Introducing Suvaṇṇabhūmi: A Sri Lankan Contribution

Suvarṇabhūmi (Sanskrit [Skt]) or Suvaṇṇabhūmi (Pali [P]) may be rendered in English as ‘Golden Earth’, ‘Golden Land’, or ‘Land of Gold’. This fabled Indian name partially corresponds to the western myth of ‘El Dorado’ in European traditions: a far off, mysterious place associated with great wealth and prosperity, that does not necessarily consist of gold. The Arthaśāstra, for instance, refers to aloe-wood (II, 11.59) and to kāleyaka, a kind of precious incense (II, 11.69), that came from Suvarṇabhūmi (Olivelle Reference Olivelle2013: 124–125; Ray Reference Ray1994: 87). Although references to this ‘Golden Land’ appear frequently in various ancient and classical South Asian texts, none can prove that it was a real place or provide precise information about its location. Some Jātakas, such as the Mahājanakajātaka or the Supāragajātaka, describe maritime ventures to a legendary Suvarṇabhūmi, but the vessels were always driven off by severe weather and hence the textual sources are not very explicit about the ultimate destination (Ray Reference Ray1994: 22; Ray and Mishra Reference Ray and Mishra2018) [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Supāragajātaka (?). Stucco (7th–9th c. AD); Phra Pathom Chedi National Museum, Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand

Given these accounts, the term ‘Suvarṇabhūmi’ was perhaps first coined by ancient Indian traders and was probably intended to refer to large parts of coastal Southeast Asia stretching from lower Myanmar (hereafter, Burma), central Thailand (Siam), the Mekong Delta, and the Malay Peninsula (Skilling Reference Skilling1992: 131; Wheatley Reference Wheatley1961; see also Addendum) to as far afield as Sumatra (Van der Meulen Reference Van der Meulen1974: 1, 4). Indeed, a ninth century inscription from Nālandā in India refers to Sumatra as ‘Suvarṇadvīpa’, or ‘Golden Island’ (Shastri Reference Shastri1924: 325). Later, the so-called Amoghapāśa inscription found at Padang Roco, west Sumatra, and dated 1208 śaka (=1286 AD), mentions Sumatra as ‘Suvarṇabhūmi’, and as a counterpart of ‘Bhūmijāva’, that is Java (Slamet Reference Slamet1981: 223).Footnote 2

Currently, most scholars think that this generic toponym was used as a vague designation for an extensive region, located to the east of the Indian subcontinent. Sylvain Lévi, for instance, assumed that the term Suvarṇabhūmi should be treated as a directional designation—in this case ‘eastern’—rather than a regional one (Lévi Reference Lévi1925: 29). Furthermore, the standard phrase “they set sail in the ocean…going to Suvaṇṇabhūmi” (P, nāvāya mahāsamuddaṃ pakkhandati […] suvaṇṇabhūmiṃ gacchati) as found in the Mahāniddesa (Nidd I 155), for example, clearly indicates that the place should be reached by sea. In any case, over the centuries, different parts of Southeast Asia came to be designated by the additional epithets of the ‘Golden Island, Peninsula, or City’,Footnote 3 presumably seeking to link their realms with this celebrated term known from literary sources.

However, from the perspective of Buddhist devotees throughout the Theravāda world, Suvaṇṇabhūmi is more than simply a name or a mere land of riches and abundance. It is also a concept to which I shall now turn. Indeed, some Pali sources specifically link the name with a pivotal story that narrates the spread of Buddhism into various ‘countries’ or polities, one of which was called Suvaṇṇabhūmi. The most important Pali sources are the Sinhalese chronicles such as the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa (fourth and fifth century AD, respectively)Footnote 4 which state that two elder monks, Soṇa and Uttara, were sent to Suvaṇṇabhūmi for ‘missionary activities’ in the time of King Asoka (third century BC).Footnote 5 That these chronicles and their commentaries exerted at some point a tremendous influence in Buddhist Southeast Asia largely explains why these various polities later sought to identify themselves with one of the aforementioned ‘countries’ such as Suvaṇṇabhūmi. Indeed, without the importance of these Sri Lankan traditions in Southeast Asia, it could be argued that the various legends related to Suvaṇṇabhūmi or other Asokan missions would never have been born. While much modern scholarship has been preoccupied with attempting to identify the precise location of Suvaṇṇabhūmi, its identification has also been motivated in part by “the national pride of claiming to be the first Buddhist state in Southeast Asia”, as Prapod Assavavirulhakarn has observed (Reference Prapod2010: 55). Therefore, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the search for the real Suvaṇṇabhūmi became the focus of intellectual history in both Europe and Southeast Asia (Ray and Mishra Reference Ray and Mishra2018). It also became the centre of great controversy, especially in Burma and Thailand, in which each country claimed to be the Buddhist ‘Golden Land’ (pronounced Suwannaphum in Thai, and Thuwannabhumi in Burmese). Over the years, various authors have attempted to identify the centre of Suvaṇṇabhūmi as either in the Mon country of Rāmaññadesa (lower Burma) or in the Dvāravatī region (central Thailand). As expected, this myth has largely shaped the vision and historical interpretation of generations of archaeologists, historians, and art historians, especially those in these two Buddhist countries. With such nationalist agendas, it is hardly surprising that the scholarly quest to identify Suvaṇṇabhūmi has been both controversial and muddled (Cherry Thein Reference Cherry2012; Mazard Reference Mazard2010).

However, one must ask two critical questions: what hard archaeological evidence is there to substantiate such views and what do we really know about the early advent of Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia? Perhaps what is more important to understand is how and why diverse kingdoms in Southeast Asia adopted, and at times adapted, the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi from the Sinhalese chronicles. One might further ask how far back the tradition actually dates, who the key figures were behind its popularity, and what purposes did the legends really serve. In this article, I will briefly re-examine past scholarship that is mostly western, Thai, and Burmese, and compare the literary evidence with the earliest epigraphic and archaeological data, distinguishing material discoveries from legendary accounts.

Buddhist Legends and Historical ‘Truth’

In the composition of Buddhist stories, chronicles, and inscriptions from the second millennium AD through present-day Thailand and Burma, it became common to attribute the introduction of Buddhism in various localities to the first journeys of the ‘Asokan missionaries’.Footnote 6 It is important to note from the start, however, that there is no evidence that this idea was present during the entire first millennium AD in Burma or Thailand. There is also no confirmation from this early period that the Mahāvaṃsa or related chronicles were already known in Southeast Asia and that people in the coastal regions of pre-modern Thailand or Burma had yet identified themselves with one of the Asokan missions.Footnote 7 As I shall illustrate later, it was probably only from the fifteenth century onwards that lower Burma and northern Thailand adapted parts of the myth contained in the Sinhalese chronicles. However, we must interrogate whether these various accounts have any historicity.

