Talking Business

We last saw Faduma,Footnote 1 a Somali refugee living in-transit in Jakarta, Indonesia, in March 2019. We were sitting in a café at the bottom of a low-cost apartment block in South Jakarta; she was sipping a pink milkshake and we had water. We noticed that Faduma's English had improved considerably over the two months since we had last been together. Faduma was never shy, but in this meeting, we sensed that she had gained more confidence. In a way, she was actually the one to lead the conversation and set the topics while we only asked a few intermittent questions. Our conversation proceeded in leaps and bounds and covered a wide range of topics: unmarried Somali mothers and the lack of healthcare for their babies; the suicide of a young Somali boy; a new self-help group for Somali women. Faduma did not spare any criticism for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), a refugee organisation, which offered her some support but usually came “too little, too late”.

When we first got to know Faduma, she had an informal job as interpreter and was involved in a nutrition program for Somali children.Footnote 2 In the time since, she impressed us by cultivating a wide circle of friends, drastically improving her networking skills and honing an ability to spot opportunities such as workshops, free skill trainings or funding. Her outgoing personality supports her search for opportunities. By our most recent meeting, she had become quite outspoken about why she wanted to quit her job as an interpreter with a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) in order to create more free time for activities within the community.

As the conversation ranged across various topics of interest, she suddenly made a business proposal that took us by surprise. She asked us to invest Rp5 million (approximately US$365) so that she could start a grocery supply business for newcomers to Indonesia from Somalia, Yemen and Eritrea who often did not know the best places to shop in Jakarta. Customers would be able to place their orders with Faduma and have their groceries delivered to their homes. In a city like Jakarta, notorious for its traffic jams, this kind of service industry has grown rapidly in recent years. Those who can afford to stay at home now order everything they can online. The armada of motorbike deliverers in Jakarta's clogged streets has grown steadily. Although Faduma did not have a motorbike, she seemed convinced of her business idea's potential. We were less convinced by it and expressed our unease about charging newcomers higher prices, assuming that they too would soon run out of money, as we have observed many times in similar situations in the past. At this point, our meeting then came to a quick close.

Faduma is one member of a group of Somali women whom we have met in Jakarta during our long-term engagement with refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia, which began in 2010. While Somalis were a minority among asylum seekers coming to Indonesia a decade ago, they are now the second largest group after Afghan asylum seekers. Their arrival in Indonesia has triggered a number of questions amongst refugee organisations and amongst Indonesian authorities, partly because Indonesia has not typically been a destination country for Somalis who have tended to seek refuge in neighbouring countries such as Kenya, Eritrea and Yemen (Carrier Reference Carrier2017; Scharrer Reference Scharrer2018) or have tried to reach countries in the Global North (Kusow and Bjork Reference Kusow and Bjork2007).

By using the example of Somali refugee women carving out an existence in a rather hostile environment, this article seeks to demonstrate the advantages and disadvantages of informal refugee protection, which seems to be a drawcard that Indonesia, a “deviant destination” (Jaji Reference Jaji2019), offers unintentionally. Deviant destination is used here to capture perceptions held by potential migrants and asylum seekers of a country, which they commonly do not perceive to be a welcoming host or a particularly attractive destination with plentiful opportunities to newcomers. Generally speaking, deviant destinations can be located ‘along-the-way’ in long-existing migration corridors, but can be located also well ‘out-of-the-way’ and far away from the usual routes. In lieu of viable alternatives, they consider those countries second-best options and suitable for temporary stays. More importantly, deviant destinations, more often than not, tend to be outside the desired destination countries in the Global North (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh Reference Fiddian-Qasmiyeh2020). While Indonesia has generally been perceived as a sending state for both labour migrants and asylum seekers, and even as the number of people who leave Indonesia outnumber incoming migrants and asylum seekers, it would be wrong to ignore that Indonesia has now also become a receiving country. With very few other options available, Indonesia has become a frequent choice as a temporary destination country for Somali asylum seekers and refugees.

Focusing on refugee governance in Indonesia, predominantly characterised by the absence of state protection offered to refugees, this article highlights how Somali refugees work through the specific socio-political context of a deviant destination, with its particular legal environment, economic system and various cultural and religious factors. While malfunctioning institutions, weak rules of law, corruption, large shadow economies, poor human rights records and weak civil societies might appear unattractive at first sight, deviant destinations offer certain opportunities to those with special people skills who can quickly learn to navigate the system, adapt to the overall circumstances, spot opportunities and build functional networks with co-ethnics and Indonesians. The phrase ‘making do’ is used here for the combination of creative, tolerated but unauthorised, and suboptimal ways refugees earn a living, despite the fact that refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia are prohibited from earning an income (Palmer and Missbach Reference Palmer and Antje2019; Sampson et al. Reference Sampson, Robyn, Gifford and Savitri2016). With so many governments relying on precarity as a condition through which to control refugee lives in transitory states at large, our research question focuses particularly on how some individuals, exemplified here by Faduma, can make relatively fast improvements to their overall living situations and achieve some kind of social upward mobility – potentially against all odds.

Anthropologists sometimes tend to accentuate the microcosm over the macrocosm and the global powers, processes and presences that often govern refugees’ lives, whereas political scientists tend to overlook the powerful individual coping strategies of many refugees. By embedding the microanalysis of coping mechanisms and livelihood strategies of Somali women into the macropolitical context of the forced dispersal of Somalis and their global diaspora, this article is composed of three main sections. First, we offer an overview of the making of the Somali diaspora and the closure of migration pathways that has led to an increase in the number of Somalis coming to Southeast Asia, including Indonesia. Second, we analyse the absence of formal protection for refugees and evaluate the alternative protection measures available to refugees in Indonesia. In the third part of this article, we present our ethnographic data and analyse our case study. Here, we pay special attention to Faduma's journey to Indonesia, her daily struggles to survive and her community activism, which is driven by her desire to gain new skills and to build the networks needed to cope with the many challenges of life as a refugee. Amongst her Somali peers and the wider refugee community in Indonesia, Faduma's experiences are exceptional. They are exemplary compared to the migratory resilience, creativity, aspirations and daily struggles of larger refugee groups, as often pointed out by the adherents of the autonomy of migration school (e.g., Casas-Cortes et al. Reference Casas-Cortes, Sebastian and John2015; Nyers Reference Nyers2015). Against all odds, coming to Indonesia enabled Faduma – a young black woman emigrating from a conflict-ridden country with few social networks and resources at hand – to embrace a kind of social mobility which most likely, had she stayed in Somalia, would not have materialised. In our most recent meeting with her, it was clear that Faduma was very aware of the social mobility potential of her current life in Indonesia in contrast to her old life in Somalia; she openly acknowledged this several times throughout our conversations when it came to illustrating the alliances she had forged with expatriates and well-off Indonesians. In our analysis, we attempt to explain what might have prompted Faduma's rather exceptional trajectory. In particular, we pay attention to structural and agential factors that are important for understanding the irregular migration of Somalis to Indonesia and their tolerated residence there (Bakewell Reference Bakewell2010; Squire Reference Squire2017).

