Introduction

Orangutans, like the other great apes, have for centuries captured the imaginations of people around the world, appearing historically in local legends, philosophy texts, travel writing, literature, stage performances, art works, exhibitions, film, zoos, and circuses. Their representation in human culture has been intertwined with the history of scientific knowledge production. Scientists since the seventeenth century have studied their individual and community interactions, their habits of daily life, intelligence, anatomy, tool use, mating, and rearing practices.Footnote 1 The earliest studies of orangutans emerged during the Enlightenment, as natural historians attempted to delineate the boundaries between human and beast. Unable to observe orangutans in the wild, European scientific treatises in the eighteenth century relied on what Christina Skott (Reference Skott2014: 158) calls “travel lies” as natural historians uncritically used travel literature, local folklore, and hearsay to construct truth claims about both apes and the people of the Malay World. Europeans and Americans cast stereotypes on orangutans just as they did the people of the Global South, constructing them as vicious savages (Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, Helen and Helen2014: 93–96). Western imaginings of orangutans changed over time after natural historians encountered non-human primates in the wild and in zoos and laboratories. By the 1920s, they were viewed as gentle, intelligent creatures worthy of admiration and study. Darwin and Wallace's theories of evolution were both influenced by observing orangutans, albeit in very different settings (Van Wyhe and Kjærgaard Reference van Wyhe and Kjærgaard2015: 53). People's interest in orangutans, both as a source of entertainment and as a philosophical object of study from which to consider what it means to be human, has never waned. The challenge for people in the West was obtaining orangutans to observe and study.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, live orangutans circulated on the global market as individuals and were occasionally brought from the interior of Borneo or Sumatra to the ports by traders in exchange for goods. Explorers passed through the ports of Southeast Asia, collecting individuals to transport to the metropoles. Natural historians were especially interested in acquiring live orangutans for behavioural studies and as zoological specimens to examine in European laboratories. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, the advent of the Linnaean taxonomic system impacted research methodologies (Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, Helen and Helen2014: 103; Skott Reference Skott2014: 142). European explorers set out to map the natural world on a global scale. Some travellers journeyed to the Malay Archipelago in search of species new to science, along with a deep interest in observing, hunting, and collecting orangutans. It appears that hunting occurred more in the British colony of Sarawak than in Sumatra, which might be one reason that, in the West, the orangutan has historically been most closely associated with the island of Borneo.

The White Rajahs of Sarawak provided hospitality and logistical support to many explorers. James Brooke, the first White Rajah (1842–1868), had an interest in the natural history of Borneo and welcomed Alfred Russel Wallace during his travels to the island in the 1850s, and Odoardo Beccari in the late 1860s, as they searched for orangutans and other species. Wallace spent much of his time hunting and collecting apes to study, preserve, and sell to museums to fund his travels (Coote et al. Reference Coote, Haynes, Philp and Ville2017: 333; Wallace Reference Wallace2008 [1869]: 32–49). Similarly, William Hornaday, the future director of the Bronx Zoo, travelled to Malaya and Sarawak in the late 1870s and stayed at the cottage of Charles Brooke, the second White Rajah (1868–1917). On the trip, Hornaday collected a reported forty-three orangutans (Hornaday Reference Hornaday1887: 486) and also adopted a young male to observe the behaviours of the apes up close (Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld2016: 63). The explorers studied orangutan ethology and measured their skeletons in the field, but they were unsuccessful at exporting live individuals back to the West because the apes rarely survived capture and transport. Wallace, Beccari, and Hornaday are just a few of the many explorers that hunted orangutans in Borneo during the nineteenth century. Charles Brooke must have noticed the impact of hunting on orangutan populations in Sarawak because he reportedly signed the first legislation providing legal protection to the primates in 1895. Cribb et al. (Reference Cribb, Helen and Helen2014: 213) suggest that by that time there would have been few orangutans left in his territory due to the previous century of hunting and catching.

The demand for orangutans only increased in the early twentieth century, although living animals were preferred to skeletons. Primate exhibits in zoos were especially popular with patrons. In 1901, an orangutan show at the Bronx Zoo, under the directorship of Hornaday, increased annual attendance by an estimated 100,000 visitors (Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, Helen and Helen2014: 189). By 1915, orangutans were the primary Indonesian species of interest to the director of the Artis Zoo in Amsterdam (Koninklijk Zoölogisch Genootschap Natura Artis Magistra).Footnote 2 However, captive orangutans lived dismally short lives. In the second half of the nineteenth century, it is estimated that the average life span for orangutans in captivity was about two months, with the record being five years. In the first half of the twentieth century, the London Zoo held thirty orangutans and their survival in captivity remained under four years (Cousins Reference Cousins2009: 86). Chris Herzfeld examined zoological records between 1837 and 1965 and concluded that on average primates in general survived only about eighteen months in captivity (Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld2016: 14). Researchers continuously searched for methods to keep orangutans alive in laboratories and other institutions, but breeding programs did not produce the results necessary to meet the demand for apes in the West until after the 1970s (Haraway Reference Haraway1989: 22; Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld2016: 64).Footnote 3 Orangutans, therefore, had to be imported from Southeast Asia, but little is known about the history of the trade in primates.

Drawing on archival data from Indonesia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, in addition to newspapers, colonial publications, scientific reports, journal articles of the day, and more recent secondary literature, this article examines the geographies and politics of the global trade in orangutans in the name of science and entertainment in the first half of the twentieth century, along the background of the growing international nature protection movement. While the orangutan was most closely associated with the island of Borneo, by the early 1900s a majority of orangutans on the global market were captured in, and exported from, northern Sumatra. The focus of this article is therefore on northern Sumatra and the impact that the orangutan trade had on the colonial administration of the region. The orangutan trade emerged at the same historical moment as an organised international nature protection movement, as conservationists in Europe called it at the time. Certain segments of the public began to contest the wildlife trade, laboratory research on non-human species, game hunting, and habitat destruction in the colonies. As the orangutan diaspora grew outside of colonial Indonesia, so too did public demands for their protection in their native habitats. The orangutan trade and the arrival of large numbers of apes in Europe more broadly influenced material practices and decisions central to the colonial project, including the tightening of borders and surveillance in the ports and on land, as well as the creation of wildlife protection laws and policies that regulated human relationships with the environment.

The growing appearance of colonial non-human subjects, and orangutans in particular, in laboratories, zoological institutions, museums, and circuses engendered a public protest against their capture and in favour of species and habitat protection. In her history of field science in Africa, Helen Tilley has suggested that field studies and other “sciences of empire” have oftentimes exposed the destruction caused by colonial economic exploitation, challenging the state's ideological authority in the colonies (Tilley Reference Tilley2011: 322). Orangutan research in Europe that brought trafficked apes from colonial Indonesia to the metropoles had a similar effect. Public debates surfaced in response to the growing orangutan diaspora in Europe in the 1920s, sparking a controversy in many ways reminiscent to calls to protect birds-of-paradise a few decades earlier in New Guinea and adjacent islands. In both instances, concerned citizens and conservationists reacted with alarm over fears of extinction, and the public witnessed the exploitation of tropical species in person, as the trade brought parts of animals, in the case of the birds-of-paradise, and both living and dead orangutans to Europe.

