I don't remember the very first time I watched The Wiz (1978). Growing up in a black household during the 1980s, the film was as much a part of my upbringing as the countless hours I spent removing my Jheri curl activator from the sofa, practicing the moonwalk, or listening to my mother and sister's annual Thanksgiving argument about how much salt should go into the collard greens. What I do remember is how much I enjoyed watching The Wiz. Each Thanksgiving Day my six sisters and I would gather around the television set and watch our heroine Dorothy (Diana Ross) travel from her aunt's Harlem apartment to the magical land of Oz. We celebrated the fact that Dorothy ultimately vanquishes her seemingly more powerful foe Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West (Mabel King). As young black girls, we identified with Dorothy's plight. While we were not battling powerful witches, we were constantly resisting our mother's attempts to socialize us into “respectable” young women. As such, we were fascinated by Evillene, the most oppressive force within Dorothy's life. The gargantuan size of Evillene's body, the hideousness of her face, and the force of her supernatural powers both excited and repulsed us. We eagerly anticipated her first appearance in the film, bursting through the doors of her sweatshop belting, “Don't Nobody Bring Me No Bad News.” We reveled in drawing comparisons between Evillene and our mother, hoping that one day we too could defeat her.

The Wiz took on greater meaning as I traversed the waters of black girlhood. When I was about seven years old, I learned that the film was adapted from a 1975 all-black cast Broadway musical. At about ten years old, I discovered—what to me felt like a rip-off of The Wiz—Judy Garland's rendition of Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939). When my mother revealed that both films were derived from Frank L. Baum's beloved children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), I was incredulous that Dorothy could be anything other than a black girl. Yet, I also felt a sense of pride that some artist had thought to create a heroine for me and other black girls to emulate. However, it was not until I reached late adolescence, when I began to resist heteronormative ways of viewing the world, that I fully appreciated Dorothy's plight. At the beginning of The Wiz, Aunt Em presents Dorothy with a potential suiter named Gil in the hope that she will marry him and bear children of her own. Before Aunt Em's matchmaking plans come to fruition, Dorothy creates an alternative world (i.e., Oz) to escape these familial pressures. Reading against what the feminist scholar Jill Dolan describes as “the grain of stereotypes” and “manipulation of both the performance text and the cultural text that it helps to shape,” I interpreted Dorothy's behavior as transgressive.Footnote 1 I found Dorothy's refusal to conform to heteronormativity refreshing and delighted in her ability to construct alternative visions of black womanhood with queer possibilities.

With the advantage of hindsight, I now conceptualize my experiences watching The Wiz as that of a “resistant reader.”Footnote 2 By suggesting that queer black feminist spectators might interpret Dorothy's fantasy as a black lesbian narrative, I continue the tradition of “exposing the ways in which dominant ideology is naturalized by the performance's address to the ideal spectator.”Footnote 3 Unfortunately, black women—whether queer or otherwise—rarely make the cut as an “ideal spectator” of popular entertainment. Yet, queer black feminist spectators do exist, and their representation—on the stage, behind the scenes, and in the audience—matters. I therefore situate a queer black feminist as the ideal spectator and offer multiple points of entry into understanding how queer black feminist spectators might engage with The Wiz.

Standing at the crossroads of larger critical debates, The Wiz is uniquely situated to engage with issues of queer black feminist spectatorship, racial authenticity, and politically engaged popular entertainment. For more than forty years The Wiz has enjoyed prestigious awards, commercial success, and cult following among marginalized subcultures. Indeed, many queer blacks—whether from the privacy of their own home or the glamorous world of The Wiz–themed public vogue balls—have embraced the film as exemplary of the queer black experience.Footnote 4 For queer black bloggers such as Kenyon Farrow, The Wiz and its “Black gay anthem … ‘Home’” resonates with those who came of age during the “Classic Era (meaning you're over 30, or at least have Classic Black Gay Sensibilities, or CBGS).”Footnote 5 Farrow writes:

One reason that the Black gays of the classic era love this song, in my opinion, is that it speaks to the pain of feeling cast out of the larger Black community—we have no “home” in a sense. The song is about a stateless person—someone who has dreams of a physical place, but the lesson that they learn is that home has to be made in the family and community we create.Footnote 6

Yet, scholars of both African American theatre and media studies have, for the most part, shied away from exploring how potential queer black audiences might respond to the political relevance and queer black representations in the various productions of The Wiz. This is in part due to the privileging of the heteronormative gaze in reception studies, the unease of positioning an artistically miscegenated work within the canon of African American theatre, and the long-standing binary opposition between popular entertainment and politically engaged theatre.

The few studies that do explore The Wiz focus almost entirely on the 1978 film adaptation and often privilege black cis male subjectivity. The philosopher Tommy J. Curry, for example, analyzes The Wiz’s unsuccessful political campaign as a metaphor for black political marginalization and the Lion's pursuit of courage as a how-to guide for acquiring black masculinity.Footnote 7 The media studies scholar Ryan Bunch interprets Dorothy's journey through Oz as a metaphor for building strong black communities and only briefly acknowledges queer undertones in the black liberation song “Everybody Rejoice (Brand New Day).”Footnote 8 In contrast, the musical-theatre scholar Stacy Wolf celebrates the original Broadway production's social significance, noting that The Wiz depicts a woman as “the leader or initiator of [a] community.”Footnote 9 In so doing, she addresses the importance of spectatorship, writing that “The Wiz motivated the formation and enactment of a community of black theatergoers and critics who defied the hegemony of white critics … and negated the presumption that a white perspective is objective or universal.”Footnote 10 The media studies scholar Rhonda Williams takes Wolf's woman-centered and spectatorship-focused approach a step further by championing black women's spectatorship and the black feminist possibilities of Dorothy's journey. Unfortunately, Williams frames her study within a heteronormative lens.Footnote 11 While important to our understanding of the film's political and social relevance, these readings cannot fully account for intersectionality within the black experience, nor envision queer black feminist spectatorship.

A queer black feminist reading of major productions of The Wiz provides important insights into the curious silence of queer black feminist spectatorship, as well as creates the ontological space for queer black spectators perhaps to identify with and celebrate queer black feminist subjectivity. The performance studies scholar Laura Alexandra Harris locates queer black feminist criticism “at the intersections of pop culture, intellectual culture, and cultures of race, class, and sexuality.”Footnote 12 Queer black feminist praxis illuminates the gaps and silences within queer and feminist histories and theories by reclaiming and writing queer black feminist subjectivity into history.Footnote 13 This essay, therefore, situates The Wiz as a black lesbian fantasy constructed out of the innermost desires of Dorothy, a woman-child, who must come to terms with her own burgeoning sexuality. Dorothy consistently—in all major theatre, film, and television adaptations—creates an Oz brimming with queer black cultural references and visions of queer black womanhood.

Dorothy's fantasy not only renders the queer black body visible within popular culture, but also demonstrates how the cis black female body has been used as a site to reinforce and transgress heteronormativity, sexism, and racism. The original producer Ken Harper conceptualized The Wiz as a transgressive and entertaining production: “The Wiz says this. ‘Alright America, you have this story, it can be told but it is so universal that it can be told with Blacks as well as whites and we're showing it and telling it in a humorous, entertaining and delightful way.’”Footnote 14 By staking a claim to blackness as universal, Harper resists the supposed universality of whiteness and renders Dorothy's black female body a transgressive site of possibilities. In the original 1975 Broadway production, 1978 film adaptation, and 2015 The Wiz Live! televised event, Dorothy must kill Evillene in order to return home. Whether portrayed by actress Mabel King as a dangerous dyke or more recently by Mary J. Blige as camp personified, Evillene disrupts patriarchy, wreaking havoc upon the black community. Though Evillene ultimately dies in all three versions, her dangerous pursuit of power and pleasure transgresses the boundaries of benign black womanhood. The more recent televised adaptation further complicates gender norms through actress Queen Latifah's drag king performance as The Wiz. This contemporary wizard lives their life as a powerful male ruler, yet remains in constant fear that others will discover that they are, in fact, a powerless woman. Evillene and The Wiz's rejection of normativity are but two of many subversive elements within the musical.

