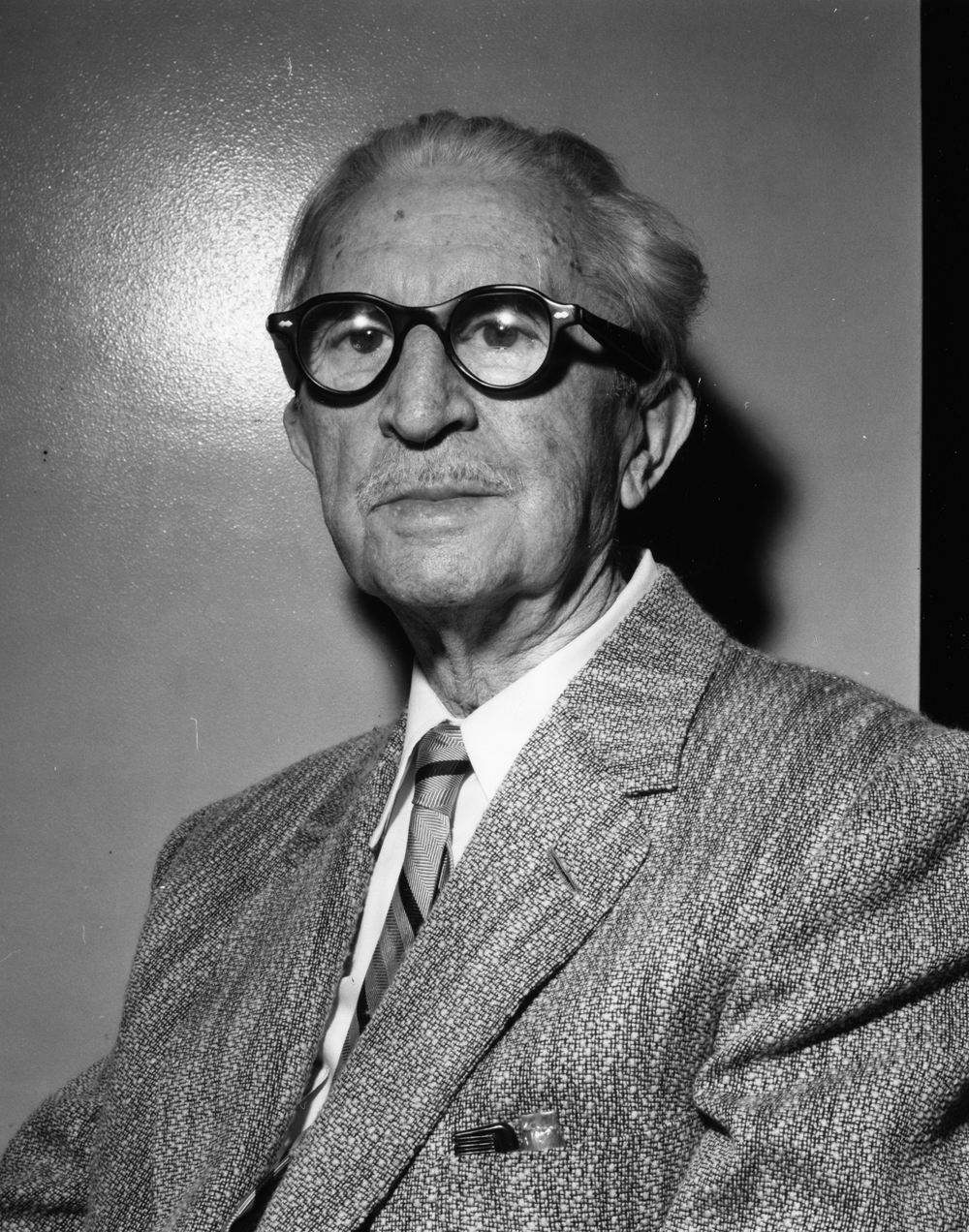

In 1920, Oscar Hammerstein II—fresh from the modest success of his debut musical Always You—was eager to write the show for Frank Tinney that his uncle Arthur was to produce. As Hugh Fordin wrote, “Arthur, confident of his nephew's ability but aware that he needed to learn more about his craft, brought in Otto Harbach to collaborate on the book and lyrics.”Footnote 1 The two men joined forces on that show—Tickle Me—and went on to write such classics as Rose-Marie (1924, Rudolf Friml & Herbert Stothart), Sunny (1925, Jerome Kern), and The Desert Song (1926, Sigmund Romberg). After working with Harbach (Fig. 1), Hammerstein would venture on his own and write Show Boat, Oklahoma!, and be credited as having ushered in a new era of musical theatre, chiefly defined by his success at “integration.” As literary scholar Scott McMillin writes, the conventional idea of integration is that “all elements of a show—plot, character, song, dance, orchestration, and setting—should blend together into a unity, a seamless whole.”Footnote 2 In popular commentary, this development is often attributed to Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1943 musical Oklahoma!, as seen in John Kenrick's claim that “[t]hroughout the show, every word, number, and dance step was an organic part of the storytelling process. Instead of interrupting the dialogue, each song and dance continued it. For the first time, everything flowed in an unbroken narrative line from overture to curtain call.”Footnote 3 Other historians and critics are more tempered, touting the success of Oklahoma! while insisting that its integration must be seen as part of a broader historical arc. Andrew Lamb, for example, celebrates Oklahoma! by noting that it was the realization of “[w]hat Kern and Gershwin had experimented with as far back as the 1920s—a piece that was not just a collection of catchy numbers, but a fusion of drama, song, and dance.”Footnote 4 In a 1962 article, Stanley Green notes that the creators of Oklahoma! “blended all the theatrical arts with such skill tha[t] many accepted it as a revolution in the theatre,” but he argues that their accomplishment was actually “more evolutionary than revolutionary. Rather than inaugurating any trend toward the well-integrated show, what it did achieve was a perfection in technique of a development that had been going on ever since the second decade of the century.”Footnote 5 While Green cites the Princess Theatre musicals of Bolton, Wodehouse, and Kern as the earliest examples of integration, this lineage goes back further—further than Hammerstein, further than Gershwin, further than Kern. To understand the history of the idea of “integration” in musical theatre, we must go back to the artist whose 1910 musical Madame Sherry, hailed as the “musical comedy rage of a generation,” was celebrated by critics for the way its “entertaining elements” were “cleverly interwoven into a consistent whole,”Footnote 6 for the innovative ways that “the songs, lyrics, and ensemble numbers . . . are directly related to the story of the comedy, and there is a plausible excuse for every musical interruption.”Footnote 7 That artist—who not only developed an innovative approach to musical theatre but also articulated a coherent theory of it—was Otto Harbach.