However, state efforts to protect threatened species in colonial Indonesia was a slow and frustrating process for conservationists. Birds-of-paradise were eventually granted protected status in 1909 with additional decrees in 1910 and 1912, although their protected status did little to decrease the trade (Andaya Reference Andaya2017: 376; Cribb Reference Cribb and Boomgaard1997: 395–7; Ross Reference Ross2017: 247–8). Orangutans in Indonesia were not given legal protection until a decade later, in part because many colonial officials and capitalists viewed the apes as agricultural pests (Boomgaard Reference Boomgaard1999: 265). In fact, the Dutch delineated the first protected areas in northern Sumatra in 1919 to protect the “corpse flower” (Rafflesia arnoldii), a plant known for having the largest individual flower in the world. The reserves, however, remained “paper parks” as regulations were never enforced.Footnote 4 Orangutans were not yet viewed as threatened at that time, but by the late-1920s they served as the figurehead of conservation efforts in the region for the growing international nature protection movement. The orangutan trade was not the sole impetus for Dutch conservationists to propose expanded nature reserves in northern Sumatra, but they were able to use the exploitation of the orangutan as a means to justify their claims that the forests were in need of protection.

At the same time, some conservationists, scientists, and zoo officials who were calling for governmental action to protect orangutans were also key actors in the wildlife trade. This draws multiple parallels with the phenomenon of the North American and European hunter-naturalists, or big game hunters turned conservationists in Africa who sought to exploit the game resource carefully, while at the same time reinforcing colonial privilege (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1988: 7; Ritvo Reference Ritvo1987: 287; Ross Reference Ross2017: 253–256). Both scientists and sportsmen desired to exploit and protect non-human species for their own benefit – scientific knowledge production and economic gain in the first instance and the future of game hunting in the second – while limiting or altogether banning the opportunity for local peoples and others to participate in those same activities. This history of colonial Indonesia has multiple striking resonances with the history of wildlife conservation in Africa. Below I trace the transnational social networks of conservationists, scientists, zoo officials, orangutan traders, and the many people who crossed all of those categories in the first few decades of the twentieth century to elucidate the impact of their activities on colonial practice in northern Sumatra.

Plantations and the Wildlife Trade

In May 1913, dockworkers placed a wooden cage containing an adult orangutan into the hold of a ship at the port of Belawan on Sumatra's east coast. The ship was destined for Amsterdam via the Suez Canal. Sultan, as the orangutan was named, was the prized acquisition of Coenraad Kerbert, the director of the Artis Zoo in Amsterdam. Orangutans were difficult to obtain in the early twentieth century, but Kerbert's networks extended into Sumatra, which along with Borneo comprise orangutans’ two native homes. Kerbert received Sultan from his friend and colleague, L.P. de Bussy, the director of the Deli Experiment Station in Medan (Deli Proefstation te Medan-Sumatra), an agricultural research centre in the heart of the Sumatran plantation belt (cultuurgebied). From 1911 to 1935, the director of the station sent hundreds of Sumatran species to Kerbert, from tapirs, pythons, and tigers, to rhinoceros hornbills, crocodiles, and orangutans. Almost all the animals were captured on plantations in the cultuurgebied.Footnote 5

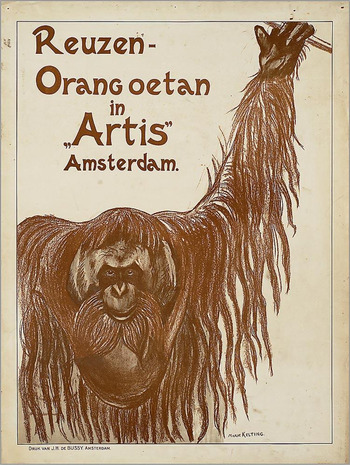

Sultan arrived at the Artis Zoo in August 1913. In anticipation of his arrival, newspapers declared the monkey house to soon be the “crown above all Zoological Gardens in the world” (Amersfoortsch Dagblad 1913).Footnote 6 Dutch artists visited the zoo to capture the primate's image on canvas and in stone. Marie Kelting, for example, painted Sultan onto an exhibition poster that still hangs in the exhibit gallery in the aquarium building at Artis (Figure 1). Jaap Kaas sculpted a bust, while Piet Bohncke created a bronze plaque of the orangutan. Sultan's popularity was attributed to his physical appearance and anthropomorphic characteristics. He was physically imposing – a giant (reuzen) orangutan with broad cheek pads, a colossal (kolossaal) throat sac, and long reddish-orange hair and beard – but he was also described as humble, quiet, and wise. He was the “old man of the woods” (Amersfoortsch Dagblad 1913; Nieuwsblad van het Noorden 1913). The name that his capturers gave him signalled masculine prestige and power, but at the same time it bespoke Dutch sentiments with their beloved colony (on colonial nostalgia, see Pattynama Reference Pattynama, Boehmer and De Mul2012: 99). Sultan was a colonial subject both metaphorically and materially, but he died at Artis from typhus on 13 December 1914, only sixteen months after arriving in Amsterdam.

Figure 1. Marie Kelting's advertisement from 1913 featuring Sultan the orangutan at the Amsterdam Zoo. It reads, “Giant-Orangutan in Artis Amsterdam.” From the collections of the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD), Image No. 0000184737.

The story of Sultan offers insight into a broader phenomenon: the emergence of the wildlife trade from northern Sumatra to Europe and North America alongside the expansion of plantations in the cultuurgebied, or the plantation belt along Sumatra's east coast. Agricultural development transformed more than 10,000 km2 of rich alluvial lowland plains and lower montane forests on the east coast of Sumatra into monoculture plantations before the Second World War (Stoler Reference Stoler1995: 2). A variety of factors created a situation in which the wildlife trade could thrive. The cultuurgebied was located along the Straits of Melaka, a global trade hub for centuries, which expedited the trade as animals were moved quickly to the ports and on to Singapore where they were sold on the global market. On the plantations, there were multiple economies already in place, transportation infrastructures were developed to move commodities on to the global market, scientific institutions and their social networks accompanied agricultural development, and a diversity of species lived at the edges of the cultivated plots. Animals that were previously hidden in the dense forests were exposed as they crossed the new frontier onto the plantation. Once animals entered the plantation, they were transformed into pests, threats, and commodities that were either hunted or trapped and sold.

The plantations were cut out of tropical forests, which opened new habitats for both human and non-human species. Sumatran cobras and short-tailed pythons, Sumatran tigers, and many other species thrived in the ecotones where the forests met plantation ecosystems. There they fed on rodents and creatures that took advantage of the available agricultural produce, and also on humans and their livestock in nearby settlements. Newspaper stories mention tiger and elephant trapping on the plantations and coolies being bitten by snakes and attacked by tigers. One particular column from 1938 describes the life of the planter in northern Sumatra as monotonous and difficult, with the only variation to daily routine being their near daily encounters with wildlife, including snakes, elephants, tigers, and orangutans, which were often caught and kept as pets or sold to zoos (De Sumatra Post 1938).

