chinese private companies through various regulatory measures, such as licensing and inspections.Footnote 53 However, privately owned companies in China have weaker ties with Chinese government bodies in host countries than do Chinese SOEs.Footnote 54 Since the former have much less contact with such government bodies and rarely receive government-linked financial support, there are substantial challenges in holding these private companies accountable and orienting them towards more responsible business practices.

This section has offered a brief overview of the potential challenges and opportunities of applying China's state-centric CSR approach overseas and the differences between the domestic and overseas implementation of the approach. The following section will situate this discussion in a more concrete setting to analyze the opportunities and limitations of China's state-centric approach in Africa.

3. WHAT ARE THE INCENTIVES FOR CHINA TO ENGAGE IN CSR IN AFRICA?

This section examines the application of China's state-centric approach to CSR in Africa. Africa is a central destination of the BRIFootnote 55 and is thus an important example to illuminate the impact of Chinese investment overseas. China's foreign investment in Africa has grown ‘even faster over the past decade, with a breakneck annual growth rate of 40 percent’.Footnote 56 Chinese companies arguably make significant contributions to the economic and social development of African countries, especially by improving infrastructure, upgrading industries, creating jobs, and transferring technology.Footnote 57At the same time, Chinese investment and industrial activities in Africa have triggered controversies over their social, economic, and environmental impacts.Footnote 58 Accordingly, the Chinese government and its affiliated entities – including SOEs and state-owned banks – may be motivated to promote CSR in Africa. This section analyzes the possible reasons for Chinese companies and financial institutions to promote sustainable investment in Africa.

3.1. Reducing Conflicts and Litigation Risks

Environmental and ecological conditions in Africa are complicated and volatile. Some areas have fragile and sensitive ecosystems that are vulnerable to severe natural disasters such as sandstorms, droughts, and erosion.Footnote 59 These climate-related events are compounded by local environmental degradation caused by foreign investment, such as habitat loss, pollution, and deforestation.Footnote 60 Chinese infrastructure construction projects in Africa – which focus mainly on the construction of railways, container ports, and power plants – could further exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and introduce new risks. As important actors in international environmental governance and addressing global climate change, Chinese companies face international scrutiny to improve their environmental performance overseas.Footnote 61 To avoid conflicts arising from negative environmental and social impacts, Chinese infrastructure companies have incentives to develop infrastructure in African countries in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible way.

Improvement in the environmental and social behaviour of Chinese overseas companies can also help to avoid regulatory breaches in host countries. The traditional impression of Africa's environmental governance is that many African countries attach a low priority to environmental and social protection, and have poor records in countering corruption. In practice, the approach of African states to environmental protection varies.Footnote 62 Some countries have ‘impressive legislation in place while others are lagging behind’.Footnote 63 The protection of the environment has become a particularly high priority for African governments as a result of the negative environmental impacts caused by foreign investors.Footnote 64

To promote sustainable development, many African countries have committed to transforming their consumption and production processes and practices by embedding sustainable development into their legal systems in order to protect natural resources and the environment for current and future generations.Footnote 65 This shift towards a green economy has been reaffirmed by many different African initiatives, and there is now a growing awareness of the importance of this transition.Footnote 66 In addition, in response to the Paris Agreement,Footnote 67 many African countries require foreign investors to reduce their industrial carbon emissions.Footnote 68 The regulatory authorities of host countries in Africa may continue to intensify their monitoring, assessment, and management of environmental and social considerations. Stricter environmental regulations and policies therefore pose a threat to the survival of Chinese high-polluting infrastructure projects overseas,Footnote 69 and this will in turn affect the financial institutions that have provided loans to these companies.