The contrast between the micro-level of Faduma's daily survival in Jakarta and the macro-level context of exclusionist global migration policies presented here will enable the extrapolation of more general findings about refugee autonomy in dealing with global deterrence policies and insufficient protection at the local level. Movements of migrants, as Sandro Mezzadra (Reference Mezzadra2020: 433) points out, are characterised “by an amazing stubbornness and by autonomous dynamics of mobility” that help overcome those who seek to contain and manage them. However, he also reminds us that “border struggles are far from over once [borders] are crossed” (Mezzadra Reference Mezzadra2020: 437). Refugees encounter the macro-level consequences of global restrictions of movement when they end up trapped in transit. In transit, they are confronted with measures of containment and face an omnipresent risk of deterrence when seeking to realise their onward migratory aspirations. However, in-transit asylum seekers and migrants can test the limits and ranges of their mobility on the micro-level. This can come, at times, with high financial and emotional costs for the individual but also offers a great impetus for the collective.

While the article highlights the case of an extraordinary Somali woman in an urban refugee community and her resilience, creativity and adaptability in overcoming challenges and making use of a range of available options for both self-realisation and community building, it intends neither to glorify an individual with the potential to ‘make do’, nor to downplay those who fail to advance themselves by taking advantage of the opportunities irregular migration might offer. ‘Making do’ is by no means an option for all people faced with the reality of being an unwanted refugee in a transit country. Unintentional refugee protection arising from infrequently and sporadically enforced migration controls provides only temporary respite and not a durable solution for many people's precarity (Missbach Reference Missbach2020; Adiputera and Missbach Reference Adiputera and Missbachforthcoming). The chance to highlight the reality of refugee's transitory life stages and existences in limbo is what we consider the most important theoretical contribution of this article. While there is a vast literature on women's social mobility and adjustment capacities in resettlement countries or final destination countries (e.g. Çağlar and Schiller Reference Çağlar and Schiller2018; Franz Reference Franz2003; Warringer Reference Warriner2007), little attention has been given to how such capacities play out when journeys are delayed or when peoples’ lives become mired down in hostile transit situations. In these scenarios, there is often little assurance on whether their investments in local language, people and networks, often collectively referred to as place-making, will be of any lasting benefit (Bauder and Gozalez Reference Bauder and Dayana A.2018; Crawley and Jones Reference Crawley and Jones2020; Hoffstaedter Reference Hoffstaedter2014).

The interviews and observations reported in this article have been collected throughout several stages of fieldwork. At first, our encounters with Somalis in Indonesia were quite casual, until 2018 when we decided on a more focused approach. Trish Cameron, who at the time was undertaking pro bono work for an Indonesian refugee organisation, joined Antje Missbach's project and agreed to reach out and screen potential interlocutors. Before conducting interviews, we consulted a number of people who know the Somali community well in order to ourselves obtain background information. We then introduced our research project to the Somali community and invited volunteers. Between April and September 2018, semi-structured interviews were conducted with four Somali men and eight women. All interviews were conducted in English with interpreters present for two of the interviews. After these initial interviews, we decided to focus our study primarily on Somali women, partly because male members of the Somali diaspora have received substantial attention from other scholars (Kleist Reference Kleist2010; Omar Reference Omar2013). We arranged for additional follow-up interviews in 2018 and 2019 with a number of our key interlocutors. We recorded and transcribed our interviews, which tended to be open-ended and variable in intensity, ranging from informal conversations to life history approaches. We met our interlocutors in public spaces (cafés, malls, shopping centres) and private places (their homes). As part of our wider research interests and work commitments, we also interviewed representatives from the UNHCR Indonesia office and the Indonesian Foreign Ministry, as well as experts on the Somali diaspora. Our inquiries in Jakarta were also complemented by interviews and conversations with two Somali academics and several Somalis who were living in Melbourne. During our frequent absence from Jakarta, we kept in touch with our key informants via social media and direct messaging. The latest stint of fieldwork, planned for April 2020, was cancelled due to the global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The Global Somali Diaspora and Its Search for Safe Places

Somalis are known for their migratory history and their distinct diaspora (Omar Reference Omar2013). These networks predate the ongoing civil war that has made Somalia one of the largest refugee-producing countries in the last two decades and are essential in the facilitation of (ir)regular journeys and temporary integration. A nomadic heritage and a tradition of long-distance migration entrench mobility in the Somali way of life (Horst Reference Horst2006a, Reference Horst2006b; Omar Reference Omar2013). Whereas many past migratory journeys out of Somalia were driven by a desire for adventure, education and prosperity, the more recent history of Somali emigration is characterised by forced migration (Bokore Reference Bokore2018; Kleist Reference Kleist2004; Omar Reference Omar2013). Since the outbreak of the civil war in Somalia in 1991, more than two decades of political instability and violence have resulted in the displacement of an estimated 2.1 million people within Somalia and the flight of tens of thousands more out of the country in search of safety. Repeated severe droughts and other natural disasters have also driven migration. In 2016, it was estimated that about fifteen per cent of the population of fourteen million had left Somalia to seek refuge in nearby Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Yemen, as well as further afield. Onward migration is primarily facilitated by the wider diaspora in addition to the clan- and class-crossing networks. According to figures published by the Pew Research Centre in 2016, the Somali diaspora at that time consisted of 490,000 in Kenya, 440,000 in Ethiopia, 250,000 in Yemen, 150,000 in the United States, 110,000 in the United Kingdom, 100,000 in Libya, 70,000 in South Africa, 60,000 in Sweden, 30,000 each in Uganda, the Netherlands and Norway, and 20,000 in Canada. These numbers should, however, be treated with caution, as they were presented as rough estimations; the distribution of Somalis abroad was, and still is, uncertain, chiefly due to confusion between the number of ethnic Somalis and the number of Somalian nationals.