Trappers and hunters set up camps near the plantations, stayed in the colonial estates, and caught species in the area. The plantations also served as a place of safari for elephant, tiger, and rhinoceros hunts, although hunting in Sumatra was less prevalent than trapping and capturing for sale. Hunting was not an important feature of colonial rule for the Dutch, and it appears that, at the turn of the twentieth century, it was limited to military personnel, forestry officials, plantation staff, and American and British tourists in northern Sumatra (Boomgaard Reference Boomgaard2001: 36). Some Dutch plantation staff did hunt in their free time. A.C. van der Valk (Reference van der Valk1940:10), who worked as a planter for a rubber and oil palm company in Deli during the second half of the 1920s, hunted and trapped countless animals across northern Sumatra. He brought along other planters and company personnel on trips to hunt, trap, and catch all sorts of species, including elephants, tigers, wild boar, binturongs, siamangs, monkeys, crocodiles, snakes, turtles, orangutans, hornbills, and other birds, and many more. He also documented indigenous hunting practices among the Gayo, Batak, and Malay peoples who often accompanied his expeditions around the plantations and into the forests. After working as a planter for a few years, Van der Valk found that he could live comfortably off the income earned from catching species for the collections of plantation managers and for institutions back in the Netherlands. By 1930, he quit agricultural work to pursue a career in hunting and catching animals for export to Europe, which I will discuss below.

There are also records of foreigners who travelled to Deli specifically to hunt game in the forests near the plantation belt, or who decided to try their hand at hunting while in the region on business. In Deli, travellers could find lodging, porters and guides to lead hunting excursions, and automobile and railway transport to explore the area. Hermann Norden, an explorer and fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, travelled to northern Sumatra in 1920 to hunt elephants. According to Norden (Reference Norden1923: 165), the proprietors of large estates in Sumatra often employed professional elephant hunters to lead guided hunts into the forests. He lodged at a plantation estate during his time in Deli, and describes the local context in his book. Plantation owners sent coolies on hunts to collect rhinoceros and elephant heads, tusks, and horns to adorn the walls of the estates, while they divided up the remainder of the animals for food or to sell to Chinese markets in Medan (Norden Reference Norden1923: 169). According to his story, Norden joined a hunt and he did have success killing an elephant, but we can gather that he was more interested in local social relations, cultural practices, and the experience of staying on a plantation estate than he was with the hunt. For as soon as he shot the animal, he abandoned the scene out of boredom and returned to his quarters on the plantation. In a separate instance, a group of nine Americans, including seven men and two women, embarked on a hunt along the coast between Lhokseumawe and Medan with eighty-five coolies to drive animals from the forest and to transport the catch (Delftsche Courant 1930). The author notes that the hunt was carried out for the sake of sport, rather than to collect scientific data or capture live specimens.

The ecotones and infrastructure that accompanied capitalist development not only helped people in northern Sumatra hunt animals, but also provided convenient opportunities to collect live species for the wildlife trade. Both local peoples and Europeans caught animals in the region. Van der Valk (Reference van der Valk1940: 77) states that people were constantly delivering live animals to his home to earn extra income after they found out that he was a wildlife trader. Some Dutch scientists that worked on the plantations took advantage of their local relations to collect species to sell to institutions back in the metropoles. This was the case with Sultan the orangutan. If you recall, L.P. de Bussy, the director of the Deli Experiment Station, sent hundreds of species to the Artis Zoo in Amsterdam in just a few decades in the early twentieth century. Sultan, according to the records, was the only animal that De Bussy did not obtain from the plantations – though in most cases Dutch, American, German, and other plantation staff hired indigenous trappers to collect species. In De Bussy's search for orangutans, he learned that Sultan Tuanku Sulaiman of Serdang, a native leader who laid claim to territory on the outskirts of Deli in the cultuurgebied, kept a small menagerie. Unfortunately, it appears that the only remaining sources describing Sultan Sulaiman's menagerie are a handful of newspaper articles. Sultan Sulaiman, according to the press, employed groups of local people to search for and capture animals in the forests and edges of the plantations in the cultuurgebied. From the papers, we learn that he kept elephants, water buffaloes, tigers, a few bears, and even an Australian cassowary (De Sumatra Post 1908; Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1915). De Bussy took a particular interest in the menagerie because there were always a few orangutans on hand. He spent months trying to convince Sultan Sulaiman to sell him an orangutan and eventually he succeeded. The Sultan gifted him an orangutan in April 1913, and De Bussy named the ape after his previous owner and shipped him to the Artis Zoo.Footnote 7

The transactions between De Bussy and the Artis Zoo are some of the earliest recorded signs of a systematic colonial wildlife trade from Sumatra to Europe. In the precolonial period, the Sumatran wildlife trade was mostly limited to local rulers and sultans who gifted or traded elephants, horses, and other species to kingdoms across the Indian Ocean and Malay Worlds. There also existed a regional trade in animal parts, such as rhino horn and ivory from elephants, and hunters or trappers from the interior sometimes took captured animals, dead or alive, to the coasts to sell or trade (Andaya Reference Andaya1979: 25; Andaya Reference Andaya2008: 121–124; Poniran Reference Poniran1974: 576; Van Heurn Reference van Heurn1929: 18). By the turn of the twentieth century, northern Sumatra had become a major stop on the global wildlife trade network. Some of the most prominent animal dealers in the world passed through in search of unique creatures. German suppliers from the Hagenbeck and Ruhe animal empires visited Sumatra's east coast, as did Frank Buck and Charles Mayer, two famous American film and radio personalities who profited from their oriental tales of hunting and trapping animals in the tropics (see Buck and Anthony Reference Buck and Edward1930; Mayer Reference Mayer1921). The story of Sultan draws attention to precolonial wildlife trading networks on Sumatra's east coast, with species coming from Aceh and beyond. Colonial officials were able to access that network, or at least learn from the techniques of the Sultan's crew, and use that knowledge for their own ends of obtaining and exporting species to the metropole. The arrival of orangutans from Sumatra to Europe and North America brought the ecologies of the southern interior of Aceh to the attention of conservationists and scientists in the metropole.

Conservation and Crisis

H.D. Rijksen and Eric Meijaard (Reference Rijksen and Erik1999: 137) identify a few notable moments in the twentieth century when public concern reached a fevered pitch in reaction to large numbers of captured orangutans arriving in Europe from Sumatra or Borneo. The first such incident occurred in the 1920s. The records show that in the 1920s, most of the exported orangutans were captured in northern Sumatra. The situation escalated to a crisis in the minds of European conservationists, zoo officials, and concerned citizens regarding the violent capture and export of orangutans to zoological institutions, museums, and private collectors around the world. They wrote letters to the editor in prominent newspapers in Britain, the Netherlands, and the East Indies, sparking a public debate over the future of the anthropoid ape. Nature protection groups were also aware of threats posed to other Sumatran species, especially elephants and rhinoceros, but those species were not traded to Europe to the same extent as orangutans. While Sumatran rhinoceros and elephant parts had been sold in markets throughout Asia for some time, it was not until 1872 when the famous animal trader, Carl Hagenbeck, imported the first Sumatran rhinoceros to Europe (Rothfels Reference Rothfels2002: 181). Orangutans, on the other hand, had been traded to the West since the seventeenth century, and they were the most visible species from Indonesia in Europe and North America.