In addition, Chinese companies may face pushback for their lack of attention in protecting the interests and welfare of local communities in host countries. The historically unequal distribution of resources, revenues, and compensation – as well as communication gaps and misunderstandings between the government, companies, and local communities – have exacerbated the political, cultural, and economic marginalization of local communities, and triggered conflicts.Footnote 70 Chinese overseas companies often face complex social risks and challenges in host countries, such as a lack of social acceptance or inclusiveness. They may display inadequate regard for labour and working conditions, land acquisition and compensation, localized operations and management. Moreover, Chinese companies generally tend to invest more energy in building relations with African governments than in responding to the economic needs of landowners.Footnote 71 These actions may further destabilize relationships and cause new internal divisions over access to wealth, creating a vicious cycle that ignites, prolongs and exacerbates conflicts between interested parties.

Given the increasingly strict domestic regulation in host countries and potential social conflicts precipitated by investments in host countries, Chinese overseas companies are exposed to the risks of liability and litigation.Footnote 72 As pressure grows to hold multinational companies to account for their irresponsible behaviour,Footnote 73 it is just a matter of time before Chinese companies face litigation if they do not handle social and environmental issues properly. The negative environmental and social impacts caused by Chinese companies have already drawn much attention from regulatory authorities in some African countries. Potential lawsuits regarding land acquisition and relocation, labour protection, and environmental protection may compel Chinese companies to integrate environmental and social protection objectives into their daily operations.

3.2. Reducing Economic Losses

Chinese overseas companies and financial institutions conforming to high environmental standards can also reduce economic losses and achieve lower lending risks for their operations in Africa. As CSR has become a standard expectation in international business, it will be difficult to obtain access to the international market if it is not complied with. CSR has become an important ticket to the international market. The Chinese government expressly recognizes that CSR increases the international competitiveness of Chinese companies,Footnote 74 and seeks to encourage CSR to help Chinese companies grow internationally and sustainably. Moreover, empirical evidence shows that CSR facilitates long-term financial performance.Footnote 75 Current research also indicates that it is in the companies’ interests to minimize activity that may have a negative impact on the environment.Footnote 76 Investors, too, have recognized that companies that successfully and effectively manage social and environmental risks or concerns through self-regulation will generate higher returns on investment capital.Footnote 77 Corporate sustainable performance and financial performance are not a trade-off but correlate positively.Footnote 78 Additionally, as African countries strengthen their social and environmental regulations, Chinese companies in violation of the regulations face an increasing risk of civil claims and criminal fines. Moreover, negative publicity from even just one project could threaten future access by Chinese companies to resources and markets in Africa.Footnote 79

In recent years, socially responsible investing (SRI) has made inroads into Africa, particularly in the three major economies of Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa.Footnote 80 SRI investors invest only in companies that effectively govern their impact on climate change, human rights, social interests, and the environment.Footnote 81 With the development of SRI, companies with better environmental conservation practices in their operations may attract more capital from private and multilateral financial institutions.Footnote 82 Chinese companies can use the environment as a strategic competitive advantage and adopt higher environmental standards to help them gain financial access, greater acceptance, and access to markets in African host countries. Such action may also improve their public image relative to their competitors in Africa. However, it should also be noted that if Chinese companies superficially considered CSR only as a strategic competitive advantage without producing positive impacts in African host countries, it would leave the CSR initiatives adopted by the companies vulnerable to criticisms of greenwashing and ultimately undermine the legitimacy of their engagement as a whole.

In addition, promoting CSR by Chinese companies in Africa could help Chinese financial institutions to reduce lending risks, such as risks involving valuation and credit.Footnote 83 These financial institutions have come to realize that environmental and social risks are a potential cause of volatile markets and financial instability.Footnote 84 Investment in projects involving the risk of high pollution therefore increases their lending risks and may affect financial returns. As China's infrastructure projects in Africa are handled mainly by SOEs with financial support from Chinese state-owned banks, a financial loss for an infrastructure project overseas equals a financial loss for the Chinese government.Footnote 85 The case of the Lamu Coal Power Plant in Kenya – East Africa's first coal-fired power plant project – clearly shows the financial risks for Chinese financial institutions in Africa, as Kenya's National Environmental Tribunal suspended operations at the Lamu Plant on 26 June 2019.Footnote 86 The coal plant cost USD 2 billion, of which USD 1.2 billion was financed by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