Because some of the countries close to Somalia that have given its refugees temporary respite, such as Yemen and Kenya, are no longer safe, Somali refugees now face secondary, and even tertiary, displacement and need to find other routes to travel by and safer destinations to go target (Moret et al. Reference Moret, Simone and Denise2006). Ever since war began in Yemen in 2015, for example, many of the approximately 250,000 Somalis living there have either had to return to Somalia or migrate further afield. This concerned one of our interlocutors who had been raised in a camp in Kenya and knew no other home than the camp. In 2016, the Kenyan government announced the closure of Dadaab – the world's largest refugee camp, where up to 400,000 Somalis had found shelter, often for years – leaving many Somalis between a rock and a hard place (Besteman Reference Besteman2019b; Human Rights Watch 2016). After that decision, their options were to either return to a hostile home country or to find new safe places.

Recent migration from Somalia has been shaped particularly by an exodus of young people (Majidi Reference Majidi2017), even from relatively peaceful places such as Puntland and Somaliland. It is believed that members of the global Somali diaspora have been incentivising youth emigration (Phillips and Heiduk Reference Phillips, Mingo, van Reisen, Mawere, Stokmans and Gebre-Egziabher2019). Among the many current causes of migration are: unemployment and economic difficulties; an uneven, privatised and under-regulated education system; peer pressure; strong smuggling networks; lack of reliable security; and fragile and weak state institutions that fail to engender hope (Wasuge Reference Wasuge2018).

Somalis have opted to explore transcontinental South-South corridors by making their way to South America, along with migrants from other African nations. Relaxed visa requirements and the lack of deportation agreements have attracted thousands of African migrants (Marcelino and Cerrutti Reference Marcelino and Marcela2011; Vammen Reference Vammen, Kleist and Thorsen2017); from Africa to Brazil, and then to Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala, they try to reach Mexico. Somalis navigate this pathway of more than 40,000 km through word of mouth, social media and payment to smugglers. More often than not, the final stop is the Mexico–United States border, where the United States government has set up its “architecture of repulsion” (Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2019). The chances of Somalis joining their friends, families and other compatriots in the diaspora in the USA have been shrinking, as is evidenced by the restrictions put in place by President Trump's 2017 Executive Order which banned nationals of several countries, including Somalia, from entering the United States.

While there are a few recent studies on Somali movements to South Africa and Latin America (Sadouni Reference Sadouni, Becci, Burchardt and Casanova2013), the Africa-Asia corridor remains widely understudied. Secondary movements proceed through regular means, such as through student visas, for family reunion or for marriage migration, but they also include irregular means, including the services of smugglers to cross international borders (Davy Reference Davy2017). So far, there is scarce information on how Somalis migrate to Indonesia and how they finance those journeys.

A Somali diaspora has been developing in Southeast Asia for about a decade. The Somalis in Indonesia tend to be relatively young (in their 20s and early 30s), consistent with the youth exodus from Somalia currently shaping the country's emigration. In Indonesia, the Somali diaspora consists primarily of asylum seekers and refugees, whereas in Malaysia, one of the few countries to allow Somalis visa-free, short-term entrance, it additionally consists of international students and businesspeople. It is not uncommon for Somalis to switch back and forth between different immigration statuses. For example, some arrive with a scholarship and a student visa then apply for asylum once their studies are complete. Somali businesspeople have also applied for asylum when they have been unable to return to Somalia because of escalating violence there.Footnote 3 In October 2019, there were 1436 Somalis registered with the UNHCR Indonesia office in Jakarta, making them the second largest group of refugees and asylum seekers, comprising 10% of Indonesia's asylum seeker and refugee population, a statistic that falls behind Afghans (56%) and ahead of Iraqis (6%) and Myanmarese (5%). Particularly noteworthy is the relatively high percentage of Somali women (46%), which is far above the approximate 20% of women in other asylum seeker and refugee groups, most of whom travel in family groups as wives or daughters rather than independently. This opens up a number of urgent questions not only about refugee groups’ migration pathways but also about the more general gender/age nexus (Table 1).

Table 1. Somali asylum seekers and refugees registered in Indonesia

Source: unpublished figures supplied by the UNHCR Jakarta.

Unlike in African host countries, Somali refugees in Southeast Asia do not live in camps but in cosmopolitan urban centres, such as Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur, where they are able to live in greater anonymity and can access the informal sector. These megacities are important spaces of refugee governance that require more empirical exploration, not least to understand the local, temporary placement of Somali populations and their coexistence with locals who are also often living in precarious conditions (Hoffstaedter Reference Hoffstaedter, Koizumi and Hoffstaedter2015; Jacobsen Reference Jacobsen2006). In addition, many Somalis registered with UNHCR also live in smaller cities, such as Medan, Makassar and Batam. There, they are most often housed in so-called ‘alternatives to detention’, which, against what the nomenclature suggests, are characterised by spatial barriers, fearful interaction between local and refugee communities, and major hurdles to gaining informal work. High rates of unemployment in Indonesia limit informal work options for Somali asylum seekers and refugees. More importantly, under Indonesian law, refugees are not allowed to engage in paid work. Although these laws are not always enforced, many asylum seekers and refugees caught working illegally have been punished and detained (Palmer and Missbach Reference Palmer and Antje2019; Sampson et al. Reference Sampson, Robyn, Gifford and Savitri2016).

Refugee Governance in Indonesia

Indonesia perceives itself as a non-immigrant nation (Dewansyah and Handayani Reference Dewansyah and Irawati2018). Indonesian policymakers consider it too risky to view refugees in any manner except by humanitarian terms, primarily because sovereignty and domestic security are jealously guarded and considered fundamental (Lee Reference Lee2006). Until now, refugee issues in Southeast Asia have been overshadowed by politicised discourses on securitisation, questions of sovereignty and populist anti-immigrant backlashes (Jati and Sunderland Reference Jati and Emily2017). Southeast Asia has the weakest normative frameworks for refugee protection of any region in the world, apart from the Middle East (Klug Reference Klug2013). Most Southeast Asian states (Cambodia, Timor-Leste and the Philippines are exceptions) have not signed the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees or the related 1967 Protocol. Despite having signed other international conventions, such as the customary non-refoulement principle (Tan Reference Tan2016) and others which should offer basic guarantees for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees, Indonesia remains reluctant to provide formal protection for refugees and has not put a domestic framework for refugee protection in place. While Indonesia seemingly tolerates the temporary presence of refugees, it offers no options for their permanent integration into society (Missbach Reference Missbach2015).

