Introduction

Southeast Asia has stood at the crossroads of China, the Indian Subcontinent, and the Arab world for more than two millennia. The mobility and migration of merchants, explorers, diplomatic envoys, and missionaries prompted intensive exchanges between Southeast Asians and other foreign cultures within the region. Throughout the centuries, Southeast Asia became a site for cultural exchanges manifested in a shared language (Malay), social practices, architecture, and religious syncretism. As early as the fourth century, Hinduism and Buddhism strongly influenced Southeast Asian civilisations. These religions, patronised by rulers who converted to Buddhism or Hinduism, determined socio-cultural practices that integrated distinctive local features in a blend of forms, styles, and materials.

The 20th and the 21st centuries have exhibited intensive interactions and integration between different cultures, societies, and world powers. During the last decades, globalisation processes have linked to international phenomena of cultural loss. A primary concern is that globalisation, in its continuous and unprecedented acceleration and intensification of values, capital, human migrations, information, and technology worldwide, has a homogenising influence on traditional cultures (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1990, Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1996; Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Stenou2002; Berry Reference Berry2008; Robertson Reference Robertson1998; Sotshangane Reference Sotshangane2002). Whilst globalisation promotes interaction and tolerance between cultures and societies (Berggren and Nilsson Reference Berggren and Nilsson2015; Wang Reference Wang2007), there is also the danger of privileging hegemonic and transnational cultures over traditional and regional societies, leading to the loss of cultural identity. This situation is particularly evident when traditional societies expose themselves to rapid modernisation through models imported or imposed externally and do not gradually adapt to a new context, as with Brunei Darussalam. Historically, societies have wielded architecture as cultural, political, and religious hegemony to suppress traditional cultural values.

Interestingly, expressing local cultural values and identities in architecture is noticeable in many parts of the world, especially in the post-colonial context. The persistence of vernacular architecture design carries memory and collective identity. Throughout the 20th century, Brunei Darussalam experienced dramatic transformations. The long-lasting British rule from the 1880s to 1984, the discovery of oil in the late 1920s, the Japanese occupation in the 1940s, and Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's implementation of national development plans in the 1950s tremendously impacted the country's built environment. In 1967, the coronation of His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah signalled the movement towards Brunei's independence and the proclamation of the State philosophy, Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB) (Malay Islamic Monarchy), which underlines institutionalising Islam as a state religion, preserving Malay cultural values, and accepting the monarchy's leadership. Naturally, architecture in Brunei reflected the economic, cultural, social, religious, and political changes of the last 65 years.

Nevertheless, although Brunei's built environment conveys identity, the current legislation overseeing the safeguarding and classification of architectural heritage does not address preserving and conserving mosques and other religious architectural structures specifically. As discussed below, none of the mosques is listed as heritage or classified as a monument. However, the Department of Mosques, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and, in many cases, the collective effort of congregants assure their safeguarding, maintenance, and preservation.

This paper examines how the State and communities use architectural design's interpretations of culture to preserve and promote Bruneian cultural identity, using mosque architecture in Brunei as a case study. It analyses the tensions and negotiations between international stylistic and formal conventions and the integration with vernacular architecture and other forms of expression of Bruneian cultural identity. As in many other regions where Islam is the predominant religion or is well established, mosque architecture in Brunei reveals eclectic styles where typical structural forms adapt to a vernacular architectural style and function, occasionally with clearly intentional Arab-looking styles. This study argues that contemporary architecture became crucial to the construction and formation of cultural identities and that it rethinks concepts of historicism, tradition, post-national identity, and tensions within nation-state perception/projections at a global level (Delanty and Jones Reference Delanty and Paul R.2002; Djiar Reference Djiar2009; Vale Reference Vale1992). This phenomenon is particularly evident in post-colonial settings and emerging economic powers (Bunnell Reference Bunnell2017; Moser Reference Moser2012; Moser and Wilbur Reference Moser and Shamsa Wilbur2017; Ogura et al. Reference Ogura, Yap and Kenichi2002). With the rapid economic growth of several Islamic states, particularly in the Gulf, architects have posed questions about identity, heritage, and negotiating the apparent contrasts between traditionalism and modernism (Ardalan Reference Ardalan and Katz1980; Gharipour Reference Gharipour2011; Kultermann Reference Kultermann1999; Mahgoub Reference Mahgoub2007; Powell Reference Powell1983; Sadali Reference Sadali and Katz1980). Thus, this paper questions how mosque architecture reflects Bruneian Muslim identity. How does mosque architecture negotiate state ideology, tradition, identity, and adaptation?

Literature Review

Although several 20th-century scholars explored Islamic architecture in general and mosque architecture in particular along the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and South Asia, scholarship has disregarded Islamic art and mosque architecture in Southeast Asia. The exception is Martin Frishman and Hasan-Uddin Khan's comprehensive approach to mosque architecture, including sections on Southeast Asia and a global overview of contemporary mosque architecture (Khan Reference Khan, Frishman and Khan1994; O'Neill Reference O'Neill, Frishman and Khan1994). However, some scholars, mainly from Malaysia and Indonesia, have studied Islamic architecture in the Malay World. Abdul Halim Nasir collected an inventory of mosques in Malaysia. He characterised mosque architecture in the Malay world through a dichotomy between traditional and non-traditional elements and formalistic analysis of indigenous technical aspects concerning the tropical climate (Nasir Reference Nasir1984, Reference Nasir2004). A. Ghafar Ahmad separated mosques into three typologies: vernacular, colonial and modern. He contextualised the development of mosque design within its historical and cultural significance (A. G. Ahmad Reference Ahmad1999). David Mizan Hashim summarised the history of mosque architecture in Southeast Asia, examining mosque architectural styles as a practising architect and dividing mosques into Southeast Asian, Mughal, and Western/Modernist (Hashim Reference Hashim1990). Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi observed mosques’ architectural styles’ devolution in Malaysia within a historical and religious (Quran and Sunnah) framework. Mohamad Tajuddin also comprehensively classified mosque architectural styles and sub-styles and saw mosques as reflections of cultural, ideological, socio-political, and religious influences (Rasdi Reference Rasdi2000, Reference Rasdi2007, Reference Rasdi2014). More recently, scholars in the field of architecture, urbanism, engineering, and planning have probed mosque architecture in Malaysia and the Malay world, identified formal relationships between early and contemporary mosques, and analysed their structural and typological classifications (A. A. Ahmad et al. Reference Ahmad, Ali and Ezrin2013; Alice Sabrina Reference Alice Sabrina2008; Shah et al. Reference Shah, Arbi and Inangda2014; Sharif Reference Sharif2013; Sharif and Hazumi Reference Sharif, Hazman and Barkeshli2011).