Figure 1. Otto Harbach (Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society)

Recent theatre histories tend to pass quickly over Harbach, yet earlier commentaries often celebrated his talent for writing musicals as a “consistent whole”: Lawton Mackall, for example, wrote admiringly in 1926 that in Harbach's shows, “songs are not just ‘pinned on’ the story; they belong in the story.”Footnote 8 In a similar vein, a 1935 magazine article opined that Harbach “has probably done more than any other individual to change the existent technique of musical comedy production,” arguing that he had known as early as 1907 that musical comedy needed to “grow up” and transcend the inevitable formula of “a weak, small plot, whose sequence was broken when it offered a favourable opportunity for a song or a dance.”Footnote 9 Even Hammerstein said as much in his 1949 book Lyrics, acknowledging Harbach's achievement: criticizing the librettists of early musical comedy, Hammerstein wrote that most were “hacks and gag men who extended the tradition of ignominy attached to musical comedy books.” However, he continues, “[t]here were, on the other hand, a few patient authors who kept on writing well-constructed musical plays, most of which were successful, and they continued to give their best with very little chance of being praised for their efforts. Among these was my dear friend and erstwhile tutor, Otto Harbach,” whom Hammerstein describes as “the best play analyst I have ever met.”Footnote 10 Indeed, Hammerstein credits Harbach with having taught him “most of the precepts I have already stated in these notes”—precepts that include, for example, the classic Hammerstein dictum that “[t]here are few things in life of which I am certain, but I am sure of this one thing, that the song is the servant of the play, that it is wrong to write first what you think is an attractive song and then try to wedge it into a story” and his preference for songs when “they are required by a situation or a characterization in a story.”Footnote 11

Given Harbach's impressive theatrical resume—which included over forty musicals on Broadway, among them No, No, Nanette, Roberta, and The Cat and the Fiddle Footnote 12—and the uniqueness of his contribution, Hammerstein writes that “[i]t is almost unbelievable that a man with this record of achievement received so little recognition.”Footnote 13 This remains as true today as it was in 1949 when Hammerstein wrote it, with most histories of musical theatre affording Harbach only a cursory tip of the hat.Footnote 14 To remedy this oversight, I explore Harbach's revolution in musical dramaturgy by considering three principal questions: What did Harbach set out to achieve? What intellectual traditions influenced his dramaturgical innovations? And what prepared the audiences of his time to apprehend and desire this new approach to musical comedy? By situating Harbach's work within a broader cultural context, I show why the audiences of around 1910 became newly invested in the narrative dimensions of music and why musical theatre—which had long relished its fragmented structure of interpolations and diversions—began to embrace aesthetic principles of organicism.

Born Otto Hauerbach in Salt Lake City in 1873, Harbach began working in the theatre after several years in academia and a brief detour in advertising. In Harbach's first two shows on the Broadway stage—Three Twins (1908) and Bright Eyes (1910)—he contributed the lyrics, while Karl Hoschna composed the music and Charles Dickson wrote the book. However, attributing the failure of Bright Eyes to its book, Harbach set out to pen his own libretto in Madame Sherry, a show that garnered critical and commercial success. One critic, reviewing the Chicago tryout in 1910, wrote that the show “is a full measure of bright, tuneful and immensely entertaining elements, cleverly interwoven into a consistent whole.”Footnote 15 This claim of “interwoven into a consistent whole” is precisely the claim of integration, suggesting that the “tuneful” elements—the songs and dances—have been braided into an integrated totality. Another critic remarked of Madame Sherry:

Here is a farce with a wealth of good songs welded into its structure. Nothing is malapropos; even an Irish ditty of seemingly conventional type has its justification. The character and situations give rise to the tuneful outbursts, as well as to the humorous entanglements. The craftsmanship in lyric farcicality is to be applauded; it invests the musical stage with a sense of artistic self-respect.Footnote 16

The overarching narrative strength of the piece was also touted, with the New York Times writing that “the plot plays a much more important part than it usually does in an American musical comedy,”Footnote 17 while the Brooklyn Life critic wrote that Madame Sherry “is almost unique among musical comedies in having a plot which survives to the end.”Footnote 18 Another New York critic agreed, writing that a “marked difference between ‘Madame Sherry’ and the present-day musical comedy is that the new play has a real plot,” adding that “of course, we do not care to see musical comedies overburdened with plots, as they are likely to become stupid, but an ingenuous story, containing so many humorous complications, is at all times welcome.”Footnote 19 The realistic quality of the drama was also widely noted. A 1910 souvenir music book of Madame Sherry notes the lifelike qualities of its characters: “In the perspectives of the land of make-believe, the people of ‘Madame Sherry’ are real and their experiences logical.” Discussing Theophilus, a somewhat oblivious collector of antiquities, the program notes that the “world is joyously filled with Theophiluses,” as the role “presents eccentricities and qualities of character that are instantly recognizable as things of comic truth despite his eccentric oddity and his many uproarious idiosyncrasies.” The part of Edward is similarly said to “continue its bright transfer from life to the stage of characters vital with comic life,” while the character of Yvonne “embodies the attitude of countless millions of other Yvonnes of all ages.”Footnote 20

These reactions suggest that Harbach succeeded in his quest to end the “battle between the story and the score of a musical play” that he felt had infected musical comedy: “Rehearsals,” he wrote, “were often a tug of war between book and music, in which music won.”Footnote 21 In other words, the book—the story—was given short shrift, while the musical elements, untethered to the plot, were given free rein. He sought to approach musicals differently, claiming to have pursued three goals when he began writing in 1906: “to put more sense into the book of a musical play; to use no vocal numbers without logical motivation; and to make the introduction of music a natural part of the action.”Footnote 22 Thus, Harbach aimed to construct libretti that depended more on realistic situations and plausible human motivations; to write songs that served the broader narrative; and to naturalize the act of singing and dancing through subtler introductions.Footnote 23 He was especially interested in the narrative dimensions of song, saying that numbers should be placed “where they'll help to tell the story,” arguing elsewhere that when a song was over, it should be “as though a scene had taken place rather than a song.”Footnote 24 As he put it, “I had gotten into the mood of wanting things done as legitimately in a musical play as though it were a straight play.”Footnote 25

Harbach complained that critics “usually didn't give a damn whether they liked the book or not because they made fun of the book. The whole theory was to kick the book around.” However, he wrote that his goal was to write “a new kind of musical, in which there was a serious book, which I wanted to be believed.”Footnote 26 Indeed, this desire for “belief” was something that Harbach termed “sincerity,” which he defined as “a good reason for the number when it came.”Footnote 27 Harbach also felt that this approach to musicality had earned him his reputation for fixing troubled shows: “I had gotten known as the greatest play doctor. And my play doctoring depending on getting rhyme and reason into the why and wherefore of the music in the play. To try to find some reason why we should have a number here.”Footnote 28