In the past, Indonesia has allowed the temporary residence of refugees, particularly after the exodus of more than a million Indochinese in the late 1970 and 1980s. At that time, Indonesia was part of a regional approach to managing the influx of forced migrants throughout Southeast Asia, providing temporary shelter for refugees before they resettled in third countries such as the United States, Canada and Australia, or repatriated. Despite some criticism, the 1989 Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA), a program designed to deter and to stop the continuing influx of Indochinese refugees to Southeast Asia, is still perceived as a success in regional and international refugee protection (Davies Reference Davies, Abass, Ippolito and Juss2014; Kneebone Reference Kneebone, Abass, Ippolito and Juss2014). This form of international support for refugees in Southeast Asia, however, no longer exists. While Indonesian policymakers tend to perceive Indonesia as place of temporary residence from which recognised refugees would be resettled to third countries after a short period of time, the persistent global resettlement fatigue has now extended the periods of waiting for transiting refugees and has worn out the patience of local policymakers (Brown and Missbach Reference Brown and Antje2016; Moretti Reference Moretti2017). Perceptions of Indonesia as a refugee and asylum seeker hosting country are generally bleak. In a report published by Amnesty International (2016) which was based on 27,000 people in 27 countries, Indonesia ranked second to last, just ahead of Russia, in terms of how willing its citizens were to let refugees live in their towns, neighbourhoods and homes. Moreover, since 2017, UNHCR Indonesia has only processed applications for refugee status determination when there has been a specific and recognized resettlement opportunity or evidence of a sponsorship application to a third country.

One of the countries that previously resettled Somali refugees from Indonesia was Australia. Between 1991 and 2001, several hundred Somalis arrived in Australia under the Refugee and Special Humanitarian Program and the Family Reunion Program. Australia ceased accepting any refugee registered with UNHCR Indonesia from 1 July 2014, including Somalis. For many years, Australia has also been a destination country for asylum seekers arriving by boat (Phillips Reference Phillips2017). Amongst these asylum seekers were Somalis who had transited through Indonesia, sometimes without first registering with UNHCR. In 2013, Australia's militarised border protection and deterrence policies removed this option for irregular onward travel (Chia et al. Reference Chia, McAdam and Purcell2014), thereby extending the length of time refugees stay in Indonesia under precarious conditions. Once Australia was removed from the list of the possibilities, the final nail in Indonesia's coffin and existence as a dead-end street for refugees was placed (Missbach and Palmer Reference Missbach and Wayne2020). Despite the limited prospects for regular or irregular onward migration and a lack of any functioning protection infrastructure, the number of Somalis registering in Indonesia remains constant, which raises the question: What makes countries like Indonesia attractive to Somali asylum seekers?

Although Indonesia offers no official legal pathway for refugees to remain, it tolerates the presence of asylum seekers and refugees, including Somalis. Its porous borders and lax migration control make it easy for asylum seekers to enter the country (Hugo, Tan and Napitupulu Reference Hugo, George, Napitupulu, McAuliffe and Koser2017). Weak border controls and selective enforcement of migration law by local immigration authorities together with strong informal economies and the presence of civil society organisations and religious charities make Indonesia the current second-best option as a temporary host country, particularly first best destinations, such as australis, are no longer in reach. According to many of the interlocuters interviewed for this study, Indonesia's abolition of the mandatory immigration detention of refugees in late 2018, after Australia reduced funding to the international organisation contracted to manage processes in detention, endorsed that perception. Last but not least, Islam, practised by the majority of both Indonesians and Somalis, offers the promise of religious solidarity and is often noted by smugglers, as our interlocutors mentioned.

Rather than developing a state-controlled framework and infrastructure for refugee protection, Indonesia has effectively outsourced its responsibility for refugees to the UNHCR and International Organisation for Migration (IOM) through the 2001 Regional Cooperation Agreement. However, social services and financial support for refugees from the UNHCR, IOM and local NGOs has been limited and unable to substitute for proper state protection. Despite the work prohibition, only 60% of all refugees in Indonesia have been provided with IOM-funded accommodation, leaving many refugees to fend for themselves, consequently subjecting them to homelessness, abuse and discrimination. The lived reality for refugees in Indonesia is now characterised by economic, financial, legal and socio-political precarity (Missbach Reference Missbach2015).

Only a few Somalis in Indonesia appear to receive support from co-ethnics elsewhere in the global diaspora. There are spontaneous but infrequent acts of solidarity towards Somalis from local host communities, local aid and charity organisations, international NGOs, and aid agencies. The general impression we formed during fieldwork was that compared to other refugee communities in Indonesia, Somalis are more vulnerable to homelessness and malnutrition. Somali refugees that we met in 2018 appeared to be in dire situations. For comparison, the majority-Hazara refugee community, members of which have been in Indonesia in greater numbers and for a longer period of time, have established schools and have maintained solid networks with support from philanthropists in Australia and Europe (Brown 2018; Clark Reference Clark2019; Sampson et al. Reference Sampson, Robyn, Gifford and Savitri2016). Some Somali refugees, however, did show us photos of handouts of food they received sporadically from the Catholic Archbishop of Jakarta, something unheard off among other groups. Nonetheless, Somalis seemed to suffer more from xenophobia and racism than other refugees in Indonesia. Whether or not Somalis earn only “hostile charity” (Besteman Reference Besteman and James2019a) from the host society because of political stigmatisation and negative security perceptions or other racial fears requires further investigation.

The exceptional case of a young Somali woman

This brings us to our selected focal account which offers an uplifting view on the situation. Faduma's case stands out from the Somali and other refugees in the community. Despite her relatively young age and her gender, two traits that are often discriminated against, Faduma has earned the respect of the Somali community and other refugees. Her quick rise as a refugee spokesperson and educator has drawn substantial attention from the UNHCR and other organisations who now rely on her translation services. Unlike many refugees who have suffered from being stuck in transit in Indonesia and who have been deeply frustrated by long time spent waiting for resettlement that may or may not materialise, Faduma has embraced the opportunities available to her in Indonesia. In order to do so, she has explored rather unconventional venues outside of the typical realm of religious charity and international aid organisations. While many refugees in Indonesia tend to pin all their hope on a better future life, Faduma has already begun the pursuit of a life worth living in situ.