Nevertheless, most academic research on mosque architecture in Southeast Asia focuses on Malaysian and Indonesian mosque architecture and seldom includes other countries within the region, such as Brunei Darussalam. To date, the study of mosque architecture in Brunei Darussalam remains unexplored, except for Jabatan Hal Ehwal Masjid's mosque inventories (Department of Mosque Affairs) under the Ministry of Religious Affairs and a handful of studies on the historical development of mosque construction (Ali Reference Ali1989; Azadah Reference Azadah1992; Badarudin et al. Reference Badarudin, Endut Moesi, Fernandez, Hock, Lim, Horayangkura and Lim2001; Department of Mosque Affairs 2000; Jabatan Pengajian Islam 1996; Syara'iah Reference Syara'iah1993). One of the most significant contributions to the study of mosque architecture in Brunei was the seminar that the Prime Minister's Office of Brunei Darussalam organised in collaboration with the State Mufti's Office, Mosque Affairs Department of the Religious Affairs Ministry, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, and the Brunei Darussalam Islamic Dakwah Centre (Juned Reference Juned2004). Officials from the Mufti State, academics from the Sultan Omar 'Ali Saifuddien Centre for Islamic Studies at Universiti Brunei Darussalam, architects from the Public Works Department, and several representatives of religious affairs in Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore gathered to discuss the theme Mosque: Platform for a Monarch Leadership (Juned Reference Juned2004). The seminar aimed to examine the mosque in relation to Brunei as an Islamic nation and analyse how mosque architecture expresses cultural identity and state ideology (Badarudin Reference Badarudin2004).

Consequently, this paper's chief objectives are to examine mosque architecture in Brunei by understanding the relationships between culture and the built environment. It studies architectural elements and styles within the specific context of MIB, integrating symbolic elements related to monarchy and expressions of Malayness: Iconography associated with Malay / Bruneian material culture, expressions of Malay cultural identity, and structural features of Malay vernacular architecture.

As of November 2018, the Department of Mosques, under the Ministry of Religious Affairs, categorised nearly 120 mosques in Brunei via their capacity and other facilities besides communal prayers, such as library study rooms and administration offices. The four categories are negara (national), utama (main), mukim (municipal)Footnote 1 and kampong (village). As this study concentrates on the State concept that combines Islam, monarchy, and Malay cultural traditions, we have selected 37 mosques representing Brunei's mosque categories except kampong (village). Village mosques are primarily for a small capacity and serve an undersized community's spiritual needs. Therefore, if there is a clear relation between MIB and mosque architecture development, it most likely exists in the national, main, and municipal mosques, as they are on par with the hierarchy of Islamic Governance in Brunei.

This study selected mosques spread across the four districts: Brunei Muara, Temburong, Tutong, and Belait. Their construction ranges from 1954 to 1999, across the reigns of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III and His Majesty Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah. The chronological span is divided into three: the Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien Period (1950–1967), the Begawan/Hassanal Bolkiah Period (1967–1986), and the Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Period (1986–2018). The Begawan/Hassanal Bolkiah Period refers to the time after Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III abdicated in favour of his son in 1967 until his passing in 1986. Although Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III abdicated the throne, he remained His Majesty's advisor. He had a pivotal role in the country's independence and developing its civil and religious infrastructure, which is noticeable in its architectural design.

To fully understand how MIB relates to the development of mosque architectural styles, it is imperative to discuss Islam and Islamic architecture's evolution in Brunei Darussalam.

The Sultanate of Brunei Darussalam

Most of what we know about the early history of Brunei is through Chinese records from the Tang to Song dynasties, old Javanese manuscripts, and accounts written by Portuguese and Spanish merchants, diplomats and navigators. Additionally, there are the three known versions of the Salasilah Raja-Raja Brunei, a genealogy of the Sultans of Brunei that the Datu Imam Yaakub probably compiled in the mid-eighteenth century, allegedly commissioned by Sultan Muhammad Alauddin (Tengah Reference Tengah and Gin2015).Footnote 2 Other sources useful for comprehending Brunei's history and the spread of Islam within the nation are tombstones, artefacts collected from several shipwrecks, folktales, and other oral traditions, such as the epic poem Sh'er Awang Semaun.

Despite ongoing debates regarding Brunei's early history, historians generally accept that Arab and Muslim traders arrived in Brunei as early as the tenth century and that the kings of Brunei converted to Islam sometime between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Some scholars argue that the first ruler to embrace Islam was Awang Alak Betatar after he married a princess from Johor (Old Singapore) around 1368, becoming known as Sultan Muhammad Shah. Others refer to an interpretation of Portuguese and Spanish accounts and claim that Islam became a State religion most likely in the sixteenth century (Nicholl Reference Nicholl1975; Pehin Tuan Imam Datu Paduka Seri Setia Ustaz Haji Awang Abdul Aziz Juned Reference Juned2008).

