In April 1885, a New York Herald journalist rushed to Madison Square Garden for a special reception highlighting Jo-Jo, the Dog-Faced Boy. A feature of P. T. Barnum's traveling show, Jo-Jo was confounding scientists who had requested a stand-alone inspection of the mysterious attraction.Footnote 1 Accordingly, the reporter provided an anthropological description of the boy: “He stands about five feet high. . . . His whole body is covered by a very thick growth of long, tow colored hair . . . and the peculiar formation of his head [is] very suggestive of the Russian dachshund.”Footnote 2 At first, Jo-Jo appeared docile, but as the scientists prodded him more and more, he started “snarling, showing his three canine teeth” and asked his guardian if he could bite the inspectors.Footnote 3 Jo-Jo was decidedly not a dog-boy, or not exactly. He was, in fact, a Russian teenager suffering from hypertrichosis, a condition causing excessive hair growth all over the body, including nearly every surface area of the face.Footnote 4 Barnum had signed him to perform a year earlier, and the boy made quite an auspicious debut. However, Jo-Jo was simply the latest in a long line of supposed hybrid species and exotic curiosities that Barnum had been displaying since midcentury. The famed showman built his name in part by presenting human creation itself as a continual spectrum. Barnum's attractions ranged from live tigers and giraffes to enigmatic simian performers to wax statues of America's degraded lower classes. As much of a draw as he became, even Jo-Jo had to share a bill with Tattooed Hindoo Dwarfs, Hungarian Gypsies, Buddhist Priests, as well as a menagerie of animals including baby elephants, kangaroos, lions, and twenty-foot-long “great sinewy serpents.”Footnote 5 But Jo-Jo's specific appeal was tied to his inexplicability. Even given the closer inspection of the dog-faced boy, “none of the physicians present would hazard an opinion as to his ancestry.”Footnote 6

Of course, Barnum specialized in this mode of hoax theatricality, and critics since have attempted to decode it. Historian James Cook defines Barnum's stylings as “artful deception,” which “involved a calculated intermixing of the genuine and the fake, enchantment and disenchantment, energetic public exposé and momentary suspension of disbelief.”Footnote 7 As Cook explains, audiences knew they were being conned somehow, but they still attended. Much of this willingness was due to the makeup of his audiences: the white middle classes who were attempting to separate reality from appearance in an increasingly unreadable urban world. Barnum's artful deception, then, became a “slippery mode of new middle-class play,” appealing because it allowed “public debate and judgment in the exhibition room.”Footnote 8 Attempting to declare themselves as an astute social collective, the middle classes could rehearse their own skills of observation and visual decryption in Barnum's halls. Scholarship on Barnum and his audiences, however, often stops geographically at the venue. So what happened when his spectators left the Museum, as they traveled through city streets and back to their private residences? Did Barnum's enigmatic attractions lend audiences their desired clarity? Or was the joke ultimately on these viewers who often failed to explain exactly what they had witnessed? As critic Bonnie Carr O'Neill recently has stated, “Barnum's career and methods attest to the relocation of pleasure from the private sphere to the public sphere.”Footnote 9 While this assessment proves illuminating, patrons inevitably returned to their private homes—and took their spectatorial memories with them. Barnum's Museum, it turns out, was merely the first stage upon which some audiences attempted to decipher the strange sights they encountered.

Like Barnum's Museum, mid-nineteenth-century home parlors were teeming with mermaids and centaurs, dwarfs, giants, and fake alligators—albeit ones that could be more easily explained and controlled. Evidence indicates that middle-class Americans were frequently costuming themselves as foreign humans, mutants, and animals in amateur shows for family and friends. Ranging from silly to surprisingly graphic events, the parlor museum shows were not without a serious purpose. They dovetailed with some of the most expansive years of American social class formation and division. As several historians have detailed, the era's citizens often cited their popular culture tastes—rightly or wrongly—as a means of self-identifying with particular societal tiers.Footnote 10 Thus the private parlor museum became an extension of the ways that nineteenth-century Americans conceived of their own statuses.

This essay argues that by importing Barnum's “freak” exhibits and moral-reform shows within their homes, middle-class amateur performers could alter the attractions’ meaning to suit their own social interests. Sometimes, participants may have adapted comical versions of Barnum's exhibits to present themselves as a specifically white, enlightened class unsusceptible to the Museum's trickery. At other moments, they seemingly amplified the Museum's human grotesquerie to prove their clear distinctions from racial Others, the lower classes, and the disabled. Regardless, as dictated by a series of guidebook authors, these home performances transferred power back to the middle-class spectators themselves. Although Barnum initially utilized deception and moralization to assemble a distinct middle-class patronage, the private parlor museum flipped the dynamic. By privately restaging the showman's signature stage exhibitions—a theatrical one-upmanship of sorts—Barnum's viewers ultimately could mold the public Museum exhibits to advance their own agendas of class security and consolidation.

The Middle Classes at the Museums, in the Parlors

The emergent American middle classes were at times difficult to characterize, but historians have determined several markers of the social rank. By midcentury, terms such as “middle classes” or “middling class” began to seep into the public discourse, with varying degrees of meaning.Footnote 11 Whether by habit or from bias, the press was almost always referring to white populations when using the terms. Journalists and cultural arbiters also agreed that crucial to the middle classes’ definition was their distinction from those a social tier below. As historian Stuart Blumin writes, “the middle class had risen to a position distinctly superior to that of the working class and could no longer be spoken of in the same breath with the poor and ‘inferior’ inhabitants of the city.”Footnote 12 The Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations and Walt Whitman also identified middle-class Americans as salaried (and, more specifically, nonmanual) workers.Footnote 13 So from the earliest days of the vocabulary being in use, the middle classes were in part defined by who they were not. Those presuming to belong to the social station apparently adopted the same guidelines. Following the Panic of 1837, middle-class urban residents were moving farther away from both their own places of work and from the downtown dwellings of the working classes.Footnote 14 Establishing a private residence—either on the periphery of cities or in the nearby suburbs—provided an important sense of achievement for the upwardly mobile.Footnote 15 Within their new homes, the parlor became an especially significant space signifying middle-class status. It emerged as an epicenter for reading club meetings, courting events, and social visiting among those with similar occupations and values.Footnote 16 Additionally, the parlor transformed into a stage where the new classes could perform their roles as privileged white consumers. In both an imitation of European culture and a celebration of American empire, middle-class housewives often filled their parlors with Eastern decorations, from Turkish curtains to “Oriental cosey corners.”Footnote 17 Against this imperialist backdrop, staging private entertainment further solidified participants’ social and racial standing.

For this reason and others, the era's home theatrical trend remains a curious form of class-based leisure. While amateur theatre had taken several manifestations for centuries before, it found new prominence in nineteenth-century America with the widespread publication of various how-to guides.Footnote 18 Instructions for at-home charade games and “moral dialogues” first appeared in middle-class periodicals such as Godey's Lady's Book and Forrester's Playmate in the 1850s. Over the next two decades, dozens of individual guidebooks aimed at middle-class readers hit the marketplace, with titles like George Arnold and Frank Cahill's The Sociable; or, One Thousand and One Home Amusements (1858), James H. Head's Home Pastimes; or, Tableaux Vivants (1860), and Frank Bellew's The Art of Amusing (1866).Footnote 19 Within these books outlining the broad practices of parlor theatricals, various genres emerged, including charades, shadow pantomimes, condensed commercial dramas, tableaux vivants (or “living pictures”), and home museum shows. While parlor theatre remained a national phenomenon—guides were advertised in local newspapers from New York to Macon, Georgia, to Columbus, Ohio, to San Francisco—the most cited records come from cities in the Northeast. Although firsthand accounts of home theatricals exist, they are not nearly as common as the parlor guidebooks, which have become the dominant evidence in parlor theatrical studies.Footnote 20 The sheer ubiquity of the guidebooks, as well as the repetition of the same parlor theatre genres across these manuals, indicate that an eager and active market existed.