Coming a long way

The first time we met Faduma in early 2018, she was 24 years old. Faduma had come to Indonesia in early 2017 on her own with neither family nor friends.Footnote 4 The decision to leave Somalia had been hastily made by her and the people she worked as a nanny for, shortly after she had escaped an attempted assault in the streets of Mogadishu. It was a difficult decision; at that point, she had spent almost two decades in Somalia. Faduma lost her biological parents at the age of four and grew up in an orphanage. She was sponsored by donors of the orphanage to complete senior high school and then received some support from them to cover her study fees. In the orphanage, she received a religious upbringing and was close with some of her teachers, two facts that may have instilled in her both a positive outlook and the urge to be of service to others. When she turned eighteen, she had to leave the orphanage and started working as a live-in maid, allowing her to support herself while continuing her education in public health, although she “would have preferred to study medicine”. Faduma received additional public health training through the Red Cross, UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) projects in Somalia, in which she learned about vaccination and diseases over the course of about six months. Unfortunately, she lost all of her certificates of completion when she left Somalia in a rush.

According to Faduma, her employer arranged for a smuggler. Due to a general increase of violence in Somalia but sparked by news of the attempted assault on Faduma, her employer had decided to leave with his family. Rather than having Faduma go back onto the streets and look for new work, he offered her assistance. Despite asking several times, we did not receive a definite answer regarding the price paid for the smuggling services. It is possible that the payment was loaned to her rather than offered a gift. It is also possible that the family did not want her to know their true economic status compared to the wages they had been paying her. The smuggler organised fake documents and a ticket through Dubai to Kuala Lumpur.Footnote 5 When asked about the journey, Faduma, whose world until that point had mainly been the streets of Mogadishu, said that “she sat down when her smuggler told her to, lined up when he told her to, and moved when he told her to”. At certain points during the journey, the smuggler gave her a passport and she stood in line to show it to officials. She said that she was too scared to look at it properly, apart from noting it had a blue cover and her photo inside. Faduma said that everything was so overwhelming at that time that she has difficulty remembering dates and locations.

After travelling with her until their arrival in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the smuggler took the passport and put her in a room in a hotel where “some of the staff spoke Arabic”. The smuggler showed her “where the drinking water was in the corridor and paid the hotel staff to bring her food”. He told her “to wait for his return” to the hotel, but he never came back. Faduma described in great detail how happy she was to be alone behind the locked door of her hotel room on that first day and to be able to sleep in safety. Soon though, the staff told her that her accommodations had been paid for only three nights. The contact phone number the smuggler had given her did not work, and hotel staff said they had no idea “who or where he was”. When she told the hotel staff that she had no more money, they found some Somali female students who took her to their apartmentFootnote 6 where she stayed for three months. The Somali students told Faduma repeatedly that it was “not good in Malaysia for refugees or for single women”, and there were “many refugees already and they were not treated well”. They recommended she go to Indonesia, where “UNHCR would give her a place to stay and food if she had no family”.

By January 2017, the students had raised enough funds to book her a seat on a smuggling boat to Medan in Sumatra, a common destination for refugees (BBC News Indonesia 2014; Jakarta Post Reference Jakarta2017). They even gave her an additional US$100 emergency money for the trip. There were about 20 people that Faduma joined on the boat; among them, she was the only African. The boat arrived in Indonesia during the night and Indonesian immigration authorities appeared not long after, separating the women from the men. Faduma had earlier been instructed by the smuggler who the students had paid to arrange the boat trip to look out for a man with his head covered; this would be Faduma's next contact person. When she saw a man like this gesturing to her, she approached him. He asked her how much money she had and she showed him the US$100, which he took, giving her three 100,000 Rupiah notes (US$22) in return and putting her on a bus that took three days and nights to travel from Sumatra to Jakarta.

On her arrival to Jakarta, which was also at night, another Indonesian man put Faduma in a taxi headed to the UNHCR office, and she waited in the street until it opened. She registered her claim for asylum, as her Somali friends in Kuala Lumpur had recommended. When she asked about a place to stay, UNHCR offered her no support, so she walked out onto the street again and sat on the ground, not knowing what to do. The side entrance to UNHCR's Jakarta office was quite busy with asylum seekers and refugees coming and going, and it was not unusual for people to help others from the same country as them. Fortunately, a young Somali woman passed by and Faduma asked her for help. It turned out that this woman was considered a minor by the UNHCR. Unaccompanied minors were given a monthly stipend of Rp1,250,000 (US$90) – about a third of the minimum wage in Jakarta. As there were no available spots in any of the special shelters for female minors at the time,Footnote 7 the Somali girl had rented a room. She invited Faduma to stay with her.

Soon after their first encounter, her new friend turned eighteen, meaning she lost her monthly support; they were unable to continue to afford the rent. Faduma and her friend were homeless for about a month, sleeping mostly in Jakarta's largest mosque, where they occasionally received donations of small amounts of money and food. Faduma said that the Indonesian women she encountered there were friendly and understanding. As she got to know more Somalis, Faduma was invited to stay with them, but never for long, so she moved houses frequently. With the help of some acquaintances within the Somali community, Faduma and another one of her Somali friends finally managed to get a room in Pasar Minggu, an inner-city suburb of Jakarta known to be a lower socioeconomic area. The two girls lived together for more than a year. At the time of our first interview in May 2018, Faduma had moved in with two Somali friends who received UNHCR stipends because of their medical conditions. Collectively, they were able to pool enough money to rent a one-bedroom apartment for Rp1,200,000 per month (US$90) in Kalibata, another cheap part of Jakarta.

From our observations, couch surfing was common for refugees, as many Somalis faced homelessness. They would often find short-term shelter with other Somalis who could afford a rented room or apartment. Several of the people we interviewed noted that they had experienced homelessness for some portion of their time in Indonesia. “If someone needs food and you have, you share. If you have money from a relative or friend in another country, you help others who have nothing. If someone needs a place to sleep, you give them one”, a Somali woman explained. However, hospitality was not without its limits. For example, for a short time, two other Somali women stayed with Faduma as a last resort until her Indonesian landlady insisted that they leave as she did not want extra people staying there.

Faduma and her friends were proud to be independent, standing on their own feet; they carefully selected the visitors they allowed into their room. Faduma stressed that they allowed no men to visit them, underlining her account of this decision by telling the story of a Somali woman who had fallen into disrepute after she had run out of money and agreed to cook and clean for male Somali refugees who shared a small house. She ended up in a relationship with a man from the house who promised marriage but deserted her when he found out she was pregnant. Again and again, Faduma would emphasise to her roommates how important it was for Somali women to stick together and “not follow men”.

