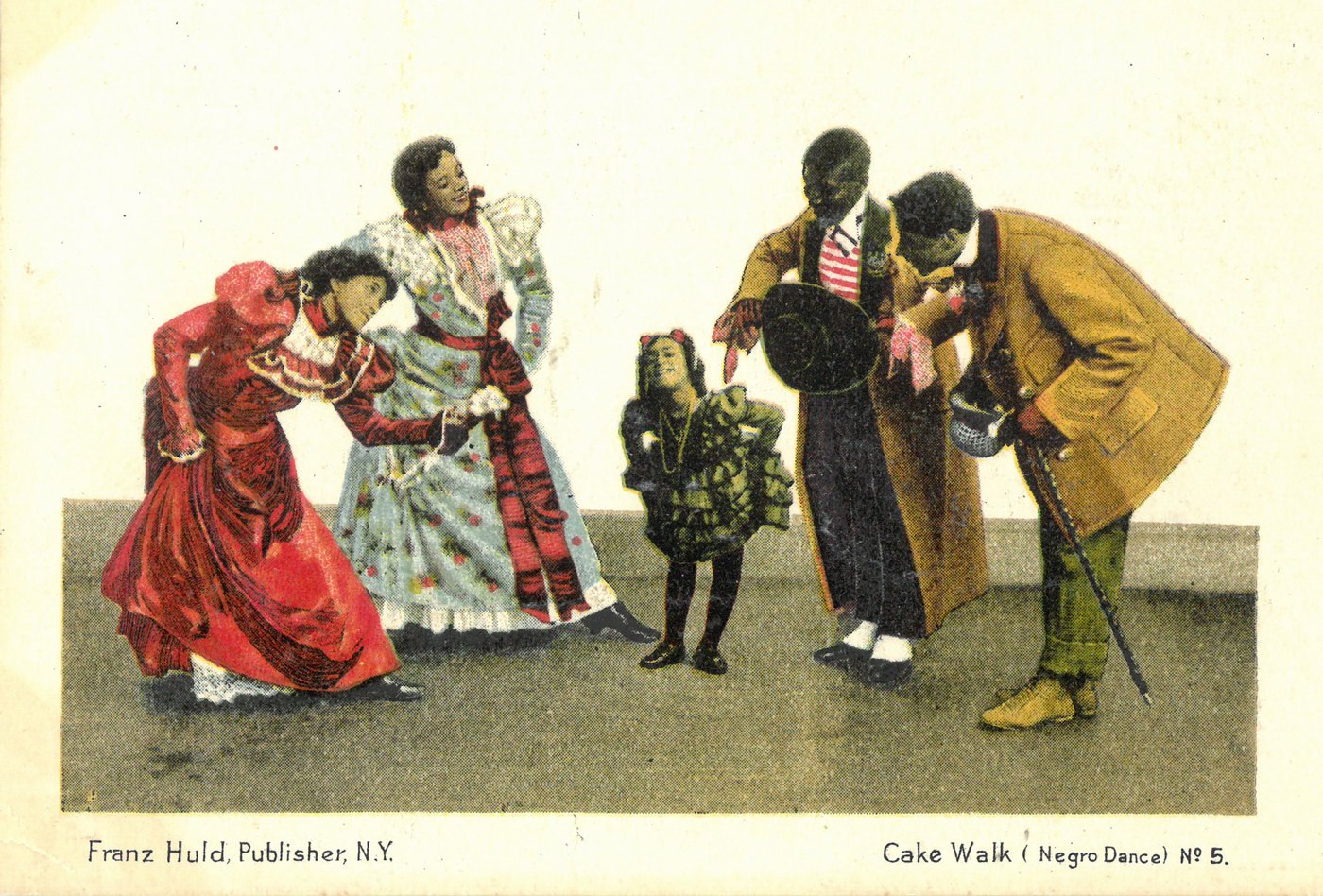

On 22 August 1897, the American Woman's Home Journal published seven photographs of “The Cake Walk as It Is Done by Genuine Negroes” in which “Williams and Walker Show How the Real Thing Is Done before the Journal Camera.”Footnote 1 In this series, the African American stars Bert Williams, George Walker, Belle Davis, and Stella Wiley perform their popular cake walk act with situational humor in medias res before an unknown photographer in a nondescript space.Footnote 2 Among the seven selected poses, one intriguing photograph in the lower right-hand corner depicts the encircled dancers gazing down upon an empty space in the center.Footnote 3 The subject of their gaze becomes apparent when comparing the magazine images with the seven “Post Cards” Franz Huld published as part of his “Cake Walk/Negro Dance” series around 1901.Footnote 4 Although the performers’ poses are the same, the postcard includes extra space between Wiley and Walker to feature a young girl of mixed racial heritage bending forward while hiking the back of her dress with her smiling face proudly held high (Fig. 1). If standing upright, she appears to be less than four feet tall and perhaps five to nine years of age. Given the obscure date and location of her photo shoot, her birth year could range anywhere from the mid-1880s to the early 1890s. Like Thomas F. DeFrantz, an African American dance theorist who gazes upon two 1920s photographs of other dancing girls, my gaze leads me to wonder about her identity, how she met and socialized with these four dancers, and whether she pursued a theatrical career.Footnote 5

Figure 1. (L to R) Belle Davis, Stella Wiley, the girl, George Walker, and Bert Williams; ca. 1901. Purchased by author, 26 August 2017.