By staking a claim to the queerness of this canonical text, I hark back to the film critic Alexander Doty and the queer theatre scholarship of Jill Dolan and Stacy Wolf, whose pioneering efforts helped decenter heterocentrism and sexism within audience reception theories of popular culture. Dolan's The Feminist Spectator as Critic (1988) encourages resistant readership; Wolf's A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical (2002) reveals the implications of signifying “lesbian” on the American musical stage; and Doty's Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon (2000) situates Judy Garland and The Wizard of Oz as significant to the LGBTQ community. Although Doty does not offer criticism of The Wiz, I am drawn to his analysis because of his celebration of queer subjectivity. For example, Doty draws parallels between his own coming out journey and Dorothy's trek through Oz, noting the campiness of the cult classic and taking pleasure in reading the Cowardly Lion as a “drag queen who just didn't give a fuck.”Footnote 15 Doty situates the film as “lesbian narrative” constructed from Dorothy's own queer adolescent fantasies, which culminate in her rendition of “Over the Rainbow,” a “Queer National Anthem.”Footnote 16 By reclaiming this canonical film, Doty disrupts the supposed universality of heterosexism within audience reception studies of popular culture.

While the present analysis owes a debt to Doty's work, my study also departs by simultaneously engaging with race, class, gender, and sexuality within audience reception theories. This reading not only reclaims queer black feminist subjectivity and queer black imagery and culture, but also celebrates the pleasure queer black feminist spectators might experience from the critical moments wherein heterocentrism, sexism, and white cultural hegemony are (intentionally or not) subverted. This pleasure—whether derived from the black lesbian narrative, the use of subversive song, a pulsing disco beat, stylized vogue movements, the black tradition of signifyin’, or a camp sensibility—helps to explain why The Wiz has achieved both mainstream success and a cult following among queer black spectators.

Casting “Black” Art on Broadway

The Wiz premiered during the Black Arts movement (1965–76), a time of black cultural flowering and civil unrest. Race riots swept the nation, as African Americans and their allies protested police brutality, the assassination of black leaders, and the failure of the Civil Rights Act (1964) in instituting civil liberties. Unemployment, drug addiction, prostitution, inadequate housing, and underfunded public-school systems continued to threaten the fabric of many black communities. Black artists responded to these social ills, as well as to their own absence from Broadway stages, by turning inward, creating new works for black audiences.Footnote 17 While the plays of this era vary in tone and style, they often depict a didactic conversion process whereby black audiences could witness a black protagonist's journey from a “Negro” (i.e., passive or politically uninformed) to a “Black” (i.e., politically active). For example, we see this most explicitly in works such as Amiri Baraka's Madheart (1971) and Martie Evans-Charles's Where We At? (1971). Both one-act plays feature black characters who are figuratively and literally “lost,” meaning that they are ignorant of their cultural heritage, have internalized racist beliefs about blacks, or are unmoved by the suffering of the black community. These lost souls must rely on a black revolutionary guide to help them return to the black community and realize their potential as strong black leaders.Footnote 18 Plays such as Madheart and Where We At? exemplify how prescribing and policing the boundaries of blackness were a constant source of artistic and political tension in the 1970s (as today). Unfortunately, these often narrowly defined conceptions of blackness largely excluded the most vulnerable within an already marginalized community: queer black women.

The Wiz, with its all-black cast and mostly black creative team, sits uncomfortably within the ethos of the Black Arts era. Hearkening back to W. E. B. Du Bois's 1926 call for a new black theatre that would meet the needs of black America, revolutionary artists of the sixties and seventies attempted to create black theatre that was by, for, about, and near the black masses.Footnote 19 Harper's decision not to produce the musical at a historically black theatre could potentially have alienated black audiences, many of whom did not live near the Majestic Theatre, a Broadway house located in midtown Manhattan. Yet, the 1975 production included the talents of black performers Stephanie Mills (Dorothy), Tiger Haynes (Tinman), Hinton Battle (Scarecrow), Ted Ross (Lion), André De Shields (The Wiz), Mabel King (Evillene), and Dee Dee Bridgewater (Glinda). Behind the scenes, black artists Charlie Smalls (music and lyrics), George Faison (choreography), Tom H. John (set design), Tharon Musser (lighting), Geoffrey Holder (director and costumes), and Gilbert Moses (original director) worked with white book writer William F. Brown to realize Harper's vision. Harper's decision to hire Brown, rather than use the talents of a black playwright, also stood in direct conflict with the Black Arts ethos of creating black art for the black masses. The question of audience continued to plague Harper, as “many potential backers doubted that theatregoers would accept the ‘Blackening’ of a work so dear to White America.”Footnote 20 The implications were that (1) whites had staked a claim to Frank L. Baum's beloved children's classic, (2) the Broadway production would privilege white spectators, and (3) a black-centered narrative of Oz would alienate white audiences.

Situating The Wiz within the black theatre canon engages with larger critical debates about what constitutes black theatre. Does black theatre only include works written by blacks and performed for black audiences? Footnote 21 If so, The Wiz does not qualify. Yet, The Wiz created greater visibility of black talent and widely appealed to black audiences. Despite Broadway's exclusionary practices, the expense of a $30 Broadway ticket (about $142 with current inflation), and the theatre's geographic distance from de facto segregated black communities, the production was supported by black audiences during weekend matinees.Footnote 22 The theatre critic Judith Cummings credits this high attendance to “word of mouth within the black community,” who believed the show “offer[ed] them something to identify with.”Footnote 23 Queen Latifah admits to being inspired to pursue a career in entertainment after witnessing Mills (Dorothy) sing “Home” as a child: “It's one of the first plays I'd ever seen…. To see people who looked like me and had my color skin, my body type. People who looked like my aunts and my uncles and people I knew—black people. I had never seen anything like it.”Footnote 24 Perhaps she too connected with Dorothy's queer black fantasy of acceptance from the black community?

In addition to affirming the skill of black artists, the Broadway production also entertained black audiences through the use of culturally specific humor, slang, dance, and music (i.e., a mixture of gospel, rock, soul, pop, and protest songs). Black audiences, according to the black theatre critic Bryant Rollins, experienced pleasure through the production's subversion of cultural white hegemony: “Blacks responded in a special way at certain dramatic points in the show, and to some of its songs and dances…. Black theatergoers, especially, seem to appreciate the irony of hearing explicit protest songs right on the Great White Way.”Footnote 25 Though the show's book was written by a white writer, the production modes—orchestrated by a team of talented black artists and performers—demonstrated the possibility of popular culture rising to the level of political importance. Yet, one must not forget that the production—to channel Du Bois—was not exclusively created by black artists, for black audiences, or near black communities. The Wiz also needed to appeal primarily to white audiences, who made up the majority of spectators who attended non-weekend matinees: Harper needed to ensure the financial marketability of his venture, and this meant carefully packaging his “black vision” for racially mixed audiences.Footnote 26

To secure a return for his investors, it was essential that Harper market a codified blackness that would appeal to white consumers. After years of careful maneuvering, Harper finally persuaded Twentieth Century–Fox to invest $1.2 million in the Broadway production.Footnote 27 Unfortunately, racial biases remained embedded in the quest for profit. The song lyrics walk a fine line between catering to the sensibilities of white and black audiences by, for example, using symbols and metaphors that reference slavery, emancipation, the Great Migration (1916–70), the dangers of urban living, domestic servitude, the black church, and law enforcement's untenable relationship to the black community.Footnote 28 Yet, within the safety of a child's fantasy and from within the modes of production, these references could go unnoticed to audiences unfamiliar with these historical and cultural references. The use of vibrant, futuristic sets and costumes helped disconnect the day-to-day struggles of the average black American from this fantastic world. An all-black cast further obscured the impact of institutional white racism, instead highlighting intracultural conflict. Thus, while the book itself alludes to black political struggle, the modes of production also establish The Wiz as a consumable product for a broad (meaning white) audience. Playing to sold-out houses and grossing $18.5 million in ticket sales, The Wiz culminated in seven Tony Awards, including Best Musical.Footnote 29

The Wiz’s critical and financial success demonstrated the viability of black theatre and subverted (albeit, briefly) the racial barriers of the Great White Way. For this to happen, Harper had to convince the white businessmen of Twentieth Century–Fox that white audiences would attend an all-black Broadway musical. There were, of course, a number of precursors to the all-black Broadway musical, including Bob Cole and Billy Johnson's A Trip to Coontown (1898) and Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake's Shuffle Along (1921), which “legitimized the black musical [and] proved to producers and theatre managers that [white] audiences would pay to see black talent on Broadway.”Footnote 30 Yet, by the 1970s, Harper's insistence on producing an all-black musical was considered controversial, in part because of his race. Black producers encountered “charges of racism” for supporting all-black musicals, whereas white producers remained virtually unchallenged for continuing the practice of all-white casts.Footnote 31 New York Times critic Mel Gussow exemplifies this double standard in his article “Casting by Race Can Be Touchy” (1975):