3.3. Protecting China's Political Reputation

At the international level, the development of state-led CSR is driven by the state's interest in improving China's international reputation. The Chinese government actively uses Chinese companies to gain ‘soft power’ in international relations and political economy. Moreover, with the development of international legal instruments such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement, investment recipient countries have linked market access to CSR. CSR is an important strategy for protecting China's international political reputation. Furthermore, Chinese companies that actively engage in international investment typically are SOEs that have close ties with the state.Footnote 87 Any criticism against such state-affiliated companies may ultimately harm the reputation of the state itself. More specifically, as China's global expansion has attracted allegations of ‘neo-colonialism’, there is a strong incentive for the Chinese state to use CSR as a political strategy to alleviate international concern.

The image of China as a putative new colonial power in AfricaFootnote 88 is enhanced by the fact that China's investment on the continent mainly involves natural resource exploitation, which can result in serious environmental consequences. The way in which Chinese companies manage local employees has also raised concerns over social exploitation.Footnote 89 Moreover, the ostensibly generous financial aid provided by the Chinese government and financial institutions has been criticized for creating a deep financial trap through the imposition of onerous conditions that render African countries subordinate to China's control.Footnote 90 In the face of such allegations of neo-colonialism, the Chinese government and Chinese companies may have a strategic incentive to alleviate these concerns through CSR practices and thus improve China's political image in the international community.

4. WHAT IS THE RELEVANCE OF CHINA'S STATE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO THE AFRICAN CONTEXT?

Chinese companies have incentives to engage in CSR in Africa for a host of reasons, although such engagement does not necessarily have to be state led. Many western multinational companies operating in Africa, for example, have undertaken a wide range of CSR activities in Africa without the involvement of their home state. This raises the important question whether the state-centric approach that characterizes the engagement of Chinese companies in CSR conveys any particular advantage in the African context.

The effectiveness of market-based CSR is preconditioned on active NGOs as well as a range of educated and responsive users of information, which include consumers and investors. It relies on market pressure to force companies to engage in CSR. The market pressure may be exerted locally or internationally. In many African countries, local market pressure has not yet become a discernible force to make companies integrate CSR into their daily business management. Empirical research shows that the market-based CSR approach has made African companies engage in CSR only in a very superficial manner, treating it as public relations and philanthropy.Footnote 91 In this regard international market forces are particularly important. International market pressure may come from the multinational companies’ home-country market, as consumers and investors in that market respond to irresponsible behaviour on the part of the multinationals. A well-known example is the anti-apartheid shareholder activism in the United States (US) in the 1980s to put pressure on US companies to divest from South Africa.Footnote 92 Led by institutional investors from religious and public institutions, apartheid-minded investors used shareholder resolutions to apply pressure to US companies to curtail their investment in South Africa.

Home-country market pressure has been more observable in the west than it has been in China. To date, the Chinese public has not demonstrated particular concern or corresponding reactions to any irresponsible overseas behaviour on the part of Chinese companies. Chinese civil society and markets remain focused on domestic CSR issues. In this regard China's state-led approach may be a substitute for home-country market pressure in the western context. The Chinese state, which has international political interests at stake, is an important force pushing Chinese companies to engage in CSR in Africa. This motivation can help to address the lack of awareness on the part of domestic civil society in promoting Chinese CSR behaviour overseas and applying pressure on Chinese companies, especially overseas SOEs, to behave in an environmentally and socially responsible manner. Moreover, China's important investment projects in Africa are developed by SOEs. The Chinese state is an important investor with the power to direct the business trajectory of SOEs. China's state-centric approach may therefore complement the local but immature market pressure in Africa and substitute home-country market pressure.