Despite my extensive investigations, the actual identity of the cake walk photo girl remains an enigma. Her very anonymity encapsulates the dilemma that theatre and performance studies scholars face when seeking to recuperate the embodied personalities and migratory lives of performing girls.Footnote 6 As but one instance of visual culture, her body represents a uniquely positive depiction of a young cake walker, unlike caricatured illustrations of cake walkers that proliferated on sheet-music covers and other postcards, and may very well predate those of other dancing girls.Footnote 7 Moreover, I argue that the pride and pleasure she exhibits as the center of attention among four exceptional dancers aptly symbolizes the importance of black girls who performed during a pioneering period in the development of African American musical theatre from the 1890s through the 1910s. Some girls achieved national, as well as international, recognition as celebrated dancers, singers, and actresses over their adolescent and adult careers. Others earned recognition in name only in managers’ rosters and black critics’ brief newspaper reviews. Like the cake walk photo girl, most remain as anonymous footnotes whose names, bodies, and identities may never be known in the annals of musical theatre history.

In this essay, I imagine the possible migrations of the cake walk photo girl by explaining how and why black girls entered show business via multiple circuitous routes both within and away from their original birth places as an alternative occupation to domesticated lives. Although black girls were expected to carry out their mothers’ aspirations for racial progress as wives and mothers, as Nazera Sadiq Wright uncovers, musically inclined girls challenged these domestic agendas by pursuing avenues of personal and racial uplift through performance.Footnote 8 Upon discovering the joys of bodily self-expression at young ages, they took advantage of various opportunities in their immediate environments and utilized multiple strategies to achieve their respective dreams as dancers and singers. Given the breadth of performative contexts, I limit my selection of girls to their direct or potential associations with Belle Davis, Stella Wiley, Bert Williams, and George Walker, as well as Walker's accomplished wife, Aida Overton Walker, and connect a few missing dots in their respective migrations over a fifteen-year period. Alongside their theatrical associates, these five prominent performers, born in the 1870s and 1880, mentored innumerable girls and young women as they shifted African American musical theatre away from its racist roots in minstrelsy.

This interdisciplinary project builds upon and extends the biographical foundations and critical analyses of black performance historiographers and theorists who situate the imperatives of black bodies and aesthetic sensibilities within visual culture across migratory roots and routes.Footnote 9 Similar to Jayna Brown's critical methodology,Footnote 10 I offer a different performance genealogy of black girls, based on verified or guesstimated birth years, as cake walking dancers in touring companies, vaudevillian “picks” (short for “pickaninnies”), and chorus girls in Williams and Walker's productions. Collectively, these three overlapping categories of performance reveal how and why two cohorts of girls took their first performative steps and pursued multiple strategies of freedom and survival during the oppressive Jim Crow era of segregation. To visualize performing girls within “a new paradigm for beauty” established by emerging black newspapers in the 1890s, as photography historian Deborah Willis documents,Footnote 11 I provide limited examples herein and source the earliest known photographs of young theatrical women to suggest their respective personalities. By uncovering, tracing, and uniting what little is known of each girl's entrance into theatre, this emergent reconstruction explains how and why girls strategized their careers via three musical routes and challenged domestic agendas of black girlhood through performance. As a consequence, I argue that their concerted efforts led African American musical theatre toward the intricacies of modern tap dancing and syncopated ragtime songs.

Cake walk Dancers

The physical and musical roots of the cake walk have been traced back to nineteenth-century Southern plantations as well as several African cultures. After observing the quadrilles and grand marches of the white gentry, couples held in bondage released their oppressed frustrations by mocking and exaggerating these dances while competing for a cake. Dressed in hand-me-down finery, they strutted and pranced in “chalk-walk lines” with arched backs, high kicks, and pointed toes to the syncopated rhythms of banjos, fiddles, and drums. Not unsurprisingly, the white gentry mistook this subversive satire as simply stereotypical expressions of “Negro fondness” for dancing and music. White minstrels in blackface subsequently appropriated and distorted this “walk-around” as a double-edged irony of white satire of black folk caricatures of white aristocratic customs. Cake walk performances at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia sealed plantation stereotypes further to wider audiences, and competitive cake walk events spread to other cities throughout the 1880s.Footnote 12

As more African Americans migrated to northern cities in the 1890s, the popularity of the cake walk exploded and the dance crossed racial, class, and transnational boundaries, even as upper- and middle-class blacks debated its worth as a viable means of racial uplift.Footnote 13 Given white producers’ profit-driven, plantation and minstrel mythologies, black managers, such as Sam Lucas, Billy McClain, and Bob Cole, staged and toured cake walk acts in several, long-running, indoor or outdoor performances that included The Creole Show (1890–7), South before the War (1892–8), Black America (1895), The Octoroons (1895–1900), Oriental America (1896–9), Darkest America (1896–8), and Black Patti's Troubadours (1896–1915).Footnote 14 The improvisational experimentation and stylistic virtuosity of dancers intensified as national cake walk championships were held annually at Madison Square Garden beginning in 1892, in which throngs of “spectators went fairly wild over the great exhibition of style, elegance, and grace.”Footnote 15 Creole Show dancers Charles E. Johnson and Dora Dean, billed as the “King and Queen of Colored Aristocracy,” modernized the cake walk with elegant sophistication in fashionable evening attire, as did 1897 cake walk champions Billy and Willie Farrell. Throughout this period, it was not uncommon for children to participate in local cake walks and to travel with companies. For instance, after leaving the Creole and South before the War companies, little Mamie Payne joined her parents, Major Ben F. and Mrs. Susie Payne, in 1893 in Slavery Days, one of many imitative productions.Footnote 16