The crucial question is whether a play should be cast entirely with black performers or with a mixed company. The former can seem racist if there is no artistic validity for the switch in color. Then its only justification is to give minority actors employment. The mixed company makes far more sense.Footnote 32

While well-intended, arguing for an interracial cast simply ignores the underlying issue of systemic racism within the arts and society as a whole.Footnote 33

The fact remains that Broadway directors, producers, designers, playwrights, and performers remain predominately white. The problem is so pervasive that in 2011, when the works of three black women playwrights—Katori Hall, Lydia R. Diamond, and Suzan-Lori Parks—were produced on Broadway, their presence became a newsworthy headline. Kenny Leon, director of The Wiz Live!, reflects: “I can't remember the last time there were three women playwrights on Broadway during the same season, let alone three African-American women.”Footnote 34 Furthermore, actors of color deserve more than the occasional nontraditional casting opportunity. Gary Anderson, the artistic director of Plowshares Theatre Company (Detroit), reports:

For every exceptional situation where an artist of color has found work—such as Hamilton—there remains an 8-to-1 advantage white actors have over the random actor of color. Administrators of color who are put into associate or deputy positions below senior management are tasked with masking the reality that American Theatre has become no more progressive on race and inclusion than their fathers and grandfathers…. [T]here seems to be a growing awareness among many sociologists that “colorblindness” of any kind—including color blind casting—does more to entrench racial disadvantage rather than rectify it.Footnote 35

Artists of color need employment opportunities at every level of theatre production. The Wiz showcased the talent of black artists and also brought public scrutiny to these topical issues.

Although I have briefly discussed The Wiz in terms of its cultivation of black talent, popularity with black audiences, and consumption by white spectators, it is also important to consider the play's popularity among subcultures that operate within marginalized cultures. The remainder of the article, therefore, provides a more nuanced reading of spectatorship, privileging the less visible intersections of black identity. I offer my own resistant readership of The Wiz and consider how queer black feminist spectators might derive pleasure from Dorothy's queer black adolescent fantasy, paying particular attention to the critical tension between the book and song lyrics, modes of production, and queer black feminist spectatorship. In so doing, I hope to continue the practice of queering the canon.

Queering the Broadway Canon

Black lesbians—whether playwrights, characters onstage, or spectators—are often rendered invisible within discussions of the Broadway canon and in audience reception theories of popular culture. Invariably, when conversations do arise about the relationship between queer identity and spectatorship, “queer” often becomes synonymous for gay men, and “lesbian” does not reach beyond the borders of white women. The scholar of queer musical theatre David Savran writes that “musical theater, in particular, has in popular mythology been adjudged a sacred preserve of gay men, who have been among its most important producers.”Footnote 36 Such mythology situates gay white men as musical theatre's “most visible devotees.”Footnote 37 In reality, black lesbians have also contributed profoundly to the creation and dissemination of musical performance. Stacy Wolf, for example, acknowledges the influence early black women blues singers—many of whom identified as or were rumored to be lesbians—had on writers during the Golden Age of musical theatre: “The strength, singularity, and passionate expressiveness of the Broadway musical's female star are reminiscent of women blues singers; these qualities are not found elsewhere in mid-twentieth-century American culture.”Footnote 38 While we understand that musicals have “long offered personal, emotional, and cultural validation for gay men,” we have yet to fully appreciate the ways in which musicals have afforded queer black feminist spectators, as the blueswomen before them, opportunities to maintain or challenge the status quo.Footnote 39 Analyzing Dorothy's plight from the perspective of queer black feminist spectators offers one possible point of entry.

If Oz is a product of Dorothy's queer black adolescent fantasy, just what is she attempting to escape? The Broadway book describes Dorothy as “a girl of thirteen or fourteen” who is “as bright and alive as can be.”Footnote 40 Conflict arises as she uses her agency to daydream of a different life, rather than perform domestic tasks such as helping Aunt Em with laundry. Daydreaming allows her to escape, albeit briefly, the drudgeries of life on a “ramshackle little farm house in Kansas” (9). The book states that “somehow, it would seem she's built a life of her own on this dreary farm, and would probably rather remain a child as long as possible instead of accepting the responsibilities of adulthood” (9). As heterosexual kinfolk with clearly delineated gender roles, her family assumes that she will follow in Aunt Em's footsteps and tend to the home. Dorothy copes with the pressure to conform to gendered and sexual norms by creating an interior life and disavowing the physical growth Aunt Em refers to in her song, “The Feeling We Once Had,” by literally turning away from her (11). Dorothy is not alone in this journey, as many queer black youth tend to live in heterosexual families, are isolated from their peers, and “do not even recognize this [queer] part of their identity until adolescence.”Footnote 41 Feelings of isolation, coupled with the burden of conforming, become manifest in a “Tornado Ballet,” taking Dorothy to a new world of queer black possibilities.

Dorothy's journey through Oz serves as a metaphor for her path to queer black womanhood. Will she continue to repress her desires, or will she find the strength to embrace her queer identity and gain acceptance from the black community? Unable to cope with this internal battle in everyday life, she imagines multiple visions of what black womanhood might look like for her. Queer black feminist spectators are left to wonder which path Dorothy will follow. Will Dorothy emulate the black churchwomen and wait for a black man to “save” her from her own queer desires? Or, will Dorothy suppress her feelings and become Glinda, a surrogate mother figure to the black community? Even still, will she choose a more dangerous path and abandon the black community altogether in pursuit of her own power, like the Wicked Witch of the West? Finally, will Dorothy decide to discard her inhibitions and embrace an isolated life of queer dance culture behind the gates of Emerald City?

The churchwomen of Oz represent the important role the black church has played in shaping queer black experiences in the United States. The sociologist Patricia Hill Collins notes that during the turn of the twentieth century, “the majority of LGBT Black people … remain[ed] deeply closeted” in rural areas of the South.Footnote 42 Already marginalized within society because of their race, many queer blacks, fearing further abuse, felt pressed to pass as heterosexual.Footnote 43 As the twentieth century dawned, black religious and political leaders promoted a politics of respectability as a weapon to combat institutional racism. Black homosexuality was viewed by churchgoing folks not only as morally repugnant, but also as a threat to the black family structure and the black political struggle.Footnote 44 At the heart of this homophobic rhetoric rests a concern about the supposed weakened state of queer black men and their inability to fulfill their role as provider, protector, and leader of the black community. (It is within the more conservative black church's view that women should head neither the family nor the liberation movement; black lesbians do not factor into such discussions.) Black homosexuality is therefore seen by many churchgoing blacks as an enemy to black liberation, perhaps even reflecting “a sinister plot by White racists as a form of population genocide (neither gay Black men nor Black lesbians have children under this scenario).”Footnote 45 Pressured by the black church to adhere to the politics of respectability—which supports dominant ideologies of gender and sexuality—queer blacks often self-censor by remaining in the closet to support and protect the black community.

The churchwomen of Oz adopt a similar politics of respectability by situating Evillene as the embodiment of pure evil. Similar to the black women's club movement at the turn of the twentieth century, the black women of Oz organize a religious society to aid their community. The Wiz explains that the churchwomen promote benefits and insist that he perform another miracle when he is mistakenly identified as a pastor of sorts. The churchwomen turn to the Wiz for leadership and protection against Evillene, whom he describes as “the most evil … the most wicked … the most powerful of all the witches in Oz” (53). It is important to note that the Wiz has never actually met Evillene and that his description presumably comes from the churchwomen's previous encounters with her. Now, what makes Evillene evil, wicked, and powerful? She is physically unattractive, flourishes without the companionship of a black man, and aligns herself with feminism and capitalism. In other words, she embodies the attributes of what I term the dangerous dyke. While she perceives herself as beautiful and powerful, the black community finds her queer body repulsive and her power dangerous.