This section of our study does not assert Brunei's historical origins or the exact moment of Islam's arrival to Brunei. Instead, it aims to understand the spread of Islam in Brunei and the monarchy's role in observing the teachings of Islam by constructing mosques and religious schools, establishing religious institutions, and implementing other mechanisms to spread and adhere to Islam.

According to the Salasilah Raja-Raja Brunei, Islam's influence spread quickly during the reign of Sultan Sharif Ali (r. 1425-1432), who probably built the first mosque in Brunei, “promoted the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad,” and reorganised the nation's defence (Sweeney Reference Sweeney1968). During the sixteenth century, western accounts often referred to the Sultans of Brunei as Muslims and followers of Muhammad. These sources also frequently mention the missionary activities of Bruneian Muslim theologians in the Philippines and other parts of Borneo, often accompanied by missionaries from Mecca, leading eventually to the famous Castilian War and the burning of the mosque in Brunei in June 1578 (Correia [1858] Reference Correia and de Lima Felner1556; Loarca Reference Loarca1582).

As Father Domingo de Salazar stated, “The law of Mahoma has been publicly proclaimed, for somewhat more than three years from Burney and Terrenate who have come there (Mindanao) (…) they have erected and are now building mosques, and the boys are being circumcised, and there is a school where they are taught the Al-Quran” (Salazar Reference Salazar1583).

We can assume that if Brunei could build several mosques and maintain religious schools in Mindanao by the end of the sixteenth century, it could do so in Brunei itself, where Islam and Shariah law undoubtedly had a solid foundation. The Salasilah Raja-Raja Brunei provides some details regarding Brunei's system of government comprising a combination of canon laws, Islamic laws, and customary laws. The Wazir, Pengiran Temenggung, was responsible for religious matters and had assistance from Cheteria and Menteri Ugama, a kind of Mufti and Ministers of religious affairs responsible for an Imam's duties in the mosque and advisers to the Sultan on religious laws and regulations (Sweeney Reference Sweeney1968).

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Brunei sovereignty began to weaken, resulting in the loss of territories across Borneo and the Philippines. The Dutch and the British colonial empires spread their control in Kalimantan, and North Borneo and Brunei ended up as British protectorates until they regained their independence in 1984. The British Empire governed Brunei under British laws and constitution, controlling every matter in Brunei governance except religious affairs and State customs. However, the British constitution and civil laws objectively affected and limited Brunei's implementation and observance of Islamic laws and religious practice.

Islam and Architectural Development in Brunei from 1950 to the Present

In the 1950s, after Sultan Haji Omar Ali Saifuddien III ascended to the throne, a new era dedicated to strengthening Islamic administration began. It led to the Islamic Religious Council's establishment, which deals with religious affairs, and the Adat Istiadat Council, which deals with Malay traditional customs. During Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's reign, many mosques were constructed in new locations or replaced old and smaller mosques.

During the first years of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's reign, the government of Brunei initiated discussions to draft a written constitution that was finally signed on 29 September 1959. In Chapter III, Article 1 of the written Constitution states that “the religion of Brunei Darussalam shall be the Muslim Religion according to the Shafeite sect of that religion” (Part 2, 3(1)). From the 1960s until his abdication in 1967, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III strove to establish Islam, construct several mosques, and revise and modernise the education system, including observing Islamic teachings and conserving Malay cultural traditions. As mentioned earlier, after his abdication in favour of his son, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III retained a prominent role in the country's leadership towards independence. Under his direct supervision, the nation erected many architectural works germane to Brunei's cultural and religious identity. Some of these examples are the Arts and Handicrafts Training Centre, built in 1975 to preserve the crafts and artistic traditions of the Brunei Malays, the Brunei Museum (1972), and other relevant religious, government, and administration buildings.

Upon ascending to the throne on 5 October 1967, His Majesty pledged to uphold and protect Islam and the State's customs and traditions. One of his first official ceremonies was the opening ceremony of the Kuala Belait Religious Affairs Department in which His Majesty reiterated his responsibility as head of the religion of Islam in the State and his commitment “to provide the necessary facilities to Muslim ummah in the whole country for any activity deemed beneficial to Islam” (Juned Reference Juned2008). Shortly after, a Religious Teachers College and other religious education institutions were built to produce religious teachers and provide qualified officers in Quran recitation, preaching, and other spiritual activities. Along with the religious and educational development that occurred before and after Brunei's independence in January 1984, His Majesty consented to construct mosques across all four districts.

On 1 January 1984, during the independence of Brunei, His Majesty expressed his desire to make Islam not only a way of life but also the State's governing principle, policy, and philosophy. He declared that Brunei should remain “forever a sovereign, democratic and independent Malay Islamic Monarchy based upon the teachings of Islam according to Ahli Sunnah wal-Jema'ah (…)” (Juned Reference Juned2008).

During His Majesty Haji Hassanal Bolkiah's reign, religious affairs underwent profound restructuring and development. It started with the establishment of the Ministry of Religious Affairs in 1986 (previously the Office of Religious Affairs [1954], the Islamic Religious Council [1955], and Brunei Islamic Religious Affairs [1956]) and the re-establishment of the State Mufti of Brunei in 1992.Footnote 3 The Mosque Department is under the Syariah Affairs Department and bears responsibility for the mosques’ management and activities. Since the 1950s, mosque construction has been part of the five-year National Development Plans. The Public Works Department (PWD) directs and oversees their design and construction in collaboration with the Department of Religious Affairs.