Despite what has been firmly asserted by some (Chand Chirayu Rajani Reference Chand1968: 13–26), doubts can be seriously cast that a ‘historical’ Soṇa and Uttara, or any other missionaries were sent to anywhere in Southeast Asia in the third century BC: in any case, they left no trace. It is true that in nineteenth century India when the British archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham ‘excavated’ ancient stūpas in and around Sāñcī, in Madhya Pradesh, he discovered a few inscribed reliquaries. These contained the name of Moggaliputtatissa, ‘architect’ of the Asokan missions, and names of a few other monks whose designations and titles seemed to correspond to the ‘missionaries’ that were sent out to the Himalaya region (Himavanta) according to the Sinhalese chronicles.Footnote 8 After making this discovery, Sir Alexander Cunningham thus triumphantly proclaimed:

The narrative of these missions is one of the most curious and interesting passages in the ancient history of India. It is preserved entire in both the sacred books of the Sinhalese, the Dipawanso and Mahāwanso; and the mission of Mahendra to Ceylon is recorded in the sacred books of the Burmese. But the authenticity of the narrative has been most fully and satisfactorily established by the discovery of the relics of some of these missionaries, with the names of the countries to which they were deputed. (Reference Cunningham1854: 119)

This exulting and self-assured discourse of a previous age has since been tempered by Jonathan Walters who argues that:

These epigraphs [are not] proof that Asoka did in fact send out ‘missionaries’ in every direction, nor that his chief Patriarch was indeed Moggaliputtatissa, nor that the ‘missionaries’ to the Himalaya really were Majjhima, Dundhubhissara, and Kassapagotta. Instead, what these epigraphs prove is that during the second half of the second century, BC, some Śunga Buddhists honored these particular Buddhist saints within some narrative of the Asoka legend as a central focus in their pious program at Sāñchi. (Reference Walters1992: 298)

Returning to Soṇa and Uttara, it is notable that no material proof has yet been unveiled either in or out of India which would corroborate the existence of the two elders or theras travelling to the ‘Golden Land’. Moreover, before the second millennium AD, no Southeast Asian epigraphic sources seem to refer to this Buddhist legend, or to the Pali name of Suvaṇṇabhūmi at all.Footnote 9 In the total absence of such epigraphic evidence or archaeological vestiges dating back to the remote time of King Asoka, what ‘silent arguments’ would remain for Thai and Burmese historians alike? Additionally, one may ask how should the Sinhalese chronicles be treated in this regard?

Regardless of the usual additions and interpolations which often accompany such stories, let us now read between the lines, and reconsider the Buddhist legendary conversion of Suvaṇṇabhūmi as told in the twelfth chapter of the Mahāvaṃsa. The ‘Great Chronicle’ abounds with precise and dated information, albeit narrated in a very lyrical manner:

When the thera, Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion [Buddhism] of the Conqueror [Asoka], had brought the (third) council to an end [c. 250 BC] and when, looking into the future, he had beheld the founding of the religion in adjacent countries, (then) in the month of Kattika [October] he sent forth theras, one here and one there…Together with the thera Uttara, the thera Soṇa of wondrous might went to Suvaṇṇabhūmi…[where they] pronounced in the assembly the Brahmajāla (suttanta). Many were the people who came unto the (three) refuges and the precepts of duty; sixty thousand were converted to the true faith. Three thousand five hundred sons of noble families received the pabbajjā [‘minor ordination'] and one thousand five hundred daughters of noble families received it likewise. Thenceforth, when a prince was born in the royal palace, the kings gave to such the name Soṇuttara. (trans. Geiger Reference Geiger1912: 82–87)

The great Buddhologist Étienne Lamotte, however, strongly criticised the Sri Lankan tradition by adding that:

The chronicle simplifies and misrepresents the facts by situating general conversion of India in the year 236 after the Nirvāṇa [c. 250 BC]; it shows its partiality by attributing the merit to Moggaliputtatissa and his delegates alone. This tendentious version was never accepted on the mainland, nor even generally admitted by all the Sinhalese religious. (Reference Lamotte1988 [1958]: 297)Footnote 10

Lamotte is not the only scholar to doubt the historicity of the Asokan missions as portrayed in the Sinhalese chronicles. Others before him noted that no mention was ever made of a ‘Suvaṇṇabhūmi mission’ in the inscriptions or edicts of King Asoka.Footnote 11 Moreover, the tradition of the two theras, namely Soṇa and Uttara, has remained unknown in other northern Indian Buddhist schools. Clearly, however,this argument ex silentio should not eclipse the ‘preaching vocation’ of the Buddhist religion (sāsana), which claims universality. Intrinsically, of course, nothing is opposed to this tradition which could be described as ‘centrifugal’ or ‘diffusionist’.

In this vein, Lamotte also reported that:

For the mainlanders [i.e. Indians], the conversion of India was the result of a long and patient teaching process inaugurated by the Buddha and continued during the early centuries by the Masters of the Law and their immediate disciples. (Reference Lamotte1988 [1958]: 297–298)

Thus, as François Lagirarde recalled it:

One [other] well-established legend makes Gavampati the first [Buddhist] missionary to continental Southeast Asia, two centuries before them [Soṇa and Uttara], at the time of the Buddha himself. (Reference Lagirarde2001: I, 44, my translation)

Lagirarde continues citing the Mahākarmavibhaṅga, a Sanskrit text which recalls that Gavampati, a direct disciple of the Buddha, is said to have converted people in the ‘Golden Land’. This text was certainly known in central Java in the eighth and ninth centuries AD since it was illustrated on the low-reliefs of the Borobudur's ‘hidden base’. Harry Shorto, assuming that the text was also known in the Mon country, speculated that it could have been an inspiration for the production of a later local legend (Reference Shorto and Sarkar1970: 25–26). However, Lagirarde (Reference Lagirarde2001: I, 44) doubts that the ‘historical’ Gavampati could be the same person as the legendary character.

In any case, both the Thai and the Burmese traditions often went even further by claiming that Buddhism was first introduced to their land by the Buddha himself, stating that he often flew to the area, left a footprint and made prophecies of the future expansion of the religion (sāsana) [Figure 2]. This belief is revealed in a number of religious chronicles, inscriptions, and footprints spread throughout the entire region from at least the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD onwards.Footnote 12 The literary tradition of lower Burma is also very rich with other local stories and legends attached to not only the ‘centrifugal’ myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi, but also to the ‘centripetal’ traditions which emphasise what John Strong calls “the deepness, the repetition, the autochthony, and the archaeology” (Strong Reference Strong1998: 96, my translation).

Figure 2. The Buddha forecasts the Birth of Pegu. Modern mural painting; Pegu, lower Burma

The best example presented by Strong is to the core fifteenth century legend of the Shwedagon in Yangon which reports that under the resplendent dome are enshrined a few hairs of Gotama Buddha, purportedly brought back from India by two ‘Mon brothers’, the merchants Tapussa and Bhallika [Figures 3–4]. On this point, Strong suggests that the Shwedagon legend is indeed regarded as ‘centripetal’, since all the later post-fifteenth century versions highlight the importance of determining, locating, and excavating the precise place where the hair relics must be enshrined together with relics left in Yangon by three previous Buddhas in this aeon (kappa). This connection with the past Buddhas reinforces the notion of ‘deepness’ attributed to the place, rather than dissemination. Unlike Asoka, who redistributes the relics of the Buddha in various places, Strong argues that in Yangon it is unthinkable to have someone carry out the division or the displacement of the hair relics. The site must remain “inviolable” (Strong Reference Strong1998: 95).Footnote 13

Figure 3. The Shwedagon pagoda. Yangon, Burma

Figure 4. The gift of eight hairs to Tapussa and Bhallika. Modern mural painting; Shwedagon, Yangon, Burma

The comparison with the site of Phra Pathom Chedi in Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand, is intriguing. Similarly, it is supposed to enshrine relics of the Buddha, although this remains uncertain because the inner core has been sealed for centuries. The present round-shaped Chedi, evoking Sri Lankan style and built in the 1860s onwards, has encased an older monument which, in turn and according to tradition, is believed to have enclosed another monument originally resembling the stūpa at Sāñcī, India [Figures 5–6].Footnote 14 Therefore, the two sites, Phra Pathom Chedi and Shwedagon, dispute primacy today, not only regarding their size and prestige in the Buddhist world, but also as the most sacred place where true ‘relics’Footnote 15 of the Buddha were allegedly first introduced in Southeast Asia. However, as we shall discover later, although the Shwedagon has fifteenth century inscriptional evidence supporting the myth of Soṇa and Uttara, there are no such early inscriptions for Nakhon Pathom that seem to refer to this legend, except for some mid-nineteenth century musings by Thai religious and royal figures, reflecting a measure of the continuing influence of the Sri Lankan tradition most likely based on the Mahāvaṃsa. As a matter of fact, in Nakhon Pathom it was only with the reign of King Mongkut, an ex-monk and Buddhist scholar in his own right, crowned as Rama IV (r. 1851–1868), that Asokan missions were suddenly afforded prominence and were associated with the site (see infra). Relatedly, it must also be remembered that the actual name of the city, ‘Nakhon Pathom’, is a modern designation which became official only with King Rama VI (r. 1910–1925). It derives from nagarapaṭhama in Pali, which means the ‘first city’; the most ancient and prominent city in Thailand.