Harbach sometimes used architectural metaphors to explain how he provided the structure of the musical play. The scenario of the play, he argued, was the “blueprint” that determines whether the house is “a mansion . . . a cute, little lovers’ nest, or . . . a church.” Significantly, he argued, builders don't “start to gather brick and mortar and start to put it up until architects have spent hours and maybe days and months on the plan.” Similarly, once the bookwriters know exactly the structure of the show—which he analogized to “how big the bedrooms are going to be, and where this will be, and so on”Footnote 29—then the musicians can begin work, since

in this scenario you have probably figured out where the windows are going to be. If it's a church, the most beautiful part of a church, we'll say, are the beautiful stained glass windows. There are numbers . . . that have got to be so put where they'll do the most good and where they'll help to tell the story, the atmosphere of the church. . . . But the building, which nobody ever notices, is what went down underneath.Footnote 30

Harbach's argument about dramatic structure thus privileged the scenario—the narrative core—in a way that was truly exceptional for the time. In this metaphor of architectural planning and integrity, Harbach understands the general narrative as the play's foundation, which in turn determines the structural relationship between the elements of the drama and the musical episodes. Significantly, the songs, though seemingly decorative, also have a strong functional purpose: they “help to tell the story” and are thus extensions of the narrative.

The premise that songs should develop from the narrative was remarkable in an era when interpolation—the practice of inserting songs by other writers into shows, of shuffling songs in and out of shows to generate novelty, satisfy performer and audience demands, and sell sheet music—was the dominant practice. An article in a 1908 trade magazine, for example, observed that “It would be impossible to outline the hundreds of interpolations used in productions throughout the country. We can only dwell upon a few of the more important ones, in which the songs interpolated, are beyond question, the genuine song successes of the entire show.” After detailing various interpolated songs then on the boards, the author concludes, “So we might go indefinitely along the line of every production of consequence on the road.”Footnote 31 Even shows by distinguished composers were subject to the practice: one review of Nearly a Hero—also from 1908, the year Harbach debuted on Broadway—reported that “the book is by George Grant, and the music by Reginald de Koven, but neither name appears on the programme, the reason given to those in the know being that both author and composer objected to the alterations and interpolations made during the rehearsals by the stage manager and the star.”Footnote 32 When reviewing shows, newspaper critics regularly urged that songs be interpolated to improve a show's variety or rhythm. By comparison, Harbach's philosophy reveals a much greater commitment to narrative, understanding it as the impulse that must determine every element of the presentation—including, significantly, the music.

He also compared his musical theatre to a living tree. “The old, stereotyped musical,” he said, “hung its numbers on the plot the way you hang balls on a Christmas tree. And the Christmas tree is usually dead.” On the other hand, “Good musical comedy results when the music grows out of the plot, as the living blossoms grow on the branches of a living tree.”Footnote 33 Elsewhere, he used the tree analogy to argue that a play must “have roots for all the motivations of the characters, and a trunk—it's got to be about one subject—and then it blossoms out in leaves, dialogue, or maybe some flowers which become music.” However, above all, these leaves and flowers had to emerge “out of the inside rather than to be like a Christmas tree with a lot of ornaments put on it, which is what happens very often when you try to write a musical play. You kill the play; you kill the tree. And a lot of entertainment on it.”Footnote 34 This organic metaphor again insists that the blossoming songs find their roots in the motivations of the characters, that music and dialogue must be the external manifestations—the motivated expressions—of an internal unity.

These aesthetic ambitions appear all the more striking in the context of 1910 musical comedy, dominated as it was by simple scenarios that invited musical interpolations. In fact, many musical comedies were a hybrid of play and revue, with a cursory narrative accommodating a disjointed assemblage of songs, dances, and routines. In the month before Madame Sherry opened, for example, the Casino Theatre offered Up and Down Broadway, a show that billed itself as “a more or less incoherent resume of current events, theatrical and otherwise,”Footnote 35 with one critic opining that while the show possessed “songs, dances, processions, effects” and “skits,” “the whole . . . is rather poor stuff, and at present scarcely contains sufficient backbone to carry it very far.”Footnote 36 In this context, we can better understand why one reviewer would praise Madame Sherry for having “a plot that runs throughout the three acts and is not lost in vaudeville turns.”Footnote 37

Indeed, in contrast to this world of slapdash construction, Harbach envisioned and later articulated a new vision of musical comedy. What was the source of this revolutionary idea? Harbach gives us a clue when he mentions that “I expected to be a teacher all my life, I suppose. But the kind of work that I'd be doing up there kind of led me into the theater.”Footnote 38 Professors, take heart: a syllabus once changed the course of musical theatre history! So what was Harbach teaching? His field of expertise was the oratorical philosophy of Charles Wesley Emerson, whose “contributions to acting theory in America and to expression in general,” James McTeague writes, “were unique and in many ways prophetic of certain modern ideas concerning acting.”Footnote 39 It was precisely through Harbach's deep training in Emersonian oratory that he developed his theory of dramaturgical structure—and thus, the intellectual pedigree of musical theatre integration can be traced to nineteenth-century philosophies of elocution.

The influence of oratorical culture on Harbach cannot be overstated: he once identified as the highlight of his life his 1895 victory in the distinguished Inter-state Oratorical Association championship in Galesburg, Illinois. Appearing before five judges, including William Jennings Bryan, Harbach delivered “The Hero of Compromise,”Footnote 40 an oration whose success was hailed with a bonfire and the blasting of cannons. “That night, I really struck twelve,” he recalled years later. “All the rest has been just epilogue.”Footnote 41 Harbach's decisive victory followed years of oratorical training. Though he grew up poor, his father arranged—partly through barter—for his children to attend the Collegiate Institute school in Salt Lake City. There, Harbach received a comprehensive liberal arts education that included, among many other subjects, “what was then called ‘oratoricals,’” as he later recollected. “Once a month every pupil had to learn a recitation that he did before the whole school. . . . I liked that because I was pretty good.”Footnote 42 When his father lost his job, he planned to quit school and seek employment, but his principal, a graduate of Knox College, intervened, insisting that he would help Harbach make it to his alma mater, which had a distinguished oratory program. Upon enrolling at Knox, Harbach recalled, “I went in for public speaking, my teacher wanted me to be a minister because I was pretty good at elocution and I remember I wanted to wear a big black hat and a string tie so I could look like William Jennings Bryan, the foremost spellbinder of the time.”Footnote 43 In his years at Knox, he would win numerous prizes in English and declamation, culminating in his triumph at the renowned Inter-state Oratorical Contest.