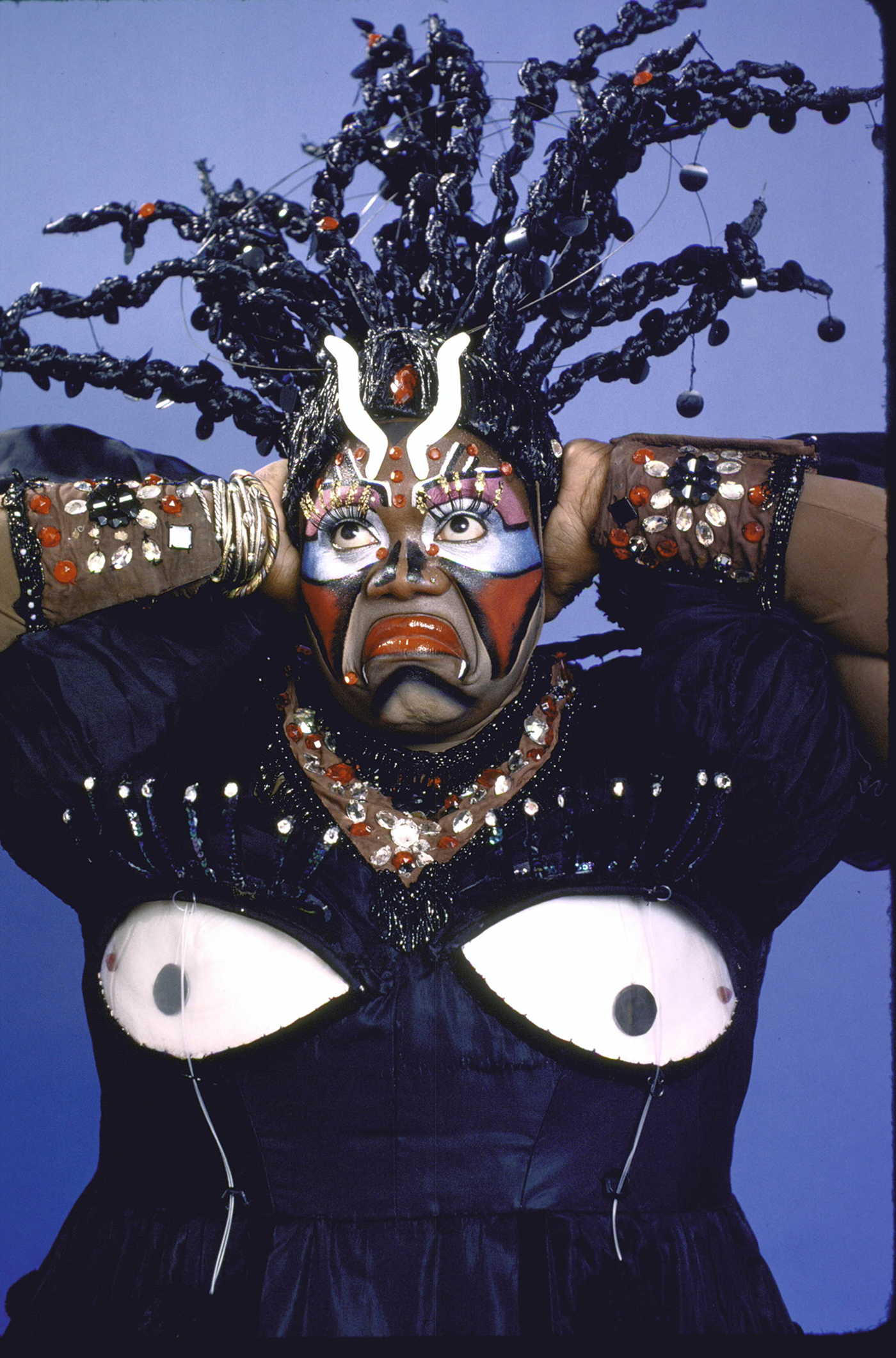

As a dangerous dyke, Evillene represents a heterosexist view of queer black womanhood. Described in the book as lacking “a kind bone in her imposing body or a good thought in her rotten mind,” Evillene surrounds herself with “slave-like” Winkies who labor in her factory (55). Performed by actress Mabel King in both the original Broadway and film version of the musical, the character situates herself as the epitome of black beauty. Yet, for some audiences, her appearance might reflect a conglomeration of controlling images of black womanhood. Onstage Evillene appears as a large, animalistic, domineering black matriarch. She sports small, sharklike teeth; grotesque red, black, and silver makeup; an oversized black wig that resembles a fruit tree; an excessive amount of jewelry; and a long black dress with large movable eyes at her chest (Fig. 1). As master of her own castle, Evillene rests on a throne made of carcasses and intimidates any man who undermines her authority. For example, when the leader of the Winged Monkeys questions her decision, she threatens to put a spell on his “coconuts,” and he quickly defers to her judgment (60). She also displays her contempt for black male agency by ordering (the once-powerful) Lord High Underling to speak to her only while on his knees. Obeying, he immediately “drops to his knees, groveling” (57). She then makes him kiss her foul-smelling boot and declares: “It's so good to be a liberated woman” (57). While Lord High Underling's response to her body odor is likely meant to elicit laughter from audiences, her statement, coupled with her appearance and masculine behavior also provides a warning against the dangers of feminism. Evillene, after all, associates black women's liberation with the emasculation of black men.

Figure 1. Actress Ella Mitchell (Evillene) in a publicity shot for the replacement cast (1977) of the 1975 Broadway musical The Wiz (New York). Photo: Martha Swope, © Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Queer black feminist spectators, however, can use their agency to challenge interpretations of Evillene as a heterosexist nightmare and instead read her as an image of queer black feminist strength whose “fatal flaw” is her inability to work with the black community of Oz. Evillene's plight parallels the actual concerns that many black lesbians encounter in everyday life. In her study of motherhood and gay identities, the sociologist Mignon R. Moore found that black lesbians “live in black communities, not ‘gay ghettos,’ and that social location shapes their identities, family formation, and other understandings in ways that differ from some white LGBT people.”Footnote 46 Indeed, finding a way to express one's sexual agency and remain within the black community is an ever-present tension within black lesbian identity formation. Evillene's betrayal of her own community perhaps serves as an example of what to avoid. In contrast to the other witches and churchwomen of Oz, Evillene achieves power and financial independence to the detriment of others. Her source of power lies with her mind and body as she uses her business savvy and knowledge of voodoo to maintain order. For example, when the groveling Messenger tries to escape her wrath, she performs a voodoo chant using the movable eyes at her chest to force him to crawl back to her (59). Dorothy and the other witches of Oz are likewise strong and decidedly queer, but unlike Evillene they use their power to protect and uplift the black community. Evillene, however, uses her strength solely for her own empowerment, leaving her ostracized from the black community.

In contrast to Evillene, the churchwomen turn to a male spokesman for protection. Though the Wiz describes the churchwomen as assertive and capable of leading, they ultimately turn to a pastor of sorts for direction. The Wiz, who desperately craves social mobility, explains to Dorothy that, before landing in Oz, he sold used cars, worked as “a pitchman in a carnival,” and “even peddled bleaching creams from door to door” in Omaha (73). He insists that God called him to “spread the Good Word” (i.e., host a revival meeting) so that he could acquire “the simple things in life … power … prestige … and money” (73). Before he could make his grand entrance inside a hot-air balloon, a “violent wind” tossed him in the middle of a ladies’ social in Oz (73). “They thought a miracle had delivered me to them,” says the Wiz. “And before you could say ‘wizard’ … they promoted me all over town, and sold tickets for a benefit, at which they said I was going to perform another miracle…. Naturally, I did!” (74). Unfortunately, the churchwomen put their faith in an individualistic man who sees spirituality as nothing more than a used car: a commodity to be sold. Furthermore, his open admission to manipulating black women's faith and beauty for personal gain suggests a severe moral deficiency and cements him as an enemy to the black liberation struggle.

Ultimately, it is not the Wiz's “miracles” but Dorothy's strength that liberates the churchwomen. Their inability to understand their strength as black women allowed them to be controlled by the Wiz. Black queer feminist spectators might read the churchwomen's reliance on the flawed teachings of a male pastor as a very real problem within actual black communities. The black church has historically provided black women with “a place of refuge, of solace and hope” from the horrors of enslavement to the battle for civil rights, with black women making up 70–90 percent of today's black congregations.Footnote 47 Yet, the black church has also been slow to admit women formally into high-ranking positions. Black women continue to find themselves consigned to the margins while black men assume leadership positions.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, these same ministers continue to view homosexuality as “a ‘white disease’” and reaffirm heterosexist ideologies that render queer black women at best invisible or at worst: an enemy to the black community.Footnote 49 Manipulated by the smooth-talking Wiz, Dorothy makes the decision to kill Evillene in exchange for his aid in returning home.