When asked whether she liked living in Indonesia, Faduma was very positive: “Everything is good in Indonesia, there is no daily abuse and no pushing”, jokingly adding that this was because Indonesians were “so skinny and so small”. Faduma credited much of the tolerance to their shared religion (“If you are Muslim, [Indonesians] treat you well”) and to her own demeanour (“If you are a bright person, [Indonesians] will respect you”).Footnote 8 Although she was following the political developments in Somalia and seemed relatively informed about the recent changes in potential resettlement countries, which have further decreased intakes of refugees from Indonesia, Faduma continued to try as much as possible to live in the present in order to deal with the challenges that would materialise “here” and “now”.

Making do

Unlike other asylum seekers, Faduma has received no financial assistance at all from UNHCR or any other NGO; she has had to ‘make do’ on her own and with the help of her friends. As her English began to improve,Footnote 9 she started volunteering at a refugee learning centre and soon became an interpreter for other Somali refugees at their appointments with the UNHCR or other aid organisations. For this, she received a small payment. Despite her youth and social status as an unmarried woman, Faduma was selected by the Somali community to act as their representative in interactions with the UNHCR and its partner organisation in Jakarta. Although she received no payment for this task, it offered the potential to network and gave her access to information.

Through volunteering at events and for organisations, Faduma met a number of foreigners, mostly Australians and Americans, with whom Faduma forged some meaningful connections and functional friendships. Some gave her money while others offered her small jobs and invited her to participate in activities, some of which were refugee-related. When speaking about this in our meetings with her, Faduma was quite straightforward with her expectations. She explained that friendships were not only for friendship's sake but ideally also had to be utilitarian in some way or another. Faduma did not expect benefits only for herself but also particularly for those who supported her (like her housemate who received the UNHCR stipend).

Faduma befriended her Indonesian neighbour who had a catering business. Faduma and her housemates helped this woman prepare food boxes and, in return, received food, even on days when there were no catering orders. Faduma said her neighbour always asked “Sudah makan?” (Indonesian for Have you eaten?) whenever she saw them. Thanks to this initial friendship with her neighbour, Faduma's level of friendship with other female Indonesians in her neighbourhood increased. Her and her housemates were invited to a neighbourhood women's picnic and other outings. Unlike many refugees in Jakarta, Faduma put effort into learning Indonesian, which proved very helpful when interacting with her neighbours and other people from lower-economic strata. Acquiring language skills was an essential element of her success in an otherwise hostile and highly competitive environment like Jakarta.

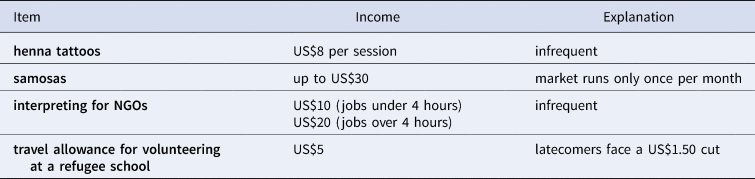

Faduma and her roommates tried several other ways to boost their level of income. For example, they tried cooking and selling samosas at a monthly weekend market organised by a Jakarta environmental organisation. It cost them Rp150,000 (US$12) to buy the ingredients, and they could make up to Rp300,000 (US$25) in profit. They also had skills in creating henna tattoos and sought out Indonesian female customers in Monas or Sarinah, two recreational areas of Jakarta. Faduma said that they had to be “careful and watch out for authorities” while looking for customers because if they were caught working without a permit, they would be taken to immigration detention. To avoid arrest, they did this infrequently, sitting beside pathways and showing images of the henna tattoos on their mobile phones. If someone was interested, they exchanged phone numbers and went to the client's home where they might, for example, decorate women for wedding parties. Over one year, they had about fifteen customers, each of whom paid Rp100,000 (US$8). Faduma explained: “We deliberately keep the price cheap so no one reports us or thinks we ask for too much money – 100,000 is ok, the women have this without asking their husbands. We want to do this more but don't know how and still to stay safe”.Footnote 10

In order to better understand their financial situation, we asked Faduma for a summary of their shared expenses and incomes per month (Tables 2 and 3). Given the unpredictability of their earnings, this was easier said than done. The income they generated each month varied between US$40 and US$150. Faduma summarised the uncertainty and precarity of the everyday struggle: “If we have Rp800,000 (US$60) we can eat twice a day in [a month]. If only Rp400,000 (US$30) with no additional care package, we can only eat once a day and we cannot be picky about what to eat even if it upsets our stomach”.Footnote 11 Moreover, Faduma said that they also were often late with their rent. Their landlord, however, was forgiving as long as some money was coming in. Their room was also in such a poor condition that it was unlikely any other person (apart from another refugee with a similarly precarious income situation) would move in.

Table 2. Regular expenses for each month (as in July 2018)

Table 3. Potential monthly income (as in July 2018)

At the time of our first round of interviews, there were infrequent food donations to Somali, Sudanese and Ethiopian refugee women and children from a Catholic nun, but only in some parts of Jakarta. In addition, the Refugees & Asylum Seekers Information Center (RAIC), a refugee-led organisation established in August 2017,Footnote 12 provided monthly care packages to refugees from all ethnic communities whenever they received enough donations to cover those care packages. Moreover, around Islamic holidays, there were handouts and donations; during Ramadan in 2017, each Somali woman was given five kg of rice, but since many recipients had no kitchen or stove with which to cook the rice, something that was not unusual in cheap Jakarta accommodations, they onsold it to a local food store. Occasionally, an Indonesian Buddhist organisation delivered bags of rice and flour to refugee communities. During the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the private charities no longer continued offering their donations.