Figure 5. Phra Pathom Chedi enclosing an older monument. Early 20th century mural painting; Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand

Figure 6. The Phra Pathom Chedi encasing an older Sāñcī-like stūpa? Modern mural painting (completed in 2009); Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand

In any event, the above stories and various legends of uncertain age, relating to the conversion of Suvaṇṇabhūmi, either by Gavampati in the time of the Buddha or by Soṇa and Uttara under the reign of Asoka, clearly seem to be the source for later local traditions and folklore. For example, the residents of Bilin, a hill-site located a few kilometres north of Thaton, lower Burma, spread the belief that Soṇa and Uttara had died there, but this is probably an eighteenth or nineteenth century legend, recorded by Taw Sein Ko (Reference Taw1892a). Certainly, there is no factual basis for this, but it readily shows how these two arahants have recently been ‘Burmanised’Footnote 16 [Figures 7–8]. Conversely, another modern tradition in central Thailand suggests that the relics of Soṇa thera are kept in a certain Wat Si Mahathat in Lava, presumably Lopburi (Thammathatto and Pho Na Pramuanmark Reference Thammathatto and Pramuanmark1989: 101; see infra, n. 21).

Figure 7. Statue of Uttara in parinibbāna. Hilltop-site near Bilin, Thaton region, lower Burma (Courtesy: Donald Stadtner)

Figure 8. Statue of Soṇa in parinibbāna. Hilltop-site near Bilin, Thaton region, lower Burma (Courtesy: Donald Stadtner)

In consideration of these aforementioned traditions, which should not necessarily be perceived as contradictory,Footnote 17 one might wonder whether it is plausible to see in these vague and mostly anonymous remnants of several historical missions the purposes of converting Southeast Asia to Buddhism. As Prapod Assavavirulhakarn has remarked, quoting from Richard Gombrich: “to establish Buddhism is to establish the Sangha, which cannot be accomplished overnight” (Reference Prapod2010: 63). Prapod goes on to state:

It is more accurate to look at the introduction of Buddhism into Southeast Asia as a gradual process that involved many factors and dynamics. This does not mean that missions played no part in the spread of Buddhism into the region; on the contrary, they played a crucial role because only through them did Buddhism become firmly established. (Reference Prapod2010: 63)

Nonetheless, if there is some ‘truth’ to the missionary accounts of Soṇa and Uttara, Prapod ironically enquires whether the two theras “were well versed in the local language” or if “the local people were well versed in Pāli” (Reference Prapod2010: 63). Of course, this is quite unlikely. He also notes the obvious fact that the Brahmajālasutta, the first sermon reported to have been preached in Suvaṇṇabhūmi, is a highly theoretical and rather difficult text. It is not exactly suitable for beginners or new converts to the sāsana. Finally, the author also raises serious concerns about the feasibility of establishing Buddhism in a foreign land with only two members of the Sangha. Specifically, not only would a minimum of five ‘fully ordained’ monks be required to ordain (upasampadā) new ones, but also a ‘consecrated space’ demarcated by sīmās or ‘boundary markers’ would have had to be defined (Reference Prapod2010: 60–61).

Given these requirements, it is not surprising that later Pali commentaries and recensions, as recorded for instance in the ‘Extended Mahāvaṃsa’,Footnote 18 specify that in fact each Asokan mission consisted of a leader and four other associates in order to form a minimum chapter of five monks.Footnote 19 Modern Mon-Burmese chronicles even provide the names of the three additional missionary monks travelling together with Soṇa and Uttara, namely “Aniruddha, Tissakutta and Somarasa who arrived in Sudhammavatī [Thaton]” (Tun Aung Chain Reference Tun2010: 13).Footnote 20 Conversely, a recent Thai chronicle or tamnan composed in the twentieth century assigns them different names of “Phra Chaniya, Phra Phuriya and Phra Muniya” (Thammathatto and Pho Na Pramuanmark Reference Thammathatto and Pramuanmark1989: 55, 69).Footnote 21 Since then, this myth of the introduction of Buddhism in the ‘Golden Land’ by the five monks has powerfully captured the popular imaginationFootnote 22 and artistic creation. Some modern Thai mural paintings, for instance in Phra Pathom Chedi or Wat Rai Khing, in Nakhon Pathom Province, represent the legend very nicely. In one of the murals, which likely recalls an episode from this ‘Extended Mahāvaṃsa’ (Malalasekera Reference Malalasekera1988 [1937]: 119–120), the group of five monks is thus portrayed converting the sea ogress after their arrival in Suvaṇṇabhūmi [Figures 9–10].

Figure 9. The sea ogress and the five missionary monks in Suvaṇṇabhūmi. Modern mural painting (completed in 2009); Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand

Figure 10. Nakhon Pathom is Suvaṇṇabhūmi. Modern mural painting; Wat Rai King, Nakhon Chaisi, central Thailand

Time and Space: The Advent of Buddhism in Mainland Southeast Asia Based on Archaeological Data

As we shall now discover, epigraphic and archaeological evidence does not actually support the above legendary accounts of the introduction of Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia. The earliest archaeological data that supports a firm presence of Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia dates back only to the middle of the first millennium AD, many centuries after the alleged Asokan mission was sent to Suvaṇṇabhūmi.

It appears from these data that massive Buddhist conversions cannot realistically be placed prior to the fifth century AD in mainland Southeast Asia. However, it is true that some of the oldest Indic-related artefacts found mainly in peninsular Thailand to date are now estimated to date back to the first centuries of the Common Era or even earlier, with the introduction of iron working, glass, and semiprecious stone ornaments (Glover and Bellina Reference Glover, Bellina and Manguin2011; Glover and Jahan Reference Glover, Jahan, Revire and Murphy2014; Ray Reference Ray1994). While these artefacts can be perceived as evidence of early contacts with South Asia or even considered import products, they cannot yet serve as proof of early Buddhist conversions or establishments in the peninsula. I therefore strongly object to a statement made recently that all this early material found or excavated in Thailand is “the sign of the arrival of Buddhism in Suvannabhumi 2000 years ago” (Boonyarit Chaisuwan Reference Chaisuwan and Manguin2011: 89).

For example, it has often been argued by scholars that the tiny crouching lion (or tiger) objects carved from carnelian recovered over the years from protohistorical sites in Burma, peninsular and central Thailand, Vietnam, and as far as China, indicate early Indian Buddhist presence in those lands since these ‘carnelian lions’ were believed to be the representation of the Buddha as śākyasiṁha, that is, the ‘lion of the Śākya clan’ (Ray and Mishra Reference Ray and Mishra2018: 6). However, as Robert Brown (Reference Brown, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017: 47) acknowledges, the Buddha was never represented as a lion, and the lion never was used as an ‘aniconic symbol’ in Indian Buddhist art. Moreover, Bob Hudson (Reference Hudson2004: 84) proposed earlier in his doctoral dissertation that these ‘carnelian lions’ may in fact relate to ‘tally tigers’ that were military officers’ symbols used during the Qin dynasty in ancient China. It is quite likely that these objects have absolutely nothing to do with the use of Buddhist ideas and values.