However, by killing Evillene, Dorothy runs the risk of silencing her innermost desires. Evillene, after all, is created from Dorothy's own queer subconscious and embodies her own feminine strength. Dorothy perhaps best exemplifies this attribute through her interactions with Lion. When she first meets Lion, he takes pleasure in scaring her friends as he boasts about his masculine strength in the song “Mean Ole Lion.” Dorothy, however, sees through his male bravado. While Tinman and Scarecrow cower in fear, she becomes her own heroine by delivering a roundhouse punch to Lion, followed by a sound spanking for upsetting her friends. Queer black feminist spectators can perhaps derive pleasure from watching Dorothy disrupt gender norms through her skillful defense of her terrified friends.

Unfortunately, queer black feminist spectators may find that the book later undoes this subversive scene by reinforcing the belief that strong black mothers hinder black communities. In a moment of contriteness Lion reveals why he behaves like a hypermasculine hero from a Blaxploitation film: “Daddy left home when I was born, and Momma was such a strong lady. It was either ‘do this’ or ‘don't do that’ … ‘you call them paws clean?’ … ‘Lick behind your ears, child, or you don't get no dessert’” (34). The juxtaposition of his affected machismo and actual ineptness is meant to illicit laughter. Yet, using a strong-tongued single mother as a scapegoat for black men's personal failings is no laughing matter. By blaming his broken home on his mother's strength, Lion reinforces both superwoman and black matriarchy mythology.Footnote 50 Early black feminists such as Michele Wallace worked tirelessly to disrupt these mythologies, as well as the correlation of black liberation with the acquisition of manhood.Footnote 51 Unfortunately, using single black mothers as scapegoats for the ills of the black community is nothing new. From The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (1965), to welfare reform debates of the 1990s, to today's myth of the “missing black father,” single black mothers continue to encounter stigmatization within US politics and greater society.Footnote 52 The Wiz reinforces these dangerous mythologies by making it clear that, in order to liberate herself, friends, and Winkies, Dorothy must kill Evillene. This she does by tossing a bucket of water on her; but when exorcizing Evillene from the black community does not immediately allow Dorothy to return home, she turns to Glinda, the Good Witch of the South, for advice.

Glinda embodies attributes of the blueswoman figure and, as such, represents a more viable vision of queer black womanhood for Dorothy to follow. Glinda, described in the book as “the prettiest of all the Witches,” appears at Dorothy's most desperate moment (86). Dorothy has won the Wiz's favor by killing Evillene only to experience abandonment by his abrupt departure in a hot-air balloon. He does, however, counsel Dorothy and the citizens of Oz to “stop … holding on to the things that make us feel safe! […] And embrace what we fear” (81): sound advice for those who fear their sexuality might lead to ostracism from their community; yet, difficult to execute for those who lack confidence in themselves. As a seasoned performer in the land of Oz, Glinda uses the power of her voice to help restore Dorothy's confidence. Much like the classic blueswomen of the 1920s who advised women listeners through themes of “abandonment … returning to family … homosexuality … traveling,”Footnote 53 Glinda offers guidance through song. This is perhaps best exemplified through her musical number, “A Rested Body Is a Rested Mind.” Glinda sings, “Oh, the journey that you had to make/I've watched you bear the load/But you can always stay at my place/When you come off the road” (86). With these words Glinda conjures the spirit of Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, the “Mother of the Blues,” who also privileged black women's subjectivity and openly discussed her women lovers in her songs. The black feminist activist Angela Davis writes that Rainey's songs about black women's travels to and from home “are frequently associated with the exercise of autonomy in their sexual lives.”Footnote 54 These poor black women “travel because they have lovers in other cities, or because they wish to find new lovers.”Footnote 55 Glinda's song likewise validates Dorothy's freedom to explore her sexuality and maintain acceptance from the black community.

In contrast to Evillene, Glinda has negotiated a space for her queer black womanhood within the black community. While technically a witch, Glinda uses her crystal ball to bear witness to the plight of her community. She serves as a cultural healer, using performance to unify and strengthen Oz from divisive forces. It is not the community-minded Glinda, after all, whom the churchwomen join forces to defeat. Glinda shares her wisdom with Dorothy in her reprise of The Wiz's song “Believe in Yourself.” Glinda sings, “believe in yourself, right from the start/Believe in the magic that's inside your heart/Believe what you see/Not what life told you to” (88). Glinda understands that Dorothy's life experiences have taught her to doubt her strength and question her heart's desires. Black women are often socialized from an early age to believe that they are somehow inferior, or that having queer desires makes them undeserving of protection from the black community. Glinda, however, validates the “magic” of queer black womanhood and invites Dorothy to reach a new understanding of her worth and role within the black community. Dorothy now has the choice either to follow Glinda's footsteps by taking on the difficult task of unifying the black community, or to devote her energies to pursuing unbridled pleasure on the dance floor behind the gates of the Emerald City.

For queer black feminist spectators, Emerald City might symbolize the hidden world of queer black nightlife in New York City. The book describes Emerald City as gloriously “futuristic,” replete with “Beautiful People, [who are] very much aware of it, and as such, are haughty and proud” (44). The gate protects the “exquisitely and exotically dressed” citizens from society's censor, allowing them to form their own community based upon their love of dance. To gain entrance into this exclusive world, Dorothy and her friends must first win the approval of the Royal Gatekeeper. Unfortunately, the Royal Gatekeeper perceives them as “trash” and allows them to enter the “Big Green Apple” only under threat of bodily harm (i.e., Tinman swings an axe at him; 43–4). The Royal Gatekeeper immediately regrets his decision, for once the friends enter Emerald City he declares: “Well, there goes the neighborhood” (44). While this exchange satirizes racist housing covenants that denied blacks entry into select white neighborhoods, this moment also mirrors the racist and sexist practices that occurred within the disco nightlife of New York City.Footnote 56 Originally a subversive social dance, disco allowed queer dancers in the early 1970s to circumvent New York State law, which forbid male–male dancing.Footnote 57 The cultural historian Tim Lawrence reminds us, however, that by the late seventies, disco spaces were co-opted by party organizers who formed groups based on restrictive concepts of identity. “De facto white-only male gay venues” secured the “self-anointed ‘A-list’ crowd,” leaving lesbians and minorities mostly excluded from elite New York dance culture.Footnote 58 Queer black feminist spectators familiar with queer New York nightlife might experience a moment of joy when witnessing Dorothy and her friends resist these exclusionary practices and secure their right to enter Emerald City.

At the conclusion of her journey, Dorothy must make an important decision that will determine her future. Will she repress, embrace, or negotiate her queer identity? The iconic song “Home” provides clues to Dorothy's choice. Toward the end of the song Dorothy pleads with God: “Please, don't make it hard/To know if we should believe the things we see/Tell us, should we try to stay/Or should we run away/Or is it better just to let things be?” (90). Dorothy understands that no matter which path she takes, she will encounter difficulty. Young black girls of this time (and arguably still today) encountered a barrage of images that did not reflect their reality. Representations of black women as hypersexual jezebels, asexual mammies, angry bitches, or emasculating matriarchs were pervasive within US popular culture. Yet, images of queer black womanhood were rare. Gross misrepresentations and invisibility within society are equally damaging. Dorothy's song invites spectators also to question what “we” see and to choose either to “stay” who they are, run away from their troubles, or continue to submit passively to society's pressures. Dorothy ultimately decides to embrace her queer fantasy as “real,” or as a part of her identity, and returns home with a newfound love for herself and community (90).

Motown's Queer Spectacle: The Wiz Moves to Film

Despite a profitable and critically acclaimed run on Broadway, a series of artistic compromises were made to ensure the production's successful transition into film. To begin, the 1978 film adaptation was produced during the height of the Blaxploitation era of filmmaking. By this point, major Hollywood production companies had taken notice of the financial success of small, independent black film companies and marketed black-themed films to their newly identified “Black audience.”Footnote 59 Berry Gordy's Motown Productions, the film and television branch of the Motown Records label, readily seized the opportunity to profit from this trend by producing a black-themed film that had already proved popular with black and white audiences. Motown Productions acquired the rights to produce the film but replaced most of the original black creative team with commercially successful white filmmakers. Executive producers Ken Harper and Gordy headed this new creative team comprised of Hollywood producer Rob Cohen (who'd worked with Gordy and Diana Ross before), director Sidney Lumet, screenwriter Joel Schumacher (of the multiracial comedy-with-music Car Wash [1976]), and black composer-arranger Quincy Jones.