Meanwhile, China's state-centric approach may aggravate suspicions of neo-colonialism in Africa. The pervasiveness of state control over Chinese overseas SOEs which dominate infrastructure and extractive sector projects in Africa has already raised the fear that Chinese investments are there to realize its neo-imperialist ambitions. The state-centric approach emphasizes ‘top-down’ control instead of ‘bottom-up’ community engagement. Under the state-centric approach, local priorities are unlikely to be adequately reflected in the CSR policies and practices of Chinese companies.Footnote 93

Moreover, the Chinese government and its affiliates are traditionally known for lack of transparency. This calls into question whether China's state-centric approach may be effective in protecting disadvantaged local people in Africa, which equally struggles with high levels of corruption.Footnote 94 McKinsey cited corruption as one of the greatest challenges in ensuring that the China–Africa trade partnership is sustainable in the long run.Footnote 95 The lack of transparency in China's state-centric approach could further cultivate corruption and deepen the concern that Chinese foreign investment is always funnelled into African countries with a weak rule of law and high levels of corruption.

5. THE STATE-CENTRIC APPROACH IN THE SGR PROJECT

While the previous sections have provided a general assessment of the potential promises and limitations of the state-centric approach in Africa, it is important to remember that Africa is not a homogeneous bloc. African countries have different historical, political, legal, social, and environmental backgrounds. Even within a country there may be regional differences. Furthermore, each investment project may have features that are not shared by others. These country-specific and project-specific attributes should be taken into account. Correspondingly, this section uses the country- and project-specific Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) case study in Kenya to further reflect on the promises and limitations of China's state-centric approach to CSR overseas. As part of China's BRI initiative, it aims to use Kenya's SGR project to gain access to trade and investment in Eastern Africa. The SGR is a railway construction project undertaken by a Chinese state-owned company, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). Of the project's funding 85% came from China Exim Bank, while Kenya provided 15% in co-financing. Construction of the Mombasa–Nairobi SGR project started in October 2014 and was completed on 31 May 2017.Footnote 96 This section empirically examines the role of the Chinese government and China Exim Bank in influencing the CSR performance of the CRBC during the construction of the SGR.

5.1. The State-Centric Approach to CSR in the SGR Project: Promises and Opportunities

The CRBC's CSR advancement benefits from the direct governing and monitoring power of the Chinese government and China Exim Bank, and is an example of the implementation of the state-centric CSR approach overseas. Because of the political importance of the SGR to both the Chinese and Kenyan governments, the Chinese government attached significant weight to the sustainable construction of the project. During President Kenyatta's visit to China in 2013, President Xi and President Kenyatta jointly witnessed the signing of the financing memorandum of understanding of the SGR project. In May 2014, Premier Li and President Kenyatta attended the signing ceremony of the financing agreement for the SGR. Premier Li urged the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) to meticulously construct the SGR, provide its Kenyan counterparts with necessary and qualified equipment, and offer operation and management training to local employees. As a Chinese SOE, the successful completion of the SGR as a sustainable project would not only represent the CSR efforts of the CRBC but also demonstrate China's railway construction capabilities and professionalism.Footnote 97

The Chinese embassy in Kenya played an important oversight role in the CRBC's CSR performance in the SGR. According to an officer at the embassy in Kenya, the Chinese government issued a strict directive to the embassy to ensure that the SGR was constructed sustainably, out of recognition that the international community paid significant attention to the project. Furthermore, the Chinese embassy in Kenya and the Economic and Commercial Counsellor's Office (ECCO) made concerted efforts to establish effective communication channels with the CRBC through regular visits and meetings. They propelled the CSR practices of the CRBC in the SGR project by requiring the CRBC regularly to report to the embassy on the progress of the project and to release a CSR report on the project. This direct engagement by the Chinese embassy and the ECCO provided the Chinese companies with informal governance oversight.Footnote 98