The transnational circulation of orangutans occurred simultaneously with the growth of the international nature protection movement. The early twentieth century was the age of a new imperialism characterised by military expansion into the peripheries of empires around the globe, but it was also, in part, ideologically based on the white man's burden and forms of humanitarianism to make some amends for the exploitation of colonialism. The international nature protection movement can be placed within that context. Many countries already had wildlife and habitat conservation organisations, including the Boone and Crocket Club in the United States (1887) and the Society for the Promotion of Nature Monuments in the Netherlands (1904). The 1900 London Convention on the status of African wildlife helped to launch the international nature protection movement. In 1903, British conservationists established the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire. Other committees formed in the Netherlands in 1925, Belgium and France in 1926, and the United States in 1930 (Jepson and Whittaker Reference Jepson and Whittaker2002: 156–7). It was an environmental movement comprised of transnational political, social, and scientific networks and collaborations. Colonialism in the Global South allowed environmentalists to intervene in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere. Conservation was often made possible by militarisation, land grabs, and the dispossession of indigenous peoples, and nature protection policies were more generally reminiscent of the civilisation mission of colonialism (Adam Reference Adam2014: 6–11; Kupper Reference Kupper, Gissibl, Höhler and Kupper2012: 135; Peluso and Vandergeest Reference Peluso and Peter2001: 795; Spence Reference Spence1999).

Wildlife protection measures took shape earlier in colonial south, east, and central Africa than in Southeast Asia. Corey Ross (Reference Ross2017: 248) suggests that it is owing to the abundance of megafauna, the large game hunting industry, and the “environmental memory” of past species extinctions in the south of Africa. Conservationists in the Netherlands maintained social networks with colonial officials and scientists in Africa, especially in the Belgian Congo. P.G. van Tienhoven along with a group of politically powerful Dutch men, mostly environmentalists, scientists, and colonial officials, established the Netherlands Commission for the International Protection of Nature (Nederlandse Commissie voor Internationale Natuurbescherming, hereafter, the Commission) in 1925. Van Tienhoven worked tirelessly to unite European and North American environmental protection groups to form an international conservation union. He had built close relations with J.M. Derscheid and the Belgium Society for the Protection of Nature between 1925 to 1930 in collaborating to establish Albert National Park in the Belgian Congo, primarily for gorilla conservation, and the experience was formative for his outlook on global conservation.Footnote 8 He viewed the interior of northern Sumatra, known locally as the Gayo and Alaslands (tanah Gayo and tanah Alas) after the indigenous peoples of the region, as his own Congo and Sumatran orangutans were his gorillas. He had the blueprint from his experience in the Belgian Congo and his goal was to carry out a similar project in northern Sumatra. The timing was critical, as the late 1920s also marked a peak in the orangutan trade from northern Sumatra to Europe. The Commission used the ensuing orangutan crisis to organise and strengthen the international movement and to advocate for new and expanded reserves and wildlife laws in Indonesia.

After the First World War, other traders and trappers moved into northern Sumatra to challenge the control that De Bussy and Kerbert held on the wildlife trade in the region. One particular trader specialised in collecting orangutans. J.F. van Geuns was responsible for the majority of orangutans that were taken out of Sumatra in the first half of the twentieth century. They were shipped to zoos, circuses, museums, laboratories, and private collectors in Adelaide, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Brookfield, Edinburgh, London, Melbourne, Rotterdam, St. Louis, San Diego, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Many influential primatologists and biologists studied and conducted experiments on his orangutans, setting the foundations for human understandings of orangutan behaviour (Jones Reference Jones and de Boer1982: 22). Van Geuns was the collector and transporter, and evidence of his smuggling activities – after the trapping and export of orangutans was banned in 1924 in Indonesia – appears in newspapers and colonial archives. He sold orangutans to the well-known animal dealer, Hermann Ruhe of Alfeld, Germany, and also to C.A. Périn, an animal trader who owned a shop in the centre of Amsterdam at Nieuwendijk 116–118.

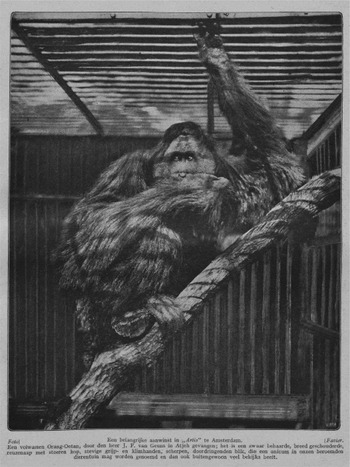

In July 1926, Van Geuns returned from northern Sumatra to Europe with an unspecified number of orangutans. He sold four of the apes to C.A. Périn, which on the receipt were priced according to size: a giant (reuzen) male named Jacob (4000 guilders), a large (groote) adult male (1400 guilders), a female (1000 guilders), and one with a broken foot (sex and sale price not listed). Périn sold Jacob to Kerbert, the director of the Artis Zoo, on 3 September 1926 (Figure 2).Footnote 9 Also on the receipt are listed six adult Sumatran tigers (1200 guilders/individual), two young Sumatran tigers (2400/pair), two binturongs (250 guiders/individual), five reticulated pythons (price varied by the length of the snake), two Javanese rhinoceros hornbills (200/bird), many other birds, and various turtles. The receipts do not mention who caught the animals.

Figure 2. Jacob the orangutan at the Artis Zoo in Amsterdam in 1926. J.F. van Geuns collected Jacob in Aceh in 1926. C.A. Périn purchased and sold him to Coenraad Kerbert, the director of Artis Zoo in Amsterdam. From the 2 October 1926 issue of De Prins der Geïllustreerde Bladen, obtained at the Centrale Bibliotheek in Rotterdam.

Van Geuns also sold orangutans from that shipment to Hermann Ruhe, of which one reuzen male named Goliath ended up with Gustav Brandes, a zoologist at the Dresden Zoo in Germany. Paul Eipper, a German author known for his narrative animal books, was present for many of the transactions and interviewed both Ruhe and Van Geuns. According to Eipper and Kirwan (Reference Eipper and Patrick1929: 75), Van Geuns dropped off the first orangutan and asked Ruhe, “Would you like some more? If you like I can bring you a dozen. I might even be able to manage a whole family with young. I know a place that is swarming with them”. Van Geuns returned to Europe again from northern Sumatra in April 1927 with a shipment of 25 orangutans. News of the cargo spread quickly. Zoo directors, writers, photographers, and others travelled to Alfeld to observe and bid on the recent arrivals. Ruhe offered the orangutans for sale in adult pairs, set the price at 25,000 German marks per pair, and sold the 25 individuals to a group of zoo representatives. Eipper (Reference Eipper and Patrick1929: 75) commented that “old experienced keepers, men who for forty-five years had handled every conceivable kind of zoological rarity, were wild with enthusiasm when they saw this shipment for the first time”. The orangutans were gold in the eyes of Ruhe, and he sent Van Geuns back to Sumatra for more.