Beginning in 1890, The Creole Show, in particular, opened up new and advantageous performance opportunities for the cohort of African American girls born in the 1870s by featuring female minstrels and choruses. Despite its controversial cake walk dances and minstrel mythologies, this innovative show and its imitators marked a significant transition between all-male minstrelsy and vaudevillian revues.Footnote 17 As key representatives of the 1870s cohort, Belle Davis (b. 1874) and Stella Wiley (d. 1930) honed their experiential talents in this show and other companies with numerous others, known only by their names, women whose concomitant birth years and obituaries remain elusive.Footnote 18 Unfortunately, we know nothing of their girlhoods or whether they had unreported children. As twenty-something performers, they both appeared in Sam T. Jack's Creole Burlesque Company during the fall of 1894, as evidenced by Jack's August roster that included “Harry Singleton and wife, Belle Davis,” as well as Stella Wiley and Bob Cole, her “terpsichorean” partner and future husband.Footnote 19 However, during the first half of 1895, Wiley performed with Cole at Worth's Museum in New York; and Davis and Singleton apparently parted ways in March when Singleton joined Cleveland's minstrels.Footnote 20 After completing the Creole season, Davis reportedly summered in Brooklyn at Manhattan Beach, while Singleton portrayed Old Black Joe in Black America with child cake walkers at Ambrose Park in South Brooklyn before leaving New York with the Suwanee River company in August.Footnote 21

Ironically, the cake walk phenomenon had achieved further national and international circulation during the summer of 1893 in Chicago when the World's Columbian Exposition, designed to showcase purified images of forty-six nations, became a prominent venue for showcasing several African diaspora performances and thereby laid the sociopolitical foundations for subsequent African American artistic movements.Footnote 22 While the “White City” of Chicago, named for its white buildings at the Columbian Exposition, was awash in cake walking contests and performances at several variety venues, Williams and Walker arrived there in September 1895 after performing out West.Footnote 23 Based on published reports of the four dancers’ whereabouts, they may have first met Wiley, Cole, and Davis, as well as Jesse Shipp and Billy Johnson, here in February and March 1896, when their respective companies were competing for performers in new acts.Footnote 24 While Shipp recalled their audition and trial engagement in Cole and Johnson's troupe “The Six Octoroons,” the four dancers could have also performed “Rehearsing for the Coon's Cake Walk” with Isham's OctoroonsFootnote 25—along with any of the following girls residing in Chicago at this time.

The girlhood of Ida Forsyne (b. 1883), an internationally acclaimed dancer, offers the most detailed explanation of how girls took advantage of local dancing opportunities to initiate and expand their performance networks. While living with her mother above a Chicago saloon, Forsyne recalled learning her “first real [dance] steps” from the sporting-house pianist downstairs and picking up pennies and dimes while dancing in front of the candy store and at house-rent parties. At age ten, she joined the Creole company in their cake walks during the 1893 Columbian Exposition for two months that summer for twenty-five cents a day, adding “We went around in a wagon with a ragtime band to drum up trade.”Footnote 26 To further expand her enthusiasm for buck-and-wing minstrel dancing, she also haunted the Alhambra Theatre to watch rehearsals of The Coontown 400 and South before the War. At age fourteen, she ran away from home to sing and dance with a tab show (a short, tabloid version of musical acts), and when stranded out West, made her way back home singing on trains with an anonymous five-year-old boy who passed the hat for their expenses along the way. Two years later, she joined Black Patti's Troubadours as its youngest member for $15 a week, singing a “coon” lullaby of which she said, “no one thought of objecting in those days,” and winning the show's cake walk contests with a partner for seven straight nights. With her “legomania” (rubber-legged eccentric dancing) talents, Forsyne later became “the cakewalking toast of Russia.”Footnote 27

The ongoing ubiquity of minstrelsy also served as another interrelated pathway for girls to dance in local or touring troupes. Forsyne's equally accomplished cousin, Ollie Burgoyne (ca. 1885), reportedly danced in minstrel shows at age six and also extended her prominent career on an international scale.Footnote 28 In August 1896, she joined Isham's Oriental America of female minstrels with Belle Davis, Pearl and Carrie Meredith, and their maternal chaperone, Laura Meredith.Footnote 29 Another rising star and South Side Chicago girl, little Lottie Grady (b. 1889), may have first gained experience with Trux's Black 400 touring company before earning praise back home for her “clever singing, graceful dancing and charming simplicity” at age twelve.Footnote 30 After playing vaudeville as a sixteen-year-old chorus girl at the Pekin Theatre, she cultivated her acting skills as the Pekin's leading lady under the tutelage of J. Ed Green.Footnote 31 This multitalented soubrette went on to costar with Bert Williams in Mr. Lode of Koal in 1909 and with Bob Cole in William Foster's 1912 film, The Railroad Porter.Footnote 32

As girls made inroads through female minstrelsy and cake walking choruses around the country, Williams and Walker billed themselves as “Two Real Coons” at Koster and Bial's Music Hall in New York City beginning in early November 1896. It was around this time that their manager, William McConnell, purportedly “saw the cake walking pictures in a show window. He decided to produce the dance on the stage, but to get the value of the publicity of the tobacco industry he insisted on the same costumes and the same girls.”Footnote 33 Indeed, in late November, Williams and Walker added “two, coffee-colored ladies dressed in yellow” to a cake walk finale, and they also satirized the “Colored 400” with a larger contingent of cake walkers while singing Cole and Johnson's “The Black 400's Ball” through March 1897.Footnote 34

Davis and Wiley may or may not have been available for Williams and Walker's cake walks in late November because both were reportedly out of town touring in their respective companies.Footnote 35 However, Wiley had appeared at New York's Star Theatre in early November when Black Patti's Troubadours staged Bob Cole's opening forty-minute sketch, “At Jolly Coon-ey Island.”Footnote 36 According to this program, Wiley sang “Belle of Avenue A” and sixteen-year-old Aida Overton sang “4-11-44” with Cole, Billy Johnson, Henry Wise, and Sadie De Wolf. Overton also sang “The Three Little Kinkies” with Misses Lena Wise and Maggie Davis, the latter the seventeen-year-old wife of Charles Davis, an acrobatic dancer who partnered with Ed Goggin.Footnote 37

