This essay explores the socioeconomic resonance of Italian professional theatre in the early modern period by considering a few records of performance by indigent entertainers, and by exploring the persistent theatrical and textual presence of poverty and hunger in texts both central and adjacent to the professional actors. Whether or not a given troupe or actor directly experienced or even cared about poverty, famine, destitution, or other social issues, by the time of the commedia's “golden age” these themes had by dint of theatrical tradition and performance sedimentation become part of the actors' repertoire, much more central to their performance tradition than they were in English and Spanish early modern theatres. Partly because of the medieval legacy of the itinerant mendicant orders in Italy, the commedia dell'arte inherited a culture in which poverty, begging, itinerancy, and a certain disposition to perform degradation were in the air, and this was absorbed into the grammar of their performance. Not only were tropes and gags of hunger and destitution continually deployed in the commedia, but some of the actors assumed, for their own rhetorical purposes, the histrionic pose of destitution. In other words, whatever their professional fortunes, they “played” poverty both onstage and in their offstage personae.

Whether or not this social dimension of the commedia dell'arte had political implications is difficult to answer from the available evidence. In many cases, it was probable that the actors were exploiting gags and themes that, simply put, played well. According to the traditional Aristotelian notion of the comic protagonist as someone socially and morally inferior to the spectator, poverty, hunger, and degradation were funny to the early modern spectator. But if we establish that poverty was a central and persistent topos in the commedia, it is also possible to imagine representations of poverty that could pass beyond Aristotle's limitation of the comic to that which does not cause pain.

It cannot be claimed that the commedia dell'arte was a directly political theatre. In Italy, this theatre flourished between 1570 and 1630, which was also the high-water mark for the Italian Counter-Reformation. As with the scripted commedia grave (serious comedy), pastorale, and tragicommedia that issued from courts and academies after the Council of Trent (1545–64), the productions of the commedia dell'arte in its initial Italian phase did not challenge ducal or ecclesiastical authority. Similarly to the situation in England, the professional theatre was severely attacked by religious figures, but the critiques were based on moral and not socioeconomic grounds. If in the all-male theatre of Shakespeare's England it was cross-dressing that particularly enraged polemicists such as Stephen Gosson, in the Italian theatre of the new actress it was the perceived corrupting effect that beautiful stage divas had on audiences that filled post-Tridentine critics such as Carlo Borromeo and G. D. Ottonelli with anxiety.Footnote 1 The Italian professional actors were scandalous, but it was because of the leading presence of actresses, the sexual license of the scripts and scenarios that they performed, and a frankly carnivalesque and scatological representation of the body, its processes and desires.Footnote 2 In other words, it was on moral and not sociopolitical grounds that they were attacked. When actor-authors such as Adriano Valerini, Pier Maria Cecchini, and Giovan Battista Andreini vigorously defended their art against the charges of moral corruption, their defenses were based on orthodox political and religious principles. From the early Cinquecento theatre of Ruzante, who in the late 1520s staged the dire hunger of Paduan peasants, we appear to have moved to a radically depoliticized drama in the latter part of the century: sexually scandalous but hardly a political threat. But to say that the commedia dell'arte did not convey political messages does not necessarily mean that it was devoid of socioeconomic significance. In order to establish a more social residue, however, it is important to examine the entire range of the commedia dell'arte, and not just the famous troupes such as the Gelosi and the Confidenti who enjoyed the patronage of the northern Italian courts.

Several factors caused poverty and vagrancy to spike in the early sixteenth century. Sharp demographic growth tested the limits of agrarian technology, and the gradual capitalization of agriculture generated a wide-scale dispossession of land from peasants. After an increase in international trade that followed the establishment of new sea routes in the Far East and the Americas, a new urban concentration of wealth generated a pan-European price inflation. This, in turn, sharply lowered the value of real wages.Footnote 3 According to Marx, in the general transition from feudalism to early capitalism, the serfs were “suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence,”Footnote 4 and cast into the early modern market as “sellers of themselves.”Footnote 5 Large numbers of European peasants lost their land, and if they could not eke out a living as day laborers, they were often forced into an existence of itinerant begging. The transition from relatively secure feudal structures to the market meant both new forms of poverty and new avenues of opportunity. Italy was no exception here, and matters were compounded by the invasions of French, Spanish, and imperial troupes from 1494 to 1559. Venice, the crucible of the early professional comedy, was particularly hard hit by poverty and epidemic diseases such as the bubonic plague and typhus in the early sixteenth century because of a calamitous combination of its own wars and poor harvests. As Brian Pullan and other historians have noted, massive urban migration from country to city caused a widespread increase in begging and vagabondage in Venice and other northern Italian cities.Footnote 6