The embassy and the ECCO offered technical assistance and facilitated training for project managers, encouraging the CRBC to set up effective internal management, and hiring liaison officers to build closer connections with affected local communities to better address potential environmental and social challenges and risks. The relevant training was held once every two months to help CRBC managers and other SOEs learn local laws and regulations, familiarize themselves with the local business environment, strengthen their awareness of legal compliance, and help to address the financial arrangements during overseas operations, including customs clearance, taxation, and investment risks. The embassy also invited professionals for on-site consultations.Footnote 99 By sharing good practice and facilitating presentations, the embassy and the ECCO encouraged Chinese SOEs in Kenya to learn from each other's practices and draw lessons from negative examples. Managers of some invited Chinese companies claimed that through the compulsory training and group study sessions, they became more familiar with Kenya's local laws and regulations and developed a stronger sense of responsibility to complete the construction projects.Footnote 100

Lastly, in addition to the efforts and political guidance offered by the Chinese embassy in Kenya and the ECCO, Chinese business associations led by the ECCO also influenced the environmental and social behaviour of the CRBC in Kenya. The ECCO partnered with trade associations to release the 2017 Chinese Overseas Companies in Kenya Social Responsibility Report to further advocate CSR in the CRBC and other Chinese SOEs in Kenya. One such association is the Kenya China Economic and Trade Association (KCETA), a social organization comprising Chinese companies operating in Kenya.

The KCETA released its 2017 Chinese Overseas Companies in Kenya Social Responsibility Report in both English and Chinese to report on the overall environmental and social behaviour of Chinese companies in Kenya.Footnote 101 The report was written with technical support from the ECCO. It is the first CSR report regarding Chinese companies in Kenya, and shows the Chinese government's increasing attention to the CSR performance of its companies in Kenya. The KCETA and the ECCO in Kenya gave the private sector the opportunity to comment on legislative and regulatory proposals and give feedback on this report. Companies, therefore, were able to provide constructive criticism to help in developing new CSR measures that are practicable and reflective of business realities.Footnote 102 The report includes the CSR practices of several SOEs operating in Kenya, including those of the CRBC in the SGR project, to encourage other Chinese companies in Kenya to learn from them.Footnote 103

China Exim Bank, the main funder of the SGR, monitored and reviewed the project throughout the construction process. As a state-owned bank under the direct leadership of the State Council, China Exim Bank was encouraged to comply with the CSR standards established by the Chinese government. Responding primarily to political pressure to maintain the government's image overseas, the bank required the CRBC to meet social and environmental standards that went beyond the basic requirements of Kenyan law. China Exim Bank was responsible in the SGR project for conducting environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs), project reviews, public consultations with communities affected by the project, and ex post ESIAs in its lending policy.Footnote 104 According to an SGR project manager, three staff members in China Exim Bank were in charge of the assessment, management, and monitoring of the project. Each member had at least five years of project approval and supervision experience in the Approval and Management Department of China Exim Bank. The project manager in charge of the SGR project visited the project sites in 2014 and 2017 to conduct due diligence and post-evaluation reports regarding the impact of the project on the local community. During construction, the CRBC project manager was obligated to report to China Exim Bank, via email and telephone conferences, on progress of the construction and any urgent matters.Footnote 105

In general, the Chinese government contributed to the improvement of the CSR performance of the CRBC in the SGR project in a number of ways. Firstly, the Chinese ‘Going Out’ policy provides a regulatory framework for CRBC operations in Kenya. The policy framework, which includes policies and regulations relating to China's sustainable investment overseas, helps to promote the development of CSR in Chinese companies and the financial institutions’ practice of green finance. Secondly, the Chinese government established a strong and interlocking institutional network to regulate and support CRBC operations in Kenya. Together with financial loans and support from the state-owned China Exim Bank, the political and financial supervision by the Chinese government further facilitated, endorsed and mandated the CRBC's responsible behaviour in the SGR project. Thirdly, significant political willingness by the Chinese government for a successful completion of the SGR enhanced the effectiveness of the state-centric approach to advancing the CSR activities of the CRBC. Such diplomacy, reflected in extensive high-level political visits to Kenya with promises of loans and technical assistance from the Chinese government, promoted a favourable environment for the construction of the SGR project.