All existent mosques in Brunei were built during the reigns of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien and His Majesty Haji Hassanal Bolkiah between 1954 and 2018 (Azadah Reference Azadah1992; Department of Mosque Affairs 2000; Syara'iah Reference Syara'iah1993). This paper's authors collected data that demonstrates that 73 mosques (more than 70%) were built between 1978 and 2000. These activities correspond to the urban and infrastructure development concerning Brunei's independence in 1984 and the Asian financial crisis in 1997. In 1994, ten mosques were officiated in Brunei, including the Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque, the largest in the country, accommodating 5,000 worshippers. The mosque is a waqf from His Majesty. The substantial number of mosques constructed that year may mark and celebrate the tenth anniversary of Brunei's independence and affirm Brunei as a Malay Islamic Monarchy.

Historically, architecture has articulated and embodied governmental and administration agendas, and Brunei is no exception. Since the early times, Brunei governance has combined three systems: Adat Istiadat Diraja (Royal Brunei Customs and Traditions), Sharīʿah (Islamic laws), and Adat Istiadat Melayu (Malay Customs and Traditions). This threefold jurisprudence in Brunei Darussalam's legal system assures the practice and observance of MIB. Therefore, all matters are subject to this system, including architecture. These three systems have a rigid hierarchy: Islamic law overpowers Royal Brunei customs and traditions as well as Malay customs and traditions. As a result, Islam, monarchy symbols and values, and the expression of Malay cultural identity inform Brunei's architectural styles, especially its government and institutional buildings. Naturally, this condition includes mosques, as Islam is Brunei's state religion.

Melayu Islam Beraja Architecture as a National Identity

Besides developing cultural and creative industries in Brunei Darussalam, the government, through the MIB Supreme Council, has been collaborating with Pertubuhan Ukur Jurutera & Arkitek (PUJA – Brunei Association of Surveyors, Engineers and Architects) since 2012 to encourage and promote applications of MIB principles in architectural practice to define Bruneian civil and religious architecture. In February 2013, PUJA and the MIB Supreme Council co-organised a seminar with the theme ‘Upholding Malay Islamic Monarchy Architecture.’ The seminar aimed to increase architects’ and professionals' awareness of building design and construction concerning preserving and upholding MIB identity in Brunei architectural design (Juned Reference Juned2016). It emphasised that MIB architecture considers the form and design of Brunei's way of life. The design should evince Islamic elements and Malay, royal, and ceremonial characteristics. The seminar also elaborated policies to prioritise MIB architecture and reject any architectural forms that conflict with MIB. Thus, the organisers officially recognised MIB architecture as Brunei's national form, making Islamic features mandatory. This policy applies mainly to projects for government buildings. Architects in Brunei often discuss definitions of Bruneian architecture during PUJA seminars, its relationship to Malay cultural expressions and Islam, and how it affects principles of national identity. Their talks attest to governmental and professional volitions to incorporate Islamic, Malay, and, eventually, royal elements in Brunei Darussalam's national architectural styles (Latif Reference Latif2014).

The Al Falaah School exemplifies the architectural integration of MIB and building design. The school's location atop a hill represents the Raja's (king) superior status. Its application of a traditional standard measurement refers to Malay culture, and the design of the arches, columns, and arcades follow styles of Islamic architecture (Latif Reference Latif2014).

Naturally, Middle East examples stylistically inform mosque architecture. Moreover, the mosque's function necessarily standardises its architectural elements throughout the world. However, regional styles, expressions of cultural identity, and environmental characteristics permeate Islamic architecture, resulting in a substantial eclectic style. As Brunei Darussalam proudly upholds the values of Islam, Malay culture, and the monarchy government to preserve its identity and traditions, it is crucial to understand Brunei's unique mosque architecture styles and how MIB has defined the integration of cultural identity features.

Mosque Architecture Styles and Expressions of Cultural Identity in Brunei Darussalam