General public concern about the problem in the 1520s elicited pan-European responses to poverty and prompted programmatic written responses by humanists such as Erasmus, Vives, and More.Footnote 7 Although the historical commonplace of the medieval veneration of the poor has been complicated by the renowned Polish historian of poverty Bronisław Geremek,Footnote 8 Venice's response to the problem in the 1520s can be seen to mark a historical shift, if changes of longue durée are principally measured not so much by the presence or absence of certain ideas but by shifting hierarchies of values: a turn from the church as the principal organ of poor relief to an increased use of state apparatuses to count, control, contain, persecute, and reform beggars and vagrants. The notion that charitable responses to poverty had to distinguish between the worthy poor—those truly indigent and unable to work—and the “sturdy beggars,” or unworthy dissemblers of poverty who managed to deceive the public with theatrical stratagems—can be found at least as far back as the twelfth-century Decretum Gratiani and even the Church Fathers.Footnote 9 By and large, however, the idea that the poor deserved the benefit of the doubt remained viable throughout the medieval period, and was certainly buttressed by the emergence of the new mendicant orders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. It was when the early stages of capitalism in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries rendered poverty and vagrancy a mass phenomenon that writers such as Vives, Erasmus, and Luther, along with municipal authorities, declared what was a essentially a “war of signs,” in William Carroll's apt phrase regarding the English context.Footnote 10 The problem had become so severe that both the individual and the state had to distinguish the “true” verbal and visual signs of poverty from the deceptive signs of the theatrical imposters. The “actor's” performance and the “audience's” reading of the signs of histrionic poverty became serious business. The commedia dell'arte, and popular literature that enlisted commedia characters and themes, drew upon this theatre of everyday life.

Among the increased number of itinerants were those who explicitly attempted to eke out a meager existence by performance—“sellers of themselves” in an even more literal sense than Marx may have intended—and state authorities quickly assimilated them into the category of the vagrant beggar. As Paola Pugliatti has aptly noted, strolling players were associated with vagabonds, and vagabonds with strolling players, because of a general fear of changeability—whether of place or identity.Footnote 11 In the Archivio di Stato of Milan, in the January 1546 records of the Conservatori di Sanità, the presence of various itinerant beggars and entertainers (zaratani, or charlatans) is signaled out as a particular danger. The office decries the “excessive number of … rogues, charlatans, and other sorts of foreign beggars present in this city, who can easily spread infectious diseases.”Footnote 12 These beggar-entertainers, for obvious reasons, were drawn to piazzas and the fronts of churches; a 31 May 1566 edict censures “masters and performers of comedies, herbalists, charlatans, buffoons, zanni, mountebanks, and other people of similar trades” who tended to gather in places like the Piazza del Duomo.Footnote 13 These kinds of performers, otherwise undocumented, were normally given three days to leave the city, under the penalty of either a substantial fine or public torture, the latter probably much more frequent given their poverty. The well-known commedia actor Tristano Martinelli, not without compassion, laments the treatment of a certain acrobat Gasparo and his company in Mantua, complaining that the authorities

banished all of the actors, charlatans, and anyone else who was found in the city they gave only an hour to leave—one has never seen such cruelty. And on top of that, three days ago Gasparo the acrobat, who didn't know about the cruel edict, came with his company, and in order to make an example of these kinds of people they gave them three wrenchings of the rope.Footnote 14

If itinerant performers were perceived as vagrant beggars, then the reverse was also true. Guides in the “war of signs,” texts such as Teseo Pini's Speculum cerretanorum (MSS. dated 1484–6)Footnote 15 and the anonymous Liber vagatorum (c. 1510)Footnote 16 promulgated the notion that the poor were organized into various trades essentially based on theatrical illusion, and they provided catalogs for the wary bystander of the various sorts of deception presumably practiced by vagrant beggars. This idea was repeated in so many European texts, of which the best English example is Thomas Harman's A Caveat for Common Cursetors (1565),Footnote 17 that a strong case has been made by Linda Woodbridge that this notion of theatrically dissembling beggars organized into various specialties was mainly crafted by humanist-based literature, following the jest-book tradition.Footnote 18 A consideration of the continental context, however, where mendicant culture probably rendered both the actors more compelling and the “audiences” more disposed to be moved compared to England, indicates that these “performances of everyday life” probably frequently occurred. Indeed, in both continental and English studies of poverty, the central debate regarding these texts regards their relationship to historical reality. Piero Camporesi (if generally a brilliant writer on these matters) tends to equate the representation of poverty in literary texts with actual fact,Footnote 19 as do some of the early treatments of English rogue culture, such as that of Gāmini Salgādo's The English Underworld. Footnote 20 But recent works, such as Craig Dionne and Steve Mentz's important collection of essays regarding the English rogue, argue more accurately that the rogue figure and the vagabond beggar engage both historical and literary discourses in complex ways.Footnote 21