Like Forsyne, Ada (later stage spelling, Aida) Overton (b. 1880) began her renowned career by dancing along New York City streets with her friends Pauline and Clara Freeman while following a hurdy-gurdy man, who earned more money with their participation.Footnote 38 Unlike Forsyne's mother, Ada's dressmaking mother, Mrs. Pauline Reed, enrolled Ada in Mrs. Thorpe's school of physical culture, where she danced the Highland fling and sang “Swinging in the Grape Vine,” suggesting another, perhaps more middle-class, route into performance.Footnote 39 After making her professional debut in 1896 with the Freeman sisters and honing her talents further with Wiley during the Octoroons’ 1897–8 season,Footnote 40 Overton sang, danced, and choreographed Williams and Walker's productions beginning in September 1898 and married Walker in June 1899.

Given Williams and Walker's cake walking reputations, Will Marion Cook initiated a plan for them to star in his new “Negro operetta,” Clorindy; or, The Origin of the Cake Walk, an hourlong entertainment that also needed child performers.Footnote 41 So, upon returning home to Lawrence, Kansas, in July 1897, George “Nash” Walker called upon Reverend Albery A. and Caddie Whitman and their “four angel children,” Mabel, Ollie, Essie, and Alberta.Footnote 42 The first three siblings had begun singing in 1889, and their father had taught them the double shuffle, presumably for exercise.Footnote 43 At age ten, Essie won a singing prize in Kansas City, and she remembered cooking greens for Walker, whom she considered “the greatest strutter of them all.”Footnote 44 In a 1918 interview, Mabel recalled that Walker “desired to be a sponsor for us on a trip to New York for the purpose of starting us on our professional career, but was met with parental objection. Myself, Essie, and Alberta received our rudimentary education in our home town, and were then sent to Boston, Mass., where we attended the New England Conservatory of Music,” and subsequently moved to Atlanta.Footnote 45 Whether Walker found or took one or more other girls back with him to New York as another performance route for girls remains unknown.

Sometime before or after Walker's sojourn to Lawrence, the four dancers may have repeated their 1896 cake walk act “before the [New York] Journal camera” for publication in August.Footnote 46 This photo session may have included Ida Gwathmey (b. 1888), a Virginia-born girl who reportedly studied dancing in New York “[a]t an early age,” perhaps at Hallie Anderson's school on 53rd Street with Rufus Greenlee and Thaddeus Drayton, who greatly admired Walker's struts.Footnote 47 Her father may have been V. M. Gwathmey, a Richmond merchant of tobacco and cigars, suggesting another middle-class dancing route away from home and making her potential identity as the cake walk photo girl all the more tantalizing (Fig. 2).Footnote 48 Although nothing further is known of Gwathmey's childhood or her marriage to Charles H. Anderson, a “popular Harlem dance master,” she performed in Anita Bush's stock company in 1916 and organized her own Players in 1928.Footnote 49

Figure 2. Ida Gwathmey Anderson, in The Crisis 15.2 (December 1917), 82. Courtesy of the Modernist Journals Project, Brown and Tulsa Universities, at www.modjourn.org/render.php?id=1292429023445375&view=mjp_object.

Anderson's future colleague, Abbie Mitchell (b. 1886), also began her professional career in New York, one year after the Journal photo session during the summer of 1898 at age twelve. Despite her aunt's protests that she “was only a child and nice girls didn't go on the stage!” she auditioned for and sang in Clorindy for $35 a week during its sensational run at the Casino Roof Garden starring Belle Davis and Ernest Hogan. Upon returning to school in Baltimore, Will Marion Cook persuaded Mitchell's family to allow her to rejoin the company with Pearl, Carrie, and Mrs. Meredith.Footnote 50 When Davis left the company, Mitchell assumed a leading role with Lottie Thompson, Bert Williams's future wife, in Williams and Walker's Senegambian Carnival, an expanded version of Clorindy. At age fourteen, she married Cook (seventeen years her senior), perhaps to assuage her family as a respectable woman. After giving birth to two children, she performed in three more Williams and Walker's productions before divorcing Cook in 1908 and continuing a multifaceted and long-lived career.Footnote 51

At this juncture, any number of girls had made their way to the performance capital of New York City upon leaving their hometowns with or without their parents or guardians. From mid-August to early September 1898, the four dancers could have posed with other potential girls for another speculative photo session, specifically for Franz Huld in New York. While Williams and Walker played Keith's Union Square Theatre, Davis and Wiley opened Isham's Octoroons with a newly conceived cake walk at Miner's Eighth Avenue Theatre that included Sadie Britton.Footnote 52 After closing Clorindy, Pearl and Carrie Meredith performed a sketch with Tom Logan at the Casino Roof Garden just before leaving to join Black Patti's Troubadours in Plainfield, New Jersey.Footnote 53 By early September, twelve-year-old buck dancer Muriel Ringgold (b. 1886) proved herself a sensational hit with the Troubadours under Ernest Hogan's stage management.Footnote 54 It was also during this auspicious summer that Belle Davis first introduced “her pickaninnies” and thereby contributed to a three-decade-long “pick” phenomenon.