5.2. Limitations of the State-Centric Approach in the SGR Project

The case study has methodological limitations and substantive limitations in terms of implementation. With regard to methodology, it should be noted that the SGR case presents the environmental and social behaviour of a single Chinese SOE engaging in infrastructure construction in Kenya rather than a comprehensive examination of the behaviour of all Chinese companies overseas. As a result, the lessons learned from the SGR case are not able to be generalized for all Chinese financial investment contexts in Africa. African countries are quite heterogeneous in their institutional qualities. It is uncertain whether the findings in Kenya can be applied equally to Chinese infrastructure projects in other African countries. Moreover, various types of Chinese company operate in Kenya: from SOEs, as in the case of the SGR, to wholly private companies. The state-centric approach of CSR may not be equally effective to influence CSR in privately owned companies, given the diverse political and business cultures of the various types of Chinese company.

In addition, the SGR case confirms some theoretical limitations of the state-centric approach. In the SGR project, the CRBC preferred to deal with local governments and stay away from local NGOs and media in Kenya. This tendency was rooted mainly in its limited experience with civil society engagement back in its home country of China. As a result, local NGOs and media were more suspicious of the CRBC and did not engage in any meaningful dialogue with the corporation during the construction process. The SGR thus evidences a lack of input from civil society, which is a major weakness of the state-centric approach. China's state-centric approach, developed in isolation from the local NGOs and media, does not encourage its CSR strategies to be responsive to local needs. Moreover, without substantive engagement with the local NGOs and media, the state-centric approach is of only limited help in building the good international reputation that China desires. Insufficient communication breeds distrust and misunderstanding. Meaningful and interactive engagement rather than defensive avoidance are a better way to gain trust and a good reputation within the international community. To correct the weakness of the state-centric approach, it is important to encourage the Chinese government and its affiliated institutions to become more involved with civil society.

While the Chinese government may exert tight control over its domestic civil society, its administrative influence over international civil society is very limited. This is demonstrated in the SGR project. According to the interviews, neither Kenyan NGOs nor Chinese NGOs in Kenya engaged meaningfully in dialogue with the Chinese government, China Exim Bank, or the CRBC throughout the construction process. The attitude of the CRBC towards local NGOs and media was that of ‘keeping them at a distance’.Footnote 106 The public relations officer for the SGR project believed that the Kenyan media always focused on eye-catching stories to attract their audience and sometimes failed to carry the social responsibility of media independence.Footnote 107 The language barrier between the CRBC, local NGOs and the media made it more difficult to achieve effective communication. As a result of this lack of communication, the CRBC believed that its voice was not heard by local communities. One concrete example is a misunderstanding that arose regarding land compensation.Footnote 108 Although responsibility for land compensation for the local community did not reside with the CRBC, ‘local villagers believed that the CRBC was conspiring with the government to destroy their land and property by building railways’.Footnote 109 On receiving such complaints, the CRBC preferred to communicate with local governors to express any unspoken concerns and raise suspicions about the true intentions of the local NGOs and media.Footnote 110 This communication breakdown further exacerbated the misunderstanding between the CRBC and the NGOs and media.Footnote 111

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the state-centric approach depends on the political commitment of the government. The SGR project had a high political value for both the Chinese and Kenyan governments, which fostered a favourable environment to press the CRBC to engage in CSR practices. This political value is an important feature of the state-centric approach as the market-based CSR approach mainly promotes business values. The SGR case suggests that the state-centric approach may be weaker when projects are not politically important.