The history of the “rogue's catalog,” in fact, which goes back much earlier than the sixteenth-century texts normally considered by scholars of early modern poverty, interestingly conflates the “reality effect” and the literary impulse. The municipal registers of Augsburg in 1342 and 1343 describe, in documentary fashion, several types of poor actors practicing their arts in the city: those who claim to be converted Jews, those who feign sickness, those who disguise their legs to simulate disease, and so on.Footnote 22 The fifteenth-century Basler Betrugnisse der Gyler (1430–44), a series of municipal depositions, significantly extends the number of categories. At the very outset of late medieval and early Renaissance writing about the poor, it seems, the documentary impulse is bound up with a literary strain and, it is fair to say, vice versa.

If in fact we look not at literary but at archival accounts of the poor in early modern Italy, we can observe the “performances of everyday life” among the downtrodden. An entry in the Venetian Provveditori alla Sanità records dated 10 April 1548 (three years after the first extant commedia dell'arte contract) reports that a certain Giacomo Antonio di Vicenza was exiled for “making himself shake, wearing a blood-stained cap on his head, although he is healthy and energetic.”Footnote 23 Di Vicenza's performance, in fact, is very similar to the kind of theatrical practice described in the Speculum cerretanorum under the rubric of the “Attremanti,” or “Tremblers.”Footnote 24 In 1548, a certain Aaron Francoso di Sarzana was arrested by the Venetian Inquisition and confessed to having been baptized four times as a Christian—performing conversion for his livelihood, in the manner of one of the types recorded in the Augsburg registers.Footnote 25

The anonymous early seventeenth-century L'arte della forfanteria Footnote 26 figures the life of the vagrant as, essentially, a theatre without borders. The dexterous vagrant must suit his fictions to the theatrical context—“knowing how to lament at the proper time and place”Footnote 27—and must be a walking repertoire of routines and narratives, in the oral-formulaic, improvisatory manner of the commedia actor: “having fifty wars in one's imagination … at times feigning to have escaped from the hands of the Turks.”Footnote 28 He must be the consummate makeup artist, “spreading over the hands, arms, and face ground meat in order to appear leprous”;Footnote 29 a master of theatrical gesture, “turning up the eyelashes and twisting the eyes”;Footnote 30 and skilled in oral delivery, capable of Dottore-like nonsense (“speaking out of turn and stammering”)Footnote 31 and of eliciting the poor man's version of pity and fear “with a piteous voice and a bowed head beseeching this one and that one for a bit of wine.”Footnote 32 The commedia dell'arte, therefore, emerged from a culture whose lower echelons appeared to take a particularly theatrical turn under social and economic pressure.

The itinerant commedia dell'arte actors surely shared some of the same roads used by the vagrant beggars.Footnote 33 Much must have depended on whether the traveling actors could have afforded, or would have been rewarded by their patron, a mule or a horse. Most travelers went by foot, achieving a maximum of twenty-five kilometers per day, and crossing the Alps, which the commedia actors frequently had to do, was better done by foot than by horse. Renting a mule for two days would have cost an entire week's salary for an artisan.Footnote 34 Even with a horse or a mule, travel was difficult because paved roads were extremely rare, making rain a major problem, as Tristano Martinelli attests to a ducal secretary in Mantua on 19 September 1609:

I wasn't able to arrive earlier because I fell into the water with my horse, who I think is going to die…. With a great deal of trouble, I was able to borrow a horse in order to come to Mantua. I made it, thank God, but I'm half-ruined and I've become sick from those terrible roads…. Well, here I am: soaked and smeared with mud.Footnote 35

Martinelli petitions hard for a replacement horse, without which he would have more readily been perceived as a vagrant. And even this advantage was no guarantee that the traveling actor would not have been assimilated into the category of the dangerous and unsavory itinerant, as Domenico Bruni attests in his Le fatiche comiche (1623):

If I were to tell you about the misadventures that happened to me and the dangers that I underwent in the three and a half days it took us to get from Bologna to Florence, it might seem like a fairy tale and yet it's true, because in Savena we almost drowned, and in Scarica l'Asino the wind knocked me off my horse, or mule, or whatever. We had to descend the Giogo by foot, and in Florence no one was willing to take me in that evening because I looked too much like a beggar.Footnote 36

“I looked too much like a beggar”: the external signs of the exhausted, bedraggled Bruni could as easily denote a beggar as an itinerant actor. As Bruni's anecdote demonstrates, admission to an inn was not automatic, even if one had the money, especially if one was a “foreigner,” which the transregional comici usually were. Concern about the importation of infectious diseases by foreigners motivated authorities in the Milan region to require innkeepers to report the names of all foreigners whom they lodged, as well as their “nation,” whether they were bearing arms (unemployed soldiers were a particular concern), and whether they had a horse.Footnote 37 Lodging in inns was therefore far from automatic, and travelers often had to sleep in barns. As the quotes from Martinelli and Bruni demonstrate, the itinerant Italian actors, lacking the national center and fixed stage enjoyed by their English contemporaries, suffered the vicissitudes of travel much more often than the English actors. This is one of the reasons why both documentary and performance commedia texts convey a much more palpable sense of the material body and its needs than English analogues.