The texts name a wide range of participants, including both white and Black populations, city dwellers and country players. But, as critic Melanie Dawson outlines in her influential study Laboring to Play, most performers and audiences “were likely white, middling Americans.”Footnote 21 Far from amateur theatre being simply child's play, adults acted as much if not more than children. The theatricals foregrounded lighthearted amusement, and the ostensible purpose was to inject the home with laughter and levity. But for the grown-up participants in particular, performances could simultaneously unlock a certain social cachet.Footnote 22 Guide authors often presented parlor theatre not only as an alternative to a dangerous public world but also as a means to self-reflect on class values. As Dawson notes, “home entertainment provided not only diversion, a relief from ennui, and an occasion for behavioral expansiveness, but it also served as a forum for examining developing middling lifestyles.”Footnote 23 Staging a series of theatricals or an evening of tableaux thus held several purposes. Amid laughing at costumed friends and family members parading around the parlor, audiences were also staking out what they believed to be class-exclusive leisure activities. Through home theatre, the guides finally imply, the middle classes could begin to contemplate and cement their distinct bonds as a burgeoning social collective.

The guide authors helped in this regard, and a central goal both of middle-class life and of home theatricals was education. According to the guides, engaging skills of memory, stagecraft, and embodiment all helped to nurture one's intellect. Theatricals complemented rather than replaced school instruction. For instance, the introduction for the anonymously penned Parlor and Playground Amusements (1875) reads, “Amusement, when properly regulated, is a grand help-mate to study.”Footnote 24 Guide authors rarely explained exactly how the theatricals assisted intellect beyond such declarations. But vague promises of “innocent, harmless” fun appeared to satisfy readers who were worried about any attendant impropriety.Footnote 25 Authors’ references to schools as alternative performance venues also implied the potential for learning. Education became so paramount to private theatre rhetoric that the authors sometimes presented fun itself as a kind of ruse. In the Preface for their Parlor Theatricals; or, Winter Evenings’ Entertainment (1859), writers George Arnold and Frank Cahill state that theatricals serve “a higher purpose than mere amusement. They stimulate the faculties, arouse the wit, and, under the guise of amusement, develop and exercise the mental functions.”Footnote 26 At the very least, these instructions allowed participants to search for a deeper meaning. Defying anyone who might dismiss parlor entertainment as frivolous game playing, guide authors recast private theatricals as a means of intellectual advancement. This feature became especially important as the home stage sought to offer a partial substitute for commercial theatre enterprises.

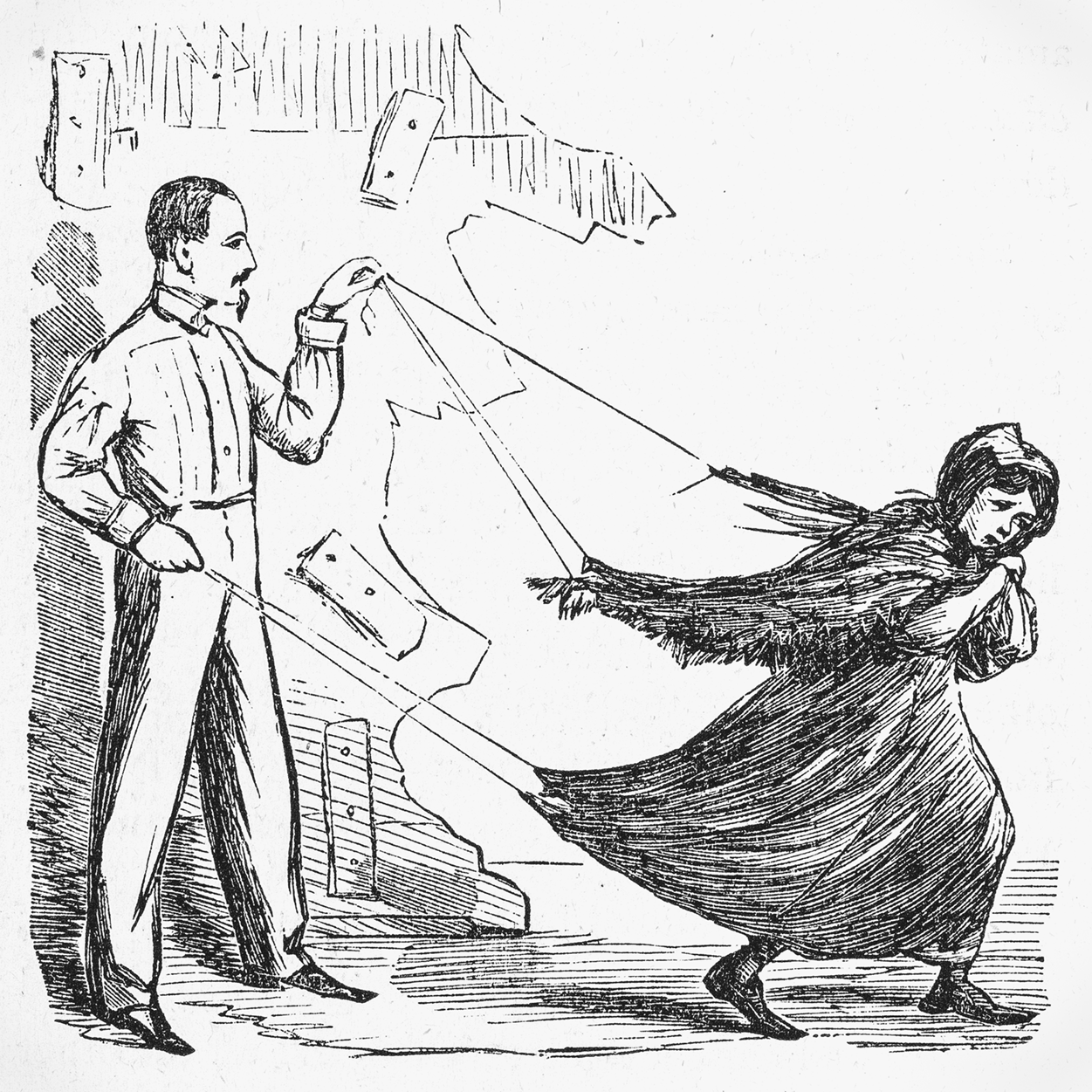

By its very design, middle-class parlor theatre could only work if its participants respected and at least partially imitated the public playhouse. In the introduction to his Amateur's Guide to Home Theatricals (1866), Tony Denier states that it must “be distinctly understood that the aim is . . . to aid those ambitious aspirants who are satisfied with nothing less than a ‘real theatre,’ with all its mysteries of flies, flats, borders, sets and wings.”Footnote 27 Accordingly, guide authors recommend assembling a homemade stage by nailing planks of wood together. Stage platforms could be constructed as large as twelve feet long by eight feet wide; prosceniums stretched up to eight feet high and held colored drop curtains simulating those in public theatres. Writing to Godey's Lady's Book about her family's theatricals in 1860, teenager Ella Moore reports erecting a proscenium frame in the doorway separating two parlors and then decorating the stage with colored muslin and tarlatan.Footnote 28 Guide authors encouraged participants to draw their own scenery, apply real stage makeup, and even create complex special effects.Footnote 29 Frequently, these effects were aural. To simulate thunder, for instance, authors recommend standing out of view and shaking an iron sheet;Footnote 30 to mimic the sound of a broken window, authors tell participants to gather broken pieces of china in a basket and then dash it against the floor.Footnote 31 Other times, home theatricals might require complex behind-the-scenes collaboration to produce a visual illusion. In his 1866 guide The Art of Amusing, Frank Bellew outlines one scene in which the audience sees a girl seeking shelter; she is “struggling against the blast, her shawl and dress . . . violently agitated by the wind.”Footnote 32 The success of the effect depends upon carefully timed choreography and coordination: “To produce this effect attach two or three strong threads to the garments named, and at the proper time jerk and pull them with a tremulous motion, to impart the natural action” (Fig. 1).Footnote 33 The goal is to conceal the machinations that produce the effects and absorb spectators into the scene, just as would a professional drama featuring such stage illusions. Parlor shows were obviously lower budget and more intimate in nature than their commercial analogues. Yet guide authors still instructed participants to preserve the diegetic potential of a “real” theatrical production.