After graduating, Harbach moved to Whitman College, where he was named the professor of “rhetoric, elocution, and oratory” and taught English literature as well. Among Whitman's 1895 course offerings was Harbach's course in elocution, which, according to the school's catalog, focused on the “psychological development of expression.” Further, another of Harbach's courses is noted as following the “Emersonian system now used in such schools as the Emerson school of oratory, Boston, and the Columbia school of oratory, Chicago.”Footnote 44 Indeed, it is precisely the “psychological development of expression” of the Emersonian system—this interpretive and literary method that Harbach spent years studying and teaching—that leads to his revolutionary work in musical theatre.

The Emersonian method of “psychological development of expression” grew out of the significant nineteenth-century interest in public lectures and recitations, facilitated by the burgeoning movements of the lyceum and the chautauqua. In a time when dramatic productions were sometimes viewed with suspicion, “readers,” as they were often called, presented not only speeches, but also oral interpretations of prose, poetry, and dramatic works. As oratory grew more popular, prominent lecturers began to develop theoretical and pedagogical approaches to elocution.Footnote 45 The “psychological development of expression” refers to a broad trend in elocutionary theory in this period that incorporated popular psychological ideas. Influenced by Charles Darwin and William James, elocutionary theorists—foremost among them Charles Wesley Emerson—moved away from mechanical theories of vocal or gestural production and toward an approach based on the psychological foundations of speech. As Mary Margaret Robb noted, “Under the influence of an interest in psychology, elocution seemed destined to become the ‘art of expression,’ the means of communicating the inner thoughts and feelings.”Footnote 46 In other words, this school of oratorical thought formulated that the mind possesses a coherent inner thought or sensibility that would then be expressed by the body. As Mary A. Blood and Ida Morey Riley write in the introduction to their Psychological Development of Expression, “Expression has to do with the whole man. In this art, thoughts, emotions and purposes form the content, while the body and voice present the form. A noble body and a beautiful voice can only express what the mind can comprehend and feel.”Footnote 47 The idea of subordinating a “noble body” and “beautiful voice” to the mind represents precisely the aesthetic hierarchy that Harbach was cultivating in musical theatre. No longer would a flimsy narrative cede the stage to songs that were about their own delectations—or that conjured emotion, if they did so at all, only through a range of conventional techniques rather than through the psychological motivations of the character. Instead, the joys of voice and body would become servants of a cerebral narrative, the expressions of the “inner thoughts and feelings”; or, as Harbach put it in his tree analogy, all of the branches and flowers of the tree would emanate from the trunk—the “one subject” in a musical comedy—with its roots in the actions of the characters. In a similar vein, Jessie Eldridge Southwick observed that “a person is never graceful without harmonious response of all agents to one impulse.”Footnote 48

Harbach was obviously most influenced by the Emersonian emphasis on the singular and unifying “inner force,” to quote Southwick, that would generate the outer manifestations.Footnote 49 This significance of internal unity is clear in Emerson's insistence that

like every organism, every true work of art has organic unity; it represents a unit of thought, the Whole, made up of essential Parts. Each part is a part of the whole, because in its own way it reflects the whole. The perfect unity of an organism or of a work of art results from the service rendered by each part to every other part.Footnote 50

Understanding expression in this way prompted a revolutionary mode of training speakers, which Harbach practiced in his classroom at Whitman—and which, as he noted, led directly to his work in musical comedy. That Harbach would find Emerson useful outside the domain of oratory is unsurprising, as Renshaw noted that the “principles [of Emerson's Evolution of Expression] were applied not only to oral interpretation, but to voice training, gesture, public speaking, and the allied arts of singing and piano playing as they were taught in the early days of the school.”Footnote 51 The Emersonian model of oral interpretation thus posits an authorial unity, a singularity of vision, an aesthetic harmony—an organicism that has obvious parallels to Harbach's desire to bring all the elements of musical theatre under the sign of narrative. As Emerson wrote, “The pupil must live with his author, see through his eyes, think with his intellect, feel with his heart, and choose with his will, picturing to himself every scene, putting himself in the place of every character described.”Footnote 52

Just as Harbach was troubled by musical numbers imposed without regard for the narrative, numbers that generated their effects through superficial conventions of performance instead of reference to the plot or dramatic experience of the characters, Emerson found the more conventional approaches of formalized voice and gesture deeply problematic, as Southwick noted: “mechanical exercise of the muscles is merely the physical effort to execute the formal dictates of the mind without necessarily experiencing the reality either through imagination or feeling; and people who have followed the school of mechanical technique have often debated the point as to the need of experiencing any emotion in order to effectively move others.” This kind of “superficial representation inhibits and supplants the natural and spontaneous expression of real inner life” and lends itself to the “exhibition of skill in performance with no psychological force behind it but vanity and ambition.”Footnote 53 By contrast, the Emersonian approach emphasized the “development of the inner force as the producer of the outer forms.”Footnote 54 To use Southwick's phraseology, Harbach's musical theatre similarly sought to replace “superficial representation[s]” and the narrative adulterations that performers and producers, through their “vanity and ambition,” visited upon musical comedy.

After teaching the Emersonian method for several years, Harbach ventured to New York City in 1902 to undertake graduate study in English at Columbia University. He planned to complete a dissertation on a topic in which he recalled being “very much interested . . . a sort of a psychological approach to public speaking and reading.”Footnote 55 While he abandoned his plans to write a dissertation on the topic, it was precisely that subject—on which he expounded in the rhetoric classrooms in Walla Walla, Washington—that led to the dramatically ambitious work he pursued on Broadway. The remarkable intellectual history of integration in the American musical theatre, therefore, links the dramatic developments of Harbach, and later Rodgers and Hammerstein, with nineteenth-century public speaking.

Significantly, the rhetoric of “integration” has been called into question in recent years, as scholars have complicated the definition, motivations, and plausibility of integration.Footnote 56 My goal in this essay is not to analyze Harbach's works to suggest that he succeeded or failed at integration, but rather to contribute to the history of musical theatre aesthetics by articulating Harbach's aims, the aesthetic roots of those aims, and the broader cultural context that structured his audience's desire for—and apprehension of—his dramatic innovations. That said, we can get a sense of how Harbach's training influenced his own work by looking at his 1910 musical Madame Sherry, the first for which he wrote both the book and lyrics—the one hailed for having “entertaining elements, cleverly interwoven into a consistent whole.” The curtain opens to reveal a dance studio in which a teacher, Lulu, is giving lessons in “aesthetic dancing.” She sings her lesson:

Indeed, the very first idea introduced in Madame Sherry is precisely the Emersonian idea that the purpose of expression is to externalize an internal thought. Significantly, it is dance—the principal signifier of the bodily pleasures of musical comedy—that is here subordinated to the narrative, as “every little movement” is imbued with an underlying “thought and feeling.” And crucially, the song is introduced diegetically—in other words, explicitly as a song being sung by the dance teacher in the world of the play—fulfilling Harbach's ambition to endow songs with “logical motivation.”