Among other early artefacts often cited is an ivory comb representing the eight auspicious symbols (aṣṭamaṅgala) and found in the area of Chansen, central Thailand (Gosling Reference Gosling2004: 37). Previously, Piriya Krairiksh (Reference Piriya1977: 53) dated the object from the fifth century AD on stylistic grounds but radiocarbon tests appear to confirm an earlier dating to the third or early fourth century AD (Bronson Reference Bronson, Smith and Watson1979: 330–331; Woodward Reference Woodward2003: 34–35; fig. 8). Regardless, this ivory comb cannot specifically be linked to Buddhism. However, what is more intriguing is a fragment relief in terracotta that was found in U-Thong and stylistically dated to the third or early fourth century by Hiram Woodward (Reference Woodward2003: 37) or the fourth or fifth century AD by Jean Boisselier (Reference Boisselier1965: 144–145, fig. 16). This relief shows three standing monks going on alms round (piṇḍapāta) and may qualify as the oldest material indication uncovered to date in Thailand and the whole of Southeast Asia of such a Buddhist practice; it was already confirmed in the seventh-century travel record of the Chinese pilgrim Yijing 義淨 (Li Reference Li2000: 12; Revire Reference Revire, Revire and Murphy2014: 243, fig. 1) [Figure 11]. Another stucco fragment from U-Thong of a meditating Buddha under the nāga, also lacking archaeological context, is dated as early as the second to third century AD by some (Gosling Reference Gosling2004: 45–47) or the fourth to fifth century AD by others (FAD 2007: 34), but, as a matter of fact, both these terracotta and stucco fragments may well date from a later period in the late first millennium AD.

Figure 11. Monks on alms round. Terracotta (6th–7th c. AD?); U-Thong National Museum, central Thailand

Most of these pieces are generally described by scholars as reminiscent of the purported Amarāvatī style from the Andhra region in southern India. This common and biased assertion naturally brings to the fore the idea that all important early Indic influences came to mainland Southeast Asia from southern India and via seafaring monks and maritime traders, to which the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi is greatly indebted.Footnote 23 These individuals or guilds of merchants arrived presumably first and foremost in peninsular Thailand, the Gulf of Martaban, or the Gulf of Thailand, as well as in the Mekong Delta.Footnote 24 Regarding the Gulf of Thailand, it has been repeatedly argued by Thai scholars since the early 1980s that during the so-called ‘Dvāravatī period’ (sixth to eleventh centuries AD), the paleo-shoreline was much higher (c. 3 to 4 metres) than the present mean sea level. This fact would allegedly confer the Dvāravatī moated settlements, now set back from the coast, an ideal location in the maritime trade at the time (Phongsri Wanasin and Thiva Supachanya Reference Phongsri and Supachanya1980). However, more recent geological studies have undermined this theory and lowered the maximum transgression limit to the Holocene period, roughly 8500 years ago and followed by a continuous regression. Accordingly, the Gulf of Thailand paleo-shoreline during the first millennium AD would have been much closer to the present sea level than previously thought (Sin Sinsakul Reference Sin2000; Trongjai Hutangkura Reference Trongjai, Revire and Murphy2014).

While the seafaring coastal routes were quite important over the centuries for the spread of new ideas and the introduction of Buddhism as well as Brahmanism in mainland Southeast Asia, they certainly were no more so than were interior lines of communication. As we shall discover below, in the first millennium AD there were also multiple large urban settlements in the Burmese and Thai interiors which may have been in early contact with Buddhism. It would therefore seem that the more information that is generated from locations in these interior areas, the more we can also establish early land connections with South Asia and beyond.Footnote 25

It is indeed well known from inscriptions that Pali-based Buddhism was present in Śrīkṣetra, upper Burma by the fifth or sixth century AD (Stargardt Reference Stargardt2000) and slightly later in Dvāravatī, central Thailand (Revire Reference Revire, Revire and Murphy2014; Skilling Reference Skilling1997a). Peter Skilling (Reference Skilling1997b: 132) also observes that the oldest Pali inscriptions, despite a general assumption, are not found in Sri Lanka, as one might expect but rather in Śrīkṣetra and Dvāravatī in the Pyu and Mon territories. Among the early inscriptions from mainland Southeast Asia, the ‘ye dharmā formula’ appears prominently not only in Pali, but also in Prakrit and Sanskrit (Kyaw Minn Htin Reference Kyaw and Manguin2011; Ray Reference Ray2002 [1946]: 33–34, 42, 69–70; Revire Reference Revire, Revire and Murphy2014: 256–259, table 4; Skilling Reference Skilling2003–2004) [Figure 12]. Therefore, the ‘formula’ cannot serve as evidence for the presence of one Buddhist school (nikāya) or another. More ye dharmā inscriptions are found in Cambodia and Vietnam. The one found on the back of a standing Buddha image from Tuol Preah Theat, Kompong Speu Province, is often presented as the oldest Pali inscription (seventh to eighth centuries AD) from Cambodia (Baptiste and Zéphir Reference Baptiste and Zéphir2008: 27–28; Hazra Reference Hazra1982: 74). However, upon a closer examination it appears to actually be a related Prakrit recension, slightly Sanskritised (Skilling Reference Skilling2002: 162, 171, Reference Skilling2003–2004: 284). Another ‘Pre-Angkorian’ epigraph of a ye dharmā formula, far less recognised and only recently discovered in Angkor Borei, is in Pali (Skilling Reference Skilling2002: 159–167). It thus relegates the inscriptions K. 501 and K. 754 (dated 1074 and 1308 AD, respectively) to positions as the second and third oldest Pali epigraphs found thus far in Cambodia (Cœdès Reference Cœdès1951: 85–88, Reference Cœdès1989).

Figure 12. Ye dharmā formula. Golden plate (7th–8th c. AD); provenance unknown, Musée Guimet, Paris

If we turn to Chinese annals, sources from the third century AD mention a ‘Buddhist kingdom’ by the name of Linyang 林杨, which has been tentatively identified by some as the ancient Pyu ‘kingdom’ of Beikthano, upper Burma. The same Chinese sources referred to another ‘kingdom’ by the name of Jinlin 金邻 (‘golden wall’), located on a large bay, which a few scholars have attempted to identify as the Mon kingdom of Thaton in lower Burma (Moore Reference Moore2004: 6–7), while others proposed that it was instead the area around the Gulf of Thailand (e.g. Wheatley Reference Wheatley1961: 116ff). According to a later source, the Liang Shu 梁書 or the official history of the Liang dynasty (502–556 AD), compiled in the seventh century AD, Buddhism also flourished in Funan 扶南, which was partly located in pre-modern Cambodia (fifth to sixth centuries AD), under the royal patronage of Kauṇḍinya Jayavarman (r. 478–514 AD) and Rudravarman (r. 514–539 AD). A hair relic of the Buddha was said to be in Funan at the time and Buddha images were sent from there to China, as well as monks to help translate the scriptures (Pelliot Reference Pelliot1903: 284–285, 294). The Tang Chinese traveller Yijing also described the Buddhist practices in the countries of the ‘southern seas’ or Kunlun 崑崙 and wrote that Buddhism was flourishing there since early times (Li Reference Li2000: 12–13).

In contrast to these early Chinese textual accounts of the presence of Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia, the archaeological evidence remains rare. If we utilised the example of the boundary markers or sīmās, important as they are for the spread of the community of monks through the rite of ‘ordination’, the majority date only to the eighth to ninth centuries AD, where they are found in stone mainly on the Khorat Plateau, northeast Thailand, and parts of southern and central Laos. Other boundary stones are also found in Thaton, lower Burma, but date even later to the eleventh century AD (Murphy Reference Murphy, Revire and Murphy2014). This, naturally, does not preclude the fact that in ancient times there were several modes of marking the boundary markers, with some of them quite temporary, such as the sprinkling of water on the ground or a ‘water boundary’. This may likely explain why, in ancient Indian and Sri Lankan Buddhist sites, almost no boundary stones around the structures are found, with discovery limited to only a few pillar forms.Footnote 26