Figure 1. Frank Bellew, The Art of Amusing (New York: Carleton, 1866), 236. For special effects, guide authors encouraged parlor theatre participants to rely on crude stage trickery, such as this endeavor to simulate a high wind by pulling strings attached to a performer.

Despite these aspirations, the middle classes’ relationship with the public theatre remained complicated. Throughout the nineteenth century, cultural arbiters often sought to prevent the middle classes from attending commercial stage shows. In the 1830s, American educator and reformer William Alcott warned about theatre's appeals to humans’ base passions, and he “began to delineate a respectable middle class by designating play-going as immoral.”Footnote 34 Alcott and others steered genteel society members away from the mainstream theatres, which were chiefly portrayed as harboring lower-class spectators and prostitutes.Footnote 35 Even decades later in 1857, the bourgeois Harper's Weekly magazine decried that new theatres only bred intemperance and sexual immorality.Footnote 36 Theatrical professions often proved troubling, and even as the home theatre trend was launching in the early 1860s, guide authors acknowledged the dangerous association with commercial theatre and particularly its working actors.Footnote 37 However, none of these fears prevented a middle-class theatre from developing and even thriving by midcentury. Beginning as early as the 1840s, curiosity museum proprietors Moses Kimball (with his Boston Museum) and P. T. Barnum (with his American Museum in New York) helped to establish theatrical entertainments tailored for the new middle classes.Footnote 38 Both managers shifted attention away from the lower-class audiences and unseemly associations of the American stage. Instead, the two men opened fully operational theatres that they deemed “moral lecture rooms” to avoid any alignment with the public theatre.Footnote 39 Alcohol, prostitution, and rowdy behavior were banned in these new lecture rooms.Footnote 40 The respective managers also programmed antidrinking and antigambling plays and offered matinees to women, children, and other “Christian respectables.”Footnote 41 In the following decades, many northeastern theatres would use some of the same formulas to draw this growing middle-class patronship prompted by Kimball and Barnum.Footnote 42

The museum hall attractions, particularly at Barnum's Museum, had already gathered a middle-class fandom before the installation of the theatrical spaces. Barnum temporarily ran museums in Baltimore and Philadelphia in the antebellum period, but he established his principal Museum in downtown New York (on Broadway and Ann Street) in 1841.Footnote 43 When it opened, he featured dozens of displays within four one-hundred-foot halls. He gradually expanded into adjacent buildings, enlarging and renovating his lecture room in 1850 and doubling his overall exhibition space by 1854.Footnote 44 Combining his extensive collection of curiosities with those he seized from rivals, Barnum filled his halls with stuffed birds, automata, rare coins, fossils, autographs, weapons, cosmoramas (i.e., peephole panoramas), daguerreotypes, relics of natural history, waxworks, and live animals, among other features.Footnote 45 He also recruited various “freaks” (i.e., human oddities), including dwarves, giants from abroad, the “What Is It?” missing link, and albino families. Patrician New Yorkers looked down on Barnum's venue and distinguished their own highbrow museums like the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the late 1860s.Footnote 46 But Barnum maintained a hold on the middling social groups, largely because he prioritized guiding their evolving spectatorial tastes.

Once Barnum successfully attracted a middle-class patronage in the 1840s, he subsequently attempted to mold their values. Some upwardly mobile working-class locals still attended his Museum, but Barnum often priced out lower classes and Catholic immigrants, especially for special engagements like Swedish singer Jenny Lind in 1850.Footnote 47 Instead, he targeted middle-class patrons, even though he was dissatisfied with their preexisting theatrical proclivities.Footnote 48 In his first autobiography, entitled The Life of P. T. Barnum (1855), he writes “our countrymen, of the middling classes, inherit in too great a degree a capacity only for the most valueless and irrational enjoyments.”Footnote 49 Barnum not only identified his desired audience members but also sought to correct their lowbrow viewing habits. In programming too, his lecture room highlighted the values of self-control and class preservation. Plays like Rosina Meadows, the Village Maid; or, Temptations Unveiled (1843) and The Drunkard; or, The Fallen Saved (1844) illustrated the dangers of falling from middle-class respectability.Footnote 50 These moralizing dramas filled a significant gap for an emergent theatrical audience. In his second autobiography, Struggles and Triumphs, Barnum argues that he offered only “wholesome attractions” that enlightened viewers, and he boasts of the “greater decorum which characterized my audiences.”Footnote 51 Hence, Barnum provided his patrons a medicinal brand of theatrical spectatorship and sought to cultivate a genteel behavior in them. By following his orders of education and morality, he promised, audiences could then achieve their desired goals of respectability. As critic Bluford Adams so plainly puts it, Barnum “taught the middle class what it meant to be a class.”Footnote 52

Home Museums and Performative Consumers

Yet because of the artful deception defining the theatregoing experience at Barnum's, the middle-class audiences always remained at a slight disadvantage. They consistently were at the mercy of Barnum's pricing, staging, and trickery. Parlor guidebooks, then, offered a self-rewarding alternative by teaching consumers how to produce socially exclusive exotic museums in their own parlors. In appropriating and restaging attractions from Barnum's venue, the middle classes could continue their negotiations with his bewildering spectacles on their own terms.Footnote 53 Specifically, their adaptations of Barnum's exhibits tackled lingering discomforts with the famed showman's venue. Hosting various freaks, strange animals, foreign creatures, and racial Others, Barnum's Museum was, according to Eric Fretz, “a site of cultural exchange and conflict” where “the public display of theatrical selfhood both confirmed and implicitly challenged middle-class values.”Footnote 54 While the educational elements of museum culture aligned with middle-class principles, many of the grotesqueries did not. Nor did Barnum's insistence on holding theatrical truth back from his audience. Hence, by staging makeshift versions of these Museum features at home, the middle classes could exert more control over the attractions themselves and more clearly define their own class-specific values.

Barnum earned his reputation, and many of his profits, by providing his spectators the illusion of enacting their presumed superior knowledge. O'Neill writes that while viewers knew Barnum might be deceiving them, museumgoing evolved into “contests between him and his patrons, who attempted not just to figure out the puzzle but, in doing so, to beat Barnum at his own game.”Footnote 55 Yet more than antagonistic contests between Barnum and his audiences, the exhibits operated as thrilling tests of the spectators’ own intellect. Barnum's rotating door of resurrected half-breeds and supposed missing species pulled in viewers eager to affirm that they could spot a fake when they saw one. Perhaps most infamously, in 1842, he unveiled the “Fejee Mermaid,” an exhibit he shared with Kimball.Footnote 56 Barnum took the lead on marketing, claiming the mermaid was the embalmed and perfectly preserved skeleton of a distant Pacific creature. Eight-foot-long transparencies of a beautiful mermaid hung outside of the New York Museum, and so viewers were inevitably disappointed to find a three-foot desiccated mummy as the corresponding feature inside. The “mermaid” was, in fact, the head and midsection of a monkey stitched to the body of a large fish, although it was not necessarily apparent to the naked eye. Viewers and journalists warned others against being fooled, but Barnum nearly tripled the Museum's earnings from the previous month, and the mermaid was soon thereafter dispatched on tour.Footnote 57 This deception, and the ensuing commercial success, reveals a critical principle—and genuine appeal—of the Museum. Audiences likely knew the mermaid was a scam. Barnum probably knew that they knew it was a scam. But he still convinced spectators that, in order to prove their intelligence, they still had to buy tickets and decipher the mystery.