Further, the conceit is developed throughout the piece. After the initial scene with her students in the dance studio, Lulu later pretends to give an individual lesson to Leonard, a man with whom she has been surreptitiously having a romantic liaison. To him, she sings the song, with the same chorus but a fitting verse: “Just let your soul inflame / Your arms and legs grow eloquent / And inner thoughts sublime / Express themselves with temperament / While you are keeping time” (17). The theme is further developed in the play, as its strains are played under two climactic moments. When the orchestra plays it during the climax of the first act—after Edward has been surprised by a visit from his Uncle Theophilus—the newly arrived Yvonne “dances about him in an entrancing way, giving him sweet little caresses, but very innocently. . . . At the climax, he suddenly rises, snatches her in his arms and is about to kiss her. Then watches himself and lets go” (38). During the second act, the pair are once again tiptoeing around their passions, but they are angry at each other. The stage directions indicate that “suddenly mandolins . . . start the refrain of the ‘Love Dance’ [“Every Little Movement”]. She begins to relent. . . . By degrees she dances nearer and nearer until finally she is back of him and repeats the dance which ended Act I except that now her actions have taken on a deeper and more womanly significance” (59). The play also makes a wry reference to the theme, when various farcical circumstances require a character to play the piano—despite not knowing how. As comedic fate would have it, the piano in question turns out to be a player piano. Edward subtly mimes playing the instrument, prompting his uncle to declare, “Such marvelous technique” (50). When Yvonne notes that it's Mendelssohn's “Wedding March” being played, the uncle remarks, “Look at the movement of that body. Every little movement has a meaning all its own” (50).

This kind of internal development, with the song accreting significance through the course of the dramatic action, implicates song within a network of thematic coherence—cultivating the sense that the music is serving a narrative purpose and thereby prompting a different kind of hermeneutic engagement in the audience. (Indeed, one review noted that even the melody alone of “Every Little Movement” becomes a narrative device over the course of the play: “Presently words are not necessary—a few notes and everyone knows that the music is saying: ‘Every little movement has a meaning all its own.’”)Footnote 58 Thus, the two threads of Emersonian elocutionary theory are knitted together in Madame Sherry: the theme of “Every Little Movement”—itself about the psychological development of expression—is repeated and developed throughout the play, giving a sense of internal unity and the sense that we are following a coherent entity in which the various parts relate to a whole, as orchestrated by a single governing vision. It is worth mentioning in this context that while Harbach's innovations still took place within the confines of the absurd farces of the period, a 1910 souvenir program noted that “the concession is general that never before in a libretto have the same captivating elements been so delightfully blended.”Footnote 59

This eagerness for the “delightfully blended” work by Harbach is notable. While opera had a longstanding investment in questions of organicism, the popular musical theatre generally had no such pretense to narrative coherence—since its songs were principally elements of pleasure. This is precisely why interpolation was so prevalent at the time: the primary function of song and dance was to delight audiences through humor, wordplay, and the exhibitionist display of bodies; so songs were added or removed without any consideration of, or relation to, narrative values. However, audiences began to change around 1910, eagerly embracing Harbach's narrative emphasis that posited a different relationship to music. This leads to an important historical question: While Harbach's training in elocutionary theory gave him the conceptual apparatus to imagine a new form of musical storytelling, why did audiences receive his novel approach so warmly?

This transformation in the public's expectations regarding musical narrative can be explained by the broader context of popular entertainment around 1910. To get a sense of the context, we might look to a 1910 newspaper article that announced the program of San José's Theatre José. Promising that “Electra will do stunts with high tension electric currents” and “Herold, man of wonderful physical development, will lift weights and display control of various muscles,” the vaudeville bill also noted that “these numbers will be strengthened by musical selections from the orchestra and motion pictures of the highest standard. Each week an opera of the latest origin will be given. ‘Madame Sherry’ will be the rendition next week.”Footnote 60 Here, we see—on the very same bill—Madame Sherry juxtaposed with motion pictures alongside music from the orchestra. This vaudeville bill merely condenses the broader cultural economy of the time, when theatre and film were often shown as part of the same evening and when the two media were influencing each other. And indeed, the musical accompaniment of film—precisely what preceded Madame Sherry on the San José program—would influence how audiences began to develop new expectations regarding musical storytelling.

This evolution of musical narrative might be said to begin with the “illustrated song,” a protofilmic entertainment that was a staple of turn-of-the-century vaudeville houses—like the one in San José that featured Madame Sherry. Illustrated songs involved an “illustrator” singing a popular ballad, accompanied by a pianist, as exhibitors simultaneously projected a series of colored lantern slides that portrayed the scenes described in the song. Thus, as the pianist and the singer performed the song, audiences would watch as one slide followed another, depicting simplistic tableaux that were visual representations of the lyrics. Ballads were understandably popular, since they told stories that could be easily illustrated in vivid scenes of action.Footnote 61 The ubiquity of this entertainment can be seen in Charles Harris's 1907 comment that “[t]he art of illustrating songs with the stereopticon is now one of the features at all vaudeville performances; in fact, it has become one of the standard attractions.”Footnote 62 It soon became an essential part of cinematic presentations, often staged in alternation with short films.Footnote 63 As John W. Ripley noted, “in 1910, at the peak of the craze, practically every one of the nation's 10,000 movie houses, from the lowly nickelodeons to the plush ten-cent cinema palaces, featured ‘latest illustrated songs.’”Footnote 64 Esther Morgan-Ellis notes that some early nickelodeons were even referred to as “moving picture illustrated song theaters.”Footnote 65

The “illustrated” song insisted on the narrative elements of both musical and visual presentation—and through this narrative primacy, forged a bond between the two media. The greatest evidence for the intensifying fusion of music and narrative are the complaints that arose in the absence of such correspondence. Indeed, the genre fell out of popularity when unskilled exhibitors with a limited library of slides began to present slides that did not match the song being performed. As Charles Harris noted in a 1907 article, “There are many song illustrators who do not take the trouble to make their pictures harmonize with the sentiment of the songs. . . . They illustrate their songs by passing off upon the public a hodge-podge of old engravings which they have picked up in the old print shops and picture stores.”Footnote 66 A few years later, an article in Billboard similarly recalled that “[i]n many instances the words of the song and the pictures were out of harmony, due to the fact that many singers would utilize slides that had no relation to the songs they sang.” However, the same article waxed nostalgic on the power of an illustrated song when executed well: “from our personal viewpoint there has never been a stage presentation that produced the sentimental emotionalism of an apropos song and slide accompaniment by an accomplished singer.”Footnote 67 This is the significant issue: audiences were primed to expect a certain kind of continuity between song and image, and they became increasingly dissatisfied by any disharmony between song and image. The insistent use of music in the service of narrative, the demand that it subordinate the pleasures of performance to narrative revelation, reoriented audiences to listen for the story—a reorientation that became all the more necessary as film emerged.