Wildlife traders were able to move back and forth between the colonies and metropoles relatively quickly due to the speeding up of transport infrastructure and communications within the archipelago and between the Dutch East Indies and the Netherlands. The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut the journey from Amsterdam to Deli in half, and steamships could complete a one-way trip in 40 days (Jonker and Sluyterman Reference Jonker and Keetie E.2001: 195). In northern Sumatra, the Aceh Tram was completed in 1917. It was initially built to transport soldiers and military weapons during the Dutch-Aceh War, but after the hostilities subsided it was primarily used to move civilians, goods, and wildlife throughout the plantation belt.Footnote 10 Trappers caged animals near plantations and human settlements and then loaded the live cargo on trains that led to the port of Belawan. From Belawan, the cages were placed in the holds of ships that travelled from Sumatra to Europe. A.C. van der Valk, who was discussed earlier in this essay because of his hunting exploits in northern Sumatra in the 1920s, outlines his itinerary transporting a load of animals from Aceh to Europe around the same time that Van Geuns was doing the same. Van der Valk describes the trip aboard a ship packed with his wildlife cargo and passengers travelling to Amsterdam via Mecca and the Suez Canal. The journey started in Belawan and continued to the Port of Sabang located on an island off the north coast of present-day Banda Aceh. From Sabang, the ship travelled across the Indian Ocean to the Port of Mukalla in Yeman and then to Jeddah, where many of the passengers disembarked. The ship carried on through the Suez Canal and Port Said before setting off for Amsterdam (Van der Valk Reference van der Valk1940: 245–63).

Van Geuns must have taken the same route on his journeys transporting animals. On 29 August 1927, Van Geuns arrived in Germany with 33 orangutans from Sumatra. These were sold en bloc to John Ringling of the Ringling Brothers Circus fame who personally travelled to the port of Rotterdam to take the delivery (Jones Reference Jones and de Boer1982: 21). Only eight months later, in April 1928, Van Geuns brought back a haul of 44 more orangutans from northern Sumatra. His return trip that April, however, did not end in Amsterdam, but instead landed in Marseilles, France. Ruhe sent most of the orangutans to a small zoo he owned in Cros de Cagnes, France, called the Centre d'Acclimatation de la Riviera. A group of the orangutans also ended up in the Cannes Zoological Gardens (Weigl Reference Weigl2011: 104–105). Sir Hesketh Bell, a retired British colonial official who had retired to Cannes, visited the zoo in late April, just a few weeks after the orangutans had arrived from Sumatra. He claimed that at least 60 orangutans had recently arrived at the zoological garden in Cannes, and he was told that another group of 46 had landed in London just a few weeks earlier. Bell was stunned to see such a large group of orangutans in France, and he protested against the trade with a letter to the editor in The Times of London, published on 15 May 1928. In the letter, Bell described his experience viewing the orangutans from Aceh. He wrote:

Up to quite recently a live orang in Europe was a rare spectacle, and the sudden appearance of more than a hundred of these distant cousins of ours must be of more than passing interest, not only to those who are students of the ‘ascent of man’, but especially to all who are keen on the preservation of tropical fauna…. The suddenness of this large influx of specimens of the great ape, which is the nearest approach to man, indicates that some method of capturing them wholesale has recently been adopted. I learn that such is the case. It seems that a European in Sumatra has discovered the favourite habitat of a considerable number of orang-utans…. One is tempted to ask whether the Dutch authorities in the Far East are going to continue to permit the wholesale razzias that are now carried on in Sumatra among the nearest approach to human beings, not for the advancement of science – which might be some excuse – but merely, as in the case of the slave-raiders of old, to enable a few persons to make great pecuniary profits.Footnote 11

Bell's letter reveals numerous aspects about social and cultural identity in certain parts of Europe at the time. Louise Robbins (Reference Robbins2002: 187) observes that human affairs have always permeated writings about animals. Animal metaphors were at the centre of the complex discourses about science, colonialism, animal welfare, capitalism, slavery, human rights, democracy, and other topics that dominated the cultural history of the period. Humans have often attached these categories to unique species or megafauna, such as elephants and giraffes, that touched on the sensitivities of a large segment of society. It was particularly the case with orangutans, as the morphological similarities between humans and apes appealed to the sympathies of many passers-by, such as Bell, who saw in orangutans reflections of themselves.

While Sir Hesketh Bell took a recent interest in wildlife policy and protection in the East Indies – he remarks in his personal journal that the object of his letter was to get the Dutch colonial government to stop the “wholesale outrages” – he had a background of civil service in Africa.Footnote 12 Between 1905 to 1924, Bell served as the Governor of the Uganda Protectorate, Northern Nigeria Protectorate, the Leeward Islands, and Mauritius.Footnote 13 During his time in Uganda, he had been embroiled in debates about the tsetse fly and role of wildlife culling as a sanitary measure (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie and MacKenzie1990: 188). In 1906, Bell passed legislation that regulated game hunting with a license and permit system based on colonial social hierarchies and hierarchies of fauna.Footnote 14 Bell was also a passionate big game hunter and was emblematic of the “virtuous” sportsman of the period, who hunted for spiritual fulfilment rather than for subsistence or financial gain (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1988: 12; Ritvo Reference Ritvo1987: 276–81). After retiring in 1924, Bell moved to Cannes but continued to travel, including a trip to the East Indies from 1925 to 1926 to study Dutch systems of colonial governance. Bell was escorted across the archipelago by high ranking officials and was provided with a Dutch colonial version of politics in Indonesia (see Bell Reference Bell1928). These experiences undoubtedly played a part in his call for action to protect orangutans.

Bell and others were concerned with the violence inflicted on orangutans as they were captured, caged, and transported around the world, comparing the situation to slavery. To support the comparison, Bell outlined his version of how the apes were caught and moved to the ports. According to Bell, collectors visited villages in the interior where they hired a “small army of natives” and travelled with them to the “virgin forests of which the gigantic apes have their homes”.Footnote 15 The native trappers scared the orangutans until they all assembled in a specific tree. The trappers then cut the surrounding vegetation until only a few trees were left standing in which the orangutans resided, then they were felled. Strong nets were used to secure the animals who survived the fall. Some orangutans were wounded and died in the process. If the baby was the target, as was often the case, the parents were killed and the baby taken from the parents’ grasp. Some collectors preferred young orangutans, as they did with other species (see Nance Reference Nance2013: 18; Rothfels Reference Rothfels2002: 54), because they could be tamed quickly, were less dangerous than adults, and were easier to acclimate to captivity. However, zoo officials desired reuzen orangutans for their displays and so trappers would still put effort into searching for large males (Van der Valk Reference van der Valk1940: 132–3). The captives were then forced into wooden or bamboo cages and carried out of the forest. From there it was almost certain that the orangutans faced their demise “cooped up in cages in which they cannot stand upright” on long journeys around the world.Footnote 16 In fact, Rijksen and Meijaard (Reference Rijksen and Erik1999: 137) state that less than 40% of orangutans survived the trip and most died within their first year overseas. Subsequent letters speculated how many orangutans must have been killed in the process of trapping and in transport.

It is unknown where Bell learned of the methods for trapping orangutans, but some of the most detailed descriptions from the period come from the writings of A.C. van der Valk. After leaving his position on the oil palm and rubber estates in Deli, Van der Valk moved to a village near Langsa to the northwest of Deli so that he could hunt and catch animals. In a book about his experiences in northern Sumatra, Van der Valk describes his attempts to catch orangutans in the forests near his home. He and a group of local trappers spent days tracking orangutans, locating them high in the canopies of durian trees. Once they found an individual of interest and a suitable location, they cut the surrounding vegetation and felled the nearby trees to prevent escape. The crew then waited below with nets and weapons, as they knew the orangutan would eventually descend from the tree. Once the ape reached ground level, the trappers ambushed it with nets and rattan ropes. It was a dangerous affair for both the orangutan and the trappers, and the animal often won the battle. In the first few instances described by the author, the orangutans broke through the fibrous nets with their incredible strength and sharp teeth, and fended off the attackers, returning back into the forest canopy (Van der Valk Reference van der Valk1940: 105–10). When the catchers finally netted an orangutan, they did so by keeping a cage with steel bars beside the tree to immediately detain the animal for transport. This version of events is slightly at odds with Bell's description, but catching animals was often dependent upon context-specific factors and methods differed on a case-by-case basis.