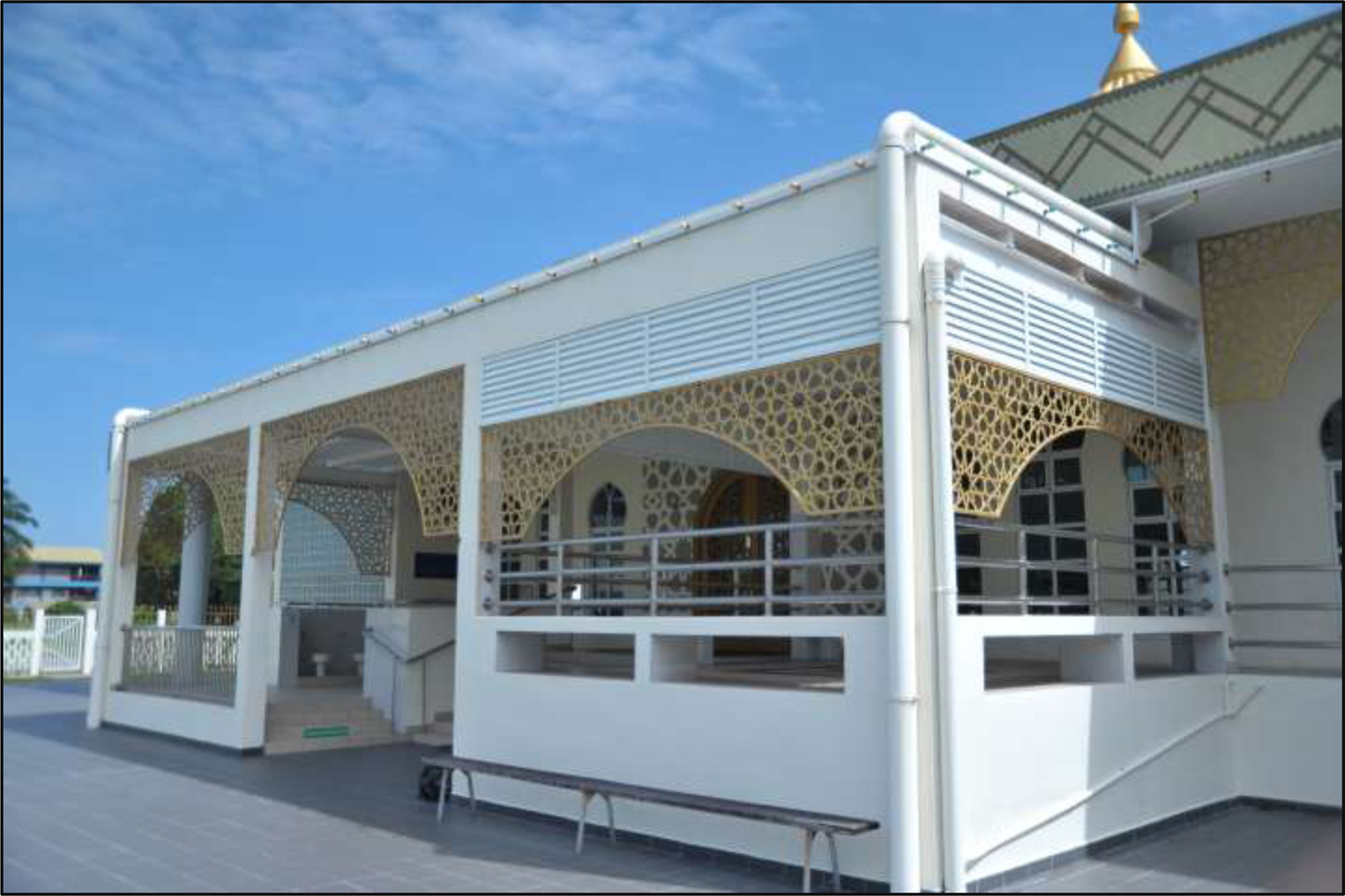

Before the 1950s, mosques comprised timber and other natural and perishable materials such as bamboo and palm leaf. Archival drawings and photographs of these mosques dated from the late nineteenth and early 20th century illustrate that all of these mosques followed a Malay vernacular or indigenous architecture style and incorporated appropriate construction technology suitable for the local climate and cultural setting (Figure 1). The mosques were essentially a wooden square hall on wooden stilts accessed through stairs, with a pyramidal roof that was sometimes multi-layered to allow ventilation (Nasir Reference Nasir2004). The tiered roof was often taller and more vertical than any other building and had a roof-crown pinnacle. Some of these mosques included other architectural features common in traditional Malay houses, such as a verandah (porch). The vernacular mosque architecture style typically did not have domes and minarets, which became more common when constructed in concrete after the 1950s. Early mosque architecture in Brunei did not differ much from other parts of the Malay world, across the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia, which reflect elements borrowed from Hindu and Buddhist temples (Ali Reference Ali1989). Some examples are the Demak Grand Mosque in Central Java, the Yogyakarta Grand Mosque, and another three mosques in Malacca: Tengkera, Kampung Keling, and Kampung Hulu. Frequently, the main prayer halls had another annexed roofed area surrounded by a hypostyle, locally known as balai adat (Figure 2). These structures typically accommodated Quran readings, religious schools, and other congregational activities.

Figure 1. Early 20th century mosque Brunei Darussalam.

Figure 2. Balai Adat at Jamalul Alam mosque, Kuala Belait.

During Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's reign, some masonry mosques replaced old timber mosques, increasing their capacity and using more durable materials. Unlike in Malaysia and Indonesia, none of Brunei's old wooden mosques survives today. They were destroyed or demolished during the Japanese occupation and replaced by newer brick and concrete structures. The current legal framework for safeguarding and preserving architectural heritage in Brunei is in Chapter 31 of the Antiquities and Treasure Trove Act of 1967. The document defines “ancient monuments and historical sites” as “any monument in Brunei Darussalam which dates or may be reasonably be believed to date from a period before 1 January 1894, and includes any other monument which has been declared by order of His Majesty in Council” (Attorney General's Office 1967). As of 2018, the government had gazetted and classified only 27 buildings and sites as ancient monuments and historical sites, and none are mosques or sites of old mosques (Attorney General's Office 2006, 2007). Comparatively, the Department of National Heritage in Malaysia has taken an essential role in conserving and preserving old mosques, as it recognises their value in developing the tourism industry (Harun Reference Harun2011). Several mosques in Malaysia have earned classification as ancient monuments. In Singapore, six of the 73 monuments and structures classified as national monuments are mosques.

Many of the old mosques in Brunei were bombed and destroyed during the Japanese war between 1942–1945, and new mosques were often built on the same site. Therefore, during Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's reign, Brunei underwent urban and infrastructure development that determined Bruneian architectural style's shape (Badarudin et al. Reference Badarudin, Endut Moesi, Fernandez, Hock, Lim, Horayangkura and Lim2001).

Modern and contemporary mosque architecture styles in Brunei are generally eclectic, with some mosques combining the typical Arabic and Indo-Islamic characteristics with onion-shaped domes, tiles, Moroccan carved walls, horseshoe arches, lancet arches, ogee arches, and trefoil arches supported on marble or granite columns with structural and ornamental expressions of Bruneian cultural identity. Despite taking inspiration from conventional international styles and materials, many mosques in Brunei utilise traditional and vernacular architecture styles and local decorative elements. Notwithstanding renovations and extensions, some of the oldest mosques from the 1950s and 1970s reveal traditional materials and construction methods to acclimatise their interior temperature. Additionally, mosques in Brunei frequently boast facilities that correspond to Malay cultural and social practices, such as balai adat for Quran reading, halls for Quran recitation, areas reserved for royal solemnisation and royal ceremonies, and local Islamic celebrations.