In sum and based on this meagre historical and scanty archaeological evidence, it seems that Buddhist practices were gradually introduced in various regions of mainland Southeast Asia from at least, conservatively, the fifth century AD onwards. However, it is not yet possible to determine exactly which region(s) ‘first’ received those diverse Buddhist missions and precisely where the latter originated from. Much also remains to be learnt about the agents and proper modes or channels for this complex introduction of Buddhism(s), not necessarily reflecting the sole Theravāda lineage from Sri Lanka.Footnote 27 Moreover, it must be remembered that the latter monastic lineage was not the exclusive privilege of the ‘orthodox’ Mahāvihāra branch before the twelfth century reform and ‘purification’ of the Sinhalese Saṅgha by King Parākkamabāhu I (r. 1153–1184 AD).Footnote 28

A ‘Mon’ and ‘Buddhist Kingdom’

One striking observation will emerge from the following discussion: a considerable number of the stories and chronicles have often referred to the Mon people and their country as ‘Buddhist’ since the earliest times. The most important piece of evidence for this connection comes from the Kalyāṇī inscriptions (c. 1476–1480 AD) erected by the Mon King Dhammazedi (r. 1472–1492 AD) in Pegu, lower Burma. On the obverse face of the first stone, it is clearly stated in Pali that:

soṇatheraṃ pana uttaratherañ ca suvaṇṇabhūmiraṭṭhasaṅkhātarāmaññadese sāsanaṃ paṭṭhitḥāpetum pesesi. (Taw Sein Ko Reference Taw1892b: 2)

He [Moggaliputtatissa] despatched the elder Soṇa and the elder Uttara to establish the Sāsana in the kingdom of Suvaṇṇabhūmi, in Rāmaññadesa so-called. (my translation)

Other undated Mon inscriptions of King Dhammazedi, currently kept at the Shwedagon, Yangon [Figure 13], also refer to the Buddhist Mon heritage of Soṇa and Uttara:

Figure 13. Shwedagon inscriptions, Pāli, Mon, and Burmese, of King Dhammazedi. Shwedagon compound (c. late 15th c.); Yangon, Burma

With a break in the tradition of those knowing that the sacred hairs of the Lord Buddha were enshrined in the Shwedagon, men no longer worshipped there, and the pagoda became overgrown with trees and shrubs. Two hundred and thirty-six years after the Parinibbana [Final Release] of the Lord Buddha [308 BC], the monks Sona and Uttara arrived in Suvannabhumi-Thaton to propagate the Religion. When the Religion was established and an order of monks set up, King Srimasoka[Footnote 29] requested the two Elders thus: “O Venerable Monks, we have received the Dhamma [Law] and the Sangha [Order]. Can you not provide us with the Buddha to worship?” The two Elders then showed the King the Shwedagon in which the sacred hairs of the Lord Buddha were enshrined. King Srimasoka cleared the overgrowth and built a pagoda and an enclosing pavilion with a tiered pyramidal roof. From that time onwards, the people of the Mon country went to worship there. (Tun Aung Chain and Thein Hlaing Reference Tun and Hlaing1996: 3)

This evidence suggests that the Dhammazedi inscriptions deal mainly with the reform undertaken to ‘purify’ Buddhism in his kingdom. However, we know the tendentious nature of these ‘royal inscriptions’ in the context of a Sinhalese reform of Theravāda Buddhism. It is therefore difficult to offer them more credibility than afforded the chronicles of the same tradition to which I referred earlier.

I now define more precisely what I call the ‘Mon country’, so seemingly related to the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi. Is it only about the Mons of lower Burma or does it also take into consideration the Mons of the lower Chao Phraya valley who left many vestiges in first millennium Thailand?

In the early 1970s, Emmanuel Guillon was of the following opinion:

The knowledge of the history of the Mon civilisation before the tenth century still butts against a singular discontinuity. In Thailand, the Mons left an abundant sculpture; but historical traditions concerning them…refer mainly to the Mon of lower Burma, which would have been the true cultural centre of ancient Mons. (Reference Guillon1974: 273, my translation)

The same author continues:

As yet, precisely in lower Burma, there seems to be an extreme poverty of archaeological vestiges, sculpture, and even epigraphy. (Reference Guillon1974: 273, my translation)

However, recent excavations and archaeological surveys in lower Burma provide new insight on these old assertions regarding the lack of vestiges in the ancient Mon country, even though to date there have been no absolute dates or old Mon inscriptions discovered from the first millennium AD (Moore Reference Moore2013; Moore and San Win Reference Moore and Win2007).Footnote 30 Nevertheless, much work still remains to be done regarding the disastrous ravages of time and climate—with a particularly vigorous monsoon regime in this area—as well as years of civil war, a lack of infrastructure, and difficult access to these regions.

In the mid-twentieth century, French archaeologist Pierre Dupont also noted the discrepancy between a rich oral and recent written tradition, with almost no ancient archaeological remains for the Mons of lower Burma as well as an abundant ancient Mon archaeology, with no textual sources, in the Chao Phraya valley, central Thailand (Reference Dupont1959: I, 11–13).Footnote 31 The exception in this regard would be the Cāmadevīvaṃsa, a fifteenth century Pali chronicle possibly written after an older Mon text. It evokes the Mon settlement of Haripuñjaya (today Lamphun, northern Thailand) coming from Lopburi (Cœdès Reference Cœdès1925: 141–171). However, this apparent absence of written religious sources composed in Southeast Asia during the first millennium AD should not lead us to hastily conclude that they never existed. Evoking the phenomenon of ‘intertextuality’ and the mobility of the texts, Skilling (Reference Skilling2007: 104) compels one to wonder whether, among the vast corpus of the “Siamese Pāli literature” still preserved today in monastic libraries, certain works might not have come down directly or indirectly from older accounts as far back as the ‘Dvāravatī period’.

While continuing to wonder about this apparent incompatibility between the literary and archaeological data relating to the two areas inhabited by the Mons, George Cœdès interpreted the situation to the advantage of the ‘Mons of Dvāravatī’, whom he called Buddhists, in these terms:

The rich Mon archaeology whose vestiges were discovered in Thailand corresponds obviously to a time when the kingdom of Dvāravatī knew a certain prosperity and saw Theravāda Buddhism flourishing. If at the same time, the country of Rāmañña in the Burmese delta does not present anything comparable, it is apparently because Hinduism was most prevalent there. (Reference Cœdès and Shin1966: 116, my translation)

The reader can easily grasp the magnitude of the problem of making this kind of assertion in connection with the Mons of lower Burma. Indeed, how can a country, said to be the ‘spiritual inheritor’ of Soṇa and Uttara, fail to present more archaeological vestiges? Moreover, the earliest archaeological evidence in lower Burma has long been identified as mostly Brahmanical, not Buddhist.

Cœdès further added:

It is a remarkable fact that almost all the vestiges left in the Menam Valley [Chao Phraya valley] by the Mons of Dvāravatī—monuments, statues, inscriptions—are Buddhist. The position of Buddhism in Dvāravatī was so strong that, even throughout the Khmer occupation in Lopburi and in the Menam Valley, it preserved a very clear preponderance over the Hindu religions that prevailed in Cambodia. (Reference Cœdès and Shin1966: 115, my translation)

He then concluded:

The Mons [of Haripuñjaya] are perhaps also responsible for the advent of Theravāda Buddhism in lower Burma in the eleventh century. (Reference Cœdès and Shin1966: 115, my translation)