Tales of wildlife trapping and collecting and the violence inherent to the process were common before the First World War; in fact, they were celebrated in movies, radio programs, and books. According to Nigel Rothfels (Reference Rothfels2002: 63), “catching stories” prior to the second decade of the twentieth century were about killing, flaunting graphic imagery of blood, violence, and death, while expressing white, masculine power over both indigenous peoples and non-human species. Only peripherally were the stories about catching animals. Around the time of the First World War, humanitarian concerns and the promotion of animal rights and environmental protection were brought to the fore of society, and zoo officials, animal catchers, and others feared that such stories would threaten the future of the animal trade. Soon the discourse of traders and trappers shifted to promote their practices as civilised, humane, and for the benefit of scientific knowledge, even if animal catching practices remained the same.

Hesketh Bell's letter in The Times set off a flurry of responses in newspapers in Britain, the Netherlands, and colonial Indonesia. It is, of course, impossible to know precisely how each member of the public interpreted the arrival of so many orangutans in Europe. Ian Jared Miller (Reference Miller2013: 137) comments that “[r]eception is the bogey of cultural history”. To complicate matters, most of the letters in the newspapers concerning the trade are anonymous, and so we are unable to discern the social positioning of the authors. Some people must have welcomed the arrival of the apes and the opportunity to see creatures that just a few years earlier were a rare sight in Europe. In the public responses to Bell, however, we mostly see a public concerned with the safety of orangutans and their welfare in the forests of Sumatra. The writers called for the protection of orangutans and other primates, oftentimes stating that they should take precedence due to their similarities with humans. Others were alarmed about the ethical implications of their capture and transport; they were mortified by the violent methods used to trap and move orangutans from their forest homes. Some writers even called for the closing of zoos and for an end to laboratory research on orangutans and other primates based on ethical grounds. Almost all the letters demanded their protection in Sumatra and an end to the wildlife trade (Algemeen Handelsblad 1928a; Algemeen Handelsblad 1928b; Algemeen Handelsblad 1929a; Algemeen Handelsblad 1929b; Hume Reference Hume1928; Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant 1928a; Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant 1928b; Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant 1929; Paterson Reference Paterson1928; Soerabaiasch Handelsblad 1928; The Times 1928a; The Times 1928b; Zelle-Mense Reference Zelle-Mense1928).

Representatives from the major European and North American environmental organisations at the time also wrote letters to Bell, explaining the work they were already doing to slow the orangutan trade. P. Chalmers Mitchell, secretary of the Zoological Society of London, replied with a letter in The Times of London, writing that he had taken steps through Dutch friends to advocate the prohibition of such animal collection methods. In an attempt to defend the London Zoo's orangutans, Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1928a) stated that they reluctantly accepted the apes and that they had recently refused the purchase of all orangutans, even when they were “offered on very advantageous terms”. At the end of his letter, Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1928a and Reference Mitchell1928b) called for an end to the trade in all monkeys and anthropoid apes, unless before shipping they were “tame enough to be handled and examined”. For Mitchell, it was not so much that the trade had to end, but that the methods of capture had to be more humane and that the standards of acclimatisation had to be improved. Such a response is to be expected from a zoological representative.

The letters of protest also touched the nerves of a reader in Sumatra for different reasons. The anonymous respondent, who very well might have been A.C. van der Valk, wrote his or her critique of Bell's letter in the 28 August 1928 issue of the Deli-Courant, a newspaper based in Medan in northern Sumatra. The author of this letter appears to have been a wildlife trader, and responded by defending the practices of wildlife catching and the orangutan capture methods. The person wrote that, “Sir Heskett (sic) Bell, the ex-governor of Mauritius, has done in The Times a curiously childlike and silly story about the trapping of orangutans; at least as he himself imagined how the animals were trapped. How that story has been conceived is beyond me…. In any case, in May (1928) when I was with the people who transported orangutans to London, I was able to see that such follies (as described by Bell) are impossible” (Deli-Courant 1928). The writer continued that they took the utmost care with the animals both during capture and in transport, and that capturing orangutans was necessary for science and the betterment of society. The trapper also disparaged Mitchell and his take on the trade in orangutans. The author moved on from Bell and accused Mitchell and the British of being stuffy, for there are still “hundreds and thousands of orangutans in Sumatra” (Deli-Courant 1928). The writer then closed the letter with a question: “Is it not interesting to science, that at this moment in almost every zoo in Europe can be seen a very large adult orangutan and its baby, a kind which some years ago was seen very sporadically in Europe?” (Deli-Courant 1928). In this letter, we see that the author described the trade as humane with care given to the orangutans—the primary goal of the trader, after all, was to keep the orangutans alive until sale. Second, the author calls attention to the necessity of the trade for the science that many conservationists also promoted and practiced.

Unfortunately, there are no responses to the wildlife trader's letter, but P.G. van Tienhoven wrote to Bell on 5 July 1928. He reassured Bell that the Netherlands Commission for the International Protection of Nature was working with the Governor-General in Buitenzorg (Bogor, Indonesia) and the Minister of the Colonies in The Hague to propose legislation banning the trade in threatened species.Footnote 17 Van Tienhoven promptly translated Bell and Mitchell's letters and passed them on to government officials, eventually landing them on the desk of the Governor-General of the East Indies. His goal in these actions was to continue to put pressure on the colonial government and members of the Volksraad – a People's Council in the Indies comprising both Dutch and Indonesian elected members and members appointed by the Governor-General – to pass ordinances banning the trade in what the Commission considered to be threatened species. A door had opened for the Commission to pursue their goals and Van Tienhoven stoked the fire. He not only sent communications to Dutch officials, but also to prominent media outlets at home and in Indonesia to keep the issue in the public's eye. He maintained on-going communications with J. Kalff, the editor-in-chief of the Algemeen Handelsblad. In one letter, he wrote that he was appalled at the “incomprehensible slowness of the Government here and in the Netherlands Indies” for continuing to postpone a ban on the export of orangutans.Footnote 18 He lamented that the media attention in other countries given to the orangutan problem continued to cast on the Netherlands a “bad light across the whole scientific world (geheele wetenschappelyke wereld)”.Footnote 19

The practice of conservation around the world was often influenced by colonial rivalries, public debates, and premised on ideologies of modernisation and civilisation (Gissibl Reference Gissibl2016: 119). This is as true of colonial Africa, as described by Bernhard Gissibl, as it is of Indonesia. Many Dutch colonial policies and practices were not only actions taken with an eye toward the colony or the economy, but also with another in the direction of their colonial neighbours. Members of the Dutch Parliament (Tweede Kamer) often discussed policies in comparison with actions taken by the British and French, in particular, who also had colonies in Southeast Asia. Van Tienhoven seemed keenly aware of the Dutch position in the field of science and conservation in comparison to the other imperial powers of the day. In fact, he had been in close communication with many of the world's prominent scientists and conservation leaders since the first decade of the twentieth century, including, among many others, C.W. Hobley, the director of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire in London, William Hornaday, H.J. Coolidge, the secretary of the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection, and Paul Sarasin, a Swiss naturalist, ethnologist, and early leader of the international movement. Van Tienhoven wanted the Commission to be a world leader in conservation, but in order to achieve that goal he had to convince the colonial government of his plans. Historian Bernhard Schär (Reference Schär and Fischer-Tine2016: 286) recently wrote that the Dutch used crises to “engage in a kind of ‘politics of embarrassment’, thus managing and exploiting the fears of an imperial ‘Dwarf’ to lose face in a game of ‘Giants’”. Van Tienhoven, it appears, aimed to use the public backlash over the orangutan trade to put pressure on the Dutch government to act on both species and habitat protection, hoping the protests would ignite a greater movement to implement nature reserves in Sumatra.