Popular poems and dialogues performed in piazzas and banquet halls and sold to a primarily middle-class audience depict the zanni's voyage as degrading, perilous, and extremely uncomfortable. In the late sixteenth-century Bergamask text Viaggio di Zan Menes,Footnote 38 a vicious winter storm drives the desperate inhabitants of the Bergamask village to sleep in barns with animals, and compels the narrator to travel forth in search of lodging and food, “so that I could recover from cold and famine.”Footnote 39 He describes himself as homeless: “for I couldn't find a manure heap a house, a hut, a place, a stall, or a roof, that would keep my poor self covered.”Footnote 40 Exhausted, he travels and arrives at an inn, desperately banging at the door with both his feet and his hands, where he is met by a surly innkeeper. Quickly sensing that this dubious client doesn't have the money to pay, the innkeeper sardonically insults him in the way of rogue's cant, as a “segnur” (lord), a “baru” (baron), and a “canoneg de doana” (a canon of the customs house). He threatens to beat him up, and finally casts him outside, where the embattled Zan Menes is forced to sleep in an animal stall with a disorderly group of other abject travelers: “there, among this scum he abandoned me in the dark, in this shithouse of a barn.”Footnote 41 A fight breaks out among Zan Menes's unfortunate bedmates, foreign refugees from diverse Italian towns. Relief for the bedraggled zanni only comes in the morning, after a night that seemed as long as three years.Footnote 42

Some social history can illuminate certain aspects of the commedia dell'arte zanni. Because the pre-Alpine area of Bergamo (near Milan) had become part of the Venetian Republic in 1428, Bergamask hill dwellers had in fact migrated to Venice and other cities.Footnote 43 The land in the Bergamo valleys was not particularly fertile, and like other areas in northern Italy it was affected by foreign wars and general economic decline in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Bergamask émigrés certainly suffered in adjusting to new urban environments, as the Viaggio di Zan Menes indicates, but they also developed a reputation, extended even beyond Italy, of the kind of resourcefulness and ingenuity that in fact provides a chief characteristic of the commedia zanni.Footnote 44 Literary parodies of Bergamask people may have actually resulted from the fact that Venetian natives appeared to have resented these immigrants for their relative success compared with other newcomers, although there are also records of impoverished Bergamasks begging in the streets of Venice, such as a certain Stefano Sartorelli in 1545.Footnote 45 The Rialto, where the most dense commerce and circulation of marketed goods occurred, particularly drew the incoming Bergamasks, and enough of them assumed the job of porter (facchino) that the position became associated with the people—a large number of whom, often identified by nickname as if already a theatrical type, are recorded in the parochial registers of the Rialto.Footnote 46 As a dense locus of material plenty, the Rialto of course drew beggars, and this sharply delineated the gap between rich and poor that was exacerbated by early capitalism.

In another opuscolo, the 1579 Viag[g]io del Zane a Venetia,Footnote 47 the Bergamask zanni is spurred by hunger at the end of the year (a particular time of scarcity) to leave his native land and go to Venice. He has been starving and he makes sure to pack his bag “so that neither hunger nor thirst afflict me”Footnote 48 and with a bastone (club) for protection on the road. Traveling by boat on a canal, he finally reaches the Serenissima, where he is astounded at the concentration of vendors, buyers, goods, and beggars: “I was astonished and dumb-struck seeing so many things sold by the pedlars.”Footnote 49 But what might have been merely a hymn to Venetian commerce suddenly abruptly changes when other very different voices of the street are interpolated—that of a blind man and then of a woman with four children, one blending into the next: “Which of you gentlemen can deign to help this downtrodden blind man who has been robbed of his sight, and is barely alive?”; “Lords, don't hold me in disdain, miserable with my four children.”Footnote 50 The voices of the poor modulate from one to the next, as if invoking a collective presence, placing deprivation side by side with abundance in the concentration of plenty and scarcity that characterized this commercial hub. What might have been merely a hymn to commerce (and merchants counted among readers and viewers of this kind of performance text) ends up juxtaposing the dark side of early capitalism to material copia. The historical Bergamask immigrant to Venice, a city that particularly suffered from numerous famines, must have been frequently exposed to acute poverty.