The National Mosques

Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque and the Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque are the only national mosques and are considered the most significant and remarkable mosques in Brunei. Resulting from personal endowments from the late Sultan in 1958 and His Majesty Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah in 1994, respectively, these mosques represent national monuments in the collective memories of Brunei Malays. These mosques symbolise the unity between the monarchy and Islam as a state religion and are places for worship and prostration within a Malay Muslim community. With a surrounding artificial lagoon on the fringes of the Kedayan River and facing the water village, the SOAS mosque metaphorically connects the river and the historical roots of Brunei and its people (Figure 3). Despite the evident Mughal-style architecture, fortress-like body, and minarets crowned with a small dome-shaped pavilion known as chhatris, the mosque incorporates elements of Malay culture. The most apparent of these elements is the ornamental concrete boat in the centre of the lagoon, a replica of Sultan Bolkiah's boat. Since 1967, one has accessed the boat, which served as a madrasah and for Quran reading, through a pathway. It crosses the lagoon from the south transept of the mosque and beside the ablutions area (Figure 4). The boat's design mirrors a longboat that the indigenous peoples of Borneo traditionally used for royal ceremonies, funerary rituals, and war. Its bow and the stern take the shape of a bird, perhaps a hornbill, a sacred bird among many indigenous peoples of Borneo. In the centre of the hull is a hypostyle pavilion with a pyramidal and layered roof. Two smaller pavilions flank a pavilion with a high double-tiered roof (bumbung panjang). The boat's shape parallels those that the Ngaju, the Ot Danum, the Lawangan, and other indigenous peoples of Borneo traditionally utilised. One frequently finds representations of the ceremonial boat in cloth paintings, mural paintings, woodcarvings, and, occasionally, in European drawings. Ridges in the shape of a ceremonial shield known as a kelasak ornament the pathway to the boat and around the lagoon, while floral and vegetal motifs related to royal regalia and patterns and designs from Bruneian textile weaving decorate the entire boat. The finial on the main pavilion boasts the royal insignia of Sultan Sharif Ali.

Figure 3. Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III mosque, Bandar Seri Begawan.

Figure 4. Mahligai, replica of the Sultan Bolkiah's ceremonial boat, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III mosque, Bandar Seri Begawan.

Finally, the ablution area in the mosque's south transept and the water fountain in the north transept both feature a mosaic resembling the patterns, designs, and colours used in the finest of the Brunei songket textiles (Figure 5). Brunei proudly esteems these traditional textiles as its finest craft, and they play an essential role in royal traditions (Wahsalfelah Reference Wahsalfelah2005, Reference Wahsalfelah2014, Reference Wahsalfelah2015).

Figure 5. Fountain bed, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III mosque, Bandar Seri Begawan.

In 1994, during the Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque's construction, renovation occurred at the SOAS mosque, adding new ornaments to the vault of the main hall and the entrance ceiling. Brunei deems a foliage pattern known locally as air muleh as a national pattern and frequently uses it as architectural decoration in religious and secular buildings. Allegedly, the pattern symbolises Bruneians’ character and the ontological identity of the Brunei Malays (Latif Reference Latif2014).

The Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque features air muleh patterns in its interior, minaret walls, entablatures, glasswork, and the chandeliers' structure and glass lamps (Figures 6 and 7). The ‘pixelated’ pattern in the minarets resulting from octagonal tesserae recalls the techniques and geometric patterns of Bruneian traditional woven textiles. The main hall's chandelier also features a very discrete sequence of wing pairs, an element of the royal and national insignia.

Figure 6. Jame' Asr Hassanal Bolkiah mosque, Bandar Seri Begawan.

Figure 7. Ayer Muleh pattern design, Jame' Asr Hassanal Bolkiah mosque, Bandar Seri Begawan

The Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque is a duplex mosque; therefore, there is a main hall and a semidetached subsidiary hall for male and female worshippers. The octagonal plan of both domed halls, next to each other and linked by a passageway, recalls the plan of the Dome of the Rock and the adjacent Dome of the Chain, formerly a prayer house. In the Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque, only the main hall has four tall and bold minarets at its corners. However, the whole mosque has 29 domes, symbolising His Majesty Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah as the 29th Sultan of Brunei. Another structural element borrowed from Malay vernacular architecture in the Jame Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque is the sloped roof, upon which rests the dome's drum. As previously mentioned, Malay mosques typically had pyramidal tiered roofs instead of domes. Gradually, a drum and a dome replaced the top layer and apex of the pyramid. In the Malay world, especially in Brunei and Malaysia, mosques are frequently designed with square, pentagonal, or octagonal slopped roofs supporting a round, square or octagonal drum and a dome (Kassim et al. Reference Kassim, Nawawi and Majid2018; Nasir Reference Nasir1984, Reference Nasir2004).