Other European powers had confronted environmental concerns in their colonies prior to the orangutan situation in the late 1920s, as had the Dutch. It was mentioned earlier in this article that wildlife laws had passed in many colonial African countries prior to the turn of the twentieth century, but legal protections for the orangutan came later. At the London Convention of 1900, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and the Congo Free State signed a treaty to cooperate in protecting wildlife in Africa, although it was never ratified and its enforcement rested in the hands of individual colonial governments under pressure from conservation lobbies and public opinion (Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, Helen and Helen2014: 214). In 1908, the Netherlands Society for the Protection of Animals (Nederlandsche Vereeniging tot Bescherming van Dieren) wrote to the Minister of the Colonies, suggesting that the Dutch were out of step with international opinion and practice and that legislation was needed to protect fauna in the East Indies. The colonial government succumbed to the pressure in 1909 and announced the Ordinance for the Protection of Certain Wild Mammals and Birds. Under this ordinance, however, tigers and all primates and monkeys were excluded on the grounds that they were a threat to humans and their agricultural plots. Boomgaard (Reference Boomgaard1999: 265) explains that the 1909 Ordinance gave protection to all wild mammals and birds, but “excepted so many categories of animals, namely all animals that were deemed harmful, that its effect was practically nil”. In 1924, the Dutch passed an ordinance banning the hunting of most protected species in Indonesia without a special permit, including rhinoceros and orangutans, but the law did not protect those species from trapping and transport while alive.Footnote 20 It would have had little bearing on scientific and zoological collections, except for researchers and museums who wanted animal skeletons, and would have had the greatest impact on native peoples and Chinese traders who collected animal parts, including rhino horn and ivory particularly for Asian markets. The 1924 Ordinance was also limited to Java and thus offered no protections to orangutans, which the Dutch corrected with an additional decree in 1925 (Boomgaard Reference Boomgaard1999: 269).Footnote 21

Environmentalists and scientists were advocating for the protection of a threatened animal due to fears of its extinction, yet they actually knew very little about orangutan populations in Indonesia. At the time, researchers had yet to gather accurate information regarding the habitats, populations, and social behaviour of Sumatran orangutans. Researchers only started to conduct orangutan surveys in Sumatra and Borneo in the 1930s (Rijksen and Meijaard Reference Rijksen and Erik1999: 139). Officials only knew that orangutans were arriving in zoos around the globe at an alarming rate – they were not only traded to Europe and North America, but also to Japan, Australia, and many other countries around the world. Van Geuns was certainly not the only trader, but he was the one who received the most attention in the media. Between 1919 and 1920, ten adults and fourteen or fifteen young arrived in traveling menageries and zoos in Japan (Kawata Reference Kawata and Kisling2001: 304). The Dutch were also selling orangutans to other countries, and in 1929 they ended orangutan sales to Australia because of reports that Australian zoos were in turn selling the apes to institutions in the United States (De Courcy Reference de Courcy and Kisling2001: 198). There was great concern among many Europeans over the future of orangutan populations in Sumatra and Borneo, but at the same time they were also used as a figurehead for a broader movement to gain rights to land, expand existing nature reserves, and construct more expansive conservation areas in the East Indies.

The Orangutan Trade and Colonial Policy

It was an advantageous historical moment for the Netherlands Commission for the International Protection of Nature and others protesting the exploitation of flora and fauna in Indonesia. Bell's letter brought the debate to the public, which put pressure on colonial governments to act. In May 1929, only a year after Bell's letter to the editor, the Fourth Pacific Science Congress was held in Bandung, Java under the auspices of the Netherlands Indies Science Council and the Netherlands Indies Government. The Minister of the Colonies, the Governor-General of the East Indies, and the top scientists in Indonesia at the time were in attendance, along with an estimated 250 overseas delegates. Global leaders of science and conservation travelled to Bandung from all over the world—twenty-four countries in total were represented. It was a big event for the colonial government and the Science Council and they had spent years planning the conference and the excursions that were part of it (Proceedings of the Fourth Pacific Congress 1930: 5–24).

Nature protection was one of the central themes of the Congress. In the deliberations on nature protection in the Pacific World, attendees discussed scientific collections and the global wildlife trade. Van Tienhoven was in attendance as well as other leaders from numerous international nature protection organisations. Three resolutions were passed with regard to the wildlife trade: “The creation of a standing committee for the protection of nature in and around the Pacific. The promotion of the passage of governmental regulations by which the importation of all living specimens or skins, feathers or other parts of the bodies of wild animals will be prohibited, unless the consignment is accompanied by a license issued by proper authorities. The limitation of unrestricted collecting of plants and animals in the Pacific Islands” (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1930: 363). The outcomes of the Pacific Science Congress placed pressure on the Dutch colonial government to regulate the wildlife trade, especially since it was the host of the event, while applying similar pressure to other colonial regimes in Southeast Asia. Scientists and statesmen from around the world were now paying attention to wildlife protection in insular Southeast Asia, which the Congress considered part of the Pacific.

Both the British and Dutch colonial governments debated the resolutions soon after the Congress – in fact, they cooperated closely in creating legislation specifically aimed at curbing the orangutan trade from Sumatra across the Straits of Melaka to British Malaya. Fiona Tan (Reference Tan and Barnard2014: 155) points out that a few years earlier, in 1928 and again in 1929, prominent Dutch government officials reached out to the Singaporean government, requesting that the British consider legislation banning the importation of orangutans. Dutch conservation leaders knew that any serious attempts to curtail the trade would require political action on both sides of the Straits of Melaka, as well as in European ports. Van Tienhoven also believed that if the British passed legislation, the Dutch would soon follow. In 1930, the British approved an order prohibiting the importation of orangutans in the Malay States, Straits Settlements, and Singapore.Footnote 22 A year later, the Dutch passed their own export ban on protected species, making it illegal to catch alive, trade dead or alive, or hold protected species in captivity.Footnote 23 The measures were in large part due to the stream of orangutans taken from Sumatra across the Straits to Melaka, Penang, and Singapore. Both the British and the Dutch cited the letters of Hesketh Bell and P. Chalmers Mitchell, the orangutan crisis of the late 1920s, and the Fourth Pacific Science Congress in debates over the legislation. British officials called attention to the “strong protest” and adverse publicity in European newspapers, certainly referring to Bell's letter and the following debate, because of the large numbers of orangutans transported from Indonesia to Singapore, and then on to Europe.Footnote 24 The British in the Straits Settlements urged customs officers to enforce strict observance of the ban and steam-engine companies were requested not to transport orangutans without the permission of the colonial government.Footnote 25