Nearly as popular as the Fejee Mermaid, but more racially charged, was Barnum's “What Is It?” attraction, which similarly tempted audiences keen to solve the enigma of an anthropological Other. An “Apparent Man Monkey” according to advertisements in the 1860s, the “What Is It?” may really—or may really not—have been a Black man named William Henry Johnson who suffered from microcephaly (an unusually small and deformed skull).Footnote 58 Barnum's race-focused features like the “What Is It?,” the Leopard Boy, and numerous displays of Native Americans enabled his white middle-class spectators to fancy themselves as civilized superiors.Footnote 59 The Currier & Ives advertising poster spells out this spectatorship quite literally (Fig. 2). Five white viewers—standing upright, dressed in top hats, bonnets, and crinolined dresses—stare quizzically at a crumpled dark-skinned figure leaning on a bamboo stick for support. Flashing a childlike grin and failing to meet the patrons’ gaze with his own, the “What Is It?” is so mesmerizing for his stark contrast to those looking upon him. Rendered distinctly Other by his skin color, shabby wares, and disabled physicality, he reinforced white audiences’ self-conceived supremacy. In visual configurations like this one, whiteness becomes coded as the apotheosis of the human, cemented by the onlookers’ viewership of a Black body positioned as lower down the evolutionary scale. Moreover, as Cook points out, by billing the feature as a “nondescript” instead of a Black man, Barnum provided a venue in which spectators could “talk openly about black people, often in brutally dehumanizing ways . . . without even acknowledging who, exactly, they were talking about.”Footnote 60 As the white middle classes were gathering publicly and determining their mutual values, the “What Is It?” allowed them to bond, often silently, through a shared form of racist viewership. Through this fundamental anti-Blackness, Barnum implies, patrons might more easily appreciate their similarities to one another.

Figure 2. “What Is It? or ‘Man Monkey,’” ca. 1861. Currier & Ives Poster. The New York Historical Society.

Beyond the inherent racism, these exhibits also required audiences to conduct logistical work to determine what exactly they were viewing. Even though Barnum enabled his spectators to bond over their physical differences from the “What Is It?,” the actual truth of the feature's existence was far from clear. Barnum instructed exhibitors to leave the description purposefully vague. Advertisements asked, “Is it a Man? Is it a Monkey? Or is it Both Combined?”Footnote 61 By employing such language, O'Neill submits, “the exhibit shifts intellectual authority away from experts and onto audience members.”Footnote 62 This move may have privileged the spectators’ whiteness and even given these viewers an ostensible authority, but not without causing significant confusion too. Barnum debuted the “What Is It?” at his American Museum in February 1860, only three months after the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Marketing the feature as a possible “missing link,” Barnum dared his viewers to connect the anthropological dots. So as swiftly as patrons may have been able to access their prejudice against the “What Is It?,” there remained a fair amount of unfinished intellectual work. Specifically, the exhibit challenged white, middle-class viewers to assess what combination of biology and stage trickery was before them and also to assign the specimen a decisive spot on the evolutionary spectrum. It was no easy task. As Cook states, Barnum presented “an arena in which the process of human definition itself was becoming more ambiguous and fluid, more prone to manipulation and experimentation.”Footnote 63 Fact and fiction began to blur. At the same time that middle-class spectators were enjoying theatrical venues crafted for them, they also were more eager than ever to prove that they could not be duped. Barnum profited by capitalizing on these insecurities and providing audiences a forum to rehearse their intelligence. Yet even when spectators could determine Barnum was attempting to fool them, they did not know how exactly Barnum pulled off the trick. As this piece of the puzzle always remained just out of grasp, Barnum still held an upper hand within the Museum's confines.

In turn, guidebook authors suggested that staging makeshift museums at home allowed middle-class readers to express their cynicism toward Barnum's attractions—and show off the extent of their knowledge—in a friendlier environment. While parlor museum shows never constituted a standalone book genre, most home theatre manuals devoted substantial sections to the subject and its potential displays. For instance, in his home amusement guidebook What Shall We Do To-Night?, pseudonymous author Leger D. Mayne describes one parlor entertainment entitled “The Museum.” The game asks a participant to jump up spontaneously from the audience, pose as a museum proprietor, and jokingly sell some of his collected curiosities. Mayne's exhibitor proceeds to throw a handkerchief over a gentleman's face and explains, “Here . . . you may see a stuffed alligator from the banks of the Nile. . . . During our voyage home, while I endeavored to keep him alive, he devoured seventeen negro babies every day, and washed them down with nine gallons of the best Eau de Cologne.”Footnote 64 Whereas many traditional parlor shows draw clear lines between audience and performer, Mayne's home museum erases them. Not only does the primary performer himself emerge from the audience but—in a satirical impersonation of Barnum—he turns other spectators into his absurd specimens. Later, he casts a “pretty blushing girl” as a casket of jewels, and the guidebook recommends presenting other audience members as Egyptian mummies or Cleopatra's needle.Footnote 65 Although Dawson affirms that this type of museum entertainment “is at once a vehicle of social life and simultaneously a critique of ambitious enactments of middling sociability,” it also empowers the participants as previous spectators of Barnum's exhibits.Footnote 66 The show replicates the spontaneity of walking through American Museum halls and encountering unexpected sights, while it also self-consciously mocks Barnum's attempts to fool patrons. As Cook writes, “Barnum feigned ignorance on his own behalf” about the factuality of his mythical attractions; instead, the showman “deferred to viewers for answers.”Footnote 67 Through staging an overtly comical home museum, Barnum's middle-class patrons could declare to each another that they were not fooled by Barnum's ruses—and, moreover, that determining the precise means of his trickery never mattered. The guidebooks converted Barnum's passive spectators into emboldened producers, allowing them to express their self-perceived intelligence more freely than on the showman's home turf.

This crucial dynamic—in which the middle classes could now overwrite Barnum's cons at home—expanded as guide authors directed home performers to dress as various museum freaks and impossibilities. Although guidebooks encouraged readers to imitate curiosity museums’ very real exoticisms (including an elaborate and cheaply comical staging of a homemade giraffe; Fig. 3),Footnote 68 the parlor stage more often favored mythological and fictional creatures. For example, Mayne outlines how readers can create a makeshift “Centaur”: one performer crouches behind another whose face and torso remain visible, while an assistant drapes a “rich fabric” over the back of the trailing performer, and attaches a tail made from strips of paper and cloth (Fig. 4).Footnote 69 A bow and arrow, helmet, and beard on the visible actor completes the picture. The performance itself consists of rapid, flailing motions: “The prancing, curveting, cantering, and the various attitudes assumed by the principal figure, shooting the arrow, throwing the spear, flinging the arms about, swaying the body, . . . can, in good and intelligent hands, be made very effective and diverting.” The show alternates between horror—as the performers yell out “ejaculations of fierceness, defiance, terror”—and comedy—as the author suggests staging “[v]ery amusing scenes” of two centaurs jousting. Performers should contort their bodies and run wildly around the living room, with Mayne even recommending that the centaur rest occasionally so that the rear performer can catch his or her breath.Footnote 70 Much of the conscious spectatorial pleasure surely derives from witnessing a familiar neighbor or family member transform into a fantastical creature. The crude, cheap production values only exaggerate the exhibition's utter fakeness and enhance its comic effect. Secondarily, however, the middle classes could continue to negotiate their understanding of popular museum culture. As with the stuffed alligator auction, spectators can bond in their refusal to “buy” the feature on display. Instead of wasting mental energy in trying to determine how Barnum was deceiving them, his spectators could relish in the now-obvious means of humbuggery. If all of Barnum's freaks are fake, then a homemade one evidently offered just as much appeal—all the while eliminating the fear of being hoodwinked at the public Museum.

Figure 3. “The Giraffe,” in Leger D. Mayne [William Brisbane Dick], What Shall We Do To-Night? or, Social Amusements for Evening Parties (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1873), 68–9. Home museum shows allowed performers to imitate creatures both real and mythical with the help of creative costuming, rudimentary construction skills, and willing performers.

Figure 4. “The Centaur,” in Leger D. Mayne, What Shall We Do To-Night? or, Social Amusements for Evening Parties (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1873), 42–3.