Indeed, this dynamic of narrative expectation—and frustration—only intensified when silent film eclipsed the illustrated song as the dominant form of visual–musical popular culture—notably, right as Harbach's career was beginning. Of course, as scholar Rick Altman has shown, the so-called silent cinema was never truly silent.Footnote 68 Whether accompanied by a pianist, a pianist and drummer, an organist, an orchestra, or even a mechanical instrument, “silent” films were almost always accompanied by music. Welford Beaton remarked that “[w]e had music with our silent pictures in obedience to a natural law that demanded it, just as a natural law of chemistry demands cabbage with corned beef and beans with pork.”Footnote 69 Early films were generally accompanied by songs—as opposed to generic musical passages meant to convey certain conventional emotions (e.g., anticipation, pathos). This new context for song presentation—building on the illustrated song—reframed how audiences perceived songs. Of course, there was nothing new about a song conveying a story, but in this context the narrative function was not only foregrounded but, in fact, rendered an essential hermeneutic element in experiencing early film. Audiences were forced to attend to the narrative elements of music in order to (try to) make sense of the film presentation.

Far from filling a merely entertaining or diverting role, musical performance served as the very binder of filmic experience, bridging otherwise obvious structural and experiential ruptures in the image itself, editing, and narrative. As film exhibitors deployed music to facilitate a sense of narrative, audiences engaged differently with the narrative potential of music. And as music was grafted onto the images, the temporality of the cinema, with its constant flow, imposed itself on songs—leading songs to be perceived less as lyrical moments that suspended time, and more as narrative devices progressing in time. This new hermeneutics—this new attitude toward popular song that reached spectators in communities across America—transformed the musical expectations of audiences and paved the way for Harbach's dramaturgy, which understood songs precisely as narrative vehicles.

Music thus helped to transform cinema from its episodic beginnings into a complex narrative form, as song was deployed to create or facilitate a sense of narrative continuity, which was lacking or even nonexistent in many early films. As one writer noted in 1909, “many film pieces . . . fail because of some obvious disconnectedness in action.”Footnote 70 When a critic feels the need to exhort filmmakers to do something as seemingly obvious as to “maintain unbroken connection with each preceding scene” in order to keep audiences engaged, it testifies to the narrativic chaos that reigned in those early days.Footnote 71 Some critics, musicians, and exhibitors argued that music could create the continuity otherwise lacking and endow a sense of narrative where none seemed to exist. Defining continuity as “the logical sequence of scenes and action shown in the picture,” organist and author George Tootell wrote that music can work to finesse illogical editing: “The organist must therefore attend to the continuity, and he will find that in most cases, where the continuity of the picture is bad, he can by skilful attention remedy that weakness through his music to a very large extent.”Footnote 72 As artists grappled with how to structure the continuous flow of images, they looked to songs—as stories told through a vehicle of rhythmic integrity—to help support the narrative possibilities of cinematic temporality. This particular deployment of music foregrounded and emphasized the narrative possibility of music to help the action cohere.

Crucially, however, just as audiences judged successful musical accompaniment capable of remediating failed narrative, bad musical accompaniment—the subject of much public discussion—was thought to impede any fledgling attempts at cinematic narrative. To be sure, critics who urged musicians to aid in filmic continuity were usually motivated by what they viewed as the lethal ministrations of hack musicians who accompanied scenes with ill-suited songs. Early film criticism abounds with descriptions of primitive musical accompaniment killing any effect that the burgeoning art form might have been attempting to convey. Many early films were accompanied by musicians who played whatever repertoire they knew or selected, often popular songs or folk songs, and often ones with only marginal, if any, relationship to what was being screened.Footnote 73 As late as 1917, Montiville Morris Hansford reported in the Dramatic Mirror that “[m]any leaders play a whole string of tunes, culled from the catalogues of different publishing houses, without much reference to their character as applied to the film.”Footnote 74 At times, audiences found the choice of song worse than irrelevant—veering into the inappropriate. In 1913, Eugene Ahern quoted his contemporary, William Lord Wright, describing a film: “When Bob, the brave lieutenant who gives his life for his country, is breathing his last on the stricken battlefield, the enlivening strains of ‘Everybody's Doin’ It’ on the pianoforte has quickly sundered the chord of sentiment connecting the audience with the picture screen, and has transformed an appealing scene into incongruous comedy.”Footnote 75 Ahern wryly concluded that the pianist should avoid playing “‘Everybody's Doin’ It’ unless two or more parties die in the same scene.”Footnote 76 Indeed, audiences gradually began to reject popular music played indifferently; one pianist, for example, reported that audiences in the South would not “stand for death, renunciation, or the pathetic to the tune of a popular rag or comic song.”Footnote 77

Sometimes this critique of inappropriate music took the form of mocking its embodiment, the female accompanist.Footnote 78 A 1911 issue of Moving Picture World, for example, quoted a poem by Wilbur D. Nesbit that appeared in the Chicago Post, titled “Lizzie Plays for the Picture”: “Lizzie plays at the nickelo— / Plays for the moving picture show / . . . / With a tum-te-tum and an aching thumb / She keeps the time with her chewing gum, / She chews and chaws without a pause, / With a ragtime twist to her busy jaws / . . . / But Lizzie plays like a grim machine, / And she never thinks what the measures mean.”Footnote 79 Lamenting that “the musical accompaniment to the picture has much room for improvement,” another critic was particularly incensed by a 1911 presentation of The Witch and the Cowboys, during which, despite the film being ripe for dramatic accompaniment, the “lady was contented to play waltzes, two-steps and ‘popular’ stuff all through. The music fits the picture about as well as a shirt would fill a wheelbarrow.”Footnote 80

As audiences grew increasingly intolerant of ill-fitting accompaniment, an endless discourse emerged in public forums on the “appropriate” and “correct” way to align music with stories. This insistence that music must “play to the picture”—in other words, carry along the action—led to a broader valorization of correspondence, of music being judged to amplify the dramatic action.Footnote 81 In Musical America, William C. Carl advised that “people do not attend the ‘movies’ to hear an organ recital. They want the picture reproduced in tone.”Footnote 82 A 1911 article in Moving Picture World similarly advised that “[t]he accepted ‘correct music’ for any motion picture is only that which helps to unfold the plot or tell a story. It may be a medley of classic, operatic, comic, patriotic, or dramatic, but it must be so threaded together that it carries the audience on with the action of the story.”Footnote 83 This philosophy of cinematically “correct music,” like Harbach's own philosophy, insists that music serve a narrative function—and this is precisely the context in which Harbach's ideas took hold.