From our additional interviews and observations, also verified by Thomson (Reference Thompson2016) in his journal article, other Somali women in the community seemed more entrepreneurial than Faduma. For example, some women cooked Somali dishes and sold them to Somali refugee men. One Somali woman had specialised in baking cookies and even occasionally supplied Indonesian NGO members with them. One of Faduma's friends bought Indonesian fabrics, designed clothes favoured by Somali customers, had them made by a local Indonesian tailor and sold them to other Somali women, allowing payment in instalments. This business idea arose mostly because the Somali women were generally larger than Indonesian women and had trouble buying clothes in Indonesia. This friend was able to support herself from the commission she made. Indonesian batik patterns and fabrics seemed popular with Somali women, many of whom researched prices and quality in Tanah Abang, a traditional market in Central Jakarta known for its many inexpensive fabric stalls. Some had ideas to export fabrics back to Somalia but lacked the reliable business contacts to be able to do so. Others were convinced that if they could work legally in Indonesia, they could very quickly set up businesses to export a variety of Indonesian products to African nations as well as sell them within African business communities in Indonesia. Clothes and plastic goods (crockery, cutlery, and shoes) were singled out as being very cheap in Indonesia; also of interest were general pain medications, mosquito repellents, and cooking oil. Some of the Somali women that we interviewed explained that they were hoping to turn their skills in cooking Arab, Yemeni and Somali sweet and savoury dishes into paid work but were afraid of being caught by the Indonesian immigration authorities and lacked sufficient funds to finance a start-up. Last but not least, throughout our fieldwork, we encountered rumours about Somali women engaging in sex work. A photo essay published in The Guardian on Somali women in Jakarta and survival sex (Bunch Reference Bunch2018) caused friction in the Somali community as men accused women of being prostitutes, triggering malicious gossip and even physical violence towards unmarried Somali women in public.Footnote 13

When we spoke with Faduma in early 2020 and inquired about the grocery delivery plans she had shared with us earlier in 2019, she replied that it had not yet taken off.Footnote 14 Rather than opt for more typical entrepreneurial activities in diaspora, Faduma had become interested in acquiring different skills. First and foremost, she was interested in developing her people skills and extending her socio-professional networks. She discovered that she liked to organise events, connect people and initiate new self-help activities. What caught our attention in the interviews was that Faduma often stressed her wish to “give something back” to the Somali refugee community. When talking about her motivations to help refugees, she sometimes sounded almost like a volunteer from the Global North. She had started to embrace a kind of new-age jargon (empowerment, resilience, mindfulness) often driven by spiritual concepts of well-being, which she possibly picked up through the many workshops she had attended as part of her volunteer work and also through her interactions with Indonesian and foreign refugee advocates.

Skill trainings and the making of a new self: from refugee to volunteer

In late 2017, UNHCR Indonesia informed registered refugees and asylum seekers that chances for resettlement to third countries were dropping significantly (Bemma Reference Bemma2018). After a period of depression throughout the refugee community as the new reality sank in, asylum seekers and refugees started to set up more initiatives, refugee schools, learning centres and women's groups. From early in her stay in Indonesia, Faduma worked hard to learn and further improve her English, which proved to be an indispensable tool for accessing international aid and charity groups in Jakarta and making contacts with visiting volunteers. As soon as she gained enough confidence in her English language skills, she volunteered to teach at a new NGO which had been set up by refugees for refugees called the Health, Education and Learning Program (HELP).Footnote 15 Later, she volunteered once more to teach at a local shelter for unaccompanied female minors. She also agreed to be the Somali community contact for the refugee-led group RAIC.Footnote 16 In that capacity, she helped fellow Somalis. For example, she would accompany them to doctor's appointments or interpret in their meetings with UNHCR case officers. Faduma said this was not an easy task because the traumatic stories of others took an emotional toll on her and bought back her own past traumatic experiences. Also, the Somali people that she translated for sometimes got angry when they did not receive the services and support that they had hoped for.Footnote 17

Throughout our conversations and interactions with Faduma, we noted her awareness of opportunities and her ability to find ways to participate in activities that upgraded her skills and extended her access to networks and information. Rather than focusing only on typical refugee infrastructures and aid providers, Faduma was also open to alternative philanthropical groups and venues, and as she was becoming more known as a committed and intelligent volunteer, Faduma was being invited to more upskilling events. For example, after foreign supporters negotiated a reduced fee for five members of the refugee community and found donors to cover that reduced fee, Faduma was able and invited to participate in a three-day seminar hosted by international social enterprise United Edge promoting a justice-based approach to development. This seminar was well-attended by Indonesian staff members from many large international NGOs with offices in Indonesia. Faduma was also invited to attend a first aid course taught by Indonesian doctors, organised by the refugee-led Jakarta Refugee Network, where she received a much-wanted certificate. From the Roshan Learning Center, another community-driven refugee school,Footnote 18 Faduma received training in child protection; from the Cairo Community Interpreter Project (CCIP) she received five days of intensive formal interpreter training; and through RAIC, she attended a two-day course on mental health. The networks Faduma was able to access and the contacts she had made were very impressive and, in turn, strengthened her confidence.

Rather than assisting only specific individuals, such as her Somali housemates and other Somali women, Faduma was helping a vast number of people; she was becoming a multiplicator and facilitator and had the ability to reach out to many of her fellow community members at the same time. An opportunity to do so materialised when she agreed to become an activities coordinator for a refugee women's organisation which allowed her to test a number of ideas she had thought would be useful for refugees.Footnote 19 For example, Faduma was planning “positivity sessions” for refugee community members, particularly for female unaccompanied minors. To advance this program, Faduma asked a foreign friend with funding experience to help her create funding proposals. Faduma's new organisation offered art, craft, upskilling and self-help classes to refugee women. In collaboration with Indonesian organisations, it created a space and gathered a number of volunteers in order to coordinate free medical and dental check-ups for women and children from Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Afghanistan and Yemen. Separately, Faduma has also initiated a foodbank, supported by an Indonesian friend with good contacts, where hotels would donate leftovers from big wedding parties, delivering it to Faduma's house. She crafted a fast distribution system to account for the fact that many refugees did not have refrigerators. The food packages were picked up from Faduma's house by a number of women who then returned to their immediate neighbourhood and distributed them further, before the food could go bad.

Despite the initial positive outcomes and high levels of appreciation from refugees, budget constraints and a lack of volunteer assistance caused the women's organisation to limit the number of participants it delivered to and activities it hosted and supported. They had to subsidise transport allowances to participants who would not otherwise have been able to attend (Wardhani Reference Wardhani2019). Having forged collaborations with local universities, refugee-led initiatives, businesspeople and artist circles, Faduma's organisation hosted public meetings which were used to address common needs and wants. In early 2020, it was still going strong, and Faduma has often been invited to share her knowledge about refugee women's empowerment. The COVID-19 pandemic has again created difficulties, as many women do not have good access to the internet.

Considering all of these developments, it is remarkable how quickly Faduma evolved from her arrival to Indonesia in early 2017, homeless, with no money and knowing only a few words of English, into an active coordinator, interpreter and community representative with a large network of contacts. Faduma is an extraordinary person with special skills and talents, as evidenced by her ability to learn English quickly, who has managed to efficiently adapt to her new life in Indonesia, overcoming the challenges faced by African refugee women who often have to stand out in public and deal with frequent discrimination and outright racism. Moreover, she was able to make use of Jakarta's philanthropic environment by forging on-off, or sometimes also more enduring, alliances with expatriates, Indonesian socialites, students and local businesspeople who would support her causes either financially or by other means.