Other times, as with home dwarf stagings, the middle classes could attempt to produce an attraction just as mockingly amusing as Barnum did. To create a “German Dwarf,” the anonymous author of another guidebook, How to Amuse an Evening Party (1869), instructs two performers to stand inside a deep window with curtains. The speaking player—whose face is visible—outfits his arms as legs, and places them into a pair of boots on a table in front of him. The second player—whose face is concealed—puts his arms through the oversize sleeves of a jacket also worn by the speaking player. The final effect combines a giant head with small limbs. Once the audience arrives, the dwarf “begins an harangue, interlarding it copiously with foreign words and expressions. While he speaks, the actor performs the gestures. . . . The actor always tries to make his gestures wholly inappropriate to the language of the speaker, and indulges in all kinds of practical jokes.”Footnote 71 Mayne's similar “Table Orator” “selects some deeply tragic or sensational speech, while the acting orator makes the gestures” (Fig. 5).Footnote 72 As both guide authors convey, the amusement derives from the uneasy juxtaposition between the dwarf's physicality and his language. Here is a character so visually outlandish that the more he attempts to infuse his words with seriousness, the more gut-bustingly ludicrous he seems.

Figure 5. “The Table Orator,” Leger D. Mayne, What Shall We Do To-Night? or, Social Amusements for Evening Parties (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1873), 101–2. Guide authors frequently encouraged home museum performers to imitate various freak exhibitions, usually by combining and contorting bodies and playing with physical scale.

These domestic dwarfs, of course, approximate one of Barnum's most famous attractions, General Tom Thumb (birth name Charles Sherwood Stratton).Footnote 73 An ateliotic dwarf whom Barnum obtained as a child in the early 1840s, Thumb possessed limited talent by most accounts.Footnote 74 But Barnum turned Thumb into a theatrical draw by training him in vaudeville routines and directing him to pose as historical heroes, usually for comic effect. Thumb would dance jigs or pose as mythological heroes to the laughter of audiences.Footnote 75 He swiftly became a phenomenon, selling out Museum shows and traveling engagements and finding immense popularity overseas, where he performed for Great Britain's royal family in 1844.Footnote 76 Visual material related to Thumb, such as a ca. 1850 daguerreotype, emphasized his obviously diminutive scale as he stands on a table next to Barnum himself (Fig. 6). Thumb's hand is delicately placed on the shoulder of Barnum, who sits proudly grinning and cocking his elbow to the side. The picture reveals several dynamics: Barnum's figurative ownership of Thumb, Thumb's seeming dependence on the man who made him, a twisted father–son codependence. Despite such a specific history between the two men, some of these strange theatricalities could still translate to the parlor stage.

Figure 6. P. T. Barnum and Tom Thumb (Charles Sherwood Stratton), ca. 1850. Half-plate daguerreotype. The Smithsonian Institution.

Guidebooks suggested that, with homemade materials and clever disguising, amateurs might actually create a substitute Tom Thumb at home. Boasting that the German Dwarf “is a most comical entertainment,” How to Amuse's author asserts that this fake dwarf is just as humorous as the real thing.Footnote 77 Here, the middle classes might amplify the comic qualities that they found so amusing about the Museum attraction in the first place. As evident in Thumb's formal clothes and askew military hat, Barnum relied on the cheap comedy of a childlike dwarf pretending to be a distinguished grown man. Barnum even cast Thumb in full-length dramas to exploit the cognitive dissonance for laughs.Footnote 78 Accordingly, in the home version, Mayne's Table Orator attempts to recite a Peruvian commander's battlefield speech from Richard Brinsley Sheridan's tragedy Pizarro (1799).Footnote 79 But as delivered by an immobile dwarf who picks his teeth and swats imaginary mosquitoes, the dramatically heroic monologue is rendered laughably pathetic. Home performers preserve the absurdity of Thumb's comical routines and also, via clever stagecraft, ridicule his physical condition. Importantly, they also adopt the spirit of Barnum's proprietorship over the act: now, it is their version of the famed dwarf fully under their jurisdiction. In adhering to guidebook advice, the middle classes show that they do not have to be subject to Barnum's programming or even his prompts to laugh. In the convenience of their parlors, they can reproduce all of Thumb's amusing effects but simultaneously control their own cues and responses.