The Main Mosques

The majority of the main mosques (masjid utama) in Brunei were built during the reign and lifetime of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III. The late Sultan directly supervised their design and many other government buildings and is often mentioned as the SOAS mosque's designer. As a result, there is a clear and distinctive architectural style in Brunei between the 1950s and the late 1980s. One of the most idiosyncratic mosques built during SOAS III's reign is the Setia Ali Mosque in Muara. The mosque was completed in 1961 and designed with a square hall positioned on a raised platform supported on stilts and a surrounding veranda (Figure 8). It has a low conical roof with a series of semi-circular arch-vaults converging from the base to the roof's apex, similar to an open umbrella. This umbrella-shaped dome became popular in Brunei and Malaysia. The National Mosque in Kuala Lumpur, commenced in 1963 and completed in 1965, is probably the most well-known example of a semi-open umbrella-shaped dome. In Brunei, throughout the 1960s to the 1980s, several other mosques incorporated an umbrella-shaped dome in a considerable variety of styles. They include the Jamalul Alam Mosque (1963), Kampong Kiudang Mosque (1972), Kampong Danau Mosque (1972), Kampong Tanjong Maya Mosque (1973), Mohammad Bolkiah Mosque (1979), Zinab Mosque (1985), Sultan Sharif Ali Mosque (1986), Al-Muhtadee Billah, and the Sungai Kebun Mosque (1987) (Figure 9). The diversity of styles demonstrates how the umbrella-shaped dome transitioned from pyramidal Malay roofs to a round or onion-shaped dome. The umbrella-shaped domes became outmoded after the passing of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III. This type of dome was so innovative and popular in Brunei that minarets sometimes adopted it. Its origin most likely relates to an ancient royal symbol in Brunei that appears on the new one-cent coin released in conjunction with the golden jubilee of His Majesty coronation. The Payung Diraja, or royal umbrella (parasol), is also a structural iconographic element in the national emblem, known as Panji-panji. According to the customary royal laws, the royal umbrella traditionally protects the Sultan on his way to attend formal ceremonies. It is a symbol of royal honour, peace, tranquillity, and justice. One of the earliest representations of the winged umbrella is on Bruneian coins known as Pitis, minted in 1868.

Figure 8. Seti Ali mosque, Muara Town.

Figure 9. Jamalul Alam mosque (1963), Kampong Kiudang mosque (1972), Kampong Danau mosque (1972), Kampong Tanjong Maya mosque (1973), Mohammad Bolkiah mosque (1979), Zinab Mosque (1985), Sultan Sharif Ali mosque (1986), Al-Muhtadee Billah mosque, Sungai Kebun (1987).

Like several other mosques in Brunei, the Setia Ali mosque has been through substantial renovations, resulting in a significant loss of its original and unique design. Initially, the mosque had half-open walls of ornamental perforated bricks suitable for a tropical rainforest climate, allowing air to circulate and cool the main hall. In recent years, glass windows with sliding doors have replaced the bricks. The renovators reused the bricks to decorate the exterior walls of newly-built facilities, thus losing their original function.

The transition of many Brunei mosques from wooden architectural structures to masonry and stone construction preserved essential traditional elements, such as an exposed interlocking beam network, which became more aesthetic than structural. These remained an inheritance of Malay vernacular architecture and the distinctive identity of Malay mosque architecture. The Hassanal Bolkiah mosque in Tutong and the Muhammad Salleh mosque in Temburong, completed in 1966 and 1968, respectively, are ornamented with distended and crossed exposed beams in the main corners of the building, simulating traditional mortise and tenon joints (Figure 10). In some instances, such as in Mohammad Bolkiah Mosque, the ornamental beams form a geometric pattern between the main hall and the female prayer hall and the ridges of the octagonal roof in the ablution areas.

Figure 10. Hassanal Bolkiah mosque, Tutong; Muhammad Salleh mosque, Temburong.

During His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah's reign, the integration of the dome and other Arabic architectural style elements became more predominant in mosque architecture and secular buildings. Lambak Kanan Mosque in Brunei-Muara district replicates Perpindahan Kampong Pandan Mosque in Kuala Belait. These mosques have a central quadrangular floor plan with a pyramidal roof topped with a pentagonal drum that intertwined lancet windows and an oval-shaped dome pierce. All vertices of the main hall have a two-level chhatri. The mosques have two minarets that adhere to the design of the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi minaret.

Al-Ameerah Al-Hajjah Maryam Mosque in Jerudong also displays a classic Arabic style with a quadrangular hall, straight lines, and round drum pierced with segmental windows and topped with a round dome (Figure 11). The mosque features typical designs with onion-shaped and lancet arches in the main gates and pointed horseshoe arches in the windows and ablution area surroundings. The mosques' interior and exterior reveal profuse ornamentation, with lancet and onion-shaped arches, geometric patterns, Islamic calligraphy, and two overlapping squares, known as Rub el Hizb, decorating the ceilings and water fountains. Like the two national mosques, most of the main mosques built during His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah's reign used noble construction materials such as marble and granite, bronze gates, and intricate stucco and tilework.

Figure 11. - Al-Ameerah Al-Hajjah Maryam mosque, Jerudong.

The Municipal Mosques

In Brunei, there are 24 municipal mosques (masjid mukim), all built during the reign of His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah. Due to their capacity, small congregations, and often less-centralised locations, municipal mosques primarily possess tiered pyramidal roofs, many of them without a dome. The design presents a quadrangular floor plan and outward gables supported by concrete pillars, often using modest materials and construction methods traditional to residential architecture. Occasionally, the mosques have specific spaces for socio-religious functions such as wedding ceremonies, congregational feasts for special celebrations, and sheltered areas (balai adat) for Quran reading. Dato Idris Haji Abbas designed Universiti Brunei Darussalam Mosque, completed in 1994 following what the architect himself calls ‘vernacular Brunei architecture style’ (personal statement) (Figure. 12). The architect identifies three defining concepts for UBD Mosque's design: Tropic, Malay, and Islam. These key concepts consider the importance of Malay cultural identity to most of the student community and conform with the tropical rainforest climate of Borneo. The main hall has a square floor plan, standing on a raised platform with a surrounding arched veranda.

Figure 12. Universiti Brunei Darussalam mosque, Jerudong.