Many Bergamask immigrants became servants in the houses of citizens, merchants, and patricians. If we think of his rural origins, the Bergamask servant working for the Venetian citizen Pantalone can be seen as a version of Marx's serf, “transformed … into a free proletarian … who … found his master ready and waiting for him in the towns.”Footnote 51 However, service to “Pantalone” did not guarantee an escape from poverty. As Stefano D'Amico has argued,Footnote 52 many of the Italian poor in the sixteenth century were “working poor”: a category applied by Patricia Fumerton in her study of poverty in early modern England.Footnote 53 Up to 15 percent of the working population were employed as servants, but job security was only as stable as the master's fortunes. A 1574 commentator observed that “servants and maids change every day.”Footnote 54 The commedia gag of the “servant of two masters,” which Goldoni did not invent in the eighteenth century but appropriated as a traditional commedia device, can be seen in this light: one job was never enough.

If we consider the zanni's master Pantalone himself in the light of Shakespeare's merchant of Venice Antonio, whose very livelihood hangs upon the precarious fortunes of transmarine commerce, his epithet “Pantalone dei Bisognosi” (Pantalone of the Needy) comes into new relief. In the fluctuating, unstable economy of early capitalism, the numbers of the “poor” could expand from the 4–8 percent who were chronically destitute, to the 15 percent who regularly received assistance at certain times of the year, up to the 50–60 percent of the European population whom a crisis could force into poverty.Footnote 55 Poverty and wealth, of course, are not absolute but relative terms, and the particular instability of early modern capitalism meant that, compared with today, a higher proportion of the population would have considered poverty a potential calamity in their lives. Among those whom crisis could force into poverty could be counted the poveri vergognosi or the “shame-faced poor,” for whom there were special provisions of assistance aimed at protecting these fallen merchants' (or even aristocrats') dignity. Pantalone's occasional degradation (in one work he seeks the aid of a gypsy healer because he has become infested with lice)Footnote 56 can be seen in this light.

Many commedia dell'arte actors vigorously attempted to distance themselves from the material social origins of the commedia dell'arte. Isabella Andreini, for one, actually attempted to suppress charlatan performers in Milan.Footnote 57 Other actors such as Tristano Martinelli, however, exploited the buffone (buffoon) or ciarlatano (charlatan) personae, and presented themselves (as they often actually were) as one degree of separation from the world of poverty and material constraint. The originator of the Arlecchino role,Footnote 58 a French–Italian hybrid that was a version (non-Bergamask, actually) of the zanni, Martinelli frequently deploys the topoi of poverty, famine, and degradation. This can be seen both in what he performed onstage and in the persona that he presented offstage to his ducal and royal patrons.

As he attests in one letter,Footnote 59 Martinelli himself performed in the street and piazza as a young man. In 1577, in the same year that the more prestigious Gelosi company performed at the French courts of Paris and Blois, Martinelli was working with his brother Drusiano and ten other actors in Antwerp, where two prominent Italian merchants living there had to testify to the police that they were not deserted soldiers, frequent figures of crime and vagabondage in the period.Footnote 60 Because of his previous performance as a piazza charlatan and “information” that he was reputed to have about those currently practicing the trade, the Mantuan authorities appointed him supervisor of piazza and street performers. In a 1599 edict, he was given authority to supervise, tax, and penalize the following kinds of figures:

[M]ercenary actors, jugglers, acrobats who walk the tightrope, those who present demonstrations and structures and the like, and charlatans who put up benches in the piazzas in order to sell oils, unguents, salves, antidotes against poison, perfume packages, musk water, civet, musk, stories and other printed pamphlets, animal claws, and those who put up signs to advertise treatment, and similar kinds of people.Footnote 61

In this paratactic, but tantalizingly suggestive, list, the lives of thousands of unnamed piazza performers can be glimpsed. Martinelli's own social position relative to these performers is ambiguous. On the one hand, he does exploit the piazza performers, clearly profiting from the taxes that they must pay him. On the other hand, Martinelli's relationship to the kind of marginal performance that he had himself practiced was not always, and not merely, exploitative, as several letters in his correspondence indicate.Footnote 62 He seemed to have been particularly concerned to protect the charlatans' mobility and sovereignty in regard to space, as someone who himself was used to traveling “per il mondo” (through the world).