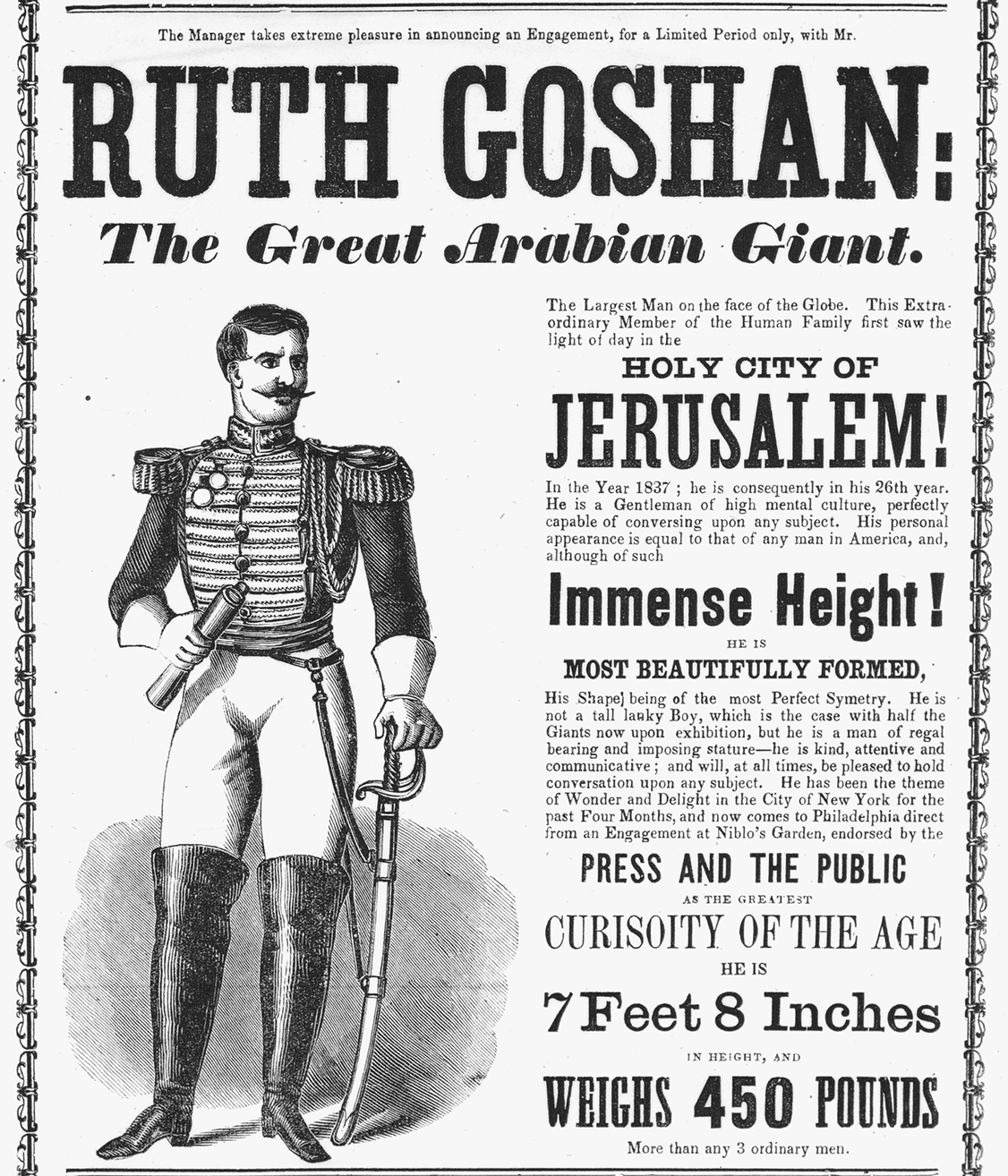

In a “jolly companion” piece entitled “The Kentucky Giant,” How to Amuse's author presents a home version of Barnum's famous oversized attractions, allowing the parlor performers yet again to declare their comic interpretations.Footnote 80 An illusion outlined in several guides, the theatrical requires one boy to perch himself on the shoulders of another one, as they cover themselves with a long cloak and brandish a cane (Fig. 7). One manual suggests that, “if he wear[s] a stovepipe hat, with a feather in it, it will greatly heighten the effect” and that the effect “never fails to produce roars of laughter.”Footnote 81 The language rightfully emphasizes the comic ingenuity of the production. The sheer ridiculousness of the oversized sight, specifically in the context of the parlor, offers an altogether different humor than analogous public displays. Just as Tom Thumb corresponds to the German Dwarf and the Table Orator, Barnum's stable of real-life giants appears to have inspired the Kentucky Giant. Barnum staged the marriage of Mr. Robert Hales and Miss Eliza Simpson, otherwise known as the Quaker Giant and Giantess, on the stage of the American Museum in February 1849.Footnote 82 In the ensuing decades, he hosted or represented various other Brobdingnagian figures. Colonel Ruth Goshan (aka Ruth Goshen, Routh Goshen), who was billed (at least in Fig. 8) as the “Great Arabian Giant,” standing seven feet, eight inches tall and weighing 450 pounds, toured America in the 1860s under Barnum's banner and was sometimes paired alongside Thumb and other dwarf exhibits.Footnote 83 Barnum also managed Miss Anna Swan—whom broadsides boasted was an “immense specimen of humanity” over eight feet tall—on the same bill as the dwarf Gen. Grant Jr.—“the least of all little men, throwing Gen. Tom Thumb . . . and all the other Lilliputians in the shade.”Footnote 84 Since the middle classes often gathered at museums, restaging the spectacles at home allowed them to reinvent the popular culture they were being fed publicly. Presenting the Kentucky Giant alongside the German Dwarf in their parlors, middle-class amateurs would be playing with physical proportion just as Barnum did. Yet something was still novel in the remounting. Whereas Barnum relied on the unusual physicality of his performers for laughs, guidebooks’ comical displays inevitably cut deeper. Private actors could now engage in a double performance: imitating so-called freaks while also, through the cheap and silly production values, displaying their own professedly superior physicalities.

Figure 7. “How to Make a Giant,” Frank Bellew, The Art of Amusing (New York: Carleton, 1866), facing 112.

Figure 8. Playbill, Ruth Goshan: The Great Arabian Giant, Museum of Living Wonders, ca. 1862. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In this respect, the parlor performances were a means of declaring able-bodied whiteness as a distinctive middle-class trait—and as a defining quality of the human. Through their chameleonic enactments, middle-class Americans could not only establish class-exclusive entertainment practices but also could claim a biological authority over others. Their versatile physicality to take on any role—real or mythical, animal or human, white or Black—became a theatrical special effect of sorts. By dressing up as invented creatures or disproportionate grotesques, and then slipping back into their roles as genteel parlor dwellers, participants could perform their self-assumed normality. In other words, the middle classes proved that they were the apex of humanity by embodying, according to critic Mel Chen's hierarchy, the animals, the “de-subjectified disabled persons, [and the] persons of color subjected to racist psychologies” who by implication did not qualify.Footnote 85

Indeed, race was an invisible but omnipresent narrative to the parlor museum shows. Performing in an imperialist middle-class parlor often teeming with collectibles from African and Eastern countries, white participants could present their abilities to consume and imitate foreign cultures. While there may not have been a parlor theatre equivalent for, say, Barnum's “What Is It?,” the participants’ whiteness—and their attendant anti-Blackness—runs throughout home theatre history. Dawson notes two parlor plays adjacent to the museum genre, “The Fejee Islanders at Home” and “The Crocodile of the Nile,” emphasizing the “‘amusing’ physicality of indigenous peoples.”Footnote 86 Tableaux adaptations of Uncle Tom's Cabin require parlor actors to perform the titular character in blackface, and the guidebooks instruct performers how to employ burnt cork or black silks when imitating darker-skin characters.Footnote 87 Via this ostensibly benign game playing, participants were knowingly contributing to, in Christina Sharpe's words, Black people's “abjection from the realm of the human.”Footnote 88 Hence, whether performing as clumsily comical dwarfs and giants or as presumably uncivilized racial Others, white middle-class performers assembled a group of specimens to whom they compared themselves as favorably, definitively human. Barnum encouraged a similar dynamic at his Museum. But parlor actors’ newfound ability to embody foreign beings activated their self-definitions, including their prejudices, on an entirely new level.

Collectively, all of these parlor performances of the Other reinforced participants’ white, middle-class consumer values while also lending home performers a greater spectatorial power than they held in Barnum's public Museum. If exhibits like the overtly racialized “What Is It?” or the fascinatingly freakish Tom Thumb helped, as O'Neill puts it, “contribute to the creation of a white gaze that subjugates nonnormative, nonwhite persons,” then the private venue only extended such cultural work.Footnote 89 Staging their own museum exhibits promoted the middle classes as authoritative consumers—specifically, of alien objects and peoples. The fake animals are supposedly imported from exotic countries, the dwarf and giant from regions far removed from northeastern US cities, and the centaur from the mythical imagination. Moreover, the very basis of “The Museum” game involves pretending to be a proprietor who has bought such exhibits from distant lands. These performances were three-dimensional, live extensions of the exotic decorations that middle-class consumers had already purchased to ornament their parlor spaces. By playing alternative roles as both buyers and consumers of foreign goods, participants reasserted their white dominance. On another level, the parlor stage allowed home performers to prove themselves as effective consumers of public theatre itself. While Cook writes that “Barnum's trademark offer [was] to ‘let the public decide’ for itself” on the validity of his exhibits, many middle-class spectators may have chosen neither to confirm nor deny their acceptance.Footnote 90 Instead, the guidebooks prompted audiences to cut out Barnum as a middleman entirely and take the exhibits home with them. By restaging these features in private parlor spaces—now as knowing producers instead of less informed spectators—home performers could steal Barnum's theatrical thunder and declare their social and racial supremacy in one fell swoop.

Staging How the Other Half Lives: Home Temperance Tableaux

Restaging Barnum's freaks and wild specimens could provide a significant degree of self-affirmation for the middle classes, an appeal that stretched to other private performance genres. At-home temperance tableaux—also adapted from public Museum features—offered participants another distinctive method of sharpening class definitions. Common across parlor theatre guidebooks, these shows converted Barnum's temperance exhibits into an opportunity for middle-class readers to dress up as the oppositional working classes. Whether reimagining the Museum's graphic waxworks of drunkards or adapting the venue's full-length temperance dramas to the home stage, participants could pretend to be dissipated alcoholics. In fact, if the guidebooks were followed precisely, then performers may have gone to great lengths to embellish the grotesquerie of the commercial analogs. While amateur performers were often aligned with Barnum's lessons about temperance, home productions actually allowed them to bypass this single-minded morality tale. Instead, the parlor stage invited performers to reconceive Barnum's temperance shows as narratives about class behavior. Thus by staging graphic, often violent tableaux of lower-class drunkards, the middle classes could now define themselves as a decidedly separate, and superior, social group.

A teetotaler and antidrinking lecturer himself, Barnum utilized various types of temperance programming to recruit middle-class theatregoers. While the temperance movement saw widespread working-class participation in the 1840s, it had shifted to a primarily middle-class cause by the late 1850s and 1860s.Footnote 91 Men and women frequently defined themselves as middle-class through their personal temperance practices or via participation in temperance associations. Barnum unsurprisingly exploited these ties. In his lecture room, he produced temperance plays like W. H. Smith's The Drunkard (1844) or W. P. Pratt's Ten Nights in a Barroom (1858), the former of which broke attendance records.Footnote 92 Barnum made sure to spell out the morals too. These were straightforward temperance tales with an unmistakable lesson about alcohol's evils. He even encouraged spectators of The Drunkard to sign abstinence pledges at the box office following the show.Footnote 93 Beyond producing traditional dramas, Barnum also presented graphic waxwork displays of “The Temperate Family” and “The Intemperate Family” within his museums (based partly on illustrations in temperance literature, as in Fig. 9).Footnote 94 The latter exhibit revealed two drunkards, a father and son, wasting away in a wretched apartment. In a Barnum-sponsored literary pamphlet entitled Sights and Wonders in New York (1849), the character “Uncle Find-out” stops at the very same display to explain to his nephews a lesson about intemperance. He warns them to “touch not, taste not, handle not, the contents of the intoxicating bottle, lest your condition should be as unfortunate as the one you are now gazing upon,” after which the boys “shuddered, and passed to the other side.”Footnote 95 Hence, the middle classes were instructed to read the waxwork strictly as a temperance morality tale. But the displays held additional potential for even more narratives to be extracted from them. By importing versions of these narratives into their homes, the middle classes could also stage something more relevant to their own social mobility.