The new production team's major visual and aural changes included a revised book and additional songs that catered to the strengths of their all-star cast, including Motown royalty. These changes allowed living legend Lena Horne to dazzle spectators with her divalike persona as Glinda; Motown veteran and superstar Michael Jackson (Scarecrow) to shine in the added song, “You Can't Win”; comedian Richard Pryor to perform as a nonsinging Wiz; and entertainer Julius “Nipsey” Russell (Tinman) to provide additional lighthearted humor to the story. The music-driven film also provided the perfect platform to transition Motown darling and gay icon Diana Ross into serious acting. Prior to The Wiz, Ross had only made brief cameos on television, performed An Evening with Diana Ross (1976) on Broadway, and starred in Gordy's film Mahogany (1975). Universal Pictures, however, was willing to support the film (to the tune of $1 million) if Ross starred as Dorothy in the film.Footnote 60 Gordy eventually conceded, and Schumacher changed the screenplay accordingly. Now a thirty-three-year-old Ross would perform as a timid twenty-four-year-old schoolteacher who refuses to travel beyond the bounds of her Harlem neighborhood. In a surprising move, the megastar (known for her glamorous wigs and diva persona), abandoned her affected look to play the role. Ross appears “natural” in the film, sporting a short afro, light makeup, conservative lavender top, and white pleated skirt. Only two original cast members reprised their roles: Mabel King (Evillene) and Ted Ross (Lion).

In keeping with their parent company, Motown Productions omitted the more overtly political messages within the original Broadway production to appeal to the broadest possible audience. The performance studies scholar Wendy S. Watters contends that “Motown was not committed to delivering a political message,” but instead “celebrated traditional themes in popular music of the time such as: romantic love, dancing, and parties.”Footnote 61 Through his careful engineering of his recording artists’ voices, song lyrics, fashions, and dance moves, Gordy had been able to introduce “a new performance of blackness into mass media.”Footnote 62 The 1978 screenplay follows a similar pattern by excluding any overt reference to black feminism, enhancing the elaborate dance sequences within the world of Oz, and situating the central conflict in terms of Dorothy's inability to secure romantic love. These alterations invited spectators—black, white, queer, or otherwise—to consume this new vision of blackness.

Years after the release of the film, members of the original creative team have expressed their displeasure with the changes made in the film adaptation. For example, in a 1993 interview book writer William F. Brown and choreographer George Faison described the film as “awful” and “dreadful,” respectively.Footnote 63 Brown, in particular, expressed displeasure with Hollywood producers restoring Scarecrow's “You Can't Win” to the narrative. “The movie had a song that was dropped from the [Broadway] show. It went, ‘You can't win / You get even,’ and that was considered a black message song. But it's all changed. Black people can win,” stated Brown.Footnote 64 Since Motown eschewed (for the most part) political messages within its songs, one is left to speculate that this song was more likely added to highlight the talents of Michael Jackson than to deliver a “black message song” to audiences.

Despite their attempts to appeal to popular tastes, Universal Pictures and Motown Productions did not receive a complete return of their nearly $30-million investment. Many critics panned the screenplay and Ross's acting abilities. Yet, the production also received critical acclaim, garnering four Academy Award nominations for costume design (Tony Walton), cinematography (Oswald Morris), production design (Tony Walton and Philip Rosenberg), and music (Quincy Jones).Footnote 65 The adaptation has also enjoyed a strong following among marginalized subcultures. This is perhaps, in part, due to the resistant readership of queer black feminist spectators. Thus, despite the limitations of the screenplay, queer black feminist spectators have the capacity to identify queer black cultural references—whether through Ross's portrayal of Dorothy, the use of disco within Emerald City, or Lena Horne's camp performance as Glinda.

Ross's Dorothy reflects a queer black feminist sensibility through her eschewal of a heterosexual union. Well beyond her adolescence, Dorothy faces the more immediate pressure of conforming to her community's dictates of black womanhood or risking a fate worse than death: spinsterhood. These pressures are perhaps best exemplified in the opening sequence of the film, when Aunt Em summons Dorothy from the kitchen to meet Gil, the well-dressed son of her friend. After introductions are made Dorothy takes Gil's coat and quickly exits, leaving him standing with a look of dejection on his face. Clearly, this meeting was no choice encounter, but a carefully arranged meeting concocted by Aunt Em. Despite Dorothy's evasive actions, Aunt Em continues her matchmaking, explaining: “Don't worry Gil, she's just a little shy.”Footnote 66 It becomes clear in the next scene that by refusing Gil's amorous attentions, Dorothy may also surrender her chances of motherhood. As the entire family surrounds the newest arrivals—a young woman, man, and infant—Dorothy stands by herself several feet away, staring longingly at the mother and baby. Dorothy's innermost desire is motherhood and not a relationship with a man. Yet, is it possible for her to have one without the other? Dorothy's trip through Oz provides the answer she so desperately seeks.

A queer black feminist interpretation of this moment could suggest that Dorothy's ability to embrace both motherhood and a queer black feminist identity allows her to empower the black community of Oz. She mothers Lion, Scarecrow, and Tinman throughout the film: protecting them from Evillene's wrath, the hallucinogenic charm of the Poppies, and The Wiz's bullying. She encourages them during their weakest moments, helping them obtain their dreams of courage, a brain, and a heart, respectively. She also works collectively with black men. For example, she and Scarecrow help Tinman escape a mammy figure who has literally crushed him (Fig. 2). Liberating Tinman from the weight of stereotypes and encouraging him to free his mind from self-loathing allows him to “ease on down the road” to empowerment. Her newfound strength culminates in the soulful song “Home,” which has been regarded in heteronormative spaces as “an anthem of self-determination.”Footnote 67 As Ross stares directly into the camera, she testifies to viewers, singing: “And I learned that we must look/Inside our hearts to find/A world full of love/Like yours, like mine/Like home.” Using the collective “we,” Ross invites audiences to join her in building strong black communities filled with love. In so doing, Ross/Dorothy becomes a “Black feminist model” embodying “the appropriate and necessary behavior that all of the Black, female moviegoers should emulate with the Black men in their lives,” writes scholar Rhonda Williams.Footnote 68 Yet, Dorothy also provides an image of queer black motherhood and models how to have productive (nonsexual) relationships with black men. Through her efforts to establish community, Dorothy becomes a leader in her own right, perhaps encouraging queer black feminist spectators to do the same.

Figure 2. Diana Ross (Dorothy) and Michael Jackson (Scarecrow) discover Nipsey Russell (Tinman) hidden beneath the weight of a mammy figure. Screenshot of Universal Picture's The Wiz (1978), courtesy of the author.

Queer black feminist spectators might also derive pleasure by identifying the film adaptation's use of queer black culture references, namely the celebration of disco. From the cotton fields to drag balls of the Harlem Renaissance, social dance has provided blacks the opportunity to commune with one another and take part in “expressive release” from day to day concerns.Footnote 69 The emergence of disco following the Stonewall Rebellion (1969) provided yet another space to express queer black possibilities. Merging elements of soul, funk, gospel, and R&B music into a “queer aesthetic,” disco music allowed dancers to experience “an affective and social experience of the body that exceeded normative conceptions of straight and gay sexuality.”Footnote 70 The Emerald City citizens embrace these queer possibilities, creating a vibrant disco nightlife that privileges a glamorous black LGBTQ community. The citizens wear couture clothing and strike poses to a disco beat in a Vogue-like photo shoot while a human-sized camera records their efforts. However, in contrast to disco music of the time, the dancers are not guided by the voice of black female divas such as Gloria Gaynor or Donna Summer. Rather, The Wiz serves as M.C. and encourages the dancers to focus on beauty and fashion. It is Dorothy, after all, who creates this queer black disco fantasy from her imagination. As such, it is Dorothy (and by extension, the viewer) who discovers pleasure and belonging within the gates of Emerald City.