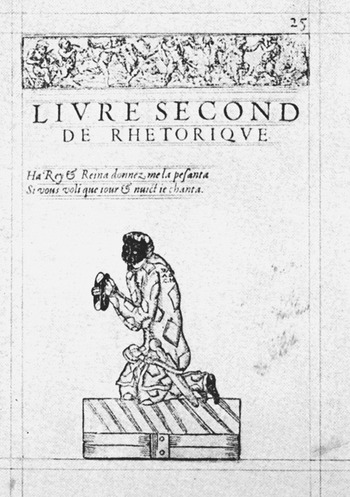

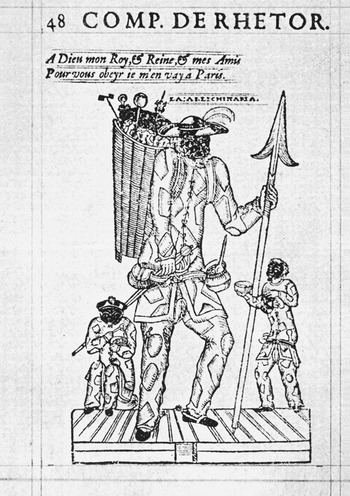

Certainly by the time of his 1600–1 tour to Paris, Martinelli had become a well-established actor who performed in the courts of Mantua, Florence, Turin, and other Italian cities as well as in France. Capable of buying land outside of Mantua in 1602, enlisting sovereigns across Italy and France as godparents of his many children, he could scarcely claim to be poor. But he continued to stage it. Martinelli's Compositions de Rhetorique was printed between December 1600 and January 1601 in Lyons, where Martinelli had stopped with his specially assembled and invited company on his way to Paris, where he arrived in January 1601.Footnote 63 This strange text, which contains fifty-seven blank pages and only thirteen pages of text and engraving, appears to have been destined for the small circle of the French King, Henry IV, and his Queen, Maria de' Medici, and clearly aimed to advertise the company's imminent performance in Paris. For our purposes, what is interesting is that Martinelli poses as a suppliant, staging a strange blend of cockiness and destitution. On page 25 of the text, he supplicates the king and queen for the gold medal and chain that he requests for his recompense, abjectly crouching on his knees and slumping his shoulders (Fig. 1). He stages destitution, begging for bread, and he riddlingly jests with Henry and Maria (promising to give them “half of nothing” in exchange for his reward) and threatens to return to Italy if he does not receive his medal and chain. On page 48, an Arlecchino who is manifestly on the road carries spurs, a traveling hat, a small sack, a bowl of food attached to his waist with a spoon protruding from it, and, in order to protect himself against the dangers of travel (which could include encounters with bandits), a spear and mace (Fig. 2). He travels with his “Allichinaria”: a destitute family of little Arlecchini. One of them, crouched on the ground, voraciously eats; another imploring figure holds out an empty bowl; yet three others are crammed into a basket carried by Arlecchino on his back. He stages here nothing less than hunger, as if to invoke, before Henry IV and in a kind of nostalgic, neofeudal manner, the medieval notion that it was the duty of the king to feed the poor.Footnote 64 What distinguishes this from the classic medieval exchange between king and beggar is that Martinelli, as a “seller of himself,” must conjure it up in performance, outside the context of institutional practices established by medieval churches, monasteries, and confraternities to aid the poor.Footnote 65

Figure 1. Tristano Martinelli, Compositions de Rhetorique (1601), 25.

Figure 2. Tristano Martinelli, Compositions de Rhetorique (1601), 48.

There is every indication that Martinelli extended the persona of the impoverished performer onto the stage, as in the role of Nottola that he performed in Giovan Battista Andreini's scripted play Lo schiavetto. Footnote 66 Accompanied by his cohort Rampino and a band of eight other vagabonds, Nottola leads the life of the itinerant charlatan, speaking rogue's cant, or furbesco, living a life of petty crime, and surviving by performing the signs of poverty and degradation, which are never conclusively revealed to be either true or false. As with the Harlequin persona of Les Compositions de Rhetorique, Nottola stages a peculiar blend of degradation and bravado: he is dressed in rags and plays the part of the destitute itinerant, but claims that he is descended from Spanish kings and lords it over his little company.

The role of Arlecchino in Flaminio Scala's 1611 encyclopedic collection of scenarios, Il teatro delle favole rappresentative, also draws on material that Martinelli probably performed.Footnote 67 Writing with as much of an eye toward the literary consumer as to the theatrical practitioner, Scala compiled his scenarios well after his own active career as an actor, and there is a memorial, as well as a literary, quality to the collection. The role of “Isabella” clearly celebrates Isabella Andreini, deceased seven years earlier, and the part of “Capitano Spavento” clearly refers to her husband Francesco and conjures up some of his favorite routines, after allowing for the patina of Scala's literary embellishment. In the Teatro, Arlecchino usually accompanies his master, the Capitano. Both are outsiders, even foreigners, and it is possible to glimpse in the pair the two sides of unemployed itinerancy (both refusing the early capitalist injunction to work) dramatized in numerous opuscoli: the lazy Arlecchino, paradoxically both famished and gluttonous, sings the praises of “poltroneria” (laziness), and the volatile, violent Capitano performs traits of the discharged, vagrant soldier or the unemployed “bravo.”Footnote 68 In Scala's collection, Arlecchino frequents, and participates in, the particular worlds of petty crime that were aligned with poverty in the period, such as prostitution (“Isabella Astrologo”) and thievery (“Il dottor”) (Day 13). He falls into the role of a charlatan dentist in “Il cavadente” (Day 12), plays a rogue in “Il Pellegrino fido amante” (Day 14), and frequently projects a persona of degradation.