Figure 9. T. H. Matteson, “The Temperance Home” (top) and “The Drunkard's Home” (bottom), The National Temperance Offering, and Sons and Daughters of Temperance Gift, ed. S. F. Cary (New York: R. Vandien, 1850), facing 180 and 104, respectively. The American Antiquarian Society. Though an illustration of Barnum's temperance waxworks seemingly has not survived, the dichotomous iconography on which the exhibit was based remained a regular feature of the era's temperance literature, such as these selections from a temperance gift book. Note the secured, closed-door privacy enabled in “The Temperance Home” versus the impossibility of such privilege via the unhinged door (and invading stray dog) in “The Drunkard's Home.”

Namely, private temperance tableaux encouraged the middle classes to dress up as debased working-class figures. In doing so, performers could clearly reinforce their distinctions from this lower social tier that they were imitating, just as they did while costuming themselves as the physically abnormal dwarfs and giants. A subgenre of parlor theatricals, tableaux vivants required performers to hold still poses for thirty seconds at a time, often in a reproduction of a famous artwork or literary scene.Footnote 96 Oftentimes, the curtain would rise on a “slice of life” scene that may not be as recognizable. In one such tableau entitled “The Drunkard's Home,” outlined by author Tony Denier in his guidebook Parlor Tableaux; or, Animated Pictures (1868), actors costume themselves according to their narrow ideas of the intemperate lower classes. The drunkard sits in a chair, half-asleep, with matted hair, a “bloated and red” face, and “arms hanging down loosely by his side.”Footnote 97 His older daughter cries at the sewing machine, and two “ragged” children eat the last remnants of bread on the floor. The drunkard's wife lies on the bed, “sickly from want of proper food and nourishment. . . . [H]er eyes are sunken, and her cheeks hollow” (12). Instead of defanging the scene of its horror, Denier highlights the physical grotesqueries of the drunkard's world. He features the entire family to show both a complete portrait of lower-class existence and the far-reaching effects of nongenteel values. By inhabiting these roles, middle-class performers could enact stereotypes of working-class life that contrasted with their own supposedly refined habitations. The tableau's subjects appear as exotic creatures not emanating from some strange global corner but rather residing just downtown. As Denier's tableau description reads, “The scene represents the garret home of one of the many starving families that may be found in all large cities where vice and intemperance reign almost supreme” (11). Denier does not stray from Barnum's waxwork models but instead focuses in on the most terrifying aspects to espouse similar social morals. The tableau uses the ghastly visions of the drunkard in order to paint pictures of adjacent lower-class life. Denier reminds his respectable readers of the dangers in drifting from their principles (and their neighborhoods) because social demotion is always possible. At the same time, he assures the middle classes that their self-restraint stabilizes their position as the voyeuristic viewers of such scenes instead of the degraded objects of them.

As similar as the private and public versions of temperance-related fare sometimes were, the parlor tableaux affirmed the safety of middle-class spaces in a way that Barnum's exhibits could not. In Denier's “Drunkard's Home,” “the furniture is meager and almost valueless, or would have been sold long ago by the husband to satisfy his craving for drink” (11). In their similar tableau vivant also titled “The Drunkard's Home,” Arnold and Cahill depict a parallel scene: in “A dilapidated room, with an empty grate, and an empty saucepan lying on its side,” two children sit on a straw bed, and the drunkard sleeps in the corner: “Everything is to denote . . . misery and want.”Footnote 98 Viewing temperance plays and waxworks at Barnum's, middle-class visitors could become temporary witnesses of presumed lower-class sights but return to their secure homes afterward. Museumgoing thus became a relatively safe way for the middle classes to engage in downtown slumming. Still, an even safer method was staging these same scenes in the comfort of one's own home. The spare decor in both Denier's as well as Arnold and Cahill's tableaux contrast with the lushly decorated parlors in which the tableaux were typically performed. By dressing up their polished parlors as downtown tenement homes, the middle classes would force themselves—even if only momentarily—to imagine their home spaces as devoid of material possessions. The temperance-themed tableaux, then, enabled performers to bring visions of lower-class life into their homes in order to appreciate more viscerally their own private residences. As most single tableaux lasted only thirty seconds before being replaced with a new stage picture, the format allowed participants quickly to replace these temporary scenes of squalid poverty with more comforting ones of the restored middle-class parlor.

Perhaps no private theatrical demonstrates this effect more clearly than Denier's tableaux vivant adaptation of George Cruikshank's eight-plate series of temperance illustrations, The Bottle (Fig. 10). A violent morality tale about a drinker's gradual descent, The Bottle was stitched together into a slim volume and swiftly released to the British market in 1847. It was nothing short of a phenomenon. Within two days of The Bottle's release, it had sold a hundred thousand copies (priced at a shilling each) in England, and almost instantly made its way overseas to the United States.Footnote 99 One Evening Post ad for the book cites London reviews, such as Union Magazine's assessment of it as a “Hogarthian sermon of the most thrilling kind” and Jerrold's Newspaper's genre-inspired praise: “There is excellent dramatic conduct in this tragedy.”Footnote 100 Inevitably, commercial drama adaptations followed, with at least four separate versions produced in London and three different productions in New York, including most notably one at Barnum's Museum in January 1849.Footnote 101 Although the drama had more lasting runs in England, Cruikshank's volume was released by several different American publishers, and it was eventually spun off into home stereograph cards.Footnote 102 Unlike other temperance plays at Barnum's that foregrounded middle-class characters, The Bottle's drunkard—explicitly “a Mechanic” in the stage version—begins as resolutely working-class.Footnote 103

Figure 10. George Cruikshank, The Bottle. In Eight Plates (London: D. Bogue, 1847).

Cruikshank displays his drunkard's swift descent through the increasingly sullied appearances of the characters and the domestic space. Plates I–III show the family in their home, as the father's drinking gradually strips them of their possessions; plate IV reveals the family begging on the streets following their eviction; plates V–VII relocate the family to a desolate garret, where the infant dies and the husband violently kills his wife; and plate VIII exhibits the remaining children homeless and visiting their father, now “a hopeless maniac,” in the mental asylum.Footnote 104 Changes within the physical space are especially paramount to the tragedy. Within each successive picture, readers can note the staggered symbols of devolution. Take, for example, just some of the differences between plates I and II: the smiling mechanic from the first scene turns into a bloated and crumpled specimen in the second; the previously open and full cupboard is now nearly closed and hidden from view; a vase of vibrant flowers begin to wilt; a roaring fireplace has now expired. By plate III, most of the physical objects are gone, as Cruikshank's caption informs readers, “An execution sweeps off the greater part of their furniture. They comfort themselves with the bottle.”Footnote 105 It does not get better from there.

Denier soon adapted The Bottle into a series of home tableaux; as opposed to the full-length productions at Barnum's and other public playhouses, the material was a natural fit for middle-class private theatre since it dramatized the degeneration of the valued parlor itself. Cruikshank's eight plates are adapted into the same number of tableaux. Denier spells out each prop change in detail, and participants could simply dress down their parlors with each succeeding tableau. If the first tableau shows the “happy home of the industrious mechanic,” with cabinets “full of useful crockery and provisions,” then the second reveals a “dirty and uncomfortable” room with a “cupboard nearly empty.” The previously unremarkable “table with the plates, etc., as if after the meal” foregrounded in tableau I now is “placed near the back,” covered by a “table-cloth with holes in it” for tableau II.Footnote 106 While some participants may have opted to re-create the room upon a makeshift stage, the middle-class parlor itself provided all the necessary items for the scene changes. For the first tableau, performers might use their own furniture and decorations exactly as they appeared in the daytime. Yet as the series proceeds, only the parlor wall would remain as objects and ornaments were gradually knocked over or taken away. The accumulative decay of the physical space itself follows precisely the characters’ deeper moral ruin. For middle-class audiences of these amateur tableaux, the progressively spartan interior would provide a sustained, frightening picture of a lower-class existence.