Anonymous “Picks”

From 1894 through the 1920s, a new set of wildly popular “pickaninny” acts arose in multiple variety shows, among black and white performers alike, as an ongoing extension of cake walk dances and plantation mythologies staged in all-black companies. Before the Civil War, Harriet Beecher Stowe's characterization of Topsy as “a little Negro girl, about eight or nine years of age” unwittingly christened “pickaninny” imagery and reactivated virulent stereotypes concerning children's lives on plantations throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 55 Although Caroline Howard established the convention of much older white actresses portraying Topsy in blackface for thirty-five years, African American girls or young women, such as Miss Hutchins and Emma Louise Hyers, also characterized Topsy in the 1870s and 1880s.Footnote 56

During the early 1890s, as black managers incorporated numerous, anonymous youngsters in their cake walk acts, visualizations of children dancing in black musical choruses with adults extended racist “pickaninny” imagery and further reinforced contentious plantation mythologies of black domestication. In 1894, former Creole company couples, such as Irving and Sadie Jones, began to introduce youngsters in their minstrel acts. Al and Mamie Anderson publicized “four little pickaninnies” in their “Corn Bread” act, and their colleague, Jerry Mills, also presented several at Worth's Museum.Footnote 57 After her husband's death, Madame Susie Payne promoted her anonymous “picks” with her daughter, Mamie.Footnote 58 Although child performers seldom earned name recognition in public notices, Cole and Johnson advertised and named “Sadie Robinson and Little Dottie” for their New York performances of A Trip to Coontown in April 1898.Footnote 59 African American boys also played brass instruments in countless “pickaninny” bands in street parades and annual performances of In Old Kentucky at New York's Academy of Music (1893–1915).Footnote 60

The concept of specialty “pick” acts appears to have been sparked in May 1894 when Lederer and Canary promoted a petite, nineteen-year-old white woman, “Lucy Daly and her pickaninny band,” in The Passing Show, “a topical extravaganza” that burlesqued others’ acts.Footnote 61 Much like black-faced white minstrels who satirized cake walks, Daly parodied black female minstrels in blackface with young black dancers. Thomas Edison's 1894 film of Daly's act not only provides a rare exhibition of buck-and-wing dancing but also reveals that three of her eleven “picks” were actually young men.Footnote 62 However, the fact that the infamous Gerry Society, in keeping with New York's child actor laws, forbade her “picks” from performing in their costumes at a Sunday benefit suggests that the other anonymous children were under age sixteen.Footnote 63

Legal-minded managers needed to consider age-sixteen restrictions in their hiring practices, even though girls may have lied about their ages. For Black Patti's Troubadours, managers Voelckel and Nolan appear to have abided by this law when they hired Ada Overton, the Freeman Sisters, and Ida Forsyne for their New York City shows and the Meredith Sisters and Muriel Ringgold for tours outside New York state. To subvert child actor laws, adolescent girls, like Abbie Mitchell and Maggie Davis, often married young to work in New York and across multiple states as reputable actresses.

While some critics considered the employment of underaged “picks” exploitative child labor, their variety sketches with black or white female “coon shouters” and “coon” lullabies “just grew” like Topsy into a long-running rage for several reasons. As old vaudevillians recalled, single, most often white, women would sing a few songs and then bring out two or a half dozen little “Negro kids that really could sing and dance” in their act as “‘insurance’ … for a ‘sock’ finish” that never flopped among white and black audiences alike.Footnote 64 Tom Fletcher added,

The kids didn't just supply the atmosphere but were clever performers. The activity gave them a chance both to get rid of their extra energy and to further their ambitions as well as be a [financial] help to their parents. The youngsters were well cared for, being kept well dressed both in the theater and outside. The top ones who were with the female stars … became big names themselves in the amusement field.Footnote 65

Indeed, although children did not reap managers’ one-way profits, girls asserted their self-determined agency by utilizing these opportunistic means of entering show business, earning their own money, and traveling across the country and around the world as a viable alternative to lower-class domestic occupations.Footnote 66

Paradoxically, these representations of black girlhood onstage conceptualized girls as women's domesticated children, literally their hired help, even though white and black female vaudevillians alike trained them otherwise as more middle-class performers and generated their professional theatrical careers. Among the many white women who followed Daly's footsteps, it is Josephine Gassman about whom we have the most detailed account, including how she hired and trained girls and represented them as her supposed offspring while portraying a “Mammy” in blackface. After singing at Keith's Union Square Theatre, where Williams and Walker also appeared in August 1897, Gassman billed herself as “The Belle of Blackville,” initially with a Southern boy, who left, and then with three Northern boys who danced while she sang “Mammy's Little Pumpkin Colored Coons,” authored by black composers George Hillman and Sidney Perrin.Footnote 67 Six months later, she returned to Keith's with two siblings, six-year-old Ruth and four-year-old Frederick Walker, whom she reportedly had found “living in squalor” in Chicago. Gassman offered their mother, Ella, “a weekly allowance in recompense for their use,” bought them new clothes, and taught them cake walking for their debut at Chicago's Opera House, where spectators deluged them with money. In New York, she sang “Enjoy Yourselves” as “coquettish” Ruth flirted with her “swaggering” brother, who bowed gallantly and tied her shoelace while bent on one knee.Footnote 68 Despite earning over $7 from the stage, the Gerry Society cut short their six-week run, forcing their act to play in other states (Fig. 3).Footnote 69

Figure 3. Fredy (Frederick) and Rudy (Ruth) Walker posing with Josephine Gassman. Courtesy of Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University, at http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/105/127.