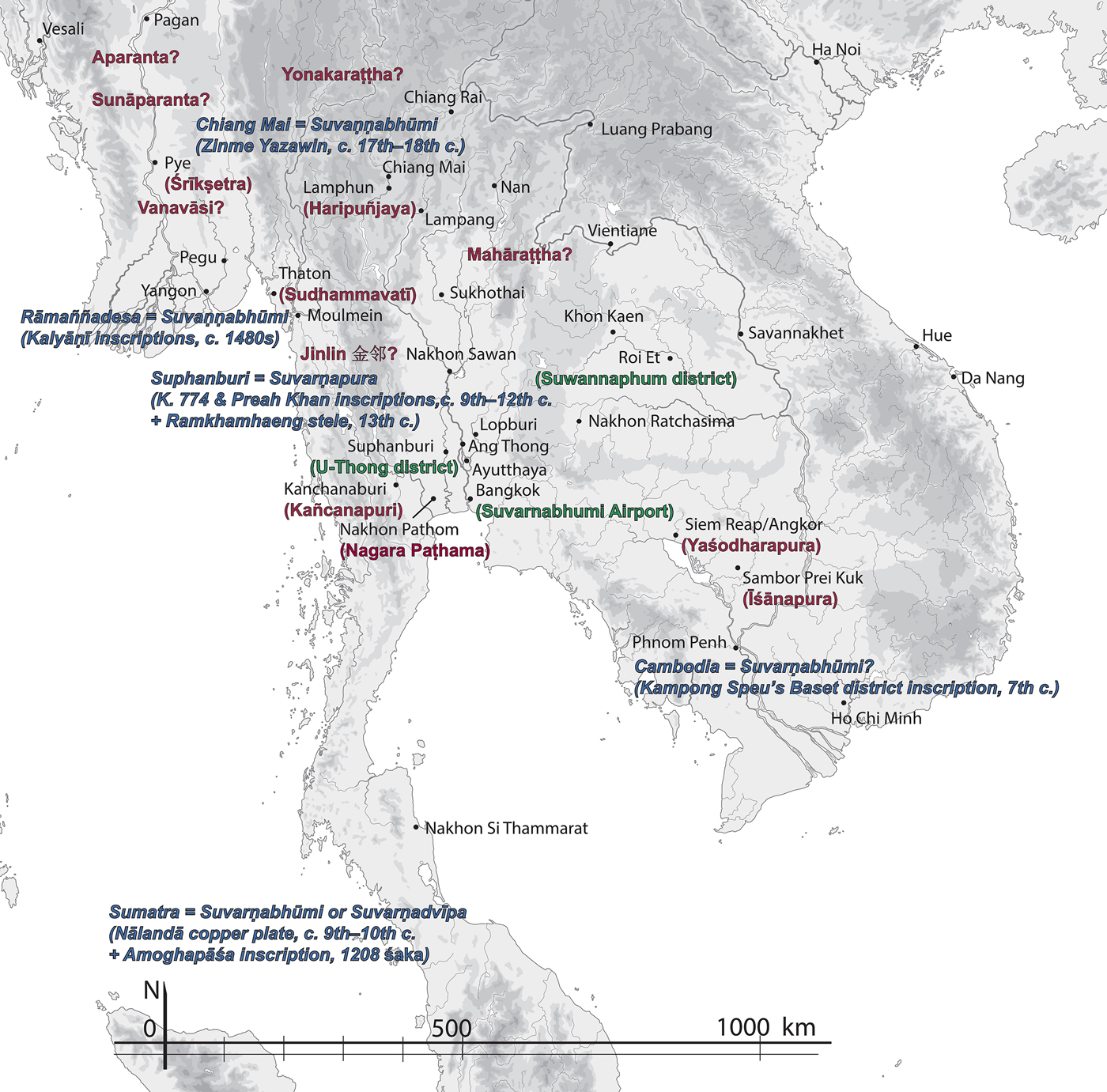

With Cœdès' claim of a solid Mon and Buddhist identity apparently supported by archaeological evidence in Thailand, one did not have to wait long to see these remarks amalgamated by some Thai elite with the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi.Footnote 32 As we shall discover below, it is clearly a nineteenth to twentieth century phenomenon to attempt to delineate bordered entities to ancient texts. Consequently, from this period onwards the fabled land would be commonly located by the Thais in the Mon-Thai country, specifically in central Thailand. A part of the basic argument is that several ancient sites in the central region contain the word ‘gold’ in their toponym such as Ang Thong, ‘the gold basin’, Kanchanaburi (Skt, Kañcanapuri), Suphanburi (Skt, Suvarṇapurī), and U-Thong, ‘the cradle of gold’. While there is even a modern district called ‘Suwannaphum’ (P, Suvaṇṇabhūmi) in Roi Et Province, northeast Thailand, once again this is only a recent designation [MAP 1].

MAP 1. How many golden lands? Ancient and modern toponyms in mainland Southeast Asia

However, older Thai records may echo the idea of a ‘Golden Land’, if not a ‘Golden Age’. The first epigraphic mention in Thailand of a name that can be interpreted as ‘Suvarṇapuri’ is indeed found on the so-called stele of King Ramkhamhaeng, said to have been composed during his reign in the late thirteenth century AD. The fourth face, lines 20–21, reads ‘Suphannaphum’ generally identified with the modern town of Suphanburi (Cœdès Reference Cœdès1965: 7)Footnote 33 [Figure 14a–b]. After considering this, one might legitimately ask whether there were people at the time who believed they lived in a fabled ‘Golden Land’. Additionally, if the answer is positive, one might ask at what point did they accept this notion as true. This occurrence would indeed predate by nearly two centuries the epigraphic reference found in the Kalyāṇī inscriptions of Burma, although this immediate context does not equate that land with the Buddhist mission of Asoka, as professed in the Mahāvaṃsa. In fact, a variant of the name equally occurs somewhat before in the Angkorian inscriptions of Jayavarman VII (twelfth century AD). For example, the Preah Khan inscription refers to ‘Suvarṇapura’, again usually equated with modern Suphanburi in Thailand, but as a ‘dependency’ of Yaśodharapura [Angkor], the great capital of the Khmer empire which had control over most of central Thailand at that time (Cœdès Reference Cœdès1941: 296, n. 2).Footnote 34

Figure 14a. Inscription of King Ramkhamhaeng; Face 4, line 20, reads “Suphannaphu…” (Fig. 14b, close-up); found in Sukhothai (allegedly late 13th c.), National Museum Bangkok, Thailand

However, given this background, one must also be aware of the controversy that surrounds the genuineness of the Ramkhamhaeng stele, especially the fourth face. The future King Mongkut was reported to have discovered in Sukhothai the famous stele but the circumstances and authenticity of it have been questioned by several scholars (Terwiel Reference Terwiel and Grabowsky2011). Among its most virulent detractors, Piriya Krairiksh (Reference Piriya and Chamberlain1991: 126, 131) sees a clever ‘machination’ of Prince Mongkut, newly crowned as King Rama IV in 1851, to serve his political, nationalist, commercial, and religious interests. He also notes that the word ‘Suphannaphum’ does not appear in any other inscription of Sukhothai. Moreover, he believes that the presumed author of the stele, King Mongkut, was well acquainted with either the Pali or Thai Mahāvaṃsa Footnote 35 or other similar Siamese chronicles that were in vogue at the beginning of the nineteenth century, such as the Phongsawadan Krung Syam, which seems to refer to ‘Suphannaphum’ a certain number of times.

Revisiting the Myth with King Mongkut

It was King Mongkut or Rama IV who ‘scientifically’ revived the debate in Thailand regarding the introduction of Buddhism and related it to the founding myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi. This took place at the time of his ‘rediscovery’ and restoration of the ancient Phra Pathom Chedi in Nakhon Pathom during the mid-nineteenth century.

Jean Boisselier has well described this moment as follows:

The King [Mongkut] saw in the stūpa [Phra Pathom Chedi] the witness, built at the time of Asoka, of the arrival in Southeast Asia of the first two missionaries [Soṇa and Uttara] sent there to spread the Doctrine. (Reference Boisselier1970: 57, my translation)

Interestingly, an inscription left by King Mongkut in 1856, still in situ, claims that the site was founded to enshrine the relics of the Buddha sent at the time of King Asoka (Cœdès Reference Cœdès1961: 1; Suchit Wongthet Reference Suchit2002: 3). It appears that King Mongkut only knew of the Asokan missions to the extent that he was familiar with the Mahāvaṃsa—or different recensions of the Mahāvaṃsa—which similarly devotes a full chapter to “The Arrival of the Relics” in Sri Lanka (trans. Geiger Reference Geiger1912: 116–121). Indeed, while in the monkhood before his ascension to the throne, Prince Mongkut had cultivated strong linkages with Sinhalese monks throughout these formative years (Vella Reference Vella1957: 40–41).