For performers and spectators, this home theatre sequence carried a special power not possible in public venues like Barnum's Museum. As critic Alan Ackerman states, a crucial feature of private theatricals was the “defamiliarization of the domestic ethos.”Footnote 107 Here, Denier's “The Bottle” tableaux explicitly ask middle-class participants to imagine themselves stripped of the very room that defined them as a distinctive social tier. The architectural symmetry between the different locations is built into the script. With the exception of tableau IV (which takes place on “a street outside of a churchyard” [45]), all the backdrops are redecorated versions of a similarly oriented room, an ideal setup for home staging. The stage-right entryway in tableau I's domestic kitchen, for instance, later becomes an entrance to the garret (tableaux V–VII), and then finally a cell door within tableau VIII's asylum. Similarly, the first tableau's glowing fireplace transforms to the last tableau's “fireplace and . . . grate, with an iron cage around it to keep the lunatics from the fire” (49). This positional mirroring is particularly evident, too, when comparing Cruikshank's first and last plates. As the sequence's similar architecture conveys, the transition from mild prosperity to complete ruin can come swiftly.

Particularly in the last four tableaux, Denier provides detailed instructions about how participants can portray an incremental degeneration of interior space. By the time the family moves to the “dilapidated old garret” in tableau V, viewers would be encountering wretched visions of poverty (46). A rolled-up mattress sits against one wall, a fireplace with a few dying embers flickers, the attic window is “broken and stuffed with rags,” and a small coffin (holding the family's dead infant) occupies the background (46). Within the same garret in tableau VI, “the fire has died out for want of fuel, and in front of the fireplace is a clothes-line with a ragged pair of stockings hanging up to dry,” while “the table is overturned and lying on its side” (47). In front of these props, the drunkard father raises his fist in the air against the mother, as his two remaining children cling desperately to his torso and leg. Whereas the door remains closed even through tableau V, it remains open in the last three tableaux as the drunkard's descent is laid bare. With witnesses breaching the domestic border to observe the drunkard's graphic crimes in tableaux VI and VII—also seen in Cruikshank's plates of the same number—the privacy so sacred to the middle-class parlor is nonexistent here. The visual corruption of the home and the inevitable violence that accompanies it underscore the obvious morals about intemperance.

But the very nature of performing the sequence in the parlor opens up an equally significant, though perhaps not always conscious, narrative about class anxiety. By staging these scenes, participants could warn each other and their audiences about losing all their trophies of middle-class life. The eight-part performance required participants to display their lavish physical tokens and then gradually, in scene after scene, remove them from view. If (minus some objects) a parlor temporarily doubled as a working-class garret or a madhouse, then the participants would be asserting the fearful possibility of downward mobility. Through removing props and altering scenery, the series imparted to viewers how quickly one might fall from leisured respectability to laboring want to utter destitution. Despite all these fleeting terrors, however, it ultimately was a game of make-believe. Participants might get just enough of a petrifying peek of a different life to appreciate their own. When the evening ended, performers could restore their parlor to its former luxuriance and fully resume their comfortable lives as genteel citizens. This final, immediate release from an imagined lower-class existence rendered The Bottle series as an especially convenient, and potentially effective, vehicle for middle-class performance.

Returning from Barnum's

In December 1857, family magazine The Advocate and Family Guardian published an article entitled “Going to Barnum's,” which revealed a fictional but presumably representative trip to the public theatre. A young girl, Carrie, asks her uncle, Mr. Lane, to bring her to Barnum's New York Museum. Though the uncle states that the venue “is classed among innocent amusements,” he wonders aloud whether it has “become greatly vitiated in late years.”Footnote 108 Still, Carrie really wants to see the mummies, the boa constrictor, and Tom Thumb's carriage, among other attractions, and her uncle abides. They attend but are revolted by the “denuded appearance” of an actress and swiftly return home, where Carrie's Aunt Mary tells her a revealing story about Barnum's Museum (247). Aunt Mary recalls a friend who was neighbors with a misguided young girl named Ellen. As a teenager, Ellen began loitering backstage at Barnum's lecture room. Before long, she acquired designs to become a professional actress, and Barnum's performers proved willing mentors. Ellen then ran away from home in attempts to “join some company of traveling actors, and once, her father found her on the boards of a common theatre” (248). Eventually, Ellen became a disreputable young woman (and, it is implied, a boarding-house prostitute) while plotting to “prosecute her favorite plan, to fit herself for the stage” (248). Uncertain that her niece has absorbed the story's moral, however, Aunt Mary recites it plainly: “Barnum's . . . was the gateway to prison and life-long disgrace, and it may be, to a heavier punishment, for ‘Sin kills beyond the tomb’” (248).

The article proves telling about the public and private sites of leisure in mid-nineteenth-century America. The uncle's hesitancy to embrace Barnum's reflects both the middle classes’ suspicions of Barnum's curiosities and their abilities to judge for themselves the value of theatrical shows. After watching the play featuring the scantily clad actress, the uncle can only conclude that mainstream “theatrical exhibitions, are really less objectionable, than these bungling imitations in the Museum” (247). Barnum's Museum displays and theatrical features, at their core, strike the uncle as disingenuous. Even the child Carrie can detect something awry onstage and maintains no interest in exploring the Museum afterward. In the safety of the home, Carrie and her uncle become invested in Aunt Mary's tale specifically because it confirms their distaste for the public theatre. Among a “happy group . . . gathered in the parlor that evening,” Carrie and her uncle typify the middle classes’ midcentury retreat into private space (247). Mr. Lane reads a newspaper under a shaded lamp, Aunt Mary engages in needlework, and Carrie and her cousin George peruse a portfolio of engravings (247). For some middle-class Americans, these class-exclusive activities in the parlor might soon complement, or even substitute for, public entertainment. Just as in the Advocate's pleasant domestic scene, the nation's middle classes were beginning to discover their own potential for creating satisfying amusements within the private home.

Carrie's flirtation with the public world came on the eve of parlor theatres’ heyday, in which guide authors encouraged do-it-yourself adaptations of commercial entertainments. The first major home theatrical guide, Arnold and Cahill's The Sociable, would be released the next year, in 1858, and dozens followed soon thereafter. The private theatre, these books suggested, remained the safest venue. If aspiring to be an actress, little Carrie could perform plays at home among her own social group and not risk the class mixing and social demotions associated with the public stage. If she wanted to observe foreign curiosities and stage thrills, then she could attend a neighbor's or a cousin's parlor theatricals, or she might read the escapist story papers increasingly popular among the respectable ranks.Footnote 109 Parlor theatre guidebook authors essentially gave middle-class consumers a blueprint for their own class definition. By adapting and revising Museum exhibits and theatrical shows, participants could determine who they were both as amateur stage performers and as social actors. Barnum may have provided the middle classes a new outlet to congregate, and his exhibits undoubtedly inspired this evolving collective. But in the end, Barnum's Museum was a stop, not a destination. By importing, and essentially remaking, the showman's attractions, middle-class spectators ultimately would craft their own gateway to respectability.

Michael D'Alessandro is Assistant Professor of English and Theater Studies at Duke University. He holds an M.F.A. in Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism from Yale University and a Ph.D. in American Studies from Boston University. His articles have appeared in J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists, American Art, The New England Quarterly, and Mississippi Quarterly. His first book, Staged Readings: Contesting Class in Popular American Theater and Literature, 1835–75, is forthcoming from the University of Michigan Press.