One year later in St. Louis, Gassman discovered another youngster, Irene Gibbons, whose mother consented to renaming and taking her three-year-old daughter on the road across the US, Europe, and Australia from 1899 through 1917.Footnote 70 At age six, little Eva Taylor posed between two unnamed children for souvenir photographs handed out at matinees in Los Angeles.Footnote 71 By 1917, “Phina and Company” included three “fully grown” girls, possibly Taylor, Edith Spencer, and Ruth Good, as well as pianist Walter Hall and comedian Bill Bailey, who also edified prisoners at Blackwell's Island that Thanksgiving.Footnote 72 After Taylor ran away at age twenty-six, little Katherine Howard impersonated others’ singing of various songs and eulogized Teddy Roosevelt.Footnote 73 Not until 1921 did these company members finally gain the name recognition they deserved.Footnote 74

In addition to Taylor and Spencer, who achieved lauded musical reputations as adults, two other noteworthy girls also initiated their distinguished careers by first laboring as other white women's “picks.” Like Gassman, Pauline Hall (aka Bonita) used a brown pigment rather than burnt cork to darken her white skin while performing with her anonymous children, billed as “African” or “Cuban midgets.” Sometime between 1901 and 1905, she hired Florence Mills, who had triumphed at age eight singing “Hannah from Savannah,” Aida Overton Walker's signature song from The Sons of Ham, as well as the Mallory Brothers’ lullaby, “Don't Cry My Little Picknaninny,” five years earlier. However, Mills proved too young for the Gerry Society and was forced to leave Hall's company to pursue alternative options with her sisters.Footnote 75 Mamie (or Mayme) Remington, a former Topsy delineator, depended upon an unnamed girl and boy in 1897 and later featured four anonymous “ragtime brunettes” or “Buster Brownies.”Footnote 76 In 1901, she hired an eight-year-old girl, who had studied dancers’ variations of the strut, grind, or shuffle at her father's honky-tonk in Birmingham, for so-called ethnic dances. After touring South Africa and Europe with Remington's fifteen-member troupe, Leola “Coot” Grant performed with other partners in vaudeville.Footnote 77

After leaving the Clorindy company, Belle Davis exploited this roiling trend for thirty years beginning in August 1898, when she and Stella Wiley returned to Isham's Octoroons.Footnote 78 For a new ragtime opera and cake walk entitled “The Darktown Aristocracy,” Davis sang her signature songs and introduced her anonymous “pickaninnies” through early October.Footnote 79 While Wiley remained with the Octoroons’ tour, Davis broke away to assert her own “pick” act in Chicago.Footnote 80 She then seized a profitable opportunity to earn $300 a week playing a cook with “two pickaninnies” and a white cast in the three-act musical farce Brown's in Town that opened in Milwaukee in December.Footnote 81 Upon leaving this company, Davis sustained her popular sketch with unidentified “picks” and returned to Chicago in the summer of 1900 with “three oddly rigged negro lads,” along with Will A. McConnell, Williams and Walker's former manager.Footnote 82 During the winter and spring of 1901, she featured a “precocious” girl, a “little colored tot who sings her little solo” and “makes goo-goo eyes” that seemed “particularly appealing to the youngsters in the audience,” according to Boston reviewers.Footnote 83 Having won critical acclaim and financial independence as “the Queen of ragtime singers,” Belle Davis sailed for England in June 1901 with two boys, aged seven and nine, and costarred with them and other boys across Europe until at least 1929.Footnote 84

Back in Chicago, at least one local girl pursued theatrical opportunities at the new Pekin Theatre, along with Lottie Grady. Katie Milton and Hen(ry) Wise helped to open the Pekin with their “two pickaninnies” in 1904; and Chicago-born Nettie Lewis featured the “Buster Brown Boys and Girls” singing “The Tale of the Monkey and the Snake” in Captain Rufus in 1907.Footnote 85 Fourteen-year-old redhead Ada “Bricktop” Smith may have performed in this latter show to satiate her “stage-struckitis.” With the Pekin so near her home, she attended Saturday matinees regularly and haunted the stage door for tips on how to get a job until Robert Motts hired her and some friends. After two weeks of rehearsals and performances, a truant officer grabbed her backstage one night and lectured her mother about keeping her daughter in school. She then bided her time by catching every Williams and Walker show in Chicago; and, upon turning sixteen, she joined Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles in their road show.Footnote 86

Perhaps as a contrast to Gassman's reported treatment and training of her “picks” as a white manager, Mabel Whitman offers another known model of a black manager. Despite having missed her opportunity to work with George Walker in 1897, Whitman coached her nine-year-old adopted sister, Alice, in various dances with the “Dixie Boys” beginning in 1909. As a formidable matriarchal manager, she convinced parents that their children would be well cared for, safely protected, and privately tutored by her husband. Based on her strict moral code for sexual conduct, she insisted that girls travel and lodge separately from boys and forbade her protégés from smoking and drinking. Although her deep booming voice, powerful frown, and “hell-fire and brimstone” disciplinary methods struck fear in her charges, girls looked up to her as a surrogate mother within an extended family of budding vaudevillians.Footnote 87 With the waning of vaudeville, Whitman's schooling of this generation signaled the end of “pick” acts, as minstrelsy sketches gave way to full-blown musical comedies.

Chorus Girls

Like other visionary black producers, Williams and Walker auditioned and hired a multitude of chorus girls as they sought to uplift the burgeoning wealth of unrecognized talent in seven productions that continued to feature cake walks from 1898 to 1909.Footnote 88 Beginning with Senegambian Carnival, their first black-authored, ragtime pastiche, their core company initially involved Abbie Mitchell and Lottie Williams, as well as Ada Overton and Grace Halliday in a sister act, and Mazie Brooks and the Mallory Brothers, among others.Footnote 89 A Lucky Coon spotlighted Ollie Burgoyne, along with Lottie Meredith among thirty-five to forty-five anonymous cake walkers; and, its subsequent fifty-person version, The Policy Players, began to feature eighteen young women in character roles within a loosely knit plot.Footnote 90 The Sons of Ham, another fifty-member production, showcased a gigantic, sixteen-foot-high cake for “a grand spectacular cake walk ballet” with thirty elegantly dressed chorus girls.Footnote 91 The Broadway-breaking success of In Dahomey, with its cake walk performances before King Edward and his nine-year-old grandson in London, and the parodic production of Abyssinia, with an initial company of over one hundred people, broke new ground by introducing the African diaspora to audiences.Footnote 92 Unfortunately, Bandanna Land, which included Muriel Ringgold among its seventy-five cast members, would be George Walker's final “high and mighty” cake walk performance with his renowned wife before illness forced his retirement in March 1909.Footnote 93