Boisselier continues:

We should not forget that, at the time, one was unaware of the history of Southeast Asia, that in India hardly anything was better known and that a work such as the Mahāvaṃsa, which presumably reported on these facts, was one of the rare chronicles of historical nature which one was able, for the time being, to access. (Reference Boisselier1970: 57, my translation)

In any case, Mongkut's conviction and his apparently incipient approach were not without nationalistic interest. Indeed, one can clearly perceive deep religious motivations mingled with scientific concerns behind the restoration campaign of the site, initiated by the king. It was important for the king to assert the religious identity of the ‘Siamese’, in response to Westerners who started to physically and culturally settle in Siam or its neighbouring countries (Damrong Rajanubhab Reference Damrong Rajanubhab1926; Hennequin Reference Hennequin2007; Vella Reference Vella1957). With the growing ‘threat’ of western acculturation, the restoration campaign of Phra Pathom Chedi created an opportunity to return to Siam's ‘Buddhist roots’. Evidently, the Thai royalty had no choice but to join such a pious work.

I thus concur with Boisselier when he writes:

The rebuilding of the Phra Pathom Chedi…follows…the traditions relating to the religious work of Buddhist monarchs…The rebuilding probably tended to show, in a brilliant way, the power of a monarch and his excellent rights to the throne of Siam. (Reference Boisselier1978: 6, my translation)

He then concludes:

It seems possible to advance the proposition that the work at Phra Pathom Chedi…represents as a whole, in the mid-nineteenth century, the last religious foundation supporting the notion that the new sovereign has the capacities of an authentic universal monarch. (Reference Boisselier1978: 6, my translation)

On consideration of this, Thai historian Winai Pongsripian comments:

King Mongkut regarded himself as the reincarnation of King Lithai of Sukhothai…and wanted to be the pillar of the religion. For King Mongkut, the discovery and the restoration of Phra Pathom Chedi constituted one of the major events of his reign. (Reference Winai2000: 155, my translation)

Later, restoration work and research in Thai historical matters were perpetuated by one of King Mongkut's sons. Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (1865–1943), also known as the ‘Father of Thai history’, continued the effort of his father with the same nationalistic and religious zeal:

The Mons [of Burma] allege that the land of Suvarṇabhūmi, in which the monks Sōṇa and Uttara established the Buddhist faith, is identical with the district of Thatôn on the Gulf of Martaban. But I think that we Siamese, with better reason than the Mons, may place it in our own country. For we have a district called U Thong (source or repository of gold) which corresponds to the old name of Suvarṇabhūmi (land of gold); if the latter name was derived from the presence of gold, it is significant that in Pegu there are no gold mines, although such exist in Siam. (Damrong Rajanubhab Reference Damrong Rajanubhab1919: 10; my emphasis)

This is what Prince Damrong wrote in connection with the introduction of Buddhism in Siam or Thailand:

That Buddhism was first established in Siam when Nagara Paṭhama [Nakhon Pathom] was the capital may be deduced from the archaeological remains found at the Paṭhamacetiya [Phra Pathom Chedi] there. These include the stone Wheels of the Doctrine of the sort made in India for worship before images of the Buddha that came into existence, and the religious inscription in Pali…All these show that the Buddhism which was first established in Siam was of the Theravāda school, not unlike that which was propagated in various countries by command of the Emperor Asoka. We may conclude that Buddhism was introduced into Siam before 500 B.E. [i.e. “Buddhist Era”Footnote 36] and has flourished here ever since. (Damrong Rajanubhab Reference Damrong Rajanubhab1962 [1926]: 1)Footnote 37

Attempting to reconcile the rich archaeological vestiges found in Nakhon Pathom with local Burmese lore, Prince Damrong (Reference Damrong Rajanubhab1919: 31) outrightly presumed to suggest associating the ancient capital of Thaton, said to have been sacked by King Anoratha in 1057 AD, with Nakhon Pathom.Footnote 38 This attempt by Prince Damrong to assimilate Thaton, with its strong local connection related to the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi, and bring it into the Thai realm did not actually solve the problem: instead his attempt infused it with a background of religious and nationalistic biases. However, it appears that the reference of both King Mongkut and Prince Damrong to the reign of Asoka was primarily based on the authority of the Sinhalese chronicles, including the Mahāvaṃsa, or, even perhaps an adapted Pali version such as the ‘Extended Mahāvaṃsa’, or the Vaṃsamālinī composed during the reign of King Rama I (Skilling Reference Skilling2007: 106).

How Many Golden Lands?

As we have discovered, even if the reality of an Asokan Buddhist mission to Suvaṇṇabhūmi cannot be proven, its authenticity has never really been questioned among traditional and popular circles in Southeast Asia, particularly in Burma and Thailand. While it may not be possible to determine exactly where the original fabled ‘Golden Land’ really was, the question I have pursued in this article instead is how and when these various regions decided to adopt the myth. Indeed, there are also other provocative issues regarding why the ‘name’ Suvaṇṇabhūmi—a fanciful term found in early Buddhist literature—and the ‘concept’ of the introduction of Buddhism in this land needed to be invented. It seems equally important to acknowledge all the various later traditions that remain of this myth in Southeast Asia.

On the one hand, the Mon-Burmese, basing their arguments mainly on later chronicles (e.g. Bode Reference Bode1897: 10–11; Tun Aung Chain Reference Tun2010) and strong local and oral traditions, generally locate it in lower Burma. It seems fair to say from the Kalyāṇī inscriptions that the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi there actually dates to at least about the middle of the second millennium AD. In Thailand, on the other hand, the possible earlier reference to ‘Suphannaphum’ from the Ramkhamhaeng stele (possibly thirteenth century AD) is somewhat difficult to interpret. However, in most of the oldest northern Thai manuscripts or chronicles from the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries AD, references are also made to a ‘Mueang’ or ‘Nagara Suvaṇṇabhūmi’ as presumably located in the southern vicinity of modern Lamphun or Lampang (e.g. Cœdès Reference Cœdès1925: 79, n. 4, 100, n. 2; Notton Reference Notton1930: 68). Moreover, in these northern chronicles (tamnan or phongsawadan) the entire region around Chiang Mai was commonly identified with ‘the country of the Yonok’ or Yonakaraṭṭha (e.g. Cœdès Reference Cœdès1925: 1, 30, 87, n. 2, 91, n. 2; Prachakitchakonrachak Reference Prachakitchakonrachak1973 [1907]). This ‘northern and foreign territory’ was also one of the nine missions of King Asoka led by the monk Mahārakkhita and is equally valued in the Mahāvaṃsa (trans. Geiger Reference Geiger1912: 82, 85).Footnote 39 A few eighteenth to nineteenth century Burmese chronicles (e.g. Tun Aung Chain Reference Tun2003: 41, n. 1, 43, 44, 46), however, seem to contradict this identification of Chiang Mai with Yonakaraṭṭha and now equate it with Suvaṇṇabhūmi.Footnote 40 The city of Chiang Mai, today in northern Thailand, has long been the capital of the independent Kingdom of Lanna, but was at times under Burmese rule and jurisdiction and was not completely integrated to the Kingdom of Siam or Thailand until 1939.

This latter identification is most remarkable because even among the Burmese, at some point there was some apparent disagreement about whether the heart of Suvaṇṇabhūmi was really in Chiang Mai, Thaton, or elsewhere in the region.Footnote 41 However, perhaps it was not so much about distinguishing two ‘Golden Lands’ in these two locations. Given the historical context of Burmese expansionism in the late eighteenth century AD, it was more likely a way to expand the same and unique Suvaṇṇabhūmi, that is, a ‘Greater Suvaṇṇabhūmi’ from lower Burma to northern Thailand, previously recognised as the ‘Yonok country’ so as to form the ‘geo-body’ of the new ‘Burmese nation’.Footnote 42 In any case, following King Mongkut and Prince Damrong's convictions, many educated Thais now tend to place the heart of Suvaṇṇabhūmi in the western part of the Chao Phraya valley, in the area around Nakhon Pathom and U-Thong.Footnote 43 As I hope to have successfully demonstrated above, it was indeed Rama IV and his followers who re-enacted the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi in modern Thailand and henceforth connected it with the central region.