Finally, China Exim Bank did not disclose its assessment report on the environmental and social impact of the SGR project; nor did it make sufficient disclosures about the implementation of CSR measures in the project. As the bank has no legal obligation to disclose project evaluation information, and there is no third-party monitoring or grievance mechanism to allow affected communities and individuals to file complaints during construction, the overall credibility of the sustainable lending process is doubtful. In addition, the SGR project manager opined that generally not enough staff were involved in the lending processes of China Exim Bank.Footnote 112 According to the manager, the three people in charge of the SGR project were responsible also for reviewing and approving other infrastructure projects at the same time. With more projects awaiting approval under the BRI, the workload of the 30 full-time staff members in the Approval and Management Department of China Exim Bank has become very onerous.Footnote 113 Without adequate technical personnel involved in the lending process, the credibility of China Exim Bank as a monitoring body is compromised. Poor transparency is a salient weakness of China's state-centric approach; it undermines the credibility of this approach in advancing the CSR of Chinese companies overseas.

6. CONCLUSION

As one of the most important global test sites for state-centric CSR, this article analyzes the development and features of China's state-centric approach to CSR in Africa. It examines and highlights the benefits and limitations of this approach in promoting China's sustainable investment overseas through an empirical study of the SGR project in Kenya. The article has found that the Chinese government and its affiliates are motivated to engage in CSR in Africa in order to avoid potential legal liabilities and economic losses as well as to improve the international reputation and political image of the Chinese state. The state-centric approach can have a positive impact on promoting CSR. By adopting this approach the Chinese government is not only a regulator but also an important stakeholder in Chinese SOEs in advancing CSR. The government can influence the behaviour of SOEs and state-controlled financial institutions through its power to appoint board members and senior managers. The government uses its various institutional connections with SOEs and financial institutions to strengthen awareness of policy objectives and provide incentives for policy implementation. Hence, state-centric CSR presents a complementary regulatory pathway to address the potential limitations of conventional CSR approaches, which rely on market logic, altruism, or active civil society as driving factors. However, the state-centric approach does have its limitations. These include lack of engagement with civil society actors and the inability to influence privately owned Chinese companies outside the control of the Chinese state in host countries.

China's state-centric CSR development in Africa offers a unique opportunity to consider the potential for the state in monitoring and driving Chinese corporate sustainable investment overseas. The SGR case study further shows that the CSR commitments made in the SGR project were a result of coordination between the Chinese government and its affiliates, with very limited input from local NGOs and media. On the one hand, it demonstrates the usefulness of the state-centric approach through mandating, facilitating, endorsing, and partnering to improve the CRBC's CSR behaviour. On the other hand, it shows important limitations of the state-centric approach, including lack of engagement with local NGOs and media, dependence on the political salience of individual projects, and poor transparency at the implementation level. It provides regulatory lessons for future Chinese infrastructure investment in Kenya and beyond. Combined with the conceptual framework analysis, this case study provides a deeper understanding of the promises and limitations of China's state-centric CSR approach.

This article has examined the role of the state-centric approach to CSR in only one Chinese SOE engaged in infrastructure construction in Kenya. It therefore cannot represent fully the complex landscape of Chinese corporate operations in Kenya and the rest of Africa. Various types of Chinese company operate in Kenya, from SOEs to privately owned companies. The state-centric approach to CSR may not be as effective in influencing the CSR of privately owned Chinese companies given the diverse political and business cultures and various models of corporate ownership in China. In addition, the small number of interviewees in the different fields cannot represent the full spectrum of Chinese overseas companies and affected stakeholders. Moreover, the credibility of information is difficult to verify, particularly with regard to information from Chinese government sources, including officials and agents under its control. Lastly, economic and social conditions vary from one African country to another. Whether the state-centric approach could be applied to other Chinese infrastructure companies in other African countries merits further examination. For these reasons the findings in this article should serve primarily as a starting point for further research and a foundation for future empirical work to analyze the strengths and limitations of the state-centric approach to CSR in promoting Chinese sustainable overseas investment.

APPENDIX

Table 1 State-led Initiatives regarding the Overseas CSR Performance of Chinese Companies (cited at Section 2.4)