It appears from the records that the orangutan trade slowed in the years following the legal protections put in place on both sides of the Straits of Melaka, although it was an impossible task to eradicate the practice completely. The orangutan habitat crossed the highlands of northern Sumatra and continued into the coastal lowlands along the Indian Ocean to the west and the Straits of Melaka to the east. Monitoring and regulating the goods, people, and non-human species that passed through the ports was just as futile a task as establishing control over the highland interior. Eric Tagliacozzo (Reference Tagliacozzo2005) shows that neither the British nor the Dutch were able to effectively stamp out piracy and trafficking in drugs, weapons, goods, people, and also non-human species such as orangutans, even as they heightened surveillance measures along the coast, increased the numbers of colonial agents who patrolled the seas and ports, and implemented a host of new rules and regulations. Dutch control in the southern highland interior of Aceh was equally limited. The Dutch were unable to effectively consolidate the highlands into the colonial territory until after the Dutch-Aceh War around 1913. Even then, the colonial government in Aceh had to assign permanent military patrols in Gayo Lues and the Alaslands, the region that would become the heart of the Gunung Leuser Game Reservation (Wildreservaat Goenoeng Leuser) in the 1930s, attempting to subdue local resistance that continued until Indonesian independence.Footnote 26 Policing the interior of Aceh was not an easy task for the Dutch, owing to its dense tropical forests, mountainous geography, and the ability of indigenous peoples to avoid contact with colonial officials by manoeuvring along footpaths throughout the highlands. Trappers and traders, it seems, were often able to evade enforcement both in the interior and in the ports. The fines imposed on traders were also not deterrents, as they were less than the price orangutans commanded on the global market.

Van Geuns and other collectors continued to take orangutans from northern Sumatra to locations around the world. Some collectors had already developed close networks within the government and local communities to work around the laws, while others moved into the shadows to smuggle species out of the Indies. Wildlife traders, scientists, and others obtained permits from the Governor-General to collect species for scientific purposes, but the colonial government did not grant permits for all species or to all persons. By the mid-1930s, trade in Sumatran and Javan rhinoceros were prohibited, even to Dutch scientific institutions, as they were feared to be on the verge of extinction.Footnote 27 Van Geuns continued to return to Europe with small groups of orangutans until the Second World War. He had secured close relationships with colonial officials and was a key informant for regional authorities, as were other wildlife traders. A.C. van der Valk wrote to Van Tienhoven on 20 September 1927 from Aceh to describe the global market for rhinoceros. He cited Van Geuns as his source of information. The letter explained that Van Geuns had outlined for him the cost of a dead rhino body, its skin per square foot, its horn per kilogram, and bottles of its urine and blood.Footnote 28 C.R. Carpenter, a prominent American primatologist, learned about orangutan populations from Van Geuns on his research trip to Aceh in 1937. Dutch officials told Carpenter that Van Geuns could provide the most accurate information on the spatial distribution of orangutans in northern Sumatra.Footnote 29 The officials provided Carpenter with Van Geuns’ contact information in Aceh. Van Geuns also placed advertisements in Sumatran newspapers throughout the colonial period for his business of selling and buying animals. According to records, he was the first trader to bring orangutans out of the Indonesia after the Second World War in 1946 (Jones Reference Jones and de Boer1982: 21). In fact, it was not until March 1954 that Indonesian authorities arrested Van Geuns for an advertisement in a Medan newspaper in which he offered to purchase numerous species that were protected by law.Footnote 30

Conclusion

This article on the colonial history of the orangutan trade is intended to draw attention to the historical processes that led to environmental conservation in northern Sumatra. The practice of protecting nature is a human construct and this history highlights some of the contexts behind colonial decisions to pursue the creation of wildlife ordinances in colonial Indonesia. It began with a look at some of the causes of that trade, linking in particular animal-human engagement in northern Sumatra during the late colonial period to large-scale agricultural development. In the early twentieth century, the Dutch built scientific research institutions on plantations in Sumatra to study horticultural techniques and improve economic output. Many researchers in these institutions were connected to science networks that spanned the globe. Knowledge and information spread through these networks, but so too did non-human species to zoological institutions and laboratories. I suggest that orangutans were the most sought-after Sumatran species at the time in Europe and elsewhere. This article then interrogated public responses to the growing orangutan diaspora in Europe, which informed us of the sociocultural views of certain species and, more broadly, of society at the time, and the ramifications of public debates in the metropole with state action and legislation in the colonies.

Environmental conservation played out in similar ways in colonial spaces around the world at the turn of twentieth century – in the 1880s with elephants in East Africa, for instance, and with birds-of-paradise in New Guinea a few decades later. Following public pressure, legal protection was given to orangutans both in colonial Indonesia and across the Straits of Melaka in the British territories. However, social and legal regulations and wildlife ordinances were only one piece of the nature protection puzzle for Dutch conservationists in Indonesia. The next step was to gain rights to the land where the Sumatran orangutan lived and construct nature reserves, or natuurmonumenten, to protect its habitat. Conservation was only possible due to indigenous dispossession and the accumulation of territory by the state, and the Dutch military had started the process with an invasion into the Gayo and Alaslands in 1904. The orangutan trade and the subsequent crisis not only impacted import-export policies and border control measures in the maritime realms, they were also central to the control of land and the borders created on land in northern Sumatra. Dutch conservation leaders, particularly Van Tienhoven and F.C. van Heurn, were certainly interested in protecting other threatened species, especially the Sumatran elephant and rhinoceros, but the orangutan controversy opened a window for them to pursue loftier goals, such as habitat conservation. Van Tienhoven and Van Heurn collaborated with the Governor of Aceh, A. Ph. van Aken, military officials, village leaders, and others to acquire indigenous territories and create the Leuser Reserves in the 1930s. Orangutans, however, remained in a precarious position and the trade continued.

The wildlife ordinances did, however, save face for the Dutch on the colonial stage. The government had cleansed its hands of responsibility. It had displaced the central role of colonialism, science, and entertainment in the orangutan trade and undermined wildlife protection laws by handing out collection and trade permits. It does appear that the orangutan trade slowed in the 1940s, most likely in part as a result of the chaos and instability of the Second World War and decolonisation together with environmental regulations, the creation of nature reserves, and policing. Public concerns about the apes did not arise again until the 1960s and 1970s. In 1973, the International Union for Conservation of Nature brought attention to orangutans and other threatened species around the world by adopting the CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) agreement, a multilateral environmental treaty to protect endangered flora and fauna (Heise Reference Heise2016: 107). Today, plantation expansion and habitat loss pose the largest threats to orangutan populations in Sumatra and Borneo. The campaign to protect orangutans remains a transnational effort comprised of collaboration and organisation at all geographical scales, but in northern Sumatra, many Indonesian activists, scholars, and scientists now lead the movement.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. Work by this author was supported by the Social Science Research Council, Cornell University, the American Institute for Indonesian Studies, and the American Historical Association.