The widespread dissatisfaction with accompaniments of randomly chosen popular songs prompted musicians and managers to devise elaborate strategies for preparing music, each development aiming to further bind music and story. In 1911, movie palace impresario S. L. Rothapfel received praise for his practice of using an advance screening to “gather the theme and . . . arrange the music for the story and work toward the psychological point in the story.”Footnote 84 As this practice became more common, Joseph Fox argued that the musical director “must have an uncanny sense of fitness so that he can unerringly pick out those compositions which best suit the action on the screen before him. In other words, he must live the emotions of the actors so that he can paint them in musical phrases.”Footnote 85 Implicit in this discourse—with its invocations of “sympathetic emotion”Footnote 86 and “liv[ing] the emotions of the actors”—is an invitation for pianists to participate in a kind of psychological expression not unlike that promulgated in Emersonian Oratorical theory.

Given the demands placed upon pianists, and given the wide range of their talents and skills, the industry began to strategize how to standardize accompaniments. By 1909, Edison and Vitagraph were making suggestions for scoring—if not specific numbers, then at least moods and speeds—and industry columns also emerged whose purpose was to guide pianists in more “appropriate” playing.Footnote 87 While the rhetoric surrounding the accompaniment had initially focused on the appropriateness of a song to a particular situation or moment, broader concerns about organicism began to factor into these columns and debates. George Beynon argued that music needed to be not only appropriate to the story, but also musically consistent across a single film. Some urged a stylistic coherence, avoiding the wanton mixing of classical and popular music,Footnote 88 whereas others advocated, either explicitly or implicitly, for a Wagnerian approach—as for example in Rothapfel's comment that “each big picture . . . must be interpreted musically by a general theme which characterizes the nature of the film play. . . . In the play of Such a Little Queen . . . I caught the atmosphere of the play and variations of the theme accompanied all the telling scenes.”Footnote 89 The Musician magazine similarly wrote that “any musical scene-shifter who takes his job seriously” should aim to “send your folks home with the theme whispered on their breath, and ever afterwards associated in their minds with a certain character in a certain picture.”Footnote 90 However, even as industry magazines were suggesting these elaborate strategies for organicism, the musical accompaniment at many theatres remained quite primitive, prompting the public debates about appropriate music. Indeed, complaints about ill-fitting music continued throughout the silent film era of the 1910s and 1920s—which encompasses most of Harbach's years as a writer. In fact, it was in 1927—nearing the end of the silent era—that Tootell was counseling organists to “attend to the continuity,” so that “where the continuity of the picture is bad, he can . . . remedy that weakness.”Footnote 91

Thus, the illustrated song and silent cinema created the need for “appropriate” music, framing music as a principally narrative element and thereby fueling the hunger for the kind of musical theatre Harbach had imagined. Meanwhile, the emergence of synchronized sound would only accelerate this trend as it focused attention on a different element of musical narrative: the ligaments between music and dialogue. Just as audiences were being introduced to sound film in the late 1920s, Harbach was invited to write films in California. As he recounted years later:

At that particular time pictures that had music in them simply would not go. The minute an audience started to hear them doing music they'd get up and walk out. It was a very peculiar situation. This was about 1928. I'll tell you what had happened. They had done some of the old operettas without in any way revising them or rebuilding them, so that the numbers were properly motivated. You know, in a typical old-fashioned operetta or musical comedy people sit talking, and all of a sudden they start to sing for no [rhyme] or reason. Now they did that in the film, and they simply wouldn't stand for it. And it is ridiculous. That's what has damned, I think, for many years any serious consideration of books in these musical comedies. Because the book couldn't be believed with that kind of treatment.Footnote 92

The “realistic” nature of film, according to Harbach, made audiences reject “old-fashioned musical shows put on the screen . . . with poorly motivated numbers,” since one could not plausibly accept the singing and dancing as “realistic” pursuits of people in everyday life. As he phrased it, “When you see a photograph, you say, well, it must have happened or they couldn't have taken a photograph of it. In other words, in pictures it's a realistic enterprise; you believe what you see in a picture.” In the cinema, he said, “You see only something that's supposed to be happening and they want to believe it. And if you do it in such a way that they can't believe it, they just say, ‘Well, it's ridiculous; I won't sit through it.’ And I think psychologically that's what happened.” He argued that film had brought into stark relief the absurdity of the long-standing conventions of the musical genre: as he put it, “two people talking and then starting to sing and then, what's worse, getting up and doing a funny dance to it” prompted viewers to say, “‘Well, this is all hokum; we won't listen to it.’” He felt that film, which prompted spectators to “want to believe” that what they saw was real, required music to be introduced “in a way that it is believed, really.”Footnote 93 As such, Harbach's interest in modernizing musical comedy anticipated the demands that sound film would place on the distinctly unrealist genre of musical theatre to adopt realist conventions. The earlier debates about silent film accompaniment reoriented songs as narrative vehicles, a realignment that enabled them to be subsumed into the kind of narrative order that Harbach brought to musical comedy. Insisting on the continuity between spoken narrative and musical narrative, Harbach also advocated for subtle diegetic introductions that would mute the most egregiously unrealistic moment of bursting into song—a moment whose absurdity would be brought into relief by the photographic realism of film. Harbach's own Hollywood career was short-lived, and his musical episodes, ironically, were removed during editing. As he lamented, “Having been built for music to sustain the interest and many of the turning points of the story, [the film with the musical episodes excised] was a pretty slim affair.”Footnote 94 However, even if Harbach's foray into Hollywood was unsuccessful, he clearly felt that the cinematic demand for realism affected how audiences approached musical theatre.