As the stunning number of company members multiplied, so too did the widespread obscurity of innumerable chorus girls, known only by their names, brief descriptors with hometowns, character roles, isolated photographs, or short biographies in obituaries as publicized in the black press. For example, Mattie Evans was described as a “dashing little maid” from Louisville with a “clarion voice” that towered above choruses, and Lavinia “Tiny” Jones was lauded for winning a free scholarship to the National Conservatory of Music in New York.Footnote 94 Katie Jones, characterized as a petite and clever toe dancer, played a “kid” in Bandanna Land (and “a boy in overalls” much later), as did Marguerite Ward and Bessie (Brady) Thomas, “two little chorus girls” whose “correct ages” were unknown to the managers.Footnote 95 Given the increasing need for proficient singers, many women from an older cohort came with previous experiences from all-black companies—such as for A Trip to Coontown, a landmark musical comedy produced by Cole and Johnson—stayed for only one or two productions, and then left for other engagements.Footnote 96

Performing and touring together in close quarters not only presented opportunities for single women to cultivate intimate relationships with company members but also posed potentially sexual threats seldom reported in public. For instance, Effie Wilson, a twenty-year-old chorus girl, realized the hazards of budding friendships when, for petty reasons, she was struck by a male company member, who was summarily arrested and fired.Footnote 97 Nevertheless, several women met husbands from among the company's gifted performers, lyricists, composers, playwrights, stage managers, or personal secretaries.Footnote 98 For instance, Laura Bowman (1881–1957) explained how she gained confidence singing in church choirs before auditioning for Walker and rehearsing with Cook at age twenty-two. Despite her marriage at age seventeen, she left her husband and began a common-law and professional partnership with Pete Hampton.Footnote 99 During long stretches of travel, these nomadic twentieth-century women organized and led sewing or literary and musical clubs, served luncheons, loudly cheered the “boys’” baseball games, and engaged in their own sporting events.Footnote 100

At least four sixteen-year-old girls began or extended their performative proficiencies with the company, all of which further prepared them to pursue interrelated and entrepreneurial careers. Minnie Brown (1888–1936) initiated her six-year tenure after raising concert money to study voice and graduating from Spokane high school. Upon retiring from the stage in 1910, this gifted soprano soloist sang at St. Mark's M. E. Church in Manhattan for twenty years, inaugurated a concert bureau with fellow member Daisy (Robinson) Tapley, taught at the Musical Settlement School, and directed several choral groups throughout New York City.Footnote 101

Anita Bush (1883–1974) met Williams and Walker when The Policy Players came to Brooklyn's Bijou Theatre, where her father worked as a tailor. After much cajoling, her father permitted her to join their company as a dancer in at least four productions, whereby she likely applied Walker's business acumen to her own pioneering company.Footnote 102 Odessa Warren (1883–1960) moved to New York City with her parents in the spring of 1898 and may have been in a summer run of the afterpiece “Cook's Tour” at Koster and Bial's before Isham “hurriedly engaged” her for his Octoroons. In addition to her chorus roles beginning in 1899, she created the fashionable “Bon Bon Buddy” hats for Bandanna Land, opened her own millinery shop in New York City in 1908, and later starred with Bert Williams in the 1913 film Lime Kiln Field Day.Footnote 103

After spending two years touring with the Blind Boone Concert Company, Marguerite Ward (b. 1889) joined the company from Kansas City, Missouri, in 1904 as a petite dancer, contralto singer, and ardent admirer of Aida Overton Walker.Footnote 104 Like other members, she subsequently performed in S. H. Dudley's Smart Set company and Cole and Johnson's Shoo-Fly Regiment before achieving her initial dream as a vaudeville star with her husband, Kid H. Thomas.Footnote 105 Frustrated with the lack of specialized stage makeup for the “bouquet race” of African American women, she founded the Marguerita Ward Cosmetics Company in Chicago in 1922 and manufactured thirty-two different shades of “sun-tan” powders from “deep dark to cream white,” an apt extension of her fashionable chorus girl days with Mrs. Walker.Footnote 106

To dignify the company's chorus girls further (during or after their stints), photographs of individual women in black newspapers visualized all skin (and makeup) colors, coiffed hairstyles or wigs, body sizes, and modes of dress both onstage and off.Footnote 107 Images of identified, self-posed women in the 1904 company of In Dahomey also suggest distinct personalities and cosmetic makeup choices in comparison to unidentified women, presumably in stage makeup, posing in two photographs from Abyssinia.Footnote 108 Although the anonymous women in the latter two photos challenge discernible comparisons against individual and company photos, knowing their chorus roles and characters narrows down the possibilities toward attaching names to blurry images. Situated entirely in Africa, Abyssinia featured Lottie Williams, Maggie Davis, Lavinia Rogers, Ada Guiguesse, and Aline Cassell as US characters; while Annie Ross, a former Creole company member, portrayed the Queen of Abyssinia with Aida Overton Walker, Hattie Hopkins, and Katie Jones as named Abyssinian maidens.Footnote 109 Among a bevy of chorus girls, “who needed but little making up to appear as the native born,” the market scene photograph may have depicted petite Bessie (Brady) Thomas, contralto Bessie Payne, Mazie Bush (a former 1895 Creole company member), and Lizzie De Massey from Jamaica as flower girls led by Minnie Brown.Footnote 110