While the screenplay does not allow Dorothy to create a black female diva figure within her queer black disco fantasy sequence, the spectator can still derive pleasure from witnessing Lena Horne's camp performance as the mother of all divas. By camp, I refer to filmmaker and activist Susan Sontag's conceptualization that “the essence of Camp [is a] love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.”Footnote 71 This sensibility, which is most often associated with gay male subculture, is not something that is universally shared or appreciated. Camp is a subjective, often solitary experience whereby spectators take pleasure in androgyny, outrageous spectacle, and “convert[ing] the serious into the frivolous.”Footnote 72 While seemingly unintentional, Horne's performance embodies many elements of camp. She first appears as a godlike black femme mother sporting an extravagant diamond-encrusted ball gown, bedazzled headpiece, and diamond earrings. The night sky, artificial snowflakes, and a dozen black babies suspended in midair surround her as she makes a grand entrance. She demonstrates her supernatural power by using her breath to create a “snow tornado” to carry Dorothy into Oz. In her second and final scene, Horne again appears suspended in midair against the artificial snow-covered heavens. She advises Dorothy to remember that, “Home is knowing … knowing your mind, knowing your heart, knowing your courage” before delivering an affected gospellike rendition of “Believe.” Horne's earnest performance as Glinda appears unnatural, replete with exaggerated facial expressions, one-dimensional characterizations, and awkward arm movements during the spirited gospel number “Believe.” While encouraging self-knowledge, celebrating black motherhood, and empowering queer black women is no laughing matter, the modes of production produce an extravagant spectacle ripe for camp enthusiasts.

Acknowledging the camp sensibilities of queer black feminist spectators furthers the efforts of feminist film critics to decentralize camp spectatorship from white urban gay male subjectivity. As media studies scholar Pamela Robertson persuasively argues, camp is both performed by and experienced by lesbians and heterosexual women who use their agency to “appropriate aspects of gay male culture” and “knowingly produce themselves as camp.”Footnote 73 Queer black feminists can and do experience the pleasure of camp performance as both spectators and subjects of camp.

The Wiz Goes Live in a “Postracial” Society

Similar to the original Broadway production, The Wiz Live! was produced during an era of social injustice and civil unrest. While black Americans and their allies have protested racially motivated crimes against blacks throughout history, the dawn of social media has helped make these concerns more immediate, visible, and potent. Social networking has provided a platform for activists to share news and strategize ways to address the alarming rates of unarmed blacks being killed by police.Footnote 74 Yet, even as the Black Lives Matter and Say Her Name movements gained national attention, counternarratives formed to disrupt the momentum. Active and retired law enforcement officers formed Blue Lives Matter to dispute accounts of systemic wrongdoing on the part of police officers, and white supremacists formed White Lives Matter supposedly to prevent white genocide.Footnote 75 While The Wiz Live! does not directly address police brutality, white supremacists situated the production within social justice narratives as an example of liberalism gone awry.

Although the vast majority of the Twitter community praised NBC's decision to produce an all-black musical, more hostile Twitter users condemned the casting practice as “reverse” discrimination or racism. For example, @KoneyDetroit wrote: “@nbc why are there no whites starring in #TheWiz? this is racist! can u imagine if it were the other way? #whitelivesmatter.”Footnote 76 While racially insensitive and wrongheaded, @KoneyDetroit's comment presents a fascinating paradox. By acknowledging racism, the tweet disrupts mythology of a supposedly postracial society. Yet, their willful ignorance of the political and aesthetic context from which The Wiz Live! emerged allows institutional white racism to remain intact. Unfortunately, these more inflammatory tweets were then circulated by media outlets, including The View, which aired a “Hot Topic” segment on the production's casting practices. While erroneous, these sensationalized tweets remain important because they helped bring national attention to issues of racial biases within the theatre industry.

The Wiz Live! represents a moment of black cultural trafficking within the white-dominated television industry. Executive producers Craig Zadan and Neil Meron (both white and openly gay) decided to mount a live televised adaptation of The Wiz in the hopes of improving lackluster ratings for their previous project, Peter Pan Live! (2014). “What we learned is we wanted to do something that was cooler and hipper and contemporary. And something that had a lot of stars,” remembers Zadan.Footnote 77 Greenlit as a live televised event, The Wiz Live! was conceived of and controlled by white executives who marketed the musical to both white and historically marginalized audiences. Appealing to the broadest possible audience meant omitting or whitewashing the more overt symbols and metaphors of black history and culture found within the original book; infusing hip-hop into the land of Oz; and casting popular black entertainers Queen Latifah, Mary J. Blige, Ne-Yo (Tinman), Uzo Aduba (Glinda), Amber Riley (Addaperle), and Common (The Bouncer)—in addition to original The Wiz Dorothy, Stephanie Mills, as Aunt Em. Zadan and Meron also hired the African American Tony Award–winning director Kenny Leon, critically acclaimed African American hip-hop choreographer Fatima Robinson, and openly gay Tony Award–winning actor Harvey Fierstein to realize their vision. While Fierstein initially refused to adapt the book—he was concerned that his Jewish heritage might undermine the cultural legacy of the production for audiences—he readily agreed once he learned that the original book writer was white.Footnote 78 Fierstein's camp aesthetics coupled with Zadan and Meron's hip-hop vision proved successful, with the resulting production garnering 11.5 million television viewers and 6.4 million Twitter views.Footnote 79

Fierstein's adaptation emphasizes the queer black cultural references found within the musical's original book, and the production modes more overtly produce a camp aesthetics. In fact, one might argue that the televised musical is itself a distinct form of camp—intentionally marketed to both mainstream and marginalized audiences. Openly gay writer Rob Smith provides an astute observation of why he and other camp enthusiasts experienced pleasure while watching The Wiz Live! Smith credits gay dancers voguing in the Emerald City, “baby gay icon” Amber Riley's rendition of “He's The Wiz,” Blige's exaggerated bitchiness, and Queen Latifah's drag king performance as being “just subversive enough to fly over the heads of most in middle America.”Footnote 80 This does not mean that viewers unfamiliar with queer cultural references did not enjoy the production's camp aesthetics, nor that all viewers in-the-know experienced pleasure while watching the overtly camp production. After all, “camp is a reading/viewing practice which, by definition, is not available to all readers; for there to be a genuinely camp spectator, there must be another hypothetical spectator who views the object ‘normally,’” writes Pamela Robertson.Footnote 81 As such, spectators experienced pleasure knowing that others “missed” the queer black cultural references embedded in The Wiz Live!

While the TV event's book cannot account for racism in the United States, the modes of production unapologetically celebrate queer black identity and recover queer black and Latinx voguing traditions. Despite popular memory, voguing existed prior to Madonna's popularization of the dance in her 1990 video “Vogue.” The Wiz Live! critiques this historical erasure by transporting Dorothy and friends into the inner sanctuary of a queer black ballroom community. Initially undisturbed by their arrival, the queer citizens chant, “Fierce, slay, serve, beat, twirl” as they Vogue Fem to house music.Footnote 82 Once the citizens notice Dorothy and her friends, they immediately perceive them as house rivals and begin throwing “shade” or insulting them by performing intricate handwork. When Dorothy asks to see The Wiz, the queer citizens laugh at her and continue to strut around the stage. Tinman recognizes this slight and asks, “Why the shade? She asked a perfectly normal question.”Footnote 83 Normality does not, however, sit well with the queer citizens. They respond to Tinman's challenge by holding an old way vogue battle, performing precise floorwork, spins and dips, hands, duckwalks and catwalks until they win the battle by pinning the motionless intruders into a tight circle. Having won the battle, the queer citizens return to their neutral positions on the dance floor and ignore Dorothy's pleas for assistance until she proves her mettle by voguing with them. Taking her rightful place on the ballroom dance floor allows Dorothy (and spectators) to challenge the concept of normal, embrace queer black feminist identity, and stake a claim to the heretofore culturally appropriated dance form.

The Wiz Live! questions the normality of gender binaries through Queen Latifah's drag king performance. Audiences first encounter The Wiz as a tower of strength wearing emerald green pants and a floor-length suit coat. An oversized lapel and additional pieces of sequined fabric create the illusion of bulk at the shoulders, as well as obscure any semblance of breasts (Fig. 3). In contrast to many drag king performers, Queen Latifah does not sport facial hair to signal gender illusion. Rather, she relies on exaggerated makeup and movements to create the appearance of masculine features and behavior. A gender-neutral silver and green pompadour provides greater height to the looming figure. The Wiz commands respect from all their subjects, including the newly arrived Dorothy, who addresses The Wiz as “sir.” Unfortunately, this deferential treatment quickly vanishes once The Wiz's original sex assignment is revealed. The following conversation ensues:

Dorothy: You mean The Wiz is …

Lion: A fraud.