Living in Jakarta, a large and booming city, and able to legally move about within it, if not outside of it, Faduma has obtained considerable freedom and mobility to make her own decisions about her life, to gain more skills and to prepare for her future while also supporting others in the refugee community. In Jakarta, she has been able to utilise unique opportunities that would not have been possible for her had she remained in Mogadishu. Although refugees in Indonesia officially face many legal restrictions, including the lack of a right to work, the inability of the state to enforce those prohibitions on refugees living more or less autonomously in the community has resulted in the unintended toleration of many refugee activities. Despite the risk of arrest and punishment by Indonesian immigration authorities for some of her earlier activities, the strategic alliances Faduma and other community leaders have formed with Indonesian universities, entrepreneurs, lawyers and NGOs provides her with a level of basic understanding and sympathy, and possibly safeguarding. In the short term, it is unlikely that this kind of refugee activism will be transformative beyond the immediate benefactors; it likely will not lead to a more formal refugee protection regime in Indonesia. Quite the opposite may be the case: the Indonesian state may further retreat from refugee matters. This would, in turn, make Indonesia more attractive as a deviant destination for refugees and asylum seekers on the move.

Conclusion

Any attempt to explain the unprecedented arrival of thousands of Somalis in Indonesia must take into account both the increasingly restrictive migration and asylum policies the Global North has implemented and also the socio-legal conditions for refugees that prevail in so-called transit countries, increasingly referred to as alternative destination countries. Given that externalised migration and border policies reach far beyond the countries of the Global North that instigated them (Besteman Reference Besteman2019b), it is not surprising that Somalis look for new opportunities. Egypt and Libya, for example, once gateways to Europe for Somalis, have become dead-end streets (Pascucci Reference Pascucci2016). Meanwhile, new migration corridors via South and Central America and Southeast Asia are being explored. Somalis who wish to leave their country of birth must bypass closed routes and discover new ones. The need to reroute migratory journeys and search for alternative safe destinations are direct consequences of the restrictive admission and deterrence policies of the Global North.

Even though almost 7000 kilometres separate Mogadishu and Jakarta, Indonesia has become a destination for a number of Somalis. For many years, Indonesia was deemed a transit country from which it was easy to move on and resettle to third countries. Although the promise of fast resettlement is no longer substantiated, in large part because of the decreased resettlement quotas in Australia and other countries of the Global North, certain social, political, economic, legal and cultural conditions in Indonesia have possibly made it more attractive than other host countries. One key factor of Indonesia's allure is the de facto, unintentional and informal system of refugee protection. Indonesia's regulations relating to the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers are rather ambiguous and, additionally, the state lacks the capacity to fully enforce those regulations. Indonesia is unable to deport rejected asylum seekers and is unwilling to support recognised refugees or allow official integration into local populations, leaving asylum seekers and refugees in a challenging situation. Within the racialized hierarchy of refugee deservingness, Somalis generally tend to occupy the lowest ranks when it comes to receiving leniency and the highest when it comes to facing punitive reactions by state officials. The same relatively weak state control and limited capacity to police refugees gives the Somali community space to create their own networks and engage in income-generating activities despite lacking the right to work. Large cosmopolitan cities like Jakarta offer advantages for refugees, such as access to the informal sector, Indonesian aid and philanthropic organisations, and international networks. Engaging with organisations and actors beyond the classical aid sector has strengthened community resilience and added a degree of informal refugee protection, somewhat impacted by local and international media reimagining Somali refugees as ‘pitiable people’, which seems to have encouraged charitable acts and public sympathy. Although such informal protection is no solution for the increasing number of refugees around the globe, it helps explain the formation of new migration pathways along South-South corridors, far from the usual tracks towards the Global North. Informal protection also redefines deviant destinations as more attractive temporary places of respite where Somali refugees can engage in temporary place-making while also planning the next stage of their journey.

In order to explore the links between social mobility, experienced only by very few, and the widespread and multifaceted precarity suffered by most refugees in Indonesia, we have selected the outstanding case of a young Somali woman, Faduma. What drew our attention to her was that unlike other Somali refugee women in Jakarta, Faduma, despite her relatively young age, was much more concerned with instigating and coordinating local activities that benefited Somali and other refugees rather than “just” improving her own lot.

As the ethnographic material from our interaction with Faduma has shown, refugees in the Somali community need to operate in less public or online spaces and to keep a low profile when it comes to money-making activities and community organising. While Faduma, like other refugees from Somalia, had hoped for a short transit in Indonesia, she now accepts that she may be there for a long time and wants to make best use of that time by acquiring new skills and contacts. Affected by previous trauma and having to navigate the daily risks of life in a large and crowded city as a stranger who tends to stand out, Faduma is forced to ‘make do’ in order to sustain herself. Without wanting to romanticise or glorify her own resilience in dealing with the ever-present precarity of her situation, Faduma acknowledged that “Being hopeful in my situation is very difficult, but I am grateful that I am still alive and breathing here in Indonesia, because at least no one is shooting at me.” While nothing has changed in regard to her legal precarity – she is still a refugee who cannot enjoy the same basic rights as Indonesian citizens – for now, Faduma has managed to decrease her economic, financial and socio-political precarity through both the networks she has become a part of and the personal alliances that she has forged. While none of these temporary remedies might last, for the time being, Faduma has made her transit into a better place to be. Nonetheless, she sees most of these activities also as preparation for a better future elsewhere.

This article has attempted to marry micro- and macro-levels of analysis as a path to better understanding both the ways geopolitical circumstances have an impact on refugee journeys and the ways individuals choose to adapt to or reshape circumstances to their own advantage. They do this in a number of ways: carving out an economic niche, working around legal constraints, building strategic local networks and taking calculated risks. Considering individual practices within the context of larger movements allows us to recognise the potential benefits arising from adaption, creativity and resilience. While our account is fragmentary, with pieces of the mosaic missing or unable to be accurately captured, this article has shown that Faduma's resilience and her capacity to adjust and thrive have been of extraordinary benefit not only to herself but to many others in the refugee community and, in fact, beyond. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Faduma and her allies distributed basic food supplies to refugees and their Indonesian neighbours who were out of work and income, which has earned them respect from both communities. From this point of view, Faduma was achieving much more than just ‘making do’.