Knowing full well the racial prejudices and theatrical struggles that young women faced, “Dorothy,” a columnist of the Indianapolis Freeman, lauded these and other “Abyssinia Maids” for “raising the standard of that womanhood that has chosen the stage as a means of service to humanity,” while wrestling with “the troublesome race problem.” For those unmarried women “without a legal protector,” she surmised they were learning “a lesson of self-dependence” through “hard toil and sacrifice,” while broadening the minds and hearts of their sisters with other beneficial talents.Footnote 111 Aida Overton Walker also emphasized that “many well-meaning people dislike stage life, especially our women. On this point I would say, a woman does not lose her dignity today—as used to be the case—when she enters upon stage life.” She counseled young women “of good thoughts and habits” not to choose stage work for its dazzling brilliance but “for the love of the profession” whereby hard earnest work would repay them handsomely with a noble life.Footnote 112

To these ends, Mrs. Walker continued to showcase new “dancing girls” by producing two highly successful entertainments.Footnote 113 To benefit the White Rose Industrial Association for Colored Working Girls in June 1908, she reintroduced Bessie and James Vaughn's five-year-old daughter, whom they christened Ada. While dressed as Mrs. Walker in miniature, little Ada Vaughn enamored audiences by singing George Walker's “Bon Bon Buddy” with her godmother wearing male attire.Footnote 114 Tucked among seventeen chorus girls who represented Southern flowers lay another budding star raised in the cotton fields of Tennessee. Lottie Gee (ca. 1886) had begun her career at age nine with a ragtag jubilee company and learned dancing from other troupers.Footnote 115 After nineteen-year-old Effie King joined her in Bandanna Land, Gee performed a sister act with King as the Ginger Girls before her breakthrough role in Shuffle Along in 1921.Footnote 116

As George Walker's health worsened, Bert Williams opened Mr. Lode of Koal in September 1909 with his new costar, Lottie Grady, in lieu of Aida Overton Walker, who instead chose to star in Cole and Johnson's The Red Moon and other companies before her untimely death in 1914.Footnote 117 Nevertheless, sixteen loyal women whom she had assiduously tutored earned noteworthy praises in this short-lived production.Footnote 118 Despite the tragic losses of George Walker and Bob Cole in 1911, the young women in their respective companies had not only benefited their own careers but had also paved the way for subsequent generations of chorus girls.

When The Darktown Follies closed at Harlem's Lafayette's Theatre in 1914, its grand cake walk finale by the entire cast marked the end of grandiose cake walking performances in large musical companies. However, its serpentine circle dance presaged a new sensational period of African American musical theatre in 1921 when Lottie Gee and former “picks” Florence Mills, Edith Spencer, and Eva Taylor achieved stardom in Shuffle Along.Footnote 119 Even though Williams and Walker had broken Broadway's racial boundaries twenty years earlier, and The Darktown Follies had inspired white audiences to trek to Harlem, all-black companies had faced ongoing struggles for another decade until Shuffle Along pioneered girls’ culmination of modern jazz dancing and the long sought-after approval of a romantic song, “Love Will Find a Way.”Footnote 120 In other words, once girls born in the 1870s and early 1880s had successfully pushed the limits of female minstrelsy in the 1890s, girls born from the mid-1880s through the mid-1890s found their ways of innovating musical comedies in the 1920s.

Conclusion

This reconstructed genealogy of black performing girls reveals a more complex portrait of the multifarious strategies they employed to achieve their dreams in lieu of otherwise domesticated lives. Initially, most youngsters likely discovered the roots of their embodied passions by freely expressing their bodies and voices through dramatic play and by meticulously scrutinizing other performers’ tactics as they joined local entertainments in their immediate environments. Upon earning their own pennies from local gigs or cake walking contests, they likely apprehended how performance could not only be a joyful route of artistic self-expression and innovative experimentation but also an alternative financial means of economic freedom for themselves and their families’ survival.

However, to cultivate their nascent song-and-dance talents, girls took different strategic routes, with or without their families’ blessings, both within and away from hometowns that spanned the entire United States. For those who left home at an early age, some mothers decided to expand their daughters’ prospects for them as “picks” with female guardians. Others supported their daughters’ budding desires to train as dancers and/or singers by allowing them to leave home to study with specialized teachers while living with same or different family members in other cities. Some unruly girls simply decided to run away with ragtag minstrel troupes to practice their own experiential schooling through performance, while others brought their mothers along with them as company chaperones or traveled with their theatrical parents. For those who stayed near their homes, many bided their time by taking dance or voice lessons, singing in church choirs, playing musical instruments, watching rehearsals, attending shows, and finishing their formal schooling before making their professional stage debuts as adolescents. Once on the road to their performative lives, their growing networks with other performers escalated their options in sister acts or husband-and-wife teams, other choruses, or leading roles in all-black musical comedies. Whichever routes they followed, whether as cake walkers, “picks,” or chorus girls, each girl uplifted her own racialized life on her terms by taking full advantage of respective local, national, and international opportunities.

While the cake walk photo girl endures as a postcard commodity for others to enjoy, share, and collect in scrapbooks, black girls’ lifelong achievements as groundbreaking dancers, singers, and actresses should no longer be regarded as mere footnotes in the history of musical theatre. Although very little documentation exists on the childhoods of these girls, historians might consider writing more complete, recuperative biographies of these theatrical women, drawn from sources provided herein, that could also broaden historicized perspectives on black girlhood culture. For now, girls’ historically contingent strategies of artistic freedom and socioeconomic survival reflect those of grown performing girls today, as black girlhood scholars theorize and practice hip-hop feminism with today's dancing girls.Footnote 121 By initiating performative acts from girls’ embodied creativity, perhaps the ghosted legacies of the cake walk photo girl and her lesser-known companions may persist among present and future generations of performing girls.