The commedia dell'arte character system is organized vertically according to the three status levels of vecchi (old men), innamorati (lovers), and zanni, and Scala's Teatro demonstrates how the lowest level especially communicates with a fourth: the impoverished underground in northern Italian cities consisting of beggars, pickpockets, gypsies, card sharks, fugitives, rogues, courtesans, prostitutes, and madmen. If, despite his constant hunger, the zanni usually represents an employed servant, reflecting the Bergamasks' relative success in Venice, his service is not secure, and he knows those who have fallen off the economic edge. The inns commonly invoked in the scenarios often collect various undesirables. Scala himself, in fact, was not far from this world; he owned a “profumeria” on the Rialto in Venice that sold not only perfumes but oils, salves, and medicaments of the kind hawked by Martinelli's underlings in Mantua. The list of props included among the prefatory material for each scenario suggests that gags involving begging, vagabondage, and hunger were a regular part of the comici's repertoire. Props include bread (frequently given in the scenarios to real or pretended beggars); travelers' clothing of a distinctly destitute air; begging paraphernalia, such as a stool; and an eye patch for actors either playing a blind beggar or impersonating one within the fictions of the plays.

In fact, each of the three major status levels of the commedia dell'arte could play the “fictions of the poor” that were so ever-present in Italian early modern culture. We shall examine three of Scala's scenarios, each emphasizing a different group that assumes the guise of poverty.

The underworld subplot of “Le burle d'Isabella” (Day 4), in which topoi of poverty are dramatized in the zanni, can here be explained without detailing the complicated, erotically driven main plot. (This in itself suggests that the themes of destitution were detachable gags, or lazzi, that might stand alone in performance.) The master, Pantalone, has forced his desire upon the servant Franceschina, and then married her off to the destitute innkeeper Burattino. In order to silence them, he has bought off Burattino with a five-hundred-ducat dowry and the promise that he will give them an additional one thousand ducats for the first male child that they conceive. Burattino shifts into a course of comic obsession (similar to that of Nicia in Machiavelli's La mandragola), carrying a urinal with him onstage in order to test his wife's water for her fertility and asking everyone he meets if they know the secret of generating a male child. Pantalone's “magnanimous” arrangement is described as an act of charity. Pedrolino, Pantalone's servant, is said in the plot summary to “praise this work of charity” (I∶ 56).Footnote 69 And Franceschina sees the arrangement as nothing less than providing an occasion to rise above penury, declaring that “If he [Burattino] were potent enough to impregnate her with a male child, they would escape from poverty” (I∶ 56).Footnote 70

An early scene in Act I, which might be dubbed “fiction for food,” dramatizes Burattino's desperation (I∶ 57). Given money by the Capitano in order to buy some food, the famished Burattino begins to start eating the food even before he enters his inn. But two rogues encounter him outside of the inn and accost him. Declaring that they come from the land of “Cuccagna,” they transfix the starving Burattino by telling him of this place where there is no hunger, where succulent food fairly drops from the sky, where one is punished for working and one is paid for sleeping. As Burattino achingly listens to one of them dilate on this paradise, the other rogue eats his food. Halfway through (both the food and the story), the two beggars change places until the food is all gone, whereupon they depart, and Burattino awakens to the cruel reality of his hunger: “Burattino recognizes that it was a trick. Weeping, he goes inside” (I∶ 57).Footnote 71 Notwithstanding the comic decorum here, in performance and for the theatre audience Burattino's tears could easily transgress Aristotle's rule for comedy as the ridiculous that does not cause pain.

In the course of the scenario, Burattino and Pedrolino become at odds, and the latter vows to cuckold the former. What is interesting for our purposes is that he does it precisely by deploying the fictions of poverty, donning the disguise of an itinerant beggar with an eye patch and a walking stick (I∶ 61). Pedrolino begs alms of Burattino, who refuses him, and then invokes, for the second time in the play, the land of Cuccagna: he (the disguised Pedrolino) has been exiled from that renowned place because he has committed the unpardonable sin of working. Burattino's attention is again transfixed by the myth, and a guidone (beggar), said to be a “companion” of Pedrolino, enters the scene, except that he is now disguised as a merchant. The “merchant” hails Pedrolino and heartily thanks him for having helped him get his wife pregnant with a male child. The rogue suddenly departs and the gullible Burattino is left marveling at Pedrolino's supposed ability to achieve precisely the thing that, of course, would deliver Burattino and Franceschina from poverty. When asked how he acquired this ability, Pedrolino claims it to be a family secret passed on to him from his father, which he in turn will pass on to his son. Burattino agrees, essentially, to be cuckolded, because it is fairly clear that Pedrolino's “drug” is nothing more than his own sexual potency. However, perhaps experiencing a crise de conscience for betraying one of his own class, Pedrolino suddenly abandons the cuckold project just at the point when Burattino was announcing the supposed successful results to Pantalone. Burattino can then only dream of that version of Cuccagna to which he thought he was tantalizingly close: one thousand scudi.