Tinman: And a woman!

Dorothy: And what's wrong with being a woman?!

Tinman: Nothin’.

Dorothy: That's right, nothin’ wrong with being a woman. I don't know where y'all fools learned y'all manners.

Figure 3. Queen Latifah (The Wiz) sings “So You Wanted to Meet the Wizard.” Screenshot of NBC's The Wiz Live! (2015), courtesy of the author.

The consequences of The Wiz's decision to embrace gender ambiguity can be read by queer black feminist spectators as a metaphor for the very real battles the black LGBTQ community encounter. The Wiz—performed by an actress who has consistently refused to make a public statement about her reported relationships with women—lives in constant fear that their social position will be taken away should others discover that they are, in fact, a “fraud” or sex-assigned female. Unfortunately, US society is not that far removed from the prejudices of Oz. One need look no further than the US Supreme Court's decision to uphold the Trump administration's policy of barring transgender soldiers from serving in the military.Footnote 84 To prevent this social death, The Wiz lives a solitary lifestyle, completely disconnected from friends or family. Thus, even the fantastical land of Oz cannot escape the pressures of gender constructs.

Once their sex assignment is discovered, The Wiz must choose between their desire for personal autonomy and position within their community. While liberal-minded Dorothy can accept The Wiz as a strong woman leader—doing otherwise would be rude—she cannot accept their deception (i.e., gender fluidity). Dorothy now refers to them as “Ms. Wiz” and pressures them to come out to the world. The Wiz reluctantly complies, revealing that they began their career as an assistant for a magician named Alfred. After constant strife with their employer, The Wiz took off in a hot-air balloon, never suspecting that a storm would take them to Oz. Once surrounded by the people of Oz, The Wiz was left with no alternative but to don Alfred's hat and perform. While the new book implies that The Wiz was forced to perform—Scarecrow, after all, likens their secret lifestyle unto a “fancy prison”—queer black feminist spectators can delight in the fact that the actress Queen Latifah gets to perform as a drag king. Eventually Dorothy convinces The Wiz to return to the “real world” so as to experience family, friendship, and “warm hugs.” To achieve this community, The Wiz must first abandon their source of power: a queer identity. They do so by concealing their innermost desires behind a neutral, shapeless, floor-length dress. The Wiz's new, socially acceptable facade not only renders them powerless, but also stabilizes gender binaries.

Mary J. Blige's camp performance provides a more pleasurable alternative to The Wiz's disappointing narrative arc. At first glance Blige (Evillene) appears to embody some of the characteristics of Mabel King's performance as the dangerous dyke. To begin, Blige delivers nearly every line as a shout and wields a knife on an unsuspecting Dorothy (Williams). Exposition reveals her merciless nature and business savvy. According to Lord High Underling, Evillene declared “a corporate takeover,” which forced him (and presumably others) to relinquish his factory and become her lowly worker. Her callous disregard for others is further exemplified by her grand arrival in a large cart pulled by two exhausted Winkies.

Stripped of the prosthetic nose, acne, fat suit, intentionally terrible wig, and garish costume of earlier Evillenes, Blige invites viewers to imagine a more humane and desirable vision of queer black womanhood. As an attractive black femme, Blige wears a corseted top that accentuates her small waist, tight leggings that emphasize her slim figure, and high-heeled boots that elongate her 5′9″ frame. Sporting red lipstick, large false eyelashes, and artfully placed makeup that emphasizes her cheekbones, Blige appears as a far cry from King's Evillene. Blige's costume does, however, maintain the semblance of authority and cruelty through a bejeweled tie and numerous decorative whips placed at her shoulders and hips. However, in contrast to previous depictions, the new book allows Evillene to appear quite logical. For example, when Dorothy calls her “plain old everyday passable mean,” Evillene delivers the rejoinder, “Well if I'm mean, what does that make you?” She then accuses Dorothy of committing such vile acts as killing her sister, stealing her sister's shoes, and gathering a “crew” to kill her. Similar to the sympathetic Elphaba from Wicked (2003), Evillene challenges audiences to consider her suffering caused by Dorothy's actions. Her attractiveness and ability to situate herself as a victim encourages queer black spectators to desire her and relate to her pursuit of power.

The disconnect between Blige's sincere desire to channel human behavior and her exaggerated performance of evil could become camp for some viewers. Blige remembers that when she first accepted the role, she felt like “a fish out of water” because of the play's cultural significance.Footnote 85 “I played in something that meant so much to our culture for so many years and to be a part of that [now] when you [were once] a little girl at home watching this? It's like ‘wow,’” remembers Blige.Footnote 86 To add to this pressure, The Wiz Live! marked her first performance on a Broadway stage. Blige understood that spectators would compare her performance to King's, which meant that she needed to conceptualize her own unique interpretation of Evillene. “I made the role my own by channeling what I already knew, which is everybody has an Evillene. Everyone has a bad side. Everyone has a good side. Also studying Mabel [King] in her role. But mostly just looking at life, how it can actually bring the Evillene out in you,” remembers Blige.Footnote 87 Her glorification of character over authenticity resulted in a heightened bitchiness best exemplified in her harsh remarks to her noncompliant henchman. In her performance, Blige uses exaggerated arm movements to emphasize her points as she bellows, “You some kind of Eddie Murphy or something? Well, don't try me ’cause I am evil with all y'all today!” Blige's sincere attempt to deliver such drivel within the spectacular world of Oz creates a sense of artifice and frivolity in which queer black feminist spectators may take delight.

Blige, however, is not merely an object of camp, but a cultural producer in her own right, fully capable of signifyin’ to her subculture. While Blige has yet to describe her performance as camp, her 2016 interview with Zach Laws suggests an awareness of the humor her performance elicited. “I watched it several times and I thought it was hilarious. It was funny to watch me just be so mean,” remembers Blige.Footnote 88 Central to her delight, it would seem, was her ability to convey meanness to others. This meanness takes the form of a confrontational attitude and aggressive behavior. For example, she all but snarls as she plots her revenge, bellowing, “So, Dorothy thinks she can walk her skinny ass up in here and destroy me?! Well, it ain't my first time running a nursery. I know how to handle a brat like that. Unleash my winged warriors!” Taken at face value, Blige's performance may appear to reinforce the black bitch stereotype, a controlling image that “is designed to defeminize and demonize” working-class black women, according to Patricia Hill Collins.Footnote 89 Blige's outrageous performance of bitchery, however, creates an excess that effectively destabilizes this mythology. Her seemingly aggressive barbs also create a space for the black cultural expression of signifyin’.Footnote 90 Blige and Williams exchange a series of insults back and forth throughout the production. Their seemingly cruel words more accurately represent “snaps,” or the linguistic acrobatics needed to play the dozens (Fig. 4). Spectators familiar with this African American game would find additional pleasure in witnessing Blige's display of mental acuity. Blige's performance—which can be understood as both queer and black cultural expression—functions as an important site of reclamation.

Figure 4. Mary J. Blige (Evillene) engages Shanice Williams (Dorothy) in the dozens. Screenshot of NBC's The Wiz Live! (2015), courtesy of the author.

Conclusion

Although The Wiz Live! is set in the contemporary United States and features an all-black principal cast, the televised production remains silent on important issues impacting black America today. The executive decision not to use the production as a platform to confront US society's racial problem does a disservice to the legacy of The Wiz. The original Broadway book and production did not shy away from symbols and metaphors of police violence and black political struggle. The Wiz’s critical and financial success on Broadway demonstrated that it is possible to produce politically engaged popular entertainment. Rather than integrate the growing numbers of unarmed black people killed by police and white vigilantes into its narrative, The Wiz Live! book takes jabs at dated references for cheap laughs. Nevertheless, The Wiz Live! also presents new images of queer black feminist strength and unapologetically celebrates queer black culture. In this sense, The Wiz Live! accomplishes what many black liberation movements of the past have failed to do: it demonstrates why queer black visibility matters. Artists now, more than ever, have a responsibility to create meaningful art that boldly attends to the intersections of black identity. Furthermore, theatre institutions need to create opportunities for queer artists of color and their allies to reclaim and write queer black feminist subjectivity into history.