In 1931, after returning to New York, Harbach wrote The Cat and the Fiddle, a stage musical that was the culmination of his career-long quest to develop a modern musical theatre. In the context of 1931—right as Harbach recalls film audiences rejecting the implausible conventions of musical theatre—The Cat and the Fiddle avoided the kinds of generic incongruity rendered obvious by the emergence of film. Harbach considered this show as a pinnacle of musical theatre construction, deeming its technique “modern-play-with-music.” As he recalled years later, “I said, ‘I'm going to see if I can't write a play in which the music is there because it's got to be there. It isn't the result of musical comedy technique or operetta technique. This story could not be told without the music.’” For example, “the first number was a street singer in Brussels—a song peddler would meet you and want you to buy something, or he would illustrate it by singing a touch of one of the songs; and that was the motivation for the first song.”Footnote 95 In this piece, “no number was introduced just for the sake of having a number,” and since its main characters were composers, “the people can make music logically.”Footnote 96

Harbach recalled that The Cat and the Fiddle interested its composer, Jerome Kern, “precisely because it was believable and suitable for music that wouldn't kill the story by popping out at the wrong time.”Footnote 97 In one review, a critic championed the “up-to-date musical play,” noting that “[t]here is no chorus, but there is a definite well-constructed plot in which songs and dances occur only when and as they would in real life.”Footnote 98 In writing a musical in which song and dance take place “as they would in real life,” Harbach inadvertently reveals one principle involved in his new form of storytelling: to have people sing and dance as in real life generally involves the “real world” of those already singing and dancing, often in theatrical contexts. Thus, the ostensible desire for realism paradoxically promotes only more theatricality. And indeed, the two main characters of The Cat and the Fiddle are of the theatrical world: two composers who fall for each other, one of whom expresses his feelings in the songs that he writes.

And this show—this culmination of his life's work, this “new kind of piece”—what should it be about? The plot of The Cat and the Fiddle focuses on nothing less than the dangers of interpolation. The show begins in Brussels, where American songwriter Shirley Sheridan encounters Victor Florescue, a Romanian composer of symphonies now working on “something a little more commercial” that he hopes to sell as a stage work. They flirt, and Victor promises to write her letters in care of general delivery. However, due to a misunderstanding, the letters are not delivered, and each believes that the other has lost interest. Meanwhile, Victor, heartbroken by Shirley, expresses his grief in his stage work, The Passionate Pilgrim. As Victor previews some of his music, one of his producers expresses concern that the piece is too “somber” and needs “lightening”—at which point strains of jazz piano waft in from a nearby apartment. Getting into the beat, the producer says, “That's what we want . . . something rhythmic and dancy! Can't you give us something like that?” Victor, indignant, replies that “I write music, I cannot write trash!”Footnote 99 Unbeknownst to Victor, though, the musician in the nearby apartment is Shirley Sheridan. Shirley is excited to discover that the producer is interested in her music—but horrified to discover that he “only want[s] a few numbers” to “lighten up” another composer's piece. Shirley declines, noting that she “know(s) how a composer feels about his score,” adding that “I'd just feel sick if somebody wanted to re-write my stuff.” The producer tries to calm her by noting that it's “merely two or three interpolations,” prompting her outrage: “Interpolations in a consistent opera! Horrible!” Despite the producer's excuse that it's “a sort of Revue”—thereby aligning Victor's piece with the popular musical theatre—Shirley steadfastly refuses, but her brother overrides her. When Victor hears the music to be incorporated into his score, he quakes with rage: “This trash in my play? Never!”Footnote 100 Despite Victor's insults, Shirley still honors his genius and repeatedly urges the producer not to interfere with his work. Eventually they reconcile, as Shirley shows him how a simple change in the accompaniment might make his number brighter—prompting both a romantic and musical détente that will lead to Victor's rewriting the ending of his play.

In writing a musical that vilified interpolations, Harbach certainly succeeded in writing a play about real life, since his entire aesthetic philosophy worked against the prevailing trend of interpolation. Ironically, though, Harbach—like almost everyone else of this era, including Jerome Kern—began his career by trying to interpolate numbers into other shows. Years later, Harbach expressed gratitude that he failed at this brief aspiration: “Thank God I never did get one in, because I think that's one of the measliest things that a man can do.”Footnote 101 And he would spend the rest of his career working to strengthen musical theatre into a genre whose robust narrative structures revealed the inadequacy and undesirability of interpolated musical numbers. Significantly, the fact that the anxiety of interpolation could be itself be comprehensible as the subject of popular culture testifies to how widespread these concerns were among the public at the time Harbach was writing. Indeed, as audiences were entertained by Victor's fears, they would have drawn not only on caricatures of composers’ egos, but also on the widespread discourse surrounding interpolations and musical narrative that had been circulating about film and theatre for more than a quarter century. And it was precisely the discontent surrounding filmic accompaniment—and the discourses generated by this discontent—that prepared mass audiences to appreciate, and to desire, Harbach's novel form of theatrical storytelling.

Thus, Otto Harbach's revolutionary work in musical theatre was a product of the elocutionary world in which he was trained, received in a cinematic context of widespread concern about musical storytelling. And so the history of “integration” in musical theatre finds its roots in the Emersonian traditions of the nineteenth century and the cinematic innovations of the dawn of the twentieth. This sense that modern musical theatre spectatorship has been shaped by cinematic experience certainly inflects the frequent laments about Hollywood's infiltration of Broadway today, encapsulated in a line by Peter Marks: “Gaze up at the marquees in the theater district, and you might think you've stumbled into a film festival.”Footnote 102 Writing in the New York Times in 2002, Marks goes on to note the incredible number of musicals based on films that were either on or en route to Broadway at the time, writing that “[i]n many ways, Broadway's extraordinary embrace of the movies is not a sign of strength,” and complaining that “[t]o some in the theater business, the Broadway musical is becoming an appendage of Hollywood.”Footnote 103 As we have seen, though, this has been true now for more than a century.

In 1953, Oscar Hammerstein II wrote in the New York Times of the importance of the “framework of a well conceived and solidly built book.”Footnote 104 He concluded by writing:

My friend and teacher, Otto Harbach, once explained the situation very clearly to me. He likened the elements of acting and dancing and all the other parts of a musical play to the ingredients that go to make a fire—logs, kindling, matches, a good fireplace, etc. All these ingredients, he said, are necessary, but they won't make a good fire unless they are properly assembled. The logs must be placed on top of the other so that there is provision for draught. They must be put in the right place in relation to the chimney in the fireplace. The kindling must be arranged properly under the logs. When everything works—when the logs crackle and the bark sputters, when the blue and gold flame waves and flies toward the chimney and sends out warmth and good feeling to cheer a room full of people, it is because some plodding, perhaps not very brilliant fellow knew how to put one log on top of another in just the right way.Footnote 105

And it was Otto Harbach who first lit the flame in 1910, when he brought the secrets of his “oratoricals” to the Broadway stage. That flame, which burns brightly even today in the heart of everyone who feels the transcendent joy when book and music meet, is a lovely flame that never dies.

Bradley Rogers is Lecturer in Musical Theatre and Performance at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he focuses on musical theatre, gender and sexuality, and theoretical approaches to performance. His book, The Song Is You: Musical Theatre and the Politics of Bursting into Song and Dance (University of Iowa Press, 2020), was a Finalist for the George Freedley Memorial Award and received an Honorable Mention for the Barnard Hewitt Award. He is presently writing a biography of Otto Harbach.