“La travagliata Isabella” (Day 15), which represents the highest-status-level characters (as well as others) in real or feigned poverty, dramatizes the itinerant culture described above, in which one can never be sure whether or not the beggar is “authentic” or performing a theatrical illusion. Invoking the precariousness of the early modern capitalist society in which poverty could suddenly befall up to 60 percent of the population, Pantalone, “a man of rich fortune,”Footnote 72 effectively becomes Pantalone dei Bisognosi by the bad fortune that “was envious of his state” (I∶ 157).Footnote 73 Enraged by two inopportune suitors of his daughter he hires two bravi (the bravo, frequently a former soldier in need of work, was often employed by Venetian patricians and could be a highly undesirable social element),Footnote 74 with whose help he attempts to kill the suitors, leaves them for dead, and then becomes an itinerant fugitive with his servant Pedrolino, taking to the road with sack and stick. Arriving in Rome, he impersonates the role of a beggar, beseeching alms from door to door. It appears to be mainly a strategic disguise for him, although as an exiled murderer (as he thinks he is) the fiction borders on truth. Certainly for Pedrolino, who “in the guise of a beggar goes asking alms in a loud voice” (I∶ 159),Footnote 75 the theatrical role fits the need: he is actually, painfully hungry in his displaced state. Practically every character in the scenario impersonates a beggar at some point, including Capitano Spavento (one of the suitors, having survived Pantalone's attack), who violently devours the food that had been bestowed on Pedrolino. The Capitano's servo Arlecchino (Martinelli), also dressed as a beggar but suffering excruciating hunger, with the Capitano fools the avaricious Dottore out of a plate of food in an extended gastronomic lazzo typical of the commedia dell'arte. It is a scenario of displaced persons, in which the fiction of poverty borders on truth, enacting that curious mixture of pain and festivity that so often characterized the Renaissance beffa (prank).

In “Il finto cieco” (“The Fake Blind Man,” Day 34), the innamorato is drawn into the fiction of poverty. For betraying Oratio by falling in love with his beloved Isabella, Flavio is forced to wander for three years as a blind beggar, accompanied by his fellow “beggar” Burattino, who actually believes that Flavio is what he pretends. Flavio's impersonation appears less like the cunning impostures of the rogue books than an actual love penance, practically an amatory version of the mendicant. He enters “a feigned blind man, dressed vilely,”Footnote 76 and with Burattino “they beseech alms at every door” (II∶ 349).Footnote 77 Franceschina gives them bread and wine, but her motives are inflected by the immediate sexual attraction she feels for Burattino—and she asks him to return often for “alms.” Attempting to elicit a blend of charity and eros, Flavio declares to Flaminia that his blindness will be healed by the kiss of a young woman, which of course he receives. Within the fictional frame of the scenario, Flavio's status as a blind beggar lies somewhere between fiction and lived experience. On the one hand, he actually has wandered for three years supported by alms with the guidone Burratino as his down-and-out companion. On the other hand, it is a fiction that he has adopted—or been forced to adopt by Orazio—and it quickly lifts when the amorous intrigues of the play are resolved. The fiction of the blind beggar is clearly framed by the love story.

Many other examples from Scala and other commedia scenario collections could be provided. It is generally true that the tropes of hunger and poverty were played more frequently in the commedia dell'arte than they were in Shakespeare and English early modern drama. (What is, of course, central in English early modern drama is the representation of urban rogue culture.) In a group of early seventeenth-century commedia scenarios that remarkably resemble Shakespeare's The Tempest,Footnote 78 the group of shipwrecked victims who are cast on the magician's island are famished and spend much of their energy clownishly trying to obtain food by various “gags of hunger.”Footnote 79 Although Gonzalo complains of physical discomfort and an alluring banquet is mysteriously snatched away from the court party, hunger is hardly a central theme in The Tempest. With the kernel of its character structure based on a master–servant relationship that had roots, as I have attempted to show, in social history, the commedia dell'arte repeatedly played hunger and destitution. Certainly they played it for laughs, in the conventional vein of classical humor, but they played it so frequently that it must have also called attention to the pressing problems of poverty and vagabondage that afflicted early modern Italy and Europe. And as in much contemporary comedy, it might have hurt to laugh.