The pyramidal roof, covered with clay tiles, has three tiers with four windows on each of the four sides of the elevation between the base and the middle tier. Two slightly elevated towers flank the main entrance with a lower pyramid canopy supported on four pillars. Two stand-alone sheltered structures (balai adat) flank the open-air passageway leading to the main gate of the hall, ornamented with beige, black, and pink tiles forming geometric patterns and the Rub el Hizb design. These structures are meant for Quran reading and Muslim student social interaction to strengthen unity, brotherhood, and fellowship. Architect Dato Idris Haji Abbas applied the same Malay Islamic vernacular concept, which he also defines as MIB architecture, to Suri Seri Begawan Raja Pengiran Anak Damit Mosque in Kampung Manggis/Madang (Figure 13). The mosque's design, completed in 2014, has a wide square floor plan and a tiered pyramidal roof crowned with a round drum and a small round pink dome at the centre of a square base. The mosque has two domes, as the tiered pyramidal roof covers an interior dome only visible from the prayer hall. The main prayer hall has an extended covered multipurpose area resembling a longhouse with a thatched and tiled roof. The main entrance also has a lower canopy topped with a small dome, following the exact structure of the UBD mosque. However, the architect converted the two small towers in UBD Mosque into two tall minarets moved to the front corners of Manggis/Madang Mosque's front hall. The mosque's interior presents a balanced and interlocked combination of the post, beam, and lintel structure typically found in wooden residential Malay architecture (Figure 14). The main hall's pillars have ornamental joineries that traditionally support porch roofs. The simulacra of wood materials customary in vernacular architecture also occur in the fascia board's shark-teeth design that runs along the lower edge of the roof, as at UBD Mosque. Brunei mosque architecture continually uses and adapts this element, and the Brunei Malay community prizes it as one of the most distinguishing elements in traditional Bruneian architecture.

Figure 13. Suri Seri Begawan Raja Pengiran Anak Damit mosque, Kampong Manggis/Madang.

Figure 14. Interior of Suri Seri Begawan Raja Pengiran Anak Damit mosque, Kampung Manggis/Madang.

Both mosques also take strong inspiration from vernacular Malay residential architecture's modular structure. The spatial hierarchy in a Malay house clearly defines public, semi-public, semi-private, and private areas, which are modular sections interconnected by passageways (Kassim et al. Reference Kassim, Nawawi and Majid2018). Likewise, the mosques present a horizontal and extended spatial hierarchy within their perimeter and interconnected passageways, giving access to multipurpose rooms, library, study rooms, and areas for social interaction. Several other municipal mosques follow a similar vernacular design with a tiered pyramidal tile roof and characteristically extended roof areas connected to the main hall. Some of these examples are Duli Pengiran Muda Mahkota Pengiran Muda Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah Mosque and the Adnan Badarudin-designed Kampong Tamoi (1995) and Kampong Lumapas mosques (1995) (Figure 15). Occasionally the mosques are topped with round or onion shape domes, ogee or horse-shaped arches, Islamic calligraphy, and arabesques. Vegetal and geometrical patterns appear intermittently in the interior and the façade, mainly to covey that non-representational art forms are a lingua franca of Islamic art and architecture. We contend that they intentionally included markers of Islamic sacred art to emphasise their distinctiveness from Malay culture, which the mosques' main structure and unique design reflect.

Figure 15. Duli Pengiran Muda Mahkota Pengiran Muda Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah mosque, Kampong Tamoi (1995), Kampong Lumapas mosque, Kampong Lumapas.

Conclusion

The negotiation between architecture and culture plays a significant role in the built environment. In the context of religious architecture, a building is never merely a place for religious services. The mosque is a religious building embodying collective identity, memory and, nowadays, expresses local cultural identities. Mosque architecture in Brunei Darussalam projects the principles of Islamic governance under the monarchy's guidance and leadership and its intentions to relate Bruneian Malay cultural identity to Islam. The examples of mosque architectural projects considered here demonstrate a clear hierarchy of styles linked to the mosques’ organisational status. While national (Negara) and main (utama) mosques present a design that frequently takes Arabic and South Asian formalistic conventions and integrates certain expressions of traditional Malay culture identity and symbols of monarchy, Malay vernacular architecture's commonalities and traits inform and predominate in lower hierarchy mosques (mukim/municipal and kampong/village). The asymmetrical hierarchies of status that place national and main mosques on a State/official/governmental level account for these design differences. In contrast, the municipal and, especially, the village mosques are closer to the public/community sphere than the national and main mosques. As a result, the design of village mosques tends to respond to the domestic cultural setting and conform to the surrounding built environment.

This study reveals that the State concept that integrates Malay cultural identity and Islam under the monarchy's guidance and leadership informs Bruneian mosque architecture. The idea of MIB architecture is somewhat spontaneous and intangible, but one sees it in the design of the earliest mosques built during Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's reign, long before the official proclamation of MIB State philosophy. Furthermore, contemporary Bruneian architects agree with the idea of MIB architecture, its historical roots, the distinctive elements of its stylistic vocabulary, and the principles of integration that distinguish MIB architecture as the form and design of Brunei's way of life.

Significantly, the built environment in Brunei Darussalam relates to a projection of cultural identity firmly supported with the national philosophy of Melayu Islam Beraja. Thus, the perception, valorisation, and safeguarding of architectural heritage follow a set of standards that accord with local traditions, beliefs, and systems of governing.

As a result, the existing legislation that ensures the classification, valorisation, and safeguarding of architectural heritage needs revision to observe fully the international conventions defined by ICOMOS, UNESCO and other organisations working towards the conservation and protection of cultural heritage, monuments, and historical sites. Along with a reassessment of the current legislation and developing an agenda towards the classification and protection of several heritage buildings, it is vital to establish education and community awareness programmes to promote architectural heritage and cultural identity's value in Brunei Darussalam.