In reality, there were many localities in Burma and Thailand since at least the second half of the second millennium AD, that were deliberately given the name of a Buddhist region, and with each claiming association a posteriori with the Asokan missions mentioned in the Sinhalese chronicles. From these fifteenth to sixteenth century traditions, a worldview of Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia has seemed to emerge which spread across lower Burma, the Shan states, northern Thailand, Laos, and as far as Yunnan and Cambodia. According to this ‘mental map’, the names of ancient Indian principalities were often simply transposed to many Southeast Asian localities [MAP 1]. The entire region was probably also divided into zones based on the Mahāvaṃsa and the list of the nine ‘countries’ to which missions were sent at the time of Asoka. Such an example is found in nineteenth century Burma in the Sāsanavaṃsa where, of these nine ‘countries’, five are actually placed in mainland Southeast Asia, namely Aparanta, Mahāraṭṭha, Suvaṇṇabhūmi, Vanavāsi and Yonakaraṭṭha (Bode Reference Bode1897: 4–9).Footnote 44

Despite this great diversity accounting for several ‘Buddhist missions’ in various Southeast Asian places, the general view today in popular circles is still overwhelmingly in favour of a ‘unique’ mission to a ‘single’ piece of land in pre-modern Southeast Asia, that of Suvaṇṇabhūmi. This is clearly the result of some nineteenth–twentieth century considerations emanating from the modern nation-states of Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand (Siam). However, in the ‘golden age’ of the new Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) where there is theoretically no more barriers and borders, should we not give more credence to the old hypothesis that the original ‘Golden Land’—assuming that it really existed— included a large area of Southeast Asia rather than just a small portion or a ‘country’ in the sense of a ‘nation-state’? More specifically, all the regions of contemporary Thailand, Burma, and even Cambodia could have been originally located within the margins of Suvarṇabhūmi as a new discovered Pre-Angkorian inscription perhaps suggests (see Addendum). This wise and cautious line of reasoning would thus have the advantage of reconciling the two Thai and Burmese Mon countries and the history of their shared ancestry with the Khmers, despite modern political boundaries.

Finally, we have also seen that the myth of Suvaṇṇabhūmi has had a long and important lineage which certainly reflects the great prestige of the Mahāvaṃsa and the Sinhalese Buddhist influence abroad. By at least the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries AD, Sri Lankan traditions exerted a tremendous influence in Burma and Thailand and the myth is surely tied to this historical trend. From that time, each important Buddhist region subsequently sought to claim a connection with King Asoka.Footnote 45 Significantly, by connecting themselves to one of the nine Asokan missions, the Buddhist nations of Southeast Asia also claimed a link with the Mahāvaṃsa and, de facto, the unbroken tradition of the Mahāvihāra.Footnote 46 It is only later, by the nineteenth and twentieth centuries AD, that the issue became more politicised among the elite and scholars who championed different theories to promote nationalist and religious agendas.Footnote 47 As I have demonstrated, even the royal family in Thailand joined in the debate by linking the antiquities of their kingdom to Suvaṇṇabhūmi and the alleged early presence of a pristine ‘Theravāda Buddhism’ that never existed as such.Footnote 48 The recent naming in 2006 of the brand new ‘Suvarnabhumi International Airport’ by the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand (Rama IX, r. 1946–2016) would thus appear to be only a recent manifestation, or modern appropriation, of this centuries-old myth.

Addendum

Since I completed this manuscript, an important and unique epigraphic discovery was made in Cambodia that some may perceive as pertinent to the issues raised in the article. I assert, however, that it does not affect the article's main points. In December 2017, Dr Vong Sotheara (Royal University of Phnom Penh) discovered a Pre-Angkorian stone inscription in the Province of Kampong Speu, Baset District, which he tentatively dated to 633 AD. According to him, the inscription would shed light on the location of the fabled realm and “prove that Suvarṇabhūmi was the Khmer Empire” (Rinith Taing Reference Rinith2018). To my knowledge, this would be the earliest occurrence of ‘Suvarṇabhūmi’ in South and Southeast Asian epigraphy known to date, since no other inscriptions mentioning this name have yet been found in Southeast Asia before the second millennium AD (see supra). Despite this, the significance of this discovery is difficult to assess from the little information so far published in The Phnom Penh Post (Rinith Taing Reference Rinith2018). The panegyric inscription (praśasti), formulated in Sanskrit verses, narrates the heroism and glory of a certain King Īśānavarman. Presumably this Īśānavarman was the great King of Zhenla (c.mid-610s–637 AD), son of, and successor to Mahendravarman, who took Īśānapura (Sambor Prei Kuk) as his capital. In the inscription, he is said to rule over a “Golden Land extending as far as the sea” or a “Golden Earth bounded by the ocean” (samudraparyantasuvarṇabhūmi, according to the provisional reading still unpublished). There is no reason to think, however, that the ‘Golden Land’ or ‘Golden Earth’ mentioned here refers to a specific region of Southeast Asia, and certainly not ancient Cambodia (Zhenla 真臘). Moreover, there is also no reason to suppose, as Dr Vong Sotheara has, that this entire land was actually ruled by this king. To do so implies that most of the lands under his alleged control in Southeast Asia, both mainland and maritime, used to be part of ancient Khmer territory. On the contrary, everything about this stanza seems to describe a fictional setting of no specific historical or geographical importance. Indeed, given the nature of these panegyric inscriptions in India and Southeast Asia as a medium for royal propaganda (e.g. Francis Reference Francis2013, Reference Francis2017), it is quite possible that no location in the real world was even alluded to. It is therefore more probable that the Sanskrit compound suvarṇabhūmi was used here as a metaphor, rather than as a proper name of any country (private communications with Dominic Goodall, Arlo Griffiths, and Kunthea Chhom), or, even more simply, was a generic toponym widely referring to the offshore or coastal lands to the east of India, beyond the Bay of Bengal. Finally, the immediate context of this epigraph provides no indication whatsoever that this ‘Golden Land’ was Buddhist, or that it received the Buddhist mission of King Asoka as stated in the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa. Thus, this newly discovered inscription does not affect the main arguments of this article.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was originally accepted in 2011 for publication by the now defunct Mahachulalongkorn Journal of Buddhist Studies, but never saw the light of day. Since then, the paper has been updated and presented at several national and international venues, most recently at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, on 1 December 2017, on the occasion of the conference entitled Maritime Silkroad in Southeast Asia: Crossroad of Culture. I would like to take this opportunity to thank colleagues of the Institute for East Asian Studies at Sogang University (SIEAS), particularly Dr Heejung Kang, for their invitation to present my research paper at this conference, supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant NRF-362-2008-1-B00018), and for offering me the opportunity to publish it in TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. I am also greatly indebted to numerous scholars with whom I have had the chance to discuss the subject matter over the years. So many colleagues have helped with information and comments that I cannot possibly mention them all here. However, special thanks are due to Donald Stadtner, Leedom Lefferts, and Peter Masefield for their valuable assistance in editing the final version. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the gracious assistance of the Thai Research Fund (Grant RTA5880010) for their continued support.

Abbreviations

- Dīp.:

Dīpavaṃsa

- ExtMhv.:

“Extended Mahāvaṃsa”

- FAD:

Fine Arts Department of Thailand

- K.:

Inventory number for Khmer inscriptions

- Mhv.:

Mahāvaṃsa

- Nidd:

Mahāniddesa

- Sp:

Samantapāsādikā (Vinaya Commentary)